Duncan Green's Blog, page 208

August 27, 2013

On a speaking tour in Australia and New Zealand for next 3 weeks – here are the details

I’m off to Australia and New Zealand this weekend, to teach a 3 day session on ‘how change happens’ with the wonderful Canberra, Wellington and Auckland. Current list of public events and contacts below (c/o the wonderful Helen Moreno), and we (by which I mean Helen) will keep it updated on the website (or via twitter – @fp2p or Facebook) as new details come in. In addition to these public events, I’ll be meeting staff at Oxfam, Ausaid and elsewhere.

Perth, Australia

2 September – ‘What’s Hot and What’s Not in International Development’ Seminar, Open to the public.

Venue: Room LL1.004, Learning Link, School of Management and Governance Building 512, Murdoch University

Time: 12.00-1.00pm

To book a place contact Linda Rossi, L.Rossi[at]murdoch.edu.au by Thursday 29 August

6 September - Oxfam Western Australia public meeting

Venue: One40William, Level 3, Gordon Stephenson House,,140 William Street

Time: 5pm

Melbourne, Australia

10 September – DETalks (Development Effectiveness Talks) What’s Hot & What’s Not: How is Thinking in International Development Changing?

Venue: Theatre 108, The University of Melbourne Law School, Carlton

Time: 1.15-2.15pm

10 September – Active Citizenship and development talk and book launch

Venue: Village Roadshow Theatrette, State Library of Victoria, 179 La Trobe Street, Melbourne

Time: 5.30–7.30pm

Canberra, Australia

12 September - How do we plan, campaign and work in development when we don’t know what is going to happen and we don’t know what solutions will work? The reality of doing development in complex systems.

Venue: Finkel Lecture Theatre, John Curtin School of Medical Research, Building 131, Garran Road, ANU

Time: 6.00-7.00pm

To book a place contact Macarena Rojas, macarena.rojas@anu.edu.au

Wellington, New Zealand

16 September – Insights on Models of Change: a global and Pacific perspective

The seminar will be presented by Duncan Green and Barry Coates, Executive Director of Oxfam New Zealand.

Hosted by: Institute of Governance and Policy Studies (IGPS) and Oxfam New Zealand

Venue: Government Building, Lecture Theatre 1, Institute of Governance and Policy Studies (IGPS), Victoria University of Wellington, GB LT1, Stout St, Thorndon

Time: 5:45-7:15pm

Auckland, New Zealand

18 September - Insights on Models of Change: a global and Pacific perspective

The seminar will be presented by Duncan Green and Barry Coates, Executive Director of Oxfam New Zealand.

Venue: Auckland University, Engineering Lecture Theatre 403-403, 20 Symonds Street, City Campus

Time: 6.00-7.30pm

And no I won’t be mentioning the cricket. Or the rugby. Doh!

August 26, 2013

Now that’s what I call social protection: the Chile Solidario Programme

Another one of the fascinating case studies dug up by Sophie King for my recent UN paper on ‘The Role of the State in Empowering Poor and Excluded Groups and Individuals’. This one looks at how Chile manages its integrated social protection programme and is based on a paper by the excellent Stephanie Barrientos. Reading it really brings home the rapid erosion of any real distinction between North and South. Not at all sure UK provision is as good as this.

Groups and Individuals’. This one looks at how Chile manages its integrated social protection programme and is based on a paper by the excellent Stephanie Barrientos. Reading it really brings home the rapid erosion of any real distinction between North and South. Not at all sure UK provision is as good as this.

The Chile Solidario integrated anti-poverty programme was introduced by Government in 2002 as part of a wider drive to eradicate extreme poverty. It was designed according to a multi-dimensional understanding of poverty and capabilities to target 225,000 indigenous households using national socio-economic survey data.

When they first join the programme, households are allocated a ‘household support worker’ and an income transfer. Their support worker holds a series of collective sessions with all the members of the households to identify capability deficits across 7 dimensions of well-being, each with a set of minimum thresholds: education, health, employment, household dynamics, income, housing and registration. Examples of minimum thresholds include being recorded in the civil registry; children being up to date with immunisations; children below 15 attending school and regularized occupancy of land and housing. In these support sessions, household members discuss how to overcome these deficits, and commitments are made by both themselves and their support worker who is also responsible for linking members up to relevant programmes and services. The aim is for 70% of  households to meet all the minimum thresholds within each of the seven dimensions of capability at the end of the first two years of their participation in the programme. Access to public programmes and the income transfer continues for another three years.

households to meet all the minimum thresholds within each of the seven dimensions of capability at the end of the first two years of their participation in the programme. Access to public programmes and the income transfer continues for another three years.

Results:

By 2005, 86.9% of eligible households had been contacted and 51,441 had exited the programme as intended

Successive evaluations have demonstrated ‘high levels of satisfaction and achievement’ and the most recent three year evaluation particularly highlights achievements for employment outcomes throughout participating households.

Drivers of success:

The programme is innovative because it attempts to address the structural causes of poverty, while focusing on strengthening capabilities in relation to the minimum thresholds described above, and engaging the most disadvantaged

Challenges/limitations:

The thresholds were set without any input from beneficiaries raising questions as to how comprehensive a set of capabilities the programme is focused on

Attainment of capability is measured by a yes/no evaluation in relation to issues such as ‘registered with primary health care unit’ or ‘children below 15 attend school’. Some critics suggest that this does not fully capture different levels of capability

Questions have been raised about the approach to measuring eligibility for the programme

All the online sources seem to be 2010 or earlier – can anyone give us an update on how Chile Solidario is doing?

August 22, 2013

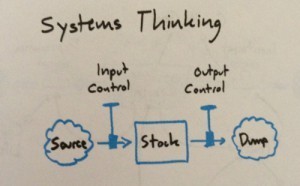

How to think in Systems? Great (and accessible, and short) book.

Thanks to whoever suggested I read ‘Thinking in Systems’, by Donella Meadows. It’s great – one of those short, easy reads that may induce a gestalt shift in the way you see the world. The topic is ‘systems theory’ – that phrase that wise-looking wonks bandy about in meetings, to intimidating effect. If you can’t beat them, then I suggestion you join them by reading this.

shift in the way you see the world. The topic is ‘systems theory’ – that phrase that wise-looking wonks bandy about in meetings, to intimidating effect. If you can’t beat them, then I suggestion you join them by reading this.

Meadows, an MIT systems guru, finished the draft of this book in 1993, and it circulated informally for years, without being published. She died suddenly and prematurely in 2001, before she could finish it. Diana Wright edited it and it was finally published in 2008. It doesn’t feel at all dated – Should we be inspired or depressed when we read a book written 20 years ago that captures virtually every bit of ‘new’ thinking in development?

On to the content: ‘A system is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something.’ It is more than the sum of its parts – eg a body v individual cells; a university v individual students; an ecosystem v an individual plant or animal. A living being is a system, but it loses its system-ness when it dies.

To understand system behaviour over time is to understand

a) Stocks v flows (lots of bathtub-filling models)

b) Feedback (two kinds of loops: reinforcing and balancing – for some reason she avoids ‘positive’ and ‘negative’). Delayed feedback loops (the norm) can lead to wildly different behaviours – dampening, small or very large oscillations.

But the book really gets going when it moves on to the practical implications of systems theory to real life, including politics, starting with a great quote from Czech hero Vaclav Havel:

‘I realize with fright that my impatience for the re-establishment of democracy had something almost communist in it; or, more generally, something rationalist. I had wanted to make history move ahead in the same way that a child pulls on a plant to make it grow more quickly.

I believe we must learn to wait as we learn to create. We have to patiently sow the seeds, assiduously water the earth where they are sown and give the plants the time that is their own. One cannot fool a plant any more than one can fool history.’

Not too hard to apply that to the world of project cycles, theories of change and results, eh?

Aid workers navigating a typical system

As she approaches the end of the book, Meadows gets increasingly lyrical, and concludes with a set of ‘Dancing Lessons’ for those who seek to dance with systems:

Get the Beat of the System: ‘Before you disturb the system in any way, watch how it behaves. Learn its history. Ask people who’ve been around a long time to tell you what has happened. If possible, find or make a time graph of actual data from the system….. Starting with history discourages the common and distracting tendency we all have to define a problem not by the system’s actual behaviour, but by the lack of our favourite solution.’

Expose your mental models to the light of day: ‘mental flexibility – the willingness to redraw boundaries, to notice that a system has shifted into a new mode, to see how to redesign structure – is a necessity. Get your model out there where it can be viewed….. Scientific method is done too seldom even in science, and is done hardly at all in social science or management or government or everyday life.’

Honour, Respect and Distribute Information: there should be an 11th commandment ‘Thou shalt not distort, delay or withhold information.’

Use language with care and enrich it with systems concepts: words matter. ‘we don’t talk about what we see, we see only what we can talk about…A society that talks incessantly about productivity but that hardly understands, much less uses, the word ‘resilience’ is going to become more productive and less resilient.’

Pay attention to what is Important, not just what is Quantifiable: ‘be a walking, noisy Geiger counter that registers the presence or absence of quality’

Make Feedback policies for Feedback systems: design policies that change depending on the state of the system

Go for the Good of the Whole: Aim to enhance total systems properties, such as growth, stability, diversity, resilience and sustainability, whether they are easily measured or not

Listen to the Wisdom of the System: ‘Aid and encourage the forces and structures that help the system run itself. Notice how many of those forces and structures are at the bottom of the hierarchy. Before you charge in to make things better, pay attention to the value of what’s already there.’

Locate Responsibility in the System: in both analysis (look for the ways the system creates its own behaviour) and design (eg internalize pollution costs)

Stay humble, stay a learner: ‘trust my intuition more, and my figuring-out rationality less. The thing to do, when you don’t know, is not to bluff and not to freeze, but to learn.’

Celebrate Complexity: learn to embrace the ‘nonlinear, turbulent and dynamic universe…. [even though] there is something within the human mind that is attracted to straight lines, to uniformity and not diversity, and to certainties and not mystery.’

that is attracted to straight lines, to uniformity and not diversity, and to certainties and not mystery.’

Expand Time Horizons: ‘many native American cultures actively spoke of and considered in their decisions the effects on the seventh generation to come.’

Defy the Disciplines: ‘interdisciplinary communication works only if there is a real problem to be solved and if the representatives from the various disciplines are more committed to solving the problem than to being academically correct.’

Expand the boundary of caring: ‘The real system is interconnected. No part of the human race is separate either from other human beings, or from the global ecosystem.’

Don’t Erode the Goal of Goodness: She ends by quoting literary critic and naturalist Joseph Wood Krutch:

‘Though man has never before been so complacent about what he has, or so confident of his ability to do whatever he sets his mind upon, it is at the same time true that he never before accepted so low an estimate of what he is…. Truly, he is, for all his wealth and power, poor in spirit.’

I’m not sure yet how much this book will change me – watch this space.

August 21, 2013

How empowerment happens: devolving management to local people in Vietnam and Pakistan

Another one of the fascinating case studies dug up by Sophie King for my recent UN paper on ‘The Role of the State in Empowering Poor and Excluded Groups and Individuals’. This one looks at two examples of devolution that seem to work

Devolving forest management to local people, Dak Lak, Vietnam

This is from an FAO case study and an OECD paper

By the mid-1990s the lack of effective provincial forest management in Dak Lak province had resulted in extensive deforestation, as indigenous and migrant groups cleared land for subsistence and commercial production. In 1997, the central government called on the provincial government to curb deforestation and uncontrolled migration. From 1997 the official German development agency GTZ worked in partnership with the provincial department of agriculture and rural development to introduce participatory and sustainable forest management. The programme involved technical assistance to the local government, developing capacity for land-use planning at the commune-level; and land distribution to ethnic minority households. Local people were engaged in developing village-level regulations for land use. Local households were given the rights to forest resources as well as long-term land titles, and families involved in managing the forests were granted a quota of timber and 6% of after-tax value of the timber logged once the forest matures.

migrant groups cleared land for subsistence and commercial production. In 1997, the central government called on the provincial government to curb deforestation and uncontrolled migration. From 1997 the official German development agency GTZ worked in partnership with the provincial department of agriculture and rural development to introduce participatory and sustainable forest management. The programme involved technical assistance to the local government, developing capacity for land-use planning at the commune-level; and land distribution to ethnic minority households. Local people were engaged in developing village-level regulations for land use. Local households were given the rights to forest resources as well as long-term land titles, and families involved in managing the forests were granted a quota of timber and 6% of after-tax value of the timber logged once the forest matures.

Results:

Deforestation slowed down in devolved areas

Between 1999 (the year before devolution was introduced) and 2001/2, the total value of goods harvested from the forest grew by 170%

This harvest accounted for on average 67.6% of non-farm income for participating households

Indigenous groups’ land rights were strengthened

The programme was effectively extended to other forested provinces

Challenges:

The programme did not incorporate aspects of the customary forest governance structure of the local ethnic group

Local people had little or no access to justice in order to defend their new rights – farmers therefore struggled to protect their timber from illegal logging

Tensions remained with local state forestry authorities who experienced a loss of control and associated benefits

Drivers of success:

There was an urgent need for change because of the serious decline in forest resources under state management

Despite tension with the local forestry authority, there was political support for the reforms within the provincial government and strong political commitment from central government, including investment of financial resources

Availability of technical support from GTZ. This was particularly helpful as forest devolution was unprecedented in Vietnam.

The initial emphasis on training and capacity-building of provincial administration.

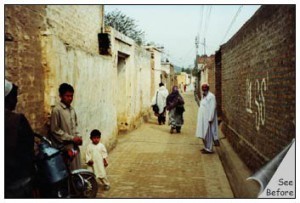

Responding to civil society initiatives – co-production of sanitation in Karachi

This comes from a 2008 study by Diana Mitlin

Orangi is a large informal settlement in Karachi, Pakistan. In 1982, residents suffered from high child mortality rates linked to appalling local living conditions. A local NGO called the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) developed an alternative model for sanitation: ‘the residents of a lane or street paid for the lane investment in sanitation while the municipality took on responsibility for the sewer network into which this fed, and also the waste treatment plants’. After initial reluctance, the municipality eventually agreed to this co-management arrangement and the idea of community-installed and managed sanitation spread rapidly through the settlement.

Orangi is a large informal settlement in Karachi, Pakistan. In 1982, residents suffered from high child mortality rates linked to appalling local living conditions. A local NGO called the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) developed an alternative model for sanitation: ‘the residents of a lane or street paid for the lane investment in sanitation while the municipality took on responsibility for the sewer network into which this fed, and also the waste treatment plants’. After initial reluctance, the municipality eventually agreed to this co-management arrangement and the idea of community-installed and managed sanitation spread rapidly through the settlement.

Results:

The process has strengthened local organisations and made them more likely to engage with formal political structures, rather than operating through clientelist networks

In Orangi, 96,994 houses built their neighbourhood sanitation systems, by investing Rs. 94.29 million (US$ 1.57 million)

20 years after the work began in Orangi, the city of Karachi decided that the strategy should be supported throughout the city

August 20, 2013

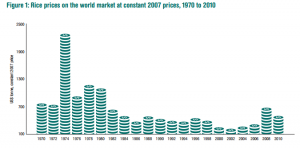

The End of Cheap Rice: Good News or Catastrophe?

Are high food prices here to stay, and if so are they a Good Thing (producers benefit) or a Bad Thing (consumers go hungry)? These are the questions explored by a thought-provoking and very even-handed new paper (only 5 pages) from the ODI on the ‘end of cheap rice’.

From the Summary:

“After more than 30 years of decline as a result of the Green Revolution, rice prices have more than doubled since 2000, rising by almost 120% in real terms. (see unhelpful graph – can we just have line graphs in future please?)

terms. (see unhelpful graph – can we just have line graphs in future please?)

Restocking among major producers and shifts in trade policy have played their part in recent price increases, but are only part of the story. The more fundamental drivers of increased prices are the higher costs of fertiliser, diesel, and labour as rural wages rise in parts of Asia.

Rising rural wages are good news, with potentially far-reaching benefits for poverty reduction in Asia, given that an estimated 1.3 billion of Asia’s poor and vulnerable people depended on rural labouring for their livelihoods in 2008.

But more costly rice is a problem for poor and vulnerable groups that do not share in the benefits of economic growth, both in Asia and in Africa, where coastal cities have become accustomed to cheap rice imports.

The threat posed by higher rice prices calls for social protection policies to guard against price shocks. [Probably no accident that China and India are introducing them at breakneck pace]

In the longer run, however, the rise in rice prices presents an opportunity for African farmers.”

[and on this final point, from the main paper]

“More changes in rice production in parts of Asia may well be coming, as environmental imperatives come into play, including conserving water, avoiding felling forests or converting wetlands, reducing emissions from flooded fields of paddy and controlling the use of agricultural chemicals. This may well mean that some rice-producing areas have to switch to less intensive methods with lower production. To keep up world rice supplies, more rice will, therefore, be needed from other areas. This would present opportunities not only in Latin America, but also in Africa where the first goal would be to replace Asian imports by domestic production, then to export rice from those parts of Africa that have high potential for rice production, such as parts of humid coastal West Africa.

“More changes in rice production in parts of Asia may well be coming, as environmental imperatives come into play, including conserving water, avoiding felling forests or converting wetlands, reducing emissions from flooded fields of paddy and controlling the use of agricultural chemicals. This may well mean that some rice-producing areas have to switch to less intensive methods with lower production. To keep up world rice supplies, more rice will, therefore, be needed from other areas. This would present opportunities not only in Latin America, but also in Africa where the first goal would be to replace Asian imports by domestic production, then to export rice from those parts of Africa that have high potential for rice production, such as parts of humid coastal West Africa.

These potential changes to rice cultivation increase the value of having a range of technical options to allow farmers to adjust to changing opportunities and environmental limits. Some technical options may reap private profits and we can expect to see the major agricultural corporations invest in the necessary research. Most of these technical advances, however, will be public goods and will therefore require an active public research effort. This means that various key bodies need adequate investment, including the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the Africa Rice Center and the national agricultural research systems of current and potential rice producers. Compared to the potential gains, the costs of research have proved low. Policy-makers now need to have the courage to invest sufficiently in this vital research.”

August 19, 2013

The future of Agriculture: useful teaching resource/briefing on current debates

If you’re looking for a teaching resource on current debates on agriculture and development, take a look at ‘The Future of Agriculture’, a rather good synthesis of a two week online debate hosted by Oxfam last December. The paper, written by Maya Manzi and Gine Zwart, has a 10 page summary of the 23 posts and comments from some 300 participants, followed by 60 pages of the posts themselves, with authors from a good spread of disciplines and countries.

synthesis of a two week online debate hosted by Oxfam last December. The paper, written by Maya Manzi and Gine Zwart, has a 10 page summary of the 23 posts and comments from some 300 participants, followed by 60 pages of the posts themselves, with authors from a good spread of disciplines and countries.

The essayists were asked to discuss one of the following:

• What if all farmers had adequate risk management systems to deal with climate trends and shocks, as well as with price volatility in input and product markets?

• What if fossil fuels were no longer required in any form of input to global agricultural production?

• What if all farmers, male and female, had full and equal control over the necessary resources for farming, and over the outputs of their labor?

• What if the ideas and innovations of resource-poor farmers leading to improvements of their natural resource base were supported by adequate access to public and private sector investments?

The summary has sections on:

Risk: lots of support for an enhanced role of the state, but also for exploring a wide range of insurance mechanisms

Fossil Fuel dependence: big spread of opinion about the extent to which we can wean ourselves off FFs while still feeding the planet. The section also touches on GM and Biofuels.

Power and control: As you would expect, a strong element of the debate was that this is not a technical issue, but intimately bound up with power and politics, both at national and household levels (eg via gender inequality). Big emphasis on land reform and producer organization as ways to correct power imbalances.

Investment for innovation: debates on private v public in sources of R&D investment, but also strong arguments for changing our thinking to put more value on local agricultural knowledge systems, rather than men in white coats.

“The online debate showed how difficult it is to think out of the box, and to come up with radical or new thinking. Virtually all of the ideas and solutions put forward were seen to be within reach, lacking only [only?] the political will for implementation.

Only very few people said that a choice is inevitable between the two opposing models of agriculture: permaculture/organic, and oil/chemical dependent. At the same time many contributors suggested that current policies and politics favour the latter. And there was general agreement that multi-pronged approaches are needed, with much more attention paid to the potential of agro-ecological, bio-diverse systems to address problems related to climate change, resource scarcity and fossil fuel dependency.

The labour-intensive agriculture practiced by the estimated 1.5 to 2 billion people currently living in rural food-producing households was seen by many, not as a cause of hunger and poverty, but rather a vehicle for escaping those scourges – if invested in properly. Agriculture is the only sector that can usefully absorb a large labour force. Several referred to the fact that in many developing countries small-scale producers are the largest source of investment in agriculture, biodiversity, and related knowledge systems. Too often, however, government policies marginalize them, or create incentives geared to supporting commercial investments that compete with, or displace these small-scale producers. There is no denying that enormous capital flows and practices of both private and public institutions are geared towards industrial-scale production. This debate has shown that redressing this imbalance is a critical challenge for all stakeholders.”

August 18, 2013

Why NGOs label technology as nasty or nice

This post appeared last week on the Science and Development website SciDev

There’s real substance behind activists’ polarised views of new technology, says Oxfam adviser Duncan Green.

NGOs and activists often seem to hold contradictory views about science and technology, dividing the world up into ‘nice’ and ‘nasty’ technologies. Anything to do with mobile phones, crowdsourcing, ’small is beautiful’ technology, renewables or labour-saving wonders such as washing machines is typically met with approval. Not so with nuclear power, big dams, nanotechnology, geoengineering and, of course, genetic modification (GM).

As a long-obsolete science graduate (physics), I used to be rather scornful of this inconsistent approach to such a crucial issue in development. Can anyone seriously argue that science and technology are irrelevant to the massive gains in health, education and life expectancy over the last 60 years?

But on closer inspection, this polarised simplification may not be so foolish after all.

Real substance

New technologies may be exciting, but they are often also disruptive. Some can have disastrous consequences (think biological weapons), while others are forces for good — sooner or later.

New technologies may be only temporarily nasty — engines of what the economist Joseph Schumpeter called the ‘creative destruction’ that drives economic progress. Take the synthetic fertilisers that made ghost towns of Chile’s thriving nitrate mines in the early twentieth century; they also triggered a productivity boom in European agriculture that fed millions.

But the nice-nasty division has real substance, especially when seen through the prism of power, control and whether adopting the technology in question exacerbates or reduces inequality. Do newagricultural technologies, including GM, favour small farmers or large agribusiness? If the latter, expect rising inequality and a new wave of smallholders driven off their land.

Governance and money shape the impact of new technologies. In an age when so much research & development has moved out of the public sector, private companies are most likely to follow the money — which means producing technologies for the rich and powerful, even if they come at the expense of the rest.

This is also the case with debates over intellectual property rights for new medicines, which are driven by large industry lobby groups.

Nice versus nasty

Nice technologies seem to have certain characteristics in common: they tend to be dispersed, both in terms of production (small-scale renewables) and use (mobile phones); people can decide whether or not to use them; and if something goes wrong, their adoption can be reversed.

Nasty technologies, on the other hand, tend to be controlled by a small number of large companies (GM) and are sometimes irreversible in their consequences (Fukushima, Chernobyl).

Such subtleties are lost on politicians, who gather round new technology like moths to a flame. They want to look modern, but they also love technology because it seems to offer an apolitical get-out-of-jail-free card to otherwise intractable problems.

Such subtleties are lost on politicians, who gather round new technology like moths to a flame. They want to look modern, but they also love technology because it seems to offer an apolitical get-out-of-jail-free card to otherwise intractable problems.

Currently the greatest of these is climate change. Carbon emissions are rising and most political leaders trumpet ‘green growth’ as the solution. There’s nothing wrong with that, except there is little prospect of the kind of full decoupling of future growth from increasing total carbon emissions that is required to curb climate change. [1]

Of the two other options, one (accepting limits to growth) is generally seen, not without reason, as political suicide. The other is a different kind of tech fix: geo-engineering.

Geoengineering the climate

Geoengineering schemes to pump water into the sky or surround the earth with tin foil, convey a Dr. Strangelove image. But the technology is surely going to become both more serious and more salient as both the green growth and emissions reductions routes to climate mitigation fail.

What worries me is that geoengineering has all the characteristics of a nasty technology: it would involve planetary scale experiments by a small group of players with potentially irreversible consequences.

Its promotion also suits those who are simply playing for time by creating a false sense of certainty (a bit like carbon capture and storage) that weakens the sense of urgency around cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

And geoengineering is likely to affect poor people. If it is decided to dump millions of tonnes of iron filings into the ocean to generate carbon dioxide-absorbing algal blooms, it is much more likely to happen off the coast of Africa than next to a UK holiday spot such as Brighton (think of the insurance bill, if nothing else). [2]

Keeping up with science

All this means that activist NGOs need to think more about the social impact of new technologies — but also to pick our battles. Mobile phones and washing machines seem to have managed perfectly well without watchdogs.

Activist NGOs should focus where issues of ethics and injustice are starkest — for example on intellectual property and access to medicines. To make those judgement calls, we need at least some capacity to stay abreast of scientific developments and their social consequences.

That’s easier said than done as highlighted only recently by the NGO Practical Action’s struggle to appoint someone to work on technology policy. The counterargument is that, if we engage with debates on a new technology — whether that’s GM, geo-engineering or nanotech — we risk legitimising the nasty stuff.

This is true to some extent. But if they are in the pipeline anyway, we need at least to understand them better.

August 17, 2013

Is the pressure to keep overheads low and avoid failure holding charities back? Watch this TED talk and tell me what you think

Following all the hoohaa about charity boss salaries, including my own small peanutgate contribution, several people sent me links to this intriguing TED talk by Dan Pallotta, which I found partly convincing, but also rather uncomfortable viewing. I’d be really interested in your reactions:

August 15, 2013

Why you should become a development blogger. And some thoughts on how to enjoy it.

I think it’s time for some new development bloggers. Lots of new voices to oxygenate a sphere that is starting to feel a little stale. Let’s see if I can persuade you to sign up (NGO types tend not to jump at the chance). First the benefits:

up (NGO types tend not to jump at the chance). First the benefits:

A blog is like a cumulative, realtime download of your brain – everything that you’ve read, said, or talked about for years. All in one place. There’s even a search engine – a blessing if your memory’s as bad as mine. When someone asks you for something, you can dig up the link in no time. If you’re writing longer papers you can start with a cut and paste of the relevant posts and take it from there.

It gives you a bit of soft power (let’s not exaggerate this, but check out slide 15 of this research presentation for some evidence). Blogs are now an established part of the chattersphere/public conversation, so you get a chance to put your favourite ideas out there, and spin those of others. People in your organization may well read your blogs and tweets even if they don’t read your emails.

And don’t forget the free books, also known as ‘review copies’. And the chance to publicly insult your enemies (not relevant in my case, obvs, as I don’t have any).

Downsides?

Time: this blog eats up about a third of my working time. There are ways round this – don’t post so much, or put together a blogging stable like Global Dashboard, but take care to try and ensure that there is some kind of coherent whole, rather than a cyberspace speakers’ corner.

Snark: Blogs are a unique way for individuals and organizations to have unmediated conversations about stuff that matters. The standard of comment and debate on this blog is amazing. But elsewhere be trolls – not everyone arrives looking for intelligent discussion. If you like conflict, blogging is definitely for you. But if you write something nasty, sleep on it before posting. And don’t dish out the abuse, if receiving it straight back upsets you. If you’re foolish enough to post anything on the Guardian Comment is Free site, which seems to offer free venting therapy, you might want to skip reading the comments.

Snark: Blogs are a unique way for individuals and organizations to have unmediated conversations about stuff that matters. The standard of comment and debate on this blog is amazing. But elsewhere be trolls – not everyone arrives looking for intelligent discussion. If you like conflict, blogging is definitely for you. But if you write something nasty, sleep on it before posting. And don’t dish out the abuse, if receiving it straight back upsets you. If you’re foolish enough to post anything on the Guardian Comment is Free site, which seems to offer free venting therapy, you might want to skip reading the comments.

Convinced? Then to start you off, here are ten fairly mediocre tips on blogging in NGOs:

Manage (and respect) your organization. It is (on a good day) a fantastic source of ideas, guest bloggers, on-the-ground experience. But it’s also a potential nightmare of hassle if you screw up. So don’t. Consult in advance; avoid minefields; make it clear your voice is personal, not institutional. And grovel shamelessly if you do ruffle the odd feather (peanuts and monkeys anyone?). The less you screw up, the more leeway you can ask for to blog without a lot of deadening sign-off constraints.

Stamina: blogs take years to get established. Don’t write a flurry of posts and then go dark. Develop ways to generate new content. Try new things out. Encourage guest posts. Cultivate the mini observer on your shoulder, spotting those morsels in the daily round of conversations, meetings, reading matter that might just make a tasty post.

Tone: The blog has to be your voice, so write like you talk. Relax. Don’t be worthy, pompous or harangue. Don’t treat people as idiots or empty vessels. Admit doubt and complexity. Be funny (if that’s your bag). Ask questions even though (especially when) you don’t have answers. In fact, unlearn almost every bad habit of NGO communications.

Spend time on the title: what will make people click on it, when it’s in a list of 50 other titles on their RSS feed? Be direct – people will skip over clever puns which don’t tell them what the post is about. Questions, ideas, not boring things like ‘Participation is insufficient in the Post 2015 process’. Would you click on that? (Apologies if your answer is yes, but you may need to get out more).

Think about the reader: you need to earn their attention. Saving people time is always appreciated – summarize the key documents, review books. Give them content as well as spin. Lighten the load with visuals and videos. Lots of links in case they want to dig.

Interact: blogs are conversations. Respond to comments. Ask people questions. Why don’t more blogs run polls? Use twitter to boost traffic and interaction.

Be generous: credit everyone. For ideas, sources, guest posts etc – it’s only fair, and then they’ll come back with more! (So thanks to Al Kinley for comments on this post.)

Don’t post at weekends (reader numbers halve on Saturday and Sunday)

Find yourself a blogmaster/mistress, someone who is willing (sometimes for chocolate and/or beer) to iron out any glitches (as the wonderful Eddy Lambert did this morning). But do the graphics

yourself – it’s actually quite fun, a job for when your brain has seized up for anything more demanding.

yourself – it’s actually quite fun, a job for when your brain has seized up for anything more demanding.Enjoy yourself. Blogging shouldn’t be terrifying or burdensome. If it is, do something else. Go on, have fun – readers will notice and respond.

And you’ll be able to find the link to that great paper you read last month (and even what you thought about it).

Other guides to blogging, especially for developmentistas?

August 14, 2013

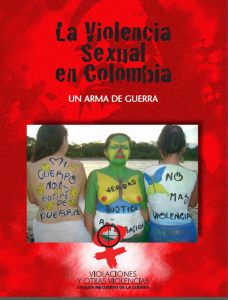

What’s the link between feminist movements and Violence Against Women?

There’s a fascinating, brilliant and I think, very significant, piece on the role of feminism in driving action on violence against women in the latest issue of Gender and Development (ungated versions on Oxfam policy and practice website, please note).

of Gender and Development (ungated versions on Oxfam policy and practice website, please note).

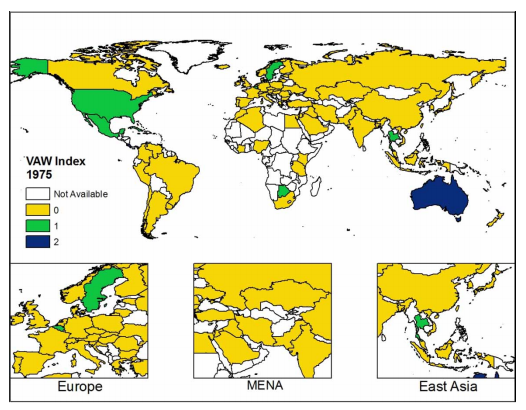

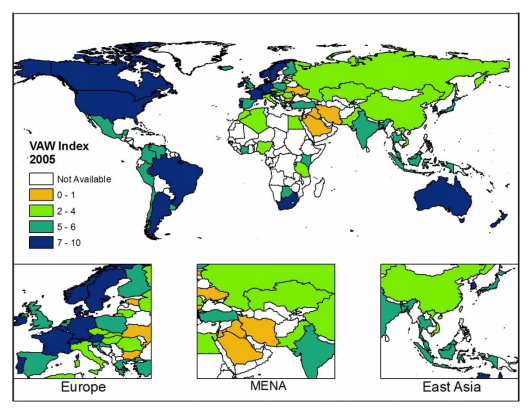

Authors Laurel Weldon and Mala Htun have painstakingly constructed the mother of all databases, covering 70 countries over four decades (1975 to 2005). It includes various kinds of state action (legal and administrative reforms, protection and prevention, training for officials), and a number of other relevant factors, such as the presence of women legislators, GDP per capita, the nature of the political regime etc.

This allows them both to chart steady improvements in VaW policy (see maps at bottom of this piece) and to use stats techniques to try and identify those factors most closely correlated with state action. Here’s what they find:

“Countries with the strongest feminist movements tend, other things being equal, to have more comprehensive policies on violence against women than those with weaker or non-existent movements. This plays a more important role than left-wing parties, numbers of women legislators, or even national wealth.

These movements can make the difference between having a critical legal reform or funding for shelters or training for the police, and not having it…. women’s status agencies, international norms, and other factors further strengthen feminist efforts…

Women’s autonomous organising has played a critical role for three reasons. First, women organising as women generate social knowledge about women’s position as a group in society. The problem of violence surfaces as an issue of primary concern when women come together to discuss their priorities as women.

Second, the issue of violence against women challenges, rather than reinforces, established gender roles in most places. In contrast with ‘maternalist’ issues such as maternity leave or child-care, for which women can advocate without straying too far from traditional gender scripts (that is, conventional ideas about women’s role in society), addressing violence against women requires challenging male privilege in sexual matters and social norms of male domination. It is difficult for legislative insiders (members of legislatures and bureaucrats) to take on social change issues without the political support of broader mobilisation. An example of the costs to individuals of taking up these issues isolated from broader support is that of a bureaucrat in Sweden who lost her position when she was unwilling to attribute male violence against women to individual pathologies, such as alcoholism, rather than to gender inequality and widespread tolerance of violent male behaviour.

Third, as suggested earlier, women can more easily get violence against women and other gender issues recognised as priorities in autonomous feminist organisations. When women are organised within broader political institutions, ‘women’s issues’ such as violence against women or equal pay are commonly perceived as being of importance ‘only’ to women, and arguing for the relevance of their concerns in relation to a defined set of priorities is made much more difficult.”

The importance of domestic feminist movements also applies to whether international and regional treaties have much impact (pay attention, post-2015 types):

“International and regional treaties were most influential in countries with strong domestic feminist movements. Feminist activists magnify the effects

of treaties in local contexts by drawing attention to any gaps between ratification and compliance with goals for equality. In the CEDAW process, for example, governments must produce an official report for a UN committee and submit to questioning by committee members, most of whom have also read the critical ‘shadow’ reports written by civil society organisations. Even governments with little intention to comply are held to account for their behaviour in a public international forum. In this process, domestic activists work with international groups and organisations to increase pressure on their national governments, a pattern called the ‘boomerang’ effect.

Treaties give normative leverage to national civil society organisations. At the same time, local activist organisations bring home the value of international and regional treaties. They raise awareness of the rights recognised by the treaties; they use them to train judges, police, and other officials; and they use treaties as tools to lobby legislatures to change discriminatory laws. We found an interactive effect between international norms and autonomous feminist mobilisation, although the effect was more visible in later periods. International norms and autonomous feminist mobilisation magnified the effect of one another. International treaties alter the expectations of domestic actors and strengthen and even spark domestic mobilisation.

In our quantitative analysis, when a strong, autonomous feminist movement was absent, CEDAW ratification seemed to have a barely significant negative effect on the adoption of violence against women policy. This negative relationship may reflect a pattern whereby governments view the ratification of CEDAW as a costless way to enhance their international reputation, while continuing or even stepping up resistance to undertaking real action on violence against women, because they know there will be no pressure by local activists.”

The authors add one important caveat: “Our index does not capture variation in the implementation of policies against violence. In some places, legal reforms took effect immediately, and policy measures were well-funded and executed. In others, reforms have remained mainly ‘on the books’, in the sense of not being fully implemented.”

Please read the GaD article (it’s also a great introduction to the whole topic of VaW), and if you are keen to dig even deeper, you can always go to the American Political Science Review paper on which it is based.

And here’s the maps – state action on VaW, 1975 and 2005

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers