Duncan Green's Blog, page 217

April 18, 2013

FP2P greatest hits: top posts & comments by theme (ag, inequality, results, education etc) now available

Oh boy, I have a greatest hits album. This blog was launched back in 2008 to help promote the first edition of From Poverty to Power, but rapidly

Easily confused.....

acquired an identity and readership of its own. I reckon there’s about half a million words or so up there now, and some of them have to be worth reading (monkeys, typewriters etc). So my long-suffering colleagues Sarah Minty read the lot, and grouped together relevant posts under categories such as Agriculture, Climate Change, Inequality, or Monitoring, Evaluation & Learning. The links take you through both to posts and (just as important) comments.

Pdf with links to posts in all categories here.

Some categories are not currently included, but probably should be:

Posts that stoked most controversy within Oxfam (example)

Videos that my nephews and nieces enjoyed (example)

Funnies (example)

The pubs team made a special effort to get this out for next week’s Politics of Evidence conference, as January’s big debate between Ros Eyben, Chris Roche, Chris Whitty and Stefan Dercon (plus dozens of highly qualified commenters) on this topic has proved particularly popular with students, academics and practitioners.

Any suggestions for further refining the categories are of course, welcome.

April 17, 2013

Land Grabs: the Coldplay version

Monday’s post had Rob Nash arguing that the World Bank has got itself into a tangle on land grabs. Now Coldplay have decided to add their rather more harmonious voice, with the help of crowd-sourced footage from 7000 supporters in 55 countries.

The Bank has promptly responded to Coldplay (not to Rob, sorry Rob) with a tweet ‘@WorldBank: .@coldplay protecting the rights of farmers worldwide is key to ending poverty. Learn more abt work on this front: http://ow.ly/hs448‘. So at least now, we have their attention.

I’d be interested in your views on this kind of popular/cultural campaigning.

April 16, 2013

Why has economic crisis produced a new left in Latin America, but not elsewhere?

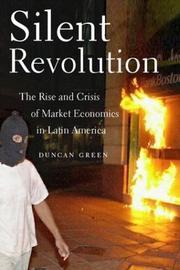

For a wonk parent it’s hard to beat the heart-warming experience of seeing your book referenced in your son’s university essay. In this case, junior had the task of trying to understand the link between neoliberalism and the rise of a new left in Latin America, so he cited Silent Revolution, a book I first published in 1995, when he was 3 years old.

the task of trying to understand the link between neoliberalism and the rise of a new left in Latin America, so he cited Silent Revolution, a book I first published in 1995, when he was 3 years old.

But his essay also got me thinking. Citing Polanyi, he put the rise of Chavez, Morales, Lula et al down to the ‘commodification’ of land, labour and money. Through privatization, deregulation etc, the Washington consensus over-reached itself, trying to commodify things like jobs that have much deeper human significance than just being tradable items. That provoked the backlash that became Latin America’s centre left, while simultaneously undermining the unions that were the backbone of the previous ‘old left’.

Nice thesis, but surely if that was true, the centre left would be much more of a global phenomenon, given that commodification is hardly confined to Latin America? So what, specifically, about Latin America has led to the rise of such an interesting range of political movements and governments over the last 15 years? Candidates include:

- The depth of prior trauma from hyperinflation meant that people were less willing to go for slightly friendlier variants of neoliberalism and ready to pursue more radical solutions

- Disillusion with more orthodox forms of ‘bourgeois democracy’ because in Latin America, the return to democracy from military rule coincided with the debt crisis and economic stagnation of the 1980s

- The particular depth of progressive social capital: the radical Catholic Church, the fight back against military rule, the rise of identity movements (indigenous, black, women) created new political expressions outside the previous structures

- The concept of ’social debt’ – the new left successfully argued that the legacy of military rule was a degree of inequality that was unacceptable, and they won that argument even with the middle classes. As a result, Latin America is the one region in the world where inequality has been falling.

Hold on, what's HE doing there?

And of course, (sorry, son) it’s very dangerous to generalize about the whole region (even in an undergraduate essay). For a start, there are at least two ‘new lefts’: a more social democrat ’sensibilist’ left, epitomised by the PT under Lula, and the more fire-breathing ‘Bolivarian’ left of Morales, Chavez and friends (see left). One reason why Venezuela and Bolivia were able to depart further from the Washington Consensus was at least partly because they were enjoying massive oil and gas royalties, so felt much freer of fiscal constraints. Brazil, traumatized by memories of hyperinflation, pursued a different combination of radical social policy and cautious economic policy. Argentina, as always, is a special case, buying itself fiscal space by defaulting on its debts after the 2000 meltdown, but is now having trouble maintaining it (and the Peronists are virtually indestructible, and have so far headed off any new political challenges).

Not that Silent Revolution is much help in understanding all this. One painful aspect of being an author is that your thinking is captured at a fixed point, even as time moves on. The first edition in 1995 lamented the Latin American left’s inability to move from ‘protesta a propuesta’ (protest to proposal). The second edition in 2003 saw much more evidence of a crisis in the prevailing paradigm, but failed to find any clear signs of what was emerging. Oops.

Any other thoughts on the origins of Latin American exceptionalism? (Don’t worry, junior’s already handed in his essay, so he can’t be accused of crowdsourcing.)

April 15, 2013

Does the World Bank speak with forked tongue on Land Grabs?

Rob Nash, Oxfam’s Private Sector policy adviser, finds a deep contradiction in the way the World Bank talks (and acts) about land

Last week I was at the World Bank’s Land and Poverty Conference in Washington DC, sitting in one of the most luxuriously appointed office buildings I have ever seen, (and I used to work for Lehman Brothers), as we discussed the land issues that so critically affect many of the poorest people on our planet.

This week, this fine setting will play host to the annual Spring Meetings of the World Bank Group, where land issues will also be a big focus for many of the assembled policymakers, academics, NGOs and private sector investors.

Land is a big deal for Oxfam. Last year at around this time, we published Risky Business, looking at the explosion in channelling development finance to private sector businesses indirectly, using so-called Financial Intermediaries (FIs) like banks and private equity funds. In the paper we identified some worrying characteristics of this arms-length financing – opacity, complexity, focus on financial returns over development impact, focus on financial risk over environmental and social risk, lack of oversight or ability to influence the business practices of investee companies, remoteness from the projects ultimately financed and the impacts they have on poor people. We worried that such poorly governed financing was fuelling land grabs.

Since then a lot has happened. Oxfam has been asking the World Bank to freeze its large agriculture investments until it puts in place measures to tackle the threat of land grabs. Pressure on the World Bank and IFC has increased as civil society organisations around the world have drawn attention to the plight of poor rural communities whose lives are turned upside-down by deals that infringe their rights and take away their land, many of which are backed by Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) like the IFC.

And it isn’t just Oxfam and the NGO community raising concerns. An audit report from the CAO (the watchdog for the IFC) of IFC’s financial sector investments was made public in early 2013. It was measured in tone but quite devastating in its implications for IFC and for FI lending.

The report found that IFC is unable to track whether or not these investments are causing harm to poor people and the environment, let alone measure whether they bring development benefits. It found serious irregularities and compliance issues within the existing policies used by IFC, with many projects persistently failing to comply with the IFC’s standards. It found inadequate transparency, with at times a near-total absence of public access to information, which can make it impossible for communities to find out if the IFC is even involved in a project, much less know that they could access grievance and redress mechanisms through the CAO.

The response by the IFC to the audit failed to acknowledge the gravity of the issues raised or to commit to properly addressing them. As a result, a large number of CSOs have written to the leadership of the World Bank Group calling for it to put its financial house in order.

Which is particularly striking given that, back at the Land and Poverty Conference, the transparency and accountability of land deals has been a major theme of presentations and discussions. Speaker after speaker stressed (to general agreement) that land acquisition deals must be subject to the consultation and consent of communities affected, must be based on a good understanding of the local context in terms of food security and existing use of resources like water and land, and must actively seek business models that contribute to improving the livelihoods of local communities and create opportunities and incentives for shared prosperity.

This welcome recognition is backed by the statement just released by World Bank President Jim Kim, acknowledging that land grabbing is a serious risk, that the World Bank has a vital role to play in tackling land grabs, and that it could look at its own practices and safeguards as well as committing to support the Voluntary Guidelines on the Governance of Tenure (VGs) and new principles for responsible agriculture investment, which are essential to protect communities’ rights. For more background see this post from Oxfam’s Hannah Stoddart.

But the conference discussions often overlooked the use of FI lending. And although the World Bank statement makes some broad remarks about transparency and due diligence for FI lending, it ignores the very serious issues raised by the CAO audit.

Washington, we have a problem. Looks like we have two very different World Banks on land grabs. So who do we believe, Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? In terms of hard cash, the IFC increasingly dominates. There has been a surge in the channelling of development finance to the private sector through FIs in recent years, from IFC and other DFIs. In 2011, 40% of IFC’s portfolio was made up of lending through FIs. That proportion continues to grow as IFC itself takes up an ever-bigger share of the World Bank Group funding pie (annual reports indicate IFC matches the IBRD at around $20 billion of commitments made in 2012).

terms of hard cash, the IFC increasingly dominates. There has been a surge in the channelling of development finance to the private sector through FIs in recent years, from IFC and other DFIs. In 2011, 40% of IFC’s portfolio was made up of lending through FIs. That proportion continues to grow as IFC itself takes up an ever-bigger share of the World Bank Group funding pie (annual reports indicate IFC matches the IBRD at around $20 billion of commitments made in 2012).

In terms of public policy, we’re starting to see a lot of good progress in acknowledging the key issues of transparency and accountability and remedy, so the contradictory shift towards FI lending is a big issue for those concerned about land grabs. But it goes deeper than that, touching on the way in which publicly-backed development finance institutions like the IFC perform their role. Is it sufficient for the World Bank and IFC to pursue a narrow agenda of growth (economic growth generally or growth in private sector investment) under the assumption that benefits will trickle down to the poorest or, should they instead pay attention to the quality of that growth and investment? That means acting in part like a public body, actively seeking to ensure its intended beneficiaries are not in fact harmed, that it supports projects and influences policy in a way that upholds peoples’ fundamental rights (including to food, land and water), and targets scarce resources to investments in projects where there will be a clear and shared benefit to local communities (especially marginalised groups and women) and national development priorities as well as financial returns for the recipients of finance.

Ultimately, when it lends public money to FIs, is the IFC just a bank, or is it a development finance institution?

After all, from where I am sitting, as a former banker myself – if it looks like a bank, walks like a bank, and talks like a bank, the chances are… it’s just a bank.

April 12, 2013

Are international conferences getting any better? A bit – thanks to some sparky new tech

For a ‘club of rich countries’, the OECD spends a lot of time thinking about development. It’s Development Cooperation Directorate does the number crunching on aid; the OECD Development Centre publishes annual Economic Outlooks on Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia, or Latin American revenue statistics.

For a ‘club of rich countries’, the OECD spends a lot of time thinking about development. It’s Development Cooperation Directorate does the number crunching on aid; the OECD Development Centre publishes annual Economic Outlooks on Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia, or Latin American revenue statistics.

Last week I spent a couple of chilly days at its Paris HQ at the 5th Global Forum on Development discussing the inevitable topic – post2015 and what comes after the MDGs (background papers here). I’m trying to resist the post2015 bandwagon, but it’s generating a hell of a slipstream.

But why did they even invite me? After all, my main reaction to the last OECD conference I attended was to write a post on the awfulness of such international events (a series of soporific panels in a lightless room), and whether they can be salvaged.

So was this one any better? Yes in a few important ways. OK, it was still 300 people in an underground bunker flicking through their emails and half-listening to panels that over-ran and ate up question time, but the organizers had added some nice IT spice to the mix.

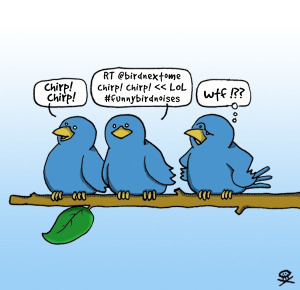

The first was a twitterwall – tweets with the conference hashtag appeared on the same screen as the speakers (and on the monitors that the speakers used to see their own powerpoints). The sense of realtime connectedness increased further when speakers wove responses to tweets into their presentations.

This really alters the dynamic of a conference, not least because people (whether inside the room or watching online) feel much freer to be critical on twitter than in Q&A. The tweets are anonymous, but interestingly, a staffer told me many of the most critical ones were from junior OECD staff who would normally defer to the big cheeses on stage – a real democratising influence, even within the host institution.

twitter than in Q&A. The tweets are anonymous, but interestingly, a staffer told me many of the most critical ones were from junior OECD staff who would normally defer to the big cheeses on stage – a real democratising influence, even within the host institution.

In me at least, especially if everyone’s agreeing with each other, the twitterwall also induces a kamikaze urge to be rude and see it come up on the screen. The adrenalin certainly keeps sleep at bay.

The second innovation was asking people to sign up to an app (wisembly.com) on their smartphones (it even worked on my blackberry). This allowed the 200 people who did so to vote on questions and issues as they emerged during the seminar, including to ‘like’ the various tweets: the most popular were then passed to the panel for responses.

But ‘death by panel’ remained, an apparently immovable object in the international conference format. The standard story is that ‘it’s all about the networking in the coffee breaks’, but then why are the coffee breaks so brief, even before they are further shortened by panel over-run? There must be a reason for this particular way of renewing epistemic communities, but I honestly can’t explain it. Given the huge investment in these events, and their inefficiency in terms of debate and knowledge-sharing, they must fulfil some other deeper function, but what is it? I ended up suggesting to the hosts that the OECD invites an anthropologist to observe their next conference to try and work out what is actually going on.

As for my role in all this, I got lucky, moderating a panel on social cohesion with great speakers. Shirin Chaudhury, Bangladesh’s Minister of Women and Children’s Affairs, gave an inspirational account of her country’s affirmative action policies and efforts to mainstream gender analysis into everything from macroeconomic policy-making to stipends for schoolgirls and ‘info ladies’ going door to door to tell women about the various government services. Pierre Jacquet of the Global Development Network was music to my ears as he called for an end to ‘useless normative statements on post2015 that start with ‘we should’’ and stressed the need to influence national political processes. Alan Hirsch from the University of Cape Town gave a balanced overview of what has/hasn’t been achieved since the end of apartheid and wondered why ‘reconciliation has not led to social cohesion’. Trinh Cong Khang of Vietnam’s Ethnic Minority Policy Department described how the government is trying to build social cohesion with previously excluded groups. All top stuff, and I may try and generate some blog fodder from them.

At a more meta level, my main takeaway from this and other panels was that people always stress the need for national ownership (eg of any post2015 goals), which usually involves adapting whatever is globally agreed to meet national circumstances. But they then deny any trade-offs with global goals. But is that credible? If every country adapts a global instrument differently, they just become part of national political processes (and a good thing too), but lose international comparability.

At a more meta level, my main takeaway from this and other panels was that people always stress the need for national ownership (eg of any post2015 goals), which usually involves adapting whatever is globally agreed to meet national circumstances. But they then deny any trade-offs with global goals. But is that credible? If every country adapts a global instrument differently, they just become part of national political processes (and a good thing too), but lose international comparability.

At the same time, the list of global public goods/collective action problems keeps growing (finance, climate change, drugs trade, trade, tax havens etc etc). At some point, maybe there is need for a parting of the ways, with global processes focussed on collective action problems, while leaving the rest to national politics, backed where necessary by aid. Not that collective action problems are any easier to solve, of course, but it’s just that they won’t be solved anywhere else.

My other gig was an odd one – after dinner speaker with the intimidating brief to a) not repeat anything said in the conference b) be provocative and c) keep people awake. Here’s my talking points (keep clicking til they come up). I couldn’t hear any snoring at the end, so I guess I achieved at least one of my goals.

April 11, 2013

Do hunger and malnutrition make you want to cry? Time to get your HANCI out

Today sees the launch of the Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index (HANCI), produced by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) with funding from Irish Aid and DFID. It looks like it could become one of the more useful annual league tables.

from Irish Aid and DFID. It looks like it could become one of the more useful annual league tables.

It may not be seen as a progressive view in the UK, but I’m a big league table fan, especially when they’re combined with access to new information. They use political rivalry to motivate politicians, the media love them, they allow good guys to be praised, as well as under-performers to be slapped, and they hand civil society some useful ammunition. The post2015 circus might be well advised to spend more time designing an effective league table, rather than adding yet more issues to its Christmas tree.

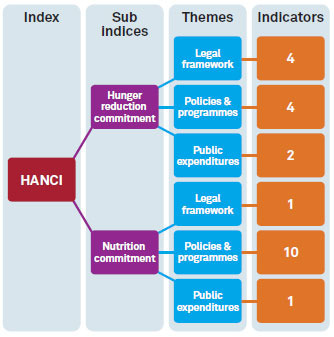

The HANCI assesses governments both by intention and action, examining policies and programmes, legal frameworks and public spending in 45 developing countries across 22 indicators (see chart). It uses separate analyses for hunger and undernutrition, and stresses the differences between them.

The HANCI assesses governments both by intention and action, examining policies and programmes, legal frameworks and public spending in 45 developing countries across 22 indicators (see chart). It uses separate analyses for hunger and undernutrition, and stresses the differences between them.

Guatemala wins the beauty parade, coming ‘a resounding number one’ both on hunger and undernutrition. The report hails ‘a range of efforts by the Government of Guatemala:

Ensuring high level of access to drinking water (92% of the population)

Ensuring good levels of access to improved sanitation (78%);

Promoting complementary feeding practices, and ensuring over nine out of ten pregnant women are visited by a skilled health personnel at least once before delivery;

Investing substantially in health and having a separate nutrition budget line to make its spending accountable to all;

Putting in place a Zero Hunger Plan that aims to reduce chronic malnutrition in children less than 5 years of age by 10% in 2016;

Ensuring that public policy is informed by robust and up to date evidence on nutrition statuses;

Establishing a multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder coordination mechanism that is regionally recognised as an example of good practice.’

In contrast Guinea Bissau is at the bottom of the heap. Other findings include:

Big variation between countries (eg within the BRICS, South Africa is the hero, and India the zero)

Economic growth has not necessarily led to a commitment from governments to tackle hunger and undernutrition

Conversely, countries with low per capita GDP and relatively slow growth, like Malawi, can demonstrate commitment (Malawi came second after Guatemala)

Very low level of correlation between performance on hunger and on nutrition (not clear what to make of that)

Here’s the full index (keep clicking to enlarge a bit):

The HANCI raises lots of questions about the patterns that emerge. All 3 Latin American countries are in the top 5, but the Asian and African countries are much more intermixed. What other features are worth studying? The link to political regimes? Aid dependence? Conflict? It’s a good index and will provide lots of, errm, food for thought.

The HANCI raises lots of questions about the patterns that emerge. All 3 Latin American countries are in the top 5, but the Asian and African countries are much more intermixed. What other features are worth studying? The link to political regimes? Aid dependence? Conflict? It’s a good index and will provide lots of, errm, food for thought.

(And for non-English speakers wondering about the title of this post, it’s a pun on hankie. Geddit?)

April 10, 2013

What is the point of the European Report on Development 2013?

The 2013 European Report on Development was published yesterday, with the title Post 2015: Global Action for an Inclusive and Sustainable Future. I’ve been rude about previous ERDs, and I’m afraid I’m going to be rude about this one, but a conversation at last week’s OECD gabfest (more on that tomorrow) at least made me think differently about the ERD’s purpose and value.

I’ve been rude about previous ERDs, and I’m afraid I’m going to be rude about this one, but a conversation at last week’s OECD gabfest (more on that tomorrow) at least made me think differently about the ERD’s purpose and value.

If you read the ERD as a thinktank document, it is pretty underwhelming. The 20 page exec sum (which is all they sent me in advance) contains no killer facts, no big new ideas and not much new reseach. When I asked one of the report’s authors for his 30 second elevator pitch on what was new, he couldn’t answer. So far, so bad (and they really need to get some media people involved on that elevator pitch).

Instead what you get is a decent overview of progressive thinking on inequality, migration, trade, domestic resource mobilization and the role of aid. And a lot of developmental platitudes: the ‘key conclusions’ include ‘a transformative agenda is vital’, ‘national ownership is key’, ‘the children are our future!’ (OK, I made that last one up).

But weirdly, no mention of the Eurozone crisis, and its likely impact on aid, trade and every other aspect of Europe’s relationship with the rest of the world.

There is one exception to the ‘nothing new’ critique – Chapter Two contains four case studies on Nepal, Peru, Cote d’Ivoire and Rwanda, exploring their experience with the MDGs. At first sight, these might go some of the way to filling the evidential vacuum on how international instruments do/don’t gain traction on national policy, so I may well come back to that chapter.

But when I raised these criticisms with the OECD’s Dirk Dijkerman, he told me I was looking at it all wrong. Although the report insists that it ‘does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union or of its Member States’, in fact it has the hands (and logos and funding) of the European Commission all over it. EC staff were involved in negotiating the final text (pretty intensively on some issues). So the ERD is somewhere between an EU White Paper and an arm’s length World Development Report. The positive content on migration, policy coherence etc has a status with the European Union that an independent report (however well-written) will never have . And sure enough, the discussion at the OECD meeting was all about what the ERD means for European policy.

But if that is the case, I’m not sure the report really makes the most of its unique position. A while ago, I raised some issues where an ERD might have particular relevance, but this report largely ignores them in favour of a global development narrative. Might be better if the authors based the report more overtly on the EU’s sphere of influence, both geographically and thematically (and you’d think the Eurozone crisis would be pretty high on any Eurocrat’s agenda).

But if that is the case, I’m not sure the report really makes the most of its unique position. A while ago, I raised some issues where an ERD might have particular relevance, but this report largely ignores them in favour of a global development narrative. Might be better if the authors based the report more overtly on the EU’s sphere of influence, both geographically and thematically (and you’d think the Eurozone crisis would be pretty high on any Eurocrat’s agenda).

Anyway, the ERD authors should feel free to reply, and here’s an edited down version of the report’s main message:

Main message 1: A new global development framework is needed.

The MDGs have been instrumental in mobilising global support for development, while the vision behind the Millennium Declaration remains highly relevant. A new development framework should build on these efforts.

Main message 2: The framework should promote inclusive and sustainable development.

Poverty eradication remains a central objective, but its achievement and protection will require development strategies that are both inclusive and sustainable, as long-term poverty cannot be eradicated simply through social provisions. Economic growth is key but it needs to be socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable.

Main message 3: The framework must build on an updated understanding of poverty.

A post-2015 framework will have to tackle absolute poverty and deprivation both from an income and a non-income perspective, which incorporate aspects of social inclusion and inequality.

Main message 4: A transformational development agenda is essential for this vision.

A stronger emphasis on promoting structural transformation and particularly job creation will be crucial.

Main message 5: The global framework should support country policy choices and development paths

The policy space of governments should be respected both in determining national development priorities and in other areas such as development finance, trade and investment and migration.

Main message 6: The deployment of a broad range of policies ‘beyond aid’ is essential.

Policies in areas such as trade and investment, international finance and migration have significant effects on development outcomes and need to be designed accordingly and in a coherent manner. ODA will continue to be important, but more as leverage for other finance.

Main message 7: A range of development finance sources will be required.

Domestic resources are the main source of finance for development, not least because they provide the best policy space. Levels of ODA should be maintained and increased, and ODA should be allocated in ways that maximise its impact.

Main message 8: More extensive global collective action is urgently needed.

Achieving the vision of the Millennium Declaration will require considerably greater international collective action to tackle global issues that directly affect the ability of individual countries to achieve development outcomes (eg. development finance, trade, investment and migration).

Main message 9: Processes to address global challenges need to be mutually reinforcing.

Several international processes are probably required to respond to multiple global challenges and support inclusive and sustainable development. A post-2015 agreement may best be conceived as a framework that brings together a series of interlocking and mutually reinforcing agendas.

Main message 10: Over and above its ODA effort, the EU’s contribution post 2015 should also be assessed on its ability to promote PCD and promote conducive international regimes.

The EU’s most valuable contribution to a new global framework for development will be in a range of policies beyond development cooperation (e.g. in trade, migration, PCD, knowledge sharing, climate change, promoting global collective action, and contributing to the establishment of development friendly international regimes) while still maintaining and improving its development cooperation. In particular the EU will need to adopt internal policies that support inclusive and sustainable development at the global level.

And here’s a rather leaden 4m summary video

April 9, 2013

Why I’m not blogging today

Hopefully back tomorrow to review the new European Report on Development

April 8, 2013

What questions help us understand how change happens?

How do we analyse the stories of change that we all use in development? Such stories shape narratives, illustrate approaches and enrich our understanding of how change happens. Regular readers of this blog will know that this is a running theme, but I’m now about to step it up, working with colleagues across Oxfam and beyond to collect and use case studies of change to sharpen our thinking and practice.

How do we analyse the stories of change that we all use in development? Such stories shape narratives, illustrate approaches and enrich our understanding of how change happens. Regular readers of this blog will know that this is a running theme, but I’m now about to step it up, working with colleagues across Oxfam and beyond to collect and use case studies of change to sharpen our thinking and practice.

What emerges when you do this is the problem of ‘retrospective coherence’. Asked to remember what happened, people rearrange and reinterpret a change story. Typically they downplay the importance of failure and unexpected events, and the role of individuals (eg champions within state institutions). They also tend to minimize the role of actors outside the civil society-state interaction – faith leaders, academics, media, private sector, traditional leaders. What remains is a smooth, well-planned and executed project that bears little resemblance to the messy reality faced by people working in real time. So part of the effort in collecting such stories is to recapture what actually happened.

I’ve got case studies coming out of my ears at the moment – working with Oxfam Novib, in East Asia, and with the campaigns and advocacy team – and will be blogging about them as they develop. But in the meantime, here’s the latest version of the guidance questions I send round to kick off the process – I would really appreciate any suggestions for sharpening them up, references etc. They’re also available as a Word document here.

Starting Point

What change did Oxfam seek? Where/how did the idea originate? Was it specific (eg improving livelihoods for X women) or systemic (changing government policy, prevailing norms)? Was it primarily economic, political, social or a combination?

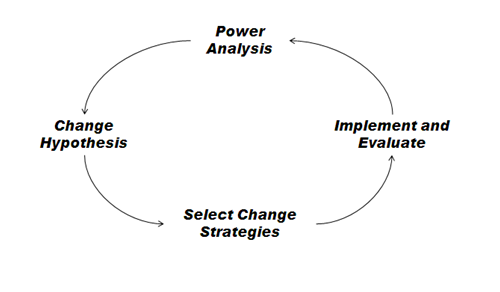

The remaining questions help you work your way round the power and change cycle, which helps in analysing a wide range of change processes (see graphic)

Power Analysis

What was the nature of the redistribution of power involved in the change? Was it primarily about ‘power within’ eg empowering women to become more active social agents, ‘power with’ (collective organization) or ‘power to’ (e.g. supporting CSO advocacy)?

What was the power analysis of the key forces driving/blocking such a change? What economic or political interests were threatened/promoted by the change? Which groups were drivers/blockers/undecided? Was their power formal (eg elected politicians) or informal (traditional leaders, influential individuals)? Was it visible (rules and force) or invisible (in people heads – norms and values) or hidden (behind the scenes influence)

Which individuals played key roles, either as allies or opponents?

Change Hypothesis

What aspects of (or changes in) political, economic, social context made the desired change more or less likely (eg functioning institutions, political leadership, new technologies, new threats or opportunities)

What was the hypothesis for how the change was likely to come about? What alliances (eg with sympathetic officials or politicians, private sector, media, faith leaders or within civil society) could drive/block the change? What tactics were likely to work best (cooperation v conflict, research v street protest)?

What were the pivotal moments/windows of opportunity (eg new governments; changes of leadership; crises and scandals; election timetables)?

Change Strategy

What was Oxfam’s role in promoting change? As an active player or supporting partners? One programme approach, or advocacy/programme only?

Who were our partners – were they ‘usual suspects’ (local civil society organizations and NGOs), ‘unusual suspects’ (private sector bodies, local/national government, faith leaders) or a mixture of both? What was Oxfam’s contribution eg helping them develop a clearer theory of change; bringing partners together with other actors to build alliances; building particular aspects of their organizational capacity; funding?

Implement and Evaluate

What did we/partners actually do (as specific as possible, please!)

What was unexpected? Few change processes go according to plan (although we often rewrite them to make them look that way!) What unforeseen events or realizations (e.g. that something wasn’t working) led to a change of approach? How did the original plan change as the work developed? Were there unintended outcomes and impacts?

Were there early wins that helped build confidence and momentum in the work?

Looking back, what would you have done differently?

How did you monitor and evaluate impact? What evidence can you provide to persuade someone who questions whether your actions actually led to the change described?

What are the top lessons you would draw from this experience for development workers in other contexts?

April 5, 2013

The poorest countries are under renewed threat from WTO rules on access to medicines (and yes, this is 2013)

This week is acquiring an oddly retro flavour. Wednesday had me reminiscing about the Access to Medicines campaign of the last decade. Now it turns out that the issues it raised have recently erupted again. In short, the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) are trying to get another extension to be free from implementing the WTO’s Intellectual Property (TRIPs) agreement. The current stay of execution, agreed in 2005, is coming to an end in June this year and the LDCs have put forward a very sensible proposal asking for a waiver until they graduate from LDC status, so that they don’t have to bother any more with artificial deadlines.

out that the issues it raised have recently erupted again. In short, the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) are trying to get another extension to be free from implementing the WTO’s Intellectual Property (TRIPs) agreement. The current stay of execution, agreed in 2005, is coming to an end in June this year and the LDCs have put forward a very sensible proposal asking for a waiver until they graduate from LDC status, so that they don’t have to bother any more with artificial deadlines.

So far, more than 300 groups have signed a joint NGO letter to WTO Members, because access to medicines, educational resources, seeds or climate change adaptation technologies could all be affected if these countries were to implement the TRIPs agreement any time soon. There are many other reasons why they should not have to implement TRIPs: WTO members owe this to them after failing to deliver on their other promises in the Doha Round (see what I mean about retro?); LDCs don’t have to make any commitments under the parallel agreements on Agriculture and on Non-Agricultural Market Access (NAMA – ah, a wonk’s nostalgia for the acronyms of youth!), so why should they have to implement TRIPs? And anyway, as Ha-Joon Chang has exhaustively documented, all developed countries were IP pirates when they were at a similar stage of development.

The LDC proposal has strong support from other developing countries including the BRICS. In addition, UNDP, UNAIDS and WHO have spoken in favour of the extension. And so has the industry through the CCIA (international IT lobby group, representing Google, Facebook and Microsoft). But (surprise, surprise) the EU, US, Japan and Canada are doing their best to water down the proposal, proposing a short term extension instead, or to include a ‘no roll back clause’, or to differentiate between LDCs. They freely admit in private that they have no economic interest but are pushing this for ideological reasons. Plus ca change.

The LDC proposal has strong support from other developing countries including the BRICS. In addition, UNDP, UNAIDS and WHO have spoken in favour of the extension. And so has the industry through the CCIA (international IT lobby group, representing Google, Facebook and Microsoft). But (surprise, surprise) the EU, US, Japan and Canada are doing their best to water down the proposal, proposing a short term extension instead, or to include a ‘no roll back clause’, or to differentiate between LDCs. They freely admit in private that they have no economic interest but are pushing this for ideological reasons. Plus ca change.

More background from IPWatch. [h/t Romain Bennichio]

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers