Duncan Green's Blog, page 111

September 14, 2017

Can the UK become a Human Economy?

Rising inequality is a global problem. Oxfam inequality guru Deborah Hardoon appraises a new  report on its manifestations in the UK.

report on its manifestations in the UK.

Last week the IPPR, a progressive policy think tank, published a new report, ‘A time for change: A new vision for the British Economy’, which argues that “the economy we have today is creating neither prosperity nor justice. This is not inevitable, but the consequence of decisions made in recent decades…we can choose to change it, if we have the ambition and determination to do so”.

The commission responsible for this report includes representatives from business, civil society, trade unions, academia and the Archbishop of Canterbury and the report got some good media coverage as a result. At 122 pages and with loads of charts, it’s a great summary of all the major economic trends in the UK. A few snippets to whet your appetite:

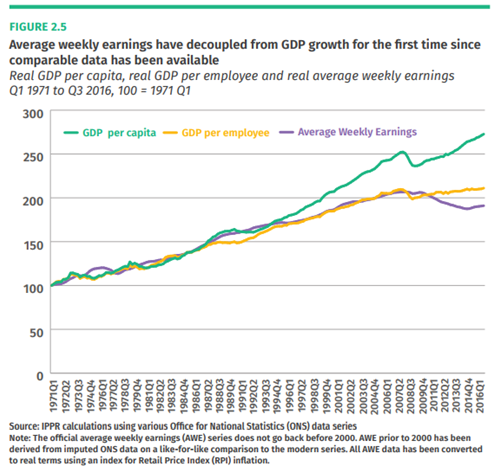

Since the global financial crisis, economic growth as measured by a sustained increase in GDP per capita is no longer associated with an increase in wages, with real weekly earning still well below pre crisis levels. (see figure below).

Almost a million people in the UK were working on zero hours contracts in 2016

The report shows that UK productivity (output per worker) has stalled, and is one of the lowest compared with other advanced economies, but not for all firms, the difference between the most productive and least productive firms is the highest of the sample countries.

I think this report makes a good contribution. It summarises a bunch of economic trends and uses this evidence to show not just that the economy needs to work better than it currently does for the majority of people, vulnerable people in particular, but also that because so many indicators are showing such ominous trends, there is a powerful case for a radical re-visioning of our whole economy and its policies, not just policy ‘whac a mole’.

I think this report makes a good contribution. It summarises a bunch of economic trends and uses this evidence to show not just that the economy needs to work better than it currently does for the majority of people, vulnerable people in particular, but also that because so many indicators are showing such ominous trends, there is a powerful case for a radical re-visioning of our whole economy and its policies, not just policy ‘whac a mole’.

It’s an interim report and the idea is that the debate it generates will shape the proposals for the way forward which are due in a report out next year. So with that in mind, I wanted to appreciate the work so far, but also flag three important blind spots from the report that really should be central to the vision going forwards.

The rest of the world matters too. The report presents UK data alongside, or ‘versus’ other advanced economies and talks about the UK’s competitiveness for exports and investment. But the vision for the UK must also appreciate the importance of rights, economic justice and safety and security for people in other countries and those people moving between them. The UK exporting arms to Saudi Arabia for example doesn’t just affect the UK’s current account balance, but can also be lethal to citizens in Yemen. The commission should also recognise the need for global collaboration (rather than competition) on issues like climate change and tax dodging.

Gender inequalities are not just about the gender pay gap. Despite messaging on the need to close the gender pay gap, the difference between men and women in terms of wealth, income and quality of work and wages is not well documented in the report. Moreover, to achieve what they call a good economy, which ‘allows each of us to flourish’ the commission needs to go further to explore gender based inequalities throughout society, including for example violence and responsibilities for care work, recognising that all public policies can have a differentiated impact on men and women.

Productivity of what for what? The trends around stagnating productivity are quite compelling and get a lot of attention in the report. However seeking an increase in productivity in and of itself, must be qualified by defining productivity appropriately, particularly the output side of the input-output equation. The report says that we need a clearer understanding of the goals of economic policy and that GDP is an insufficient measure. This appreciation as to the importance of what we measure and what it means for people and planet should also be applied to the ambition for increasing productivity, particularly as it is something that the UK Treasury has already endorsed in its response to this report.

Overall, this is a very welcome report at a time when we need momentum to push for a constructive and inclusive vision for our economies all over the world. And it’s great to see an influential think tank and opinion leaders contributing to this conversation. With momentum in mind though, I would challenge the title of the report, which suggests we need a vision that is new. In fact, there are lots of ideas and principles that already exist that we should build on. In the report An Economy for the 99%, which I authored in January promoting a Human Economy, I suggest that:

vision for our economies all over the world. And it’s great to see an influential think tank and opinion leaders contributing to this conversation. With momentum in mind though, I would challenge the title of the report, which suggests we need a vision that is new. In fact, there are lots of ideas and principles that already exist that we should build on. In the report An Economy for the 99%, which I authored in January promoting a Human Economy, I suggest that:

“Far from being radical or brand new, this vision for a human economy is rooted in principles and values that have long been central for people, communities and movements all over the world. From feminist economics, which recognizes that justice, sustainability and care are of central importance, to ecological economics, which has long recognized the interdependence of human economic and natural eco-systems and the need to value natural capital, to the ground-breaking work of Amartya Sen, there are many established principles and concrete examples of success on which the concept of a human economy is based. We can also see these principles echoed in most of the world’s religions, in what neuroscience tells us makes our brains light up, in what psychology tells us people really need to live well and in what most people, when they have the chance to stop and think, believe really matters.”

So given that this is not new – let’s get on with taking it to the next level…

September 13, 2017

Complexity v Simplicity: the challenge for Campaigners and Reformers

Had a few thought-provoking conversations on this last week. I increasingly see most problems (social, political,

How do we talk about this?

economic) as complex, i.e. arising from multiple causes in interconnected systems, often highly dependent on the specific context and history of any given place/population. My campaigner friends generally hate such talk, because their gut feeling is that it makes taking action to change the world much more difficult. We often end up arguing about Make Poverty History, which from a campaigners’ point of view can be seen as a great success in terms of public mobilization and rich government commitments to aid and debt relief, but which I hated because of its implicit (and wrong) message that poverty could be ended simply by the actions of outsiders on aid, debt and trade.

So when (and what) is it OK to simplify, and what are the costs and benefits of doing so?

When I arrived at Oxfam, I was given its recipe for the perfect campaign: PSV – a clear problem, solution and a villain (heroes are optional). For example, the campaign for Access to HIV medicines in the early 2000s had problem = patent rules restricting access; solution = clarify international law to allow governments to override the rules; villain = Big Pharma helpfully taking the South African government to court to stop it over-riding patent rules during the early years of the HIV pandemic. Although battles continue, the campaign helped bring about major changes in policy and practice on access to medicines.

But when you think in terms of systems, all three PSV elements need to be heavily qualified. Problems are usually multiple, interconnected and not all obvious. Solutions vary according to time and place. Villains are seldom monolithically villainous and may also turn out to be potential problem solvers/heroes. And you are likely to be at least partially wrong in your identification of all 3 and to have to change your views as you learn more. Ouch.

But when you think in terms of systems, all three PSV elements need to be heavily qualified. Problems are usually multiple, interconnected and not all obvious. Solutions vary according to time and place. Villains are seldom monolithically villainous and may also turn out to be potential problem solvers/heroes. And you are likely to be at least partially wrong in your identification of all 3 and to have to change your views as you learn more. Ouch.

What to do? There is good and bad simplification. Good simplification doesn’t overclaim: A clear problem statement can still acknowledge complexity but say ‘this needs to be fixed’. A proffered solution should emphasize that this is not a magic bullet but explain why this solution, among others, is worth a try. On close inspection a villain is likely to be itself a complex system – look inside a company or a government and you are likely to find some allies that can work with you to find a solution.

More broadly, working for change in complex systems requires a change in approach at lots of levels, starting with  leadership. I’m currently reading a fascinating new book (review to follow) on China’s development success, which identifies the genius of the Chinese leadership since 1978 as partly about accepting the limitations that complexity places on leadership. It argues that after 1978 they moved from Mao’s disastrous attempts at Command and Control to a fuzzier (‘directed improvisation’) attempt to influence the decisions and behaviours of China’s 50 million (!) public servants. Leaders set the boundaries of the broad environment, but then it’s up to local officials to improvise and find new solutions (often to the surprise of the party bosses in Beijing).

leadership. I’m currently reading a fascinating new book (review to follow) on China’s development success, which identifies the genius of the Chinese leadership since 1978 as partly about accepting the limitations that complexity places on leadership. It argues that after 1978 they moved from Mao’s disastrous attempts at Command and Control to a fuzzier (‘directed improvisation’) attempt to influence the decisions and behaviours of China’s 50 million (!) public servants. Leaders set the boundaries of the broad environment, but then it’s up to local officials to improvise and find new solutions (often to the surprise of the party bosses in Beijing).

Thinking about complexity has also brought me round to an argument I used to hate. If problems/solutions are complex and context-specific, outsiders might be better advised to argue about process – who needs to be involved and supported (eg civil society, women) in finding the solutions, rather than claiming to have the solutions themselves.

When I looked at how aid agencies design their theories of change for working in messy places like fragile and conflict affected states, I found an interesting bifurcation between, on the one hand, trying to engage with complexity at multiple different sites and levels (a bit like acupuncture) and arguing that this is all too difficult for outsiders. They should instead stick to some broad ‘enabling environment’ issues, usually around access to information, and leave the rest to local actors.

The Chinese Leadership also have some lessons to offer in terms of how to talk to the public/activists about all this. Don’t gleefully say ‘hey, it’s all really complex and so you have to be really smart like me’ (an unfortunate trait of a lot of systems thinkers I have run into). Do communicate through analogy (as in the memorable Chinese version of adaptive management: ‘crossing the river by feeling the stones’).

The inside of my head

I’ve found analogies by far the best way to talk about complexity and systems thinking, as you can plug into people’s lived experience of complexity, and highlight the absurdity of linear approaches: Would you design an 18 year logframe for your newborn baby, setting out your parental activities, outputs and outcomes in advance? Hope not. Ditto cycling/driving across town – a plan of intended velocity and direction for the entire trip would lead to an early grave; instead it’s all about fast feedback and adaptation – learning by cycling. You get the picture (and so does everyone else).

Conclusion? It is possible (and preferable) to keep complexity in mind, while tapping into the virtues of simplicity. Aims/direction of travel/principles need to be simple and memorable; problems to be fixed and process should be kept simple. But beware simplistic solutions and caricature villains – that’s when simplicity can make changes harder to achieve.

Thoughts?

September 12, 2017

Book Review: The Road to Somewhere, by David Goodhart

There was a moment a few years ago when I was walking through Brixton with my son, Calum. I was tediously droning on about how much I loved the cultural and ethnic kaleidoscope, compared to the plain vanilla places where I grew up. Calum suddenly turned on me – ‘you’re just a tourist; you visit on Saturdays. It’s different growing up here’ and proceeded to fill me in on the harsher side – the back and forth of endless attempted muggings as a teenager, the constant low level fear (he has since declared that there’s nowhere he’d rather he grew up, and wants to live in south London for the rest of his life…)

droning on about how much I loved the cultural and ethnic kaleidoscope, compared to the plain vanilla places where I grew up. Calum suddenly turned on me – ‘you’re just a tourist; you visit on Saturdays. It’s different growing up here’ and proceeded to fill me in on the harsher side – the back and forth of endless attempted muggings as a teenager, the constant low level fear (he has since declared that there’s nowhere he’d rather he grew up, and wants to live in south London for the rest of his life…)

Calum recently gave me David Goodhart’s new book, The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics, which sets out the critique of Brixton tourists in rather more detail.

For a wannabe contrarian like me, David Goodhart is a bit of a role model (Prospect magazine never recovered after he left). He combines good writing, sharp argument and survey data to pick holes in lazy arguments and received wisdom, then sets out some mildly heretical proposals for how to do things better. The Road to Somewhere is provocative, original and well worth careful reading (even if you end up disagreeing with it).

The starting point is, of course, Brexit (it’s primarily about the UK, but touches on the Donald too). The vote to leave the EU was an existential blow to the people who thought they ran the country (I remember the morning after, for the first time feeling like a member of a reviled elite). The vote didn’t follow party lines – solid Labour Lambeth, where I live, was the second biggest remain voter after Gibraltar. The third was our neighbouring London borough, Tory-dominated Wandsworth.

The starting point is, of course, Brexit (it’s primarily about the UK, but touches on the Donald too). The vote to leave the EU was an existential blow to the people who thought they ran the country (I remember the morning after, for the first time feeling like a member of a reviled elite). The vote didn’t follow party lines – solid Labour Lambeth, where I live, was the second biggest remain voter after Gibraltar. The third was our neighbouring London borough, Tory-dominated Wandsworth.

Goodhart’s big idea is a new faultline, between ‘Anywheres’ and ‘Somewheres’, with Brexit/Trump a sign of a revolt of the Somewheres who had been ignored by the political class for the previous 30 years.

Drawing heavily on attitude survey data, he characterizes the mindset of Anywheres as ‘progressive individualism’. On the basis of survey questions – e.g. those who disagreed with the idea that you have to be white to be British (!), he estimates their number at 25%. They include a small band (3-5%) of hard core ‘global villagers’ entirely indifferent to national identity. Anywheres have been deracinated by their university education, often move away from their home town, and love London (Goodhart really has it in for London – ‘A rootless, laissez faire, hyper-individualistic, London-like Britain does not correspond to the way most people live, or want to live’).

On the basis of people who say they would like Britain to be how it used to be, or that employers should hire British workers first, he puts the numbers of Somewheres at a bit over 50%. They include a small group of ‘hard authoritarians’ (eg the 10% still opposed to gay marriage) – but most of them are ‘decent populists’ who are perfectly capable of accepting their non-white neighbours while worrying about the level of immigration. Somewheres tend not to go to university, stay near their mums (yes, there’s data on that) and have ‘ascribed identity’ stemming from where they live, or who they are, in contrast to the ‘achieved identity’ of Anywheres defined by their jobs and qualifications.

Chapters then unpack the Somewhere-Anywhere divide in party politics; the big issue of nationalism and immigration; the economy; social mobility and the family. In all these areas, Goodhart argues that the chips have been stacked against the Somewheres: politicians have ignored their concerns on immigration and identity; traditional jobs have disappeared; family policy has failed to support traditional family structures that are often valued by lower income citizens, in favour of the equality in the workplace agenda favoured by the Anywheres; the flipside of the emphasis on social mobility is that if you are not (whether through choice or capability) mobile, you are seen as a second class citizen.

Overall, the book feels like Goodhart is trying to influence different fractions of the Anywhere elite, mainly on the

The Gordon adn Gillian show

Left. He delves into New Labour’s inability to respond to populism (aka ‘the new Socialism’ with its overwhelmingly working class base), so unforgettably captured by Gordon Brown’s election campaign confrontation with Gillian Duffy. On this argument, the Corbyn labour party has moved more towards the Somewhere vote on economic policy and Brexit, but is solidly Anywhere on social policy (and a lot of the Anywheres don’t seem to have noticed the Brexit bit yet, judging by Jeremy Corbyn’s rapturous reception by Glastonbury’s Anywheres).

After such a good diagnosis, his final ‘so what’ chapter is a bit disappointing, comprising action on Voice (more localism, less London); the National (immigration, ID cards, national preference in procurement) and Society (shift resources from universities to vocational education and apprenticeship, revalue two parent families in social policy). But the real value is in the Anywhere/Somewhere framing, which is very useful when trying to disentangle issues of cultural identity and politics.

Assuming you think there is some value in the core argument, there are plenty of implications too for those working on international development. Goodhart is arguing that the chattering classes need to pay far more attention to how identity is constituted, strengthened and threatened, rather than just believe its own analyses on ‘what is good for you’ – plenty of echoes with the arrogance of aid technocrats there. But the underlying challenge is perhaps that a lot of people in the aid industry are among that small percentage of global villagers, who are very cut off from their own societies – not a good place to be. I’d be interested in your thoughts on this.

Here’s a longer, fairly critical review from the Guardian’s Jonathan Freedland, and the Economist, which has the best ‘digested read’: ‘David Goodhart, a “post-liberal”, seeks to accommodate the decent elements of identity-based populism’.

September 11, 2017

DFID is 20 years old: has its results agenda gone too far?

DFID just turned 20 and Craig Valters (right) and Brendan Whitty (left) have a new paper charting its

DFID just turned 20 and Craig Valters (right) and Brendan Whitty (left) have a new paper charting its changing relationship to results

changing relationship to results

Focusing on results in international development is crucial. At this level of abstraction, how could one argue otherwise? Yet it matters how development agencies are managed for these results. We know that with proper management systems, aid interventions can be very effective; but if poorly managed, they can be harmful.

Yesterday, we published a paper which analysed how and why the results agenda emerged in the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID). Our primary focus was on the politics of this story, how it intersected with DFID’s management, and the responses to results changes. We asked whether DFID’s results management is fit for purpose; that is, does it reflect the UK’s development ambitions?

We think this story is important and timely. There is growing pressure—from politicians, the public and the media—for aid spending to prove its worth. It is time for a serious conversation about what results DFID and the UK government can achieve and how they should manage their interventions.

The story of DFID: 1997-2017

In 1997, the New Labour government created DFID as an independent department. The Secretary of State, Clare Short, forged an anti-poverty agenda based on principles of global partnership. Instead of being accountable for directly delivered results, DFID was judged on its contribution to a series of international targets. Under Hilary Benn’s leadership, this was maintained. The UK committed to spending 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) on aid, hosted the G8 summit where leaders committed to Make Poverty History, and helped shape the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness.

2007 onwards shows an erosion of Clare Short’s internationalist agenda in order to justify the 0.7% commitment. The political climate became more troubled: the UK economy began to suffer, and public support for aid declined, yet DFID’s budget grew. Together, the new Secretary of State, Douglas Alexander, and DFID’s leadership started to develop results-based management reforms focused on their own deliverables.

2007 onwards shows an erosion of Clare Short’s internationalist agenda in order to justify the 0.7% commitment. The political climate became more troubled: the UK economy began to suffer, and public support for aid declined, yet DFID’s budget grew. Together, the new Secretary of State, Douglas Alexander, and DFID’s leadership started to develop results-based management reforms focused on their own deliverables.

Andrew Mitchell accelerated the agenda. In 2010, the ‘results agenda’ became synonymous with the reforms he made – the new Business Case, Bilateral Aid Review and changes to Results Frameworks. For some these reforms were evolutionary, for others they provoked major concerns. In 2015, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) – formed under Andrew Mitchell – critiqued the results agenda for encouraging a focus on short-term economy and efficiency, over long-term, sustainable impact.

Ongoing internal reforms in DFID appear to be highlighting possible routes towards more flexible and adaptive programming. Yet there are numerous contradictory pressures within the department, and staff remain constrained by the political environment and the results agenda.

What does this story tell us?

Firstly, crucial elements of development management systems are driven primarily by party political pressures, rather than by the complex realities of aid implementation. As a consequence, DFID has adopted some ambitious, untested or unfit for purpose reforms.

Firstly, crucial elements of development management systems are driven primarily by party political pressures, rather than by the complex realities of aid implementation. As a consequence, DFID has adopted some ambitious, untested or unfit for purpose reforms.

Secondly, DFID staff members have interpreted these reforms differently based on their professional interests and policy beliefs. The results agenda empowered some (such as statisticians and economists) and marginalised others (such as those working on governance).

Thirdly, DFID has been pulled steadily back to central government accountability standards, reinforcing centralised control and fixed target-setting. This has sat uneasily with the realities of development assistance, which often require local ownership and flexibility.

Finally, the 0.7% commitment at a time of austerity has both protected and exposed DFID; requiring it to deliver quality aid, while under pressure to spend, working in fragile states, with relatively fewer staff and fixed results commitments.

So what’s next?

The results agenda has focused DFID on what it can achieve. In some form, this needs to remain. Yet it has shifted this focus to the short-term, prioritised upwards rather than downwards accountability, and unhelpfully promoted blueprint planning. A different approach is required.

Create a results agenda fit for purpose

Change the assumption that we can predict, with certainty, what our interventions will achieve. Rejecting this world-view means taking results and accountability more seriously, not less. Interventions need to be based on the best  available information, with regular testing to see if they are on the right track, rather than being overly focused on pre-planned numbers.

available information, with regular testing to see if they are on the right track, rather than being overly focused on pre-planned numbers.

Be more honest with the British public about aid

Political leadership is crucial. According to Andrew Mitchell, ‘there’s absolutely no reason why this should be complex for the public. It’s the job of politicians to explain complex things to the public in a way that they understand.’ Fair enough. But let’s not patronise them either. A more honest conversation about aid and development is required – how, where and why it works, why results aren’t always tangible, and why it sometimes fails.

Support reform in how DFID is managed

Reformers within DFID are seeking positive change through ensuring flexibility, encouraging greater learning, and focusing on the causes of poverty and conflict. These reformers require support. Beyond that, the full implications of 0.7% should be rethought. The government must adequately staff in-country expertise, commit to longer-term programmes, and reconsider where money can be spent effectively – which won’t always be in fragile states.

Do we need a reality check?

Reformers inside and outside of DFID have to tread a careful path – keeping radical alternatives alive while tinkering around the margins. The negative elements of the results agenda cannot easily be overturned. It is tied to wider political decisions that have shifted DFID’s culture: a (re)centralisation of power to the centre over country offices, increased privatisation and a gradual move towards aid in the ‘national interest’.

Reformers inside and outside of DFID have to tread a careful path – keeping radical alternatives alive while tinkering around the margins. The negative elements of the results agenda cannot easily be overturned. It is tied to wider political decisions that have shifted DFID’s culture: a (re)centralisation of power to the centre over country offices, increased privatisation and a gradual move towards aid in the ‘national interest’.

This story brings the UK’s international ambitions into the light. Part of the political question is: are we looking to buy results, or support longer term deep-rooted changes? We presume that politicians across the ideological spectrum have an interest in the latter too. We need to move beyond a results agenda which narrows the gaze of the development industry, to an approach which takes tackling the causes of poverty and conflict seriously.

September 10, 2017

Links I Liked

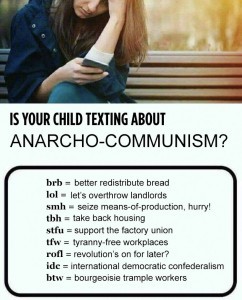

Shock revelation – our kids are ‘Anarcho-Communists’

‘We need no more marchers. We need more mayors’. Great reflection/book review by Nathan Heller on modern protest

Bollywood’s hot new topics: open toilets, menstrual hygiene and erectile dysfunction

What Guatemala’s political crisis means for anti-corruption efforts everywhere. Backgrounder on UN’s ground-breaking work in Central America

Oh dear. Giving Danish politicians more evidence makes their decision-making worse, not better ht Ranil Dissayanake

Oh dear continued: Uberblogger Chris Blattman has fallen out of love with blogging. Any evidence for his claim that overall blog readership is falling?

“I’m breaking my vow to remain silent on public affairs out of profound sadness.” Desmond Tutu condemns Aung San Suu Kyi’s silence on the Rohingya

A new evaluation from CGD and IPA of a Liberia private school pilot finds a mixed picture: if you pump lots of money in, you get better results. Wonkwar over what that means already well under way

Man plants a tree in the same place every day — 37 years later, the world is amazed by the result

September 7, 2017

Living in interesting times: one year in the life of Oxfam’s Women’s Rights Director

Nikki van der Gaag looks back on her first year as Oxfam’s Gender Justice and Women’s Rights Director.

‘May you live in interesting times’ is a Chinese saying that could equally be a promise or a curse. In the past decade, there can’t have been many more interesting times to be working on women’s rights and gender justice.

I began my new post three months after the murder of female MP Jo Cox in the UK, and almost exactly two months before the surprise election of President Donald Trump on November 8. All over the world, the past 12 months have seen rising right-wing populisms and religious fundamentalisms threatening the rights that women have fought for over many decades.

One of Trump’s first acts in post was to sign an executive order to reinstate the Global Gag Rule, restricting US funding for any family planning programmes connected to abortion, and then extending this to all global health funding. This amounts to almost $9 billion, 15 times more than any earlier rulings. It is already having devastating impacts on women’s lives.

In February 2017, President Putin’s Government in Russia passed an amendment decriminalising many forms of domestic violence. ‘Moderate’ violence within families is now an administrative, not a criminal offence, which means that unless bones are broken, the perpetrator will only get a fine or a maximum of 15 days in prison – unless this happens more than once a year. This in a country where estimates are that a woman dies every 40 minutes from domestic abuse.

Three weeks later, on February 27, the Government in Bangladesh passed a law which allows marriage under the age 18 (which is otherwise illegal) to take place in “special circumstances – that is, with parental consent and with permission from the courts, deemed in the “best interest of the underage female or male”. The child’s consent is not required. Bangladesh still has one of the highest rates of child marriage in the world.

In addition, funding to women’s rights organisations has fallen by more than half over the past five years from donors, despite recent studies suggesting that the work of such groups brings the greatest long-term improvement to women’s lives.

In addition, funding to women’s rights organisations has fallen by more than half over the past five years from donors, despite recent studies suggesting that the work of such groups brings the greatest long-term improvement to women’s lives.

So in many ways it has been an unprecedentedly depressing year for women’s rights. But the reaction to these events has also been unprecedented – and uplifting.

In January, Trump’s actions galvanised Women’s Marches all over the world. Many thousands (actually, millions) came together in solidarity and with humour to stand up for women’s rights. And in July a Family Planning Summit in London,pledged $5 billion to try to fill some of the funding gap caused by the Global Gag rule.

This August, in Lebanon, laws which allowed for rapists to go unpunished if they married their victims were scrapped amid much celebration by women’s rights activists and their supporters. This followed the revoking of similar laws in Jordan and Tunisia.

The campaign in Lebanon by Abaad, a gender justice organisation, included billboards of women in wedding dresses that were bloodied and torn with the caption: “A white dress doesn’t cover up rape,” and wedding dresses hung from a noose, on Beirut’s seafront. But campaigning will continue as the rape clause will still apply if the victim is underage.

Campaigning for gender justice and women’s rights increasingly involves not only women and women’s rights  organisations, but men as well. In May, I spoke in Belgrade at the launch of the second global State of the World’s Fathers report, published by the MenCare campaign, which argued that gender equality will never be achieved unless men are involved, including sharing the paid and unpaid care work equally with women.

organisations, but men as well. In May, I spoke in Belgrade at the launch of the second global State of the World’s Fathers report, published by the MenCare campaign, which argued that gender equality will never be achieved unless men are involved, including sharing the paid and unpaid care work equally with women.

New alliances are being built, new forms of resistance invented. Oxfam, and other international non-governmental organisations (INGOs), have many years of experience of working with some of the most extraordinary women and women’s and gender justice organisations around the world.

There are three main things that INGOs can do to resist these threats, build alliances – and making sure one day gender equality becomes the norm in every single country:

First, ensure that feminist, women’s rights and gender justice organisations get the funding they need for this resistance. A review by the Association of Women’s Rights in Development showed clearly that money for such organisations is shrinking rather than growing.

Second, use INGOs’ size and reach to support feminist movement-building and increase the visibility and power of gender justice work. This needs to be done with care, so that they support rather than swamp, and ensure that their relative size is a help and not a hindrance. It also means being humbler in their claims about what they as individual organisations can contribute. No one INGO has the monopoly on what’s important for gender justice. Those in INGOs need to listen to Southern organisations and partners and to feminists from the Global South so that their agendas are truly driven by those they claim to serve.

Last but not least, they need to reflect more on their own practice, ensuring that they put their own houses in order, acknowledging and addressing sexism and gender inequity in all that they do.

These are challenging times. The coming year is likely to continue to be ‘interesting’ for women’s rights and gender justice. But I take heart from another saying, this time an African proverb: ‘When you go alone, you go fast, but when you go together, you go far.’

September 6, 2017

Book Review: Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms, by Cristina Bicchieri

Alice Evans was raving about this book on twitter, so I scrounged a review copy and read it on holiday (that’s just  how I roll). Verdict? A useful resource on an incredibly important topic (see my previous blogs), but sorry Alice, no cigar.

how I roll). Verdict? A useful resource on an incredibly important topic (see my previous blogs), but sorry Alice, no cigar.

Why important? Because norms are the neglected heart of development and social change – how people see themselves and their neighbours, what is considered (un)natural etc has the dual quality of seeming constant (the rules by which we live), while in fact continually evolving. Think of attitudes to homosexuality, disability, gender, violence against children – all have changed massively over the last few decades, and we have only the thinnest understanding of why/how. Instead activists and aid agencies often prefer to focus on the short-term and the tangible – policies, spending commitments, laws, activities.

So it’s great that Bicchieri, a prof at the University of Pennsylvania, sets out to shed some light, building on her work with UNICEF trying to change ‘bad norms’ on everything from breast-feeding to Female Genital Cutting (FGM has now become FGC – no idea why).

In diagnosis, Bicchieri painstakingly distinguishes between different phenomena that are often lumped together as ‘norms’ (see graphic). Disentangling preferences, expectations, norms, customs and conventions is hard work – not always helped by the academic prose. I know it’s unfair to quote in isolation, but here’s a section that I actually underlined as helpful: ‘Our commitment to these moral norms is independent of what we expect others to believe, do, or  approve/disapprove of. Social norms instead are always (socially) conditional, in the sense that our preference for obeying them depends upon our expectations of collective compliance.’ Don’t know about you, but I really struggle with page after page of this kind of writing. Lot of nodding off and re-reading of paragraphs…..

approve/disapprove of. Social norms instead are always (socially) conditional, in the sense that our preference for obeying them depends upon our expectations of collective compliance.’ Don’t know about you, but I really struggle with page after page of this kind of writing. Lot of nodding off and re-reading of paragraphs…..

But the distinctions do help. Take this on campaigns to encourage breast feeding that tried merely to raise awareness of the health benefits: ‘Such interventions were not accompanied by the understanding that the practice was supported by widely held social expectations. Even if we were to succeed in convincing a young mother of the benefits of immediate breastfeeding, would she dare incur the wrath of her mother-in-law, the scorn of other women, and the accusation that she was risking the life of her child?’ What people expect other people to think turns out to be key, and often neglected in attempts to shift norms and behaviours.

The measurement chapter works through some behavioural economics/nudge style experiments but then regretfully accepts that real life takes place outside the lab, and is a lot messier and harder to measure. All we can do there is present people with hypothetical scenarios to try and understand how norms could change – eg if your community stopped opposing X, would you be more likely to do it? One of the interesting practical implications of this chapter is that identifying contradictory norms can be a good entry point for changing behaviours – eg in Yemen Oxfam used social norms around protecting children’s health to undermine normative support for early marriage.

The chapter on changing norms argues that similar processes are required, whether you are creating, changing or trying to get people to completely abandon norms. There must be shared reasons for a change (new information, changes in personal beliefs, or a change in social expectations – what we think other people think). There are collective action problems that make it higher risk to be the first mover (who wants to be the first gay in the village?) – remedies include public pledging (‘I will only marry an uncut woman’) to change people’s ‘perceptions of perceptions’.

abandon norms. There must be shared reasons for a change (new information, changes in personal beliefs, or a change in social expectations – what we think other people think). There are collective action problems that make it higher risk to be the first mover (who wants to be the first gay in the village?) – remedies include public pledging (‘I will only marry an uncut woman’) to change people’s ‘perceptions of perceptions’.

Norm change in practice happens through three main ways: a steady drip drip of information and first hand experience that existing norms need to change (eg seeing that breast-fed babies don’t die), a ‘conversion moment’ – critical juncture eg when everyone heads for Tahrir Square and the population loses the fear to speak out and a third, less useful ‘subtype model’ where people ringfence a norm change by saying ‘ah well, it may work for that group, but not for me’.

Looking at successful programmes, Bicchieri stresses the value of ‘appealing on an emotional level, eliciting strong emotions, like fear and disgust’ when, for example, trying to shift norms on open defecation. When (as in the case of open defecation), you need to get everyone to make the change for it to be effective, it helps if the group can also make a collective decision to sanction transgressions (one Indian village set up a cow jail and arrested the cows of offending defecators, which were only freed after a fine was paid and the offender publicly humiliated).

As the last paragraph shows, case studies are really helpful in landing some of the more abstract fancy footwork. Unfortunately, in this book they are rather cursory – a really chunky opening case study on eg equal marriage, foot binding, FGM or open defecation, would have really helped bring the ideas to life and give something for us less conceptual types to cling to.

The chapter on ‘tools for change’ was the most important, the shortest and the most disappointing. It set out four approaches – legal, economic, media and small-scale deliberation. Legal tends not to work for social norms (see anti-corruption laws around the world), but ‘if the law is to have any value at all, it needs to stick close to the norms’ – interesting caveat. The most enthusiastically endorsed vehicle for change at scale is…… soap operas. OK, the

Norms change over time

examples are great, covering issues like condom use, breast feeding and in a spectacular recent Indian soap, toilets. But they only work if you have the power and budget to commission TV series and I suspect that lots of them end up being worthy rubbish with terrible audience figures.

As with legal interventions, Bicchieri stresses that successful soaps need a ‘combination of recognisability and difference’ – if your characters are an unconvincing collage of politically correct positions, no-one will identify with them, but if they are flawed and true to life apart from the one issue you are trying to tackle, then you might get somewhere.

A couple of other useful insights for campaigners: Public messaging about failures and problems can actually make matters worse (because it makes it sound like everyone is doing it – tax evasion, beating their wives etc). What works is messaging about good stuff – how many people are paying taxes, recycling etc, especially among your neighbours. Monetary incentives can also backfire, because they shift the logic from moral to market (it’s OK to arrive late to pick up my kid, because now I just have to pay a fine).

At a more subterranean level, I wondered about the kind of person the book is both aimed at and talks about. It’s aimed at an ill-defined developmental ‘we’, Platonic Guardians at UNICEF or elsewhere in the system, charged with freeing misguided populations from their harmful practices – true in some cases (eg breastfeeding) but also problematic (eg when the Guardians are wrong or malign). What is missing is any real consideration of power, and the link between power, social and economic structures and norms. That surely shapes what can/can’t be done, especially when the shifts extend beyond the restricted UNICEF world of win-win interventions on breast feeding and the like. What’s also missing is the big historic shifts, eg why there’s growing support for gender equality around the world. This is a book for small scale tinkering not transformation.

Although it is never spelled out, the imaginary ‘typical person’ in this book lives in a community, whose primary relationships are face to face with family and neighbours. That certainly doesn’t describe my life, how about yours? Missing is fragmentation, and the way social-media-led communities are easing the path to norm change (good or bad).

It also comes across as excessively rationalist – people weighing up their behaviours based on their expectations

about what their neighbours and ‘reference networks’ think. In Daniel Kahneman’s terminology, that’s all thinking slow, when actually, most people think fast most of the time, living with contradictions and confusions (I worry about climate change; I also take lots of planes – I just try not to think about it) rather than trying to nail everything down. And faith and religion, with their huge impact on norms, barely get a mention.

So, good topic, lots of food for thought, but in the end, a lot of blind spots and a rather frustrating book – any other recommendations for what to read on how norms change, and how to influence them?

Thanks to Alice Evans for comments on an earlier draft of this post

September 5, 2017

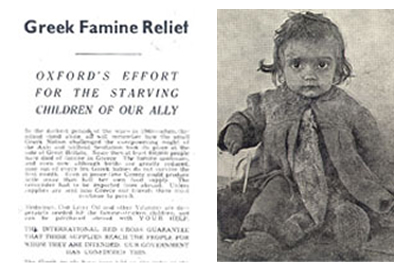

From Starving Greece in 1942 to Yemen and Nigeria in 2017: Why Total War is still Wrong

Ed Cairns

worries that, 75 years since Oxfam was founded, we have returned to an era of heartless total war

When a group of people met in Oxford’s University Church on 5 October 1942, they talked about the dire shortage of food in Nazi-occupied countries, and how to raise money and get relief through the Allies’ blockade. They agreed to set up something called the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief (whose name was later shortened to Oxfam), fuelled by a desire to help, but perhaps more importantly by a belief that that blockade was wrong.

One of those gathered in the church’s old library was Gilbert Murray, Oxford’s Regius Professor of Greek until a few years before. He argued how difficult it would be to advocate for aid without challenging the Government’s policy of blockade, which Churchill himself had set out in 1940.

This was part of a wider debate in wartime Britain on whether it should wage ‘total war’, including blockades and the bombing of cities, or whether, even when facing Nazi Germany, wars should have limits. Relatively few people questioned ‘total war’, but those that did argued that we should not punish hungry people – through restricting food and other supplies – whose only crime was living under an odious regime.

Relatively soon after the war, the critics of ‘total war’ seemed to win the argument. When the new Geneva Conventions were agreed in 1949, they restricted the means and methods of warfare; flatly forbade starvation as a tactic; prohibited the destruction of vital services; and obliged warring parties to allow the unimpeded passage of humanitarian aid. That has been the cornerstone of international humanitarian law ever since.

Relatively soon after the war, the critics of ‘total war’ seemed to win the argument. When the new Geneva Conventions were agreed in 1949, they restricted the means and methods of warfare; flatly forbade starvation as a tactic; prohibited the destruction of vital services; and obliged warring parties to allow the unimpeded passage of humanitarian aid. That has been the cornerstone of international humanitarian law ever since.

But has the age of ‘total war’ really been consigned to the past? The prospect of a nuclear strike, inevitably leading to the ‘total’ destruction of civilian areas, doesn’t seem quite as far-fetched as it has. But the war of words between Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump is not the only reminder of ‘total war’ – as Oxfam’s staff see in a saddening number of crises today.

The number of people killed in war in 2016, 157,000, is a fraction of those who died in the world wars of the twentieth century. Despite the rise in conflicts in the last ten years, the sheer numbers killed in the terrible bombings of the Second World War, conventional and atomic, have never been repeated.

But ‘total war’ was never about numbers. It was an attitude of mind that no holds were barred, and that if civilians had to be, effectively, punished for being in the wrong place, ruled by the wrong side, that was too bad.

A few months ago, I saw this in north-east Nigeria, the region blighted by the conflict between Boko Haram and the military operations against it. The horror at Boko Haram was beyond doubt. I listened to men and women forced from their homes by the group’s brutal attacks, in which so many others had died.

But time and again, I also heard this kind of story from a 40-year-old woman, Hadiza. ‘Both Boko Haram and the army,’ she said, ‘have killed so many men. Boko Haram killed 4 of my cousins. But the army took my husband and 7 others. My husband did not survive.’

I heard that Nigeria’s army used multiple rocket launchers to deny Boko Haram access to land – land in which

Boko Haram

civilians were inevitably killed by the rockets as well. I heard that the government restricted access to food, fearful that it could sustain Boko Haram fighters, even as the threat of famine remained. And I heard many stories that backed up Amnesty’s research of deaths in military custody, from disease, hunger and killings, as young men were presumed to back Boko Haram until proven innocent. It all felt a bit like ‘total war’, in which, as a 2015 study put it, Nigeria’s army forces defined its role in terms of killing Boko Haram, not saving civilians.

North-east Nigeria has been only one place on the brink of famine in this extraordinary year. Millions more people have faced this threat in Somalia, South Sudan, and, more than anywhere else, Yemen. All sides in Yemen’s conflict have attacked civilians, and restricted their access to food. Among these, the Saudi-led coalition has enforced a de facto blockade on Yemen’s main port, Hodeidah, and closed the capital’s airport to commercial flights, greatly complicating the aid effort. As one of my colleagues ruefully put it, ‘Yemen isn’t starving, it’s being starved.’

One could go on. It’s three years since Gaza’s last major violence, when more than 2,000 people were killed. Now Israel and the Palestinian Authority are cutting electricity to the enclave to put pressure on Hamas, the de facto authority. Not war, but in many respects the impact on people living in Gaza is as bad. After 2014’s conflict, half of the sewage treatment centres didn’t work. None do today. And this is on top of Israel’s blockade in place for almost a decade, which has devastated Gaza’s economy.

In the Second World War, reasonable people, facing terrible threats, once thought that blockading civilian populations, and bombing civilian cities, was acceptable. Today’s conflicts are very different, but still often marked by, at best, accepting that large numbers of civilians will suffer, and, at worst, a deliberate plan to use civilian suffering to put pressure on the enemy. The consequence is much the same: to punish desperate people, whose only crime is the authority they live under.

Seventy-five years ago, this was an issue that divided at least parts of British opinion. Today, these crises are thousands of miles away, but in every case, Britain is involved. It has sold £3.6 billion of arms to Saudi Arabia since it started striking targets in Yemen; in the first eighteen months, 37% of those targets were ‘non-military’. The British Army trains Nigeria’s armed forces operating against Boko Haram. And the UK has been slow to speak out against the vast human cost of Gaza’s electricity crisis, though Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, in an earlier career, condemned Israel’s military action in 2014 as disproportionate, ugly and tragic – a good description for what is happening now.

Seventy-five years ago, this was an issue that divided at least parts of British opinion. Today, these crises are thousands of miles away, but in every case, Britain is involved. It has sold £3.6 billion of arms to Saudi Arabia since it started striking targets in Yemen; in the first eighteen months, 37% of those targets were ‘non-military’. The British Army trains Nigeria’s armed forces operating against Boko Haram. And the UK has been slow to speak out against the vast human cost of Gaza’s electricity crisis, though Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, in an earlier career, condemned Israel’s military action in 2014 as disproportionate, ugly and tragic – a good description for what is happening now.

It’s difficult not to think that this would sadden Gilbert Murray and the others who gathered to found the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief in 1942. Seventy-five years later, civilians are still being punished, through blockades and military action that hits combatants and civilians alike. The campaign against total war goes on.

September 4, 2017

Book Review: How to Resist: Turn Protest to Power, by Matthew Bolton

Full disclosure: Matt Bolton works for Citizens UK, an organization of which I am a big fan, and who my son works for, but if you’re OK with that level of bias, read on.

for, but if you’re OK with that level of bias, read on.

Citizens UK is a fascinating community organization, with a reputation far beyond its relatively small size (currently about 30 full time staff). For a fuller description see its Wikipedia entry.Here’s my rave review of one of their biggest ever events, grilling the UK’s prime ministerial candidates just before the 2010 election.

Born out of the teachings of Barrack Obama’s community organizing guru Saul Alinsky, until now the best guide to its approach has been his wonderful but distinctly Vietnam-era ‘Rules for Radicals’ (1971). Now Citizen UK’s Deputy Director, Matthew Bolton has updated it with How to Resist, a brilliant guide to the theory of action behind Citizens UK and some of its even better-known campaigns for the Living Wage, Refugees Welcome and Safe Passage.

So what’s the secret sauce? ‘The starting point is: if you want change, you need power. You build up power through relationships with other people around common interests. You break down the big problems you face together into specific issues and identify who the decision makers are, who has the power to make the changes you need. Then you take action to get a reaction and build a relationship with the decision-makers. If they don’t agree to implement the changes then you escalate the action or turn to more creative tactics, learning as you go and celebrating the small wins as you build incrementally up to the bigger issues.’

Living wage campaign – starting them young

That para chimes very well with the kinds of approaches to power and systems in How Change Happens, and the incremental, adaptive thinking espoused by the Doing Development Differently coalition. But the difference with the latter is its emphasis on the bottom up – deep listening to the concerns of local people in order (‘it all starts with the question: what makes you angry?’) which forms the foundations of future campaigns.

The approach is a unique combination of vision and pragmatism – nowhere more so than the emphasis on the virtues of power. ‘We must rid ourselves of the negative associations with power so that we start to want power as much as we want change.’

Subsequent chapters set out the building blocks for an effort to ‘reclaim populism’:

Appreciating self-interest, both of those they seek to organize and those they seek to influence. That includes material self interest but also having fun – Citizens events are a ball, full of singing and celebration. Bolton has little time for the saintly, self-sacrificing organizer – ‘these days I feel that selflessness is part of the problem, not the solution’.

Practical tools: ‘The stick person’ is a way to help people identify their self interest; the one-to-one conversation (Citizens organizers have a quota of 121s that they aim for every week, sitting down and sounding out potential leaders for support and training); and power analysis (excellent, if a bit too focussed on formal/institutional power – Citizens not great on gender issues).

Turning Problems into Issues (‘problems lead to conferences and issues lead to action’): eg a general complaint

Abdul Durrant, HSBC cleaner and revolutionary

about low wages becomes the Living Wage Campaign, and suddenly it becomes campaignable. This in contrast to the Occupy Movement (which he’s very critical of) or a poignant image from Bolton’s early years: a three person demonstration on Brixton Hill, each person carrying a different placard – ‘Peace’, ‘Justice’ and ‘Equality’. They must have been Quakers…..

The Action is in the Reaction (and if necessary, in the over-reaction). It is not about numbers on the streets, but about getting a response from the decision makers you are trying to influence, and that requires ‘respectful confrontation and constructive tension’ – all illustrated by a lovely example of Abdul Durrant, a Citizens-trained cleaner, standing up at an HSBC annual meeting to demand a living wage from Sir John Bond, the boss whose office he cleaned (Bond ended up giving him a reference when Durrant applied for a job as a trade union organizer!)

Unusual Allies and Creative Tactics: lots of theatre, avoid the boring marches, make it fun

‘The Iron Rule: never do for others what they can do for themselves’

I have a few quibbles. The book is primarily aimed at individual activists, but that’s not how Citizens UK works. Instead its members are the institutions most relevant to poor communities – schools, hospitals, workplaces and above all faith organizations. Campaigners take note – there isn’t even an individual membership on offer. And the title’s all wrong – this is about taking power and changing the world, not just resisting. But overall the book is mercifully brief, lucidly written and a perfect primer (or Christmas present) for the thinking activist.

September 3, 2017

Links I Liked

What did foreigners ever do for us? Hamburg Supermarket Edeka decided to remove all foreign items from its  shelves to make a point about xenophobia ht Sony Kapoor

shelves to make a point about xenophobia ht Sony Kapoor

Is it possible to calculate the return on investment for a research policy project? Here’s one attempt in Indonesia

Robin Hood had the right idea: Stephany Griffith-Jones on why the left needs to deliver on the financial transaction tax

Community paralegals (aka barefoot lawyers) are bringing access to justice to poor communities in India

Great 3 minute takedown by the Washington Post’s Karen Attiah of the New York Times’ “ooga-booga journalism” on Congo

A traditional feature of London’s Notting Hill Carnival is excruciating Dad Dancing by the police. But this year one copper’s moves went viral. His name is PC Dan Graham and he has previous. Interview and moves

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers