Duncan Green's Blog, page 194

March 12, 2014

What can would-be African lions learn from the Asian tigers? Itâs all about how urban elites see farmers, according to ODI.

I am both inspired and alarmed by the work coming out of ODI on âDevelopmental Regimes in Africaâ. In previous posts, Iâve moaned at some length about its political infatuation with Mussolini style âbig menâ who get stuff done. But today, itâs time for a happy face.

Sources of developmental ambition in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, by David Henley and Ahmad Helmy Fuady, is a brilliant

Indonesia’s Suharto and Nigeria’s Obasanjo – nice hats, v different views on peasants

exposition on what would-be African lions can learn from the Asian tigers:

âSoutheast Asian  countries could reduce poverty fast because their  governments prioritised pro-poor agricultural and rural  development in both political and budgetary terms, as well as providing sound macroeconomic management  and conditions of economic freedom (especially for  peasant farmers).  Public investments â in irrigation, research, input subsidies, agricultural extension, price stabilisation, and rural infrastructure, education and health care â raised the productivity and profitability of smallholder farms. In Africa, by contrast, few countries have ever combined economic freedom and sound macroeconomic management with pro-poor, pro-rural public spending.â

To explore these differences, the authors look at eight countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda.

First they debunk the âyou need a massive external threat like the Chinese Revolution to make leaders cooperate and build the nationâ school of thought, concluding:

âThe impact of such threats on the political interests of decision-making elites does not fully explain the differences in policy stance between and among African and Southeast Asian countries. Â Differences in assumptions about the nature of the development process are just as important. This has major policy implications. It means priority should be given to changing the mindsets of African leaders by stressing that successful development elsewhere in the world has been achieved with strategies that are inclusive, pro-poor and pro-rural.â

Then it gets interesting, with a discussion of ideas â the âlearned assumptionsâ of Asian and African elites (see table):

Then it gets interesting, with a discussion of ideas â the âlearned assumptionsâ of Asian and African elites (see table):

âRegardless of political interests and calculations, even African leaders of rural origin tend  to see rural life and rural people less positively than  their Southeast Asian counterparts. These different attitudes have historical roots. In Southeast Asia there is a long tradition of indigenous urbanism. In Africa, many of todayâs cities are colonial in origin, and were seen as alien European enclaves for generations. An African who moved from the countryside to the city in the early twentieth century was crossing a cultural divide.

One legacy of this transformation has been a collective assumption of developmental dualism: a conviction that progress can only be achieved by a quantum leap from (rural) backwardness to (urban) modernity. Â In Southeast Asia the colonial experience involved less of a rupture with the past.â

This is followed by some thought-provoking âso whatsâ for policy makers:

âClearly, international actors cannot create the kind of revolutionary threat that helped to inspire such policies in Asia. There is little evidence that electoral democracy can generate the same salutary political pressure on African (or indeed Asian) governments.Nor is it possible to alter colonial history or the cultural factors that have shaped the attitudes of  Africaâs leaders and intellectuals towards rural  and agricultural development.

However, persuading people to change learned attitudes is still easier than trying to reconfigure the national political forces that constrain their actions. Given the common perception among African leaders that policy guidance by international actors has neocolonial overtones, such guidance must be sensitive and support national policy ownership.

The most promising approach, therefore, is to help change the mindsets of African elites by drawing their attention to the fact that successful development elsewhere in the world has been achieved largely through inclusive, pro-poor, pro-rural strategies. This should take precedence over historically less well founded finger-wagging on the importance of good governance, democracy or even free trade.â

And guess what, not a single mention of aid, cooperation or donors. Cool, eh?

What can would-be African lions learn from the Asian tigers? It’s all about how urban elites see farmers, according to ODI.

I am both inspired and alarmed by the work coming out of ODI on ‘Developmental Regimes in Africa’. In previous posts, I’ve moaned at some length about its political infatuation with Mussolini style ‘big men’ who get stuff done. But today, it’s time for a happy face.

Sources of developmental ambition in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, by David Henley and Ahmad Helmy Fuady, is a brilliant

Indonesia’s Suharto and Nigeria’s Obasanjo – nice hats, v different views on peasants

exposition on what would-be African lions can learn from the Asian tigers:

‘Southeast Asian countries could reduce poverty fast because their governments prioritised pro-poor agricultural and rural development in both political and budgetary terms, as well as providing sound macroeconomic management and conditions of economic freedom (especially for peasant farmers). Public investments – in irrigation, research, input subsidies, agricultural extension, price stabilisation, and rural infrastructure, education and health care – raised the productivity and profitability of smallholder farms. In Africa, by contrast, few countries have ever combined economic freedom and sound macroeconomic management with pro-poor, pro-rural public spending.’

To explore these differences, the authors look at eight countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda.

First they debunk the ‘you need a massive external threat like the Chinese Revolution to make leaders cooperate and build the nation’ school of thought, concluding:

‘The impact of such threats on the political interests of decision-making elites does not fully explain the differences in policy stance between and among African and Southeast Asian countries. Differences in assumptions about the nature of the development process are just as important. This has major policy implications. It means priority should be given to changing the mindsets of African leaders by stressing that successful development elsewhere in the world has been achieved with strategies that are inclusive, pro-poor and pro-rural.’

Then it gets interesting, with a discussion of ideas – the ‘learned assumptions’ of Asian and African elites (see table):

Then it gets interesting, with a discussion of ideas – the ‘learned assumptions’ of Asian and African elites (see table):

‘Regardless of political interests and calculations, even African leaders of rural origin tend to see rural life and rural people less positively than their Southeast Asian counterparts. These different attitudes have historical roots. In Southeast Asia there is a long tradition of indigenous urbanism. In Africa, many of today’s cities are colonial in origin, and were seen as alien European enclaves for generations. An African who moved from the countryside to the city in the early twentieth century was crossing a cultural divide.

One legacy of this transformation has been a collective assumption of developmental dualism: a conviction that progress can only be achieved by a quantum leap from (rural) backwardness to (urban) modernity. In Southeast Asia the colonial experience involved less of a rupture with the past.’

This is followed by some thought-provoking ‘so whats’ for policy makers:

‘Clearly, international actors cannot create the kind of revolutionary threat that helped to inspire such policies in Asia. There is little evidence that electoral democracy can generate the same salutary political pressure on African (or indeed Asian) governments.Nor is it possible to alter colonial history or the cultural factors that have shaped the attitudes of Africa’s leaders and intellectuals towards rural and agricultural development.

However, persuading people to change learned attitudes is still easier than trying to reconfigure the national political forces that constrain their actions. Given the common perception among African leaders that policy guidance by international actors has neocolonial overtones, such guidance must be sensitive and support national policy ownership.

The most promising approach, therefore, is to help change the mindsets of African elites by drawing their attention to the fact that successful development elsewhere in the world has been achieved largely through inclusive, pro-poor, pro-rural strategies. This should take precedence over historically less well founded finger-wagging on the importance of good governance, democracy or even free trade.’

And guess what, not a single mention of aid, cooperation or donors. Cool, eh?

March 11, 2014

How can advocacy NGOs become more innovative? Your thoughts please.

Innovation. Who could be against it? Not even Kim Jong Un, apparently. People working on aid and development spend an increasing time discussing it – what is it? How do we get more of it? Who is any good at it? Innovation Tourette’s is everywhere.

Most of that discussion takes place in areas such as programming (what we do on the ground) or internal management (the unquenchable urge to restructure), drawing on innovation thinking in the private sector, government and academia.

But another (increasingly important) area of our work – advocacy/influencing – feels a bit absent from the innovation circus, so I’ve  been asked to crowdsource a few ideas. Help me out here.

been asked to crowdsource a few ideas. Help me out here.

In advocacy, we see plenty of innovation already, in new themes (e.g. a range of tax campaigns in the wake of the financial crisis) and players (online outfits such as Avaaz and change.org), but also a fair amount of business as usual: the cycle of policy papers, recommendations, lobby meetings, media work and consultations grinds on, not always to great effect.

At a higher level, there is lots of really innovative thinking going on about how to operate in complex systems, such as ODI’s work on hybrid institutions, or Matt Andrews and Lant Pritchett on ‘problem driven iterative adaptation’, but that tends to be directed at the big players, like governments, bilateral donors and the World Bank, with few links to humble NGOs doing single issue campaigns.

So my question is, where/how to be more systematic in supporting innovation in the advocacy work of large international NGOs and other aid organizations? The challenge is not just to have the odd new idea, but to run the organization in such a way that they keep flowing. Some initial thoughts:

Ways of Working/Management

Steal more: If Google and other high tech innovators stay ahead of the curve by buying up startups with new ideas, why don’t we? Annual performance reviews for advocacy staff should include the question: ‘what ideas have you stolen from smaller, more agile organizations?’ After all, when I was at CAFOD, getting Oxfam to steal my ideas was one of my objectives.

Spin offs: An alternative lesson from Google is to spin off lots of start ups, and leave them to sink or swim. Over the years, we’ve had some big successes such as New Internationalist or Fairtrade Foundation. Why not make it more systematic?

Change staff culture: In INGOs, it sometimes seems like a badge of honour to be 120% committed, but that carries a risk that hard working advocacy types have no time to read, think or innovate. I am reminded of ‘political coughs’ from the 80s – overwork, no sleep, bad diet + too many roll-ups meant any self respecting activist had a permanent cough and looked like they hadn’t seen daylight for months (they often hadn’t). Contrast that with Google’s famous “20% time,” which allows employees to take one day a week to work on side projects.

Change management culture: Tim Harford, in his book Adapt: Why Success Always Starts with Failure (review here) says ‘Adaptive organizations need to decentralize and become comfortable with the chaos of different local approaches and the awkwardness of dissent from junior staff.’ How to do this? Harford comes up with a ‘Three step recipe for successful adapting: try new things, in the expectation that some will fail; make failure survivable, because it will be common; and make sure that you know when you have failed…… distinguishing success from failure, oddly, can be the hardest task of all.’

Embrace risk: Learning from Google (again): the need for aid agencies to consider their operations as a ‘risk portfolio’. Should we be more explicit in seeking a balance between safe bet activities and high risk/high return moonshots? I fear that currently we try to minimise risk on each separate activity, producing an overall portfolio skewed towards the conservative and low risk/low innovation end.

Embrace risk: Learning from Google (again): the need for aid agencies to consider their operations as a ‘risk portfolio’. Should we be more explicit in seeking a balance between safe bet activities and high risk/high return moonshots? I fear that currently we try to minimise risk on each separate activity, producing an overall portfolio skewed towards the conservative and low risk/low innovation end.

Who we work with:

Unusual suspects: who cares about our issue and has influence, but is not getting any attention from us? Grey Panthers could be huge, for example, but barely get a look in.

Finding new ideas:

Positive deviance: what advocacy by us or other orgs, has gone better than predicted? Go back and find out why.

Don’t just set up an innovation fund: According to Exfam innovation guru Nicholas Colloff ‘They quickly find themselves subsidizing things that people cannot finance any other way (which may have nothing whatsoever to do with ‘innovation’)!’

Get out more:

Give people a day a month to visit ‘the outside world’ with no greater agenda than to look and learn (and no requirement to bring anything back other than the business cards of the people they meet). The good thing about working with Oxfam is that you can get yourself invited virtually anywhere. Seek out people who are relevant but different – not other NGOistas, but say, community organizers, think tanks, faith leaders even (gasp!) right wing organizations (after all, they’ve been doing pretty well on the influencing business).

Give talks and not simply the apparently ‘important’ ones, or to the usual suspects. I get a lot of new ideas from the increasing number of meetings where I am the only NGO person in the room.

Count the source of your e-mails (even if only for a month) and see how many come from other people in your own organization (prepare to be appalled).

And scariest of all (back to Nicholas): ‘Get them reading the Daily Mail – a penance I know but the most influential paper in the UK and, in fact, difficult to stereotype! In truth, the simple act of reading something you are not familiar with is surprisingly stimulating.’

I think that may be a step too far…

So over to you for links and suggestions, examples of organizations doing consistently innovative advocacy work or anything else you think might help, including your favourite gurus.

March 10, 2014

How can you tell whether a Multi-Stakeholder Initiative is a total waste of time?

Exfamer turned research consultant May Miller-Dawkins (@maykmd) tries to sort out diamonds from dross among the ever-proliferating ‘multi- stakeholder initiatives’.

stakeholder initiatives’.

Have you ever had to decide whether or not to join a multi-stakeholder initiative? When I was at Oxfam there was a disagreement about whether or not to join a fledgling MSI. Some staff believed that the industry was going to use the process as greenwash while others thought this was a real chance to influence the private sector, when other strategies had led to stalemate.

As MSIs proliferate, NGOs face these decisions more frequently. In the absence of a crystal ball or a track record, how can NGOs distinguish between the potential (ethically sourced, of course) diamonds, and the misleading twinkle of a cubix zirconia?

One familiar way in for NGOs is to look at the forms of participation that are being proposed – asking the same questions as in so many development programs. Who gets to participate? Who gets to decide?

As it turns out MSIs tend to legitimate their enterprise on the basis of participation. A study (ungated version here) by Phillip Pattberg and Klaus Dingwerth found that even in their own communications, MSIs emphasise their multi-stakeholder composition and the participation of particular groups even more than actual results. Of course all MSIs have “participation” (at a minimum of the private sector and civil society) as a key feature. But digging deeper, you see that the types of participation vary in important ways.

First off there are “representative” forms of participation. These focus on stakeholder representation (for example into the common chambers structure seen in Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC), Roundtable on Palm Oil Sustainability and Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials) and internal representation of the scheme’s members through elected Boards (e.g. 4C Association, FSC, and many others).

Secondly, many schemes are “deliberative”. These schemes focus on dialogue and frequently make decisions by consensus (for example, the Roundtable on Responsible Soy “aims to facilitate global dialogue”, the Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol was developed through dialogue amongst a forum and then moved to an ongoing chambers structure). Some recognise the particular experience and knowledge of marginalised or oppressed groups and try to ensure that they are heard and respected (the World Commission on Dams, an early form of MSI, invested in getting the testimony of dam-affected people as well as having them represented on the Commission).

A third strand of participation is more decidedly “functional”. Here the focus is on solving problems, drawing on expertise (whether narrowly or widely conceived), or resolving conflict (for example the Alliance for Water Stewardship and the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation). The extreme of functional forms of participation would be co-option that defuses opposition without delegating real authority.

Lastly, it is important to note that participation in MSIs is not limited to those who voluntarily choose to join. Groups participate in schemes as “outsiders” in a range of ways – by refusing to join, campaigning and monitoring (for example, the Bank Information Center’s monitoring of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, or campaigning against the Fair Labor Association). In fact, some experience from social change campaigning demonstrates that civil society are more effective at influencing change in corporate practice when different groups play insider and outsider roles in MSIs.

A stakeholder you can believe in

So, how can better understanding the types of participation in MSIs guide decisions about joining or starting MSIs? Here are a few ideas:

- If the most important principle to your organisation is that people who are likely to be affected by a scheme are involved in its creation then you’ll want to have a representative design, but one which pays adequate attention to who actually participates. This can mean minimum proportions of “chambers” or voting rights to particular groups (eg producers or workers – for example the Fair Labelling Organization has 4 Producer seats on the Board) and adequately resourcing the participation of southern civil society and groups that directly represent workers, producers, Indigenous peoples and other constituencies.

- If you think the conflict between an industry and civil society is a fundamental clash of world-views, then a deliberative approach may work, provided that the process allows adequate time and respect for the kinds of knowledge and expertise that sit on either side of the divide. This may require going beyond international meetings and technical documents, to include visits, immersions, testimony and ensuring a balance of participants and presenters from all sides. Deliberative schemes can be a way to get an industry that is highly reluctant (and maybe battle weary) around the table. However, a lack of focus on the process of deliberation and decision-making in the beginning can lead to a situation where NGOs become locked into a process they have sunk significant time and energy into. To avoid this, NGOs should at least have their own exit strategies – potentially agreed with their partners or allies – if the dialogue does not produce sufficient results.

- Where you think there is genuine commitment to change in an industry, a collaborative approach may be the way to go – by starting small on pilots and programs, and agreeing to stay focused on solving specific problems. The dangers of the collaborative route can be overlooking the political dimensions of the issues at hand – including disagreements between different groups within the amorphous categories of “civil society” and the “private sector”. The fights between the NGOs and companies that get involved in MSIs can pale in comparison to the disagreements between civil society groups about the right strategy.

- Problems with scientific dimensions – such as sustainable fisheries – require expert advice. The terms of expert advice are important (is the expert committee’s advice binding on the decision-makers?). However, be wary of schemes that construe civil society input itself as “expert” input or relegate it to an expert committee with no decision-making authority. This can show that sustainability is being seen as a technical problem to be solved and different views of what sustainability may look like could be brushed aside.

- If you want to work inside a scheme but also understand that it is important that other groups are able to campaign and monitor from the outside you’ll want to make sure that the MSI is fairly transparent – that documents, minutes of meetings, and results of assessments (if they exist) are published, that there is regular consultation, and that reporting and monitoring can be verified by third parties unaffiliated with the scheme.

There is no perfect design for an MSI. However, with a couple of decades of MSI experience under our collective belts and a better understanding of their potential and limits, careful attention to the different forms of participation at the front end can hopefully lead to better results at the other.

MSI veterans and observers – what’s your experience? What forms of participation do you think means that MSIs are more likely to deliver?

March 7, 2014

âHopeâ: a new fund to promote womenâs rights in the Arab Spring countries (and happy International Womenâs Day)

This International Womenâs Day post comes from Serena Tramonti (right), with contributions from Rania

This International Womenâs Day post comes from Serena Tramonti (right), with contributions from Rania  Tarazi (left), both of Oxfamâs Middle East and North Africa (MENA) team

Tarazi (left), both of Oxfamâs Middle East and North Africa (MENA) team

Three years ago, weeks before the centenary of International Womenâs Day, Â I remember sitting in my living room in Manchester, watching on TV with hope and astonishment the brave women and men who were taking to the streets in the Arab World, reclaiming their right to live a dignified life and to make free decisions about how their countries were run.

Women were at the forefront of the Arab uprising protests. Images of women protesting, interviews with young women activists, were all over global media. A window of opportunity for real change seemed wide open; the governments of Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen were overthrown, new transitional political processes were introduced and leaders sworn in. This seemed a time ripe with opportunities for the advancement of womenâs rights in most Arab countries. As a woman, campaigner and activist myself, I could not but be moved and inspired by their courage.

But three years on, on the eve of International Womenâs Day, the sky is darker with political divisions, economic instability, societal  violence and conflict restraining the quest for womenâs empowerment. However there are also glimpses of light. At best, womenâs struggle to achieve the changes they aspired to resulted in successes such as the Moroccan and Tunisian constitutions of 2011 and 2014 respectively, and higher representation in elected bodies in many countries. At worst, womenâs rights seem to be going backwards, for example in Egyptâs abolition of parliamentary quotas for women and increased public violence. These days, I am still a mere spectator, but this time I am a little closer to the action, since I am working directly with those women who have been campaigning during the Arab uprisings – as part of Oxfamâs Amal programme team. Let me explain.

violence and conflict restraining the quest for womenâs empowerment. However there are also glimpses of light. At best, womenâs struggle to achieve the changes they aspired to resulted in successes such as the Moroccan and Tunisian constitutions of 2011 and 2014 respectively, and higher representation in elected bodies in many countries. At worst, womenâs rights seem to be going backwards, for example in Egyptâs abolition of parliamentary quotas for women and increased public violence. These days, I am still a mere spectator, but this time I am a little closer to the action, since I am working directly with those women who have been campaigning during the Arab uprisings – as part of Oxfamâs Amal programme team. Let me explain.

In the aftermath of the Arab uprisings in the region, political spaces have opened and regardless of the outcomes in each country, the relationship between citizens and states has changed irreversibly. As a result of this, many new organisations, groups and movements are emerging.

They have a lot to do. Women in the MENA Region (like in a lot of other regions of the world) remain largely under-represented in all three branches of government; judiciary, legislative, and executive. Many overarching reasons lie behind this: social norms, the tribal nature of a lot of Arab countries, as well as a legal environment that often hinders the advancement of women.

But one area where such exclusion is not universal, where women are given a chance to shine, is the social and informal sector. Building on that, Oxfam is today launching an “Innovation Fund”. The fund will give small grants to new organizations with creative and bold solutions to long-lasting challenges and reach informal and emerging groups through partnerships with established organizations.

The fund is part of the AMAL (âHopeâ in Arabic) programme, which works in four of the countries affected by the Arab uprisings: Tunisia, Morocco, Palestine and Yemen, in partnership with 13 local organizations. Oxfam and womenâs organizations are working together with women â often from poor communities – strengthening their confidence, knowledge of their rights and their campaigning and advocacy skills. As I am writing one of Oxfamâs partners in Morocco, La Fédération de la Ligue Démocratique des Droits des Femmes, is mobilising civil society to call for the implementation of Chapter 19 of their new Constitution, which requires the end of discrimination and equality between men and women.

‘Reflect’ training in Yemen

In rural Yemen too, Oxfamâs partner, the Yemeni Womenâs Union is creating spaces for women to come together to share their experiences, needs and aspirations and equip them with the practical skills and confidence to influence change in their lives and communities; word about these activities is spreading fast amongst Yemeni women and more discussion sessions than anticipated are being organized as a result.

Working on womenâs empowerment in Arab societies is an exciting and growing area of interest for Oxfam. The overall aims may be the same as in other regions, but the means differ. Especially following the Arab uprisings, the diversity in the region is surfacing more than ever, with those who are both proponents and opponents of womenâs rights all basing their views on a mix of values derived from the family and tribal culture, religion, tradition and social norms, as well as modernity and international human rights. Â The key is to take account of these differences and develop adapted messages that can build the alliances and coalitions needed to bring about positive change.

Whatever the short term ups and downs of the struggle for womenâs rights in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the experience of protest and organization have left a legacy among the regionâs women of confidence in their ability to âraise the roofâ (to use the Arabic expression). It is the energy of women like these, who are hungry for change and hopeful for a better future where they can be the masters (mistresses!) of their own destiny, that Oxfam and its partners would like to celebrate this International Womenâs Day.

The Innovation Fund launched today offers small grants to emerging and new womenâs organizations in Tunisia, Yemen, Palestine and Morocco. Grantees will be able to access awards of and in-kind support of up to $35,000. For more information, see below.

Three years after the Arab uprisings, the energy and hunger for change â and womenâs influence and strong leadership within this – is needed more than ever. This time, I am pleased to be able to do more than just watch.

Applications for the Oxfam Amal Innovation Fund will be open until 15 April. Apply using the form below, forms should be returned to Amal@oxfam.org.uk.

Oxfam Amal Innovation Fund Application Form

Oxfam Amal Innovation Fund Call for Proposals

Oxfam Amal Innovation Fund Budget Template

‘Hope’: a new fund to promote women’s rights in the Arab Spring countries (and happy International Women’s Day)

This International Women’s Day post comes from Serena Tramonti (right), with contributions from Rania

This International Women’s Day post comes from Serena Tramonti (right), with contributions from Rania  Tarazi (left), both of Oxfam’s Middle East and North Africa (MENA) team

Tarazi (left), both of Oxfam’s Middle East and North Africa (MENA) team

Three years ago, weeks before the centenary of International Women’s Day, I remember sitting in my living room in Manchester, watching on TV with hope and astonishment the brave women and men who were taking to the streets in the Arab World, reclaiming their right to live a dignified life and to make free decisions about how their countries were run.

Women were at the forefront of the Arab uprising protests. Images of women protesting, interviews with young women activists, were all over global media. A window of opportunity for real change seemed wide open; the governments of Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen were overthrown, new transitional political processes were introduced and leaders sworn in. This seemed a time ripe with opportunities for the advancement of women’s rights in most Arab countries. As a woman, campaigner and activist myself, I could not but be moved and inspired by their courage.

But three years on, on the eve of International Women’s Day, the sky is darker with political divisions, economic instability, societal  violence and conflict restraining the quest for women’s empowerment. However there are also glimpses of light. At best, women’s struggle to achieve the changes they aspired to resulted in successes such as the Moroccan and Tunisian constitutions of 2011 and 2014 respectively, and higher representation in elected bodies in many countries. At worst, women’s rights seem to be going backwards, for example in Egypt’s abolition of parliamentary quotas for women and increased public violence. These days, I am still a mere spectator, but this time I am a little closer to the action, since I am working directly with those women who have been campaigning during the Arab uprisings – as part of Oxfam’s Amal programme team. Let me explain.

violence and conflict restraining the quest for women’s empowerment. However there are also glimpses of light. At best, women’s struggle to achieve the changes they aspired to resulted in successes such as the Moroccan and Tunisian constitutions of 2011 and 2014 respectively, and higher representation in elected bodies in many countries. At worst, women’s rights seem to be going backwards, for example in Egypt’s abolition of parliamentary quotas for women and increased public violence. These days, I am still a mere spectator, but this time I am a little closer to the action, since I am working directly with those women who have been campaigning during the Arab uprisings – as part of Oxfam’s Amal programme team. Let me explain.

In the aftermath of the Arab uprisings in the region, political spaces have opened and regardless of the outcomes in each country, the relationship between citizens and states has changed irreversibly. As a result of this, many new organisations, groups and movements are emerging.

They have a lot to do. Women in the MENA Region (like in a lot of other regions of the world) remain largely under-represented in all three branches of government; judiciary, legislative, and executive. Many overarching reasons lie behind this: social norms, the tribal nature of a lot of Arab countries, as well as a legal environment that often hinders the advancement of women.

But one area where such exclusion is not universal, where women are given a chance to shine, is the social and informal sector. Building on that, Oxfam is today launching an “Innovation Fund”. The fund will give small grants to new organizations with creative and bold solutions to long-lasting challenges and reach informal and emerging groups through partnerships with established organizations.

The fund is part of the AMAL (‘Hope’ in Arabic) programme, which works in four of the countries affected by the Arab uprisings: Tunisia, Morocco, Palestine and Yemen, in partnership with 13 local organizations. Oxfam and women’s organizations are working together with women – often from poor communities – strengthening their confidence, knowledge of their rights and their campaigning and advocacy skills. As I am writing one of Oxfam’s partners in Morocco, La Fédération de la Ligue Démocratique des Droits des Femmes, is mobilising civil society to call for the implementation of Chapter 19 of their new Constitution, which requires the end of discrimination and equality between men and women.

‘Reflect’ training in Yemen

In rural Yemen too, Oxfam’s partner, the Yemeni Women’s Union is creating spaces for women to come together to share their experiences, needs and aspirations and equip them with the practical skills and confidence to influence change in their lives and communities; word about these activities is spreading fast amongst Yemeni women and more discussion sessions than anticipated are being organized as a result.

Working on women’s empowerment in Arab societies is an exciting and growing area of interest for Oxfam. The overall aims may be the same as in other regions, but the means differ. Especially following the Arab uprisings, the diversity in the region is surfacing more than ever, with those who are both proponents and opponents of women’s rights all basing their views on a mix of values derived from the family and tribal culture, religion, tradition and social norms, as well as modernity and international human rights. The key is to take account of these differences and develop adapted messages that can build the alliances and coalitions needed to bring about positive change.

Whatever the short term ups and downs of the struggle for women’s rights in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the experience of protest and organization have left a legacy among the region’s women of confidence in their ability to ‘raise the roof’ (to use the Arabic expression). It is the energy of women like these, who are hungry for change and hopeful for a better future where they can be the masters (mistresses!) of their own destiny, that Oxfam and its partners would like to celebrate this International Women’s Day.

The Innovation Fund launched today offers small grants to emerging and new women’s organizations in Tunisia, Yemen, Palestine and Morocco. Grantees will be able to access awards of and in-kind support of up to $35,000. For more information, see below.

Three years after the Arab uprisings, the energy and hunger for change – and women’s influence and strong leadership within this – is needed more than ever. This time, I am pleased to be able to do more than just watch.

Applications for the Oxfam Amal Innovation Fund will be open until 15 April. Apply using the form below, forms should be returned to Amal@oxfam.org.uk.

Oxfam Amal Innovation Fund Application Form

Oxfam Amal Innovation Fund Call for Proposals

Oxfam Amal Innovation Fund Budget Template

March 6, 2014

Fairtrade: celebrating the first 20 years. Whatâs next?

Rachel Wilshaw, Oxfamâs Ethical Trade Manager looks back on the astonishing 20 year rise of Fairtrade.

The Fairtrade Foundation launched its first products â coffee, chocolate and tea – 20 years ago. As one of the Oxfam types who sat around in the late 80s debating whether UK supermarkets would ever stock âalternative tradeâ products, this is a moment to savour.

Weâve come a long way. Sales in 2013 were £1.78 billion in the UK alone â half of the global total, and have kept growing despite the recession. 90% of UK consumers know and trust the FAIRTRADE Mark, and that familiarity underpins many of the subsequent trade justice campaigns on everything from âclean clothesâ to the WTO. 1.3 million small farmers and workers in 70 countries have seen positive impacts, from better incomes to stronger collective organisation and the social premium (£23 million from UK sales in 2013) has enabled investment in health, housing and education schemes. So thereâs a lot to celebrate as we come to the end of this yearâs Fairtrade Fortnight.

Bananas are one of the movementâs success stories, with a third of the UK market now Fairtrade, helped by 100% sourcing commitments from Sainsburyâs, The Co-op and Waitrose.

But all is not rosy for Fairtrade Foundation in the garden of supermarket supply chains, as its recent report on Britainâs Bruising Banana Wars highlights. The retail price of loose bananas has nearly halved in the last 10 years in the UK (though curiously not in Germany, France or Italy). But the cost of production for farmers has doubled in some regions. The double whammy of depressed prices and increased costs is causing problems at both ends of this simple supply chain.

But all is not rosy for Fairtrade Foundation in the garden of supermarket supply chains, as its recent report on Britainâs Bruising Banana Wars highlights. The retail price of loose bananas has nearly halved in the last 10 years in the UK (though curiously not in Germany, France or Italy). But the cost of production for farmers has doubled in some regions. The double whammy of depressed prices and increased costs is causing problems at both ends of this simple supply chain.

At the producer end, poverty is still the norm. In Ecuador only a quarter of households reliant on banana plantations earn an income above the poverty line. In Colombia many employers have responded to sustained pressure on prices by replacing permanent jobs with temporary ones, putting at risk Colombiaâs proud model of mature industrial relations.

At the supermarket end, every retailer spoken to by the Foundation in researching the report talked of the competitive pressure to keep banana prices low (particularly since it is one of the items used to compare one anotherâs retail prices and communicate back to consumers). In a 2009 interview with The Grocer magazine the CEO of Waitrose suggested that the banana price war is costing it £100,000 per week, i.e. it was selling below cost.

How can this be healthy for sustainability â economic, environmental or social? Consumers have benefited â and given that UK poverty is increasing this matters – but the direction of travel is all wrong for those who care about trade justice. Even the poorest consumers do not want those who are poorer to be exploited; 84% of people say they would pay a few pence extra if they know it will reach farmers and workers. Just 1p on the retail price of a banana could lift incomes by 20-30%. Oxfam came to the same conclusion, in its Poverty Footprint study with IPL, which estimated that just 5p on a £4 bunch of flowers could raise Kenyan flower workersâ wages to a living wage.

Tesco â keen to change its image following the horsemeat scandal – has at least committed to pay at least the Fairtrade minimum price wherever they source, though not the licence fee that pays for the premium and other investment; it needs to keep step with Asda, which was first to drop banana prices in 2002 after it was taken over by Walmart.

As it looks to the next 20 years, Fairtrade faces another challenge: competition from other ethical and environmental labels (438 of them at the last count, many of which do not back up their claims). Fairtrade stands out for its payment of a guaranteed minimum price, an additional social premium and the inclusion of southern producers and trade unions in its governance. It has responded to concerns about low plantation wages (see previous blog on wages in the tea industry) by strengthening its standard for hired labour and initiating a living wage benchmarking process.

By comparison, Rainforest Alliance (a labelling initiative with an environmental focus that is taking market share from Fairtrade) pays no minimum price or social premium, does not give priority to small farmers and is pretty weak on workersâ rights, with no commitment to a living wage or effective grievance mechanisms (itâs consulting on its standard until 11 March so why not make your voice heard). We welcome the fact that Rainforest Alliance is collaborating on a living wage benchmarking initiative, but without a commitment to this in their standard, how will its model enable higher wages to be paid?

Yet another challenge is that retailers canât talk about price as an issue for fear of falling foul of UK and EU competition law, which  prohibits agreements or practices that âdirectly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditionsâ.

prohibits agreements or practices that âdirectly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditionsâ.

Is this a trading and policy environment in which Fairtrade Foundation can flourish in the next 20 years? In such circumstances it is natural that the Foundation is debating changes to its system that would enable it to compete and grow sales in this tough environment. But what really needs to change is the goliath of a food system against which this ethical David is pitting itself, a system which is locked into a race to the bottom. We badly need retailers to be able to compete and cover the cost of sustainable production, so that the would-be good guys thrive.

Oxfam is on the case with its Behind the Brands campaign, in which the top 10 food and beverage companies are rated and ranked on seven issues vital to poverty alleviation. The transparent scorecard on which findings are based has attracted attention from activists and corporate investors alike, and galvanised corporate commitments on issues such as gender and land grabs that get left out of their CSR programmes.

Meanwhile the Foundation has published its own survey, rating supermarketsâ efforts to make bananas fair (researched by Ethical Consumer). I for one welcome the more assertive stance of the Foundation in taking this analysis public and spelling out the changes needed.

Of course there will be plenty of trade-offs and tensions as they do this, such as the difficulty of achieving both breadth of reach and depth of impact, and the difficulty of being radical enough for their activist supporters, while staying commercial enough for their multinational licensees. Itâs not easy to meet expectations when your mission is âto improve the trading position of producer organisations in the South and to deliver sustainable livelihoods for farmers, workers and their communitiesâ.

Of course there will be plenty of trade-offs and tensions as they do this, such as the difficulty of achieving both breadth of reach and depth of impact, and the difficulty of being radical enough for their activist supporters, while staying commercial enough for their multinational licensees. Itâs not easy to meet expectations when your mission is âto improve the trading position of producer organisations in the South and to deliver sustainable livelihoods for farmers, workers and their communitiesâ.

Surely itâs time â as the Foundation says – for some government intervention in the UK – to investigate the impact of banana pricing, to take action to make bananas fair, and to review whether competition law enables rights to be respected in the supply chain. Meanwhile retailers and traders should do their utmost to cover the cost of sustainable production and pay a living wage to workers.

Meanwhile, hats off to everyone involved and good luck for the next 20 years.

Fairtrade: celebrating the first 20 years. What’s next?

Rachel Wilshaw, Oxfam’s Ethical Trade Manager looks back on the astonishing 20 year rise of Fairtrade.

The Fairtrade Foundation launched its first products – coffee, chocolate and tea – 20 years ago. As one of the Oxfam types who sat around in the late 80s debating whether UK supermarkets would ever stock ‘alternative trade’ products, this is a moment to savour.

We’ve come a long way. Sales in 2013 were £1.78 billion in the UK alone – half of the global total, and have kept growing despite the recession. 90% of UK consumers know and trust the FAIRTRADE Mark, and that familiarity underpins many of the subsequent trade justice campaigns on everything from ‘clean clothes’ to the WTO. 1.3 million small farmers and workers in 70 countries have seen positive impacts, from better incomes to stronger collective organisation and the social premium (£23 million from UK sales in 2013) has enabled investment in health, housing and education schemes. So there’s a lot to celebrate as we come to the end of this year’s Fairtrade Fortnight.

Bananas are one of the movement’s success stories, with a third of the UK market now Fairtrade, helped by 100% sourcing commitments from Sainsbury’s, The Co-op and Waitrose.

But all is not rosy for Fairtrade Foundation in the garden of supermarket supply chains, as its recent report on Britain’s Bruising Banana Wars highlights. The retail price of loose bananas has nearly halved in the last 10 years in the UK (though curiously not in Germany, France or Italy). But the cost of production for farmers has doubled in some regions. The double whammy of depressed prices and increased costs is causing problems at both ends of this simple supply chain.

But all is not rosy for Fairtrade Foundation in the garden of supermarket supply chains, as its recent report on Britain’s Bruising Banana Wars highlights. The retail price of loose bananas has nearly halved in the last 10 years in the UK (though curiously not in Germany, France or Italy). But the cost of production for farmers has doubled in some regions. The double whammy of depressed prices and increased costs is causing problems at both ends of this simple supply chain.

At the producer end, poverty is still the norm. In Ecuador only a quarter of households reliant on banana plantations earn an income above the poverty line. In Colombia many employers have responded to sustained pressure on prices by replacing permanent jobs with temporary ones, putting at risk Colombia’s proud model of mature industrial relations.

At the supermarket end, every retailer spoken to by the Foundation in researching the report talked of the competitive pressure to keep banana prices low (particularly since it is one of the items used to compare one another’s retail prices and communicate back to consumers). In a 2009 interview with The Grocer magazine the CEO of Waitrose suggested that the banana price war is costing it £100,000 per week, i.e. it was selling below cost.

How can this be healthy for sustainability – economic, environmental or social? Consumers have benefited – and given that UK poverty is increasing this matters – but the direction of travel is all wrong for those who care about trade justice. Even the poorest consumers do not want those who are poorer to be exploited; 84% of people say they would pay a few pence extra if they know it will reach farmers and workers. Just 1p on the retail price of a banana could lift incomes by 20-30%. Oxfam came to the same conclusion, in its Poverty Footprint study with IPL, which estimated that just 5p on a £4 bunch of flowers could raise Kenyan flower workers’ wages to a living wage.

Tesco – keen to change its image following the horsemeat scandal – has at least committed to pay at least the Fairtrade minimum price wherever they source, though not the licence fee that pays for the premium and other investment; it needs to keep step with Asda, which was first to drop banana prices in 2002 after it was taken over by Walmart.

As it looks to the next 20 years, Fairtrade faces another challenge: competition from other ethical and environmental labels (438 of them at the last count, many of which do not back up their claims). Fairtrade stands out for its payment of a guaranteed minimum price, an additional social premium and the inclusion of southern producers and trade unions in its governance. It has responded to concerns about low plantation wages (see previous blog on wages in the tea industry) by strengthening its standard for hired labour and initiating a living wage benchmarking process.

By comparison, Rainforest Alliance (a labelling initiative with an environmental focus that is taking market share from Fairtrade) pays no minimum price or social premium, does not give priority to small farmers and is pretty weak on workers’ rights, with no commitment to a living wage or effective grievance mechanisms (it’s consulting on its standard until 11 March so why not make your voice heard). We welcome the fact that Rainforest Alliance is collaborating on a living wage benchmarking initiative, but without a commitment to this in their standard, how will its model enable higher wages to be paid?

Yet another challenge is that retailers can’t talk about price as an issue for fear of falling foul of UK and EU competition law, which  prohibits agreements or practices that ‘directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions’.

prohibits agreements or practices that ‘directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions’.

Is this a trading and policy environment in which Fairtrade Foundation can flourish in the next 20 years? In such circumstances it is natural that the Foundation is debating changes to its system that would enable it to compete and grow sales in this tough environment. But what really needs to change is the goliath of a food system against which this ethical David is pitting itself, a system which is locked into a race to the bottom. We badly need retailers to be able to compete and cover the cost of sustainable production, so that the would-be good guys thrive.

Oxfam is on the case with its Behind the Brands campaign, in which the top 10 food and beverage companies are rated and ranked on seven issues vital to poverty alleviation. The transparent scorecard on which findings are based has attracted attention from activists and corporate investors alike, and galvanised corporate commitments on issues such as gender and land grabs that get left out of their CSR programmes.

Meanwhile the Foundation has published its own survey, rating supermarkets’ efforts to make bananas fair (researched by Ethical Consumer). I for one welcome the more assertive stance of the Foundation in taking this analysis public and spelling out the changes needed.

Of course there will be plenty of trade-offs and tensions as they do this, such as the difficulty of achieving both breadth of reach and depth of impact, and the difficulty of being radical enough for their activist supporters, while staying commercial enough for their multinational licensees. It’s not easy to meet expectations when your mission is ‘to improve the trading position of producer organisations in the South and to deliver sustainable livelihoods for farmers, workers and their communities’.

Of course there will be plenty of trade-offs and tensions as they do this, such as the difficulty of achieving both breadth of reach and depth of impact, and the difficulty of being radical enough for their activist supporters, while staying commercial enough for their multinational licensees. It’s not easy to meet expectations when your mission is ‘to improve the trading position of producer organisations in the South and to deliver sustainable livelihoods for farmers, workers and their communities’.

Surely it’s time – as the Foundation says – for some government intervention in the UK – to investigate the impact of banana pricing, to take action to make bananas fair, and to review whether competition law enables rights to be respected in the supply chain. Meanwhile retailers and traders should do their utmost to cover the cost of sustainable production and pay a living wage to workers.

Meanwhile, hats off to everyone involved and good luck for the next 20 years.

March 5, 2014

The Civil Society Flashpoint: Why the global crackdown? What can be done about it?

This guest post comes from Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, drawing from their new report, Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire

This guest post comes from Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, drawing from their new report, Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire

When the concept of civil society took the international aid community by storm in the 1990s, many aid providers reveled in the alluring idea of civil society as a post-ideological, even post-political arena, a virtuous domain of nonpartisan organizations advancing a loosely defined notion of the public good. Funding civil society appealed as a way for aid providers to help shape the sociopolitical life of other countries without directly involving themselves in politics with a capital “P.” Power holders in aid-receiving countries, uncertain what to make of this fuss over civil society, were initially inclined to see it as a marginal enterprise populated by small, basically feckless groups of idealistic do-gooders.

Those days are long gone. Whether in Egypt, Turkey, Venezuela, or quite vividly in Ukraine during the final months of Yanukovych’s rule, a growing number of governments now treat the concept of civil society as a code word for powerful political subversives, usually assumed to be doing the bidding of the West. Power holders often fear NGOs more than they do opposition parties, seeing the former as nimble, technologically-savvy actors capable of activating sudden outbursts of mass protest.

Manifesting this changed perspective, more than 50 countries in recent years have enacted or seriously considered legislative or other

restrictions on the ability of NGOs to organize and operate. At the core of many of these efforts are measures to impede or block foreign funding for civil society groups—including administrative and legal obstacles, propaganda campaigns against NGOs that accept foreign funding, and harassment or expulsion of external aid groups offering civil society support.

Why is this happening? In short, because civil society has been making itself felt. The lion’s share of the most significant political upheavals of the past 15 years have come about as the result of assertive citizen activism, starting in Slovakia and Serbia in the late 1990s, continuing through Georgia, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, and Lebanon in the early 2000s, and most recently in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and elsewhere in the Arab world. The nightmare scenario for power holders in many countries has become waking up one morning and learning that thousands of ordinary citizens have gathered in the main square of the capital demanding justice, vowing not to go home until they get it.

In fact, the protest movements that have driven political change in these countries are not necessarily what the Western aid

community refers to (and what it funds) when it talks about civil society. In some of these cases, such as in Tunisia and Egypt in 2011, Western-funded NGOs played only a very secondary role, at most. The protests were driven instead by much more diffuse and organic forms of citizen activism that largely bypassed the donor model of formalized, technocratic advocacy groups. Yet such complexities get swept aside by power holders nervous about simmering public discontent and inclined to blame the West for any serious protests they face.

After several years spent improvising responses to the growing pushback against civil society, public and private funders are starting to respond in more concerted ways. They are mounting tactically sophisticated pressure campaigns to try to head off repressive NGO laws in aid receiving countries. They are effectively supporting efforts on the multilateral level to reinforce the normative framework for civil society space, for example through the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association. They are exploring how to employ new technological tools to physically distance international aid from the most challenging trouble spots without giving up on directly reaching civil society activists. And they are opening up important new debates about how alternative sources of civil society funding could break the habit of dependence on external support.

But many dilemmas and hard questions still lie ahead. These include:

1) How to most effectively assert the Western interest in protecting civil society space. Raising civil society concerns at the highest

diplomatic levels helps give clout to Western objections to bad NGO draft laws and other restrictive measures. Yet high-level diplomatic engagement can also have counterproductive effects. As one Egyptian analyst explained to us regarding the serious tensions in Egypt over Western civil society support, the more that senior Western officials directly pressure Egyptian officials about the need to allow Western funding to Egyptian NGOs, the more those officials are convinced that such funding must be about getting Egyptian NGOs to serve Western agendas.

2) Whether greater aid transparency is part of the answer. In response to the heightened, often almost absurdly conspiratorial suspicions in many quarters about Western civil society aid, some aid practitioners contend that increasing the transparency of aid flows will help defuse the accusations and tensions surrounding such work. Yet other practitioners seriously object to this view, fearing that too much transparency will put aid recipients in greater jeopardy and reduce external funders’ ability to carry out politically agile assistance in sensitive contexts.

3) Whether reducing aid dependency will mean aid retreat. The idea of shifting the civil society assistance paradigm away from dependence on Western financing toward technologically innovative methods of local funding like crowdsourcing is of course appealing. But some civil society activists fear that under the umbrella of changing the paradigm to protect civil society organizations under siege, aid providers will walk away from their commitment to local activists as well as civil society development more broadly.

4) Divisions among aid providers. Different aid providers fund civil society in developing countries for different purposes. A number of developmentally oriented aid organizations believe that those working on more politically assertive democracy and human rights assistance are responsible for triggering governmental pushback that ends up affecting the credibility and access of all external funders. As a result, they are disinclined to cooperate in forging common responses to pushback. In other words, the complex ongoing debate within the development aid community over how political aid should be and what working politically really means becomes even more fraught as pushback intensifies.

March 4, 2014

W(h)ither Democracy; Latin American progress; China’s tobacco problem and poor world cancer; climate change progress: a Developmentista’s Guide to this week’s Economist

Should I be worried about how much I enjoy The Economist? I get some stick from colleagues, who reckons it is surreptitiously  dripping neoliberal poison into my formerly socialist soul. But it’s just so good! On a good week, there are half a dozen must-read articles on development-related issues, which I try to tweet.

dripping neoliberal poison into my formerly socialist soul. But it’s just so good! On a good week, there are half a dozen must-read articles on development-related issues, which I try to tweet.

But based on last week’s issue, that may not be enough. So do you think I should run the occasional developmentista’s guide to the Economist, with summaries and links?

Here’s what I have in mind, based on the 1-7 March issue:

What’s Gone Wrong with Democracy? A beautifully crafted 6 page essay by someone or other (it’s very annoying that the magazine hardly ever credits authors). It starts with the big sweep of history:

‘By 1941 there were only 11 democracies left, and Franklin Roosevelt worried that it might not be possible to shield “the great flame of democracy from the blackout of barbarism”.’

Now, after the democratic surges of decolonisation and the collapse of the Soviet Union, democracy is in trouble again. Putin’s Russia; the Iraq war; collapse of the Arab Spring; South Africa’s disillusion with the ANC; backsliding in Turkey, Bangladesh, Thailand and Cambodia. Why? The global financial crisis and the rise of China (‘85% of Chinese are “very satisfied” with their country’s direction, compared with 31% of Americans’).

This has led to disillusion in democratic heartlands such as Western Europe, and much less pulling power elsewhere.

True to The Economist’s liberal democratic values, the essay then tries to argue that it’s not all bad, pointing out lots of experimentation (eg direct democracy, shifts to long term oversight), which is reversing the decline in places like California and Finland. And anyway:

‘China’s stunning advances conceal deeper problems. The elite is becoming a self-perpetuating and self-serving clique. The 50 richest members of the China’s National People’s Congress are collectively worth $94.7 billion—60 times as much as the 50 richest members of America’s Congress.’

But I have to say the description of the downside was a lot more persuasive than the reasons to be cheerful.

I find the best way to read the Economist is to see it as a clever, but rather right wing, participant in a seminar. Learn from them, but then try and spot any ideological sleight of hand (in this case slipping in the argument that a smaller state is the best way to defend democracy) and try to identify what is missing (I couldn’t see much, in this case – do tell me what I’ve missed).

So much for the cover story, but it’s often the bits and pieces in the back half of the magazine that are particularly useful for a development wonk. This week’s selection includes:

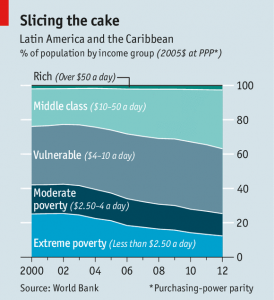

Sustaining social progress in Latin America: The region’s recent ability to combine growth, poverty reduction and falling income inequality seems to be running out of steam. It was driven by expansion in education, rising wages and cash transfers. Now the challenge is to improve quality of education, progressive tax reform and (this is the Economist, after all) structural reforms e.g. to the labour market. ‘Keeping the fall in poverty and inequality going may require a squeeze on the rich—but done cleverly, so as not to deter growth-enhancing investments.’

Sustaining social progress in Latin America: The region’s recent ability to combine growth, poverty reduction and falling income inequality seems to be running out of steam. It was driven by expansion in education, rising wages and cash transfers. Now the challenge is to improve quality of education, progressive tax reform and (this is the Economist, after all) structural reforms e.g. to the labour market. ‘Keeping the fall in poverty and inequality going may require a squeeze on the rich—but done cleverly, so as not to deter growth-enhancing investments.’

Big Tobacco, Chinese Style: More than half of Chinese men smoke (but only 2% of women). Smoking is on course to kill 100m Chinese people this century. Will the government’s new anti-smoking policies curb it? Probably not – consumption taxes are too low to make a difference, and the China National Tobacco Corporation has huge influence (and wants to expand into other countries).

Cancer in the Developing World: ‘Low- and middle-income countries accounted for 57% of the 14m people diagnosed with cancer worldwide in 2012—but 65% of the deaths. Cancer kills more people in poor countries than AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined.’

A surge in climate change legislation at national level: Backsliding in Australia, Japan and Canada gets all the headlines, but overall ‘in 66 countries, accounting for 88% of carbon emissions, almost half of parliaments passed climate-change or energy-efficiency acts in 2013…. the world’s stock of climate laws has risen steeply, from fewer than 50 in 2000 to almost 500 in 2013.’

And finally, Inequality v Growth – a summary of the much-tweeted new IMF paper that argues that in most countries a bit more redistribution is actually good for growth (but thinks Europe may have already gone too far).

So was that useful? Do you want a regular summary? I’d do a poll but can’t work out how to do it in the new format, and all the techies have gone off on holiday, sorry.

I guess if you still hate The Economist, you could always claim this will undermine sales……

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers