Duncan Green's Blog, page 202

November 17, 2013

What are the global trends in humanitarian response? How well is Oxfam responding?

Twice a year Oxfam’s Regional Directors gather with its UK-based big cheeses to swap notes (they let me join them, for some reason). It’s an opportunity to allow the collective mind to catch up with all those accumulating individual impressions of how the world and our work is changing.

opportunity to allow the collective mind to catch up with all those accumulating individual impressions of how the world and our work is changing.

Last week’s ‘deep dive’ was about humanitarian work: two days of conversations, questions and data dotted with video slots from emergencies experts in the UN, governments, academia and other NGOs telling us what they thought of our work. All this amid the intensity of a major response in the Philippines. The humanitarians seemed remarkably calm, considering.

What impressions emerged from the sea of flipcharts?

A sense if not of crisis, then of threat. To the humanitarian project as a whole, dogged by financing shortfalls, proliferating ‘weather events’, accusations of Western bias and questions about its ability to respond to the really big disasters like the Haiti earthquake. But also to Oxfam – amid a proliferating number of ‘humanitarian actors’, have we been trading on our reputation, failing to innovate? Are we Nokia or Apple?

Some serious history: a jointly constructed timeline showed the major world events of the last 70 years (decolonization, Vietnam, end of Cold War, end of Golden Age etc) through humanitarian specs. I’m becoming a big fan of starting almost any learning exercise with a timeline: it provides common reference points for all the subsequent discussions.

In this case, the fall of the Berlin Wall allowed us to work more in conflicts (before 1991, we mainly did natural disasters); each major humanitarian crisis (Rwanda, Asian tsunami, Haiti), led to a step change in the institutionalization/codification of the system, and the spread of coordination mechanisms and standards. Along the way we’ve moved from addressing consequences (‘emergencies’) to tackling causes (‘humanitarianism’).

In this case, the fall of the Berlin Wall allowed us to work more in conflicts (before 1991, we mainly did natural disasters); each major humanitarian crisis (Rwanda, Asian tsunami, Haiti), led to a step change in the institutionalization/codification of the system, and the spread of coordination mechanisms and standards. Along the way we’ve moved from addressing consequences (‘emergencies’) to tackling causes (‘humanitarianism’).

Huge enthusiasm for giving people cash, (whether in emergencies or not) and growing scepticism about anything else (food, seeds, tools, shelter). Increasingly cash transfers are combined with IT, eg smart cards with the family’s details, allowing a degree of customization.

The mixed blessing of being a humanitarian organization that also does long-term development and campaigning (humanitarian is less than half of Oxfam’s total spend). On the positive side, our global advocacy on humanitarian issues wins lots of strokes from the UN and others who are not allowed to do that kind of thing.

But it also creates tensions, not least for the swashbuckling Indiana Jones types trying to get clean water flowing within 48 hours of a disaster, who also have to take into account a long list of other considerations (governance, gender, long term recovery, institution-building, working with local partners and other Oxfam affiliates etc). I’m sure some of them must wish they could just go ahead and drill the borehole.

And the humanitarian system seems to impose some limitations on how far we can go with this – ‘The money is in operations, the need is in advocacy and thinking’.

The proliferation of new players: new donors, BRICS, private sector, Diaspora groups, many of whom are often very critical of the existing ‘UN-centric, Western-donor funded system’ (too Christian, too slow and bureaucratic, too expensive, too preachy).

The rising demand from governments, as they migrate from the ‘unwilling and unable’ to ‘willing and unable’ bracket and start looking for help with building their own capacity to respond.

The challenge of really making women’s rights central to our humanitarian work. That means women as agents, not just ‘beneficiaries’ (awful word) – should we partner with women’s organizations rather than traditional (and more gender-blind) humanitarian organizations? Why don’t we hand out webcams and other kit to women after a disaster and let them tell their own stories rather than packaging everything ourselves? Why aren’t we collecting gender disaggregated data on our disaster responses?

The shift from trying to do it all ourselves to working with (and through) partners: this feels exciting, but also trickier than it is in long term development (due to the urgency of crisis response, and the prevailing can-do mindset). What will be the impact on our ability to raise funds if the cameras are on local government officials, rather than Oxfam staff?

development (due to the urgency of crisis response, and the prevailing can-do mindset). What will be the impact on our ability to raise funds if the cameras are on local government officials, rather than Oxfam staff?

But the potential gains are huge: partners, whether CSOs, faith organizations or governments, are already on (or at least near) the ground, and can be active in those vital first few days after a disaster. They are much better placed to respond to the rising tide of small and medium-sized disasters that are one of the consequences of climate change.

If that all sounds a big abstract, that commitment to partnership is being stress tested right now in the Philippines, where we have helped set up the Humanitarian Response Consortium, made up of Filipino NGOs. My thoughts are with them, and the millions of their countrymen and women who need their help. If you have any spare cash, please dig deep.

November 14, 2013

Let’s Save Africa. The 3 minute youtube version. (It’s the Norwegians again)

What is it about Norwegians and aid satire? First Jan Egeland, then Africans for Norway and now this. Let’s Save Africa: not quite up to the standards of the other two, but well worth a watch (and better than answering your emails). Friday fun c/o @johanhermstad.

November 13, 2013

What does ‘big business’ say about Africa when it’s off the record?

I get a lot of random invitations along the lines of ‘come and be a token esteemed NGO rep at our next gabfest’, and accept a few of the more promising ones. So this week I ended up at a conversation on ‘Africa’s Reformers’ hosted by the Africa Governance Initiative and the FT’s This is Africa magazine (which has just published an issue with that title).

promising ones. So this week I ended up at a conversation on ‘Africa’s Reformers’ hosted by the Africa Governance Initiative and the FT’s This is Africa magazine (which has just published an issue with that title).

The round table was mainly business types – lawyers, bankers and multilnationals. No government people, no aid donors. (Sorry, can’t tell you who said what – Chatham House Rules). How did it compare with a more traditional aid event?

Firstly, lots of great practical experience of doing big business in Africa – people involved in putting together big infrastructure projects, meeting ministers, and getting messed around by officials. That probably tempered the excesses of Afro-optimism.

Those most on my wavelength were the long-term investors – stressing that it is institutions that matter, not a few business-friendly presidents – tales of Nigerian spin doctors in slick suits selling energy sector projects that never delivered to gullible investors.

It was fascinating to hear big extractives companies talking off the record about the need for land reform, accountability, inclusion and an end to ‘the concentration of wealth and power among elites… democratic accountability may be messy at first, but it is fundamental for long term investors.’ (Yes, really). They urged companies to invest in governments’ negotiating capacity so that they get a fair deal and the next government doesn’t rip it all up and start again (a particular source of rage for investors). Some even publish the minutes of their negotiations to reduce the risk of one day being accused of backsliding.

OK, I realize not all extractives or ag investors think like that, and I banged on about tax avoidance, business lobbying, land grabs etc, as you’d expect, as well as the growing constraints on civil society space and civil liberties in many countries.

Others were prone to the kind of ‘decent chapism’ that often besets politicians and even academics (‘Paul Kagame is a decent chap, let’s support Rwanda’). Some of the more alarming quotes ‘democracy is overstated’; the Rwandan and Ethiopian governments are ‘collectively feisty’.

This led to a fascinating exchange on whether democracy was an aspiration or a necessity, from the business point of view. Key point was what happens when the decent chap leaves office (even if he doesn’t go bad before then). ‘Democracy has a pre-built way of regenerating leadership’, said one.

happens when the decent chap leaves office (even if he doesn’t go bad before then). ‘Democracy has a pre-built way of regenerating leadership’, said one.

Just like aid types, they (Africans and non-Africans alike) were prone to lamentation and exhortation (Africa needs to do X) rather than analysis (what are the drivers and blockers to such changes). Might start a How Change Happens course for business sometime.

As co-host, the AGI is an interesting outfit. Set up as the Tony Blair African Governance Initiative, it seems to have airbrushed out the TB bit. Can’t think why. It acts as a kind of charitable management consultant, advising governments on how to improve their performance, and is currently working with about 8 African countries, usually working out of the president’s office.

It initially intended to transfer some of the thinking from Blair’s Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit, but rapidly discovered that the lessons of good governance in the UK often don’t apply in Africa. Instead, it is often AGI’s knowledge of Rwanda’s much-lauded public sector systems (where it’s been working for 5 years) that other African governments want to hear about.

Apart from the focus on individuals, the other feature that was all too reminiscent of many aid debates was ‘deficit thinking’. Africa is short of X (good governance, new laws , units on this or that), so all outsiders need to do is top up the deficit by importing the best models. The subtitle of the This is Africa report ‘re-wiring governance’ exemplifies the approach. But plenty of research by ODI, Harvard and others to show this is flawed logic: what works are often hybrid institutions that combine some imports with local traditions in a context-specific way, and the design of hybrids has to be in the hands of locals, not foreigners.

research by ODI, Harvard and others to show this is flawed logic: what works are often hybrid institutions that combine some imports with local traditions in a context-specific way, and the design of hybrids has to be in the hands of locals, not foreigners.

Some choice quotes:

‘If you’re the Minister of Finance it’s very hard to worry about long term development if by the 10th of the month, you are worrying about how to pay your civil servants’.

‘In the middle of a resource boom in Mozambique, donors were worrying about how many clinics and classrooms the mining companies would build, instead of funding the lawyers the government needed to sit across the table and negotiate properly.’

[From an African financier]: ‘The mistake we’re making in Africa is that we see it (laws, reforms, new mining codes etc) as something we have to do for foreign investors.’

And I’m glad to report that ‘Democracy is overstated’ got a pretty sharp response, and not just from me ……

November 12, 2013

What’s happening with the world’s civil wars and how do they end?

Here’s an edited-down version of a brilliant overview of the state of civil wars around the world in this week’s Economist:

Ending civil wars is hard. Hatreds within countries often run far deeper than between them. The fighting rarely sticks to battlefields, as it can do between states. Civilians are rarely spared. And there are no borders to fall back behind. A war between two states can end much where it began without the adversaries feeling in mortal danger. With nowhere safe to go home to, both sides in a civil war often feel they must carry on fighting if they are to escape slaughter. As those fighting in Syria know, defeat often looks like death, rather than retreat.

between states. Civilians are rarely spared. And there are no borders to fall back behind. A war between two states can end much where it began without the adversaries feeling in mortal danger. With nowhere safe to go home to, both sides in a civil war often feel they must carry on fighting if they are to escape slaughter. As those fighting in Syria know, defeat often looks like death, rather than retreat.

Yet civil wars do end. Of 150 large intrastate wars since 1945, fewer than ten are ongoing. Angola, Chad, Sri Lanka and other places long known for bloodletting are now at peace, though hardly democratic.

And recently civil wars have been ending sooner. The rate at which they start is the same today as it has been for 60 years, but they are coming to an end a little sooner. The average length of civil wars dropped from 4.6 to 3.7 years after 1991.

So far, nothing has done more to end the world’s hot little wars than winding up its big cold one. From 1945 to 1989 the number of civil wars rose by leaps and bounds, as America and the Soviet Union fuelled internecine fighting in weak young states, either to gain advantage or to stop the other doing so. By the end of the period, civil war afflicted 18% of the world’s nations. When the cold war ended, the two enemies stopped most of their sponsorship of foreign proxies, and without it, the combatants folded. More conflicts ended in the 15 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall than in the preceding half-century. The proportion of countries fighting civil wars had declined to about 12% by 1995.

The outcomes of civil wars changed, too. Until 1989, victory for one side was common (58%). Nowadays victories are much rarer (13%), though not unknown; the Sri Lankan government defeated Tamil rebels in 2009. At the same time negotiated endings have jumped from 10% to almost 40%. The rest of the conflicts peter out, subsiding to a level of violence below the threshold of war—though where that threshold should lie is a matter of some debate.

The main reason for jaw-jaw outpacing war-war is a change in the nature of outside involvement. In the Cold War neither of the superpowers was keen to back down; both would frequently fund their faction for as long as it took. Today outside backers are less likely to have the resources for such commitment. And in many cases, outsiders are taking an active interest in stopping civil wars.

The motives vary. Some act out of humanitarian concern. Others seek influence, or a higher international profile. But above all, outsiders have learned that small wars can wreak preventable havoc. Fractious Afghanistan bred al-Qaeda; the genocide in tiny Rwanda spread murder across a swathe of neighbours. In coastal west Africa, violence is passed back and forth between Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast like a winter cold round an office.

Outsiders can weigh in on one side, backing their desire for peace with cold steel. In Mali a brawl involving a mutinous army, ethnic rebels and Islamic extremists ended after less than a year thanks to French soldiers, who intervened in January and forced a partial reconciliation. [But overall], ever fewer powers, though, have the stomach for an overt armed intervention.

Orchestrating talks towards an end like the one brokered in Lebanon requires strong nerves and stomachs. Civil wars tend to end as messily as they are fought. Negotiations often take place in parallel with combat. For years Nepalese guerrillas negotiated with the government while also pummelling it, finally signing a peace deal in 2006. The prospect of an ending can quite often intensify the fighting.

Sometimes the dispute is so intractable that no agreed solution short of the break-up of the state seems possible. Wars of identity—those in which populations are mobilised by grievances that have ripened over decades or centuries—are the most likely to belong to this category.

Some break-ups do make sense. South Sudan’s government is lousy, and fighting continues along the border set up with the rest of Sudan two years ago. But most independent observers agree that the south made the right choice in negotiating to split off. The Arab elite in the north was never going to change its murderous attitude toward black southerners that brought about decades of miserable war and the death of 2m people. And there is little worry that South Sudan will look so attractive as to encourage secession elsewhere. Few minorities would accept such pain to win a seat at the UN.

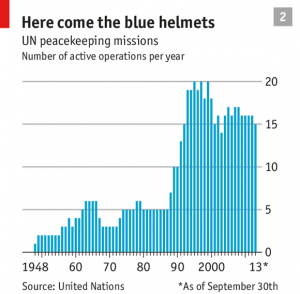

In talks aimed at a one-state solution, history suggests that several things can better the odds of success. The prospect of UN blue helmets is one (see chart). In Bosnia the outgunned Muslims could only imagine resting what rusty arms they had when assured of protection by trusted outsiders. In conflicts where parties agree not just to pause but also to disarm—thus further reducing the chances of more war—this is essential. Guerrillas worry that, without weapons, they will face oppression once again and stash some away.

In talks aimed at a one-state solution, history suggests that several things can better the odds of success. The prospect of UN blue helmets is one (see chart). In Bosnia the outgunned Muslims could only imagine resting what rusty arms they had when assured of protection by trusted outsiders. In conflicts where parties agree not just to pause but also to disarm—thus further reducing the chances of more war—this is essential. Guerrillas worry that, without weapons, they will face oppression once again and stash some away.

Civilian mediators can be useful too, sometimes opening up negotiating tracks states cannot, and being trusted to operate without their own political agenda. Only when the fighters have been disillusioned, can mediators get to work—and then only for a limited period. Civil wars unresolved for more than a decade seem to drag on for ever, with both sides resigned to perpetual fighting, too disgusted or exhausted to face their enemies across the negotiating table. The armed conflict in the dense mountains of Colombia has been going since 1964. In some cases causality may run the other way. Conflicts last because they are unresolvable.

And conflicts recrudesce, too. Peace settlements can break down; indeed some worry that, at the moment, it is particularly easy for rebels to go back to war. Heavy weapons are easier to come by than once they were and insurgency tactics have been refined in Iraq and elsewhere.

The question of how outsiders can push settlements along is among the trickiest in international relations. One idea is to engineer a change in leadership. Warlords who start conflicts are rarely prepared to admit that they cannot win, and their charisma can be central to the cause. The capture of Abdullah Ocalan by Turkish forces in 1999 was such a blow to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party that peace talks have been going on ever since. Peru’s Shining Path withered after the 1992 capture of Abimael Guzmán. Leadership changes are a factor in the termination of between 25% and 40% of civil wars.

Changing leaders is not the only way to intervene. By using military power or curtailing the flow of money, outsiders can engineer what scholars call a “mutually hurting stalemate”. In this neither side can advance and the cost of holding tight is high—making peace the least bad option. In 1980 Britain ended Zimbabwe’s civil war by simultaneously squeezing the government and persuading Mozambique and Zambia to threaten to end the aid that they supplied to the rebels making gains in the field.

November 11, 2013

What’s the added value of bringing together projects on the same issue in lots of countries?

I’m always on the look out for particularly interesting and innovative Oxfam projects, and usually big them up on this blog (think Tanzania, Tajikistan, We Can). After a few years of doing this, one of the striking (and depressing, at least for me) things is how seldom these pioneering projects have (so far, anyway) been picked up and adapted/replicated elsewhere.

We Can). After a few years of doing this, one of the striking (and depressing, at least for me) things is how seldom these pioneering projects have (so far, anyway) been picked up and adapted/replicated elsewhere.

So I was excited by the potential of a completely different approach: global programmes. Instead of ‘Potemkin Projects’ in one country, a global programme hoovers up a whole bunch of roughly similar national and regional work in different countries, and promotes mutual exchanges and learning. Does such an approach have better prospects than fanfares about ‘islands of excellence’?

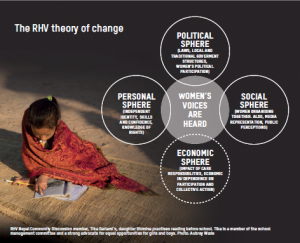

Yesterday’s summary of the work of Raising Her Voice, a 19 project global programme to enhance women’s voice in decision-making, spanning 4 continents, suggests that it might.

RHV builds on Oxfam’s long-standing focus on women’s empowerment. It arose in response to the funding opportunity provided by a 2008 DFID call for proposals to explore issues arising from the UK Government’s White Paper on Governance and Transparency. An email duly whizzed round, inviting OGB country programmes to submit proposals based on their own, and their partners’, capacity and focus.

We got the money, took on a central coordinator, and started work. What is interesting is what happened next. Over time, in addition to beavering away in their separate locations (and getting some great results, as the evaluation spells out), the 19 separate projects have shown increasing signs of cohering, with exchanges of ideas and personnel. A key moment came a couple of years in, when a mid-term evaluation identified a ‘theory of change’ that seemed to be emerging from the overall RHV exercise.

The theory (see diag) identifies three broad spheres - personal, political and social – which influence women’s opportunities to participate in governance, and which need to be included in order to strengthen women’s voice:

The political spaces need to be more open, inclusive and representative of women. This includes public and customary laws, policies, structures and decision making processes, the mechanisms by which women can claim and uphold their rights and interests.

For a woman to create, access and take-up opportunities for participation and influence, she needs personal capacity, self-esteem and confidence. The RHV theory of change highlights the need to work on this sphere, to redress the situation whereby the political and social spheres have strong influence over a marginalised woman’s ability to participate, influence and secure her rights, but she has little opportunity to influence them back.

The social sphere supports and embeds changes in attitudes, relationships and behaviours. It includes norms promoted or upheld by cultural and religious institutions and the media, as well as the strength and capacity of the women’s movement and civil society to support women with a platform to raise their voices.

The social sphere supports and embeds changes in attitudes, relationships and behaviours. It includes norms promoted or upheld by cultural and religious institutions and the media, as well as the strength and capacity of the women’s movement and civil society to support women with a platform to raise their voices.

Subsequent discussions added an economic sphere, in recognition of the central importance both of the care economy and economic (in)dependence in shaping the opportunities for women to exercise voice.

The theory of change proved useful in several ways:

It provided guiding principles for RHV, capturing the arenas in which change in women’s voice occurs

It ‘kept it simple’ – very important for hard pressed staff and partners

By being very top line, it allowed a variety of RHV programmes to recognize their work within it, while also pointing to new ideas and possibilities

At a global level, RHV staff were required by DFID to revise each country logframe and indicators in line with the ToC

Quite independently of any suggestions from Oxfam House, several national RHVs used the theory of change to help design ‘course corrections’ to improve their work, either in response to improved understanding, or to events and changes in the context.

For me though, the 3 sphere model falls short of being a full theory of change. It omits a number of important aspects, which could have helped build more imaginative and effective strategies. These include how women’s lives and the norms that govern their role are changing (increasing literacy, entry into paid jobs, spread of political quotas etc); the importance of critical junctures - many shifts in women’s voice occur linked to wars, elections, or other shocks – and the need for an analysis of the wider drivers and blockers for expansion in women’s rights (state officials or elected representatives, private sector, faith organizations etc).

In practice, these gaps were often addressed at the national level, as partners developed their own theories of change, into which this uber-narrative later fed, but I see no reason why the overall ToC shouldn’t have included them.

Overall, there are several potential benefits from the Global Programme Approach: These include

Fund raising: donors need to disburse funds in large (by NGO standards) volumes and at high speed. But over-large grants and short timescales can impose severe strains on small civil society organizations. A global programme approach can square the circle.

The chance to pilot research in one country, then adapt and try again in another. The best cross-fertilization is often not planned – RHV in Honduras picked up a 2011 study from RHV Nepal, translated it into Spanish, and used it to develop its thinking on working in the personal sphere.

Country programmes are motivated by being part of a global change process

And the lessons on how to run global programmes?

Keep it as open as possible at the beginning and allow it to gell and evolve. That means not being too prescriptive about what national offers are included in the initial proposal.

At least when addressing complex and deep-rooted issues such as women’s (dis)empowerment, they should also be as long as possible. RHV was a five year programme. Much of the most innovative work was carried out in years 4 & 5, as staff and partners learned and adapted their strategies, becoming more assertive for example in shifting from a less ‘political’ focus on service provision to more explicitly challenging inequality and household power relations.

The programme can be encouraged to evolve a coherent theory of change that will guide its future work by building in a 6-12 month inception period for consultation and design at national level.

Especially in light of last week’s focus on complexity and emergent change, it seems that this global programme cat-herding approach might have some real promise. It could even serve as the basis for a ‘do tank’ exercise I discussed a couple of weeks ago, in which we combine the global programme approach with a research component that generates hypotheses to test on the ground.

What do you think? Any other good examples out there?

November 10, 2013

What have we learned about women’s empowerment from a 17 country global programme?

Oxfam is increasingly going in for ‘global programmes’, bundling up work on similar issues across various countries. More on that model tomorrow, but first I want to highlight the findings of a final evaluation (published today, right) of Raising Her Voice (RHV), a big (£5.8m), 5 year global programme to enhance women’s voice in decision-making, covering 17 countries and two regional projects across 4 continents.

work on similar issues across various countries. More on that model tomorrow, but first I want to highlight the findings of a final evaluation (published today, right) of Raising Her Voice (RHV), a big (£5.8m), 5 year global programme to enhance women’s voice in decision-making, covering 17 countries and two regional projects across 4 continents.

Excerpts from the evaluation, plus running commentary from me in square brackets:

[building 'power within' - confidence and assertiveness + 'power with' via women's organizations was key to getting progress on political voice]

‘RHV projects have been most effective where all three spheres (personal, social and political) are clearly addressed – usually in partnership with others – and where complementary work was carried out to link pressure for change at local, district, and national and international levels.

Work on personal empowerment is the bedrock for all change processes, recognising the importance of women’s knowledge and confidence in their ability to influence power relations and decision making.

• For women’s participation and leadership to be meaningful investment is required to ‘grow’ the political confidence and influencing capacities of women activists, including power mapping, social audits and mentoring, as much as increasing the number of women in decision-making spaces.

‘We need political education. Otherwise, once we manage to have dialogue and they start talking to us about things like municipal budgets, it’s like jumping out of a plane with no parachute. If they are talking about infrastructure, I have to know about infrastructure. If they are talking about territorial rights, I have to know about territorial rights.’

Bertha Zapeta, RHV Guatemala

• This core of activists and leaders needs long-term support to be effective as leaders, change agents and role models. A scatter gun approach of ad hoc interventions targeting large numbers of women does not lead to sustainable benefits.

[violence against women is a key obstacle and has to be addressed]

• Explicit attention must be given to developing a wide range of strategies to reduce the risk of violence for women and provide them with protection and support. Not only because the threat of violence negatively impacts on women’s participation, but because successful governance programming, which challenges the status quo, can provoke backlash.

In the social sphere ‘changes, especially in relation to networking and solidarity, are the glue enabling greater changes in the other two’.

• Collective action and voice is critical for women’s safety, for demands to be made unapologetically and for them to be taken seriously by those in power. The RHV evaluation found some of the strongest and most sustainable impact was where projects contributed meaningfully to the strengthening, collaboration, and organisation of civil society organisations working for women’s rights.

‘It was a huge challenge to acknowledge each other and stop labelling. Women do not necessarily trust each other, so you need to build bridges to strengthen the demands of all women without discrimination.’

RHV Bolivia

[alliances need to include 'non-usual suspects', including men]

• Greatest leverage is achieved through building broad-based and creative alliances which, although time consuming, are essential for strengthening the collective action needed to shift the structural and attitudinal barriers to effective governance.

• Signing up the powerful by forging constructive relationships from the outset with influential male opinion leaders and shapers was crucial for supporting these far-reaching change processes.

RHV Nepal rewarded male champions through media coverage of visits to, and support for, community initiatives benefiting women. In Nigeria, targeted influential individuals in the media joined project steering groups and acted as core campaign partners. More strategic political and media partnerships have helped to bring key opinion shapers on board to challenge gender stereotypes and promote positive, balanced voices on important gender equality issues.

RHV Nepal rewarded male champions through media coverage of visits to, and support for, community initiatives benefiting women. In Nigeria, targeted influential individuals in the media joined project steering groups and acted as core campaign partners. More strategic political and media partnerships have helped to bring key opinion shapers on board to challenge gender stereotypes and promote positive, balanced voices on important gender equality issues.Changes in the political sphere – in legal frameworks, power structures and accessibility of decision-making – are essential steps towards increasing women’s participation and influence, but progress is slow and multifaceted.

• The power of evidence-based advocacy is clear from the experience of numerous RHV country projects that used social audits to evidence underinvestment in, or poor quality of, local services and map (non)compliance with commitments to women’s rights.

Examples include analysis of political party manifestos relating to female genital mutilation in The Gambia and audits of nine health centres and three hospitals in Guatemala. In Chile, annual public surveys were used to shape influential campaigns on women’s participation, with both strong political legitimacy and high levels of public support – so that ‘the voice on the street and in the countryside is backed by the voice of academic authority.’

[one of the roles for outsiders is to link up grassroots activists with national politics]

• Linking community activism with sub-national and national calls for change to address the ‘missing middle’ of governance processes. In Pakistan, Women Leader Groups have worked at community, district and national level to bring invisible women’s voices directly and strategically to those with decision-making power. Strategies included the first National Women’s Manifesto, developed in 2012 through widespread consultation to provide political parties with an unapologetic list of demands for fairer rules of political engagement for women.

[formal politics matters]

• Unashamedly political – RHV partners have shown a stronger understanding over the five years of how power works, where it lies and how to influence it. In Nigeria, successful advocacy for the passing of the 2013 Violence Against Persons Prohibition Bill, led by RHV partner WRAPA, included hiring a former legislator to navigate the corridors of power, text message barraging of Ministers and highly publicised mock tribunals. Pre-election campaigns in Nigeria, Mozambique and Pakistan used ‘Vote for the Domestic Violence Bill or We Won’t Vote for You!’ slogans to push for legal reform in the face of continued impunity for rights violations.

Many projects engaged directly with political parties, recognising that these are critical spaces for long-term policy influencing. In South Africa and Honduras, RHV women’s networks signed agreements with newly elected councillors to ensure that representatives deliver on a list of clearly articulated commitments made on priority issues. RHV partners and activists have also taken advantage of decentralisation and constitutional review processes, and used public interest litigation to further prise open spaces to advance women’s rights.’

Impressive, more from RHV coordinator Emily Brown here, and at least some of the successes seem to stem from the global programme model – more on that tomorrow.

November 7, 2013

How complexity thinking cut malnutrition in Vietnam by two thirds

To end complexity week, another of the fascinating case studies from Ben Ramalingam’s Aid on the Edge of Chaos

In December 1991, Jerry and Monique Sternin arrived in Vietnam so Jerry could take up the role of Save the Children US Country Director. The country was still labouring under a US-led economic embargo and had seriously high levels of child malnutrition, affecting 65 per cent of all under fives. Supplementary feeding programmes delivered by international agencies were expensive and the benefits were seldom sustained beyond their lifetime.

And the political climate was not welcoming for an American representative of a US non-governmental organization. One high-ranking official told Sternin a week into the visit, ‘There are many officials who do not want you in this country. You have six months to demonstrate impact, or I’m afraid my ministry will be unable to extend your visa.’

Just occasionally, just enough pressure is just what is needed to spark new ideas. Sternin remembered a Tufts University colleague, Marian Zeitlin, who was supported by the UN Children’s Fund and the (WHO) Organization to examine the phenomenon of positive deviance: the off-the-chart performance— in health, growth, and development—of certain children in a community compared with others.

Zeitlin trialled a version of positive deviance in Bangladesh, working with BRAC, to examine diarrhoeal infection and malnutrition in infants. The approach focused on mothers’ wisdom and knowledge, especially in relation to positive deviants: Zeitlin and her colleagues used scientific behavioural trials to identify the factors that led to positive deviance, then used this knowledge in the design and roll-out of interventions.

However, the Sternins did not have the resources or the time to do this. Instead, they used the principles of positive deviance as the basis for a different approach. Monique Sternin told me that one of their key goals was to make the positive deviance approach operational, with the community taking the lead, although Zeitlin’s work was essential in terms of providing the scientific justification.

After numerous negotiations, the Sternins finally obtained a mandate to start working in Quong Xuong district in Than Hoa province, some four hours south of Hanoi. They had just over a dozen weeks to demonstrate impacts before their visas were pulled. In the community, however, the limited amount of money they had was less than pleasing for the local officials involved, who were not happy about promises of ‘nothing more than “capacity building” and “self-reliance” ’.

Eventually, however, the Sternins were allowed to work in four communities with 2,000 under-three year olds, 63 per cent of whom were malnourished. Driven ‘more by faith than by proof ’, and armed with their belief in the evolutionary principles of positive deviance, the Sternins told the heads of the major village committees that the approach was going to be about finding solutions that were already in the community, which would have to take responsibility for their identification and application.

To their considerable surprise, the villagers were very keen on the idea. They had previously experienced only short-term aid projects after which they had watched their children’s health gains deteriorate again. This sounded different and more beneficial. After the children were weighed, they were ranked according to their family’s economic status.

Volunteer groups then identified the positive deviants. Sternin remembers asking the volunteers, ‘Is it possible for a child to be very poor and still well fed?’ and the volunteers literally leaping from their benches shouting, ‘Co co, co co!’ (‘It is, it is!’). It turned out that much of what was being done differently in the positive deviant families was tacit and unconscious: the individuals in question weren’t even consciously aware they were doing anything different or new.

Teams of volunteers undertook observations in their homes and found some intriguing things, some of which were common to all the positive deviant families. The two standout practices related to the content of the diet and the way food was administered. In every positive deviant family, the mother or father was collecting a number of tiny shrimps, crabs, or snails—making for a portion ‘the size of one joint of one finger’—from the rice paddies and adding these to the child’s diet. ‘Although readily available and free for the taking, the conventional wisdom held these foods to be inappropriate, or even dangerous, for young children.’

Teams of volunteers undertook observations in their homes and found some intriguing things, some of which were common to all the positive deviant families. The two standout practices related to the content of the diet and the way food was administered. In every positive deviant family, the mother or father was collecting a number of tiny shrimps, crabs, or snails—making for a portion ‘the size of one joint of one finger’—from the rice paddies and adding these to the child’s diet. ‘Although readily available and free for the taking, the conventional wisdom held these foods to be inappropriate, or even dangerous, for young children.’

Families also varied the frequency and method of feeding. Other families fed young children only twice a day, before parents headed to the rice fields early in the morning and in the late afternoon after returning from a working day. Because these children had small stomachs, they could only eat a small amount of the available food at each sitting. The positive deviant families, however, instructed the home babysitter (an older sibling, a grandparent, or a neighbour) to feed the child regularly, four or even five times a day.

Using exactly the same amount of rice, their children were getting twice the amount of calories as their neighbours who had access to exactly the same resource. Other key factors included atypically high levels of hand hygiene in positive deviant families.

At this point, the Sternins resisted the powerful temptation to ‘teach’ the community what they had learnt, because ‘Our past development work failures . . . had all occurred exactly at the moment in which we now found ourselves; the moment at which the solution is discovered. The next, almost reflex step, was to go out and spread the word; teach people, tell them, educate them.’

This time, they decided, the key would be to give community members the opportunity to share and learn directly from each other, with a focus on fostering and facilitating the exchange of practices. At its core, this meant turning a conventional approach to behavioural change—that of Knowledge–Attitude–Practice (KAP)—on its head.

The basic premise of KAP is that, by changing knowledge, you change attitudes and practices. However, the failures in this approach are obvious: millions still smoke, overeat, and so on.

The Sternins reversed the process, to work on Practice–Attitude–Knowledge. ‘You start by enabling people to change their practice, which then changes their attitude, and ultimately they internalize new knowledge.’ This beguilingly simple idea would become the basis of the positive deviance mantra, and go on to inform thousands of applications around the world over the next two decades: ‘It’s easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than to think your way into a new way of acting.’

Over a two-week period, the Sternins provided guidance and tools on collecting data on the positive deviant practices. The progress was shared on a board in the town hall, and the charts quickly became a focus of attention and buzz.

board in the town hall, and the charts quickly became a focus of attention and buzz.

A few short weeks later, district health staff assessed progress to date. The findings were remarkable: some 40 per cent of the children had already been fully rehabilitated, and a further 20 per cent were well on the way. Granted another six-month visa for their efforts, the Sternins continued their work. By the end of the first year, half the children had participated and 80 per cent were rehabilitated.

The model was taken on and applied by the Vietnamese National Institute of Nutrition, and after this by the government, which scaled it nationally. Over time, the positive deviance approach saw a sustained reduction in malnutrition rates of 65–80 per cent, and reached a population of 2.2 million.

November 6, 2013

Aid on the Edge of Chaos, a book you really need to read and think about

I held off reviewing Ben’s book til after last night’s launch at ODI, so that I could add any useful extra info or soundbites. Here goes.

It’s smart, well-written and provides a deeper intellectual foundation for much of the most interesting thinking going on in the aid business right now. Ben Ramalingam (right)’s Aid on the Edge of Chaos should rapidly become a standard fixture on any development reading list.

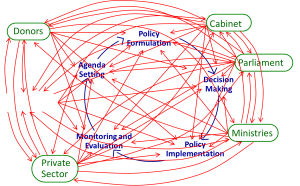

The book argues for a major overhaul of aid in recognition that the world is made up of numerous interlocking complex systems, far removed from the assumed linear world of cause → attributable effect that underpins a lot of aid programmes. That fits pretty perfectly with a lot of the stuff on governance, institutional reform etc from ODI, Matt Andrews, and Oxfam’s own work, all covered on this blog. But it adds to it in important ways.

It deepens our understanding of complexity and systems thinking, drawing on a range of other disciplines

Much of the current aid thinking about complexity is happening in work on governance and (to a lesser extent) advocacy. The book widens the scope to just about every corner of the aid business – management, humanitarian, health etc

Its 25 great case studies will spark ideas in people’s heads about how they can apply the thinking in their own work

The argument is divided into three sections: a thorough critique of the current aid system; an introduction to complexity and systems thinking; and a final ‘so what’ section on the reform of aid.

The writing is authoritative, with humour and real verve, plus a lovely turn of phrase (unusual from an aid wonk, but then Ben has hinterland, including being an aspiring playwright). Lots of memorable one liners and quotes (‘Some problems are so complex that you have to be highly intelligent and well informed just to be undecided about them.’)

The aid debunk may be necessary, but it’s not that new – critiques of logframes, ‘bestpracticitis’ and results fetishism are pretty standard, certainly on this blog. And it feels overdone – do we really need another 132 page takedown? Can we get onto the complexity bit please? The ferocity of the critique and the proliferation of straw men (the aid world as depicted here is static, monolithic and pretty much devoid of self doubt and internal debate, whereas my experience is that it spends a lot of time on both) also worried me. There is a risk that by adopting such a tone, the book could alienate aid workers, making them throw the book down as a caricature before they get to the important ‘so whats’ at the end.

The second chunk of the book provides a great introduction to complexity and systems thinking. If anything, Ben has read too much (again, not a common problem in aid land), because it’s easy to get lost in all the exposition – cities as complex systems; agent-based modelling; edge of chaos; fitness landscapes; network theory; power laws; sandpile thinking: yay! a whole picnic hamper of new jargon! It’s all a bit indigestible on a single reading. I got a lot more when I went back and reread it.

The second chunk of the book provides a great introduction to complexity and systems thinking. If anything, Ben has read too much (again, not a common problem in aid land), because it’s easy to get lost in all the exposition – cities as complex systems; agent-based modelling; edge of chaos; fitness landscapes; network theory; power laws; sandpile thinking: yay! a whole picnic hamper of new jargon! It’s all a bit indigestible on a single reading. I got a lot more when I went back and reread it.

Finally, (page 240) we get to the so whats: what the aid system needs to do differently to make it function better in complex systems. This is not easy, as Ben has to tread the fine line between coming up with a new blueprint – committing the very sin he is criticising – and helpless paralysis: ‘all too often it can serve simply to highlight what shouldn’t be done, or how not to work, in a complex setting.’

There’s some really useful stuff here, first on mindsets: Development is full of ‘self-organizing systems’, constantly evolving in unpredictable ways. The key for anyone engaged in the aid business is to put their own role aside, take a deep breath and look: ‘map, observe, and listen to the system to identify the spaces where change is already happening and try to encourage and nurture them.’

But also on the practicalities. The book is a treasure trove of examples squirreled away by Ben – eco-health systems approaches that have had a huge impact in Kenya via ‘integrated malaria management’; ‘positive deviance’ approaches to child health in Vietnam; simulation games; adaptive management: Ben holds up Odysseus as the role model, ‘navigating a course between order and chaos’. Some of this is more relevant to the big guys – DFID, the World Bank etc – who have the resources to think in terms of system-wide interventions, but there’s plenty for us little NGOs too. This section should stimulate new options in even the most jaded aid worker.

All great, but I have one overall concern and that’s structure. Isn’t a bit weird that a book about complexity has such a profoundly linear structure (problems of aid → what is complexity → so what), meaning you only get to the really important and useful bit on page 240? Conclusion? Shoot the editor, and maybe ask the publisher to publish pages 240-360 separately for time-poor, reading averse NGO types.

But let’s not end with a whinge. The book explains that in the language of complex systems, its title ‘Edge of Chaos’ is ‘hypothesized as the optimal position for learning’. This book both contains and encourages some essential learning for making us look harder and more creatively at the world we are trying to influence, and designing better aid programmes as a result. We should give thanks (and give each other copies for Christmas).

position for learning’. This book both contains and encourages some essential learning for making us look harder and more creatively at the world we are trying to influence, and designing better aid programmes as a result. We should give thanks (and give each other copies for Christmas).

And the most salient points coming out of last night’s launch?

Cost: work in complex systems requires more monitoring, more adaptation. Even if you get it right, it will be a lot more expensive than sticking to working in ‘islands of linearity’

Communications: we need to communicate this, but not through baffling geekspeak on ‘complex adaptive systems’. Best way is to tell stories (as Ben does so well).

Ben’s last word: ‘We in the aid should move from being people who know the answers to people who know what questions to ask.’ Nice.

November 5, 2013

Complexity 101 – part 2: Getting to the So Whats

It’s complexity week on the blog, coinciding with the launch of Aid on the Edge of Chaos today at 5pm UK time (long since full, but being livestreamed). I’m a discussant, and will nick any clever comments for tomorrow’s review of the book. Meanwhile, the ODI’s Harry Jones continues his stocktake on complexity and development

livestreamed). I’m a discussant, and will nick any clever comments for tomorrow’s review of the book. Meanwhile, the ODI’s Harry Jones continues his stocktake on complexity and development

Yesterday, I tried to pose and answer some straight questions on complexity and development, mostly focusing on whether development problems are complex and why it matters. Today, I try to answer the ‘so what’ question and suggest three areas where changes to aid agency practice could be made:

1) How can development agencies tackle complexity?

Aligning with the three challenges outlined yesterday (distributed capacities, divergent goals and uncertain change pathways), I’d argue that all solutions proposed to deal with complexity fall into one of the three categories:

Interventions must capitalise on distributed capacities, finding ways to link up actors and action that fosters more voluntary coordination and collaboration.

Interventions must facilitate joint interpretation of key problems by key actors, and must enable negotiation on and commitment to common goals.

Interventions must innovate, must foster learning about how change happens, and must be flexible enough to adapt to emerging signals.

This is the reverse of the typical bureaucratic reaction to complex problems, which seeks to ‘reduce’ complexity by strengthening centralised oversight, agreeing up front on narrow, singular goals, and trying to determine in advance what will work and what will be needed. While these approaches have their place, uncertainty, divergence and distributed capacities are integral to many problems and cannot easily be swept under the carpet.

2) Do we know how these principles can be implemented?

There are some basic lessons about how aid agencies need to work that we do know: for example, putting less weight on ex ante planning processes and more resources and incentives behind ongoing management and monitoring to deal with uncertainty.

These lessons have been well-known for decades, the evidence for them is in reams of evaluations and reviews, but they still have not been taken up, perhaps because unlike tools like ‘New Public Management’ there are no comprehensive, ready-made models that can be picked up and applied. One major, multinational collaboration between academia and the public sector is working towards this, the New Synthesis Project, which aims to build a model of public policy and administration fit for complexity, but we are still some way off.

Beyond the basic lessons, there are a broad raft of tools that would promise to help policy-makers and programmers at different levels to incorporate various different complexity principles.

There is no shortage of offers: Owen Barder thinks complexity means we should all be doing problem-driven iterative adaptation; Duncan Green agrees to some extent; Nancy Birdsall reckons that complexity means we need Cash On Delivery aid; and the Institute for Government in the UK argues complexity means we should spend more time stewarding the relationship between policy-making and implementation. I have tried to summarise some of the key programming tools, and Richard Hummelbrunner and myself brought together two guides on planning in the face of complexity, and for managing interventions.

In other words a number of tools seem like they may be useful, but it is far too early to have the evidence to say X or Y is the big thing in complexity.

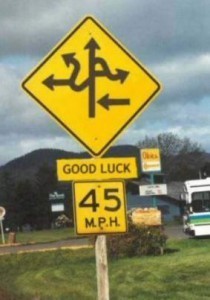

It's perfectly simple.....

So the answer to this question has to be: we have a number of ideas on how to adjust policy and programming, but no firm evidence on which is the most appropriate for which circumstances. In the principles outlined above we have a broad guide, but innovation is needed to go from principles to practice. People need to diagnose the levels and types of complexity faced in the different problems they are tasked with, and must judge best themselves how they can act on the corresponding principles in their situation.

3) What is the way forwards for complexity and development?

Given that we are clear on the principles of what needs to happen but less on the details, it is important to think about ‘process, not prescription’:

A. Embed principles in programme structures, don’t just take up analytical tools: The history of participation in development gives a precautionary tale on the importance of integrating principles and lessons into organisational structures and procedures (rather than just taking up new tools). The three principles outlined above need to be embedded in when, where and with whom decisions are made. As Daniel Ticehurst or will tell you about monitoring in the face of complexity, organisational structures and processes for monitoring are more important than the methods used to do the work.

B. Document practitioner and programming responses to complexity: The challenges of complexity are not new, but more could be done to review experiences of how people have tackled distributed capacities, divergent goals, and uncertain change processes, and what has worked where. A recent study by the Centre for Aid and Public Expenditure at ODI found complexity-type principles central to enabling aid programmes to foster institutional change and highlights ways in which they have incorporated principles such as adaptation and learning into existing agency structures.

From my own experience there is a great deal of innovation in governance programmes around how to identify and capitalise upon opportunities for change. More needs to be done to get at the tacit knowledge of practitioners – perhaps establishing communities of practice to facilitate ongoing learning around key principles and/or sectors.

C. Raise credibility with high-level decision-makers and HQ gatekeepers: To incentivise appropriate responses to complex problems simple measures could make a big difference, such as reduced requirements for ex-ante analysis (e.g. a more light touch ‘business case’ for DFID) combined with more incentives for adaptation (e.g. setting learning objectives for interventions and requiring evidence of lessons being taken on board) and results (e.g. Natsios suggests those who design programmes should be required to see them through in-country).

The opportunities to change these kind of policies are few and far-between, and are often the result of a political drive for reform combined with work by senior civil servants and staff working on ‘back office’ functions. The key to influencing this may be building the credibility of complexity at the top levels, and waiting for an opportunity when complexity ‘champions’ such as Owen and Ben might get their foot in the door.

senior civil servants and staff working on ‘back office’ functions. The key to influencing this may be building the credibility of complexity at the top levels, and waiting for an opportunity when complexity ‘champions’ such as Owen and Ben might get their foot in the door.

Ben Ramalingam’s new book (reviewed tomorrow) is an important milestone for complexity and development, and it is time for the debate to shift gears. The relevance of complexity and the basics of what need to be done to face it are relatively well-established, but it is unclear which are the best entry points for getting this done. There are good reasons why agencies have failed to take on simple lessons that have been known for decades, relating to their prevailing political and organisational incentives. While Matt Andrews is cautiously optimistic, It may be we have to find second-best solutions, e.g. David Booth recently argued that the best way to ensure aid is sufficiently adaptive and responsive is to place it at ‘arms length’ from the agencies themselves.

I cannot be at the book launch due to commitments here in Nepal, but if I could be in the audience I’d take the opportunity to press the panel on the way forwards. It is time to stop asking ‘what is complexity’ and ‘what does it mean for development?’, and instead now we have to ask: how can we integrate lessons into the way that aid works, and who will take the lead on this?

Should India be sending a rocket to Mars when 40% of children are malnourished? Vote now.

We interrupt complexity week with a quick question – what do you think about India’s Mars space project? The Indian Space Research Organisation today launches a rocket which it hopes will get to Mars before the Chinese space programme – BRICS in space.

Research Organisation today launches a rocket which it hopes will get to Mars before the Chinese space programme – BRICS in space.

Cue lots of outrage – in a country where 40% of children are malnourished and half the population have no toilets, wouldn’t the mission’s $70m budget be better spent on feeding the hungry? Or on fixing the energy system – more than 600 million Indians were hit this week by the world’s worst power cut.

And of course grist to the mill of aid opponents – how can we justify the UK’s tiny aid budget to an India that so misallocates its resources?

But then I got to thinking. Isn’t the opposition a bit reductionist – like saying poor people should spend all their cash on food and drink, and never have any fun, or celebrations, or ritual life of any kind? We’ve moved on from that, thinking about wellbeing and the multi-faceted nature of living in poverty (including not having enough fun). Remember cash for coffins?

So why shouldn’t that apply to countries too? The money is tiny ($70m is just a drop in the ocean of India’s welfare spending), and the impact on national identity, sense of possibility etc might be substantial, with unpredictable knock-on effects on governance, accountability etc.

So what do you think? Should India scrap its Mars mission and spend the money on reducing poverty and feeding the hungry? Vote now. (And yes I fully realize voting on this is just as daft as asking blog readers elsewhere to vote on UK or US government spending decisions, but I’m just interested in what you think).

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers