Duncan Green's Blog, page 218

April 4, 2013

Food price volatility and obesity – a new development challenge?

Continuing on the ‘new development threats’ theme of yesterday’s post on Big Tobacco, the latest issue of the World Bank’s Food Price Watch looks at the links between increasing food price volatility and obesity. A blog post by the Bank’s José Cuesta starts with a nice counter-intuitive quiz (below).

The correct answers, by the way are C, B and C.

Food Price Watch report explains:

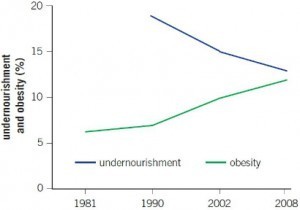

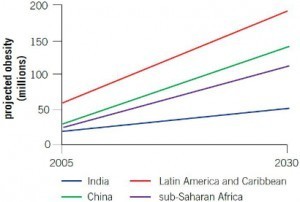

‘Overweight and obesity constitute a global epidemic even in a world of high and volatile food prices. The prevalence and numbers of people affected by overweight and obesity have increased in the last three decades, during both periods of low and high international food prices. So as one malnutrition problem, undernourishment, is falling, others, overweight and obesity, are increasing rapidly (figure 2). In 2008, the number of overweight adults was 1.46 billion, of which 508 million were obese. Even conservative projections predict truly shocking numbers in the future if current trends are unabated: 2.16 billion adults might be overweight and 1.12 billion obese by 2030. And such increases should be expected across all regions and in countries like China and India (figure 3).

overweight adults was 1.46 billion, of which 508 million were obese. Even conservative projections predict truly shocking numbers in the future if current trends are unabated: 2.16 billion adults might be overweight and 1.12 billion obese by 2030. And such increases should be expected across all regions and in countries like China and India (figure 3).

As food prices remain high and, arguably, increasingly volatile, unhealthy calories tend to be cheaper than healthy ones. This is the case of junk food in the developed world, but also of less nutritious food substitutes in poor households in developing countries coping with recurrent food (and other) crises. In fact, overweight is not an epidemic restricted to rich countries. Half of the world’s overweight people live in nine countries, including the United States and Germany, but also in China, India, Russia, Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia, and Turkey. Regions with the highest obesity prevalence — exceeding 25% of the adult population — include North Africa and the Middle East, Central and South America, and southern sub-Saharan Africa.

Policy responses so far have only partially addressed the epidemic. Responses have ranged from doing nothing to punishing overweight people by, for instance, imposing fines on employers when employees exceed certain waistline limits in Japan. Taxes, outright bans, or restrictive legislation on certain foods and ingredients along with clearer standards for food labels and awareness campaigns are attempts to veer consumers toward healthier foods. Yet, it is not evident that reducing obesity is among the top global policy priorities. Nonetheless, the current multilateral discussions on the  post-2015 Millennium Development Goals (along with the UN high-level meeting on the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases) offer an unprecedented opportunity for integrating global and national collective action to fight all forms of malnutrition, from stunting to obesity. This integrated and collective action has, nonetheless, a tall order: it must help prevent this double burden — triple, if micronutrient deficiencies are considered — from increasing as the world becomes more prosperous.’

post-2015 Millennium Development Goals (along with the UN high-level meeting on the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases) offer an unprecedented opportunity for integrating global and national collective action to fight all forms of malnutrition, from stunting to obesity. This integrated and collective action has, nonetheless, a tall order: it must help prevent this double burden — triple, if micronutrient deficiencies are considered — from increasing as the world becomes more prosperous.’

Fascinating and important, but a nightmare in terms of communications for any organization wanting to work on it!

April 3, 2013

6 million deaths a year – where’s the global campaign on Big Tobacco?

Since I wrote recently on the major sources of death in the developing world, I keep spotting things about tobacco that are crying out for action. Take this from last week’s Economist:

this from last week’s Economist:

‘This month Chile became the 14th Latin American country to ban smoking in enclosed public spaces.

Chile’s conversion is significant, since it is something of a smokers’ corner. The World Health Organisation says over 40% of Chileans smoke, compared with 27% of Argentines and 17% of people in Brazil, where curbs on smoking began in the late 1990s. Chile’s health minister, Jaime Mañalich, says that treating tobacco victims takes a quarter of the $10 billion public health-care budget.

Chile’s smokers are getting younger. According to the Tobacco Atlas, a study of the industry, nearly 40% of girls aged 13-15 in Santiago, Chile’s capital, smoke cigarettes. That is up from just 20% in 2003, and is the highest rate in the world. Growing prosperity is partly to blame. Mr Mañalich also points to a cultural change: “Chile has always been a very macho country but that is changing. For women, smoking in public is somehow a sign they are liberated.”

Latin America’s new curbs on smoking face resistance from the industry. Philip Morris International, an American tobacco company, has filed a claim against Uruguay at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, an arm of the World Bank, claiming that the country’s anti-smoking measures violate a bilateral investment treaty. Brazil, the world’s third-biggest producer of tobacco leaf, faces pressure from its planters to protect their jobs.

The anti-smoking lobby wants to see pricing and taxing of cigarettes be co-ordinated across Latin America, to discourage contraband. With income varying widely among countries, that would be hard. But governments could discourage smoking with other steps, such as curbs on advertising, bigger health warnings and subsidising nicotine-replacement therapy.

The anti-smoking lobby wants to see pricing and taxing of cigarettes be co-ordinated across Latin America, to discourage contraband. With income varying widely among countries, that would be hard. But governments could discourage smoking with other steps, such as curbs on advertising, bigger health warnings and subsidising nicotine-replacement therapy.

“Only Satan can grant man the faculty of expelling smoke through the mouth,” declared the Spanish Inquisition in imprisoning Rodrigo de Jerez, one of Columbus’s sailors, and the first person to bring tobacco to Europe. Latin American governments now seem to agree.’

Did you do a double take on para 4? If not, why not? A major tobacco company, Philip Morris, is trying to block the Uruguayan Government’s attempts to limit the devastation. According to a briefing by IISD, the company brought the case in 2010 and ‘is challenging three provisions of Uruguay’s tobacco regulations: (1) a “single presentation” requirement that prohibits marketing more than one tobacco product under each brand, (2) a requirement that tobacco packages include “pictograms” with graphic images of the health consequences of smoking (such as cancerous lungs), and (3) a mandate that health warnings cover 80% of the front and back of cigarette packages.’ Philip Morris’ own version of events confirms this.

The ICSID says that the suit is ongoing, with a tribunal meeting in Paris last February.

Now tobacco is the world’s number one killer, claiming 6m lives a year (over 3 times the number of deaths caused by HIV/AIDS). When Big Pharma tried to restrict access to HIV/AIDS medicines, campaigners jumped all over them, with considerable success (as this week’s landmark ruling against Novartis in India shows). The standard Oxfam recipe for a good campaign is that you need a problem, a solution, and a villain. Big Tobacco would seem to tick every box, don’t you think?

tried to restrict access to HIV/AIDS medicines, campaigners jumped all over them, with considerable success (as this week’s landmark ruling against Novartis in India shows). The standard Oxfam recipe for a good campaign is that you need a problem, a solution, and a villain. Big Tobacco would seem to tick every box, don’t you think?

April 2, 2013

Whither (wither?) the ANC? Final thoughts on South Africa as a developmental state and the crisis of leadership

Like most of my overseas trips, my recent visit to South Africa resembled an intensive rolling seminar, as debates with brilliant Oxfam staff, partners and academics spilled over from conferences and meetings into cars and bars. Before it all recedes into the mists, I wanted to capture one of the recurring themes. The role of the South African state and the ANC.

Discussions on the developmental state are vibrant in South Africa. They are also very confusing. Often, the term is bandied about to describe anything a state should do to pursue development. But the term’s original meaning is much more specific, rooted in Chalmers Johnson’s attempt to explain the Japanese economic miracle of the 1960s and 70s. That includes a starring (and steering) role for a semi-autonomous technocracy, able to pursue a long term industrial upgrading project without succumbing to the short term demands of interest groups. Would anyone seriously compare that to what is currently happening in South Africa, where every day newspapers splash on the latest stories of chaos, intrigue and incompetence within the state machinery?

a state should do to pursue development. But the term’s original meaning is much more specific, rooted in Chalmers Johnson’s attempt to explain the Japanese economic miracle of the 1960s and 70s. That includes a starring (and steering) role for a semi-autonomous technocracy, able to pursue a long term industrial upgrading project without succumbing to the short term demands of interest groups. Would anyone seriously compare that to what is currently happening in South Africa, where every day newspapers splash on the latest stories of chaos, intrigue and incompetence within the state machinery?

Actually, there is one part of the South African state machinery that is renowned for its efficiency and transparency – the South African Revenue Service (SARS, unfortunate acronym). One staffer at an Oxfam partner even said ‘if SARS was a party, I would vote for it’. Not often you hear that level of affection for the taxman.

But there are other points of comparison – Japan was certainly not free of corruption. More importantly, South Africa does have an activist state and that began long before the ANC. A questioner from the floor caused a stir at one seminar when he said ‘the closest South Africa has come to a developmental state was under apartheid’. The state provided for whites, and the non-white labour it required. I was struck by the amount of state housing for all ethnic groups – rows of identical brick two bed houses are dotted around the chaotic sprawl of self-built ‘informal settlements’.

That tradition of state provision continues under the ANC. Housing, education and health have improved, though there is an awfully long way to go. But this prompts heated debates on whether the South African style of provision encourages passivity and dependence. Anti-state types love the dependence narrative as it provides a perfect excuse for cuts, but not everyone who worries about it can be written off as a bloodthirsty fiscal hawk.

what happens after he's gone?

On housing for example, I was struck by the different approaches in some places in Latin America, where the state supports (rather than replaces) self-build, eg by providing an engineer to advise, or by building only one room and leaving spaces for shanty-town dwellers to add their own (as they inevitably do). Does that approach increase agency as well as produce more housing per dollar?

In the end, all conversations came back to the state and fate of the ANC. The party suffers from Beatles syndrome – applauded outside the country, but much less popular at home. The headlines are all about corruption, which seems widespread, but in many ways patronage is more of a problem than plain theft. Not only does that benefit ‘tenderpreneurs’ who use their connections to win state contracts, however incompetent the execution; it also leads to the wrong people in key jobs – ‘someone who has never been to school becoming a mayor’.

If the ANC is to rekindle its waning legitimacy, it has to tackle some big headaches. How to redistribute land without destroying agroexports? Could it nationalise parts of the mining sector, and if it doesn’t, does it risk a Zimbabwe style split between party and trade unions, as Cosatu loses patience?

Overall the level of political paralysis and growing inequality and unrest means the ‘ANC is tiptoeing on a land mine’. How might it all end? Random speculation over a beer Deep and thoughtful analysis suggested a few possibilities:

Rising expectations both among the poor (growing protests over poor quality services) and the middle class (‘I’ve got my degree, now where’s

my job?’) leads to a broad protest movement and some kind of Arab Spring type meltdown.

my job?’) leads to a broad protest movement and some kind of Arab Spring type meltdown.Possibly linked to this, the party splits and South African politics becomes genuinely competitive and multi-party. All parties have to sharpen up, both in terms of corruption and competence, if they are to get elected.

Alternatively, the lack of opposition removes any incentive for party discipline. Politics becomes a vehicle for grabbing the spoils of power, and leads to increasing infighting within the ANC and a slow slide into chaos and incompetence (call it Nigeria on a bad day).

The ANC pulls back from the brink, finds new, dynamic leaders, and regains its appeal by attacking South Africa’s malaises of inequality, unemployment and poor administration.

Any other plausible scenarios?

The other posts from South Africa were on Women on Farms and the recent farmworkers’ strike; Brazil v South Africa on inequality; How to build local government accountability and How can South Africa promote citizenship?

April 1, 2013

Top April Fool – Guardian Goggles

Let us do the thinking, while you got on with the living…… [h/t Calum Green]

March 28, 2013

What is the impact of women’s collective action? Evidence from 3 African countries

A day in the life of a woman agricultural policy adviser in West Africa

Sally Baden (left, in the white shirt), Oxfam’s former Senior Adviser on Agriculture and Women’s Livelihoods, summarizes the findings of a new Oxfam report and research project on women’s collective action in agriculture.

As an Oxfam policy adviser in West Africa (2001-8), I worked with many different kinds of farmer organization. These included cotton farmers, pastoralists and rice growers, grouped in informal enterprises as well as more formal associations and cooperatives.

On occasion, they were women-only groups – such as the organic Shea butter producers of Songtaaba in Burkina, one of a small but growing number of women-led collective businesses. But most farmer organizations were mixed sex – which in practice often meant male dominated, providing plentiful anecdotal evidence that led me to question whether, in fact, women benefit.

In a meeting with national level producer leaders, the proposal from a (lone) women farmers’ leader that women members be targeted for literacy training led to one (male) farmer storming out of the room, such was his fury.

When facilitating a planning workshop with leaders of pastoralist groups from different countries in the Sahel, it was clear that the few women present were reluctant to speak. During the lunch break, one woman grabbed my arm and whispered in a panicked tone, ‘You must help us: If the men get better access to markets, they’ll use the money to buy more wives’.

When interviewed separately during a funders’ visit to a cotton-farmer cooperative, a group four or five women, expressed their disenchantment with the coop. They felt they are used as free labour and to cook food for meetings and village festivities but have limited say in decisions and derive little benefit. (Back in the room, the men, by contrast, said they favoured women’s involvement!)

These experiences, plus similar ones from other colleagues led us in 2009 to launch the ‘Researching Women’s Collective Action’ (RWCA) project to understand which women participate in collective marketing groups – in Ethiopia, Mali and Tanzania – how they benefit, and what NGOs and others are doing to support women’s engagement in markets. We first did an extensive literature review, organized stakeholder dialogues and conducted scoping research in 15 agricultural sectors. Then we carried out surveys of nearly 3000 women (members of marketing groups and non members with similar characteristics – as a control) focused on one subsector in each country, as well as in-depth case studies of 12 groups, via focus groups and interviews with key informants.

The RWCA’s results are published today in a new Oxfam research report.

Are the examples above an unfair caricature of patriarchal attitudes (especially coming from a European feminist)? Yes, up to a point: Oxfam’s RWCA research found that male leaders’ and husbands’ support has been vital to those women who have been able to actively participate in and benefit from collective action groups, including as leaders. Whether to engage their support, or to mitigate their opposition, strategies to promote women’s empowerment ignore men at their peril.

In more detail, the findings included:

Women’s participation in collective action groups delivers significant economic benefits, but the choice of market is critical: High value products (vs. staples or traditional exports) which have local as well as national or international markets are likely to yield more benefits. This is true for producer organizations in general, but women in particular. Women in groups gained high returns from the vegetables sector in Tanzania: up to $340 per annum for women who joined groups compared to those not in groups. The estimated monetary value of increased gains from sales was lower in Mali (Shea butter) and Ethiopia (honey) but still significant, at $12 and $35 a year respectively. Those sectors were also relatively easier for women to enter, as they do not require control over land.

staples or traditional exports) which have local as well as national or international markets are likely to yield more benefits. This is true for producer organizations in general, but women in particular. Women in groups gained high returns from the vegetables sector in Tanzania: up to $340 per annum for women who joined groups compared to those not in groups. The estimated monetary value of increased gains from sales was lower in Mali (Shea butter) and Ethiopia (honey) but still significant, at $12 and $35 a year respectively. Those sectors were also relatively easier for women to enter, as they do not require control over land.

Wealthier, higher status women are more likely to join groups, unless measures are taken to target the less well off: Group membership rules of ‘one member per household,’ requiring land ownership, or only admitting married members, indirectly discriminate against women or certain categories of women. In Ethiopia, unmarried women were able to access groups because NGOs and government specifically targeted female heads of household. Married women’s participation dramatically increased after local lobbying for ‘dual membership’ per household led to changes in cooperative by-laws.

Participation in informal women’s groups increases the likelihood that women will join formal marketing groups and reinforces the benefits they derive: Building on traditional institutions such rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs), burial societies (iddir – in Ethiopia) or labour-sharing groups, informal groups help women to develop confidence and leadership skills as well as accumulate savings, which facilitate marketing of their produce. However, as the basis for collective marketing such groups have limitations: collective enterprises require different skills, strong networks, group investments and legal recognition. Linking informal women’s groups with mixed marketing groups can be an effective hybrid strategy, as we found in Ethiopia.

Women rarely have equal say in or leadership of mixed groups, while women-only groups may face challenges with business viability: Women themselves recognize these tensions: when the Matumaini A group in Tanzania lost most of its male members due to ‘women’s dominance’, members recognized that this also meant losing valuable skills, resources and networks. In Mali, ostensibly women-only groups had one or two male members, deployed for tasks such as negotiating with village chiefs where women were prohibited from crossing the threshold. One such group was even named after their token man!

Participation in marketing groups leads to improved incomes, but weak effects on empowerment: In contrast to the economic benefits, we found limited evidence of a clear link between women’s empowerment and group participation. To assess this, we adapted elements of the ‘Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index’, an innovative methodology called developed by the Oxford Human Poverty Institute (OPHI) and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) – explanatory video here.

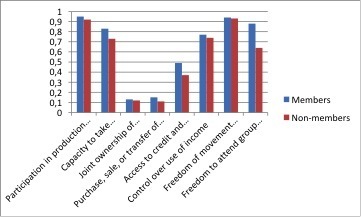

Graph comparing women group members control over different areas of decision making vs. non members (Mali)

Our research showed that empowerment was greater when women participate in informal as well as formal groups.

Control over credit was the one area where women’s decision making was enhanced by group membership across all three countries. Other dimensions of empowerment – such as mobility – were affected, though less consistently. Women reported increased control of incomes from the sale of Shea butter, honey or vegetables, but this didn’t seem to extend to wider household incomes, except in Ethiopia. And it was only in Mali that stronger women’s rights over land were linked to group membership.

Learning from such experiences, development actors – including Oxfam – need to adopt flexible approaches to supporting collective action, taking the wider context into account, and supporting women’s own initiatives. We also need to pay more attention to the policy environment, enshrining clear principles of equality in cooperative laws, setting explicit targets to address women’s participation and leadership, making membership rules and procedures more flexible, and protecting the space for informal association.

So: Does organizing groups of rural women producers contribute to rural women’s empowerment as well as increasing their incomes? My answer is a qualified ‘yes’; it can be a step towards increased empowerment, for some women, under the right conditions. But we are only just beginning to understand the relationships between markets, collective action, intra-household relations and ‘women’s empowerment’. More innovation and more research are (of course) needed.

March 27, 2013

What can DFID learn from Chinese and Brazilian aid programmes?

IDS researcher Henry Tugendhat (right) wonders whether UK aid is following in the path of China and Brazil

Two weeks ago at the London Stock Exchange, Justine Greening announced her new policy of supporting UK businesses to invest in developing economies for the mutual benefit of both sides. According to the UK’s Secretary of State for International Development: “This is good for investors, who earn a financial return… [and] good for the poorest, who receive jobs and support”.

New as it may sound in UK development circles, this strategy sounds an awful lot like the “win-win” sound-bites we’re increasingly used to hearing from China among the other BRICS countries, who are meeting in Durban, South Africa this week. China and Brazil have both made efforts to leverage private sector investments as part of their aid/South-South Cooperation agendas, but problems have already arisen which the UK could usefully learn from.

Alignment of aid and investment efforts is a particular challenge. Business seeks profit, while aid is traditionally geared to humanitarian objectives, and they don’t always match up.

One example is the disconnect between the promotion of food security in Africa, and the agricultural interests of investors. The Chinese state has pushed for a serious engagement with food security issues affecting African countries. This is seen in everything from meetings in the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, to Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centres. Equally Brazil has committed to supporting agricultural mechanisation and technical support in a number of countries.

All such efforts are envisaged to link to private sector activity: to provide tractors, take over farms, or offer technical support. However, Chinese and Brazilian investors in Africa have predominantly invested in cash crops and large-scale farming, and even when smallholders are targeted, in many cases they have been those that are better off and already more commercially oriented.

New evidence from the Future Agricultures Consortium generated by research in Ghana, Ethiopia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, shows that when Chinese companies do invest in local agriculture, it is predominantly in crops such as cotton and tobacco. Otherwise, additional investment has focused on surrounding infrastructure such as irrigation schemes and roads. Brazilian investments have predominantly focused on sugar-cane and ethanol production. However, when private sector investment has targeted food staples necessary for food security, there has been either little success, as in the Xai-Xai project in Mozambique; or only small-scale investments, as in the small farms in Ethiopia that supply local Chinese restaurants.

not the right model for Africa?

Adding to this disconnect between Chinese and Brazilian government statements and the behaviour of their companies, even Chinese state-owned enterprises at times flex their independence from state interests, as Lucy Corkin describes for Angola. But of course, Chinese companies in particular may be subject to more pressure than UK companies to invest in areas aligned with state interests abroad, as they are often supported by state policy and finance. Which begs the question: when financial returns are less obvious, what makes Justine Greening more able to leverage investment for development interests, where China and Brazil have failed?

The second issue is that many investments in Africa have led to harmful practices over the years, whatever the nationality of the investor. Even if investors are introduced based on the principle of “development assistance”, profits are still paramount. This can lead to unintended consequences. For example, Chinese and Brazilian companies have got mired in controversy in recent years, including accusations of ‘land grabbing’, even when such claims have been refuted.

One of the currently most contentious investments is the vast ProSavana project spearheaded by Brazil in a triangular agreement with Japan and

Mozambique. The aim is to bring about agricultural development in Mozambique’s Nacala corridor, transforming it into a bread-basket on the scale of Brazil’s Cerrado savannah region, the site of a “green revolution” transformation which began in the 1970s. Brazilian private investors are already, as well as Japan, and a ‘Nacala Fund’ expected to mobilise US$2 billion has been set up. Already described as an example of ‘Brazil’s neo-colonialism in Africa’ in the Mozambican press, the project has come under heavy fire from local civil society groups that criticise the secrecy surrounding the project and the risk of evictions of local smallholder farmers.

So will ‘land grabbing’ become an issue that UK businesses face if they follow Justine Greening’s recommendations? In her speech, she recognised this challenge, arguing that there is a need for transparency on investments, so as to expose “those who acquire land unfairly”.

As a final thought, we should also question whether this new policy could be a subtle re-introduction of tied aid practices, despite Justine Greening’s

strong assertions to the contrary. The political reality is that this would no doubt be an appealing means of defending the aid budget against current cuts, so it must be properly scrutinised to avoid to a return to inefficient aid practices.

Ultimately, overseas investment by private sector actors is open to many challenges and problems. As the UK adds this new facet to its aid programme,

lessons from Brazilian and Chinese experiences in Africa should definitely be heeded.

Henry Tugendhat is a Research Officer at the Institute of Development Studies, with responsibility for the China and Brazil in African Agriculture

project, involving roughly 20 researchers from institutes across Africa, Brazil and China. For more information and the project’s first working papers click here.

March 26, 2013

Strikes, Spookytown, and a traumatic exit from feudalism: Women on Farms in South Africa

Managed to squeeze at least one day away from offices and lecture theatres in South Africa last week. In this case a road trip with Women

credit: Rehana Dada

on Farms, an Oxfam partner led by the charismatic Colette Solomon (right), IDS PhD turned grassroots activist. In the Western Cape, scenic is an understatement: lush vineyards festooned with bougainvillea at the feet of colossal bare rock escarpments; dinky, opulent colonial towns – all church spires and verandahs and 4×4s. Perfectly asphalted roads, the infrastructure of modern ag – sprinklers, trucks, tourism (wine tasting, restaurants), a vision of plenty.

But where are the people? We go looking for them, and find women farmers living in the interstices of all this wealth. Crammed onto remaining pieces of ‘commonage land’, where they struggle with markets and theft; dumped in shacks in unlit, dangerous ‘Spookytown’ (left) on the edge of one of those nice colonial outposts (Rawsonville) after mass evictions from the commercial farms (too old, too rebellious, or just surplus to requirements). Black, coloured, marginal – at first it feels like apartheid hasn’t gone away.

But it’s more messy than that. We end up in a lovely little cul de sac of coloured (mixed race) workers’ houses on Die Eike, a giant fruit farm supplying Tescos, among others. The houses are comfortable, with all mod cons, and gardens bursting with flowers. If the Spookytown inhabitants’ pre-eviction homes were anything like this, I feel their current pain. The Die Eike women took part in the first farmworkers’ strike in South Africa, an apparently spontaneous eruption last November, timed perfectly to hit the start of the harvest, earning them a big hike in the minimum wage (SAR 69 to 105) and global headlines. ‘It was like a bomb exploded, we said ‘we can do this’. Even though we’d known our rights all these years, we’d never had the guts.’

As they recount the story, their Afrikaans is peppered with English words – ‘labour rights’, ‘sisters’, ‘government’, ‘power’. Politics, it seems, is conducted in English. But paternalism is undoubtedly Afrikaans. Like their peers in Spookytown, these women are shocked at the change that has come

over the farmers (‘the boers’) since the strike. ‘Farmers don’t trust the workers like they did.’ Stories abound of threats of eviction, rent increases, swathes of new, unintelligible deductions wiping out the advances on their new pay cheques (the new wage came in at the beginning of March).

Much of the harassment feels like a petty war of attrition: ‘we’re not allowed to take fruit home any more; we can’t eat food on the job. They’ve cancelled the morning and afternoon breaks’. The kids are no longer allowed in the orchards. The estate drags its feet in repairs when things break in strike leaders’ homes.

What seems to be going on is a high speed transition away from a semi-feudal paternalist system in which many ‘boers’ paid over the minimum wage, and were happy to give advances on wages, or help out ‘loyal’ employees (we met one old woman living rent free in the middle of a commercial vineyard, growing vegetables – as a young domestic worker, she raised the present owner, and he didn’t hesitate to help her when she subsequently fell on hard times). No rights, but some consideration.

The strike seems to have triggered a shift away from that to purely monetary relationships, and workers (and probably farmers, but I didn’t talk to them) are finding it traumatic. In one Spookytown shack devoid of electricity or running water, ‘Auntie Rosa’ (left) explains how she looks after her extended family of 10, relying largely on her monthly pension of SAR 1200. She pays out SAR 240 for the family funeral policy, SAR 210 for school fees for 3 kids and then SAR 540 for the washing machine. Eh? She takes us inside and shows us the power-less washing machine, fridge and sound system, all brought here on eviction from her nice farm house. She struggles to explain why she keeps up the payments at such personal cost, but I think it’s because they connect her to that better life back on the farm.

them) are finding it traumatic. In one Spookytown shack devoid of electricity or running water, ‘Auntie Rosa’ (left) explains how she looks after her extended family of 10, relying largely on her monthly pension of SAR 1200. She pays out SAR 240 for the family funeral policy, SAR 210 for school fees for 3 kids and then SAR 540 for the washing machine. Eh? She takes us inside and shows us the power-less washing machine, fridge and sound system, all brought here on eviction from her nice farm house. She struggles to explain why she keeps up the payments at such personal cost, but I think it’s because they connect her to that better life back on the farm.

That farm-supplied housing leaves workers extremely vulnerable to harassment, and may well decline if the transition to monetarised relationships continues. But also missing are the institutions that can defend the workers in this new savage capitalist era. A strike can win a one-off victory, but how to defend against the war of attrition that follows? Farmworkers will need some institution to call when the harassment starts, but who? Trade unions exist but find it hard to organize, often in the face of massive farmer hostility (‘why should my workers need a union?’). And while a wonderful organization, Women on Farms is too small and under-resourced to play the necessary role.

I really hope someone is documenting this transition as it happens, and before it becomes the stuff of myth.

March 25, 2013

Brit aid rocks; economists’ letters; out of order; gods v condoms; what did dev pundits get wrong?; carbon taxes; land grabs + bent pols in Malaysia: links I liked

I generally tweet links these days (@fp2p if you want to follow), but for the untwittered, here are a few recent highlights:

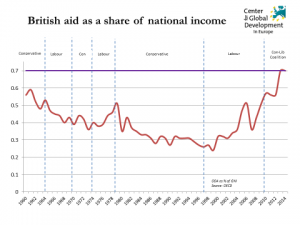

A wonderful (and politically inexplicable) thing happened last week. Amid gloom and austerity, the UK government kept to its promises and increased aid to 0.7% of national income – the first G8 country to do so. It barely warranted a mention in the press coverage, but Owen Barder had a nice piece + graph showing the turnaround (right, from 1960 to present, turnaround is 1997).

aid to 0.7% of national income – the first G8 country to do so. It barely warranted a mention in the press coverage, but Owen Barder had a nice piece + graph showing the turnaround (right, from 1960 to present, turnaround is 1997).

Oxfam did its bit as part of the IF campaign, sending in 500 George Osbournes to spread the word, and persuading 100 economists to sign a letter supporting the move. Save the Children also got a pile of economists to sign up to a letter on why inequality should be at the centre of the post2015 debate. But be warned, these are economists – only a matter of time before they start charging.

A smart Australian campaign – slapping ‘out of order’ signs on vending machines of bad companies (here, Coca Cola. Allegedly).

A smart Australian campaign – slapping ‘out of order’ signs on vending machines of bad companies (here, Coca Cola. Allegedly).

Religious leaders are up to their old tricks in Kenya, getting TV to drop a USAID and UKAid-funded advert encouraging condom use. Sigh.

Alex Evans lists ten things development pundits like him missed/got wrong in the 2008/9 food/finance meltdown. Excellent corrective for anyone involved in the bla bla business.

The gulf between reason and politics is nowhere greater than on climate change. The Financial Times had a well-argued editorial making the case for carbon taxes. Anyone listening?

Some great investigative campaigning from Global Witness on corruption and land grabs in Sarawak (Malaysia). Got a mention in this week’s Economist too.

March 22, 2013

The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. Synthesis > novelty in a big new UN report.

Of the big reports that spew forth from the multilateral system, some break new ground in terms of research or narratives, while others usefully recap  the latest thinking on a given issue. Last week’s 2013 Human Development Report, The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World, falls into the latter category, pulling together the evidence for a tectonic North-South shift in global economic and political affairs, summarizing new thinking on inequality, South in the North etc and asking what happens next. If you’re currently sunk in the depths of Europessimism or US political stalemate, you may find such an upbeat story refreshing (or even disturbing). You can read the exec sum online, but it doesn’t seem to allow you to cut and paste (v annoying for lazy bloggers like me).

the latest thinking on a given issue. Last week’s 2013 Human Development Report, The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World, falls into the latter category, pulling together the evidence for a tectonic North-South shift in global economic and political affairs, summarizing new thinking on inequality, South in the North etc and asking what happens next. If you’re currently sunk in the depths of Europessimism or US political stalemate, you may find such an upbeat story refreshing (or even disturbing). You can read the exec sum online, but it doesn’t seem to allow you to cut and paste (v annoying for lazy bloggers like me).

Some useful numbers to demonstrate the extent of the shift: From 1980 to now, developing countries’ share of global GDP rose from 33% to 45%, their share of world goods trade from 25% to 45%, and South-South trade as a % of the world total rose from 8% to 26%.

How has this happened and so what? The HDR’s approach is to learn from the success of 18 of the more than 40 countries in the developing world that have done better than expected in human development terms in recent decades, with their progress accelerating markedly over the past ten years. Not just China and India, but countries like Turkey, Ghana and Mauritius. Again, nothing new there – the Growth Commission had a go at that five years back – but still infinitely preferable to maths-led regression-tastic nonsense that ignores history and politics.

Compared to the Growth Commission, the HDR’s conclusions are more interventionist, and more political. The Report identifies 3 main drivers shared across the success stories:

1. A proactive developmental state

2. Tapping into global markets

3. Determined social policy innovation

On the role of the state, successful countries ‘share some key characteristics. Most were proactive “developmental states” that sought to take strategic advantage of opportunities offered by world trade. They also invested heavily in human capital through health and education programs and other essential social services. More important than getting prices right, a developmental state must get policy priorities right. They should be people-centred, promoting opportunities while protecting against downside risks.’

In case you missed it, that’s a not-very-subtle two fingers to the Washington Consensus and its preference for ‘getting the prices right’.

Oops, wrong South

The report points to some downside risks that threaten this progress: ‘short-sighted austerity measures, failures to address persistent inequalities, and a lack of opportunities for meaningful civic participation.’ But overall, as the South rises, the focus will shift to ‘long-term challenges shared by industrialized countries of the North’ – both commonly shared issues like ageing and jobs, and collective action problems like climate change.

Its recommendations for continuing this amazing progress include

1. Developing countries need to move their focus from ‘growth first’ to human development

2. Enhanced South-South learning and integration

3. Greater representation for civil society and the South in the international system. Global institutions have not yet caught up with this historic change (the international system’s loss rather than the BRICS’). China, with the world’s second largest economy and biggest foreign exchange reserves, has but a 3.3 percent share in the World Bank, less than France’s 4.3 percent. India, which will soon surpass China as the world’s most populous country, does not have a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. And Africa, with a billion people in 54 sovereign nations, is under-represented in almost all international institutions.

And in a nice table-turning touch, the report ‘urges the convening of a new “South Commission” where developing countries can take the lead in suggesting constructive new approaches to effective global governance.’

Nothing earth-shattering, but a useful exercise in synthesizing the evolving understanding of development and repositioning the multilaterals within it. So what have I missed?

And here’s the rather frenetic animated version

March 21, 2013

Kevin Watkins on inequality – required reading

If you want an overview of the current debates on inequality, read Kevin Watkins’ magisterial Ryszard Kapuściński lecture. Kevin, who will shortly take over as the new head of the Overseas Development Institute, argues that ‘getting to zero’ on poverty means putting inequality at the heart of the development debate and the post2015 agreement (he doesn’t share my scepticism on that one). As a taster, here are two powerful graphs, showing how poverty will fall globally and in India, with predicted growth rates, in a low/high/current inequality variants. QED, really.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers