Duncan Green's Blog, page 203

November 4, 2013

Complexity 101: behind the hype, what do we actually know?

Complexity week continues with this excellent stocktake from the ODI’s Harry Jones (who’s got a new guide out on ‘Managing Projects and Programmes in the Face of Complexity‘). Part two tomorrow.

Seven years ago John Young, Ben Ramalingam and I decided to begin research on complexity theory and international development. We felt there was really something of use and interest in there but that it might take some time to persuade others of that fact and more time to find out exactly what that value was: although there were already a few people working on complexity, since then, the blogosphere has come alive with discussion of the ‘C’ word. It’s clear a large number of development professionals see value in complexity theory and international development (for example, here is Owen Barder on complexity in international development, William Easterly’s take, Ben’s blog devoted to the issue, and all the posts on Duncan Green’s blog about complexity and development).

What we don’t seem to have reached is much agreement on exactly what that value is. As we look forwards to this week’s launch of Ben’s book on complexity in development (which I have yet to read), it seems an opportune time to reflect on what we know. In that 2008 exploratory review we set out to examine whether complexity and development was a case of ‘paradigm, hype, or lens’. Six years on, here’s my attempt to review the evidence on some straight questions on complexity and development, in two parts. In this first part, I look at whether development problems are complex and why it matters; in the second part I will look at what to do about that complexity where it exists.

*N.B. to avoid disappearing up my own comments page I will use the popular simple-complicated-complex (bake a cake, make a rocket, raise a child) schema subscribed to by Stacey, Zimmerman, Snowden et al.

1) Are development problems complex?

It is undeniable that many issues, sectors, and challenges have complex characteristics. To name just two examples: on the science-led side Elinor Ostrom used her Nobel prize speech to emphasise the importance of complexity in natural resource management and spent some of her later years attempting to lay solid, shared academic foundations for the study of complex systems.

On the practitioner side, problems of governance and institutional change display the trademark characteristics of messy, unpredictable and adaptive systems. Alan Fowler argues for the centrality of complex, civic-driven change processes; Frauke de Weijer’s experiences in Afghanistan led her to propose that we rethink change in fragile states along complexity lines; and Robert Chambers found that complexity is the most suitable paradigm to explain the bottom-up change processes he has worked with.

On the other hand, I have not seen any strong evidence to say that all problems faced in development are complex. As Charles Kenny at CGD argued recently, while the success of many development interventions is uncertain and depends strongly on context, there are a number of public investments and institutional lessons that we can say with some certainty will have positive contributions to a country’s development.

So the answer to ‘are development problems complex’ is: yes, some of them. While development problems might be more likely to be complex than others, we must judge on a case by case basis.

2) What does it mean to say development problems are complex?

For me, saying a problem is complex is akin to saying it is economic, or that it is ecological, or anthropological. Complexity works as a lens, and as an area of transdisciplinary academic and practical work that can be called a ‘science’ in itself, or a movement within existing disciplines (e.g. see Beinhocker’s book on what complexity means for economics).

Calling a problem ‘complex’ is a shorthand for saying that it has certain important aspects that we can best understand through a complexity lens, and that we can use explanatory and predictive tools generated by theory and empirical evidence to help address it. For example, social network analysis uses the theory of networks and empirical results on how they function in society to illuminate, explain and predict certain types of phenomena and behaviour. However, challenges are often termed ‘complex’ as an excuse for inaction or failure. Complex problems and difficult problems overlap, but they are not the same thing.

3) Does it matter when development problems are complex?

3) Does it matter when development problems are complex?

In a word, yes. Complex problems present challenges for the well-established instruments of public policy and administration. No matter how anyone describes ‘complexity’, I can guarantee that the reason complexity matters comes down to one or more of three challenges:

1. Distributed capacities: the knowledge and capacities required to tackle problems are spread across actors without strong, formalised institutional links.

2. Divergent goals: inherent to many problems are divergent interests, competing narratives or conflicting goals.

3. Uncertain change pathways: it is unclear how to achieve a given aim in a given context, or change processes involve significant, unpredictable forces.

In researching my working paper of 2011, I was struck by the strength of these three themes across such a broad range of bodies of knowledge. None of this is new: uncertainty and divergence have been central elements of most definitions of complexity for decades. Outside complexity science, the terms have been used to classify different types of policy problems by the likes of Hisschemöller and Hoppe (see Hoppe’s recent book on the governance of problems).

The problem of ‘distributed capacities’ is often highlighted separately or assumed to result from the other two, but it represents a strong theme in the work on systems theory, complex adaptive systems and elsewhere. All three factors have been highlighted as central challenges for guiding change processes under the guise of ‘development as process’, or with relation to learning processes in community development as far back as 1980.

4) Why does this matter? And how much?

It renders many of our tools inappropriate. In many cases our established tools for public policy, programming, and administration are founded on ideas of concentrated capacities, agreed goals, and relatively clear or stable change pathways. When these tools are applied to complex problems, the result is typically one of two effects: formal systems either become meaningless box-ticking exercises, or they actively impede achievement of goals, putting in place perverse incentives and guaranteeing aims are not met. Evidence both can be seen in the reams of research on the log frame, or by a UN-wide evaluation on results-based management that found limited to no evidence of any utility of the system, despite the great amount of money spent.

I think this kind of idea was behind Ros Eyben et al’s ‘big push back’ (now forwards), and Andrew Natsios has argued that both symptoms emerge from the clash of the counter-bureaucracy and development, which sees implementation squeezed and neglected due to overzealous design and process requirements from agency HQs.

It is hard to quantify how much this matters. One could partially estimate this by chalking up the cost of inappropriate agency-wide reforms as a partial waste, but it is impossible to estimate on a system-wide level the value of opportunities missed due to rigid tools. Evidence on management models is rarely conclusive, and importing new ideas into public policy and programming will always need to proceed based on careful assessments of problems with existing systems, but a certain amount of ‘faith’ is required to start with a new approach (for example New Public Management spread like wildfire across the public sector without its impact having been robustly assessed beforehand).

But what principles should this new approach be based on? Tomorrow, I look at the ‘so what’ question: what do agencies need to do differently?

November 3, 2013

How can Complexity and Systems Thinking end Malaria?

This is complexity week on the blog, pegged to the launch of Ben Ramalingam’s big new book ‘Aid on the Edge of Chaos’ at the ODI on Wednesday (I get to be a discussant – maximum airtime for least preparation. Result.)

discussant – maximum airtime for least preparation. Result.)

So let’s start with a taster from the book that works nicely as a riposte to all those people who say (sometimes with justification, I admit) that banging on about complexity is just a lot of intellectual self-indulgence (sometimes they’re not so polite). We know what works, why complicate things? Hmmm, read on:

‘Kenya’s Mwea region is especially prone to malaria because it is an important rice-growing region, and large paddies provide an ideal breeding ground and habitat for mosquitoes. The application of insecticides and anti-malarial drugs has been widespread, but there has been a marked rise in resistance among both mosquitoes and the parasites themselves.

A multidisciplinary team developed and launched an eco-health project, employing and training community members as local researchers, whose first task was to conduct interviews across four villages in the region, to give a first view of the malaria ‘system’ from the perspective of those most affected by it.

The factors involved were almost dizzyingly large in number—from history, to social background, to political conflicts. A subsequent evaluation of the programme referred to this as an admirable feat of analysis.

Using a systems analysis approach that placed malaria in the wider ecological context was a critical part of the programme design:

‘The approach can be compared to using a camera with a zoom lens. The zoom brings the problem into sharp focus – in this case, a mosquito infecting a person with malaria. As the lens pulls back, other elements are brought into the picture: poverty in the villages; farming practices in the rice fields . . . this ‘wide-angle’ view helps researchers to determine the reasons behind the malaria statistics and to develop possible interventions. ‘

‘The approach can be compared to using a camera with a zoom lens. The zoom brings the problem into sharp focus – in this case, a mosquito infecting a person with malaria. As the lens pulls back, other elements are brought into the picture: poverty in the villages; farming practices in the rice fields . . . this ‘wide-angle’ view helps researchers to determine the reasons behind the malaria statistics and to develop possible interventions. ‘

Particularly noteworthy causative factors were the unforeseen effects of a local resistance movement, whereby farmers had decided to exert local control on irrigation systems, overturning a system of national government control that dated back to the colonial era and was associated with continued impoverishment.

However, the change led to ‘agricultural chaos in which farmers plant when and where they want’, pushing up both the mosquito population and the number of malaria cases. Mwea also supports a substantial cattle population, which provides an alternative blood source for mosquitoes: the village with the highest number of mosquitoes per household also had the highest cattle population and the lowest malaria prevalence.

A range of solutions were developed and tested, all of which saw a shift away from the ineffective standard medical responses. For example, better coordination of farmers led to a reduction of the paddy flooding time. Rice planting was alternated with soya, a dry crop, which both reduced the mosquito population and improved villagers’ diets.

Other strategies included the maintenance of cattle populations as bait; the introduction of naturally occurring bacteria to kill mosquito larvae at peak breeding times; planting mosquito-repelling plants around houses; and ensuring vulnerable groups like children and pregnant women always used bednets at night.

A subsequent assessment of the ‘integrated malaria management approach’ found that cases of malaria at the community hospital had declined steadily, from 40 per cent at the start of the project in 2000 to less than 10 per cent in 2004 and zero in 2007, and that the single biggest element of the community-based malaria control strategies consisted of ‘environmental management’ approaches. Through the System-wide Initiative on Malaria and Agriculture, the Mwea experience is now being disseminated across the country, with the goal of finding ways to reduce malaria while improving people’s health and productivity.’

from 40 per cent at the start of the project in 2000 to less than 10 per cent in 2004 and zero in 2007, and that the single biggest element of the community-based malaria control strategies consisted of ‘environmental management’ approaches. Through the System-wide Initiative on Malaria and Agriculture, the Mwea experience is now being disseminated across the country, with the goal of finding ways to reduce malaria while improving people’s health and productivity.’

Tomorrow ODI’s Harry Jones will take stock of where we’ve got to on complexity and development.

November 1, 2013

No Woman No Drive (just in case you haven’t seen it, or you want to watch it again)

I tweeted this at the start of the week, and anyway it’s gone viral (over 5 million hits in 4 days), so loads of you will have seen it, but for those who haven’t, here’s a sweet sweet piece of political satire. No Woman No Drive (about Saudi Arabia, natch). Enjoy. And a lesson for campaigners? Humour and song can get you to numbers that angry press releases can only dream of. Bit of background on Hisham Fageeh, the 26-year-old comedian behind the hit, here. All together now, ‘ova-ovaries, all safe and well……’

And just because it’s nearly the weekend, here’s the awesome original.

Will the next generation of thinktanks be more NGO-friendly? Geoff Mulgan on ‘do-tanks’ (sorry)

I don’t often listen to lectures online – in these ADHD times, a 4 minute youtube video is usually my limit (unless it’s Breaking Bad or The Wire, of  course). But I’m glad I made an exception for this lecture on ‘how do thinktanks think’ by Geoff Mulgan. No tricks, no powerpoint, just a lot of brainpower. Which is what you would expect from a serial policy entrepreneur who currently runs NESTA, set up the Demos thinktank and ran Tony Blair’s Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit.

course). But I’m glad I made an exception for this lecture on ‘how do thinktanks think’ by Geoff Mulgan. No tricks, no powerpoint, just a lot of brainpower. Which is what you would expect from a serial policy entrepreneur who currently runs NESTA, set up the Demos thinktank and ran Tony Blair’s Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit.

There’s a lot to talk about in here – for example, the application of evolutionary theory to ideas (variation, selection and amplification, with different kinds of thinktank and other policy organizations specializing in different stages).

Mulgan notes that the numbers of thinktanks is growing rapidly. Why? Partly for lack of alternatives:

Political parties are no longer seen as being good at research (in the UK they used to have large research departments. No longer.)

The permanent civil service is not good at generating ideas and policies

Universities, previously decisive (1940s-70s) are less able to deliver these days. What happened to them? A dramatic expansion of their teaching role and an economic boom has coincided with a decline in their legitimacy as a source of new ideas.

He also has a nice line in kiss and tell:

‘One of my jobs in government was reviewing the Private Finance Initiative. This was an example of public private partnerships, which had spread all over the world. What was striking was that they were introduced with no way of showing if they worked or not. When we did do a review, it was pretty clear that the majority of the PFIs were not were value for money. I was then phoned by the then Deputy Prime Minister and the Chancellor, demanding that any of this analysis be suppressed and not reach the public, because it was too threatening. Fortunately the policy did change. The key point was that a set of new ideas was introduced on a large scale with no evidence, no evaluation and no scrutiny. And the same was true of most of the policies which came out of the neoliberal thinktanks.’

But where he is at his most interesting is in discussing the shift from thinktanks to ‘do tanks’ (an appalling expression, I know, but bear with me).

‘Previous generations of thinktanks fell down on demand – they produced lots of clever, but largely ignored, papers. So the UK government’s Social Exclusion Unit (which he also ran) and then the Strategy Unit moved towards problem-based projects, with decision makers involved from the beginning.’

Mulgan cites today’s UK Behavioural Insights Team, which runs experiments, assembles innovation teams on particular problems etc as an example of a 21st century do-tank. Intellectual predecessors include the Young Foundation, which (you guessed it), he also ran for several years. The Foundation incubated new organizations including the Open University, the Which consumer magazine and more recently, Studio Schools.

Mulgan cites today’s UK Behavioural Insights Team, which runs experiments, assembles innovation teams on particular problems etc as an example of a 21st century do-tank. Intellectual predecessors include the Young Foundation, which (you guessed it), he also ran for several years. The Foundation incubated new organizations including the Open University, the Which consumer magazine and more recently, Studio Schools.

If you think about this from an NGO perspective, it gets pretty interesting. We may not always be that great at abstract/conceptual thinking, but we love doing stuff. So could organizations like Oxfam get into the do-tank business? It seems to me we are pretty well placed, in that we have programmes around the world, working on a range of issues, and established systems for measuring impact and learning lessons. In some ways we’re doing this already, but the focus is usually more on the doing than the thinking (or testing research findings in the field). Our global programmes, like Raising Her Voice (on women’s empowerment) or the Enterprise Development Programme (supporting small and medium enterprises) could provide an entry point for do-tank style simultaneous think-and-test across several countries and continents.

Maybe it’s time to set up some do-tank partnerships, working with local partners and academic institutions (South or North), and start looking for funding? I’m off to Delhi next month to discuss a proposed programme to do pretty much this, looking at governance in fragile states. Watch this space.

And here’s Geoff:

October 30, 2013

The Idealist: a brilliant, gripping, disturbing portrait of Jeffrey Sachs

For The Idealist, Nina Munk, a Vanity Fair journo , stalked Jeffrey Sachs for six years, focusing on his controversial Millennium Villages Project (MVP). She interviewed the man, sat in on his meetings with bigwigs, and hung around the Millennium Villages to find out what happened when the Prof’s entourage moved on.

, stalked Jeffrey Sachs for six years, focusing on his controversial Millennium Villages Project (MVP). She interviewed the man, sat in on his meetings with bigwigs, and hung around the Millennium Villages to find out what happened when the Prof’s entourage moved on.

The result is more subtle than a simple hatchet job. She portrays Sachs as a man of almost pathological drive and egotism, which both leads to big successes (massive victories on distribution of free anti-malarial bednets for example) and to a refusal to listen or learn from criticism. He comes across as a kind of uber-campaigner, devoid of doubt, absolutely refusing to take no for an answer, dismissive (often in highly personal terms) of anyone who disagrees with him.

There are some memorable vignettes, captured by Munk’s unblinking observation. Sachs lecturing Uganda’s bored President Museveni about boosting farm yields with free fertilizer, when all the President wants is his cup of tea, concluding (as he leaves) ‘This is not India or China, Professor. There are no markets. There is no network. No rails. No roads. We have no political cohesion.’

Where next?

Or a horrendous confrontation with aid donors in a posh Tanzanian hotel. Sachs asks to ‘speak briefly’ and launches into a lecture on how to end Tanzania’s poverty and the case for distributing bednets. Any questions? Silence for a full minute, then this from USAID head Pamela White: ‘I don’t want to argue with you Jeff, because I don’t want to be called ignorant or unprofessional. I have worked in Africa for 30 years. My colleagues combined have worked in the field for one hundred plus years . We don’t like your tone. We don’t like you preaching to us. We are not your students. We do not work for you.’

Completely undeterred, Sachs goes off to his next meeting and persuades Tanzania’s president of the case (against donor opposition) for free bednets.

To which an activist might say ‘see what a great campaigner he is? He thinks big; he brooks no opposition. He gets it that ‘they always say no until they say yes’. He’s a role model!’

And they’d be partly right – think Jubilee 2000, or access to medicines, or the Arms Trade Treaty – all of them were opposed by sensible experts with ‘years in the field’ saying it was impossible. Until people said yes.

But what if Sachs is wrong? Where does he get his cosmically forceful opinions and recommendations from? It certainly doesn’t seem to be from listening to poor people (listening clearly isn’t his thing). The bednet hero is also the guy behind disastrous structural adjustment programmes in Russia and Bolivia.

And whenever he moves beyond simply lobbying for more aid cash, he seems to come unstuck. Nowhere more so than the MVPs. Munk steps smartly between the global Sachs bandwagon and the slow grind of the village projects. She gets to know both villagers and African MVP staffers, charting their hopes, initial successes and (eventually) disillusion as the money runs out and/or things go wrong. The MVPs follow the arc of previous ‘big push’ efforts such as Integrated Rural Development – new crops rot in the absence of roads or markets; stuff gets stolen; governments fail to allocate cash to fill new schools and hospitals with staff and equipment. Technical fixes founder because there is no understanding of (or interest in) power, politics or how stuff happens (or doesn’t).

By the end of the book, Munk portrays Sachs as a slightly tragic figure, bored by the albatross of the MVPs, whose bubble has been burst by failure and a refusal to acknowledge the crescendo of criticism over its lack of independent evaluation of its $120m spending. Sachs is now ‘like a sawed-off shotgun, scattering ammunition in all directions’, in tweets on the Eurocrisis, climate change, Robin Hood Tax, energy, News Corporation corruption. Sachs’ even becomes a bit of a joke when he nominates himself for World Bank president.

Mind you, I don’t think Sachs sees it that way. Here he is today, making the case for more aid for the Global Fund.

The book ends quoting Sachs: ‘You can have a firm conviction even in an uncertain world – it’s the best you can do, actually – and that is the nature of

So where's the millennium village?

my conviction.’

But for me this also shows the limits to conviction, unless it is accompanied by lots of other stuff – humility, listening deeply to the people you are trying to help, not dismissing your critics, admitting and learning from failure. Even a steamroller (especially a steamroller) needs to be pointed in the right direction.

Absent all those, Sachs reminds me of some literary figure, a tragic hero battling to change the world for the better (in his eyes), brought low by his own arrogance, the machinations of lesser beings and the messiness of reality.

I asked people via Twitter for suggestions for who that literary character might be. A Russian – Pierre in War and Peace? Maybe Depardieu’s character in Jean de Florette? I can’t believe Shakespeare hasn’t got such a figure – any nominations?

For other reviews see here.

Getting to the ’so whats’: how can donors use political economy analysis to sort out bad governance?

Close but no cigar. Just been reading an ODI paper from a few months ago, Making sense of the politics of delivery: our findings so far, by Marta Foresti, Tam O’Neil and Leni Wild. It’s part of the ODI’s excellent stream of work on governance and accountability (see my review of David Booth and Diana Cammack’s book) and repays close study.

The starting point is the widespread disillusionment in DFID and elsewhere with ‘political economy analysis’ (PEA), memorably summed up by Alex Duncan’s definition of a political economist as ‘someone who comes and explains why your programme hasn’t worked’:

‘There is no doubt that PEA has helped answer some of these questions [why stuff doesn’t work]. Yet many would say that researchers have not found a middle ground between generality and specificity. On the one hand, the use of catch-all concepts, such as political will or unspecified incentives, fail to provide enough analytical purchase on which to hang entry points for reform. On the other, if we view every context and problem as sui generis, experience cannot be used to construct theories of change that include learning across programmes and contexts.’

So ODI has been trying to apply PEA, working with governments and donors on health, water, sanitation, justice and security and social protection in Malawi, Nepal, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Sri Lanka.

The result is ‘problem driven PEA’ – the ODI’s big new idea, which has substantial overlap with Matt Andrews’ Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation.

‘Problem driven PEA is structured around three main dimensions:

Problem identification: identifying the specific ‘problem’ to be addressed or those poor outcomes to which political economy issues appear to contribute.

Diagnosis: This has two components: (i) Structure: identifying those systemic features that help to explain why the problem persists (e.g. historical legacies, geographic and social features, geopolitics, and the ‘rules of the game’ that underpin power relations); and (ii) Agency: identifying the incentives that shape actors’ behaviour, including key motivations, decision logics and power dynamics. Crucially, analysis needs to look at the interaction of both structure and agency, and can draw on a varied toolbox of relevant analytical concepts.

What can be done: Identification of plausible theories of change and assessment of the range of potentially viable entry points (selection of appropriate modalities, timing and sequencing of interventions, and so on)’

Which bears more than a passing resemblance to the ‘Power and Change cycle’ regularly discussed on this blog.

And their findings of what works on the ground (or at least a bit closer to it than the ivory towers of London or Harvard)?

Aid modalities: External actors can play beneficial roles in government efforts to address political constraints if they adopt appropriate approaches. Six factors appear important to enable aid-funded activities to gain domestic traction:

Identify and seize windows of opportunity: exploit country-led imperative for change.

Focus on reform of goods and services with tangible political pay-offs.

Don’t focus on ideal models; build on what exists and get current policy and legal mandates working.

Move beyond reliance on policy dialogue and focus instead on making existing systems deliver.

Bear transaction costs to facilitate problem-solving and local collective action.

Ensure adaptation by learning.

Arm’s length aid: An ‘arm’s length’ model of engagement and organisation may be best placed to help people in developing countries build the institutions that enable them to act in their collective long-term interests. Such models work through organisations that offer advisory services directly to governments and other public bodies in developing countries and have had some success as brokers of collective action and/or facilitators of change. Examples include the Africa Governance Initiative, the Budget Strengthening Initiative and TradeMark East Africa. Donors should consider delivering more aid in this way.

Arm’s length aid: An ‘arm’s length’ model of engagement and organisation may be best placed to help people in developing countries build the institutions that enable them to act in their collective long-term interests. Such models work through organisations that offer advisory services directly to governments and other public bodies in developing countries and have had some success as brokers of collective action and/or facilitators of change. Examples include the Africa Governance Initiative, the Budget Strengthening Initiative and TradeMark East Africa. Donors should consider delivering more aid in this way.

Great, in that the ODI work really is starting to address some of the criticisms of PEA. I particularly like the recognition of the importance of critical junctures/windows of opportunity, and a real effort to understand why change isn’t happening before outsiders jump in. Why no cigar? Because in this rendering of reality, the world is apparently made up of only of donors and states (and of course researchers). No-one else matters. Nothing on the coalitions of disparate actors (state and non-state) that can drive or block change, or create the desire (or at least perception) among elites that change is needed. Civil society organizations, faith organizations, Diasporas, business associations etc etc.

But this quibble aside, this is all part of a very exciting effort to really get to grips with the issues of governance and institutional reform.

Update: see comments for update/response from ODI

October 28, 2013

Social inclusion and concentration of wealth – what the World Bank gets right and what it misses.

This guest post comes from Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva, Oxfam Head of Research, (@

rivefuentes)

No one expects the World Bank to be a simple organization. The intellectual and policy battles that occur inside the Bank are the stuff of wonk legends – I still remember the clashes around the poverty World Development Report in 2000/2001. This is not a criticism. One of the strengths of the World Bank is its dialectic nature – I observed that up close when I was part of the WDR on climate change a few years ago.

Kevin Watkins, the new director of the Overseas Development Institute, reminded me recently that in 1974 Hollis Chenery, then Vice President and Chief Economist of the World Bank, published a book titled “Redistribution with Growth: An Approach to Policy”. Kevin writes that the central idea of the book was “that the poor should capture a larger share of increments to growth than their current share. That idea has even more resonance today.”

The current battle inside the Bank seems to focus on the issue of skewed distribution of benefits of development and the problems this causes. On the one side there’s a resurgence of the argument that “growth is good for the poor” that argues there is no difference between “shared prosperity” and plain prosperity, as measured by economic growth; on the other hand, the Bank’s Chief Economist retorted that “[o]verall economic growth is important, but the poor should not have to wait until its benefits trickle down to them”

The new vision of the Bank’s “Shared Prosperity” strategy hints strongly at the issue of equity. There are plenty of references to the ills of large gaps in the distribution of income and wealth. However, there is no agreed goal to reduce inequality as part of the World Bank’s mission.

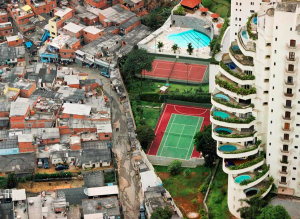

need to tackle both sides of the photo

nd flows of such debates within the Bank may seem arcane, but they matter – where the Bank goes, much of the rest of the aid industry follows. So a new Bank report Inclusion Matters – the Foundations for Shared Prosperity, released along with the new Bank’s strategy, is a welcome addition. It moves beyond income and wealth dimensions and focuses on the relational nature of development. In their words, it highlights “the process of improving the ability, opportunity, and dignity of people, disadvantaged on the basis of their identity, to take part in society”.

It’s necessary reading. Here are some of the bits I found more important from the executive summary:

“The term social inclusion can add to the idea of equality, but much more importantly, it can explain why some inequalities exist or why some are particularly durable (Tilly 1999)” (Page 7)

Also, “Because social inclusion is also at its core about accountability of the state to its citizens, it is as much about occupying political space as it is about having an equitable share in markets and services.” (page 13)

Then “This report argues that reference groups and role models are important in the “capacity to aspire,” […] When individuals from disadvantaged groups see others around them performing at a low level, they set a much lower bar for themselves than they would have if they had belonged to a high-performing group. In addition, they may internalize exclusion in such a way that they do not even bother to try for better outcomes, knowing that people from their group are discriminated against” (page 14)

And “Perceptions of unfairness and injustice and frustration with social and political institutions or with the society at large often reflect individuals’ feelings of powerlessness. Feelings of fairness, justice, and “being part of society” can be manifestations of how much the society recognizes, respects and listens to its members” (page 21)

The arguments in the Report are very solid, well developed and illustrated with vivid examples. I’m mostly in agreement with them, but they seem incomplete. There is more to the problem of social exclusion and it relates to the growing concentration of income and wealth we observe in many countries. As Angus Deaton has written recently in his new book The Great Escape, citing the work by Louis Brandeis, “The political equality that is required by democracy is always under threat from economic inequality, and the more extreme the economic inequality, the greater the threat to democracy”.

Concentration of income and wealth actually hampers this process of social inclusion because it makes political representation harder for the disadvantaged to the benefit of the affluent groups. That’s why the World Bank should include in its vision tackling the growing concentration of income and wealth at the top end of the distribution. This is necessary for the goal of social inclusion and shared prosperity.

Recent exchange on inequality between Ricardo and the Bank here.

October 27, 2013

Impressive progress in guaranteeing the right to food in poor countries (Olivier de Schutter’s final big report to the UNGA)

UN Special Rapporteurs are independent experts, appointed (but not paid, I think) by the UN to beaver away to raise important issues such as disability, indigenous peoples, or torture. They include some bright stars – important thought leaders on the international development stage such as Magdalena Sepulveda, UNSR on extreme poverty and human rights. But the star that has shone brightest, at least in my corner of wonkland, is Olivier de Schutter, the UN’s indefatigable Special Rapporteur on the right to food.

disability, indigenous peoples, or torture. They include some bright stars – important thought leaders on the international development stage such as Magdalena Sepulveda, UNSR on extreme poverty and human rights. But the star that has shone brightest, at least in my corner of wonkland, is Olivier de Schutter, the UN’s indefatigable Special Rapporteur on the right to food.

On Friday, Olivier delivered his final report to the UN General Assembly, after six hyperactive, globe-trotting years. Here are some highlights from a characteristically well-written and up-beat farewell on the big stage (although he doesn’t step down til next May, and doubtless will produce more papers before he goes). It is littered with fascinating examples of impressive progress in ensuring the right to food:

“At a time when multiple, conflicting visions for food security have been put on the table, it is impressive to see so many States adopting laws, policies and strategies to realize the right to food, and so many people driving forward what is now a global right to food movement.

Where progress has been made in realizing the right to food, it is down to the multiple interlocking contributions of different State and non-State actors who make each other accountable.

The first step is for Governments to give the right to food legal grounding, by writing it into constitutions and into law. Over the past decade, countries in Latin America and Africa have blazed a trail that others can now follow.

South Africa, Kenya, Mexico, the Ivory Coast and Niger have already given direct constitutional protection to the right to food, while reform processes are under way in El Salvador, Nigeria, and Zambia.

Right to food framework laws, often taking the shape of ‘Food and Nutrition Security’ laws, have been adopted in Argentina, Guatemala, Ecuador, Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Honduras, with several other Latin American countries in the process of adopting similar measures.

Countries including Uganda, Malawi, Mozambique, Senegal and Mali have adopted, or are in the process of adopting, framework legislation for agriculture, food and nutrition that enshrines rights-based principles of entitlements and access to food.

Treating food as a human right brings coherence and accountability. It helps to close the gaps by putting food security of all citizens at the top of the decision-making hierarchy, and making these decision-making processes participatory and accountable.

Food security laws and policies based on rights and entitlements – to productive resources, to accessing foodstuffs, to social protection – is ‘food security-plus’. It can transcend changes in the political, economic and agricultural landscape and make lasting inroads against hunger.

Food security laws and policies based on rights and entitlements – to productive resources, to accessing foodstuffs, to social protection – is ‘food security-plus’. It can transcend changes in the political, economic and agricultural landscape and make lasting inroads against hunger.

Courts: some landmark rulings for the right to food:

The South African High Court ordered a revision of the Marine Living Resources Act and the creation of the Small-Scale Fishers Policy to ensure the socio-economic rights of small-scale fishers (2012).

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the ECOWAS Court of Justice ECOWAS ruled that Nigeria violated the right to food of the Ogoni people by failing to protect their land from environmental damage in the Niger delta (2012).

Following public interest litigation, the Indian Supreme Court ruled that various social programmes should be expanded and implemented to provide a basic nutritional floor, based on the constitutionally protected ‘right to life’ (2001).

In Nepal, the Supreme Court issued an interim order in 2008 for the immediate provision of food in a number of districts which food distribution programs were not reaching, in line with constitutional requirements.

National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs)

NHRIs, such as national Human Rights Commissions, Ombuds [urgh, is that a word?!] Institutions, or Human Rights Procurators, are a crucial part of the apparatus. They can play a leading role in monitoring compliance with the right to food, examining complaints filed by aggrieved individuals, seizing judicial authorities or triggering action by food and nutrition security councils.

In Argentina, the National Ombudsman requested in 2007 that the Supreme Court order the national State and the Government of Chaco Province provide food and drinking water to the province’s indigenous Toba communities.

In Guatemala, the Human Rights Procurator’s Office has a mandate to monitor the implementation of national FNS policy, and has flagged up coordination failures and funding deficiencies.

The Human Rights Commission in Uganda helped to influence the country’s 2011-16 Food and Nutrition Policy by recommending a rights-based approach.

Civil-society has an indispensable role to play at every level: driving forward right to food movements, participating in the design of policies, taking part in monitoring, and developing new forms of accountability.

The 2011 reform to insert the right to food into the Mexican constitution followed 20 years of advocacy from civil society groups, under the “Frente por el Derecho a la Alimentacion.”

Brazilian civil society established its own National Rapporteur for Human Rights in Land, Territory and Food, whose legitimacy allows him/her to become an interlocutor to the authorities.

The Indian Right to Food Campaign uses social audits and right to information laws to assess compliance with Court-mandated decisions, e.g. the distribution of subsidized foodstuffs and the delivery of school meals.

Parliamentarians: The Frente Parlamentario contra el Hambre serves as a network for sharing best practices between Latin American parliaments to encourage the adoption of legislation protecting the right to food, and has sparked the creation of national parliamentary fronts.’

Olivier can take his fair share of the credit for this progress. He’ll be a tough act to follow. Full report here.

October 24, 2013

Aid’s segmented future

This piece was written for a blog discussion on the future of aid, which will double up as a Global Policy ebook, organized by Andy Sumner’s new outfit, the Kings College International Development Institute, King’s College London. It’s all part of the build up to their launch conference on Emerging Economies and the Changing Global Order, 7-8 November.

One of the most pressing challenges for the aid community over the next few decades is segmentation. The scale and nature of aid will become  increasingly differentiated by purpose and recipient. This is currently happening in an ad hoc, piecemeal way, but would benefit from a more systematic approach.

increasingly differentiated by purpose and recipient. This is currently happening in an ad hoc, piecemeal way, but would benefit from a more systematic approach.

Traditionally, aid’s imaginary ‘ideal recipient’ can be caricatured as a politically stable, low income country able to absorb and benefit from large dollar flows of aid. Such countries do still exist, but they are an endangered species. Stable countries are growing their way to middle income status, and an increasing percentage of the poor live in fragile and conflict states (FCS). The Tanzanias and Malawis of this world are becoming the exception, not the rule.

That means that the business of aid is going to become harder. On one hand, aid to FCS will grow, bringing with it a slew of unreliable and/or venal state ‘partners’ and higher chances of failure. Donors will need to move from a high volume/low knowledge to a low volume/high knowledge model: as recent research from the ODI and others has shown. in areas such as governance, good aid in FCS involves building up a deep understanding of the political and social context, and an approach characterized by ‘convening and brokering’, bringing together dissimilar, and often antagonistic players to build trust and find context-specific, ‘hybrid’ solutions to collective action problems. Big volumes of aid can be counter-productive in such contexts.

This means investing more in staff and intellectual partners, and proportionately less in programme spend. It means reducing the frenetic pace of staff turnover so that aid professionals get a chance to really put down roots in a country without having to sacrifice career prospects for doing so. This is the opposite of the current state of aid, with its 2 year staff rotations and the ‘do more with less’ mantra constantly intoned by its political paymasters.

So if brains not bucks are what’s needed, what to do with the excess cash? Big Aid needs to find avenues of ‘political sterilization’, whereby the introduction of large volumes of cash does not undermine political processes. Direct cash transfers are one promising avenue, but there may be others, such as cash on delivery. In the poorer countries, there will still be a case for funding essential services, as long as it doesn’t mess with the political process – not sure what the implications of this are for the future of general budget support, but I suspect, they are not good.

The other side of the coin is what to do in middle income countries, where the main barrier to poverty reduction is one of inequality, rather than absolute shortage of resources. Here the challenge of development is both one of ‘predistribution’ – pursuing labour-intensive, inclusive forms of economic growth, and of ‘redistribution’, through progressive tax and spend policies, as well as redistributive regulation on everything from land tenure to competition policy.

Such issues are a potential minefield for donors. Inequality (let along redistribution) is a far more touchy political topic than poverty. How can donors engage in it without being accused of political interference and shown the door? Should they adopt a more arm’s length approach, working through intermediaries? The alternative (popular with many donors) is exit, but as Andy Sumner has pointed out (with great persistence), that means abandoning a large percentage of the world’s MIC-based poor, and consigning the aid business to an increasingly marginal global role.

Next up, road traffic and obesity?

One aspect of the future of aid involves less, not more, segmentation. The rise of the South and the increasing importance of inequality and redistribution should finally lead to the abolition of an increasingly unhelpful division of the world into North and South. In its place, the aid business should find it easier to move into some more interesting and potentially more fruitful terrain.

First, there will need to be a greater focus on global public goods – solving increasingly pressing collective action problems such as climate change or tax evasion, which require a truly global solution to get over the problem of free riders.

Second, and linked, the ‘policy coherence for development’ agenda will need to focus much more deliberately on ‘how to stop powerful countries and players inflicting harm’. This could cover unfair trade and investment treaties, corporate malpractice, intellectual property rules that prevent knowledge transfer, migration rules that seek to curb one of the most effective and growing flows of resources to poor people around the world – remittances, climate change and potentially catastrophic responses to it such as geoengineering – the list is long.

Third, once the exoticism of aid (epitomised by the traditional fund-raising imagery of brightly dressed peasants brandishing hoes) is replaced by the focus on common problems, a path should open to engagement on a whole new set of issues, where ‘countries formerly known as the North’ actually have huge accumulated knowledge that could be of immense benefit to the rising rest.

Suppose we started with a blank sheet of paper, and decided which issues to spend aid money on based on two criteria – a) how much death and destruction does a given issue cause in developing countries, and b) do the rich countries actually know how to reduce the damage?

If you followed this exercise, you would end up with a radically different aid agenda, with (fearlessly mixing metaphors) a whole series of Cinderella issues coming in from the cold.

Here’s the global death toll (from the new edition of my book, From Poverty to Power, put together by the indefatigable number crunching of Richard King).

These are global figures, and I don’t have a breakdown by developed/developing. That would be important on obesity, but on other issues, the majority of impact is clearly in poor countries – alcohol, tobacco and road traffic for example. And they are precisely the areas where the rich countries have lots of experience in reducing the damage. It’s certainly a lot more straightforward than inventing/discovering new vaccines, or indeed promoting economic growth (hardly the forte of most traditional aid donors in recent years). When researchers put signs in Kenyan minibuses (matatus) urging passengers to criticize reckless driving, injuries and deaths fell by a half (for paper see here).

Yet such subjects currently languish on the outer margins of the development agenda. Where’s the campaign on booze and fag dumping by large corporations in developing countries? Or international seat belt conventions, backed by technical assistance to help governments ratify and implement? Working on such issues would entail aid agencies acting as a dating agency, linking up developing country governments with the relevant centres of expertise at home (state, private sector or academic).

Some final thoughts on the intellectual direction of travel. Firstly poverty is increasingly understood as a multi-dimensional state of identity,

characterized by shame and anxiety as much as by low income. But the pioneering work of OPHI and others has yet to carry across into the kinds of debates on aid and poverty that are the focus of this blog. In addition, the debate on inequality is still largely carried on in terms of income and (at a stretch), assets and access to services. Multidimensional inequality is an essential next step.

Second, our understanding of development increasingly sees it as a complex system, in which change is unpredictable and often unattributable to any given intervention. Yet currently, the operating model of aid funding and evaluation is highly linear – there seems to be every chance of a titanic intellectual clash between the results community and the complexity thinkers. My gut feeling is that the complexity people will lose, because the results people have the ears of the funders – it is therefore important that political scientists and others abandon any lofty ‘it’s all too complex, and measurement is futile’ attitudes, and start helping the results people move from a self-defeating insistence on attribution to a ‘plausible/good enough’ narrative of change. In terms of metrics, this means learning to ‘count what counts’ in terms of empowerment, agency, governance etc.

October 23, 2013

Why does climate change adaptation in Africa ignore politics? Great broadside from Matthew Lockwood.

My friend Matthew Lockwood has a habit of asking really big, sensible questions about politics that change the way you see the world. He was so fed up with what he saw as the lazy, apolitical thinking behind aid in general and Make Poverty History in particular, that he abandoned the development scene, writing The State They’re In: An Agenda for International Action on Poverty in Africa. It’s a brilliant discussion of Africa’s political economy, and a forerunner to much of the work on governance and institutions that I’ve been writing about on this blog.

with what he saw as the lazy, apolitical thinking behind aid in general and Make Poverty History in particular, that he abandoned the development scene, writing The State They’re In: An Agenda for International Action on Poverty in Africa. It’s a brilliant discussion of Africa’s political economy, and a forerunner to much of the work on governance and institutions that I’ve been writing about on this blog.

Since then he’s devoted himself to climate change, first at IDS and now at Exeter University. But he’s found himself facing similar problems – a lack of political analysis that leads to ‘magical thinking’ in which climate lobbyists churn out endless blueprints (greenprints?) on the basis of ‘if I ruled the world, this is how I would fix it’. In response he set up the wonderful Political Climate blog.

Now he’s added to that with a piece on the political economy of climate change adaptation in Africa. It’s in Development Policy Review, which is gated so I’m not going to link to it, but he’s put up a draft here.

Matthew argues that the climate change adaptation ‘community’ has failed to keep up with the improved understanding of governance and institutions in developing countries (see yesterday’s review of the new book by David Booth and Diana Cammack) and is just as naive as Make Poverty History at its hubristic height.

Yep, that should do it. Not.

‘There has been relatively little thinking about the political context of climate adaptation policy in sub-Saharan Africa, what this means for the quality of governance, and the capacity to plan and deliver what are often quite complex policies and programmes. This is all the more surprising given the quantity and depth of what is already known about politics and governance in Africa.’

This really matters because Africa will be the destination of much of the promised $100bn in adaptation funding (itself some pretty magical thinking – where’s it going to come from?!)

‘By failing to acknowledge the constraints of the political and governance context, much thinking about adaptation policy in Africa is unrealistic, and much donor activity is likely to have little effect. Indeed, in some cases, a large increase in climate finance may have a perverse effect, sustaining political systems that undermine the capacity of states to build adaptive capacity. A perspective on adaptation informed by political analysis helps not only to anticipate where particular problems are likely to be encountered, such as specific sectors or locations in a country, but also to point to more effective responses.’

Adaptation policy in Africa, as elsewhere, is largely discussed in as an administrative challenge, requiring lots of technical assistance and cash to build up state capacity, but:

‘It is not clear that, at present, a lack of technical capacity in most African countries is the most binding constraint on adaptation policy, especially given the range of donor-funded technical assistance on offer. For technical assistance to be effective, governments have to be really interested in adopting and applying it to public policy. For guides and toolkits to be useful, there has to be demand for them from a policy actor sufficiently senior and sufficiently committed to the public good. There is some evidence to suggest that, with a few exceptions, this demand is not present.’

Introducing a greater understanding of African politics into the adaptation discussion would help in a number of ways:

Rural adaptation is a large part of the agenda, and in many countries agriculture has hitherto been neglected by African governments (for example in comparison to Asia). Any attempt to promote adaptation in rural areas needs to understand the reasons for this, and develop plausible ways to overcome it.

Fragmentation across government departments (Uganda takes the biscuit, with a cabinet containing 70 ministers) poses a huge challenge to a system-wide issue such as adapting to climate change.

African politics often sidelines precisely the regions or groups most affected by climate change. It is no use saying ‘pastoralists are the future’ in terms of climate change, if governments insist on seeing them as the past, and starving pastoralist areas of investment (when they’re not selling off their land).

of climate change, if governments insist on seeing them as the past, and starving pastoralist areas of investment (when they’re not selling off their land).

What is to stop climate finance (should it ever arrive) having similar impacts on governance and accountability to other ‘curses of wealth’, such as oil and gas? Big issues on absorption, governance and accountability there.

Matthew ends by sketching out an important ‘institutions meets climate change’ research agenda – hope someone is listening.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers