Duncan Green's Blog, page 113

July 27, 2017

Aidspeak: some of your best/worst responses to my call for examples

Well you took a few hours to get started in response to Tuesday’s post, but then the floodgates opened and an avalanche of bullshit  crashed over me via blog comments and tweets (and yes, mixed metaphors were discussed). Cheers guys. Within the aid business, a few patterns appear:

crashed over me via blog comments and tweets (and yes, mixed metaphors were discussed). Cheers guys. Within the aid business, a few patterns appear:

Management obfuscation which sheds almost no light on what is actually being discussed

This from ‘NGO worker ant’ on ending a role in their organization:

“We…are now at a point where we need to adjust our capacities to advance the multi-dimensional pathways to diversify the [YYY] network…One of these changes includes rolling-off the [XXX] position, and embedding capacities to support our diversifying [YYY] aspirations under the [ZZZ position]…We will leverage our existing capacities for greater reach and greater coherence of our ongoing governance, membership, and broader diversifying ambitions, with no additional cost to these priorities.”

Or this from Rasmus:

“DFAT’s governance programme in Indonesia aims to: ‘For its first phase, KOMPAK supports the GoI to put in place improved systems, processes and procedures focusing on specific issues within its results areas towards achieving very specific high-level End of Facility Objectives (EOFOs) to which all its activities and projects contribute to.’ One of the projects under the programme is called: ‘Innovations for Service Delivery and Economic Empowerments’. I once read their ToC without becoming any wiser as to what the programme is actually about.”

Random scattering of portentous (but vacuous) words and jargon inflation

This from Poyrot: ‘…the aim being to purposefully valorize the land with strategic efficiency as a means of providing a sustainably effective solution to..’

While Rick Davies dug out his excellent 2006 post on jargon inflation

While Rick Davies dug out his excellent 2006 post on jargon inflation

Metaphors: Overload or just plain worrying

From Anon:

“’The field of impact measurement in itself is undergoing a period of dramatic change, as others grapple with similar questions—how do we become astronomers of systems change able to study and understand far away movements and bodies that have a direct effect on what is near to us?; when we let go of the role of puppet master of change, how do we measure our contributions as servants of broader change processes, powerful as catalysts, yet humble in our awareness that it takes more than a village to change societies?’ – metaphor overload alert (astronomy, puppets, servants and villages)”

“‘We were very much ‘building the plane while flying it’ as we reimagined our planning process this year’ – understandable metaphor, until you really think through the implications of getting an unbuilt plane off the ground, or being in one!”

To which I would add a personal dislike from the transparency mafia: ‘sunlight is the best disinfectant’. Really? Definitely going to avoid any hospital that believes that……

But aid types cannot even get close to academics (or management consultants)

Alice Evans ‘sees your aidspeak and raises you academia’:

‘Someone with a PhD once read my paper and replied: “Is change ‘caused’ at the level of ideas or agents? You say interests are not a priori but then claim they are shaped by material circumstances? If it’s about ideas then is the relationship to agents dialectical or co-constituted? If it’s about material interests then where do our ideas about them come from?… I guess a simpler way to phrase the question is whether you think ontology is a priori to epistemology?’

And management consultants can give them a good run for their money. This from Rasmus:

‘Here is Maxwell Stamp’s attempt to describe ‘what we do':

‘Flexibility is essential to success, so we are always accommodating and responsive. But without ever allowing ourselves to compromise the integrity of the services we provide. All those services are customised, not commoditised, and include: Each of those sectors has a number of subsectors, each with its own disciplines and expertise. But even that is by no means the totality of the areas in which we have delivered impressive results. Because we rely on our grey cells rather than on black box solutions. So our skills are  readily transferable.’’

readily transferable.’’

How strong is the defence for Jargon?

Then of course there’s just plain nausea-inducing violence to the language of Shakespeare as in this from Shadrock:

“We verbalized a plan to chair a listening session and then share the contours of that back with leadership.”

Those responsible for these atrocities should check out (and maybe memorize) George Orwell’s 6 rules for writing good English.

Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

Never use a long word where a short one will do.

If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

Never use the passive where you can use the active.

Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

Break any of these rules sooner than say anything barbarous.

IDS’ Emilie Wilson did mount a slightly half-hearted defence of jargon. In response to a blogpost entitled 17 Development Cliches I’ll be Avoiding in 2017, she pointed out that what looks like jargon can be‘a handy short-cut behind which sits stacks of research, complicated concepts, collaborative (and frequently painful) deliberations….. (try describing “empowerment” in a tweet rather than just using #empowerment)’.

But perhaps the most disturbing observation came from Binagwaho Gakunju: ‘Do we use aidspeak so much that we don’t even hear it anymore, like smokers and cigarette smell?’

And sure enough, quite a few of my own pet phrases made an appearance: Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation; convening and brokering; space.’ Ouch.

Thanks everyone. Keep ‘em coming and hope Alice follows through with the idea of setting up a website for choice Academic nonsense.

July 26, 2017

What do you do, when you don’t know what to do? Careers advice for the confused.

A colleague was recently waxing eloquent about George Monbiot’s advice to aspiring journalists (he gets so many enquiries that he’s  written it up). It’s nicely written, as you’d expect, and basically urges young would-be Georges to follow their stars rather than money or security. Don’t go and do something you hate (eg write press releases for some pointless PR firm or fluff pieces for a local paper) in order to be able to one day do something you love – you’ll be sucked in, ground down and lose your way: ‘whenever you are faced with a choice between liberty and security, choose liberty’.

written it up). It’s nicely written, as you’d expect, and basically urges young would-be Georges to follow their stars rather than money or security. Don’t go and do something you hate (eg write press releases for some pointless PR firm or fluff pieces for a local paper) in order to be able to one day do something you love – you’ll be sucked in, ground down and lose your way: ‘whenever you are faced with a choice between liberty and security, choose liberty’.

As for what you should do with that liberty, George suggests three approaches:

‘The first is to start how you mean to go on. This is unlikely, for a while, to be self-financing, so you may need to supplement it with work which raises sufficient money to keep you alive but doesn’t demand too much mental energy. If you want to write about the Zapatistas in Mexico, earn the money required to get you out there and start covering them. Be prepared to live and travel as cheaply as possible: In seven years working in the poor world, I managed to keep my expenses down to £3000 a year.

Work hard, but don’t rush. Build up your reputation slowly and steadily. And specialisation, for all they tell you at journalism school, is, if you use it intelligently, not the trap but the key to escaping from the trap. You can become the person editors think of when they need someone to cover a particular issue from a particular angle (that is to say, your angle). They then respond to your worldview, rather than you having to respond to theirs.

Work hard, but don’t rush. Build up your reputation slowly and steadily. And specialisation, for all they tell you at journalism school, is, if you use it intelligently, not the trap but the key to escaping from the trap. You can become the person editors think of when they need someone to cover a particular issue from a particular angle (that is to say, your angle). They then respond to your worldview, rather than you having to respond to theirs.

The second possible approach is this: if the market for the kind of work you want to do looks, at first, impenetrable, then engage in the issue by different means. If you want to write about homelessness, for example (one of the great undercovered issues of developed societies), it might be easier to find work with a group trying to assist the homeless. Learn the trade by learning the issues, and gradually branch into journalism.

The third approach is tougher, but just as valid. It is followed by people who have recognised the limitations of any form of engagement with mainstream employers, and who have created their own outlets for their work. Most countries have a number of small alternative papers and broadcasters, run voluntarily by people making their living by other means: part time jobs, grants or social security. These are, on the whole, people of tremendous courage and determination, who have placed their beliefs ahead of their comforts.’

But there’s a group of people who George rather ignores, which includes the younger me. Sure, his advice is good, uplifting stuff, and

An alternative (and probably stupid) view – skip the passion, maybe it will come along later

can easily be adapted for those young people who ask me about how to find a job in the aid business, or in activist NGOs. Even if some of them are faking it, they seem awesomely clear about their aims. ‘I want to be/do X, how do I achieve it?’ But I find their determination and self confidence rather intimidating, and feel a bit of a fraud at being consulted, because at their age, I had no idea what I wanted to do. What about those people?

I left college with a physics degree that (though it was fun to acquire) seemed entirely irrelevant to my life and floundered about for years. So what advice might be useful if, like the younger me, you are much clearer on what you want to avoid than what you really want to do with your life?

My approach (I now realize) was to respond to that lack of direction by putting myself in a series of difficult situations that forced me to learn and experience new worlds and ideas, in the hope of finding some path that made sense: two years wandering around Latin America; squatting in London; teaching English to refugees; fund-raising for Central American human rights and solidarity groups;  freelance journalism. None of these were easy; I wasn’t particularly good at any of them and none of them were well paid, but out of this slightly masochistic path, some clarity gradually (and painfully) emerged: I loved writing; I was (broadly) on the left; I wanted to understand social and political change and if possible contribute to it.

freelance journalism. None of these were easy; I wasn’t particularly good at any of them and none of them were well paid, but out of this slightly masochistic path, some clarity gradually (and painfully) emerged: I loved writing; I was (broadly) on the left; I wanted to understand social and political change and if possible contribute to it.

I was lucky – the jobs arrived, and over time, became more consistent with my emerging identity. There were a couple of moments when I might have gone off the rails. At one point, I was offered a job writing for a deadly dull business newsletter on international trade finance. The money was good, I was feeling a bit lost at the time and so was tempted, and I could well have then found the salary bump irreversible (something George talks about a lot in his piece). But my then girlfriend (now wife) said she would dump me if I took the job, so I ignored the offer. Thanks Cathy.

Any other answers to the question ‘what do you do, when you don’t know what to do?’

July 25, 2017

Research into Use: how can Climate Change Researchers have more Impact?

Following on the recent kerfuffle about ‘research impact’ (see original and follow up posts), I spent some time chatting to climate

Namibia

researchers in Cape Town about ‘research into use’ (RiU, basically the same thing). The researchers are part of ASSAR, a consortium (of which Oxfam is a member) working across Africa and India with a big focus (30% of its project weighting) on RiU.

Feel free to consult the consortium’s guidance note on RiU and a more detailed learning guide, but this post is about the topics that came up in the conversation, where the practical application of these issues added at least three new angles on the research impact question.

Timing: there’s a very poor fit between the timing of research and that of RiU. If you’re lucky, you may get funds for five years for a new and innovative project like ASSAR, but it takes 1-2 years to really sort out how you are going to approach the research, and then another couple to start getting the findings coming through. Then the last year is a blizzard of papers, briefing notes, conferences etc etc. Then silence – the funding runs out.

Now look at how impact works. Typically, the papers need to be written and published, so that puts you towards the end of the project. Much more likely is that they will find their way to the right desks after the programme is finished. Either because that’s how long it takes people like me to wade through our reading piles, or because research uptake must often wait until particular events (climate shocks, changes of political leadership) create the demand for all this supply.

What to do to try and bring the funding and the impact more into alignment? Fund for 10 years not five? Leave some money in an account after the project ends to finance some kind of sleeper cell that can leap into action when such moment arrive, rehashing the research and getting it to the newly attentive decision makers? Any other ideas?

What to do to try and bring the funding and the impact more into alignment? Fund for 10 years not five? Leave some money in an account after the project ends to finance some kind of sleeper cell that can leap into action when such moment arrive, rehashing the research and getting it to the newly attentive decision makers? Any other ideas?

Relationships: Impact is about relationships more than paper. Decision makers want to be able to pick up the phone and ask advice of experts who they have learned to trust, not be told to read the latest impenetrable academic papers. Researchers that have these networks are invaluable. Sometimes it’s because they’re old – an established track record + grateful former students form an enormous intellectual asset for ageing academics. Or because they are already well connected, often through family connections that saw them as teenagers sitting round the kitchen table with the country’s future leaders (think the Miliband brothers). One ASSAR researcher, Margaret Angula has just such a network in Namibia, and it massively increases the chances of RiU.

But can we redesign research programmes to recognize the importance of relationships? Should applicants for research posts submit their phone directories to a social network analysis (hiring for membership of Old Boys/Girls Networks is not very egalitarian….)? Should research programmes deliberately push older, more networked researchers into outreach rather than publishing (and would they agree to do so)? Or how about a mentoring system where the older researchers are twinned with a young rising star, take them around and introduce them, then step back and let them take over some of their network ‘accounts’? I’d love to hear of some examples of this.

Because what doesn’t work, I fear, is trying to force un-networked, unconfident young researchers to become glad-handing social  butterflies. How can we get better at ‘going where the energy is’, identifying and supporting those researchers who really want to do this stuff?

butterflies. How can we get better at ‘going where the energy is’, identifying and supporting those researchers who really want to do this stuff?

Comms: The ‘go where the energy is’ mantra applies at least as much to the more public aspects of RiU. Cautious academics petrified of prematurely revealing their findings (someone might nick them!), making a mistake or looking stupid are unlikely to take to blogging or radio interviews. Instead, find the ones who like writing and communicating and back them. Which includes incentives: how can researchers (young or old) be sufficiently rewarded (professionally as well as morally) for the time and energy put into ensuring impact?

The alternative is to separate the comms and research functions – lots of academic institutions and thinktanks have comms teams, but here too, there are serious drawbacks. Journalists often want to hear from the researcher not the spin doctor (organ grinders; monkeys) and can get irritated if their questions are met with a series of ‘let me find out and get back to you’ responses. An alternative to the alternative is to work with hybrid ‘knowledge brokers’ who are sufficiently across the issues to digest and translate what is out there, linking supply with demand (i.e. find out the needs, then harvest the pertinent research, translate it and provide it). But it’s very hard to get comms people who can do it all – come up with crazy, out of the box ways of communicating, be deeply immersed in research methodologies and findings, and be deeply immersed in the policy or other system the research is supposed to be influencing. Easier to locate such skills across a team than within one superhuman individual, I guess.

Thoughts?

And here’s ASSAR’s take on Research into Use

July 24, 2017

The 8 rules of Corporate Bullsh*t: now for the aidspeak version

I recently tweeted a link to a truly wonderful piece by the FT’s Lucy Kellaway, How I lost my 25-year battle against corporate claptrap, and a couple of people demanded an aidspeak version. Where better to turn than the FP2P hivemind?

and a couple of people demanded an aidspeak version. Where better to turn than the FP2P hivemind?

Her 8 rules are:

Never use a short word when a long one will do

Everyday euphemisms are the way forward

Disregard the grammar you learnt at school

There is no such thing as too much emotion

If you produce something simple, rebrand it so no one will know what it is

Do not limit yourself to words that are in the dictionary

There is no such thing as too much metaphor and cliché in one sentence

Ignore Rule 1 (use short, well-known words, but the catch is you use them to mean something different. The word of the moment is “play”.)

Recognize any of these? Yup, me too (especially rule 5). So it’s time for a spot of crowdsourcing: what are your top candidates for an aidspeak collection of all-time worst claptrap?

But be warned, corporates set the bar very very high. Here are the three all time winners (in reverse order) from Lucy’s doomed 25 year crusade against corporate BS:

‘Bronze goes to Rob Stone, co-CEO of advertising agency Cornerstone, for heroically mixing cliché, metaphor and hot air to say nothing: “As brands build out a world footprint, they look for the no-holds-barred global POV that’s always been part of our wheelhouse.”

![dilbert-bingo[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1501026892i/23409898.gif) Silver belongs to Angela Ahrendts who, in a Burberry annual report, wrote the most mysterious sentence ever composed in the English language: “In the wholesale channel, Burberry exited doors not aligned with brand status and invested in presentation through both enhanced assortments and dedicated, customised real estate in key doors.” I have showed it to many business experts over the years, but no one has ever been able to say what it means or explain why a raincoat maker could be talking so intently about doors.

Silver belongs to Angela Ahrendts who, in a Burberry annual report, wrote the most mysterious sentence ever composed in the English language: “In the wholesale channel, Burberry exited doors not aligned with brand status and invested in presentation through both enhanced assortments and dedicated, customised real estate in key doors.” I have showed it to many business experts over the years, but no one has ever been able to say what it means or explain why a raincoat maker could be talking so intently about doors.

The runaway winner and deserved gold medallist is John Chambers who, while CEO of Cisco, fired off an email to underlings beginning “Team”, and ending: “We’ll wake the world up and move the planet a little closer to the future.”

He has used plain words and simple syntax to produce the most terrifying piece of bullshit ever.’

So, the gauntlet has been thrown down: send me your worst examples of aid industry BS, and if they are good enough, I will publish them in collected form. And yes, submissions from FP2P are eligible……

July 23, 2017

Links I Liked

POTUS continues to keep social media interesting, if alarming. ‘The World is an Angry Place’: Ben Phillips reckons there should be an  app to watch all Trump interviews like this. While the Economist points out that the Trump White House has no pets for the first time since Johnson. But check out the others (hippos, alligators etc)

app to watch all Trump interviews like this. While the Economist points out that the Trump White House has no pets for the first time since Johnson. But check out the others (hippos, alligators etc)

Couple of good pieces on China in Africa:

New paper summarizing what we know about Chinese investment on the continent

Hannah Ryder asks what research tells us about how Africa can get the best out of the relationship

Economist chart of UK migrant kids’ exam results, showing a huge spread between language groups compared to the national average

The Kabila Family Business. Expose of the DRC President’s 80 companies, including contracts with the World Bank, UN etc h/t Joshua Williams

Five TED Talks that inspired the World Bank President Jim Yong Kim (on remittances, hunger, poverty, private sector, inequality)

The RSA has boiled down the discussion on power and systems in my standard How Change Happens presentation to just 6 minutes.

July 20, 2017

The Unvarnished Project Cycle

This is genius from Lisa McNally – feel free to suggest further improvements

And I guess this is the exec sum, although it’s actually a very optimistic version, in that ‘what happened’ ends up roughly in the same place as the planned version, in the top right quadrant (there’s three others available…..)

Anyway, they’re both brilliant. Have a good weekend.

Anyway, they’re both brilliant. Have a good weekend.

July 19, 2017

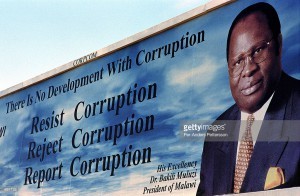

How can the Anti-Corruption Movement sharpen up its act?

Spent a day earlier this

Surprisingly Enjoyable

week in a posh, but anonymous (Chatham House Rule) Central London location, discussing the state of the global anti-corruption movement with some of its leaders. The meeting took place in a posh, very high ceilinged room, under the stern gaze of giant portraits of assorted kings, aristos and philosophers. I wondered what they would have made of the assembled academics and aid practitioners being subjected to goldfish bowl methodologies and other participatory tricks of the trade. Actually, I came away convinced that goldfish bowls are great for such ‘expert groups’ (as usual, everyone seemed to know what they were talking about except me), combining a real conversation between a small group of people with the assurance that everyone who wants to will get a chance to speak, and a non-confrontational way of getting rid of people that drone on with a simple tap on the shoulder (if only it was always that easy).

The starting point for the meeting was pretty gloomy – 25 years or so of anti-corruption work have produced many recipes, but not much in the way of a square meal. Not only that, but some places we thought were clean have now slipped into reverse. As usual when faced with a ‘why change doesn’t happen’ problem, I reached for the 3is: ideas, interests and institutions.

Ideas

Banging on about corruption may appease the Daily Mail, but otherwise the framing is pretty disastrous. It is easily couched in highly moral terms that allow advocates to ignore issues of power and politics, because they think they have found an absolute right/wrong issue. It’s ridiculously broad, covering everything from using a connection to get your kid an internship, to the pillaging of entire nations by kleptocrats, so not surprisingly, it doesn’t translate well, with a fair amount of disagreement at the margins (does lobbying = corruption? Or sending your kid to private school? Or paying a bribe so your business can actually function, employ people etc?). Then there are the endless medical metaphors, such as corruption = cancer, which encourage politicians and aid bosses to demand single, universal ‘cures’.

Interests

I was reminded of Chris Cramer’s great book ‘Civil War is not a Stupid Thing’. Corruption is not necessarily an evil thing. For example it can act as a political stabiliser in weak governance systems, eg buying off the warring parties to ensure the success of a peace agreement.

I was reminded of Chris Cramer’s great book ‘Civil War is not a Stupid Thing’. Corruption is not necessarily an evil thing. For example it can act as a political stabiliser in weak governance systems, eg buying off the warring parties to ensure the success of a peace agreement.

But even when it is an evil thing, the aid business is poorly placed to tackle it, because so much official aid goes through governments, which often include precisely those who profit personally from corruption and/or whose political survival depends on corrupt proceeds to meet expectations of political patronage (tin roofs, school fees, a contribution to a celebration etc). Turkeys; Christmas.

Institutions

Aid institutions seem terribly unsuited to work on anti-corruption. As mentioned, they are over-reliant on national governments as partners of choice. They are outsiders, easy to denounce as enemies of the nation if they do start to threaten corrupt interests. Their short time scales are a serious obstacle when many successful transitions take decades rather than years. And the results agenda is problematic when many successes are actually side effects – historically most countries that have reduced corruption have done so as an unintended consequence of making other things work better.

So what?

Some in the room challenged the negative starting point, pointing to progress in areas such as the arms trade or extractives. Other factors may be contributing to the negativity – the gloomy cloud hanging over US and UK liberals makes them see the whole world in darker terms, and perhaps the greater levels of reported corruption are a sign of better reporting rather than more corruption. Lots of ex-presidents in Latin America are currently being prosecuted for corruption – does that mean things are getting worse or better?

But overall I came away from the day feeling that the anti-corruption movement is a bit stuck and really does need to rethink. One

But it’s not actually true…..

option would be to stop using the ‘C’ word altogether because it’s such a terrible starting point. Another, perhaps more realistic, approach would be to piggy back on the progress made in the related areas of governance and institutional reform – it feels like the anti-corruption movement is in dire need of a greater injection of ideas from the ‘Doing Development Differently’ and ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ coalitions, e.g. on ‘working with the grain’ or ‘politically smart; locally led’ programming. I had thought this discussion was already well advanced, but am now not so sure.

My own suggestions would be:

Get more serious about a bottom up approach. There are better ways to understand what corruption means to poor people than the occasional public opinion survey. What could we learn from governance diaries about how poor communities experience and deal with corruption? How could we combine that with the more analytical approach that captures the higher levels of corruption that damage entire economies and polities, but that may not always make it onto poor communities’ radar?

Positive deviance: identify any bits of the state (ministries, provinces, city administrations) that appear as positive outliers with low corruption/good governance. What can be learned from them and spread to other areas? (see the Islands of Integrity project)

Think much harder about anti-corruption work in fragile states. Is it even worth pursuing? If so, it probably needs a different approach, with broader coalitions of players filling in the holes where the state should be, such as faith organizations, traditional leaders and CSOs.

Let’s see corruption specialists working with those trying to crack real world problems – like bad roads, or poor quality health and education services – rather than sitting with other anti-corruption experts talking about corruption and so risking being pulled into generic and abstract debates about indicators. Corruption is a part of many big problems in development, but it is rarely the only part.

But overall, I have to say my conclusion was that the sooner aid gets out of the anti-corruption business, and local politics takes over, the better.

Thoughts?

July 18, 2017

The Case for a ‘Slow and Steady’ Approach to Capacity Building

In response to Lisa Denney’s piece last week on the

low quality of much capacity building

work in the aid biz,

In response to Lisa Denney’s piece last week on the

low quality of much capacity building

work in the aid biz,  several people got in touch to say ‘but we do it better’. Here’s one example – a guest post from

Arjan de Haan

and

Olivia Tran

, from one of my favourite organizations, IDRC (see rave review of some of their

previous work on evidence → policy

)

several people got in touch to say ‘but we do it better’. Here’s one example – a guest post from

Arjan de Haan

and

Olivia Tran

, from one of my favourite organizations, IDRC (see rave review of some of their

previous work on evidence → policy

)

Lisa Denney in her recent guest post on the pitfalls of ‘capacity building’ in the aid industry, pointed out the narrowness of capacity development approaches that equate technical training to building capacity, neglect the influence of power and politics, and ignore non-Western notions of what capacity means. “But perhaps most fundamentally,” Lisa writes, “and what all these factors derive from, is the fact that the aid industry turns fundamentally political processes of social and institutional change into projects.” And she is right. Most development projects last no longer than five years and focus on “quantifiable” results. Although no one would argue that measurable results aren’t important, often meaningful impact manifests itself much later.

Most, but not all. The International Development Research Centre (IDRC) supports researchers and research institutions, mostly based in the Global South, that have the potential to contribute poverty reduction. We do this through a policy lens, with the goal of creating policy evidence and impact. Capacity building is IDRC’s core business, but we have different approach, investing in capacity building projects for much longer periods of time.

Most, but not all. The International Development Research Centre (IDRC) supports researchers and research institutions, mostly based in the Global South, that have the potential to contribute poverty reduction. We do this through a policy lens, with the goal of creating policy evidence and impact. Capacity building is IDRC’s core business, but we have different approach, investing in capacity building projects for much longer periods of time.

When IDRC promoted the establishment of the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) almost 30 years ago, there was a severe shortage of well-trained, locally based economists to inform policy making in the continent. In the late 1980s, the IDRC and its African partners made a concerted effort to transform the AERC from a network of economists into an institution with the explicit aim of bridging the gap between researchers and policy makers. We then helped found its sister program, Programme de Troisième Cycle Interuniversitaire en Economie (PTCI), 23 years ago to address the same issue in Francophone Africa. With the support of the World Bank/the African Capacity Building Foundation, the African Development Bank, various national development agencies, and other donors throughout the years, these capacity building programs are still running, over two decades later and quietly achieving  remarkable success.

remarkable success.

Together, AERC and PTCI have mentored more than 5,500 African researchers from 43 countries across the continent. The programs have since become recognized as regional centers of excellence, training burgeoning economists. The vast majority of graduates of the programs remain in the region, instead of moving abroad and contributing to ‘brain drain’. AERC and PTCI graduates have come to hold high-level bureaucratic, academic, and institutional roles in many countries: as national advisors, secretary generals, and university deans. They have created a skilled network of over a thousand economists who are informing sound evidence-based policy and decision making in Africa – reducing the need to rely on foreign experts.

Another example is the Partnership for Economic Policy (PEP). Now a legally incorporated global organization based in Kenya, Nairobi, PEP was created by IDRC in 2002 as an international network of researchers and institutions, and provides the training and mentoring to promising developing country analysts. Over 800 researchers have benefited from the PEP program globally, 46% of which are women.

PEP-supported researchers are enabled to publish in the top international scientific journals, leveling the playing field with their northern counterparts. They also gain considerable exposure at the national level – either as direct policy advisors or through the media. In Nigeria, for example, PEP researchers contributed to the development of Nigeria’s first national social security scheme. The PEP network also created its own cohort of mentors and trainers. These are increasingly based in the global South, thus avoiding the trap of constant training by foreign experts mentioned in Lisa’s post. Organisations like PEP, AERC and PTCI enhance opportunities and networks for future leaders in research and policy.

PEP-supported researchers are enabled to publish in the top international scientific journals, leveling the playing field with their northern counterparts. They also gain considerable exposure at the national level – either as direct policy advisors or through the media. In Nigeria, for example, PEP researchers contributed to the development of Nigeria’s first national social security scheme. The PEP network also created its own cohort of mentors and trainers. These are increasingly based in the global South, thus avoiding the trap of constant training by foreign experts mentioned in Lisa’s post. Organisations like PEP, AERC and PTCI enhance opportunities and networks for future leaders in research and policy.

But challenges that Lisa Denney and the report on state capacity describe are relevant for this approach too. We find that it is more difficult to program in fragile and post-conflict states, yet it is in these countries that support may be most needed. To address this gap, AERC has designed a research and training program focused on building leaders in economic management particularly in fragile and post-conflict countries. PEP has set and exceeded its target of having 40% of its projects in low-income, fragile and post-conflict countries.

PEP, AERC, and PTCI have taken decades to foster and build trusting relationships. Even so, these programs are finding it difficult to secure and diversify funding. PTCI in particular has struggled to find new funders. Despite the benefits of such capacity building programs, their sustainability without the support of organisations like IDRC remains in question.

According to recent surveys by the organisation, 34% of PEP projects’ findings have had a direct influence on “strategic development  policy decisions.” But measuring impact on policy is an art not a science. It remains difficult to capture the significance of the training programs. We realise there is a clear need to improve the metrics of success of such capacity building programs, and improve the narratives about the intangible benefits that those networks provide.

policy decisions.” But measuring impact on policy is an art not a science. It remains difficult to capture the significance of the training programs. We realise there is a clear need to improve the metrics of success of such capacity building programs, and improve the narratives about the intangible benefits that those networks provide.

Of course, research capacity building alone will not resolve development issues. But the programs are making a lasting impact on the capacity of Southern researchers to conduct research, meeting international standards and gradually reducing dependency, and use their findings to inform local policies for more inclusive and equitable development. We believe they show there is still a case to be made for a slow and steady capacity building approach that allows Southern experts to achieve their own development innovations.

Arjan de Haan is the Employment and Growth Program Lead at IDRC. He has over a decade of experience working at the Department for International Development (DFID) and at universities in the UK and the Netherlands.

Olivia Tran is a Master’s Candidate at the School of International Development and Global Studies at the University of Ottawa, Canada. She has worked in Mongolia and Thailand, and is currently a summer student at IDRC.

July 17, 2017

Can a new Index measure whether governments are serious about reducing inequality?

Oxfam’s inequality ubergeek, Deborah Hardoon, needs your help with an ambitious new index

As a researcher working on inequality, there are plenty of data and statistics for me to analyse, model and generate ‘killer stats’ from. Of course, there are many data gaps, plus lots of debate on which measures are the best to use (hint, not the one proposed for SDG10). But for the most part economic inequality is recognised as something that is quantifiable and which we have used to underpin our understanding of the issue and have highlighted in our campaign materials to powerful effect.

But at Oxfam we don’t just want to understand the way things are, we want to change them – to stop extreme and rising inequality getting in the way of our fight against poverty and injustice.

We know that inequality is not inevitable. The differences in the levels of inequality and how it manifests in a country or community demonstrate that activities and institutions can change the way that income and wealth are distributed. Government policy that deliberately affects how countries, their budgets, their companies and their people work necessarily has an impact on the economic distribution.

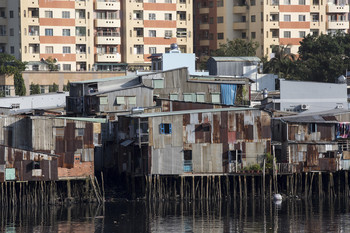

A father holds his daughter as he stands on a site from which local residents have recently been evicted to make way for new developments, close to luxury apartments in North Jakarta, Indonesia. Credit: Tiara Audina / Oxfam Feb 2017

So can we measure that intent – whether governments are really making an effort to tackle inequality? It’s a tantalising question, and we’re having a go. We decided to start with some of the most obvious policies that affect the economic distribution, as discussed in the report that launched our inequality campaign, namely spending, tax and labour market policies. In order to raise awareness of the importance of these policy tools and to put pressure on governments to step up their efforts to reduce inequality through these policies, we have embarked on a project to try to quantify policies, so that we can measure, compare and contrast governments’ commitment to reducing inequality.

Our partner in this project, Development Finance International, gave us a head start. Their years’ of expertise in gathering and analysing data on government spending meant that we had data on spending on education, health and social protection – spending which has a powerful impact on reducing inequality – for more than 150 countries. They had also already conducted an extensive data gathering exercise to collect data on Personal Income Tax (PIT), Corporate Income Tax (CIT), and VAT rates and revenues for a wide range of countries.

The extent to which spending on any given sector will reducing inequality of course depends on how the money is spent within each sector. Similarly the extent to which different taxes redistribute income varies depending on the structure of the taxes and who pays what. The Commitment to Equity institute works on exactly these issues – identifying the actual extent to which spending and tax policies reduce the level of inequality in different countries. CEQ generously gave us access to this data. And so the database began to grow…

So 7,000 data points later, we have aggregated all this information into an Index which scores and ranks 152 countries on their commitment to reducing inequality. The Index is in what data nerds call a beta form – a version we are encouraging people to read and comment on, to help us improve it. We find that over nearly three quarters of countries are doing less than half of what the best performing countries are do showing there is clear room for improvement. This version finds that higher income countries tend to do better than lower income countries, but that this is not necessarily so, with Niger doing better than Korea for example. One in four of the top fifty are low or middle income countries. There is also major variation between countries, with some like Namibia doing many things to successfully bring down their high levels of inequality, whereas others like Nigeria are doing shamefully little. Individual countries also score very well on specific indicators, if not overall- Ethiopia spends one of the highest percentages of its budget in the world on education for example.

So 7,000 data points later, we have aggregated all this information into an Index which scores and ranks 152 countries on their commitment to reducing inequality. The Index is in what data nerds call a beta form – a version we are encouraging people to read and comment on, to help us improve it. We find that over nearly three quarters of countries are doing less than half of what the best performing countries are do showing there is clear room for improvement. This version finds that higher income countries tend to do better than lower income countries, but that this is not necessarily so, with Niger doing better than Korea for example. One in four of the top fifty are low or middle income countries. There is also major variation between countries, with some like Namibia doing many things to successfully bring down their high levels of inequality, whereas others like Nigeria are doing shamefully little. Individual countries also score very well on specific indicators, if not overall- Ethiopia spends one of the highest percentages of its budget in the world on education for example.

It’s been a fascinating project to be a part of. Some epic data gathering, iterative adaptation of formulas to reduce complex policies (like PIT with varying rates and thresholds) down to a single comparable indicator, working with Oxfam country offices to understand national data better and getting the whole thing tested by the experts at COIN, the EC’s special unit for composite indicators.

The results are intriguing. Whilst it’s not particularly surprising that Sweden is top and Nigeria bottom, Namibia’s relatively high score revealed the recent commitments the government has been making to address the high level of inequality. And a global average CIT rate of 25% certainly puts President Trump’s proposal to reduce CIT in the US to 15% into perspective. Dig into the data and see what you find…

But at DFI and Oxfam, we’re not done yet…

We’re hoping that this stirs the debate and conversation about what governments can do with the policy tools

High rise flats and poor housing along the Saigon River in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Credit: Eleanor Farmer/Oxfam Dec 2016

available to them to reduce inequality. We also hope this debate will in turn help us strengthen the Index and the way in which we measure policies, so that the Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index can have maximum effect as a powerful annual advocacy tool as we look to start work on the next edition.

So I encourage you to take a look at the data, the report and methodology document, which goes into more detail on all the indicators we used and the rationale and data sources behind them. We’re keen to hear from you and get your thoughts on the Index. So here are some questions to you…

This project was always a balance between what, ideally, we would like to measure based on our understanding of inequality and inequality fighting policies and all the conditions and contextual factors that matter, and what pragmatically can be quantified and compared across more than 150 countries in a way that we can explain clearly. Have we got the balance right?

There are many policies that can have an important impact on inequality that are not captured in our Index. Some of these we think should be quantifiable and therefore good contenders to be included in the Index (like wealth taxes), some policies and their impact will be less straightforward to measure. Are we missing something vital that we should seek to include in future editions?

The data nerd in me is a big fan of seeing the database as the product, allowing the reader to explore the detail behind each indicator. This detail is lost with a league table which aggregates and simplifies diverse policies issues into a single score and rank. But an Index makes complex ideas accessible and generates attention. On the Dashboard vs Index debate, where do you sit?

Take the 5 min survey and tell us what you think

July 16, 2017

Links I Liked

Off to Cape Town this week, giving talks on Thursday lunchtime at the Isivivana Centre in Khayelitsha; Friday lunchtime at the GSDPP in Rondebosch and Friday evening at the Sustainability Institute in Stellenbosch.

Off to Cape Town this week, giving talks on Thursday lunchtime at the Isivivana Centre in Khayelitsha; Friday lunchtime at the GSDPP in Rondebosch and Friday evening at the Sustainability Institute in Stellenbosch.

The Hamburg G20 riots: That feeling when you’re overthrowing capitalism but just can’t resist taking a selfie on your iPhone 7 (plus vanity beats security, every time – where’s your hood, dude?) h/t Jimmy Rushmore. The G20 also produced one of the great mansplaining eyerolls – take a bow, Angela Merkel (but not Vladimir Putin)

The Guardian kicked off a two year campaign on one of the world’s biggest killers – tobacco (6m deaths a year – 15 malarias), and Reuters got in on the act with a great investigation into the lobbying activities of Philip Morris. About time. Now can the NGOs to step up?

And you thought The Handmaid’s Tale was fiction. Women in Arkansas now require a man’s permission to get an abortion.

“The man China couldn’t erase” – 1m BBC video on the life of Nobel laureate and human rights advocate Liu Xiaobo

There’s Value for Money, and then there’s Institutional Incentives. Dilbert on what really drives decisions

There’s Value for Money, and then there’s Institutional Incentives. Dilbert on what really drives decisions

UK to spend aid money on insurance against disasters in Africa. Interesting initiative. Another win for CGD?

Unless you were already familiar with the original Pen-Pineapple-Apple-Pen viral video, which I wasn’t, this take on the SDGs was completely baffling. Hats off to whoever in Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided to turn PPAP into Public Private Action for Partnership – brilliant!. Tell me when UN adopts it as the official video.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers