Duncan Green's Blog, page 213

June 18, 2013

A great film on girls’ rights wins an international prize (and my sister in law made it)

Time for a spot of well-deserved nepotism. My sister in law, Mary Matheson, makes films for Plan International and yesterday won a prize at the Annecy International Animation Festival 2013. Chosen from more than 2000 entries, her animation “I’ll Take It From Here”, shot in Malawi last summer for Plan’s ‘Because I am a Girl’ campaign, won the UNICEF Award for best film promoting children’s rights.

Mary writes:

‘We are both daunted and thrilled to see our film in the same programme as animation giants Disney Pixar (Monsters University) and Illumination Pictures (Despicable Me 2).

It’s nerve-wracking to see our film on such a big screen, having never watched it with more than five people in the room. We have no idea what to expect from this audience of 250. But their reaction is incredible. They are mesmerised as they watch and laugh in all the right places. They even clap and cheer at the end! (I should add that they do this for most films, but hey, still it’s great to hear.)’

Luckily she says she didn’t come over all Gwyneth Paltrow, and was able to talk a bit about the campaign when she won the award. Oh, and it was her first attempt at stop motion animation. Kudos, sis-in-law.

Would that all NGO shorts were anywhere near as good as this. But all too often, they are dull, worthy, predictable, patronising and plagued by excruciating 1950s Pathe Newsreel-style voiceovers. Watch and learn, people.

June 17, 2013

Politically smart aid? Of course! Political aid? Not so sure. Guest post by Tom Carothers and Diane de Gramont

Thomas Carothers and Diane de Gramont summarize the arguments of their new book on aid and politics

Thomas Carothers and Diane de Gramont summarize the arguments of their new book on aid and politics

How political is development assistance? How political should it be? These questions provoke divergent reactions within the aid community. For some, being political means using aid to advance geopolitical interests aside from development. Others emphasize the far-reaching political consequences aid can have on recipient countries, from bolstering dubious strongmen to undermining systems of domestic accountability. These two perspectives highlight how aid’s political motivations or side effects can limit its effectiveness in advancing developmental change.

Yet in recent years many development practitioners and scholars have been arguing that aid should become more, not less, political. What do they mean by this? They are not talking about political side effects or prioritizing geostrategic motives. Rather they are referring to efforts by development aid actors intentionally and openly to think and act politically for the purpose of making aid more effective in fostering development.

As we chronicle in our new book, Development Aid Confronts Politics: The Almost Revolution, donors have increasingly incorporated politics into their work in two major ways. First, they now pursue explicit political goals in developing countries, whether expressed as advancing democracy, democratic governance, or effective governance. Second, they are trying to adopt politically smart methods, moving away from the idea of aid as a narrowly technical input to considering it a facilitating agent of local processes of change, which requires aid providers to conduct political analyses, adapt programs to local political contexts, and reach a diverse range of socio-political actors within developing countries.

On the face of it, political goals appear to have advanced farther than politically smart methods. All major bilateral and multilateral donors now formally embrace political goals of one sort or another and together spend around $10 billion a year on political aid programs broadly defined. Advocates of politically smart methods, on the other hand, often feel like they are fighting for a foothold within their organizations. Political economy analysis is still far from a regular part of program planning processes and the bureaucratic structures of aid agencies tend to hinder flexible, politically savvy programming.

Nevertheless, in presenting our book at aid agencies, think tanks, and universities in Europe and the United States, we have been struck by how much  more receptive many people are to the idea of politically smart methods than political goals. Some listeners are at first uncomfortable with our use of the term political methods, but when we say that we mean politically smart development, most heads nod. It is hard to argue against basing programs on solid political understanding and context-specific implementation. Political goals like democratic governance, on the other hand, still engender considerable skepticism even though they have been part of the aid agenda for two decades now.

more receptive many people are to the idea of politically smart methods than political goals. Some listeners are at first uncomfortable with our use of the term political methods, but when we say that we mean politically smart development, most heads nod. It is hard to argue against basing programs on solid political understanding and context-specific implementation. Political goals like democratic governance, on the other hand, still engender considerable skepticism even though they have been part of the aid agenda for two decades now.

Owen Barder of the Center for Global Development summarized this perspective well in his comments on our book at an Overseas Development Institute event. He noted the distinction between politically smart methods and political goals and said that “it seems to me that there should be nobody left who doesn’t think we should be doing the first of those. You would be insane to think how do we get better teaching in schools without thinking about the power of the teacher’s union or the role of the Ministry of Education.”[1] But he also argued that there is less evidence that donors know how to change power relations in developing countries and “if we don’t know how to do that, why would we want to take money from something we do know how to do, which helps people live better lives, and spend it on something that we are not sure is going to work?”[2]

Owen’s question is a good one, and it was repeated in different forms at many of the presentations we gave. So can donors adopt politically smart methods without bothering with political goals? It is an appealing idea. Trying to engender political change in developing countries is difficult and many aid interventions in this area have fallen short of their goals. Moreover, sharp debates persist both in scholarly and practitioner circles about the value of democratic governance for socioeconomic change. Scholars such as Acemoglu and Robinson make the case for the developmental value of inclusive institutions but others point to the developmental success of not just China but also authoritarian regimes in Ethiopia and Rwanda as evidence against the democratic governance consensus.

Given this lack of consensus, why not just focus on politically smart approaches to delivering the socio-economic goods we know (or at least hope) that aid programs can do well, from vaccines to food assistance to road building?

We don’t think donors can—or should—step away from political goals that easily. The initial embrace of governance by development agencies was driven by frustration with the persistent failures of aid in badly governed countries and the important insight that in many contexts sustained development progress will remain out of reach without governance progress. If donors are to be more than indefinite service providers in poor countries, they need to pay attention to building effective institutions, which ultimately translates into political goals.

Furthermore, development aid is always going to have an effect on power relations and involve political choices and values. Whoever controls foreign aid resources gains power as a result, meaning for example that choices about directing aid through governments versus through local civil society are fraught with political implications.

Embracing politically smart methods but avoiding political goals can lead donors down a troubling road. If a political analysis reveals that the easiest way to get a donor-supported economic policy reform in place is by encouraging the president to adopt it through decree rather than legislative action and citizen consultation, is that the right way to go? The only way to answer such a question is by reference to political values, and behind those values lie political goals, such as inclusive and transparent governance.

None of this means that development aid can or should be the primary mover of political change in recipient countries. There should be vigorous debate around the contribution and limits of donor efforts to promote better governance in developing countries. But the idea that donors can draw a sharp line between politically smart aid and the pursuit of political goals is an illusion, an updated version of technocratic temptations of decades past.

[1] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZK9S3vqJMZU, 35:30

June 12, 2013

Off on holiday, so here’s a Dilbert

Off on holiday in Wales this week, luxuriating in near tropical conditions (no harm in dreaming). Here’s an oldie-but-goodie Dilbert to keep you amused til I’m back.

June 11, 2013

What kind of science do we need for the aid and post-2015 agenda?

Spent an intriguing evening last week speaking on a panel at the wonderful Royal Society (Isaac Newton and all that), on the links between the post-2015 agenda and science. The audience was from the government/science interface – people with job titles like ‘Head of Extreme Events’.

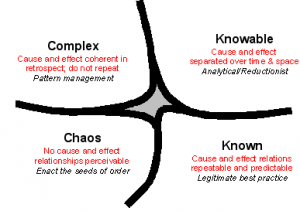

I talked (powerpoint here – keep clicking) about how science can help developmentistas by bringing them up to date with what science is actually about. Less Newton more Darwin, in terms of moving from a 19th Century world of linear causal chains, static equilibria and reductionism, to ecological and complexity thinking. I also tried linking some of the stuff I’ve been reading on complexity thinking with the Cynefin framework. It seems to me we need different kinds of science for the different quadrants:

about. Less Newton more Darwin, in terms of moving from a 19th Century world of linear causal chains, static equilibria and reductionism, to ecological and complexity thinking. I also tried linking some of the stuff I’ve been reading on complexity thinking with the Cynefin framework. It seems to me we need different kinds of science for the different quadrants:

Complex: complexity theory, evolutionary/ecological approaches

Knowable but complicated: more traditional analytic research methods aimed at nailing down causation

Known: Just identify and roll out best practice

Chaos: no idea – any suggestions?

The reason I like this is that it helps clarify when we need to bash our brains on complexity theory, and when we can stick with the old fashioned stuff. Convinced?

My other point was to stress that science has to address issues of power and distributive impact – issues like intellectual property rights and the current efforts to restrict poor countries’ access to medicines, but also the impact of new technologies. Geoengineering seemed to resonate as an example: it’s no good thinking about it as a purely technological challenge, you also have to think about winners and losers from its implementation (if they dump a million tonnes of iron filings in the oceans to absorb carbon, it isn’t going to be off the shores of Europe…..).

But enough about me, what did other people say? David Cameron’s post-2015 czar, Michael Anderson, was strikingly interested in complexity and uncertainty – a theme which dominated the evening. He stressed the political obstacles to taking them seriously – politicians don’t want to know; the public switches channel. Correcting that needs an educational effort from scientists, but also finding good ‘proxy indicators.’

Wrong model, guys

Proxy indicators are magical: they take the temperature of a complex system well enough to be useful, and they communicate directly with policy makers and public. According to Michael, the maternal mortality rate is the perfect example – an excellent proxy indicator for the overall state of health systems and a powerful means of communicating with a wider audience. Michael reckons we need such ‘canary in the mine’ indicators to help tackle complex processes such as climate change, conflict or the sustainability of oceans (apparently phytoplankton levels are the best guide to ocean health, but don’t cut it with Joe Public, so they went for fish stocks in the High Level Panel report).

The overall discussion on the role of science was a bit all over the place – I guess ‘Science’ is a very big thing. Perceptions of science are deeply split: policy-makers see it as a source of certainty – ‘what works’, ‘this we know’, ‘facts’ – that they can cling to in their daily swirling clouds of opinion and ideology. But scientists don’t agree – they are much more aware of the limitations of scientific knowledge and the messiness of the world.

Some of the conversation was more about the downstream application of science to implement policies and achieve whatever goals are agreed. For Ban Ki-Moon’s post-2015 special adviser Amina Mohammed, the issues were building scientific capacity in developing countries (entirely missing from the MDGs), linking science-blind parliaments and politicians with nascent scientific communities, and dealing with slow/bad data.

Over dinner (Chatham House rules), multi-disciplinarity got a hostile reception – people reckoned that sometimes you need a single discipline, sometimes a combo – it depends. Better, perhaps to try and adopt a ‘problem driven approach’. Identify the problem, and then see which disciplines jump to the task – shades of Matt Andrews’ ‘problem driven iterative adaptation’ again.

The conversation got heated (appropriately) on climate change, with scientists laying into the civil servants about the necessity of at least discussing the implications for growth (‘growth is exponential; the planet is finite – it doesn’t add up’), and the civil servants wearily explaining the nature of political realities – you can’t question the primacy of growth and keep your job.

And one lovely quote from Isaac Newton himself, nicked from Ben Ramalingam’s forthcoming book Aid on the Edge of Chaos: ‘I can calculate the movements of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of men.’ True that, judging by an evening with the boffins.

June 9, 2013

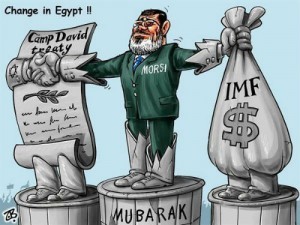

Dancing on hot sand: Egypt and the IMF loan

Dr

Mohga Kamal-Yanni

is Oxfam’s

Senior health & HIV policy adviser, and works on financing for development, including how powerful institutions influence developing countries policies. As an Egyptian, she is also passionate about ‘the revolutionaries who opened the door for the power of the youth to change the world for the better.’

influence developing countries policies. As an Egyptian, she is also passionate about ‘the revolutionaries who opened the door for the power of the youth to change the world for the better.’

As summer approaches in Egypt, people worry about endless hot days with electricity cuts. Fridges in Egypt are not a luxury. Cooling water takes a major part of fridge space in a low/middle class homes. Loaves of bread packed onto fridge shelves save the family from daily queues.

Last year, when people complained about electricity cuts at the sweltering height of summer, the Egyptian Prime Minister, Hesham Qandil, advised them to wear cotton clothes and run only one air conditioner in a single room to save electricity. The advice was not popular, especially with those living in crowded accommodation with perhaps one fan, or with students who cannot study for their exams in the dark.

Today, Egypt is facing another fuel crisis, with vehicles queuing for hours and sometimes days outside petrol and diesel stations. The reasons for the crisis are multifaceted, but according to the IMF, Egypt’s economy is on the brink of collapse with a mounting budget deficit and diminishing foreign currency reserves – necessary to buy basic goods such as wheat and fuel. This has been the IMF message since 2011, when the then military council declined a loan.

Last year the civilian government requested an even bigger loan from the IMF ($4.8 billion instead of $3.2 billion offered in 2011). The loan raised public debate on whether Egypt needed the loan given the government’s lack of clear and transparent economic policies . Now the IMF and government are back at the negotiating table for another go. Just before the World Bank/IMF spring meeting this year, an IMF mission returned from 2 weeks’ negotiations with the government in Cairo. Its press release stated that there was ‘progress’ – yet no indication of the extent or shape of such progress. At the spring meetings several IMF and civil society panels discussed the loan and government officials had further behind-the-scene discussions with the IMF – another press statement added that “further progress was made”.

The public and official debate centres on the loan and its “conditionalities”, even though there is such a lack of information that the question arises ‘conditions on what?’. While the Egyptian public has had clear goals since January 2011 uprising (bread, freedom, social justice), the government has not proposed an economic plan to achieve them.

The lack of clear economic vision is causing public confusion over whether Egypt needs a loan at all and if so, how the loan contributes to achieving the objectives of an Egyptian economic plan. The loan itself will not solve Egypt’s deficit problems, let alone stimulate economic growth. Its role is unclear apart from opening the door for more loans from other bilateral and multilateral institutions. Many Egyptians fear that the loan will just lead to deeper debts without generating the jobs and economic growth necessary to repay the debt and achieve societal goals.

The IMF does not seem to be interested in offering technical or policy assistance to the government to develop such an economic vision. Instead, it narrowly focuses on three economic measures: removing fuel subsidies, increasing the General Sales Tax (GST), and floating the pound, despite the clear signs of unrest among ordinary Egyptians as they have already started to suffer the impact of the fuel crisis.

There seems to be a lack of understanding of the importance of diesel in agriculture, small businesses and the local transport of goods and people. Any rise in the price of diesel will be transferred to consumers and thus increase the cost of living and hinder attempts at economic recovery. Moreover, the IMF thinks that poor people will escape the impact of a rise in GST because of the exemption of food and small businesses. Yet this ignores the fact that GST on agriculture inputs will be passed on into the price to food products. Also small businesses buy their inputs from bigger businesses, which pay GST.

And other ways to improve the fiscal and economic situation are not being taken seriously by either the government or the IMF. Civil society and academics have proposed measures such as progressive taxation, taxing the stock exchange, or removing fuel subsidies for rich people and energy-intensive industry. The IMF’s typical answer is that these measures would take time and not raise sufficient revenue. Yet elsewhere, the IMF itself has advocated for the removal of wasteful and regressive fossil fuels subsidies that benefit higher-income consumers, with corresponding social protection measures in place for the most vulnerable.

What is frustrating for civil society is the lack of transparency and information on the government economic plans or details of this and other loans. The debate relies on leaked information, the experience of other IMF loans and policies in Egypt and in other countries and the little revealed in the media.

The IMF will presumably post the loan document on its website once the board approves it, but by that time it is a fait accompli and the public and civil society will be powerless to amend the deal.

If the IMF seriously wants to help Egypt, then it should:

Help the government to develop a transparent economic plan for 3-5 years with clear goals, actions and costs. The plan should focus on fiscal and economic measures that target the rich side of society and protect ordinary Egyptians from the implementation of unfair austerity measures

Be much more transparent (along with the Egyptian Government) about the details of economic measures and loan conditionalities

Encourage the government to study alternative ways to address the fiscal crisis and stimulate economic recovery in the short term and economic growth in the medium term

June 7, 2013

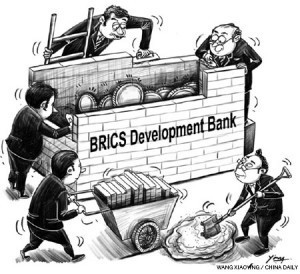

The BRICS Bank gathers momentum: another sign of the world’s shifting power balance

The momentum behind the creation of a new international bank by the BRICS countries seems to be building steadily. Its leaders will review progress on the BRICS Bank at a special BRICS summit in the sidelines of the St Petersburg G20 Summit in early September. They expect to finalise plans for the Bank at the Sixth official BRICS Summit in Brazil in early 2014.

the BRICS Bank at a special BRICS summit in the sidelines of the St Petersburg G20 Summit in early September. They expect to finalise plans for the Bank at the Sixth official BRICS Summit in Brazil in early 2014.

And there seems to be serious money on the table. There is agreement on the initial capital (US$50bn with 20% up front in cash and guarantees for the other 80%). That means it could rapidly become a major player – possibly the player – in development financing. China’s ExIm Bank and Brazil’s BNDES already each lend more to developing countries than the World Bank. It is not inconceivable that the BRICS Bank will soon overtake them. One possible (much smaller) model suggested by Brazilian officials is the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF).

The focus will be “infrastructure and sustainable development” – infrastructure has long been a bugbear of developing countries, who have complained that one unintended side effect of the MDGs (as well as pesky environmentalists) is to divert too much funding away from roads, electricity etc into schools and hospitals. It remains to be seen whether ‘sustainable development’ will in practice play second fiddle to infrastructure, and what the Bank means by the notoriously slippery term.

The political drivers behind the creation of the Bank are a combination of growing BRICS economic power and assertiveness and frustration with the slow pace of reform (eg over voting rights) in the World Bank and IMF, plus the lack of growth in their volume of lending.

The BRICS countries are keen to stress that the new funder will (initially at least) be complementary to the existing financial institutions, but If the BRICS continue their rise, their bank could one day eclipse the Washington-based financial institutions. Down the line, the Bank could well expand to other developing and developed countries, but the BRICS are likely to insist on retaining a controlling voice.

There are still lots of details to thrash out, including who contributes what, and whether voting shares should be proportional to contribution, or equally distributed among the BRICS.

And a lot of the issues that traditionally concern NGOs aren’t even on the table yet – environmental and social safeguards, participation, transparency, social accountability. It’s not yet clear whether the Bank will pick these up (as the Brazilians are likely to insist), or whether they say ‘nah, that’s all World Bank nonsense, we’re just going to get on with knocking stuff down and building new things in its place.’ The citizens whose taxes are actually paying for the Bank may have something to say about that.

And a lot of the issues that traditionally concern NGOs aren’t even on the table yet – environmental and social safeguards, participation, transparency, social accountability. It’s not yet clear whether the Bank will pick these up (as the Brazilians are likely to insist), or whether they say ‘nah, that’s all World Bank nonsense, we’re just going to get on with knocking stuff down and building new things in its place.’ The citizens whose taxes are actually paying for the Bank may have something to say about that.

How much influence is the Bank likely to have in the long run? Nobody knows, but it will be fascinating to watch – will it challenge the Washington ‘intellectual-financial complex’ and inject greater pluralism in debates on the role of international finance, industrial policy etc? And if it does, will the result help or harm people living in poverty? Interesting times.

More background here

And if you’re in the UK, there’s a panel discussion on the BRICS Bank, showcasing some new IDS research, in the House of Commons on 11 June. Details here

June 6, 2013

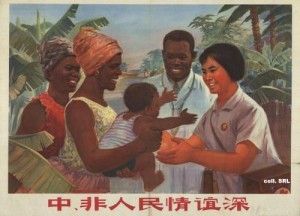

What do African civil society organizations think of the rise of China and South-South cooperation?

The Belgian NGO coalition 11.11.11 has published an interesting paper summarizing the views of 58 African civil society organizations in 11 different countries on ‘South South Cooperation’ (SSC) – mainly China’s growing role in Africa (see Economist stats, right – keep clicking to expand). It’s nuanced and an excellent counterweight to the simplifications of the ‘scramble for Africa’ diatribes in the Western press, which Deborah Brautigam gets so exercised about. Some highlights:

countries on ‘South South Cooperation’ (SSC) – mainly China’s growing role in Africa (see Economist stats, right – keep clicking to expand). It’s nuanced and an excellent counterweight to the simplifications of the ‘scramble for Africa’ diatribes in the Western press, which Deborah Brautigam gets so exercised about. Some highlights:

Discourse [this is a Belgian NGO, after all]: ‘CSO representatives voiced a clear positive appreciation of the rationale and core principles of SSC. This does not mean they were ‘fooled by a shiny wrapping’. On the contrary, they also expressed doubts about whether and how the discourse will be put into practice, especially since the observance of the key principles relies solely on self-compliance by emerging powers.

They pointed out that acting as equals was difficult when one party was a low income country and the other the world’s second biggest economy. They mentioned many examples of ‘win-win’ that did not mean equal benefits.

Yet they indicated that the framing of SSC gave a wholly different ‘feel’ to the cooperation. They appreciated the straightforwardness of emerging powers and the notion of reciprocity being embedded in the cooperation, especially when contrasted with the rhetoric in North-South Cooperation, which they experienced as patronising and often hypocritical.

The emphasis on respect for national sovereignty and ownership triggered particularly interesting reactions. CSOs explicitly voiced their support for the principle of non-interference and considered it to be a true asset of SSC. Yet, they also feared that the lack of conditionality would undermine the fight for good governance, democracy and respect for human rights.

This ambiguous position is partially explained by (1) bad experiences with political conditionality imposed by [northern] DAC-donors, (2) not automatically equating non-interference with the absence of political conditionality, and (3) having different expectations towards different donors, in the hopes of benefitting from complementarity.

This ambiguous position is partially explained by (1) bad experiences with political conditionality imposed by [northern] DAC-donors, (2) not automatically equating non-interference with the absence of political conditionality, and (3) having different expectations towards different donors, in the hopes of benefitting from complementarity.

The support for non-interference or non-conditionality in SSC should not automatically be interpreted as support for a radical shift towards non-conditionality in North-South Cooperation but does show the debate on political conditionality is overdue.

The often nuanced views and ambiguous arguments illustrate a wait-and-see attitude: emerging powers may talk the talk, but will they walk the walk?

Impact: There is some consensus on the pros and cons of SSC. Looking on the bright side, CSOs applauded the BICS [Russia apparently doesn’t count] for scaling up their cooperation with Africa while DAC-donor budgets are under pressure. In particular the BICS’ fast and cost-effective contributions to basic infrastructure, technology transfer, telecommunication and access to scholarships were highlighted.

Another often-mentioned advantage was the improved access to affordable consumer products, from textiles and shoes to affordable medical products and agricultural equipment. All in all, the BICS were valued for their quick delivery, and as a source of inspiration and expertise for tried and tested responses to development challenges.

However, in the same breath, participating CSO representatives flagged a number of clear downsides. Their number one concern was SSC’s toll on local economies. Lower prices and widespread corruption enable Chinese, Indian and South African companies to undercut local producers and suppliers, forcing them out of the market. CSO representatives didn’t feel this was compensated by gains in local employment, because of substandard working conditions, especially in Chinese companies, and the alleged import of workers.

According to them, the competition caused by SSC was even being felt in the informal economy, e.g. via Chinese street vendors. Local producers and workers were often considered worse off, but the gains for consumers were also put into question. The satisfaction with the improved access to affordable consumer products was countered by many complaints about the quality of the (Chinese) products, which according to CSO representatives were a safety hazard and a danger to public health. Several interviewees feared the rise of xenophobia (read: Sinophobia) and even violence against immigrants from emerging powers in the long run.

Additional drawbacks in the economic domain were the possibly exploitative natural resource deals with some emerging powers and the lack of corporate social and environmental responsibility by companies from emerging powers.

corporate social and environmental responsibility by companies from emerging powers.

In the political domain, participating CSO representatives valued the emerging powers and SSC as a mitigating factor in skewed international power relations. Yet, they also feared the consequences of increased rivalry between the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ powers, or of the competition between North-South Cooperation and South-South Cooperation. They feared that their alliance with one side would damage the relations with the other side: ‘If two elephants fight, the grass suffers.’

In national politics, participating CSOs feared that with no conditions attached, SSC undercuts the fight against corruption and for human rights and the efforts to improve leadership accountability.

CSO Involvement: Civil society is only by exception involved in the practice of emerging powers’ SSC (in contrast to private and state actors). Looking ahead, CSOs were convinced that civil society has an important role to play, both as watchdogs signalling negative side effects of South-South cooperation, and as facilitators in the implementation of SSC. They also identified the lack of transparency and the exclusive character of SSC as major obstacles to that ambition. CSOs strongly felt that coalitions with CSOs in emerging powers could provide them with the leverage to ‘break open’ SSC.’

June 5, 2013

Which rich countries are good/bad on hunger and nutrition? A new index takes aim at the donors.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the new Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index of developing countries. Yesterday, IDS published a second HANCI for the donor countries. The Index assesses governments on both their promises and performance, strokes the good guys and slaps the bad, provides arguments and data for civil society and scrutinizes aid levels.

Some of the things I liked: it combines the aid agenda with what countries do closer to home (domestic action on climate change, biofuels, and farm policies – but not, as far as I can tell, action to curb land grabs); it looks at both stated policies and how much cash governments spend.

It tackles hunger and nutrition separately, because ‘Undernutrition is not only a consequence of hunger, but can also exist in the absence of hunger, and can be caused by non-food factors. Undernutrition results from both a critical lack of nutrients in people’s diets and a weakened immune system. In a vicious cycle, poor nutritional intake can make people more susceptible to infectious diseases whilst exposure to disease can lower people’s appetite and nutrient absorption. Undernutrition in the first 1000 days of a child’s life (from conception until the age of two) has lifelong and largely irreversible impacts because it impairs a child’s physical and mental development.’

So (tadaa!) here’s the index (apologies for the slightly OTT infographic).

And yep, the UK comes top, largely due to its policy, programmes and legal indicators – spending is more patchy. This is potentially a bit tricky for IDS, as DFID funded the research, along with Irish Aid (Ireland came 5th/23), but the report tries not to gush too much, and has plenty of caveats about where these countries could do better (and acknowledges the funding up front).

Other things to note – Canada comes second because, among other things, of ‘delivering on its greenhouse gas emissions pledges’. But if my recent visit to Canada was anything to go by, it looks about to plummet down the table, as the Harper government takes a bludgeon to the aid system and reneges on climate change commitments.

The US comes in a pretty pitiful 18/23, mainly due to its relatively low spending on hunger reduction and nutrition programmes in relation to its GDP. It is also less likely than many other OECD countries to sign up to international treaties and frameworks.

The value of the index will really grow in future years, as a time series develops and allows NGOs and others to praise progress and denounce backsliders (looking at you, Ottawa). Let’s hope governments are listening.

June 4, 2013

When/how does aid help Africa’s public services work better?

I seem to be spending most of my life at the ODI at the moment, largely because it is producing an apparently endless stream of really useful research papers and seminars. Yesterday saw a combo of the two, as it launched Unblocking Results: using aid to address governance constraints in public service delivery (OK, maybe it still has a thing or two to learn about snappy titles…..).

papers and seminars. Yesterday saw a combo of the two, as it launched Unblocking Results: using aid to address governance constraints in public service delivery (OK, maybe it still has a thing or two to learn about snappy titles…..).

The starting point for the work is that while there is a vast amount of research on the role of institutions in delivering (or failing to deliver) health, education, water etc, there is very little on the role of aid agencies when things go well. So ODI carried out a positive deviance exercise, identifying 4 success stories out of 60 initial candidates, and then delving into the reasons behind the success.

They were a rural water programme in Tanzania, a pay and attendance monitoring programme in Sierra Leone, support for the government Strategy and Policy Unit, also in Sierra Leone, and a local government programme in Uganda.

According to the report, ‘Six factors seem critical in this regard and provide clear implications for the design and implementation of aid packages that seek to address service delivery blockages. Apart from the first (windows of opportunity), they are all within the control of external partners to pursue. However, in most cases, they would also require considerable deviation from current practice.’

The six, complete with natty graphic (right) are:

Identifying and seizing windows of opportunity: plenty of overlap with my own work on shocks as drivers of change. The authors described what I now call WoOs (sorry) as the most significant common factor behind the success stories. But it’s not just a question of waiting around for a shock – prior relationships, trust and knowledge are crucial to being able to seize WoOs, as is a ready source of at least limited funding.

Focusing on reforms with tangible political pay-offs: governments listen to aid agencies when they help deliver ‘tangible goods and services that politicians could capitalise on in their campaigns.’ i.e. unless you align political self-interest with governance reform, you can forget it.

Building on what exists to implement legal mandates: concentrate on the implementation gaps that already exist, rather than rewriting current rules and laws, even if that means accepting the reviled ‘second best solutions.’

Moving beyond reliance on policy dialogue: Building on the previous point, ‘[successful] aid packages seem to focus on ‘getting things working’ rather than perfecting the framework (through the development of laws, procedures, regulations, policy processes).’ Nuts and bolts, not endless seminars.

Facilitating problem solving and local collective action solutions: yep, it’s our old friend, convening and brokering. One speaker worried about a ‘scramble to convene and broker’, which could make the per diem culture of East Africa and elsewhere look like a garden party.

Adaptation by learning: ‘Aid packages benefit from in-built flexibility that allows for regular programme adjustment based on learning and changes in the local context.’

If this sounds familiar, it’s because it is – it echoes work by Matt Andrews, the Africa Power and Politics Programme, and a lot of the stuff on ‘how change happens’ on this blog. Sue Unsworth reckons we are reaching some kind of ‘critical mass’ of research findings. Rebecca Simson of ODI helpfully summarized the so what’s for donors in this table (it’s not in the report, but Matt Andrews wisely advised them that unless they can offer a table of so whats, the donors won’t listen).

But does that mean donors are going to start adopting the lessons of such success? The obstacles in terms of ideas, institutions and incentives, are high. One useful suggestion from the seminar was to apply the same positive deviance approach to the donors – where do donors depart from standard practice and pursue enlightened approaches to governance reform, and why? As Ros Eyben has shown, an awful lot of these success stories seem to boil down to stubborn individuals in the aid sector, willing to ride the two horses of satisfying the demands of logframe/results-based aid, while operating in the real world of messy, make-it-up-as-you-go-along innovation, (however painful the result). Oh good, needs more research……

June 3, 2013

Will the Post-2015 report make a difference? Depends what happens next

An edited version of this piece, written with Stephen Hale, appeared on the Guardian Poverty Matters site on Friday

Reading the report of the High Level Panel induces a sense of giddy optimism. It is a manifesto for a (much) better world, taking the best of the Millennium Development Goals, and adding what we have learned in the intervening years – the importance of social protection, sustainability, ending conflict, tackling the deepest pockets of poverty, even obesity (rapidly rising in many poor countries). It has a big idea (consigning absolute poverty to the history books) and is on occasion brave (in the Sir Humphrey sense) for example in its commitment to women’s rights, including ending child marriage and violence against women, and guaranteeing universal sexual and reproductive health rights.

Millennium Development Goals, and adding what we have learned in the intervening years – the importance of social protection, sustainability, ending conflict, tackling the deepest pockets of poverty, even obesity (rapidly rising in many poor countries). It has a big idea (consigning absolute poverty to the history books) and is on occasion brave (in the Sir Humphrey sense) for example in its commitment to women’s rights, including ending child marriage and violence against women, and guaranteeing universal sexual and reproductive health rights.

The ambition and optimism is all the more welcome for its contrast with the daily grind of austerity, recession and international paralysis (Syria, Climate Change, the torments of the European Union). In response, the report is clearly designed for a no/low cost environment, downplaying the importance of aid, talking up access to data, and revenue raisers like cracking down on tax evasion.

But then the doubts start to creep in. What’s missing is always harder to spot than what is in the text, but three gaps are already clear: The emerging global concern over inequality is relegated to national politics, and otherwise dealt with through the ‘data default’ of requiring any target to be met amongst the poorest fifth of a population, not just the population as a whole. The concept of poverty is pretty old school – income, health, education, and fails to recognize the considerable progress made in measuring ‘well-being’ – the level of life satisfaction people feel. Finally there is too little recognition that the earth is a finite ecosystem, and that we need to make a reality of the concept of planetary boundaries if we are to sustain progress in tackling poverty.

But the elephant in the room is not the text, but how this text will or will not connect to the struggles to achieve the many very laudable aims set out in the report.

Five or 10 years down the line, will the High Level Panel report be food for termites, or a watershed in human development? The shelves of international bodies are piled high with forgotten reports by distinguished panels. Do any readers remember the 2012 High-Level Panel on Global Sustainability or the UN High Level Advisory Group on Climate Financing? Thought not.

These reports sank because they failed to connect with more permanent international processes and did not tackle the critical underlying issues of power and politics that determine what good ideas make it into policy, and what are ignored.

thanks guys, now what?

Here the HLP report risks going the same way. It is written in the name of an imaginary ‘we’ (as in ‘it is crucial that we ensure basic safety and justice for all’), ignoring the reality that ‘we’ may not all want the same thing (which is why we need politics, after all).

The post2015 process could have lasting influence in four main ways: Firstly, making the case for improving the quality or quantity of aid (the major achievement of the MDGs). The HLP report does pretty well on that, as you would expect.

Second, international agreements can be effective in triggering long-term, under-the-radar changes in public norms and values. This is more subtle, but very important – research is piling up to show that international conventions to end discrimination against women, or on the rights of children, have permeated people’s heads (and national laws) in many countries, changing in fundamental ways, perceptions of what it is to be a woman or a child. It is very unlikely indeed that this report will have that effect, but it’s still possible if there is sufficient pressure.

That brings us to a third pathway to impact: directly exerting traction on national governments. Will the post2015 process persuade national governments to do things differently, for example by creating a ‘race to the top’ between governments, highlighting the heroes and zeroes (like the World Bank’s Doing Business rankings). Promisingly, the report urges regional reports and peer reviews – nothing annoys a leader (or wins press coverage) like being trounced by a neighbour in a league table.

Finally, the post2015 process could create stronger and broader alliances of civil society organizations, trade unions, faith institutions and others who take whatever comes out of the process and use it to put pressure on their governments, as they have done with some of the ILO conventions, or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The report now enters the treacherous waters of a ‘UN Open Working Group’. With two and a half years before the MDGs deadline, the task of those concerned with development should now be to defend the good stuff in the HLP report from dilution, while focussing far more strongly on how a new set of global goals can lead to lasting change at national level.

The report’s publication inevitably triggered an avalanche of opinion pieces. The ones I liked included Charles Kenny, a round up of reactions by Global Dashboard and (of course) Claire Melamed. Any others stand out?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers