Duncan Green's Blog, page 206

September 24, 2013

Where are the examples of good donorship in complex systems?

Everyone loves a good scapegoat. When faced with trying something exciting, risky or new, the temptation is to say ‘they’ won’t let us. In the World Trade Organization I’ve heard developing country delegates argue that there is nothing they can do to stop the tide of imports, even when the WTO rules have lots of wiggle room to allow poor countries to protect their vulnerable communities (at the start of the now-dormant Doha round I was part of an attempt to develop and publicise that flexibility through the so-called ‘Development Box’).

Those WTO days came to mind in recent conversations about how to work differently in complex, unpredictable systems. Whereas accountability in simple predictable contexts can be demonstrated by reporting that you have done what you said you would do, accountability in complex unpredictable programmes is about ‘adaptive management’, tweaking the work as you learn more about the system in which you are working, or in response to events. As Keynes once said ‘“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

So much for the theory, but when discussing all this with the people who actually, you know, do stuff, I have been struck by how many of them say ‘this is all great, but the donors won’t allow it.’ Is that really true? At least sometimes, donors are not the problem; we (as in NGOs and other recipients of aid spending) are.

is all great, but the donors won’t allow it.’ Is that really true? At least sometimes, donors are not the problem; we (as in NGOs and other recipients of aid spending) are.

My favourite example is the Chukua Hatua programme in Tanzania, (which I’m visiting again in a couple of weeks – v exciting). DFID had set up the Accountability in Tanzania (AcT ) programme, managed by KPMG. They approached us and said (I paraphrase) ‘here’s £1m to do something innovative on accountability.’ But our first problem was that the Oxfam computer said no – it demanded all the usual outputs, outcomes etc, and for several months we had a problem even accepting DFID’s cash.

When we finally defeated the computer and took the money, we developed an evolutionary approach (try lots of things, consciously select the best and scale them up). But KPMG were not convinced by our theory of change. We had a bit of a wonk showdown between rival ToC nerds (I was Oxfam’s pointy head). They decided our ToC was fine, and got particularly excited when we described it as ‘developmental venture capitalism’, at which point they gave the project another £0.9m (never underestimate the importance of co-opting the right language).

Once convinced, someone from AcT became part of the project discussions – no more’them’ and ‘us’, and DfID started working with us on new ideas, such as getting citizens, especially women and youth, involved in the process of drafting a new national constitution (referendum February 2014). DFID has also adapted the model in Somaliland. So much for inflexible, box-ticking donors.

And elsewhere? Another of my favourite programmes, the Tajikistan Water and Sanitation Programme, relies on the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC)’s willingness to agree 10 year funding (much longer than the usual project timescale for what could easily be portrayed as a ‘talking shop’ (but has proved remarkably productive). Solutions emerge, in Matt Andrews style, from the forum, but cannot be foreseen and put into a standard funding proposal. The Swiss can live with that.

And elsewhere? Another of my favourite programmes, the Tajikistan Water and Sanitation Programme, relies on the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC)’s willingness to agree 10 year funding (much longer than the usual project timescale for what could easily be portrayed as a ‘talking shop’ (but has proved remarkably productive). Solutions emerge, in Matt Andrews style, from the forum, but cannot be foreseen and put into a standard funding proposal. The Swiss can live with that.

A quick email exchange with a few evaluation gurus produced some other thoughts:

It’s all about individuals: Ros Eyben’s work on how skilled aid workers learn to ride two horses (aid bureaucracy and real world) simultaneously applies here. Donor fund managers and others can either tick boxes, or use the flexibility that always exists within the rules. Regular contact with the partners on the receiving end can help them work out what needs to be done.

Confidence: If you aren’t sure of your ground, whether as donor or recipient, it’s much easier to play safe and tick the boxes. Assertiveness in suggesting changes to the plan is much harder – how do we support staff to acquire it? You’d think it would be easier for larger INGOs to push back, but only if their internal processes allow them to do so (see ‘computer says no’). And who is supporting smaller local organizations to be more assertive with donors?

Staff shortages and incentives: Ideally, the donor would accompany the programme on its power and change cycle, adapting reporting requirements as the programme evolves. But that runs up against some pretty big obstacles – it complicates the effort to prove value for money if cash donated for one thing is then used for another. But also the cult of low overheads means donor agency staff are under huge pressure to disburse large wads of cash, which leaves little time for getting to know and understand any one programme.

If we are to get better at working in the messy realities of complex economic, social and political systems, we have to take the donors with us. That means working with the good guys, being assertive, and collecting and amplifying examples of good donorship. Please add your own (only genuine candidates – please minimise the level of sucking up to donors!).

Or of course, we could always carry on behaving like Dilbert.

September 23, 2013

Is Inequality All About the Tails? The Palma, the Gini and Post-2015

Alex Cobham and Andy Sumner bring us up to date on the techie-but-important debate over how to measure inequality

Alex Cobham and Andy Sumner bring us up to date on the techie-but-important debate over how to measure inequality

It’s about six months since we triggered a good wonk-tastic discussion here on Duncan’s blog on how to measure inequality. We proposed a new indicator and called it ‘the Palma’ after Chilean economist Gabriel Palma, on whose work it was based. We suggested the Palma would complement, or perhaps even replace the (in our view) less useful Gini index. Here we bring things up to date with a look at inequality in the post-2015 debate, and present some further findings on the relative merits of Gini and Palma, based on our new paper.

First, post-2015 and all that.

Last week the Center for Global Development held an event in Washington DC to discuss the best income inequality measures for post-2015, with both a technical panel (video) comparing alternative measures, including the median, the Palma, the Commitment to Equity indicator and a multidimensional approach.

There was also a ‘user’ panel (video) with wonks from the IADB, IMF, Oxfam, UNICEF and the World Bank, discussing the policy need and the scope for implementation. While panelists and other participants did not agree on the idea of a post-2015 inequality goal or target (surprise, surprise), there was near unanimity on the importance of measuring income inequality, and doing so better than we do now.

That consensus, however, seems to be lacking in the intergovernmental discussion on post-2015. There appears to be broad support for a focus on economic inequality from Latin American representatives, but more patchy support elsewhere. At the CGD event, Nancy Birdsall highlighted that, to the extent that governments reflect elite interests, there may not (yet) be a political consensus; but that there is instead a “people’s consensus”, with inequality riding high on the agenda of popular concern in countries at all income levels.

Whether this can be translated into more effective political support is unclear, though Oxfam and Save the Children are working on building that political consensus.

But back to feeding the wonks (and remember skimming the next section will save you from having to read the actual paper).

Our new paper, released to coincide with the event, makes three main points (we’re told always make three points – never more, lest people’s heads explode …).

First, inequality measures for policy frameworks such as post-2015 must be considered on the basis of policy criteria, not only the common technical criteria – in other words, we need to think about whether measures are useful for policy processes, not only whether they exhibit certain mathematical properties. A technically perfect measure which is unintelligible to most people (or which requires significant explanation) is highly unlikely to form the basis for policy-maker accountability. So we propose five policy axioms (bear with us):

That the value judgments of using this indicator are sufficiently explicit.

That it is clear what signal is being given to policymakers on the preferred direction of change of inequality (improving or worsening).

That it is clear to a public (ie non-technical) audience what has changed and what it means.

That the policy response is sufficiently clear to policy-makers (meaning how policies do or do not influence the indicator).

That it is possible to capture horizontal (e.g. gender and ethno-linguistic group) as well as vertical inequality in the indicator.

So, what? We think the Palma, which is the income share of the top 10% divided by the income share of the poorest 40% , is much more meaningful to policy makers and otherwise normal people, than the Gini and Theil measures, which are both relatively obscure statistical constructs.

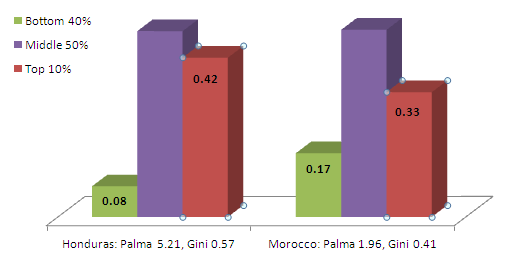

Second, income inequality is in ‘the tails’ (the rich and the poor). That is, most of the difference when you compare countries, or the same country over time, is in what happens at the top and bottom of society rather than in the middle. For example, the middle 50% of the population have about half of national income in both Honduras and Morocco; but the poorest 40% in Morocco have more than twice the share of national income as in Honduras, and the top 10% correspondingly less (see figure below).

In the new paper we provide substantial new evidence for Gabriel Palma’s finding that the ‘middle’ 50% of the population, defined as households in the 5th to the 9th deciles, has a strikingly stable share of national income (around 50% in fact) – not only in countries at different income levels, but in any given country over time, and in addition through the fiscal stages of taxation and transfers. This demonstrates very clearly that inequality is about how much the rich (the top 10%) and poorest (the bottom 40%) get, or what are known as ‘the tails’.

In the new paper we provide substantial new evidence for Gabriel Palma’s finding that the ‘middle’ 50% of the population, defined as households in the 5th to the 9th deciles, has a strikingly stable share of national income (around 50% in fact) – not only in countries at different income levels, but in any given country over time, and in addition through the fiscal stages of taxation and transfers. This demonstrates very clearly that inequality is about how much the rich (the top 10%) and poorest (the bottom 40%) get, or what are known as ‘the tails’.But the Gini is overly sensitive to the middle of the distribution, so it is not well equipped to address this type of inequality – while the Palma is designed to do just that.

Third – and this is a bit technical – a criticism of the Palma: that it relies only on two points of the distribution, and so ignores too much information about inequality. We show that in regression analysis (bear with us), the same two points of the distribution (i.e. the income shares of the top 10% and bottom 40%) can perfectly explain the Gini – so that in practice it contains no more information than does the Palma.

The difference is that while the Palma is the simple ratio of the two, the Gini has the following form:

Gini = (0.581 * income share of top 10%) – (1.195 * income share of bottom 40%) + 0.419

Hardly intuitive to the person in the street, eh?

Palma's the one with the beard

In practice, the Ginis that are used in much analysis contain no more information than the Palma, but the Palma is transparent about this, and we think intuitively clear – take what the rich get and divide it by what the poor get.

As we said when presenting the Palma last week, we’re not trying to completely replace the Gini, just saying that the Palma has something to add that is understandable to more people.

Our view is that multiple measures should be used to monitor income inequality for policy purposes – including not only the Palma but also, for example, the median income; and if you must, the Gini.

But if one measure alone is to be used: please don’t let it be the Gini.

Alex Cobham is a Research Fellow at the Center for Global Development.

Andy Sumner is Co-Director, King’s International Development Institute, King’s College London

September 22, 2013

Investments to End Poverty launched today: a goldmine of killer facts and infographics

Today sees the launch of the killer fact-tastic inaugural Investments to End Poverty report by Development Initiatives. The report makes the case for aid as an essential part of ‘getting to zero’ on absolute poverty by 2030, but as is increasingly the norm, the report locates aid among the much wider issue of development-related resource flows, both domestic and international. In speed reading mode, I have not yet read the full 330 page monster, but an advance peak at the 10 page ‘highlights’ document provides a goldmine of stats and infographics for many other purposes into the bargain. Some of the ones that jumped out at me:

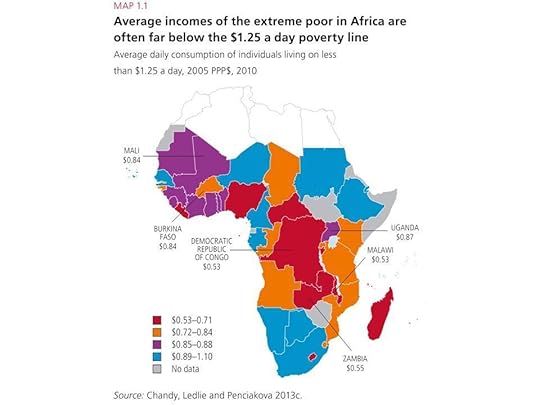

Depth of African Poverty (see map)

Government spending in developing countries is now $5.9 trillion a year. More than half of all developing countries have seen government spending grow at an average of over 5% a year between 2000 and 2011. For the remainder, average annual growth in government spending has been 2.5%.

The scale and diversity of resource flows to developing countries has increased rapidly. The volume of international resources received by developing countries has more than doubled since 2000, reaching an estimated US$ 2.1 trillion in 2011.

Resources also flow out of developing countries. Of the $472 billion in foreign direct Investment into developing countries, $420 billion flowed out as repatriated profits.

Official development assistance remains important. ODA remains the main international resource for countries with government spending of less than PPP$500 per person a year.

Nice annotated graph of aid flows 1960-2012 (see below)

Developing countries do not always receive what a donor reports as allocated. The headline

Developing countries do not always receive what a donor reports as allocated. The headline  amount of aid reported as disbursed by donors (including investment in global public goods) is much bigger than the amount developing country governments control and can directly administer. (See Uganda example – the discrepancy is explained in the main report as due to the published figure including debt relief, administrative costs, transaction costs (such as shipping costs of food aid) and because some aid doesn’t go through government books, because it goes directly to other bodies like NGOs and/or the government knows nothing about it).

amount of aid reported as disbursed by donors (including investment in global public goods) is much bigger than the amount developing country governments control and can directly administer. (See Uganda example – the discrepancy is explained in the main report as due to the published figure including debt relief, administrative costs, transaction costs (such as shipping costs of food aid) and because some aid doesn’t go through government books, because it goes directly to other bodies like NGOs and/or the government knows nothing about it).

spending within the donor country

And here’s Development Initiatives guru Judith Randel doing the increasingly obligatory 4m piece to camera

September 20, 2013

What can the aid business learn from Google v Death?

Benjamin Franklin famously said ‘nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes’. Google begs to differ. On both. First it becomes a byword for tax avoidance, and now it’s taking on death too, according to

Benjamin Franklin famously said ‘nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes’. Google begs to differ. On both. First it becomes a byword for tax avoidance, and now it’s taking on death too, according to an article on Time Magazine’s techland blog.

an article on Time Magazine’s techland blog.

Time interviewed Google CEO Larry Page on the latest in a growing line of bonkers innovative activities (Google glasses, driverless cars etc).

‘Page prefers to refer to Google’s more out-there ventures as moon shots. “I’m not proposing that we spend all of our money on those kinds of speculative things,” he says during a rare interview at the Googleplex, the company’s Mountain View, Calif., headquarters. “But we should be spending a commensurate amount with what normal types of companies spend on research and development, and spend it on things that are a little more long-term and a little more ambitious than people normally would. More like moon shots.” This is why Google, in Page’s words, is not a normal type of company.’

Now, Google has founded Calico, a company dedicated to finding ways to extend human lifespan. Yep, it’s Google v Death. A kind of high tech King Canute, turning back the tides of mortality.

‘Google isn’t exactly bursting with credibility in this arena. Its personal-medical-record service, Google Health, failed to catch on. But Calico, the company says, is different. It will be making longer-term bets than most health care companies do. “In some industries,” says Page, “it takes 10 or 20 years to go from an idea to something being real. Health care is certainly one of those areas. We should shoot for the things that are really, really important, so 10 or 20 years from now we have those things done.”

What struck me was the echo with some conversations in Australia last week, on the need for aid agencies to consider their operations as a ‘risk portfolio’. If we think that innovation is important, then who is thinking 20 years ahead? And among aid agencies, whether official donors or large NGOs and foundations, should we be more explicit in seeking a balance between safe bet activities and high risk/high return moonshots? I fear that currently we try to minimise risk on each separate activity, producing an overall portfolio skewed towards the conservative and low risk/low innovation end.

I imagine that one answer likely to come back is that tech research (CGIAR, vaccines etc) is the 20 year piece of the puzzle, but what about other crucial areas of development where we need big new ideas, such as governance, fragile states, tackling inequality, violence against women etc. Who is doing a Google there?

To give it a go, we would also need the backing of funders, of course (and it’s always easy to avoid taking risks by saying ‘the donors will never wear it’). Is anyone (implementer or funder) taking this approach in the aid business?

What else can we learn from Google? Some thoughts:

Stealing/borrowing ideas from smaller, more nimble organizations: Goliaths like Google often innovate by gobbling up promising-looking start-ups. In the development business, such acquisition is not really recognized as a legitimate activity, and may even be seen as theft. But when I worked as a policy wonk for CAFOD, one marker for success was to have my policy idea adopted by either Oxfam or the UK Treasury.

Stealing/borrowing ideas from smaller, more nimble organizations: Goliaths like Google often innovate by gobbling up promising-looking start-ups. In the development business, such acquisition is not really recognized as a legitimate activity, and may even be seen as theft. But when I worked as a policy wonk for CAFOD, one marker for success was to have my policy idea adopted by either Oxfam or the UK Treasury.

Why don’t large NGOs make this more explicit – the end of year performance review includes a question ‘what good ideas or practices have you stolen in the last year?’ And for smaller ones, ‘what extra leverage have you acquired by selling your bright idea to a larger organization?’

Google is also famous for its “20% time,” which allows employees to take one day a week to work on side projects. (Although please note, it is now being accused of dumping that commitment.) In contrast aid agency staff seem to take a perverse pleasure in showing that their existing work commitments add up to 120%. Time for HR departments to get googling?

Anything else we can learn from the Googlemonster?

September 18, 2013

Working in Fragile States, as seen from Australia and New Zealand

I’m currently nearing the end of my three weeks in Australia and New Zealand. These trips typically involve several meetings a day with government officials, politicians, NGOs and journalists. The to and fro produces a churn of topics and ideas, out of which emerge some themes, but you never know in advance which ones are going to dominate.

government officials, politicians, NGOs and journalists. The to and fro produces a churn of topics and ideas, out of which emerge some themes, but you never know in advance which ones are going to dominate.

This time around it has been fragile states. These form a big focus for the Aus and Kiwi aid programmes, which see themselves as surrounded by a ‘ring of fragility’ in the form of the Pacific islands of Melanesia (Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji). In the smaller islands aid, overwhelmingly from Aus/NZ, can be up to 50% of the government budget, raising big questions about the political impact of aid – does it, like oil or mining, inhibit the creation of a social contract by removing the link between citizens and states normally provided by taxation?

Many states are artificial constructs of decolonisation, created as recently as the 1970s. There has been little time for state institutions to evolve. Citizens feel connected primarily to their family, clan or island, but not to what often feels like the artificial construct of the nation state. The result looks messy – informal institutions sitting alongside grafted-on fragments of Westminster-style institutions, a disillusioned citizenry, lots of patronage and corruption, laced with endemic violence against women. Just to make shaky institutions worse, a resource boom has hit several countries.

For many years, aid agencies tried a state-centred approach, with lots of cash going into trying to build government systems, but few results. Now, they’re beginning to doubt the value of this and wondering what else to try. Luckily, AusAID has commissioned some impressive research on this via the Development Leadership Programme and State, Society and Governance at ANU, so it has some good ideas to test.

But there is also a hankering among donors to play a more direct role in service delivery, born of frustration and impatience. This attempt to find a short cut to development appears to have no overall idea of how it is building (or I would argue weakening) the institutions needed to deliver services in the long term (see this discussion on Collier’s Independent Service Authorities).

What else is worth trying? Here are my thoughts after a couple of weeks of conversations:

Outsiders should focus on identifying and investigating problems, but then step back and get local players together to seek solutions (see Matt Andrews on problem-driven iterative adaptation).

In many situations $10,000 can really help, whereas $10 million massively distorts systems, creates perverse incentives and generally messes things up. How to ‘politically sterilize’ such inflows? One option is breaking the big chunks down into lots of smaller ones, but that can be very demanding on staff time.

Another is cash transfers. These can either be the traditional variety – to individuals or households, sometimes conditioned on things like keeping kids in school. But AusAID has an interesting line in what I call community cash transfers – transfer medium sized chunks of money ($50k) to villages, to fund either whatever they want to do (Afghanistan National Solidarity Program) or something chosen from a menu of options (PNPM in Indonesia, or AusAID’s current plans in East Timor). This approach may do more for community cohesion than individual cash transfers. Scott Guggenheim, an AusAID legend who has been described as a ‘one man Global Public Good’, seems to be behind a lot of this stuff.

Another is cash transfers. These can either be the traditional variety – to individuals or households, sometimes conditioned on things like keeping kids in school. But AusAID has an interesting line in what I call community cash transfers – transfer medium sized chunks of money ($50k) to villages, to fund either whatever they want to do (Afghanistan National Solidarity Program) or something chosen from a menu of options (PNPM in Indonesia, or AusAID’s current plans in East Timor). This approach may do more for community cohesion than individual cash transfers. Scott Guggenheim, an AusAID legend who has been described as a ‘one man Global Public Good’, seems to be behind a lot of this stuff.There are several alternatives to banging your head on a weak or parasitic national state – working with local state bodies, as we do in the DRC, for example. Or with city-level authorities. Or focussing on non-state centres of power, such as faith organizations or emerging urban middle classes. In the otherwise chaotic highlands of Papua New Guinea, Oxfam has developed enough on-the-ground presence to identify and support community leaders (without throwing too much money around). Livelihoods work such as helping farmers get organized can also create nuclei for future citizens’ movements.

In Australia, Oxfam has done interesting work supporting Diaspora communities, eg Darfuris, to develop their ability to do advocacy back home. Diasporas have money, contacts and knowledge – the question is what, if anything, western governments or INGOs can do to help them.

And a few comments on what not to do

Parallel provision without any idea of how to hand over to the state in the long term (back to Paul Collier)

Deficit thinking: this is where outsiders identify ‘deficits’ in governance or accountability, and try and fill them. Deficit-thinking often

incorporates assumptions about where institutions ‘should’ be ending up. Typically, this looks something like Western parliamentary democracy and a Weberian model of an efficient independent state bureaucracy, when the reality in many Pacific islands is a more horizontal network of nodes of power – money, traditional leaders, bits of the formal state, churches, NGOs, aid agencies, China.

incorporates assumptions about where institutions ‘should’ be ending up. Typically, this looks something like Western parliamentary democracy and a Weberian model of an efficient independent state bureaucracy, when the reality in many Pacific islands is a more horizontal network of nodes of power – money, traditional leaders, bits of the formal state, churches, NGOs, aid agencies, China.Try not to invade – DFID’s fragile states research found a very poor record of state-building following external intervention.

Lots more to say on the topic, not least the link to complexity thinking, but this post is already too long, so over to you and the comments section.

One final thought – as I was writing this, news came through that AusAID is being absorbed back into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, in addition to the new Aussie government freezing aid spending in real terms (and cutting it this year). I really hope this doesn’t endanger their cutting edge research and programming on fragile states – we need all the help we can get on this.

September 17, 2013

World order on developmental see-saw

This piece (not my title btw) appeared on Tuesday in Wellington’s newspaper the Dominion Post, as I wrapped up three weeks’ intensive ranting in Australia and New Zealand.

Australia and New Zealand.

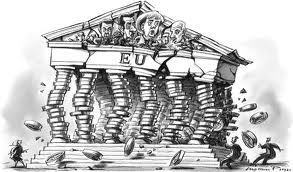

Bloodbaths in Syria and Egypt; banking crises and austerity; the rise of the “emerging powers” and the apparently unstoppable decline – perhaps even disintegration – of Europe: the past five years has been a period of extraordinary global turbulence.

The global financial meltdown was a watershed event. The new world order was recognised as the G20 took over from the G8.

The crisis drew attention to the risks of an excessively “financialised” global economy, but failed to lead to a reining in of the excessive size and volatility of “hot money”, condemning us to future financial crises.

International aid agency Oxfam has witnessed the destruction caused by austerity and recession in parts of Asia, Latin America and Africa, as well as here in New Zealand.

Simultaneous with the financial crisis, the world experienced a spike in food prices, ending 30 years of stable and falling prices. In many countries this traumatised the lives of poor people to a much greater extent than the mayhem on Wall Street, threatening long-term progress on hunger and nutrition. That has led to renewed attention to the basic issues of food and farming, but also some unfortunate side-effects such as “land grabs” by investors from rich countries.

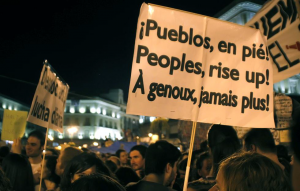

The Arab Spring confirmed the importance of active citizens in driving social and political change, but it also showed us that when it comes to social change, good starts can easily go wrong..

Taken together, these events have had a profound impact on the way we see international development. We are much more aware of the impact of volatility, risk and vulnerability on the lives of poor people.

Inequality and redistribution have become mainstream debates, with even the International Monetary Fund weighing in on how high levels of inequality imperil both growth and stability. And the levels are breathtaking. I calculated that the amount the world’s richest 100 people added to their wealth in 2012 (NZ$295 billion) would be enough to end extreme poverty (NZ$81 billion according to the Brookings Institution) four times over.

There are more than 1.2 billion people living below the international poverty line of NZ$2.25 a day. So if we altered the lives of the world’s richest 100 people slightly, we could change the lives of 1.2 billion people monumentally.

In overcoming world turbulence, and continuing the upward curve of human development that has characterised the last 70 years, we need to move “from poverty to power” in both thinking and practice. Oxfam’s experience suggests that the key lies in a combination of active citizens and effective states.

In overcoming world turbulence, and continuing the upward curve of human development that has characterised the last 70 years, we need to move “from poverty to power” in both thinking and practice. Oxfam’s experience suggests that the key lies in a combination of active citizens and effective states.

Why active citizens? Because people living in poverty must have a voice in their own destiny, fighting for rights and justice in their own society, and holding the state and private sector to account.

Why effective states? Because history shows that no country has prospered without a state that can actively manage the development process in terms of infrastructure, rule of law, human capital and industrial upgrading.

Are we successfully completing an “age of development” or seeing the prize slip from humanity’s hands in an economic and climatic meltdown? It is hard to recall a period when developmental optimism and pessimism co-existed to such a high degree.

The stakes could not be higher. The coming decades will show whether poverty enters the history books, joining slavery and the fight for women’s suffrage, or whether an age of chaos and scarcity starts to reverse the progress of the last 70 years.

September 16, 2013

This will make your day. Especially if you are a humanitarian with fantasies of being the subject of a rock anthem.

I really should be writing something more intelligent, but this video has destroyed any hope of that. Jan Egeland, a Norwegian Labour party politician, was the United Nations Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator from 2003-2006. He is currently Secretary General of the Norwegian Refugee Council. But most importantly, he is the subject of this wonderful video – half homage, half piss-take, and wholly hilarious. Valerie Amos next? [h/t Wronging Rights, which also has a bit of background]

Why is football such a successful (and replicable) institution?

My visit to Australia and New Zealand has been full of discussion of fragile states – how might durable, effective, accountable institutions

Institutional Entrepreneur

emerge in the Pacific islands that are the focus of much of the aid (and thinking) here?

I’ll need time to process those conversations, but in the meantime, here’s a more immediate question, raised in a conversation with Ausaid’s governance guy, Steve Hogg. Why is football such a brilliant and replicable institution?

Think about it. Institutions are often defined as ‘the rules of the game’. The work of Matt Andrews, ODI and an increasingly large phalanx of other researchers argue that such rules have to emerge from local context. You can’t use a cookie cutter to graft Westminster democracy or any other institution onto poor countries.

Except for football (OK, soccer, for some of you). Now there is a perfect universal set of ‘rules of the game’. In fragile states such as Papua New Guinea, few people accept Western notions of governance, but they all accept the offside rule. A single set of rules is followed apparently by grassroots and elite alike in more or less every country in the world. Why is that?

Some hypotheses for you to shoot down

- The incentives are brilliantly aligned – you can’t play soccer without everyone agreeing to abide by the rules. When someone insists on violating them (think William Webb Ellis picking up the ball and running with it) the challenge to the institution is so profound that a whole new institution (rugby) is born.

- The rules are enforced both collectively and by the players themselves (just listen to the arguments in the local park kick about)

- There is a collective acceptance (sort of) of an arbiter – the referee

- They individual rules are not simple (ever tried to explain the offside rule?), but there are relatively few of them, compared even to a game of rugby, let alone running a government. Maybe soccer is the ultimate social franchise….

Some arguments that definitely don’t explain football’s success compared to other institutions

Absence of corruption (FIFA, match-fixing, dodgy transfer deals and the rest)

Efficient international governance (FIFA again), but there is a way for the offside rule to evolve globally (but not at national level) along as the game changes. That makes for interesting comparisons with more rigid international institutions such as different faith groups, which often have a lot more trouble accepting change (gay and women priests?).

But I feel like I’m missing a lot here, so over to you. What are the secrets of football’s replicability, and can they be applied to (with apologies to soccer fans) more important stuff?

September 12, 2013

A few impressions of an intense two weeks in Australia

under new management....

snapshots. First up was teaching a 3 day module on How Change Happens with , to 14 students in Murdoch University’s development studies Masters programme. The students were a brilliant international mix and teaching as a tag team was great fun; after day one we threw away our course outline and improvised from then on – I think we may have the basis for a really useful power and change course – more to follow. Culinary highlight in Perth – emu and chips. Like steak, but subtler flavour. Yummy.

Flew to Melbourne on election day, as the Liberal National Coalition party (roughly comparable to British Tories) won their expected landslide. The mood was reminiscent of the UK election in 2010. Most memorable impression of election night was not Kevin Rudd’s distinctly odd concession speech (he sounded like he’d actually won, and then suddenly resigned), but the horrible car crash fascination (there but for the grace of God etc…) of this earlier interview with Liberal candidate James Diaz. He was virtually the only Liberal candidate to lose votes, which at least shows voters were listening. More to follow on the implications of the change in government for Australian aid.

After various meetings in Melbourne with Oxfam Australia, Chris Roche gave me a good public grilling at a book launch (‘so, you once blogged that you wouldn’t speak on all male panels – why are you here?’) which seemed to amuse the audience and boost sales (book store guy passing me books to sign ‘best sales since Rupert Everett’……). Might make ritual public humiliation a standard sales tactic from now on.

Then off to Canberra for an intense two days with AusAID and ACFID, the Australian development NGO network. Confusion and anxiety over the Liberal decision to cut aid and freeze spending at the same real term levels over the next four years, rather than the previously planned large increase (already twice delayed by the Labor Party).

Main impression there was just how much thinking they are doing on fragile states, which is where a large part of Australian aid goes – a ring of fragility in the Pacific, with Papua New Guinea perhaps most prominent in the discussions. Australia sees itself as a massive big brother to the Pacific Islands, and is sometimes the only donor. I was hosted by Steve Hogg, an AusAID governance specialist who was raised in PNG, and who set up the excellent Development Leadership Program with Adrian Leftwich. Steve hosted a series of intense conversations with advisers on the role of aid agencies in fragile states – posts to follow on that.

Final random impressions? Development Studies seems alive and well in Aussie universities – lots of really interesting research going on; don’t talk about the cricket (or the rugby, or the Olympics, although my Oxfam Australia minder insists I link to this); Aussie birds can’t sing – they just croak or make weird flutey noises (all night) – but they look (and taste) great.

talk about the cricket (or the rugby, or the Olympics, although my Oxfam Australia minder insists I link to this); Aussie birds can’t sing – they just croak or make weird flutey noises (all night) – but they look (and taste) great.

More considered posts to follow on lots of these topics. Great to meet so many FP2P readers while here (including apparently the whole of AusAID) – thanks for all the encouragement.

September 11, 2013

How does Europe’s crisis look through the eyes of an international aid agency?

Back in 1942, during World War Two, Oxfam came into existence to lobby the British Government to ease the allied blockade of Nazi-occupied Greece. 70 years and a European miracle later, might we be once again about to send aid teams to Athens? I’m sitting in Australia as I write this, and it feels like I can almost see Europe shrinking and sliding backwards.

An Oxfam report published today stands back and looks at the state of Europe, seen through the eyes of an international agency that has witnessed the impact of crisis and austerity in dozens of developing countries in recent decades. For Europeans, it doesn’t make happy reading.

witnessed the impact of crisis and austerity in dozens of developing countries in recent decades. For Europeans, it doesn’t make happy reading.

This from the executive summary (and yes I have read the rest, at least in draft….):

“Europe has often seen itself as a place where the social contract balances growth with development. A place where public services aim to ensure everyone has access to a high-quality education and no one need live in fear of falling ill. A place where the rights of workers, and particularly of women, are respected and supported, and where societies care for the weakest and the poorest; where the market has been harnessed to benefit society, rather than the other way round.

However, this idyllic social model has been under threat for some time; income inequality was increasing in many countries even before the financial crisis began. Now, the European model is under attack from ill-conceived austerity policies sold to the public as the cost of a stable, growing economy, for which all are being asked to pay. Left unchecked, these measures will undermine Europe’s social gains, creating divided countries and a divided continent, and entrenching poverty for a generation.

The unprecedented bailout of Europe’s financial institutions may have saved its banking system, but it also significantly increased public debts. They assumed that austerity policies – singularly focused on balancing budgets and reducing deficits – would restore market confidence and ultimately lead to job creation and renewed economies. In most countries, this has not happened. After almost three years, austerity is failing on its own terms and continues to exact high social costs. The experiences of the UK, Spain, Portugal, and Greece shows that the harsher the austerity, the higher the increase in debt ratio. A blind focus on reducing debt above all else has ignored the fact that growth can still occur during relatively high levels of debt and that any new growth in the economy must be inclusive and for the benefit of all.

Austerity programmes implemented across Europe – based on short-sighted, regressive taxes and deep spending cuts, particularly to public services, such as education, health and social security – have dismantled the mechanisms that reduce inequality and enable equitable growth. The poorest have been hit hardest, as the burden of responsibility for the excesses of past decades is passed to those most vulnerable and least to blame. Now, leading proponents of austerity, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), are beginning to recognize that harsh austerity measures have not led to the expected results, and have harmed both growth and equality.

European nations are suffering record levels of long-term and youth unemployment, with a generation of young people facing years of joblessness to come. As the real value of average incomes continues to plummet, falling fastest in countries that have implemented aggressive spending cuts, even those in work can look to a future where they are significantly poorer than their parents. Almost one in 10 working households in Europe now lives in poverty.

Oxfam has seen the impact of austerity measures before.

Oxfam has seen the impact of austerity measures before.

In 2011, 120 million people across the EU faced the prospect of living in poverty. Oxfam calculates this could rise by at least 15 million, and by as much as 25 million, as a result of continued austerity measures. Women will be the hardest hit. All the while, the richest have seen their share of total income grow, as the poorest are seeing theirs fall. If current trends continue some countries in Europe will soon have levels of inequality that rank among the highest in the world.

Throughout Oxfam’s history it has campaigned not just to highlight poverty and suffering, but, just as importantly, to highlight the policies and politics that are creating this poverty. Oxfam can no longer stand by while such poverty and suffering are being created in Europe, and, through falling European aid budgets and lower consumer spending, all over the world.

The European experience bears striking similarities to the structural adjustment policies imposed on Latin America, South-East Asia, and sub-Saharan African in the 1980s and 1990s. Countries in these regions received financial bailouts from the IMF and the World Bank after agreeing to adopt a range of policies including public-spending cuts, the nationalization of private debt, reductions in wages, and a debt management model in which repayments to creditors of commercial banks took precedence over measures to ensure social and economic recovery. These policies were a failure; a medicine that sought to cure the disease by killing the patient.

As part of global civil society, Oxfam fought hard against these policies, which forced the pain of economic slowdown on to those least able to bear it. Structural adjustment policies led to stagnating incomes and rising poverty in many countries, scarring generations across the world. Poverty in Indonesia took 10 years to return to pre-crisis levels. In Latin America, the incomes of ordinary people were the same in the mid-1990s as they had been in 1980. Vital services, such as education and health, were cut back or privatized, excluding the poorest and particularly harming women. Meanwhile, the share of income of the richest in society increased rapidly.

In spite of this cautionary tale, austerity is being aggressively pursued in Europe, with scant regard for the lessons of the past. These lessons suggest a bleak future for Europe’s poorest people, and warn of the harmful impacts for society as a whole.

Recommendations

An additional 15 to 25 million people across Europe could face the prospect of living in poverty by 2025 if austerity measures continue. It could take between 10 to 25 years for poverty to return to pre-2008 levels in Europe.

It does not have to be this way. Oxfam calls on European governments to do more than merely adjust existing austerity measures.

European governments must:

Invest in people and economic growth:

Invest in public services

Strengthen institutional democracy

Build fair tax systems

Oxfam is proud to stand with civil society in envisaging a new model of prosperity built on social justice and environmental sustainability.”

Glad we’re saying this …..

You can read the full report at: www.oxfam.org.uk/austerity

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers