Duncan Green's Blog, page 211

July 16, 2013

Has the Arab Spring Failed? Not yet, reckons the Economist – Highlights from its excellent Special Report

By blog-reader standards, the Economist’s Special Reports can be pretty long (15 pages in this case), but they are sharply written and stuffed full with great stats. As long as they steer clear of economic policy, they are also not as ideology-laden as some of the magazine’s other content. So if you can spare half an hour, read this week’s report on the Arab Spring by its Middle East correspondent, Max Rodenbeck. If not, here are a few highlights:

great stats. As long as they steer clear of economic policy, they are also not as ideology-laden as some of the magazine’s other content. So if you can spare half an hour, read this week’s report on the Arab Spring by its Middle East correspondent, Max Rodenbeck. If not, here are a few highlights:

“Before it began to stir in December 2010, the world’s 350m Arabs had seemed oddly immune to the democracy bug that had infected most corners of the globe. Whether republics or monarchies, nearly all of the world’s 19 predominantly Arabic-speaking states had solidified into similar political forms, their varied constitutional veneers flimsy disguises for strongman rule. The people, including legions of often jobless youths, had no say in how things were run.

In breathtakingly short order the decades-old dictatorships of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen collapsed. As popular pressure mounted, other Arab governments announced political reforms, more public spending and other concessions to appease their restless people. A region-wide burst of youthful energy that reminded Westerners of their own liberating social upheaval of the 1960s suggested a new sense of empowerment. The “Arab exception”—the apparent inability of these neo-patriarchal states to move towards political norms shared by most of the world—seemed to have been overcome.

Those heady, hopeful days have long passed…. the scorecard for the Arab spring so far looks overwhelmingly negative. But such an assessment is premature. Rather than having reached a sorry end-point, the wave of change may have only just begun. Judging by experience elsewhere, such transitions take not months but years, even decades.

Further unrest and almost certainly further bloodshed lie in store. But this may well be unavoidable in a part of the world where bewildering social change, including extremely rapid population growth and urbanisation, for so long went woefully unmatched by any evolution in politics. Debate on such crucial issues as the relationship between state and religion, central authority and local demands, and individual and collective rights could not be indefinitely stifled. Something had to give.”

“In terms of casualties suffered, the Arab-Israeli conflict is far from the worst trauma that Arabs have had to endure. Civil wars in Sudan, Algeria, Lebanon and Iraq have each claimed many more lives. Syria, with grim certainty, soon will. Egypt lost more soldiers when it intervened in Yemen in the early 1960s, in support of republicans against Saudi-backed monarchists, than in the sands of Sinai during the six-day war against Israel in 1967. The Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s left vast numbers of people dead, perhaps half a million, possibly over a million; no one knows for sure.”

“It is mainstream Islamists rather than radicals who have won the most votes: men with trimmed beards and ties; women wearing headscarves rather than burqas. These newly empowered movements have generally shied away from imposing harsher religious rules. They sense that apart from a committed minority, voters care more about cleaning up government than bringing society closer to God.”

“Life expectancy in the region has risen by 25 years since 1960, faster than in most parts of the world. Literacy in Saudi Arabia has shot up from 10% in 1960 to 87%, and 99% for youths of school-leaving age. Quantity, however, has not been matched by quality. Saudi Arabia spends a higher proportion of its GDP on schooling than most rich nations, yet in a recent set of standardised global maths tests, under half of Saudi 13-year-olds reached the lowest benchmark, compared with 99% in South Korea and 88% in England. Barely 1% of the Saudi children gained an “advanced” level, against 47% of South Korean and 8% of English ones.

“Life expectancy in the region has risen by 25 years since 1960, faster than in most parts of the world. Literacy in Saudi Arabia has shot up from 10% in 1960 to 87%, and 99% for youths of school-leaving age. Quantity, however, has not been matched by quality. Saudi Arabia spends a higher proportion of its GDP on schooling than most rich nations, yet in a recent set of standardised global maths tests, under half of Saudi 13-year-olds reached the lowest benchmark, compared with 99% in South Korea and 88% in England. Barely 1% of the Saudi children gained an “advanced” level, against 47% of South Korean and 8% of English ones.

These surveys showed up another anomaly. Almost everywhere else boys and girls did more or less equally well, but in Arab countries girls outperformed their pampered male siblings by huge margins, and most Arab countries have more female than male university students. Yet Arab countries also have extremely low female labour-force participation rates. For example, barely 15% of Algerian women of all ages have paid jobs, compared with 58% in America. And the ratio of women to men in low-quality jobs in Arab countries remains the highest in the world, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO).”

“What drives [young] people to extremes is not simply the difficulty of scraping a living and being harassed by the law but the seemingly inescapable bind they find themselves in. Arab social conventions remain rigid. Marriage is a prerequisite for sex, and having a house or flat is a prerequisite for marriage. Bad state planning, poor access to finance, tangled property laws and rapid population growth all ensure that in most Arab countries demand for affordable housing far outstrips supply.

The average age of marriage in Arab countries has risen inexorably in recent decades, suggesting that youths are being forced to postpone setting up home. “I think one of the main indicators of what was behind the revolutions is the question, how long would you have to work to get a house compared with your parents?” says Kito de Boer, who runs the Dubai office of McKinsey.”

And here’s the author discussing the report with his boss (10m)

July 15, 2013

Some Monday Morning Inspiration: Malala Yousafzai at the UN

Moving and astonishingly confident speech at the UN last week by Malala Yousafzai on the UN-declared ‘Malala Day‘ (12 July – her birthday). Think we’ll be hearing a lot more from her – a future president?

Here’s the film my sister-in-law Mary Matheson made for Plan International to celebrate Malala’s birthday (which got shown at the UN event)

And ‘I am Malala’, a rather wonderful rap by young women musicians. Background to the video here.

And here’s the way Malala, who now lives in the UK, is influencing girls in Pakistan

July 12, 2013

10 Killer Facts on Democracy and Elections

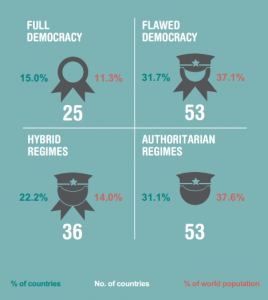

Ok this is a bit weird, but I want to turn an infographic into a blogpost. The ODI, which just seems to get better and better, has just put out a 10 killer facts on elections and democracy infographic by Alina Rocha Menocal, and it’s great. Here’s a summary:

Most countries today are formal democracies. An astonishing political transformation has taken place around the world over the past three

decades. By the end of 2011, the only countries considered autocracies were: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Belarus, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Laos, North Korea, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Swaziland, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Vietnam, and Uzbekistan.

decades. By the end of 2011, the only countries considered autocracies were: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Belarus, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Laos, North Korea, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Swaziland, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Vietnam, and Uzbekistan.Over one in three live in authoritarian systems (but over half of them are in China).

Elections have become almost universal: elections have been held in all but five countries with populations >500k from 2000-2012: China, Eritrea, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates.

Most leaders in Africa are replaced by ballots, not bullets: While in the 1960s and 1970s approximately 75% of African leaders were ousted through violent means (coup d’etats, rebellion), in the period 2000-2005 this number had dropped to 19%.

But elections are not always peaceful: between 1990 and 2007 one in five elections in SubSaharan Africa suffered significant violence and only about 40% were entirely violence-free.

The quality of many of these democracies remains deeply flawed: Only 15% can be described as ‘full democracies’, with 31% counting as ‘authoritarian regimes’. The rest are in-betweeners, either ‘flawed democracies’ or ‘hybrid regimes’.

Alternations of power remain remarkably limited in Sub-Saharan Africa: Since 2000, only fourteen of 51 states have seen power transferred between political parties.

Alternations of power remain remarkably limited in Sub-Saharan Africa: Since 2000, only fourteen of 51 states have seen power transferred between political parties.The wealthiest countries tend to be democracies: outside the petro-states, the top 25 richest countries in the world (as ranked by the World Bank) are also fully established democracies. In fact, a democratic regime has never fallen after a certain income level is reached (US$6,055 per capita) – which was Argentina when it fell to bureaucratic authoritarianism in 1963. But correlation does not (in case you were wondering) mean causation……

The total number of women elected to parliament has almost doubled since 1997 (OK, only to 21%, but still…) As of April 2013, the top 10 countries in descending order in terms of the percentage of women in the lower or single House are: Rwanda, Andorra, Cuba, Sweden, Seychelles, Senegal, Finland, South Africa, Nicaragua, and Iceland.

Expensive elections are not necessarily better: at $6bn, the 2012 US elections cost 20 times more than the UK 2010 ones. The costs of the 2007 elections in Kenya (messy, violent – see pic) were US$13.74 per registered voter (or US$ 29 per cast ballot). The elections in Ghana in 2008, (v civilised by comparison), came to US$0.70.

And for an added bonus, read ‘Hurling elections at Complexity’. Brilliant & sensible piece by the World Bank’s Sina Odugbemi

Stop hurling elections at #complexity. Brilliant & sensible piece by Sina Odugbemi at World Bank http://blogs.worldbank.org/publicsphe...

July 11, 2013

What to read (and watch) on Egypt

I’m turning into a big fan of crowdsourcing. This set of top analyses, infographics and videos was suggested by a mix of Oxfam Egyptologists and a call  for suggestions on twitter. Given how polarized the coup v revolution debate is right now, I won’t attach names to particular pieces, but thanks to all the Oxfamistas, plus Laurence Chandy, Kate Cooper, Julian Doczi, Marta Foresti, Greta Galeazzi and Danny Sriskandarajah.

for suggestions on twitter. Given how polarized the coup v revolution debate is right now, I won’t attach names to particular pieces, but thanks to all the Oxfamistas, plus Laurence Chandy, Kate Cooper, Julian Doczi, Marta Foresti, Greta Galeazzi and Danny Sriskandarajah.

First the reading matter:

‘For the past week I have been trundling between the pro- and anti-Morsi protests. It is like travelling between two planets.’ On sheep and infidels. Remarkable attempt at an even-handed analysis from Sarah Carr.

‘This is one expression of an unfinished revolution – important to recall that other revolutions were also extended over long periods of time (i.e the French Revolution)’ IDS boss Lawrence Haddad interviews Mariz Tadros, their top Egypt watcher.

‘The Egyptian army has not returned to politics for the simple reason that it has never left.’ Egypt : Coup D’état, Act II by the brilliant Tariq Ramadan.

‘When Morsy ascended to power on June 30, 2012, he had choices — and he chose factional gain, zero-sum politics, and populist demagoguery.’ Michael Wahid Hanna on how we got here.

‘With the new text, what, if anything, do the country’s new authorities appear to have learned from the mistakes of the past? The answer is: not much.’ Zaid Al-Ali on the constitutional declaration, (the declaration’s content summarized here).

‘You cannot ram through a constitution that the majority of relevant political players objected to, and yet express surprise that people do not recognize the legitimacy of the current political order, and are demanding the president’s resignation.’ Hesham Sallam.

‘Ultimately, however, the Salafis may come out as a long-term winner, using the blow to the Brotherhood to move to the fore in among the Islamist segment of the population.’ ‘After the Egyptian Coup’, Q&A with Nathan Brown, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Middle East scholar. Brown also has a guide to‘what to watch for in the days ahead’.

Briefings from the always reliable Chatham House

Next the Infographic, a really handy guide to the range of actors involved, and (roughly) whose side (or quadrant) they’re on.

Finally, the videos

Egypt Explained (by a hilarious hyped up American ubergeek)

But he’s totally eclipsed by this amazingly erudite 12 year old Egyptian kid, apparently interviewed at random on the street – it’s a few months old now, but there’s definitely hope for the country as long as people like him are around.

Feel free to add further suggestions, especially future-facing analysis of the longer term drivers of change, power analysis etc

Update: there’s also a fabulous photo gallery collected by the New Yorker

July 10, 2013

Could crowdsourcing fund activists as well as goats and hairdressers?

I’ve often wondered if Oxfam or other large INGOs could include the option of sponsoring an activist, either as something to accompany the goats, toilets, chickens etc that people now routinely buy each other for Christmas, or instead of sponsoring a child. I had vague ideas about people signing up to sponsor an activist in Egypt or South Africa, and in return getting regular tweets or Facebook updates. Alas, I’ve never managed to persuade our fundraisers to give it a go.

toilets, chickens etc that people now routinely buy each other for Christmas, or instead of sponsoring a child. I had vague ideas about people signing up to sponsor an activist in Egypt or South Africa, and in return getting regular tweets or Facebook updates. Alas, I’ve never managed to persuade our fundraisers to give it a go.

Now it’s come a bit closer to home. My son, who is a community organizer for the wonderful London Citizens, is currently looking to raise funds to work with a bunch of institutions in Peckham, South London. I couldn’t help him much as I’m rubbish at fundraising, (sure I’m a huge disappointment to him) but it did start me wondering whether there is an activist equivalent to the kind of crowdsourcing sites that are all the rage for small businesses (Kiva, Kickstarter etc). So, inspired by the feedback to my Monty Python bleg, I tweeted a request for sites.

What emerged was a (for me) previously invisible ecosystem of crowdfunding options for radicals. Here’s the list of the links people sent it:

edgefund.org.uk ‘Edge Fund is a grant-making body with a difference. We support efforts to achieve social, economic and environmental justice and to end imbalances in wealth and power – and give those we aim to help a say in where the money goes.’ [via @ LABatSMK]

startsomegood.com mainly for US activists seeking funding, but others from Australia and UK [via @ hackofalltrades]

changemakers.com has more of a focus on innovation than activism, and has a global reach [via @ roscaf]

youcaring.com mostly for paying medical expenses in the US [ via @ YALoved]

thesparkproject.com nice example from the Philippines for funding social projects [via @ papalphacharlie]

In Germany activists use adoptrevolution.org to support activists in Syria, as well as the much larger (and global) betterplace.org platform [via @joanabp]

Which one's mine?

It’s still pretty small (do add to the list), but showing signs of growing. And activist crowdfunding is itself a subset of a wider movement of so-called ‘disintermediation’, people sending money directly to where they want it to go, rather than through intermediaries. That has spread not just to business investments but also direct giving to poor people (see my earlier post on GiveDirectly) and some suggestions for similar exercises to Alaska’s scheme of transferring oil royalties direct to citizens’ bank accounts..

Thanks to all those who retweeted, and look forward to getting more links in due course.

July 9, 2013

What is ‘leverage’ (NGO-speak version) and why does it matter?

Last week I attended the twice yearly gathering of Oxfam GB’s big cheeses – the regional directors, Oxford bosses and a smattering of more exotic cheeses from other Oxfam affiliates (Australia and US this time). We started off with a tour of the regions – what’s on their minds? 3 common themes emerged: political upheaval (disenchantment with elected governments, protest, the threat of civil war); religious conflict (fundamentalism) and rising inequality.

cheeses from other Oxfam affiliates (Australia and US this time). We started off with a tour of the regions – what’s on their minds? 3 common themes emerged: political upheaval (disenchantment with elected governments, protest, the threat of civil war); religious conflict (fundamentalism) and rising inequality.

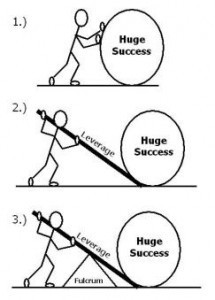

The topic of this meeting was a classic new fuzzword – ‘leverage’. And like all good fuzzwords, it was frustrating and helpful in equal measure. Frustrating in its hard-to-define slipperiness, helpful because it establishes a fuzzy-boundaried arena of conversation that allowed us to have an interesting exchange.

The overriding purpose of leverage is another bit of management jargon: ‘going to scale’. How to influence bigger players to reach many times more people than you would do by acting alone? The ambition is heroic, perhaps crushing on occasion – with your few thousand (or even million) quid, it’s not enough to just help a few hundred people, you have to think how this can transform lives en masse. I suspect it partly stems from frustration born from aiming too low; partly from the push for results.

But it also comes from the excitement of seeing it work on the ground. I’ve talked previously about some of the best examples – convening and brokering in Tajikistan; campaigning to get megabucks out of governments for climate change (Philippines) or healthcare (Zambia); viral marketing to change attitudes on violence against women in South Asia. Social franchising (savings schemes in West Africa); piloting a new educational approach that is picked up by a national government (Vietnam); good old-fashioned research and advocacy on disabled people’s rights in Russia. This is a menu of approaches, more a way of thinking than a single recipe.

Leverage in practice is most developed in our work on influencing the state, whether on politics or expenditure, but some of the greatest enthusiasm actually comes from ‘livelihoods’ work – for example helping small farmers get into value chains for their products, and on decent terms.

One good sign – ‘leverage’ resonates with Oxfam staff on the ground (new fuzzwords usually make them groan). When we asked country programmes if they had some good examples of leverage, we got loads (including some of those I described earlier, and some new ones I will process in due course).

The concept also comes with some interesting tensions/contradictions. The term can easily mean ‘Oxfam doing something really big’, feeding the (alleged) megalomaniac tendencies of fund raisers and bosses alike. That’s not what we’re talking about (at least, not this time). Rather it’s getting to scale by acting as a catalyst, where smaller interventions may lead to bigger results (and conversely, having too big a budget to spend can actually be a problem, driving you towards service delivery rather than leverage). This is a more intelligent version of ‘doing more with less’.

Does leverage make you more or less able to respond to unexpected opportunities? On balance, I’d say the former – if you have lots of prior relationships with different types of individual and organization (a large and varied personal network is pretty essential for anyone doing leverage) – then it’s a lot easier both to find out when something unusual/important is happening, and to respond imaginatively with the right blend of people.

They could easily be working for Oxfam

There are some risks. Existing partners may not like it (as I saw in Honduras). Going to scale without doing it all yourself implies surrendering a degree of control – how do you manage the brand risk if such an exercise goes off the rails and Oxfam gets the blame? Will donors fund something as uncertain and hard to predict? And of course, as with any half-intelligent approach, it is MEL-hell – What do you monitor? How can you plausibly attribute any change to your own actions, when you are just one minor player?

In practice, I think the consequence for the way aid agencies think is to introduce a shift towards automatically asking how any given intervention, partnership etc can have the maximum possible impact. Here’s where it bangs up against the increasing questioning of blueprints, best practice, cookie cutter solutions etc that I have written a lot about (and a concern I share). If every context is different, and every solution needs to be ‘best fit’ rather than ‘best practice’ how can you ‘go to scale’? Maybe that means focussing on building the enabling environment (transparency, accountability etc) rather than specific solutions. Or social franchising that can adapt to local circumstances. Any thoughts?

Oh and I also found out that Hungary has an Ombudsman for Future Generations – I really want that job (or at least the business card).

July 8, 2013

Can impact diaries help us analyse our impact when working in complex environments?

One of the problems about working in a complex system is that not only do you never know what is going to happen, but you aren’t sure what developments, information, feedback etc will turn out (with hindsight) to be important. In these results-obsessed times, what does that mean for monitoring and evaluation?

developments, information, feedback etc will turn out (with hindsight) to be important. In these results-obsessed times, what does that mean for monitoring and evaluation?

One answer is to keep what I call an ‘impact diary’, where you dump any relevant info as it passes across your screen/life, so that you can reconstruct a plausible story of impact at a later date.

What might such a diary (more like a folder) contain?

Business cards (one former head of our Pan Africa programme used number of business cards collected by staff as a performance indicator, increasing the pressure on them to get out and network)

Feedback (emails, press coverage, conversations)

Feelings at the time – apprehensions, enthusiasms

Critical Junctures: big decisions, why, when, what

List of things that people say that need more thought (so they don’t get lost)

I ran this past some of our monitoring and evaluation wallahs. Claire Hutchings added some general guidelines on what to record, focussing on how to make it intelligible to people like her who come in later and have to evaluate a campaign that can often be heavy on jargon and wonky detail:

describe who changed, what changed in their behaviour, relationships, activities or actions, when, and where – explain why the outcome is important. The challenge is to contextualise the outcome so that a reader who does not have country and topical expertise will be able to appreciate why this change in a social actor is significant. How do you know that the outcome was a result— partially or totally, directly or indirectly, intentionally or not – of our activities?

Also important for watershed moments to be recorded, along with some contextual information (what are the key factors, key actors etc.) that will help to explain it in the future.

Our campaigns MELista, Kimberly Bowman, focused on the how, rather than the what. If you set up an elaborate system that requires people to enter loads of data, you can be pretty sure it won’t happen. So the key is to redirect existing flows of information, chatter and analysis into a ‘bucket’ that evaluators or campaigners can analyse later, when things aren’t so frenetic. The simplest is to add a bucket email address to all the existing group emails, and do something similar for twitter and blogs.

Kimberly also suggested some new software (at which point, this post crosses my IT frontier and moves off into the outer darkness):

‘For the World Bank land freeze campaign (Oct-April this year), we used ‘Evernote‘ to collect all of the team’s internal emails. Evernote has a nice webclipping tool, apps for phones, group data-sharing options, tagging, and optical character recognition for searching PDFs and Word docs, so it seemed like an interesting thing to test.’

Any other suggestions, either on the what or the how?

July 5, 2013

The Monty Python guide to aid and development. Part Two – Economics

So another Friday comes round, we all need a break, so following the triumph of last week’s Monty Python guide to the politics of development, let’s move on to economics……

Redistribution is trickier than we thought [via Andrea Franco]

Wellbeing v growth (the Yorkshire version)

Banks and corporate social responsibility

and keep the suggestions coming – there may yet be a third installment

July 4, 2013

Women’s Leadership Groups in Pakistan – some good news and inspiration

I normally try and keep Oxfam trumpet-blowing to a minimum on this blog, but am happy to make an exception for this piece from Jacky Repila  (right) on a new report on our Raising Her Voice programme in Pakistan, a country that ranks 134th out of 135 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index (only Yemen is worse).

(right) on a new report on our Raising Her Voice programme in Pakistan, a country that ranks 134th out of 135 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index (only Yemen is worse).

When Veeru Kohli (left) stood as an independent candidate in Hyderabad’s provincial elections on 11th May, she made history.

Kohli is poor. Making the asset declaration required of candidates, Kohli listed just two beds, five mattresses, cooking pots and a bank account with life savings of 2,800 rupees, wages for labourers in Karachi are around 500 rupees a day.

She’s a member of a minority group – Hindus represent less than 6 per cent of the country’s total population. The vision of tolerance and inclusion of Pakistan’s founding father, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, has sadly been eroded as we can see from the 500 Pakistani Hindus who recently fled to India to escape discrimination.

She’s uneducated and does not boast the political connections or patronage of most politicians. In fact she has ruffled feudal feathers, escaping captivity from her former landlord and fighting in the courts for the release of other bonded labourers.

And then of course, she’s a woman. Only 3 per cent of all candidates contesting the general seats for the National Assembly were women.

And yet…. in spite of the inevitable establishment backlash seeking to devalue her credentials, on 11th May six thousand people voted for her. Although not enough to win the seat, the fact of Kohli’s standing is in itself a remarkable act.

credit: Sara Faruqi, dawn.com

As a former bonded labourer in her mid-fifties with 20 grandchildren, Kohli’s journey to election hopeful is the stuff of legend. And Oxfam’s Raising Her Voice programme is proud to have played a small part in her success.

Kohli is one of the 1,500 women’s leaders who have been supported by the Aurat Foundation and Oxfam through training, exchange visits, information sharing and mentoring as part of the Raising Her Voice programme, seeking to support women’s political participation and leadership in 17 countries worldwide.

Pakistan can lay claim to the Muslim world’s first ever woman prime minister and elected Speaker of a National Assembly and yet there is a glaring disconnect between constitutional rights and customary or Islamic laws.

That makes it very hard to overtly organize women in public. But women can still talk to women in ways that outsiders can’t, so RHV’s vehicle of choice has been ‘Women’s Leadership Groups’ (WLGs). RHV has supported 30 such groups, of about 50 women each. The women in them are mainly educated, some with party political connections, but an increasing number, like Kohli, are poor.

They have been recruited as WLGs have reached out to less well educated, less confident and poorer women in their communities – we reckon some 187,500 Pakistani women have benefited from the programme.

The WLGs have provided safety and strength in numbers, enhancing the potential to form alliances and gain influence which has brought political, economic and social benefits:

- In Hafizabad (a district of Punjab Province) over half the members of the zakat – Islamic relief – committees are from WLGs.

- Sindh district level committees – such as education – now have 2 to 4 women from WLGs.

- Nationally, 116,000 women have obtained national identity cards with the help of WLGs.

- In Attack (a district of Punjab Province) WLG negotiations with village councils (panchayats) have brought an end to honour killings.

- In some areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, some Awami National Party (ANP) workers were stopping women from voting in the 2013 general elections, until the WLG raised it with ANP leadership who took action against the offending party workers.

Reinforcing the grassroots activism of the WLGs has been the indefatigable advocacy and campaigning of Oxfam’s partner, the Aurat Foundation (AF). Media savvy, an influential player within Pakistani civil society and internationally well connected, AF is a skilful navigator of Pakistan’s political undercurrents.

AF strives to influence the structures – laws, political processes, traditional and institutional centres of power – that disenfranchise Pakistan’s women and curtail fulfilment of the country’s true potential.

Today the Aurat Foundation and Oxfam launch The Politics of Our Lives: The Raising Her Voice in Pakistan Experience, a report documenting the learning from RHV’s work with AF in Pakistan. It makes essential reading for those wishing to support programmes seeking to shift the balance of power between the sexes in countries where getting it wrong can have very serious consequences. A ‘road map’ it isn’t, that would be too prescriptive, but it is a valuable resource for governance practitioners. And beyond this, documents the remarkable achievements, conviction and stamina of the women leaders and their advocates, who, like Veeru Kohli, have pushed the boundaries ‘against all odds’.

As Veeru said: “Initially I was not fully prepared, but then I thought, this could be done only by me, so I went all the way…”

The RHV programme in Pakistan received total funding from DFID of £445,257 over five years

And here’s a 5 minute video of Veeru, courtesy of dawn.com

Veeru Kohli from Dawn.com on Vimeo.

July 3, 2013

Oil spills, prisons and the madness of GDP

“Average national income is a notoriously imperfect measure of the average person’s well-being. The 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico – with clean-up and damage costs of $90 billion – added about $300 to the average American’s “income.” But it added nothing to our well-being. The world’s most expensive prison system, costing almost $40 billion per year, adds another $125 per person. This doesn’t make us better-off than people living in countries that don’t incarcerate one in every 100 adults.”

clean-up and damage costs of $90 billion – added about $300 to the average American’s “income.” But it added nothing to our well-being. The world’s most expensive prison system, costing almost $40 billion per year, adds another $125 per person. This doesn’t make us better-off than people living in countries that don’t incarcerate one in every 100 adults.”

James Boyce with a powerful critique of GDP as a measure of progress, and what it implies for discussions on ‘limits to growth’

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers