Duncan Green's Blog, page 105

December 10, 2017

Links I Liked

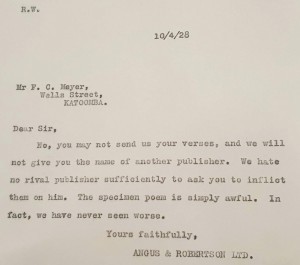

All other rejection letters can step down. We have a winner.

All other rejection letters can step down. We have a winner.

Summary of IMF findings on global inequalities: countries with the most health coverage suffer from a lower average life expectancy. Sub Saharan Africa would accrue largest gains by reducing disparities in health coverage.

Beware Public Private Partnerships. Good overview from UN’s Jomo Kwame Sundaram

What to do about the rising tide of hate: ‘The opposite of Othering is not “saming”, it is belonging.’

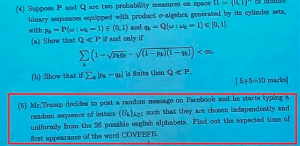

Today’s exam at the Indian Statistical Institute. See Question 5 (click to expand). [h/t Grieve Chelwa]

Today’s exam at the Indian Statistical Institute. See Question 5 (click to expand). [h/t Grieve Chelwa]

How to reconnect with the public on aid

Brilliant and moving from Ben Ramalingam. The memories evoked of his Sri Lankan childhood by War Child’s batman video

And here’s the video that got to him, which just won the Golden Radiator Award 2017 for best aid ad

December 7, 2017

Why the disconnect between Aid and Buddhism in Myanmar?

Back from Myanmar today, and still processing an intense week of conversations. Here’s a first instalment. A week in, I was struck by the gulf between the aid bubble and the deep religiosity of people throughout the country. So I dashed off this vlog on a weekend visit to the spectacular Shwedagon Pagoda, in the heart of Yangon.

In it I make a few points:

Buddhism doesn’t sit easily with the aid industry: Buddhism urges modesty, whereas aid organizations have to blow their own trumpets if they want funding or profile; Buddhism sees true donations as those which come without accompanying questions – try selling that idea to the average aid donor.

We talk increasingly about norms, but religions are the ultimate norm shapers (for good or ill). If we’re serious we should be investing far more in understanding how they go about that task.

Religions are money magnets. In a few years’ time, at current rates of growth, Myanmar is likely to graduate out of low income status, and aid flows are likely to decline sharply. Local civil society organizations that remain aid dependent (as many currently are) face a grim future. Those that can tap into non-aid sources such as religious giving, domestic altruism, migrant remittances, or social enterprises, may be able to survive. I heard very little to suggest that current aid donors are doing much to help that process, but without preparation, it could become a nasty cliff edge for a lot of excellent social activism.

More generally, research almost invariably shows that poor people trust faith organizations more than they trust the state, civil society or anyone else. Surely any genuine ‘bottom-up’ approach to development should acknowledge and build on that fact?

Of course, once I showed the video to a few people, it turns out that there is more going on in this area than I  realized, albeit in a few limited areas:

realized, albeit in a few limited areas:

Pyoe Pin, who I was studying as an example of adaptive management, works with a number of interfaith organizations, eg the Myanmar Interfaith Network on HIV or women’s rights. The Baptists are central to the work in Kachin. Then there’s the work on Monastic education. ‘Religion is fundamental to power and change in Myanmar’, according to Pyoe Pin boss Gerry Fox. The Sangha (Buddhist monastic order) and its state supported regulator are extraordinarily powerful players at all levels.

Another (local) PP staffer added that, ‘we don’t take religion as central, but engage with their organizations on particular issues, especially at the local level, where the monks tend to get more involved.’

But even with those caveats, the links between the aid business and faith organizations seem far flimsier than they should be.

Why is that? In part I think the aid business has plenty of secular DNA, built on its origins in orthodox economics, medicine and the provision of stuff (infrastructure, schools, hospitals). Since most aid is provided by governments, they typically see other states as their natural partners, so projects and activity swarm around governments, even when they are weak. By contrast, the aid business finds it hard to work with ‘non-state actors’, which in fragile and conflict-affected places like Myanmar, can be relatively more important than elsewhere. That includes faith organizations, ethnic armed organizations, traditional leaders, but also shadowy, powerful players involved in jade or gold smuggling. It’s a bit like physics concentrating on the visible world, while acknowledging that 96% of the universe is actually made up of mysterious, unknowable ‘dark energy’ and ‘dark matter’. Not very satisfying, is it?

More on Myanmar next week.

December 5, 2017

How Data Analytics can Unlock the Knowledge in Development Organisations

Guest blog by Itai Mutemeri (@tyclimateguy) is Head of Analytics at London based Senca Research

In September 2017, I headed up to the Oxfam head office in Oxford to present our research paper: Big Data Opportunities for Oxfam – Text Analytics. Like all good research titles, it’s a mouthful. The paper explored the potential application of text analytics in response to Oxfam’s call for proposals on how big data tools could aid the organisation. Given that we use text analytics software, daily, it seemed a good fit. I began with a primer on text analytics and why it is useful.

Data lives on a spectrum between structured and unstructured. Structured data is what it sounds like – basically anything you can neatly arrange in a spreadsheet. Unstructured data, is much harder to analyse and comes in the form of social media posts, pictures and archived documents, to name a few.

The general rule of thumb, is that most of the data organisations have access to is unstructured. For example, research indicates that 80% of the data the US government has access to is in unstructured text, more commonly known as normal human language. But unstructured text poses problems for humans and machines alike; for the lowly analyst, the sheer volume of data can be daunting, and for man’s intellectual steed – the computer – the unstructured nature of the text is difficult to decipher. In development, we are making strides toward data-driven decision making, so it makes sense to have tools that will help you analyse more than 20% of your data.

But analysis for its own sake is pointless, so our paper focused on the use of text analytics software to solve the two most prevalent problems we have observed while helping other organisations use their text data.

Problem 1: People don’t tap into the organisation’s collective wisdom. Put simply, we generally start planning projects as if no-one within the organisation has ever worked on something similar. We look outside for useful information and signals, instead of starting from the existing internal knowledge. But we ignore institutional wisdom at our peril – we end up repeating mistakes that would have been easily avoided if we had learnt from the experience of others. I watched a large project fail because of something that we could have known and avoided – it is a crushing feeling.

There are many reasons we don’t use our institutional wisdom. The ODI cites, amongst other factors, an incentives system that rewards staff for new ideas; leading to a neglect of lessons previously learned. I once worked with an organisation whose internal database was so difficult to search that no one ever used it, except to deposit yet more project documents that no one would ever read. Even if they were able to find the relevant documents, reading them all to synthesize the key lessons would be a monumental task. This is especially true in large organisations like Oxfam, which has offices around the world. For this problem, we introduced a text analytics solution that makes it easier to search through internal documents.

There are many reasons we don’t use our institutional wisdom. The ODI cites, amongst other factors, an incentives system that rewards staff for new ideas; leading to a neglect of lessons previously learned. I once worked with an organisation whose internal database was so difficult to search that no one ever used it, except to deposit yet more project documents that no one would ever read. Even if they were able to find the relevant documents, reading them all to synthesize the key lessons would be a monumental task. This is especially true in large organisations like Oxfam, which has offices around the world. For this problem, we introduced a text analytics solution that makes it easier to search through internal documents.

Problem 2: Organisations struggle to study their own behaviour. Put more simply, figuring out what’s working and what isn’t, particularly in large organisations, is extremely challenging. The directors and managers of development organisations should be able to ask (and get answers to) questions like “What is working well across our WASH initiatives?” The answers inform decisions on where resources should be allocated.

Considering the mountain of paperwork our sector produces in the form of proposals, project plans, project completion reports and monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning documents – such data should exist. The problem here, as it often is, is a resource one. Analyzing all these documents would require a team of researchers that most organisations could not afford. One of the outcomes of technology should be to allow us to do more with less. With that in mind, I presented to the Oxfam staff a text analytics powered tool that, with some customization, would allow analysis of a large corpus of documents to get to those answers.

Examples of text analytics in development

Using text analytics to create new knowledge is not limited to the analysis of documents. The UN Global Pulse Lab in Kampala created a toolkit that makes talk radio broadcasts machine-readable through the use of speech recognition technology and translation tools that transform radio content into text. Once the conversation is in text, one can use the tool to explore relevant public conversations on topics of interest, in this case:

Kampala created a toolkit that makes talk radio broadcasts machine-readable through the use of speech recognition technology and translation tools that transform radio content into text. Once the conversation is in text, one can use the tool to explore relevant public conversations on topics of interest, in this case:

Early warning and influx of refugees in Uganda

Recording losses associated with local disasters

Local Governance and public health service delivery

On the first topic, the lab was able to uncover the main topics of conversation related to refugees over the month of analysis; and emerging vulnerabilities related to refugees later in the year.

The goal of the project is to support the Government of Uganda and development partners in incorporating the voices of Ugandan citizens into the development process. With an estimated 7.5 million words spoken on Ugandan radio every day, this kind of analysis would be impossible without text analytics. For those interested in other tools for working with qualititative data in development, I highly recommend this overview.

I concluded the presentation with recommendations on how to choose the right analytics solution:

Focus on the highest value opportunities

This is the best way to get buy-in from all the people whose work you are going to disrupt, because they can see the value of what you are proposing.

Start with questions, not data or solutions

Figure out what the problem or what the question is, then try to assess whether or not you have the data to answer that question, and only then should you pick an appropriate solution.

Figure out what the problem or what the question is, then try to assess whether or not you have the data to answer that question, and only then should you pick an appropriate solution.

Run short, inexpensive experiments

The most important thing is to quickly validate, using the organisation’s own experiments – which solutions can work.

In my opinion, data is a fancy word for history. The more tools we have to study, understand and learn from our history the better.

We would love to hear from other organisations on how they are using data to improve their project work.

December 4, 2017

Vote now for the best/worst charity ads of 2017

Every year, the ‘rusty radiator’ site runs a poll on the year’s best/worst aid agency ads. Let’s start with the good ones.

My favourite has to be War Child’s batman video – very moving

The others are a smart Save the Children US take on children and Christmas gifts, a very knowing Below the Line film on aid stereotypes and a human trafficking film that I can’t find on youtube (please send a link if you have one).

The candidates for the worst ones got me thinking. Two of the videos are appeals from the UK Disasters Emergency Committee (of which Oxfam is a member) about Yemen and East Africa. The Guardian discussed the other candidate – Ed Sheeran’s video for Comic Relief – so I’ll stick to the other two. The award jury’s remarks on the Yemen film are nuanced: ‘Very graphical and stereotypical. Devoid of dignity to those suffering. They’re really bringing back the 80s with this video. This ad shares the same problems as the Africa Famine Appeal by DEC. Context of ‘we’re doing well, you selfish people’. But it offers some context and a bit of detail. Humanitarian crises are difficult though.’

Yes they sure are. I can happily join in the criticism of charities that routinely use ‘poverty porn’ as a way to raise funds for their work all year every year, deny the dignity and agency of people living in poverty, and contribute to an entirely misleading view of what is going on around the world. But is there really no circumstance in which the suffering is so great and the need so immediate that you say ‘OK, we have to show what is going on and try and raise some extra cash to save a few more lives?’ And in order to do that, an organization like the DEC simply can’t start getting into criticising UK or other policy on Yemen (though Oxfam does plenty of that).

So what do you think? Does the Rusty Radiator crew need to nuance its message, or should these kinds of images never be used? I know, let’s have a vote on the vote:

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

Sadly, the Rusty Radiator vote ended yesterday. Winners will be announced on Thursday.

December 3, 2017

Links I Liked

I’m usually no fan of Private Eye, but this is great (click to expand)

Open Access books are downloaded seven times more, cited 50% more, and mentioned online ten times more than non OA.

Thinking Politically is the easy bit. It’s the Working Politically that is almost impossible. Really good summary of lessons from Lavinia Tyrrel & Graham Teskey

Kate Raworth went down a storm to a packed house + overspill room at the LSE recently, launching Doughnut Economics, debating with economist Oriana Bandiera, and putting up with me as chair. The podcast got 14k downloads in the first week.

Check out ‘Beautiful Rising’. Remarkable website for activists with stories, theory, guidelines etc

Great graphic. A person escapes extreme poverty every second, but 8% of world’s population still lives below the poverty line. It needs to go up to 1.5 per sec to the hit first SDG.

This is lovely. Why does activism prefer extroverts (noisy, quick, confrontational)? How can introverts make change happen through slow, quiet activism? Sarah Corbett explains

November 30, 2017

Looking at Adaptive Management in Myanmar – a quick video

I’m in Myanmar for a few days, taking a look at Pyoe Pin, a fascinating project often held up as a good example of Adaptive Management. Blogs to follow, but here’s a video preview

November 29, 2017

How Oxfam and Save changed US aid on local ownership: nice case study in influencing

I do love it when NGOs are taken by surprise in a good way – getting results in unexpected ways, rather than grinding through the plan. A neat example came up at Oxfam’s recent Evidence for Influencing conference. Here’s what happened.

Oxfam America and Save the Children wanted to persuade USAID to do more on ‘local ownership’ of aid. It’s a bipartisan issue in the US (the Bush Administration established the Millennium Challenge Corporation with an approach centred on local priorities; under President Obama USAID set up the Local Solutions Initiative, with the goal of channelling 30% of aid to local organizations.)

But the fear was that ownership could become just another passing fad. Despite a commitment to ownership by

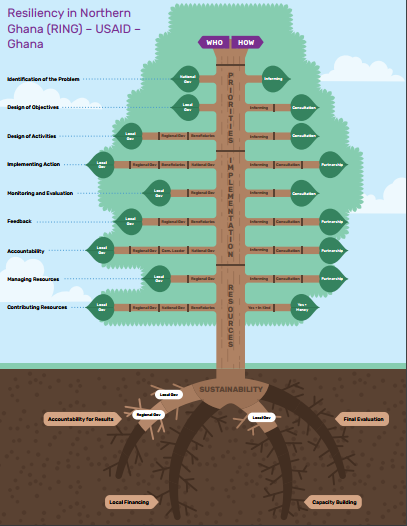

LEAF diagram for USAID project in Ghana

USAID and MCC leadership, plenty of officials looked like they were planning to do nothing, hoping that the topic would go away and they could get back to business as usual (doling out big chunks of aid cash to organizations like Chemonics). Oxfam doesn’t take USAID money, so it was easy to push localization, one aspect of USAID’s ownership approach. Save’s involvement was in that sense more laudable, because it runs counter to its short term financial interest.

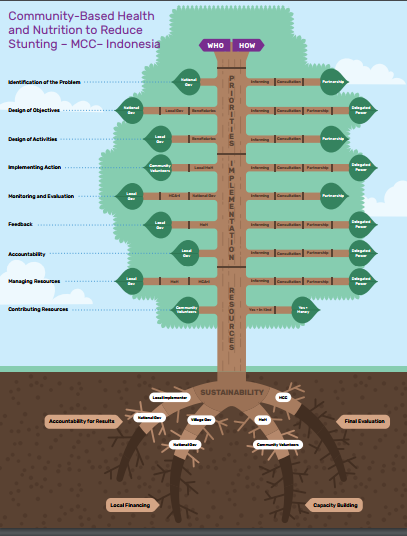

Initially, Save the Children and Oxfam planned to share positive ownership case studies of MCC and USAID projects in Indonesia, Jordan, Ghana and Rwanda. To do that, they needed some way of assessing ownership, so they developed a really boring-sounding tool – the Local Engagement Assessment Framework (LEAF). The results of which can be displayed in a rather nifty tree diagram (Leaf; tree – geddit?). The LEAF assessed ownership across the different phases of the project cycle (setting priorities, implementation; resourcing and long term sustainability). At each phase, they explored who was involved (the left-hand side of the tree – the broader the engagement the further left) and how (the right hand of the tree – length of branch determined by the amount of power in the hands of local stakeholders).

What happened next is the interesting bit: according to Oxfam’s Marc Cohen ‘we thought the case studies, telling the stories of ownership were going to be the thing. In the end, the tool has been more influential.’ USAID is considering a pilot using the LEAF as a project-planning and M&E tool. The Green Climate Fund has expressed interest in the LEAF as well.

Why? In large part, good/lucky timing. The big cheeses had said yes to ownership (eg signing the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness), and now the worker bees were saying ‘how?’ That kind of implementation gap + push from the top is an open door for advocacy.

As a result USAID, in the process of revising its internal guidance, committed itself to promoting and measuring ownership without an agreed upon strategy for doing so. The LEAF came along at just the right time, and USAID officials have suggested to staff that it’s a good tool to use in implementing the guidance.

LEAF’s design helped: to get access to the various project teams, the toolkit was deliberately less confrontational than the traditional NGO scorecard, and allowed for comparisons between countries and programmes without reducing everything to ‘a is better than b’.

LEAF diagram for MCC project in Indonesia

This played out through the internal battles within USAID, according to Save’s Kristin Sundell: ‘We were working with technocrats committed to advancing ownership but facing obstacles from their colleagues. The resistance was often ‘this is just flavour of the month, just sit it out til it passes. Our goal was to institutionalise ownership to survive the transition to the next [US] administration.’ The research, available at www.powerofownership.org, was just part of Oxfam America’s (and Save the Children’s) broader advocacy agenda in support of local ownership of development.

And the result? USAID staff are now evaluated and promoted based on how well they are doing on ownership and there has been a knock-on effect on recruitment and training. In so far as anything is certain at USAID these days (which is not very), promoting ownership is now hard wired into USAID.

There are some interesting wider lessons here. A new but fuzzy issue – local ownership – found its way into the policy funnel through the Paris Declaration and some leadership at the top of the US aid system. That created both an implementation gap and a window of opportunity for some smart advocacy. Similar things have been happening around ‘resilience’ or ‘modern slavery’. The lesson for activists is that in those situations, you need to help champions and supporters within the system enshrine the new approaches in their institutions, and helping them come up with practical ways to do so may be a better contribution than keeping up the pressure from outside.

Thoughts?

November 28, 2017

What does the rapidly changing face of UK and global aid look like, and what is at stake?

Oxfam aid wonk Gideon Rabinowitz (who really needs to get a new mugshot) reads the tea leaves of the latest UK aid stats

Anyone following aid discussions in recent years will have sensed the mood music changing. They have been increasingly dominated by an emphasis on economic development, the role of the private sector, securing results (including for taxpayers) and addressing donor strategic interests (e.g. in relation to migration). This contrasts somewhat with the aid agenda during the 2000s – spurred on by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – in which human development, basic services, the role of the state and country ownership were strong themes.

This changing aid agenda clear from trends in UK aid reported in detail last week in “Statistics on International Development 2017”.

SID 2017 dissects UK aid in unprecedented detail – a step forward in UK aid transparency. It points out that, in order to hit the aid target of 0.7%, the UK Government had to increase the aid budget by 10% during 2016 (required largely as a result of a new internationally-agreed methodology for calculating national income).

Digging deeper, there are five aid trends that emerge from the report:

Firstly, increasing levels of aid are being delivered through other government departments (OGDs) outside of DFID. The OGDs’ slice of the cake has been rising since 2014, and accelerated in 2016, when aid delivered outside of DFID increased by 48% to £3.5 billion, taking it to 26% of total UK aid. These increases have taken place despite growing concerns being raised by scrutiny bodies around the transparency, poverty focus and management of much of the aid being delivered by OGDs.

Firstly, increasing levels of aid are being delivered through other government departments (OGDs) outside of DFID. The OGDs’ slice of the cake has been rising since 2014, and accelerated in 2016, when aid delivered outside of DFID increased by 48% to £3.5 billion, taking it to 26% of total UK aid. These increases have taken place despite growing concerns being raised by scrutiny bodies around the transparency, poverty focus and management of much of the aid being delivered by OGDs.

Secondly, DFID is placing an increasing emphasis on economic development. This trend has been apparent for some time – aid to economic development doubled to £1.8bn during 2012/13-2015/16 – but has continued during 2016, with aid to economic development reaching record levels of around one-fifth of the UK bilateral aid budget.

Thirdly, there has been a stalling/decline in DFID’s ambitions on public services, such as health and education. Following significant increases pre-2013, UK bilateral aid spent on health fell by almost 20% during 2013-2015 and stagnated in 2016; as a share of UK bilateral aid it declined even more sharply during 2013-16 from 19% to 12%. Although UK aid for education went up by almost 50% in 2016, this increase largely compensated for major cuts  during 2012-15 and the share of education in UK bilateral aid remains some way below its 2013 peak (11.3% vs 13.5% of total spending).

during 2012-15 and the share of education in UK bilateral aid remains some way below its 2013 peak (11.3% vs 13.5% of total spending).

Fourthly, during 2014-16 there was a sharp decline in the share of UK aid to Least Developed Countries (LDCs, from 57% to 49%) and major increases in UK aid to Middle Income Countries (MICs, from 36% to 46%), especially to upper MICs. These changes can largely be attributed to DFID’s increased humanitarian support to the millions of vulnerable Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey (all upper MICs). However, this is not the whole story and the fact that other Government Departments beyond DFID spend three quarters of their aid in MICs and 37% in upper MICs also contributes.

Finally, hidden away down a long list of annexes, is data showing that “recipient country Governments” are declining as a partner for the UK Government in managing aid, as the share of aid they manage fell by 15% during 2015-16 (from £0.68 billion in 2015 to £0.58 billion in 2016). Amongst countries, Bangladesh, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Tanzania saw their government-led programmes cut by a third or more. Multilateral organisations seem to have picked up management of much of this.

Overall, therefore, UK aid is becoming notably more focussed on economic development, MICs and non-governmental partners, and less focussed on public services, LDCs and supporting Government-led programmes. DFID’s control over the UK aid budget is also rapidly weakening. This all adds up to arguably the most radical year of change in UK aid in modern times, with similar trends also apparent in global aid stats.

So, what questions do these trends highlight for UK aid and the changing nature of aid globally?

So, what questions do these trends highlight for UK aid and the changing nature of aid globally?

Support for economic vs social development

A rebalancing of aid towards economic development and away from social sectors is not a trend to be concerned about per se, especially as many developing countries have been demanding more economic support and face enormous challenge in generating jobs for their fast-growing populations. However, it poses questions about donor ambitions for addressing significant global health and education needs, and how donors will ensure that human development constraints don’t continue to limit the benefits of growth for the poorest. It also poses challenges for maintaining public support given that the public commonly view issues such as health and education as priorities for aid.

Support for LDCs (and low income countries) vs MICs

In recent years donor efforts to support LDCs have understandably been deflected by the very significant humanitarian and refugee crisis unfolding in Syria and the surrounding region. There are also significant poverty and inequality challenges in some MICs which UK aid is rightly addressing. However, cuts in aid to LDCs also signal an increasing appetite from donors to redirect aid to address strategic interests in relation to refugees, security and economic cooperation – usually most relevant to MICs. This raises questions about whether donors are really serious about eradicating extreme poverty and the goal to Leave No One Behind (LNOB) by 2030.

Support through partner country governments vs other development partners

Donors’ increasing unwillingness to channel aid through governments seems to have been driven in part by domestic political challenges to aid. However, principles on aid effectiveness learnt over decades suggest that such a response fails to recognise that working through Governments builds vital local institutions and promotes local leadership and ownership, while bypassing them can create inefficiencies and risks.

November 27, 2017

Winning Ugly and Learning from the Bad Guys: Discussing How Change Happens with the Greens

Had an HCH session with some extremely smart wonks at the Green Alliance last week. I gave my standard talk,  focussing on a ‘Power and Systems Approach’. This argues that for activism to be more in line with messy, emergent realities, activists need to change their way of working to give greater weight to:

focussing on a ‘Power and Systems Approach’. This argues that for activism to be more in line with messy, emergent realities, activists need to change their way of working to give greater weight to:

Curiosity – Study history and context; ‘learn to dance with the system’

Humility – embrace uncertainty/ambiguity

Reflexivity – be conscious of your own role, prejudices and power

Include multiple perspectives; unusual suspects; be open to different ways of seeing the world

The discussion got very deep very quickly, and had more questions than answers:

Firstly, how to respond to ‘windows of opportunity’. The bad guys (my words, not theirs) are pretty good at working around critical junctures (as set out in Naomi Klein’s book, The Shock Doctrine), but they don’t mess about with all this humility, reflexivity and ambiguity nonsense. In fact they are very linear, banging on about the same thing until a window of opportunity arrives, then driving their message home – TaxPayers Alliance, Milton Friedman, Chile’s Chicago Boys, Population Controllers, Haters of various stripes (Migrants, Moslems, Gays etc), certain populist politicians I could mention….

One of the Green Alliance wonks speculated that maybe that kind of linearity makes more sense if you are only working on one issue, or are ‘guided by a single ideology, from which everything else flows’. Environmentalism, by contrast, has to consider unintended consequences so that if you get one policy victory, it might make other things worse.

One of the Green Alliance wonks speculated that maybe that kind of linearity makes more sense if you are only working on one issue, or are ‘guided by a single ideology, from which everything else flows’. Environmentalism, by contrast, has to consider unintended consequences so that if you get one policy victory, it might make other things worse.

The perils of half-victories: winning can be tough for activists, because you hardly ever win clean. Instead a victory comes about through negotiation and compromise. Activists often divide over whether the compromises are necessary or a sell-out (as happened with the Jubilee Debt Campaign at the turn of the millennium). So is there any way to design a campaign to prevent the compromises being so great that the result is actually a step backwards? How to you create an ‘irreducible core’ to a campaign, eg a set of interlocking environmental principles that are proof against cherry-picking?

Evidence v Narrative: on the environment, is the good guys’ obsession with evidence, data and proving themselves right actually preventing them winning against an opponent more interested in narrative than evidence? Does it stop them seizing critical junctures (for example, by being over-worried about accusations of ambulance-chasing/manipulation if they start attributing climate disasters to man-made climate change)?

One GA wonk said the task was to educate the wider population, even if that meant eschewing a few quick wins – they go low and we go high. If they beat us with a lie, we take the long route back with evidence and education, we don’t just try and get better than them at lying.

That presumes both that there is some kind of underlying truth that we can arrive at through science and scrutiny, and that we need to take the population with us, or else eventually we will get caught out. I’m not sure all my campaigner friends would agree with tying your hands in that way.

I guess the underlying asymmetry between progressives and their opponents is that the progressives want to win pretty, and the others don’t care – they just want to win. We want wins that are inclusive, consistent with our values, and based on evidence and some notion of truth because we see those as part of the world we want to create. Certainly doesn’t make winning any easier, but it does make it more worthwhile.

Thoughts?

November 26, 2017

A wonderful book by Jean Dreze, India’s Orwell

Notes from my talk at last week’s launch of Jean Drèze’s new book, Sense and Solidarity.

Has anyone written Jean Drèze’s biography? If not, why not? A fascinating figure, surrounded by myths and legends (did he really sleep rough in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the square next to LSE, when he was a lecturer there?). He’s a wonderful writer who reminds me of George Orwell, with a distinctly Orwellian anger at poverty and injustice, combined with a commendably sparse prose and forensic eye for detail. But Drèze is Orwell Plus, because he is also an economist and has been an important participant in some of the most interesting social change episodes in recent Indian history. Just to muddle the comparison, Drèze was born in Belgium and Orwell in India (Bihar).

Drèze’s new book Sense and Solidarity brings together his writings on India in the 21st century – years of economic take-off and political and social tumult. His perspective is what he calls ‘jholawala economics’ – a tongue in cheek subversion of the derogatory Hindi word for backpacker activists.

The essays capture an unashamed commitment to ‘Research for Action’, as Drèze and his colleagues have sent hundreds of students (as well as himself) into the villages and households of the subcontinent to conduct research that is often life-changing (for the researchers, and sometimes, for India’s poor). Drèze argues that far from detracting from research, involvement as activists gives researchers new insights, joking ‘there’s nothing like a few days in jail to see the state from a new angle’.

The ‘action’ he seeks is a very Indian combination of public debate, judicial activism, and solidarity with the poor. And he has been at the heart of some spectacular actions, not least the Right to Food campaign, and the creation of the transformatory National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

The essays are clustered by topic – hunger, poverty, school meals, health care, child development and elementary education, employment guarantee, food security, corporate power, and war and peace. Anyone interested in public/social policy will find rich pickings here. Like Orwell, he is fascinated by details that matter – the debate over whether eggs should be included in school meals, themselves a victory for the Right to Food movement, warrants a whole essay.

The essays are clustered by topic – hunger, poverty, school meals, health care, child development and elementary education, employment guarantee, food security, corporate power, and war and peace. Anyone interested in public/social policy will find rich pickings here. Like Orwell, he is fascinated by details that matter – the debate over whether eggs should be included in school meals, themselves a victory for the Right to Food movement, warrants a whole essay.

His style is steely, but not shrill – the title captures his blend of dispassionate analysis and deep solidarity with the poor. He is charitable and finds hopeful initiatives to celebrate even in something as dire as India’s health system. But when he dislikes something (like the biometric identity system Aadhaar – here’s a critical film of testimonies about Aadhaar, collected by his students), he takes no prisoners. He concentrates on the policies, and so does not go in for the kind of Modi-bashing that commonly features on the Indian left.

However, he does share some other aspects of its world view: In Drèze’s narrative, India is made up of citizens organizing to put pressure on the state, both directly or through the courts. The private sector appears only as pantomime villain, pillaging the state or crushing the poor. Environmental issues warrant barely a mention (a gap he himself acknowledges).

When I raised these points, Drèze stuck to his guns (via skype) ‘I‘m in favour of the private non-profit sector. The profit sector is important, but in the field of social policy, especially in India, the corporate sector has been a bit of a nuisance. It disparages all the social programmes, and my guess is that is because they know that if the government spends more on social policy, it means higher taxes or less money for infrastructure contracts.’

profit sector is important, but in the field of social policy, especially in India, the corporate sector has been a bit of a nuisance. It disparages all the social programmes, and my guess is that is because they know that if the government spends more on social policy, it means higher taxes or less money for infrastructure contracts.’

All in all a wonderful book and an indispensable man. Oh, and I checked with the man himself; his reply ‘About sleeping in LIF, yes, it’s true – I feel nostalgic!’

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers