Duncan Green's Blog, page 186

June 24, 2014

Strengthening active citizenship after a traumatic civil war: dilemmas and ideas in Bosnia and Herzegovina

I went to Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) last week to help Oxfam Italia develop advocacy and campaign skills among local civil society organizations. They have their work cut out.

Firstly, there is a crisis of trust between the public and CSOs, which are poorly regulated, often seen as little more than ‘briefcase NGOs’, only interested in winning

Protests in February over jobs and corruption have fizzled out

funding, and under constant attack from politicians. Many CSOs seem pretty disillusioned, faced with a shrinking donor pot and public hostility.

I think there’s a strong case for the CSOs to take the lead in putting their house in order, practicing what they preach on transparency and accountability, and working with government to sort out the legitimate organizations from ones that have registered (there are some 10,000 in the country) but do nothing, (or worse).

Meanwhile, Oxfam is working with some of the more dynamic ones to develop the advocacy and campaign skills of what is still a maturing civil society network (after decades of state socialism, followed by a devastating war, and then an influx of donor cash that had mixed results). Two days of conversation and debate with some great organizations working on everything from disability rights to enterprise development to youth leadership identified some big issues and dilemmas:

Actions speak louder than words: ‘People trust you if they directly benefit from your work.’ When CSOs have a reputation for being self-serving talking shops, people want to see practical results – advocacy-only approaches look like a non starter.

Coalitions and alliances: CSOs sometimes seem reluctant to play nicely with others – faith organizations, politicians, officials, academics, business groups. Yet doing so not only increases impact, but could also increase public trust and legitimacy. There’s a clear role for Oxfam in helping get those conversations going.

Municipal v National: National politics is a fragmented, multi-tiered mess (see yesterday’s post), with little clarity on decision-making. How do you campaign when you have no idea who’s in charge? Better to focus on the municipal level, where lines of accountability are clearer, and NGOs are more likely to be taken seriously.

Positive deviance: Conversations are dominated by (often well-justified) complaints. One Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) network had painstakingly compiled and published 147 obstacles to SMEs (credit, red tape, infrastructure, skills etc etc). But is that really the best basis for a campaign? Why not identify, analyze and publicise examples of positive outliers – which municipalities have done better than most on any given issue and why? As another SME lobbyist observed, ‘Carrots work much better for mayors – they like photos with awards’.

Putting those last two together, one option that got people seriously interested was the PAPI project in Vietnam, which publishes league tables comparing local government performance. Why not put together some of the issues CSOs are working on, develop a credible methodology and then use league tables to start a ‘race to the top’ between photo-opportunity seeking mayors?

Next generation: with such a complex and often poisonous legacy from statism and civil war, it is tempting to skip a generation: how to identify and develop student leaders-of-tomorrow? How to break the cycle of ethnic hostility?

A window slams shut?

Windows of Opportunity: CSOs seem a bit trapped in their project and funding cycles, exacerbated by dependence on external funding. A graphic example was provided by the response to the recent floods. After talking about the sudden upsurge in citizen activism, the anger with the authorities and its great plans to work on improving water and sanitation, one leading activist commented ‘Our role is to be on the same track as before the flood, get back to the developmental things. We didn’t have a conversation about windows of opportunity.’ Oh dear.

Easy wins to build momentum: when people feel frustrated and powerless, find an easily winnable, small thing, and make a very big noise about winning it. In Cardiff, my son’s organization, Citizens UK, found that young Muslims were fed up with the local Nando’s not offering a halal option. So they organized a very noisy, public campaign, and of course, Nando’s changed the menu. A phone call might have done the trick, but a big public campaign helped the local kids realize that they had the power to change things.

Norms, implementation gaps or new Policies? The CSO default option seems to be to lobby for new laws, when everyone agrees that BiH already has lots of lovely legislation, all largely ignored in practice. One alternative would be to work on implementation gaps. But maybe, faced with such a difficult and unresolved set of ethnic and religious tensions, and generalized sense of powerlessness and futility, working on norms might make more sense. For example, identify those bits of society that cross religious boundaries – sport, business, youth culture – and build on those.

Working with the Diaspora: There are millions of Bosnians overseas, sending home about $1000 per head of the remaining population. What else could/would they do, if encouraged and facilitated? Fund social investment? Mentor new businesses? VC style funds for social innovation?

Northern campaign tactics: BiH is relatively well off, highly connected, and very European in feel. So importing ideas from northern campaigns might make a lot of sense – clicktivist crowd sourcing on corruption (OK, that one’s from India) or public services; whimsical campaigns by ad agencies working pro bono; celebs (sadly, UNICEF already grabbed Edin Dzeko, the national soccer hero).

And one question for readers – how to rebuild active citizenship after a bloody conflict in a European country, with big ethnic/religious divisions– what would be good comparators for exchanges of lessons? Northern Ireland? Your suggestions please.

June 23, 2014

20 years after the war, politics is frozen in Bosnia and Herzegovina: first impressions from last week’s visit

Just got back from a week visiting Oxfam Italy’s programme in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH from now on). It wasn’t what I expected. For a start, it never stopped raining

War? What war?

(and I say this as an Englishman).

And the traumatic war of 1992-95, which left some 100,000 dead (the exact figure is still disputed), and engraved names like Srebrenica, Tuzla and Mostar on the memories of our generation, is almost invisible now. Today they are just modest European towns. Nothing iconic here, move along please.

So what’s it like? 20 years after its traumatic four year siege, Sarajevo, the capital, is miraculously restored, thanks to European, US, Turkish and Middle East money. Tourists mill on the cobbled streets of the Ottoman quarter; imposing buildings in the Austro Hungarian bit; elsewhere, the glass towers and malls of 21st Century capitalism.

The buildings may have been repaired, but not the politics or the people. A sense of brittleness lurks beneath the trappings of modern Europe. No-one talked to us about their war experiences all week (and we were advised not to ask – better to let people volunteer their stories when they are ready). To fill the gap, I read Aleksandar Hemon’s brilliant and harrowing account, The Book of My Lives.

We drive out of Sarajevo along a pristine EU-funded motorway, alongside rushing swollen rivers passing through hillsides of gravestones. Scatters of solid alpine chalets, dotted with the needle minarets of mosques in some areas, church crosses in others. The war divided communities; peace froze those divisions in place: the Dayton Agreement that stopped the bloodletting 20 years ago is asphyxiating political progress now, and has no provision for review or evolution.

It made sense at the time

The religious mosaic is reflected in the institutional divisions established by Dayton: A largely Bosniak (Muslim and Catholic Croats) Federation and a Serb Republika Srpska (Orthodox) form two separate ‘political entities’ within a not very powerful BiH ‘state’ (see map). The entities have different internal structures, producing a mind-boggling level of complexity. Listen to businessman Mladen Ivesic:

‘The administration is huge, too many overlapping tiers of government: cantons, municipalities, entities, state. All have departments, ministries (BiH has 162 ministries!). They send us to and fro, play with us. Everyone blames everyone else. But if you give them €100, suddenly they know who’s responsible – more levels of government mean more opportunities for corruption.’

I was travelling with a South African colleague (Hugh Cole) so the comparison was inevitable. BiH has no Mandela, no Truth and Reconciliation process, no agreed history of what actually happened. In the words of Silvana Grispino, Oxfam’s country director ‘the collective memory is fragmented and manipulated, so how can we imagine the future?’

People talk with nostalgia of Yugoslavia, whose disintegration triggered the war. Memories of the good old days were triggered by the public response to May’s catastrophic floods (below), which killed 44 people and did billions of dollars of damage to BiH and Serbia. ‘We felt like before, in the era of rich socialism [before 1991]’ says one university professor, after supposedly apathetic students headed off in droves to volunteer for the cleanup. Mosques and churches handed out food to the victims, regardless of faith. But the euphoria rapidly dissipated as rival political parties started to score points off each other and refused to cooperate.

Not everyone agrees that Dayton is a problem (after all Switzerland has four official languages and a labyrinth of local government, but seems to muddle through), but it certainly complicates any attempt by ordinary citizens to engage with politics. Here’s Mladen again:

‘Politicians will always try and drag you down (if you protest or call for reform), saying this will harm this or that religious group. The people are very afraid, frustrated  and easy to manipulate. They have no strength to fight. Young people leave if they can. Europe has to help – we cannot solve this problem by ourselves. This constitution was imposed, mainly by America, so they have to solve it. We call it the straitjacket.’

and easy to manipulate. They have no strength to fight. Young people leave if they can. Europe has to help – we cannot solve this problem by ourselves. This constitution was imposed, mainly by America, so they have to solve it. We call it the straitjacket.’

Government officials agree (but ask to remain anonymous): ‘The Federation and the RS are totally separate and often reject the rules and regulations of the State. We lost $0.5bn of EU pre-accession money because of the disputes. Dayton created peace, but now it is a bottleneck. Everything is difficult, Dayton needs to change.’

The frustration is that away from politics, some things do actually work. Not everything is religiously polarized – business, sport (the country is obsessed with BiH’s first ever involvement in the soccer World Cup). And civil society is working to overcome the divisions – more on that tomorrow.

June 22, 2014

Links I liked

My twitter feed has been disrupted by being on a trip to Bosnia and Herzegovina (more on that later), and the over-excited outpourings of World Cup tweeting (sour grapes,

moi?) but here’s a few that slipped through.

Maptastic

The disease most likely to kill you, by country (some doubts on the stats, but they come from WHO)

Latin America still has the highest murder rates, by country, from the UN ‘Global Homicide Book’.[h/t Conrad Hackett]

Latin America still has the highest murder rates, by country, from the UN ‘Global Homicide Book’.[h/t Conrad Hackett]

Big Numbers

$7.6 trillion is hidden in the world’s tax havens. That means lost annual tax revenues of $200bn (50% more than official aid flows). [h/t Chris Jochnick] It also = $1000 for every person on the planet.

The global cost of violence in 2013 was $9,800,000,000,000 ($9.8 trn, 11.3% of GDP), according to the latest Global Peace Index

AOB

The propensity of Latin Americans to protest rises with education, income and age (up to about 48 years old, then it falls)

The BBC’s arch inquisitor Jeremy Paxman stepped down last week. Here he is in vintage form, subverting efforts to make him tell viewers about the weather [h/t Ian Bray]

And for the more obsessive UK politics heads, here’s the legendary time he asked a Tory Minister the same question 14 times (and still didn’t get an answer)

June 19, 2014

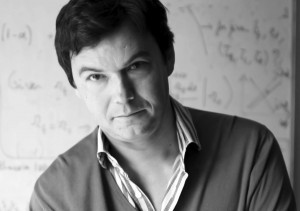

‘Economists know almost nothing about anything’. Yet another reason to love Thomas Piketty

From the intro to ‘Capital in the 21st Century’, a taste of his great approach to learning, the easy discursive style, (but also why the book is 600 pages long – succinct he ain’t. I’ve got to page 164):

“To put it bluntly, the discipline of economics has yet to get over its childish passion for mathematics and for purely theoretical and often highly  ideological speculation, at the expense of historical research and collaboration with the other social sciences. Economists are all too often preoccupied with petty mathematical problems of interest only to themselves. This obsession with mathematics is an easy way of acquiring the appearance of scientificity without having to answer the far more complex questions posed by the world we live in. There is one great advantage of being an academic economist in France: here, economists are not highly respected in the academic and intellectual world or by political and financial elites. Hence they must set aside their contempt for other disciplines and their absurd claim to greater scientific legitimacy, despite the fact that they know almost nothing about anything.

ideological speculation, at the expense of historical research and collaboration with the other social sciences. Economists are all too often preoccupied with petty mathematical problems of interest only to themselves. This obsession with mathematics is an easy way of acquiring the appearance of scientificity without having to answer the far more complex questions posed by the world we live in. There is one great advantage of being an academic economist in France: here, economists are not highly respected in the academic and intellectual world or by political and financial elites. Hence they must set aside their contempt for other disciplines and their absurd claim to greater scientific legitimacy, despite the fact that they know almost nothing about anything.

This, in any case, is the charm of the discipline and of the social sciences in general: one starts from square one, so that there is some hope of making major progress. In France, I believe, economists are slightly more interested in persuading historians and sociologists, as well as people outside the academic world, that what they are doing is interesting (although they are not always successful). My dream when I was teaching in Boston was to teach at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, whose faculty has included such leading lights as Lucien Febvre, Fernand Braudel, Claude Levi-Strauss, Pierre Bordieu, Francoise Heritier, and Maurice Godelier, to name but a few. Dare I admit this, at the risk of seeming chauvinistic in my view of the social sciences? I probably admire these scholars more than Robert Solow or Simon Kuznets, even though I regret the fact that the social sciences have largely lost interest in the distribution of wealth and questions of social class since the 1970s. Before that, statistics about income, wages, prices, and wealth played an important part in historical and sociological research.

The truth is that economics should never have sought to divorce itself from the other social sciences and can advance only in conjunction with them. The social sciences collectively know too little to waste time on foolish disciplinary squabbles. If we are to progress in our understanding of the historical dynamics of the wealth distribution and the structure of social classes, we must obviously take a pragmatic approach and avail ourselves of the methods of historians, sociologists, and political scientists as well as economists. We must start with fundamental questions and try to answer them. Disciplinary disputes and turf wars are of little or no importance. In my mind, this book is as much a work of history as of economics.”

Outstanding.

June 18, 2014

Working with unlikely bedfellows to turn BP Deepwater Horizon fines into local jobs: How Oxfam America adapted to doing advocacy in the Deep South

Next up in the series of case studies on ‘active citizenship’ is an impressive bit of campaigning by Oxfam America’s domestic programme, in response to the horrendous BP oil spill of 2010. Here’s the draft case study (Draft AC case study Gulf RESTORE campaign June 2014: comments welcome), which I summarize below.

‘We started with two Senators and ended up with 74 Senators supporting the bill. A House member said, ‘I didn’t think Jesus could get 74 votes in this  Congress.’’ Oxfam Ally

Congress.’’ Oxfam Ally

On April 20, 2010 an explosion in the Deepwater Horizon oil well started a spill that would ultimately release 4.9 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Twenty-two months later, President Obama signed the Resource and Ecosystem Sustainability, Tourism Opportunities and Revised Economies of the Gulf Coast States (RESTORE) Act into law, in July 2012.

The final bill requires that 80% of civil fines (which may reach as much as $20 billion) are placed in a Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund, to be distributed directly to the five Gulf Coast states and to a newly created Gulf Coast Restoration Council that will oversee how funds are utilized in the affected region.

While individual states retain significant decision-making authority, the law establishes a series of guidelines, restrictions and oversight mechanisms to ensure that the funds are allocated for economic and environmental restoration. This was where Oxfam America, its Coastal Communities Coalition (CCC) partners, the Gulf Renewal Project, and a broad range of allies concentrated their efforts, representing the concerns of poor, coastal communities disproportionately affected by the spill and pressing an agenda that included focused investment in socially vulnerable communities, work force development and preferential hiring of local people, and the establishment of participatory governance mechanisms.

The opportunities for influence were particularly great as Oxfam was the only large social justice NGO involved in a field dominated by environmentalist organizations, whose priorities often did not include the immediate interests of local communities.

Results

An upbeat January 2013 evaluation found that the campaign had ‘largely’ or ‘significantly’ achieved its goals on ensuring adequate long-term federal funding for Gulf Coast restoration, investment in resilience to strengthen communities, investment in transitional workforce development and contracting practices promoting access to opportunity.

It gets better. Oxfam America estimates the total investment in the campaign over two years at approximately $740,000 (USRO, 2013). It asked Mather Economics to model the potential impact of that spending in the area most clearly attributable to the campaign – workforce development and local hiring. Among the national NGOs engaged in the campaign, workforce development was considered Oxfam’s niche area and the area in which it had the greatest influence.

Mather Economics’ modelling gave a mid-range estimate was some 22,000 jobs created over a ten year period. While only a rough estimate (eg it assumes attribution to the campaign at 100%, when there must were probably other factors at play), this provides an approximate figure of 1 job created for every $34 spent on the campaign, a truly remarkable return. Moreover that does not include other benefits from the campaign.

Success Factors

The evaluation highlighted feedback from external allies and core partners on the key factors contributing to the campaign’s success. These included:

Oxfam and partners’ long-standing relationships with affected communities;

The campaign’s ability to create a broad-based coalition, especially its work with faith-based groups and the private sector;

Partners working closer to the ground pointed to different factors, including:

Intelligence from Washington, regularly conveyed to the Coastal Communities partners, about the political dynamics surrounding the RESTORE Act and progress on the bill;

The research products that were developed in consultation with them and which conveyed in layman’s terms their situation and policy positions. These were an important resource for partners’ outreach efforts to community members and local officials;

For their part, Oxfam staff stressed the impact of working with non-traditional allies, especially conservative evangelical churches and the private sector, and working with Republican lobbyists. Staff also highlighted the importance of media work and the many lessons learned from its Katrina advocacy, including the need to engage in policy discussion immediately after an emergency, before deals “begin to be cut”.

Theory of Change

Power Analysis: Understanding the nature of Gulf Coast politics and power was an essential prerequisite for the campaign. Republicans, Conservative Democrats, and evangelical Christians dominate the political map. Political relations at local and state level are highly clientelist, based on personal relationships. Working in this kind of environment was a challenge for a social justice/rights-based organization like Oxfam.

Change Hypothesis: The Gulf Coast campaign illustrates several aspects of ‘shock as opportunity’ – the idea that social and political change is often linked to disruptive events that open up new directions by weakening the powers that sustain the status quo, creating demands for change among both public and leaders, and dissatisfaction with ‘business as usual’.

The BP oil spill hit a region still recovering from the ravages of Hurricane Katrina. Katrina had also left several lessons, both in terms of failures and successes, upon which advocacy could build. One negative experience was the way reconstruction had relied on shipped-in undocumented labourers, with few jobs going to local people. Local hiring emerged as one of the key demands of the campaign.

Oxfam’s Change Strategy: Luck matters in campaigning and the timing of the BP oil spill could not have been better, coming just a month after the launch of Oxfam’s Coastal Communities Initiative, focused on addressing both environmental destruction and poverty as two of the root causes of social vulnerability. Moreover, off the back of Katrina, and prior to the BP spill, local communities had already formulated their demands for restoration – all that was needed was cash and political will, and the spill and subsequent fines provided both in abundance. The change strategy had three main thrusts.

Advocacy directed at the federal level in support of the RESTORE Act, which included extensive alliance building and direct advocacy with policy-makers in Washington, DC.

State level advocacy around workforce development and local hiring.

Support for partners’ programs, including local level advocacy on issues that were not directly related to the RESTORE Act, but which proved vital in establishing the relationships and partner capacity on which the campaign subsequently relied.

What have I missed? Your comments please. And in case you missed them, previously posted case studies were on Campaigning against Violence Against Women in South Asia, promoting Women’s Leadership in Pakistan, Labour Rights in Indonesia, and Community Protection Committees in DRC

June 17, 2014

What works in reducing gender inequality? Great overview from Naila Kabeer

We’ve been having an interesting internal discussion on inequality over the last few weeks, and this contribution from Naila Kabeer jumped out. So I thought  I’d nick it for FP2P

I’d nick it for FP2P

A gendered analysis of essential services highlights the scale of the inequality challenge but it also offers useful pointers for the design of more inclusive and effective social protection strategies. Social protection interventions need to acknowledge that gender inequality begins at birth and deepens during the life cycle of a woman. A gender analysis of poverty and vulnerability must be at the core of the construction of an inclusive and effective social protection strategy.

Gender analysis draws attention to:

some of the ways that people’s gender differentiates their experience of vulnerability;

gender inequalities beginning in the early years and the inequalities in household resources that are devoted to the well-being of children;

the greater degree of variation in a woman’s experience of vulnerability over the course of her life;

the cumulative nature of gender disadvantages that make women more vulnerable than men in the face of shocks and stress;

the struggles of working women, poor working women who manage the dual responsibilities of earning a living and caring for the family;

a lifetime of discrimination which leads to greater insecurity in old age.

Unable to pay others to take care of their children, poorer women face a harsh set of options if they are to earn a living. They can choose to work from home and accept the lesser pay involved. If they work outside, they may have to cope with a longer working day – they would have to rely on older children, usually daughters, to look after younger ones, they may take their children to work with them, or may leave them unattended in the house. All of these options have adverse consequence for women and their children. Married women with children are likely to face a very different set of constraints in managing their dual workloads to single women, women without children, or women who head households.

Early inequalities intersect with the domestic responsibilities and unpaid care that girls have to experience as they grow up. The result is that women face a far more restricted set of livelihood opportunities relative to men, rendering them dependent on male earnings to meet their need for survival and security. Women own fewer assets than men, thanks to discriminatory inheritance laws and lower lifetime earnings. They will therefore have saved less and will have fewer pension rights. A Social Protection Floor (SPF) must have a life-cycle basis and SPF design must make it easier for women to work, but also account for double burdens.

While women’s overall participation in the labour force varies considerably across the world, women from low income households in most contexts are either in work or looking for work. This is as true in India, where restrictions on women’s mobility in the public domain have led to lower rates of female labour force participation, as it is elsewhere. In India, poorer households simply cannot afford to keep women confined to the home.

While women’s overall participation in the labour force varies considerably across the world, women from low income households in most contexts are either in work or looking for work. This is as true in India, where restrictions on women’s mobility in the public domain have led to lower rates of female labour force participation, as it is elsewhere. In India, poorer households simply cannot afford to keep women confined to the home.

Here is some evidence from different countries…

Conditional Cash Transfers (CCT): Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme provides monthly cash stipends to mothers conditional on children’s attendance at school and attendance at health clinics. The program has now been in operation long enough for both immediate and longer term impacts to be visible. Studies suggest that not only has it succeeded in increasing the overall school enrolment of children from poorer households but also helped to close the gender gap in education. Education has enhanced women’s prospects in the labour market. Recent research suggests that young women who graduated from these programmes are finding jobs higher up in the occupational hierarchy than their mothers. This is particularly true for women from marginalized indigenous communities.

Public works quotas and accompanying care support for women: Public works programmes in their conventional forms tend to benefit able-bodied men. The guarantee of work to all adult members of households rather than to the head of the household or just one member has been a factor in explaining the success of the Indian MGNREGA program in drawing high percentages of women. While the MGNREGA specifies crèches wherever there are a minimum number of women on the worksite, this has not materialized in reality. Introducing quotas for women or, as with the Rural Maintenance Programme in Bangladesh, designing a programme intended specifically for women, may also help to promote their participation in contexts where discrimination may prevail. Redefining public work to include forms that women can more easily participate in is another option. Care-related work in South Korea and environmental work in South Africa were both found to be more conducive to women’s participation than construction work.

Direct transfers: Alternatively, in a number of African countries, there have been experiments with direct transfers to the working poor, many of whom are not able to participate in public works programmes. These may be provided as cash to subsidize food purchase as in Mozambique, or as vouchers tied to the purchase of specific assets or productive inputs. Direct transfer approaches are likely to be of particular benefit to women in those Indian states where there is no tradition of waged work for women, participation in the MNREGA is very low, and women have domestic responsibilities that make it difficult for them to participate in any public work.

Wage guarantees must be accompanied by other services: Social protection measures can be designed to challenge rather than simply reproduce gender inequalities. The Rural Maintenance Program in Bangladesh began by offering waged work to destitute women for a period of two years; but over time, and in response to various evaluations, built in a savings component as well as life and livelihood skills so that women graduated from the program equipped to start their own businesses. The ‘guarantee’ element in the MGNREGA program together with gender equality in the remuneration offered hold out the promise of citizenship to poor men and women although it is more likely to be realised in the presence of a pro-active bureaucracy and civil society.

gender inequalities. The Rural Maintenance Program in Bangladesh began by offering waged work to destitute women for a period of two years; but over time, and in response to various evaluations, built in a savings component as well as life and livelihood skills so that women graduated from the program equipped to start their own businesses. The ‘guarantee’ element in the MGNREGA program together with gender equality in the remuneration offered hold out the promise of citizenship to poor men and women although it is more likely to be realised in the presence of a pro-active bureaucracy and civil society.

Indirect and inter-generational design: Women’ s dual responsibilities within family and market mean that social protection measures directed at one set of responsibilities can have positive knock-on effects on the other. Conditional cash transfers in Brazil and Mexico, for example, were found to help women invest in their own education and in small livestock and poultry rearing alongside increasing their children’s education. In South Africa, not only did pensions to grandmothers have a more positive impact on the welfare on grandchildren than pensions to grandfathers, but it was also found to increase the mother’s labour force participation, since some of it was used to pay for transport and jobs search costs which they could not hitherto afford. In Mozambique, women were found to invest some of their food subsidy transfers in petty trading activities on the grounds that would enhance their ability to feed their children.

This is drawn from Naila’s contribution to a collection of essays on social protection floors.

June 16, 2014

Links I liked

Here’s the cream of last week’s twitter-crop

Some pretty pictures

Average number of firearms per 100 people (right). Yemenis and Yankees slugging it out for top spot. Datasource: The Guardian

Every country’s highest value goods export, [h/t John Magrath]

Relax, population controllers: the global slowdown is well advanced [h/t Kate Raworth]

Oxfam gets bashed for being ‘too political’ in its advocacy on rising hunger in UK

Which prompts an eloquent defence by Policy and Campaigns Director Ben Phillips v Tory MP on the BBC’s Today prog. Ban also bangs on in Huffpo

But if you want something a little more angry, try this mesmerizing taxi driver rant in defence of Oxfam [h/t John Magrath]

World Cup satire

‘Portugal’s Preparation: Entire team has been practicing writhing on ground in pain for months leading up to tournament’. The Onion’s guide to the national teams

OMG, what happened to the doves? [h/t Ellie Mae O’Hagan]

OMG, what happened to the doves? [h/t Ellie Mae O’Hagan]

The essential introduction to FIFA. Definitive takedown from John Oliver [h/t Chris Jochnick and Laura Rusu]

AOB

Democracy is failing on representation (in the North) and rights (in the South). Interesting call for rethink from Dani Rodrik

Ben Ramalingam (he of Aid on the Edge of Chaos) is starting a new blog-which-then-becomes-a-book exercise, called ‘The Third Transition‘, on infectious diseases

The bar on communicating evaluations just went up a notch. Smart 90 sec animation summarizes 17 country, 6 year ‘Raising Her Voice’ programme on women’s empowerment:

June 15, 2014

Are we measuring the right things? The latest multidimensional poverty index is launched today – what do you think?

I’m definitely not a stats geek, but every now and then, I get caught up in some of the nerdy excitement generated by measuring the state of the world.  Take today’s launch (in London, but webstreamed) of a new ‘Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2014’ for example – it’s fascinating.

Take today’s launch (in London, but webstreamed) of a new ‘Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2014’ for example – it’s fascinating.

This is the fourth MPI (the first came out in 2010), and is again produced by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), led by Sabina Alkire, a definite uber-geek on all things poverty related. The MPI brings together 10 indicators, with equal weighting for education, health and living standards (see table). If you tick a third or more of the boxes, you are counted as poor.

Here’s the basics for MPI 2014:

It covers 108 countries, with 78% of the world’s population

As well as multi-dimensional poverty, it adds a new, more extreme category of ‘destitution’ for 49 countries (eg two or more children have died in your household, rather than one, see second table)

It analyses changes over time since the last index for 34 countries, covering 2.5 billion people (a third of humanity)

Key findings?

A total of 1.6 billion people are living in multidimensional poverty; more than 30% of the people living in the 108 countries analysed (compare that with a global figure of 1.2 billion in income poverty)

Of these 1.6 billion people, 52% live in South Asia, and 29% in Sub-Saharan Africa. Most MPI poor people – 71% – live in Middle Income Countries (I won’t try and compare this with regional income breakdowns, as the MPI doesn’t cover all countries yet)

The country with the highest percentage of MPI poor people is still Niger; 2012 data from Niger shows 89.3% of its population are multi-dimensionally poor

Of the 1.6 billion identified as MPI poor, 85% live in rural areas; significantly higher than income poverty estimates of 70-75%

Of 34 countries for which we have time-series data, 30 – covering 98% of the MPI poor people across all 34 – had statistically significant reductions in multidimensional poverty

The countries that reduced MPI and destitution most in absolute terms were mostly Low Income Countries and Least Developed Countries

Nepal made the fastest progress, showing a fall in the percentage of the population who were MPI poor from 65% to 44% in a five-year period (2006-2011). Other star performers include Rwanda, Ghana, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Tanzania and Bolivia

Nearly all countries that reduced MPI poverty also reduced inequality among the poor

Over 638 million people are destitute across the 49 countries analysed so far – half of all MPI poor people

India is home to 343.5 million destitute people – 28.5% of its population is destitute.

In Niger, 68.8% of the population is destitute – the highest share of any country

What does the MPI add to our understanding of poverty?

It more closely matches the actual lives of the poor. As the World Bank’s great Voices of the Poor study showed fully 15 years ago, poverty is a state of being – characterized by shame, humiliation, anxiety and worry, much more than it is about ‘do I have more/less than $1.25 a day’. The MPI is only a first step away from the reductionism of income measures (we don’t have comparable data on shame and fear yet), but it’s a start.

It measures the intensity of poverty – being poor and sick is very different from being poor and healthy. As a result it provides incentives to policymakers to try to help people become ‘less poor’, and recognition when they succeed in doing so; not just plaudits for those people lifted from one side to the other of a poverty line.

It compares deprivations directly (have any children died in your household?), so no need to mess around with Purchasing Power Parity calculations. That’s both more tangible, and a relief when periodic adjustments in PPP creates such doubt and confusion over income poverty comparisons (by one calculation, global income poverty fell by half between a Tuesday and a Wednesday last month!).

It allows you to go into some fascinating fine grain analysis, eg Benin and Kenya both had significant poverty reductions, but when you disaggregate by ethnic group, in Benin poverty reduction was virtually zero among the poorest ethnic group (the Peulh), whereas in Kenya, poverty among Somalis fell faster than for the better off ethnic groups.

The rural/urban finding is interesting – lots of discussion elsewhere about whether income poverty can be meaningfully compared between urban and rural settings, for example because you need money for lots of things in urban settings that come free in rural (so urban poverty is higher, for a given level of income ). But the MPI finds the opposite – in terms of multi-dimensional poverty, the benefits of urban outweigh the costs, so the proportion of the MD poor is higher in rural areas than for income poverty. That should get the urbanistas going.

Each indicator actually pulls its own weight – for example 10 countries’ poverty was tugged down by significant changes in all indicators. Not one is a laggard that never moves.

Which all seems really important, but as I said, I’m not a stats nerd, and I’d be interested in your views on the value (or otherwise) of the index.

June 12, 2014

Where does power lie in a fragile state like Eastern Congo? What does it mean for aid organizations?

Here’s the last (at least for now) reflection on my recent trip to the DRC.

The roads in DRC are extraordinary; a skeleton-rearranging, dental filling-loosening, vehicle disintegrating nightmare. From now on, when I talk about

Anyone seen the state?

infrastructure and effective states, roads will be top of my list. In the rainy season, trucks charge $1200 to bump and crawl a load of sand the 5 hours from Goma to an Oxfam-run IDP camp near Rubaya (65km). On its return, the truck has to go straight into the garage for repairs that can cost half of that money. That’s no way to run an economy.

A half-way decent state would invest in roads to unleash markets, connect its communities, (and incidentally reduce the damage to my skull from being bashed repeatedly against the car walls and roof), but in the DRC, such enlightened provision of public goods is currently a distant dream. Roads are both a literal and metaphorical point of entry for understanding the role of the state.

But the state is not entirely absent, nor completely predatory (although it extracts an awful lot from people who have very little) and there is certainly no vacuum of power. Here are some of the more obvious ‘poles of power’ (but I’m sure there are many more) whose interaction underlies the current chaos, and which could possibly provide the elements of a better system in the future.

The state: according to one local Oxfam staffer: ‘Yes, the state is predatory but that doesn’t mean we give up, at some levels, at least. It’s like a hamburger, with clean layers on top and bottom, and a dirty layer in the middle. At the top level, ministries will work with NGOs in a non predatory way – they have other, better means of raising cash (minerals, or from the government budget). But at the provincial level, predation is a real issue. At the local level, officials live with communities, so it’s different again. Some local officials really support projects, but everything they do needs sign off at provincial level, so it gets very tense.’

We met one village official (chef de poste) in his ‘office’: tin roof and floor of volcanic rubble; no glass in windows; bare plank walls covered with heavily logoed NGO/UN posters on sexual violence, torture, HIV, land rights, and a hand-drawn map of the area. On his desk, the classic tools of the functionary: a rubber stamp, a mobile phone, and a pile of files and notebooks.

‘The big thing here is peace and security. We get everyone round the table – the Community Protection Committee, traditional authorities, the military, the police. That way the army/police don’t have much wiggle room. Then next meeting we do an evaluation and hold them to account.’

He’s been in post since 2008. He laughs when asked if the state gives him training. ‘we rely on the NGOs for that. They help us with what the law says – don’t torture, don’t lock people up for unpaid debts (mediate instead). There are lots of rights and laws I didn’t know.’

In his world, the state and the customary authorities run by traditional chiefs are totally intertwined. His previous post was as an accountant for the local customary authority, but for him ‘it’s all public administration. The chefferie (traditional authority) collects the taxes. I report to the mwami (traditional leader) as well as the ministry.’

So we head off to meet a traditional leader (next pole of power), on the veranda of his rather smart house at the top of a steep mud path. The quietly spoken traditional chief (chef de groupement) radiates authority, cradling his two mobiles.

Protection Committee awareness raising exercise

‘I’ve been chief for 20 years, my father was chief before me. The state authorities are in charge of roads and bridges, tax is collected from shops, restaurants, markets etc by the chef de cheferie, (next rank above him in the traditional hierarchy). I encourage the population to pay.

I find women lie less when they bring me a problem, so I listen to them more. I meet the army/police on a regular basis. The Oxfam project [on community protection committees] has helped to change them, given them a better understanding of rights and the law and a point of reference.’

There are several other poles of power besides civil and traditional authorities: armed groups, the army, the police, the humanitarian system, faith organizations, civil society organizations, sports clubs etc etc

Sometimes they conflict. Customary law says land belongs to the chief, but official law claims it for the state. The traditional leader wonders if Oxfam would consider campaigning on his behalf? Erm, probably not.

More painfully (if you believe aid agencies should be strengthening the state), listen to Clovis Mwambutsa, Oxfam’s Provincial Coordinator in North Kivu, on the reasons why he left the Ministry of Health to work for the UN and NGOs: ‘I said yes, because in the government the pay is very bad, or doesn’t come at all. You live off the per diems from UN or NGO meetings. If the salaries had been the same, I would have stayed: NGOs can’t solve a country’s problems. A strong government is the only way.’

But despite the contradictions between them, there is something to work with here – numerous centres of power and trust, from which can emerge coalitions for short term change and longer term construction of institutions. Outsiders, be they governments, the UN system or NGOs, can help bring them together (PDIA style) in search of solutions and support efforts to include the voices of the biggest missing element – the Congolese people.

But as currently constituted, the humanitarian system really struggles to do this. Back to Clovis: ‘In other countries we work more with government, but here we have been in a very humanitarian operation, and if you are very operational, and the government is very weak and can’t deliver, you can’t work with it. With more long term programming you can start to engage with government bodies at provincial or national level.’

This is where the siloes need to be broken down. Supporting Congolese, whether in or out of power, to build a new country from the current wreckage involves long term commitments, acceptance of reverses and failures, all built on a foundation of the deepest possible understanding of a complex political and social system. It is neither ‘humanitarian’ nor ‘long term development’, but both, with a big dash of advocacy thrown in.

If that gets sorted out who knows, the roads may even get fixed.

And allow me to change the mood by signing off with the inevitable Pharrell Williams cover, from Goma youth, who are organizing a ‘Happy From Goma’ concert on Monday [h/t Emma Fanning for that]

June 11, 2014

What should we do differently when an ‘emergency’ lasts for 20 years?

Second installment in my reflections on last week’s trip to the Eastern Congo

The classic cliché of humanitarianism is the angel of mercy (usually white) jetting in to help the victims of a sudden catastrophe (earthquake,

Here to stay? IDP Camp, North Kivu. Credit: Maxime Michel

war, hurricane), helping them get back on their feet in a few months and then moving on to the next emergency. A whole structure of funding, organizations, policies and approaches has grown up around that model.

But the Eastern Congo, where I spent last week, doesn’t fit the picture, in that the ‘emergency’ has been going on for 20 years (and counting). People we spoke to had been forced to flee 5 times or more. Once ‘displaced’ in the anodyne language of the humanitarians, they had in turn played host to others fleeing the sporadic violence.

A couple of ideas came up in conversation about how to adjust humanitarian practices for chronic crises of this kind.

If you think of the decision to flee, return and flee again as a cycle (see graphic), it is worth asking whether the attention and resources are properly distributed around it. Traditional humanitarianism concentrates on the right hand side of the cycle – with peacekeeping trying to prevent conflict and flight, and then aid kicking in to receive and care for refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs). [note for nit-pickers perfectionists, this cycle is a very simplified version of a messy reality in which, for example, attacks can occur more or less anywhere on the cycle].

The left hand side – how and when IDPs go home, and what happens when they get there, is historically much less of a focus. UNHCR has a few systems in place to help people get back, but once there, they are largely on their own.

But that is changing in some interesting ways. Firstly (the power of fuzzwords!) numerous people said things along the line of ‘we all have to talk about ‘resilience’ these days, whatever that means!’ One of the impacts of resilience-talk seems to in channelling thinking and cash into prevention rather than cure: strengthening systems of protection and livelihoods for people in order to make it less necessary for them to flee in the first place. Our work with Community Protection Committees falls into this category – I’ve blogged about them before, and found them every bit as inspiring as I’d been told (big sigh of relief).

But that is changing in some interesting ways. Firstly (the power of fuzzwords!) numerous people said things along the line of ‘we all have to talk about ‘resilience’ these days, whatever that means!’ One of the impacts of resilience-talk seems to in channelling thinking and cash into prevention rather than cure: strengthening systems of protection and livelihoods for people in order to make it less necessary for them to flee in the first place. Our work with Community Protection Committees falls into this category – I’ve blogged about them before, and found them every bit as inspiring as I’d been told (big sigh of relief).

Second, working more with various bits of the state and other local institutions, such as traditional authorities (more on that in a future post) makes it easier to help people with the return and difficult first few months of getting re-established (for example if your home was burned down when you fled, or you land subsequently occupied by others). I think the humanitarian system needs to do a lot more on this, but at least it’s a start.

The horrible thing about the cycle is that people’s investments in improving their lives are regularly wiped out by gunfire and flames. Houses are burned down, crops and livestock stolen. Suppose those trying to work with people to help them rebuild assumed this was going to happen again, what might they do differently? For example, maybe the focus should be on building up those assets that are either portable, or unlikely to be touched by armed groups (because they are hard to destroy, like roads, or because the groups themselves have need of them, like water systems).

Things that are already portable include knowledge, skills, self confidence and organizing experience – lots of rights-based work survives displacement, as for example, members of the CPCs emerge as leaders in the camps.

So we could do more of that. But it might also be worth trying to make other assets more portable. For example, cash can be stolen at checkpoints, but

What can people take with them when this happens?

virtual cash, eg via mobile banking, can be hidden. ID cards and other documents can be burned or lost in the chaos of flight. Currently it takes months of bureaucracy and bribes to replace them, during which undocumented IDPs are vulnerable to all manner of extortion and abuse. Are there any ways to ‘back up’ official documents on a mass scale so they can be easily replaced?

Is it a problem if the camps become semi-permanent? Some people flee to the camps, but return after a few months. Others are left stranded, because they do not feel able to return. This leads to fears that the camps themselves are becoming part of the problem – a kind of welfare dependence argument. But the IDPs I spoke to were clear that anyone who is able to go home, will do so: ‘if there is peace, no one wants to live in the camps. Here, we have nothing. At home you are free, you can grow food, there is no hunger, you can pay your kids’ school fees….’ We met people who had lived in the camps for over a decade, which seems neither humane, nor a sensible use of humanitarian aid: another option might be to help IDPs voluntarily ‘graduate’ into host communities after a time-limited stay in camps.

As for the camps themselves, they are more or less permanent, even if the people come and go, and that seems a good thing – they have become part of survival strategies. Congolese know where they can go when disaster strikes; aid agencies can rapidly scale up provision (e.g. Oxfam deliberately builds spare capacity in water systems in areas where we know the next wave of IDPs are likely to go).

Finally, funding based on short-term emergencies rarely exceeds a one year grant, which makes a really lousy fit with long term problems. Staff become expert at trying to put successive short term grants back to back, so they resemble a medium term programme, but it is time consuming and unreliable. All too often, painstakingly assembled teams have to be ‘let go’ if the funding is delayed (as is often the case). We are now starting to see some longer term funding from ECHO and DFID, and elsewhere some multi-year programmes in the response to last year’s typhoon in the Philippines, for example. But the system needs lots more of that if we are to work on chronic crises in anything like an effective manner. I am collecting examples of particularly innovative ‘good donorship’ in expanding time horizons for chronic emergencies like the DRC – do please add any good examples in the comments.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers