Duncan Green's Blog, page 115

June 30, 2017

Shouting or cooperating? What’s the best way to use indexes to get better local government?

Went to an enjoyable panel at ODI last week, with the wonderful subtitle ‘Shouting at the system won’t make it  work!’. It presented new research on how to improve the accountability of local government in Tanzania. Here’s the paper presented by two of the authors, Anna Mdee and Patricia Tshomba, the first of a series.

work!’. It presented new research on how to improve the accountability of local government in Tanzania. Here’s the paper presented by two of the authors, Anna Mdee and Patricia Tshomba, the first of a series.

The research is about how you construct a local government performance index that means something to local people. It’s research rather than consultancy, so the task is not to produce an index for others to implement, but to work out how to do it.

And it turns out (surprise surprise) to be really difficult. According to one of the authors, Anna Mdee ‘We found a big gap between theory and practice. Practice is much more multiple, with parallel negotiations, the remains of a one party system, the formal state, extremely influential faith organizations, civil society organizations. So it’s hard to establish who is being held to account. We found lines of accountability, but also ‘lines of blame’ – everyone blames everyone else, not always along the same lines. Government tries to push blame all the way down to the villages (which have massive responsibilities and no resources).’

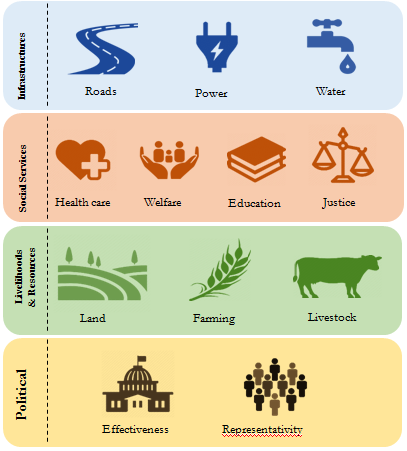

The researchers opted for building an index as a starting point for triggering conversations about problems and how to fix them. Through a combination of workshops, focus groups and interviews, they identified those problems as:

Politicians are not concerned with peoples’ problems

Councillors and other local representatives feel they are misjudged

Lack of communication, openness, cooperation and togetherness

No platform to bring together stakeholders

Lack of important documents and knowledge

Weak culture of reading

Shortage of funds (‘District officials reported that the social welfare department has many activities and manpower but has only a budget of 1 million Tanzanian Shillings (approx. £360) per month’).

Examples of indicators

They used the conversations to identify a draft set of indicators, went back to consult and refine them, and came up with the ones in the diagram, with the litmus test being ‘if you had this, would it make any difference? Would anyone use it?’

The purpose of this is definitely not advocacy of the finger-wagging variety, but rather ‘getting beyond the blame game’: ‘We see potential in using a Local Governance Performance Index as a collaborative problem-solving tool, that helps to move from a list of complaints about problems that local officials and representatives have limited capacity to resolve, to a collective understanding between citizens and local government about where blockages lie, and what they can do together to overcome them.’

Which is really interesting and echoes in part our own governance work in the Chukua Hatua programme: we started off helping local communities ‘demand accountability’ from local officials, but moved to something more collaborative when those officials said they would love to be more accountable, but had little idea what their roles and responsibilities actually were.

I’m a sceptic on finger wagging (see one of my favourite cartoons on ‘speaking truth to power) and love the focus on  collective problem solving, on getting local people to identify the right indicators and the acknowledgement of the complexity of local governance. But I did worry that by aiming purely for using the index to trigger conversations, they were missing a trick.

collective problem solving, on getting local people to identify the right indicators and the acknowledgement of the complexity of local governance. But I did worry that by aiming purely for using the index to trigger conversations, they were missing a trick.

In particular, they reject the idea of a single composite index, because they think that would prompt a slide into attempts to ‘game’ the index, and this would lose the emphasis on collective problem solving. And anyway, if you really listen to your interviewees, you are likely to come up with a different index for each village, which messes up any kind of comparison anyway.

But we know from experiences like PAPI in Vietnam, and others in Uganda (as well as in lots of other settings from the UN to corporates) that a league table focuses the minds of leaders like nothing else – they really don’t want to be beaten by their neighbours and rivals. Anna replied to my question on this by saying ‘I’m an anthropologist, so instinctively cautious about quantification, and the distortion produced through overemphasis on proxy indicators’. Actually, there’s lots of quantification in the index, what she’s opposing is over-simplification, which is laudable, but could carry a cost in lost influence.

Has anyone done a comparative study of different approaches to local government indexes – how they are designed, who uses them, what impact they have etc? If so, I’d love to read it.

June 28, 2017

Digested read: 3 new papers on measuring women’s empowerment; gender and ISIS; women’s rights in the Middle East and North Africa

Just sampled a couple of hundred pages of Oxfam’s prodigious output on gender issues. 3 new papers, to be precise,  all of them ground-breaking in different ways. A ‘How To’ Guide to Measuring Women’s Empowerment; a Gender and Conflict Analysis in ISIS-affected communities in Iraq, and Gender Justice, Conflict and Fragility in the Middle East and North Africa.

all of them ground-breaking in different ways. A ‘How To’ Guide to Measuring Women’s Empowerment; a Gender and Conflict Analysis in ISIS-affected communities in Iraq, and Gender Justice, Conflict and Fragility in the Middle East and North Africa.

All of them ground-breaking, but none of them easy reads. The How To Guide is for the measurement geeks, setting out our best efforts to combine rigour and affordability (our MEL supremo reckons we can construct a pretty robust empowerment metric and measure it for about $20,000 a pop). I’ll leave the intro to one of the authors, Simone Lombardini, but I love the effort to construct an index based on the views of those being ‘measured’, combined with a thorough reading of the literature on ways to understand empowerment.

For the ISIS case study, the authors used a joint gender and conflict analysis to try and understand how gender roles evolved in communities in Iraq that were first occupied by ISIS and then fled to IDP camps. The aim is both to understand what happened, and identify points of entry for humanitarians trying to mitigate gendered forms of violence and tensions, and support ‘gendered drivers that contribute to stability and community cohesion’.

To be honest, I sometimes struggle with these papers, which seem to take a rather long time restating the obvious in very inaccessible language. But it’s worth persevering (especially when the authors know how to write a good executive summary) for those little insights and surprises. In this case:

‘From 2014 onwards, ISIS imposed a strict social control over communities in Iraq. In response to the disruption of the social fabric, the retraction of safe public space, the conflict-induced disintegration of household units and the regulation of marriages, household members increasingly withdrew to the domestic space, which resulted in increased household tensions.’

‘From 2014 onwards, ISIS imposed a strict social control over communities in Iraq. In response to the disruption of the social fabric, the retraction of safe public space, the conflict-induced disintegration of household units and the regulation of marriages, household members increasingly withdrew to the domestic space, which resulted in increased household tensions.’

Translation: People were too terrified to leave the home. Cooped up inside, they started to bicker and fight.

Under ISIS occupation, women ‘extended their scope of practices in the course of ISIS-occupation to interpret well-being of the family in terms of protecting their children from joining ISIS, keeping their families safe and stressing the importance of education in a context where the formal school system had been dismantled. The acknowledgement of women’s diverse roles in keeping their families safe and shifts in intra-household power dynamics, constitute a possible entry point to strengthen women’s participation in contexts of displacement, as they strive to resume paid work, report an increase in joint household expenditure decision-making within the household or expressing their interest in being more involved in community decision-making.’

Translation: An unexpected silver lining in terms of women’s rights. Under effective house arrest, women’s roles expanded to include keeping their kids safe and trying to keep them studying. In the IDP camps, women are now bouncing back, wanting more control over their lives and money. Outside agencies can work with that.

I found the paper on gender justice in MENA particularly interesting, but at 118 pages, not for the fainthearted. It covers Egypt, Iraq, the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) and Yemen. It charts how progress on women’s rights in the Arab Spring in Egypt and Yemen went into sharp reversal. In the words of one Yemeni activist:

“The moment that violence was used to reach power, that stopped everything. The use of violence gives the idea  that those who use their weapons will reach their goals. So we ended up with the … parties that use violence [being] the ones who are heard and included to make decisions. They are the ones that the international community engages with. As women are not part of this mechanism using violence, it means automatically that women are not heard and are not a part of the process.”

that those who use their weapons will reach their goals. So we ended up with the … parties that use violence [being] the ones who are heard and included to make decisions. They are the ones that the international community engages with. As women are not part of this mechanism using violence, it means automatically that women are not heard and are not a part of the process.”

The report has harsh words for the donors and international NGOs for imposing their priorities and processes on Women’s Rights Organizations that already have their backs against the wall:

‘Across all contexts, this reflects the larger phenomenon of “NGO-ization” that has overtaken the region. By reducing activism into distinct units of ‘projects’ of limited time and funding, donor and INGO models prove reductive to the indigenous forms of activism that are actually able to precipitate long-term positive change.’ Ouch

There is a nuanced account of people’s views on the links (positive and negative) between faith and women’s rights in the region. On the one hand, this from an OPT academic:

“The community has become superficially more conservative. There has been a change in the way that people dress – but this is not an indicator of content … There is a lot more support for women in higher education and a lot more women in higher education. There is also a greater demand for women to be in the workplace. There has been a revolution among young women over the past 10 to 15 years. There are more people attending the mosque and wearing niqab, but there is actually a lot more rights for women living in the West Bank.”

On the other hand, an Egyptian interviewee isn’t buying it:

“This is what we have been doing for years and years, and it shows no results. Show me something good that comes out of working with religious leaders. At the end of the day, they are conservative old men.”

Finally, a fascinating and subtle account of the Arab Spring and aftermath. Women in Cairo described the uprising as the moment in which the “barrier of fear” was broken – and the last two years of fear and insecurity have not returned their lives to the status quo ante. There is greater awareness around sexual harassment due to campaigns and the discursive opening post-revolution. Increased awareness and acceptability of speaking about harassment has empowered women and girls to report incidents to the police, something that was almost unheard of before. As one feminist activist said:

“After the revolution, we began to know each other. Before the revolution, there were many sexual assaults but women were silent about these and if we spoke about them, we were accused of being liars. After the revolution, women started to speak about this and the ugly face of Egypt came up.”

Would love to see more about the Arab Spring’s legacy in terms of women’s rights. Any recommendations?

June 27, 2017

What is really going on within ‘shrinking civil society space’ and how should international actors respond?

Good conversation (Chatham House Rule) last week on the global crackdown on civil society organizations (CSOs) and what to do about it. I was expecting a fairly standard ‘it’s all terrible; international NGOs must take action, speak truth to power etc’ discussion, but it was actually much more interesting and nuanced than that.

Good conversation (Chatham House Rule) last week on the global crackdown on civil society organizations (CSOs) and what to do about it. I was expecting a fairly standard ‘it’s all terrible; international NGOs must take action, speak truth to power etc’ discussion, but it was actually much more interesting and nuanced than that.

While it is undoubtedly true, and horrible, that governments around the world are squeezing the space for civic activism, sometimes violently, the detailed picture is actually quite complex. Some points on the diagnosis, and then the response.

To what extent is this part of a process of emerging regulation, as part of a broader process of formalization? If I compare what is happening now with the social and protest movements I saw in Latin America in the 80s, which often experienced the most appalling levels of repression, there is a sense that things have moved on. Much of the ‘crackdown’ is now through regulation, registration and financial rules, transparency etc. Some of it is undoubtedly malicious, but some is probably a necessary effort to introduce accountability and good governance into a new and expanding sector. Or are we saying that the state should not regulate CSOs?!

The squeeze is not taking place in a political or social vacuum. We need to understand how it connects with other trends, which shape how it is playing out: technology (the rise of social media), demographic (rising literacy, urbanization), new forms of politics (eg right wing populism) and of course, counter-terrorism and security.

Which bits of civil society are more or less vulnerable? Civil society extends far beyond the formal CSOs that are often the partners of aid organizations – are more informal organizations also suffering, or is it a particular form of CSO that is bearing the brunt? Have we, as I fear, contributed to the problem by insisting that in exchange for our aid dollars, local CSOs adopt our language, processes and upward accountability, making them appear less locally legitimate, and so more vulnerable?

What is expanding to fill the vacuum left by shrinking civil society space? As a recent International Budget Partnership paper showed, these may represent opportunities for new partnerships, and maybe to return to our wider role of solidarity with informal social movements, not just more institutionalised partnerships with southern NGOs. IBP found that litigation, Supreme Audit Institutions and municipal governments are playing a growing role. At the seminar, participants talked of religious leaders and private firms also becoming more engaged – who else?

From Civicus

Behind all this there was an underlying anxiety that framing all this as the ‘global civil society crackdown’ could be somehow overly Western. I have yet to see a comprehensive ‘Voices of the Poor’ type piece of research that asks different forms of civil society (including CSOs but also grassroots organizations, sports club supporters, cultural groups, faith organizations) how they see the current threats and opportunities, but one participant described the feedback his organization received as ‘you frame this too negatively – there are huge opportunities in disruption as well as negatives’.

As for how to respond:

Big focus on the limitations of global narratives. Problems and solutions are deeply local, with INGOs and other outsiders having only a limited role (and having to be careful about their actions making matters worse – eg by highlighting the aid dependence of their local partners). Outsiders need to make it a priority to canvass the opinions of and be led by local civil society organizations, and be cautious about launching into generic global campaigns.

At national level, the challenge in some places is to rebuild the legitimacy of civic action, which has been damaged by excessive dependence on aid. There’s a clear place for working on longer term attitudes, beliefs, norms etc there. How have Indian NGOs responded to the crackdown by the Modi government? Have they tried a big picture normative campaign about the role of civic action in India’s history (‘Gandhi was an activist’) and if so, how did it go?

As for outsiders, like INGOs, there seem to be at least three kinds of possible strategy:

Research: ICNL and Civicus are doing good monitoring work on the extent of the legal and policy crackdown, but the IBP study I reviewed earlier is one of the few examples of taking a ‘positive deviance’ approach, trying to spot new forms of organization and activism that are emerging into the vacuum and/or proving more resilient.

I’m not sure how useful global problem analysis is, given the complexity and national specificity of the interlocking political economies of aid organizations  and national polities; a series of national case studies might be more use, both of endogenous change processes of crackdown, resistance or emergence, but also of how outsiders have tried to influence events.

and national polities; a series of national case studies might be more use, both of endogenous change processes of crackdown, resistance or emergence, but also of how outsiders have tried to influence events.

Influencing: at both global and (if we are invited) national level , this would include the standard elements of advocacy

Stakeholder and power analysis of both donors and national polities

Identify the right messengers to carry the message about civil society to those in power

The right coalitions (including unusual suspects)

Defensive tactics (eg opposing bad new laws)

Offensive tactics, whether to help existing organizations adapt to new rules, identify and work with new actors, or concentrate on building broader coalitions of civil society.

The right stories: myths and iconic success stories (lots of them)

Readiness to seize windows of opportunity presented by scandals, shocks, changes of leadership etc

Programming:

Building domestic resilience, eg by helping local organizations raise money locally to wean them off aid dependence.

Support increased diversity and linking eg via peer to peer networks, including both partners and INGOs/externals on how to work in these reduced/changing spaces

Rethink some partnerships to focus on the more durable/resilient elements of civil society, and those emerging into the new contexts

Dignified exit (INGOs can step away and promote localization at the same time)

Rethink the kinds of funding that work best in this new context eg core funding or scholarships may be better attuned than traditional project funding

For more background, Civicus has just published its ‘State of Civil Society‘ report for 2017. Here is an Oxfam paper on challenging shrinking civic space in Africa and articles by my Oxfam colleagues on trends in shrinking civic space, social exclusion and civic space and innovative approaches towards protecting civic space

Thoughts?

June 26, 2017

On hype, Impact Investing and the Valley of Death

How do we build bridges across the Valley of Death? That’s the arresting image in a recent Oxfam paper on ‘impact investing’. The valley of death (see diagram) is the gap that firms face as they move from small start ups to Big Biz. In the start-up stage they raise cash wherever they can find it – family, friends, microfinance. Once they are big enough, they have stock markets and banks queuing up to lend them cash. But in the middle there’s a big hole, also known (not surprisingly) as the ‘Missing Middle’.

‘Impact Investing’ is one effort to fill the gap. II means investing with a double motive: to make some money, and simultaneously to do some good, including previous excluded groups in the benefits of the market etc.

‘Impact Investing’ is one effort to fill the gap. II means investing with a double motive: to make some money, and simultaneously to do some good, including previous excluded groups in the benefits of the market etc.

But ‘Impact Investing: Who Are We Serving?’ finds there are some serious problems with the model. The first is that the massive hype from product salesmen and government officials desperately seeking ‘private sector solutions’ gets in the way of sober scrutiny – we don’t actually have much solid evidence on the impact of impact investing, whether good or bad.

The paper also argues that II is following the same cycle of mission decay that critics see in the rise and fall of microfinance, as initial pioneers willing to take a low level of profit in return for social impact are elbowed aside by new entrants and spin doctors claiming you can have your cake and eat it:

‘Impact investment arose out of a desire by investors to preserve capital while making positive impact. In doing so, it was able to reach enterprises and have impacts that financial markets were not able to serve. Newer entrants are instead chasing higher returns while hoping to preserve impact. This paper argues that this risks discrediting the sector through generating unrealistic expectations about financial returns from impact investments.’

was able to reach enterprises and have impacts that financial markets were not able to serve. Newer entrants are instead chasing higher returns while hoping to preserve impact. This paper argues that this risks discrediting the sector through generating unrealistic expectations about financial returns from impact investments.’

Here’s a nice example of genuine II:

‘Take the example of cooperative Kawa Maber, located in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where infrastructure, whether in the form of Internet or functioning roads, ranges from poor to nonexistent. Extortion is a constant challenge, and the threat of ethnic and political violence or a catastrophic weather event is ever-present. The business does not even have a formal address. Despite these challenges, Root Capital underwrote a loan to Kawa Maber. Where formerly these farmers were forced to sell their coffee at cut-rate prices to middlemen in the region, as a cooperative with ties to European buyers farmers now benefit from bargaining power that comes with selling at scale. An investment in Kawa Maber could not be supported by a fund targeting market-rate returns. Yet, Kawa Maber is revenue generating and creates abundant impact. Without the creativity of Root Capital and the investors and donors that support it, Kawa Maber would likely fall into the ‘valley of death’.’

How to distinguish real II from hype? The paper argues that the key lies in ‘intentionality’ – ‘not every business that has an impact is an impact investment, as the intention to do good does not drive the business’. Without intention, there is unlikely to be serious scrutiny over whether, for example, a new mobile phone mast actually helps poor and excluded families or displaces them. Instead, all such concerns are washed away in a tide of feelgood hype.

The paper ends with some sensible recommendations for would-be impact investors:

The paper ends with some sensible recommendations for would-be impact investors:

A shift of approach in the market is needed; from one wherein we tailor funds around the needs of investors to instead developing products that serve the needs of enterprises seeking to combat poverty. Specifically, new financial tools that reflect the predominantly ‘low and slow-returns’ of most enterprises prioritizing social impact;

Greater transparency is needed around reporting both the impact and financial returns (gross and net) achieved by impact investors;

Donors and philanthropists need to deploy smart subsidy and patient capital to support enterprises capable of making a meaningful contribution to poverty reduction, and to support hybrid financing models alongside impact investors seeking a net return on capital;

More independent research is needed to understand the enterprise-level experience and analyze which structures, approaches, and incentives best assist enterprises to maintain an intentionality to optimize impact;

We call on impact investors to agree to a voluntary code of practice that enshrines the intentionality to behave and take decisions in ways that have a primary focus on achieving impact;

Impact investors should adopt incentives for optimizing, measuring, and reporting impact as well as achieving financial return targets.

I’ve long been instinctively sceptical of the overselling of impact investing and other private sector magic bullets, so it’s great to have my prejudices confirmed ;-). My only quibble on all this eminently sensible stuff is ‘where’s the link to market systems approaches’? The II model seems very linear – shove money into a product or service in such a way that it benefits poor people. But does that mean it completely ignores the wider issues (eg gender discrimination) that stop people benefiting from markets in the first place?

June 25, 2017

Links I Liked

When people talk about ‘systems change‘ they mean 3 different things. Useful unpacking from Dan Vexler

She teaches karate to boys and can extract the DNA from bananas. How to be a 5-Year-Old Feminist, aka Eva rocks (but why won’t Channel 4 let us embed it from youtube?)

Being in power causes a particular kind of brain damage. Makes sense.

Girls of 11 forced to marry when pregnant ‘to hide rapes by church elders’. Horrific stories of early marriage in ….. the US, h/t Katrin Bennhold. But at least New York just raised the age of consent to 18.

Check out voxdev.org, a new blog ‘to put evidence from decades of academic research into the hands of decision-makers.’ Good Luck With That.

Zakat requires Muslims to donate 2.5% of their wealth every year (up to $1 trillion in 2015): could this end poverty/ finance the SDGs?

Zakat requires Muslims to donate 2.5% of their wealth every year (up to $1 trillion in 2015): could this end poverty/ finance the SDGs?

Thanks D Har for forwarding this handy Family Guy colour chart for hard-pressed journalists and headline writers everywhere (but don’t think that’s how you spell ‘mentally’, even in the US).

Torture, truth, forgiveness & hope. Speaking up is fighting back. Inspiring testimony from my Oxfam colleague Lan Mercado

June 22, 2017

Ditching the Masterplan. How can Urban Development become ‘Politically smart, locally led’?

Guest post from Harry Jones and Bishnu Adhikari, both of Palladium on what urban aid and

Guest post from Harry Jones and Bishnu Adhikari, both of Palladium on what urban aid and development can learn from the Doing Development Differently movement

development can learn from the Doing Development Differently movement

The international development community has come some way in grappling with complex problems, but urban development has lagged behind. Urban programmes systematically underperform according to their own results frameworks and internal evaluations. The failures are probably already familiar to those of us who spend time in cities around the world. Masterplans are not implemented and haphazard development continues. Metropolitan authorities and municipalities fail to deliver the functions they have on paper, and services remain dysfunctional. Infrastructure is built and money spent, but in a few years it degrades badly.

Over the last 5 years, we have tried to talk about this with ‘urban people’ in Nepal, Tanzania, Bangladesh, and elsewhere, but most of the time we get nowhere. Urban planners happily set about their next assignment and multilaterals eagerly mobilise further loans and grants. Bilaterals are now ramping up their investments in cities – for example DFID spent about £500m on urban-specific programmes in the past 10 years, and seems set to spend close to that amount again in the next 5.

If we wait for the next batch of programmes to fail in the same way as the last, we will see hundreds of millions of taxpayer’s money wasted. This is tough work, and there aren’t any easy answers, but it a richer and more open debate would at least be a start. In that spirit, this blog highlights the common lessons from past programmes, and shares the ideas on how to Do Urban Development Differently that we are currently piloting in a programme in Nepal.

What are the lessons from urban development failures?

Urban development in developing countries typically involves: establishing or engaging with an institution with responsibility across constituencies and services; developing master plans based on extensive analysis and consultation; securing resources, and then overseeing implementation. Donor programmes typically support this through technical assistance (TA) for planning and institutional design, capital investments, and capacity building for municipalities. Where and why does this fall down?

Firstly, this approach is not adaptive enough. While uncertainty and unpredictability means we should be taking a number of ‘small bets’ and learning by doing, the traditional approach does the exact opposite. Ambitious and comprehensive plans are produced, fixing the details of an intervention in advance in order to secure large loans. Intervening in some of the most complex and dynamic human ecosystems on the planet without sufficient flexibility means that unforeseen constraints cannot be overcome, and unexpected opportunities are missed.

Secondly, the approach is overly technocratic. Academic research and programming experience from around the world show beyond doubt that political economy factors are just as important for urban service delivery as technical design and levels of resourcing. But while project evaluations are happy to blame failures after the fact on context or politics, these factors are not taken seriously in programme design. Thus traditional approaches typically fail because local level institutions are fragmented, or because the capacity to implement and enforce is constrained by informal practices. Planning processes have low credibility, and consultation is tokenistic, bypassing elected representatives, and benefits are narrowly captured. Donor support can exacerbate this, creating perverse incentives with large amounts of ‘free money’ delivered top-down.

Secondly, the approach is overly technocratic. Academic research and programming experience from around the world show beyond doubt that political economy factors are just as important for urban service delivery as technical design and levels of resourcing. But while project evaluations are happy to blame failures after the fact on context or politics, these factors are not taken seriously in programme design. Thus traditional approaches typically fail because local level institutions are fragmented, or because the capacity to implement and enforce is constrained by informal practices. Planning processes have low credibility, and consultation is tokenistic, bypassing elected representatives, and benefits are narrowly captured. Donor support can exacerbate this, creating perverse incentives with large amounts of ‘free money’ delivered top-down.

What could a different approach look like?

So far, so depressing. But there is the potential for different and better programming. For example, a small project in Pokhara, Nepal explored models that could catalyse collaboration between the public and private sectors for urban development. Of three initiatives launched, one failed miserably, one spectacularly, but one of them succeeded – developing a Public Private Partnership (PPP) model for installing solar street lights. Those lights, locally funded, were the first of their kind in the country, and had a strong demonstration effect. The model was picked up by government, which now provides a large annual subsidy; 2 years on there are 50,000 under installation in 150 municipalities, using the same guidelines. The project thus leveraged around 100 times its own value in Nepali investment in urban infrastructure.

Now, under a UK government-funded programme implemented by Palladium, we are drawing on that experience to try and do things differently at scale. On the Economic Policy Incubator, we are working in an economic corridor in the West of Nepal, piloting a new approach to strengthening economic development.

Brokering agreement and action between key stakeholders. Lack of money is rarely the problem in cities. In our corridor there is a stable and growing tourism sector centred around Pokhara and Lumbini, and the Southern end includes key locations for the country’s manufacturing, industry, and trade with India. Many of the cities also have a history of political and social activism. Bringing different actors together to solve coordination and collective action problems can unlock the resources that are already there:

We have city coordinators who liaise with local stakeholders, including business associations and municipalities. They are recruited from and based in the local area, selected for their existing local networks and perceived neutrality

We are preparing to support local mayors – there is great anticipation, these guys will be Nepal’s first elected local representatives for 20yrs

We have been informally engaging with MPs and other influential figures in each location, and we do ‘live’ political economy analyses of key towns and cities

We are stealing SAVI’s idea to support local dialogue through radio call-in shows – to understand local problems and perspectives, and support constructive discussion

Learning by Doing: If we do all the analysis before the local engagement, we could end up with something that looks ideal on paper, but which is impossible in practice. So instead, analysis of economic priorities for the cities and corridor goes on alongside launching local actions. We have been looking for common problems that hurt business growth as well as affecting the lives of local residents, and are working on a number of ‘quick wins’ with local stakeholders (see the table below for examples).

These will deliver important benefits, but they’re also a means to an end. Some of our initiatives will succeed and some will fail, and along the way we learn important lessons about how to promote action in different locations. This iterative process allows us to make many small bets, so that we can later place larger bets on the basis of demonstrated feasibility. In a culture where direct disagreement is rare, it’s often only when the rubber hits the road that you learn where the real interest and ownership are. And successful local initiatives may also unearth new models that can be taken up elsewhere (as with the street lights).

These will deliver important benefits, but they’re also a means to an end. Some of our initiatives will succeed and some will fail, and along the way we learn important lessons about how to promote action in different locations. This iterative process allows us to make many small bets, so that we can later place larger bets on the basis of demonstrated feasibility. In a culture where direct disagreement is rare, it’s often only when the rubber hits the road that you learn where the real interest and ownership are. And successful local initiatives may also unearth new models that can be taken up elsewhere (as with the street lights).

Supporting the emergence of local leadership and coordination capacity. The identification, planning, and management of initiatives is driven by local stakeholders, with their own budgets. They must be prepared to invest their own resources or able to persuade others to do so – supporting the emergence of collaboration and coalitions that can drive local development. Doing this iteratively helps us find leaders with sufficient will and coordinating power, and identify issues that can mobilise sufficient traction across different constituencies.

‘Quick wins’ also build effective local leadership. Small victories build momentum behind local leaders and issues, strengthens working relationships (countering fragmentation), and builds credibility. In Pokhara we are already building on the street lights success, with local stakeholders more willing to invest in collaboration, and if local efforts can bring improved electricity supply for manufacturing in Bhairahawa, this may spur further interest.

Combined, this approach can be seen as an alternative to the ‘traditional’ playbook, an incremental approach to urban development (diagram below), building ambition and scope as political/institutional foundations are strengthened.

Who else, and where next?

Others are also trying things differently – for example TAF has been working with politically smart approaches in cities in Bangladesh, Cambodia and Mongolia. Developed nations also face similar challenges, for example the institution building lessons passed on by the Centre for Cities for the new metro mayors in the UK.

We’re not claiming to have ‘the answer’ here. Mirroring the current status of the DDD debate, there isn’t yet robust evidence about the impact of new models, because they have yet to be consistently tried. What we do have is strong evidence that taking a traditional approach will have serious failings, and we have some clear principles for alternative approaches. We’re keen to talk to others who can share their ideas and experiences, so please get in touch.

For further info, contact harry.jones@thepalladiumgroup.com or bishnu.adhikari@thepalladiumgroup.com

June 21, 2017

Loneliness, Love, Anger and Activism

Spent a morning at the Ashridge Business School Masters in Sustainability and Responsibility last week. The School

Hogwarts Business School

is extraordinary – a Hogwarts-esque stately home full of statues and vaulted ceilings, formerly Henry VIII’s crib, set in a country park dotted with croquet lawns and mighty oaks. The conversation was also pretty good – 15 Masters students from every continent/walk of life. Only a couple of aid types – there were people from banking, oil and lots of other sectors there, and what struck me was how much the conversation focussed on psychology and emotion, which are often barely mentioned in aid industry discussions dominated by plain vanilla exchanges of stats and policy recommendations that often ignore the emotions in the room. It got a bit bean baggy at times, but I think there was something important there too. Impressions:

The loneliness of the long distance change-maker: working in an NGO, you take for granted that your colleagues will care about issues like rights and justice. The world outside can be very different and several speakers spoke of their loneliness in swimming against the tide on issues like sustainability or fossil fuel investment. One ex-lawyer talked of ‘the persona you have to assume between prêt a manger and the office door’. Here’s a banker-turned-Oxfamer recalling his past alienation. Building supportive networks has played a huge personal role in enabling them to keep going. Reminded me a bit of the Cambodian pink phones project (see video) – can/should NGOs do more to help build up these supportive communities of practice within the private sector or the state?

CEO as critical juncture: I’d forgotten what a big moment in a firm’s life is produced by a change of CEO. These are trigger points when policies and practices can change, as when Paul Polman’s first act on taking over at Unilever was to abandon quarterly reporting to try and free the firm from short term investor pressures. Could activists (both inside and outside a company) trying to influence corporates more consciously plan and respond to changes at the top as windows of opportunity?

Candidate for best initial question after a presentation of How Change Happens: ‘do you lie a lot?’ To which my answer has to be ‘depends what you mean by lying’. There’s lots of varieties of, (how shall I put it?) constructive ambiguity and selective truthiness, but in my defence, some of them come down to building bridges not walls:

Correction of power imbalances: I may think that my ideas/Oxfam are great, but if I’m the one doing the speaking, there’s already a power imbalance in the room, and bigging myself/my organization up will only make it worse. So ‘tactical self-deprecation’, focussing on the flaws, whether personal or institutional, makes sense (and to be fair, there’s plenty of both)

Accentuating common ground, rather than speaking truth to power. It’s easy to ‘other’ people from other institutions – bankers, oil reps, officials. You may have profound disagreements with what they do for a living, and saying so can be cathartic, but turning people into ‘targets’ and wagging your finger at them doesn’t constitute much of an influencing strategy. Often more effective to put your scruples to one side and try and empathise with the person in front of you.

But there are also plenty of bad reasons for lying, in my book. Keeping things ridiculously simple (presumably

Beanbag-tastic

because you think your listeners/readers are stupid); or recycling ‘political facts’ because you like their message, even though you know they are either incorrect or unprovable (‘70% of the world’s poor are women’ anyone?) Those kinds of manipulation are born of intellectual laziness, and are likely to come back to haunt us at some point.

Perhaps most insidious of all are the lies you aren’t even aware of. When you filter the world through your preconceptions, see/hear what you expect to see/hear, miss new ideas or possibilities, keep churning out the same old stuff. Contrarianism helps – if I hear the same thing too often, or too uncritically stated, then I instinctively start looking for the flaws or alternatives. But contrarianism is also a kind of lie. Aagh, turtles all the way down.

But what about anger? Anger motivates a lot of activists – rage at injustice, the state of the world, or how personal mistreatment. Authenticity, as we have seen in recent elections, is a huge plus in politics, so should activists get out there and vent? Or should you hide the anger in order to try and build the bridges with people with whom you deeply disagree? One Indian student, who lives in Europe, complained that ‘in Denmark no-one shows their anger. But showing it allows us to let go of the negativity inside us- it frees us’. She added a useful insight: ‘it depends on who is wagging the finger or clenching the fist’ – it’s one thing for the poor and excluded to express their anger, but perhaps another for middle class activists to do so on their behalf. One (fairly angry) environmentalist conceded that it was necessary to retake ‘control of the anger knob’ and know how to mix anger and love.

As I say, not the usual aid conversation.

June 20, 2017

Can Oxfam do the Doughnut? A conversation with Kate Raworth

Kate Raworth came in last week to present her new book, Doughnut Economics (see my earlier review here or Simon Maxwell’s thoughtful summary/critique) and discuss its implications for Oxfam. After writing the initial DE paper while still at Oxfam back in 2012, Kate left to turn it into a book, so there was a definite air of the prodigal daughter returns.

Maxwell’s thoughtful summary/critique) and discuss its implications for Oxfam. After writing the initial DE paper while still at Oxfam back in 2012, Kate left to turn it into a book, so there was a definite air of the prodigal daughter returns.

Given that I’ve already reviewed the book, I’ll concentrate on a few of the highlights from a wide-ranging brainstorm on its implications for Oxfam. Although we have done quite a bit already – see our Human Economy paper for Davos, the Humankind Index and efforts to take the doughnut to national level in Wales, Scotland and South Africa – Kate’s book goes deep into a broad critique of traditional economics, and the discussion followed suit:

How do you work on the Commons? Kate argues that we need to get away from the 20th Century state v market Punch and Judy show and think about the Commons, a la Elinor Ostrom. I think I get what she’s on about, but would like to talk and think further about how an INGO ‘does’ the Commons. There’s clearly a role for shifting norms, whether by celebrating resources held in common (land, ideas, knowledge, maybe even wisdom and solidarity), pushing for new kinds of commons like Open Access (are you listening ODI?) and opposing their further enclosure or destruction.

I suspect there’s also an element of rediscovery – while Oxfam HQ (especially in advocacy) may frame things in terms of states v markets (and how campaigners influence both), a lot of our field staff and partners are already there on the central importance of the Commons on issues like access to land. But what else?

The What v The How: Kate’s book is unabashedly a Big Vision book. She sets out a bright, convincing and fundamentally optimistic view of how the world could/should be. In my review I asked ‘where’s the theory of change?’ and lots of the questions at Oxfam were about how can you get from a → b, who were the drivers and blockers of change, what to do about financial capital etc etc. Kate’s response was very honest: ‘books that set out the big vision don’t usually tell you how to get there’, because the ‘how’ and the ‘what’ tend to attract different minds. I realized that I’m definitely a How person (see Brian Levy’s review of How Change Happens), and I really would like to see a theory of change/action for how DE might actually come about, but that’s not the job of Kate or her book. Fair enough.

As far as a theory of change goes, Kate is a natural friend of positive deviance – she identifies legions of exciting outlier experiments in new economics that illustrate her big themes and her book seems to be inspiring further experimentation popping up in local councils and other places. Another approach would be deliberate seeding – Oxfam spends some money funding a bunch of DE-based experiments and sees what works. The least attractive action (Kate is big on systems thinking) would be traditional and linear – we decide on the best project in advance, then fund it.

As far as a theory of change goes, Kate is a natural friend of positive deviance – she identifies legions of exciting outlier experiments in new economics that illustrate her big themes and her book seems to be inspiring further experimentation popping up in local councils and other places. Another approach would be deliberate seeding – Oxfam spends some money funding a bunch of DE-based experiments and sees what works. The least attractive action (Kate is big on systems thinking) would be traditional and linear – we decide on the best project in advance, then fund it.

The Dark Side: Asked what of the many conversations had caused her to go back and question herself, Kate said it

But what about optimism of the intellect?

was the dark side. What if instead of the 21st century question being ‘how do we get into the doughnut’, the 21st century reality is now inevitably outside of the doughnut: what then is the fate/aim for humanity? I would add to that her instinctive preference for a single human ‘we’ – not in the sense that people are all the same, but in the assumption that humanity wants to find collective solutions to problems. What if there is no ‘we’, and millions of people are condemned to be sacrificed to an unsustainable economic model? How should progressives respond to that nastier reality? Clear parallels with David Kennedy’s critique of How Change Happens there.

Then there’s Kate herself and the whole question of ‘thought leadership’. What if she hadn’t left Oxfam? Would she have ever written the book or got her thinking as far as it is today? Interesting to compare our two trajectories. I stayed at Oxfam, she left. We both wrote books, but had to raise funding to enable us to do so – me from the Aussie Government, Kate from the Kendeda Fund. Should/could Oxfam be more deliberate about this, trying to spot and back future Kates either in our staff or our networks? Perhaps play the same role as the Kendeda Fund and support them for a year or two to capture the big idea, a bit like the MacArthur Genius Grant? Where would we find the money for such an effort?

Finally, when it comes to communications, is Oxfam big C or little c? Little c runs something like ‘write your paper, then roll out the comms – exec sum, infographics, maybe a youtube video’. Kate is an example of a different, big C, approach. Spend time (quite possibly a lot of it) shaping the narrative of your Big Idea – get the diagram or the strapline right, then test it and improve if necessary. Only when you’ve nailed that do you work outwards from the big idea, whether to text, visuals, video or whatever. Maybe we should change the way we generate ideas and materials to more consciously pursue Big C Comms.

Great stuff, and thanks to all the colleagues whose ideas and questions I have nicked for this post. Kate is going to keep helping us think through this stuff – can’t wait.

June 19, 2017

Grenfell Tower is a Hurricane Katrina moment, revealing the shameful state of Britain

My colleague

Max Lawson

sends out a weekly round-up of things he’s read, and adds some views. Here he is on the meaning and horror of the Grenfell Tower fire.

meaning and horror of the Grenfell Tower fire.

At times an event can act like a flash of lightning, illuminating simmering issues that can otherwise feel abstract. The recent horrific fire in the Grenfell Tower Block in West London has done this in the UK, not unlike Hurricane Katrina in the United States. It has shown in stark relief the state of the country that Britain has become.

As recently as 1979, 42% of British people lived in government housing. Safe, decent public housing was a fundamental part of the welfare state, accepted by all political parties. For many residents, these houses were wonderful compared to the slum conditions in which they had been living for generations, and a much higher standard than private alternatives. This changed rapidly from the early 1980’s. The government of Mrs Thatcher sold off many council houses, and virtually no new public housing has been built since that time by either Labour or Conservative governments. Today only 8% of the UK public live in this housing, and they are overwhelmingly from the poorest and must deprived sections of society. And the poorest and most disenfranchised among this group are forced to live in high rise towers. The inequality is spatial, economic and racial too. Danny Dorling has shown that the majority of black children in London and Birmingham live above the fourth floor. Is it any surprise that Unicef this week reported that among rich nations the UK has some of the highest levels of child hunger and deprivation?

The Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, where the Grenfell Tower stands, is a poster child for inequality in one of the most unequal cities in the world. It contains some of the most expensive property on earth, including the £150 million mansion of Chelsea football club owner Roman Abramovich. Many of these huge houses lie empty, bought as investments. It also contains some of the poorest communities in London, and indeed in the UK. On one estate over 58% live in poverty, and this situation has been getting steadily worse.

The Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, where the Grenfell Tower stands, is a poster child for inequality in one of the most unequal cities in the world. It contains some of the most expensive property on earth, including the £150 million mansion of Chelsea football club owner Roman Abramovich. Many of these huge houses lie empty, bought as investments. It also contains some of the poorest communities in London, and indeed in the UK. On one estate over 58% live in poverty, and this situation has been getting steadily worse.

London differs from many major cities, in that even in the richest parts of the city, there are still substantial amounts of housing for poor people. Following the war, when there was a socialist government in the UK and significant bomb damage across the country, public housing was built on much of the vacant land. This is true in Kensington and Chelsea. I lived in a council estate very near there for a number of years, and it is an incredible community. A mish-mash of nationalities, faiths, ethnicities and histories. It is the location of the Notting Hill Carnival. It is the birthplace of one of the greatest bands in UK history, the Clash, whose guitarist Mick Jones grew up in a council tower block. Yet across the city, recent governments have promoted the selling off and demolition of this housing, with the poorest having to move out to the suburbs and beyond, in what has been described as social cleansing that is forcing tens of thousands out of London.

Following closely on our dramatic election, the Grenfell Tower fire has acted as a prism to focus a series of issues central to inequality. Firstly deregulation. Inadequate and outdated fire regulations have clearly played a part here. As one commentator put it, ‘A favourite slogan of the right was the promise of “a bonfire of regulations”. Well, they got their bonfire all right.’ Secondly privatisation. Public housing has been transferred to private management and ownership across the UK. Rather than an elected council, residents are left to deal with unresponsive, unaccountable companies, driven often by profit to cut as many corners as possible. Like the management company for the Grenfell tower that are reported to have saved £5,000 from a multi-million pound refurbishment by using external cladding that was cheaper and more flammable. Thirdly austerity, which has seen the budgets of local government cut dramatically with the greatest cuts felt by the poorest areas.

And overwhelmingly this is a story of inequality itself. This is not just about economic inequality, but inequality  of voice, of power. It is about inequality of fear and risk too. Across the world, as Oxfam has shown in relation to natural disasters, risk is redistributed downwards, onto the shoulders of those who are least able to cope. Accidents and fires like this happen across the world on a regular basis. Just this week a seven story building occupied by low-income families collapsed in Nairobi. The poorest and most vulnerable are almost always the hardest hit.

of voice, of power. It is about inequality of fear and risk too. Across the world, as Oxfam has shown in relation to natural disasters, risk is redistributed downwards, onto the shoulders of those who are least able to cope. Accidents and fires like this happen across the world on a regular basis. Just this week a seven story building occupied by low-income families collapsed in Nairobi. The poorest and most vulnerable are almost always the hardest hit.

The anger here in London is palpable. People are furious that such a thing could happen in one of the richest cities in the world. I hope something good can come of this. But one thing is for sure – it will come too late for the poor women, men and young children that died in that fire – their faces will haunt me for a long time to come, and I know I am not alone in that.

It is easy to get lost in the economic arguments about the importance or otherwise of inequality, and whether or not extreme wealth is beneficial or detrimental to our economies. These are of course important arguments to have, and to win if we are to convince policy makers to tackle extreme inequality. But sometimes it is good to take a step back and look at these things from a different perspective. I found this article in Current Affairs refreshing in this regard, as it chooses to look at extreme wealth instead from a moral perspective. It makes the straightforward assertion that ‘in a world of poverty, if you possess billions of dollars, in a world where many people struggle because they do not have much money, you are an immoral person. The same is true if you possess hundreds of millions of dollars, or even millions of dollars. Being extremely wealthy is impossible to justify in a world containing deprivation.’

Oxfam was originally founded by in part by Quakers, a left-leaning religious group in the UK, and I have no doubt many of our founders would have sympathy with this moral perspective. Whilst perhaps a little too strident for some tastes, it is hard to escape the unassailable moral logic of this basic argument, which predates capitalism.

One of the concerns about modern neoliberal capitalism, highlighted by Harvard Philosopher Michael Sandel in his brilliant book What Money Can’t Buy – the Moral Limits of Markets’, is that these basic moral questions are increasingly left to one side in favour of market forces. He argues that our civic life is simply too morally important for that. Yet all too often we leave our morality at the door, in favour of supposedly more hard headed, rational considerations. But does that really work, or is it simply cutting us off unnaturally from some of the most important considerations of all? We may not believe that the extremely rich should be forced to give all their money away, but I think the majority would agree that there are moral limits to the levels of wealth that can be accumulated by individuals in society and that we breached these limits a long time ago. And there are moral limits to inequality too. It is not just economically unacceptable that in a country of great wealth there is not enough money to ensure sprinklers and fire protection in every tall building. It is morally wrong too. It is morally wrong that extreme poverty can continue in a world of extreme wealth.

One of the concerns about modern neoliberal capitalism, highlighted by Harvard Philosopher Michael Sandel in his brilliant book What Money Can’t Buy – the Moral Limits of Markets’, is that these basic moral questions are increasingly left to one side in favour of market forces. He argues that our civic life is simply too morally important for that. Yet all too often we leave our morality at the door, in favour of supposedly more hard headed, rational considerations. But does that really work, or is it simply cutting us off unnaturally from some of the most important considerations of all? We may not believe that the extremely rich should be forced to give all their money away, but I think the majority would agree that there are moral limits to the levels of wealth that can be accumulated by individuals in society and that we breached these limits a long time ago. And there are moral limits to inequality too. It is not just economically unacceptable that in a country of great wealth there is not enough money to ensure sprinklers and fire protection in every tall building. It is morally wrong too. It is morally wrong that extreme poverty can continue in a world of extreme wealth.

And here’s an extraordinarily prescient 1993 clip from the original House of Cards

June 18, 2017

Links I Liked

We’ve resurrected FP2P on Facebook! Please like the page, circulate, comment etc and tell us if it’s not working

Did the world just hit peak booze? By volume, but not by alcohol content (people going off beer), so maybe just peak bladder

Reasons to be Cheerful. Percentage of women in national parliaments 1990 vs 2016

‘With a flipchart, pens & cheap ribbon from the pound shop we saw a transformation’. Lovely reflections from Laura Hughston on community feedback in programme monitoring and evaluation (h/t Samia Khatun)

Need to compile evidence on men hogging airtime in meetings (or want something to do while we’re droning on)? Click on arementalkingtoomuch.com

Need to compile evidence on men hogging airtime in meetings (or want something to do while we’re droning on)? Click on arementalkingtoomuch.com

A random but enjoyable list of the 101 most influential tweets – I only understand about half of them, but at least Ed Balls came top

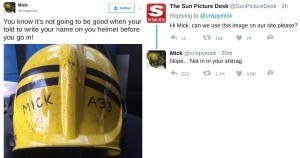

More sombre issues – brilliant Guardian editorial on the awful Grenfell Tower fire: Theresa May’s Hurricane Katrina and a firefighter took time out to comment on tabloid journalism (click to expand).

Two cheers as Canada launches first explicitly feminist aid policy (target of 80-95% of all its aid by 2022), but fails to  increase its overall spend.

increase its overall spend.

Loved this ad for the Van Gogh Museum. Look again if you missed it….

Great cartoon strip on the mental load in the care economy. Ouch. h/t Nikki van der Gaag

The weekend saw hundreds of thousands of events in the ‘Great Get Together’ celebrating the life and ideas of my former Oxfam colleague Jo Cox. This was one of my favourite results:

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers