Duncan Green's Blog, page 183

August 6, 2014

The Pocket Piketty: a two page intro for non-bookworms

One of my main functions within Oxfam seems to be to review books to spare everyone else the effort. Last week, I was on Piketty duty. Batches of  campaigns and policy types sat in suitable veneration around a copy of the giant tome, and I talked them through this two page ‘Pocket Piketty’.

campaigns and policy types sat in suitable veneration around a copy of the giant tome, and I talked them through this two page ‘Pocket Piketty’.

The Potted Piketty (longer summary here)

From the Introduction to Capital in the Twenty-First Century

‘The distribution of wealth is one of today’s most widely discussed and controversial issues. But what do we really know about its evolution over the long term? Do the dynamics of private capital accumulation inevitably lead to the concentration of wealth in ever fewer hands, as Karl Marx believed in the nineteenth century? Or do the balancing forces of growth, competition, and technological progress lead in later stages of development to reduced inequality and greater harmony among the classes, as Simon Kuznets thought in the twentieth century? What lessons can we derive from that knowledge for the century now under way?

These are the questions I attempt to answer in this book. Modern economic growth and the diffusion of knowledge have made it possible to avoid the Marxist apocalypse but have not modified the deep structures of capital and inequality—or in any case not as much as one might have imagined in the optimistic decades following World War II. When the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of growth of output and income, as it did in the nineteenth century and seems quite likely to do again in the twenty-first, capitalism automatically generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities that radically undermine the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are based. There are nevertheless ways democracy can regain control over capitalism and ensure that the general interest takes precedence over private interests, while preserving economic openness and avoiding protectionist and nationalist reactions……’

From the Review by Paul Krugman

‘It has become a commonplace to say that we are living in a second Gilded Age, defined by the incredible rise of the “one percent.” But it has only become a commonplace thanks to Piketty’s work.

It came as a revelation when Piketty and his colleagues showed that incomes of the now famous “one percent,” and of even narrower groups, are actually the big story in rising inequality. And this discovery came with a second revelation: talk of a second Gilded Age, which might have seemed like hyperbole, was nothing of the kind. In America in particular the share of national income going to the top one percent has followed a great U-shaped arc. Before World War I the one percent received around a fifth of total income in both Britain and the United States. By 1950 that share had been cut by more than half. But since 1980 the one percent has seen its income share surge again—and in the United States it’s back to what it was a century ago.

It came as a revelation when Piketty and his colleagues showed that incomes of the now famous “one percent,” and of even narrower groups, are actually the big story in rising inequality. And this discovery came with a second revelation: talk of a second Gilded Age, which might have seemed like hyperbole, was nothing of the kind. In America in particular the share of national income going to the top one percent has followed a great U-shaped arc. Before World War I the one percent received around a fifth of total income in both Britain and the United States. By 1950 that share had been cut by more than half. But since 1980 the one percent has seen its income share surge again—and in the United States it’s back to what it was a century ago.

Still, today’s economic elite is very different from that of the nineteenth century, isn’t it? Back then, great wealth tended to be inherited; aren’t today’s economic elite people who earned their position? Well, Piketty tells us that this isn’t as true as you think, and that in any case this state of affairs may prove no more durable than the middle-class society that flourished for a generation after World War II. The big idea of Capital in the Twenty-First Century is that we haven’t just gone back to nineteenth-century levels of income inequality, we’re also on a path back to “patrimonial capitalism,” in which the commanding heights of the economy are controlled not by talented individuals but by family dynasties.’

Other Key Points:

Data: Traditionally, discussions on inequality have been based on surveys of random households, but these tend to miss the handful of households at the very top, and only started relatively recently (e.g. 1947 in US). Piketty et al turned to a different source of information – tax records, which are more reliable on the top 1% and go back much further. These are almost all from developed northern economies – developing countries yet to figure much in Piketty debate.

r > g: Piketty’s big claim is that over the long haul, the rate of return on capital (r) exceeds the rate of economic growth (g), except for historical anomalies such as the interwar period of the 20th C, and that we are now reverting to that norm. If he’s right, one immediate consequence will be a redistribution of income away from labour and toward holders of capital.

Inequality and inherited wealth: Krugman: ‘A rising share of capital, in turn, directly increases inequality, because ownership of capital is always much more unequally distributed than labor income. But the effects don’t stop there, because when the rate of return on capital greatly exceeds the rate of economic growth, “the past tends to devour the future”: society inexorably tends toward dominance by inherited wealth.’

Wealth Tax: Piketty ends with a call for wealth taxes, global or at least EU-wide if possible.

Critiques:

The FT’s economics editor Chris Giles: claimed he had discovered crucial errors in the data, which were sufficient to invalidate Piketty’s core arguments. The Economist immediately disagreed with the FT, arguing that its findings did not invalidate the book. Piketty belatedly responded with a full (10 suitably unintelligible pages) rebuttal.

immediately disagreed with the FT, arguing that its findings did not invalidate the book. Piketty belatedly responded with a full (10 suitably unintelligible pages) rebuttal.

James Galbraith: argues that Piketty mixes up apples and pears by lumping together real capital (eg factories and machines), and financial capital, which fluctuates wildly with market bubbles. And that his proposed wealth tax is less likely to work than an increase in the minimum wage (loopholes, clever accountants, offshoring etc)

Paul Krugman: in an otherwise rave review, criticizes ‘intellectual sleight of hand’ in arguing that capital concentration is returning to an inheritance-driven (rather than income-driven) model, when US is still firmly in the income concentration stage.

I’m sure there’s a terribly pun in there somewhere about having your pocket pikettied…. Anyway, that is my last attempt to summarize Piketty, promise. At least until he gets onto doing more work on inequality in developing countries (as he has promised).

August 5, 2014

How did a global campaign bring about a UN Arms Trade Treaty?

The last (but most definitely not least) of the case studies in active citizenship that I have been blogging about over the last couple of months is the inspiring global campaign that  led to the agreement (and impending ratification) of a UN Arms Trade Treaty. It is co-authored with Anna Macdonald, one of the key activists in the campaign. Full case study is here – comments welcome: ATT Case Study final draft July 2014 v2.

led to the agreement (and impending ratification) of a UN Arms Trade Treaty. It is co-authored with Anna Macdonald, one of the key activists in the campaign. Full case study is here – comments welcome: ATT Case Study final draft July 2014 v2.

In October 2003, Oxfam, together with Amnesty International, the International Action Network on Small Arms (IANSA) and many other organisations across the world launched the Control Arms campaign.

The aim of the campaign was to reduce armed violence and conflict through global controls on the arms trade, and the primary objective was an international Arms Trade Treaty (ATT).

In April 2013, a decade of campaigning paid off as the Arms Trade Treaty, the world’s first global treaty to regulate the transfer of conventional arms and ammunition, was adopted by overwhelming majority at the UN in New York, and opened for signature two months later. As of June 2014, the ATT looks set to enter into force around a year after it opened for signature, which will make it one of the fastest ever multilateral treaties to become international law.

Background

Oxfam’s engagement on arms control dates back to advocacy to control arms exports from Europe to South Africa in the early eighties, and the landmines campaign of the 90s. In the late 90s Oxfam and Amnesty International in Europe worked together to successfully advocate for a review of Europe’s arms exports, resulting in the EU Common Position on arms exports.

By the early 2000s, the political environment was propitious. The adoption of the Mine Ban Treaty in 1997 had created confidence that campaigning could achieve change within the arms sector, and many grassroots organisations around the world saw conflict and armed violence as the next big issue.

What Happened?

The ATT campaign developed in three main stages:

1. Winning support for the idea of an ATT 2003-2006: Developing champion governments; building an international popular campaign; growing the coalition and getting the ATT onto as many political agendas as possible.

2. Work at the UN 2006-2009: This led to a greater focus on UN advocacy and focus on global and regional-level meetings.

3. Formal UN negotiations 2009-2013: The establishment of a final timeline for treaty negotiations led to a resurgence of campaigning and advocacy work in capitals and at the regional level, with an increased presence in New York at UN meetings.

Theory of Change

Power Analysis: While there were a handful of governments sympathetic from the outset, and some spillover momentum from the Mine Ban and Cluster Munitions Treaties, there were also strong opponents to the ATT. The USA was the only public “no” voting government at the UN until 2009, when the Obama administration changed its stance, but Russia, China and many Middle East states were also significant opponents. The campaign followed and responded to the shifting tides of government positions through regular exercises in stakeholder mapping. Beyond governments, the National Rifle Association (NRA) and various associated pro-gun groups, predominantly from the US, campaigned against the ATT.

Change Strategy: When the campaign launched in 2003, only 3 governments (Mali, Costa Rica and Cambodia) would publicly associate themselves with the call for an  Arms Trade Treaty. The rest insisted that this ambition was ‘too idealistic”, “unrealistic” and pitted against too many vested interests.

Arms Trade Treaty. The rest insisted that this ambition was ‘too idealistic”, “unrealistic” and pitted against too many vested interests.

The initial strategy therefore was to try and get one government in each region to champion the ATT, the theory being that this would gradually build global support for the treaty, as the countries around each regional champion gradually followed their lead in a snowball effect.

So the early focus was on getting the concept of an ATT onto the political radar in key countries, often achieved by first getting widespread popular support through the “Million Faces” petition and other campaigning activities. By mid-2005, the snowball was rolling: at the Biennial meeting of the UN Programme of Action on Small Arms, 55 states included a positive reference to the need for an ATT.

As work progressed at the UN, power analysis became increasingly sophisticated. States were categorised by their support not only for the ATT overall, but for the inclusion of individual elements within the treaty (e.g. human rights or sustainable development). By 2006 campaign planning involved regularly updating complex spread-sheets colour coded into “champions”, “progressive supporters”, “swingers”, “undecided” and “sceptics”. Put simply the strategy was to work with the champion governments, try to move more of the mainstream and swingers into this category, and to isolate or undermine the arguments of the sceptics.

A key challenge was the constant battle to prevent the content of treaty being diluted. Throughout the process the big tension was between the universalists, who argued that the most important aspect was to keep sceptics such as Russia and China on board and were willing to make concessions in treaty content to do so, and governments like Norway and Mexico plus civil society who argued for a stronger treaty. Major successes for the progressive groups included the inclusion of ammunition within the provisions of the Treaty, relatively strong assessment criteria around international human rights and humanitarian law and references to gender-based violence. Weaknesses included not securing a completely comprehensive scope, and the loss of an explicit reference to sustainable development.

Coalitions and Alliances

The campaign developed a wide range of potential (and sometimes surprising) allies. These included the defence industry, companies who saw themselves as the ‘responsible end’ of the arms industry, and a number of retired generals and ex war correspondents. The campaign also worked with financial investors, survivor organizations (who were always included on UN delegations) and sympathetic fragments of the UN system. While the campaign worked with a few individual faith leaders, (e.g. Desmond Tutu), and the Pope came out in support in 2010, it did not engage with faith organizations as institutions.

The campaign developed a wide range of potential (and sometimes surprising) allies. These included the defence industry, companies who saw themselves as the ‘responsible end’ of the arms industry, and a number of retired generals and ex war correspondents. The campaign also worked with financial investors, survivor organizations (who were always included on UN delegations) and sympathetic fragments of the UN system. While the campaign worked with a few individual faith leaders, (e.g. Desmond Tutu), and the Pope came out in support in 2010, it did not engage with faith organizations as institutions.

Course Corrections: What changed along the way?

The campaign initially focussed on mass public awareness to get the issue on the agenda, but then moved into more specialist areas. The balance of insider-outsider shifted over time. At the beginning it was all outsider. Then there was a phase from 2008-11, where focus became much more weighted to insider, with many campaigners working closely with governments as the UN process got under way. By the time of the final negotiations, a balance of approaches had been restored.

Wider lessons

Change takes time: Tackling underlying causes and/or aiming for a major international agreement doesn’t happen in a neat 3 year business cycle. It is going to need at least a decade of focus and follow-through.

Know your stuff: The coalition published over 50 reports in 10 years on many different aspects of the ATT. Credible research helped coalition members to become seen as valuable issue-experts for governments and the UN, and the research generated quality media coverage and briefings in a multitude of fora all over the world.

Know your people: Getting to know and build relationships with the active officials and politicians in key governments was essential. It’s about knowing the individuals who are prepared to go the extra mile, to work with you, and with whom you can build a real relationship of trust.

Know your system: Equally important was constant power analysis, knowing which groups of governments were the most likely to be progressive, and how different alliances could be developed to lever pressure at different times.

Know your process: Especially in a labyrinthine process like a UN negotiation, it is as important to have process experts as issue policy experts. The use of the “consensus rule” thwarts many a UN process, but can be overcome with good knowledge of procedure and tactics.

To read or comment on previously blogged case studies in this series, go to Community Forestry Rights in India; Campaigning on the US Deepwater Horizon oilspill, Changing hearts and minds on Violence Against Women in South Asia, promoting Women’s Leadership in Pakistan and Nepal, Labour Rights in Indonesia, and Community Protection Committees in DRC

August 4, 2014

Why social entrepreneurship has become a distraction: it’s mainstream capitalism that needs to change

Pamela Hartigan, Director of the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship at Oxford’s Saïd Business School, is having second thoughts about the impact of social entrepreneurs.

The first time I heard the term “social entrepreneur” I thought it referred to business people who liked to party. That was about twenty years ago, when the term was just beginning to surface, said to have been coined by Bill Drayton, founder of Ashoka. Ashoka was the first entity that identified and supported such individuals – innovators with a “bold idea” aimed at changing a system that was at the root of a major social or environmental problem.

Twenty years ago I fell in love with “social entrepreneurship”, its promise, and most of all, the stories of the champions that practiced this approach. They didn’t take “it can’t be done” as a deterrent – in fact, as one of them described to me, “’it’s impossible’ is our clarion call to action”. As the first Managing Director of the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship, an entity supported by World Economic Forum’s founder Klaus Schwab and his wife, Hilde, I spent eight years identifying, celebrating and supporting such individuals, providing them with opportunities to enter the coveted corporate enclave that is the annual meeting of the WEF at Davos – which in turn gave them access to networks of power they had never been able to tap. Many of these social entrepreneurs formed strong and lasting relationships with members of the corporate C suite, heads of philanthropic foundations and the media leaders that attend Davos. It was difficult not to become infected with the bug of “social entrepreneurship”.

The Schwab Foundation certainly was not the only social entrepreneurship organization on the scene. A host of other organizations were created at around the same time, including Echoing Green, the Skoll Foundation, the Omidyar Network, Acumen, Mulago, to name just a few. These were primarily based in the USA, but the UK quickly followed suit along with countries on the European continent, Asia, Latin America, Africa and Australia. Governments, led by the UK, embraced “social enterprise” as the “third way” – income-generating charities that did not depend wholly on public coffers but dealt with the increasing number of social problems that defied government solutions.

The Schwab Foundation certainly was not the only social entrepreneurship organization on the scene. A host of other organizations were created at around the same time, including Echoing Green, the Skoll Foundation, the Omidyar Network, Acumen, Mulago, to name just a few. These were primarily based in the USA, but the UK quickly followed suit along with countries on the European continent, Asia, Latin America, Africa and Australia. Governments, led by the UK, embraced “social enterprise” as the “third way” – income-generating charities that did not depend wholly on public coffers but dealt with the increasing number of social problems that defied government solutions.

My main concern about this viewpoint is that it stripped the notion of innovation and systems change – the essence of social entrepreneurial endeavour – right out of the approach. In the UK and those countries that have followed, social enterprises have become part of the “social enterprise industrial complex”, sub-contractors to government and feeding into a dysfunctional system. But that is for another blog.

The point is, all of a sudden, social entrepreneurship was everywhere and everyone wanted to be one. But there was one question that was raised at every national and international gathering of social entrepreneurs. As former President Bill Clinton noted in a speech about the challenge of school reform “Nearly every problem has been solved by someone somewhere. The frustration is that we can’t seem to replicate [those solutions] anywhere else.” Why is it that the only system-changing approach that has managed to go to scale is microfinance? Yet we forget that it took 30 years and an estimated US$20 billion in subsidies from major foundations and individual philanthropists to transform microfinance from an undefined effort sitting between philanthropy, aid and the market, to something much closer to mainstream investing.

This begs the question as to whether the only way social entrepreneurship will scale is by becoming part of the mainstream market system. As someone who is now working in a business school environment, this idea carries significant weight.

I do believe that transformational systems change will never be achieved on a massive scale by non-profit organizations or even by well-meaning “hybrids”. I very much

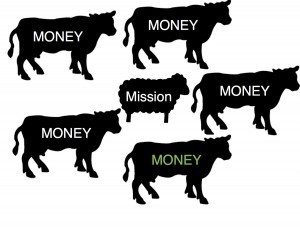

Which needs fixing first?

believe that the way forward is through business. And so I have come to feel increasingly uncomfortable with the term “social entrepreneurship” and its main actor, the “social entrepreneur”.

But the reason is not because I have bought into the notion that capitalism as we now practice it is the solution – but because I firmly believe that every entrepreneur has to be a “social entrepreneur”. The way business has operated in the last 50 years must be disrupted because we will not survive as a society or a planet if we do not tear down the walls that compartmentalise economic, social and environmental activity. That is why I am now working in business schools. The way we approach business education has to change.

There is no doubt that the term “social entrepreneurship” served its purpose at one point in time, mainly because we needed to highlight what type of entrepreneurial practice we were referring to – but today it only serves to further dichotomise entrepreneurial practice into the “social” and the “commercial” (“non-social”?). It creates a false separation between “this is where we make money, and this is where we do good”. And that is EXACTLY what is wrong with capitalism today.

It is hard for us who have been born and raised under capitalism and the large corporation to reflect on the fact that it was only relatively recently – not many centuries ago – that humankind finally began to achieve a surplus, something more than the necessities for survival.

The central precept of all early corporations that began to take shape around the 16th century was that even though they were chartered as private entities and possessed special privileges and monopoly rights, they were still expected to carry out activities with a public purpose. That has changed and needs to be revisited if the world is to advance.

Yep, maybe it is

There is no doubt that the modern corporation as we know it today has empowered individual genius and bestowed great social benefits. Yet it has also done social harm. Many of the ills of modern life – non-sustainable levels of personal and institutional debt, toxic air and water, workplace injury, loss of livelihoods for communities, political bribery – can be traced to corporate lack of responsibility to one or more constituencies. This is not intentional. No one wants to cause poverty, pollution, disease, unemployment and corruption. Rather, they want to make profits. But in that pursuit, they may find anti-social behaviour pays. To achieve profits in the short term, corporations exact a “social and environmental price” and that price is high and rising.

The key to sustainable capitalism is reasonable profits as opposed to maximizing profits. In the current system, a segment of society is trying to maximize profits without concern for the impact on the well being of the society as a whole, while another segment of social organizations have to deal with the fall out. The system is not working.

Fortunately, there are a growing number of people, particularly among the young, who embrace the notion of “entrepreneurship for society” rather than commercial or social entrepreneurship. They are not waiting until they are 50 years old when they have “made their money” and can “give back”. I am optimistic that through the new breed young professionals, we can go back to the future and base our economies on activities that uphold social and environmental goals without eschewing financial sustainability.

August 3, 2014

Links I liked

This week’s top tweets – I’m realizing that the only things that get picked up on twitter are generally visuals. I guess it’s not cut out for the written word (apart from haikus). Click to expand the smaller ones (hard to squeeze them all in).

Gaza (what else?)

I’m just going to look at the media war being played out nightly on our TVs, but if you want to take action, here’s what OxfamGB is suggesting, and here’s a powerful first hand account of working and observing Ramadan under siege from Oxfam’s Arwa Mhana.

How Israeli spokespeople “craft” answers to difficult questions [h/t James Bays]

‘Using a prototype Truth Rectification Processor, the words of Israeli government spokesman Mark Regev have been filtered through a complex algorithm that strips away lies.’ Brilliant idea – could we do this for all official spin doctors? [h/t Tan Gandhara]

I know it’s intrusive, but it’s very moving too (and shows not all official media reps are robotic). UN spokesperson Christopher Gunness breaks down during Al Jazeera interview on the death of 15 children.

Let’s talk money

Last week 65 words caused Argentina’s $29bn default (helped by one eccentric US judge and a flock of hungry vultures)

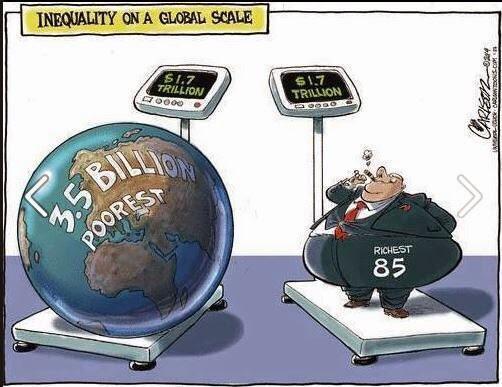

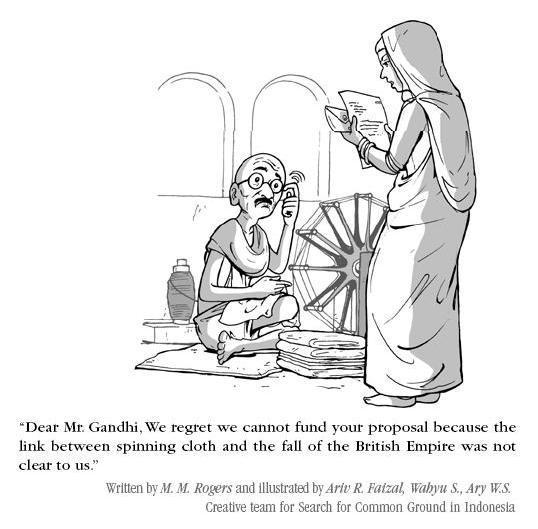

Our best killer fact in years now in cartoon form – you will be seeing it a lot over the coming months [h/t Robert Went]

But why not just write on a dollar bill? Spreading political messages on currency and coins [h/t Makarand]

But why not just write on a dollar bill? Spreading political messages on currency and coins [h/t Makarand]

The State of the State

Is this as good and important as I think it is? ‘The End of the Arab State‘ by former US ambassador to Iraq Chris Hill

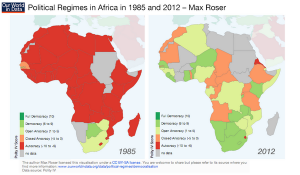

I learned a new word: ‘anocracy‘: Political change in Africa 1985-2012: from autocracy to something better [h/t Nicholas Thompson]

On a lighter note

Dilbert explores management’s warm embrace of innovation and complexity

July 31, 2014

A week in the life of a humanitarian agency (it really is all kicking off everywhere)

To give people a better feel for our humanitarian work in Gaza, Syria and elsewhere, I thought I’d share the contents (unedited, but with a few explanatory links added + pics) of the weekly internal email that drops into Oxfam staff’s inboxes. It summarizes in pithy form what our humanitarian colleagues are up to – I think it captures the unique blend of technical jargon, an obsession with numbers and profound human need that characterizes their (amazing) work:

“EMERGENCIES HEADLINES from around the world, 30th July 2014

HORN, EAST, CENTRAL AFRICA

South Sudan

Oxfam continue to prepare for the possibility of a famine being declared in the coming year in South Sudan but it is still not known when specifically the Integrated Food

Access to water in South Sudan

Security Phase Classification which determines if there is famine will make a declaration on this. The situation however whether there is a famine in South Sudan declared or not, a significant food crisis in South Sudan continues. There will be a small harvest in December in South Sudan that could improve the food security situation but it’s expected that things will sadly worsen in 2015 in terms of food insecurity in the country.

Ethiopia

There are now 175,000 South Sudanese refugees in Ethiopia. In the Tierkidi Camp (previously known as Kule 2) where Oxfam are working there is now 50,000 refugees. Oxfam has so far delivered water to 100,000 people in Kule 1, the Tierkidi camps and Pagak reception centre. Oxfam are also building latrines, doing public health promotion and solid waste management.

SOUTHERN AFRICA

Nothing new to report this week

WEST AFRICA

Ebola virus outbreak

The Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa has now killed 673 people with just over 1,200 cases, making this the worst Ebola outbreak in history. So far it has spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone with it breaking out firstly in Guinea. A Liberian man travelled to Nigeria recently with Ebola, and there is a risk the virus could spread further.

In Sierra Leone Oxfam are distributing leaflets and posters so that people understand how best to avoid Ebola and what they should do if they contract the virus. Oxfam staff are constantly speaking to other agencies to see what we can do to assist in Liberia.

Girl collecting her schoolbooks from Gaza’s rubble

MIDDLE EAST / EASTERN EUROPE / COMMONWEALTH OF INDEPENDENT STATES

Gaza

Monday evening saw one of the heaviest bombardments on Gaza. So far since the conflict began, 1,118 Gazans have been killed and 240,000 people have been internally displaced. This is a massive number considering the size of the Gaza strip and its population. Israel recently ordered all Gazans to leave a 3km buffer zone along the Israeli border. This amounts to 40% of the size of Gaza and will mean more people will be displaced, and now in an even smaller area. Gaza’s only power plant was recently destroyed. This will impact on electricity significantly and therefore Gaza’s water supply and sewage treatment facilities.

Oxfam’s response has so far reached 80,588 beneficiaries. 58,000 of these people have been reached with safe and clean water, and another 15,981 have received food vouchers. The continuous fighting has made working in Gaza extremely difficult but it is hoped if a ceasefire is agreed and holds for a reasonable amount of time Oxfam can scale up its response in Gaza.

ASIA

Pakistan

In Pakistan, there are still 995,000 people internally displaced in North Waziristan with 74% of those displaced are women and children. Oxfam are currently water tankering on a daily basis and so far 195,000 litrs of chlorinated drinking water has been supplied to 9,545 beneficiaries who are residing in schools and the community. The team in Pakistan have also distributed 1,232 hygiene kits to families benefitting 16,016 individuals. Our overall beneficiary number now stands at 28,588.

LATIN AMERICA & CARIBBEAN

Colombia

Oxfam in Colombia is about to respond to a drought crisis that is currently hitting the country. It is estimated that 350,000 families are being affected from three regions: the Caribbean, Andina and the Pacific North (the North West of the country). The phenomenon of El Niño, which is not officially declared, is severely hitting this area and Central American countries like Honduras and Guatemala. Oxfam, together with FAO and UNGRD, will start mapping the livelihood situation in the driest areas in order to start a response to protect livelihoods of the most vulnerable people and to start mitigation actions to alleviate the drought consequences.

LAST WORD

Digital technology in humanitarian responses

Oxfam are increasingly using digital technology such as mobile phones in our humanitarian responses. The use of digital technology to register beneficiaries will improve accountability, improve databases of beneficiaries and make it easier to analyse the data. Oxfam have recently been piloting Last Mile Mobile Solutions (LMMS) technology in the Philippines as part of our response to Typhoon Haiyan. LMMS uses a handheld device to register beneficiaries information, and ultimately produce a bar-coded photo card. When swiped, the card produces the information needed to determine and distribute food and non food items. So far it has been used by 12 agencies in 23 different countries, and it is anticipated that this type of technology will become the standard for beneficiary information.”

July 30, 2014

What could Foundations add to the aid mix? A conversation with the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation

Foundations are increasingly important players in the aid scene, spending the interest and/or capital from monster endowments set up by philanthropists. Some of the  best known (Ford, Rockefeller) have been around for a long time, and as their names suggest, have an American feel – the big Daddy is the Gates Foundation, which spends some $4bn a year (by comparison, DFID spends £8bn ($13.5bn)). But earlier this week I spent a pleasant Chatham House rules evening chewing the fat with a little known, but large (fund of roughly $4bn and rising) British-based outfit, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF).

best known (Ford, Rockefeller) have been around for a long time, and as their names suggest, have an American feel – the big Daddy is the Gates Foundation, which spends some $4bn a year (by comparison, DFID spends £8bn ($13.5bn)). But earlier this week I spent a pleasant Chatham House rules evening chewing the fat with a little known, but large (fund of roughly $4bn and rising) British-based outfit, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF).

I decided to build on Owen Barder’s excellent talk to CIFF’s board a couple of months back. Owen stressed that Foundations have lots of freedoms that conventional aid organizations lack – in particular they can take risks and think long term. But in practice, they are often very cautious, and behave more like the rest of the aid biz (logframes, insistence on illusory levels of certainty on impact etc etc). It’s a curious phenomenon: in government aid ministries, politicians who in their political lives know all about taking risks, seizing the moment after shocks etc, suddenly turn into logframe-obsessed bean counters on arriving at the Ministry. In Foundation land, freewheeling, risk taking entrepreneurs suddenly come over all conservative when it comes to giving away their cash.

Which is a particular shame, because the aid business is in crying need of some risk taking and long term thinking right now. Two examples: systems thinking; and how Foundations could develop new approaches for the rest of the aid sector.

Systems Thinking: aka What do you do when you don’t know what will work?

Real life, societies, politics etc are complex – with so many connections and feedback loops that knowing what will happen when you intervene with a large chunk of money is largely unknowable, and when something does happen, attributing it to your particular project may well be a fool’s errand. Aid needs to rethink its linear, cake-baking approach for such systems, and who better placed than the Foundations to:

Manage aid like a venture capitalist – fund multiple start-ups, knowing that a large percentage will fail (indeed, if you have too low a failure rate, you probably aren’t taking enough risks). What matters is getting better at identifying failure early, and then shifting resources to more successful experiments.

Fund work that responds to shocks and windows of opportunity. Aid thinks (and funds) in terms of continuous change (implement the programme over 3 years; grind out the workshops or the vaccines; measure impact). But change often happens in spikes, linked to disasters, scandals and meltdowns (economic, political, environmental). Foundations could show the rest of us the way by demonstrating how to deliberately fund agility and responsiveness, for example in advocacy around climate change.

Positive Deviance: In large n systems, when you don’t know what will work, an alternative approach is to stop, look around and identify the positive outliers. Then go and research why they are doing so well, tell everyone your findings and maybe see if they could be the basis for some useful programming.

Enabling Environment: you may not know precisely what works, but you can create an environment that encourages good stuff: healthy, educated people are more likely to do well than sick, uneducated ones; legal systems that respond to poor people; access to credit; respect for rights. These may not be as easy to sell to the public as bednets, vaccinations or water points with your logo on them, but Foundations don’t have to worry about that – they’ve got enough money already.

Go on, take some risks….

Role of Outsiders

The aid business is in serious need of new thinking in a range of areas where Foundations could be ideally placed to help

Counting What Counts: Measuring impact, thinking through causation and attribution etc are essential to learning and getting better. But we need to ‘count what counts’ – if you are interested in women’s empowerment, better to try and develop ways to measure that directly, even if they are time consuming and expensive. Foundations could invest in developing those methodologies.

Long term funding: lots of change processes take decades, but aid funders typically have short time horizons of 3 years or less. That reduces the space for experimentation, learning from failure and getting it right and pushes aid organizations towards the safe (if unoriginal) bet. Some of the most interesting programmes I’ve seen in Oxfam have come from organizations like the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation taking 10 year time horizons. Could Foundations develop the business models for long term funding?

Picking high risk, unpopular issues: Foundations don’t need to court popularity, or to worry about bad headlines. So they could tackle the politically difficult stuff (safe abortions, migration). They could do the boring-but-important (building statistical capacity). Or they could tackle those Cinderella issues I go on about at regular intervals (road traffic accidents, tobacco, obesity, alcohol).

Will Foundations step up on any of this? Hard to tell, but one thing is certain: in the end it will all come down to the political economy of the donor, as it always does. But in this case that is easier to pin down – it’s the attitudes and incentives of a handful of people on the Foundation’s board and senior management. Get the theory of change write to influence them, and it’s game on.

July 29, 2014

International Aid and the Making of a Better World: a great new book

Ros Eyben makes retirement look terribly exhausting. No sooner had I reviewed her book on feminists in development organizations than another appeared. This one is a  little (170 page) gem. International Aid and the Making of a Better World interweaves her own life story with the evolution of the aid system, in which she is both a participant and a ferocious critic.

little (170 page) gem. International Aid and the Making of a Better World interweaves her own life story with the evolution of the aid system, in which she is both a participant and a ferocious critic.

And although it recounts her battles and probably takes down her enemies in the traditional style of a political autobiography, this book takes real risks in ‘connecting the personal to the system’, charting her course from posh ‘aid wife’ complaining about the servants in her letters home, to born-again feminist and career aid worker (rising to be DFID’s chief social development adviser in the 1990s). From there, with growing disillusionment with the aid system, she headed for IDS and now so-called ‘retirement’.

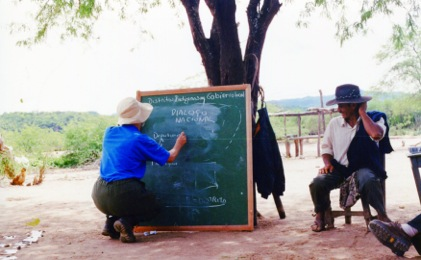

‘The author instructing the Guarani community about how to hold the state accountable’

The personal account is riveting – pieced together from letters, journals, and illustrated with grainy black and white photos of parties on the verandah in Zaire, all discussed with an unflinching gaze that examines both her failings and triumphs.

Just as her life evolves, so does the aid system within which she is increasingly embedded, and the book provides an excellent introduction to the shifting fashions and priorities as aid goes from Cold War to neoliberal peace, with excursions into civil society, rights, resilience, results and any number of other fuzzwords. All illustrated with telling vignettes of field visits and project disasters, and some brilliant background to the structure of the aid industry. Take this on ‘what is a project’:

‘The project is a device that development agencies use to organise complex reality into a manageable, bounded unit. In 1966, Hirschman referred to them as ‘privileged particles of the development process’. Back then, in addition to providing Third World governments with ‘manpower’ for health, education and other services along with some budget support, international aid provided infrastructure projectised in the same manner as the construction of roads, bridges,etc. back home. In theory, recipient governments presented fully designed projects for funding and the aid agency then appraised their viability and relevance. In practice, aid agencies, equipped with budgets that had to be spent in a timely manner, actively encouraged recipients to think of useful schemes that fitted the project paradigm. A project was seen as a capital investment, which was then (in principle, often not in practice) maintained by the recipient government. Early projects produced something concrete – such as a power station or hospital – but by the 1970s the United Nations specialised agencies were using the project model for an expanded range of objectives, such as the ILO Youth Training Centres Project that gave me my first job as a development professional. Although by then aid agencies perceived development as more complicated than initially thought and needing more than bridges and roads, the project had become the default aid instrument. It produced the patent absurdity of a single management structure, budget and determined time frame for ambitious and nebulous concepts such as meeting basic needs through integrated rural development. Yet, external support to development at the local level without projects had become inconceivable. Development professionals, including anthropologists like me, had to work within this framework.’

Come on in….

She revels in exploring the dilemmas and quandaries (the notorious Nairobi swimming pool is a case study, and even warrants a photo).

From the upper echelons of DFID Central, she headed for its office in Bolivia and then off into academia, where she charted the double life (‘subversive accommodation’) of aid workers, riding the waves of chaos and complexity, and then reporting back to HQ on the basis of nice linear plans and logframes (of which she was an initial proponent). She led the criticism of the ‘results agenda’ (even if she did come off worse in a head to head with DFID measurement gurus).

Her big conclusion from her life in aid is the importance of ‘relexivity’, a process of those in aid agencies recognizing their own power and impact on those around them and cultivating ‘a process of deliberately making myself feel insecure about how I understand, speak about and behave in relationships with others.’

Reflexive practice, she argues, begins with looking in the mirror, but also ‘cultivating marginality’ – stay on the outside of the power structures within the aid system, seeking ‘the gift of being on the edge’. Focus on history and relationships, not ‘best practice’. Learn through dialogue and at all times, everywhere ‘become aware of power.’

She remains painfully honest ‘I am still struggling to understand my own motives and why for so long I have wanted to do good somewhere else that at home.’

A fantastic book.

July 28, 2014

Four ways in which a good theory of change can help your social accountability work

This piece went up last week on the World Bank’s Global Partnership for Social Accountability blog. Sorry, I mean ‘knowledge platform’.

Theories of change (ToCs) are a bit of a development fuzzword at the moment, used in lots of different and sometimes baffling ways. But Oxfam finds ToCs extremely  useful, provided they address issues of power and politics, avoid linear ‘logframe on steroids’ or exclusively technical approaches, and embrace the messy realities of the world in which we are trying to support the search for social accountability. Here are four ways in which they can help.

useful, provided they address issues of power and politics, avoid linear ‘logframe on steroids’ or exclusively technical approaches, and embrace the messy realities of the world in which we are trying to support the search for social accountability. Here are four ways in which they can help.

Exploring the context, going beyond your assumptions and spotting new possibilities: Before jumping into ‘what do we do?’, a good ToC starts with deep observation of the political or social system in which you are working: broad stakeholder analysis, understanding of power (both formal and informal), the coalitions (actual or potential) that drive or block change, the windows of opportunity that might arise. This is particularly helpful when operating in systems very different from the ones you are used to (eg staff from stable democracies working in one party systems or fragile states).

Power Analysis is at the heart of Oxfam’s theory of change work. Power is the invisible force field that connects (and divides, and excludes) individuals, households, communities and nations. It is in constant flux, endlessly renegotiated, whether in a progressive or regressive direction. Tools like stakeholder mapping, and thinking about both formal and informal power, reveal an ecosystem of power spreading well beyond the ‘usual suspects’ of SA work (citizens’ groups, the state). In Tajikistan, a brief mapping of village-level relationships added religious leaders, teachers, doctors, truck drivers and others (including officials’ lovers!), greatly expanding the possibilities for building progressive alliances.

Power analysis also explores the incentive systems that operate within the political economy. In Vietnam, a league table approach has proved influential in encouraging accountability at municipal level – no-one wants to be bottom of the league.

Beyond technical fixes: All too often, SA can get stuck in an infatuation with IT and access to information. In Tanzania, the innovative Twaweza programme has stepped back to ask why these were not enough to trigger citizen demands for better performance from the state – the answer seems to lie in a deeper exploration of power and incentives. Power analysis also helps SA programmes get beyond ‘supply’ (training officials) or ‘demand’ (supporting protest movements). Often progress lies in brokering conversations between the two, bringing in other players identified by power analysis, and creating the spaces in which searches for common solutions can emerge.

Embracing Complexity: Real life is messy: change is unpredictable and rarely conforms to the project plan. Surfing the waves of events in a complex system requires different ways of working to grinding through the plan, but has enormous potential. A few examples

Positive Deviance: rather than assume you have to develop innovative ideas, why not spend some time finding the ones that already exist? In Eastern DRC, Oxfam staff began research on security sector reform and civilian security by identifying outliers – which army command posts appeared to be more respectful of civilians than others, and then researching why that might be.

Multiple parallel experiments: if you don’t know what will work, why not try several different things at the same time, like a venture capitalist funding start ups? In Tanzania, Oxfam’s Chukua Hatua project employed an evolutionary approach of variation, selection and amplification in its governance work in two provinces: start 7 or 8 different governance projects in parallel, sit down with partners after 9 months and agree which were most successful, then scale those up (with some new variations to add to potential learning).

Multiple parallel experiments: if you don’t know what will work, why not try several different things at the same time, like a venture capitalist funding start ups? In Tanzania, Oxfam’s Chukua Hatua project employed an evolutionary approach of variation, selection and amplification in its governance work in two provinces: start 7 or 8 different governance projects in parallel, sit down with partners after 9 months and agree which were most successful, then scale those up (with some new variations to add to potential learning).

Iteration and course corrections: In complex systems, you need to ‘cross the river by feeling the stones’. Call regular time outs in any programme, perhaps with an external facilitator, and encourage staff and partners to be as honest as they can about what is working, and what isn’t. Then think about ‘course corrections’ to the work.

Windows of Opportunity: Change is seldom smooth – windows of opportunity open and shut, often around events, whether foreseeable (elections) or unpredictable (shocks, scandals, sudden changes of leadership). Yet too many project plans chart an illusory world of steady state ‘roll out’ of training, capacity building, campaigns etc. Preparing for windows of opportunity, spotting them as rapidly as possible, and reacting can greatly improve the impact of SA work, (while presenting management challenges to avoid hopping from one issue to another in an entirely unfocussed way!)

July 27, 2014

Links I liked

Highlights from last week’s tweets (and more displacement activity for Monday morning). Follow @fp2p if you want the rest, including piles of much more worthy and serious development type stuff

No hat tip to Ian Bray for circulating this, or to those of you who ‘favorited’ it on twitter. Sleep with one eye open, people….

The Weekly Piketty (and a question for readers – what’s the best one page summary of the book itself, and of the rebuttals, and rebuttals of the rebuttals?)

So is global inequality rising or falling? This useful summary explains the apparently contradictory arguments and stats

Interesting Piketty review by Stephanie Flanders (former BBC economics editor, now kerchinging it at JP Morgan). She agrees with him on rising income inequality, but is more sceptical on his claims on wealth.

Some Oxfam Stuff

If you missed Undercover Boss with Oxfam GB’s CEO Mark Goldring stirring poo, rattling tins etc, or saw it and want to enjoy the wig one more time, watch here.

Check out ‘Unleash your inner David’. Powerful (and somewhat frenetic) new campaign video (3m) from Oxfam America

Other Stuff

A wonderfully forensic rebuttal of the legal justifications for Israel’s attacks on Gaza

A great question from the invariably interesting ‘Campaign for Boring Development’: shouldn’t humanitarian aid come first in the queue for cash? It’s popular with politicians and the public, undoubtedly saves lives etc. In contrast, aid for long term development is less popular (especially with the Daily Mail) and its impact is much more contested.

By 2030, the death toll from traffic accidents outside rich countries is projected to rival that from HIV/AIDS (around 2 million) [h/t Conrad Hackett]

Girl Summit miscellany

Nigeria’s political elite is much more culpable than Boko Haram for letting down Nigeria’s girls, argues Exfamer Kevin Watkins, now ODI’s boss.

Women’s rights country by country – nice interactive graphic from the Guardian. It covers laws and institutions rather than real life, but still useful

And finally, Girl Rising’s simple, brilliant, short (1m) and inspiring video on girl’s education

July 24, 2014

The new UN Human Development Report on vulnerability and resilience: ignoring trade-offs and an epic fail on power and politics

I started off reading the exec sum of yesterday’s Human Development Report (UNDP’s flagship publication) with initial excitement, followed by growing dismay. It’s a  pretty traditional kind of disillusion (I’m a bit of a connoisseur). Allow me to walk you through it.

pretty traditional kind of disillusion (I’m a bit of a connoisseur). Allow me to walk you through it.

In a nutshell, an interesting diagnosis and a few good new-ish ideas, followed by a pretty thin proposal for anything resembling a cure, while ducking most of the tricky questions. Recognize the pattern?

Let’s start with the positive. First a good topic: vulnerability and resilience – development fuzzwords that really need examination, clarification etc, in the way the HDR is usually good at.

Despite recent progress in human progress, the report correctly identifies an underlying malaise: ‘a widespread sense of precariousness in the world today—in livelihoods, in personal security, in the environment and in global politics.’

‘Real progress on human development, then, is not only a matter of enlarging people’s critical choices and their ability to be educated, be healthy, have a reasonable standard of living and feel safe. It is also a matter of how secure these achievements are and whether conditions are sufficient for sustained human development. An account of progress in human development is incomplete without exploring and assessing vulnerability.’

Some of its useful contributions:

Some of its useful contributions:

It proposes a pretty broad conception of ‘human vulnerability’ (presumably to sit alongside the UNDP’s traditional focus on human development), and breaks it down a bit between groups (see first diagram).

It raises the possibility of some kind of multidimensional approach to inequality, pointing out that inequality in healthcare has fallen, whereas disparities in income has risen, while inequality in access to education has stayed roughly constant in recent years.

It points out that the rate of progress in human development has fallen significantly since 2008 (see bar chart).

It highlights the need to think about vulnerabilities in terms of life cycles. People’s vulnerabilities and strengths are cumulative and path dependent. That begins even  before birth – babies born to undernourished mothers are less likely to do well in school or later life. Unemployment in youth can derail people for a lifetime.

before birth – babies born to undernourished mothers are less likely to do well in school or later life. Unemployment in youth can derail people for a lifetime.

The logic of this is ‘intervene early’ (see 3rd graph), but this is where I started to get frustrated. The obvious response is, ‘OK, but money doesn’t grow on trees (OK technically it does, in the case of paper money, but you know what I mean). What are you suggesting you do less of? Take money from pensions and spend it on early childhood development’? The nearest it gets to this is saying ‘Spending on health, education and welfare that increases over the life course does not nurture and support capability development during the crucial early years.’ That sounds like a recipe for a spectacular wonkwar between Save the Kids and Helpage, but as far as I can see, the report ducks the potential trade offs entirely.

Similarly it argues for a return to full employment as an economic policy objective. That’s a brave and radical proposal, but fails to acknowledge, let alone discuss, any possible trade-offs between full employment and decent jobs – it wants both (natch).

Similarly it argues for a return to full employment as an economic policy objective. That’s a brave and radical proposal, but fails to acknowledge, let alone discuss, any possible trade-offs between full employment and decent jobs – it wants both (natch).

Finally, where’s the politics? I know it’s hard for UN bodies to talk about power and politics, but this is a pretty dismal example of a technocrat’s charter, assuming a benign, pro-poor government keen to improve (that’s a hell of a big can opener).

‘Building human resilience requires responsive institutions.. in particular states that recognize and take actions to reduce inequality among groups are better able to uphold social cohesion and prevent and recover from crises.’

And what do you do if you have a state that isn’t this kind of paragon? Complete silence: the executive summary (which is all most people read) doesn’t go there. No discussion of how non state actors can influence states, of how to shift incentives, build coalitions with sympathetic fragments within the state, seize the political opportunities provided by disasters (very important in this case). Likewise, no discussion of the politics of ‘turnaround’ – when and why have bad states turned good? There’s a page in the full report (106) on the role of civil society activism and participation, but that doesn’t make it into the exec sum. All in all, an epic fail, epitomized by the widespread use of what Robert Chambers calls the ‘passive evasive’ tense ‘greater efforts are needed’ etc etc.

My heart rose briefly when I saw a subhead saying ‘Deepening progress and collective action’. Great, here comes an edgy section on how change happens in real political systems. Oh, wait. ‘Collective action’ turns out to mean loads of governments agreeing some really kickass post 2015 goals. Don’t get me started on that one.

Now I’m a big fan of the UNDP (and they are more than welcome to set me straight). Maybe this is as far as an official UN report can go, but if so, that’s a shame. And it rather illustrates just how hard it is to talk about power and politics, even for NGOs. But that’s a topic for a future post.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers