Duncan Green's Blog, page 210

July 30, 2013

Campaigning on Hot v Cold Issues – what’s the difference?

I recently began an interesting conversation with our new campaigns and policy czar, Ben Phillips, who then asked me to pick the FP2P collective brain-hive for further ideas. Here goes.

The issue is ‘cold’ v ‘hot’ campaigning. Over the next couple of years, we will be doing a lot of campaigning on climate change and inequality. Inequality is flavour of the month, with an avalanche of policy papers, shifting institutional positions at the IMF etc highlighting its negative impacts on growth, wellbeing, poverty reduction, and just about everything else. That makes for a ‘hot campaign’, pushing on (slightly more) open doors on tax, social protection etc.

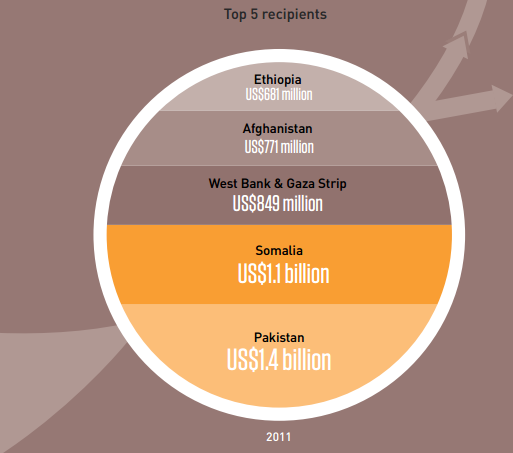

In contrast, climate change is (paradoxically) a pretty cold campaign. Emissions continue to rise, as do global temperatures and the unpredictability of the weather, but you wouldn’t think so in terms of political agendas or press coverage (see graph). The UN process, focus of huge attention over the last 15 years, is becalmed. Politicians make occasional reference to ‘green growth’, but that is becoming as vacuous as its predecessor ‘sustainable development.’

the weather, but you wouldn’t think so in terms of political agendas or press coverage (see graph). The UN process, focus of huge attention over the last 15 years, is becalmed. Politicians make occasional reference to ‘green growth’, but that is becoming as vacuous as its predecessor ‘sustainable development.’

The distinction is not so clear cut, of course. Hot campaigns can suddenly go cold and vice versa (politicians and officials are able to go from saying ‘no, don’t be ridiculous’ to ‘we’ve always supported this’ with bewildering ease, when the moment is right). You could argue that the Arms Trade Treaty campaign was one of those. But a campaign needs to get seriously hot if it involves a major redistribution of power and influence (like taxation/inequality or climate change, but not, I would argue, the Arms Trade Treaty).

So the essay question is: do you campaign differently on hot v cold campaigns, and if so, how? Here are some initial thoughts:

A hot campaign is about stuff happening in real time – issues ripe and approaching policy tipping points; public and media attention at high levels; politicians looking to put themselves at the head of public opinion and looking for ideas. In those circumstances, I think we pretty much know what to do – build as wide a coalition as possible; make a lot of loud noise through press work, ‘pop mob’ (popular mobilization) and online activism; back it up with short term research, policy ideas and sensible solutions; lace with killer facts and infographics; use joint insider-outsider strategy to exert pressure on decision  makers and keep it there. Think Robin Hood Tax (left).

makers and keep it there. Think Robin Hood Tax (left).

I don’t think we’re nearly as clear on cold campaigning. If we’re aiming to prepare the ground so that things move quickly and in the right direction when climate change does finally make it onto the agenda (through a change of heart among political or business leaders, in response to massive climate shocks or some other development), I think that implies a very different campaign:

We’re nowhere near a tipping point, so don’t dissipate what energy there is by doing ‘one more heave’ style campaigns that try and get people out on the streets. Instead go back and build the movement: upsurges in civil society are rare and short-lived, and when you look more closely at events like the Arab Spring, it rapidly becomes apparent that these mass movements are not homogeneous. As Sidney Tarrow showed (wrt European social movements), they are granular, made up of small, more durable grains such as trade unions, faith organizations, professional associations or, in the case of climate change, local movements like transition towns. So preparing for a distant pop mob means broadening the number of grains – finding new allies through slow patient recruitment of a widening circle of organizations.

Linked to this point, you can try and identify smaller, more winnable hot spots within a generally cold landscape, or piggy back on hotter campaigns (if you can do so without damaging your credibility). Some wins, however small, could become the nuclei of broader mobilisation later on.

There are some influential communities who totally get the gravity of the situation. Insurance Companies. Or scientists – I was struck by the ferocity of an attack by various eminent scientists on government officials at a dinner I attended a few months ago. ‘Growth is exponential; natural resources are finite. It doesn’t add up’ one said, almost shouting. We should be spending more time building relationships with these enlightened insiders.

Getting the framing right: President Obama recently started framing climate change as an issue of our children’s future, rather than (as previously) a way of getting a green growth competitive edge over rival economies. That seems a prescient move, aimed at building a common language that will resonate deeply with a much wider group of people. Strengthening the links with faith teaching on stewardship is another (think what Jubilee 2000 did for debt campaigning). Highlighting the impact of people’s consumption choices may be an exercise in reframing too – not so sure on that one.

Getting the framing right: President Obama recently started framing climate change as an issue of our children’s future, rather than (as previously) a way of getting a green growth competitive edge over rival economies. That seems a prescient move, aimed at building a common language that will resonate deeply with a much wider group of people. Strengthening the links with faith teaching on stewardship is another (think what Jubilee 2000 did for debt campaigning). Highlighting the impact of people’s consumption choices may be an exercise in reframing too – not so sure on that one.Start identifying and weakening the blockers. I find the 3i framework useful for this – what are the ideas, interests and institutions that are blocking progress on climate change? What tools, evidence and allies do we need to neutralise each category?

Research: Political shifts of the magnitude required on climate change are very unlikely to occur because of evidence (or they would have happened already), but when the political stars for action come into alignment, decision-makers will need research and policy solutions, and the quicker the better. Cold campaigning should therefore be as much about assembling the ammunition for when that happens. Readiness is all, rather than trying to flog your climate change papers to an indifferent press and political class.

Next generation: if this is a generational shift, then take the next generation much more seriously. That includes influencing what is taught in schools (UK education minister Michael Gove clearly gets this, judging by his recent failed effort to remove climate change from school curricula), but also identifying and working with tomorrow’s leaders, maybe recruiting and supporting climate change ambassadors in key faculties and universities.

Ambulance chasing. If this is a long-term guerrilla fight, rather than a war of position, we need to be more agile, unpredictable and opportunistic. Grab opportunities, drip the climate change message out whenever there is a credible example of its impact on the weather (and the evidence is steadily growing stronger on attribution).

Set up watchdogs: large organizations find it hard to sustain work on cold issues – they are better at the broad movement, tipping point stuff. So why not put some resources into keepers of the flame, small specialist watchdogs that will monitor developments and ensure evidence and ideas keep getting into the public domain. The Bretton Woods Project is a great example of such an initiative, but there are lots of others.

And now for the controversial bit – what should a cold campaign not do? I reckon

- Don’t go for pop mob unless you have a damned good reason. Nothing more dispiriting that a couple of thousand people trudging through the rain and no-one taking much notice. But does that also apply to online activism?

- Be very sceptical about the ‘invited spaces’ of official process. Yes you can take part in yet another consultation, or rock up at yet another ‘conference of the parties’, but is that really the best use of resources when nothing is going to happen there?

‘conference of the parties’, but is that really the best use of resources when nothing is going to happen there?

- Be very careful about using ‘last chance saloon’ type language, when you know we are very likely to be still here, in a worsening situation, in 10-20 years time.

OK, there’s some initial thoughts – over to you.

July 29, 2013

Are the wheels coming off the BRICS juggernaut?

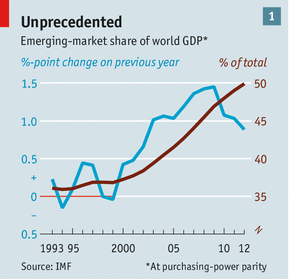

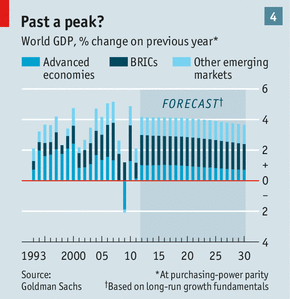

Nouriel Roubini (aka Doctor Doom) and the Economist cover story on the same topic? It must be serious. The issue is whether the glitter is coming off the BRICS growth surge. First the Economist:

‘China will be lucky if it manages to hit its official target of 7.5% growth in 2013, a far cry from the double-digit rates that the country had come to expect in the 2000s. Growth in India (around 5%), Brazil and Russia (around 2.5%) is barely half what it was at the height of the boom. Collectively, emerging markets may (just) match last year’s pace of 5%. That sounds fast compared with the sluggish rich world, but it is the slowest emerging-economy expansion in a decade, barring 2009 when the rich world slumped.

expect in the 2000s. Growth in India (around 5%), Brazil and Russia (around 2.5%) is barely half what it was at the height of the boom. Collectively, emerging markets may (just) match last year’s pace of 5%. That sounds fast compared with the sluggish rich world, but it is the slowest emerging-economy expansion in a decade, barring 2009 when the rich world slumped.

This marks the end of the dramatic first phase of the emerging-market era, which saw such economies jump from 38% of world output to 50% (measured at purchasing-power parity, or PPP) over the past decade.’

However, don’t despair, because ‘a broad emerging-market bust looks unlikely. China is in the midst of a precarious shift from investment-led growth to a more balanced, consumption-based model’ but has enough cash in the piggy bank to get it through any wobbly patches. What’s more ‘most emerging economies have better defences than ever before, with flexible exchange rates, large stashes of foreign-exchange reserves and relatively less debt (much of it in domestic currency).’

But China is definitely running out of puff – an ageing population, less of a technological gulf with the advanced economies (absorbing existing technology is a lot easier than developing new stuff, and so generates very high growth rates).

China’s slowdown has knock-on effects by ending the commodity boom for energy (Russia), metals and grain (Brazil). But the Economist seems at a bit of a loss to explain India’s slowdown.

And from the Economist’s accompanying longer briefing:

‘This year will be the first in which emerging markets account for more than half of world GDP on the basis of purchasing power. In 1990 they accounted for less than a third of a much smaller total.’

Roubini adds a few other elements:

Most emerging-market economies were overheating in 2010-2011, with growth above potential and inflation rising. They needed to slow down.

The idea that emerging-market economies could fully decouple from economic weakness in advanced economies was far-fetched. Contagion from Europe and the US, if only weak, has got to them.

The idea that emerging-market economies could fully decouple from economic weakness in advanced economies was far-fetched. Contagion from Europe and the US, if only weak, has got to them.

‘Most BRICS and a few other emerging markets have moved toward a variant of state capitalism. This implies a slowdown in reforms’. Not sure I buy this – the move to state capitalism kept them out of the clutch of the financial crisis and kept them growing at hyperspeed and now – voila – the very same thing explains their slowdown.

He also makes a pretty unconvincing link to US policy on quantitative easing (not that I am in any position to judge – I barely know what it means).

And prize for best quote goes to the Economist:

‘A rising tide may lift all boats; a falling one reveals who has no bathing trunks on.’

Wish I’d thought of that.

Today’s grimfographic: how many people die a violent death, where and how?

From Action on Armed Violence using data from the Geneva Declaration’s Global Burden of Armed Violence report (whose link seems to be down at the moment). Key points to note:

Only one in 8 violent deaths occur in the ‘conflict settings’ so beloved of news coverage. Most of the rest are ‘intentional homicides’ committed in gun and drug-plagued (but supposedly non-conflict) countries like El Salvador (at 62 deaths per 100,000 people, the world’s most violent ‘peaceful’ country). People often claim the death toll in El Salvador is now worse than during its 1980s civil war, but the numbers don’t seem to add up – 70,000 died over about 12 years in that war, whereas the current carnage kills ‘only’ about 3,600 a year. Latin America remains the world’s homicide hotspot.

Total global death toll is 526,000. That’s a shocking one a minute, but less than half the deaths from road accidents (which I imagine have a similar victim demographic).

But things can improve. The murder rate in El Salvador has halved since the data for this report was gathered, thanks to a truce struck between the country’s two main street gangs.

July 24, 2013

Off to WOMAD, any recommendations on who to see?

It’s the British summer, torrential rain is forecast, so it’s time to grab the wet wipes and head for a festival. Off to WOMAD (World of Music, Art and Dance, 21st year) today – here’s the line-up. All recommendations welcome (best to tweet me on @fp2p, but should be able to read comments too, even on a blackberry). Back next week. Here’s a flavour of the festival.

and currently top of my list, Mali’s wonderful Rokia Traore

July 23, 2013

What Brits say v what they mean: FP2P all time no. 1 hit

What with the summer torpor and being stuck at home finishing a paper, the usual flow of conversations and new reading has dried up a bit. Not only that, but I just realized this blog had passed its fifth anniversary without me even noticing. Tsk. So what better way to plug the occasional gap celebrate than a glance back at the most read posts of the last five years? Given the churn in readership, there’s a fair chance you won’t have seen these – well that’s my excuse anyway. First up, from June 2011 (and number one by a mile), this wonderful deconstruction of Britspeak, c/o Nick Pialek:

July 22, 2013

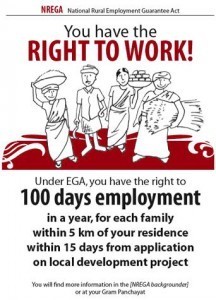

China and India are building welfare states at a scale and speed unprecedented in human history

Take a look at this table, from a new paper by Arjan de Haan. It shows the last 15 years of social policy initiatives in China and India, and their breathtaking scale.

And here’s a chunk from the accompanying one pager:

Though social spending in both countries appears rather low, and many

deficits remain in terms of effective social protection, social policies in both

countries are evolving rapidly, with, for example, in China the world’s largest

rural medical insurance programme, and in India the national rural employment

guarantee scheme (NREGA). Policies vis-à-vis minorities are integral parts of

countries’ social policies, consistent with broader approaches, and in turn

creating the conditions for state–citizen as well as market relationships.

Political and institutional differences between the two countries have a big

impact on how social policies evolve, of course. In China, social policy reforms

are directly driven by the large-scale privatisation which created large gaps in

social protection and growing inequalities and social unrest. The public policy

choices made in the process are the outcome of political contestation— as

they are elsewhere—in turn having significant implications for state–citizen

relations. While striving towards universal coverage, China’s social policy

choices show strong elements of a ‘productivist’ orientation, keeping social

spending low (despite the stimulus package after the financial crisis) and, for

example, poverty alleviation programmes focusing on enhancing productivity

and economic transformation. China’s government balances centralised

decision-making with a process of piloting before rolling out national schemes.

Local governments have a critical role in implementation, reinforcing the

focus on economic investment and keeping social investment low,

particularly in poorer regions.

Approaches in India show remarkable differences from those in China, driven

partly by history, partly by political differences —though social spending in

India too has remained low. Despite an ideology of universalism, social

programmes are often targeted. Political pluralism and ‘vote-bank politics’

have contributed to manifold and often uncoordinated schemes. India’s

social policies have a much stronger emphasis on ‘welfarism’ than China’s—

protecting livelihoods or well-being, with less attention to economic

transformation—for example, in terms of promoting a rural–urban

transition. Like China’s, and perhaps inevitable given the size of both

countries, India’s social policies are implemented through decentralised

structures, with notable successes in terms of enhancing citizens’

participation in implementation, but also potentially under-serving the

poorest areas and increasing fragmentation.

‘Though social spending in both countries appears rather low, and many deficits remain in terms of effective social protection, social policies in both countries are evolving rapidly, with, for example, in China the world’s largest rural medical insurance programme, and in India the national rural employment guarantee scheme (NREGA).

Political and institutional differences between the two countries have a big impact on how social policies evolve. In China, social policy reforms are directly driven by the large-scale privatisation which created large gaps in social protection and growing inequalities and social unrest. The public policy choices made in the process are the outcome of political contestation— as they are elsewhere—in turn having significant implications for state–citizen relations. While striving towards universal coverage, China’s social policy choices show strong elements of a ‘productivist’ orientation, keeping social spending low (despite the stimulus package after the financial crisis) and, for example, poverty alleviation programmes focusing on enhancing productivity and economic transformation.

differences between the two countries have a big impact on how social policies evolve. In China, social policy reforms are directly driven by the large-scale privatisation which created large gaps in social protection and growing inequalities and social unrest. The public policy choices made in the process are the outcome of political contestation— as they are elsewhere—in turn having significant implications for state–citizen relations. While striving towards universal coverage, China’s social policy choices show strong elements of a ‘productivist’ orientation, keeping social spending low (despite the stimulus package after the financial crisis) and, for example, poverty alleviation programmes focusing on enhancing productivity and economic transformation.

Approaches in India show remarkable differences from those in China, driven partly by history, partly by political differences —though social spending in India too has remained low. Despite an ideology of universalism, social programmes are often targeted. Political pluralism and ‘vote-bank politics’ have contributed to manifold and often uncoordinated schemes. India’s social policies have a much stronger emphasis on ‘welfarism’ than China’s— protecting livelihoods or well-being, with less attention to economic transformation—for example, in terms of promoting a rural–urban transition. Like China’s, and perhaps inevitable given the size of both countries, India’s social policies are implemented through decentralised structures, with notable successes in terms of enhancing citizens’ participation in implementation, but also potentially under-serving the poorest areas and increasing fragmentation.’

And if you found that a bit hard to take in, here’s my translation of the interesting bits:

And if you found that a bit hard to take in, here’s my translation of the interesting bits:

1. China and India are introducing basic (low cost) welfare systems on a massive scale, and very fast

2. China initially tried privatising everything, and services collapsed, risking a potential political backlash. So the government jumped into building a welfare system, but wants to keep its eyes on the prize – economic growth. Social policy is about creating healthier, better educated factory workers.

3. India’s more complicated, with a lot of rhetoric about rights, less of a focus on churning out the next generation of workforce (or on where they live), and politicians trading welfare concessions for votes on a small scale, creating an unholy mess overall. India’s deep rooted caste system means decentralization can lead to the lower castes being ignored by the incipient welfare state.

Of course quantity does not mean quality. Lots of criticisms for corruption and inconsistency – e.g. receiving different payments depending on where you are registered, but still an extraordinary transformation.

July 21, 2013

The Act of Killing: the most astonishing, disturbing, original film I’ve seen in years

We interrupt this blog to urge you to go and see an extraordinary film about Indonesia’s aging executioners. Here’s an extract from an NPR review, the  wikipedia synopsis and the trailer, which gives a sense of its unique combination of the ‘banality of evil‘ of the old men, and the surreal quality of their reenaction. That must be down to its director Joshua Oppenheimer (interviewed here), but it’s no surprise that Werner Herzog signed up as executive producer once he’d seen some early rushes.

wikipedia synopsis and the trailer, which gives a sense of its unique combination of the ‘banality of evil‘ of the old men, and the surreal quality of their reenaction. That must be down to its director Joshua Oppenheimer (interviewed here), but it’s no surprise that Werner Herzog signed up as executive producer once he’d seen some early rushes.

I’m no Indonesia expert, but it seems to get beneath the skin of a country that is often described with reference to its shadow puppet theatre – nothing is as it seems etc. I’d love to hear the views of Indonesians, or people who know the country and its history.

First the NPR Review:

“Genocide in Indonesia.” Those words probably don’t make you want to rush out to see a new movie. But what if we add these: Genocide in Indonesia, with gangsters, cowboys, dancing girls, men in drag and splashy musical numbers. They’re all part of the year’s strangest documentary, The Act of Killing.

The opening (left) looks like something from a demented Bollywood musical. Costumed girls come dancing out of the mouth of a giant fish, frolicking under a waterfall as a director barks at them to look happy, happier. Standing with them, also getting soaked, are two men, one slender and dressed as a priest, the other fat, in a turquoise satin gown.

The opening (left) looks like something from a demented Bollywood musical. Costumed girls come dancing out of the mouth of a giant fish, frolicking under a waterfall as a director barks at them to look happy, happier. Standing with them, also getting soaked, are two men, one slender and dressed as a priest, the other fat, in a turquoise satin gown.

These two are notorious Indonesian death-squad leaders — men who slaughtered countless civilians they accused of being communists after a military takeover in 1965. And they are not shy in talking about what they’ve done.

But the filmmakers didn’t want a talking-heads documentary, so they offered them a different option: re-enact their stories in whatever cinematic style they like. They like mob movies, and musicals. And this bizarre scene is part of one such re-enactment.’

The synopsis:

When Sukarno was overthrown by Suharto following the failed coup of the 30 September Movement in 1965, the gangsters Anwar Congo and Adi Zulkadry in Medan (North Sumatra) were promoted from selling black market movie theatre tickets to leaders of the most notorious death squad in North Sumatra, as part of the Indonesian killings of 1965–1966. They also extorted ethnic Chinese, killing those who refused to pay. Anwar personally killed approximately 1000 people, usually by strangling with wire.Today, Anwar is revered as a founding father of the right-wing paramilitary organization Pemuda Pancasila that grew out of the death squads.

The organization is so powerful that its leaders include government ministers, and they are happy to boast about everything from corruption and election rigging to genocide. A regime was founded on crimes against humanity, yet has never been held accountable.

Invited by Oppenheimer, Anwar and his friends eagerly re-enact the killings for the cameras, and make dramatic scenes depicting their memories and feelings about the killings. The scenes are produced in the style of their favorite film genres: gangster, western, and musical. Various aspects of Anwar and his friends’ filmmaking process are shown, but as they begin to dramatize Anwar’s own nightmares, the fiction scenes begin to take over the film’s form, leading the film to become increasingly surreal and nightmarish. Oppenheimer has called the result “a documentary of the imagination.”

Some of Anwar’s friends realize that the killings were wrong. Others worry about the consequence of the story on their public image. Younger members of Pemuda Pancasila argue that they should boast about the horror of the massacres, because their terrifying and threatening force is the basis of their power today.

After Anwar plays a victim, he cannot continue. He says that he feels what his victims have felt. Oppenheimer, from behind the camera, points out that it was much worse for the victims, because Anwar is only acting, whereas they were being killed.’

From today’s perspective, the film’s main impact may be in showing the depth of links between the executioners, today’s political leaders and the 3 million-strong Pemuda Pancasila paramilitaries. But that assumes anyone in Indonesia will actually see it – the online reviews suggest it was initially only being shown in secret in Jakarta.

There were times when the film seemed to breach some pretty basic ethics, not least in the obvious trauma of people (including children) drafted in to play victims of the death squads. In an interview with the Jakarta Post, Anwar Congo also claims he was tricked into making the film and has never seen the final version (though it’s hard to feel sorry for him). But the overall result is unforgettable.

And finally, the trailer

July 19, 2013

Why is the EU threatening to cut investment in South Africa?

Bilateral Investment Treaties are one of those nerdy ‘important but dull’ bits of international governance that too often get ignored by NGOs and others. So thanks to Liz May at Traidcraft for drawing my attention to this week’s punch-up between South Africa and the EU.

First the fisticuffs. According to South Africa’s equivalent of the FT, Business Day,

‘Karel De Gucht, the European commissioner for trade, on Wednesday made short shrift of pleasantries in his opening remarks at the second South Africa-EU Business Forum in Pretoria. Mr de Gucht said European investors were watching South Africa carefully after the country unilaterally cut bilateral investment treaties with some European Union (EU) member states, including Belgium and Luxembourg, and indicated it would do the same with about a dozen other countries. He said it might be only a matter of time before European investors looked elsewhere for trade.’

Africa-EU Business Forum in Pretoria. Mr de Gucht said European investors were watching South Africa carefully after the country unilaterally cut bilateral investment treaties with some European Union (EU) member states, including Belgium and Luxembourg, and indicated it would do the same with about a dozen other countries. He said it might be only a matter of time before European investors looked elsewhere for trade.’

That’s a pretty serious threat – according to Business Day ‘in 2010 the EU accounted for 88% of total investment stock in South Africa’ (I assume it means foreign investment, but it doesn’t specify).

But the South African government feels it has no option, because companies have begun to use BITs to sue it for, among other things, pursuing affirmative action policies. According to a useful briefing from IISD, the rethink started with a 2007 claim by several Italian citizens and a Luxembourg corporation, filed under the Belgium-Luxembourg BIT with South Africa. The claimants charged that the 2004 Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA)—part of South Africa’s efforts to increase participation by historically disadvantaged South Africans in the mining industry through so-called Black Economic Empowerment legislation —amounted to the expropriation of their mineral rights.

South Africa was forced to settle (terms unknown) in 2010, prompting the government to reconsider its investment treaty policies. A report issued by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) concluded:

“Existing international investment agreements are based on a 50-year-old model that remains focused on the interests of investors from developed countries. Major issues of concern for developing countries are not being addressed in the BIT negotiating processes”.

Globally BITs have been signed by the hundred over the last 20 years, often using boilerplate text with only minimal scrutiny. In South Africa, they came in a rush after the end of apartheid in 1994. According to a Traidcraft Briefing, by 2012, there were 2,833 BITs, of which have over 1,200 involve EU member states. The UK alone has an estimated 98 in force. BITs create a ‘regulatory chill’, deterring governments from action and locking in the Washington Consensus policies of liberalization, even as many governments have started to rethink areas like industrial policy.

The heart of the problem is that BITs are often attempts at ‘kicking away the ladder’, in the words of Ha-Joon Chang (and Friedrich List before him), preventing developing countries like South Africa from pursuing the policies that worked for now developed countries – not only the East Asian tigers, but the US and Germany in previous centuries. Often these have involved differentiating between foreign and domestic companies, but this has now been branded ‘discrimination’ and outlawed by numerous BITs and other treaties.

BITs are also proving a bonanza for lawyers and litigious companies. In 2011, there were 450 known cases being brought, up from 15 in 2000, and the American Lawyer magazine reported on 113 BITs cases that involved costs of at least $100 million. In 2012, Ecuador was ordered to pay $1.77 billion under the terms of the Ecuador-US BIT, in compensation to Occidental Petroleum for terminating an oil exploration contract – an award equivalent to Ecuador’s entire education budget.

BITs are also proving a bonanza for lawyers and litigious companies. In 2011, there were 450 known cases being brought, up from 15 in 2000, and the American Lawyer magazine reported on 113 BITs cases that involved costs of at least $100 million. In 2012, Ecuador was ordered to pay $1.77 billion under the terms of the Ecuador-US BIT, in compensation to Occidental Petroleum for terminating an oil exploration contract – an award equivalent to Ecuador’s entire education budget.

Now governments like South Africa are starting to try and get rid of or revise the bad ones, but the bullying tone adopted by Mr de Gucht suggests that won’t be easy.

Last word to Traidcraft, in a comment on the Business Day piece:

‘The threat of million if not billion dollar compensation claims by foreign investors when government policy threatens to undermine the profitability of their investment is reducing policy space. The fact is that BITs are not necessary to attract investment (Brazil has no BIT); a stable economy with growth prospects or even just an abundance of natural resources is sufficient to attract foreign investors. And let’s not forget that every investment will be governed by a contract as well so there is no need for the state to absorb most investment risks through BITs as well. South Africa has had much foresight to change their position on BITs to ensure their sovereign right to decide their own policies. Hopefully, other countries including the EU will follow.’

July 18, 2013

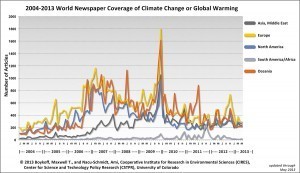

Main trends in humanitarian aid 2012: less successful appeals; rise of Turkey; poor countries doing a lot of the heavy lifting

This year’s Global Humanitarian Assistance Report reports on a ‘quiet year’ (i.e. no mega disasters) in 2012 for global humanitarian aid. Total aid fell to $17.9bn from $19.4bn in 2011. That’s only a small fraction of total aid, but emergencies carry disproportionate weight in public perceptions. A few other points to note, plus some chunks of the inevitable infographic.

A grim update on the toll from the hunger crisis in Somalia: 257,000 (4.6% of the total population) died from 2010-12.

An absence of mega-disasters makes fundraising for less catastrophic crises harder: The proportion of total UN humanitarian appeals met in 2012 (62.7%) was the lowest for a decade.

Turkey was the fourth-largest donor of humanitarian assistance in 2012 (over US$1bn or 0.13% of GNI). This illustrates the rising significance of ‘emerging’ donors but also more comprehensive reporting of humanitarian assistance from a much wider range of providers. More on the rise of Turkey here.

Many of the poorest countries provide humanitarian assistance by hosting refugees – for example Pakistan hosted over 1.7m refugees in 2011, Kenya 567,000 and Chad 367,000.

Lots of positive developments in humanitarianism, including more cash transfers, an increased focus on resilience, access to info and more attention to disaster prevention and preparedness.

The most recent figures for recipient countries are 2011, so Syria won’t feature til next year.

July 17, 2013

Some good news (and lots of guidance) on tackling Violence Against Women

I’m just finalising the first draft of a paper on how states have empowered excluded groups of people (more on that to follow). It’s pretty wide-ranging, as you can imagine, but one of the most striking areas of my reading was on Violence Against Women – a critical barrier to empowerment in far too many communities. There really is a lot going on, and quite a bit of good news. Here are some snapshots:

as you can imagine, but one of the most striking areas of my reading was on Violence Against Women – a critical barrier to empowerment in far too many communities. There really is a lot going on, and quite a bit of good news. Here are some snapshots:

In March, Nigeria’s House of Representatives passed a Violence against Persons (Prohibition) Bill, including a more comprehensive definition of rape, harsher sentences for rape and other sexual offences, compensation for rape victims, institutional protection from further abuse through restraining orders and a new fund to support the rehabilitation of victims of violence.

According to a recent blog post by Oxfam’s Jacky Repila:

‘So, who and what made the difference between the rejection of the bill in 2003 and its approval in 2013, with only minor modifications? Step forward Oxfam’s partner WRAPA – or the Women’s Rights’ Advancement and Protection Alternative. This organisation has first-hand experience of the consequences of violent crime gained through providing legal aid and counselling services since 1999. As Secretariat for the Legislative Advocacy Coalition on Violence Against Women (LACVAW) WRAPA has tirelessly built up a head of pressure on parliamentarians to vote in the VAPP Bill, powered by national and pan-African advocacy and policy connections and the critical mass of seventeen civil society, faith and community groups galvanising support from across Nigeria’s ethnic groups and states.

In 2008 WRAPA starting working with Oxfam’s Raising Her Voice Programme (RHV). The partnership added renewed momentum to the push for poor women’s participation and the domestication of the African Union Women’s Protocol and breathed new life into WRAPA’s campaigning and advocacy around the VAPP bill.’

If you want more on the Nigeria experience, there’s also a four page background paper by Fiona Gell.

There’s some interesting Ushahidi-based crowd mapping of VAW going on in Cambodia, Egypt, India and elsewhere (thanks to Open Data Research and @sushoban for the links)

Then the latest edition of the excellent (and very pink) Gender and Development journal has a piece on the ‘pink transportation’ movement in Mexico City (which reminds me of the famous pink telephone project in Cambodia – is pink universal now?):

‘Rapid urbanization and rising complaints by women of sexual harassment in the public transit system have led to a need and demand for women-only transportation in many cities, including Mexico City, Bangkok, Tokyo, Dubai, Moscow, and Rio de Janeiro.

In Mexico City in 2009, INMUJERES (a women’s rights-focused state institution) implemented a programme called Viajemos Seguras (We Women Travel Safe). Viajemos Seguras established booths, hotlines, and other security offices throughout subway stations and bus terminals, giving women a safe and secure place to report crimes.

In Mexico City in 2009, INMUJERES (a women’s rights-focused state institution) implemented a programme called Viajemos Seguras (We Women Travel Safe). Viajemos Seguras established booths, hotlines, and other security offices throughout subway stations and bus terminals, giving women a safe and secure place to report crimes.

Secondly, INMUJERES converted some previously invisible women-only transportation into ‘pink transportation’, turning it into a visual campaign to publicize the problem of violence against women. Lastly, it helped establish a line of pink taxis: cabs driven by women, only stopping for women (see pic). Researchers concluded that the Mexico City experience shows a clear role for state authorities in the city in creating a liberated space to support collective action.’

I also got myself an update on the spread of women’s police stations, c/o UN Women:

“Examples of specific state action to reduce violence against women include the creation of women’s police stations in 15 countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia. Most commonly the stations address family violence, particularly physical violence, threats, as well as sexual violence. They are often staffed by specially trained female personnel and aim to improve the ability of the police to respond to the unique needs of women survivors. In India, a study found that the establishment of 188 women’s police stations resulted in a 23 percent increase in reporting of crimes against women and children and a higher conviction rate.”

For more substantial treatments, DFID has a great three part series of ‘How to’ Notes on Violence Against Women and Girls, covering its theory of change, a guide to community programming, and monitoring and evaluation. Oxfam also has a good Guide to Ending Violence Against Women.

Then of course there is the amazing We Can campaign, and the brave campaign against the grim phenomenon of ‘femicide’ in Honduras.

More generally, if you want to know why governments take action, evidence collected over 70 countries across 40 years by S Laurel Weldon and Mala Htun shows the single most important predictor that states will successfully reduce violence against women is the existence of a vibrant national women’s movement.

Important and often inspiring (despite the horrendous proliferation of acronyms), but just in case you think I’ve been at the koolaid, here’s a reminder of how slow progress on VAW has been, from a recent World Bank report on the positive, but painfully slow, reduction in violence (or at least the perception of it). At which point I step back and let everyone query the (doubtlessly dodgy) stats.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers