Duncan Green's Blog, page 209

August 13, 2013

Should ODI bite the open access bullet for its journals? Response to last week’s rant on the Academic Spring

paywall. Also, ODI tweeted yesterday to say that the latest issue of its Development Policy Review, (on the effectiveness of transparency and accountability initiatives), which prompted the initial rant is now ungated (August only, so get downloading). Apparently a coincidence – see Nick in the comments.

paywall. Also, ODI tweeted yesterday to say that the latest issue of its Development Policy Review, (on the effectiveness of transparency and accountability initiatives), which prompted the initial rant is now ungated (August only, so get downloading). Apparently a coincidence – see Nick in the comments.Of course I’d like more people to read ODI’s peer-reviewed journals –Development Policy Review and Disasters. I hate the idea of people being shut out. Duncan: that includes you.

Your blog on open access last week – and the associated Twitter conversations – included exhortations to ‘just do it’. But I wish it were as easily done as it is said. As someone who has been working hard to make ODI a leader in embracing the digital age (and other think tanks too, through the WonkComms initiative) it feels uncomfortable to be on the receiving end of barbs about a ‘legacy tail’ or belonging to bygone eras. The reality is that if we could quickly and easily move our journals to full and open access whilst maintaining their research quality and sustainability, we would’ve done it.

What the ‘pay wall’ pays for

ODI’s peer reviewed journals curate brilliant research from around the world. Subscription costs and single article purchases cover the costs of processing, reviewing and publishing this work.

ODI uses its share of income to cover editorial and some administration – and we aim to run at cost. We review hundreds of submissions, co-ordinate a complicated peer review process, copy edit, proof and commission articles. It is not an insubstantial task.

We work with a publisher (Wiley Blackwell) to run our journals because it would be madness not to. They know what they’re doing when it comes to online publication, subscription management, the printing and mailing of hard copies for institutions and individuals – a proportion of whom don’t (and often can’t) access journals online. We wouldn’t be able to do this stuff ourselves very efficiently.

Finding a six-figure sum to cover the full editorial, production and management costs every year is not something anyone can just do. ODI and other organisations running journals cannot reduce costs without impacting quality. The essence of peer-reviewed journals is their guarantee of quality – lose that and you might as well shut them down completely.

sure, but then who pays?

The choices and challenges for academic peer review journals

If we want to move beyond our current levels of open access (brief recap: no or low cost for developing countries; authors paying to allow free access to their articles – also known as ‘gold’ open access and the model recommended by the Finch Report and preferred by DFID; selected articles we open up ourselves), then ODI and other publishing organisations will have to pay directly to make the journals open access. We’ll have to cover all the costs we incur and compensate the publisher for theirs.

So, journals are yet another industry dealing with the effects of ‘digital disruption’: the suffering of newspapers is a well-documented example. Most readers here wouldn’t want to lose The Guardian, but I bet very few have put much money into their coffers recently. It is a pretty fundamental problem of the modern age.

So, we in the journals team at ODI – and the industry more widely – have some big questions to answer. Here are just a few in this very complex debate:

Can we find other funding to cover journals, and if not, what do we make of suggested business models for open access and whether they would work for journals?

How do we best highlight open access options that exist – including the author-archived submissions that Duncan mentioned in his blog?

If the ‘gold’ model of author-paid access becomes the norm and the way we achieve open access long term, how do we ensure those authors without enough funding won’t be priced out of getting their research into our journals?

What do recent changes, such as the University of California Open Access policy announced a few days ago, mean for where the debate is going?

In short, we need to know how we can further open up access to our journals in a way that does not jeopardise the quality of the research they contain, or their financial sustainability.

We’d already been working on this before Duncan and Owen pointed out our journal wasn’t fully open – but there’s still more thinking to do and that is what we’re doing. There are a lot of knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns – but we certainly won’t just be sitting on our hands and dreaming of a world of typewriters.

Reasons to be cheerful

It shouldn’t all be gloom and doom though. With digital disruption comes digital opportunity. I, and my colleagues, want ODI to be at the forefront of the drive towards open access to knowledge. Already, every research output written by an ODI staff member that could go online is there – dating all the way back to 1963 and providing online access to many titles that are now out of print. I think that is pretty impressive.

Perhaps we’re no Julian Assange – but, frankly, we’re hardly the CIA either.

Thanks Nick. I’d quite like to have a poll on this, but am not quite sure what the best questions/options would be. So fire away in the comments section, and I’ll see if anything emerges.

August 12, 2013

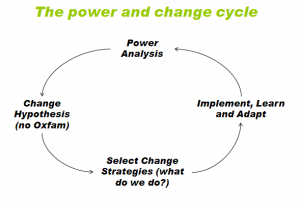

What is a theory of change and how do we use it?

I’m planning to write a paper on this, but thought I’d kick off with a blog and pick your brains for references, suggestions etc. Everyone these days (funders, bosses etc) seems to be demanding a Theory of Change (ToC), although when challenged, many have only the haziest notion of what they mean by it. It’s a great opportunity, but also a risk, if ToCs become so debased that they are no more than logframes on steroids. So in internal conversations, blogs etc I’m gradually fleshing out a description of a ToC. When I ran this past some practical evaluation Oxfamers, they helpfully added a reality check – how to have a ToC conversation with an already existing programme, rather than a blank sheet of paper?

But first the blank sheet of paper. If you’re a regular visitor to this blog, you’ll probably recognize some of this, because it builds on the kinds of questions I ask when trying to understand past change episodes, but throws them forward. Once you’ve decided roughly what you want to work on (and that involves a whole separate piece of analysis), I reckon it’s handy to break down a ToC into four phases, captured in the diagram.

that involves a whole separate piece of analysis), I reckon it’s handy to break down a ToC into four phases, captured in the diagram.

Power Analysis

At their heart, most aspects of development involve a change in power relations (or should do, anyway). Start by asking what is the nature of the redistribution of power involved in the changes we are seeking? Is it primarily about ‘power within’, e.g. helping women acquire the confidence and knowledge to demand their rights; ‘power with’ (collective organization) or ‘power to’ (e.g. supporting CSO advocacy)? There are lots of other ways of slicing the cake, but the point is to have a proper discussion on the nature and (re)distribution of power.

Useful questions include: What is your analysis of the key forces driving/blocking such a change? What economic or political interests are threatened/promoted by the change? Which groups are drivers/blockers/undecided? Is their power formal (eg elected politicians) or informal (traditional leaders, influential individuals)? Is it visible (rules and force) or invisible (in people heads – norms and values) or hidden (behind the scenes influence). Who do the key players listen to (because that may help us decide on our alliance strategy).

Which individuals are likely to play key roles, either as allies or opponents?

Change Hypotheses

On the basis of the power analysis, come up with some hypotheses for how such change might come about. Note that at this point, we are still looking at the process from the outside, rather than discussing our own interventions:

How is the change we are discussing likely to take place? Through existing institutions, or is change likely to require greater disruption, even conflict (e.g. the Arab Spring)?

What alliances (eg between sympathetic officials or politicians, private sector, media, faith leaders or civil society) could drive/block the change?

What would strengthen the good guys and weaken the bad – e.g. research and evidence, pressure from people they listen to (who are they?) or street protest?

Can you foresee any likely ‘critical junctures’: new governments; changes of leadership; election timetables when change is more likely to occur?

Change Strategy

Is that a metaphor or a critical juncture?

Up to now, you have been looking at the issue from the outside. Now it’s time to start thinking about what Oxfam can bring to the party, in the shape of a change strategy (aka a Theory of Action). What should our role be?

As an active player or through supporting local partners? What combination of on-the-ground programming and advocacy might we try?

Can we use Oxfam’s international identity, eg by cross fertilising with experiences from other countries, or international advocacy in support of change?

Can we identify some easy wins, however small, that might inject some momentum into the work?

Are there some identifiable ‘implementation gaps’ we can work on, which are often easier that starting from scratch.

Who are our potential partners – are they ‘usual suspects’ (local civil society organizations and NGOs), ‘unusual suspects’ (private sector bodies, local/national government, faith leaders) or a mixture of both? What could Oxfam’s contribution be eg helping them develop a clearer theory of change; bringing partners together with other actors to build alliances; building particular aspects of their organizational capacity; research support; funding?

How can we make sure we are prepared to take advantage of critical junctures when they occur (whether anticipated or as surprises)?

Implement and Evaluate

Now let’s assume that (shock!) we may not get it 100% right from the outset. How often do we plan to step back and review what we’re doing and consider a change of direction? Who is empowered to ‘press the red button’ and call a time out for reflection if there is a sudden change of circumstances (political unrest, new opportunity etc)? How are we going to collect evidence to inform these reviews (through impact diaries and other methods)? How do we communicate with the donor that our logframe may be changing?

And then round we go again – in this formulation, ToCs are not so much a tick box exercise, or logframes on steroids, as a way of working, involving a much higher level of ongoing political and power analysis and adaptation.

That’s all fine and dandy if you’re starting with a blank sheet of paper, but the reality is usually that you’re arriving to help teams review programmes that are already under way, with lots of partners, activities and history. Current staff may have inherited the work and not been involved in any original ToC discussion (if there was one). How do we need to adapt the above to make it useful?

One way that emerged from the discussion is a kind of reverse engineering/back-testing.

Take your programme’s current activities, along with the content of the programme documents – initial proposal, assumptions, risks and all the rest, and reconstruct the problems you are trying to address and their underlying causes – there are lots of tools available like problem trees, stakeholder mapping etc

Starting from this, revisit your power analysis and come up with a renewed change hypothesis for what you’re working on – including things that

Early change theorists

are not in the project plan!

Based on that change hypothesis, what kind of change strategies (plural) might make sense. Compare these with your current work – what changes might you want to make to your existing plans and activities and budget allocation to reflect that?

Then go into the evaluate and adapt discussion.

Finally, some common traps to avoid:

Death by diagram: a lot of ToC exercises produce a fiendishly complicated diagram with lots of arrows going in all directions. Drawing the diagram can indeed be a really good way to get a group of people’s heads round a change process. But once you’ve drawn it, throw it away, because it will be a scary barrier to thinking for anyone coming new to the work.

It’s all about us: Yes ToCs are supposed to guide our work, but avoid jumping too quickly into ‘what do we do’, rather than spending time analysing the system (power analysis and change hypothesis). You’re almost always likely to be a minor player in a larger drama, so putting ourselves centre stage makes no sense.

A way to make MEL easier: If anything, a good ToC should make monitoring, evaluation and learning more difficult (but more useful). If you’re just trying to come up with some targets to measure progress, you’re probably on the wrong track (e.g. oversimplifying a system, ignoring critical junctures, exaggerating your importance in the system).

Make sense? All comments, suggestions and links welcome, whether on the theory or (perhaps more important) how to use ToCs in practice.

The Growing Anger of the Merely, Barely Middle-Class. Guest post by Sina Odugbemi

I have a guest slot on the World Bank’s governance blog, who repost relevant FP2P pieces. But when I read this great piece from the blog’s

eminence grise

Sina Odugbemi, I decided to reverse the traffic and repost it on FP2P. Sina’s a comms specialist, a novelist, and a very good writer – enjoy.

grise

Sina Odugbemi, I decided to reverse the traffic and repost it on FP2P. Sina’s a comms specialist, a novelist, and a very good writer – enjoy.

The growing militancy of middle class citizens in developing countries is very much in the news these days; and there is a corresponding attempt to understand why so many protest movements in developing countries are now being led by hitherto quiescent middle classes. I have particularly enjoyed analyses by Francis Fukuyama in the Wall Street Journal, President Lula of Brazil in the New York Times and James Surowiecki in the New Yorker. The humble contribution I’d like to make (from my personal experience) is this. To understand the growing anger of middle class citizens in developing countries you have to understand two aspects of the conditions under which they live: the merely bit and the barely bit.

Let’s begin with the merely bit; that is, why in many of these countries when you are merely middle-class you have a problem. To grasp why being merely middle class is a tough situation to be in you have to understand what those they aspire to be like (the well to do in their societies) are able to provide for themselves. Before I left Nigeria in the middle 1990s, the wife of one of our leading politicians came up with the following insight: that to be comfortable you had to become your own local government. And she was right. Here are the things that your local government should provide and it did not and so you had to provide these things for yourself:

Electric power supply (buy a generator and supply it with diesel everyday);

Water supply (dig a good borehole or buy tanker loads of water on a weekly basis from private suppliers);

Education for your kids ( go private );

Security for the home (security guards and the lot);

Healthcare (private doctors, private hospitals, and healthcare secured overseas);

The list goes on but you get the point. That is why in countries like Nigeria to be truly comfortable you have to take on a massive recurrent cost base. The merely middle class are educated; they know enough to understand that these services are basic entitlements of citizens, and to understand that they are not receiving these services because of bad or poor governance. What is more, because they are merely middle class they do not have the option of private provision of essential public services. They simply cannot afford to do so.

This merely middle class predicament struck me forcefully when I moved from Lagos to London. After a few years, I bought a small house in a suburb of London, in a new estate. I remember observing with awe the process by which the local government threw services around the new estate. By the time  the family moved in, it occurred to me that if I were back in Lagos to fund the lifestyle that we had in that tiny house I’d have had to be a multi-millionaire. In London, all I had to do was have a decent enough job, pay my bills, pay my taxes, and I could enjoy the same basic services that the rich friends I envied back in Lagos could afford to provide for themselves. Then throw in affordable consumer credit and you could not only buy a house, you could buy a car or cars, you could buy expensive household durables, pay for all these over time and they became yours.

the family moved in, it occurred to me that if I were back in Lagos to fund the lifestyle that we had in that tiny house I’d have had to be a multi-millionaire. In London, all I had to do was have a decent enough job, pay my bills, pay my taxes, and I could enjoy the same basic services that the rich friends I envied back in Lagos could afford to provide for themselves. Then throw in affordable consumer credit and you could not only buy a house, you could buy a car or cars, you could buy expensive household durables, pay for all these over time and they became yours.

What that means is that in countries where middle class citizens have these basic benefits you do not have to force yourself to earn extraordinary income — by whatever means possible — in order to afford basic comforts. I am not sure many people who work in development realize the extent to which corruption in the public sector (including the private sector players who facilitate it) in many developing countries is driven by the sheer pressure on middle and high ranking civil servants to earn enough money to become local governments unto themselves.

Finally, the barely bit. Many of those in the middle class in developing countries know that their station is not robust, that it won’t take a lot for them to fall back into poverty. Fragility defines their condition. They need and want more security, greater social insurance, some terra firma under their feet. And they know that, properly run, their societies ought to be able to provide these benefits.

All this is why I believe that middle class militancy in developing countries is only just beginning. The emerging and growing middle classes (3.2 billion strong worldwide by 2020, and 4.9 billion by 2030) desperately need good and accountable governance. Governing elites that do not make sure they have it can expect a whole lot of trouble in the years ahead.

August 8, 2013

OK, so how much should charity bosses be paid? Plus your chance to vote

There’s a big fuss going on in the UK right now about CEO pay scales in the big NGOs. With some misgivings, I weighed in with a piece on the Guardian website yesterday. Unfortunately, my weakness for a good one liner was spotted by the sub, who take a throwaway ‘you pay peanuts, you get monkeys’ comment and made it the headline. Wish I hadn’t used the line, but it’s too late now. If I’ve offended any actual interns or volunteers, I apologise. Anyway, here’s the piece, and your chance to vote (right):

website yesterday. Unfortunately, my weakness for a good one liner was spotted by the sub, who take a throwaway ‘you pay peanuts, you get monkeys’ comment and made it the headline. Wish I hadn’t used the line, but it’s too late now. If I’ve offended any actual interns or volunteers, I apologise. Anyway, here’s the piece, and your chance to vote (right):

It’s impossible for anyone working for an aid charity to comment on the current silly season skirmish on salaries without sounding defensive and/or self-serving. But the alternative – keep your head down until it goes away – leaves the field open to the aid bashers, whether of the crass Godfrey Bloom or more intelligent (and non-racist) persuasion. And bashing aid is what this is about. The critics don’t want value for money; they want less money to be spent on aid. I work for Oxfam and think aid and the work of charities is too important to let them have free rein, so although I realize I am on a hiding to nothing, here goes.

What’s the charge? That our bosses are fat cats, trousering donations that supporters and donor governments fondly think are going to relieve poverty. Cue pics of NGO execs in suits and (horror!) smiling (they clearly don’t care about the poor).

And the defence? As former Oxfam CEO Barbara Stocking pointed out on Radio 4 when the story broke, her successor (and my current boss), Mark Goldring, has a big job by any standards: multitasking between running a 700 shop retail chain, managing 5,000 employees and 20,000 volunteers, a £360m budget and ensuring the safety of staff in some of the riskiest places on earth. It doesn’t always work, as Stocking recalled – for a start, people get killed (on her watch, in Afghanistan).

The defences usually also include lots of management blah about salary reviews and benchmarking, and statements like ‘for every £1 donated to Oxfam, 84p goes directly to emergency, development and campaigning work. Just 9p is spent on running costs.” which I fear no-one reads.

The attacks touch on a pretty profound identity crisis for anyone working in aid. Is it a career or a vocation? People working for charities are not saints, but really pretty normal, mainly middle class types. They have partners, kids, many drive cars. We go on holiday (I know, shocking isn’t it?). We worry about getting old, pensions, all that stuff. There is the odd ascetic Mother Teresa type (I met some fantastic ones while working for CAFOD), but by and large we don’t live in convents/monasteries – which means mortgages.

But it’s also a vocation, something that inspires and excites and makes you feel very lucky (and I accept, maybe in some cases, irritatingly self righteous). We don’t need the Daily Mail to tell us there is a tension there – my son recently berated me for taking a salary from Oxfam (though he didn’t seem to connect this to helping get him through college). So the compromise is that our bosses need salaries, but are prepared to take less than they might otherwise. Goldring gets paid £120k and earns it (but I would say that, wouldn’t I?). Although it’s a lot of cash, it’s way below what that level of responsibility would earn in the private sector. Barbara Stocking took a 30% salary cut to become a ‘fat cat’ NGO boss, followed by a 5 year pay freeze.

But whether career or vocation, their work has to be professional – managing these kinds of outfits takes both dedication and skill. Quite rightly, NGOs are under intense pressure to make the most of every penny, and that needs good management. And (the critics don’t talk about this) what would be the alternative to paying this level of salaries? If we ran Oxfam on a volunteer basis, or had a ceiling of say £25,000? If you pay peanuts, you’re pretty likely to get monkeys (albeit well-meaning ones). You don’t have to be a management consultant to suspect that the impact on an organization of such size, complexity and risk could be devastating.

But whether career or vocation, their work has to be professional – managing these kinds of outfits takes both dedication and skill. Quite rightly, NGOs are under intense pressure to make the most of every penny, and that needs good management. And (the critics don’t talk about this) what would be the alternative to paying this level of salaries? If we ran Oxfam on a volunteer basis, or had a ceiling of say £25,000? If you pay peanuts, you’re pretty likely to get monkeys (albeit well-meaning ones). You don’t have to be a management consultant to suspect that the impact on an organization of such size, complexity and risk could be devastating.

Which would suit the aid critics just fine of course – lots of scandals to justify taking a hatchet to the aid budget (any similarity to what’s going on with the NHS is purely coincidental, I’m sure, even if many of the rock throwers are the same).

So that’s my best shot. Yes we get paid. Yes we have careers. And yes we want to change the world for the better. For an organization like Oxfam, the challenge is to find the right balance between duty (keeping salaries relatively low in the context) and effectiveness (understanding that the external market has an effect on the likely talent you are having to attract/retain from within and, more importantly, from outside the sector). Are the bashers really saying such a balance is impossible?

Over to you – vote now (in a non-binding sort of way). Option 2 is Oxfam’s model, option 4 is MSF UK’s.

Why are NGOs and Academics collaborating more?

August is a good month for getting people to step back and take stock – those who are not on holiday have fewer meetings, and so are more relaxed and available for shooting the breeze.

available for shooting the breeze.

And so I found myself at the London International Development Centre this week in one of those periodic soul searchings about how to get NGOs and researchers to work together more and better. Some observations:

I’ve posted before on this topic, but this time there was a sense that things are changing – a number of academics seem to have moved beyond seeing NGOs as just sources of data and dissemination of their findings, and NGOs are more interested in joint research. Lots of stories of deep collaboration, and probably a need to map such examples and see what can be learned from them.

Two new drivers stand out as reasons for this increased level of interest – from the NGO side the demands from funders that they sharpen up on evidence and results; from the academics, the pressure (in the UK anyway) to demonstrate the impact of their work in order to guarantee future research funding through the Research Excellence Framework exercise (which is driving everyone nuts at the moment). There are some pots of money from DFID, ESRC etc backing this up, eg Research for Health in Humanitarian Crises.

These new pressures are additional to pre-existing ones – academics’ personal commitment to change, plus a desire to get access to guinea pigs and data for their theories; NGOs’ desire to have more impact, solve problems and generally understand what the hell is going on.

What emerged for me were some do’s and don’ts:

- Individual bilateral relationships between NGO folk and academics seem more durable and useful. It means you know who you trust and respect in advance, and so can pick up the phone when the need arises. How can we deepen and broaden such networks, given how busy everyone already is? It takes time and investment, but who is going to fund it? ‘No-one’s investing in the air quality of the relationships’.

- Having a bit of cash, and the mental space to try stuff out, as we did with IDS on food prices – an initial £30k collaboration that led to a much bigger DFID-funded joint research programme

- The clearer the joint purpose, the more likely it is to work out (eg Sightsavers’ Trachoma Mapping project, but also, arguably, the various post-2015 collaborations)

- Beyond research, a lot of universities are now exploring training as a way of raising cash and using their expertise in more practical ways. Advocacy training emerged as a possibility (although I’ve never found academic papers on advocacy very convincing.)

What doesn’t work (at least in my experience)

- I’m a bit sceptical of database-type clearing houses – ignores the issue of how to build trust. That said, it depends how they are done. Oxfam has had a good experience with the Research Matching Facility a dating agency where we were able to air a problem (improving methodology for field staff impact assessment) and then interview potential academic partners to help solve it (we went with UEA and are very happy with the partnership)

- Academics trying to park their students with you, usually in August when everyone is on holiday (or in blue-sky sessions like this one). A lot of work needed to align student and NGO needs.

- Grandiose attempts to forge strategic partnerships from scratch (although building on existing links might work).

There were useful suggestions for building deeper ‘evidence literacy’ among NGO staff who currently can fall into two equally unhelpful extremes: ignore evidence in favour of personal preference, or place unwarranted faith in hard numbers, however dodgy their provenance. In a classic example of NGOs’ tendency to be ‘more Catholic than the Pope’ on stuff they don’t really understand, evaluation academics reported that they get loads of NGO demand for numbers, but barely a flicker on process evaluation or realtime accompaniment – the things they are currently interested in exploring. ‘Everyone’s OK with the expensive household survey, but not research for learning.’

There were useful suggestions for building deeper ‘evidence literacy’ among NGO staff who currently can fall into two equally unhelpful extremes: ignore evidence in favour of personal preference, or place unwarranted faith in hard numbers, however dodgy their provenance. In a classic example of NGOs’ tendency to be ‘more Catholic than the Pope’ on stuff they don’t really understand, evaluation academics reported that they get loads of NGO demand for numbers, but barely a flicker on process evaluation or realtime accompaniment – the things they are currently interested in exploring. ‘Everyone’s OK with the expensive household survey, but not research for learning.’

The role of research funders in all this has both positive and negative aspects. On the positive side, things like rapid response funding to enable researchers and NGOs to seize opportunities, but on the negative a resistance to learning approaches that emphasise qualitative methodologies and responding to events (it really messes up your logframe).

Some intriguing suggestions for how to tackle this. Given that DFID is so influenced by the big foundations like Gates and Wellcome, who may be more willing to innovate/ less risk averse (no ferocious backbenchers looking over their shoulders), people reckoned the way to shift thinking may be to target the Foundations first, rather than go straight for Government. Anyone got a decent influencing strategy for ushering Gates along the road to mixed methods, qualitative rigour and learning by doing?

So how do we build the density of relationships? Standard academic conferences are coma-inducing. I’ve been pushing speed dating (no you can’t read anything into that): 10 x 2 minute pitches instead of 1 x 20 minute panel presentation, then plenty of time for people to chat to the ones they were most interested in – a combination of Open Mike and Happy Hour.

Our recent data dive (blog in the works on that from some of the participants) might offer a model for non-data work as well – a brainstorm model, aiming at finding specific answers to real problems (eg what do we do about the climate change driven appearance of frost in Zambia?), generating funding proposals (money talks) or pilot projects. Could funders convene such things, with a promise to look kindly on the results?

aiming at finding specific answers to real problems (eg what do we do about the climate change driven appearance of frost in Zambia?), generating funding proposals (money talks) or pilot projects. Could funders convene such things, with a promise to look kindly on the results?

I cynically wondered if post REF, the normal academic incentive system would kick in and working with NGOs would become frowned on again, but the accies in the room assured me that impact is here to stay, and with it the importance of academics learning to work with partners who can communicate in more accessible terms than they can, (which often means NGOs).

Top candidates for greater collaboration?

- Find better ways to involve students (Masters and/or Doctoral)

- The MEL/evidence/results agenda

- Training (but I’m sceptical about advocacy)

- Longitudinal work – we need to do it, but need help designing, funding and following through

- Realtime accompaniment: embed a researcher with some of our programme work and let them observe the real process of chaos and improvisation, rather than the retrospective coherence of a post hoc evaluation

All in all, a useful exchange and some good materials are available. Check out ELRHA’s Guide to Constructing Effective Partnerships (v practical and user-friendly) and INTRAC’s briefing note, based on its ‘Cracking Collaboration’ initiative.

August 6, 2013

Whatever happened to the Academic Spring? (Or the irony of hiding papers on transparency and accountability behind a paywall)

Is the Academic Spring running out of steam, like its Arab namesake? Last year, there was lots of talk of opening up access to academic papers. Both DFID and the Wellcome Trust took some welcome steps to push the recipients of their research grants to open access. Following the death of Aaron Swartz, who killed himself because he was being prosecuted for conspiring to publish paywalled journal articles, the editor and editorial board of the Journal of Library Administration resigned en masse because they had a “crisis of conscience about publishing in a journal that was not open access”. It seemed that a long overdue revolution was upon us.

papers. Both DFID and the Wellcome Trust took some welcome steps to push the recipients of their research grants to open access. Following the death of Aaron Swartz, who killed himself because he was being prosecuted for conspiring to publish paywalled journal articles, the editor and editorial board of the Journal of Library Administration resigned en masse because they had a “crisis of conscience about publishing in a journal that was not open access”. It seemed that a long overdue revolution was upon us.

Yet this week I had a depressing exchange with the (usually wonderful) ODI about their journal, the Development Policy Review (no link for reasons I’ll explain). The latest issue of DPR covers transparency and accountability initiatives, and (oh the irony!) it is hidden behind a paywall: if I want to read more than the abstract, I have to fill in online forms, pay a few $, then go through the hassle of reclaiming it through Oxfam’s expenses system and anyway, I balk at paying before I know if it’s any good. The result is (and I suspect I am fairly typical) that I move on – I either write to the author to scrounge the piece, find someone who has access eg through a university or, as in this case, read something else instead (it’s not as if development wonks are running out of reading matter).

When I complained via twitter, ODI directed me to an FAQ page on their website which explains:

“ODI does not hold copyright for articles in ODI’s two peer-reviewed journals, Development Policy Review and Disasters, so cannot directly publish these with open access. However, articles can still be accessed through the following methods:

Free access in developing countries. Both journals are available to qualifying institutions for free or low cost through the HINARI, AGORA and OARE initiatives. In 2012, 5,116 institutions were able to access our journals via these initiatives.

Author-funded open access. OnlineOpen is available to authors who wish to make their article freely available to all. This form of open access is mandated by a number of funding organisations, including Research Councils UK and The Wellcome Trust.

Author self-archiving. All authors can publish an electronic version of unpublished articles on their personal website, their employer’s website/repository and on free public servers in the subject area. The final accepted peer reviewed article can be put online in the same ways 24 months following publication in Development Policy Review or Disasters.”

or maybe not

But while some people can therefore access DPR without hassle (if they have the right institutional affiliations), this does not include ‘users outside academic institutions and in the developed world.’ i.e. me, or anyone else working for a northern thinktank, NGO or on their own account.

Does this matter? Well yes, for me – I would quite like to skim the latest DPR, (and will do so next time I’m at the ODI office, and probably try and steal a copy as well). But also more broadly, because it means the journal is cutting out large chunks of potentially influential readership (in this case, a lot of organizations working on transparency and accountability!). The reason for sacrificing so much impact is to cover the costs of peer review and publication by Wiley – but is the trade-off really worth it? Is the review of peers really worth more than the readership of mere mortals? And is Wiley, like most journal publishers, operating a form of highly profitable knowledge rent-seeking?

What to do (apart from whinge on twitter and here)? A few suggestions, in ascending order of bravery:

Ask DFID or other funders of ODI to investigate: if they are paying for the research, it should be open access. If DPR is running at a loss (as one insider tweeter claims), then it is being cross subsidised by other ODI activities, much of which are funded by DFID, so the same argument applies.

Alternatively DFID/ some other funder could work with journals to extend access to non-profits, North and South (or the journals could just decide to do it – if my behaviour is any guide, they wouldn’t lose much revenue and would gain a lot of kudos)

We should all refuse to peer review papers for gated journals (as Owen Barder does) or to link to them in our blogs (hence no link to DPR in this piece)

As I understand the ODI page, they are entirely within their rights to contact DPR authors, suggest they self-publish their final drafts, and then

publish those links on the ODI site. You up for that ODI?

publish those links on the ODI site. You up for that ODI?Or they could try and get a better deal from Wiley – Oxfam hosts the Gender and Development journal and has a deal with its publisher, Routledge, that you can get its content free via the GaD or the Oxfam Policy and Practice websites.

Or someone brave (i.e. not me) could blog the executive summary of each DPR paper and challenge Wiley to sue

Or someone even braver (and who doesn’t mind putting off readers) could publish the whole thing.

So who wants to be the Julian Assange of development research?

By the way, twitterati may have spotted that I originally suggested co-authoring this with transparency guru Owen Barder, but in the end we agreed that co-ranting is just too difficult. He did ask me to include this line though: ‘Publishing academic articles behind paywalls is more than an inconvenience: it limits the spread of knowledge and ideas to already rich and powerful institutions and people. It belongs to an era in which printing and distributing journals was an expensive business. Limiting access to the world’s intellectual resources on those grounds in the digital era is having a legacy tail wag a modern dog.’

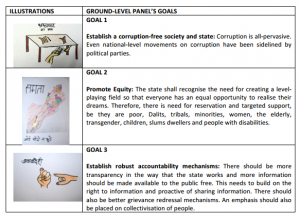

Panels of the Poor: What would poor people do if they were in charge of the post-2015 process?

Many of the attempts to introduce an element of consultation/participation into the post-2015 discussion have been pretty perfunctory ‘clicktivism’. So thanks to Liz Stuart, another Exfamer-gone-to-Save-the-Kids, for sending me something a bit more substantial: 5 day in-depth participatory discussions with small (10-14 people) ‘ground level panels’ in Egypt, Brazil, Uganda and India, culminating in a communiqué to compare with that of the great and good on the ‘High Level Panel’.

with that of the great and good on the ‘High Level Panel’.

Here’s a summary from a post by Catherine Setchell on the Participate website (which links to the four country communiqués, also worth a skim):

The GLP in Egypt (right) proposes a vision of “self-sufficiency” at the country and community level, where Egyptians own the resources needed for development and can secure enough local production of food and other basic items such as water and fuel. They also highlight the importance of “paying more attention to having a high caliber of leaders who can effectively implement our Vision on the ground, which requires good governance.”

The GLP in Brazil wants a “plan for global life” which recognizes the interconnectedness of citizens, the environment and government bodies, where dignity is key. They stress that the current development model is outdated, driven by political and economic interests and puts humanity on a “plan of death.” They recommend seven proposals to achieve the “plan for global life” that include amongst others: “popular education; fair, egalitarian and sustainable forms of production, job creation, and income distribution; building of new alliances; and forms of government and organization that come from the processes and the real necessities of the people.”

The GLP in Uganda called for a vision that “respects the rule of law, human rights and transparency to ensure that services are delivered to everyone equally without any segregation or misappropriation of the national resources.” The panelists reinforced the UN High Level Panel’s “five transformative shifts,” with further recommendations. For instance, panelists agree to putting ‘sustainable development at the core’ but emphasise that “peace and security are critical for achieving sustainable development, and that people should have the opportunity to determine their own development with the necessary capacity and economic resources.”

The GLP in India recommended fifteen goals (see left – keep clicking to expand), including “establish a corruption-free society and state; promote equity; establish robust accountability mechanisms; create institutional spaces to promote people’s participation in local governance and policy-making process; protect the environment; enforce mechanisms to prevent tax evasion by corporates; and end discrimination and stigma.

The GLP in India recommended fifteen goals (see left – keep clicking to expand), including “establish a corruption-free society and state; promote equity; establish robust accountability mechanisms; create institutional spaces to promote people’s participation in local governance and policy-making process; protect the environment; enforce mechanisms to prevent tax evasion by corporates; and end discrimination and stigma.

How do these statements compare with the High Level Panel report’s 12 goals?

Lots of agreement on equality, justice and inclusion and the HLP’s “leave no one behind” message.

The other theme that seems common is better governance and people looking to the state for services. But there’s also a difference – while you don’t hear poor people saying how the private sector should do more to improve their health or education, you do hear that from governments and international institutions.

Overall the ground level panels seemed to give more weight to issues of inclusion, identity and rights.

The HLP was stronger than these ground level reports on gender, water & sanitation, energy and aid (‘sanitation’, ‘energy’ and ‘aid’ don’t warrant a single mention in any of the country communiqués).

Uganda’s communiqué, with its focus on inclusion, sustainable development, jobs, governance and global partnerships was probably the closest to the HLP.

Egypt’s call for self sufficiency didn’t appear anywhere in the HLP deliberations, nor (as far as I’m aware) did India’s concern on alcohol addiction. Or Brazil’s focus on love and connections between people as what makes life worth living. Shame.

I’m not sure what you can read into this exercise. It’s not a revelatory game changer like the World Bank’s fantastic Voices of the Poor project, because it limits the discussion to post-2015 style global commitments, rather than the realities of people’s lives (which is what made VoP so amazing). But for my money it is at least as interesting as opinion polling or all that superficial online ‘tell us what kind of world you want’ nonsense. In contrast, this feels like an honest attempt to have a serious conversation with those who, after all, are supposed to benefit from all this post-2015 talk.

With apologies to the tender sensitivities of Chris Blattman, who after yesterday’s post was moved to tweet ‘ I cry on the inside when I read someone write “post 2015″ in an article title. What a narrow, self important idea of devt’. That feels just a bit unfair given my remorseless slagging off of the whole post-2015 process, but hey, free speech and all that.

August 4, 2013

How will development be financed? The eclipse of aid, and what it means for post-2015

Thanks to Alex Evans for recommending ‘Who Foots the Bill’, a report from the ODI’s Romilly Greenhill and Annalisa Prizzon on trends in development finance. It was published at the end of last year, but somehow I missed it – probably because it is pegged to funding the post-2015 goals, a timesuck discussion I have tried to avoid (without much success).

finance. It was published at the end of last year, but somehow I missed it – probably because it is pegged to funding the post-2015 goals, a timesuck discussion I have tried to avoid (without much success).

But actually its value goes way beyond post2015. Here are some highlights:

Conclusions on Financing for Development:

Developing and emerging economies have been driving global growth over the past decade and it is this, not aid, that has been the main driver of poverty reduction at a global level.

Developing countries have also been expanding domestic tax revenues at a rapid rate, giving much more scope for development to be funded domestically. The average tax ratio rose from 23% of GDP in 2000 to nearly 29% in 2011.

All the main sources of development finance considered in this paper have been expanding rapidly over the past decade. Foreign direct investment inflows and workers’ remittances tripled in nominal terms between 2001 and 2010; philanthropic funding more than tripled between 2003 and 2009. (see first table below for detail)

The relative importance of official aid vis-à-vis other forms of finance has declined. In middle income countries, aid/GDP ratios have nearly halved during the 2000s, whereas tax revenues, FDI and workers’ remittances have all seen an upward trend.

These trends are very uneven across countries, with private cross-border flows heavily concentrated in middle income countries, whereas low-income countries remain much more dependent on aid.

While aid is now under pressure, there has been rapid growth in new ‘aid-like’ forms of development finance, which are not classified as aid but nevertheless have a public interest purpose. This includes South–South cooperation, philanthropy and other private development assistance and climate finance. All these flows have been growing at rapid rates over the past decade and are likely to continue to do so in future.

And some v handy summary stats: The table is a bit hard to read, so the headline is that from 2000-2010, here’s how sources of development finance changed (worth focussing – the numbers are pretty striking):

In Middle Income Countries:

FDI, net inflows: $146bn -> $501bn

Portfolio Equity, net inflows: $14bn -> $130bn

Workers remittances: $76bn -> $301bn

Net official aid: $76bn -> $52bn

In Low Income Countries:

FDI, net inflows: $2,4bn -> $13bn

Portfolio Equity, net inflows: $0bn -> $0bn

Workers remittances: $4bn -> $25bn

Net official aid: $10bn -> $40bn

As for the implications for the post-2015 debate, the paper concludes:

As for the implications for the post-2015 debate, the paper concludes:

‘It will be important for the post-2015 agreement to have an even stronger focus on, and foundation within, country-level leadership and priorities. Country-level targets, or a menu of options that countries can adopt, may be more appropriate than a single global set of targets.’

And

‘The post-2015 goals may be able to be more ambitious, but the limited contribution of aid should be recognised. Domestic tax revenues and cross-border finance flows are now much more important than ODA.’

Which kind of brings us back to the concern I expressed in my paper with Stephen Hale and Matthew Lockwood last year: the MDG process was dominated by global institutions and aid. I totally agree that the post-2015 system needs to focus instead on national processes and non-aid flows, , in order to reflect the almost unrecognizably different landscape of financing for development. But then the discussion should have been designed very differently – it still feels far too much like a revamp of the MDG paradigm, rather than something really new.

August 1, 2013

Development Impact Bonds and Impact Investing – genuine Impact, or snake oil?

The private finance people in development baffle me. They speak a different language; great swirling clouds of jargon, the fuzziest of fuzzwords, all laced with a level of macho market can-do talk that makes me deeply suspicious. Baffled but sceptical – not a good place to be.

And there’s a lot going on at the moment – new ideas, a caravan of conferences and seminars, and a lot of interest from DFID and others. To try and clarify things, I turned to two of our in house finance gurus, Nicholas Colloff and Alan Doran. Both managed somehow to resist my demands for a guest post, so you’ll have to make do with this splicing together by me of emails and conversations.

clarify things, I turned to two of our in house finance gurus, Nicholas Colloff and Alan Doran. Both managed somehow to resist my demands for a guest post, so you’ll have to make do with this splicing together by me of emails and conversations.

There are two broad areas to discuss – one is how to get reliable and affordable financial services directly into the hands of poor people – not just credit (which can be a mixed blessing), but safe savings services and insurance to reduce risks. But I’ll focus here on the second area – raising private capital for broader development purposes.

Let’s start with the indefatigable Center for Global Development, which is pushing its ideas for Development Impact Bonds via a working group and a draft report. The DIB idea is seductive:

‘DIBs would provide upfront funding for development programs by private investors, who would be remunerated by donors or host-country governments—and earn a return—if evidence shows that programs achieve pre-agreed outcomes.’

So it’s both a way to access new sources of capital, and a shift to payment by results that will mollify aid critics of the ‘money down a rathole’ persuasion.

But DIBs get pretty short shrift from Nicholas Colloff:

‘My first thought is that to date the UK has one, yes that is one, social impact bond [the famous Peterborough social impact bond]. The investors in that bond were not representatives of the ‘market’ but primarily foundations and foundations not utilising their endowment money but diverting the money they would have previously used for grants. Since it is new, nobody has, in fact, any idea if it will actually work and if one feature of its working was to attract new money, it has already failed. [But note, there are several other UK bonds now in the launch phase.]

The designer of the bond admitted that he thought they had a useful, if limited function to play. Of the key limits two that are critical are: can you find an intervention whose consequence can clearly demonstrate a reduction in future cost? Recidivism amongst perpetrators of crime (the subject of the Peterborough bond) is a good one because it is relatively easy to measure against known benchmarks and there is reasonable certainty about what works to deliver it. But how many of these ‘easy wins’ can we actually find? From a potential CSO provider’s point of view, the second limit is does civil society have the capacity to deliver against such narrowly defined criteria and would they want to? Would it, in fact, restrict a programme’s ability to respond to the unexpected opportunity and stifle rather than promote innovation? It works if civil society organisations are functioning as narrow service providers, not as advocates of change.

I suspect it is simply a diversion from taking sensible (and political) decisions on who and how to tax and spend the revenue.’

At which point I will move swiftly on, but await the rapier response of Owen Barder or his fellow DIBistas.

The second area I want to cover is the much vaguer concept of ‘impact investing’ (adding the word ‘impact’ to everything is clearly an important aspect of branding. I’m thinking of changing my title to Strategic Impact Adviser (Impact)). Alan Doran filled me in on a recent high level event – under the Impact Investing banner – Government, City, Foundations, World Economic Forum, representatives from 30+ countries including many in global South etc to launch the ‘London Principles’ “a statement of intent and integrity” for policy makers in this area.

The second area I want to cover is the much vaguer concept of ‘impact investing’ (adding the word ‘impact’ to everything is clearly an important aspect of branding. I’m thinking of changing my title to Strategic Impact Adviser (Impact)). Alan Doran filled me in on a recent high level event – under the Impact Investing banner – Government, City, Foundations, World Economic Forum, representatives from 30+ countries including many in global South etc to launch the ‘London Principles’ “a statement of intent and integrity” for policy makers in this area.

Alan was struck by just how fuzzy the term has become. ‘The mission drift is massive. Impact Investing started off as how to make investment a bit softer and more friendly, especially for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). It said to investors you can make money and do good, get a social as well as financial return. But now it’s gone way beyond that: the only common feature is using private capital to achieve policy objectives.‘ Approaches discussed included reinventing public private partnerships to reward outcomes instead of outputs, using social enterprises to provide community services, as well as the development version of social impact bonds

The proponents seem to draw no distinction between agriculture, roads and health and education. No sphere of activity is off limits to private investors. I’m sure I’m influenced by my UK context, where many of the attempts to lure the private sector into public services have bombed (PFI and SERCO are not exactly the best adverts for the wonders of private provision), but this all raises real alarm bells for me. Not only do we have a catalogue of failures in which unscrupulous or incompetent private investors have abused the system and messed up the services, but there’s a deeper underlying problem. Essential services like education and health are a crucial part of building the social contract between citizen and state. They are also vital ways of building a public ethos in society – reducing them to ‘service delivery’ to ‘customers’ ignores all of that.

More generally, there is no recognition of power and self-interest. Alan again: ‘it is assumed that the use of an enterprise approach with better contracts and supervisory structures will result in truly pro-poor outcomes.’ This may sometimes be true, but the optimistic talk of ‘shared values’ seems to overlook the fact that, for better or worse, businesses’ main concern is to make money (often in the short term for a few people) while states’ main concern should be the welfare of their citizens (often in the longer term and for many or all people). This doesn’t mean that government and enterprise are always at odds, but neither should we pretend these fundamental differences do not exist. Can you really draw up such clever contracts that they can prevent such conflicts ever becoming a problem? Incentives, incentives…..

And the evidence base for all this hype is decidedly thin – donors’ usual insistence on ‘show me the results’ seems to fade before the dazzle of the private sector sales pitch. A few examples here and there, but the rest is heavy on spin and light on stats. Which means my sceptical instincts kick in, as I start to wonder if a well-intentioned effort to reform markets for poor people is in practice reverting to breaking open new markets for profit maximization. Little is certain here except that the financial institutions packaging and selling the products (and selling them increasingly hard) and managing the transactions will make some money.

Little is certain here except that the financial institutions packaging and selling the products (and selling them increasingly hard) and managing the transactions will make some money.

Any chance we could just try and sort out tax avoidance and evasion, build a progressive tax system, and focus on improving the quantity, quality and accountability of public services, as well as ensuring that poor people get access to the financial services they need? Wouldn’t that be better than swooning at the feet of the snakeoil sellers? Sorry to be a financial Neanderthal, but that’s just the way I feel.

July 31, 2013

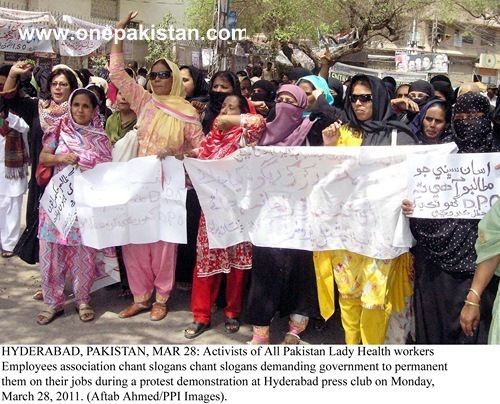

Pakistan’s Lady Health Workers – empowerment + healthcare

Just finished the paper for the UN on where/how governments have managed to empower poor and excluded groups and individuals. Thanks to everyone who suggested links when I blogged the outline back in June. I’ll do a summary when it’s out, but thought I’d share a few of the dozens of case studies dug up by my brilliant research assistant Sophie King (if you’re looking for a top notch politics of development RA, get in touch). First up, a Ros Eyben study on Pakistan’s ‘lady health workers’.

The Lady Health Workers programme (LHWP) provides reproductive healthcare to women by employing almost 100,000 women as community health workers. They provide information, basic services and access to further care. Women are now more visible and mobile within the communities where the LHWs operate. The LHWs receive training, are knowledgeable, earn their own income, and gain respect, challenging gender imbalances in the home and the community.

Empowerment outcomes:

Taking a paid job increases the LHWs’ education through training and work experience, which results in increased decision-making power within

the family and mobility in the community, breaking down caste, class and gender barriers.

the family and mobility in the community, breaking down caste, class and gender barriers.Some LHWs have become leaders in their communities because of the relationships they have had to forge across class and caste barriers There have been shifts within the practice of Purdah in response to negotiations about the LHWs travelling around unaccompanied

Their work has spurred collective action such as resignations among a group of LHWs in one town in reaction to defamatory reports in the local press, and collective protests by LHWs against sexual harassment, including their refusal to participate in an immunisation campaign until a case had been brought against the perpetrator. (See pic and caption for another example)

The women in receipt of the health service itself benefit, particularly as women of child-bearing age are those most restricted from public exposure

Drivers of success:

The initiative builds on existing processes of socio-economic change taking place in Pakistan including rapid urbanization, increased exposure to media, increasing acceptance of female education, many women wanting to work especially following access to education

The initiative is driven by the state, which earns the women the respect of having a ‘government job’.

Government-run television adverts helped women to gain credibility

Limitations/challenges:

Lowest castes have been marginalised by some LHWs in terms of the service and employment opportunities as LHWs, partly because it requires at least the completion of primary education.

Other women or girls in the family often have to make sacrifices to free up the time for LHWs to perform their duties

Programme not as effective in peri-urban areas because they do not have the same level of community cohesion, there is a mix of ethnic groups, LHWs don’t have same ethnic and kinship ties; and because of this, families are more disapproving.

More background: an evaluation in the Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association; LHWs take on child pneumonia and a commentary in the European Journal of Public Health. Any more recent updates welcome.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers