Duncan Green's Blog, page 219

March 20, 2013

Brazil v South Africa: what can the BRICS tell us about overcoming inequality?

The blog’s inequality week here in South Africa continues with some thoughts on inequality and the BRICS. An edited version of t his post appeared earlier this week on the FT’s Beyond BRICS blog

his post appeared earlier this week on the FT’s Beyond BRICS blog

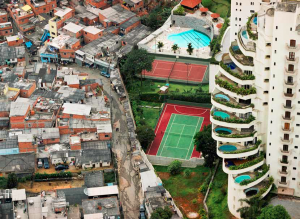

The acronym may have been cooked up in far-off New York, but the BRICS grouping of countries is starting to generate some interesting life of its own. Last week, I was in Durban, chairing a discussion between academics and activists from South Africa and Brazil ahead of the BRICS summit later this month. The topic? ‘Tackling inequality across BRICS’.

The starting point was Brazilian exceptionalism. Long held up as exhibit A in Latin America’s gross distortions of wealth, Brazil is now the only BRIC where inequality is falling (and fast – see chart). In the wider G20 group of leading economies, only 4 can boast falling inequality levels; three of them – Brazil, Argentina and Mexico – are Latin American.

The stats, captured in a new Oxfam briefing, published in conjunction with Rio’s BRICS Policy Center, are striking. Over the last decade, the incomes of the poorest Brazilians have risen more than five times faster than those of the richest (but both are rising – no zero sum games here). In the words of Brazilian poverty guru Ricardo Paes de Barros, “the incomes of individuals in the lowest decile of the income distribution is growing at Chinese rates, while the income of the richest decile grows at German rates”.

Even though GDP growth is sluggish, two weeks ago President Dilma Rousseff was able to announce the end of ‘registered extreme poverty’ – note her careful choice of words. Some Brazilian academics put this historic turnaround on a par with the New Deal in the US, or Britain’s post war creation of its welfare state.

The fine grain is just as encouraging: women’s incomes are rising faster than men’s; black people’s faster than whites’; the impoverished North-east faster than the rich South-east. Hunger is ‘largely dealt with’ according to Oxfam’s country director Simon Ticehurst, speaking in Durban, although food insecurity continues to plague communities in the northeast of Brazil. Near full employment is transforming lives, as people move from a day to day scrabble for survival into the better paid, more stable world of the formal economy. Brazil’s middle classes complain bitterly about having to pay more for maids, and even give them days off, as labour markets tighten.

Not that Brazil has become some kind of development nirvana: the quality of state education remains poor, large scale agriculture sucks up state subsidies on a far greater scale than those going to poor farmers; and despite the progress, the country is still in the world’s top 15 most unequal countries, twice as unequal as the OECD average.

Not that Brazil has become some kind of development nirvana: the quality of state education remains poor, large scale agriculture sucks up state subsidies on a far greater scale than those going to poor farmers; and despite the progress, the country is still in the world’s top 15 most unequal countries, twice as unequal as the OECD average.

Caveats aside, how did Brazil pull this off? Ticehurst and Adriana Erthal Abdenur of the BRICS Policy Center both stressed that such a transformation is complex and multi-tiered, involving all parts of state and society. This is most definitely not a magic bullet story of Brazil’s famous ‘Bolsa Familia’ social protection system, a programme of cash transfers to women in return for getting their kids vaccinated and keeping them in school, which has won admirers and imitators as far afield as New York City. UNDP estimates that such spending programmes account for under a fifth of the fall in inequality. Ticehurst argued that other critical factors include:

- The transition from military rule to democracy, which bequeathed a constitution and political process attuned to the importance of basic rights, such as the right to food

- The election of a centre-left government, led by Lula, committed to tackling poverty and inequality

- Major increases in the minimum wage, the introduction of a universal pension (particularly important in deprived rural households)

- An integrated and more effective public administration, working tightly across ministries and between the different levels of a federal, decentralized political system.

- A high level of public participation, for example in holding 19 different ministries to account on Brazil’s ‘zero hunger’ effort to achieve universal access to food, through a virtuous circle of linking poor family farms to government procurement for school feeding programmes that in turn feed poor children.

- Political and economic stability throughout the period of reforms.

In terms of economy and politics, Brazil is probably closer to South Africa than the other BRICS (commodity producer, democracy, transition from autocracy, centre left government) and the discussion inevitably centred on why South Africa has failed to emulate such successes. While there has  been substantial progress since the end of Apartheid on access to health, education and housing, inequality remains obstinately high and rising.

been substantial progress since the end of Apartheid on access to health, education and housing, inequality remains obstinately high and rising.

The two elements of Brazil’s success that South Africa seems to be missing (by a mile) are full employment and more competent administration. Patronage and corruption exist in both countries, but their extent in South Africa is undermining the state’s ability to implement policies, however well designed. Brazil, with its more diversified economy and public investments, seems able to generate jobs in a way that remains a distant dream in South Africa, which remains dependent on agribusiness and mining, neither of which generate the employment the country needs. Substantial land redistribution seems essential to tackling the jobs crisis, yet has been systematically postponed by the government in the interests of stability. Even those who manage to navigate the dilapidated education system and emerge with a degree still find it difficult to find jobs. Alarm bells are ringing, with observers warning of anything from a slow meltdown of the ANC government to an Arab Spring style uprising led by educated, jobless youth.

While all sides stressed that merely trying to transfer policies from one country to another seldom works, this kind of South-South exchange holds huge potential for helping the BRICS develop their own solutions to some of the problems such as inequality that continue to plague the old guard of the G8.

And here’s a 25m video summary of the Durban event

March 19, 2013

On inequality, let’s do the Palma (because the Gini is so last century)

What better place than South Africa to run an inequality week on the blog? Today’s guest post from Alex Cobham (left) and Andy Sumner (right) summarizes their

What better place than South Africa to run an inequality week on the blog? Today’s guest post from Alex Cobham (left) and Andy Sumner (right) summarizes their  new paper on inequality – got a feeling this one might be quite important. Tomorrow, Brazil v South Africa.

new paper on inequality – got a feeling this one might be quite important. Tomorrow, Brazil v South Africa.

There’s one measure of inequality that gets all the attention – the Gini index. The Gini was developed in the early 1900s – in fact about 100 years ago – by Italian Statistician, Corrado Gini (see pic, looks like a real party animal). A century later our paper argues that it may be time for a rethink on measuring inequality. Why?

it's no fun being a guru

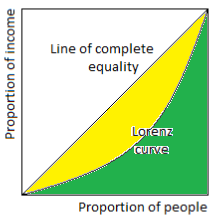

The Gini reflects the difference between the actual cumulative distribution of income, or anything else in a population, and perfect equality (the yellow area in the graphic). A Gini value of zero would mean that the distribution is completely equal and a Gini value of one would mean that one person had all the income and everyone else nothing (i.e. all of the green area would be yellow).

Simple, eh? So, what’s the difference between a country A with a Gini of 0.4 and country B with a Gini of 0.45? We can say country B (0.45) is a bit less equal than country A (0.4). What we can’t is where that inequality exists. Is it a squeezed middle? Or is it at the poor’s end of the distribution?

So if you’re a policy maker working for an incoming president elected on a mandate to address inequality and increase the share of income to the poor, the Gini won’t be a great deal of help.

It’s also long been known thanks to inequality guru Tony Atkinson that the Gini is over-sensitive to changes in the middle of the distribution – and, as a consequence, insensitive to changes at the top and bottom. That’s a problem because we care most about what happens at the top and bottom in developing countries.

So, we’ve just put out a new paper, predictably titled ‘Putting the Gini back in the Bottle?’, exploring an alternative measure for policy, which is sensitive to exactly that. We’ve called it the ‘Palma’ as it is based on the research of Chilean economist, Gabriel Palma (below). When Palma started looking at the finer grain of inequality, rather than just the Gini, he made a startling observation (see Duncan’s take on it here).

that. We’ve called it the ‘Palma’ as it is based on the research of Chilean economist, Gabriel Palma (below). When Palma started looking at the finer grain of inequality, rather than just the Gini, he made a startling observation (see Duncan’s take on it here).

He found that the ‘middle classes’ – more accurately the middle income groups between the ‘rich’ and the ‘poor’ (defined as the five ‘middle’ deciles, 5 to 9) – tend to capture around half of GNI – Gross National Income wherever you live and whenever you look. The other half of national income is shared between the richest 10% and the poorest 40% but the share of those two groups varies considerably across countries.

Palma suggested distributional politics is largely about the battle between the rich and poor for the other half of national income, and who the middle classes side with.

So, we’ve given this idea a name – ‘the Palma’ (brilliant eh?) or the Palma Ratio. It’s defined as the ratio of the richest 10% of the population’s share of gross national income (GNI), divided by the poorest 40% of the population’s share. We think this might be a more policy-relevant indicator than the Gini, especially when it comes to poverty reduction.

In the paper, we do a few things. First, we confirm the robustness of Palma’s main results over time: the remarkable stability of the middle class capture across countries, coupled with much greater variation in the 10/40 ratio.

Second, we suggest that the Palma might be a better measure for policy makers to track as it is intuitively easier to understand for policy makers and citizens alike. For a given, high Palma value, it is clear what needs to change: to narrow the gap, by raising the share of national income of the poorest 40% and/or reducing the share of the top 10%.

Third, we also present some tentative but striking evidence of a link between countries’ Palma and their rates of progress on the major Millennium Development Goal (MDG) poverty targets. More work is needed, and there are all sorts of caveats, but the results indicate that countries that reduced their Palma exhibit mean rates of progress which, compared to countries with rising Palmas, are three times higher in reducing extreme poverty and hunger, twice as high in reducing the proportion of people lacking access to improved water sources, and a third higher in reducing under-five mortality. If that isn’t worth a closer look we don’t know what is.

is.

Of course not everyone is going to like our paper – we sent it around the great and the good of the inequality world and really got a ‘marmite effect’ –people love or hate it (Andy’s New Bottom Billion paper on poverty in middle income countries got much the same initial response). Who likes it? Without naming names, here are the main love/hate responses – stylized – for a few salient groupings (those who commented on the paper shouldn’t get too hung up on this table).

Love it

Hate it

Inequality gurus and wonks

Those who appreciate the point about communicability and policymaker accountability

Those who feel the mathematical properties of an inequality measure are more important

Other wonks

Those who feel tackling inequality (or at least, vertical inequality) is central to development

Those who prioritise other aspects, e.g. the 0.7 target for aid

Economists

More ‘political’ economists, philosophers

More technical economists

We think there’s an important debate to be had on measuring inequality, especially if the post-2015 discussions take it into central account. So let’s start with a vote (see right), preferably after you’ve taken a look at our paper.

Andy Sumner is co-director of the newly established, International Development Institute at King’s College London, that is seeking to study development from a different angle. Alex Cobham is a research fellow at the Center for Global Development in Europe and a member of the advisory group of the UN consultation on inequalities in post-2015.

March 18, 2013

How to build local government accountability in South Africa? A conversation with partners

This is what a good day visiting an Oxfam programme looks like. I skim the interwebs (and this blog) to put together some thoughts on a given issue from our experience or what others are writing (‘the literature’). Then sit down with local Oxfamistas and partner organizations (who are usually closer to the grassroots than we are) to compare these bullet points with their reality. Last Friday it was ‘how can NGOs build the accountability of local government.’ My ten minutes covered:

This is what a good day visiting an Oxfam programme looks like. I skim the interwebs (and this blog) to put together some thoughts on a given issue from our experience or what others are writing (‘the literature’). Then sit down with local Oxfamistas and partner organizations (who are usually closer to the grassroots than we are) to compare these bullet points with their reality. Last Friday it was ‘how can NGOs build the accountability of local government.’ My ten minutes covered:

Supply (training officials) v demand (strengthening civil society) v building collective trust in fragmented societies

The importance of identifying and working with insider champions within the state – no good shouting at the gates if no-one inside is willing to listen and work with you

It can be risky – make sure staff and partners have support if the state officials lash out

Often need to pursue deeper culture change on officials’ attitudes to excluded groups

Need to choose between focussing on the broader ‘enabling environment’ of access to information, respect for the law, exposing corruption etc or more specific campaigns for housing, electricity, schools etc

Some interesting examples of text-based complaints mechanisms (India) and name-and-shame league tables

(Vietnam)

(Vietnam)A lot of this resonated with the South African experience. Some thought-provoking additional points included:

The SA implementation gap between ‘first world norms and standards’ and an underfunded and often chaotic/corrupt corrupt administrative reality is so wide it may even be counterproductive (no point in acting because however hard you try, you can never comply). Local government is hobbled by lack of cash, capacity, and officials’ inability to understand ‘perfect’ guidelines and standards drawn up by distant consultants.

The political incentives are all wrong. Patronage is as big a problem as corruption – party hacks get parachuted into senior administrative jobs, lacking the capacity or interest to perform them properly. ‘People in positions feel very powerful’, and their power springs from playing the political game within the ANC, fighting the internal turf wars rather than doing right by the people.

Despite this, there are officials and politicians willing to do the right thing, either because they are politically progressive and committed (this is the ANC, after all), or because more self-interested political incentives are temporarily/accidentally aligned with those of the popular movement. A huge element of civil society advocacy is built around identifying and building relationships with such individuals. Finding backing for local insider champions (eg from higher tiers of government and politics, or international bodies) can make a real difference in strengthening the hand of the good guys within the state.

But that can be very exhausting: ‘you look at the giant that is Government and it’s so difficult to navigate. You never quite know where to push, (and nor do the officials!). You invest hugely in building intimate relationships only to find they’ve moved department and you have to start all over again.’

Civil society (including Oxfam) don’t always do themselves any favours: ‘CSOs go with the attitude ‘you’re paid to do this, and you drive a 4×4. Why should I congratulate you when you actually do your job?’ So they get nowhere.’

More optimistic times

Options include:

Judicial activism, but there is little cash to support it, and it is very slow.

Changing norms: At present ‘there’s no corruption, no shame’ among officials. CSOs could go for broad public awareness raising and pressure along the lines of ipaidabribe.com, ‘they work for us’ websites on the performance of politicians or civil servants, ‘slowest response of the year’ competitions etc. But those in the room thought this would be very risky indeed, given the ANC’s hostility to public criticism.

Broaden alliances beyond networks of CSOs (which seems to be the default model), not least because civil society currently has access to political leaders (they were often in the anti-apartheid movement together), but little real traction. Partners thought the private sector offered more promise than faith-based organizations or traditional leaders.

We finished by asking everyone to suggest something new to try. Here’s what they came up with:

Invest much more in ‘positive reinforcement’. Find champions, publicly support them. Build relationships.

Do more long term awareness-raising with communities about what the government ought to be doing for them

Think about a South African ipaidabribe.com

Budget tracking/ ‘follow the money’ watchdogs to ensure that money allocated arrives intact and is then actually spent (a scandalous amount of health and education money has to be returned to central government because local officials fail to spend it on time).

But in the end, several partners thought that only an increase in political competition, with the ANC facing a genuine chance of being voted out of municipal governments, would shift the behaviours of most officials. Given the state of the opposition, that doesn’t look likely, but I’ll speculate on that in a future post.

And if you happen to be in Cape Town today, why not come along to the Sustainability Institute at 12 to discuss ‘Creating a Just Food System through Active Citizenship‘? Some good panelists (and me).

March 15, 2013

When it comes to closing down Google Reader, I’m with Hitler

I start most days catching up on the news via Google Reader. Anything new from all my favourite wonk gurus, handily collected together, to be read for subsequent blogging and tweeting. So of course they’re shutting it down. Grrrrrrr. Let me know when the campaign begins [h/t Chris Blattman]

March 14, 2013

Doing a big Alaska: the case for a global social protection fund

Olivier de Schutter, the UN’s special rapporteur on the right to food, is consistently interesting and provocative. This call to action is currently circulating on the interwebs (although the paper it’s based on came out last October):

call to action is currently circulating on the interwebs (although the paper it’s based on came out last October):

‘If protecting human rights could be translated into a single political action, the creation of comprehensive social protection schemes would be it.

Health care, unemployment insurance, food aid, disability benefits: these are some of the services that characterise durable human development and distinguish today’s most prosperous societies from those living one hundred, or even fifty, years ago.

Yet many of the world’s poorer states have not adopted anything like a comprehensive social safety net. Some 80% of the world’s poorest people remain without any access to basic security against poverty and the risks associated with illness, old age, or unemployment. In low-income countries a small increase in food prices can leave the poorest no longer able to put food on the table. Worse, they cannot turn to the State for help. The injustice is particularly acute if considered that, for as little as 2 per cent of global GDP, basic social protection could be provided to all of the world’s poor.

So why are we not achieving faster progress in the establishment of social protection schemes in developing countries? Some countries have failed to invest in social protection because the development models supported by major international institutions have pushed States to lower government spending and reduce the size of the State. Elsewhere it is limited infrastructure and a low ability of local populations to pay into a contributory system that holds States back.

But for others, particularly least developed countries, the main disincentive is the risk of economic or environmental shocks. In small developing countries a large portion of the population is often susceptible to the same risks of natural disasters, epidemic diseases or extreme food price increases, leading to simultaneous surges in demand for social protection and decreases in State export and taxation revenues. States have a legitimate concern that they will not be able to pay out – or will be bankrupted in the process of doing so.

But social protection is too crucial a building block of development to be allowed to fall asunder on this uncertainty, and the multiplier effects of a decent social safety net – for human development and sustained economic growth – are too great to miss out on.

But social protection is too crucial a building block of development to be allowed to fall asunder on this uncertainty, and the multiplier effects of a decent social safety net – for human development and sustained economic growth – are too great to miss out on.

Global solidarity is needed to break the deadlock. Wealthier nations must assist States for whom the costs are too big to absorb alone. The Global Fund for Social Protection that I have proposed, alongside Magdalena Sepúlveda, UN Special Rapporteur for Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, would allow poorer States to draw on international funding to meet the basic costs of putting social protection in place, while the Fund could also be called upon to underwrite these schemes against the risks of excess demand triggered by major shocks.

States can no longer claim to believe in human rights protection while failing to invest in social protection, for the two are intimately linked. There are many ways and means of funding a decent social safety net – now we need the political will.’

De Schutter’s missive dropped into my inbox just as I was having similar conversations here in South Africa about the case for a universal Basic Income Grant. Could it be funded from mining royalties, people were wondering? I told them to look up the CGD’s ‘oil to cash’ proposal for just that. Call it ‘doing an Alaska’. The CGD/South African proposals are national, de Schutter’s global. One obvious problem with the global proposal is the lack of discussion on how it could be funded. ‘As little as 2% of global GDP’ works out at $1.4 trillion – 10 times the global aid budget. You would probably need to put together all the proposals for international taxation (on financial transactions, arms trade, airlines etc) to pull it off, and what kind of political coalition is going to do that? Which probably explains the lazy reference to ‘political will’ at the end of de Schutter’s email. Politically, doing an Alaska at national level looks a lot more realistic.

And here’s CGD’s Todd Moss trying to do a Hans Rosling in a 4m video explaining oil to cash.

March 13, 2013

How can South Africa promote citizenship and accountability? A conversation with some state planners

How can states best promote active citizenship, in particular to improve the quality and accountability of state services such as education? This was the topic of a great two hour brainstorm with half a dozen very bright sparks from the secretariat of South Africa’s National Planning Commission yesterday. The NPC, chaired by Trevor Manuel (who gave us a great plug for the South African edition of From Poverty to Power) recently brought out the National Development Plan 2030 (right), and the secretariat is involved with trying to turn it into reality.

such as education? This was the topic of a great two hour brainstorm with half a dozen very bright sparks from the secretariat of South Africa’s National Planning Commission yesterday. The NPC, chaired by Trevor Manuel (who gave us a great plug for the South African edition of From Poverty to Power) recently brought out the National Development Plan 2030 (right), and the secretariat is involved with trying to turn it into reality.

I kicked off with some thoughts which should be familiar to regular readers of this blog: the importance of implementation gaps, the shift in working on accountability from supply side (seminars for state officials) to demand side (promote citizen watchdogs to hold the state to account) and the challenge from the ODI-led Africa Power and Politics Programme that accountability work needs to break free of such supply/demand thinking and pursue ‘collective problem-solving in fragmented societies hampered by low levels of trust’, which seems a pretty good description of South Africa, according to the NPC. I gave the example of the Tajikistan Water Supply and Sanitation Network as an example of how this can be done through ‘convening and brokering’.

Once I shut up, it got more interesting (funny how often that happens). Some of the most interesting questions (and responses from me and others)

Lots of ‘convening and brokering’ is little more than talking shops – when does it lead to concrete results?

Depends who’s in the room – do they share a common interest in finding solutions or are they there to fight turf wars, defend ideological positions etc?

Can you build forward momentum by identifying some quick wins that make people realize what is possible?

Individuals matter – is there a charismatic leader (as in Tajikistan), who can bind the forum together and keep it moving forward?

How to move from dependency to agency? At least some people see a real problem of acquired dependency. Poor people in South Africa have become dependent on free housing, state welfare etc, and have lost their sense of agency. Instead they oscillate between passivity and protest. The government conducts large scale consultation set pieces to try and encourage participation, but what is lacking is the day to day accountability the allows citizens to get action when public services fail.

How to move from dependency to agency? At least some people see a real problem of acquired dependency. Poor people in South Africa have become dependent on free housing, state welfare etc, and have lost their sense of agency. Instead they oscillate between passivity and protest. The government conducts large scale consultation set pieces to try and encourage participation, but what is lacking is the day to day accountability the allows citizens to get action when public services fail.

The civil servants in the room happily disagreed with each other – fascinating to see an internal debate like this – Oxfam colleagues also contributed, so what follows draws on the points raised by people from both organisations. Some saw this as a supply side problem: the lack of public sanction when teachers don’t show up; officials are corrupt etc undermines citizen action; the teachers’ union resist reforms; moreover, ‘politicians only listen when something burns’, turning violent protest into a sensible change strategy.

Others focussed on the demand side, pointing out the problem of time poverty – women in particular just don’t have time to take part in exhausting exercises in citizenship on top of all their other tasks. One of the effects of the fall of apartheid has been an exodus of aspiring socially-motivated black and coloured people both from the teaching profession, and from poor communities, aggravating the problem of sink schools that the middle class, whether black or white, can ignore (especially if they go private). Others questioned this and pointed out that there is actually a lot of protest on the state of public services, and plenty of accountability structures such as school governing bodies, although coverage is patchy.

Which led us to compare the lack of progress in improving the quality of education with the great strides made on tackling HIV and AIDS. Why have the social movements on HIV had so much more impact than in other areas such as education or landlessness?

Here people pointed to the importance of starting with long term awareness-raising, designed both to inform and empower, but also to shift social norms, in this case from seeing HIV as an individual shame to a collective responsibility. This kind of ‘conscientization’, in the language of Paulo Freire, seems ill-suited to state action, so who might be able to do it in the case of education, for example shifting attitudes to seeing poor school grades as a collective, as well as individual, challenge? Social movements? Faith organizations?

empower, but also to shift social norms, in this case from seeing HIV as an individual shame to a collective responsibility. This kind of ‘conscientization’, in the language of Paulo Freire, seems ill-suited to state action, so who might be able to do it in the case of education, for example shifting attitudes to seeing poor school grades as a collective, as well as individual, challenge? Social movements? Faith organizations?

HIV was a cross-class, cross-race issue, touching everyone in South Africa, so the movement found it easier to overcome social divisions. By contrast, poor education is tied closely to class and race, so coalitions are harder to build. And of course HIV was also, literally, a life and death issue – motivation was not a problem. In contrast the ‘slow death’ of bad schooling doesn’t galvanize the citizenry to the same extent. How to change that?

Some final thoughts from me:

- What about trying to shorten the accountability chain in education to make it possible for citizens to get quick action rather than become bogged down in interminable bureaucratic process? How about an education ombudsman with power to investigate complaints and impose sanctions?

- One of the weaknesses of the National Development Plan is its approach to gender. The half a page on ‘Women and the Plan’ in the NDP Overview fails to mention two major obstacles to citizenship: women’s time poverty and the lack of support for their role in the care economy; and the need to change the role of men. I’m pretty sure that on average, women are more concerned about the state of education, but as free time remains a male concept, they will struggle to do much about it.

Great discussion. This is what makes trips such fun.

March 12, 2013

What’s the link between land grabs, trade rules and climate change? Good new briefing from Sophia Murphy

You can rely on Sophia Murphy for crisp, credible analyses of agricultural trade and food issues. Her latest paper, Land Grabs and Fragile Food Systems, is up to her usual standard. She locates the current row over land grabs in some broader debates that have rather fallen off the agenda, namely globalization and trade rules. Made me come over all nostalgic for the WTO-bashing of yesteryear.

Grabs and Fragile Food Systems, is up to her usual standard. She locates the current row over land grabs in some broader debates that have rather fallen off the agenda, namely globalization and trade rules. Made me come over all nostalgic for the WTO-bashing of yesteryear.

Sophia argues that the globalization and the free trade agreements of the last 20 years have combined with fears over climate change to create the conditions for the current wave of land grabs. But the immediate trigger was the 2008 food price spike, which eroded the confidence of food-importing countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait that they could rely on the trading system to feed their people (so many of them started grabbing land instead).

The problem with the WTO is that its insistence on removing import tariffs (which we campaigned on when prices were low) was not matched by any effort to discipline export controls, making it completely irrelevant when prices rose and exporting countries slapped on export taxes to try and keep the food at home, thereby compounding the price spike. Sophia also takes a swing at the WTO’s inability/unwillingness to do anything about corporate concentration in the food sector. When the price spike hit ‘the four companies that between them control an estimated 75 percent or more of the international grain trade saw their profits soar.’

Failures in other areas have aggravated the problem. Food reserves have been run down, biofuels have added a new degree of uncertainty by tying food prices to those of oil and gas (when fossil fuel prices rise, more land gets turned over to biofuels, so less food is produced, so food prices rise). Climate change, both current and rapidly approaching, has only added to that sense of vulnerability on food security.

How to reduce the pressures that are driving the wave of land grabs? The report has a rather convincing policy shopping list arising from this analysis:

How to reduce the pressures that are driving the wave of land grabs? The report has a rather convincing policy shopping list arising from this analysis:

Reformed trade rules that ensure export measures are subject to transparency and predictability requirements and that allow all countries policy space for food security policies. She also proposes ways to ease food price spikes by reducing biofuel production during price surges

Publicly-managed grain reserves to dampen the effects of supply shocks

Readily accessible funding for the poorest food importers, which would be triggered automatically when prices increase sharply in international markets

The development of strong national and international laws to govern investment in land, respecting the principles and guidelines set out in the Voluntary Guidelines on Land Tenure. Tanzania’s recently announced limits on how much land foreign and domestic investors can lease is a hopeful example of a national government taking the initiative to get serious about regulation.

At 12 pages, a very useful addition to the land grabs literature. And in case you missed it here’s what the fuss is about.

March 11, 2013

The state of Africa – report from a 23 country road trip (and I’m in South Africa for a couple of weeks)

I’m in South Africa this week, speaking at various events, including a panel on the developmental state and inequality at Wits in Johannesburg (Tuesday 12th), a book launch in Durban on Thursday 14th, a panel on active citizenship and food justice at the Sustainability Institute in Cape Town on Monday 18th and a lecture on ‘which matters more, poverty or inequality’ at the University of the Western Cape on Wednesday 20th. In between, I’m definitely open to offers of beers, coffees etc in Joburg, Durban and Cape Town – often hard to fill the evenings on these trips, although I do have a box set of series 4 of The Wire…….

As I queued to get through immigration yesterday, I read the Economist’s recent special report on Africa by Oliver August. It’s a really nice piece of econo-wonk travel writing, travelling by land across 23 countries (see map) and mixing impressions with analysis. It’s very much an outsider looking in, but that can be interesting too.

It gets a bit close to a Panglossian ‘gee, look at the GDP, isn’t everything great’ tone at times, but overall, offers a readable, geographically-based commentary on some of the big issues – war and conflict (Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Sierra Leone); corruption and good governance (Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria); poverty and civil society activism (Niger, Algeria, Libya, Egypt and Sudan); state v market(Ethiopia and Kenya); managing mineral wealth (Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana) and a separate section on South Africa. Some random snippets to give you a taste:

It gets a bit close to a Panglossian ‘gee, look at the GDP, isn’t everything great’ tone at times, but overall, offers a readable, geographically-based commentary on some of the big issues – war and conflict (Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Sierra Leone); corruption and good governance (Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria); poverty and civil society activism (Niger, Algeria, Libya, Egypt and Sudan); state v market(Ethiopia and Kenya); managing mineral wealth (Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana) and a separate section on South Africa. Some random snippets to give you a taste:

‘At the end of the cold war only three African countries (out of 53 at the time) had democracies; since then the number has risen to 25, of varying shades, and many more countries hold imperfect but worthwhile elections (22 in 2012 alone). Only four out of now 55 countries—Eritrea, Swaziland, Libya and Somalia—lack a multi-party constitution, and the last two will get one soon.’

‘The journey covered some 15,800 miles (25,400km) on rivers, railways and roads, almost all of them paved and open for business. Not once was your correspondent asked for a bribe along the way, though a few drivers may have given small gratuities to policemen. The trip took 112 days, and on all but nine of them e-mail by smartphone was available.’

In Nigeria, ‘The transformation of Lagos is worth trumpeting. Its economy is now bigger than the whole of Kenya’s. Tax revenue has increased from $4m to $97m a month in little more than a decade. Tax rates have stayed the same but the amounts being collected have risen dramatically thanks to the deployment of private tax “farmers” who get a commission.‘

‘Climate change is a further worry. No inhabited continent will be more affected by it than Africa. Deadly droughts, flash floods and falling water tables are recurring themes in conversations across the continent. South Africans are especially worried. “In 20 years this will all be desert,” says the owner of a vineyard near the Cape, standing among verdant vines.’

And his conclusion?

‘Africans rightly worry about unemployment, inequality and a host of other problems. But over the past decade winners have outnumbered losers, and the view from the road suggests they will go on doing so. Your correspondent reaches Cape Town in a hired car on a rainy afternoon, finding the waterfront alive with once-rare tourists from other African countries. “Soon our home will look like this,” says an Angolan father of three, pointing out a cluster of high-rise buildings to his teenage children. “I brought them here to see their future.”’

So, who’s on for a beer then?

March 8, 2013

Are global gender norms shifting? Fascinating new research from World Bank

I’ve been thinking a bit about norms recently – how do the unwritten rules that guide so much of our behaviour and understanding of what is acceptable/right/normal etc evolve over time? Because they undoubtedly do – look at attitudes to slavery, women’s votes, racial equality or more recently child rights.

acceptable/right/normal etc evolve over time? Because they undoubtedly do – look at attitudes to slavery, women’s votes, racial equality or more recently child rights.

So in advance of International Women’s Day, I ploughed my way through a really important new World Bank study, On Norms and Agency: Conversations about Gender Equality with Women and Men in 20 Countries. Like the Bank’s path-breaking Voices of the Poor or the more recent Time to Listen, it’s an attempt to take the global temperature on a big topic through a process of rigorous and deep listening involving 4000 women and men around the developing world.

Such studies are lengthy, complex and expensive, but are incredibly revealing and useful, especially as they start to accumulate. We’re trying a mini version with the Life in a time of Food Price Volatility listening project – first year results out soon.

The report is 150 pages and pretty heavy going – subtle, nuanced and complex, and very hard to extract easy headlines. A close reading will yield much more than a skim, but for the time-poor blog reader, here are some of the findings that jumped out at me.

Bending not breaking: norms are evolving, but through guerrilla warfare more than open confrontation: ‘gender norms [are] changing, albeit slowly and incrementally, with new economic opportunity, markets, and urbanization….. Economic roles for women often creep into their domestic role and, in some places, younger men even take on some narrow domestic responsibilities. What is striking is the glacial pace of this change relative to the pace of change in contextual factors. Gender norms are being contested, bent, and relaxed, but not necessarily broken fully and changed. Younger people may delay compliance to a later point in time, but the norms and the expectations around them do not change.’

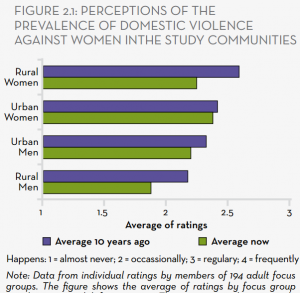

The impact of urbanization: Across the board, women are making more progress in urban than rural areas. Attitudes to equality are more favourable among both sexes; young women are more able to express dissatisfaction with marriage practices; and when asked for who is climbing the ladder of empowerment (see chart), in a large number of urban areas women are moving up as men fall (largely due to economic pressures). In contrast, this quote from an interviewee in rural South Africa captures the stasis in the countryside: the new gender laws “have changed nothing here. We do not have any job opportunities, our husbands assault us, and most of the time the tribal court favors the man. So really nothing has changed. These laws apply only to urban areas.”

The impact of urbanization: Across the board, women are making more progress in urban than rural areas. Attitudes to equality are more favourable among both sexes; young women are more able to express dissatisfaction with marriage practices; and when asked for who is climbing the ladder of empowerment (see chart), in a large number of urban areas women are moving up as men fall (largely due to economic pressures). In contrast, this quote from an interviewee in rural South Africa captures the stasis in the countryside: the new gender laws “have changed nothing here. We do not have any job opportunities, our husbands assault us, and most of the time the tribal court favors the man. So really nothing has changed. These laws apply only to urban areas.”

Education is a major driver of shifting norms: Both parents’ and children’s attitudes to education seem to have gone through a major shift. Mothers, but fathers too, want their girls to be educated, and girls are now often keener on getting an education than boys (see chart). The old stereotype of ‘what’s the point of educating girls, they’ll just get married’ seems to be receding fast. Feels like in future many more countries could be following the UK in heading for a male education crisis (low expectations and performance).

Mothers, but fathers too, want their girls to be educated, and girls are now often keener on getting an education than boys (see chart). The old stereotype of ‘what’s the point of educating girls, they’ll just get married’ seems to be receding fast. Feels like in future many more countries could be following the UK in heading for a male education crisis (low expectations and performance).

Women’s time poverty: hardly a new finding, but striking nonetheless. The very notion of ‘free time’ seems to be confined to men. ‘Unlike men, women use their free or spare time to work; they simply shift activities. Women are the losers in the time distribution game.’

Could male roles be about to shift? Male roles have changed far less than female, but the authors find some grounds for optimism in ‘glimpses of ground-breaking changes in household cooperation, open dialogue, and even power sharing.’ However ‘the task of initiating more open dialogue is placed on men’ and there are hints of desperation in citing Poland and Serbia to make their case. One of the more interesting findings was ‘the polarizing dynamics of economic stress on men’s and women’s agency’: economic crisis drives women into the public arena and relaxes gender norms, Rosie the Riveter style. But men’s identity is so wholly bound up with being the breadwinner, that economic crisis triggers emotional turmoil. The result unfortunately is at least as likely to be destructive (drinking, abandonment, violence) as ‘hey, let me do the cooking for once’. Which reinforces the growing focus within the gender rights movement on the construction of masculinity.

Violence Against Women falling but slowly: (see chart)

What does all this mean for women’s ability to make choices? The report detects ‘a window to aspire’ in which ‘women have gained some autonomy to decide about their education, jobs, marriage (who and when), and reproduction, although they still are permanently challenged not to neglect their domestic duties. Men in the study are showing more willingness to consider sharing power (if not actually share it) and to release some control over household decisions to women. Shared decision-making means men have to bend constraining norms, but it introduces a better decision-making process into their households. And as these men and women change, they transform the traditional playing field in their communities. In the domestic sphere, the women are stealthily altering traditional definitions of duties and responsibilities associated with their expected roles, which may induce change in the norms or make them more flexible.’

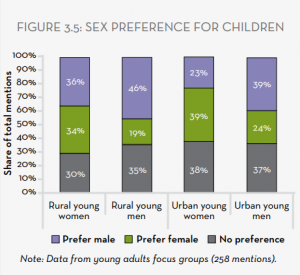

Just how deep these changes go is reflected in adults’ sex preferences for children (see chart) – a remarkable degree of equality in whether would-be parents want daughters or sons. That feels hugely significant.

A universal story, with no magic bullets: The report stresses ‘the universality and resilience of the norms that underpin gender roles’ across the 97 research sites. To their credit, the authors acknowledge that they failed to find equally universal solutions and interventions. But education, a focus on domestic violence, moral support for women, and well publicized and enforced legislation are held up as hopeful ways forward.

A universal story, with no magic bullets: The report stresses ‘the universality and resilience of the norms that underpin gender roles’ across the 97 research sites. To their credit, the authors acknowledge that they failed to find equally universal solutions and interventions. But education, a focus on domestic violence, moral support for women, and well publicized and enforced legislation are held up as hopeful ways forward.

One nagging doubt – in focussing so much on people’s aspirations are we mistaking dreams for reality? Would we have got many of the same results if we had done this report a generation ago? The authors think not, but I’m not sure how certain they can be. But all in all, a fascinating, and cautiously encouraging survey.

March 7, 2013

What if we allocated aid $ based on how much damage something does, and whether we know how to fix it?

I usually criticize development wonks who come up with yet another ‘if I ruled the world’ plan for reforming everything without thinking through the issues of politics, power and incentives that will determine which (if any) of their grand schemes gets adopted. But it’s been a hard week, and today I’m taking time out from the grind of political realism to rethink aid policy.

Call it a thought experiment. Suppose we started with a blank sheet of paper, and decided which issues to spend aid money on based on two criteria – a) how much death and destruction does a given issue cause in developing countries, and b) do the rich countries actually know how to reduce the damage? That second bit is important – remember Charles Kenny’s book ‘Getting Better‘, which argues powerfully that since we understand how to improve health and education much better than how to generate jobs and growth, aid should concentrate on the former.

If you followed this exercise, I think you would end up with a radically different aid agenda, with a whole bunch of Cinderella issues coming in from the cold (I’m also taking a break from not mixing metaphors).

Here’s the global death toll (from the new edition of FP2P, c/o indefatigable number crunching from Richard King).

These are global figures, and I don’t have a breakdown by developed/developing. That would be important on obesity, but on other issues, the majority of impact is clearly in poor countries – alcohol, tobacco and road traffic for example. And they are precisely the areas where the rich countries have lots of experience in reducing the damage. It’s certainly a lot more straightforward than inventing/discovering new vaccines. When researchers put signs in Kenyan minibuses (matatus) urging passengers to criticize reckless driving, injuries and deaths fell by a half (for paper see here).

So how come such subjects are so seldom seen as development issues? Where’s the campaign on booze and fag dumping by large corporations in developing countries? Or international seat belt conventions, backed by technical assistance to help governments ratify and implement? Your thoughts please. Presumably some kind of campaigns exist on all these issues – please send links – but they could be a lot more prominent.

And for the truly wonky/medically inclined here’s a more sophisticated version from the Guardian – Disability Adjusted Life Years, which Claire Melamed and John Appleby reckon could be usefully mainstreamed in development. It shows which causes of global death and disability are up/down from 1990-2010. And if you don’t know what Ischemic or COPD mean, look them up.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers