Duncan Green's Blog, page 192

March 28, 2014

Have we just squandered a good crisis, and a golden opportunity to kick-start climate action?

For years I, along with others like Alex Evans, have been saying âthe politics of global carbon reduction is stuck, it will require a major climate shock in the rich countries to unblock itâ. The argument is that major scandals, crises etc are required to create a sense of urgency, undermine coalitions of blockers, and convince everyone that a new approach is needed. The classic examples often involve wars and conflicts â the consolidation of the BritishÂ

welfare state after World War Two, or the transformation of Rwandan politics after the 1994 genocide.

Well weâve seen some pretty impressive weather shocks in the US and Europe in recent weeks â how is our prediction doing?

The floods have shifted public opinion a bit (see bar chart â before and after major floods spread across the UK, with accompanying analysis by Peter Kellner – the numbers are a bit old, anyone got anything more recent?). That tells us that more people think the floods are to do with climate change, but not whether they therefore give it greater political salience, which is what is needed for faster action. Weâll have to wait a couple of months to get the data on that.

But what struck me was the fragmented and ineffective response from the people who ought to have been ânot letting a good crisis go to wasteâ (Rahm Emmanuel). Politicians wandered around in their wellies pointing at water, or argued about dredging the rivers and spending more on flood defences. The occasional âwe told you soâ banner was unfurled for the cameras, but nothing on a par with the US environmental campaigns around 2012âs  superstorm Sandy. Where was the concerted, pre-planned (itâs not as if we didnât know the floods would get worse) shock response that was called for? What could have been done better? And did I miss it, or has a similar opportunity gone begging with the Polar Vortex in the US? How about:

superstorm Sandy. Where was the concerted, pre-planned (itâs not as if we didnât know the floods would get worse) shock response that was called for? What could have been done better? And did I miss it, or has a similar opportunity gone begging with the Polar Vortex in the US? How about:

-Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â A climate summit/tribunal, pulling together academics, religious organizations, local governments etc etc to review the evidence

-Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Parliamentary hearings, eg Select Committee enquiries into the causes of the floods

-Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Putting together coalitions of unusual suspects to raise the issuesâ public profile (eg bishops and reinsurers)

-Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Did the various research outfits with prior work on this drop everything and repackage that work with links to the floods?

Overall, the level of response feels far weaker than that before the Copenhagen Climate Summit back in 2009 â have campaigners have got trapped in a climate diplomacy âland of the linearâ, and lost their ability to seize opportunities like that presented by the flood?

There are other explanations of course. People rightly deplore blatant ambulance chasing and opportunism, but there must be a way to overcome that, e.g. combining climate change discussion with volunteering to help those affected. The obvious response is to wait for a decent interval, but that carries a high price in terms of a lost opportunity to grab the media spotlight for a crucial issue.

Itâs more than likely that a lot of these things did actually happen, and I just missed them â Iâm sure lots of discussions took place among climate change campaigners about how to respond. But if the response had been effective, I wouldnât be writing this post. It may be about scale of response – did campaigners do a few stunts and press releases, but basically carry on as normal, or did they react to the advocacy equivalent of a major humanitarian disaster (think Asian tsunami), and drop all their other plans to focus on this? Would love to hear from those involved about the obstacles they encountered – do we need to rethink the ‘shocks as drivers of change’ hypothesis?

Itâs also perhaps the case that the floods, damaging though they are, have just not been severe enough to unblock the political paralysis (Iâve had similar thoughts on the global financial crisis).

What do you think?

March 27, 2014

Can a Political Economy Approach explain aid donors’ reluctance to think and work politically? Guest post from Neil McCulloch

The more enlightened (in my view) aid types have been wagging their fingers for decades, telling their colleagues to adopt more politically literate approaches to their work. Why isn’t everyone convinced? Neil McCulloch applies a bit of political economy analysis to the aid business.

Over the last fifteen years or more, a new approach to development assistance has been gaining ground in policy circles. Broadly entitled the “political  economy” approach, it attempts to apply a more political approach to understanding development problems and, importantly, development “solutions”. In particular, a central tenet of the approach is that many development problems are fundamentally political rather than technical and that therefore solutions to these problems are most likely to come from inside a country’s polity than from outside. Perhaps the most famous recent example of this line of thinking is Acemoglu and Robinson’s 2012 book Why Nations Fail.

economy” approach, it attempts to apply a more political approach to understanding development problems and, importantly, development “solutions”. In particular, a central tenet of the approach is that many development problems are fundamentally political rather than technical and that therefore solutions to these problems are most likely to come from inside a country’s polity than from outside. Perhaps the most famous recent example of this line of thinking is Acemoglu and Robinson’s 2012 book Why Nations Fail.

Acemoglu and Robinson conclude that if each nation’s fate depends primarily on its domestic political struggles, the role for external development assistance is minimal. However, the response of practitioners to this field is to turn this argument on its head i.e. that is, if indeed each nation’s fate depends primarily on its domestic political struggles, development assistance should be trying to influence these struggles in ways that make pro-development outcomes more likely. Yet despite more than a decade analysis, the political economy “approach” is still rarely used by donors in the field. Why? I think there are four reasons:

It’s too “political”. Perhaps the main reason why political economy approaches are not widely used is the (correct) perception that they are, in some sense, meddling in the politics of the country. Donors presence in a country is at the permission of the host government who, almost by definition, constitute the winning elite of the most recent political struggle within the country. Most governments are generally not sympathetic to the idea of foreign governments funding “political” activities in their countries and, knowing this, most donors emphasise the benign, technical and apolitical nature of their work. This is why the dominant form of political economy work is Political Economy Analysis. Donors like this because it provides them with some insight into the political dynamics of the countries in which they work so that they can assess the risks of their programs failing because they go against the interests of local political actors. Indeed, if it is appears at all, political economy considerations generally only appear in the Risk Assessment section of project concepts and designs.

It spends too little money. Although donors pursue particular development goals within the countries in which they work, they do so by spending public money. In practice, this means that each country is allocated a certain budget and most of the practical activity of donor staff is associated with the mechanics of spending this money in an accountable fashion. Moreover, more “important” countries are allocated larger budgets, in part because the politicians of donor countries use the size of the budget to signal to the government of the country the importance with which their country regards the bilateral relationship. Yet the “political economy approach” to assistance generally entails building networks and facilitating discussions across a range of local actors who then, themselves, push forward reform agendas. This requires a lot of time and effort – but it spends much less money than building schools and hospitals. Indeed it would be almost impossible for donors to spend the sums of money at their disposal simply with a political economy approach and yet scaling back the budget to cover only the amounts necessary would result in a budget for assistance which might be seen as derisory by the host government.

It spends too little money. Although donors pursue particular development goals within the countries in which they work, they do so by spending public money. In practice, this means that each country is allocated a certain budget and most of the practical activity of donor staff is associated with the mechanics of spending this money in an accountable fashion. Moreover, more “important” countries are allocated larger budgets, in part because the politicians of donor countries use the size of the budget to signal to the government of the country the importance with which their country regards the bilateral relationship. Yet the “political economy approach” to assistance generally entails building networks and facilitating discussions across a range of local actors who then, themselves, push forward reform agendas. This requires a lot of time and effort – but it spends much less money than building schools and hospitals. Indeed it would be almost impossible for donors to spend the sums of money at their disposal simply with a political economy approach and yet scaling back the budget to cover only the amounts necessary would result in a budget for assistance which might be seen as derisory by the host government.

It lacks an operational evidence base. A huge amount has been written about the political economy of development. However, the vast majority of it has been descriptive or analytical – very little of it has been operational (an exception is ODI’s work on the political economy of service delivery). Therefore, although there are some promising examples of success (e.g. the Asia Foundation’s approach in the Philippines), there is currently little solid evidence that taking a “political economy approach” actually yields better and more sustainable outcomes than a more traditional approach. The Developmental Leadership Program is currently coordinating a set of case studies which aim to explore precisely this issue; but until we have clear evidence, it is not surprising that many donor staff are cautious about adopting what is seen by some as a risky and unproven approach.

There is no sanction for quiet failure. Donor projects sometimes fail. Most donors put in place a complex architecture of processes to try to minimise the  probability of failure (e.g. rigorous, and lengthy, design processes, regular monitoring and independent evaluations). Yet despite this, it is extremely hard for most donors to determine the extent of success or failure of the portfolio of programs that they fund in a country. In part, this is because measuring success is difficult since the situation if the assistance had not been provided is often unknown. It is also because donor projects are often long (five years or more), whilst the tenure of donor staff in a country is generally short (three years or less), so few staff see projects through the entire cycle. And it is also because it is not possible (and probably not desirable) to have sanctions for failure. Unless projects “blow up”, it is perfectly possible for them to continue for years, delivering “results” by substituting for local capacity without achieving any sustainable change. Without a general sense that projects are failing to deliver sustainable change, there is little pressure for a new approach.

probability of failure (e.g. rigorous, and lengthy, design processes, regular monitoring and independent evaluations). Yet despite this, it is extremely hard for most donors to determine the extent of success or failure of the portfolio of programs that they fund in a country. In part, this is because measuring success is difficult since the situation if the assistance had not been provided is often unknown. It is also because donor projects are often long (five years or more), whilst the tenure of donor staff in a country is generally short (three years or less), so few staff see projects through the entire cycle. And it is also because it is not possible (and probably not desirable) to have sanctions for failure. Unless projects “blow up”, it is perfectly possible for them to continue for years, delivering “results” by substituting for local capacity without achieving any sustainable change. Without a general sense that projects are failing to deliver sustainable change, there is little pressure for a new approach.

It is easy to see that an approach that seeks to tackle an unrecognised failure using a new, labour intensive method with little track record that spends small amounts of money and may get the donor into political hot water is unlikely to be embraced too enthusiastically by the senior management of most donors. Which is a shame – because it should. Contrary to popular belief, Aid has achieved a lot of good in the last 50 years (see Roger Riddell’s nuanced account); but where it has done so, it has often been because it has engaged “politically”, changing the incentives for local actors to deliver sustainable changes in the opportunities for and services to the poor. An approach that subordinates money to a thorough understanding of context and a desire for sustainable results will achieve more in the long-run than the current focus on “delivering” (i.e. buying) results. Sadly, the political economy of donor incentives means that it will probably remain a marginal pursuit.

Can a Political Economy Approach explain aid donorsâ reluctance to think and work politically? Guest post from Neil McCulloch

The more enlightened (in my view) aid types have been wagging their fingers for decades, telling their colleagues to adopt more politically literate approaches to their work. Why isn’t everyone convinced? Neil McCulloch applies a bit of political economy analysis to the aid business.

Over the last fifteen years or more, a new approach to development assistance has been gaining ground in policy circles. Broadly entitled the âpolitical  economyâ approach, it attempts to apply a more political approach to understanding development problems and, importantly, development âsolutionsâ. In particular, a central tenet of the approach is that many development problems are fundamentally political rather than technical and that therefore solutions to these problems are most likely to come from inside a countryâs polity than from outside. Perhaps the most famous recent example of this line of thinking is Acemoglu and Robinsonâs 2012 book Why Nations Fail.

economyâ approach, it attempts to apply a more political approach to understanding development problems and, importantly, development âsolutionsâ. In particular, a central tenet of the approach is that many development problems are fundamentally political rather than technical and that therefore solutions to these problems are most likely to come from inside a countryâs polity than from outside. Perhaps the most famous recent example of this line of thinking is Acemoglu and Robinsonâs 2012 book Why Nations Fail.

Acemoglu and Robinson conclude that if each nationâs fate depends primarily on its domestic political struggles, the role for external development assistance is minimal. However, the response of practitioners to this field is to turn this argument on its head i.e. that is, if indeed each nationâs fate depends primarily on its domestic political struggles, development assistance should be trying to influence these struggles in ways that make pro-development outcomes more likely. Yet despite more than a decade analysis, the political economy âapproachâ is still rarely used by donors in the field. Why? I think there are four reasons:

Itâs too âpoliticalâ. Perhaps the main reason why political economy approaches are not widely used is the (correct) perception that they are, in some sense, meddling in the politics of the country. Donors presence in a country is at the permission of the host government who, almost by definition, constitute the winning elite of the most recent political struggle within the country. Most governments are generally not sympathetic to the idea of foreign governments funding âpoliticalâ activities in their countries and, knowing this, most donors emphasise the benign, technical and apolitical nature of their work. This is why the dominant form of political economy work is Political Economy Analysis. Donors like this because it provides them with some insight into the political dynamics of the countries in which they work so that they can assess the risks of their programs failing because they go against the interests of local political actors. Indeed, if it is appears at all, political economy considerations generally only appear in the Risk Assessment section of project concepts and designs.

It spends too little money. Although donors pursue particular development goals within the countries in which they work, they do so by spending public money. In practice, this means that each country is allocated a certain budget and most of the practical activity of donor staff is associated with the mechanics of spending this money in an accountable fashion. Moreover, more âimportantâ countries are allocated larger budgets, in part because the politicians of donor countries use the size of the budget to signal to the government of the country the importance with which their country regards the bilateral relationship. Yet the âpolitical economy approachâ to assistance generally entails building networks and facilitating discussions across a range of local actors who then, themselves, push forward reform agendas. This requires a lot of time and effort â but it spends much less money than building schools and hospitals. Indeed it would be almost impossible for donors to spend the sums of money at their disposal simply with a political economy approach and yet scaling back the budget to cover only the amounts necessary would result in a budget for assistance which might be seen as derisory by the host government.

It spends too little money. Although donors pursue particular development goals within the countries in which they work, they do so by spending public money. In practice, this means that each country is allocated a certain budget and most of the practical activity of donor staff is associated with the mechanics of spending this money in an accountable fashion. Moreover, more âimportantâ countries are allocated larger budgets, in part because the politicians of donor countries use the size of the budget to signal to the government of the country the importance with which their country regards the bilateral relationship. Yet the âpolitical economy approachâ to assistance generally entails building networks and facilitating discussions across a range of local actors who then, themselves, push forward reform agendas. This requires a lot of time and effort â but it spends much less money than building schools and hospitals. Indeed it would be almost impossible for donors to spend the sums of money at their disposal simply with a political economy approach and yet scaling back the budget to cover only the amounts necessary would result in a budget for assistance which might be seen as derisory by the host government.

It lacks an operational evidence base. A huge amount has been written about the political economy of development. However, the vast majority of it has been descriptive or analytical â very little of it has been operational (an exception is ODIâs work on the political economy of service delivery). Therefore, although there are some promising examples of success (e.g. the Asia Foundationâs approach in the Philippines), there is currently little solid evidence that taking a âpolitical economy approachâ actually yields better and more sustainable outcomes than a more traditional approach. The Developmental Leadership Program is currently coordinating a set of case studies which aim to explore precisely this issue; but until we have clear evidence, it is not surprising that many donor staff are cautious about adopting what is seen by some as a risky and unproven approach.

There is no sanction for quiet failure. Donor projects sometimes fail. Most donors put in place a complex architecture of processes to try to minimise the  probability of failure (e.g. rigorous, and lengthy, design processes, regular monitoring and independent evaluations). Yet despite this, it is extremely hard for most donors to determine the extent of success or failure of the portfolio of programs that they fund in a country. In part, this is because measuring success is difficult since the situation if the assistance had not been provided is often unknown. It is also because donor projects are often long (five years or more), whilst the tenure of donor staff in a country is generally short (three years or less), so few staff see projects through the entire cycle. And it is also because it is not possible (and probably not desirable) to have sanctions for failure. Unless projects âblow upâ, it is perfectly possible for them to continue for years, delivering âresultsâ by substituting for local capacity without achieving any sustainable change. Without a general sense that projects are failing to deliver sustainable change, there is little pressure for a new approach.

probability of failure (e.g. rigorous, and lengthy, design processes, regular monitoring and independent evaluations). Yet despite this, it is extremely hard for most donors to determine the extent of success or failure of the portfolio of programs that they fund in a country. In part, this is because measuring success is difficult since the situation if the assistance had not been provided is often unknown. It is also because donor projects are often long (five years or more), whilst the tenure of donor staff in a country is generally short (three years or less), so few staff see projects through the entire cycle. And it is also because it is not possible (and probably not desirable) to have sanctions for failure. Unless projects âblow upâ, it is perfectly possible for them to continue for years, delivering âresultsâ by substituting for local capacity without achieving any sustainable change. Without a general sense that projects are failing to deliver sustainable change, there is little pressure for a new approach.

It is easy to see that an approach that seeks to tackle an unrecognised failure using a new, labour intensive method with little track record that spends small amounts of money and may get the donor into political hot water is unlikely to be embraced too enthusiastically by the senior management of most donors. Which is a shame â because it should. Contrary to popular belief, Aid has achieved a lot of good in the last 50 years (see Roger Riddellâs nuanced account); but where it has done so, it has often been because it has engaged âpoliticallyâ, changing the incentives for local actors to deliver sustainable changes in the opportunities for and services to the poor. An approach that subordinates money to a thorough understanding of context and a desire for sustainable results will achieve more in the long-run than the current focus on âdeliveringâ (i.e. buying) results. Sadly, the political economy of donor incentives means that it will probably remain a marginal pursuit.

March 26, 2014

Alternatives to Neoliberalism? A retro conversation with the British Left and Ha-Joon Chang

Had a fun and slightly retro evening last week launching âCritique, Influence, Changeâ, a new series of Zed Books (actually new editions of some of their  old books), along with my friend and guru Ha-Joon Chang and Ellie Mae OâHagan, a smart young Guardian columnist/activist in Occupy and UK Uncut. The Zed series includes a new edition of Ha-Joonâs 2004 book Reclaiming Development (with Ilene Grabel).

old books), along with my friend and guru Ha-Joon Chang and Ellie Mae OâHagan, a smart young Guardian columnist/activist in Occupy and UK Uncut. The Zed series includes a new edition of Ha-Joonâs 2004 book Reclaiming Development (with Ilene Grabel).

The topic was âalternatives to neoliberalismâ, hence the retro â havenât heard that phrase for a while. Back in the 1990s, I was writing books on Latin America with whole chapters devoted to the topic. Then, the debate was between alternatives within capitalism, and alternatives outside it. These days, most discussions seem to be happening within the first category (with the notable exception of the whole planetary boundaries/limits to growth debate).

Why? Because it has become increasingly clear that neoliberalism is only one variant of capitalism, and not a very successful one at that. The rise of state capitalism (China), the rediscovery of the need for an activist state (industrial policy) and the spectacular financial crashes of 1998 (Asia) and 2008 (everywhere) means that the old anglo-saxon doctrine of âstate bad, market good and if it moves, deregulate itâ doesnât hold much weight any more.

But as Ellie Mae said, quoting Žižek, âthese days, itâs easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.â In Latin America, there seems to have been lots of progress over the last 20 years in constructing new kinds of politics and social movements, but economic policy ideas donât stretch far beyond resource nationalism (Venezuela, Bolivia) and cautious, market-friendly social democracy (Brazil). In Africa, thereâs been lots of progress on human development, some on governance, but most economies are even more dependent than ever on digging up and exporting everything that lies beneath African soil (and sea). Asia is pursuing various forms of capitalism, but experimenting more with social policy. There are plenty of ideas (eg the âsocial and solidarity economyâ) at local level, but they have not gelled into national alternatives, as far as I can see.

As for Oxfam, we increasingly focus on promoting poor peopleâs âpower in marketsâ, eg supporting women to enter the money economy on better terms, or strengthening producer organizations to get a better deal.

Q&A centred on people lamenting the state of the British Left (or even whether such a thing still exists). Not really my field, but hopefully the much more positive lessons from elsewhere in the world eased their pain. I was particularly struck by a discussion on culture v politics. Culture is a crucial part of building any movement â people come together partly because they find they have things in common in terms of experience (frustration, oppression) and values (faith, purpose). They should celebrate and build on those.

Q&A centred on people lamenting the state of the British Left (or even whether such a thing still exists). Not really my field, but hopefully the much more positive lessons from elsewhere in the world eased their pain. I was particularly struck by a discussion on culture v politics. Culture is a crucial part of building any movement â people come together partly because they find they have things in common in terms of experience (frustration, oppression) and values (faith, purpose). They should celebrate and build on those.

But problems start when that becomes a substitute for political action â politics as lifestyle statement can become hugely self defeating. John OâFarrellâs hilarious book on the British Left under Margaret Thatcher recalls (only half jokingly) a time when even smiling and eating vegetables came to be seen as somehow Tory. We need to have the confidence to talk to, understand, even empathise with people who donât share our values, and build alliances with them. Discomfort is good, circling the wagons around a lifestyle is not. Or as Ellie put it â’Activism fails when it becomes a lifestyle, cloaked in jargon.’

I did my usual thing about how the role of activists is often to clarify a problem to get it on the agenda, rather than delude ourselves that we have the policy solutions to fix it â a good killer fact is worth many unread pages of recommendations, as our recent KFs on inequality demonstrate.

A trade campaigner retorted that itâs pretty weak to go into meetings or press interviews and say âthereâs a problem, but I have no answersâ. What alternatives are there? On trade, Ha-Joon Chang demonstrates one brilliant alternative â the lessons of history. When he wrote Kicking Away the Ladder, the discussion on trade and globalization was largely taking place in a vacuum, dominated by voodoo modelling rather than learning from what successful countries actually did on trade policy. I watched Ha-Joon transform the morale of developing country delegates at the WTO simply by pointing out the extraordinary historical hypocricy of the rich countries (who pioneered industrial policy and protectionism) in telling them to liberalize.

If you want more, check out the collected tweets and pics â the new (and much more accessible) version of minutes.

Stop Press: Prospect Magazine is a World Thinkers’ poll, which includes Ha-Joon – you know what to do.

March 25, 2014

Why the system for managing the world’s food and climate needs to be more like my car

Today, Oxfam is publishing a briefing on its ‘food and climate justice’ campaign. Here’s a post I wrote for the launch.

When I get into my car in London, I step into a system designed to get me safely from A to B. It has seat belts, airbags, and an increasing

Now for food and climate…..

number of electronic warning devices. The traffic system has rules – speed limits, highway codes, traffic lights, enforced by cameras and cops. In countries that have introduced such systems, the result is falling casualty rates, despite rising traffic volumes.

All this effort to ensure a safe traffic system, so you would think that much more elaborate mechanisms would be in place to ensure that the world fulfils the much more elemental task of feeding its people.

You would be wrong. Ahead of next week’s International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) evidence on climate change and global hunger, a new report from Oxfam analyses the state of readiness of the global food system, as it confronts a changing climate, and it arrives at some alarming conclusions.

Already this year there have been a number of record-breaking weather events around the globe, which have badly affected agriculture and the availability and affordability of food. In Brazil, the worst drought in a decade has ruined crops in the country’s breadbasket region – including the valuable coffee harvest, causing the price of coffee to shoot up by 50 per cent. In California the worst drought in over 100 years is hitting the state’s agricultural industry, which produces nearly half of all the vegetables, fruits and nuts grown in the US.

These extreme weather events are in line with what scientists have been telling us to expect from a warming climate. Leaked drafts of the IPCC report conclude that the impact of climate change on global hunger will be worse than previously reported, and severe impacts will be felt in current, not future, generations– in the next 20–30 years in the poorest countries.

These extreme weather events are in line with what scientists have been telling us to expect from a warming climate. Leaked drafts of the IPCC report conclude that the impact of climate change on global hunger will be worse than previously reported, and severe impacts will be felt in current, not future, generations– in the next 20–30 years in the poorest countries.

According to the IPCC, net global agricultural yields are likely to decrease by up to 2% per decade due to climate change, while demand for food (driven by rising affluence and populations) will rise by 14% a decade. It doesn’t take a climate scientist to realize that these numbers don’t add up.

The Oxfam stress test for a ‘hot and hungry’ global food system rates 10 critical areas of national and global food and climate policy: funding for adaptation to climate change (a hot topic in the UK following recent floods); social protection programmes for the most vulnerable groups; humanitarian aid for food crises; food reserves; support for women farmers; public investment in agriculture and related research; crop insurance and weather monitoring.

Across all ten areas, the stress test found a serious gap between what is happening and what is needed. These gaps in preparedness are driven by poverty, power and politics. While many countries – both rich and poor – are inadequately prepared for the impact of climate change on food, it is the world’s poorest and most food insecure countries that are generally the least prepared for and most susceptible to harmful climate change.

But it doesn’t have to be like this. Countries such as Ghana, Viet Nam and Malawi are bucking the trend, enjoying far higher levels of food security than countries such as Nigeria, Laos and Niger, which have similar levels of income and face comparable magnitudes of climate change. A key difference is that Ghana, Viet Nam and Malawi have already taken action on some of the 10 key policy and practice measures highlight in the report.

Oxfam is calling for urgent action by governments, business and individuals to stop climate change making people hungry. This includes building people’s resilience to hunger and climate change, rapidly cutting greenhouse gas emissions, international action on climate change, and political and personal action at an individual level.

It’s a tall order, but the alternative hardly bears thinking about. Unless we act now, we face a species climate crash of horrific proportions.

And here’s the inevitable infographic

Why the system for managing the worldâs food and climate needs to be more like my car

Today, Oxfam is publishing a briefing on its ‘food and climate justice’ campaign. Here’s a post I wrote for the launch.

When I get into my car in London, I step into a system designed to get me safely from A to B. It has seat belts, airbags, and an increasing

Now for food and climate…..

number of electronic warning devices. The traffic system has rules â speed limits, highway codes, traffic lights, enforced by cameras and cops. In countries that have introduced such systems, the result is falling casualty rates, despite rising traffic volumes.

All this effort to ensure a safe traffic system, so you would think that much more elaborate mechanisms would be in place to ensure that the world fulfils the much more elemental task of feeding its people.

You would be wrong. Ahead of next weekâs International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) evidence on climate change and global hunger, a new report from Oxfam analyses the state of readiness of the global food system, as it confronts a changing climate, and it arrives at some alarming conclusions.

Already this year there have been a number of record-breaking weather events around the globe, which have badly affected agriculture and the availability and affordability of food. In Brazil, the worst drought in a decade has ruined crops in the countryâs breadbasket region â including the valuable coffee harvest, causing the price of coffee to shoot up by 50 per cent. In California the worst drought in over 100 years is hitting the stateâs agricultural industry, which produces nearly half of all the vegetables, fruits and nuts grown in the US.

These extreme weather events are in line with what scientists have been telling us to expect from a warming climate. Leaked drafts of the IPCC report conclude that the impact of climate change on global hunger will be worse than previously reported, and severe impacts will be felt in current, not future, generationsâ in the next 20â30 years in the poorest countries.

These extreme weather events are in line with what scientists have been telling us to expect from a warming climate. Leaked drafts of the IPCC report conclude that the impact of climate change on global hunger will be worse than previously reported, and severe impacts will be felt in current, not future, generationsâ in the next 20â30 years in the poorest countries.

According to the IPCC, net global agricultural yields are likely to decrease by up to 2% per decade due to climate change, while demand for food (driven by rising affluence and populations) will rise by 14% a decade. It doesnât take a climate scientist to realize that these numbers donât add up.

The Oxfam stress test for a âhot and hungryâ global food system rates 10 critical areas of national and global food and climate policy: funding for adaptation to climate change (a hot topic in the UK following recent floods); social protection programmes for the most vulnerable groups; humanitarian aid for food crises; food reserves; support for women farmers; public investment in agriculture and related research; crop insurance and weather monitoring.

Across all ten areas, the stress test found a serious gap between what is happening and what is needed. These gaps in preparedness are driven by poverty, power and politics. While many countries â both rich and poor â are inadequately prepared for the impact of climate change on food, it is the worldâs poorest and most food insecure countries that are generally the least prepared for and most susceptible to harmful climate change.

But it doesnât have to be like this. Countries such as Ghana, Viet Nam and Malawi are bucking the trend, enjoying far higher levels of food security than countries such as Nigeria, Laos and Niger, which have similar levels of income and face comparable magnitudes of climate change. A key difference is that Ghana, Viet Nam and Malawi have already taken action on some of the 10 key policy and practice measures highlight in the report.

Oxfam is calling for urgent action by governments, business and individuals to stop climate change making people hungry. This includes building peopleâs resilience to hunger and climate change, rapidly cutting greenhouse gas emissions, international action on climate change, and political and personal action at an individual level.

Itâs a tall order, but the alternative hardly bears thinking about. Unless we act now, we face a species climate crash of horrific proportions.

And here’s the inevitable infographic

March 24, 2014

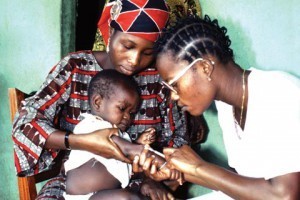

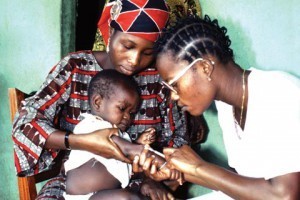

What have we learned on getting public services to poor people? What’s next?

Ten years after the World Development Report 2004, the ODI’s Marta Foresti reflects on the past decade and implications for the  future

future

Why do so many countries still fail to deliver adequate services to their citizens? And why does this problem persist even in countries with rapid economic growth and relatively robust institutions or policies?

This was the problem addressed by the World Bank’s ground-breaking 2004 World Development Report (WDR) Making Services Work for Poor People. At its core was the recognition that politics and accountability are vital to improve services, and that aid donors ignore this at their peril. Ten years on, these issues are still at the heart of the development agenda, as discussed at the anniversary conference organised jointly by ODI and the World Bank in late February.

As much as this was a moment to celebrate the influence of the WDR 2004 on a decade of development thinking and practice, it also highlighted just how far we have to go before every citizen around the world has access to good quality basic services such as education, health, water and electricity.

Let’s begin with what we learned from WDR 2004 and what we know better today as a result of the work of the last ten years. First off is the role of information in improving accountability for service delivery. As Leni Wild suggests in her reflections on the conference, there has been real progress in understanding not only what types of information can be used and by whom, but also in how information can foster accountability. Ten years on, there is widespread agreement that while important, information alone rarely leads to improved services, and a growing awareness that it is incentives that matter if politicians and service providers are to act on information and data. In other words, information is a necessary but not sufficient condition for change.

Let’s begin with what we learned from WDR 2004 and what we know better today as a result of the work of the last ten years. First off is the role of information in improving accountability for service delivery. As Leni Wild suggests in her reflections on the conference, there has been real progress in understanding not only what types of information can be used and by whom, but also in how information can foster accountability. Ten years on, there is widespread agreement that while important, information alone rarely leads to improved services, and a growing awareness that it is incentives that matter if politicians and service providers are to act on information and data. In other words, information is a necessary but not sufficient condition for change.

Related to this, Ruth Levine of the Hewlett Foundation was among those who noted the progress made in the past decade in the research and quality of evidence on service delivery. This is the result, in part, of greater interest and investment in impact evaluation and randomised control trials (RCTs) that provide vital insights on what works to improve services in different contexts and – to a lesser extent – on why. However the mood at the conference was not one of hype around RCTs and other experimental approaches: much as they provide relevant evidence, they fail to explain the complex relationship between contextual factors, institutional arrangements, programmes and their outcomes. Lant Pritchett from CGD summed this up neatly in his blog last November: ‘RCTs are one hammer in the development toolkit and previously protruding nails were ignored for lack of a hammer, but not every development problem is a nail.’

Shanta Devarajan, Director of the WDR 2004, reminded us of one of its key lessons: that money alone is not enough to fix public service delivery problems and that, by extension, aid plays only a minor role. Countries undergoing fast economic growth, such as Nigeria, still fail to provide access to education to many poor girls and even Brazil – seen as a world leader on improving services to the poor – faces trade-offs between a pro-poor tax system and improved education and health.

Despite the influence of WDR 2004 on development thinking and practice over the past ten years, thorny issues remain that still need attention and, most importantly, far more debate. This will demand open minds and a real desire to break down disciplinary barriers, a step-by-step approach, experimentation with new ideas, and a willingness to acknowledge and learn from failure.

The first thorny issue is the role of the private sector in delivering services, which was a much debated theme: the evidence may show promising results and outcomes, but can we really expect the private sector to substitute for improved public institutions? And what are the implications for the long-term sustainability of services for the poor? Most importantly, where states are weak, their markets are also often weak, casting doubt on the notion of markets as a short cut to accountability. Public and private provision is not a matter of ‘either/or’: they are inter-related and this close relationship requires more analysis.

promising results and outcomes, but can we really expect the private sector to substitute for improved public institutions? And what are the implications for the long-term sustainability of services for the poor? Most importantly, where states are weak, their markets are also often weak, casting doubt on the notion of markets as a short cut to accountability. Public and private provision is not a matter of ‘either/or’: they are inter-related and this close relationship requires more analysis.

Lant Pritchett put forward the second challenge for the next ten years: public services should be for all, the poor, of course, but also the middle classes. When service delivery is abysmal right across the social spectrum, the focus on the poor might miss important opportunities to identify a significant and powerful constituency for change amongst the ‘elites’.

The third thorny issue is human behaviour and all the assumptions that surround it. The forthcoming WDR 2015, Mind and Culture, focuses on social norms and behaviour and there is much expectation that behavioural economics (which, as Ruth Levine reminded us, used to be called psychology) will shed some light on our preconceptions about how we attempt to induce better behaviour among politicians, as well as service providers and ourselves.

But I am not convinced that this alone will get us to the root of how political incentives work, let alone broader questions about risk-taking individuals and their chances of thriving in fundamentally risk-averse bureaucracies. We need to look at the role of social and political organisation, and in particular the kind of organisation that permits collective action to unblock processes of reform and change.

Which leads me to my final – and most important – point: the politics of it all. The conference ended with a clear indication of what the future holds: politics is not only part of the problem, but also of the solution. Working around politics rather than with it does not work: meaningful education reform cannot happen despite teachers’ unions, but in negotiation with them. Equally, efforts to stimulate the voice of citizens and their demand for services only work when they are met with equal efforts to better understand the incentives and decision-making logic of the politicians and civil servants responsible for the delivery of those services. As Alison Evans put it, via Michael Rosen’s iconic bear hunt: ‘We can’t go over it, We can’t go under it; Oh no, we have to go through it’

Which leads me to my final – and most important – point: the politics of it all. The conference ended with a clear indication of what the future holds: politics is not only part of the problem, but also of the solution. Working around politics rather than with it does not work: meaningful education reform cannot happen despite teachers’ unions, but in negotiation with them. Equally, efforts to stimulate the voice of citizens and their demand for services only work when they are met with equal efforts to better understand the incentives and decision-making logic of the politicians and civil servants responsible for the delivery of those services. As Alison Evans put it, via Michael Rosen’s iconic bear hunt: ‘We can’t go over it, We can’t go under it; Oh no, we have to go through it’

Above all, there is a need for a healthy dose of humility about the role of external actors in what are, fundamentally, domestically driven political processes.

What have we learned on getting public services to poor people? Whatâs next?

Ten years after the World Development Report 2004, the ODIâs Marta Foresti reflects on the past decade and implications for the  future

future

Why do so many countries still fail to deliver adequate services to their citizens? And why does this problem persist even in countries with rapid economic growth and relatively robust institutions or policies?

This was the problem addressed by the World Bankâs ground-breaking 2004 World Development Report (WDR) Making Services Work for Poor People. At its core was the recognition that politics and accountability are vital to improve services, and that aid donors ignore this at their peril. Ten years on, these issues are still at the heart of the development agenda, as discussed at the anniversary conference organised jointly by ODI and the World Bank in late February.

As much as this was a moment to celebrate the influence of the WDR 2004 on a decade of development thinking and practice, it also highlighted just how far we have to go before every citizen around the world has access to good quality basic services such as education, health, water and electricity.

Letâs begin with what we learned from WDR 2004 and what we know better today as a result of the work of the last ten years. First off is the role of information in improving accountability for service delivery. As Leni Wild suggests in her reflections on the conference, there has been real progress in understanding not only what types of information can be used and by whom, but also in how information can foster accountability. Ten years on, there is widespread agreement that while important, information alone rarely leads to improved services, and a growing awareness that it is incentives that matter if politicians and service providers are to act on information and data. In other words, information is a necessary but not sufficient condition for change.

Letâs begin with what we learned from WDR 2004 and what we know better today as a result of the work of the last ten years. First off is the role of information in improving accountability for service delivery. As Leni Wild suggests in her reflections on the conference, there has been real progress in understanding not only what types of information can be used and by whom, but also in how information can foster accountability. Ten years on, there is widespread agreement that while important, information alone rarely leads to improved services, and a growing awareness that it is incentives that matter if politicians and service providers are to act on information and data. In other words, information is a necessary but not sufficient condition for change.

Related to this, Ruth Levine of the Hewlett Foundation was among those who noted the progress made in the past decade in the research and quality of evidence on service delivery. This is the result, in part, of greater interest and investment in impact evaluation and randomised control trials (RCTs) that provide vital insights on what works to improve services in different contexts and â to a lesser extent â on why. However the mood at the conference was not one of hype around RCTs and other experimental approaches: much as they provide relevant evidence, they fail to explain the complex relationship between contextual factors, institutional arrangements, programmes and their outcomes. Lant Pritchett from CGD summed this up neatly in his blog last November: âRCTs are one hammer in the development toolkit and previously protruding nails were ignored for lack of a hammer, but not every development problem is a nail.â

Shanta Devarajan, Director of the WDR 2004, reminded us of one of its key lessons: that money alone is not enough to fix public service delivery problems and that, by extension, aid plays only a minor role. Countries undergoing fast economic growth, such as Nigeria, still fail to provide access to education to many poor girls and even Brazil â seen as a world leader on improving services to the poor â faces trade-offs between a pro-poor tax system and improved education and health.

Despite the influence of WDR 2004 on development thinking and practice over the past ten years, thorny issues remain that still need attention and, most importantly, far more debate. This will demand open minds and a real desire to break down disciplinary barriers, a step-by-step approach, experimentation with new ideas, and a willingness to acknowledge and learn from failure.

The first thorny issue is the role of the private sector in delivering services, which was a much debated theme: the evidence may show promising results and outcomes, but can we really expect the private sector to substitute for improved public institutions? And what are the implications for the long-term sustainability of services for the poor? Most importantly, where states are weak, their markets are also often weak, casting doubt on the notion of markets as a short cut to accountability. Public and private provision is not a matter of âeither/orâ: they are inter-related and this close relationship requires more analysis.

promising results and outcomes, but can we really expect the private sector to substitute for improved public institutions? And what are the implications for the long-term sustainability of services for the poor? Most importantly, where states are weak, their markets are also often weak, casting doubt on the notion of markets as a short cut to accountability. Public and private provision is not a matter of âeither/orâ: they are inter-related and this close relationship requires more analysis.

Lant Pritchett put forward the second challenge for the next ten years: public services should be for all, the poor, of course, but also the middle classes. When service delivery is abysmal right across the social spectrum, the focus on the poor might miss important opportunities to identify a significant and powerful constituency for change amongst the âelitesâ.

The third thorny issue is human behaviour and all the assumptions that surround it. The forthcoming WDR 2015, Mind and Culture, focuses on social norms and behaviour and there is much expectation that behavioural economics (which, as Ruth Levine reminded us, used to be called psychology) will shed some light on our preconceptions about how we attempt to induce better behaviour among politicians, as well as service providers and ourselves.

But I am not convinced that this alone will get us to the root of how political incentives work, let alone broader questions about risk-taking individuals and their chances of thriving in fundamentally risk-averse bureaucracies. We need to look at the role of social and political organisation, and in particular the kind of organisation that permits collective action to unblock processes of reform and change.

Which leads me to my final â and most important â point:  the politics of it all. The conference ended with a clear indication of what the future holds: politics is not only part of the problem, but also of the solution. Working around politics rather than with it does not work: meaningful education reform cannot happen despite teachersâ unions, but in negotiation with them. Equally, efforts to stimulate the voice of citizens and their demand for services only work when they are met with equal efforts to better understand the incentives and decision-making logic of the politicians and civil servants responsible for the delivery of those services. As Alison Evans put it, via Michael Rosenâs iconic bear hunt: âWe canât go over it, We canât go under it; Oh no, we have to go through itâ

Which leads me to my final â and most important â point: Â the politics of it all. The conference ended with a clear indication of what the future holds: politics is not only part of the problem, but also of the solution. Working around politics rather than with it does not work: meaningful education reform cannot happen despite teachersâ unions, but in negotiation with them. Equally, efforts to stimulate the voice of citizens and their demand for services only work when they are met with equal efforts to better understand the incentives and decision-making logic of the politicians and civil servants responsible for the delivery of those services. As Alison Evans put it, via Michael Rosenâs iconic bear hunt: âWe canât go over it, We canât go under it; Oh no, we have to go through itâ

Above all, there is a need for a healthy dose of humility about the role of external actors in what are, fundamentally, domestically driven political processes.

March 21, 2014

Killer factcheck: ‘Women own 2% of land’ = not true. What do we really know about women and land?

Cheryl Doss, a feminist economist at Yale University argues that (as with ‘70% of the world’s poor are women‘ ) we need to stop using the unfounded ‘women own 2% of the world’s  farmland’ stat, and start using some of the real numbers that are emerging (while also demanding much better gender data).

farmland’ stat, and start using some of the real numbers that are emerging (while also demanding much better gender data).

For advocates, nothing is better than having a powerful statistic at your disposal to use in support of a cause. In the world of women’s property rights advocacy, there’s one statistic cited by advocates more than the rest: Women own less than 2 percent of the world’s land. It certainly is a great rallying cry to mobilize people in support of equal land rights.

If only the statistic were true.

Don’t get me wrong – worldwide, women do not own anywhere near the amount of property that men do. But this statistic and its variations, often repeated by women’s rights advocacy groups including Oxfam and Action Aid, is actually unsubstantiated and advocates are doing a disservice to their own cause by using it.

Women’s land rights are critically important. We know that they are correlated with increased empowerment and better outcomes for women and children. When women have a secure claim to land, they are less vulnerable when their husband dies or leaves.

Yet, using unsubstantiated statistics for advocacy is counterproductive. Advocates lose credibility by making claims that are inaccurate and slow down progress towards achieving their goals because without credible data, they also can’t measure changes. As some countries work towards improving women’s property rights, advocates need to be using numbers that reflect these changes – and hold governments accountable where things are static or getting worse. For example, the Demographic and Health Surveys, the leading source of nationally representative data on health and population, now ask women and men (of reproductive age) in ten African countries whether or not they own land. Their data shows a far more complicated and diverse landscape than is reflected by the statistic above.

The percentage of women reporting that they own land ranges from 11% in Senegal to 54% in Rwanda and Burundi. But these numbers must be compared with those for men: The comparable figures for men are 28% in Senegal and 55% in Rwanda and 64% in Burundi. The largest gender gap in land ownership is in Uganda, where the share of men who own land is 21 percentage points higher than that for women. The gender gaps are much larger if we consider only land that is owned solely (individually), by a man or woman, rather than include both sole and joint land ownership. By having a more accurate picture of where women have more or less property rights, advocates can more effectively leverage their resources to achieve their goals.

The percentage of women reporting that they own land ranges from 11% in Senegal to 54% in Rwanda and Burundi. But these numbers must be compared with those for men: The comparable figures for men are 28% in Senegal and 55% in Rwanda and 64% in Burundi. The largest gender gap in land ownership is in Uganda, where the share of men who own land is 21 percentage points higher than that for women. The gender gaps are much larger if we consider only land that is owned solely (individually), by a man or woman, rather than include both sole and joint land ownership. By having a more accurate picture of where women have more or less property rights, advocates can more effectively leverage their resources to achieve their goals.

Percentage of Women and Men (of reproductive age) Who Own Land

Country (year)

Household

Women

Men

% of households owning any agricultural land

% who own any land

(sole or joint)

% who own any land

(sole only)

% who own any land

(sole or joint)

% who any land (sole only)

Burkina Faso (2010)

79

32

12

54

43

Burundi (2010)

86

54

11

64

50

Ethiopia (2011)

73

50

12

54

28

Lesotho (2009)

53

38

7

34

9

Malawi (2010)

80

48

23

NA

NA

Rwanda (2010)

81

54

13

55

25

Senegal (2010–11)

47

11

5

28

22

Tanzania (2010)

77

30

8

NA

NA

Uganda (2011)

72

39

14

60

46

Zimbabwe (2010–11)

63

36

11

36

22

Source: DHS data compiled in Doss et al.

The good news is that data is slowly becoming available. In a recent paper that I coauthored, we use data from several new sources to examine the issue of women’s land ownership. In addition, to the DHS data that we compiled above and that from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s women’s land rights database, we use the recent Living Standards Measurement Studies Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA). While the DHS data tells us the percentage of women and men who own land, the LSMS-ISA surveys provide plot level data on ownership and management for six countries in Africa. These surveys allow us to analyze what share of land is owned by women. These are two very different perspectives on women’s land ownership, but they tell similar stories.

The plot level data allows us to consider whether land is owned by men, women, or jointly by men and women. In all six countries, women own less land than men, but the patterns differ across countries and vary depending on the definition of ownership that is used.

These new data sources point to key issues that need to be addressed, including the importance of defining whether we are interested in statistics on women (i.e. what percentage of women own land) or on land (i.e. what percentage of land is owned by women). They also point to the importance of considering both sole and joint ownership.

As next steps, we can do two things. First, we can stop using statistics that are unsubstantiated, even if they convey an important  truth. Women do own less land than men – and we can provide more details for some countries. But we don’t have a global figure.

truth. Women do own less land than men – and we can provide more details for some countries. But we don’t have a global figure.

So, what can we say? The best approach is to make a general claim and then provide numbers on a specific country or region for which data is available. Here’s some possibilities:

Globally, more men than women own land. On average, across 10 countries in Africa, 39% of women and 48% of men report owning land, including both individual and joint ownership. Only 12% of women report owning land individually, while 31% of men do so. (note that these data only include men and women of reproductive age.)

More of the privately owned land is reported as being owned by men than by women. In Niger, only 9% of the land is reported as owned by women, 29% jointly by men and women and 62% by men. In Tanzania, only 16% of the land is reported as owned by women, 39% jointly by men and women and 48% by men. In Ethiopia, 15% of the documented land ownership is reported as owned by women, 39% by men and women jointly, and 45% by men.

Second, we can advocate for better data. In surveys that ask, “Does anyone in the household own any land?” a follow up question that asks “Who owns the land?” would allow us to exponentially increase our understanding of the gendered patterns of land ownership. Yes, we need to consider the local context and what is meant by ownership; but this simple first step will go a long way toward providing an accurate statistic advocates can use to strengthen women’s land rights.

Cheryl Doss is a Senior Lecturer in African Studies and Economics at Yale University and a Public Voices Fellow at The Op-Ed Project.

From Duncan: Anyone know the origins of the 2% figure? Always instructive to track down the origins of these stats. Also, here’s a nice 2 minute video for International Women’s Day with (I think) some more reliable gender inequality stats (h/t Richard King).

Killer factcheck: âWomen own 2% of landâ = not true. What do we really know about women and land?

Cheryl Doss, a feminist economist at Yale University argues that (as with ‘70% of the world’s poor are women‘ ) we need to stop using the unfounded ‘women own 2% of the world’s  farmland’ stat, and start using some of the real numbers that are emerging (while also demanding much better gender data).

farmland’ stat, and start using some of the real numbers that are emerging (while also demanding much better gender data).

For advocates, nothing is better than having a powerful statistic at your disposal to use in support of a cause. In the world of women’s property rights advocacy, there’s one statistic cited by advocates more than the rest: Women own less than 2 percent of the world’s land. It certainly is a great rallying cry to mobilize people in support of equal land rights.

If only the statistic were true.

Don’t get me wrong – worldwide, women do not own anywhere near the amount of property that men do. But this statistic and its variations, often repeated by women’s rights advocacy groups including Oxfam and Action Aid, is actually unsubstantiated and advocates are doing a disservice to their own cause by using it.

Women’s land rights are critically important. We know that they are correlated with increased empowerment and better outcomes for women and children. When women have a secure claim to land, they are less vulnerable when their husband dies or leaves.

Yet, using unsubstantiated statistics for advocacy is counterproductive. Advocates lose credibility by making claims that are inaccurate and slow down progress towards achieving their goals because without credible data, they also can’t measure changes. As some countries work towards improving women’s property rights, advocates need to be using numbers that reflect these changes – and hold governments accountable where things are static or getting worse. For example, the Demographic and Health Surveys, the leading source of nationally representative data on health and population, now ask women and men (of reproductive age) in ten African countries whether or not they own land. Their data shows a far more complicated and diverse landscape than is reflected by the statistic above.

The percentage of women reporting that they own land ranges from 11% in Senegal to 54% in Rwanda and Burundi. But these numbers must be compared with those for men: The comparable figures for men are 28% in Senegal and 55% in Rwanda and 64% in Burundi. The largest gender gap in land ownership is in Uganda, where the share of men who own land is 21 percentage points higher than that for women. The gender gaps are much larger if we consider only land that is owned solely (individually), by a man or woman, rather than include both sole and joint land ownership. By having a more accurate picture of where women have more or less property rights, advocates can more effectively leverage their resources to achieve their goals.

The percentage of women reporting that they own land ranges from 11% in Senegal to 54% in Rwanda and Burundi. But these numbers must be compared with those for men: The comparable figures for men are 28% in Senegal and 55% in Rwanda and 64% in Burundi. The largest gender gap in land ownership is in Uganda, where the share of men who own land is 21 percentage points higher than that for women. The gender gaps are much larger if we consider only land that is owned solely (individually), by a man or woman, rather than include both sole and joint land ownership. By having a more accurate picture of where women have more or less property rights, advocates can more effectively leverage their resources to achieve their goals.

Percentage of Women and Men (of reproductive age) Who Own Land

Country (year)

Household

Women

Men

% of households owning any agricultural land

% who own any land

(sole or joint)

% who own any land

(sole only)

% who own any land

(sole or joint)

% who any land (sole only)

Burkina Faso (2010)

79

32

12

54

43

Burundi (2010)

86

54

11

64

50

Ethiopia (2011)

73

50

12

54

28

Lesotho (2009)

53

38

7

34

9

Malawi (2010)

80

48

23

NA

NA

Rwanda (2010)

81

54

13

55

25

Senegal (2010–11)

47

11

5

28

22

Tanzania (2010)

77

30

8

NA

NA

Uganda (2011)

72

39

14

60

46

Zimbabwe (2010–11)

63

36

11

36

22

Source: DHS data compiled in Doss et al.

The good news is that data is slowly becoming available. In a recent paper that I coauthored, we use data from several new sources to examine the issue of women’s land ownership. In addition, to the DHS data that we compiled above and that from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s women’s land rights database, we use the recent Living Standards Measurement Studies Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA). While the DHS data tells us the percentage of women and men who own land, the LSMS-ISA surveys provide plot level data on ownership and management for six countries in Africa. These surveys allow us to analyze what share of land is owned by women. These are two very different perspectives on women’s land ownership, but they tell similar stories.

The plot level data allows us to consider whether land is owned by men, women, or jointly by men and women. In all six countries, women own less land than men, but the patterns differ across countries and vary depending on the definition of ownership that is used.

These new data sources point to key issues that need to be addressed, including the importance of defining whether we are interested in statistics on women (i.e. what percentage of women own land) or on land (i.e. what percentage of land is owned by women). They also point to the importance of considering both sole and joint ownership.

As next steps, we can do two things. First, we can stop using statistics that are unsubstantiated, even if they convey an important  truth. Women do own less land than men – and we can provide more details for some countries. But we don’t have a global figure.

truth. Women do own less land than men – and we can provide more details for some countries. But we don’t have a global figure.

So, what can we say? The best approach is to make a general claim and then provide numbers on a specific country or region for which data is available. Here’s some possibilities:

Globally, more men than women own land. On average, across 10 countries in Africa, 39% of women and 48% of men report owning land, including both individual and joint ownership. Only 12% of women report owning land individually, while 31% of men do so. (note that these data only include men and women of reproductive age.)

More of the privately owned land is reported as being owned by men than by women. In Niger, only 9% of the land is reported as owned by women, 29% jointly by men and women and 62% by men. In Tanzania, only 16% of the land is reported as owned by women, 39% jointly by men and women and 48% by men. In Ethiopia, 15% of the documented land ownership is reported as owned by women, 39% by men and women jointly, and 45% by men.

Second, we can advocate for better data. In surveys that ask, “Does anyone in the household own any land?” a follow up question that asks “Who owns the land?” would allow us to exponentially increase our understanding of the gendered patterns of land ownership. Yes, we need to consider the local context and what is meant by ownership; but this simple first step will go a long way toward providing an accurate statistic advocates can use to strengthen women’s land rights.

Cheryl Doss is a Senior Lecturer in African Studies and Economics at Yale University and a Public Voices Fellow at The Op-Ed Project.

From Duncan: Anyone know the origins of the 2% figure? Always instructive to track down the origins of these stats. Also, here’s a nice 2 minute video for International Women’s Day with (I think) some more reliable gender inequality stats (h/t Richard King).

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers