Duncan Green's Blog, page 207

September 10, 2013

How are the emerging donors (from China to Azerbaijan) changing the aid business?

Oxfam’s ‘BRICSAM

IT’ group (BRICS + Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey) is now up and running and doing some innovative thinking about the role of the emerging powers, including their role as donors. Here Russia/CIS regional researcher

Daria Ukhova

(right) explores recent developments.

the emerging powers, including their role as donors. Here Russia/CIS regional researcher

Daria Ukhova

(right) explores recent developments.

While the eyes of many international aid observers are currently on the BRICS bank (already discussed in this blog), another trend has yet to get much attention. In the last two years, several emerging powers have either opened or announced plans to establish their own international development agencies (or similar administrative units). They include:

- Mexican Agency for International Development Cooperation (AMEXID) (September 2011);

- India’s Development Partnership Administration (January 2012);

- South African Development Partnership Agency (SADPA) (was expected to become operational in 2013, and is likely to begin work in September 2013);

- fivefold increase of the budget and expansion of the mandate of the Russia’s Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States, Compatriots Living Abroad and International Humanitarian Cooperation (Roscooperation) in May 2013;

- possible ‘re-establishment’ of the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC) / creation of a new development and cooperation agency (announced in late May 2013 by President Rousseff).

It’s not just the BRICS, or even the ‘next 11’ or the CIVETS. Azerbaijan opened its international development agency, AIDA, in September 2011.

The trend is not completely new: some Gulf states and Turkey opened their agencies many years ago. Nor is it uniform: China – one of the largest donors in the group – has not yet consolidated its development assistance under the umbrella of a single agency, although it is strengthening its coordination of aid efforts. As the first White Paper on China’s Foreign Aid (2011) explained, the Ministries of Commerce, Foreign Affairs and Finance established a foreign aid inter-agency liaison mechanism back in 2008 and upgraded it into an inter-agency coordination mechanism in February 2011.

That said, the trend is clear, and raises several questions.

Why? Why now? Most of the ‘emerging’ donors have assistance programmes stretching back to the 1950s. So, why have so many of them decided – quite recently and rather simultaneously – to institutionalise their aid efforts? On the one hand, this could simply be a response to the need to effectively manage significantly increased aid volumes in recent years. Moreover, DFID, the World Bank, UNDP, USAID, etc. have recently supported projects aimed at institutionalising several countries’ aid efforts.

On the other hand, this ‘trend’ is also a sign of the emerging donors’ aspirations to a stronger position in the multi-polar world, giving moreweight to their philosophies and modalities of aid giving. Are we witnessing a deliberate attempt to shift the centre of gravity of the global aid business? The establishment of these new institutions signifies that providing aid will no longer be ad-hoc; instead, as was once the case with the traditional donors, international development aid and humanitarian response are becoming substantial parts of the foreign policy of emerging powers.

On the other hand, this ‘trend’ is also a sign of the emerging donors’ aspirations to a stronger position in the multi-polar world, giving moreweight to their philosophies and modalities of aid giving. Are we witnessing a deliberate attempt to shift the centre of gravity of the global aid business? The establishment of these new institutions signifies that providing aid will no longer be ad-hoc; instead, as was once the case with the traditional donors, international development aid and humanitarian response are becoming substantial parts of the foreign policy of emerging powers.

What’s old and what’s new about these new agencies? Are the ways in which these new agencies will operate significantly different from those of ‘traditional’ donors? It is too early to draw hard conclusions, because some of these agencies have not even started operating yet, but several distinctive traits already stand out:

Principles of South-South cooperation at the core. All the agencies – except the Russian one – have openly proclaimed South-South cooperation as their founding principle. Roscooperation’s strategy is being formulated at the moment, but the agency is viewed by the authorities primarily as a tool of ‘soft power’ to advance Russia’s interests abroad and raise its profile as a donor. We still need to wait and see, however, whether and how the rhetoric translates into the programme activities of the new agencies.

Thinking regionally. All the agencies are expected to focus their efforts at the regional level and also, in the case of Brazil and India, on Africa.

As in most traditional aid donors, these new agencies have close ties with ministries of foreign affairs. But in some of the new donors, such as Brazil, ties with the Ministry of Development, Industry and Commerce are increasingly important. Whether this kind of move would be reproduced in the other countries remains a question, but Brazil’s example does signify increasing blurring of the distinction between aid and investment, and we can expect that the form that the new agencies eventually take will reflect this.

Interestingly, while most of the agencies manage/plan to manage both multilateral & bilateral aid (similar to traditional donor agencies), in Russia, the agency’s role will be confined to dealing exclusively with bilateral projects. Russia aims to increase the share of bilateral aid in its overall aid and thus to increase its visibility as donor. (Until recently, Russia’s bilateral aid had a miniscule share, since aid was managed primarily by the Ministry of Finance, largely consisting of contributions to the UN bodies.)

It seems likely that triangular cooperation, which, for example, Brazilians are already following with USAID in Africa, will be

emphasised at least in some of the new agencies’ strategies (e.g. triangular co-operation is part of SADPA’s strategic orientation).

emphasised at least in some of the new agencies’ strategies (e.g. triangular co-operation is part of SADPA’s strategic orientation). Some of the new agencies (e.g. AMEXCID) have already shown great interest in partnering with the private sector – a trend, which is clear also among the traditional donors. The private sector has its own Technical Council at AMEXCID.

Finally, while creation of the agencies could be considered as a step towards improving the measurement and monitoring of effectiveness of aid coming from the new donors, it is still not clear what kind of practices will underpin this. Will the new agencies be following the fads of the traditional donors, e.g. results agenda, RCTs, etc.? Or will they come up with alternatives?

How (if at all) can CSOs influence the policies of the new agencies? That’s probably the most pressing question for us at Oxfam and for our NGO colleagues.

In India, the Development Partnership Administration has supported the creation of the Forum on Indian Development Cooperation (FIDC), in which Oxfam participates. This provides a space for civil society to directly engage with DPA officials on issues such as transparency and accountability.

In Mexico, the Law on International Development Cooperation includes the participation of CSOs in the Advisory Board of the new agency, but does not grant them a right to vote. Under former president Calderon’s administration, a number of CSOs were invited to form a Technical Council to advise the Executive Director and the Advisory Board of AMEXCID. Along with other 11 CSOs, Oxfam accepted. However, CSOs’ involvement depends on the political will of the government, and there have been no follow-up meetings under the current administration.

With this newly opening space the question that, however, remains is how much interest do national CSOs actually have in their own governments’ aid programmes? And how does it affect the relationship of international NGOs like Oxfam with the national CSOs?

What’s the ‘bigger meaning’ of the ‘new agencies’? The decisive entry of these new donors is likely to create/exacerbate a competition among traditional donors and emerging powers, with each side claiming that their brand of aid benefits the poor more and brings ‘real’ development. That in turn prompts some bigger questions. How to distinguish between a propaganda war and real concern for equality and  the interests of poor people? Is this competition a good or a bad thing for the poor? What can civil society do in order to protect the rights of the excluded and the poor in this fast changing environment?

the interests of poor people? Is this competition a good or a bad thing for the poor? What can civil society do in order to protect the rights of the excluded and the poor in this fast changing environment?

To conclude, we are clearly witnessing an important and potentially transformatory development in the international aid landscape. To understand what exactly is going to happen and the role of global civil society in this process, the questions that I raised in this post will certainly require further thinking and research.

This post greatly benefited from contributions by my colleagues from the Oxfam BRICSAMIT group: Nina Best (Brazil), Elena Konovalova (Russia), Supriya Roychoudhury (India), Kevin May (China), Marianne Buenaventura (South Africa), Alejandra d’Hyver (Mexico), Meryem Aslan (Turkey)

September 9, 2013

If high staff turnover is unavoidable, how should we redesign aid work to cope?

One of the implicit assumptions that often underlies programme design is that the people who initially come up with an idea and turn it into a project or programme then stick around and implement it.

The reality is often very different – high levels of staff turnover are almost universal in both NGOs and aid agencies, with serious consequences. On the way over to Australia, I bumped into an Oxfam gender adviser in Afghanistan, who told me that typically expats work a couple of years, then leave, either through burn out or because they are on short term contracts. Then new arrivals start the learning process all over again (often including repeating the same approaches and discussions of the previous years – at worst, producing a Groundhog Day of ‘steep learning curves’, followed by loss of the accumulated knowledge. Then repeat.)

On the way over to Australia, I bumped into an Oxfam gender adviser in Afghanistan, who told me that typically expats work a couple of years, then leave, either through burn out or because they are on short term contracts. Then new arrivals start the learning process all over again (often including repeating the same approaches and discussions of the previous years – at worst, producing a Groundhog Day of ‘steep learning curves’, followed by loss of the accumulated knowledge. Then repeat.)

This problem doesn’t just apply to expats – a lot of local staff get a couple of years’ INGO experience under their belts, only to be lured away by better salaries working for the UN or government aid agencies, or the need to progress their careers elsewhere. Acting as a training institution for other, larger organizations may strengthen the system as a whole, but it doesn’t make it easy to run an effective programme.

So today’s essay question is, would our programmes look different if we assumed average staff turnover of, say, 2 years? Some thoughts:

Knowledge Management: nothing worse than coming into a project to find anything useful buried in a chaotic filing system, and much of the implicit knowledge (eg on how things actually work) not written down at all. How can we get better at capturing useful knowledge, and make it readily accessible? Should people’s departure include a week in a padded room without internet, to write up their experience? Make back to office reports after field trips more systematic and retrievable?

Outsourcing the wisdom: an alternative is to find more stable sources of knowledge and insight – local academics, ex-aid workers who still live in the area, or (even better), make sure that ‘partnership’ includes a full briefing of incoming staff by communities or partner civil society organizations. In some cases it might even be worth setting up a network or organization to provide this kind of institutional/issue memory – imagine every incoming gender worker arriving in Kabul spent a week with half a dozen Afghans/expats with decades of combined experience in gender work. Even better if this was backed up with a serious bit of mentoring, with each new gender worker in Afghanistan able to pick the brains of someone who’d been through it before, or (as mentors may not be permanently on tap), set up a group of sages, who can receive and feed back on regular email updates from current staff. Think how much collective time that could save, allowing people to build on past knowledge, go further, stand on the shoulders of giants etc etc – wouldn’t that be worth funding?

Outsourcing the wisdom: an alternative is to find more stable sources of knowledge and insight – local academics, ex-aid workers who still live in the area, or (even better), make sure that ‘partnership’ includes a full briefing of incoming staff by communities or partner civil society organizations. In some cases it might even be worth setting up a network or organization to provide this kind of institutional/issue memory – imagine every incoming gender worker arriving in Kabul spent a week with half a dozen Afghans/expats with decades of combined experience in gender work. Even better if this was backed up with a serious bit of mentoring, with each new gender worker in Afghanistan able to pick the brains of someone who’d been through it before, or (as mentors may not be permanently on tap), set up a group of sages, who can receive and feed back on regular email updates from current staff. Think how much collective time that could save, allowing people to build on past knowledge, go further, stand on the shoulders of giants etc etc – wouldn’t that be worth funding?

Turnover makes it even more necessary to adopt working practices based on iteration and review, rather than designing the Big Plan and then implementing it – iteration (as in the power and change cycle) means each succeeding wave of workers helps design and improve the programme, and in the process understands it.

Any other suggestions?

September 8, 2013

Are wages the fly in the Fairtrade ointment?

Next year will be the 20th anniversary of the Fairtrade Foundation, (Oxfam was one of its founders) and there will be lots of well-merited celebrations. The growth of fair-trade has been phenomenal. In the UK total sales of Fairtrade products have soared from £63m in 2002, to £1530m last year, growing at double digit rates even through our new age of austerity.

celebrations. The growth of fair-trade has been phenomenal. In the UK total sales of Fairtrade products have soared from £63m in 2002, to £1530m last year, growing at double digit rates even through our new age of austerity.

Like many other development types, I’m a huge fan of Fairtrade. It’s an action you can take in your daily life that makes a difference. Hundreds of thousands of people producing products from coffee to tea, bananas and flowers have benefited. In Malawi the Fairtrade Premium supports the largest adult-education project for tea workers in the country. In Kenya flower workers were found to have better employment contracts, and the premium has funded gas cylinders and pressure cookers which reduce the time women spend gathering firewood.

But there is a fly in the fair-trade ointment. Wages. Back in the 1990s I remember being shocked when a Honduran trade unionist asked me if I realized that wages and conditions were substantially better on Chiquita’s banana plantations than on their Fairtrade-certified neighbours.

Recent research suggests that not enough has changed since that conversation took place. This year, Oxfam took part in a research project on wages in the tea industry with Ethical Tea Partnership, and found that wages were uniformly low on all hired labour plantations in the countries studied, whether Fairtrade (or or UTZ or Rainforest Alliance) certified or not. In Malawi, even adding in-kind benefits and productivity payments to cash piece-rates still didn’t take wages above the level required to get past the international extreme poverty line .

The Fairtrade Foundation tells me in an email, however that ‘certified farms are more likely to provide better conditions in terms of overtime, maternity, written contracts etc.’ But still, this hardly seems to compensate as long as the core issue of poverty wages is not resolved.

Some steps are now being taken. Fairtrade International, the global body to which the Foundation belongs, has a programme on workers’ rights and has just finished a public consultation on the draft of a new Standard for Hired Labour.

That draft includes attempts to strengthen the ‘teeth’ of Fairtrade certification when it comes to getting beyond paying a minimum wage to paying a ‘living wage’. But as the document to its credit acknowledges, that’s because such efforts have so far stayed as vague aspirations, routinely ignored by auditors when they arrive to certify farms.

So what are the obstacles to workers on certified farms getting a living wage? I think one problem is about framing – the imaginary world of fair trade is populated by peasants: family farmers cultivating their own land, who need help with getting organized into co-ops and getting a decent price for their products. That’s where research seems to find the most impact, rather than on plantations with hired labour.

Fairtrade International’s own independently commissioned research concluded that the incomes of Malawi tea smallholders increased 3 fold with Fairtrade, a big contrast to our findings on plantation wages. As a Fairtrade fan, this means I will have to change my shopping habits. Up to now, I thought the benefits to workers of any Fairtrade-certified product were more or less the same, so I buy supermarket brands to encourage them to stock the stuff. But now it seems that some Fairtrade products are more beneficial than others. Cafedirect reports that 22% of the value of a box of Teadirect tea goes direct to the producer coops (who are all smallholder tea growers, no estates involved).

Fairtrade International’s own independently commissioned research concluded that the incomes of Malawi tea smallholders increased 3 fold with Fairtrade, a big contrast to our findings on plantation wages. As a Fairtrade fan, this means I will have to change my shopping habits. Up to now, I thought the benefits to workers of any Fairtrade-certified product were more or less the same, so I buy supermarket brands to encourage them to stock the stuff. But now it seems that some Fairtrade products are more beneficial than others. Cafedirect reports that 22% of the value of a box of Teadirect tea goes direct to the producer coops (who are all smallholder tea growers, no estates involved).

The Divine chocolate company is nearly half owned by Kuapa Kokoo cocoa producers in Ghana. While Fairtrade ensures farmers receive a better deal for their cocoa and additional income to invest in their community, company ownership gives farmers a share of Divine’s profits and a stronger voice in the cocoa industry.

But peasants are often also employers, and that seems hard for fair-trade and NGO types to get their heads around: I remember visiting an Oxfam ‘small farmer’ project in Nigeria, where the lead farmer told me he employed 50 workers – we had never even asked what they were earning. How much of the Cafedirect or Kuapa Kokoo benefits goes to temporary hired labour on smallholder farms?

And as for hired workers on large farms, how could we ensure that Fairtrade certified plantations pay a living wage?

One option might be for buyers to pay a ‘Fairtrade living wage premium’ directly to workers. The point there is to ensure that an extra 5 pence (or 8 cents) on a bouquet of fairtrade flowers does not then get multiplied up the supply chain and cost a lot more for shoppers. They should just pay the additional 8 cents. Oxfam did something a bit like that 10 years ago when we found out just how little people were earning by making our Christmas crackers in South Wales. But what if only 10% of the workers on a plantation are producing for Fairtrade for 10% of the year? Real life tends to get messy.

Another way is to try and ensure that certification exerts steady upward pressure towards achieving living wages (which it has so far failed to do). The draft standard text says ‘Your company must negotiate with workers on how a living wage will be reached.’ But there is no deadline – that feels pretty weak – what if no agreement is reached, or the talks drag on for years? And anyway, is this within the power of Fairtrade to deliver, when dealing with powerful brands and retailers competing with each other on price?

The other way is of course, the trade union route preferred by organizations like the Ethical Trading Initiative. Trade unions are understandably worried about their representative position being undermined by private standards, even Fairtrade ones: who decides wage rates, the union or a Living Wage auditor? In the case of Indian tea pickers, though, even trade unions have been unable to overcome the crisis in the industry – Assam, which has a union-negotiated collective bargaining agreement, has failed to achieve progress on wages. Plantation owners are able to argue that they are sticking to Collective Bargaining Agreements on wages (which set sub-living wage levels), as the proper mechanism for agreeing wages.

worried about their representative position being undermined by private standards, even Fairtrade ones: who decides wage rates, the union or a Living Wage auditor? In the case of Indian tea pickers, though, even trade unions have been unable to overcome the crisis in the industry – Assam, which has a union-negotiated collective bargaining agreement, has failed to achieve progress on wages. Plantation owners are able to argue that they are sticking to Collective Bargaining Agreements on wages (which set sub-living wage levels), as the proper mechanism for agreeing wages.

The draft standard wants to introduce a Right to Unionize protocol that must be signed by all employers, but it is not clear what happens if they sign, but then ignore it – will that tick the box or not? In the tea industry, union agreements have so far not managed to reach living wage levels, but in the long run, the role of fairtrade is surely to support the unions to get better deals across the whole tea sector, rather than establish any kind of substitute mechanism that only applies to certified plantations.

All of this would be made a great deal easier if the brands and retailers would find ways to absorb a small increase – earmarked for wages – and the industry finds ways to make wage negotiation more meaningful. So kudos to Fairtrade for grasping the nettle of trying to ensure that people on the sharp end receive wages they can live on. Let’s hope they succeed and that there’s a knock on effect on the rest of the supply chain.

If you find this a long and confusing post, sorry, but this is a messy and complex problem – if it was simple, it would have been fixed by now.

September 5, 2013

Speed reading rocks, so why don’t we all learn it?

The best day’s training I ever did was a speed reading course, offered by DFID (I had a short stint there about ten years ago). It helps me every day – when was the last time you could say that about a training course?

every day – when was the last time you could say that about a training course?

The first part of the course covered what you normally think of as speed reading – reading faster. When you read unaided, your eye jumps backwards and forwards, as well as up and down between the lines. By simply using a guide (a pencil, or one of those plastic coffee stirrers) and moving it under the line as you read, you can double your speed without missing content (we tested ourselves at the beginning and end of the day, and it was true).

But you have to concentrate really hard and take regular breaks, and you have to avoid saying the words aloud in your head (which slows you down). Since then, I have occasionally tried it, but it hasn’t stuck.

The second part of the training seemed less significant at the time, but has had a much bigger impact: how to approach a document. Unless you’re reading for pleasure, you should not just assume that you start at the beginning and read through to the end. The document has to earn your time.

That means

First read the exec sum or abstract.

If that looks interesting, read the introduction and conclusion. You then make a judgement either to stop, or go deeper.

If you decide there’s more to extract from the document, read the first and last paras of each section or chapter.

And if they still leave you hankering for more, read whole sections or chapters (but probably not all of them)

In the last resort, for something really special, read the whole document.

The time saving (with minimal loss of content) is amazing. And if that sounds brutal, a Vatican official who seemed to have read everything once explained to my friend Fran Equiza that his secret is to assume that any document has only one main idea, and once he has found that, he stops reading.

But if lots of people read like this, there are some important implications for writers as well as readers:

Make sure that all the important content is in the exec sum or abstract. For exec sums that includes any killer facts or significant graphics. It’s amazing how often this is missing – especially in abstracts, which often merely say what topic the paper is going to cover, not its main findings.

Make sure the introductory and concluding paras of a chapter or section act as mini-exec sums. This may clash with another purpose of introductions – to lure the reader in by starting with some startling fact or human colour. I guess it depends on whether your target audience is normal people (reading from the beginning until they get bored) or extractive wonks, reading like me.

Make sure the introductory and concluding paras of a chapter or section act as mini-exec sums. This may clash with another purpose of introductions – to lure the reader in by starting with some startling fact or human colour. I guess it depends on whether your target audience is normal people (reading from the beginning until they get bored) or extractive wonks, reading like me.Anyone working in development has to absorb a lot of information (how many times have I heard people lament that ‘they haven’t got time to read’?), so why isn’t speed reading part of our basic training?

Any other thoughts on the pluses, minuses and nature of speed reading? Here’s what Wikipedia has to say about it and here’s a promising looking online course.

And in case anyone feels affronted, can I just say that if I’ve ever reviewed your work on this blog, I have of course read and cherished every word…….

Ups and downs in the struggle for accountability – four new real time studies

OK, we’ve had real time evaluations, we’ve done transparency and accountability initiatives, so why not combine the two? The thoroughly brilliant International Budget Partnership is doing just that, teaming up with academic researchers to follow in real time the ups and downs of four TAIs in Mexico, Brazil, South Africa and Tanzania. Read the case study summaries (only four pages each, with full versions if you want to go deeper), if you can, but below I’ll copy most of the overview blog by IBP research manager Albert van Zyl.

brilliant International Budget Partnership is doing just that, teaming up with academic researchers to follow in real time the ups and downs of four TAIs in Mexico, Brazil, South Africa and Tanzania. Read the case study summaries (only four pages each, with full versions if you want to go deeper), if you can, but below I’ll copy most of the overview blog by IBP research manager Albert van Zyl.

By following the work rather than tidying it all up with a neat but deceitful retrospective evaluation, they record the true messiness of building social contracts between citizens and states: the ups and downs, the almost-giving-up-and-then-winning, the crucial roles of individuals, the importance of scandals and serendipity.

From the overview by Albert van Zyl

‘In the governance field too many learning efforts are based on selective and retrospective documentation of success stories or on politically blind ‘treatments’ parachuted into random contexts. Both approaches undermine the learning potential of governance research. This is why in 2009 the International Budget Partnership and civil society partners Fundar, Ibase, the Public Sector Accountability Monitor, and Haki Elimu took a different approach and gambled on documenting their budget advocacy in real time. This project is part of our ongoing commitment to learning about how, when, and under what circumstances civil society organization’s (CSO) budget advocacy has impact, and how to scale it up. We appointed external research teams to follow specific advocacy campaigns of each of these four organizations over a four year period. Now it’s time to come clean: no airbrushing out serendipity, random events, or failure. Just the stories. As they happened. Think you’re ready?

What did they do? And what happened?

The Public Sector Accountability Monitor (PSAM) monitored, analyzed, and publicized budget and service delivery information produced by the health department of one of the weakest provincial governments in South Africa. While its efforts initially had a limited direct impact on the dismal performance of the provincial government, the national government took note and intervened. As a result, the financial management of the Eastern Cape health department improved substantially after the provincial health minister and head of department were replaced, 31 officials were criminally charged, and a further 800 officials were dismissed.

In Brazil Ibase sought to make the operations of the BNDES (the state-owned development bank with an annual budget four times that of the World Bank) more transparent, and to introduce stronger social and environmental considerations into the bank’s investment criteria. To pursue these objectives, Ibase mobilized a civil society coalition to engage the BNDES. While Ibase had limited impact on its goals, the case study suggests that its efforts have contributed to a greater societal concern for the impact of the BNDES’ operations — opening cracks in the “policy wall” that once shielded the BNDES from public scrutiny.

HakiElimu used innovative methods like their humorous infomercials (“TV spots”) and the mobilization of thousands of Friends of Education to monitor and publicize the finance and delivery of education in Tanzania. HakiElimu demonstrably contributed to improvements in teacher housing, and the scrapping of unpopular programs to fast track teacher training. The case study also produces evidence that HakiElimu’s innovative tactics have rubbed off on other CSOs and even the legislature.

Fundar partnered with grassroots organizations and the Mexican Congress to monitor the budget and service delivery of the Seguro Popular, the national health insurance agency that is supposed to provide health security to the country’s 52 million uninsured. After a frustrating start Fundar assisted the chairperson of the public accounts committee to introduce seven amendments to the 2012 Federal Budget Decree intended to increase the transparency, expenditure control, evaluation, and accountability of the budget of the Seguro Popular.

Fundar partnered with grassroots organizations and the Mexican Congress to monitor the budget and service delivery of the Seguro Popular, the national health insurance agency that is supposed to provide health security to the country’s 52 million uninsured. After a frustrating start Fundar assisted the chairperson of the public accounts committee to introduce seven amendments to the 2012 Federal Budget Decree intended to increase the transparency, expenditure control, evaluation, and accountability of the budget of the Seguro Popular.

What’s new about all this?

Mixed results can take sustained effort

All four case studies tell a similar story: while there was limited demonstrable impact on service delivery, there were clearer impacts on the management of government finances and on building the capacity of CSOs and other accountability actors to continue this work. What does this mean? Shall we take the positive view that these intermediate impacts on budgets and civic capacity to demand accountability will eventually lead to future improvements in service delivery? Or shall we be more hard-nosed and say that these campaigns simply failed to achieve their stated goals? Both views are probably right and wrong. As Henry Ford is quoted as saying: “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t — you’re right.”

As these advocacy campaigns reveal, budget accountability is constructed, it doesn’t “emerge” — there is no magic bullet. Rather, the case studies reveal a fragile and rocky path to impact that needs continuous work, vigilance, and support.

Political misfortune and opportunity

These rocky paths are helped and hindered by political events that often cannot be foreseen at the start of advocacy initiatives. The work of the PSAM was frustrated by the protection that President Thabo Mbeki provided his AIDS “denialist” allies in the Eastern Cape. When he was suddenly replaced by President Jacob Zuma, new national leadership in the health sector took the bait that the PSAM had been dangling for many years. But this is not always the case. In Brazil the imminent election shifted public attention away from the BNDES and threatened to split Ibase’s carefully constructed CSO network along political and tactical lines.

What does all this mean? Apart from making it hard to predict the impact of CSO advocacy campaigns, it is also clear that the ability of CSOs to adapt to shifting political circumstances is at least as important as their ability to front-load their planning through “log frames,” theories of change, or whatever newfangled planning tools they employ.

Playing nicely with others

The trials and tribulations that result from political shifts and realignments also reinforce the importance of other actors in the impact of CSO campaigns. While the shifting sympathies of the national government helped, the PSAM would not have had much impact if consistent media reporting had not kept its analyses on the desks of national decision makers. In a similar way, it was only once Fundar found a willing ally in the chair of the public accounts committee in congress that their concerns were taken into account and carried forward into legislation.

Future efforts to support CSO advocacy for budget accountability, therefore, should not only focus on building the capacity of CSOs but also on building the capacity of other actors in the accountability system – such as the media, legislatures, auditors, and even sympathetic insiders in the executive – and the necessary linkages among them.’

Great stuff. And here’s one final, thought-provoking observation from the Brazil case study, for these results- and success-obsessed times. Studies of economic innovation show that success is often born out of the remnants of a previous failure. Turns out the same is true of NGO work such as TAIs. The Brazil study ends with the thought ‘Someone always has to make the first move. For every instance of successful advocacy, there is usually a less successful case that set the stage first.’

September 3, 2013

When do Transparency and Accountability Initiatives have impact?

So having berated ODI about opening up access to its recent issue of the Development Policy Review on Transparency and Accountability Initiatives (TAIs), I really ought to review the overview piece by John Gaventa and Rosemary McGee, which they’ve made freely available until December.

(TAIs), I really ought to review the overview piece by John Gaventa and Rosemary McGee, which they’ve made freely available until December.

The essay is well worth reading. It unpicks the fuzzy concept of TAIs and then looks at the evidence for what works and when. First a useful typology of TAIs:

‘Service delivery is perhaps the field in which TAIs have been longest applied, including Expenditure Tracking Surveys, citizen report cards, score cards, community monitoring and social audits.

By the late 1990s, moves to improve public finance management the world over led to the development of budget accountability and transparency as a sector in its own right…. An array of citizen-led budget TAIs has developed, including participatory budgeting; sector-specific budget monitoring (for example, gender budgeting, children’s budgets); public-expenditure monitoring through social audits, participatory audits and tracking surveys; and advocacy for budget transparency (for example, the International Budget Partnership (IBP)’s Open Budget Index). Many of these initiatives focus ‘downstream’ on how public funds are spent; less work focuses on T and A in revenue-generation, although this is growing with recent work on tax justice.

Elements of social accountability in service delivery therefore overlapped from the start with developments in the Freedom of Information (FOI) sector. The number of countries with legislation in place has exploded from 12 in 1990 to around 80 today.

One application of FOI legislation is to the governance of natural resources such as land, water, forests, fish stocks and minerals. These include the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which seeks to secure verification and publication of company payments and government revenues from oil, gas and mining. Other groups such as the Revenue Watch Institute also campaign for disclosure (for example, through the Publish What You Pay campaign), monitor the implementation of the EITI and seek to extend these approaches into new areas such as forestry.

A strand of aid accountability and transparency has also evolved, sharing many of the same principles, approaches and methods as TAIs in the service-delivery, FOI and budget sectors. Attempts are under way to develop suitable climate-change TAIs.’

‘TAIs in aid and development are increasingly being used within an efficiency paradigm, with scant attention to underlying issues of power and politics. Many TAIs focus on the delivery of development outcomes, neglecting or articulating only superficially the potential for deepening democracy or empowering citizens.’

As for what works:

‘On the state or ‘supply’ side, three important explanatory variables emerge:

Our review revealed little evidence of impact of TAIs in non-democratic settings, but did show some impacts in emerging democracies and fragile settings. Essential freedoms of association, voice or media enhance the prospects of impact.

A political environment that favours a balanced supply- and demand-side approach to accountability is critical to TAIs’ success. Where the state is willing to adopt accountability provisions, the utility of these depends on their being fully institutionalised and having ‘teeth’. Champions inside the system can help citizen-led TAIs succeed, but may find themselves constrained by systemic and institutional factors. Citizen participation and pressure are needed to get from political won’t to political will – but ‘political will’, an oft-used and insufficiently explicit term, needs further unpacking.

Democratic space and committed state actors or political leadership may not be enough to bring about the desired changes. Also relevant are the broader political economy and prevailing legal frameworks and incentive structures within which political representatives and state functionaries operate.

On the citizen side, three further factors emerge:

increased transparency to have an impact, citizens must be able to process, analyse or use the newly available information. Their capabilities can be strengthened by active media; prior social-mobilisation experience; coalitions; and intermediaries who can ‘translate’ and communicate information.

TAIs appear to gain traction from being linked to other mobilisation strategies like litigation, electoral pressure or protest movements, and

through invoking collective rather than, or besides, individual action. Paradoxically, a multi-stranded or collective approach also makes it harder to isolate the impact of any one factor or actor alone.

through invoking collective rather than, or besides, individual action. Paradoxically, a multi-stranded or collective approach also makes it harder to isolate the impact of any one factor or actor alone.Many TAIs focus on citizens’ ‘downstream’ role in implementing policies that were formulated without their involvement. Citizens who were engaged further ‘upstream’ in formulating the policies are more likely to engage in monitoring them; and engagement in policy formulation can arguably increase accountability more than ex-post monitoring.’

All in all a very useful intro, shame the rest of the journal articles are still behind the paywall.

September 2, 2013

How to challenge short term thinking in development and research?

Over the next few days this blog will be even more scattergun than usual as I’ve just arrived in Australia for a 3 week tour (including New Zealand). Got in on Sunday evening after weeping my way through all 8 episodes of Broadchurch (hope I didn’t alarm fellow passengers). It’s a fantastic crime drama with the extraordinary Olivia Colman (David Tennant wasn’t bad either). Please note, box-setters, Broadchurch is up there with The Killing (only set in Dorset, and it doesn’t rain quite so much).

First up this week is 3 days teaching on ‘how change happens’ at Murdoch University in Perth. Then off to Melbourne, Canberra, Wellington and Auckland. Updated list of all public events and ticket details here. Met the Murdoch students last night – an amazing bunch, and I imagine there’ll be plenty to talk about on the blog as the course unfolds.

Meanwhile, one of my last conversations before jumping on the plane was with Andree Carter of the UK Collaborative on Development Sciences. She’s doing a ring round of the usual suspects on ‘how to challenge short term thinking on science for development (currently constrained by political and budgetary cycles)’ (Lawrence Haddad was also on her call list). I was a bit confused (eg over whether we were talking about short-termism in aid and development work, or in research itself) but it was a fun conversation, so why not recycle it for the blog?

doing a ring round of the usual suspects on ‘how to challenge short term thinking on science for development (currently constrained by political and budgetary cycles)’ (Lawrence Haddad was also on her call list). I was a bit confused (eg over whether we were talking about short-termism in aid and development work, or in research itself) but it was a fun conversation, so why not recycle it for the blog?

First on the overall idea: where else have people tried to shift from short-termism to a long term view? Institutional investors trying to go beyond the obsession with quarterly returns? Investing in big infrastructure like energy? Climate change? What are the drivers and blockers in these areas – what lessons can be learned on development research?

Now on to Andree’s questions (in italics), plus my answers:

What will the future research architecture funding and delivery mechanisms look like – will they be fit for purpose in the UK and in other countries – national, regional and global approaches – will national interests always override global needs?

Future research agendas will be decided by the outcome of a number of dichotomies/competing demands:

What is right (research funding delinked from nationality of institution) v what is easy, fast and popular with UK institutions (research as tied aid)

The need to maximise impact of research by responding to events in the world outside v the steady and slow pace of the academic incentive structure

The paradigm clash between value for money and complexity/political science. The first school, dominated by orthodox economists and medics, privileges experimental methods, hard data, and attribution. The second group emphasizes complex systems in which attribution can seldom be conclusively proved, and gives more weight to theory and qualitative evidence. More on this here.

The Open Access movement v the dominance of peer-reviewed journals. See here.

Linked to this, the emphasis (or lack of it) placed on research impact in future funding decisions. More here.

Rapidly changing geopolitical landscape – UK-led research hubs in E Africa, partnering with China Ministry of Commerce already etc

Rapidly changing geopolitical landscape – UK-led research hubs in E Africa, partnering with China Ministry of Commerce already etc

Step back and ask, what is the UK’s unique selling point? Cash, for a dwindling number of aid dependent countries, but what have we got to offer those countries able to fund their own research? Parallels with the general aid discussion on how to work in middle income countries – e.g. encourage exchanges between researchers in different countries, support ‘excluded research’ topics. See answer to point 4 for some additional thoughts.

The ‘Beyond Aid’ agenda – following the UK International Development Committee inquiry and promoting the key role of science technology and innovation in any new approach

The UK is sitting on a pile of knowledge on a range of issues that are of increasing importance in developing countries: how to minimize the carnage from road traffic, tobacco and alcohol. How to combat obesity and heart disease. How welfare states can guarantee the rights of disabled people, or care for the mentally ill. We have a much clearer offer on these than on, say, agriculture or growth. Yet such Cinderella issues remain largely absent from the official development debate. More here.

Development challenges for the future

How do we apply complexity and systems thinking to development challenges? See here.

What is the role of research when decision makers are clearly not acting on the basis of evidence (e.g. climate change)? Probably not ‘hey, let’s generate lots more evidence, that should do it.’ How can ‘research for advocacy’ be undertaken without damaging the credibility of the research?

And of course, one of the biggest development headaches of them all – what role can outsiders, including researchers, usefully play in strengthening fragile and conflict affected states. More here.

How to best communicate this thinking to help funders think in longer term cycles

More funding for longitudinal research, sentinel sites, windows on the world etc, such as Young Lives or our own Food Price Volatility research.

Better stories – more convincing narratives on how development happens

More cross-silo exchanges, not just interdisciplinary within academia, but between researchers and civil society organizations, media outlets or governments

Copy the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s model of funding people, not projects. Spot bright young minds that are likely to come up with innovative solutions, and back them.

Like I said, this week may be a bit more random than usual……..

September 1, 2013

How realtime evaluation can sharpen our work in fragile states

Pity the poor development worker. All the signs are that their future lies in working in ‘fragile and conflict-affected states’ (FRACAS) – the DRCs, Somalias, Afghanistans and Haitis. As more stable countries grow and lift their people out of poverty, that’s where an increasing percentage of the world’s poor people will live. And (not unconnected) they are the hardest places to get anything done – states that are unwilling, unable or both; dilapidated infrastructure; social and organized violence; enfeebled institutions.

world’s poor people will live. And (not unconnected) they are the hardest places to get anything done – states that are unwilling, unable or both; dilapidated infrastructure; social and organized violence; enfeebled institutions.

So NGOs and aid donors have their work cut out, and are going to need new ways of working to get results. Last week I got a fascinating briefing about one thing Oxfam is trying out in its ‘Within and Without the State’ (WWS) programme, which aims to help strengthen civil society capacity and social contracts between citizen and state in Yemen, South Sudan, OPTI (Occupied Palestinian Territories/Israel) and Afghanistan.

The experiment is realtime evaluation (RTE). The experience of long term development work in FRACAS bears a lot of similarities to emergencies work – rapidly changing contexts, responding to the unexpected, thinking on your feet etc. The rather cumbersome process of monitoring and evaluation, often at the end of a project, doesn’t help much. So the WWS team decided to borrow and adapt humanitarian RTEs and try them out in South Sudan.

Here’s the summary from the internal guidance note (RTE methodology for WWS_South Sudan_Mar13 – keep clicking).

What is a Real Time Evaluation (RTE)? A RTE is an internal rapid review usually carried out early on in a humanitarian response (usually between six weeks to two months after the onset of an emergency) in order to gauge effectiveness, and to adjust or correct the manner in which the project is being carried out. It should be seen as “a snap-shot in time” or a time to “step back and reflect.” Real time evaluation is closer to monitoring, getting quick feedback on operational performance, and identifying systemic issues.

RTE is a learning exercise:

Carried out by internal evaluators who are not involved with the project

Addresses all staff involved in the project both at head office and the field and with implementing partners.

Interactive and flexible.

Uses traditional evaluation tools such as interviews, focus groups and observation.

Rarely takes more than 2 weeks – usually 8-10 days (a week in the field and a couple of days in the country office)

Findings are shared with staff before leaving the field, preferably during a “day of reflection” workshop.

Has more emphasis on lessons identified and a small number of action points, with a heavy emphasis on how these will be taken forward.

It is not a replacement for an impact evaluation or a technical review that is usually held at a midpoint in the project life or before closure.

A draft report should ideally be completed within a week of the RTE and sent for comments

The report should be no more than 15 pages, plus annexes

The experience in South Sudan was pretty positive – the focus on learning and adapting meant people felt less defensive, and more open to acknowledging problems/challenges and finding ways round them. Practical steps that emerged from the RTE included deciding to introduce community scorecards to improve WWS’ accountability, developing ways to measure improved levels of trust between citizens and state, and making sure a key staff person working on community engagement did not spend his whole time in the office covering for high levels of staff turnover. Most of the recommendations were implemented within weeks of the RTE.

Some wider points:

The RTE preceded the political meltdown in South Sudan, raising the issue of whether they should be scheduled or reactive. Can a small number of people in the programme be given the ability (and supporting resources) to trigger an RTE in response to a major contextual shift?

The RTE preceded the political meltdown in South Sudan, raising the issue of whether they should be scheduled or reactive. Can a small number of people in the programme be given the ability (and supporting resources) to trigger an RTE in response to a major contextual shift?

Staff appreciated the chance to stand back from the day to day chaos of working in a fragile state, and reflect on the processes and impacts to date, but can we make this a continuous part of the day job, rather than a response to the arrival of the evaluator from HQ?

Doing it fast really helps – got to avoid this becoming a long drawn out affair. But there are costs to keeping it quick: it would have been good to have someone from another FRACAS involved, and there could have been more direct engagement with communities. Maybe as prep ask each member of staff and partner involved in the RTE to go and sit down in advance with a community and pick their brains?

And the funders? NGOs often say ‘oh sure, we want to be agile, but the donors won’t wear it – they’ll make us stick to the logframe’. Not so. DFID, which funds the WWS project, has supported the RTE and told us they want to see new and exciting ideas (rather than people whinging about how linear programming doesn’t work). They’ve been happy for us to adapt indicators and targets.

All this fits nicely with the work I’ve been doing on how we can use a ‘power and change cycle’ to guide our work in complex environments – using periodic, low cost sense checks to assess progress and adjust course as we go. V encouraging.

Photo credits: Crispin Hughes

August 29, 2013

Creating a splash with Data Diving

Over a July weekend in London four charities and more than 80 data professionals took part in a “DataDive”, organized by

DataKind UK

.

Ricardo

, Richard

and

Simone

from Oxfam’s Research Team (see pic of handsome hunks below) went along. Here’s what happened.

Richard

and

Simone

from Oxfam’s Research Team (see pic of handsome hunks below) went along. Here’s what happened.

If you came to London for a weekend during the best summer since 1976, how would you like to spend your time? Inside, hunched over a laptop crunching numbers, that’s how.

At the end of a glorious (weather-wise) July, we joined a large number of volunteers and data scientists for a ‘DataDive’. We came armed with access to a couple of relevant datasets, a specific problem we wanted some help with, and an acute knowledge of the limitations of our own abilities. To invoke the spirit of Donald Rumsfeld, we knew what we didn’t know, but we also knew there were things that, as number crunchers, we didn’t know we didn’t know. The event seemed like the place to find them. The sheer collection of advanced numerical skills gathered in the DataDive would give us insights we didn’t know we could have. We were lucky that our application to participate was successful.

These gatherings are a bit like speed-dating, and a bit like the reality show The Bachelor. A group of bright, successful and motivated organizers (some of them coming from the US for the event) put together a venue (and pizza, and beer) to match needs (us) and skills (volunteering number crunchers). Data scientists with very different backgrounds and abilities devote their spare time to work on something different, and hopefully meaningful, from their everyday work. Charities and institutions (in this case HelpAge International, Hampshire County Council, CVAT and Oxfam) get exposed to new innovative ways of working and try to solve very concrete problems that can support their work.

DataDives are getting popular. In January DataKind (the organization behind the event in London) and UN Global Pulse organized ‘Data science at the United Nations’ in New York. In February the World Bank and UNDP held an event on ‘Measuring Poverty’ in Vienna, followed by another one in March in Washington DC.

Each organization pitched their questions to the assembled geeks (hence the speed dating analogy). Our pitch to attract people to our problem was rather simple: using a couple of databases on monthly local food prices, we wanted to have a better understanding of the patterns that underlie their movements (long-term creeping trends? Recurring seasonal changes? Random noise? All three?). This curiosity is partly borne out of our qualitative work on food price volatility, but also a need to better understand how and why local food prices are changing over time. Our initial questions related to the trends for local prices, their correlation with other indicators such as cost of fuel and rainfall, and how we could we identify and track sentiments on local food price movements from the web and social media.

The main two datasets we proffered were from similar sources: the FAO Global Information and Early Warning System (GIEWS) and FEWS NET’s monthly food price monitor. Both datasets include monthly price data for staple food commodities in a variety of local markets in developing countries.

Out pitch must have been geek catnip, because about 30 volunteers chose to spend their time working with us and were split into groups. The first group produced a trend disaggregation analysis for different products and countries, and came up with a price prediction model – including the documentation to replicate the analysis using R, an open-source statistical software package. The same group also created a useful interface tool for visualising food price trends for different commodities and time periods in different countries. Probably the most appealing and innovative piece of analysis was on rainfall and food prices. The creators modelled the timing of rainfall throughout the year and estimated peak precipitation deviations from the expected day of maximal rain, linking these to food price time series. Finally the team working on signals from social media and the web prepared several useful ways to extrapolate data from the web, Twitter and Google Trends.

Come on in, the data's lovely....

This was just a first date, and these preliminary explorations will be further prodded, interrogated, and developed (hopefully with the help of some of the July volunteer data crunchers). The DataDive opened new doors that we would like to explore together with the volunteers. We know much more than we did that sultry Friday riding the train from Oxford to London. And more importantly, we have an explicit workplan to build on the initial, frenetic, caffeine-fuelled effort. We plan to follow up by:

1. Adding a local price visualisation tool to the website for our existing research work on the impacts of food price volatility

2. Looking at the linkages between variations in seasonal rainfall patterns, local prices and harvest volumes.

3. Merging the information on local markets from sites like M-Farm with web-based measures of “consumer sentiment”

“Matching” is one of those words that economists use to understand how mutually beneficial relationships form. The DataDive was a fantastic practical matching exercise. Like all plunges (or first dates) it was a bit of a leap into the unknown, but we were handsomely rewarded with dozens of people volunteering their (very expensive) time to help us understand a problem so central to our work. We are very grateful to the organizers, data ambassadors and volunteers who worked with us during and leading up to those three days. All in all, a great Speedo-free weekend’s diving and dating.

If you want to read more, The Economist and the Guardian had good write ups .

August 28, 2013

A week at the Edinburgh festival: good theatre, bad music and great books

Last week Cathy and I spent our annual week at the Edinburgh festival. It provides a high intensity restoration of the mental flora (colonic irrigation of the soul?) before the autumn grind begins. We tend to avoid the ubiquitous stand-up comedy, even though the heckling sounds pretty amazing, and go for a more NGO-compatible diet of miserabilist theatre, random music and heavy reading.

grind begins. We tend to avoid the ubiquitous stand-up comedy, even though the heckling sounds pretty amazing, and go for a more NGO-compatible diet of miserabilist theatre, random music and heavy reading.

Best theatre was undoubtedly Grounded, a stunning one woman show about drone attacks (see what I mean about miserabilism?). The most random music was definitely the massacring of Dark Side of the Moon by ‘MacFloyd’ (seemed a good idea at the time). But as most of you won’t be going to Edinburgh, I’ll stick with the 3 books I got through. Two good and one great.

Let’s get the good ones out of the way: Chavs: the Demonization of the Working Class by Owen Jones unpacks the one form of abuse of what Robert Chambers called ‘lowers’ that has become socially acceptable among British liberals – ridiculing the ‘chavs’ – white working class kids in shellsuits and burberry. Think Vicky Pollard in Little Britain. (Does ‘chav’ mean anything in the US, or is there some other equivalent for modern rednecks?). Jones argues that it is the latest stage in the economic and political destruction of the traditional working class, which has allowed elites to move from 1970s fear of ‘the enemy within’ to today’s overt ridicule. It’s good old-fashioned polemic by a great young leftist writer, and I certainly won’t be using that word again.

‘Shame: Confessions of an Aid Worker in Africa’, by Jillian Reilly is a painfully honest autobiographical account of how a young American woman lost her messiah complex while inflicting capacity building and AIDS awareness programmes on Southern Africa in the 1990s. She never really had a chance – she writes far too well to be an aid worker.

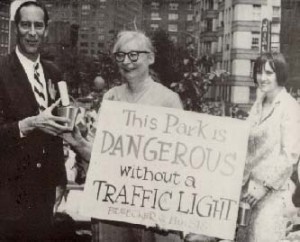

But top of my Edinburgh reading list was a 1961 classic: The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs. It did for our understanding of cities what Silent Spring (published the following year) did for the environment. Jacobs loves cities, and was a devoted activist (see pic) in defending what she valued – the diversity and life of the streets.

But top of my Edinburgh reading list was a 1961 classic: The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs. It did for our understanding of cities what Silent Spring (published the following year) did for the environment. Jacobs loves cities, and was a devoted activist (see pic) in defending what she valued – the diversity and life of the streets.

The picture she paints is of city as organism, a living ecosystem far too complex for the simple linear approaches of traditional top-down planning. She was writing as the ‘projects’ of just such planners were spreading blight across the urban US. She has an instinctive grasp for complexity, and how to navigate it, and tried to introduce early complex systems thinking from the life sciences into debates on urban systems.

Basing her ideas on deep observation of particular neighbourhoods, she concludes that a diverse, dynamic urban district requires a combination of four elements: a range of primary functions (i.e. not just office workers who disappear at 5pm); short blocks with lots of intersections and corners; a mingling of old and new buildings, with old buildings providing cheap rents for lower-yielding businesses; and a sufficiently dense concentration of people. She contrasts this with the gut dislike of untidy, chaotic, heavily peopled cities that underpinned the ‘garden city’ movement and other modernist attempts at imposing ‘rational’ central planning.

Her focus is on the dynamics – how do slums emerge, and then ‘unslum’? Why is diversity inherently unstable, always at risk from the rise of a monoculture that becomes more profitable than the alternatives? She finds that the key to unslumming is not shipping in middle classes, or mass redevelopment, but making it possible for the talented members of the next generation to stay in their home neighbourhoods, by allowing them to finance and upgrade existing slum housing (often their childhood homes).

For Jacobs the proper role of planners is to observe the reality of city life, put their ‘master plans’ to one side, and instead ‘plan for vitality’, finding ways to ‘reweave’ the communities that have been destroyed, for example by restoring the four drivers of diversity.

And she has great throwaway lines: ‘the trouble with paternalists is that they want to make impossibly profound changes, and they choose impossibly superficial means for doing so.’ Planners contemplate the messy unpredictability of the city and find it ‘in some dark and foreboding way, irrational.’

Lots of parallels with Donella Meadows here, and both resonate with current development debates: the importance of preceding any intervention with deep, slow, respectful observation; the need to understand the workings of the system as a whole (not just its elements); to think about processes, not objects (‘the park’, ‘the civic centre’ or in development-world, ‘the workshop’, ‘the borehole’); the need to start from the particular, not from the general rule; the case for gradualism and trial and error, rather than grand plans.

deep, slow, respectful observation; the need to understand the workings of the system as a whole (not just its elements); to think about processes, not objects (‘the park’, ‘the civic centre’ or in development-world, ‘the workshop’, ‘the borehole’); the need to start from the particular, not from the general rule; the case for gradualism and trial and error, rather than grand plans.

What I don’t know is how much has changed since 1961. Can planners really still be the top-down control freaks that Jacobs pillories? Has anyone put her ideas into practice and if so, what were the results? (Wikipedia cites her as an inspiration behind 1980s New Urbanism – what happened to that?)

And has she influenced thinking on international development? Chris Blattman once suggested her collected works be sent to South Sudan as a health warning on their development plans (see pic). Anything else?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers