Duncan Green's Blog, page 200

December 12, 2013

What is ‘leverage’? Anatomy of a fuzzword

A few of us were asked recently to unpack one of this year’s fuzzwords – leverage. A fuzzword is a buzzword, but fuzzier – all things to all people etc. So here’s what we came up with – not final, work in progress etc.

people etc. So here’s what we came up with – not final, work in progress etc.

Leverage is working strategically with others in a ‘clever’ way, in order to lever a bigger change than we could ever achieve on our own. It depends on developing a rich web of mutually beneficial relationships and alliances at country, regional and global level. Leverage emerges out of that connectivity.

The starting point is strong, dynamic networks

As far as possible, we need to know people and earn their trust before trying to leverage their involvement.

This means being part of a complex, interdependent and dynamic web of relationships. In this network there are two-way flows of tangible benefits such as funding, revenue, insurance as well as two-way flows of intangible benefits such as knowledge, access to ideas, credibility, influence, real-time data, client/beneficiary perspectives, market information, ability to mobilise large numbers of people, etc.

Such networks may include government departments, specialist INGOs, local networks, local NGOs, private sector businesses, high profile figures, academic institutions and, of course, community members and leaders.

For example, in Oxfam’s work on olive oil in Palestine we have links with the Coady institute in Canada who are world leaders in market facilitation approaches; we have significantly deepened our cooperation with proficient local partners who now work as a single programme team; we have built working relations at all levels with the Palestinian Authority; we have supported the establishment of cooperatives for women and men and are creating autonomous farmers’ federations. We have developed links with the private sector in country, in the Gulf and in Europe and we have used research to deepen our knowledge of the sector and the market. This network is creating the conditions for change that go beyond benefits for a limited number of direct beneficiaries to affect whole olive oil sector.

This approach is not new. For decades Oxfam has been building trust and linkages with a wide range of actors from village to global level in order to combat injustice and poverty.

A leverage approach means we must systematically strengthen these networks at all levels. Leverage is about being far sighted as to what we want to achieve, clear sighted and strategic about who will do it and especially, astute about understanding what kind of actions will create the alliances and momentum we need in order to bring about the big changes we seek.

A menu of approaches: 10 ways to exert leverage

The following approaches fall along a spectrum from innovative to ‘business as usual’. In practice, approaches are likely to combine more than one of these categories. The list is not exhaustive – there are bound to be other variants

1. Leverage through convening/brokering

Bringing a wide range of actors together to work collaboratively within their shared interest

Examples:

Tajikistan Water Supply and Sanitation Network

Sustainable food lab

2. Leverage through new modality

Introducing a new business model, new technology or new delivery mechanism to reach greater numbers for lower cost

Examples:

Farm Africa’s Sidai franchise veterinary model

Jasmine rice producers in Thailand

3. Leverage through exploiting global capability

Maximising the knowledge, networks, know how, systems and reach across Oxfam GB and the confederation to bring significantly more value to key stakeholders

Examples:

Arms Trade Treaty campaign

Bolivia agricultural insurance scheme

4. Leverage through advocacy

Pressing for duty bearers to take up their responsibility to act, e.g. to provide services, enforce laws, ( Covers spectrum from insider (research -> advocacy) to outsider (public campaign))

Examples:

Philippines climate change adaptation fund

Disabled people’s rights in Russia

5. Leverage through peer-to-peer adoption

Supporting the spread of new community or household level models and techniques to neighbouring villages and districts. One method is social franchising (making it clear to others how to copy what you’ve done. Another is frugal innovation (making it purposefully cheap for others to copy or scale what you’ve done)

Examples:

Childline India

6. Leverage through replication

Developing an effective model that is then adopted and adapted by other organisations or government institutions

Examples:

Vietnam child-centred teaching methodology

Niger School Management Committees

7. Leverage through pyramid selling approaches, for example to change public attitudes

Training one group of people who then commit to reach out to and train others, with the expectation that this will continue to grow.

Training one group of people who then commit to reach out to and train others, with the expectation that this will continue to grow.

Example:

We Can End Violence Against Women campaign

8. Leverage through building capacity

Building capacity of key organisations/departments and their staff in government, private sector or NGOs via training, study tours, internships and exchanges

9. Leverage through releasing community potential

Catalysing the effective organisation and use of the physical, natural, cultural, financial, political, institutional and creative assets that are present in communities

Example:

Savings For Change

10. Leverage through ‘grow and go’

Growing independent organisations that go and take on their own life either by creating incubation space for emerging organisations or by spinning off projects into new organisations

Example:

Arid Lands Information Network (ALIN) begun by Oxfam and then hosted within Oxfam has taken on its own life and is now a separate Southern network

New Internationalist magazine, Fairtrade Foundation etc

Feel free to critique, suggest new categories, add examples (plus links) etc

December 11, 2013

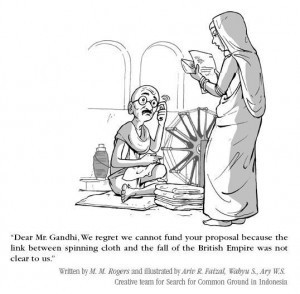

How can campaigners tap corporate largesse without undermining their credibility? Unlocking millions for advocacy

It’s great to be accidentally topical. In the week that Save the Children had to fend off allegations of letting corporate funding influence its campaigns, here’s Oxfam America’s Chris Jochnick (@cjochnick) suggesting a way to accept money (in this case from extractive industries) while staying demonstrably independent

Oxfam was recently approached by a major mining company to help it implement “free prior and informed consent” (FPIC). The company  (rightly) anticipated that it would face future conflict if it didn’t earn community support for its project. It needed an organization with the expertise, credibility and relationships to help it manage this process.

(rightly) anticipated that it would face future conflict if it didn’t earn community support for its project. It needed an organization with the expertise, credibility and relationships to help it manage this process.

For Oxfam, this was a great opportunity – our local partners would have likely supported it, we’ve been championing FPIC for many years, and here was a chance to help implement it in a credible, robust manner with an influential actor. We turned it down – in no small part because of the expense. The company would have been happy to cover our costs, but we couldn’t accept payment. Our campaigning around extractive industries makes it impossible to take money from oil or mining companies.

It’s a common story. As a general rule, donors won’t pay for corporate advocacy or engagement (see interesting breakdown on human rights funding here); and credible advocates won’t take money from company targets. Community groups lack funds to engage with companies meaningfully, and better-resourced NGOs are loath to deploy scarce funds to advise or mediate around conflicts. Those companies out to make good faith efforts to address complex challenges will lack for credible partners and intermediaries (a common lament). The result: watchdogs stick to “naming and shaming”; companies hire consultants; problems fester.

This situation is only getting worse. Companies seeking resources, markets and cheap labor are moving aggressively into poorly-governed countries, exacerbating conflicts and raising a host of new challenges. Efforts to address this “governance gap” have led to a dizzying array of voluntary and global standards, capped by the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (with 1700 people attending the most recent UN Business and Human Rights Forum), but oversight is lacking and funding for these initiatives is woeful.

Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) bring companies and advocates together (e.g. the Fair Labor Association, the Roundtable for Responsible Palm Oil, the Global Network Initiative), but these initiatives are not aimed at funding watchdogs, and, not surprisingly, they struggle to attract and engage advocates. Oxfam recently dropped out of a large MSI targeting oil and mining companies (the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights) in good part because we couldn’t justify the use of staff resources in a process that lacked adequate accountability measures. Other large NGOs — Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Human Rights First – have similar dilemmas; smaller watchdogs – local NGOs, community groups, social movements face even more significant hurdles and are rarely present.

Companies recognize that their bottom line and reputations rely on getting out front of conflicts and have increasingly recognized and adopted human rights commitments. Implementation is now high on everyone’s agenda and watchdogs and stakeholders need to be in that mix. Companies are willing to pay for it. So how do we tap ready and willing corporate largesse for a field that is starving for resources?

Companies recognize that their bottom line and reputations rely on getting out front of conflicts and have increasingly recognized and adopted human rights commitments. Implementation is now high on everyone’s agenda and watchdogs and stakeholders need to be in that mix. Companies are willing to pay for it. So how do we tap ready and willing corporate largesse for a field that is starving for resources?

A genuine solution to this problem – a “Watchdog Fund” – would have to meet four conditions:

Garner corporate funds. In theory, the Fund could be subsidized by a small tax on companies in high risk industries. For governments truly intent on addressing conflict and corruption, underwriting civil society engagement makes eminent sense (though may raise additional issues for watchdogs). Recent legislation in India requiring companies to devote 2% of net profits to corporate social responsibility offers a possible model (interesting blog analyzing it); but in reality, we are still a ways off. In lieu of that, companies will have to be sufficiently incentivized to fund watchdogs. Many companies will have an interest in stronger civil society groups to address complex problems, help level the playing field and advise on novel issues. Companies commonly pay for the right to participate in MSIs that aim to raise standards and bolster transparency/accountability (however weakly) and companies are willing to partner with (and pay for) credible stakeholders. The challenge would be to attract investments in an independent fund, over which companies might have some loose call on services. That’s probably easiest with a handful of companies working on a particular challenge like FPIC or human rights grievance mechanisms (there are many such platforms already bringing companies together).

Designate funding for credible watchdogs. There is no shortage of good environmental, development and even human rights-minded NGOs ready to take funds from any company; but by definition, these groups are too beholden to the companies to serve as credible watchdogs or intermediaries. The Fund would need to target a more “radical”/independent mix of organizations, prepared to work on some particular challenge involving contributing companies.

Define a set of “transformative” activities. The Fund would need to focus on activities that currently go unfunded and that get to the root of complex problems. In particular, the Fund should empower marginalized stakeholders (capacity-building, rights awareness, logistical support for engagement) and foster accountability (transparency initiatives, implementation of rights, oversight processes). It might also fund ‘learning by doing’ experimentation – in complex systems, we often don’t know the answers in advance.

Attract willing watchdogs. This constitutes the main challenge. Credible watchdogs will tend to be suspicious of anything that benefits (or is paid for by) a corporate adversary. For good reason, watchdogs would assume the Fund is aimed at coopting stakeholders and quelling legitimate protests. Green-washing, dividing and conquering, bribing adversaries are familiar approaches of companies operating in conflict environments. Watchdogs will assume similar shenanigans from the Fund and will be reluctant to risk their reputation and credibility by taking part. However, even the most radical organizations take money from foundations with ties to Wall Street and watchdog organizations have willingly joined initiatives funded and driven by company interests (e.g. the various MSIs above).

The key is credible independence – in fact and perception. The Fund would need to be managed in such a way as to convince watchdogs that the financial backers – the company targets – were not influencing the designation of funding. To that end, the Fund would need some kind of a third party institution to control the funds, with credible leadership (e.g. watchdogs on the board), decision-making independent of company donors, no single company representing more than X% of funds, etc.

For a Fund to attract both companies and advocates remains a stretch; but both the demand and opportunity for it grows. The global funding universe for corporate watchdogs could be easily doubled by tapping corporate funds; and forward-leaning companies would be well-served by the investment. A foundation looking to leverage its own funding in this area could do worse than designate some modest funds to exploring the possibilities.

December 10, 2013

Big food companies are moving from charity to rights. With one exception – Associated British Foods

Erinch Sahan (right), a private sector policy advisor at Oxfam GB, brings us up to date with the Behind the Brands campaign, and one particularly recalcitrant company.

This is a story of a campaign on Big Food. A campaign successful in moving a bunch of companies, but struggling with one in particular. It is a story of corporate responsibility, of philanthropy vs transparency, rights and voice. It’s a story of Associated British Foods (ABF).

It is a story of corporate responsibility, of philanthropy vs transparency, rights and voice. It’s a story of Associated British Foods (ABF).

Here’s the campaign

One of our largest corporate-focused campaigns ever, Behind the Brands, is gathering momentum. It focuses on the world’s 10 largest food and drinks companies (the Big 10), challenging them to improve policies on gender, workers, smallholders, land, water, climate change and transparency. These giants of the food trade not only shape what happens in their own operations and supply chains, but set standards that many others follow. With great power (collectively the Big 10 generate $1.1 bn a day), comes great responsibility (was Spiderman really the source for that?). Hence the campaign.

Since we launched in February, we’ve seen the three chocolate giants (Nestle, Mars and Mondelez) take steps to remove the barriers women cocoa farmers face. We’ve seen Coca-Cola release new guiding principles for suppliers on water, General Mills release new sustainable sourcing commitments, Nestle strengthen its commitment to community land rights and Unilever commit to providing training and implement grievance mechanisms for women in their supply chain.

Most impressively, last month Coca Cola made a commitment to land rights for communities affected by land acquisitions. Coke’s move is already starting to resonate through the industry, as suppliers and peers begin to take the issue of community land rights more seriously. Our approach of highlighting the strengths and shortcomings of these global companies seems to be working and we’re sticking with it.

At the heart of the campaign is a scorecard (see below), assessing the policies and commitments of each company, through 276 indicators spanning 7 themes. It was nerdish heaven leading the team of Oxfam super-wonks in putting this together.

ABF languishes at the bottom of the scorecard. Industry insiders and the Guardian tell us that ABF is a different beast. While it owns and runs household food and beverage brands like Twinings, Ovaltine, Kingsmill and Jordan’s, its flagship brand is Primark, a clothing retailer. Unlike the other 9 companies, it also runs sugar farms around the world (it’s the parent of British Sugar and Illovo). It’s a diverse company with seemingly decentralised decision-making.

Sure, ABF is different, but the other nine aren’t identical either. Mars is a private company and Unilever has a major non-food business (shampoos, deodorants etc). While the companies Behind the Brands compares aren’t quite apples and oranges, they are different varieties of apples. ABF is the most different of these ‘apples’, both structurally and culturally. It also says the least about how it does business, which suggests it’s also the ‘bad apple’ among the big 10.

ABF as a company is not as famous as Coca Cola or PepsiCo. So we, and our supporters, have begun focusing on their brands, asking them, via Facebook and Twitter, to tell their parent company to adopt a zero tolerance policy on land grabs. We’ve also been turning up at a few of their brand offices (see picture from Melbourne Australia below, you can tell from the t-shirts and sun), reminding them that more is expected from their parent company.

Here’s ABF’s reaction

ABF has either ignored or dismissed Behind the Brands. When we launched in February, the scorecard showed that ABF discloses less about their supply chains than any of the Big 10. We characterised this as a “veil of secrecy”. Their reaction was to call this “ridiculous”.

ABF has either ignored or dismissed Behind the Brands. When we launched in February, the scorecard showed that ABF discloses less about their supply chains than any of the Big 10. We characterised this as a “veil of secrecy”. Their reaction was to call this “ridiculous”.

ABF’s fresh-off-the-press Corporate Responsibility report (their first since 2010) does, however, include some encouraging steps, including an adoption of a supplier code and some information on the ingredients they buy for their brands. But there remains a gaping hole on the rights agenda, particularly on land rights.

In October, we highlighted the critical role they play (along with Coca Cola and PepsiCo) in the sugar trade, in our report Sugar Rush. We asked each company to commit to a zero tolerance policy for land grabs. ABF’s response, through their subsidiary Illovo (the largest sugar producer in Africa):

“Oxfam criticises ABF and Illovo for refusing to sign a pledge on land ownership. Pledges are cheap and plentiful. The history of Africa is full of them. The true test of any organisation is what it actually does. ABF and Illovo prefer to act on their beliefs and standards rather than pontificate about them.”

So we turned up at their AGM last Friday, handing out leaflets highlighting to shareholders that ABF should implement a zero tolerance policy for land grabs because: (a) this would help some of the poorest people in the world who are losing their land due to land grabbing; and (b) it’s good for business to prevent land disputes and show leadership on this increasingly important issue. Most shareholders were receptive but when Oxfam supporters asked questions inside the event, ABF senior management formally dismissed the idea.

What we’ve learned

ABF says, and genuinely believes, that it is a good company that does not need civil society to drive its sustainability agenda. From what we can tell, its preferred approach is to find a problem and fix it. This explains why ABF, via Primark, took a leadership role in reaction to the Rana Plaza disaster, where it was the first company to publicly commit to paying compensation and signed up (with more than 80 other brands) to a legally binding building safety agreement backed by trade unions and the Bangladeshi government.

But Oxfam isn’t presenting ABF with a disaster to address, only a complex growing global problem which ABF has a part to play in preventing. We do know of reports of ABF being involved in land disputes (including one in Mali portrayed in this documentary) but the thrust of our campaign isn’t “here’s where you’ve done something wrong, now please fix it”; it is to ask for policies that prevent land grabs and for major players like ABF to help make free, prior and informed consent an accepted principle when dealing with community land rights.

We do know of reports of ABF being involved in land disputes (including one in Mali portrayed in this documentary) but the thrust of our campaign isn’t “here’s where you’ve done something wrong, now please fix it”; it is to ask for policies that prevent land grabs and for major players like ABF to help make free, prior and informed consent an accepted principle when dealing with community land rights.

Critically for us, the whole ‘race to the top’ strategy, which has worked so well with other companies, has been met, so far, with a stubborn refusal by ABF to move. But we aren’t giving up on them quite yet. We and our supporters will keep telling ABF that when it comes to land rights, its refusal to explicitly accept that communities should have the right to free, prior and informed consent is not good enough. We stand ready to highlight any positive steps the company takes.

From philanthropy to transparency, rights and voice

We don’t judge the morality of ABF or its management. It does many good things, including through some incredibly generous philanthropy. It sources sugar from smallholder cane growers in Africa and generates jobs in some of the poorest parts of the world. But corporate responsibility is moving on from philanthropy to transparency, rights and voice, and ABF risks being left on the wrong side of history. Progressive companies now increasingly disclose key elements of their business (including details of supply chains and policies) to demonstrate accountability. They stand behind human rights publicly, a systemic commitment that goes beyond charitable efforts to benefit workers, smallholders and communities.

Of course, there’s always the issue of policy vs practice when it comes to CSR. But there doesn’t have to be a trade off. A good company can both stand behind core rights through policies and adopt systems to ensure they are implemented. Though this requires transparency and a confidence in being open about how you do business.

With Coca Cola’s bold step, the land rights of communities are increasingly becoming a mainstream CSR issue. But while rights may be the new black (and the foundation of all corporate responsibility), voice is the next black. Leader companies give workers, smallholders and communities a voice, a real say over the impacts business decisions have over their lives. Laggards don’t. ABF needs to catch up. And when it does, we will be the first to trumpet its decision.

December 9, 2013

The living wage campaign: are we reaching a tipping point in global supply chains?

It’s private sector week here on FP2P. First up, NGOs have been pushing the living wage in their engagement with international companies for at least 15 years, but

Rachel Wilshaw

, Oxfam’s Ethical Trade Manager reckons we might be on the verge of some kind of victory.

Trade Manager reckons we might be on the verge of some kind of victory.

The issue of a living wage is going up the corporate responsibility agenda. Last month, I blogged during Living Wage week about its importance to address in-work poverty. Here I want to discuss the drivers and blockers for a living wage in global supply chains and describe some promising new initiatives that could get things moving.

A commitment to a living wage has been incorporated into the better codes of labour practice – ETI Base Code, SA8000 – since the late 1990s. 27,000 members of one member organisation alone – Sedex – use the ETI code in addition to the direct members of ETI. Yet for a decade, the element stating that ‘Living wages are paid’ has merely been debated, not implemented (with a few exceptions such as Marks & Spencer in garments and Finlays in fresh produce), with companies citing a daunting set of ‘blockers’ that outweigh the ‘drivers’.

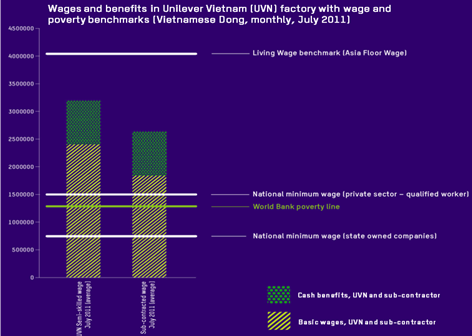

Five years ago two innovations came along to help remove some of the blockers: the Asia Floor Wage campaign, and wage ladder tools.

Asia Floor Wage – a credible methodology for calculating a living wage: This was an initiative of the Asia Floor Wage Alliance in 2009 – a coalition of workers’ organisations in the continent where 80% of global garment production occurs. With support from allies in Europe and the USA, the coalition developed a credible methodology for calculating a wage level based on a ‘family basket’ derived from calorie needs and Consumer Price Indices, assuming that a living wage needs to support two adults and two children. The method enables comparison across countries and figures are updated annually.

Wage ladders – illustrate both the problem and ‘what good looks like’: The innovation of wage ladders – graphics that show wage levels in relation to wage and poverty benchmarks – came from multi-stakeholder dialogue in the garment sector around 2006. Oxfam and Ethical Tea Partnership then borrowed the idea for our study, Understanding wages in the tea industry. The wage ladders developed for us by Ergon clearly illustrate that the wages of tea pluckers in Malawi and Assam fall well below the poverty line, despite meeting the legal minimum.

Oxfam used the ladder tool in another study undertaken with Unilever (see simplified version below). This backed up testimony from workers we interviewed, that wages were well short of a Living Wage, despite easily exceeding the minimum (p.70).

Simplified version of a wage ladder from Oxfam’s report Labour Rights in Unilever’s Supply Chain: From Compliance towards Good Practice

And in our recent Poverty Footprint study of fresh produce with IPL, we used the AFW methodology to calculate that wages of flower workers around Nairobi could be doubled for an additional 5p on a £4 bunch of roses.

The World Banana Forum also used wage ladders to promote understanding of sustainability challenges in the banana industry and develop a plan with social dialogue at its heart.

The Asia Floor Wage provides concrete figures from a grassroots workers’ movement, while wage ladders communicate the issue to a business audience. Oxfam’s experience is that taken together, these have helped companies better understand our concerns about poverty wages and to make commitments to address them.

For instance, a new collaboration is bringing together the tea industry, NGOs and trade unions with support from European companies, certifiers and development agencies. We presented this last week with Ethical Tea Partnership at an international European Conference on Living Wages in Berlin, at which other initiatives were announced, including one by the world’s second-largest clothing retailer, H&M. Starting with two factories in Bangladesh and one in Cambodia, to which it will pay higher wholesale prices. The Swedish company has committed to achieve a ‘fair living wage’ for 850,000 workers in 750 factories by 2018.

Other relevant initiatives and resources include the new Fairwear report, ETI’s Living Wage round-up, the FLA’s Fair Wage Dimensions, Impactt’s Benefits for Business and Workers report, campaigns by Clean Clothes Campaign, Labour behind the Label and War on Want, and more widely the Play Fair protocol and the Bangladesh Accord.

2013 has been a year for cautious optimism that the poverty wages highlighted by campaign reports for more than a decade are finally moving up corporate agendas and starting to result in meaningful action. We hope the innovations and initiatives highlighted here help more companies to embrace this agenda.

December 8, 2013

Ending poverty is about the politics of power: guest piece for the OECD

This guest rant of mine appeared in the OECD’s Development Cooperation Report 2013, published last week. The report, subtitled ‘Ending Poverty ‘, is worth a skim – it’s a good survey of current debates on poverty and aid, with contributions from piles of wonks, followed by a donor-by-donor aid overview.

‘, is worth a skim – it’s a good survey of current debates on poverty and aid, with contributions from piles of wonks, followed by a donor-by-donor aid overview.

A necessary starting point in any discussion of ending poverty is “What do we mean by poverty?” The answer to that question has proved surprisingly fluid in recent years, as crude income definitions of poverty have come under intellectual challenge from a number of quarters (a recurring theme in this Development Co-operation Report).

As long ago as the 1990s, the World Bank’s ground-breaking Voices of the Poor study uncovered a narrative of anxiety, fear and shame – being poor is worrying about what happens if the rickshaw-driving breadwinner has an accident, if a child gets sick and the hospital charges exorbitant fees, if a daughter gets married, or if someone dies and requires an expensive funeral.

Over the past five years, multiple shocks – financial, food prices, climatic and others – have added to this narrative, driving home the importance of volatility as a source of vulnerability in the lives of poor people. More recently, national governments around the world – supported by the OECD and others – have invested seriously in devising new ways to measure well-being and the multiple aspects of poverty beyond income.

This more sophisticated understanding of the nature of poverty means, alas, that “getting to zero” is a chimera because multidimensional poverty is much broader and more entrenched than mere income poverty. Nevertheless, it takes the development debate in important and positive directions in terms of policy (witness the increased emphasis on smoothing mechanisms such as social protection to combat volatility and vulnerability).

Perhaps more importantly, it encourages us to engage with the essentially political nature of poverty, i.e. seeing poverty in terms of power. The Oxfam book From Poverty to Power explains the underlying process of development as the renegotiation and redistribution of power. Power resembles an invisible force field that both links and influences individuals and social groups. The task of those wishing to promote development is first to make such power visible – by understanding how it operates in each situation – and then to understand how power shifts and can be influenced by aid agencies, political movements or civil society organisations.

Oxfam’s experience suggests that power is renegotiated through a combination of both steady and occasionally abrupt change. Steady change grows out of the daily grind of governance and politics and the wonderfully intense public conversation between citizens’ organisations, faith groups, the private sector, the media, academics and policy makers. It propels evolutionary change: the slow but inexorable transformation of attitudes, such as towards the role of women.

There are also moments of rapid shifts in power, driven by wars, economic crises, failures and scandals. Such shocks often provide crucial windows of opportunity in which decision makers suddenly become open to new ideas and answers. For example, it may well take major climate shocks in high greenhouse gas-emitting countries and a consequent political (and perhaps literal) meltdown to open doors and minds to the kinds of drastic solutions needed to avert catastrophic climate change.

Seeing development in terms of a shift from poverty to power induces a welcome sense of optimism. Despite periodic crackdowns by frightened elites, power has indeed been redistributed broadly over the course of the past century: in 1914, only New Zealand, Australia, Finland and Norway allowed women equal voting rights to men; by 1979, a woman’s right to vote had become a universal right under the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

Seeing development in terms of a shift from poverty to power induces a welcome sense of optimism. Despite periodic crackdowns by frightened elites, power has indeed been redistributed broadly over the course of the past century: in 1914, only New Zealand, Australia, Finland and Norway allowed women equal voting rights to men; by 1979, a woman’s right to vote had become a universal right under the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

The assertion of power by people living in poverty is both an end in itself – a crucial kind of freedom – and a means for building social institutions (the state, the market, the community, and the family) that respect people’s rights and meet their needs through laws, rules, policies and day-to-day practices. When individuals join together to challenge discrimination against specific groups – for example, against women, indigenous communities or disabled people – they can transform the institutions that oppress them into ones that serve them.

In contrast to portraying poor people as passive “victims” (of disasters, or poverty, or famine) or as “beneficiaries” (of aid, or social services), this development vision places poor people’s own actions centre stage. In the words of Bangladeshi academic Naila Kabeer, “From a state of powerlessness that manifests itself in a feeling of ‘I cannot’, activism contains an element of collective self-confidence that results in a feeling of ‘We can’.”

The shift from poverty to power is often an extremely local process (even within households, in the case of violence against women), and this raises important challenges for us as outsiders seeking to promote development in poor countries. It means learning to negotiate the fine line between effectiveness and interference. It also means accepting a more humble role in the drama of development: the primary actors are national and the impacts of outside interventions, for good or ill, are probably less extensive than many of us thought.

important challenges for us as outsiders seeking to promote development in poor countries. It means learning to negotiate the fine line between effectiveness and interference. It also means accepting a more humble role in the drama of development: the primary actors are national and the impacts of outside interventions, for good or ill, are probably less extensive than many of us thought.

Getting anywhere near to ending poverty is an inherently political process. The sooner we do-gooders embrace such an understanding, the more likely we are to provide the sort of support that will make a lasting difference.

December 5, 2013

Nkosi Sikelel Iafrika: Nelson Mandela RIP

And here (h/t Ben Phillips) is Mandela’s first ever TV interview, in 1961, while he was in hiding in South Africa.

December 4, 2013

An Uncertain Glory: Dreze and Sen’s fantastic introduction to India and its Contradictions

India dominates many debates on development – home to a third of the world’s absolute ( emerging power with a space programme, a buzzing beehive of political and social activism and experimentation. With their new book, An Uncertain Glory, Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen have given us a brilliant introduction to India’s political and economic ferment, setting out a powerful manifesto on what is wrong with the country, and what needs to change.

emerging power with a space programme, a buzzing beehive of political and social activism and experimentation. With their new book, An Uncertain Glory, Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen have given us a brilliant introduction to India’s political and economic ferment, setting out a powerful manifesto on what is wrong with the country, and what needs to change.

The model of change set out in the book combines active citizenship (Dreze’s speciality – he has been centrally involved in some of India’s most renowned social victories, such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, NREGA – with a commitment to democracy as an act of public reasoning (Sen’s stock in trade).

If I have one criticism of the book, it is with this model of change. It reads a bit like a traditional NGO treatise (OK, rather better researched): here’s the problem, here’s the solution. Now get on with it. Lots of policies, but not much on the politics of how such ideas might come to fruition.

The book sees the drivers of change as expanding education (albeit slower than elsewhere), progressive legislation such as the Right to Information Act, corruption-curbing technology, decentralization and long term shifts in social norms. But the dualism between (good) citizens and (bad/lazy/venal) politicians remains pretty stark: beyond citizen action and public debate, not much sense of how such social and political earthquakes might occur – who are the allies in positions of power? Why so little on religion as both a driver and blocker of change? What coalitions are feasible? What critical junctures may be needed to disrupt the political stasis? What, in short are the politics of successful reform?

The commitment to an activist form of democracy is picked up in one of the book’s intellectual threads – the comparison between China and India, not on who’s going to be the big superpower (left), but on social progress.

The commitment to an activist form of democracy is picked up in one of the book’s intellectual threads – the comparison between China and India, not on who’s going to be the big superpower (left), but on social progress.

India’s commitment to democracy was a unique experiment in such a poor country and has both been an achievement in itself, and a means of avoiding the famines that have characterized autocracies, including China (one of Sen’s most famous contributions has been to show that democracy leads to the avoidance of famine). But beyond that, when it comes to ending poverty and ensuring the right to everything from decent education to flush toilets, China has been far more successful.

Dreze and Sen focus on inequality, delving into India’s ‘unique cocktail of lethal divisions and disparities’– class, gender, caste, religion (see yesterday’s post for their brilliant overview on caste).

The over-riding feature of this inequality, both as symptom and cause, is the ‘Indian folly’ of an abysmal education system. There is a fantastic quote from Tagore: ‘the imposing tower of misery that today rests on the heart of India has its sole foundation in the absence of education’. The origins of the education crisis go all the way back to independence – India’s first five year plan in 1951 favoured self-financing handicraft as the best way for poor children to learn.

An Uncertain Glory explores India’s miserable underperformance on health and education relative to neighbours such as Bangladesh and Nepal, even while its economy has grown much faster. Over 40% of India’s kids are underweight, compared to 25% in Sub-Saharan Africa, yet children’s weights did not improve during a growth surge from 1998-2005 and anaemia even increased. It takes a particular brand of incompetence and neglect for decades of stellar growth to have no apparent impact on India’s sky-high levels of under-nutrition.

The disparity with Bangladesh is in large part down to the position of women, combined with a focus on basic health care and elementary education. Some stats: Proportion of households practicing open defecation – India 55%; Bangladesh 8%. Proportion of fully immunized 1-2 year olds: India 44%; Bangladesh 82%. I would love to read the equivalent book on how Bangladesh has so comprehensively outperformed its giant neighbour. Any suggestions?

Regional variations within India provide just as much ammunition to social reformers. Kerala’s track record is well established, but Tamil Nadu is if anything even more impressive. On issues such as missing women (the result of the increasing use of sex-selective abortion), there is a diagonal fault line dividing India between progressive, effective states to the East and South, and the opposite in the West and North.

An Uncertain Glory covers all the standard issues – social protection, targeting v universalism, cash transfers v food, private v public, but also a few non-usual suspects, (energy, the role of the media) and is a goldmine of killer facts for activists. The writing is more punchy and accessible than Sen’s normally pretty unfathomable prose – presumably down to Dreze’s influence as an activist and ‘organic intellectual’.

The book ends with a wonderful quote from Ambrose Bierce: ‘Patience is a minor form of despair, disguised as a virtue’. To those impatient with India’s failure to turn democracy and growth into a new life for hundreds of millions of its citizens, this book will be a godsend.

December 3, 2013

Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze on the changing nature of India’s caste system

This excerpt comes from An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions, a wonderful new book from Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen. Review tomorrow.

‘It is often argued that caste discrimination has subsided a great deal in the 20th Century. Given the intensity of caste discrimination in India’s past, this is true enough, without making the present situation particularly close to equality. In large parts of India, in the old days, Dalits were not allowed to wear sandals, ride bicycles, enter temples or sit on a chair in the presence of higher castes – to give just a few examples of the vicious system of humiliation and subjugation that had developed around the caste system.

Many of these discriminatory practices have indeed declined or disappeared, thanks to the spread of education, movements of social reform, constitutional safeguards, as well as economic development, and also, of course, growing political resistance from the victims of discrimination.

This trend is far from uniform. Some caste prejudices, such as the disapproval of inter-caste marriages, remain rather strong today among many social groups. And while caste divisions are subsiding in large parts of the country and society, they have also been making inroads where they did not exist earlier, for instance among various Adivasi, Muslim, Sikh and Christian communities. More importantly, however, caste continues to be an important instrument of power in Indian society, even where the caste system has lost some of its earlier barbarity and brutality…..

The dominance of the upper castes seems to be, if anything, even stronger in institutions of ‘civil society’ than in state institutions. For instance, in Allahabad the share of the upper castes is around 80% among NGO representatives and trade union leaders, close to 90% in the executive committee of the Bar Association, and a full 100% among office bearers in the Press Club. Even trade unions of workers who belong mainly to disadvantaged castes  are often under the control of upper-caste leaders. There is some food for thought here about the tendency even of anti-establishment movements in India to reproduce, within their own political activities, images of the old divisions……

are often under the control of upper-caste leaders. There is some food for thought here about the tendency even of anti-establishment movements in India to reproduce, within their own political activities, images of the old divisions……

One of the barriers to rectifying caste-based discrimination is that caste has become virtually unmentionable in polite society in India, not just because any caste-based practice has to face legal challenge but also because any kind of caste consciousness is taken to be socially retrograde and reactionary. This can be superficially justified as a contribution to the obliteration of caste consciousness, but it does not help to understand the world for what it is, let alone change it.’

December 2, 2013

How do you measure the difficult stuff (empowerment, resilience) and whether any change is attributable to your role?

In one of his grumpier moments, Owen Barder recently branded me as ‘anti-data’, which (if you think about it for a minute) would be a bit weird for anyone working in the development sector. The real issue is of course, what kind of data tell you useful things about different kinds of programme, and how you collect them. If people equate ‘data’ solely with ‘numbers’, then I think we have a problem.

anyone working in the development sector. The real issue is of course, what kind of data tell you useful things about different kinds of programme, and how you collect them. If people equate ‘data’ solely with ‘numbers’, then I think we have a problem.

To try and make sense of this, I’ve been talking to a few of our measurement wallahs, expecially the ones who are working on a bright, shiny new acronym – take a bow HTMB: Hard to Measure Benefits. That’s women’s empowerment, policy influence or resilience rather than bed nets or vaccinations. It fits nicely with the discussion on complex systems (Owen’s pronouncement came after we helped launch Ben Ramalingam’s book Aid on the Edge of Chaos).

A few random thoughts, (largely recycled from Claire Hutchings and Jennie Richmond):

Necessary v Sufficient: there was an exchange recently during the debates around the Open Government summit. IDS researcher Duncan Edwards pointed out that it simply cannot be proven that to “provide access to data/information –> some magic occurs –> we see positive change.” To which a transparency activist replied ‘it’s necessary, even if not sufficient’.

But the aid business if full of ‘necessary-but-not-sufficient’ factors – good laws and policies (if they aren’t implemented); information and data; corporate codes of conduct; aid itself. And that changes the nature of results and measurement. If what you are doing is necessary but not sufficient, then there is no point waiting for the end result and working backwards, because nothing observable has happened yet (unless you’re happy to wait for several decades, and then try and prove attribution).

Example: funding progressive movements that are taking on a repressive government. Can you only assess impact after/if the revolution happens? No, you have to find ways of measuring progress, which are likely to revolve around systematically gathering other people’s opinions of what you have been doing.

Even if the revolution does come, you need to establish whether any of it can be attributed to your contributions – how much of the Arab Spring was down to your little grant or workshop?! Process tracing is interesting here – you not only investigate whether the evidence supports your hypothesis that your intervention contributed, but also consider alternative narratives about other possible causes. You then make a judgement call about the relative plausibility of different versions of events.

Counterfactuals when N=1: Counterfactuals are wonderful things – find a comparable sample where the intervention has not happened, and if your selection is sufficiently rigorous, any difference between the two samples should be down to your intervention. But what about when N=1? We recently had a campaign on Coca Cola which was rapidly followed by the company shifting its policy on land grabs. What’s the counterfactual there – Pepsi?! Far more convincing to talk to Coke management, or industry watchers, and get their opinion on the reasons for the policy change, and our role within it.

All of these often-derided ‘qual’ methods can of course be used rigorously, or sloppily (just like quantitative ones).

Accountability v Learning: What are we doing all this measurement for? In practice M&E (monitoring and evaluation) often take precedence over L (Learning), because the main driver of the whole exercise is accountability to donors and/or political paymasters. That means ‘proving’ that aid works takes precedence over learning how to get better at it. Nowhere is this clearer than in attitudes to failure – a goldmine in terms of learning, but a nightmare in terms of accountability. Or in timelines – if you want to learn, then do your monitoring from the start, so that you can adapt and improve. If you want to convince donors, just wait til the end.

Accountability v Learning: What are we doing all this measurement for? In practice M&E (monitoring and evaluation) often take precedence over L (Learning), because the main driver of the whole exercise is accountability to donors and/or political paymasters. That means ‘proving’ that aid works takes precedence over learning how to get better at it. Nowhere is this clearer than in attitudes to failure – a goldmine in terms of learning, but a nightmare in terms of accountability. Or in timelines – if you want to learn, then do your monitoring from the start, so that you can adapt and improve. If you want to convince donors, just wait til the end.

People also feel that M&E frameworks are rigid and unchangeable once they’ve been agreed with donors, and they are often being reported against by people who were not involved in the original design conversations. That can mean that the measures don’t mean that much to them – they are simply reporting requirements, rather than potentially useful pieces of information. But when you actually talk to flesh and blood donors, they are increasingly willing to adjust indicators in light of the progress of a piece of work – sorry, no excuse for inaction there.

Horses for Courses: Claire has been playing around with the different categories of ‘hard to measure’ benefits that Oxfam is grappling with, and reckons most fall into one (or more) of the following three categories

The issue is complex and therefore hard to understand, define and/or quantify (e.g. women’s empowerment – see diagram, resilience). Here we’re developing ‘complex theoretical constructs’ – mash up indices of several different components that try and capture the concept

The intervention is trying to influence a complex system (and is often itself complex) eg advocacy, or governance reform. For both, we’re investing in real time information to inform short- and medium term analysis and decisions on ‘course corrections’. In terms of final asessments on effectiveness or impact, policy advcocay is where we think process tracing can be most useful. The units are too small to estimate the counterfactual and so it’s about playing detective to try and identify the catalysts and enablers of change, and see if your intervention is among them. We’re still learning how best to approach evaluation of governance programming. Some will lend themselves to more traditional statistical approaches (eg the We Can campaign on Violence Against Women), but others have too few units to be classified as ‘large n’ and too many to be considered truly ‘small n’. We trialled outcome harvesting + process tracing last year in Tanzania.

The intervention is taking place in a complex, shifting system. This might be more traditional WASH programming, or attempting to influence the complex systems of governance work in fragile states. The evaluation designs may be similar to categories one and two above, but the sustainability of any positive changes will be much less certain, and like 2, we are most interested in realtime learning informing adaptation, which requires a less cumbersome, more agile approach.

Got all that? My head hurts. Time for a cup of tea.

December 1, 2013

Is India breaking new ground by requiring corporates to spend 2% of company profits on CSR?

This is a joint post with Avinash Kumar (right),

Oxfam India’s

Policy, Research & Campaigns Director

Corporate responsibility in India is getting interesting – an unheralded aspect of the growth of its business sector. Recent legislation requires public sector enterprises to make social responsibility and stakeholder engagement part of their core business practices, while in July, 2011, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs came out with ‘National Voluntary Guidelines (NVGs) on Social, Environmental and Economic Responsibilities of Business’.

This has moved up another gear with the approval in August of a new Companies Act. The detailed rules are still being formulated, but the new law looks like becoming an important milestone.

The new Act replaces the old and increasingly outdated Companies Act of 1956. Momentum for reform came from a series of spectacular corporate  scams and scandals, including the telecom sector, Satyam, Saradha Chit Fund and the Sahara group.

scams and scandals, including the telecom sector, Satyam, Saradha Chit Fund and the Sahara group.

The Act requires companies to:

Have at least one woman on every board

Set up a Corporate Social Responsibility Committee within the board of directors, including at least one independent director. The Committee must formulate and recommend to the Board a Corporate Social Responsibility Policy, recommend how much to spend on CSR, and specify the sector along with specific activities/projects to be undertaken

Appoint a CSR ‘Nodal Officer’ and implementing teams

Draw up a Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting Framework (CSRRF) to be submitted annually

Monitoring must be undertaken by a different agency to those implementing and report to a board level committee

But what has grabbed the attention of civil society organizations is Clause135, which obliges large companies (net worth of US$80m, turnover of US$160m, or net profit of US$8m) to devote 2% of the average net profit (after tax) to corporate social responsibility. Conservative estimates put the total at roughly US$2.5 billion.

There is a pretty important get-out here – spending the money is on a ‘comply or explain’ basis, but companies that choose to explain why they haven’t spent the money are likely to face some serious criticism from the media and civil society.

How will companies react? They have plenty of leeway: the Act’s definition of CSR includes eradicating extreme hunger and poverty; promoting education; women’s empowerment; reducing child mortality and improving maternal health; combating HIV, AIDS, malaria and other diseases; environmental sustainability; vocational skills; social business projects and contributing to the Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund or any other state fund socioeconomic development.

A nice analysis by Kordant Philanthropy Advisers suggests:

‘There are several behaviors that we expect companies to exhibit following the law’s passage. Some companies will make the structural changes to their board to avoid fines, only to explain in their board report why they are unable to spend on CSR. Others will allocate an additional portion of their budget to meeting the reporting requirements and/or use the board report as an opportunity to showcase their CSR activities. Many companies are likely to re-categorize current quasi-CSR activities so as to fall within the scope of the new law. Whether the CSR Clause actually encourages more CSR spending or not, it will certainly force companies to seriously contemplate social responsibility or risk becoming a conspicuous non-spender among peers who already invest heavily in it. ‘

peers who already invest heavily in it. ‘

Some of the top Management Schools, including the elite Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) have already responded by initiating CSR management courses on a par with their other management programmes. Clearly, the direction is towards making social responsibility an additional arm of the Corporate brand.

How is civil society reacting? Will this be the answer to the funding shortfall as aid donors leave India, and civil society and NGOs look for new sources or revenue? While there is a predictable buzz around the Act, the detail of its implementation is still unclear. But there are already indications of what to expect:

The Act lists a wide range of players who could be eligible for grants, including community-based organizations (formal or informal), NGOs, civil society organizations, institutes/ academic organizations, civil works contractors and professional Consultants. This means much sharper competition for resources.

Many corporates are setting up their own Trusts and Foundations which can then determine the extent and nature of their respective CSR portfolio. Many of the smaller Foundations are beginning to do the work themselves instead of giving sub-grants to NGOs or other partners.

However, some big companies do not want to hand over their cash in small fragments to a range of organizations and may prefer to give money in large chunks to organised, professional NGOs or other agencies who can provide ‘the value of their money’, (that will also mean a greater ‘professionalisation’ in terms of showing results, indicators of success etc).

Will corporates divert the cash or bypass the rules? Will they attach unacceptable strings and/or compromise the independence of Indian civil society? Will a new generation of NGOs spring up to spend their cash without any commitment to social change, so dragging Indian civil society to the right and away from the rights agenda and structural change (as aid for service delivery arguably does with INGOs)?

Another danger is that the definition of corporate responsibility becomes so broad as to lose all meaning. Already there is a talk of using the CSR 2% for infrastructure development or even funding the government’s existing social sector commitments such as the Food Security Act.

There are fears of greenwash. After all, companies like Satyam (the most celebrated self-confessed Scamster in recent years in India), as well as international corporate like Shell and BP, which stand accused of gross environmental misconduct, have still managed to win top notch CSR awards. CSR must not be seen as a separate dangling arm of Corporate Affairs, but as an integrated part of the entire business cycle.

This all poses real dilemmas for NGOs like Oxfam India. The fast depleting resources of external donor-financed, rights-based work mean that they are at a cross-roads today. The question for them is whether to compete with the new Foundations being set up under CSR to fill the vacuum of service-delivery in the wake of the government withdrawal and its replacement by PPP models, or face extinction as clearly rights-based social movements. In the end CSR in its present format is likely to re-affirm the present model of growth led development and those trying to question it may find themselves relegated to the sidelines.

This all poses real dilemmas for NGOs like Oxfam India. The fast depleting resources of external donor-financed, rights-based work mean that they are at a cross-roads today. The question for them is whether to compete with the new Foundations being set up under CSR to fill the vacuum of service-delivery in the wake of the government withdrawal and its replacement by PPP models, or face extinction as clearly rights-based social movements. In the end CSR in its present format is likely to re-affirm the present model of growth led development and those trying to question it may find themselves relegated to the sidelines.

But on the other hand, the new Act may provide a real opportunity to open up formal spaces for dialogue with the corporates, which have been non-existent so far. Earlier, corporates only talked to the government and with their huge money muscle they had a great advantage over CSOs who could only shout from outside the board rooms. This may be, (just maybe) an entry point where the NGO sector can find an equitable place for dialogue.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers