Duncan Green's Blog, page 116

June 15, 2017

Sex, serendipity and surprises – launching the State of the World’s Fathers

It’s Father’s Day on Sunday, apparently (my kids ignore it completely), so here’s Oxfam’s gender guru,

Nikki van  der Gaag

, reflecting on an impressive bit of advocacy

der Gaag

, reflecting on an impressive bit of advocacy

Sharing the housework means better sex. Now that I have your attention, let me explain.

This was just one of the findings in the first ever State of the World’s Fathers report, published in 2015. It collected research from all over the world to propose recommendations on how to ensure that men share unpaid care and domestic work equally with women.

Its premise was a feminist one, drawing on the work of economist Diane Elson – that recognising, redistributing and reducing domestic work and unpaid caring in families is one of the keys to gender equality. Women all over the world are still doing from 2 to 10 times more of this work than men – often on top of their paid work. This work is unpaid, unvalued and uncounted. If we want to achieve gender equality, this needs to change.

The idea for the report came to me when, as a consultant in 2013, I was evaluating the global MenCare campaign, whose aim is to promote men’s equal involvement unpaid care and domestic work as part of ensuring that they are equitable, nonviolent fathers and caregivers (and that includes adoptive or step fathers).

I realised that although there was a State of the World’s Children, a State of the World’s Mothers, a State of the World’s Girls, in fact a State of the World’s almost anything – there was nothing on fathers. It’s as if no-one was thinking about fathers or fatherhood at all. But that just wasn’t true. There were many individuals and organizations around the world ready and keen to come together around a platform to advance men’s caregiving and gender equality. They recognized that one of the reasons men are not involved in the home is linked to the ways in which we define masculinities, and to men’s power over women.

I realised that although there was a State of the World’s Children, a State of the World’s Mothers, a State of the World’s Girls, in fact a State of the World’s almost anything – there was nothing on fathers. It’s as if no-one was thinking about fathers or fatherhood at all. But that just wasn’t true. There were many individuals and organizations around the world ready and keen to come together around a platform to advance men’s caregiving and gender equality. They recognized that one of the reasons men are not involved in the home is linked to the ways in which we define masculinities, and to men’s power over women.

The original aim of the MenCare campaign, which published the first State of the World’s Fathers report, had been to reach 10 countries. By the time I finished the evaluation three years later, it had reached 25. And now, as I travelled to the second MenCare Global Meeting in Belgrade last week, and the launch of the second State of the World’s Fathers report (also being launched in New York and Geneva), there are more than 40 countries – and the numbers are growing all the time. The idea of involving fathers as a first step into gender equality struck a chord across the world in ways that we had not expected or anticipated.

Interestingly, many of those who were involved in that first phase of the MenCare campaign were not working with men in particular. Some were child development organisations. Others focused on women, often at grassroots level. For example, those working with women in abusive relationships found that the women they worked with didn’t necessarily want their husbands and partners to go to prison (although some did). What they wanted was for the violence to stop; they wanted more equal relationships, and they wanted men to be more involved in the home and with their children. So they started to work with couples and with men as well as women.

The success of the report made me reflect on the surprisingness of change and the unexpectedness of impact. We knew that this was something exciting and new, and that it built on increasing interest in engaging men on gender equality, with many international organizations shifting their focus to see men and boys not as barriers, but as potential partners in advancing gender equality.

But we could never have anticipated that we would launch it at the United Nations in New York with Chelsea Clinton and in 10 cities around the world. Nor that there would be more than 10 regional and country reports in many different languages – I have just been given the one in Russian -, and the Latin American one launches this month. Or that organizations from Chile to South Africa, from Indonesia to Serbia would take hold of the idea, and take ownership of the data, making recommendations for their own countries and contexts.

and in 10 cities around the world. Nor that there would be more than 10 regional and country reports in many different languages – I have just been given the one in Russian -, and the Latin American one launches this month. Or that organizations from Chile to South Africa, from Indonesia to Serbia would take hold of the idea, and take ownership of the data, making recommendations for their own countries and contexts.

Nor did we think there would be so much media interest – from the New York Times to BBC Woman’s Hour, The Guardian to Vanity Fair – and over two billion views and 41 million tweets on the 2015 report’s hashtag, #SOWF. The report has begun to contribute to what we hope will be the beginning of policy change – there have been new paternity and parental leave policies and bills in at least three countries to date. Recently, the UN set a target on unpaid care and domestic work as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. It also proclaimed that states and employers should support men sharing care and invest in services and infrastructure to support caring. Housework is an invisible workforce – an old refrain but with a new twist – many more men now recognise that they are the ones ‘under-participating in the labour force’, when unpaid domestic work is counted.

Our timing was also serendipitous– for example, the fact that Chelsea Clinton had just had a baby, and that so many organizations around the world were looking for a way to take their programming work further and were therefore keen to join up to build their advocacy and to make links with others.

Being a better father, a better parent, a better person, and, as part of that, working on how to value and share the unpaid care and domestic work more equally, is an idea that many women and men all over the world are now travelling back from report launches to their homes and offices to continue to put into practice.

This is not just a matter of turning bad or mediocre fathers into better ones, but nothing less than a complete redistribution of power in the home and outside it. Which is better for gender equality, better for women, better for men, and better for children. And better for sex.

June 14, 2017

What can Activists do in a Political Downturn?

The recent discussions with the International Budget Partnership also got me thinking about the options facing activists in political

Recognize this?

downturns. IBP sees these as potentially multiple: the crackdown on civil society in increasing numbers of countries is closing the space for budget activism, and there may also be a kind of ‘peak transparency’, where the issue passes the summit of the hype curve and descends the other side, either into the dustbin of history or (one hopes) to a plateau where it is both genuinely useful and no longer over-sold. We were meeting in Washington, and the conversation was also probably affected by the depressing state of US politics on these issues.

Trawling back through the blog, I stumbled across this 2012 piece from Central America, covering similar topics at a more local level. The downturn there was driven by drug trafficking, elite capture, and the retreat of the progressive Catholic Church. Some of the possible directions sketched out there also came up at IBP:

‘Pursue a defensive strategy, trying to minimise the reversal of past gains on say, women’s rights or agrarian reform. Stay faithful to our traditional partners, helping them weather the downturn.’

To those I would add some other options:

Positive Deviance/pockets of progress: even in a downturn, there will be good stuff happening, but it may not be in the usual places, or involve the usual suspects. As I blogged recently, IBP has identified litigation, the rise of activist Supreme Audit Institutions and working below the national level with progressive cities or provinces as grounds for much-needed optimism.

Target durable institutions that can keep the flame alive during the downturn. Campaigns and NGOs can be short-lived and driven from one issue to the next. University departments endure. So if public activism isn’t getting very far at the moment, it might be better to think about how to influence existing university curricula (eg on public financial management), or set up training institutions for future generations of civil servants and activists on transparency/accountability/budget-related issues. Same goes for trade unions and other more long-lasting institutions.

Broaden the coalition and the language. During the upturn, work on a topic professionalizes, becoming more specialist. That creates a cohort of insiders that can work together to influence a system that wants to be influenced. If the system turns hostile, that degree of specialism ceases to be useful – you could end up with a clique of geeks that no-one (either in power or out) understands or listens to. So a downturn may be the right time to look for wider narratives, build new ‘myths’, make links with wider groups of people by, eg making connections with religious concepts of stewardship and tithing. For example, look at what the Jubilee 2000 campaigners achieved using pretty obscure Biblical stories to build the movement for debt relief from the mid 1980s, at a time when Thatcherism/free market fundamentalism dominated official public debates.

Broaden the coalition and the language. During the upturn, work on a topic professionalizes, becoming more specialist. That creates a cohort of insiders that can work together to influence a system that wants to be influenced. If the system turns hostile, that degree of specialism ceases to be useful – you could end up with a clique of geeks that no-one (either in power or out) understands or listens to. So a downturn may be the right time to look for wider narratives, build new ‘myths’, make links with wider groups of people by, eg making connections with religious concepts of stewardship and tithing. For example, look at what the Jubilee 2000 campaigners achieved using pretty obscure Biblical stories to build the movement for debt relief from the mid 1980s, at a time when Thatcherism/free market fundamentalism dominated official public debates.

Stay ahead of the curve: Try and renew/refresh/anticipate the issues and strategies that could keep the interest in transparency and accountability alive, despite the downturn. That could include a bit of entryism and bandwagoning: In the downturn, identify where the political energy is bubbling up, and try and find an angle for your issue. Migration and budgets? Brexit and budgets? All sorts of risks of doing the wrong thing, damaging your credibility etc, but worth looking at.

There’s always a temptation that in a downturn, organizations abandon their area of expertise, casting around for something that still gets traction, headlines or funding. That could be a real loss, if it endangers what organizations like IBP have achieved through decades of struggle, so this topic seems pretty important right now – any thoughts?

June 13, 2017

Memory, Wisdom and Mentoring: what do practitioners need from academics, beyond research papers?

Spent an interesting, if bleary (the morning after the UK election) day at Birmingham University’s International Development Department last week. We heard from some of the top research going on there on topics such as the Political Economy of Democracy Promotion, or the Developmental Leadership Program, but what really piqued my interest was a new take on that old chestnut, how researchers and practitioners can work better together.

Birmingham is home to the Governance and Social Development Resource Centre (GSDRC), which, among other things, acts as a ‘Research Helpdesk’ providing rapid-response research on questions from donor agencies and partner governments in developing countries. Set up with initial funding from DFID, GSDRC has been going since 2001, and has a pile of invaluable literature reviews and topic summaries online (I used loads of them while writing How Change Happens).

But when GSDRC manager Brian Lucas reflected on what the Centre has learned in 15 years of trying to bridge the  academic-practitioner divide, what caught my attention was the stuff that goes beyond simple ‘research products’. GSDRC user surveys show that in addition to well-researched and accessible papers, practioners would really like more ‘institutional memory support’ – aka ‘can anyone tell us what we have previously done in this country/on this subject?’

academic-practitioner divide, what caught my attention was the stuff that goes beyond simple ‘research products’. GSDRC user surveys show that in addition to well-researched and accessible papers, practioners would really like more ‘institutional memory support’ – aka ‘can anyone tell us what we have previously done in this country/on this subject?’

It may seem odd that aid workers should need a resource centre to tell them what their own organizations have been up to, but high staff turnover + constant restructuring induces a deep level of institutional amnesia in most aid organizations. I would add to the broader issue of topic memory – I once ran into Oxfam’s gender adviser from Afghanistan at Dubai airport, who told me as she was leaving after a two year stint, that she was now the longest serving expat gender specialist in Kabul. Organizations like GSDRC can identify the sources of long term wisdom among local or international academics, or retired aid workers, who can help fill the gap, and help put them in touch with harassed aid workers desperate for advice and support.

It may be that practitioners actually need academic mentors more than yet more research (my words, not Brian’s!) Users want to tap into unpublished (informal, tacit) knowledge, wisdom and above all advice. They want to talk to someone who has tried a similar thing tp whatever it is they are planning, or at least has watched it play out before. Unlike aid workers, academics tend to stick to the same topic through their careers so could be ideal at playing this kind of role, but currently there are few incentives for them to do so. Instead, they feel under pressure to get on with writing the next journal paper, not chat to aid workers on skype.

Anyone need a mentor?

But these days, academics are also being pushed by processes like the Research Excellence Framework to demonstrate that their work has impact, so now seems like a good time to try and realign those incentives. For example, the university system could agree to make mentoring practitioners a bit like supervising PhD students. Academics would be credited in some way for taking on a limited number of practitioners and supporting them over time. I’d be interested in hearing from those in the know about whether this has been tried and/or how it could be institutionalized.

In return for mentoring/accompanying practitioners, academics could be given access to new sources of data from monitoring and evaluation of aid programmes or other sources – gold dust for any academic career.

And what of the practitioners? Everyone in the aid business says they want time to read and reflect, so the standard answer is often ‘why not pack them off to a university for a week every year so they can do just that?’ But it’s not that simple. The change of rhythm between activism and reflection can be jarring. When we sent our senior advocacy team to IDS for a reading week a few years ago, IDS was horrified by their attention deficit issues – they just couldn’t stay off their blackberries. A mentoring scheme would respond to the needs and rhythms of the practitioner, rather than the need to fit around university timetables (eg by boosting their coffers through summer schools).

Any other ideas for supporting relationships, wisdom banks and memory, not just churning out the lit reviews and case studies?

June 12, 2017

Thinking and Working Politically: where have we got to?

Spent a day with the TWP crew recently. Chatham House Rules, so no names. Like its close relative and overlapping network, ‘Doing Development Differently’, TWP urges aid organizations to stop trying to impose rigid blueprint/’best practice’ approaches, paying far more attention to issues of power, politics and local context. The driving force has mainly been staff in bilateral and multilateral aid donors, researchers from universities and thinktanks, the odd NGO (very odd, in my case) and ‘implementing organizations’ – the low profile, but big budget private companies that actually run a lot of the big aid programmes.

Spent a day with the TWP crew recently. Chatham House Rules, so no names. Like its close relative and overlapping network, ‘Doing Development Differently’, TWP urges aid organizations to stop trying to impose rigid blueprint/’best practice’ approaches, paying far more attention to issues of power, politics and local context. The driving force has mainly been staff in bilateral and multilateral aid donors, researchers from universities and thinktanks, the odd NGO (very odd, in my case) and ‘implementing organizations’ – the low profile, but big budget private companies that actually run a lot of the big aid programmes.

TWP has been meeting and talking for a few years now, and this seminar provided a chance to take stock. Which was surprisingly hard – reality is messy, with a mix of positive and negative trends all interacting, so let’s identify a few.

First, the positive: it’s growing – the meeting was full, with a waiting list of disappointed TWPistas. One speaker claimed (slightly alarmingly) that the ‘TWP chip’ is now in most aid workers’ heads. The World Bank’s flagship report, the World Development Report 2017, not only covered TWP issues but even name-checked the network (Box 9.4 on page 271, since you asked).

But that is set against a wider panorama of aid under attack (the rise in populism/nationalism, reflected in institutional setbacks like the dissolution of Ausaid, one of the network’s original drivers, USAID under fire, and who knows what fate awaits DFID).

But that is set against a wider panorama of aid under attack (the rise in populism/nationalism, reflected in institutional setbacks like the dissolution of Ausaid, one of the network’s original drivers, USAID under fire, and who knows what fate awaits DFID).

What’s interesting is that those setbacks create opportunities as well as threats for TWP. As I found on my recent trip to New Zealand and Australia, where aid budgets are now managed by foreign ministries, diplomats readily ‘get’ TWP. In contrast, the professionalization/technification of aid has seen it become dominated by formulaic ‘planner not searcher’ approaches to economics and medicine that usually ignore/downplay the importance of power and politics.

One of the standout themes from the discussion was the desire of TWPistas to move ‘beyond governance’, ‘beyond programmes’ and even ‘beyond aid’.

Beyond Governance: TWP originated among frustrated state builders in governance teams, seeing how little success was achieved by traditional approaches to introducing institutional blueprints from other countries. But governance is a bit player in aid, compared to the big money items like economic development, infrastructure, health or education. How to get out of the governance ghetto to influence the big stuff? In DFID the governance team (with the unfortunate acronym of GOSAC), has just been transferred to the Economic Development Directorate creating a perfect test case – will TWP thinking influence the growth/markets people or be squeezed out by them?

Beyond Programmes: Rather than run programmes, donors have always wanted to influence government policies. In the past, this was often through pretty unsuccessful attempts to impose reform conditions on their loans. As aid falls, in absolute or at least relevant terms compared to other sources of cash, imposing conditionalities is likely to be even less successful. Now donors say they want to influence policy through a more respectful approach to dialogue and persuasion, rather than arm-twisting.

This reminds me of the growing interest in advocacy among NGOs and all the stuff I wrote about in my book – systems thinking, stakeholder mapping, power analysis, building change coalitions, seizing windows of opportunity (critical junctures) presented by crises, shocks and changes of leadership etc. But there’s an obvious problem with governments following suit – official donors using advocacy to influence sovereign governments is a political minefield and could provoke a serious backlash. Exhibit A: Russian interference in the US elections.

Beyond Aid: as aid budgets fall, or are raided by other departments, it becomes more important to influence what  other branches of government are up to. This could be very interesting (see my visit to Aus/NZ above), but only if aid officials respect and listen to their counterparts among the diplomats and soldiers. Bouncing up to them and saying ‘hey it’s all about power and politics, let me explain it to you poor simple folk’ is unlikely to impress. In fact, we should start by asking them how they understand TWP. We might learn something.

other branches of government are up to. This could be very interesting (see my visit to Aus/NZ above), but only if aid officials respect and listen to their counterparts among the diplomats and soldiers. Bouncing up to them and saying ‘hey it’s all about power and politics, let me explain it to you poor simple folk’ is unlikely to impress. In fact, we should start by asking them how they understand TWP. We might learn something.

There was a good discussion on technical assistance v TWP. You can’t just abandon TA and shift to advocacy for a whole bunch of reasons. Not least, TA buys you credibility with host governments – they want your skills and knowledge, not your TWP – and then the trust and space created by TA allows you to operate and do more political stuff. But ‘presenting yourself as technical and apolitical is political’, a tactic of ‘strategic naivete’, as one speaker put it. And who are we trying to fool? Do we really think host governments will buy the whole apolitical thing?

Finally, an intriguing discussion on ‘beyond Westphalia’, i.e. applying TWP beyond the world of formally constituted national governments. One participant told me she is trying to take her organization above, below and beside national governments: above to focus more on how to influence the international system that increasingly constrains government action; below to subnational units such as City administrations and/or local civil society organizations (not just international NGOs); and beside to take in other forms of power and ‘public authority’. All good, but hard work when the aid business is dominated by the organizations and relationships of national governments.

Conclusion? TWP is in good health, faces some huge challenges, and needs to move asap to consolidating its position with more concrete work, both in terms of research on how TWP works in specific areas (eg gender, conflict or learning how to measure when TWP is having impact) and building up the support network that aid workers need to implement TWP in practice.

Other participants – feel free to emerge from the Chatham House shadows and add your bit…

June 11, 2017

Links I Liked

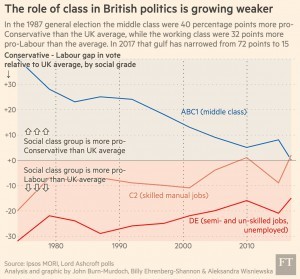

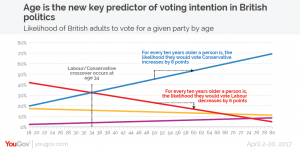

The UK elections produced some good satire (The Book of Jeremy Corbyn was one of my favourites, c/o The New Yorker, and not a bad exec sum of the election campaign) and a lot of graphs. These were two of the most

The UK elections produced some good satire (The Book of Jeremy Corbyn was one of my favourites, c/o The New Yorker, and not a bad exec sum of the election campaign) and a lot of graphs. These were two of the most interesting – this election (and perhaps future ones) was about age more than class. The class graph is actual, the age one is voting intention pre-election – anyone seen an actual? Click to enlarge.

interesting – this election (and perhaps future ones) was about age more than class. The class graph is actual, the age one is voting intention pre-election – anyone seen an actual? Click to enlarge.

‘Development is not a science and cannot be measured. That is not a bad thing’. Michael Kleinman got a lot of measurement geeks pretty riled with this post

Albert van Zyl at the International Budget Partnership tries to identify IBP’s strategic rules of thumb. Fascinating but since when am I a ‘polished polymath’?

This mowing man v tornado pic went viral. Echoes of Voltaire: ‘we must take care of our garden’. A metaphor for our times?

This mowing man v tornado pic went viral. Echoes of Voltaire: ‘we must take care of our garden’. A metaphor for our times?

Crisis is the natural state of ‘Liberal Democracy’, so could everyone please chill? Another great piece (+ lovely writing) from Branko Milanovic

Boring name, exciting substance. The rise of ‘municipalism’ as a local → global political movement. National governments are so last 2016.

World leaders portrayed as refugees by Syrian artist Abdalla, now a refugee in Belgium. ‘I wanted to take away their power and give them back their humanity’. Beautiful and very thought-provoking (and another good reason for wanting Al Jazeera to survive)

June 7, 2017

How will we know if the SDGs are having any impact?

As long time readers of the blog will know, I’ve been a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) sceptic since long before they were even agreed. However, I’ve been hearing a fair amount about them recently – people telling me that governments North and South, companies and city administrations are using them to frame public commitments and planning and reporting against them. So maybe it’s time to take a second look.

agreed. However, I’ve been hearing a fair amount about them recently – people telling me that governments North and South, companies and city administrations are using them to frame public commitments and planning and reporting against them. So maybe it’s time to take a second look.

My problem with the SDGs is not with the subject matter – all very creditable – or the number of targets, which bugs some people, but not me. It’s the design, and in particular, the lack of analysis on how they could have political impact. For me, the key question for any international instrument ought to be traction – will this or that convention, undertaking etc (of which there are hundreds, if not thousands) influence the day-to-day behaviour of governments, sub national bodies, private sector or others and how? And yet weirdly, this was never raised during the design of the SDGs, which instead were dominated by adding more topics to the Christmas Tree of SDG issues, and long discussions about indicators, data and metrics.

Even odder, this question has barely been asked of their successor, the Millennium Development Goals. In a classic fudge of causation

Causation v Correlation 101

and correlation, the MDGistas said ‘look, extreme poverty has halved, the MDGs are a success!’ Yet much of that reduction was down to China, and no-one can credibly claim that it was the MDGs that got the Chinese Communist Party out of bed every morning to transform the Chinese economy.

There are a few exceptions I’ve managed to collect in response to repeated rants: Alice Evans showed how MDG5 on Maternal Health prompted the Zambian government to take action for fear of reputational damage; May Miller Dawkins wrote a nice paper on what the SDGs could learn from international environmental agreements in terms of design/traction. Moizza Binat Sarwar studied MDG implementation in five low and middle income countries (Indonesia, Liberia, Mexico, Nigeria and Turkey), largely by interviewing staff of relevant ministries. When Columbia University’s Elham Seyedsayamdost surveyed 50 countries’ implemention of the MDGs, she found that whether the goals were reflected in plans or not, they did not have any apparent influence on how governments spent their money. All great stuff, but hardly a body of research that matches the importance of the issue – a very odd lacuna indeed.

Now the same thing looks to be happening again. Lots of talk of monitoring and reporting against the SDG indicators, and as far as I can tell, no attempt to establish whether the SDGs (rather than other factors) are responsible for changes to those indicators.

So what would an ‘SDG politics watch’ look like?

First the data: we need to know which bodies are using the SDGs in their planning, budgeting, reporting etc. Maybe we could crowdsource this – governments, NGOs, academics etc can all upload evidence to some kind of WikiSDG so we can start to build up a picture of formal commitments

But that is nowhere near enough – how to distinguish between lip service and genuine traction? And why do the SDGs get traction in

Traction or Lip Service?

some places and not others? That’s where the academics could get stuck in. Alice Evans at Cambridge is issuing an open invitation to supervise a good PhD student on this topic. In her words ‘It’s not just about whether governments use the SDGs in their policy documents, but their attitudes towards these goals: do they dwell on issues they previously didn’t because they are concerned about regional benchmarking? Do civil servants in meetings spend time looking at SDG 9.ii (whatever that is), and put pressure on provinces to improve this indicator, or just whizz through it. Do parliamentarians raise these issues?’

Why does this matter? Because understanding when/how an international instrument has traction ought to be the starting point for tweaking SDGs, and designing future instruments that work better. If for example, we were to identify regional rivalry as a key driver in state action, we would put much more emphasis on reporting in regional league tables. If the key to impact is civil society picking up and using the instruments, then (as in the SDGs) it becomes even more pressing to involve CSOs in monitoring and reporting, as well as initial design. And so on.

Thoughts?

Previous rants on this topic include one paper and lots of blogs:

Paper: How Can a Post-2015 Agreement Drive Real Change? The political economy of global commitments

Posts:

Hello SDGs, What’s Your Theory of Change?

How will the SDGs differ from the MDGs?

The SDGs are just getting interesting – what needs to happen next to make them have impact?

June 6, 2017

Empowerment and Accountability in Messy Places. Need your advice on Nigeria, Pakistan, Myanmar and Mozambique.

My post-book research plans are shaping up, so it’s time to ask for your advice. As well as the work I blogged about recently on Public

Myanmar

Authority in fragile/conflict-affected settings, I’m doing some research with Oxfam and Itad on how ‘adaptive management’ plays out in those same settings. Here’s the blurb:

‘There is much hype and attention given to new models of development programming that are iterative, adaptive and politically grounded and whether they show greater promise than more traditional development approaches. Among the myriad of possible models, the current empowerment and accountability programming paradigm suggests that external actors should think and work in a politically smart way, work with the grain, make small bets, adopt problem driven locally led approaches and as a result do development differently. These approaches or principles offer new or repackaged signposts to programming success, including developing a stronger understanding of how political, economic and social contexts play out in situations of complexity and fragility and a commitment to learning by doing.

Evidence of adaptive programming is however thin on the ground – in relation to how such approaches have been put into practice, what has worked and not worked, the underlying factors that enable their effective implementation, how they contribute to success and the added value they provide. The current literature is relatively sparse and appears overly removed from the reality that practitioners face and is couched in a ‘donor-centric’ language that frontline workers, who ultimately must translate concepts into delivery, struggle to understand.’

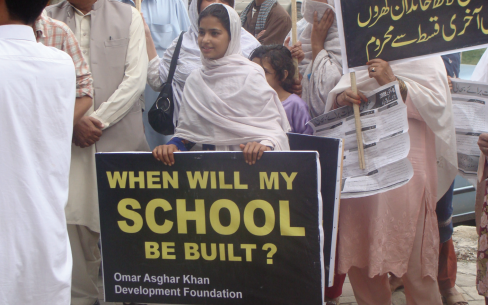

Pakistan

This is part of a much bigger research programme called ‘Action for Empowerment and Accountability’, exploring the nature of social and political action in fragile, conflict, and violent settings (FCVS). I’ll be looking at how the new aid approaches (adaptive management etc) that I’ve written about so much on the blog play out in these settings, and what differences (if any), they imply for ‘frontline workers’, whether in aid donors, or their partner organizations.

Angela Christie of Itad and I are looking for suitable case studies in Nigeria, Mozambique, Pakistan and Myanmar. We’ve got some initial candidates, but thought it would be worth canvassing FP2P readers for suggestions, especially on which programmes might be worth taking a look at.

Although not set in stone, the selection criteria for the case studies are:

Within one of the four countries

Focussed on Empowerment and Accountability

Must take place in FCVS (including pockets of fragility/conflict within otherwise stable countries)

Must meet the characteristics of adaptive management, within their official aims or (prominently) in their practice

Must be live, and at least two years into implementation

Must include commitment to explicit and ongoing political economy analysis

Can include both single donor and multi donor programmes

And just in case you were wondering what this ‘adaptive management’ malarkey involves, here’s Angela’s admirably succinct description:

Decentralised decision making (decision-making authority as close to the frontline staff and partners as possible)

Experimentation (since uncertainties require ‘small bets’)

Consideration of context as well as intervention within monitoring processes (since context is likely to be complex and volatile in FCVS)

Effective integration of MEL into management systems (MEL systems are decision orientated)

Fast feedback/learning loops (the more unstable a system, the faster feedback is required)

Flexibility in design and implementation (adaptation not just based on learning by doing but on reflections on assumptions relating to both causal pathways and context)

Over to you – what programmes would you recommend and why? If you’d rather use email than leave comments, write to me at dgreen[at]oxfam.org.uk.

June 5, 2017

Are top academic and aid institutions getting away with bad writing?

Guest post from the ODI’s Caroline Cassidy

I almost choked on my porridge last week when I read about the World Bank’s chief economist Paul Romer being sidelined for wanting his team to communicate more clearly. I re-read the article to check I wasn’t missing something, but there it was: Romer had pushed his staff to write more clearly ‘asking for shorter emails and insisting that presentations get straight to point’. He also would not clear a final report if the frequency of ‘and’ exceeded 2.6%.

I’ve spent years working with academics, policy-makers and colleagues, trying to get them to think differently about communicating evidence. The climate has improved significantly in that time: donors are tougher on their recipients; impact is on the tip of everyone’s tongues; and communications is widely recognised as being more than just dissemination.

Yet, it was only a few years ago that a study found that more than 30% of the World Bank’s pdf reports hadn’t been downloaded in five years. In 2015, a further study by Stanford University’s Literary Lab found that World Bank publications are in ‘another language’. (I should caveat that I read a beautifully written World Bank report the other week so it’s not always the case).

Why isn’t an influential and world famous institution like the World Bank producing well-communicated research? Why isn’t it leading as an example to others? Isn’t a key role of the World Bank to find sustainable solutions that reduce poverty and build shared prosperity in developing countries? Surely strong communications is a critical piece of that puzzle.

Maybe World Bank staff feel protected from this broader drive to improve communications – after all, they have the reputation and status to get away with it. Writing imprecisely can feel like a safety net. In January, Romer published his internal piece on why good writing is so critical. In it he states that ‘the problem with vague writing is that it lets an author convey a false impression yet retain plausible deniability when someone tries to verify a claim’. Clear writing is a way to build trust with your audience; it’s the bedrock to getting people to listen to you. As Romer puts it ‘‘Writing is the bottleneck that holds back the rate of diffusion of ideas’.

Maybe World Bank staff feel protected from this broader drive to improve communications – after all, they have the reputation and status to get away with it. Writing imprecisely can feel like a safety net. In January, Romer published his internal piece on why good writing is so critical. In it he states that ‘the problem with vague writing is that it lets an author convey a false impression yet retain plausible deniability when someone tries to verify a claim’. Clear writing is a way to build trust with your audience; it’s the bedrock to getting people to listen to you. As Romer puts it ‘‘Writing is the bottleneck that holds back the rate of diffusion of ideas’.

Last month, thousands of scientists took to the streets globally to fight back against the rise of anti-evidence. These sort of news stories about academics rejecting communications just aren’t helping. With many governments becoming increasingly reluctant to finance development of poorer nations, surely it is more important than ever that researchers do as much as they can to bridge the gap between research, policy and the public. This includes making research less elitist and more accessible to policy-makers. I am not saying that researchers have to directly influence policy, but they do have to communicate their work clearly so that it can be useful to others.

There is simply no excuse anymore to bury our heads in the evidence sand or hope ‘post-truth’ politics will all blow away. And organisations like the World Bank should be leading the way. If it starts with reducing the number of times you use ‘and’ in a report, then so be it.

(The use of ‘and’ in this blog is 2.3% of total words – phew!)

George Orwell’s 6 rules for writing (from Politics and the English Language)

Paul Romer’s key messages on writing

Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.Never use a long word where a short one will do.

If it is possible to cut out a word, always cut it out.

Never use the passive where you can use the active.

Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

The quality of written prose should be higher in documents that will have many readers.Look at the first 7 or 8 words in a sentence. If you do not see a character as a subject and a verb as a specific action, you have a candidate for revision.

Keep the use of ‘and’ to a minimum (below 2.6% of total words).

If an author devotes an extra hour to shortening and improving a text, this might save an additional minute for each reader. If there are even 100 readers. An extra hour of editing that saves 100 minutes of reading reduces the total time required for communication.

Caroline Cassidy is Strategic Communications Manager in ODI’s Research and Policy in Development (RAPID) team

June 4, 2017

Links I Liked

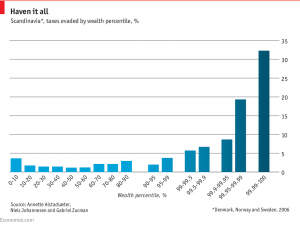

New research based on two big data dumps – Swiss leaks and the Panama papers, shows that even in more-progressive-than-thou Scandinavia it’s the very top (0.01%) that use tax havens to avoid paying their share. Conclusion? Inequality is much worse than we thought.

Scandinavia it’s the very top (0.01%) that use tax havens to avoid paying their share. Conclusion? Inequality is much worse than we thought.

Why is France a standing affront to neo-liberals? Lovely writing from Craig Murray, h/t Max Lawson

Excellent summary of the evidence to date on the impact of different kinds of cash transfer, and suggestions for future research

Handy guide to the international commitments in manifestos of the ‘main UK parliamentary political parties’ ahead of this Thursday’s election

Summary of the numerous debates on universalism v targeting from Raj Desai at Brookings

Brazilian human rights NGOs are weaning themselves off foreign aid and building domestic donor bases.

Natural experiment: Latin America’s massive Odebrecht scandal – a big construction firm gets caught bribing lots of governments at the same time. Perfect chance to compare how different governments respond.

A few aid donors are trying to shift social norms by funding soap operas and reality TV shows with a social message (Oxfam has done a top job in East Africa with Female Food Heroes). I suspect a lot of these are worthy flops, but get them right and the reach is amazing. India’s Main Kuch Bhi Kar Sakti Hoon – I, a woman, can achieve anything has had over 400 million viewers in its first two seasons. Its storyline includes acid attacks, domestic violence and abortion of female foetuses – the accompanying hotline got 1.4 million calls in the first season alone. Props to DFID for part-funding it.

And here’s the first episode, with English subtitles

June 2, 2017

There was never a better time for the US to leave global climate talks

Op-ed by

Tim Gore

,

Head of Policy, Advocacy and Research of Oxfam’s GROW Campaign

Oxfam began campaigning for a global climate agreement in 2007. We have sent teams to every COP and every single negotiating session ever since. Along with many partners and allies, we have held stunts, published papers, generated media coverage, lobbied incessantly and mobilised many many thousands of people to push governments and companies to do more at the UNFCCC for a decade.

So Trump’s announcement this week hurts us all. We know that the people who will pay the price of every delay to the climate action we need are the communities we work with in every country every day.

For many who have been part of this struggle, the real kicker is knowing the US negotiated for years to get an agreement designed to be palatable to US domestic politics. After the US succeeded in watering down the Kyoto Protocol 20 years ago before refusing to ratify it, this feels like history repeating itself. Certainly the Paris Agreement is littered with evidence of US intransigence – attempts to agree fair share principles were blocked, approaches to addressing loss and damage neutered and climate finance provisions limited to a drop in the ocean of needs – despite Trump’s ludicrous claims to the contrary.

Bali 2007

It’s tempting then to wonder whether the world should have resolved to build a global climate agreement without the US years ago. Imagine if at the Bali conference in 2007, when the Bush administration’s delegation was openly jeered for blocking a roadmap to a new agreement, the rest of the world had decided to go ahead without them. Would there have been a better outcome in Copenhagen two years later? Could the Paris Agreement have been stronger if the US had either chosen or been forced to walk away at any point during or after the Durban conference in 2011?

I believe the answer is no. The fact is the world was not ready to go it alone without the US at any point over the past ten years of climate negotiations. But it is now, here’s why.

Firstly, because as we have been saying since Paris, the pendulum of climate leadership has been swinging towards the global South for some time. China’s emissions have seemingly peaked – almost unthinkable at the time of the Copenhagen conference – and both China and India are cancelling swathes of planned coal fired power stations. Their investments in renewable energy are staggering – boosted by the price of solar and wind technology dropping like a stone. The Climate Vulnerable Forum has pledged to achieve 100% renewable energy in their economies by 2050. These are game-changers that mean the foundation is laid for new international alliances to lead the global climate fight in the years ahead.

The EU and China have already signalled their intent. New South-South institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank hold huge promise to accelerate investment in renewable energy. The commercial, trade and diplomatic partnerships that will be built will leave no-one in any doubt that far from putting America first, Trump’s move puts the US last in the race to build a more sustainable economy.

Second, because global climate politics now takes place beyond the confines of relations between nation states. Cities, sub-national units (including the States in the US) and companies all increasingly understand they too have responsibilities to act, or are being pushed to do so by citizens. We’re going to need them in the US and everywhere else not only to drive deep emissions cuts at record speed in the next few years, but also to contribute the resources needed in countries from Afghanistan to Zambia to leave fossil fuels in the ground, adapt to the climate impacts they are already battling and pay for the loss and damage that cannot be prevented.

And third, because there is a movement of people in the US that will not let their government get away with this madness for very  long. They put together the biggest march on climate change the world has ever seen. They are putting their bodies on the line to block coal plants and pipelines from being built. They are driving fossil fuel interests out of Washington DC. They are demanding a response from their elected representatives that is actually commensurate with the scale of the crisis we face. They are standing side by side with those fighting all forms of social injustice. And I don’t believe for one second they are going to stop, whether the US is in the Paris Agreement or not.

long. They put together the biggest march on climate change the world has ever seen. They are putting their bodies on the line to block coal plants and pipelines from being built. They are driving fossil fuel interests out of Washington DC. They are demanding a response from their elected representatives that is actually commensurate with the scale of the crisis we face. They are standing side by side with those fighting all forms of social injustice. And I don’t believe for one second they are going to stop, whether the US is in the Paris Agreement or not.

We couldn’t have said any of these things at any other point in recent memory. So while the US government rowing back from its international responsibilities on climate change is not a new story, the truth is that we have never been better placed to respond to Trump’s decision on Paris. Oxfam will be debating internally and with all our partners, allies and close friends that have been part of this journey for climate justice what part we can play in writing the next chapter. We will not take this lying down, we will persist, and we know we are far from alone.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers