Duncan Green's Blog, page 189

May 12, 2014

How can aid agencies help citizens reduce risks and fight for their rights in the middle of a war zone? Draft paper for your comments

Over the next few weeks, I will be picking your brains on the drafts of a series of case studies I’ve been working on. These draw from Oxfam’s experience of promoting ‘active citizenship’, broadly defined, and examine the theory of change, results, wider lessons etc. The final studies will be published later this year, after incorporating feedback. After the fantastic response to last week’s post on Ben Ramalingam’s draft complexity paper, I’ve got high hopes for this form of unpaid consultancy crowd-sourcing.

First up, some really interesting work in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which offers important lessons for how to promote active citizenship in chaotic and conflict-prone environments. The draft paper (12 pages) is here (DRC final draft April 14), and I would really welcome comments. Here’s a summary:

The work is based on Community Protection Committees (CPCs), made up of six men and six women elected by their communities. A “Women’s Forum”  is also established to focus on protection issues that particularly affect women. In addition, “Change Agents” are elected from further remote villages or locations, in order to expand the geographical impact of the CPC’s work.

is also established to focus on protection issues that particularly affect women. In addition, “Change Agents” are elected from further remote villages or locations, in order to expand the geographical impact of the CPC’s work.

Oxfam and partner staff support these groups to help conflict-affected communities identify the main threats they face, and the actions they can take to mitigate them. They facilitate links with local authorities, and provide training to civilians and authorities on legal standards and laws relating to protection issues, as well as providing orientation to service providers.

There are many similarities in how men and women assess their overall insecurity, but the causes of insecurity and the type of threats they face – abduction, murder, arbitrary arrest, sexual violence, illegal checkpoints, forced labour – are often different.

Men are more at risk of being killed, tortured or abducted, used for forced labour, or imprisoned. We are frequently told that women are less likely than men to be abducted or killed when they go to the fields, but they are at high risk of rape – which often leads to rejection by their husbands.

The impacts of such protection programmes are hard to measure due to the multiple factors affecting the situation and the difficulty in identifying any form of causal chain. However, feedback from communities, including statistical data, has identified some tangible positive changes.

Some stories:

In the Kivus, a number of committees said their main concern was the illegal roadblocks, where illegal ‘taxes’ to pass are demanded, men experience physical assault and women risk assault or rape. One protection committee negotiated the removal of 5 out of 7 of these checkpoints.

In the Hauts Plateaux of Uvira, people reported that there had been an increase in girls enrolling in school following awareness raising on women’s rights by local protection structures, and that they were treated more equally to boys. A woman’s group described how their confidence to mediate had reduced domestic violence: ‘If there are problems in the home, we go and get one or two men who are better behaved, who understand how to live with a woman. And the men talk to the husband while we talk to the wife, to sensitise them both.’

Theory of Change: The core hypothesis underpinning the programme is that citizen action can improve men and women’s situation, specifically through improving accountability even in unpredictable and dangerous contexts such as those in eastern DRC. However, the thinking goes further in two important directions. Firstly, the project is clear that ‘gender’ is not synonymous with ‘women’: empowering women means including and empowering men too.

Secondly, explicitly building the social contract between citizen and state in such high risk environments cannot be done through confrontation, which would carry unacceptably high risks for activists. Instead, the project suggests different approaches to cooperation. For instance, when a local State representative was exploiting displaced people (IDPs) to dig latrines or work the fields without pay, the local CPC invited him to meetings alongside IDP representatives, so that they could get used to talking directly with one another, and held a training session for both (plus members of the local community) on the guiding principles on the protection of IDPs. The training was a way of getting the message across without the local official losing face.

Secondly, explicitly building the social contract between citizen and state in such high risk environments cannot be done through confrontation, which would carry unacceptably high risks for activists. Instead, the project suggests different approaches to cooperation. For instance, when a local State representative was exploiting displaced people (IDPs) to dig latrines or work the fields without pay, the local CPC invited him to meetings alongside IDP representatives, so that they could get used to talking directly with one another, and held a training session for both (plus members of the local community) on the guiding principles on the protection of IDPs. The training was a way of getting the message across without the local official losing face.

What is interesting is that this approach, which could be criticized as naive or over-optimistic, has produced results.

Wider Lessons?

Programmes for Complex Systems: The programme’s design allows it to adapt to a highly fluid and unpredictable environment – in other words, a complex system. According to Richard Nunn, Oxfam’s regional protection adviser, ‘It’s an approach, rather than a prescribed programme, so allows communities to adapt to events – it focuses on shifting local dynamics and feeds off that. It builds adaptive capacity, much like climate change adaptation work.’

By not tying the project to a clear “sector”, the programme was able to be flexible and adapt to fit the context, guided by what people said worked. By cultivating a culture of dialogue as opposed to confrontation, both sides have begun to understand one another, finding ways to generate solutions together. In chaotic and complex environments, working on relationships may be more feasible than trying to target specific outcomes.

A programme can only respond in this way if it promotes continuous self-reflection among programme and partner staff and encourages constructive criticism, leading to a series of adaptive course corrections in response to the shifting tides of violence and politics..

Local Partners and Staff: The gains made by the project depend very significantly on community ownership and local authority acceptance of its content and action. The single most important factor in this is probably having local partners and staff who are fully engaged with communities. Community membership has shown itself to be of much greater benefit here than legal knowledge or qualifications.

Other key success factors include

• Acknowledging the abuses and violence perpetrated against men as well as women, their specific needs for care and support, and the positive role they play in supporting and representing their communities.

• Establishing a strong women’s forum that provides a safe space for women to discuss problems, and where they can gain confidence in a supportive environment.

• Promoting discussion about how rape and other forms of sexual and gender-based violence affect whole communities.

• Developing a code of conduct for each committee and thereby creating a safe space for men and women to discuss gender issues together.

• The community-led nature of the programme allows men and women to address immediate, short-term protection needs as a priority, but also longer-term barriers to women’s rights and without these being seen as a threat to men.

• Celebrating ‘small victories’ that are, after all, significant and life-changing for the individual (or individuals) involved.

Does this make sense? What more did you want to know? What’s missing? Over to you.

May 11, 2014

The return of ‘Links I liked’ – do you want a weekly round up?

I gave up doing ‘links I liked’ roundups when I went on twitter, thinking that they had become redundant. But a few people have suggested reinstating them, either because (shockingly) they haven’t yet joined the twitterati, or because they miss things in the twitterstream. So here are some of the best of last week’s tweeted links – want me to continue the exercise?

Harvard’s Ricardo Hausman on why technology doesn’t diffuse – not bad institutions, but the nature of technology itself

Aren’t stats silly sometimes? The World Bank’s new calculation of national GDP adjusted for local price levels magically reduced global absolute poverty  by half last Tuesday (from 20% to 9%, according to calculations by CGD). Unfortunately, poor people won’t have noticed any difference…..

by half last Tuesday (from 20% to 9%, according to calculations by CGD). Unfortunately, poor people won’t have noticed any difference…..

The aid business has acquired its very own satirical online magazine. Check out the first edition of DevBalls, with DFID in the crosshairs.

Rwanda tops the league for women in parliament (51 out of 80 seats, the only country over 50%) and Africa has 4 in top 10. UK ranks 65th [h/t John Burton]

Great news. Yemen to vote on comprehensive Child Rights Act banning child marriage and female genital mutilation

31 stereotype maps - ‘Africa according to Americans’ etc. Something for everyone in this lot [h/t Irungu Houghton]

‘The Most Important “Sexy” Model Video Ever’. Not sure what to make of this disturbing, provocative (both senses) video from Save the Kids. What do you think – clever? Bad taste? Both?

May 8, 2014

Reformers v lobbyists: where have we got to on tackling corporate tax dodging?

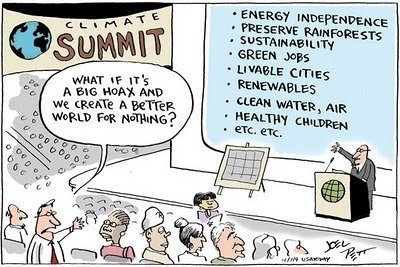

The rhythm of NGO advocacy and campaigning sometimes makes it particularly hard to work on complicated issues, involving drawn-out negotiations where bad guys have more resources and staying power than we do. Campaigns on trade, climate change, debt relief etc often follow a similar trajectory – a big NGO splash as a new issue breaks, then activists realize they need to go back to school (I remember getting briefings on bond contracts during the 1998 Asia financial crisis) or employ new kinds of specialists who can talk the new talk. And then for a while we get geeky, entering into the detail of international negotiations, debating with lobbyists and academics. When it works (as in the debt campaign), we contribute to remarkable victories or to stopping bad stuff happening (which I would argue was a big civil society contribution at the WTO).

But citizen activism has always been characterized by spikes of activity, rather than the steady, long term grind of states and business lobbyists. As an  issue moves down the policy funnel (see pic), the technical content gets greater, and the chance to mobilize the public declines. It becomes harder for NGOs to maintain commitment with new issues appearing, and all the other competing priorities. Sometimes we spin off smaller specialist organizations who can dig in for the long term (like the Bretton Woods Project); at other times we just let things slip.

issue moves down the policy funnel (see pic), the technical content gets greater, and the chance to mobilize the public declines. It becomes harder for NGOs to maintain commitment with new issues appearing, and all the other competing priorities. Sometimes we spin off smaller specialist organizations who can dig in for the long term (like the Bretton Woods Project); at other times we just let things slip.

I thought of this when reading an excellent new Oxfam paper on corporate tax dodging, by Claire Godfrey. It’s both a handy, non-technical overview of how tax dodging affects poor countries, and a laudable effort to keep up the pressure for reform as the memories of the global financial crisis fade, and the lobbyists mobilise to try and stop the OECD and G20 from turning post-crisis promises into something more concrete.

First the issue:

‘The OECD has found that multi-national corporations pay as little as 5 percent in corporate tax, while small companies pay as much as 30 percent. This  situation can mostly be explained by two phenomena: multinational business shifting profits or otherwise structuring cross-border transactions to avoid their tax liabilities; and companies securing tax incentives from governments bidding to attract foreign investment. The tax gap for developing countries – the amount of unpaid tax liability faced by companies – is estimated at $104bn every year (including profits shifted in and out of tax havens). Governments in these countries then give away an estimated $138bn each year in statutory corporate income tax exemptions.’

situation can mostly be explained by two phenomena: multinational business shifting profits or otherwise structuring cross-border transactions to avoid their tax liabilities; and companies securing tax incentives from governments bidding to attract foreign investment. The tax gap for developing countries – the amount of unpaid tax liability faced by companies – is estimated at $104bn every year (including profits shifted in and out of tax havens). Governments in these countries then give away an estimated $138bn each year in statutory corporate income tax exemptions.’

Now the response:

‘The ‘Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting’ (BEPS) proposed by the OECD and approved by the G20 seeks to redefine international tax rules to curb profit shifting activity [by companies], and ensure they pay taxes where the economic activity takes place and value is created. The action plan should be ready for implementation by the end of 2015.

However, there are several reasons why this process, in its current state, will not deliver an outcome that leads to more progressive tax systems worldwide where multinational companies pay their fair share of tax or do so where the value is generated.

Firstly, the business lobby currently has a disproportionate influence on the process, which it uses to protect its interests. Correcting the rules that allow the tax dodging practices of global giants like Google, Starbucks and others that lead to tax revenue losses in OECD countries will be difficult, given the size of the corporate lobby. But worse, perhaps, is that the interests of non-OECD/G20 countries are not represented at all in these negotiations.’

The paper highlights the skewed nature of policy formulation – when the OECD ran a public consultation on its draft rules to curb tax abuses, ‘almost 87 percent of the contributions have come from the business sector, none from developing countries’ tax authorities, and the remaining 13 percent include contributions from NGOs (eight, including Oxfam), academics (seven), experts related to tax administrations (two) and one trade union. More striking, of 135 contributions in total, 130 come from rich countries.’

The paper highlights the skewed nature of policy formulation – when the OECD ran a public consultation on its draft rules to curb tax abuses, ‘almost 87 percent of the contributions have come from the business sector, none from developing countries’ tax authorities, and the remaining 13 percent include contributions from NGOs (eight, including Oxfam), academics (seven), experts related to tax administrations (two) and one trade union. More striking, of 135 contributions in total, 130 come from rich countries.’

The paper concludes that the only way to avoid the lobbyists and the race to the bottom between governments is to create a World Tax Authority, (something Vito Tanzi, former Director of the Fiscal Affairs Department at the IMF, proposed after the Asia Crisis). NGOs are always calling for new international bodies to be set up, but it feels like the case for this one is unusually strong, and the political economy arguments for governments might be persuasive (if they can just shake off the malign influence of the financial lobbyists) – in the end, all governments (as well as their citizens, of course) lose out from a race to the bottom on tax.

May 7, 2014

Top new African Progress Report focusses on farms, fisheries and finance

The Africa Progress Panel (a group of the great and good, chaired by Kofi Annan) launches its 2014 Africa Progress Report today. It’s an excellent, and very nicely written (heartfelt thanks) overview of some key areas: agriculture, fisheries and finance. Some highlights:

very nicely written (heartfelt thanks) overview of some key areas: agriculture, fisheries and finance. Some highlights:

‘For more than a decade, Africa’s economies have been doing well, according to graphs that chart the growth of GDP, exports and foreign investment. The experience of Africa’s people has been more mixed. Viewed from the rural areas and informal settlements that are home to most Africans, the economic recovery looks less impressive. Some – like the artisanal fishermen of West Africa – have been pushed to the brink of destitution. For others, growth has brought extraordinary wealth.

There is much cause for optimism. Demography, globalization, new technologies and changes in the environment for business are combining to create opportunities for development that were absent before the economic recovery. However, optimism should not give way to the exuberance now on display in some quarters. Governments urgently need to make sure that economic growth doesn’t just create wealth for some, but improves wellbeing for the majority. Above all, that means strengthening the focus on Africa’s greatest and most productive assets, the region’s farms and fisheries. This report calls for more effective protection, management and mobilization of the continent’s vast ocean and forest resources. This protection is needed to support transformative growth.

The achievements of the past decade and a half should not be understated. Economic growth has increased average incomes by around one-third. On the current growth trajectory, incomes will double over the next 22 years. Once synonymous with macroeconomic mismanagement and economic stagnation, Africa now hosts some of the world’s fastest-growing economies. Contrary to a widespread misperception, there is more to the growth record than oil and minerals – and more than exports and foreign investment. African business groups have emerged as a powerful force for change in their own right, in areas such as banking, agro-processing, telecommunications and construction.

The achievements of the past decade and a half should not be understated. Economic growth has increased average incomes by around one-third. On the current growth trajectory, incomes will double over the next 22 years. Once synonymous with macroeconomic mismanagement and economic stagnation, Africa now hosts some of the world’s fastest-growing economies. Contrary to a widespread misperception, there is more to the growth record than oil and minerals – and more than exports and foreign investment. African business groups have emerged as a powerful force for change in their own right, in areas such as banking, agro-processing, telecommunications and construction.

For the first time in a generation, poverty is falling – but it is falling far too slowly. Why is growth reducing poverty so slowly? Partly because Africa’s poor are very poor: those below the poverty line of US$1.25 a day live on an average of just 70 cents a day (see graph). And partly because high levels of initial inequality mean that it takes a lot of growth to reduce poverty even by a little. Raising the growth trajectory by 2 percentage points per capita and modest redistribution in favour of the poor would get Africa within touching distance of eradicating poverty by 2030 (see below).

Well-designed social protection programmes could play a vital role by protecting vulnerable people against the risks that come with droughts, illness and other shocks. By transferring cash, they can also raise income levels. Experience in other regions – especially Latin America – demonstrates that social protection can simultaneously help to reduce poverty and inequality, and boost growth in agriculture. Yet Africa underinvests in this vital area – and few governments have developed integrated programmes. By contrast, they spend around 3 per cent of GDP on energy subsidies, most of which go to the rich – three times the level of support provided for social protection. It is hard to imagine a more misplaced set of priorities.

If Africa is to develop a more dynamic and inclusive pattern of growth, there is no alternative to a strengthened focus on agriculture. Sub-Saharan Africa is a region of smallholder farmers. Some people mistakenly see that as a source of weakness and inefficiency. We see it as a strength and potential source of growth.

Africa’s farmers have an unrivalled capacity for resilience and innovation. Operating with no fertilizer, pesticide or irrigation on fragile soils in rain-fed areas, usually with little more than a hoe, they have suffered from a combination of neglect and disastrously misplaced development strategies. Few constituencies can have received more bad advice from development partners and governments than African farmers. And few of the world’s farmers are as poorly served by infrastructure, financial systems, scientific innovation or access to markets. The results are reflected in low levels of productivity: cereals yields are well under half the world average.

It is time for African governments and the wider international community to initiate a uniquely African green revolution. We emphasize the word unique. Copying South Asia’s experience and retracing the steps of other regions is not a viable strategy. Agricultural conditions in Africa are different. Yet Africa desperately needs the scientific innovations in drought-resistant seeds, in higher-yielding varieties and in water use, fertilizer and pesticide that helped to transform agriculture in other regions. Returns on investments in these key areas will be diminished if deep-rooted policy failures are not tackled. These range from exorbitant transport costs for farm produce to underinvestment in storage and marketing infrastructure and barriers to intraregional trade.

It is time for African governments and the wider international community to initiate a uniquely African green revolution. We emphasize the word unique. Copying South Asia’s experience and retracing the steps of other regions is not a viable strategy. Agricultural conditions in Africa are different. Yet Africa desperately needs the scientific innovations in drought-resistant seeds, in higher-yielding varieties and in water use, fertilizer and pesticide that helped to transform agriculture in other regions. Returns on investments in these key areas will be diminished if deep-rooted policy failures are not tackled. These range from exorbitant transport costs for farm produce to underinvestment in storage and marketing infrastructure and barriers to intraregional trade.

Harnessing Africa’s resources for African development is another priority. Fisheries and logging show some striking parallels with tax evasion. In each case, Africa is being integrated through trade into markets characterized by high levels of illegal and unregulated activity. In each case resources that should be used for investment in Africa are being plundered through the activities of local elites and foreign investors. And in each case African governments and the wider international community are failing to put in place the multilateral rules needed to combat what is a global collective action problem.

The social, economic and human consequences are devastating. On a conservative estimate, illegal and unregulated fishing costs West Africa alone US$1.3 billion a year. The livelihoods of artisanal fishing people are being destroyed, Africa is losing a vital source of protein and nutrition, and opportunities to enter higher value-added areas of world trade are being lost. Unregistered industrial trawlers and ports at which illegal catches are unloaded are the economic equivalent of mining companies evading taxes and offshore tax havens. The underlying problems are widely recognized. Yet international action to solve those problems has relied on voluntary codes of conduct that are often widely ignored. The same is true of logging activity, with the forests of West and Central Africa established as hot-spots for the plunder of timber resources.’

If you can find the time, do read the rest of the report – it’s really good.

May 6, 2014

Can complex systems thinking provide useful tools for aid workers? Draft paper on some DFID pilot experiments, for your comments

Ben Ramalingam, who wrote last year’s big book on complexity and aid (Aid on the Edge of Chaos) has been doing some interesting work with DFID and wants comment on his draft paper (with Miguel Laric and John Primrose) summarizing the project. The draft is here BestPracticetoBestFitWorkingPaper_DraftforComments_May2014 (just comment on this post, and the authors will read and reply where necessary, and make sure any non-bonkers comments are reflected in the final version).

The project tries to answer a thorny question for complexity wallahs. Can the standard research tools for studying complex systems provide a useful  toolkit for aid agencies, or is that an oxymoron? i.e. is the whole point of complex systems that you can’t have standard approaches, only connected, agile people able to respond and improvise?

toolkit for aid agencies, or is that an oxymoron? i.e. is the whole point of complex systems that you can’t have standard approaches, only connected, agile people able to respond and improvise?

If the answer is ‘oxymoron’, then we may have a problem in terms of thinking about and navigating complexity. But there is an issue if the answer is ‘yes’, as the ‘toolkit temptation’ is deeply rooted in the aid and development sector often unhelpfully, and could lead to unhelpful and damaging ‘complexity silver bullets’ and tick boxes.

Ben and colleagues reckon that this circle can be squared, and that the right complexity toolkit:

‘can help navigate a middle ground in the face of complex problems: to ensure development professionals neither have to surrender to uncertainty on the one hand nor construct convenient but false and potentially unhelpful log-frame ‘fictions’ on the other.’

To explore this, they have been trying out some complexity tools, using various DFID wealth creation programmes as guinea pigs (pilots). The pilots were trade facilitation and girls’ empowerment in Nigeria, private sector development in DRC, and a cross-DFID programme management review.

The Nigerian trade programme gets the most coverage in the paper, and exemplifies some of the issues. The aim of the programme was to improve the volume and value of trade. Trade is a classic complex system, full of feedback loops – e.g. if an activity becomes more profitable, and there are no significant barriers to entry, more entrepreneurs jump in. That means that linear analyses (reduce tariffs by X and trade will rise by Y) are often proved wrong in practice, because they fail to include the effects of feedback. So the researchers built a simulation of the trading system, and used it to run a simulation game for DFID staff to illustrate how tweaking different activities would ripple through the trade system.

Their conclusion?

‘The best way forward, short of trying to analyse and predict the system in advance – which is likely to be impossible, is to employ a portfolio approach: identifying possible entry points for interventions, launching multiple parallel interventions and learn in ‘real time’ to ensure the appropriate sequence and mix of activities. Indeed, the method is designed to support such an evolutionary approach to programming.’

The programme on girls’ empowerment used network analysis tools to explore the range of actors influencing girl power, and the interaction between those actors, producing an improved understanding of the ‘power ecosystem’ at play (the difference with traditional stakeholder mapping is an explicit analysis of the interactions between different stakeholders, rather than mapping them in isolation). The DRC private sector work did something similar. And I must admit I didn’t read the case study on internal DFID process reviews (can anyone blame me for that?!)

The programme on girls’ empowerment used network analysis tools to explore the range of actors influencing girl power, and the interaction between those actors, producing an improved understanding of the ‘power ecosystem’ at play (the difference with traditional stakeholder mapping is an explicit analysis of the interactions between different stakeholders, rather than mapping them in isolation). The DRC private sector work did something similar. And I must admit I didn’t read the case study on internal DFID process reviews (can anyone blame me for that?!)

Across the four pilots, the research arrived at some findings that will ring true with many aid workers:

Lots of DFID staff are already working in ways that fit with a complexity approach, but ‘Examples of flexible and adaptable approaches in DFID were seen to happen despite corporate processes, rather than because of them.’

DFID staff want tools, mentors and permission to experiment.

They also want some way, at corporate level, for senior management to classify the nature of the problem – simple systems where traditional linear approaches are probably OK, or complex systems where they are not. ‘At present, [complex] problems are officially recognised as such only after several failed attempts to tame them.’

The researchers concluded that the benefits of a complexity toolkit include:

‘• ‘Getting inside the black box’ of the problems covered;

• Developing a sharper understanding how wider contexts shape and influence a given problem;

• Providing more sophisticated analyses of the potential causal pathways through which a change process might unfold;

• Bringing multiple perspectives together to broker a common understanding;

• Supporting the development of strategies to cope with inherent complexity, thereby giving a more systematic way of working towards ‘best fit’;

• Providing an analytical platform for experimentation and learning and supporting a more adaptive management approach with appropriate evidence-based tools.’

While I thought the paper was excellent, overall, I had to read it a couple of times to write this post – the language is often quite abstract, and I hankered for much more specific ‘so whats’, for example, what you would do differently compared to a traditional trade project.

My general take away is that the project focused at the analysis stage, helping us understand the nature and dynamics of complex systems. Even this is a big step forward on generating a log frame and blindly following it regardless of reality. But whether there are specific toolkits for what you then do, beyond ‘try lots of stuff, learn, adapt and iterate’ was less clear to me. Perhaps this should be the focus of follow-up work?

One other issue, this kind of approach seems to work best for the big guys (and gals) – organizations like DFID that are trying to influence an entire  system, like a large chunk of Nigeria’s trade. For small players like Oxfam, there would have to be more focus on how other organizations are intervening (absent from this paper), and which small, simple interventions are compatible with complex systems (see the ‘responding’ bit of my recent post on complexity and small island states).

system, like a large chunk of Nigeria’s trade. For small players like Oxfam, there would have to be more focus on how other organizations are intervening (absent from this paper), and which small, simple interventions are compatible with complex systems (see the ‘responding’ bit of my recent post on complexity and small island states).

Anyway, over to you. ODI, which is publishing the final version as a Working Paper, and DFID, which sponsored the work, are interested to see if posting the draft on this blog produces useful comments and feedback – please don’t shame me up/let me down!

May 5, 2014

What’s at stake in the South African and Malawi elections this month?

Max Lawson, Oxfam’s Head of Advocacy and Public Policy, reflects on impending elections in South Africa and Malawi

Malawi and South Africa’s election cycle is identical. Both had their first democratic multi-party elections 20 years ago this month. Who can forget the  incredible photos of black people queuing from before dawn across South Africa to exercise their right to vote for the first time.

incredible photos of black people queuing from before dawn across South Africa to exercise their right to vote for the first time.

Malawi’s freedom might not have been as world famous, but Malawians rejoiced at the end of 31 years of dictatorship by the Homburg hatted Dr Hastings Banda, who before becoming dictator of Malawi at the age of sixty was a medical doctor in the London suburb of Brondesbury Park for 20 years. Now that is what I call a second career.

I visited both countries in the last few weeks, and in both, election fever was in full swing, with every available space plastered with party posters. Politics and the outcome of the election filled the media and dominated conversation. Elections are exciting things. South Africa goes to the polls tomorrow (May 7th) and Malawi on May 20th.

Yet the excitement is tinged with more than a small sense of disillusionment. No one I met or spoke to said they were not going to vote, but most were unenthusiastic. Both countries are about to go to the polls for the fifth time since freedom, and it is fair to say that the sheen has definitely rubbed off democracy.

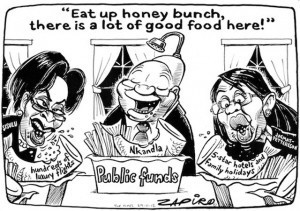

Both countries have been rocked by a series of corruption scandals and ‘gates’. In South Africa, they have Nkandlagate, where the Government, according to the Public Protector’s report, has been found to have spent millions of taxpayers’ money on Jacob Zuma’s private residence in Nkandla in Zululand, which now boasts helipads, massive swimming pool, etc all in the name of security . In Malawi the government of Joyce Banda, Africa’s second female president, has been rocked by Cashgate, where ministers and senior civil servants misused a government computer system to steal millions of dollars.

Yet despite these scandals, both Jacob Zuma and Joyce Banda are expected to be re-elected. The ANC majority may fall, perhaps dipping below the watershed level of 60% for the first time. The party of Mandela is being deserted to the left by those opting instead for the Economic Freedom Fighters of Julius Malema, and those who are choosing to vote for the Democratic Alliance, historically the party of the whites. The opposition to Joyce Banda is split between three major other parties.

Yet despite these scandals, both Jacob Zuma and Joyce Banda are expected to be re-elected. The ANC majority may fall, perhaps dipping below the watershed level of 60% for the first time. The party of Mandela is being deserted to the left by those opting instead for the Economic Freedom Fighters of Julius Malema, and those who are choosing to vote for the Democratic Alliance, historically the party of the whites. The opposition to Joyce Banda is split between three major other parties.

In Malawi, Oxfam is running an election campaign, focusing on supporting poor farmers’ demands of prospective candidates that they pledge to do more to help the rural poor, for example by reviving government purchasing of crops and improving the price they get for their produce. A tiny private sector and effective privatisation of the state marketing board under World Bank instruction has left productive farmers across the country being forced to sell at knock down prices or else watch the fruits of their labour rot. I witnessed 4 powerful women farmers berating candidates for constituencies in Mchinji district, about 100 miles to the west of the capital Lilongwe. One woman farmer looked them in the eye and said in Chichewa ‘never forget, you work for us’. Brilliant. I also attended the second live presidential candidate’s debate, which saw all candidates having to answer questions on a range of topics broadcast to the nation. It was rather dull to be honest, mainly due to a very boring moderator. I found myself wishing he could be swapped for the woman farmer who would have given them all a proper roasting.

It is heartening that press freedom in both South Africa and Malawi, although constantly under threat, remains strong and very vibrant compared to many other countries. In South Africa the press coverage and investigation of government is unremitting. Malawi, by a quirk of fate is one of the only African countries to have a fully independent national radio station, Zodiac. They were the ones who revealed live on air that the last president, Bingu Mutarika, had died, even whilst the government radio continued to insist he was merely ill and had been taken to hospital. It was in no small thanks to Zodiac telling the nation the truth that the country avoided a coup.

In South Africa there has been much soul searching over what has been achieved in the twenty years since the first democratic election. Millions of houses have been built; millions of South Africans benefit from a strong system of social grants; millions more from better access to services. Poverty levels have reduced. Yet there is still a feeling of an opportunity lost and much more that could have been achieved given the available resources. South Africa is now more unequal than at the end of Apartheid, with a handful of billionaires holding the majority of the country’s wealth, whilst 7 million still live on less than $1 a day.

It is not just the supporters of Julius Malema who are asking whether political freedom is worth much against this backdrop of extreme economic  inequality, and whether the price paid for political freedom – agreeing not to challenge the dominant economic system in the country – was too high. In Malawi too, poverty has remained stubbornly high in the last twenty years, and the majority have very little to show for the country’s political progress. Indeed whilst no one wants a return to dictatorship, many do speak fondly of the days of Banda, when they felt they had more economic security. Certainly in the many years I have been going to Malawi, the only growth industry seems to be big houses for politicians and expatriate aid workers, and a surfeit of shopping malls.

inequality, and whether the price paid for political freedom – agreeing not to challenge the dominant economic system in the country – was too high. In Malawi too, poverty has remained stubbornly high in the last twenty years, and the majority have very little to show for the country’s political progress. Indeed whilst no one wants a return to dictatorship, many do speak fondly of the days of Banda, when they felt they had more economic security. Certainly in the many years I have been going to Malawi, the only growth industry seems to be big houses for politicians and expatriate aid workers, and a surfeit of shopping malls.

As Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis said at the time of the great depression in the US, ‘We can either have democracy in this country or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both’. A recent 30 country survey by the London School of Economics has shown that higher levels of inequality are strongly associated with lower levels of voter turnout among the poor and wider civic disengagement. That is heartbreaking, as democracy is the only thing that can peacefully defeat extreme wealth. Disillusion with democracy is dangerous. In the short run it favours those at the top. In the long run, it favours nobody.

And here’s a useful Economist infographic on South Africa 1994 v 2014

May 1, 2014

For tax dodging: ‘pounded by stone mallet, grounded by large stone’. A nice day out in Singapore

As you have probably guessed by now, I’ve been in Singapore this week. What you won’t know is that this is my first time here since 1969 (my dad was  in the navy, which exited the island around then, along with the rest of Britain’s colonial baggage – Singapore promptly took off and has never looked back.)

in the navy, which exited the island around then, along with the rest of Britain’s colonial baggage – Singapore promptly took off and has never looked back.)

While the street names and the humidity brought back memories, most of my childhood haunts are gone. Except for the Tiger Balm Gardens, now renamed the Haw Par Villa, a completely insane sculpture park built by the two flamboyant founders of the Tiger Balm ointment empire (check out the tiger themed car they drove around Singapore).

The sculptures evoke various Chinese myths and legends, of which the most grisly (and so most interesting, to me at least) is the ‘ten courts of hell’. This is the graphic depiction of the Chinese equivalent of Dante’s inferno, full of weeping, wailing (and presumably gnashing of teeth) as the departed are subject to a series of really quite imaginative forms of torment.

My attention was caught first by the approach to educational misconduct:

Misuse of books

Crime: misuse of books

Punishment: ‘Thrown onto tree of knives; body sawn into two’

Seems fair to me. How about something more serious, like cheating in exams? ‘Intestines and organs pulled out; body dismembered.’

Now you’re talking. I’m beginning to understand the basis of Singapore’s stellar school performance.

But as I moved past the rest of the ten courts, I realized that here was the potential for a whole series of ground-breaking policy recommendations for NGOs working across the spectrum. Here are a few options, with pics. No need to thank me.

NGOs: Save the Children and Helpage International

Crime: Neglect of children and old people

Punishment: Impaled on a stake

neglect of children and old people

NGOs: Transparency International

Crime: Corruption

tax dodger

Punishment: ‘Thrown into volcanic pit; frozen into blocks of ice; thrown into pools of blood and drowned’

NGOs: Tax Justice Network, Christian Aid, ActionAid

Crime: Tax Dodging

Punishment: ‘Pounded by stone mallet, grounded by large stone.’

My host in Singapore, Max Everest Phillips of the UNDP’s ‘Global Centre for Public Service Excellence’, was just as entranced as me, but wanted to do a development version (‘excessive organization of awaydays; brain sucked out through nose with a straw’). But I had to catch my plane, so that will have to wait til my next visit.

Meanwhile, I am going to have to ask my mother what on earth she was doing bringing her kids here for a nice day out…….

April 30, 2014

How can complexity/systems thinking help small island states?

‘It’s a big year for small islands’ announced the speaker before me, who revelled in the title ‘The Honourable Lord Tu’ivakano, Prime Minister, Kingdom  of Tonga’ (right). When my turn came, how should I refer to him? (I’m hopeless at this kind of thing, must come from going to a state school.) His Lordship? Your Honourableness? ‘Yo Tu’ivakano’ (a la George Bush)? In the end, I just played safe with ‘Prime Minister’.

of Tonga’ (right). When my turn came, how should I refer to him? (I’m hopeless at this kind of thing, must come from going to a state school.) His Lordship? Your Honourableness? ‘Yo Tu’ivakano’ (a la George Bush)? In the end, I just played safe with ‘Prime Minister’.

It’s a big year because the Small Island Developing States (SIDS), have their once-a-decade conference coming up in Samoa in September, and in the run up, the UNDP’s ‘Global Centre for Public Service Excellence’, based in Singapore, invited me to speak at an event on the relevance of complexity and systems thinking (I think it was because Ben Ramalingam was busy…..). The idea was to use a complex systems approach to go beyond the discussion on climate change and vulnerability, and cover a bunch of other issues ably summarized in this paper by Max Everest-Phillips of UNDP, who hosted the event.

My powerpoint is here (Duncan Green Complexity and SIDS 2014 - please plunder). I’ll spare you the standard intro to complexity/systems thinking, and get onto the SIDS bit. As a group, SIDS share some common characteristics:

They are more vulnerable to shocks (commodity prices; climate; lower levels of economic diversification, highly dependent on imports, especially food)

Small populations (100,000 in the case of Tonga) means they are short on skilled specialists

There is a premium on political leadership, rather than institutions

But everyone knows everyone else, meaning denser networks of internal social capital

Thinking through their situation in responding to complexity, I suggested an ‘adaptive approach’ to change, in which governments need to plan for capacity (allocating money and staff) but realize that those staff will often have to improvise in responding to events, rather than follow a pre set plan. To help them do this, states need to think about three areas

Enabling Environment

Sensing

Responding

Enabling Environment

States can equip their people to experiment and respond to events, by guaranteeing their rights and access to information, and investing in education, healthcare and other public services.

Political Leadership, especially in SIDS, is crucial. Leaders need to create a compelling narrative that binds society together, reinforces social norms and provides ‘moral messaging’, especially during crises.

States need to build resilience by tackling ‘risk dumping’ and inequality, and (as far as it is possible in SIDS) ‘sowing diversity’.

Sensing

In complex systems where you can’t predict events, states need to invest in getting fast feedback from their people, by building good systems of consultation, and employing officials who are embedded in the world around them, pick up signals of change, and bring them into the office.

Positive Deviance: Rather than follow the latest management consultant fad, states can look around them and see what good stuff is already happening on the island. Which communities seem more resilient to shocks? Then go and observe to try and find out why. This is also the perfect opportunity to bring the voice of poor and vulnerable people into the conversation.

Failing forwards: all states fail sometimes. The question is whether you admit it, learn from it, and move on, or cover it up and squander the potential for learning new lessons.

Failing forwards: all states fail sometimes. The question is whether you admit it, learn from it, and move on, or cover it up and squander the potential for learning new lessons.

Results for grown-ups (counting what counts; put more L in your MEL). I think I may have mentioned this before…….

Responding

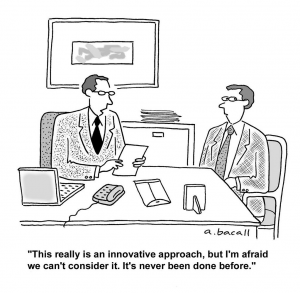

This largely covers familiar ground, at least to readers of this blog: Shocks as opportunities (red button system); Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation; Hybrids and best fit, not cookie cutters; Venture Capitalist multiple start-ups (e.g. via trust funds) and no regrets solutions (which means when trying something out, explore whether anyone will be hurt if it either fails, or turns out not to actually solve the problem) – see cartoon.

In the discussion that followed, the most promising angle, intriguingly, emerged out of Singapore’s record on public housing, which appears to have been an exercise in PDIA. According to Vanessa Chan, a wonderfully posh senior official from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs ‘solutions are organic – our public housing policy is the big example. We had a lot of people living in slums, so the problem was easy to identify. Then we went round the world, looked at what others had done, identified their mistakes, tried to avoid them. Build a few blocks, see what works/doesn’t, adapt the plans and build a few more.’

So I am now off to talk to UNDP about how they, the Singaporeans, maybe even Oxfam, could work together to apply that approach to building climate change resilience. Watch this space – would be great if we could get this on the agenda in Samoa.

And a nice surprise; the organizers asked Vanessa Leong, a student at Singapore Management University with a talent for caricature, to dash off this impression of me banging on about complexity and SIDS – reckon I should emulate Chris Blattman, and swap the cartoon me for the Dr Evil pic at the top of this blog/twitter?

April 29, 2014

Is advocacy only feasible in formal democracies? Lessons from 6 multi-stakeholder initiatives in Vietnam

Andrew Wells-Dang (right) and Pham Quang Tu (left) on how multi-stakeholder initiatives can flourish even in relatively closed political systems such as Vietnam

Andrew Wells-Dang (right) and Pham Quang Tu (left) on how multi-stakeholder initiatives can flourish even in relatively closed political systems such as Vietnam

How can NGOs be effective advocates in restrictive political settings? Global comparative research (such as this study by CIVICUS on ‘enabling environments’) often concludes that at least a modest degree of formal democracy is necessary for civil society to flourish…including, but not limited to NGOs. Yet our experiences in Vietnam, which is commonly thought to be one of those restrictive settings, have shown that there is somewhat more space to carry out advocacy than appears at first blush – if advocates have a clear understanding of the national context and appropriate advocacy strategies.

We’ve seen effective advocacy take place around environmental and health issues through the initiatives of networks of formal and informal actors. At times, such as the disputes over bauxite mining in the Central Highlands (see here and here), networks have gone beyond the ‘invited spaces’ of embedded advocacy to boundary-stretching strategies of blogging, petitions and media campaigns. These actions defy the standard state-society dichotomy, bringing together activists and officials, intellectuals and community groups from around the country. At base is a realisation that social and policy problems are too big and chaotic to be resolved by state or non-state actors alone.

Last year, Oxfam joined with a diverse coalition of local NGOs, media, and individual experts to press for revision of Vietnam’s Land Law. When we started, even some of our own NGO and media partners thought the topic was too ‘politically sensitive’. The coalition showed otherwise, finding allies in some local government and (state-owned) media agencies and using a mix of persuasion and publicity to attract the attention of national-level policy makers. When the initial draft law did not address many underlying problems, the coalition (later adopting the name of Land Alliance or ‘Landa’) successfully pressed the National Assembly to postpone voting on the bill by five months.

Vietnamese National Assembly delegates read reports and recommendations of the land policy coalition displayed at the assembly session, November 2013 (photo: Nguyen Duc Thinh)

Some of the land policy coalition’s recommendations on community consultation, limits on compulsory land acquisition by the state, and secure land tenure were reflected in the final revised law that passed in November 2013. But even recommendations that were not accepted still had a strong effect on public sentiment and media coverage, raising prospects for further policy changes in coming years. In one province (Hoa Binh), community consultations followed by workshops and media exposure visits resulted in local authorities returning 3,000 hectares of land from state ownership to villagers’ own use.

The land policy coalition is one of six multi-stakeholder initiatives currently supported by Oxfam in Vietnam through a DFID-funded advocacy programme. (The other 5 coalitions, all domestic and single-issue based, are working on agriculture, clean water, forestry, health, and mining.) We identified existing and prospective coalitions through a process of political economy analysis considering the topic’s level of public concern, possibilities for policy reform, and prospects for successful cooperation among members.

Each of the coalitions has a coordinating organization – usually an NGO, in one case a provincial university research centre – and from 5-20 members. Coalition members can be either organisations or individuals: in addition to NGOs and universities, they include retired officials, journalists, business associations, and government departments. In some cases, people who are not formal members nevertheless contribute significantly to the coalition’s work.

DFID and Oxfam provide several types of support to coalitions. Modest funding is available for core operations: workshops, communications, and a few salaried positions: a full-time coordinator and two part-time communications and monitoring-evaluation-learning officers. We’ve found that this keeps the coalition working smoothly without creating a top-heavy secretariat.

Second, we help each coalition develop a multi-year advocacy strategy and annual work plans made up of a series of issue-based projects (IBPs), which link advocacy efforts with research and campaigning. Each of the IBPs must be carried out jointly by at least two coalition members and focus on distinct policy processes, extending from public debate to leaders’ commitments, policy content and implementation.

Equally important in our view is coaching and capacity building, which goes beyond classroom training to facilitated learning and sharing, internal study visits, cross-coalition workshops, and a large amount of one-on-one encouragement and advice. We particularly emphasise the role of theory of change-based strategy formation, communications and media outreach, and real-time monitoring and evaluation. For the latter, Oxfam has teamed with Oxford Policy Management to develop Qualitative Assessment Scorecards for both internal coalition building and policy effectiveness. Every six months, coalitions self-assess their progress on a series of 10 indicators, then their scores are reviewed (and sometimes challenged) by Oxfam and the programme’s Advisory Panel.

The multi-stakeholder approach is new for coalition members and programme managers alike. All of us are more familiar and comfortable with  traditional projectised approaches to development – and with single-sector networks or NGO working groups. Inevitably, some participants perceive the programme as a funding opportunity more than an invitation to cooperate with others in an advocacy campaign. We’re attempting to preserve as much flexibility for coalitions as possible within the limited time frame and financial regulations inherent in a donor-funded programme.

traditional projectised approaches to development – and with single-sector networks or NGO working groups. Inevitably, some participants perceive the programme as a funding opportunity more than an invitation to cooperate with others in an advocacy campaign. We’re attempting to preserve as much flexibility for coalitions as possible within the limited time frame and financial regulations inherent in a donor-funded programme.

Even strong coalitions can take years to achieve their policy objectives, yet opportunities for reform tend to be time-bound and fleeting depending on political calendars and external events. Some of the open questions we are still exploring are whether (and in what circumstances) coalitions and networks can become ‘sustainable’ and proactive, rather than only temporary responses to a policy obstacle (stop the dam!) or a donor priority. We are also trying to find the right balance between professional leadership and internal coalition diversity including ethnic minorities, women, and community organisations.

These are ordinary sorts of challenges, perhaps not so different in a single-party political system as anywhere else. How does our experience compare to yours in other countries?

Andrew Wells-Dang is Senior Technical Adviser, Oxfam-Vietnam and author of a book on civil society networks in China and Vietnam as well as a World Bank paper on the land coalition experience. Pham Quang Tu is Team Lead of the Advocacy Coalitions Support Programme.

April 28, 2014

I had no idea that working across disciplines (on innovation, complexity and scale) was this painful, but it might be worth it

I went off to New York last week at the invitation of the UNDP Regional Center in Europe and Central Asia to discuss using complexity thinking to design a new ‘Finch Fund’ to support innovation and scaling up. Most scale-up exercises take successful pilots and just try and replicate them (one of the UNDP organizers, Millie Begovic, memorably likened it to trying to turn a particularly cute baby into a really enormous baby, rather than an adult). The Finch Fund is looking for a better way, and thinks complexity and systems thinking could be the answer, so it decided to try a bit of ‘interdisciplinarity’. I spent the day with a handpicked group of psychologists, ecologists, philosophers and economists all working on complex adaptive systems. It was horrible, but productive (I think).

a new ‘Finch Fund’ to support innovation and scaling up. Most scale-up exercises take successful pilots and just try and replicate them (one of the UNDP organizers, Millie Begovic, memorably likened it to trying to turn a particularly cute baby into a really enormous baby, rather than an adult). The Finch Fund is looking for a better way, and thinks complexity and systems thinking could be the answer, so it decided to try a bit of ‘interdisciplinarity’. I spent the day with a handpicked group of psychologists, ecologists, philosophers and economists all working on complex adaptive systems. It was horrible, but productive (I think).

Leaving your discipline is traumatic – akin to being suddenly infantilised and made vulnerable. From being a bit of a development know-all, I became a know-nothing, resentfully observing an incomprehensible exchange of references, books, jargon and gossip (oh, Bob’s at Yale now, is he?). I got angry, sullen, even contemplated walking out in protest.

But I didn’t flounce out, and instead (perhaps inspired by Robert Chambers‘ call for greater reflection in our work) started musing about what was going on in my head.

Lesson 1: ‘Interdisciplinarity’ is tough: be prepared for some serious mood swings.

Lesson 2: Beware geeks bearing gifts. What kinds of people do you want in the room? I would say the ability to empathise is probably more essential than being top of the field. Choose on the basis of emotional intelligence as well as the more academic kind. Some of this lot failed pretty heavily (maybe they were exacting revenge for being bullied at school) – if you ever see me give a furtive little smile of self satisfaction when someone says they can’t follow what I’m saying, please give me a slap.

Lesson 3: I found myself veering between ‘oh wow, this is a whole new way of seeing the world’ and ‘this is just describing what we do already in a new vocabulary’. Need to resist both temptations, and try and sift through the murk for the occasional nugget.

Yeah, right

But how you do that depends on whether you are trying to immerse yourself in a whole new paradigm (painful, you have to leave aside your reference points, with no idea of where you are going to end up, or whether the journey will be worth the pain). The alternative, which I tend to prefer, is to enter enemy territory, briefly immerse yourself in ambiguity, uncertainty, alien vocabulary and ‘OMG I know nothing’ vertigo, then grab whatever is useful, and retreat back behind the development stockade to recover.

In real time, there is also a difficult choice between trying to follow every word (very difficult, and means you have to keep interrupting and asking for explanations, which gets humiliating after the first couple of times) or surfing the conversation, gliding over the bits you don’t understand and trying to grasp the overall shape of the thought process, but never quite knowing if you’ve missed the important stuff.

What, if anything, came out of my day of rage?

Actually it may prove quite productive. At a minimum, the Finch Fund (so named after the Galapagos finches that inspired Darwin’s theory of evolution) will look for projects that include:

Multiple parallel experiments on a similar issue, where it’s OK (in fact required) to fail on some of them (a bit like the Tanzanian accountability project that I go on about a lot)

Positive deviance: clear evidence that the teams have studied what is already happening in their countries and issue areas and identified particularly positive or negative outliers as part of the experiment.

Fast feedback, especially from poor people, which determines how the set of interventions evolve and change.

Don’t overdesign: built-in flexibility will allow any given intervention to morph and evolve in response to feedback.

If it just stops there, the Finch Fund will be pretty unique and I think could provide a really influential model for how to think more intelligently about ‘going to scale’.  Some other, deeper ideas may have been lurking in the fog of jargon that could make it even more interesting. They revolve around how to identify systems that are particularly propitious for rapid evolutionary change. In general these have a steep gradient of difference between different parts of the system, a high level of ‘microdiversity’, and feedback systems with costs that fall as a change goes to scale. Not sure quite what such ideas would mean in practice – let’s see how the Fund gets on.

Some other, deeper ideas may have been lurking in the fog of jargon that could make it even more interesting. They revolve around how to identify systems that are particularly propitious for rapid evolutionary change. In general these have a steep gradient of difference between different parts of the system, a high level of ‘microdiversity’, and feedback systems with costs that fall as a change goes to scale. Not sure quite what such ideas would mean in practice – let’s see how the Fund gets on.

Two other dilemmas: what is the right response to a complex system; study it really hard to try and understand it better, or accept that you cannot fully understand it, so trial and error is a better approach? Reminiscent of the evolutionary culture wars between intelligent design and random mutation + natural selection!

Secondly, the toolkit temptation. If we want this approach to be adopted, we will have to set out guidelines for how it works, what questions to ask, what to avoid etc. i.e. a toolkit. But isn’t that contradictory, if a central point about complex systems is that they defy blueprints and best practice? Time for the padded cell………

And for some early thinking (and good discussion in the comments) on the Finch Fund from the UNDP’s Milica Begovic Radojevic and Giulio Quaggiotto see here and here.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers