Duncan Green's Blog, page 215

May 16, 2013

A crucial step in fighting inequality and discrimination: the law to make India’s private schools admit 25% marginalised kids

This guest post comes from Exfam colleague and education activist Swati Narayan

This summer, India missed the historic deadline to implement the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009. This landmark law, the fruit of more than a decade of civil society activism, has many path-breaking clauses. For the first time, it bans schoolteachers from offering private tuition on the side – a rampant conflict of interest. It also legally prohibits corporal punishment.

Most powerfully, it insists that every private school must reserve 25 percent of classroom seats for children from poorer or disadvantaged families in the neighbourhood. This quota is by no means a silver bullet. After all, eighty percent of schools in India are government-run and in dire need of teachers, infrastructure and more.

Nevertheless, this masterstroke, which aims to piggyback on the rest of the mushrooming for-profit private schools, single-handedly opens the door for at least 1 million eligible children each year across the country to receive 8 years of free education.

Despite strident opposition from school management and parents’ associations, the Indian Supreme Court last year upheld this visionary clause. Though it may not (yet) be as internationally renowned as the United States’ Brown versus Board of Education ruling, its ripple effect will be no less important in a country as socially stratified as India.

In the last three years, apart from resorting to the courts, private schools have used every trick in the book to deny children their rightful admissions (see video). Despite a ban, some have held separate evening classes to accommodate students from poorer families. Others have sent eligible parents literally in circles over admission paperwork. As a result, last year, Maharashtra state, for example, filled only 32 per cent of reserved seats.

One bone of contention is who will foot the bill? The Act is categorical that the state will reimburse private schools only based on what it spends per pupil in government schools, which is typically much less. For-profit private schools are therefore keen to pass on the burden and increase their already inflated fees for the remainder of the class. Unfortunately, this has pitched wealthy parents against semi-literate ones, further aggravating tensions across the class and caste divides.

One bone of contention is who will foot the bill? The Act is categorical that the state will reimburse private schools only based on what it spends per pupil in government schools, which is typically much less. For-profit private schools are therefore keen to pass on the burden and increase their already inflated fees for the remainder of the class. Unfortunately, this has pitched wealthy parents against semi-literate ones, further aggravating tensions across the class and caste divides.

On the other hand, many civil society activists are disappointed that the legislation only reserves 25 percent and does not embrace the more inclusive concept of a ‘common schooling system’.

But, even this diluted, watered-down 25 percent reservation clause offers an unprecedented window of opportunity to break the shackles of centuries of social prejudice, which has pigeon-holed and stymied educational, occupational and social opportunities for generations. For the first time, there is a genuine effort to ensure that that children — rich and poor, upper and lower caste — are schooled together at an impressionable age, perhaps laying the basis for India to overcome centuries of divisions.

Even today, children of marginalized castes and tribes are less likely to attend pre-primary and primary school and the quota defines them as primary beneficiaries of the new legislation. The law also supports the entry of children with disabilities. In addition, some states have devised truly progressive rules. Tamilnadu, for instance, has recognized transgender children as eligible. Andhra Pradesh explicitly includes orphans, street and homeless children. Gujarat has clarified that teachers should be professional trained and sensitized for the proper integration of children and warned that schools which discriminate could face closure.

These gems in the rulebook could revolutionize private education in India.

Sister Cyril’s award-winning elite Loreto School in Kolkata, has over the last three decades, already showcased first-hand the transformational potential of integrating street children in mainstream classrooms.

Now, the key to the success of this dream to create inclusive classrooms lies with the burgeoning Indian middle class — to support rather than oppose — this transformative initiative to build the foundation for a more integrated India.

Swati Narayan is a social policy analyst

May 15, 2013

What do we know about the impact of savings groups on poor African women?

Savings for Change (SfC) is one of Oxfam America’s flagship programmes, reaching 680,000 members, mostly women, in 13 countries. Here Sophie Romana, Oxfam America’s Deputy Director of Community Finance, reports on some findings from an innovative qualitative and quantitative survey of the groups in Mali, published today (click through to summary or full report).

Here Sophie Romana, Oxfam America’s Deputy Director of Community Finance, reports on some findings from an innovative qualitative and quantitative survey of the groups in Mali, published today (click through to summary or full report).

How do you save money and borrow when you live in rural sub-Saharan Africa? Millions of women do just that every week, through their Savings Group. Formed and monitored by teams of field agents from local organizations, 20 to 25 women gather every week at the same time and place to put a few cents in a wooden “savings box”. Once there is enough money in the box – i.e. the saving fund – members who need a small, short-term loan come in front of the self-managed group to explain the purpose of the loan (food purchases, life’s emergencies or working capital for an income generating activity). The loans are paid back to the group with interest, which provides them with a return. In a nutshell, savings groups provide basic financial services to poor rural women underserved or ignored by commercial banks and microfinance institutions.

But does belonging to a group actually improve the lives of members, their families, and their villages? To answer this, Oxfam America and Freedom from Hunger commissioned Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) and the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology (BARA) at the University of Arizona to conduct a unique piece of joint research on Saving for Change groups in Mali: a randomized controlled trial (RCT) combined with a qualitative longitudinal study, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The RCT included 500 villages: in 210 of them we introduced SFC, the other 290 were “controlled” (intentionally left out of the intervention) to try and measure the difference, hence the impacts. The qualitative survey focused on 19 villages included in the RCT and interviewed members, husbands, women non-members, villagers etc… This mixed-methods approach combines the benefits of ‘quant’ and ‘qual’ to try and get under the skin of the impacts of savings groups.

The findings of the three-year study (see chart) show encouraging results in terms of increased saving (up 31%) and lending (12% more women took a loan from a savings group), increased food security, and an increased investment in livestock (households in SfC villages own on average $120 more in livestock, which buys you four goats, three ewes or one calf). The findings also demonstrate that savings groups reach the poorest of the poor with 82% of households in study villages living on less than $1.25 a day.

The findings of the three-year study (see chart) show encouraging results in terms of increased saving (up 31%) and lending (12% more women took a loan from a savings group), increased food security, and an increased investment in livestock (households in SfC villages own on average $120 more in livestock, which buys you four goats, three ewes or one calf). The findings also demonstrate that savings groups reach the poorest of the poor with 82% of households in study villages living on less than $1.25 a day.

The results from the RCT also show that there was almost no change in income and health and education expenses. We hope that these results will come with longer study, but we are not sure.

Social capital, one of the outcomes most valued by group members, is proving to be a puzzle. The group offers a safe space for women to share family problems and seek advice from each other. Outside the meeting, women have also reported over the years that they tend to greet each other more in the village, and engage with each other more often than before they joined. But here’s our evidence puzzle: this is what the anthropological findings support, but they were not captured at all by the quantitative-RCT.

Take up rate: how do groups get created in zones where we don’t run the program?

Based on feedback from our partners and staff, Oxfam started to train “volunteer replicators” members who themselves train new groups. They have been responsible for SfC “going viral” In treatment zones the take up rate is 40.5% of women – by comparison in other similar approaches such as microcredit, the take up rate is 15% to 22.5%.

But the replicators have unexpectedly ‘spilled over’ into control villages, far away from a treatment village. This may mess up the control zones by “contaminating” the sample for the RCT, but it’s potentially good news for the women in those villages, and a testament to the attraction of savings schemes like SfC.

Depending on how strict a definition of a Saving for Change group we used (other traditional groups resemble SfC groups), we see a take up rate in control zones varying from 6% to 12% of women. So how did that happen? Did a conversation in the market lead to the replicator offering to go and create a new group there? Did a member get married, move to another village and start a group there? Did a woman decide to help her daughter in another village to set up a group? Traveling to another village to form a group is challenging for many Malian women, yet SfC groups were created with no encouragement or promotion from the project, no visits from paid field agents.

We also found that women who are more socially integrated and already have an income generating activity are more likely to join earlier, but that more marginalized women do indeed join later on. When women want to save money together, they find a way to make it happen.

Are members of SFC more resilient?

Whatever your own personal definition of resilience may be, in the Sahel any sign of resilience is a success. The study took place in the Segou region of Mali, where 40% of the households experienced a ‘shock’ last year (food price increase, drought, or illness) and 40% are food insecure (unable to produce or buy nutritious food). Households in SfC villages experienced an 8% increase in reported food security and were also eating more during the hungry season – spending 39¢ more per adult per week on food during this difficult time of year and eliminating the seasonal dip. In Mali 39¢ buys you a plate of nutritious beans or a few large cassava roots. We also found that this impact is greatest for one of the most marginalized groups of women, those women married to younger brothers in large households.

Mali, where 40% of the households experienced a ‘shock’ last year (food price increase, drought, or illness) and 40% are food insecure (unable to produce or buy nutritious food). Households in SfC villages experienced an 8% increase in reported food security and were also eating more during the hungry season – spending 39¢ more per adult per week on food during this difficult time of year and eliminating the seasonal dip. In Mali 39¢ buys you a plate of nutritious beans or a few large cassava roots. We also found that this impact is greatest for one of the most marginalized groups of women, those women married to younger brothers in large households.

From my point of view as a program manager, I see a value in combining an RCT with a qualitative study because I need to know if the program produces the impacts we designed it for and if it does not, what needs to be corrected. However I do have a lot of questions around the findings, which I regularly debate with my Monitoring, Evaluating and Learning colleagues. That being said, would I run another RCT if a donor asked for (and funded!) one? Why not? Would I look for funding to run another RCT? Not necessarily – there are other less expensive tools to measure program impacts. But for the time being, I’ll say with the confidence that only statistical evidence can give me: belonging to a savings group does make your life better!

Sophie Romana. with Janina Matuzeski and Clelia Anna Mannino. Today also sees an important Mali donor conference. Oxfam report here.

May 14, 2013

How to Plan when you don’t know what is going to happen? Redesigning aid for complex systems

They’re funny things, speaker tours. On the face of it, you go from venue to venue, churning out the same presentation – more wonk-n-roll than rock-n-roll. But you are also testing your arguments, adding slides where there are holes, deleting ones that don’t work. Before long the talk has morphed into something very different.

So where did I end up after my most recent attempt to promote FP2P in the US and Canada? The basic talk is still ‘What’s Hot and What’s Not in Development’ – the title I’ve used in UK, India, South Africa etc. But the content has evolved. In particular, the question of complex systems provoked by far the most discussion.

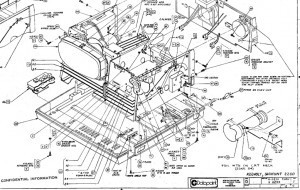

I started off with the infamous US military mindmap of Afghanistan. Although ridiculed at the time, the map looks like a genuine and nuanced effort to understand the country and is probably fairly typical of the complexity of power and relationships in any given country. The point is that such a system is complex, not complicated. Complicated means if you study it hard, you can predict what happens when you intervene. In contrast a complex system has so many feedback loops and uncertainties that you can never know how it will react to a stimulus (say $100m in aid, or an invasion….).

I started off with the infamous US military mindmap of Afghanistan. Although ridiculed at the time, the map looks like a genuine and nuanced effort to understand the country and is probably fairly typical of the complexity of power and relationships in any given country. The point is that such a system is complex, not complicated. Complicated means if you study it hard, you can predict what happens when you intervene. In contrast a complex system has so many feedback loops and uncertainties that you can never know how it will react to a stimulus (say $100m in aid, or an invasion….).

The crucial point is that most political, social and economic systems look like the map. Yet the aid business insists on pursuing a linear model of change, either explicitly, or implicitly because a ‘good’ funding application has a clear set of activities, outputs, outcomes and a MEL system that can attribute any change to the project’s activities – a highly linear approach. Other organizations – say forest fire managers, or the military, seem more able to cope with complexity, although I found out from a woman in one seminar who had served in Afghanistan that the power map was actually drawn up by a consultant, who was promptly sacked after showing the slide to General Petraeus, so maybe the soldiers aren’t so comfortable with complexity after all.

In denying complexity is obliged either to seek islands of linearity in a complex system (vaccines, bed nets), which may not always be the most useful or effective places to engage, or to lie – writing up project reports to turn the experience of ‘making it up as you go along’ that epitomises working in complex systems into the magical world of linear project implementation, ‘roll out’, ‘best practice’ and all the rest. That not only wastes a lot of staff time and energy, it also reduces the ability to learn about how to work best in complex systems.

So how should the aid system change? Overall, we need to think though ‘How to plan when you don’t know what is going to happen’ (my best effort at explaining complexity without resorting to jargon). Here are my bullet points, and brief explanations:

Fast feedback: if you don’t know what is going to happen, you have to detect changes in real time, but also have the institutions to respond to that information (as was not the case recently in the Sahel).

information (as was not the case recently in the Sahel).

Focus on problems, not solutions: Drawing on Matt Andrews’ work, the role of outsiders is to identify and amplify problems, but leave the search for solutions to local institutions. (At the World Bank, Shanta Devarajan pointed out the contradiction between this approach and NGOs’ preference for big, simple solutions – end land grabs, no to user fees. Ouch.)

Rules of thumb, not best practice toolkits: I am told that the US marines do not go into combat brandishing Oxfam toolkits and online resources on best practice. They operate on rules of thumb – take the high ground, stay in communications and keep moving. They improvise the rest. Aid workers on the ground operate far more like this than our project reports admit. If we were honest about it, we could have a better discussion on how to improve those rules of thumb.

Some possible approaches that spring to mind (and I would love to hear examples of others)

Work on the ‘enabling environment’ rather than specific projects: things like norms, rights or access to information

Evolutionary/Venture Capitalist approach: run multiple experiments and then zero in on what seems to be working best. Example, the Chukua Hatua project in Tanzania

Convening and Brokering: Get dissimilar local players together to find solutions – the outsiders’ job is to support that search, not do it themselves. Example, the TAJWSS water project in Tajikistan

But any attempt to move in this direction raises some fundamental challenges to the current structures of the aid industry:

Results for grown ups: The current approach to measuring results favours linearity. But rejecting results altogether is the wrong approach – both  because even those who recognize the central role of complex systems still want to know if they’re doing any good, and because the results people control the cash. No results, no funding. We need to get much better at ‘counting what counts’, and reclaim the idea of ‘rigour’ for qualitative and other methods better suited to complex systems.

because even those who recognize the central role of complex systems still want to know if they’re doing any good, and because the results people control the cash. No results, no funding. We need to get much better at ‘counting what counts’, and reclaim the idea of ‘rigour’ for qualitative and other methods better suited to complex systems.

Who to employ? Risk-taking, entrepreneurial, maverick searcher types have a hard time in an aid business dominated by bureaucratic procedures and risk aversion. Moreover, working in complex systems requires deep local knowledge of formal and informal power maps, something expats on a two or three year posting are unlikely to acquire. How do we turn the tables to attract and retain searchers, and value locally embedded knowledge?

Short Term v Long Term: Funding and project cycles are short term, change in complex systems is often long term. How can we bridge the gap, for example by combining good, plausible stories about the short term, with more rigorous impact assessment in the long term (how often do we go back and study the effects of an intervention 10 or 20 years after the funding has ended?)

How to keep/build political support given that working in complex systems means acknowledging a lack of control over what takes place and limits to attribution (no you can’t ‘badge’ the Arab Spring as created by Oxfam, USAID or anyone else, sorry). It also means greater tolerance of failure – a venture capitalist approach means accepting 9 failed start-ups for every 1 big success, but imagine what aid critics would do with a 90% failure rate. And how do we communicate and sell this approach to the public after systematically dumbing down the aid and development story for decades? (From buy a goat and save the world, to a post-goat narrative….)

Ben Ramalingam has been thinking about this for years, and writing about it on his Aid on the Edge of Chaos blog. His book of the same name is due out later this year, so let’s hope it can settle a lot of these issues (and doubtless raise many more).

May 13, 2013

Impressions of North America’s aid and development scene: the good, the bad and the ugly

Just got back from a two week immersion in the US & Canada aid and development scene (well, the East Coast version, anyway). Boston, New York, Washington and Ottawa, talking at universities, NGOs, multilaterals and aid agencies and experiencing a wonk version of groundhog day + powerpoint, brought on by giving the same presentation 16 times (I’m getting pretty good at it now).

Washington and Ottawa, talking at universities, NGOs, multilaterals and aid agencies and experiencing a wonk version of groundhog day + powerpoint, brought on by giving the same presentation 16 times (I’m getting pretty good at it now).

Overall impressions? Lots of really smart and committed people caught between what Oxfam America’s Greg Adams calls the ‘high and low politics’ of aid. High politics is about policy – thoughtful discussions of how to make aid better; low politics is fending off the ‘aid doesn’t work/charity begins at home’ counter attack from right wingers and fiscal conservatives.

In Canada, it felt like low politics is in the ascendant – the aid community seems besieged as the government takes the axe to a number of institutions, including ‘merging’ CIDA with the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (feels more like an acquisition than a merger).

The US felt more finely balanced – lots of good reform proposals coming from the Administration, and a really interesting discussion with USAID on how to move from funding relationships to partnerships like its triangular relationship with Brazil, where USAID and Brazil jointly support aid programmes in Lusophone Africa. They’re wondering how to expand that approach as more middle income countries set up their own aid agencies.

For all my admiration for their blogging, I found my day or so at the World Bank pretty depressing in terms of politics and policy. The Bank seems stuck in a ‘technology + private sector = solution to everything’ mindset. I’m not against either, but you have to take politics, power, institutions etc at least as seriously.

A Band for the Bank?

I’ve already covered my exchange with Marcelo Giugnale. At my staff talk, Bank uberblogger Shanta Devarajan stated ‘poverty is a series of government failures’ and came out with examples where ‘governments intervene, but make people worse off.’ Unfortunately his conclusion seemed not to be that the Bank should help strengthen states, but that it should bypass governments/find private sector solutions to everything. An approach that is unlikely to reduce inequality and has little historical foundation, I fear.

As for the evidence debate, Shanta reckoned ‘results always have to be relative to a counterfactual – that’s what they’re about’. So how do you assess things with no counterfactual, like the fall of apartheid, or the invasion of Afghanistan? Or the impact of international conventions on the rights of women?

[update: Shanta says I got him all wrong - see his comment below]

Meanwhile a discussion with the team producing the forthcoming World Development Report on Managing Risk suggested that the Bank still cannot get past its traditional technocratic approach of ‘if a state wants to improve, here are some suggestions’. On fragile states, what if a state isn’t interested in solutions? Reply – private sector + foreign investment. Oh dear. No theory of change for how fragile states turn around, finding nuclei of good governance in otherwise fragile states, building coalitions of civil society, faith-based institutions, media, academia, traditional authorities, shifting norms in the next generation. Nope, just a fairly barren state v private sector dichotomy. Still, these were rushed conversations, and I’d be delighted to be proved wrong.

Other impressions? Great intellectual capacity at the UN, frustrated by the lack of clarity and political constraints of the system. A professor who still remembers her first class with Robert Chambers. Robert had pinned up a map of the world, with the North at the bottom. Then he just sat in a corner as his new students filed in and commented that he’d put the map up upside down. You can imagine the rest. Genius.

And a great suggestion from someone (sorry can’t remember who) – a ‘voices of the activists’ study on lightbulb moments: what were the life-changing experiences that set you on your present course – a meeting with an individual? A personal experience of violence or injustice? A seminar (hey, it happens)? Something you read? That is research I would love to read.

experiences that set you on your present course – a meeting with an individual? A personal experience of violence or injustice? A seminar (hey, it happens)? Something you read? That is research I would love to read.

Dogs that didn’t bark? Surprisingly little discussion on the rise of China, depressingly little on climate change. Otherwise, my over-riding impression of the trip is the network of smart, committed people who read this blog, comment, think and argue with passion. Thankyou – you have definitely renewed my commitment to keeping this forum going, even though it can be daunting when (as this morning) I wake up jetlagged, with nothing ready to post. Normal service will be resumed tomorrow.

May 10, 2013

Blogging in big bureaucracies round two: the view from the World Bank

Had a useful discussion with the World Bank’s social media team this week, off the back of Tuesday’s post on the struggles that the UN seems to be havingin getting its people blogging (actually, the comments on that post suggest there are lots of UN blogs, but most of them seem to be outside New York).

havingin getting its people blogging (actually, the comments on that post suggest there are lots of UN blogs, but most of them seem to be outside New York).

How, I asked, has the World Bank apparently cracked it, with 300 bloggers on 32 separate blogs?

Jim Rosenberg, head of the team, argued that this all dates back to 2010, and the World Bank’s broader shift to an open access policy – a default position in favour of external publication, which is slowly gaining ground in Oxfam, but seemingly struggling to get much traction in the UN. Jim characterised the basic message as ‘if you’re good enough to talk at a conference, you should be able to write a blog post.’

The team distinguished various kinds of blog – ‘comms blogging’ to broadcast the Bank’s messages; sectoral blogging, targeting particular demographics such as youth, and ‘community of practice’ blogging for peers on themes such as education or governance (where I have a regular slot).

The discussion revealed the ‘blogging culture’ as an emergent phenomenon, unevenly distributed across the Bank. A crucial part in spreading the culture was the success of early adopters such as Shanta Devarajan and Michael Trucano. But there are still ‘dark zones’, often determined by the culture of a particular unit, or the attitude of its boss.

The Bank has tried to put incentives in place, eg including blogging as a performance objective, but it is uphill work. Many academic disciplines still disapprove. Many Bank staff are still risk averse and reluctant to upset people, especially their bosses. As a result, there are few younger bloggers, and the space is dominated by the senior experts (like Shanta). These celebrity bloggers are great advocates for blogging and very hard to rein in, and so created space for bloggers, but their very status is also inadvertently inhibiting new entrants. ‘No-one under 40 blogs at the Bank’, one staffer told me at another meeting – many of them are on short term contracts and don’t want to endanger their chance of a permanent job. Tricky.

Bloggers described a three tier risk management approach, which is very similar to my own:

- No go areas: so sensitive that blogging on them will just start a debilitating fight. Not worth it.

- ‘Professional courtesy’: run drafts past issue leads and experts to correct mistakes and avoid fights

- Let it flow: low risk areas, just go for it.

As to the comparison with the UN, some reckoned that, while the Bank has a lot of government staff looking over their shoulders, the UN system is even worse and ‘more political’. They also felt that the Bank bloggers are often recognized experts, who are leading figures in global communities of practice, and that status to some extent insulates them from internal pressures.

As to the comparison with the UN, some reckoned that, while the Bank has a lot of government staff looking over their shoulders, the UN system is even worse and ‘more political’. They also felt that the Bank bloggers are often recognized experts, who are leading figures in global communities of practice, and that status to some extent insulates them from internal pressures.

One of the key differences is that the Bank has worked hard to sort out its comms governance. Who can start an official twitter account? Who can blog? The system needs to have clear, transparent rules to avoid the UNICEF moment of a comms person who thought (wrongly) that the UN banned blogging by staff.

The team clammed up a bit when I raised some comments on the previous post, which argued that the Bank is doing much worse on twitter than it is on blogging. They seem to use twitter in a more top down way, to ‘amplify’ blog content and corporate messages.

What happens when bloggers screw up? The social media team sees part of its remit as rushing to their defence, and have also won some key test case battles (often, they stress, with support of management), heading off attempts to shut down the more edgy bloggers, even when the result is potentially awkward for the Bank.

The culture feels fairly macho – self-confident experts willing to blog, and shrug off any criticisms. So obvious question – how many of the 300 bloggers are women? And (tut tut) they didn’t know – some room for improvement there, I think. Interesting gender stat on twitter – men are twice as likely to tweet; women are three times more likely to take their tweets down.

There has been lots of interest in the UN post, including a nice follow up post from Ian Thorpe of UNDP. Seems like a lot of people are thinking about the challenges of blogging from within institutions.

But what we didn’t get on to, and which I would love to hear from people on, is what comes next. Is there some successor to blogging in the wings? Or will blogging just become a permanent part of the landscape, alongside more traditional channels. If so, I haven’t seen it. Please enlighten me peeps (and tweeps).

May 9, 2013

How have a series of global shocks changed the way we think about development?

This piece appears in today’s Ottawa Citizen

The past five years has been a period of extraordinary global turbulence.

The turmoil has struck as three “shocks” — the financial crisis, a breakdown in the world food system, and the Arab Spring — combined with a slow motion train wreck in the form of the seemingly inexorable onset of chaotic climate change. Together, these are having a profound impact on our understanding of how the world works.

Just how much has changed was one of the overriding impressions from updating my book From Poverty to Power: How Active Citizens and Effective States Can Change the World, first published in 2008.

The global financial crisis was a watershed event. It triggered historic geopolitical change in the rise of the emerging powers such as China and India. It also drew attention to the risks of an excessively “financialized” global economy; but it failed to lead to a reining in of the excessive size and volatility of “hot money,” condemning us to future financial crises, possibly starting with Europe in the coming months.

also drew attention to the risks of an excessively “financialized” global economy; but it failed to lead to a reining in of the excessive size and volatility of “hot money,” condemning us to future financial crises, possibly starting with Europe in the coming months.

Simultaneous with the financial crisis, the world witnessed a food price spike. In many countries this traumatized the lives of poor people to a much greater extent than the shenanigans on Wall Street, and reversed decades of low and falling prices, threatening long-term progress on hunger and nutrition. That has led to renewed attention to the basic issues of food and hunger, and some unfortunate side effects such as “land grabs” across the developing world by investors from rich countries.

The Arab Spring confirmed the importance of active citizens in driving social and political change, and made us think much harder about the role of women (who were very active) in majority-Muslim societies.

Taken together, these events have made us much more aware of the impact of volatility, risk and vulnerability on the lives of poor people. That leads both to a focus on trying to prevent shocks from occurring in the first place and to dampen their impacts when they occur. “Shock absorbers,” from social protection to food reserves, to help for poor farmers to adapt to climate change, have become a much more central part of development thinking.

Inequality and redistribution have become mainstream debates, with even the International Monetary Fund weighing in on how high levels of inequality imperil both growth and stability. And the levels are breathtaking. I recently calculated that the amount the world’s richest 100 people added to their wealth in 2012 ($240 billion) would be enough to end extreme poverty for the 1.4 billion people living below the international $1.25 a day poverty line ($66 billion according to the Brookings Institution), four times over! With that focus has come renewed interest in how tax systems and reforms can reduce or exacerbate inequality, both at the national level, and through the international system of tax havens.

Finally, these changes are feeding into a deeper questioning of the nature of poverty itself. As the World Bank’s path-breaking and unsurpassed “Voices of the Poor” study in the 1990s showed, to be poor is as much about anxiety, vulnerability and shame as about income levels. And that anxiety has only been heightened by the turmoil of recent years.

Finally, these changes are feeding into a deeper questioning of the nature of poverty itself. As the World Bank’s path-breaking and unsurpassed “Voices of the Poor” study in the 1990s showed, to be poor is as much about anxiety, vulnerability and shame as about income levels. And that anxiety has only been heightened by the turmoil of recent years.

In response, governments around the world increasingly acknowledge the limitations of income or GDP per capita as a measure of well-being, and are developing much more sophisticated metrics — aid agencies are rather lagging behind national governments in this regard.

This more subjective, people-based understanding of well and ill-being may be one explanation for a greatly increased focus on issues of power and agency in development, often linked to issues of the basic rights that are (or are not) enjoyed by poor people. The spread of “rights thinking” on areas such as gender, disability, ethnicity and sexuality appears to be a global phenomenon, bringing significant changes in national legislation and practice in many countries. The challenge for aid agencies is to ensure that their plans and methods, including the pressure to demonstrate “results” and “value for money” reflect this more human understanding of the nature of poverty and power. As the title of my book makes clear, we need to move “from poverty to power” in both our thinking and our practice.

Are we successfully completing an “age of development” or seeing the prize slip from humanity’s hands in an economic and climatic meltdown? It is hard to recall a period when developmental optimism and pessimism co-existed to such a high degree.

The stakes could not be higher. The coming decades will show whether poverty enters the history books, joining slavery and the fight for women’s suffrage, or whether an age of chaos and scarcity starts to reverse the wonderful progress of the last 70 years.

Duncan Green is the author of the book From Poverty to Power and Oxfam GB’s senior strategic adviser. He is launching his book and giving a public lecture at the University of Ottawa on Friday May 10. The event is sold-out, but a recording of the event will be made available soon on YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/user/CCICable.

May 8, 2013

Is power and politics a massive distraction? Crossing swords with the World Bank.

This post is written on the hoof, dashing between presentations, so please pardon the rough edges.

Yesterday I shared a platform with Marcelo Giugale, the World Bank’s Africa Director for Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (right). We were coming from very different places, some might say different planets, which is always stimulating. I did my standard power and politics spiel, focusing on multidimensional poverty, inequality and complex systems and their implications for aid agencies (more on that to follow).

coming from very different places, some might say different planets, which is always stimulating. I did my standard power and politics spiel, focusing on multidimensional poverty, inequality and complex systems and their implications for aid agencies (more on that to follow).

Marcelo responded by saying that this was all a massive distraction, and that we should keep our eyes on the prize of ending poverty. And on this he was relentlessly upbeat, optimistic and pretty apolitical. ‘We can end poverty without blasting the system… we have the technology’ he said.

Marcelo argued that six key developments have made this possible:

We will know the poor by name, individually. Thanks to a combination of technology and the widespread introduction of cash transfers, governments are increasingly registering all their poor citizens (the mega example being India’s biometric identity card programme – below, left). This allows them to scale up transfers rapidly in the event of shocks.

We can determine impact, not just outcome. He defined impact as ‘that subset of outcomes that would not have happened without the intervention’ and pointed out that many of them are negative. Eg aid agencies give aid for education, so the education budget is redirected to something less worthwhile.

We can determine impact, not just outcome. He defined impact as ‘that subset of outcomes that would not have happened without the intervention’ and pointed out that many of them are negative. Eg aid agencies give aid for education, so the education budget is redirected to something less worthwhile.‘The time has come to link people with their natural resources.’ The World Bank seems to be getting behind the ‘doing an Alaska’ proposal to distribute natural resource revenues straight into the hands of poor people. Interestingly their power analysis suggests that the most likely way to overcome domestic political barriers (politicians not wanting to give up their slush funds) is by persuading ‘desperate oppositions’ who do not expect to win to adopt it as a last throw of the dice. Something a bit similar led to the introduction of India’s renowned Rural Employment Guarantee scheme. They think early adopters will ease the political logjam and increase pressure on neighbouring countries to follow suit.

Equity not Equality: the way to steer a course through the politically polarized terrain of inequality is to focus on children. Hence the Bank’s new Human Opportunity Index, which asks ‘how important are a child’s personal circumstances over which he/she has no control or responsibility (e.g., gender, family income, skin colour, birthplace, etc), to his/her probability to access the services without which he/she can’t succeed in life (things like completing 6th grade on time or having potable water in the first two years of life)?’ I’m not sure about this – is it a way to get at the real causes of inequality, breaking the transmission between generations that has grown so much more rigid in recent years. Or is it a convenient way of dodging politically contentious issues of distribution and redistribution, kicking the can down the road with a new version of the kind of ‘equality of opportunity’ approach (aka the American Dream), which I thought we had left behind?

Focus on non-cognitive skills, such as punctuality, respect and dedication to understand the reasons for success. Why? Because they are important and becoming more measurable.

A proliferating set of ‘standards’ for public expenditure will help governments to introduce results-based payments and budgeting.

Most of this is taken from his (freely downloadable) 2010 book The Day After Tomorrow.

Several things struck me about his presentation. Firstly, the overwhelming can-do optimism is very seductive. And the emphasis on technology neatly avoids any difficult political decisions. This is a happy technocratic world of win-wins. In contrast my presentation was all about difficult politics – I’m not sure I had the best tunes.

avoids any difficult political decisions. This is a happy technocratic world of win-wins. In contrast my presentation was all about difficult politics – I’m not sure I had the best tunes.

But in the end, I didn’t buy a lot of it – by invoking the use of ‘we’, as in ‘we can end poverty, by fixing X or Y’, he reminded me of Pierre Jacquet’s great question – who is we? And why assume that ‘we’ have a common agenda?

Marcelo has a remarkably outsiderish view of the ‘we’ – in a follow-up email he defined them as “All those that care about ending poverty, not just 19th Street, but NGOs, advocacy groups, faith-based organizations, the college kid that spends a year in a developing country giving a hand, etc”.

In contrast, I would argue that these are all bit players: the key ‘we’ is within developing countries – political actors, civil society organizations, faith leaders and the rest. There, assumptions of a common agenda are likely to prove unfounded. That’s why we need to go back to school on power and politics. Which all reminded me of Matt Andrews’ critique of the World Bank’s efforts to ‘roll out best practice’ on institutional reform, including the institutions needed to introduce these new technologies.

Today I’m launching the book at the World Bank at 12.30, so expect the debates to continue……

May 7, 2013

Why are there so few bloggers at the UN? A conversation with staff.

I spent a busy few days in New York last week, talking to (well, OK, mainly talking at) about 200 UN staff at various meetings in UN Women, UNDP and UNICEF. There was a lot of energy in the room (and even outside the room – people at UNDP spilled over into the corridor), and plenty of probing viva-like questions and comments.

UNICEF. There was a lot of energy in the room (and even outside the room – people at UNDP spilled over into the corridor), and plenty of probing viva-like questions and comments.

Which is what I expected, because intellectually, I think the UN is in an enormously productive phase. Just thinking back over recent posts on this blog, there is UNRISD on Social and Solidarity Economy, UNCTAD on finance-driven globalization, UNDP on the rise of the South, UN Women on women and the justice system and regular appearances by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food. Taken as a whole, this output is innovative and important, both challenging received wisdom and coming up with some of the new ideas and alternatives we so desperately need.

So where are the UN’s bloggers? UN staff certainly read blogs (including this one, I think a lot of people came along just to see what a blogaholic looks like in the flesh). But they hardly ever write them – the only one I regularly read is Ian Thorpe’s excellent ‘KM on a Dollar a Day’ (the KM is Knowledge Management), but that is so unbranded I’m not even sure the UN knows he’s doing it. The only official UN blog that comes up on a quick search is aimed at the general public – photos etc – not much there for wonks.

In contrast, I’m speaking at the World Bank tomorrow and suggested a chat to a few of its bloggers. Tricky they said – there’s 300 of them. Why the enormous difference? Is this about a greater degree of overall confidence and agency among Bank staff, or the institutional and political constraints operating in both institutions, or a mix of the two?

You want me to blog? Must I?

This awoke painful memories of a ‘bloggers’ breakfast‘ between CGD and Oxfam America last year. As we went round the table, CGD researchers raved about how much they enjoyed blogging, the to and fro of debate, the interaction etc. The Oxfamistas came over all Eeyore and said how anxious they felt about bloggin in case they make mistakes or get the organization (or themselves) into trouble. (To be fair, Oxfam America blogs have come a long way since then, including hiring Jennifer Lentfer of How Matters).

The UN staff seem to be in an even more extreme version of that defensive crouch, so worried about going wrong that they don’t even try. One person in a comms team even claimed that blogging is actually prohibited in the UN, only to be told that no, social media was an official priority (they’re doing better on twitter – UNICEF has 1.8m followers). And there’s plenty of would-be bloggers around – when I asked how many wrote private blogs, 4 out of 50 UNICEF people raised their hands.

So (assuming there isn’t some secret management conspiracy to stifle would-be bloggers), how could the UN start blogging, they asked? A few ideas:

Blogging only works if you move ‘from permission to forgiveness’, as the management cliché has it. But in a large institution with a reputation to protect, you can’t just let anyone start blogging under your logo – they need to earn it. How to marry risk management and the freedom and speed needed to blog? A probation period is a good compromise – for the first six months of this blog, I had to get sign off from Oxfam International for every post, then we relaxed a bit. Now if I screw up too often, I know they’ll rein me in, but if I don’t rattle a few Oxfam cages, I know I’m being too bland. There’s a balance to be struck.

Don’t force everyone to blog – if people see it as a chore, the resulting posts are guaranteed to be unreadable. Why not start with those four private bloggers and get them to kick off the blog?

Give them time: blogs take months to establish, as word of mouth spreads and readers mount up (or not – the market is merciless).

Give them a face: anonymous institutional blogs don’t usually work. Blogs need a personality. If you haven’t got anyone as obsessive as me, try the Global Dashboard model – a stable of bloggers, with an option to sign up the ones you like. That takes the pressure off a bit.

Any more tips?

This should really matter to the UN, in my view. Good research and policy papers don’t disseminate themselves, and the blogosphere is an increasingly important way to get your messages out. By self-censoring in this way, the UN is reducing the impact of some really excellent work. Consider yourselves lobbied.

This is just a subset of a much wider issue – how to attract and retain mavericks/original thinkers in large bureaucratic aid institutions. But my colleague (and uber maverick) Nicholas Colloff has complained about the growing length of these posts, so (see how interactive this is?) I’ll leave that for another time.

May 6, 2013

How to end foreign aid and avoid a punch-up

An edited version of this piece appeared on the Guardian’s Comment is Free site on Saturday

The spat between South Africa and Britain over ending its (very small) aid programme has sparked another round of debate about whether British aid should be going to middle income countries (the last round was over aid to India, which seems to particularly rile the Daily Mail).

should be going to middle income countries (the last round was over aid to India, which seems to particularly rile the Daily Mail).

But whatever the rights and wrongs of ending aid to South Africa (whose economy is growing slowly, but with sky high levels of inequality and 10 per cent of all the world’s people living with HIV and Aids), aid agencies are inevitably going to have to shift money around as the world changes. Countries rise and fall, aid priorities change and new opportunities (like the opening up of Myanmar) will arise, to which aid should of course respond.

That churning process is accelerating as more and more countries reduce their dependence on aid thanks to economic growth, rising revenues from oil and gas and surging remittances from their migrant workers overseas. Those upward curves contrast with falling aid volumes. Total global aid flows have been falling for the last two years as, with the sole glorious exception of the UK, the ‘Austerians’ in what are sometimes known as ‘the formerly rich countries’ take the axe to aid spending.

What’s more, many developing country governments can’t wait to end aid – it affronts the dignity of the Big Men (as they usually are) in charge to be seen as asking for handouts. As two Ugandan ministers once proudly told me ‘when 60% of our revenues came from aid, we had to go to the World Bank on both knees. Now we’ve got it down to 30%.’ (Unfortunately, I blew it by joking ‘ah, so do you just go on one knee now, then?’ They were not amused.)

So the issue is not whether aid partnerships sometimes have to end, but how. Oxfam has some ideas on that – several pages of guidelines on ‘exit planning’ in fact. They are about ending funding to particular grassroots organisations, but they offer useful lessons for DFID and others contemplating exits from entire countries. Talk to the partner from the outset, help them fill any organisational gaps and weaknesses before you go; agree (don’t impose) a clear timetable for phasing out funding and crucially, agree what kind of relationship you want once the cash tap has been turned off. Because as one Oxfam partner from Pakistan put it, ‘We want to be treated as a “relationship” and not just as a “partner”’. Partnerships are for projects, but relationships go beyond that. We should have a relationship in the future, even if there is no project money.’‘ Sadly, the unpleasantness over DFID’s exit from South Africa means that remaining relationship has got off to a rocky start.

SA Pres demonstrates what he'd like to do to DFID

I imagine DFID has similar guidelines, but those can’t legislate for ministers shooting from the hip (or if conspiracy theorists are to be believed, throwing a bone to the Tory right ahead of local elections last week). Still, if civil servants in the land of ‘Yes Minister’ can’t manage their political masters, what are we coming to?

Joking aside, this matters. Aid agencies need a clear understanding of what constitutes a responsible exit. After all, aid should bequeath a legacy of trust and friendship between the UK and the rising powers of Africa and Asia, (who incidentally, we are going to need in future), but in this case that legacy has been (temporarily, I hope) squandered. Ending the aid relationship should be a moment of mutual celebration, not public mud-slinging.

May 3, 2013

The Limits of Institutional Reform in Development: a big new book by Matt Andrews

There’s nothing like an impending meeting with the author to make you dig out your scrounged review copy of his book. So I spent my flight to Boston last week reading Limits (sorry the full title is just too clunky). And luckily for the dinner conversation, I loved it.

last week reading Limits (sorry the full title is just too clunky). And luckily for the dinner conversation, I loved it.

Limits is about why change doesn’t happen, and how it could. It synthesizes the ‘groundswell’ of disquiet about the failure of the governance and institutional reforms that have been promoted for many years now by aid agencies like the World Bank. And it’s not just a whinge – there are plenty of ideas for how aid agencies can do better. The book is particularly useful for those working on fragile states – lots of the positive examples (as well as some failures) come from Afghanistan, Ivory Coast and elsewhere, although there is a bit of ‘why can’t everywhere be more like Rwanda?’ in there too.

Overall, the approach reminded me of Dani Rodrik’s great book, In Search of Prosperity, and Matt says Rodrik (a fellow Harvard prof) was influential in pushing him to nail down the always-elusive ‘so whats’.

Limits summarizes research and thinking from disparate disciplines, with lots of fascinating case studies (he’s put in the legwork to build a serious empirical basis for his conclusions). His big idea is captured in a new acronym, PDIA (Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation), which, as he pointed out, is similar to the Participatory Institutional Appraisal idea I raised in a recent blog. I’m not sure if PDIA will catch on – it could have done with a snappier title, as could the book – but the content is really important if you are interested in aid, institutions or governance.

So what does it say? Firstly, that we have a big failure on our hands. The spate of projects and programmes around institutional reform has at best a mixed record of success; in many countries institutions have actually deteriorated in terms of effectiveness, corruption etc.

Limits argues that governments’ real motive for committing to reforms is often not about improving performance, but is actually about ‘signalling’ a willingness to ‘modernize’ (which usually means move power from state to market, deregulation and privatization, increase budget controls and accountability and reduce debt). It often involves ‘isomorphic mimicry’ – if poor countries mimic the institutions of rich ones, then – voila! – they too will become rich. The trouble is that the current aid system rewards such signalling. When the reform fails, a new government typically introduces a new round of signalling and off we go again.

Uganda is the Daniel Day Lewis of isomorphic mimicry: according to the think tank Global Integrity, it has the best anti-corruption laws in the world, (it scores 99/100), but came 126th in the 2008 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index. Oops. More generally ‘developing countries are now more likely than developed countries to boast systems that resemble international best practice.’ So if laws and best practice were decisive, Uganda would rapidly be overtaking Norway.

Such reforms as do take place happen on the fringes of real power ‘in areas that are externally visible and where reform is influenced by concentrated sets of reform champions.’ Eg the ‘ceremonial’ world of Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs). Or perhaps (at the risk of sounding like a bad loser) the MDGs…..

Aid agencies often focus on identifying and supporting a small number of champions, but Limits debunks such ‘decent chap-ism’ as an ‘illusory promise’. He quotes Brecht’s ‘Life of Galileo’: ‘Unhappy is the land that has no heroes….. No. Unhappy is the land that needs heroes.’

just follow the blueprint and you'll be fine

If not single heroes, then what kind of leadership is needed for genuine reform? ‘Institutional entrepreneurs’ are essential, but there’s a paradox – those in power benefit from the status quo, so are unlikely to support change. That can change ‘when something creates a bridge between these highly embedded agents with power and low embedded agents with new ideas.’ And they often need convenors and brokers to help them overcome barriers of distrust and status.

But there’s a further group – the ‘distributed agents’ that are required to implement what the entrepreneurs come up with. And for ownership and relevance, they need to be engaged from the outset, not as ‘adopters’.

Otherwise, ‘reforms often progress well when under the control of champions in concentrated agencies directly involved in designing change, but falter when deconcentrated agencies must implement what these agencies design.’

The book examines the broader contexts for institutional reform, pointing out that there are always ‘multiple logics’ that govern how people think and act. Sometimes one logic is dominant, at other times there are strong competing alternative logics. The job of change agents, whether internal or external, is to back the good guys when there is genuine competition, but otherwise incubate alternative logics to challenge a damaging status quo. Either approach needs a deep understanding of what is there, rather than an imported blueprint for best practice.

Matt recognizes that shocks are important drivers of change, but the argument goes into much more interesting terrain than the standard spiel. Shocks disrupt, weakening the dominant logic and testing the viability of alternatives. That creates the conditions for change, but the change process itself needs to be broad and incremental – how do discontinuity and gradualism fit together? I think the idea is that shocks create the conditions for reform, but reform itself can’t be sudden.

But there may be trade-offs, as the appetite for reform may fall away soon after a shock, so the question (which the book doesn’t answer) is what do reformers need to put in place before the window of opportunity closes, to pave the way for that longer, more inclusive process? I’ve got a horrible feeling the rise of Thatcherism may provide the perfect case study here…..

What happens after shocks is a five stage process (this is new to me, from the literature on institutional change):

Deinstitutionalization: encourage the growing discussion on the problems of the current model

Preinstitutionalization: groups begin innovating in search of alternative logics, involving ‘distributive agents’ (eg low ranking civil servants) to demonstrate feasibility

Theorization: proposed new institutions are explained to the broader community, needing a ‘compelling message about change.’

Diffusion: as more ‘distributive agents’ pick it up, a new consensus emerges

Reinstitutionalization: legitimacy (hegemony) is achieved. We all go off to the pub.

As to what outsiders can do, again he has some sensible recommendations, while desperately trying to avoid creating a new blueprint of his own:

Focus on identifying, highlighting and exploring problems, but leave solutions to local players. Accept that this process may take time

Provide opportunities for local actors to reflect on problems – convening and brokering

Focus on clearing out the obstacles to new approaches (deinstitutionalization)

Fund flexible learning-by-doing approaches to finding solutions

Specific suggestions include Cash on Delivery Aid, stringent tests for all ‘manifestations of good, better or best practice’ and creating institutional reform trust funds that can disburse smaller grants fast in response to evolving local processes.

At those happy moments when governments buy in to the need for reform (he cites Rwanda’s decentralization and Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (right) as examples), Andrews proposes ‘purposive muddling’ – slow, experimental and incremental approaches. Outsiders can contribute by exposing decision makers to experiences elsewhere, helping them develop hybrids best-suited to local contexts, and then test them. They can also capture and publicise successes to build momentum and buy-in.

Outsiders should also look beyond champions in positions of authority, and try and cultivate ‘mobilizers’ who connect different constituencies and spread ideas. An interesting survey of those involved in 12 different reform processes showed that leadership was far more dispersed than is customarily assumed – multiple leaders, often non-usual suspects (no-one in Afghanistan cited the president), such as those behind the scenes who brought people together and acted as catalysts.

The survey did identify external agents like aid agencies as important leaders, but only their locally-based staff, who are embedded in national contexts; no-one cares about visitors from HQ. Outsiders are more important at the start of reform processes (their influence tends to diminish after that). Not surprisingly, providing funding is their key role, with the key proviso that the funding is open ended and flexible, not tied to the ‘roll out’ of ‘best practice’. Overall however, outsiders are bit parts in the reform drama.

Discussing all this over dinner, Matt thinks we have arrived at a ‘moment’ – a coming together of dissidents from numerous disciplines to reject the logframe/best practice culture and push for something more rooted in reality. Political science, complexity theorists, aid veterans, Cash on Delivery proponents, the Development Leadership Program, the Africa Power and Politics Programme and many more are all challenging linear/blueprint thinking and proposing new and (hopefully) better alternatives.

In a nice twist, he applies PDIA to the task of persuading the aid agencies to adopt, erm, PDIA. He thinks the level of disruption to the signalling model is high, driven by growing evidence of failure. I’m not so sure. To steal from Robert Chambers ‘whose reality counts?’, for many aid donors right now, reality feels like political and financial siege, and that is fuelling the pursuit of a divisive emphasis on ‘results’. I’m not sure there will be much appetite for a movement, however well grounded in evidence, which says that the way to achieve change is to make it up as we go along (a sceptic’s version of PDIA) rather than to pursue short term, attributable results.

And (and this gets politically tricky for me), both the volume of aid and its management may also be obstacles to realigning it. Matt cites the World Bank’s ‘Learning and Innovation Loans’, which have been largely ignored, mainly because they are too small – an average of $5m, compared to $150m for other investment projects. As long as Bank staff are promoted on the basis of banking-style rules that reward the volume of aid they move, who is going to waste their time on LiLs? Then of course there is the ‘pre-programming’ model epitomised by detailed logframes and other project documents that require a pretence of predictability and linearity – all of it toxic to a PDIA approach. The increasing influence of governance indicators like the

CPIA that themselves enshrine ‘best practice’ at the heart of what we measure closes the conceptual circle and makes it even harder to conceive of new approaches.

As you may have realized from the quotes, the book’s language is pretty dense and technical. That, plus being published as an academic hardback, could easily reduce the book’s audience and impact. Any publishers willing to back a more popular version should beat a path to Matt’s door.

Finally, there is lots of overlap with my own work on power and change – the importance of power analysis/understanding local context, seizing critical junctures, convening and brokering rather than trying to go it alone, evolutionary learning-by-doing rather than single grand plans. Over dinner, we kicked around some exciting plans for working together in future – watch this space.

Matt is launching the book in the UK (London – ODI and CGD – and Manchester) from 20-22 May. Details here.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers