Duncan Green's Blog, page 214

May 31, 2013

Be the Toolkit: Discussing complex systems with Oxfam’s next generation of leaders

Over the next few months, I’ll be getting stuck into a big Oxfam project on how we understand and work on issues of power and change. As befits its

yeah, right

focus on ‘how change happens’, this is already evolving in unexpected directions, such as a stress on how we support Oxfamistas to work in ‘complex systems’ (aka the real world). Last week we had 30 of our brightest sparks in a room for a half day on this – here are some of the points that came up.

First up, a great way to get people thinking about complex systems and the contrast with the illusory certainties of project planning. Ask participants ‘Think back to your expectations for your life when you were 16. Has it gone to plan?’ Then stand back, enjoy the incredulity and draw out the connections with aid work (influence of random events, importance of relationships etc etc),

Next the thorny question of ‘critical junctures’ – those shocks that contain huge opportunities for changes, to which we have generally been pretty rubbish at responding. Some CJs are foreseeable – eg elections – and there the challenge is just to get a bit more intelligent in our planning. But others – eg Arab Spring – are not in anyone’s calendar. Can we get better at seeing them as they approach?

Based on her understanding of complex systems, complexity physicist Jean Boulton (who also came up with the life expectation tip) suggested a few telltale signs:

Increased swings and instability

Trust your instinct/judgement

Some early indicators might exist – these could include anything from UN Global Pulse type data harvesting from social media to the entry of intermediate/professional organizations into areas formerly dominated by radical activist groups (a sure sign that an issue is going mainstream)

Otherwise look for ‘weak signals’ – a small sense of ‘we’re getting somewhere’, eg anecdotes of new forms of organization/actor emerging, different constituencies saying the same thing, increasing interest from newspapers, traditional leaders or social media.

But this assumes the existence of neutral observers capable of spotting such signals, whereas we NGO types are all too willing to see what we want to see – alleged ‘weak signals’ are likely to proliferate as every staffer tries to persuade their bosses that the revolution is just around the corner, so please could they have some more budget?

My conclusion was that the more realistic option is to concentrate on the foreseeable junctures such as elections, and try and get better at spotting and responding to the unpredictable events once they occur. That means feedback loops based on savvy staff rooted in local realities, empowered to blow institutional whistles, hit red buttons etc when eg food prices rocket or protest movements start picking up pace.

Persistence is the flip side of jumping opportunistically between critical junctures and it makes my head hurt. If development is in many cases long-term, then aid agencies have to think over 10 or 20 year timespans. It could well be a disaster if a complexity focus led to us hopping madly from issue to issue in a desperate search for the next Arab Spring.

Persistence is the flip side of jumping opportunistically between critical junctures and it makes my head hurt. If development is in many cases long-term, then aid agencies have to think over 10 or 20 year timespans. It could well be a disaster if a complexity focus led to us hopping madly from issue to issue in a desperate search for the next Arab Spring.

But equally, if you’ve been plugging away at a project for a few years without results, how can you distinguish between a productive long haul that just needs time, and a miserable failure that is going nowhere? Whose judgement can you trust on this? If the answer is only evident in hindsight, how on earth do you make decisions in real time? Suggestions welcome!

Lots of discussion on how to use theories of change to improve our work, but the danger there is that ToCs, complexity etc will become just another toolkit – a checklist that closes down thought and creativity, rather than the opposite. Much the same happened to the logframe back in the day.

The focus needs to be on supporting staff to build the skills, imagination and ability to understand and respond to what is going on around them. That needs lots of discussion, mentoring, and maybe even some suitably non-prescriptive methods, but we need to keep the focus on the people, not the process. With due apologies to Gandhi, ‘Be the toolkit’ seemed to work as a slogan on where to keep the focus.

Another nagging question is how do you fund work based on complex systems? Can you really rock up to DFID and say ‘hey, it’s a complex system, so we have no idea what’s going to happen. Can we have £1m please?’ Answers include:

Collecting and publishing narratives where donors get it right: the conventional picture of donors hunched jealously over their logframes, hostile to anything smacking of independent thought, is clearly nonsense. But we don’t do enough to capture some great examples of imaginative donorship, such as DFID in Tanzania or the Swiss in Tajikistan. We need to collect these stories, and work with allies in aid agencies to get them out there.

Trust Fund: Push the trust fund model as a way of turning large chunks of aid into lots of small chunks – the right size for the kind of initiative that needs funding, but would be crushed by the big bucks and paperwork that goes with them.

Incubation period model: Back to Matt Andrews. How do we get a prolonged experimental incubation phase accepted as a standard (and extended) part of any project application? Interestingly, DFID is starting to do this with some of its research funding – supporting a year-long inception phase during which researchers can clarify and narrow down their agenda.

And finally, a comment from Alan Hudson on my last complexity-related post has stayed with me. ‘One of the things that struck me was that we had a very fruitful exchange without a mention of “complex systems. It just wasn’t necessary.’ Which reminds me of a comment that I think is great, but always seems to produce baffled faces in seminars – ‘talking about ‘non-linear systems’ is like talking about all the ‘non-elephants at the zoo’’: i.e. since non-linearity is the norm, not the exception, why does it need to be picked out? Will the mark of success in getting complex systems taken seriously be when they are merely seen as normal and the off-putting word ‘complexity’ becomes redundant?

May 30, 2013

The best thing I’ve read on Syria’s nightmare: Five conflicts in one; don’t send arms

Some excerpts from a great overview of the Syrian conflict in the London Review of Books by Patrick Cockburn. Read the whole piece if you can. It helped confirm for me that Oxfam’s right to oppose the EU’s ending of its arms embargo. Simon Jenkins’ polemic in the Guardian also helped.

helped confirm for me that Oxfam’s right to oppose the EU’s ending of its arms embargo. Simon Jenkins’ polemic in the Guardian also helped.

‘That Assad’s government is on its last legs has always been something of a myth. YouTube videos of victorious rebel fighters capturing military outposts and seizing government munitions distract attention from the fact that the war is entering its third year and the insurgents have succeeded in capturing just one of the 14 provincial capitals. (In Libya the insurgents held Benghazi and the whole of the east as well as Misrata and smaller towns in the west from the beginning of the revolt.) The Syrian rebels were never as strong militarily as the outside world supposes. But they have always been way ahead of the government in their access to the international media.

Whatever the uprising has since become it began in March 2011 as a mass revolt against a cruel and corrupt police state. The regime at first refused to say much in response, then sounded aggrieved and befuddled as it saw the vacuum it had created being filled with information put out by its enemies. Defecting Syrian soldiers were on television denouncing their former masters while government units that had stayed loyal remained unreported and invisible. And so it has largely continued. The ubiquitous YouTube videos of minor, and in some cases illusory, victories by the rebels are put about in large part to persuade the world that, given more money and arms, they can quickly win a decisive victory and end the war……

Assad isn’t going to win a total victory, but the opposition isn’t anywhere close to overthrowing him either. This is worth stressing because Western politicians and journalists so frequently take it for granted that the regime is entering its last days. A justification for the British and French argument that the EU embargo on arms deliveries to the rebels should be lifted – a plan first mooted in March but strongly opposed by other EU members – is that these extra weapons will finally tip the balance decisively against Assad. The evidence from Syria itself is that more weapons will simply mean more dead and wounded……

Fear of widespread disorder and instability is pushing the US, Russia, Iran and others to talk of a diplomatic solution to the conflict. Some sort of peace conference may take place in Geneva over the next month, with the aim at least of stopping things getting worse. But while there is an appetite for diplomacy, nobody knows what a solution would look like. It’s hard to imagine a real agreement being reached when there are so many players with conflicting interests.

Fear of widespread disorder and instability is pushing the US, Russia, Iran and others to talk of a diplomatic solution to the conflict. Some sort of peace conference may take place in Geneva over the next month, with the aim at least of stopping things getting worse. But while there is an appetite for diplomacy, nobody knows what a solution would look like. It’s hard to imagine a real agreement being reached when there are so many players with conflicting interests.

Five distinct conflicts have become tangled together in Syria: a popular uprising against a dictatorship which is also a sectarian battle between Sunnis and the Alawite sect; a regional struggle between Shia and Sunni which is also a decades-old conflict between an Iranian-led grouping and Iran’s traditional enemies, notably the US and Saudi Arabia. Finally, at another level, there is a reborn Cold War confrontation: Russia and China v. the West. The conflict is full of unexpected and absurd contradictions, such as a purportedly democratic and secular Syrian opposition being funded by the absolute monarchies of the Gulf who are also fundamentalist Sunnis.

By savagely repressing demonstrations two years ago Bashar al-Assad helped turn mass protests into an insurrection which has torn Syria apart. He is probably correct in predicting that diplomacy will fail, that his opponents inside and outside Syria are too divided to agree on a peace deal. He may also be right in believing that greater foreign intervention ‘is a clear probability’. The quagmire is turning out to be even deeper and more dangerous than it was in Iraq.’

h/t Jon Snow

May 29, 2013

Is it just me, or is it getting harder to read books on development?

I just spent four hours reading a book. Well, a third of a book – I’m a slow reader. It’s the galleys for ‘Aid on the Edge of Chaos’, by Ben Ramalingam, due out this October. I’ll review it when it’s published, but reading it made me think about books in general, and how hard it is to read them.

out this October. I’ll review it when it’s published, but reading it made me think about books in general, and how hard it is to read them.

The standard response of my colleagues when I review a book on the blog is ‘Wow, I’m so jealous – you’re so lucky to have the time to read them’, shortly followed by ‘Great, now I won’t have to read it – I can just read the review’. My fear is that they are typical – not many people in the NGOs read books related to their work. When Oxfam decided to close down its library a few years ago, there was barely a murmur of protest.

The discomfort I experience when reading a book during working hours may help explain why this is. Far from being a delightful act of self indulgence, I feel itchy, guilty, check my emails and blog traffic every hour or so ‘just in case’, and get a glow of relief when I find something I need to reply to. And I’m supposed to be a bookworm!

The growing distance between the rhythm of work, and the slow digestion of a book may be part of the answer – a fellow blogger once confessed he hardly ever reads books any more because of the ‘ADHD state’ brought on by his constant use of email and twitter. I have colleagues who can’t even have a conversation without compulsively checking their blackberries (although that might just be the effect I have on people). Even when it comes to the aptly-named ‘grey literature’ of papers and reports, we’re all executives now (at least in terms of only skimming the exec sums). What’s happened to our collective concentration span?

Once I manage to suppress my anxiety, and persevere, a good book delivers on many more levels that even the best paper. The writing is often better (a book is a far more personal labour of love than any research paper); you argue with the weak arguments, and assimilate the convincing ones, in a more profound process, like a day-long tutorial. And yes, I write all over them, sorry. At their best, they usher you into a whole new paradigm, profoundly changing the way you see the world. And then of course there is the surge of self-satisfaction when you finish it…..

I can’t see why papers shouldn’t in theory be able to do all of this, and maybe some can, but in my experience nothing matches the revelatory intellectual impact of books like Eric Beinhocker’s The Origin of Wealth or Ha-Joon Chang’s Kicking Away the Ladder. So if people stop reading books

the exception to the rule, obviously

once they stop being students or keen newbies in the aid world, does that mean they will miss out?

But before getting all doom and gloom, let’s see if I’m right. It’s time to fess up. When was the last time you read a book on international development. A proper book – at least 150 pages. And all of it – not just skipping to the conclusions? You know the drill – voting options to your right. And since it’s fairly safe to assume that the readers of this blog are at the wonkier end of the spectrum, I’ll take the result as the upper limit for development bookworminess.

May 28, 2013

What are the secrets of some recent campaign successes?

This guest post comes from Hannah Stoddart, Oxfam’s Head of Economic Justice Policy

It feels like Oxfam campaigners have been celebrating a lot recently. First – after nearly 10 years of hard slog as part of the Control Arms coalition – we got an Arms Trade Treaty. Then just a few weeks later two of the companies we’d been targeting in our Behind the Brands campaign agreed to change their policies in response to public pressure. Then, after months of targeting the World Bank with our land grabs campaign, President Jim Yong Kim issued a public statement acknowledging that the World Bank must play a role and agreeing to improve its standards in line with human rights obligations.

So are some of the most powerful interests and institutions beginning to bend quicker in response to campaign pressure? Are NGOs getting better at campaigning? Or would they have done it anyway? These are the kinds of questions that campaigning organisations ask themselves all the time. How can we really measure the extent of our influence? And what tactics are likely to yield the best results?

I can’t speak on behalf of all organisations, or indeed all of Oxfam’s campaigns, but having managed Oxfam’s global land grabs campaign for the past year, which targeted the World Bank, I have learned some important lessons about what works.

Firstly, be a bit outrageous – there is so much noise these days that you have to shout even louder to get attention. At Oxfam, rather than just asking the Bank politely to take action on land grabs, we told them to freeze all their agricultural land investments. This is probably the last thing a Bank ever wants to do. It goes against the very essence of what they see as their job – getting money out of the door. So naturally the ask both outraged the Bank but also got us noticed.

Secondly, have an insider/outsider strategy – it’s crucial from the outset to have a strategy that mobilizes the public on the outside, but also engages critically on the inside. Alongside more populist stunts including auctioning off famous landmarks and crowdsourcing thousands of videos and setting them to a Coldplay track, Oxfam was also developing detailed and legalistic documents outlining how the Bank could improve its safeguard policies. If that sounds impenetrable and wonky, it’s because it is. Good campaigns need to be both fun and appealing, as well as being backed up behind the scenes by serious analysis.

There was one point at the recent Spring meetings in Washington when colleagues were engaged in serious technical discussions with Bank officials, while a van drove past outside bearing a huge placard entreating the Bank to ‘stand and deliver’. That seemed to me to exemplify the insider/outsider approach. It also meant we were developing relationships with officials within our ‘target’ institution who would be able to help implement the changes we were calling for.

Tanzanian Independence monument

Thirdly, think about how you will react to different kinds of ‘success’.

Though in the end – with this particular campaign – the Bank didn’t freeze its investments, we had thought through lots of different scenarios and how we would react depending on what the Bank eventually conceded. We were not fixated on only one outcome and were prepared to respond to positive developments as and when they arose. In the end, we felt we had ‘sufficient wins’ to welcome progress made, but we still criticized the Bank where we felt there hadn’t been enough progress.

Perhaps one of the greatest lessons for campaigning organisations from the Copenhagen Climate Summit in 2009 was that resting everything on one outcome compels you to announce a failure if that outcome is not achieved, even if there have been other significant successes beneath that. Sure, there was no global deal at COP15, but getting one would have been well-nigh impossible, and rarely did you hear NGOs celebrate the significant commitments that were made.

Related to this – a good campaign needs to use both carrot and stick. Powerful institutions should expect to – and indeed should welcome – being held to account in the public eye, so no campaigning organization should cave in if the target gets stroppy and accuses you of being unfair.

Equally, NGOs too often refuse to welcome progress made or cast commitments by their targets in a positive light. This can undermine goodwill on behalf of the target, and also disillusion campaigners who feel that it’s impossible to make a difference. When President Jim Kim made his statement on land, Oxfam welcomed the positive commitments made. We also published a critical blog addressing the areas where less progress had been made, but we were prepared to publicly welcome steps in the right direction. This made a big difference in building trust with people within the Bank who were supportive of our goals.

Fourthly, use online social media as a lobby as well as a campaign tool – as well as allowing much wider sharing of campaign actions and stunts, there’s also an increasing role for social media in communicating with your target. Outlining your critique and your asks in a blog means they are more likely to read it before everyone else does.

Lastly, working with allies is crucial in building legitimacy for your campaign. This doesn’t necessarily have to be through co-branded coalitions, neither does it mean aligning every single message. But it does mean reinforcing each other’s messages at crucial points – through blogs, letters, press releases and official submissions. Oxfam worked closely with Inclusive Development International in our detailed submission to the Bank calling for a land safeguard – and others also supported our asks in roundtable discussions and consultations. Equally, Oxfam puts its name to wider civil society calls for human rights to be at the heart of the Bank’s approach to development, even if that wasn’t the core message of the campaign.

One other thing.. get celebrities involved if you can – one of the best moments of the campaign was when the World Bank tweeted Coldplay. We never thought that would happen, but it shows that even the most conservative institutions are vulnerable to popstars telling them to do stuff.

There is clearly no one-size-fits-all approach to achieving change, but campaigning organisations arguably don’t reflect enough on successes when they do happen. Given decades of feeling disappointed in the global campaigning space, its high time we all reflected on what really works.

And here’s that Coldplay video again

May 24, 2013

Are illicit drugs a development issue and if so, what should we do about it?

I spent Wednesday morning taking drugs seriously. OK that’s the last of the lame do/take drug jokes. What I actually did was have a coffee with Danny Kushlick and Martin Powell of the Transform Drug Policy Foundation, and then attend a Christian Aid seminar on drugs and development. Both conversations addressed the same questions: are drugs becoming an un-ignorable development issue and if so, what should we (INGOs, aid agencies etc) do about it?

Kushlick and Martin Powell of the Transform Drug Policy Foundation, and then attend a Christian Aid seminar on drugs and development. Both conversations addressed the same questions: are drugs becoming an un-ignorable development issue and if so, what should we (INGOs, aid agencies etc) do about it?

The answer to the first question is pretty obviously ‘yes’. In the rich countries the ‘war on drugs’ is getting nowhere, stymied (among other reasons) by the basic laws of supply and demand – any success in the war reduces supply, so prices rise, so supply recovers. In the producer countries, the vast sums involved ($330bn a year, by one estimate) poison politics. And increasingly, the divide between producer and consumer countries is being eroded, as drugs spill over into the slums and alleyways of the developing world – including West Africa, where transhipment and consumption are becoming major issues. Everyone gets dirty, trust is destroyed, communities turn bad. As Christian Aid’s Paul Valentin said, ‘the drugs trade cuts across everything we do – inequality, tax havens, access to services, HIV. Over half the countries we are working in are directly affected.’

And it is likely to grow in prominence: Fiscal pressures in the North will draw attention to the vast waste of money involved in criminalizing drug users and then having to pay Hilton-like amounts to keep them rotting in jail. Arguing that the drug trade is wrecking their countries, a number of Latin American governments, led by a weird combination of Uruguay (centre left) and Guatemala (ex-military president) have successfully challenged the US in getting the normally supine Organization of American States to issue a report last week that some saw as ‘the beginning of the end for blanket prohibition’. They have helped persuade the UN to bring forward to 2016 its General Assembly Special Session on reviewing global drug policy.

OK, but in development policy world, Cinderella issues seem to outnumber the real ones, and if I raise this one with the poor souls who have to try and set priorities for a large NGO like Oxfam, then (in the words of my colleague Ian Bray), ‘eyeballs will roll’. I can hear them now: Yet another topic. What do you want us to stop doing? Spreading ourselves too thin. Tough choices. What do we know about drugs policy? Etc etc.

So let’s look at this as a change process. Where are we on the journey from denial to ‘drugs policy at the heart of all we do’? Taking Matt Andrews’ book as a starting point (as I seem to do a lot at the moment), a shift of this sort takes place in 5 stages, with potential roles for outsiders at each stage

Deinstitutionalization: encourage the growing discussion on the problems of the current model

Preinstitutionalization: groups begin innovating in search of alternative logics

Theorization: proposed new institutions are explained to the broader community, needing a ‘compelling message about change.’

Diffusion: a new consensus emerges

Reinstitutionalization: legitimacy (hegemony) is achieved.

It seems to be that the deinstitutionalization of current drugs policy is well under way(see this UN paper or World Bank report) – we can foresee a point where almost everyone accepts that it isn’t working, and it’s costing a fortune. Looked at in this way, it is probably more important for those wishing to have an impact to stop bashing the current policies, and to move on to the next stages – searching for alternatives and building a new consensus.

It seems to be that the deinstitutionalization of current drugs policy is well under way(see this UN paper or World Bank report) – we can foresee a point where almost everyone accepts that it isn’t working, and it’s costing a fortune. Looked at in this way, it is probably more important for those wishing to have an impact to stop bashing the current policies, and to move on to the next stages – searching for alternatives and building a new consensus.

That’s certainly what Transform is doing, making the case for a humane system of regulation (cf pharmaceuticals) as a sensible position between the polarized lunacies of the status quo and ‘legalize everything man’. But the problem here is the huge spread of ideologies in the reform camp, from libertarian stoners to security nuts, making it very hard for any new consensus to emerge beyond ‘this ain’t working’.

But then I got to thinking about what other former eyeball-rolling issues have moved into the mainstream in recent years, and hit on climate change. Ten years ago, global warming was definitely in the ‘groan, ignore, reject’ camp within development circles. Now it is very mainstream indeed. Oxfam does a shedload of work on the ground in terms of climate change adaptation – not sure what the equivalent on drugs would be – protection committees in Tijuana?

A more relevant comparison is with influencing the wider debate, where I think NGOs have gone in two broad directions on climate change: one has been to ‘bear witness’, showing from our experience on the ground that climate change is about people, not just polar bears. I think we’ve had real impact there and coincidentally, it fits with another of Matt Andrews’ findings that outsiders are better off sticking to problem definition than trying to propose solutions.

The other area has been to engage more directly in policy debates, and there, to be honest, I’m less convinced we’ve had much impact. Partly this is because the climate change policy response as a whole is badly becalmed. But also because, however smart the people involved, I don’t think that plays to our strengths in terms of legitimacy.

because the climate change policy response as a whole is badly becalmed. But also because, however smart the people involved, I don’t think that plays to our strengths in terms of legitimacy.

But what if we do want to go beyond repeating ad nauseam ‘drugs are a development issue’ (and rest assured, we will immediately be grilled on what we think about legalization etc)? Paul Valentin, Christian Aid’s International Director, thought it might play a convenor/broker role in getting faith institutions to think about this (an inter-faith dialogue on drugs, development and social justice anyone?). Another option is at least to include organized crime explicitly as part of our context and power analysis work. But should we go further, perhaps making the UNGASS 2016 the focal point of a global campaign?

So let’s have a vote – not because it (or I) will have any influence on Oxfam policy, but because I want to know what you think, (and also because I want a new poll so I am not reminded every day how badly I was mashed by Claire Melamed on post-2015). Do you think INGOs should a) avoid drugs as a campaign issue, b) engage in a limited ‘bearing witness mode’ on drugs and development or c) get stuck in as a major campaign. And remember, more work on drugs means less work on other stuff.

One final comment: there is some good advocacy work going on in this area. See for example the Count the Costs initiative, which has a useful briefing on drugs and development. That kind of thing needs funders, and the Open Society Foundation and George Soros deserve a lot of credit for a lot of it. It is vital to have this kind of outlier support, not least because of the tendency for development organizations to indulge in herd behaviour. When we finally get interested in some new issue, it can save years if some smaller, more nimble outfits have been able to find the funding to develop the thinking around it before the larger organizations lumber into town.

May 23, 2013

‘Squeezed’: how are poor people adjusting to life in a time of food price volatility?

Ace IDS researcher Naomi Hossain introduces the first results of a big Oxfam/IDS research project on food price volatility

If the point of development is to make the Third World more like the First, then we aid-wallahs can pack our bags and go home. Job done.

The most striking finding of Squeezed, the first year results from the four year Life in a Time of Food Price Volatility research project, is how like the people of the post-industrial North the people from the proto-industrial South now sound:

Stressed and tired

Juggling work and home

Surrounded by selfish individualists, led by uncaring politicians

In strained relationships

Constantly pressed for time

Never enough money, even for the basics.

‘Squeezed’ is how the UK has been describing its middle classes, beset by austerity and recession. But the countries in our research have high growth rates and apparently a lot of poverty reduction.

So what’s squeezing them? The accumulation of five years of cost of living – particularly food price – rises, is the short answer. The early research results suggest price rises are bringing about social change by stealth, as people and their relationships to food (and each other) are being commodified faster than ever before. Policymakers seem oblivious to these changes, obsessed as they are with changes they can measure.

What does it matter if food prices rise? Economists tell us it doesn’t, at least not in the long run. Wages adjust, they say. High food prices mean more people will grow food, is the theory. People substitute cheaper alternatives for newly expensive foodstuffs.

Well, yes, wages adjust, people grow more food and substitute. But these are not costless adjustments. Wages are rising, for most people, but at a price: more dangerous jobs (work in a Bangladeshi garments factory, anyone?), less reliable work, more competition as women flood the informal sector. People don’t feel better off. Home life is less harmonious, with the unpaid work of care left undone or shouldered by harassed working mothers, tired grandparents or children. People see their wages rise but know this is a mirage: they are not, in fact, getting any better off. It is more difficult to save and so also more difficult to hope or aspire. Small wonder the period since 2008 has been replete with global disgruntlement: riots, protests, even the odd revolution.

Well, yes, wages adjust, people grow more food and substitute. But these are not costless adjustments. Wages are rising, for most people, but at a price: more dangerous jobs (work in a Bangladeshi garments factory, anyone?), less reliable work, more competition as women flood the informal sector. People don’t feel better off. Home life is less harmonious, with the unpaid work of care left undone or shouldered by harassed working mothers, tired grandparents or children. People see their wages rise but know this is a mirage: they are not, in fact, getting any better off. It is more difficult to save and so also more difficult to hope or aspire. Small wonder the period since 2008 has been replete with global disgruntlement: riots, protests, even the odd revolution.

Higher prices should mean people try to grow more food, but returns are unpredictable even while input costs rise. No sane young person wants to be a farmer when they grow up. The only appetite for growing more food seems to be in kitchen gardens: wherever people have a patch of land and the time, they are trying to avoid food markets by growing their own.

And yes, people substitute. They eat more tasteless food, protein-less staples tarted up with monosodium glutamate and e-numbers, cheap and cheerful sauces that the food companies are selling more of. They eat more dangerous food – smelly rice, broken eggs, fish of uncertain origins, pesticide-sprayed vegetables.

In these days of food price volatility, food is further from being a right than it has ever been. The change in how people relate to food – and each other – is one of kind more than quantity: uncertain and relatively high prices mean prioritising earning the cash needed for food above all else.

The squeeze is tighter in Nairobi than in London, true, but in both places, price rises force people onto the uncertain mercies of charity – NGOs and aid  in Nairobi, food banks in London. Global food policy makers need to check their assumptions about adjustments to food prices, and decide whether they want the kinds of societies where cash matters above all else.

in Nairobi, food banks in London. Global food policy makers need to check their assumptions about adjustments to food prices, and decide whether they want the kinds of societies where cash matters above all else.

Pushing back against the squeeze on everyday lives means policies that protect people – stabilising prices for farmers and consumers and developingemergency ‘spike-proofing’ cash or food subsidies. It means policies that ensure everyone has the right to eat well and to be part of decisions about the food they eat, rather than relying on faceless global markets.

Ignoring the squeeze on everyday life that rising and volatile food prices create for people in poverty everywhere is dangerously short-sighted, and not only for people in the poor South. In the long run, we are all commodified.

And here’s Naomi introducing the report (6m video)

May 22, 2013

Aid and complex systems cont’d: timelines, incubation periods and results

I’m at one of those moments where all conversations seem to link to each other, I see complex systems everywhere, and I’m wondering whether I’m starting to lose my marbles. Happily, lots of other people seem to be suffering from the same condition, and a bunch of us met up earlier this week with Matt Andrews, who was in the UK to promote his fab new book Limits to Institutional Reform in Development (I rave reviewed it here). The conversation was held under Chatham House rules, so no names, no institutions etc.

starting to lose my marbles. Happily, lots of other people seem to be suffering from the same condition, and a bunch of us met up earlier this week with Matt Andrews, who was in the UK to promote his fab new book Limits to Institutional Reform in Development (I rave reviewed it here). The conversation was held under Chatham House rules, so no names, no institutions etc.

Whether you work on complex systems or governance reform or fragile states, the emerging common ground seems to be around what not to do and to a lesser extent, the ‘so whats’. What can outsiders do to contribute to change in complex, unpredictable situations where, whether due to domestic opposition or sheer irrelevance to actual context, imported blueprints and ‘best practice guidelines’ are unlikely to get anywhere?

In his book Matt boils down his considerable experience at the World Bank and Harvard into a proposal for ‘PDIA’ – Problem Driven iterative adaptation, which I described pretty fully in my review. The conversation this week fleshed out that approach and added some interesting new angles.

PDIA needs funding, but not big million dollar cheques that come with all the paraphernalia of targets, milestones, logframes etc that are more likely to kill thought than promote experimentation and learning. Instead, it needs a trust fund approach – lots of small grants that allow incubation of local solutions to a given problem while ‘avoiding a premature results agenda’.

But does that mean that institutional reform should avoid the big aid dollars altogether? Matt thought not – he portrayed PDIA as a new and extended incubation phase, which can then take the homegrown solutions that emerge and move into the more traditional aid world of large scale, large budget programming. So the challenge for aid agencies is how to create, fund and protect a space within their institutions for small budget experimentation and incubation, sitting in parallel with the big stuff.

Timelines emerged as a useful, but undervalued tool. But these are timelines of what has actually happened in the past, not the imaginary future timelines of funding applications. Matt reckons any project seeking funding should start by building a 20 year timeline of what has happened on that issue/in that locality. If done properly, the exercise of reconstructing the timeline using documents and interviews will reveal overlapping interpretations of what actually happened and recover the kinds of knowledge and experiences that all too often go missing in Aid World as staff leave and projects are wound up. We need a decent timeline methodology – Matt uses the work of Peter Hall at Harvard but it also sounds a lot like process tracing, something our MEL team uses.

Timelines emerged as a useful, but undervalued tool. But these are timelines of what has actually happened in the past, not the imaginary future timelines of funding applications. Matt reckons any project seeking funding should start by building a 20 year timeline of what has happened on that issue/in that locality. If done properly, the exercise of reconstructing the timeline using documents and interviews will reveal overlapping interpretations of what actually happened and recover the kinds of knowledge and experiences that all too often go missing in Aid World as staff leave and projects are wound up. We need a decent timeline methodology – Matt uses the work of Peter Hall at Harvard but it also sounds a lot like process tracing, something our MEL team uses.

The issue of narratives is central – it lies at the heart of the response to a reductionist results agenda that privileges pseudo medical trial data over real experience. Claire Melamed likes to say ‘the plural of anecdote is not data’. True, but I think that a well researched anecdote rapidly becomes a ‘narrative’, and the plural of narrative can definitely be evidence, if not data. Matt, ODI and Oxfam are all separately thinking about the need to build a collection of rigorous, nuanced narratives on stories of power and change – we’ll be swapping notes and hopefully coming up with some ideas for working together on this. What would people recommend in terms of references on rigorous narrative methodologies?

There was a good discussion on what constitutes ‘results’. Good PDIA-type work in developing countries requires a rapid feedback loop of results, but of a different kind to those typically demanded by the aid business. Developing country politicians want to know what’s happening with their money, what has been learned, what has worked and what hasn’t, and how the project has responded. They don’t need the (often bogus) certainty and data demanded by aid planners.

I do find this all slightly baffling – politicians intrinsically know how to navigate in complex environments, respond to shocks and opportunities, using trial and error, instinct and rules of thumb. They make decision on partial information and change direction if things don’t work. That’s what politics is about. But then they become aid ministers in donor countries, and suddenly buy into a paraphernalia of logframes and a particular understanding of results that in some other part of their brains they must know has huge limitations in the real world. How to get ministers to think more like pols and less like aid bureaucrats?

results that in some other part of their brains they must know has huge limitations in the real world. How to get ministers to think more like pols and less like aid bureaucrats?

All fascinating and thanks to Matt for kicking off and CGD Europe for organizing the discussion (am I allowed to say that under Chatham House rules? If not, please ignore). I’m thinking of writing a paper on the ‘so whats’ of complex systems, but will first wade through the draft of Ben Ramalingam’s forthcoming book before deciding whether it’s necessary.

Update: more thoughts from Matt Andrews on his blog

May 21, 2013

Why building ‘resilience’ matters, and needs to confront injustice and inequality

Debbie Hillier,

Oxfam’s Humanitarian Policy Adviser (right), introduces ‘No Accident’, Oxfam’s new paper on resilience and inequality

Asking 50 Oxfam staff what they think of resilience will get 50 different responses. These will range all the way from the Sceptics (“just the latest buzzword, keep your head down and it’ll go away”), to the Deniers (“really nothing to do with me”) to the Pioneers (“it’s obvious, we’ve been doing this for years”). But probably the biggest category would be the Unsure Interested – “well, I suspect it’s pretty important, but I’m really not clear what it means for me.”

Answering that last point is key, and at a recent Oxfam get together, a humanitarian colleague gave a wonderful example. He spoke about a tropical storm which had devastated a rural area of Honduras; Oxfam humanitarian staff had responded quickly and effectively with water and sanitation, cash-for-work, and essential household items to help people get back on their feet. But when he visited the area, and talked to the community, he found that the problem was less about flooding, and more about agribusiness.

Local communities had been displaced by massive sugar and melon plantations, denuding the land of trees, diverting water sources and thus altering the local hydrology. The companies had employed cheaper Guatemalan labourers from over the border, so people no longer had either land to farm or paid labour, leaving them without livelihoods and impoverished.

All the tropical storm did was to expose the deepening vulnerability of the community. So while Oxfam’s humanitarian response helped the community to cope with the flood, it would leave them in no better position for when the next inevitable storm/flood came.

People in a waterside house raised on stilts in a slum in Manila. © Robin Hammond / Panos

A programme with ‘resilience’ as the desired outcome would look at the underlying factors for people’s vulnerability. Critically, it would look at power dynamics and inequality (the latter extremely high in Honduras: for index geeks, a Gini coefficient of 55). These are too often left out of the resilience debate, which so far has focused more on technical measures. Yet Oxfam’s new report, No Accident, shows that countries with higher income inequality have populations which are more vulnerable to climate change, natural hazards and conflict.

The link between inequality and vulnerability is no doubt complex and defies simple correlation or causation. But using language like ‘risk being dumped on the poor’ opens up a new way of looking at vulnerability. At the international level it’s easy to see – rich countries reap the economic rewards of pumping carbon into the atmosphere, but poor countries bear the highest burden. So whilst the impact of climate change by 2100 is estimated to cause GDP losses of 12-23% in poor countries, in the richest countries, the impact will be a range of 0.1% loss to a benefit of 0.9% of GDP.

Biofuel production and excessive speculation on food commodities is another way of exporting risk. Food price spikes cause misery and hunger for poor people yet agribusiness firm Cargill’s profits surged during the global food crisis of 2007-8 and the US drought of 2012.

And at national level, big business and local elites can manipulate markets and governments to privatise the profits and socialise the risks. Clearly big business is not always bad but it can be. In Peru, water supplies are dwindling as glaciers melt, but much is siphoned off or contaminated by mining companies, leaving local communities short of clean water.

The current response – at national and international level – is not good enough. Climate change is picking up speed, food and commodity markets are more volatile than ever, environmental degradation is increasing, and more and more people are exposed to risk – either through population growth or migration. Whilst global poverty is declining, inequality is not.

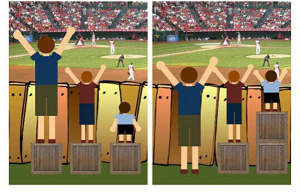

States have the legal and political responsibility to reduce the risks faced by poor people, and ensure that they are borne more evenly across society. And note that equality is NOT about everyone having the same resources and support. Disadvantaged people require more services and support simply to give them equal life chances (see pic, right).

And note that equality is NOT about everyone having the same resources and support. Disadvantaged people require more services and support simply to give them equal life chances (see pic, right).

Clearly targeted support, plus social protection, health, education – which one might call key building blocks of resilience – cost money. Brazil is bringing down its (still high) inequality through concerted efforts by the government, including major increases in the minimum wage, and social protection schemes including a universal pension and the Bolsa Familia. This is possible in part because there’s enough money – the tax-to-GDP ratio is approaching 35% in Brazil, compared to only 9-10% for Bangladesh and Pakistan. Increasing tax revenues through progressive taxation has a key role to play in redistributing risk.

In terms of the aid sector – at the risk of oversimplifying, humanitarians are good at risk, and development experts are good at power. But what we need is both. Development thinking has often been blind to the shocks, changes and uncertainties that poor people face, and naïve in assuming that development takes place in largely stable environments. Long term programmes need to internalise shocks and hazards (instead of sticking them in the risks/assumptions column of a logframe and then ignoring them) and then scale up and down as appropriate.

The newly fashionable focus on resilience can help communities not only to cope but to thrive despite the shocks and stresses, but only if the current resilience dialogue and practice is broadened out to tackle inequality, redistribute risk and stop risk dumping.

And here’s Debbie doing the increasingly obligatory video exec sum for wasters 3m piece to camera

May 20, 2013

Citizens Against Corruption: What Works? Findings from 200 projects in 53 Countries

I attended a panel + booklaunch on the theme of ‘Citizens Against Corruption’ at the ODI last week. After all the recent agonizing and self-doubt of the  results debate (‘really, do we know anything about the impact of our work? How can we be sure?’), it was refreshing to be carried away on a wave of conviction and passion. The author of the book, Pierre Landell-Mills is in no doubt – citizen action can have a massive impact in countering corruption and improving the lives of poor people, almost irrespective of the political context.

results debate (‘really, do we know anything about the impact of our work? How can we be sure?’), it was refreshing to be carried away on a wave of conviction and passion. The author of the book, Pierre Landell-Mills is in no doubt – citizen action can have a massive impact in countering corruption and improving the lives of poor people, almost irrespective of the political context.

The book captures the experience of the Partnership for Transparency Fund, set up by Pierre in 2000. It summarizes experiences from 200 case studies in 53 countries. This has included everything from using boy scouts to stop the ‘disappearance’ of textbooks in the Philippines to introducing a new code of ethics for Mongolia’s judiciary. The PTF’s model of change is really interesting. In terms of the project itself:

- Entirely demand led: it waits for civil society organizations (CSOs) to come up with proposals, and funds about one in five

- $25k + an expert: the typical project consists of a small grant, and a volunteer expert, usually a retiree from aid agencies or governments, North and South. According to Pierre ‘the clue to PTF’s success has been marrying high quality expertise with the energy and guts of young activists’. (I’ve now added ‘Grey Wonks’ to my ‘Grey Panthers’ rant on why the aid world is so bad at making the most of older people).

- The PTF is tapping into a zeitgeist of shifting global norms on corruption, epitomised by the UN Convention Against Corruption (2003). The idea that ‘they work for us’ seems to be gaining ground.

- The PTF prefers cooperation to conflict – better to work with champions within the state (and there nearly always are some, if you can find them), than just to lob rocks from the sidelines (although some rock-lobbing may also be required).

- It also prefers action and avoids funding ‘awareness-raising’, ‘capacity building’ and other ‘conference-building measures.’

So what works? On the basis of the case studies (chapters on India, Mongolia, Uganda and the Philippines), and his vast experience of governance and corruption work, Pierre sets out a ‘stylized programme’ for the kinds of CSO-led initiatives that deliver the goods:

Nail down the problem: use surveys, focus groups, right to information laws where they exist

Come up with (and implement) an action plan: get people involved with community report cards, community radio, public hearings and other approaches

Propose ideas for ways to reform the system or reduce the opportunities for corruption, drawing on the results of (1) and (2)

Discuss the ideas with stakeholders and amend

Campaign to persuade officials and politicians to adopt the ideas

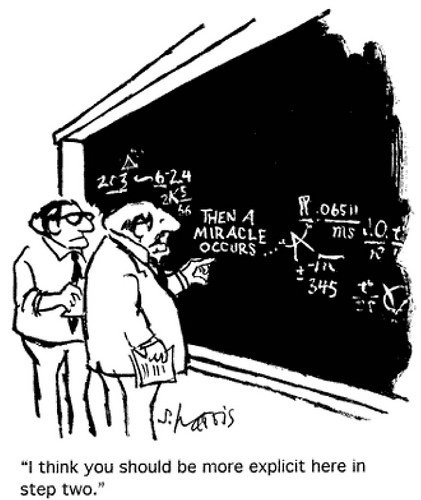

Once you’ve won (bit of a leap, that – see cartoon) monitor the implementation of any measures introduced to reduce corruption.

This may look like a bit of a blueprint, but actually it isn’t – the PTF fits the model of how to work in complex systems pretty well. It acknowledges that outsiders can’t possibly understand the labyrinths of formal and informal power, or identify potential allies and windows of opportunity. Those have to come from within. By breaking funding down into small grants, and using only volunteer experts, it tries to keep power away from the consultancy/donor complex, and stay true to being country-driven. At the ODI, Pierre described the underlying theory of change as ‘the aggregation of millions of actions to reach a tipping point.’

This may look like a bit of a blueprint, but actually it isn’t – the PTF fits the model of how to work in complex systems pretty well. It acknowledges that outsiders can’t possibly understand the labyrinths of formal and informal power, or identify potential allies and windows of opportunity. Those have to come from within. By breaking funding down into small grants, and using only volunteer experts, it tries to keep power away from the consultancy/donor complex, and stay true to being country-driven. At the ODI, Pierre described the underlying theory of change as ‘the aggregation of millions of actions to reach a tipping point.’

He also expanded on the problem of aid institutions. Anti-corruption campaigning is often long-term, over 25-50 year time horizons. That means aid donors can support particular phases, but if they don’t have the staying power to see the work through, they need to avoid trying to control it. Unfortunately, ‘politicians and officials who think they can make their mark are the biggest menace for this work’.

Despite this critique, the book is a pitch for funding from the aid agencies, although Pierre believes that in the long term CSO anti-corruption work will have to find alternatives sources.

Which all sounds great, but the results debate is obviously getting to me, because I did have some sympathy with DFID’s Mark Robinson, who said at the ODI that although the UK Government (which has been a core funder of PTF) ‘is increasingly persuaded about the value of citizens’ transparency and accountability initiatives’, we really can’t be expected to judge PTF entirely on the uplifting case studies and stats collected by, errrm, the PTF.

I raised another issue: the rhythm of civil society action is almost always episodic – long periods of tranquillity (people getting on with their lives), punctuated by episodic spikes of protest. Attempts to turn this dynamic into some kind of permanent state of mobilization are probably destined for frustration and failure. Between spikes, the long term work of renewing or changing social capital, social norms and values etc takes place in the more permanent ‘grains’ of civil society – trades unions, neighbourhood associations, religious communities – that endure between spikes. It wasn’t clear that PTF understands and works with this – it seems to have permanent mobilization as its underlying model of how civil society works.

PTF seems to belong to a family of ‘post supply side’ approaches to governance, which also includes the International Budget Partnership, the research of Matt Andrews or the Africa Power and Politics Programme, as well as Oxfam’s own work on governance and accountability.

What they have in common is the need to move from ‘best practice’ to ‘best fit’, to identify and support locally driven initiatives, and to support coalitions between champions within the system and those outside. Where they seem to differ is on the prominence of civil society in these discussions – at one end of the spectrum is PTF’s perhaps excessive glorification of its role; at the other the APPP’s rather contemptuous dismissal of civil society as irrelevant to the ‘real’ Paul Kagame world of big men and decent chaps sorting out political settlements (’citizen pressure is at best a weak factor and at worst a distraction from dealing with the main drivers of bad governance.’) I would love to see APPP’s David Booth and Pierre Landell-Mills go head to head on this.

To be continued, I suspect (not least because Matt Andrews is in London this week).

May 17, 2013

Will horror and over a thousand dead be a watershed moment for Bangladesh?

A huge and chaotic conversation over how to respond to the appalling Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh (where the death toll has now passed an unprecedented 1100) is producing some important initial results, in the form of the international ‘Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh’, launched this week.

passed an unprecedented 1100) is producing some important initial results, in the form of the international ‘Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh’, launched this week.

I got a glimpse of the background on Wednesday at a meeting of the Ethical Trading Initiative, which brings together big brand retailers, including garment companies, trades unions and INGOs like Oxfam to work on wages and conditions in company supply chains. The Accord got some pretty rave reviews – ‘absolutely historic’, said Ben Moxham of the UK Trades Union Congress; comparable to the 1911 Chicago factory fire, according to one of the big clothes retailers at the meeting.

So what does it say? The Accord covers independent safety inspections, publicly reported; mandatory repairs and renovations; a vital role for workers and trade unions, including a commitment to Bangladesh’s Tripartite Plan of Action on Fire Safety (a national initiative). A key, and controversial aspect is that the Accord will include a legally binding arbitration mechanism, which wins a lot of trust from civil society and trade unions, but has spooked a number of companies based in the litigation-tastic USA (not all though – part of Tommy Hilfiger’s in there, while Abercrombie and Fitch have said it they will join).

30 companies signed up ahead of Wednesday’s midnight deadline, including Primark, (who were buying clothes from Rana Plaza), Tesco, Sainsburys, M&S, Inditex (eg Zara), NEXT, C&A, Carrefour and PVH (part of Tommy Hilfiger). There are some holdouts – Walmart is insisting on going it alone and doing its own factory inspections, which is disappointing, not least because it is focussing on the short term problem and missing the need for longer-term coordinated political engagement. And of course, nothing legally binding there.

Given my current work focus, I fell to musing on the theory of change that underlay this apparent breakthrough. Obviously, the immediate driver is a particularly grisly ‘shock as opportunity’. But other factors worth noticing include:

The ETI’s prior existence of a forum that established a high degree of trust between traditional antagonists (companies, unions and NGOs). This allowed people to get on the phone to each other and get things moving, without first having to overcome barriers of distrust.

Prior work on some kind of accord had been going on since 2011, but had got nowhere due to lack of urgency and trust – the Rana Plaza disaster massively escalated the pressure to act.

A nascent national process (the National Action Plan for Fire Safety), that gave outsiders something to support and build on.

Energetic leadership from two new international trade unions, IndustriAll and UNI Global Union, helped get the right people in the room.

The organizers set a rather arbitrary, but very effective 15 May deadlineto prevent the response getting kicked into the long grass. A number of companies are feeling bruised by the pressure for immediate action, so there will be some fences to mend there once the Accord is up and running.

An interesting underlying challenge, reflecting my ramblings last week on change, complexity and national ownership, is how to combine the catalytic effect of a massive shock, with the need for slow, painstaking construction of new/improved institutions from within Bangladesh – the only way to ensure that whatever emerges is not just another bit of corporate spin. Peter McAllister, ETI’s Executive Director, reckons that the circle can be squared if the shock is primarily used to get all the international actors lined up behind the Accord, but that the implementation process needs to be slower and nationally owned.

An interesting underlying challenge, reflecting my ramblings last week on change, complexity and national ownership, is how to combine the catalytic effect of a massive shock, with the need for slow, painstaking construction of new/improved institutions from within Bangladesh – the only way to ensure that whatever emerges is not just another bit of corporate spin. Peter McAllister, ETI’s Executive Director, reckons that the circle can be squared if the shock is primarily used to get all the international actors lined up behind the Accord, but that the implementation process needs to be slower and nationally owned.

Next steps? The Accord lays out a 45 day period to come up with an implementation plan, involving a crucial shift from being internationally to locally driven.

The TUC’s Ben Moxham hopes the accord, and the ensuing government agreement to relax restrictions on trade unions, will help consolidate and strengthen Bangladesh’s chaotic garment workers unions (39 separate unions by his count).

Others at the meeting hope that the Accord could act as a model for both other garment exporters (Bangladesh is world number 2, after China), or for other sectors within Bangladesh – collapsing buildings are not confined to garment factories.

One last thought – in this conversation between companies, unions, NGOs and the ILO, where is the UK Government? So far pretty quiet, but you’d think that coming in behind a business-led response like this with some matching funding would be a pretty attractive ‘announceable’ for a Conservative Party minister, not least because the Accord could head off other short-term, and ultimately damaging exits like Disney, where companies stop buying from Bangladesh to protect their brand, but leave thousands of women without jobs. How about some constructive engagement, DFID?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers