Duncan Green's Blog, page 138

July 19, 2016

Do aid organisations need marriage guidance? Five lessons for better partnerships

Audrey Lejeune

Audrey Lejeune (right), Programme Learning Adviser and Yo Winder (left), Global Partnerships and Accountability Adviser, both of Oxfam, introduce Partnership for Impact – a series of reflections by its staff

(right), Programme Learning Adviser and Yo Winder (left), Global Partnerships and Accountability Adviser, both of Oxfam, introduce Partnership for Impact – a series of reflections by its staff

Oxfam works in partnership with almost 700, often very different, organisations: academic institutions, UN agencies, national and/or sub-national NGOs and Civil Society Organisations – some of whom will be lobbyists, some of whom will truck water on our behalf, local government entities, private sector enterprises, this list is not exhaustive.

Being the best partner we can be is the task Oxfam is setting itself for the next few years. Which will mean some big changes to the way we conceive of ourselves as a partner, how we understand the part we need to play and how we actually behave.

Development work mirrors life, we have different relationships in our life and they bring different joys and challenges, but in most situations the best outcomes always happen when we are thoughtful, mindful, flexible and kind. So we’ve asked ourselves, if Oxfam is aiming to be the best partner it can possibly be (a nice person to be around) what do we need to change? Here’s what we’re going to work on:

Acknowledge and promote the work of partners: Partners do most of the work and yet we only really talk about ‘Oxfam’s programme’ and the work that ‘Oxfam does’ – both to ourselves and to others. Intellectually we understand that ‘[we] work with others to relieve poverty, distress and suffering’ but, it appears, we also rather like to hog the limelight.

about ‘Oxfam’s programme’ and the work that ‘Oxfam does’ – both to ourselves and to others. Intellectually we understand that ‘[we] work with others to relieve poverty, distress and suffering’ but, it appears, we also rather like to hog the limelight.

Our colleague Sekou Doumbia from Oxfam’s Mali programme wrote a thoughtful piece on this during a recent retreat for Oxfam staff who work with partners on a daily basis to reflect on and capture the challenges and experiences.

Oxfam is experimenting with encouraging partners to join our Policy and Practice community via this webpage and are aiming for this to become:

a place where we can actively showcase the work the partners do

a way of achieving greater transparency by providing all our policies, tools and guidance that govern how we work in partnership

somewhere partners can come for ‘added value’ from Oxfam – with links to others’ work on partnership, calls for funding proposals, direct links to relevant research etc.

Check our attitude: greater humility, taking up less space, not always being the ‘expert’, really listening to what others think the answers might be. What might this look like in practice? We’re really excited by this (non-Oxfam) initiative – Somali women demanding change and demanding more power.

Illustration copyright Christine Harrison: http://www.christineharrisondesign.com/

Aiming for equity rather than equality: one size does not fit all. We work in partnership with a plethora of different types of organisations, and in a myriad of different ways. Or we should. What we contribute to our partnerships should be dictated by the context and what needs to be done. Partners do not always want the same deal from us (equality) they deserve the best we can give them to have a fair chance of getting the job done (equity). We need to seek ways to make our approach more adaptable and appropriate; for example our colleague Dunstan Macharia in Kenya argues that more flexibility in how we apply business processes could bring positive change to the way we increasingly work in consortia.

Understanding our role in networks: working in networks can improve a programme’s effectiveness. That is when it’s done well. We already have significant experience in networking and we continue to learn. Thomas Dunmore Rodriquez, a National Influencing Advisor, says his experience is that it is important to “be prepared at some points to step back and let others define the agenda and lead.” Oxfam’s current vision is that we should become expert facilitators and convenors rather than our default position of funders and experts.

It is hugely exciting to create the opportunity to work with unusual suspects, sometimes those we have been a little wary of in the past (*cough* private sector *cough*). For many of our staff, this is a new and exciting way of working. “When I attended my first Tajikistan Water Supply network meeting, I found a room full of people and dynamism. I was also curious to know who came up with the idea to gather together all these people and make them share ideas, knowledge and skills” Writes Bekhruz Yogdorov, Networking/Partnership Project Officer in Tajikistan.

Building the capacity of our staff: Oxfam’s staff at country level are being called on to find, select, build, negotiate, nurture and learn from a myriad of different types of partnership. Doing this well demands an exceptional range of skills from convening, brokering, to conflict resolution and using different communication approaches. “Power imbalances, knowledge gaps, and absence of trust and respect can damage relationships with partners.” argues Ashish Kumar Bakshi Programme Manager in Bangladesh.

negotiate, nurture and learn from a myriad of different types of partnership. Doing this well demands an exceptional range of skills from convening, brokering, to conflict resolution and using different communication approaches. “Power imbalances, knowledge gaps, and absence of trust and respect can damage relationships with partners.” argues Ashish Kumar Bakshi Programme Manager in Bangladesh.

Since we don’t have all of the resources internally to build and nurture the types of partnering skills we need for the future, we are working in partnership with the Partnership Brokers Association. ,

In conclusion

If “partnerships are relationships. Just like marriage and other relationships they need revival, excitement, continuous engagement, and more for them to survive and remain beneficial to the parties involved” as our colleague Mutinta Nketani from the Zambia team argues, then is Oxfam in quite some need of marriage counselling?

Anyone wish to offer us some marriage guidance counselling? Is this the right analogy? Have we selected the right things to focus on? What’s your experience, what can we learn from you?

July 18, 2016

What are the implications of systems thinking for the way we design research?

If you stick around in your job long enough, you end up getting consulted a lot. Every week I seem to spend a couple of hours on skype banging on to assorted academics, NGOs consultants etc about NGOs, aid, development, life, the universe etc. The only upside (apart from a bit of human contact and an escape from reading/writing boring development documents) is getting the odd idea for a blog out of the conversations.

of hours on skype banging on to assorted academics, NGOs consultants etc about NGOs, aid, development, life, the universe etc. The only upside (apart from a bit of human contact and an escape from reading/writing boring development documents) is getting the odd idea for a blog out of the conversations.

This week it was Open University’s Jude Fransman, who coordinates a seminar series on the politics of evidence in academic-NGO research partnerships. The topic was a bit of a chestnut – how NGOs understand, carry out and use research. I’ve written about it quite a bit in the past, but the new angle was taking the conclusions of How Change Happens (did I mention I’ve got a book coming out?….) on how systems thinking means activists should be rethinking their roles and applying them to the way NGOs (and others) do research. See what you think.

Getting beyond supply or demand to convening/brokering

Supply-driven is the norm in development research – ‘experts’ churning out policy papers, briefings, books, blogs etc etc. Being truly demand driven is hard even to imagine – an NGO or university department submitting themselves to a public poll on what should be researched? But increasingly in areas such as governance or value chains, we try and move beyond both supply and demand to a convening/brokering role, bringing together different ‘unusual suspects’ – what would that look like in research? Action research, with an agenda that emerges from an interaction between communities and researchers? V little of that going on at the moment. Natural science seems a bit ahead on this one – Irene Guijt points out that when the Dutch National Research Agenda ran a nationwide citizen survey of research questions they wanted science to look at, 12,000 questions were submitted and clustered into 140 questions, under 7 or 8 themes. To the organizers’ surprise, many citizens asked quite deep questions.

Diversity and Unusual suspects

A linked point. The research world is a very determined set of monoculture sub-cults/sub-systems, with discipline-centric accepted ways of doing everything, siloed sets of standards that inhibit interdisciplinarity etc. There are some good reasons for that (e.g. quality assurance), but there are some more disreputable ones to, in terms of paradigm maintenance in various disciplines. What would research agendas and processes look like that were decided elsewhere – by indigenous groups, women’s groups or faith organizations?

But what if something happens?……

Critical Junctures

Social and political change is seldom smooth, and often crystallises around critical junctures – shocks like Brexit or the Turkish coup throw existing power relations and norms into the air, and when they come back down, new opportunities are briefly possible (not all of them good). Currently thinktanks are pretty good at this kind of rapid response, at least in terms of commentary (eg CGD and ODI on Brexit), whereas academic institutions are much more sluggish. Could/should NGOs do more, especially in going beyond commentary to using research to actively influence policy or attitudes in the wake of shocks?

Norms not just policies

The central role in development of long-term shifts in underlying social norms has often been underestimated in an aid business focused on project cycles, policies and decision-making, rather than big, slow attitudinal shifts. Gender is one exception – an area where activists working on environment or migration could learn a lot about shifting norms, yet is very under-researched (with some notable exceptions).

Precedents: History and Positive Deviance

OK, I have ranted about this a lot, but it applies in spades to thinking about research. We don’t spend nearly enough time thinking about what already works, either historically or today. Research could really help fill in historical gaps, whether on campaigns or redistribution. We should also pay much more attention to seeing where good stuff is already happening in the system (i.e. in real life, not just in our projects, for example identifying and studying villages with lower than average rates of maternal mortality and then going and trying to find out why).

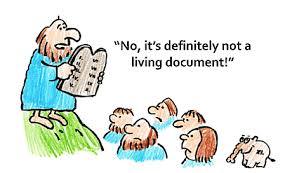

Feedback and course correction – living documents

In systems, your initial intervention is likely to have to be tweaked or totally overhauled in light of feedback from  experience or events. Yet we still portray our research papers as tablets of stone – the last word on tax reform, women’s rights etc etc. Digital allows us to make them all ‘living documents’, subject to periodic revision, maybe even encourage wiki-policy papers (with moderation to keep things sensible). After all, I regularly get it wrong on this blog, and readers’ comments put me straight – what’s stopping us doing it across the board?

experience or events. Yet we still portray our research papers as tablets of stone – the last word on tax reform, women’s rights etc etc. Digital allows us to make them all ‘living documents’, subject to periodic revision, maybe even encourage wiki-policy papers (with moderation to keep things sensible). After all, I regularly get it wrong on this blog, and readers’ comments put me straight – what’s stopping us doing it across the board?

Then of course there’s Brexit – what is the role of research in an era of post-truth politics and ‘we’ve heard enough from experts’? Think that might need another post, though.

Any other thoughts?

And as it’s been a while since I last vlogged, and it’s summer. Here’s me apparently sitting in a bush in my garden

July 17, 2016

Links I Liked

Girls’ adolescence as critical juncture, c/o World Economic Forum

Girls’ adolescence as critical juncture, c/o World Economic Forum

Great bluffer’s guide for techno-phobes and -philes alike. The top 10 emerging technologies of 2016. ‘Organs on Chips’?

Prepare to be astonished. Men are more likely to cite their own research than women and the gender self-promotion gap is rising.

Africa is moving toward a massive and important free trade agreement – Africa’s Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA)

Do cash transfers to mothers always produce better results? Not in West Africa, apparently

“The decline in new HIV infections stalled five years ago and that, in some areas, the numbers are rising again” Good Guardian summary of depressing stats and trends

Dilbert on disruption in large organizations. No relevance to Oxfam , obvs

Dilbert on disruption in large organizations. No relevance to Oxfam , obvs

Why did God make hippos? All is explained: [h/t Tim Harford]

‘The International Development Jargon Detector counts jargon words in reports, presentations and other documents. Upload a file to start catalyzing sustainable change.’ Go on, no-one will know…….[h/t David Sasaki]

Why has anti-globalization sentiment been captured by the Right? The abdication of the left, argues Dani Rodrik. But he reckons ‘ the intellectual vacuum on the left is being filled’ (optimism of the will?)

Three new additions to Oxfam’s handy research guidelines series: on survey sampling, lit reviews and how to give feedback (last one by me)

And it may be 35 years old, but for some reason, the Gil Scott Heron classic ‘B Movie’ is stuck in my head. Maybe something to do with ‘this country wants nostalgia. They want to go back as far as they can – even if it’s only as far as last week. Not to face now or tomorrow, but to face backwards. And yesterday was the day of our cinema heroes riding to the rescue at the last possible moment. The day of the man in the white hat or the man on the white horse – or the man who always came to save America at the last moment – someone always came to save America at the last moment’. Full lyrics here

July 14, 2016

What’s the evidence on fundraising with language of pity v language of dignity? Testing the Narrative Project

Guest post by Alison Carlman of GlobalGiving

Guest post by Alison Carlman of GlobalGiving

A report was published last week shedding new light on the Narrative Project. In case you’re not familiar, The Narrative Project was a wide-scale research project driven by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, InterAction, and other major NGOs in the lead-up to 2015 (and the new Sustainable Development Goals), aiming to improve US, UK, French, and German public perceptions of aid and development cooperation. The Narrative Project researchers claim that messages and stories carrying certain narrative themes—independence, shared values, partnership, and progress—motivated certain segments of the population to change their attitude about global aid. It also found an increase in the target group’s self-reported likelihood to take action to support global development causes.

The Narrative Project Themes: Independence, Shared Values, Partnership, Progress

I was one of ten nonprofit communicators awarded a grant to test the Narrative Project last year. I wanted to know whether using Narrative Project recommendations could go beyond attitude change; could they influence behavior and motivate people to give? After all, most of us who work in smaller nonprofits don’t have the luxury of aiming only for long-term perception change with our day-to-day work.

You’ve probably seen plenty of evidence that pity-based fundraising appeals motivate people to open their wallets, but as a reader of this blog, you and your team have also probably long-abandoned those flies-in-the-eyes fundraising approaches in favor of more dignifying, nuanced storytelling. The Narrative Project was exciting to me because it was the first empirical study I’d seen that offered a dignifying approach that had the promise to be more powerful than pity-based approaches AND other empathy-based approaches that we’ve been employing. Could the Narrative Project findings and recommendations really be that powerful?

Sample Revisions in the Narrative Project User Guide

Diving Into Data

My colleagues and I analyzed GlobalGiving’s database of 50,000 “project reports” (stories) written by our nonprofit partners from 165+ countries over the past eight years to see how Narrative-Project-aligned reports performed in terms of fundraising compared to others. We also conducted six A/B tests with more than 160,000 newsletter subscribers to see how our normal appeals fared compared to Narrative Project appeals that highlighted independence, shared values, partnership, and progress, according to the user guide. Here are examples of an A (control) and B (test) version of an appeal we sent.

Results

What did we find? The Narrative Project didn’t work. Not for fundraising, at least. During our data dive, I was surprised to find the Narrative Project-aligned reports triggered a statistically significant lower number of average donations in aggregate than the non-aligned reports (some which may have been pity-based, but others were not). After the six A/B tests, I was also surprised to find that the Narrative Project wording performed significantly worse than our normal empathy-based appeals. Ouch.

But Wait! There’s More!

While we were examining the fundraising effects of different types of narratives, we did uncover something exciting: the reports and stories that included first-person pronouns were actually more successful at driving donations. What did that mean? Allowing people to tell their own stories in their own words can be an effective fundraising strategy. What’s more, first-person narratives might not only raise more money, but I suspect they also help empower storytellers and strengthen the nonprofit ecosystem as well.

The Triple Bottom Line

In the corporate world we talk of the triple bottom line: responsible companies make decisions that help them benefit People, Planet, and Profit. I believe that a triple-bottom-line also exists for nonprofit communicators and fundraisers: we have the responsibility to share narratives that edify the People we ultimately intend to help, and also support the Planet (the nonprofit/global development ecosystem) and also drive Profit (or funding for the cause).

We can’t only ask whether a communication strategy “works” for fundraising; we should also ask ourselves: “How are we empowering this girl by helping tell her story, rather than objectifying and further marginalizing her on a public scale? Are our stories damaging the public’s understanding of the problem, and their perceived ability to make a difference? How does our content affect the way nonprofits and so-called ‘beneficiaries’ view themselves in the system?”

As the Narrative Project gains influence in our sector, I hope we’ll see it as fuel for an ongoing conversation about better storytelling in global development, but not a silver bullet for all nonprofit communications. This year at GlobalGiving we’ll be diving deeper into our counter-hypothesis, that first-person narratives could be more powerful and effective at benefiting the people we intend to help, the social sector ecosystem, and the funding channels that support our work. Read more about our Narrative Project research on our Tools + Training Blog.

What’s the evidence on fundraising with images of pity v images of dignity? Testing the Narrative Project

Guest post by Alison Carlman of GlobalGiving

Guest post by Alison Carlman of GlobalGiving

A report was published last week shedding new light on the Narrative Project. In case you’re not familiar, The Narrative Project was a wide-scale research project driven by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, InterAction, and other major NGOs in the lead-up to 2015 (and the new Sustainable Development Goals), aiming to improve US, UK, French, and German public perceptions of aid and development cooperation. The Narrative Project researchers claim that messages and stories carrying certain narrative themes—independence, shared values, partnership, and progress—motivated certain segments of the population to change their attitude about global aid. It also found an increase in the target group’s self-reported likelihood to take action to support global development causes.

The Narrative Project Themes: Independence, Shared Values, Partnership, Progress

I was one of ten nonprofit communicators awarded a grant to test the Narrative Project last year. I wanted to know whether using Narrative Project recommendations could go beyond attitude change; could they influence behavior and motivate people to give? After all, most of us who work in smaller nonprofits don’t have the luxury of aiming only for long-term perception change with our day-to-day work.

You’ve probably seen plenty of evidence that pity-based fundraising appeals motivate people to open their wallets, but as a reader of this blog, you and your team have also probably long-abandoned those flies-in-the-eyes fundraising approaches in favor of more dignifying, nuanced storytelling. The Narrative Project was exciting to me because it was the first empirical study I’d seen that offered a dignifying approach that had the promise to be more powerful than pity-based approaches AND other empathy-based approaches that we’ve been employing. Could the Narrative Project findings and recommendations really be that powerful?

Sample Revisions in the Narrative Project User Guide

Diving Into Data

My colleagues and I analyzed GlobalGiving’s database of 50,000 “project reports” (stories) written by our nonprofit partners from 165+ countries over the past eight years to see how Narrative-Project-aligned reports performed in terms of fundraising compared to others. We also conducted six A/B tests with more than 160,000 newsletter subscribers to see how our normal appeals fared compared to Narrative Project appeals that highlighted independence, shared values, partnership, and progress, according to the user guide. Here are examples of an A (control) and B (test) version of an appeal we sent.

Results

What did we find? The Narrative Project didn’t work. Not for fundraising, at least. During our data dive, I was surprised to find the Narrative Project-aligned reports triggered a statistically significant lower number of average donations in aggregate than the non-aligned reports (some which may have been pity-based, but others were not). After the six A/B tests, I was also surprised to find that the Narrative Project wording performed significantly worse than our normal empathy-based appeals. Ouch.

But Wait! There’s More!

While we were examining the fundraising effects of different types of narratives, we did uncover something exciting: the reports and stories that included first-person pronouns were actually more successful at driving donations. What did that mean? Allowing people to tell their own stories in their own words can be an effective fundraising strategy. What’s more, first-person narratives might not only raise more money, but I suspect they also help empower storytellers and strengthen the nonprofit ecosystem as well.

The Triple Bottom Line

In the corporate world we talk of the triple bottom line: responsible companies make decisions that help them benefit People, Planet, and Profit. I believe that a triple-bottom-line also exists for nonprofit communicators and fundraisers: we have the responsibility to share narratives that edify the People we ultimately intend to help, and also support the Planet (the nonprofit/global development ecosystem) and also drive Profit (or funding for the cause).

We can’t only ask whether a communication strategy “works” for fundraising; we should also ask ourselves: “How are we empowering this girl by helping tell her story, rather than objectifying and further marginalizing her on a public scale? Are our stories damaging the public’s understanding of the problem, and their perceived ability to make a difference? How does our content affect the way nonprofits and so-called ‘beneficiaries’ view themselves in the system?”

As the Narrative Project gains influence in our sector, I hope we’ll see it as fuel for an ongoing conversation about better storytelling in global development, but not a silver bullet for all nonprofit communications. This year at GlobalGiving we’ll be diving deeper into our counter-hypothesis, that first-person narratives could be more powerful and effective at benefiting the people we intend to help, the social sector ecosystem, and the funding channels that support our work. Read more about our Narrative Project research on our Tools + Training Blog.

July 13, 2016

Desertification is a dangerous Myth – A new book explains why

Oxfam researcher John Magrath reviews an explosive new book

I started off life as a newspaper journalist so I appreciate the power of a good story. And that’s what the concept of desertification provides. Since the great Sahelian droughts of the 1970s and 1980s, we’ve become familiar with the idea that humans cause environmental desiccation and destruction on a huge scale; local people, usually, herders and pastoralists with too many animals, strip vegetation, soils blow away, temperatures climb as the merciless sun shines down on the newly reflective landscape and often, hunger (and conflict) ensues. This is a powerful metaphor – a morality tale – for what humankind is doing to the Earth, and the answers to this simple narrative can seem equally simple: move people and their animals into settlements, fence off land, plant trees.

The desertification story has had enormous influence. There is a UN Convention to Combat Desertification and the word has recently been incorporated into Sustainable Development Goal number 15. And most importantly, measures intended to prevent and reverse desertification are being pursued, especially in Central Asia and in China. Desertification in this narrative is almost irreversible unless superhuman efforts are employed – ‘great green walls’ of trees spanning nations being a popular strategy.

So it is quite a shock to be presented with an abundance of evidence that ‘desertification’ doesn’t happen – leastways, not in anywhere near the sense in which it has been explained. Scientifically it is a meaningless and indefinable concept; the desertification of the Sahel that created the scare happened for quite other reasons (and wasn’t irreversible); and the standard policies to reverse desertification generally do more harm than good, to environment and to people.

$229 and all I get is two colours?

This is the thesis of a new book by 20 experts in the field. “The End of Desertification? Disputing Environmental Change in the Drylands” is a collection of essays edited by Roy Behnke and the veteran drylands expert Mike Mortimore. Published with the help of the UK-based International Institute for Environment and Development and Tufts University in the USA, and launched on 8th July, it pulls no punches (nor do the publishers – at $229 a pop, this blog is probably as much as you are going to read, although you can read a few pages of each chapter before you start reaching for your credit card, see http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783642160134).

It begins: “The opening chapters of this book examine something that never occurred but was widely believed to have existed – the late 20th Century desertification crisis in the Sahel”. The notion of widespread, catastrophic environmental degradation was, the authors say, a non-event. And the droughts that happened did not happen because unintelligent local people were over-exploiting their land, but because of global climate changes brought about by changes in the composition of atmospheric greenhouse gases and particulates (and the Sahel is now much wetter once again for the same reasons).

Scientifically, our understanding of dryland ecology has moved on from ideas that drylands are somehow pristine environments existing happily until humans came along, to an understanding that humans and environments co-exist; change is constant; and there is no one size fits all – “ecological change is as varied and locally specific as the heterogeneous social and physical environments in which it takes place”.

That is definitely not to say that severe land degradation doesn’t happen in places, because it does (for example, the

Turns out they’re not the problem after all

Borana plateau of southern Ethiopia – but the reasons are complicated). And it is not to substitute one myth for another – that somehow herders ‘in touch with Nature’ are always wise and innocent, a kind of ‘noble savage’ myth. But it profoundly changes the right question to ask. Saverio Kratli from the Commission on Nomadic Peoples says instead of starting from the premise that “grazing is wrong, what can we do to stop it?” you ask, “what aspect of grazing is going wrong and how can we correct it?”.

However, will “The End of Desertification?” create a new narrative? That will be very difficult (and not just because their book is very, very expensive). The notion of desertification has three characteristics of a compelling story. It is “dramatic enough to command attention; simple enough to be easily grasped; and general enough to satisfy diverse interest groups”. “The institutionalisation of desertification within the UN system has fostered the conviction that the concept must be relevant to something important” and as we know, publicists, administrators and politicians “thrive on crises and on unequivocal prescriptions for addressing crises”.

Sadly, the opponents of desertification still have no such simple narrative; basically, what they are saying is that reality is messy. And the answers are not environmental, they are political – essentially, stop seeing local communities as the source of the problems. However, even where governments have seemingly abandoned a simplistic notion of desertification for a more sophisticated understanding, as in Ethiopia, practices have hardly

Not just the graphics are rubbish

changed; as Ian Scoones notes, “they get the [donor] money by using the latest rhetoric but nothing has changed [because] it’s about making the drylands governable by a centralised state”. In China, nothing has changed despite private reservations by many environmentalists and journalists: “In destroying pastoral communities and their way of life, government is unknowingly destroying the means to achieve its environmental objectives”.

So what does work? Mark Stafford Smith sees hope for the non-desertification narrative in dryland dwellers finding common cause with the concept of resilience, and especially, building local institutions with devolved funding and governance arrangements and supportive networks. This may, he reflects, “be a view coloured by living in a pluralistic democracy, where these interventions are hard enough; they may be hopeless in totalitarian or oligocratic systems…”.

Maybe he is right but let’s end on a note of hope. In the Sahel, ‘benign neglect’ – the inability of central government to enforce its writ has been allied to some genuine governmental willingness to listen, learn and change policies. At the book launch veteran anthropologist Mary Tiffen reflected how things had improved in northern Nigeria since her first field work there in the 1960s. She had returned recently to see and ask, what and why? Village leaders never mentioned drought shocks, or climate change, but insisted that three big changes have enabled people to cope better, and they have all been political: in the 1980s local government got some federal revenue; in the 1990s her area of research became a state in its own right with its own tax-raising powers; and lately people elected a competent governor who spent the money wisely.

July 12, 2016

NGOs face a slow-onset funding disaster – what can be done to avoid it?

Brexit is prompting a lot of discussion within the UK’s aid community right now. But while the focus is  understandably on EC funding and exchange rates, there’s a less visible and potentially more dangerous funding threat to deal with, argues Michael O’Donnell of Bond (the network of UK development NGOs).

understandably on EC funding and exchange rates, there’s a less visible and potentially more dangerous funding threat to deal with, argues Michael O’Donnell of Bond (the network of UK development NGOs).

Right now, NGO staff focused on quality and effectiveness need to mobilise and polish their skills of persuasion, because it’s about to get a lot harder to keep organisations focused on those issues. Why? Because for NGOs receiving funding from donors in Europe – and particularly the UK – flexible or unrestricted funding is getting squeezed on multiple fronts, and flexible funding is the friend of quality work.

Unrestricted, flexible funds – often money from the general public or strategic grants – are the things that pay for NGOs’ M&E systems and advisors, not just the people working to deliver one specific project. They may pay for investment in local consultations and intervention design, in innovation or in setting up a feedback mechanism to ensure you adapt your services in light of users’ experience. They usually fund the time spent discovering what researchers have found out about your area of interest, or what worked previously. And everyone knows how precious those funds already are. For the not-for-profit sector, unrestricted funds serve many of the same functions as investment capital and recycled profits do for the private sector.

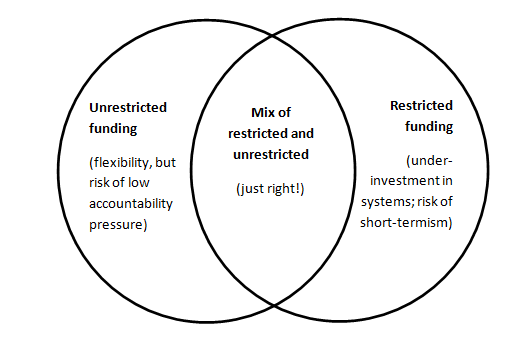

In Bond, we’ve found that the organisations with a healthy mix of unrestricted and restricted funding sources tend to perform best on various measures of effectiveness. Having a blend of both seems to mitigate the risks associated with too much of either. Put simply (and over-simplistically), the basic risks are of short-term restricted funding that is too ‘projectised’, and unrestricted funding that is too unaccountable. Good design and management, however, can tap into the huge potential of flexible funding to invest in effectiveness, and can capitalise on the healthy pressure of competitive bidding and external accountability associated more with restricted funding.

The “Goldilocks” funding blend for NGOs

In the UK, the squeeze on unrestricted funding is coming from a number of sides.

Public trust in NGOs is on the decline and increased fundraising regulation is in the pipeline: income from the general public has flat-lined over the last decade overall, with many NGOs anticipating (or already experiencing) falls.

Scepticism about aid also puts pressure on governments either to cut budgets (avoided so far in the UK) or to make sure that they can prove ‘results’ are being achieved. The latter encourages the temptation to demand short-term, measurable, easily-communicated results, attributable to single interventions. These are all features that are highlighted in critiques of the ‘results agenda’ from IDS to ICAI, and at odds with thinking on complexity, adaptation and what’s needed to address the Sustainable Development Goals.

DFID’s main source of strategic, flexible funding to NGOs (Programme Partnership Arrangements – PPAs) is coming to an end, and there have long been warnings from DFID that it won’t continue.

And there’s the latest short-term shock of the post-Brexit depreciation in the value of the pound, reducing what UK-based actors can purchase overseas, and thus possibly requiring NGOs to redirect some unrestricted funding to avoid cuts in ‘frontline’ spending.

In an informal, rapid survey of NGOs with DFID PPA funding earlier this month, in addition to substantial uncertainty about the future, Bond found that the coping mechanisms NGOs are tapping into to keep up overall activity levels (e.g. commercial contracts, more restricted funding, cost-cutting) risk having a detrimental effect on programme quality. NGOs reported increasingly struggling to fund things like M&E, learning, research, innovation and advocacy work: things that underpin effectiveness, but which don’t make for compelling narratives about quick achievements. It may not be a dramatic San Andreas to what Duncan has termed the UK’s developmental Silicon Valley, but it’s more of a slow-onset disaster. Even if you think it would be good for ‘those complacent old dinosaur international NGOs’ to be cut down to size somewhat, more restricted, inflexible, short-term funding is certainly not what is needed to strengthen southern civil society either.

The history of development is littered with sub-optimal programmes where learning did not happen and the same mistakes were repeated. We must not backtrack on (slow, painful) recent progress. So what’s the response? Here are a few suggestions:

We need to make a strong collective case for investing in things like monitoring, evaluation, learning, innovation and adaptation. For example, the World Bank’s IEG recently put out a good analysis of how high quality M&E increases programme performance. We must hold donors accountable for having fit-for-purpose funding policies and practices. It would be great to see DFID underline the importance of quality as they set out their plans in the Civil Society Partnership Review, for example.

Communications is as important as evidence: the declining trust in charities and scepticism about the aid effectiveness that create political pressures for more restricted funding requires smart comms people to help message a confident case both to funders and to the giving public.

NGOs need to be more confident in understanding and budgeting for all their costs, and recovering those

within restricted grants and contracts, so that all that good stuff that has indirect value for programme quality isn’t underfunded. The ‘starvation cycle’ of minimising and demonising ‘overheads’ needs to stop.

within restricted grants and contracts, so that all that good stuff that has indirect value for programme quality isn’t underfunded. The ‘starvation cycle’ of minimising and demonising ‘overheads’ needs to stop.If restricted funding is to be the way forward, at least let’s get cleverer about designing more flexibility into it. A focus on accountability for ‘results’ does not need to be incompatible with definitions of results that are long-term, meaningful to the populations they are intended to benefit and which can accommodate some uncertainty or risk. There are encouraging examples from DFID and its Better Delivery agenda around more flexible results frameworks in grants and commercial contracts, for example (e.g. SAVI).

We know how rapid-onset disasters get the attention in our sector: for this slow-onset funding disaster we need to read the early warning signs now and mobilise to mitigate the risk of declining quality of work.

July 7, 2016

Off to sit on a rainswept rock for a few days (aka a British holiday)

Actually, by the time you read this, I’ll already have been there for a while – such is the lag on posting blogs. Destination this time is Lundy, 5km x 1km, resident population of 28 people. Good for puffins, apparently . Will be taking some heavy duty novels, in case the rain persists, and binoculars in case we can leave the house. Back in a few days.

some heavy duty novels, in case the rain persists, and binoculars in case we can leave the house. Back in a few days.

Does this puffin remind you of Boris Johnson, or do I just really need a holiday?

July 6, 2016

Campaigning to Make India’s Roads Safer: A nice How Change Happens case study

A smart How Change Happens case study by David Bornstein in the New York Times’ ‘Fixes’ series (highly  recommended). Bornstein looks at the advocacy of the SaveLife Foundation, set up by Piyush Tewari, a businessman, after his cousin Shivam was knocked down by a jeep then left to bleed to death by the roadside. Excerpts + commentary from me in italics.

recommended). Bornstein looks at the advocacy of the SaveLife Foundation, set up by Piyush Tewari, a businessman, after his cousin Shivam was knocked down by a jeep then left to bleed to death by the roadside. Excerpts + commentary from me in italics.

“India has surpassed China as the global leader in road accidents. Last year it had 146,000 deaths. The Indian government has estimated that half of the deaths could be prevented if victims received timely medical care. Most of them are very poor – rickshaw wallahs, cart pullers or daily laborers who walk or bicycle home from work after dark. Ambulances are still unreliable or unavailable in many areas, so it often falls to bystanders or police officers to act quickly if crash victims are to be saved.

Getting to the roots of the problem often means understanding the history of an issue

In trying to comprehend why Shivam hadn’t been helped, Tewari discovered that a major problem was fear, and it went back a long way. During the 19th century, the British had established a law requiring India’s hospitals to record the identity of anyone who brought in a person for care. “It was used by the British police when someone brought an injured freedom fighter to the hospital, so they could track down others,” said Tewari.

Good research is essential to problem definition

Today, Indians remain reluctant to intervene on a victim’s behalf because they worry about legal harassment. In a national survey commissioned by the SaveLife Foundation, three-quarters of respondents said they would be unlikely to assist a road victim with serious injuries; of those, 88 percent said they feared repeated police questioning and a prolonged obligation to appear in court as a witness; 77 percent added that hospitals unnecessarily detained good Samaritans and refused treatment if money wasn’t paid. A vast majority of respondents agreed that India needed a “supportive legal environment” to enable people to help injured victims on the road.

It finally has one. In March, India’s Supreme Court issued a judgment requiring governments across India to comply with a set of guidelines to protect good Samaritans. Indians who assist others in need will no longer be required to disclose personal information or be subjected to questioning by the police; they cannot be detained at hospitals for any reason, and they are protected from civil or criminal liability. This could prove to be a major step forward.

The miracle was possible due to India’s tradition of judicial activism. After 2 years of fruitless lobbying of government

SaveLife started petitioning India’s Supreme Court directly. Article 21 of India’s Constitution states that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty. And Indian law states that if the government is not acting to preserve a constitutional right, the Supreme Court can order it to do so.

In 2014, the Supreme Court, persuaded by SaveLife’s petition, ordered the government to draft guidelines for a good Samaritan law. They were issued in May 2015 as an advisory to India’s states and union territories, but without legislative force. “We went to the Supreme Court to ask if it could exercise its special powers to convert these guidelines into the law of the land until the Parliament actually enacts legislation,” said Tewari.

The next stage is to ensure implementation, which is where SaveLife must switch tactics from insider advocacy to public awareness-raising, with lots of social media.

The foundation is raising money for a national radio campaign to inform the public. A website, GoodSamaritanLaw.in, and a Facebook page, provide platforms at which to learn about the law and how to help in an emergency, report harassment, or share stories of human kindness and courage.

Of course, this isn’t the whole solution – SaveLife is also training police officers in providing trauma care, and pushing for tougher enforcement of seatbelt and helmet laws. Beyond that there are major governance issues, but new technology can help:

In many parts of India, an untrained driver can receive a driver’s license simply by paying a bribe. “You don’t have to

Needs sorting

even appear for a test,” says Tewari. “It’s like ordering a pizza.” Another problem is standardization. “We don’t have a national driver database,” adds Pillai. “Each state issues its own license with all-India validity. A large number of drivers have multiple licenses. They don’t mind if you suspend one, they’ve got 3 or 4 more in their pocket.” India’s biometric identification system could solve that problem.

There are also positive examples from elsewhere

Globally, a combination of better education, enforcement and road management has been a key to improved safety. In preparation for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the Chinese government invested in bike lanes and mass transit, tightened licensing, and instituted major punishments for serious traffic offenses. Between 2005 to 2010, the country’s annual road deaths dropped by a third.

Like any good campaigning NGO, SaveLife has generated some pretty impressive Killer Facts:

He contrasted India’s intense focus on terrorism with its focus on road safety. The government spends 20 times more to combat terrorism, he estimated, while road crashes kill 75 times more people.

Final great advice from Tewari:

“It requires being flexible, understanding how the government works and thinks, being data driven. If you’re able to get your agenda to become part of their agenda, you can have big impact. But it takes a while for policies to come through, and to have impact — so you have to sacrifice instant gratification.”

July 5, 2016

Great new 110 page guide to humanitarian campaigning

Just been browsing through a brilliant new Oxfam guide to humanitarian campaigning. A treasure trove of 110 pages crammed full of wisdom, experience and 32 case studies on everything from addressing tribal conflicts in Pakistan to gender responsive work with Syrian refugees to influencing Australia’s humanitarian policy.

crammed full of wisdom, experience and 32 case studies on everything from addressing tribal conflicts in Pakistan to gender responsive work with Syrian refugees to influencing Australia’s humanitarian policy.

And no sign of an executive summary. Sigh. To be fair, it would be very hard to summarize, and the index is helpful. Anyway, in an effort to get the report out there a bit, even though I haven’t got time to try and write an exec sum (still less get it signed off!), here’s a taster:

Case Study: Influencing the Bangladesh government in response to floods

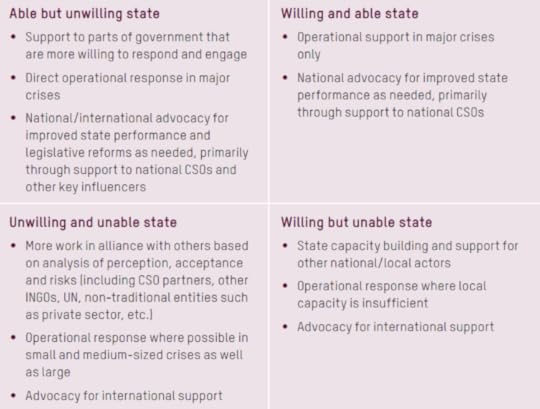

In 2011–12, floods in Bangladesh affected over 900,000 people and completely destroyed some 50,383 homes. Despite the scale of the emergency, the floods received little political or media attention nationally, and none internationally. Oxfam judged that while the government had the capacity to respond to the crisis at scale, its willingness to do so was constrained by a lack of public attention to the crisis and by fears that a full-scale response would be unaffordable.

To address this, Oxfam raised the public profile of the disaster by sending a professional photographer to cover the floods and exhibiting the photos at a high-profile Bangladeshi gallery. The exhibition, coupled with media coverage and lobby meetings around it, raised the profile of the disaster considerably with the public and political leaders. This increased profile resulted in more immediate government assistance to flood-affected communities in the form of grants, local government distributions and work to improve embankments and drainage, as well as longer-term initiatives to improve tidal river management.

At the same time Oxfam worked with communities, national civil society partners, key government officials and donors to demonstrate to the government that a significant proportion of the shelter needs of those displaced by the floods could be covered at relatively low cost. In partnership with the government, Oxfam supported partners to deliver 12,000 flood-resilient homes and latrines – 10 percent more than planned – under budget and in less than a year. In addition to the direct benefits of this shelter programme for communities, this initiative opened doors with national and local leaders, including local MPs and the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief. This increased political access enabled Oxfam and other civil society partners to influence the government’s commitment to delivering cost-effective and resilient shelter assistance at scale to people affected by floods in the future.

This experience shows the importance of engaging state authorities at multiple levels and in a variety of ways for greater influence – from lobbying and influencing through the media to relationship building through direct partnerships with government authorities.

Analytical Framework: International response options for varying combinations of state willingness and ability

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers