Duncan Green's Blog, page 205

October 8, 2013

So what should Twaweza do differently? How accountability work is evolving

Yesterday I sketched out the theory of change and initial findings on the first four years of work by an extraordinary East African NGO, Twaweza. Today I’ll move on to what some NGO people (but thankfully no-one in Dar es Salaam last week) insist on calling ‘the learnings’ about the flaws and gaps in its original theory of change (described in yesterday’s post).

First, there’s a big ‘black box’ containing Twaweza’s rather large assumption that giving people information (eg about failing education systems), would lead to them taking action to change things. What issues in the black box determine whether this is true or not?

Evan Lieberman (one of Twaweza’s many evaluators, from Princeton University) called this the ’secret sauce’ – the miracle (see much-used cartoon)  that links information to action. His team had come up with a smart attempt to identify some of the sauce’s ingredients – conditions for a →b:

that links information to action. His team had come up with a smart attempt to identify some of the sauce’s ingredients – conditions for a →b:

Do I understand the info? →Is it new info? →Do I care? →Do I think that it is my responsibility to do something about it? →Do I have the skills to make a difference? →Do I have the sense of efficacy to think that my efforts will have an impact? →Are the kinds of actions I am inspired to take different from what I am already doing? →Do I believe my own individual action will have an impact? →Do I expect fellow community members to join me in taking action? Evan argued that only if the answer to all of these is yes, will the black box indeed turn information into action.

Actually it’s worse than that – they missed some pretty big ones (‘do I have the time to do this, on top of everything else?’ ‘Will I run any personal risks if I do this?’) It’s a hell of an intimidating set of conditions and, as was pointed out, the danger is that accountability proponents will just latch onto one of the steps, then wonder why nothing is popping out at the outcome end.

Second, thinking has moved on from Twaweza’s rather Manichean division of politics into the left and right hand sides of informal v formal power (see table), with change to be achieved by the left hand side coming together and demanding action from a nefarious and/or indifferent right hand side. These days, research by groups like the Africa Power and Politics Programme and Matt Andrews argues that both demand side (build the citizens) and supply side (build the state) have failed. What works, they think, is collective problem solving, bringing together citizens, states and anyone else with skin in the game, to build trust and find solutions. People on the ground, like Goreti Nakabugo, Twaweza’s Uganda coordinator, get this: ‘we know we need buy-in from the government, officials, local politicians. We are brokering relationships with them on a daily basis’.

Not only that, but in practice, even differentiating between citizen and state can be problematic – neither category is a monolith, and in some cases, the most active citizens are themselves state employees, members of public trade unions etc.

Not only that, but in practice, even differentiating between citizen and state can be problematic – neither category is a monolith, and in some cases, the most active citizens are themselves state employees, members of public trade unions etc.

Third, Twaweza needs to decide whether all citizen action is equally desirable and if not, what kind it wants to promote. Convince a parent that their child’s school is failing and unless they think their protests are likely to get a hearing, they are probably more likely to try and move their kid to a private school than join a social movement to ‘change the system’. Is that a desirable exercise in citizen agency or a systemically disastrous rush for the exit?

Another axis is that of individual v collective action – does Twaweza see them as equal in value or is collective action in some way preferable in terms of building the voice of marginalized groups? Again, not clear from the theory of change. Maybe Twaweza should map the results of its current work on a 2×2 diagram (individual → collective; public → private) and see if it’s happy with the result.

Fourth, envisaging change as taking place in an information ecosystem sounds great, but is it just a metaphor or a real description? According to Rakesh, Twaweza hoped to ‘bend’ the ecosystem towards becoming a driver of citizen action, but ‘to seriously achieve what we had imagined would have required such deep density and high level of coordination and sequencing it would have been akin to playing God.’ The goal is now to try to understand the ecosystem better, and find some less hubristic way of influencing it. A command and control approach was never going to work, so why not  pull in some actual ecologists to suggest how to influence real-life ecosystems, and see what could carry across into work on accountability?

pull in some actual ecologists to suggest how to influence real-life ecosystems, and see what could carry across into work on accountability?

Fifth, the evaluators came back with some serious questions about irrational optimism over the magic powers of ICT. Eg broadcasting messages to the public via SMS doesn’t work because people only trust the content if they receive it from someone they know. Otherwise they just think ‘spam’ and hit the delete button.

Sixth, an overarching lesson of all this, as so often, is that the system exhibits much more inertia than we think. Things just don’t shift that quickly or easily, despite the best efforts of smart and determined campaigners. But they do (eventually) shift. And presumably some things shift more quickly than others – my guess would be that norms and attitudes (eg over whether it’s worth taking public action to improve your kid’s schooling) evolve much more slowly than public policy. So is it any wonder that the evaluations showed more impact on the latter?

Finally, it is notable that among the partners in the five channels that Twaweza identified as of mass relevance to poor people (mobile phones, media, consumer goods, teachers and religion), only Twaweza’s media partnerships have really worked out. Is that because the media and NGOs are more aligned in terms of language, interests, politics? Would Twaweza need different approaches (change of language, longer timescale) before it can work successfully in the other channels? This is very important – I was a bit disappointed to see all the fine words boil down to doing more and better media work rather than, say, forging real alliances with faith communities.

Tomorrow, I get onto an underlying tension in the Twaweza discussion – the war for Rakesh’s soul (and Twaweza’s future) between the hunger for certainty and the realities of complexity.

October 7, 2013

Twaweza, one of the world’s cutting edge accountability NGOs

Rakesh Rajani is an extraordinary man, a brilliant, passionate Asian Tanzanian with bottle-stopper glasses and a silver tongue. The persuasive  eloquence may stem from his teenage years as an evangelical preacher, but these days he weaves his spells to promote transparency, active citizenship and the work of Twaweza, the organization he founded in 2009.

eloquence may stem from his teenage years as an evangelical preacher, but these days he weaves his spells to promote transparency, active citizenship and the work of Twaweza, the organization he founded in 2009.

Rakesh is a classic example of a hybrid social movement leader, bridging the divide between policy makers and poor people, equally at ease in the homes and meetings of poor villagers and the corridors of the White House or the Googleplex (both of whom he has advised).

Last week I spent two days at a review of Twaweza’s work; an intense, exhausting, intellectually tumultuous couple of days with the smartest group of people I’ve met in a long time. Not sure how many posts it will take to do justice to it, but here goes.

First, some background on Twaweza. Its name means ‘we can make it happen’ in Swahili. It is a ‘ten year citizen-centered initiative, focusing on large-scale change in East Africa.’ Its strategy was so brilliant and ahead of its time that I nearly blogged on it just as a piece of thinking. Here’s my feeble attempt to summarize it:

The problem: a combination of poor quality services in East Africa . Twaweza’s groundbreaking Uwezo assessment shows that only 3 out of 10 children can do basic literacy and numeracy across East Africa; and worse, only 6% of secondary students got a pass equivalent in the 4th year exams last year, despite families making huge sacrifices to keep their kids in school. Plus deep public disillusionment – across the region, those on the sharp end feel there’s no point in complaining because no-one in authority will listen.

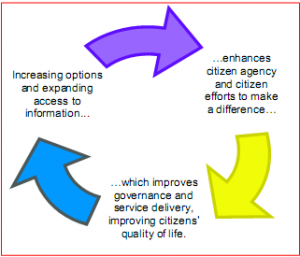

Twaweza’s original Theory of Change (I’ll get onto their self-critique later): A pretty crude and linear model of access to information → citizen action → state response → improved outcomes.

Twaweza’s original Theory of Change (I’ll get onto their self-critique later): A pretty crude and linear model of access to information → citizen action → state response → improved outcomes.

But the truly innovative bit was how Twaweza conceptualized changing this state of affairs. It identified five vibrant networks that loom large in the lives of most poor East Africans. These were:

Religion: a key organizing principle in people’s lives

Mass media: privatized, liberalized and booming – there are hundreds of radio stations. TV is important as a public event (people go to public spaces with TVs to watch the news, premiership soccer etc). Newspapers are crucial to elites, and provide content for TV and radio.

Mobile phones: enough said

Teachers: the expansion of basic education means teachers are ever-more ubiquitous. They are often not that great as teachers, but have a big role in the ‘liminal space’ (Rakesh) between communities and the wider world. Villagers go to their teachers with ‘How do I fill in this form/ use this new phone?.

Fast moving consumer goods: every community has a kiosk with basic goods – a big deal compared to a past of rationing, queues and shortages. They are also social convening point (especially important for women): where you exchange information on the day to day struggles for survival, networks.

Twaweza saw this combination of channels as the heart of a potential ecosystem of change. Get enough information to people, simultaneously, via as many of these channels as possible, both on the problems of service provision, and the case for citizen action, and bingo. Rather than create little projects of its own, the ambition was to ‘ride the wave’, seeking partners already working in these channels who could reach 2 million or more people. The website has some nice examples – providing social content for top TV soap operas or radio satire, or advertising on the back page of 40 million school notebooks, challenging – large scale innovation.

This level of ambition is matched by a deep commitment to measuring results, experimentation and public transparency. No wonder Twaweza has become something of a donor darling with an $8m a year budget.

That was then (2009), this is now. How’s it all going? Last week’s seminar was a combination of preliminary findings from some large scale evaluations, and a wider discussion on how Twaweza’s theory of change is withstanding the passage of time.

and a wider discussion on how Twaweza’s theory of change is withstanding the passage of time.

The initial evaluation findings are not good. None of the large scale evaluations led by eminent academics from around the world has yet uncovered evidence that Twaweza’s information is registering with citizens on any scale, still less triggering increased citizen action. One of the evaluators (echoed by Rakesh) called it a ‘bucket of cold water’ on the original concept. Finding partners able to match Twaweza’s ambitions has proved difficult – they have some 18 who are doing the business, most of them media-related. But another 40 or so are problematic, draining staff time and energy that could be spent on more exciting stuff.

By contrast, when it comes to public policy, there are some notable achievements – Twaweza’s Uwezo education campaign has played a major part in shifting attention in Kenya and Tanzania from enrolment to outcomes (something also picked up in the post-2015 high level panel report), not least by publishing the results of its annual tests on some 300,000 (!) kids. Twaweza has a high media profile as a credible source of research and analysis.

Given such findings, it would be all too easy to wheel out the classic NGO responses to null results – it needs more time, you’ve measured the wrong thing (shoot the messenger), we achieved lots of stuff that wasn’t in the original plan, events got in the way etc etc. And actually, some of these responses in this case would be quite justifiable. But Twaweza seems to positively relish donning the hair shirt and beating itself up. To find out the results of two days of self flagellation, you’ll have to come back tomorrow.

And here’s a nice 1 minute Twaweza video giving a flavour of the behavioural changes it seeks to trigger.

What’s the link between human rights and cooking, cleaning and caring and why does it matter?

Thalia Kidder

, Oxfam’s Senior Adviser on Women’s Economic Rights, welcomes a new UN report that links unpaid care work, poverty, inequality and women’s rights

People working on violations of human rights often find it a stretch to put housework, childcare and fetching water and fuelwood alongside evictions from ancestral lands, rape or unjustly emprisoning and torturing activists.

Likewise, for those of us talking about care work as an obstacle to women benefitting from local development projects, Human Rights Conventions seem rather distant and irrelevant. A Nigerian colleague commented that it was difficult to talk to women in villages about carrying water as a human rights violation when there’s no school, no decent work, widespread violence, and “women think the government is doing them a favour if they get any services at all”.

So a big welcome for a new UN report by Magdalena Sepulveda, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, which starts with an unequivocal statement. “Unpaid care work [is] a major human rights issue.” On women caregivers living in poverty, she adds “heavy and unequal care responsibilities are a major barrier…to women’s enjoyment of human rights, and in many cases, condemn women to poverty.” She’s presenting the report at the 68th session of the United Nations General Assembly, and today at the Mary Ward House in London.

Sepulveda and her researcher Kate Donald have clearly read a lot in the last four months, and they bring together a mountain of evidence; all that housework is overwhelming and is unequal. Women and girls do 71% of water collection in sub-Saharan Africa, and spend 40 billion hours a year collecting water, equivalent to a year’s worth of France’s workforce (UNDP 2009). In DRC women with traditional stoves worked up to 52 hours more per week (collecting fuel and cooking time) than if they had a fuel efficient stove (André Bourque; Oxfam 2011).

Next, there is a lot of evidence to show how the arduousness of doing all this care work without services and inequality by gender, race, class etc does indeed violate human rights. These violations include rights to education, decent work, social security and health (79% of unpaid carers in Scotland experience mental ill-health as a result of caring – Scottish Human Rights Commission 2012). And perhaps less obviously, the ‘right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress’, the ’right to participation’, and the ‘right to rest and leisure’.

Next, there is a lot of evidence to show how the arduousness of doing all this care work without services and inequality by gender, race, class etc does indeed violate human rights. These violations include rights to education, decent work, social security and health (79% of unpaid carers in Scotland experience mental ill-health as a result of caring – Scottish Human Rights Commission 2012). And perhaps less obviously, the ‘right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress’, the ’right to participation’, and the ‘right to rest and leisure’.

As always, the question arises, ‘so what?’. One of the big pluses of the human rights framework is that states have the obligation to do something about massive violations. Sepulveda lists some of the measures required – physical infrastructure, services,taxes, schools and employment, non-discrimination in laws and policies, and “assessing the impact of economic and social policies on the intensity and distribution of unpaid care work in the household.” (p. 39).

And here is where (for a development staffer) the message went beyond the elite world of human rights lawyers and conventions. As I read on, it became clear that if society recognised unpaid care work as work – valuable work, significant work, a major occupation – then our policies would be very different. Our government budgets would be different, and our strategies for development would be different.

In case that all sounds a bit vague, the Report fleshes it out with some concrete suggestions: low-cost electricity, solar and water energy for domestic  purposes, extended school day programmes, high-quality childcare, palliative care; tax systems that promote equal sharing of both paid and unpaid care between women and men; facilitating, incentivizing and supporting men’s caring including equal rights to employment leave as parents; equality in labour laws covering the the length of the working day, social security and leave time, including for part-time, atypical and informally employed workers.

purposes, extended school day programmes, high-quality childcare, palliative care; tax systems that promote equal sharing of both paid and unpaid care between women and men; facilitating, incentivizing and supporting men’s caring including equal rights to employment leave as parents; equality in labour laws covering the the length of the working day, social security and leave time, including for part-time, atypical and informally employed workers.

Sepulveda criticises processes that often “lack[s] women’s perspective in policy-making on agriculture, water and food management” (p. 29); policy-making is misinformed as those doing intensive caring aren’t present. Actors should “invest in development and distribution of affordable technology to reduce the intensity and duration of women’s work” (p. 27). Oxfam’s Rapid Care Analysis in agriculture has likewise prompted inclusion of childcare services, water, stoves and ‘awareness raising with men’ as part of good enterprise development strategies, as well as for the health and leadership of women.

So the report is worth reading even if you’re not a human rights lawyer, and either way, perhaps it’ll change a few minds about the wider significance of carrying water, cooking and taking care of the kids.

A few links: Over the past two years ActionAid has been implementing a programme on unpaid care work in 10 countries across Africa and Asia.

As part of its work on women’s economic leadership, Oxfam’s agricultural markets programmes have addressed care work (see this video of Azeri women farmers). Oxfam’s Rapid Care Analysis, designed to integrate easily into existing tools on livelihoods, food security or vulnerability, shows how care impacts on women’s time, health or mobility, and identifies practical interventions and advocacy to reduce and redistribute care.

As part of its work on women’s economic leadership, Oxfam’s agricultural markets programmes have addressed care work (see this video of Azeri women farmers). Oxfam’s Rapid Care Analysis, designed to integrate easily into existing tools on livelihoods, food security or vulnerability, shows how care impacts on women’s time, health or mobility, and identifies practical interventions and advocacy to reduce and redistribute care.

IDS is leading a research and advocacy programme on unpaid care that explores the political economy conditions under which policy actors either recognise or ignore the significance of unpaid care in 6 countries (Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nepal, Nigeria, Uganda and Kenya). Having conducted a major review of over 250 social protection and early childhood development policies in 144 countries, IDS has released this 4 minute animation outlining their main messages on the links between policy and the rights of care providers.

October 3, 2013

Unpacking India’s historic new Food Security law

M. Kumaran, Oxfam India’s food justice program coordinator, unpacks India’s historic new Food Security Act

On 2nd September, 2013 the Indian Parliament ushered in a new legally-enforceable regime in India’s struggle against hunger through the historic National Food Security Act 2013. The Act injects more resources into India’s food and nutrition programmes and establishes an independent grievance redress system for fixing gaps in implementation. However the Act is far from being a comprehensive piece of legislation, with many policy loopholes.

According to the 2012 Global Hunger Index Report, despite high growth, hunger in India did not decline between 1996 and 2011. The hunger and malnutrition (HUNGaMA) report 2011, released by the Prime Minister, revealed that 42 per cent children in India were underweight and nearly 59 per cent were stunted. With high levels of acute malnutrition almost three children die every minute in India.

Even before the new Act, the government had introduced a wide range of food and nutrition schemes. These currently cover around 140 million children under school feeding programme, provide supplementary nutrition to 91 million pregnant/lactating women and children (0-6 yrs), cover another 10.5 million women with cash transfers for maternity benefits and assure 35 kg food grains every month at a fixed price to around 1.21 billion people (including below poverty line households who got food grains at a subsidized price).

That level of government activity has needed defending. In the last two decades, civic action by the Right to Food Campaign, along with judicial interventions have effectively blocked the efforts of a strong anti-food subsidy lobby to dismantle these programmes. Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and Mid-day Meals (hot cooked meals) for school children were universalised, and attempts to further reduce coverage of the Public Distribution System (PDS) and replace it with cash transfers were defeated.

That level of government activity has needed defending. In the last two decades, civic action by the Right to Food Campaign, along with judicial interventions have effectively blocked the efforts of a strong anti-food subsidy lobby to dismantle these programmes. Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and Mid-day Meals (hot cooked meals) for school children were universalised, and attempts to further reduce coverage of the Public Distribution System (PDS) and replace it with cash transfers were defeated.

The new Act is a further significant victory. It uses existing social security programmes as a means to deliver legal entitlements, legally protecting the necessary resource allocation. In certain cases, the Act also expands coverage and entitlements. It increases the PDS coverage with provision of subsidised food grains at a lower cost, for an additional 260 million people. The Act also reduces the price of rice to Rs 3 (5 US cents), wheat to Rs 2 (3 US cents), and millets to Rs 1 (1.5 US cents), per kg for an additional 688 million people. Similarly the maternity benefit coverage is universalised and all women will be legally eligible for maternity benefits up to Rs. 6000 (US$96), unless they are already covered.

The Act envisions an “empowerment revolution” whereby citizens can assert their legally guaranteed food rights. Currently food and nutrition entitlements do not reach a large number of eligible beneficiaries. For instance, out of 86 tonnes of food grains that is supposed to annually reach poor people through a PDS shop, only 39 tonnes actually gets there, according to the Planning Commission. Similarly, out of 46 per cent malnourished children reported by the National Family Health Survey only 8 per cent are actually identified by the ICDS. To empower the beneficiaries, the Act makes provision for a district level Grievance Redressal Officer (DGRO) and State Food Commissions, with powers to hear complaints and take action against erring officials.

Positively discriminating in favour of women, the Act considers the eldest woman in the house as the household head for receiving the PDS entitlement cards.

cards.

Despite all this, on many others counts, the Act remains a missed opportunity. Firstly, it fails to take a comprehensive “food for all” approach. Despite well documented problems with targeting in the PDS, it has not replaced it with universal coverage by subsidized food-grains. As a result, the Act will exclude many poor and vulnerable groups, such as unorganised urban workers, out-of-school children, poor children enrolled in private schools, migrant workers, homeless and destitute people. By not including pulses and edible oils in the PDS, the Act fails to provide a good nutritional balance.

Another miss for the Act has been its failure to take the grievance redressal system beyond the district level, to the lowest governance units, the block or gram panchayat level. The system is largely toothless, without power to take punitive actions against erring officials, beyond imposing a meager fine of Rs. 5000 (US$80).

Despite the well-established role of subsidised food grains in providing protection against food price inflation and intra-household discrimination, the act encourages cash transfers.

Finally, it misses the chance to support poor producers by procuring locally grown food grains for PDS, ICDS and mid-day-meals from nearby (10-20 km distance) small and marginal farms.

Many of these limitations are a direct result of the government’s attempt to contain food subsidies. Media attention was captured by critics who orchestrated a debate on the Act’s ‘affordability’ that was misleading. These critics fail to see that the economic benefit from reduced child malnutrition in the long run will far surpass the cost of of food subsidies. Moreover careful calculation by experts shows that the food subsidy will only increase by 18 per cent due to the new Act. Even after the food bill, the subsidy levels for social protection as a proportion of GDP in India will remain very low by international standards. While the financial cost of the Act stands at an estimated Rs 1.25 trillion (US$20bn), the revenue foregone due to exemptions/ deductions/ incentives in the central tax system for big corporate houses or highly salaried professionals was Rs 5.73 trillion (US$92 billion) in 2012-13. Given these facts, it is laudable that the opposition parties and the ruling coalition have disregarded these “affordability worries” in debates on the bill and focused more on its limitations.

Many of these limitations are a direct result of the government’s attempt to contain food subsidies. Media attention was captured by critics who orchestrated a debate on the Act’s ‘affordability’ that was misleading. These critics fail to see that the economic benefit from reduced child malnutrition in the long run will far surpass the cost of of food subsidies. Moreover careful calculation by experts shows that the food subsidy will only increase by 18 per cent due to the new Act. Even after the food bill, the subsidy levels for social protection as a proportion of GDP in India will remain very low by international standards. While the financial cost of the Act stands at an estimated Rs 1.25 trillion (US$20bn), the revenue foregone due to exemptions/ deductions/ incentives in the central tax system for big corporate houses or highly salaried professionals was Rs 5.73 trillion (US$92 billion) in 2012-13. Given these facts, it is laudable that the opposition parties and the ruling coalition have disregarded these “affordability worries” in debates on the bill and focused more on its limitations.

Now that the legislation is being rolled out, it’s time for civil society to mobilise people at the grassroots level to monitor its implementation and try and plug the policy loopholes.

Another major challenge will be to ensure that the Government’s strategy of fulfilling food rights through direct food grain delivery does not mean it is able to shirk its wider responsibility for tackling the structural drivers of India’s poverty and inequality. A broad-based mobilisation of agricultural labourers and small holders needs to ensure that the Act does not end up merely as a tool to clean up the mess generated by the current growth model, which is pursuing policies that adversely affect small and marginal farmers.

October 2, 2013

What does your project plan most resemble – baking a cake, landing a rocket on the moon, or raising a child?

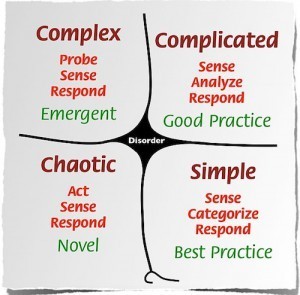

One of the main obstacles to having a decent conversation about the implications of complex systems for how we ‘do’ development

(donorship, programming, advocacy, campaigns etc) is the language itself. Complexity geeks may get a kick out of saying ‘it’s all complex/context specific etc etc’, but more normal/practical people tend to find such language offputting and disempowering. Often, they don’t want to revel in the complexity of the world, they want to know how to do their jobs better. Alan Hudson observed a while back that the most useful discussions on complexity are often those that completely avoid using the word ‘complex’.

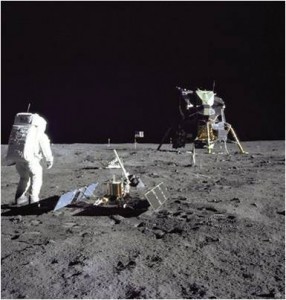

So I’m always on the lookout for good metaphors or other ways to convey complexity in more practical ways – step forward in our recent double act in Australia. Chris, who’s been banging on about complexity for decades, divides up ways of ‘doing development’ into three broad categories: baking a cake, landing a rocket on the moon, and raising a child.

Baking a Cake: want to make a cake? Then find a recipe, buy the ingredients, mix, bake and voila! Some cakes are better than others (mine don’t look anything like this one), but the basic approach is fixed, replicable and reasonably reliable. In complexity thinking, this corresponds to a simple system and is the imaginary world of the typical NGO project plan. There are some situations where this is the

right approach – distributing emergency aid, vaccinations, bed nets, cataract operations (although even these are never entirely simple), but in the increasingly important messier areas of development – governance, accountability, livelihoods – seeking the right recipes is often either a waste of time or counterproductive.

Landing a rocket on the moon: If you can assemble enough smart people, cash and computer power you can build, fire and land the rocket, and even bring it back again. You need to design the plan from scratch (no recipe here), but if you know the laws of physics, advanced engineering etc you can be pretty confident of success. I’m not sure NGOs do much of this kind of thing – sounds more like a giant infrastructure project funded by the World Bank or DFID. In complexity thinking, this corresponds to a complicated system.

Raising a child: This is what a complex system feels like. If you approach impending parenthood by designing an enormous project plan setting out your activities, assumptions, outputs and outcomes for the next twenty years, the chances are you will be a rubbish parent and your kid might quite possibly end up as some kind of psycho. Raising a child is reflexive, iterative, adapts to the evolving nature of the child and their relationships with you and others, and is most definitely devoid of any ‘right way’ of doing things (despite all those ‘magic bullet’ guides preying on the insecurity of new parents). (Come to think of it, maybe that’s why I have always instinctively

phrases like ‘I am doing parenting/childcare this afternoon’, which suggest some kind of blueprint activity). What really helps parents is often advice and reassurance from people who’ve been through it themselves – ‘mentoring’ in aid world. Working in complex systems requires exactly the same kind of iterative, reflexive and agile approach (wonder what the aid equivalent of ‘I’m knackered and need a cup of tea, why not just stick a video on’ is?). And yes, I’m aware that the comparison with parent-child relationships has potential unfortunate colonial/paternalist echoes, but that is most definitely not the point.

The problem in the aid business is of course that while most project plans follow the cake-baking model, many real life situations are much closer to the complex unpredictability of raising a child. If true, we need to think, talk and act very differently.

Everywhere I’ve tried this out, I get nods of recognition – can you suggest any improvements? Also, any ideas for kinds of aid work that fit the fourth quadrant in the Cynefin framework – chaos?

October 1, 2013

What Can Vietnam’s excellent schools teach us about education quality and equality?

This guest post comes from

Jo Boyden,

Director of the Young Lives study at Oxford University’s Department of International Development.

Alongside economic growth, the huge dash for education is fuelling massive expectations among the swelling youth populations in developing countries. Dramatic expansion of education systems over the past few decades has been accompanied by an international push for universal access through major initiatives such as Education For All and the Millennium Development Goals. Now the latest 3ie Working Paper, concludes that development interventions are succeeding in getting more children into school and keeping them there.

Even so our latest findings, from Oxford University’s large-scale Young Lives study – which is following 12,000 children in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam over 15 years – show that sending children to school and committing to keep them there involves huge challenges for countless poor families. It often means taking children away from work that boosts fragile family incomes and also involves significant costs for textbooks, uniforms and transport. But despite this, parents and children are prepared to make enormous sacrifices for children to attend, many families selling livestock or land or getting into serious debt to cope with the expense, particularly of the burgeoning low-fee private sector.

Families are willing to do this because they believe that schooling offers a way out of poverty, the drudgery of labour-intensive occupations like herding and farming, and a means of releasing future generations from the hardship and suffering endured by their parents. As one Peruvian farmer told us, “I … walk in the fields in sandals. At least he will have shoes if he gets a good head with education”, and a woman recalled her daughter saying, “We’re not going to suffer like this in the mud… it’s better that I go and study.”

Most families in our study are very poor and many of the parents have very little or no education themselves. Despite this, our surveys have found half the parents of 8-year-olds in Ethiopia, Peru and Vietnam want their child to complete university.

But are their hopes warranted? Across the developing world, school teaching standards are extremely uneven and many pupils fall far behind the level of learning expected for their age.

The 2012 study by India’s ASER research centre found 47% of Indian grade 5 pupils unable to subtract even two-digit numbers, and more than half of grade 5 children in rural schools unable to read a test designed for pupils in grade 2.

Probably not a Vietnamese student....

By contrast, Vietnam is a beacon of hope. Young Lives recent Vietnam School Survey found that pupil performance in Vietnam (where per capita GDP is broadly similar to that of India) is truly exceptional. Around 19 out of every 20 ten year-olds can add four-digit numbers; 85% can subtract fractions and 81% are able to find X in a simple equation.

The education system in Vietnam is relatively equitable and this means that poorer children can expect a decent quality of schooling. Our data show children from disadvantaged as well as average or better-off backgrounds make good progress in classes taught by motivated and well-trained teachers. Teachers are evaluated six or more times a year and they assess their pupils regularly. Few teachers, including those working in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, perform poorly in assessments of their knowledge for teaching grade 5. Most classrooms have electricity and more than 96% of pupils have core textbooks for their own use. Both teacher and student absenteeism averaged only two days over our study period of 8 months.

Some of the reasons for higher learning levels in Vietnam are cultural and historical. Parental expectations are typically high and the Confucian culture may be seen as emphasising hard work over natural ability. But the school system, which emphasises minimum standards and pays particular attention to disadvantaged areas, is very important too. The centralised curriculum, text-books and teacher training in Vietnam mean that standards across the country relate to common goals and norms. The demands of the curriculum are within reach of most pupils, and the system motivates teachers to ensure that the majority of their class reaches required standards by the time they finish primary school.

Vietnam has very few private schools so families expect the state system to deliver a good education for all children. And the government sets a benchmark for the resources and facilities it expects every school to provide. This contrasts with many developing countries where there is still a legacy of education systems that were designed to serve a small bureaucratic elite. Very often the curriculum is too difficult for most pupils so only a few reach the required standard and the less advantaged majority are left behind at the starting blocks.

Vietnam faces its own challenges, but we found a system where teacher commitment is absolutely fundamental and where there is an assumption of equity across the board. Some things about the Vietnamese schooling system are transferrable while others may not be replicable in contexts where social and cultural conditions are very different. But governments and their partners in other countries can learn from Vietnam’s common minimum

standards and appropriate curriculum.

Teachers in Vietnam are evaluated regularly, and are held accountable through the commune system rather than by the risk of being fired if their performance is unsatisfactory. Low levels of effort and commitment from teacher is a huge problem in many other systems where incentives are low and accountability is weak, often reflected in high absenteeism. If they want their investment in education to deliver the goods, governments need to find appropriate ways of making teachers more accountable and donors can play a strong role in providing assistance to support this. It would involve proper monitoring systems and much more parental involvement, enabling communities to have greater scrutiny over what’s going on in their schools.

Families everywhere are investing huge hope in education as a route out of poverty for the next generation and they are making enormous sacrifices to send their kids to school. But while the recent ‘MDG push’ means that millions of children are now going to school, until education systems are made more accountable, many kids will never learn enough to transform their future prospects.

September 30, 2013

Why on earth is Barclays (still) cutting the remittance lifeline to Somalia?

Oxfam’s tame ex-banker

Will Martindale

wonders what on earth Barclays is up to in cutting the remittance lifeline to Somalia

“I can skype my mum, and see her, and watch her go hungry, fall ill. But they’re saying I can’t transfer money for food or to see a doctor. How can that be?”

Istarlin lives in South London. She’s one of thousands of Somali migrants around the world who send approximately $1.3 billion every year to friends and families at home. Generosity on this scale is laudable. It’s far more money than Somalia receives in humanitarian aid.

Barclays is the only remaining major bank in the UK still providing this service to Somalia. But earlier in the year, due to a perceived increase in risk, it published plans to close all Somali money transfer accounts. The deadline was yesterday.

Over 100,000 signatories, an Olympic double gold medallist and Somali community groups joined together in an unlikely coalition. They were up against Barclays and the Treasury. The call was clear. Barclays needs to extend for at least 12 months, long enough for the Treasury to work closely with banks to re-write problematic regulation and strengthen due diligence checks so that banks can once again be confident in servicing Somali money transfer organisations.

As Mo Farah explained, failure to do so is life or death for millions of Somalis. A recent UN report shows that 40 percent of families in Somaliland and Puntland receive remittances. This money is integral to their survival.

There are few options: Somalia has no formal banking sector. The remittance corridor is the only official means of getting money into the country. Istarlin explains “there’s a money transfer organisation on the high street. Every month I’ll transfer £100. It costs me just £2.50.”

Money eventually reaches Somalia having criss-crossed multiple regulatory jurisdictions. In recent months, banks’ interpretation of legislation on money laundering and counter terrorism has become tighter and more risk averse.

In late 2012, HSBC was fined a record £1.2 billion by US regulators. Reports suggested HSBC accounts in Mexico and the US were being used by drug barons to launder money. HSBC is not alone in falling foul of the regulators following large-scale money laundering as regulatory authorities on both sides of the Atlantic have stepped up efforts to combat illicit flows of money.

In late 2012, HSBC was fined a record £1.2 billion by US regulators. Reports suggested HSBC accounts in Mexico and the US were being used by drug barons to launder money. HSBC is not alone in falling foul of the regulators following large-scale money laundering as regulatory authorities on both sides of the Atlantic have stepped up efforts to combat illicit flows of money.

But this has little to do with Somalia. The similarities are slight. Most Somalis living in the UK are not wealthy. Individual transfers are usually less than £200, and often as little as £25: average income in Somalia is under £200 a year. So far no Somali operators have had any accusations against them. Failing to find a solution risks driving transfers underground which is in no-one’s interest, not least the regulators.

In my short time at Oxfam I’ve seen the very best of banking; impact investment, financial inclusion and socially responsible investment – for example our Behind the Brands financial sector engagement. Banks can and do facilitate development.

But Barclays is getting it seriously wrong at a time when it is desperately trying to re-brand. Instead of championing its ability to channel money safely to poor people in a remote land, Barclays is in effect imposing a financial boycott on some of the world’s most vulnerable people.

Somalia has been torn by more than two decades of conflict. Over 2 million people remain displaced, inside and outside the country. 43% of the population survives on under a dollar a day.

At the time of writing (Monday, 10pm) there is brief respite for one major Somali money transfer organisation. Barclays will extend for two weeks, with details emerging of another bank facilitating corporate and aid money transfers, but not yet the crucial individual remittances. Barclays still planned to close the other three money transfer organisations’ accounts.

If sustainability is central to the way Barclays does business, the moral implications of this decision must be considered alongside the financial. On that basis there remains an obligation to ensure that remittance channels remain open.

basis there remains an obligation to ensure that remittance channels remain open.

Barclays is no monster. I have several friends that work there. They can cite a dozen good things Barclays does, but they too are frustrated at this spectacular own goal and the needless suffering it will cause. It’s time for Barclays to show some leadership.

If Barclays decides to keep open a lifeline to some of the world’s most vulnerable people, is it really going to run a serious risk of prosecution under laws designed for entirely different circumstances? The Treasury ought to be able to put their minds at rest on that.

But even if there is some small risk, Barclays could count on a lot of allies to back them in keeping the lifeline open – not least the 100,000 signatories, Mo Farah and international NGOs who’ve been campaigning for them to see sense.

over 100,000 signatories, Mo Farah and a growing number of international NGOs.

September 29, 2013

Climate Change looks a lot worse when you look below the averages and the global: the view from Pakistan

John Magrath

from Oxfam’s research team compares the impact of climate change in Pakistan with the messages coming out of the IPCC’s  latestreports.

latestreports.

I blogged last week how one effect of climate change is likely to be to make it harder for people to afford to buy the food they need, which may be a bigger cause of hunger than absolute reductions in food supplies per se. Most of us buy the food we need, rather than grow it; even poor smallholder farmers are usually net food buyers. How climate change will raise prices and reduce incomes is the theme of Oxfam’s new report, Growing Disruption.

Last Friday saw the release of the summary report on the physical science behind climate change from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The report is a synthesis of the last five year’s worth of research on the physical science. It confirms that scientists are now 95% certain that the global warming that has happened since 1950 has been caused by human activity and it warns that some climate impacts that are happening now are happening much faster than had been anticipated. The rate of Arctic sea ice retreat has doubled, sea level rise has accelerated and the oceans are acidifying fast.

But as with previous IPCC reports, every new certainty is regarded by denialists as evidence of effrontery or conspiracy, and every refinement in understanding and consequent tweak in the analysis is seized upon by denialists as evidence of uncertainty and ineptitude. If you’re a climate scientist, you clearly can’t win; you’re either mad or bad, and certainly dangerous to know.

The IPCC discussion in Stockholm last week only looked at the global picture, which can be somewhat misleading. The IPCC concludes, for example, that there isn’t so much confidence that global average drought has increased, or global average precipitation either. This row-back from previous levels of confidence is taken by denialists to mean that even if climate change is happening, nothing much (bad) is happening as a result. Or that scientists never knew what they were talking about in the first place.

But of course averages don’t tell us much. The IPCC confirms that wet regions are generally getting wetter and dry regions drier (so the rainfall average stays the same); and we’re all getting hotter. The full report will be much more revealing on the regional impacts of climate change.

With this in mind I spoke to my colleague Abdul Majik Khan, who’s been running humanitarian emergency programmes for Oxfam in Pakistan for the last four years. In Growing Disruption we briefly discussed Pakistan and how the devastating mega-flood of 2010 caused a 75% reduction in income across all households affected.

With this in mind I spoke to my colleague Abdul Majik Khan, who’s been running humanitarian emergency programmes for Oxfam in Pakistan for the last four years. In Growing Disruption we briefly discussed Pakistan and how the devastating mega-flood of 2010 caused a 75% reduction in income across all households affected.

Abdul points out that few have recovered as three more years of (less publicised) floods have occurred since. Now half the population are “food insecure” – they basically can’t be sure where their next meal is coming from. There are a huge number of interlocking reasons for this tragic regression, ranging from deep-rooted social and economic imbalances and injustices in rural areas to an energy crisis, business closures and workers losing their jobs in the towns. You can throw insecurity and political violence in for good measure. Nevertheless, Abdul says a more hostile climate has become a potent risk multiplier.

Four consecutive years of floods means that the harvest has been almost completely destroyed in many areas in South Punjab and Sindh, the breadbaskets of the country. Poor farmers have lost out on three levels – their employment and income from being as labourers, their own supply of food and the crops they would sell to get additional income. Food prices are going up, hitting urban consumers just as their earning opportunities nosedive.

According to Abdul:

“It’s true we’re managing our water resources poorly, and have been for 40 years; that’s not changed. But what has changed is the pattern and timing of the rains. We have very extensive rains, especially in areas where we didn’t really have monsoons before; and the rains have been coming

later every year now for four or five years. Farmers can’t grow crops – either crops don’t mature because the rains are late or in other areas people are about to pick the crops when the rain starts and batters them down. And that’s why we’re getting these floods year on year”.

The IPCC’s analysis of regional impacts will probably formalise what’s been said in several studies. These predict a decrease in rains across South Asiafrom December to February – but for Pakistan a 30% increase in rains from September to November (and 50% more by the end of the century), with a large increase in run-off.

The worrying part of this is that the regional studies didn’t think that this would start happening until mid-century. But as with many other manifestations of the physical science discussed this week – such as accelerating Arctic sea ice decline or rising sea levels – things seem to be happening quite a lot faster than we’d been expecting.

And it isn’t just the Polar bears for whom that is very bad news indeed.

September 26, 2013

Making All Voices Count – promising new initiative (and source of funding)

A big new initiative on citizen voice, accountability etc was launched this week. OK it’s a bit obsessed with whizzy new technology, and light on power analysis and politics, but it still looks very promising, not least because it is being run by three top outfits – Hivos, IDS and Ushahidi. It is also a potential source of funding for work on accountability, whether programmes, research or campaigns – applications close 8 November.

Here’s the blurb from the website:

‘Making All Voices Count is a global initiative that supports innovation, scaling-up, and research to deepen existing innovations and help harness new technologies to enable citizen engagement and government responsiveness.

This Grand Challenge focuses global attention on creative and cutting-edge solutions, including those that use mobile and web technology, to ensure that the voices of citizens are heard and that governments have the capacity, as well as the incentive, to listen and respond.

Making All Voices Count is supported by the Department for International Development (DFID), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Open Society Foundations (OSF) and Omidyar Network (ON)..

The aim of Making All Voices Count is a substantial push towards effective democratic governance and accountability. We believe that open government depends on closing the feedback loop between citizens and government.

Making All Voices Count aims to close the feedback loop by creating:

tools to enable citizens to give feedback on government performance

stronger incentives for, and greater capacity within, governments to respond to citizens’ feedback

incentives and the capacity for citizens to engage with government to improve their policies and services.’

[H/T Nick Pialek, who also points out that given the state of internet bandwidth in many developing countries, the very snazzy web design may be self-defeating - hard to make all voices count if they can't access the website.]

And a two minute intro video, setting out the big idea.

Recent posts on transparency and accountability initiatives here and here.

September 25, 2013

The gender equality and poverty arguments for social pensions in Asia

For those among you who find a blog length piece about as much as you can absorb in a busy working day, I recommend signing up to the ‘one pagers’ produced by the International Policy Center on Inclusive Growth in Brazil (a UNDP/Government of Brazil joint venture). They provide nice summaries of new research. Here’s last month’s one pager on ‘gender and old-age pension protection in Asia’, by Dr Athina Vlachantoni and Professor Jane Falkingham, both of the University of Southampton:

produced by the International Policy Center on Inclusive Growth in Brazil (a UNDP/Government of Brazil joint venture). They provide nice summaries of new research. Here’s last month’s one pager on ‘gender and old-age pension protection in Asia’, by Dr Athina Vlachantoni and Professor Jane Falkingham, both of the University of Southampton:

‘Providing old-age social protection for women is a major policy challenge, as women’s working lives tend to be more diverse than men’s, often including periods of care-giving and part-time work. In addition, workers in the informal sector, where the majority of women work, are excluded from mainstream contributory pension systems designed for formal workers. Although social pensions can contribute significantly to lifting many women in low-income countries out of poverty, protection systems need to consider much more the diversity in women’s life courses and working lives.

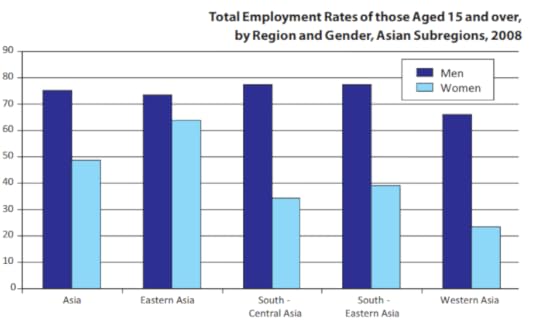

Across the world, women are more likely than men to experience poverty in old age, because of behavioural or life-course differences between men and women, and institutional features of modern pension systems. Gender differences in life courses lie in the areas of life expectancy and labour market participation rates. On average in 2009 in Asia, men could expect to live for 67.5 years, and women for 71.2 years. Living longer than men, women are more likely to experience widowhood in later life, to live alone and to face poverty for longer. In most countries globally, women are less likely than men to be employed in the formal labour sector, and are as or more likely than men to be employed informally. Women in Western Asia are the least likely to be employed, and women in Eastern Asia the most (see chart).

Social pensions present several advantages from a gender perspective—for example, they offer a safety net for informal workers with low earnings and few or no pension contributions. Also, as the eligibility criteria of social pension schemes often include conditions that women are more likely to meet than men, such as reaching older age or being widowed, social pensions are more likely to target older women than men—in Asia as across the world. Social pensions may also be used by policymakers and aid organisations as a mechanism for promoting greater gender equality. Finally, in addition to reducing poverty, social pensions can affect intra-family dynamics, gender relations and decision-making processes within the household by affording women greater financial security.

But social pensions have limitations. The level of benefits in most countries is low and hardly sufficient to lift beneficiaries out of poverty, while the effectiveness of social pensions depends on the extent to which they fit with contributory systems of social protection, as well as broader systems of protection including health care provision. Given that elderly women in Asia are more likely than elderly men to face poverty, the inclusion of a gender dimension in the design of social pension schemes could enhance their effectiveness in targeting those most at need.’

Very nice argument, bringing together several important issues – gender equality, the effectiveness of cash transfers as a form of social protection, the importance of the informal economy and the increasing need to focus on older people who constitute a large slice of the ‘chronic poor’ and thus should be a major focus in attempts to ‘get to zero’ on global poverty.

See here for previous post on ageing and development.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers