Duncan Green's Blog, page 197

February 4, 2014

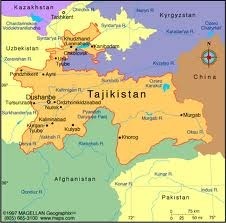

My first trip to Central Asia. First impressions of Tajikistan, world’s most remittance-dependent country (and a very big flagpole)

Spent last week in Tajikistan, my first trip to the former underbelly of the Soviet Union, aka Central Asia. I was there to help our  country team think through some work on improving accountability in the water sector (more interesting than it sounds – blog tomorrow). And weatherwise, looks like I got out just in time. But today is first impressions.

country team think through some work on improving accountability in the water sector (more interesting than it sounds – blog tomorrow). And weatherwise, looks like I got out just in time. But today is first impressions.

Basic background: poorest country in Central Asia, average per cap income around $780 (2010). Eight million people, with about a million of them working in Russia for most of the year (see below). Independence in 1990s swiftly followed by bloody civil war, in which 50-100,000 people died, leading to victory of current president, Emomali Rahmon, whose beetle-browed, half smiling image adorns large numbers of public buildings in Dushanbe.

This is pretty restrained by Central Asian standards: ‘Niyazov (dictator of Turkmenistan for 16 years after fall of Soviet Union) outlawed ballet and opera, replaced the word ‘bread’ with his mother’s name, swapped January with his own name and built golden statues of himself, one of which rotated to continually face the sun.’ (from Understanding Central Asia.)

Skimming the websites on my return, I’m struck by the gulf between how people (villagers, NGOs, aid workers) talked to me last week, and the upbeat tone of things like the World Bank ‘snapshot’. High growth, steady progress and ‘extreme poverty rates, based on the food poverty line, declined from 73 percent in 1999 to 14 percent in 2009.’

Tajikistan has at least two global claims to fame: the tallest flagpole in the world (a gift to Freudians everywhere). And the world’s highest level of dependency on remittances from migrant workers, mainly from men going to Russia (a mind-boggling 47% of GDP in 2012, according to the World Bank’s excellent briefing). On Tuesday, the government reported a further 12% increase in remittances for 2013, bringing them to $4.2bn/49% of GDP.

Tajikistan has at least two global claims to fame: the tallest flagpole in the world (a gift to Freudians everywhere). And the world’s highest level of dependency on remittances from migrant workers, mainly from men going to Russia (a mind-boggling 47% of GDP in 2012, according to the World Bank’s excellent briefing). On Tuesday, the government reported a further 12% increase in remittances for 2013, bringing them to $4.2bn/49% of GDP.

Oddly, the villages we visited down South were full of men, hanging around. They were back from Russia for a couple of months, presumably because the Russian winter stops construction work. The rest of the year the villages are almost entirely made up of women, kids and ‘old people’ (over 45, ouch). The fruits of their labour are evident in nice new homes springing up at intervals in the villages.

According to the villagers, migration’s impact is mixed: ‘You hear good and bad stories all the time. Some men forget their families, women are abandoned. But others come back with money, build houses, send money – it’s good. You learn Russian, new skills.’

‘You are treated badly by the Russians, even by Tajiks who are doing well. You live with a lot of people all in one room. You don’t speak Russian so you don’t understand orders and make mistakes. I wasn’t paid for 2 months, then gave up and came home.’

What was most striking, at least for me, is that the NGOs and aid donors I talked to were hardly working on migration as a development issue. So half the economy is somehow not of interest? Some research issues that emerged:

Organization of migrants in Russia. Do migrants organize in any way – networks of people from the same village? Social media?

Transmission and management of remittances. How much of the few hundred dollars a typical migrant sends home every month flows through formal money transfer operators? What other channels are used?

Who decides how the money is spent – the men in Russia? The women back home? Other?

Answering these sorts of questions would be a first step to thinking how that huge flow of cash should/could be harnessed better for  social investment and poverty reduction. Eg what about donors offering to match remittances flowing into water investment, along the lines of Mexico’s 3×1 programme? If men are taking the decisions, why not get them together in December/January, when they are back in their villages with time on their hands, and discuss how best to use remittances to improve life back home?

social investment and poverty reduction. Eg what about donors offering to match remittances flowing into water investment, along the lines of Mexico’s 3×1 programme? If men are taking the decisions, why not get them together in December/January, when they are back in their villages with time on their hands, and discuss how best to use remittances to improve life back home?

I’m not a migration buff, but I’m sure there are dozens of other possibilities from work in other countries – v odd that more of it is not happening in Tajikistan, at least as far as my brief trip suggested (although I did subsequently stumble across this small EU-funded project to promote migrant rights). Anyone got links to good experiences of NGOs working to improve the social impact of migration, either in Tajikistan or anywhere else?

Tomorrow, back to Tajikistan’s water sector, which gives a pretty perfect insight into its institutions, history etc etc, as well as some truly dire toilets.

Update: Interested in examples of INGO work (including Oxfam!) supporting communities who rely on seasonal migration and the remittances that come from that.

My first trip to Central Asia. First impressions of Tajikistan, worldâs most remittance-dependent country (and a very big flagpole)

Spent last week in Tajikistan, my first trip to the former underbelly of the Soviet Union, aka Central Asia. I was there to help our  country team think through some work on improving accountability in the water sector (more interesting than it sounds â blog tomorrow). And weatherwise, looks like I got out just in time. But today is first impressions.

country team think through some work on improving accountability in the water sector (more interesting than it sounds â blog tomorrow). And weatherwise, looks like I got out just in time. But today is first impressions.

Basic background: poorest country in Central Asia, average per cap income around $780 (2010). Eight million people, with about a million of them working in Russia for most of the year (see below). Independence in 1990s swiftly followed by bloody civil war, in which 50-100,000 people died, leading to victory of current president, Emomali Rahmon, whose beetle-browed, half smiling image adorns large numbers of public buildings in Dushanbe.

This is pretty restrained by Central Asian standards: âNiyazov (dictator of Turkmenistan for 16 years after fall of Soviet Union) outlawed ballet and opera, replaced the word ‘bread’ with his mother’s name, swapped January with his own name and built golden statues of himself, one of which rotated to continually face the sun.’ (from Understanding Central Asia.)

Skimming the websites on my return, Iâm struck by the gulf between how people (villagers, NGOs, aid workers) talked to me last week, and the upbeat tone of things like the World Bank âsnapshotâ. High growth, steady progress and âextreme poverty rates, based on the food poverty line, declined from 73 percent in 1999 to 14 percent in 2009.â

Tajikistan has at least two global claims to fame: the tallest flagpole in the world (a gift to Freudians everywhere). And the worldâs highest level of dependency on remittances from migrant workers, mainly from men going to Russia (a mind-boggling 47% of GDP in 2012, according to the World Bankâs excellent briefing). On Tuesday, the government reported a further 12% increase in remittances for 2013, bringing them to $4.2bn/49% of GDP.

Tajikistan has at least two global claims to fame: the tallest flagpole in the world (a gift to Freudians everywhere). And the worldâs highest level of dependency on remittances from migrant workers, mainly from men going to Russia (a mind-boggling 47% of GDP in 2012, according to the World Bankâs excellent briefing). On Tuesday, the government reported a further 12% increase in remittances for 2013, bringing them to $4.2bn/49% of GDP.

Oddly, the villages we visited down South were full of men, hanging around. They were back from Russia for a couple of months, presumably because the Russian winter stops construction work. The rest of the year the villages are almost entirely made up of women, kids and âold peopleâ (over 45, ouch). The fruits of their labour are evident in nice new homes springing up at intervals in the villages.

According to the villagers, migrationâs impact is mixed: âYou hear good and bad stories all the time. Some men forget their families, women are abandoned. But others come back with money, build houses, send money â itâs good. You learn Russian, new skills.â

âYou are treated badly by the Russians, even by Tajiks who are doing well. You live with a lot of people all in one room. You donât speak Russian so you donât understand orders and make mistakes. I wasnât paid for 2 months, then gave up and came home.â

What was most striking, at least for me, is that the NGOs and aid donors I talked to were hardly working on migration as a development issue. So half the economy is somehow not of interest? Some research issues that emerged:

Organization of migrants in Russia. Do migrants organize in any way â networks of people from the same village? Social media?

Transmission and management of remittances. How much of the few hundred dollars a typical migrant sends home every month flows through formal money transfer operators? What other channels are used?

Who decides how the money is spent â the men in Russia? The women back home? Other?

Answering these sorts of questions would be a first step to thinking how that huge flow of cash should/could be harnessed better for  social investment and poverty reduction. Eg what about donors offering to match remittances flowing into water investment, along the lines of Mexicoâs 3×1 programme? If men are taking the decisions, why not get them together in December/January, when they are back in their villages with time on their hands, and discuss how best to use remittances to improve life back home?

social investment and poverty reduction. Eg what about donors offering to match remittances flowing into water investment, along the lines of Mexicoâs 3×1 programme? If men are taking the decisions, why not get them together in December/January, when they are back in their villages with time on their hands, and discuss how best to use remittances to improve life back home?

Iâm not a migration buff, but Iâm sure there are dozens of other possibilities from work in other countries â v odd that more of it is not happening in Tajikistan, at least as far as my brief trip suggested (although I did subsequently stumble across this small EU-funded project to promote migrant rights). Anyone got links to good experiences of NGOs working to improve the social impact of migration, either in Tajikistan or anywhere else?

Tomorrow, back to Tajikistanâs water sector, which gives a pretty perfect insight into its institutions, history etc etc, as well as some truly dire toilets.

February 3, 2014

Voices of the Hungry; killer indicators, and how to measure the social determinants of health. New thinking on measurement with Gallup Inc.

About once a year, I head off for the plush, Thames-side offices of Gallup Inc, for a fascinating update on what theyâre up to on  development-related topics. In terms of measurement, they often seem way ahead of the aid people, for example, developing a rigorous annual measurement of well-being across 147 countries. Not quite sure why they talk to me â maybe as part of the wilder shores of their business development â they know they wonât get much business out of it, but some useful ideas might come out of the discussion. This time, Katherine Trebeck, Oxfamâs wellbeing guru (only she prefers to call it ‘collective prosperity’ for some reason) and developer of the Humankind Index, was there too, which added some actual knowledge to our side of the exchange.

development-related topics. In terms of measurement, they often seem way ahead of the aid people, for example, developing a rigorous annual measurement of well-being across 147 countries. Not quite sure why they talk to me â maybe as part of the wilder shores of their business development â they know they wonât get much business out of it, but some useful ideas might come out of the discussion. This time, Katherine Trebeck, Oxfamâs wellbeing guru (only she prefers to call it ‘collective prosperity’ for some reason) and developer of the Humankind Index, was there too, which added some actual knowledge to our side of the exchange.

First up was Gallupâs partnership with the FAO on their âVoices of the Hungryâ project, aimed in part at correcting the alarming weakness of the numbers on hunger (see Richard Kingâs 2011 post on that). After pilots in Angola, Ethiopia, Malawi and Niger, in part supported by the Government of Belgium, FAO has now got DFID funding to go global, initially for two years. Through âVoices of the Hungryâ, FAO has developed the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), modelled on the 15-item Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale. This uses interviews to place people along a spectrum from worried about food to seriously hungry.

When it goes global, the FIES will be included in the Gallup World Poll, which means the FAO will be able to obtain national measures of food insecurity in all countries covered by the GWP, Â but, very importantly, also to compare the prevalence of food insecurity with issues such as jobs, corruption and migration. As the poll is with individuals rather than households, it will also allow an exploration of gender differences in food security. Down the line, Gallup is wondering if something similar could work on water and sanitation, which are also dogged by dodgy stats. Watch this space.

When it goes global, the FIES will be included in the Gallup World Poll, which means the FAO will be able to obtain national measures of food insecurity in all countries covered by the GWP, Â but, very importantly, also to compare the prevalence of food insecurity with issues such as jobs, corruption and migration. As the poll is with individuals rather than households, it will also allow an exploration of gender differences in food security. Down the line, Gallup is wondering if something similar could work on water and sanitation, which are also dogged by dodgy stats. Watch this space.

Next, some intriguing thinking from Katherine. The world is now awash with alternative indicators, many trying to go âbeyond GDPâ, add to thinking about sustainability and measure wellbeing, progress, aspects of poverty and so on. Most sink without trace with policy makers, and barely register with the public. new economics foundation (with its annoying, Martin Lukes-style lower case) is trying to understand which indicators get traction with policy makers through the Bringing Alternative Indicators into Policy, or BRAINPOoL project (what is it with these guys and upper/lower case?), which is presenting its final conclusions at a conference in Paris in March.

Katherine is thinking more about the public communication angle. She wants to identify âtotemicâ, ‘gateway’ or âkillerâ indicators that resonate with what people say is important to them, on their terms and in their language, but which when unpacked, contain relevant information for policy makers (hence ‘gateway). Things like âhow many kids go to school by bicycle?â, âdo you know your neighbours?â, or âdo you feel safe walking your street at night?â. Andrew Rzepa, the Gallup nerd in the room, labelled them âsexy compound indicatorsâ.

A few questions emerged in the ensuing discussion:

-Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Do they have to be comparable across countries (canât see too many Delhi parents wanting their kids to go anywhere by bike â Iâve tried it, and itâs scary)? Or is the main issue the time series within each country, to help governments better understand what matters to their people?

-Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Do we want to first develop new SCIs (sexy compound indicators, please keep up) or test the dozens of existing indicators, whether mainstream or whacky, and see which ones resonate with different sections of the public?

-Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Is the search restricted to identifying killer indicators that communicate what we think is important (health, education, decent work, wellbeing)? Or are we willing to engage with a more complex range of topics that is genuinely bottom up but may not have any obvious policy implications (how my favourite soccer team is doing, how much time I get to spend partying, watching TV or shoe shopping, can I go to Church/mosque as regularly as I would like)?

Finally, Gallup is keen to work with Michael Marmot to develop metrics for measuring the social determinants of health. If you accept the argument that much of the variation in health outcomes is determined not by access to health care and medicines, but by things like poverty, stressful working conditions, poor housing and unequal access to education, then a widely accepted measure of that enabling environment could really help galvanise policy makers to take it seriously. They are currently looking for some seed funding to get this work started, so if youâre interested, get in touch.

Finally, Gallup is keen to work with Michael Marmot to develop metrics for measuring the social determinants of health. If you accept the argument that much of the variation in health outcomes is determined not by access to health care and medicines, but by things like poverty, stressful working conditions, poor housing and unequal access to education, then a widely accepted measure of that enabling environment could really help galvanise policy makers to take it seriously. They are currently looking for some seed funding to get this work started, so if youâre interested, get in touch.

This may all seem rather arcane/nerdy, but Iâm increasingly convinced that the measurement agenda (if you canât measure it, it probably doesnât exist, wonât get funded and is unlikely to get much attention from policy makers) is here to stay. So we really need to make sure we count what counts, not just what is easily counted. Gallup looks likely to be a significant player in that effort.

February 2, 2014

How can aid workers study without giving up the day job? Your thoughts please.

For a sector that employs a relatively large number of people, the âaid businessâ often still seems to think small. Getting a job in it is a lottery – very few graduate entry schemes, or other ways to identify and recruit keen and talented people. Instead people are supposed to scrabble their way into jobs by somehow gaining âexperienceâ, when jobs nearly always require you to have experience already. Nightmare. See here for some other thoughts on getting a job and here’s a big list of job websites.

Then suppose youâve got a job, and you want to improve your understanding of development issues through study, either for personal reasons, or as part of improving your job prospects. Tough. The sector  seems to give priority to activism over reflection. New arrivals at Oxfam go on a KOO (knowledge of Oxfam) course, but thereâs no accompanying KOD (Knowledge of Development). Across the sector, there is very little focus on learning or study, in contrast to say, the medical profession with its requirements to stay up to date on new developments, clinical doctorates etc.

seems to give priority to activism over reflection. New arrivals at Oxfam go on a KOO (knowledge of Oxfam) course, but thereâs no accompanying KOD (Knowledge of Development). Across the sector, there is very little focus on learning or study, in contrast to say, the medical profession with its requirements to stay up to date on new developments, clinical doctorates etc.

Instead, if they want to study, people often assume they have to go back to college. But many canât do that â they have kids, responsibilities etc so canât drop everything and go back to being a full-time student. What options are there for distance learning that enables them to brain up while still paying the bills? I get asked this a fair amount by keen types I come across in Oxfam and beyond, and struggle to answer.

Also, if you want to reflect on your work, link theory and aid/development practice etc, rather than just pursue a purely academic course, where should you go?

I need your suggestions here.

The best course that I know of that ticks both boxes is still the Open University Masters in Development Management. Everyone I know who has done it raves about it, and Iâve used the materials myself in the past. The blurb for the course reads:

âThis MSc is for anyone with a professional and/or personal interest in development and a desire to bring about good change. It addresses the needs both of those who would label themselves development managers, and those, such as engineers, health workers, educationists, agriculturalists, bankers, scientists, who need the capacity to manage development if they are to do their work  effectively. It engages with development at all levels, from the local to the global, and is as relevant in rural as in urban contexts. It addresses development in diverse fields, including health and well-being, livelihoods, education, the environment, war and resettlement, infrastructure, with the issues of poverty and inequality running through all. It takes theory seriously; consciously and constantly linking it to practice and policy, looking to enhance the competence of individuals and the capacity of agencies to undertake development successfully.

effectively. It engages with development at all levels, from the local to the global, and is as relevant in rural as in urban contexts. It addresses development in diverse fields, including health and well-being, livelihoods, education, the environment, war and resettlement, infrastructure, with the issues of poverty and inequality running through all. It takes theory seriously; consciously and constantly linking it to practice and policy, looking to enhance the competence of individuals and the capacity of agencies to undertake development successfully.

It is designed for anyone in government, non-governmental organisations, international and inter-governmental agencies and public  and private enterprises, who have responsibility for development interventions, programmes and policies. It is also of value for anyone wishing to move into such areas, or who for personal and/or professional reasons wants to build up a better understanding of the complex processes labelled âdevelopmentâ, with a view to managing those processes better.â

and private enterprises, who have responsibility for development interventions, programmes and policies. It is also of value for anyone wishing to move into such areas, or who for personal and/or professional reasons wants to build up a better understanding of the complex processes labelled âdevelopmentâ, with a view to managing those processes better.â

But that course has been running for decades. In this world of MOOCs and online everything, Iâm assuming there are other courses geared to the needs of mid career aid people who want to dig deeper. Please tell me about them.

January 30, 2014

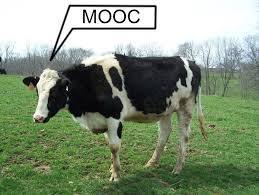

Anatomy of a killer fact: the worldâs 85 richest people own as much as the poorest 3.5 billion

Ricardo Fuentes (@rivefuentes) reflects on a killer fact (85 individuals own as much wealth as half the worldâs population) that made  a big splash last week, and I add a few thoughts at the end.

a big splash last week, and I add a few thoughts at the end.

Last week we released a report on the relationship between the growing concentration of income and biases in political decision making. âWorking for the  Fewâ got a lot of attention, generating the biggest-ever traffic day on the Oxfam International website the day of the launch.

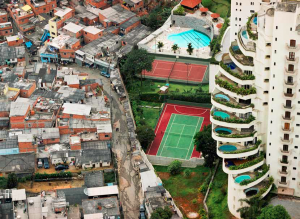

A large part of the attention was generated by one fact: the 85 richest people own as much as the bottom half of the world.

We had direct reference to Oxfamâs â85â on The Now Show on BBC radio 4 and in The Onion with a pull-quote: âImagine if the wealthiest donated just one dollar a day to charity. That could work out to around 85 bucks a day.â

There’s the have nots. And then there’s the have yachts.

Others pieces with large readership that featured our number include the World Bank president Jim Kimâs personal blog, The Atlantic magazine, Slate news website, Salon news website, Washington Postâs Ezra Klein, National Public Radio and The New Yorker.

How did we come to this figure? Itâs a simple calculation. And yet it required a lot of work.

First, we didnât design the statistic to shock, as some commentators have argued. Whatâs shocking is the concentration of wealth around the world – thatâs a fact. Instead, we studied a series of available databases on income and wealth and analysed the trends. That fact captured the attention but we did plenty more data work with alternative sources. All of them pointed to the same results: since 1980 or so, concentration of income and wealth has been increasing and is now at remarkably high levels.

One of the databases we worked with is the 2013 Global Wealth Report and Databook, compiled by James Davies, Rodrigo Lluberas and Anthony Shorrocks for Credit Suisse. They all are respected economists. Shorrocks is probably the best known. He was the director of the United Nationâs World Institute for Development Economics Research (better known as UNU-WIDER) and has a long list of publications on poverty and inequality.

Davis, Lluberas and Shorrocks have been calculating global personal wealth for four years now and the estimates are as credible as one can get on global wealth by country and around the world. I spent several weeks studying the methodology and understanding their assumptions. I also asked the opinion of Branko Milanovic and James Foster, respected scholars in the field, about the quality of the database. I was confident we could use it for the analysis we presented in âWorking For The Fewâ. So we did.

The summary statistics of the Global Wealth Report are eye-popping. We reproduced some of them in the paper: The richest 1% own 46% of the worldâs wealth. The richest 10% own 86% of wealth. The poorest 10% live in debt.

Once Nick Galasso and I had mostly finished the paper last December, I decided to go back to the Credit Suisse report and look for more  facts that could add punch to our argument. There was one sentence that caught my eye: the bottom half of the population own less than 1% of global wealth. The report didnât have the exact figure, so I had to dig into the statistical annex and the long list of PDF tables (to the best of my knowledge, there is no datafile available to the public) until I found the share of wealth by decile on page 106 of the Databook. Adding the bottom five deciles gave me a figure of 0.71 %. Yes. Unbelievable. Half the world own only 0.71 % of global wealth, totaling 1.7 trillion dollars (just multiply that 0.71% by 241 trillion dollars reported as total global wealth by Credit Suisse).

facts that could add punch to our argument. There was one sentence that caught my eye: the bottom half of the population own less than 1% of global wealth. The report didnât have the exact figure, so I had to dig into the statistical annex and the long list of PDF tables (to the best of my knowledge, there is no datafile available to the public) until I found the share of wealth by decile on page 106 of the Databook. Adding the bottom five deciles gave me a figure of 0.71 %. Yes. Unbelievable. Half the world own only 0.71 % of global wealth, totaling 1.7 trillion dollars (just multiply that 0.71% by 241 trillion dollars reported as total global wealth by Credit Suisse).

The next step was to go to the Forbes list of billionaires (which is, fittingly, sorted in descending order) and add up the richest individualâs wealth. By the time I got to number 85 among in the league table of wealthiest people I had reached 1.7 trillion dollars, the same amount as the total wealth of the bottom half.

For the billionaires list, I chose Forbes over Bloomberg because the Credit Suisse work actually uses the Forbes list to adjust their methodology since the richest people in the world are unlikely to be captured in the distribution of global wealth without that adjustment. This means that the two databases (Forbes and Credit Suisse) are consistent.

What assumptions did I make? I took Credit Suisseâs work at face value, so I implicitly accepted their assumptions. Then I made some additional ones. The sample for the Credit Suisse Report is worldâs adults – it doesnât include youth or children. We could then either say we are only talking about the worldâs adults or assume that children do not possess any individual wealth and there are the same number of children in each wealth decile – clearly, a conservative approach as fertility rates are higher in poorer households. Our number might actually underestimate the extent of wealth inequality.

This killer fact – 85 people owns as much as half of the world – has created a massive interest in our work but the analysis we produced in the paper goes well beyond it. We used four different databases (all cited in the paper) in our work. We studied the problem at length,  and during that process we identified some eye-opening trends. We did not intend to shock. The facts themselves are quite shocking enough. There is no need to make up injustices when there are so many real-life ones.

and during that process we identified some eye-opening trends. We did not intend to shock. The facts themselves are quite shocking enough. There is no need to make up injustices when there are so many real-life ones.

And a few thoughts from me

What struck me as the media storm engulfed Ricardo is the importance of timing. A great killer fact will get media attention, but this one came not just in time for Davos, but when the global head of steam on inequality was already building â Ricardoâs paper (with Nick Galasso) has certainly added to that momentum. For Davos last year, we produced a similar fact (the 100 richest individuals in the world earned enough to end world poverty four times over). It got good coverage (you can see a spike in the website hits) , but nothing like this time. The report backing it up had a greater investment in research this time (although last yearâs stat was based on work by Bloomberg and the Brookings Institution, so it was hardly back of an envelope). But maybe the zeitgeist just wasnât ready for it last year.

January 29, 2014

Can aid donors really âthink and work politicallyâ? Plus the dangers of âbig manâ thinking, and the horrors of political science-speak

Spent an enjoyable  couple of days last week with the âthinking and working politicallyâ (TWP) crew, first at a follow up to the Delhi

Adrian Leftwich 1940-2013

meeting (nothing earth shattering to report, but a research agenda is on the way â Iâll keep you posted), and then at a very moving memorial conference for the late Adrian Leftwich (right), who is something of a founding father to this current of thought.

Regular readers of this blog will know that I’m a big fan of this line of thinking: understanding and engaging with the underlying issues of power and politics should be the heart of any serious work on development.

But based on last weeks exchanges, I’ve got some concerns too – here are some reflections:

First some choice quotes:

âGovernance people are in retreat at the moment. Itâs quite shocking â the transformation agenda has been scrapped in favour of âletâs buy some resultsâ

âThe one thing we learn from history is that we never learn from historyâ. Best not to think about that too hard.

As in Delhi, one very clear message was the very real institutional constraints on how far aid agencies, especially official ones (governments and multilaterals) can go on this agenda. TWP means taking risks, jumping at opportunities, finding and backing maverick âdevelopment entrepreneursâ and accepting failure as the price of occasional success. Is that an institutional possibility for large agencies? Compare with this rather jaundiced (and Chatham House) description of how an aid donor works:

“There are three power centres in any aid organization: policy, risk control, spending. At the policy level, the underlying assumption is that country teams will not do the right thing unless you make it mandatory, so the role is to lobby for my bit in programme implementation. As a result, the organization builds up a labyrinth of mandatory controls, frameworks, strategies etc.

The risk and control power centre focuses on eliminating corruption; they feel that spending teams cannot be trusted to follow value for money, or do sufficient due diligence in avoiding corruption, when they also have to avoid any underspend (the ultimate crime). So the risk and control people add more controls and mandatory guidelines.

So where does that leave people trying to spend the money (and achieve change) at a country level? They generally react to the ever-proliferating controls in two ways â they either become completely immobilised and push every decision up to their bosses, or they work under the radar and hide a lot of what they actually do.”

We need to understand much better how donors actually function (or fail to) if we are to convince them to adopt the TWP approach, and at least some of the researchers present are planning to do a full political economy analysis of a donor â that will be interesting (if it’s ever published).

The conference was organized by the Developmental Leadership Program, a research initiative founded by Leftwich to explore a much neglected topic,  âthe critical role played by leaders, elites and coalitions in the politics of development’. Itâs doing some great work, some of it reviewed on this blog, including some fantastic case studies on the origins of leaders in countries such as Somaliland and Ghana (more on that to follow).

But Iâm torn over this increasing recognition of the importance of individuals in driving change. Thereâs no doubt (as Iâm currently finding in my conversations in Tajikistan â more of that next week) that âdevelopment entrepreneursâ who can think, act, seize opportunities, sell ideas and inspire (all at the same time) are not exactly growing on trees, and we need to understand how they emerge, and have impact.

But are we also falling into the trap of some kind of micro Big Man syndrome? â as Lant Pritchett so eloquently explains, we all prefer to think in terms of agents, rather than complex systems. How change happens is really complex, so letâs give our aching brains a rest and say itâs all about leaders. Think Paul Kagame and the tendency for politicians to see the world in terms of âdecent chapsâ. That sounds awfully like those British technocrats who admired Mussolini for making the trains run on time. To be fair, the DLP has a much more nuanced understanding of the word leadership, as this paper explains, but the issue still nags away.

Linked to this, there is a worrying tendency among the TWP crowd to take a perverse pleasure in jettisoning the accumulated âbest practiceâ of the development business, claiming it is both counter-productive (inhibits innovation and stops the emergence of hybrid institutions that function and last, even if they are second best from, say, a rights perspective) and an irritating outbreak of political correctness.

But however irritating the more unthinking outbreaks of tokenism and political correctness may be, the underlying ideas are substantial and important. Things like accountability, inclusion, gender rights, and participation are not political correctness, they are the stuff of development (Senâs âfreedoms to be and to doâ). It may well be that we have to depart from them at times to achieve specific ends (e.g. if youâre negotiating a difficult peace settlement in Northern Ireland, publishing the minutes of every meeting is probably not going to help). But that departure should be temporary, for a clear purpose, and should eventually return us to a better place from which to recommence the struggle for all those good things like rights and transparency.

And finally, thereâs the jargon problem, which seems particularly acute with this epistemic community. Oops, now Iâm doing it. How

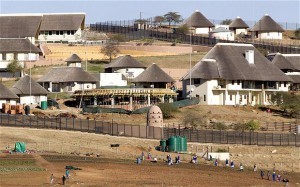

Jacob Zuma’s new house, or a political settlement?

would normal people translate these over-used phrases (my suggestions in brackets)

political settlements (= villages with lots of politicians living in them, or maybe just one – see right)

developmental regimes (= my perfect abs routine at the gym)

emergent change (= butterflies hatching in the spring, awww)

We really have to find better ways to communicate our ideas if we are to convince the non-wonk world.

January 28, 2014

The end of North-South, in one graph

Two important findings from the latest Branko Milanovic (with Christoph Lakner) World Bank paper on global income distribution.

First , it had previously been thought that, due to the rise of China, the global Gini was falling – i.e. if you took the global population as a whole, inequality was falling. Turns out this may not be true due to under-reporting of top incomes (can’t think why that happens). ‘With such an adjustment the downward trend in the Gini almost disappears’. Oops.

Second the paper gives a lovely graphic demonstration of ‘the end of North South’. In 1988 the global distribution was twin peaked – the peaks corresponding broadly to a rich North and poor South. Since then growth in emerging economies, and stagnation for all but the richest in the rich world, has obliterated the valley between the peaks (see graph).

“The “winners” were country-deciles that in 1988 were around the median of the global income distribution, 90 percent of whom in terms of population are from Asia. The “losers” were the country-deciles that in 1988 were around the 85th percentile of the global income distribution, almost 90 percent of whom in terms of population are from mature economies.”

One other titbit:

“Most of global inequality is accounted for by differences between countries, although this contribution has declined over time, suggesting that countries have become more similar. The within-country component of global inequality, however, has increased continuously over this twenty-year period.”

So there you have it, just as the North-South divide starts to fade, the divides within countries kick in to maintain the overall level of global economic unfairness.

January 27, 2014

What happens if you combine life expectancy and GDP into a single indicator? (You spend more on health)

Just been skimming the overview of last December’s report of the Lancet Global health 2035 Commission, chaired by Larry Summers. The report advocates increasing health spending to close the health gap between countries, but the thing that jumped out at me was the practical application of ‘beyond GDP’ thinking in what the report calls the ‘full income approach’:

“But while GDP captures the benefits that result from improved economic productivity (the so-called instrumental value of better health), it fails to capture the intrinsic value of better health—the value of health in and of itself. Global Health 2035 reports a more comprehensive understanding of the returns to investing in health by estimating this intrinsic value using a “full income” approach. This approach combines growth in national income (GDP) with the value people place on increased life expectancy—that is, the value of their additional life years [VLYs]. Global Health 2035 estimates that 24% of the growth in full income in low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2011 resulted from health improvements. Figure 3 summarizes estimates of the contribution of health to growth in full income in 1990–2000 and in 2000–2011 for different regions of the world.

Using the full income approach to estimate the economic benefits of convergence in low-income and lower-middle-income countries from 2015-2035, the benefits exceed costs by a factor of 9-20, making the case for action even stronger.

Using the full income approach to estimate the economic benefits of convergence in low-income and lower-middle-income countries from 2015-2035, the benefits exceed costs by a factor of 9-20, making the case for action even stronger.

The full income approach provides finance ministries, donors and other decision-makers with a strong rationale for investing in health to put their countries on a path to rapid improvement in national welfare.”

January 26, 2014

Carnage on the roads v good news on malaria and guinea worm disease (and a brewing Opium War on Tobacco)

This week’s Economist resembles a reader on some of development’s top Cinderella issues (which are becoming a bit of a thing on this blog), covering road traffic, ‘tropical diseases’ and tobacco.

First up, the contrast between the falls in road deaths in rich countries (deaths there peaked in the 1970s), and rising carnage in the  developing world. New WHO stats provide a graphic account – at 1.3 million a year, deaths from RTAs (road traffic accidents) in poor and middle income countries have overtaken TB and malaria and will match those from HIV/AIDs by 2030. (see graph)

developing world. New WHO stats provide a graphic account – at 1.3 million a year, deaths from RTAs (road traffic accidents) in poor and middle income countries have overtaken TB and malaria and will match those from HIV/AIDs by 2030. (see graph)

From the accompanying editorial,

‘The vast majority of victims die in poor and middle-income countries—1.2m in 2011, compared with 99,000 in rich ones. For every 100,000 cars in the rich world, fewer than 15 people die each year. In Ethiopia the figure is 250 times higher.

The cost of averting a death or injury using speed bumps at deadly junctions in sub-Saharan Africa is a piffling $7; fences between cars and pedestrians in Bangladesh, $135. Yet few places tackle road deaths with the same determination as infectious diseases, and charitable donations are a tiny fraction of the $4 billion promised annually to fight HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.’

And from the main piece:

‘Where incomes are low, for example in Bangladesh and Kenya, pedestrians top the body count. As they rise, so does the use of motorbikes—often for the precarious transport of entire families. In Thailand motorcyclists are more than two-thirds of fatalities. A bit richer still, and four wheels dominate. In Argentina, Russia and Turkey the main victims are inside cars, buses and lorries.

In the Nesco school in Kibera, Kenya’s largest slum, the children recently received government-funded vaccinations for measles and polio. And aid donors have pledged $600m to fight HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria in the country in the next few years, and $4 billion globally. But with multi-lane highways to navigate on the way to school, and a lack of safe crossings, a quarter of the pupils have been in a road crash and a third have seen a close relative injured or killed. A little more spent on road safety would help more children in Kibera, and across the developing world, make it safely into adulthood.’

Global Fund for Speed Bumps, Seat Belts and Sidewalks anyone?

In contrast, some encouraging news on malaria and Guinea Worm Disease (dracunculiasis). On malaria, Chinese researchers led by Li Guoqiao, of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine,

‘turned a Chinese herbal treatment for the disease into artemisinin, one of the most effective antimalarial drugs yet invented. Now he is supervising experiments in the Comoros, using a combination drug therapy based on artemisinin, to see if malaria can be eradicated from that island country. If it works, he hopes to move on to somewhere on the African mainland, and attempt to repeat the process there.’

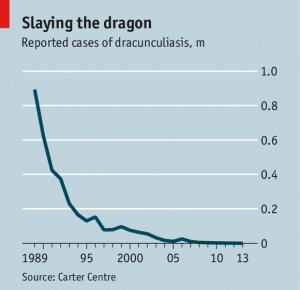

Guinea Worm Disease is a debilitating, if rarely fatal, disease that 25 years ago affected about a million people. A campaign, led by the Carter Center, has got that down to just 148 known cases, mostly in South Sudan (see graph).

Guinea Worm Disease is a debilitating, if rarely fatal, disease that 25 years ago affected about a million people. A campaign, led by the Carter Center, has got that down to just 148 known cases, mostly in South Sudan (see graph).

And a bit more good news from China, on tobacco, which kills about 5.5 million people in developing countries every year (4 times the toll from RTAs):

‘This month health officials in China, home to more smokers than any other country, called for a ban on smoking in public places. That would mainly affect state-owned China Tobacco, which has a near-monopoly. But multinationals’ shares wobbled anyway: the proposed crackdown could portend tighter regulation elsewhere.’

In a 21st Century remake of the Opium Wars, the battle between Big Tobacco and developing country governments will be fought out through trade negotiations, international courts and backdoor diplomacy, as well as public campaigning. Definitely one to watch.

January 23, 2014

Is the British development bubble a good thing? Reflections after another session at DFID.

To be an aid and development wonk based in London is to inhabit a very unrepresentative bubble. Beyond these shores, Australia has  followed Canada in downgrading aid by absorbing it back into the foreign ministry, and subordinating aid policy more explicitly to national self interest. In Europe, most governments are cutting their aid budgets as part of their austerity packages. Wherever I go, people ask me why the UK government is bucking the trend, ramping up aid as it cuts other (far more vote-catching) budget lines, and to be honest, I struggle for an answer. The development NGOs claim it’s all down to our wonderful lobbying and public awareness work, but a vibrant green NGO scene hasn’t had much success on environmental policy, so not sure that stands up.

followed Canada in downgrading aid by absorbing it back into the foreign ministry, and subordinating aid policy more explicitly to national self interest. In Europe, most governments are cutting their aid budgets as part of their austerity packages. Wherever I go, people ask me why the UK government is bucking the trend, ramping up aid as it cuts other (far more vote-catching) budget lines, and to be honest, I struggle for an answer. The development NGOs claim it’s all down to our wonderful lobbying and public awareness work, but a vibrant green NGO scene hasn’t had much success on environmental policy, so not sure that stands up.

Organizationally, in addition to a disproportionate number of big development NGOs, the UK has a cluster of top notch thinktanks (IDS, ODI, IIED), generating a rich intellectual exchange on ideas in development and aid. This is backed up by dozens of development studies courses at undergrad and post grad levels (really hope they can all find jobs one day) and globally renowned academics (Robert Chambers, Paul Collier, am I allowed to claim Ha Joon Chang for the UK?) The London-based Guardian is way out in front on its coverage of development, with two separate (and excellent) sites: Poverty Matters and the Development Professionals Network. Everyone bumps into each other at seminars, parties etc – there is a constant intellectual buzz.

The strengths and weaknesses of this British development bubble came home to me last week, as I attended a DFID seminar on ‘beneficiary feedback and the rigour of evidence.’ 50 DFID staff and NGO evaluation wallahs, some great speakers, and a genuine, nuanced and well-informed exchange on the issues.

So what were the downsides? (Hey I work for an NGO, there’s always a downside.) For starters, the title – ‘beneficiary feedback’ made a lot of people cringe. As Robert Chambers argued, words matter, and that phrase establishes a clear frame of them/us, upper/lower. We do stuff to them, then ask them for feedback on whether it was helpful and congratulate ourselves on our inclusiveness. Imagine we used the phrase ‘mutual accountability’ instead, and really meant it.

Second, as panellist Jeremy Holland pointed out, the ‘who’ is often more important than the ‘what’ or the ‘how’. Who provides the feedback? Who do they feed back to –other local people, or experts/donors/academics? Who evaluates the data? Who decides what is good quality and what isn’t?

To which I would add, who is in the room at DFID? Because on a quick skim, I saw 50 white faces, not one black or Asian one (the gender balance was OK). If the British Bubble leads to that kind of skewed ‘voice’, that’s pretty worrying, not least because the of the post colonial baggage that goes with being ‘Great Britain’. Check out the handy map of the very very few countries that the UK has not invaded.

Third, which side of the brain are we using? Robert argued strongly that the whole aid business is far too ‘left side’ (numbers, evidence, linear systems, the world as an independent external object of study through cleverly designed observation). Robert calls this the ‘things’ hemisphere, whereas the right hand side corresponds to ‘people’ – relationships, complexity, systems. What do we lose by adopting a left-sided view of the world?

Fourth, and this may have just been down to excessive politeness (another failing of the British Bubble), there seemed a general desire to move on from trench warfare over what constitutes evidence (Big Push Back Forward v RCTs – all criticisms of which are now dismissed as ‘straw men’), and discuss how to improve both qualitative and quantitative methods, and select the right combination of methods for any given area of enquiry. Interestingly, Robert argued that cost effectiveness is a much better/less loaded word for what we seek than ‘rigour’ (which is often equated with quantitative methods), provided ‘cost’ includes human and financial costs and benefits. We need to recognize that both quantitative and qualitative methods can either be rigorous or rubbish, depending on how they are implemented.

Stefan Dercon, DFID’s chief economist, made the useful suggestion that a more conventional left-hand-side rigour should be applied to the selection of people to talk to, so that you understand ‘how they fit into society’, what voices they represent and what the information they share can (and importantly, cannot) tell you. But that how you then talk to them should use a range of techniques, designed to fit any given context.

And one other rather intriguing suggestion (didn’t catch the name of the member of the audience from whom it came): the current way of exchanging knowledge is very vertical – gurus like the panellists speak, write, blog, and their wisdom supposedly percolates down to the grateful footsoldiers of the aid business and academia (maybe even beyond). Instead of panels, why not ask the panellists to do an online surgery, where people who are actually working on this in the field (maybe even some beneficiaries…) can ask for guidance and suggestions on how to improve their work. Has anyone tried this?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers