Duncan Green's Blog, page 181

September 4, 2014

What are the strengths and weaknesses of a human rights approach to development?

Confession time, with a dash of heresy. I have mixed feelings (and a fair amount of confusion) about the whole ‘rights based approach’ to development. First, it has a lot going  for it. The human rights framework is:

for it. The human rights framework is:

precise: it sets out clearly who has obligations and duties and who has not, and what those obligations and duties are.

practical: it provides states with a formal language they can use to negotiate and co-operate with one another.

binding: when governments ratify human rights agreements, they accept a formal duty to implement the commitments they have thereby made.

The work of the Olivier de Schutter, the UN’s outgoing special rapporteur on the right to food, demonstrates what can be achieved.

On a more human level, I have many times seen how understanding that they have rights can be a life-changing ‘lightbulb moment’ in people’s lives. I used to airbrush out all the comments to the effect that ‘it was the gender/farmer/child rights workshop that changed my life’ because somehow it felt too convenient and cheesy, but when a campaigner in Bolivia took me aside and said ‘it was ILO Convention 169 that changed my life – when I read it, the indigenous part of me woke up’, I got over my scepticism.

A rights-based approach also encourages personal agency – poor people are citizens, at the core of progressive change, not ‘beneficiaries’ waiting helplessly for whitey to ride to the rescue.

A rights-based approach also encourages personal agency – poor people are citizens, at the core of progressive change, not ‘beneficiaries’ waiting helplessly for whitey to ride to the rescue.

But its multiple uses – from courtroom haggling to spiritual awakenings in Bolivian shanty towns, are both a strength and a weakness. According to Oxfam’s Joss Saunders, to whom I defer on all things legal (and most other things as well), the word is used in at least three ways: legal rights, moral rights or claims and as a language of debate, in which new and old rights are contested and sometimes accepted.

The trouble is that campaigners often fail to distinguish which meaning they are using, and everything acquires the halo of a legal right. Superficially, that sounds like a good thing, but there are at least two downsides: legalizing rights means handing a lot of the work (and power) over to lawyers – the language rapidly becomes legalistic and remote, the struggles arcane and unengaging, and if you legalize incorrectly, you are setting yourself up to lose cases.

The other downside is that, done badly, a rights approach leads to what the Latin Americans call ‘revindicalismo’ – citizens issuing an endless list of ‘demands’ to ‘duty bearers’, usually governments. That can lead to a deeply polarized, oppositionalist approach, which doesn’t always produce results – sometimes it’s more effective to get state, citizens and other non-state actors in a room to work together to solve society’s problems. I’m not sure rights language helps in that effort, at least when it is crudely applied.

Then a recent conversation with some University of Toronto students raised a further issue: the link between rights and systems thinking. If you see the world as made up of complex systems, does a rights based approach help or hinder your work?

My gut feeling is that a rights-based approach can help (but I’m not sure it always does). In a complex system, you steer by having a final destination in

So which of these are legally binding then?

mind, but navigating through rules of thumb, rather than long lists of best practice guidelines. My favourite example is the US marines, who reportedly enter combat with three such rules – stay in contact, take the high ground and keep moving. A rights framework can serve a similar function for activists and aid workers, acting as a compass to help them steer through the messiness of reality – what are the rights involved in this situation? Whose rights are being violated? Will the intervention strengthen their exercise? I would add the distribution/redistribution of power as an equally useful rule of thumb in most cases.

Over to you – what are the strengths and weaknesses of a rights based approach?

September 3, 2014

Amartya Sen on dangers of climate change ‘obsession’ and nuclear power and need for a new ethics of environmentalism

Amartya Sen has an important piece out in the New Republic magazine, on the links between environment and development. It’s quite long, so I thought I’d offer my precis service. He argues that the attention to climate change is disproportionate, not because we should think less about it, but because we should worry a lot more about other environmental issues, particularly poor people’s access to energy. He particularly dislikes the way the nuclear industry is using concerns over climate change to come back from the dead.

to climate change is disproportionate, not because we should think less about it, but because we should worry a lot more about other environmental issues, particularly poor people’s access to energy. He particularly dislikes the way the nuclear industry is using concerns over climate change to come back from the dead.

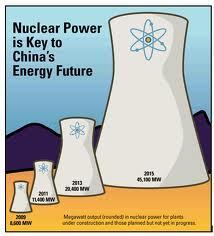

It’s the kind of significant, lofty piece that he excels in. He identifies two big problems: ‘Despite the ubiquity and the reach of environmental dangers, a general normative framework for the evaluation of these dangers has yet to emerge. Second, a much more specific problem: the failure to develop a framework for assessing the comparative costs of different sources of energy (from fossil fuels and nuclear power to solar and renewable energy), inclusive of the externalities involved…. One of the externalities—the evil effects of carbon emission—has received enormous attention, which in its context is a very good thing, but there are other externalities that also demand our urgent attention. These include the growing danger from the rapidly increasing use of nuclear energy—in China and India especially…. The dangers of nuclear energy have received astonishingly little systematic attention in scientific and policy discussions.’

On nuclear:

‘There are at least five different kinds of externalities that add significantly to the social costs of nuclear power: the possibly huge effects of nuclear accidents (as in Chernobyl and Fukushima); the risks of terrorism and sabotage (a strong possibility in countries such as India); the consequences of possible nuclear theft (a potential everywhere, but particularly strong in less well-guarded plants); the difficulties in safely disposing of nuclear waste (which will grow over time cumulatively and possibly quite swiftly if the world comes to rely more and more on nuclear power); and nuclear reactions that may be set off if and when a nuclear power plant is bombed or blasted with conventional weapons in a conventional war, or even in a rather limited local skirmish.’

Smart move (& getting smarter)

On solar:

‘An alternative that seemed very small in possible use only a few years ago, but which is coming into more and more serious consideration now, is renewable power through using solar energy, wind power, and the power of waves. Recently the costs of these renewable sources of energy, particularly solar, have been falling very fast—quite a bit faster than was expected. This has happened rapidly in China, helped by technological innovations but also by governmental subsidies to the solar-panel industry. This has influenced the costs and benefits of solar energy outside China as well—quite substantially, for example, in India, mainly through the cheaper costs of imported Chinese solar panels. America and Europe have tended to keep out the cheaper—and heavily subsidized—Chinese panels mainly in the interest of their respective “domestic” solar-panel industries.’

On how we think about the environment:

‘There is a need for greater clarity in deciding on how to think ethically about the environmental challenges in the contemporary world. Focusing on human freedom—including our freedom to think about what responsibilities we have—along with our interest in our own quality of life can help in this understanding, and shed light not only on the demands of sustainable development, but also on the content and relevance of what we can identify as “environmental issues.”

The environment is sometimes seen—simplistically, I believe—as the “state of nature,” including such measures as the extent of forest cover, the depth of the ground water table, the number of living species, and so on. It is tempting to go from there to the conclusion that the best environmental planning is one of least interference, of leaving nature alone. This approach is deeply defective.

The environment is not only a matter of passive preservation, but also one of active pursuit. Even though many human activities that accompany the

But shouldn’t be?

process of development may have destructive consequences (and this is very important to understand and to address), it is also within human power to enhance and improve the environment in which we live. Indeed, our power to intervene, with reason and effectiveness, can be substantially enhanced by the process of development itself. For example, greater female education and women’s employment can help to reduce fertility rates drastically, which in the long run can reduce the pressure on environmental destruction, including global warming and the decimation of natural habitats. Similarly, the spread of school education and improvements in its quality can make us more environmentally conscious. Better communication and a more active and a better informed media can enhance our awareness of the need for environment-oriented thinking. It is easy to find many other examples of interconnection. In general, seeing development in terms of increasing the effective freedom of human beings brings the constructive agency of people in environment-friendly activities directly within the domain of developmental efforts.

He concludes by proposing four ‘broadenings of our vision’:

‘First, if the fulfillment of our human existence lies not merely in our living standards and need-fulfillment, but also in the freedoms that we enjoy, then the idea of sustainable development has to be correspondingly reformulated. We must think not just about sustaining the fulfillment of our needs, but more largely about sustaining, and extending, our freedoms (including, of course, the freedom to meet our own needs, but going well beyond that). The sustaining of ecosystems and the preservation of species can be given new grounds by the recognition of human beings as reflective agents rather than as passive patients.

The second broadening concerns the extension of public reasoning from the tendency to appeal to people’s self-interest to explicit recognition of the need to take into account the interests—and the freedoms—of future generations. Many changes have occurred in the past by the force of new reasoning, whether it be the unacceptability of slavery or untouchability, or the need for social safety nets for the underprivileged, or the right to medical attention seen as a social entitlement for all. The battles have not been easy, and the one on sustainable development will need engagement and political commitment.

The third broadening is the need for the enlargement of scientific focus from mere avoidance of dangers to the positive possibilities of enhancing human choices and freedoms, and for avoiding the biases in environmental thinking that have come from an overconcentration on the richer parts of humanity, and the comparative neglect of research that can expand the generation, storage, and efficient use of environmentally safe energy, particularly in poorer countries, including those in the tropics. In thinking about expanding human freedom today and sustaining it in the future, we have to take fuller note of the need for greater energy use for a large number of deprived people in the world.

Finally, as far as the avoidance of dangers is concerned, there is an urgent need for moving from any one-dimensional priority to facing the multifaceted threats that environmental dangers pose. It is odd, for example, that the possible negative effects of nuclear energy have figured much more in public fear than in scientific attempts to provide an assessment.’

September 2, 2014

‘Beyond our two minutes’: which international bodies are good/bad at consulting civil society organizations?

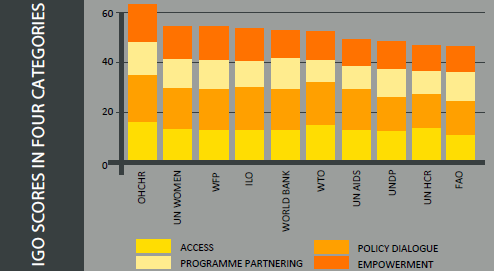

Ah yes, death by consultation, the fate that awaits all NGO policy wonks. The international civil society alliance CIVICUS has published ‘Beyond Our Two  Minutes’, a useful new report trying to assess the efforts of intergovernmental organizations (UN, World Bank etc) to engage with civil society.

Minutes’, a useful new report trying to assess the efforts of intergovernmental organizations (UN, World Bank etc) to engage with civil society.

It’s a pilot project, developing a scorecard to test IGO engagement and produce a league table to name and shame the laggards, and offer some praise (suitably grudging, I trust) to the leaders. They decided to focus on four areas:

‘1. Access: Civil Society Organization (CSO) access to the main decision-making body of the IGO. We developed a set of questions to assess how proactively the IGO facilitates civil society engagement within its core decision-making body, as opposed to just at the programmatic level. In doing this we evaluated accreditation mechanisms which have been widely used by IGOs to regulate civil society participation within decision-making structures.

2. Policy: Engagement by the IGO with the CSOs in policy dialogue. We developed a set of questions to assess the extent and the stage at which an IGO engages civil society in policy development.

3. Programmes: Engagement by the IGO with CSOs in programmatic development. We developed a set of questions to assess whether civil society feels the IGO simply views them as implementers or contractors.

This?

4. Empowerment: Empowerment of the CSO by collaborating on relevant IGO initiatives that mattered to the CSO. We developed a set of questions to assess whether the IGO makes an attempt to empower the CSO, for example, by working with the CSO on initiatives that it cares about, beyond programme partnering.’

They then asked CSOs to fill in survey questions about their experiences with ten IGOs, and interviewed staff from the IGOs about their experiences working with civil society. 462 CSOs responded, but as the report points out, that is just a fraction of the population: ‘Global governance has undergone an incredible transformation over the past 20-30 years. Where once IGOs had to justify the inclusion of CSOs in their work, today it is the exclusion of CSOs that requires justification. From less than 100 CSOs in 1950, today about 3,900 CSOs have consultative status with the UN.’

Civicus summarizes its key findings as:

• Obstacles: The three most commonly identified obstacles were member states overriding CSO voices, consultations that had no outcomes and weaknesses in the outreach mechanisms of IGOs.

• Priorities: The three priorities that ranked highest were greater focus on local or regional outreach, greater focus on identifying appropriate

Or This?

interlocutors to reach different types of CSOs and decentralised CSO outreach strategies.

• Access: CSOs reported that IGOs were overly selective in choosing whom they sought to engage, not proactive enough in reaching out to civil society and provided weak access to the main decision-making body of IGOs.

• Influence on Policy: CSOs reported not feeling listened to on policy issues, and a major obstacle identified was organisation of dialogues without tangible outcomes.

• Programmatic Delivery: A slight majority of CSOs felt that IGOs were only interested in them for their ability to deliver programmes and projects, though a large minority did not strongly report this complaint.

• Empowerment: CSOs were quite split on the extent to which IGOs actively sought to strengthen them and collaborate with them on initiatives that matter to CSOs. This speaks to different experiences across various IGOs. Some CSOs have had positive experiences at some IGOs, others much less so.

The final league table is buried on page 70, but here it is:

the UN agencies manage to come both top (Human Rights, Women) and bottom (Refugees; Food and Agriculture), with the rest somewhere in the middle.

Two final points: these rankings may reflect the world views of the CSOs working on these issues (are human rights activists generally more positive about multilateralism than food and ag people?). And the paper does not touch on a rather important point – why should IGOs consult with unelected CSOs in teh first place? My take on that is that CSOs have no absolute claim to legitimacy (certainly compared to elected governments), but (especially when democratic processes are flawed) IGOs should indeed be triangulating by consulting with a range of stakeholders, including civil society, but also private sector, faith groups, academics etc.

Civicus is asking for feedback on this initial effort, so could any indexistas out there please give them a hand by commenting?

September 1, 2014

Are progressive cities the key to solving our toughest global challenges?

Hugh Cole, who supports Oxfam’s country teams in influencing at national level, wonders if we’ve missed a trick by focusing too much on nation states

Given the growing size, number and importance of big cities and their often unique politics, should Oxfam be doing more to work with/on progressive cities to make progress on big global challenges where the global or national solutions are stuck or moving far too slowly (think climate change, tax havens, trade)? And what might this look like?

There are some really interesting examples out there. Here’s a few of them.

In South Africa the Western Cape government, at the time the only provincial government run by an opposition party, was the first administration to start tackling HIV and AIDS head on, while the Mbeki-led national government was still in denial. The opposition controlled city of Cape Town was the centre of this health policy revolt, with a combination of health worker activism, growing disgust with the national government’s position, civil society campaigning (e.g. TAC) and (probably) a dash of political opportunism precipitating some bold decisions. In 2000 the Western Cape Government introduced free Mother to Child Transmission

HIV awareness campaign, Cape Town

treatment and later that year a delegation went overseas to investigate bringing antiretroviral (ARV) drugs into South Africa for use in Western Cape hospitals. The roll out of free ARV treatment started soon after. This helped to build pressure and deal with objections/myths about treatment. The national government started providing ARVs two years later, after losing a Constitutional Court battle with TAC.

Michael Bloomberg, the former Mayor of New York, is an example of mayoral activism on a global issue – climate change. In 2007, Bloomberg set a goal to slash citywide emissions 30% by 2030 through a number of initiatives, such as requiring hybrid taxi cabs, building bike lanes and retrofitting municipal buildings. At the end of 2013 he announced that New York’s emissions had dropped by 19% since 2005, putting the city nearly two-thirds of the way to meeting its goal. In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, Bloomberg, an independent, endorsed Barack Obama in the presidential campaign citing the need for action on climate change. All this in a country which has been a spoiler in the international climate negotiations and where leading politicians have referred to climate change research as ‘snake oil science’ (yes it was Sarah Palin – 10 points). In 2005 Bloomberg played a leading role in setting up the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, an international group of mayors dedicated to tacking climate change. On being appointed by UN Secretary General as a special envoy for climate and cities Bloomberg said, “Cities account for more than 70% of global GHG emissions and two-thirds of the world’s energy use today, and their total population is projected to double by 2050″. The city and its former mayor are an interesting example of what might be possible in a city even when national political and economic conditions are hostile.

A less well-known, and unintentional, example from South Africa. Before 2001, all water actually consumed had to be paid for, since the new democratic national government only committed itself initially to provide access to water (i.e. infrastructure). But the eThekwini Metro Municipality (Durban – 3rd largest city in SA) could see that this policy was not working. Poor township and shanty town dwellers could not pay for water and were either being ripped off by private suppliers or were finding ways to get it illegally – including by breaking existing infrastructure. The municipal water department did bottom up consultation on minimum water needs and decided to provide 200 litres (a drum) per day per household for free. The success of this approach

Hybrid taxi in New York City

was noticed by national government (perhaps it was making them look bad?) and in 2001 they introduced a social policy to provide all citizens with free water, using EThekwini’s standard of 6000 kilolitres/household/month. In 2006, less than a decade after the initial community consultations in the Durban townships, the UNDP Human Development Report promoted SA’s free basic water policy as a strategy to meet the MDGs. The point is, a municipal government’s practical attempt to address poverty (initiated by a proactive municipal official) led to a national free basic water policy and is influencing ‘global policy’ (if such a thing really exists). Would this change have happened if it was done the other way round?

Other examples of activist mayors or cities that have been catalysts for wider change include:

The Mayors Against Illegal Guns campaign (another initiative involving Bloomberg)

Brazil’s famed Bolsa Familia programme, which has made a huge impact in Brazil and beyond, has its origins in the Bolsa Escola conditional cash transfer programme, which was pioneered by the (then opposition) Workers Party city government of Brasilia. It was a policy aimed at reducing poverty and inequality (it succeeded) but it was also part of the opposition’s political strategy.

Duncan has written on this blog before about how the city of Medellín (in Colombia) was turned around, in the face of a pervasive narco-industry and paramilitary-driven violence and chaos.

What are your best examples of a progressive city government, social movement or company helping to shift a bigger problem by first achieving change in a city or several cities? Likewise, where has it failed or been used in a regressive way?

August 31, 2014

Links I liked

Last week’s round up for the un-twittered from @fp2p

One for your collection of ‘best apologies ever’ [h/t Rachel Ann Morris]

China hits middle income trap: rising wages, falling productivity [h/t Gawain Kripke]

The World Bank’s latest stats on financial exclusion. Globally, 2.5 billion people have no bank account (37% of women in developing countries, compared to 46% of men); that falls to 20% among adults living on less than $2 a day.

Saying ‘7/10 fastest growing economies are in Africa’ has no real meaning. Comprehensive stats takedown by Morten Jerven (and I’m really sorry I still haven’t reviewed your book, Morten)

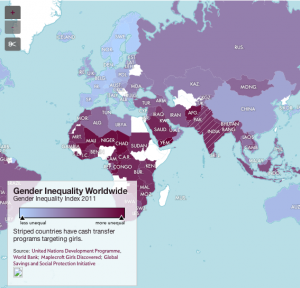

What Countries Have the Worst Gender Gaps? (click to expand)

What Countries Have the Worst Gender Gaps? (click to expand)

Joe Stiglitz is unimpressed by the ‘no’ camp’s economic arguments (aka ‘scare tactics’) in the Scottish independence referendum

Is ISIS here to stay? Probably. Another brilliant analysis by The Guardian’s Jason Burke

Wonkwar (a very polite version). The Center for Global Development responds to DFID on Payment by Results (CGD pro, DFID more sceptic)

Ever wanted to see a unicycling Darth Vader with flaming bagpipes? You’re in luck. Remembering this made me start laughing while swimming – very alarming. [h/t Tim Harford]

And in case you’re interested (or have just come back from holiday), August’s 2 most popular posts on this blog were:

down down social entrepreneurship

August 28, 2014

Good research, great video: what’s the best way to motivate community health workers?

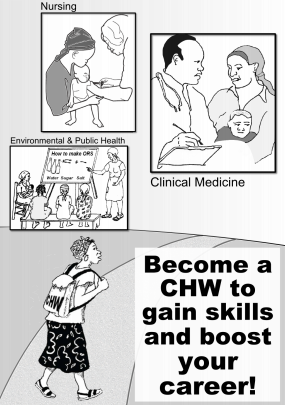

Some more innovative work from the London School of Economics. This genuinely thought-provoking 8 minute video describes a collaboration between the LSE-hosted International Growth Centre and Zambia’s Ministry

of Health. The background academic paper is here.

of Health. The background academic paper is here.

Researchers and officials worked together to answer an important question: to motivate people in rural villages to become rural community health workers (CHWs), is it best to appeal to their community spirit, or to their hopes for individual career development? If you do the latter, will people lose their link to the community, and replicate the problem with more standard professional health workers, many of whom hate working in rural areas, and head for the city?

To do that, they divided up 160 villages targeted for recruitment. In half they put up posters that stressed ‘come and serve your community’, in the rest they put the emphasis on careers (see pics). Sure enough, the posters attracted different kinds of people to apply for CHW training.

So what happened? The paper concludes:

‘We find that making career incentives salient attracts more qualified applicants with stronger career ambitions without displacing pro-social preferences, which are high in both treatments. Health workers attracted by career incentives are more effective at delivering health services and are equally likely to remain in their posts over the course of 18 months. Career incentives, far from selecting the “wrong” types, attract talented workers who deliver health services effectively.’

There are important lessons here. Firstly, the way to generate research – the IGC built long term relationships with the Ministry of Health, meaning that they could work together on the basis of trust and respect. The very opposite of the ‘extractive research’ that is all too common in academia. (‘I need access to your community for my research’).

The findings suggest that career incentives work better and do not lead to an exodus of staff. However, one caveat – to be certain, you would want to follow the CHWs over a longer period of time than 18 months to test for desertion rates.

One other caveat – it still feels very top down. LSE pointy heads workshopping busily with Ministry officials and sympathetic politicians and agreeing what tests to run on the communities in terms of recruitment strategies. What would the research have looked like if they’d designed it with the involvement of CHWs or the communities themselves? Rather different, I imagine.

It all goes some way to restoring my faith in the value of randomization and experimental approaches, when done well. And of course, it’s a brilliantly accessible way to publicise research findings.

Here’s the video summary:

[h/t Hugh Cole]

August 27, 2014

The best evidence yet on how Theories of Change are being used in aid and development work

If you are interested in Theories of Change (ToCs), you have to read Craig Valters’ new paper ‘Theories of Change in International Development:  Communication, Learning or Accountability’ or at least, his accompanying blog. The paper draws on the fascinating collaboration between the LSE and The Asia Foundation, in which TAF gave LSE researchers access to its country programmes and asked them to study their use ToCs. That means Craig has been able to observe their use (and abuse) in practice.

Communication, Learning or Accountability’ or at least, his accompanying blog. The paper draws on the fascinating collaboration between the LSE and The Asia Foundation, in which TAF gave LSE researchers access to its country programmes and asked them to study their use ToCs. That means Craig has been able to observe their use (and abuse) in practice.

What this paper helps answer is the question I raised a while ago – will ToCs go the way of the logframe, starting out as a good idea, but being steadily dumbed down into a counterproductive tickbox exercise by the procedural demands of the aid business?

Here are the headline findings from Craig’s blog

A Theory of Change approach can create space for critical reflection, but there is a danger that this is an illusory process.

Personalities matter—they change whether a Theory of Change is seen as a tool of communication, learning, or a method of securing funding, or some combination of these.

Power relations between donors and implementers in the international development industry discourage critical reflection and therefore constrain Theory of Change approaches.

A Theory of Change approach needs to focus on process rather than product, uncertainty rather than results, iterative development of hypotheses rather than static theories, and learning rather than accountability.

Politically expedient Theories of Change may be useful, but are unlikely to encourage critical reflection.

If the aim is to encourage critical reflection and learning, the use of Theories of Change should be supported only so long as they remain useful in that respect

Read the blog for a fuller explanation of these points, but in addition a few of the things that jumped out at me from the longer paper were:

What is a ToC anyway? ‘it is useful to draw a distinction between a Theory of Change as a formal document and as a broader approach to thinking about development work. For some Theory of Change is a precise planning tool, most likely an extension of the ‘assumptions’ box in a logframe; for others it

Not much participation there, then

may be a less formal, often implicit ‘way of thinking’ about how a project is expected to work.’

But in either case, ToCs are currently very top down, usually drawn up by ‘experts’ in the country office, rather than through anything resembling a participatory process.

ToCs are a stone that tries to kill three birds at the same time. Unsurprisingly, that causes problems:

Communications: both external (donors, partners, governments) and internal (getting staff on the same page)

Learning: Thinking through a ToC helps learning, but the benefits are more pervasive. A TAF staff member beautifully captures what I think are one of their main benefits ‘”issues creep into everyday language…at a philosophical level, the Theory of Change is [creating] learning across programmes”. A good ToC is a kind of ‘iteration engine’, creating space for reflection and learning, and consequent (initially unforeseen) adjustments to the programme.

Accountability: But ToCs are also being driven by donors, who increasingly demand them in project applications, and this can have a ‘a corrosive effect on their honesty and usefulness.’

But ‘this does not close off their benefits entirely; whether to play to donor narratives is a choice and it can be done to different degrees. This puts the onus on both donors and implementing organisations to create better conditions for honesty and critical reflection on assumptions.’

This is key – there is wiggle room between the demands of accountability and the need to use ToCs to learn and adjust, and whether organizations use that wiggle room is at least partly down to their clarity and assertiveness.

I think there’s a dynamic here: a new approach comes in, initially in a fuzzy, all things to all people, kind of way. That liberates people to think more  broadly (in this case about working in complex systems, living with ambiguity and uncertainty, adjusting to events and new insights etc, rather than doggedly pursuing the initial plan/claiming linear cause-effect impact, however implausible). But if the new approach is popular, there are inevitably pressures to codify and standardise, with the risk of losing what is most valuable about the new tool. But that is not a given, and at the very least, the forces of light need to fend off the tick boxes for as long as possible.

broadly (in this case about working in complex systems, living with ambiguity and uncertainty, adjusting to events and new insights etc, rather than doggedly pursuing the initial plan/claiming linear cause-effect impact, however implausible). But if the new approach is popular, there are inevitably pressures to codify and standardise, with the risk of losing what is most valuable about the new tool. But that is not a given, and at the very least, the forces of light need to fend off the tick boxes for as long as possible.

Last paragraph to Craig:

‘It is clear that the way in which Theories of Change are approached is closely related to the prevailing development discourses of ‘results’ and ‘evidence’. With this comes a considerable danger that the approach will privilege a linear cause and effect narrative of change. There appear to be two schools of thought on the direction of Theories of Change: one which seeks to use the tool to expand our understanding of change contexts, and another which views them as a “logframe on steroids”. As a DFID adviser highlighted, there appears to be a rather profound scepticism about the former winning out, given that Theories of Change have “become another corporate stick to beat people with” which is often not “helpful in terms of changing behavior”. The onus is therefore on likeminded donors, implementers and researchers to build a case for a critical, honest and reflective approach, which takes the complexity of social change seriously.’

August 26, 2014

What’s next for the (rapidly growing) global disabled people’s movement?

Last week I headed off to the Kennington Tandoori for one of those enjoyable food-fuelled brainstorms that seem to happen during the summer lull. This  one was with two disability campaigners – Mosharraf Hossain (right) and Tim Wainwright of ADD International. ADD is doing some brilliant work supporting the emergence of Disabled People’s Organizations in Africa and Asia.

one was with two disability campaigners – Mosharraf Hossain (right) and Tim Wainwright of ADD International. ADD is doing some brilliant work supporting the emergence of Disabled People’s Organizations in Africa and Asia.

ADD is at the forefront of what feels like a coming issue in aid and development. The UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities, adopted in 2006, is now hurtling (by UN standards) through the process of national ratification (as of August 2014, 147 countries have ratified, and even the US is rumoured to be about to sign up, despite its traditional hostility to convention-signing).

DPO protest, South Africa

Ratification triggers a process of incorporation into national legislation and policy. As seen previously with UN Conventions on child rights or violence against women, the key to such processes actually making a difference is the presence of social movements on the ground to press for implementation. That’s where ADD comes in – it supports the growing number of DPOs (Disabled People’s Organizations) with funding, advice on policy and international networking. (Mosharraf has spent the last 20 years helping build a dynamic DPOs movement in Bangladesh and has just moved to London to be ADD’s head of policy and advocacy).

The other reason disability is going to go up the development agenda is numbers. The WHO estimate one in seven of the world’s people are disabled, and 110-180 million are severely disabled. In developing countries many of them are among the most marginalized and excluded, often being treated abominably. Unless something changes, the rising tide of growth is going to do precious little for disabled people, so all those conversations about ‘getting to zero’ are going to have to start taking disability much more seriously.

Hence the brainstorm – how to help the global disability movement in its efforts? Here’s a few of the topics we covered:

DPO rally, India

Widening the alliances. Which ‘unusual suspects’ could be persuaded to back a growing global disabled rights movement? Faith organizations? Which corporate sectors might see a natural fit with the issue – perhaps IT companies that have so much to offer to people living with disabilities?

Celebrity Champions: Who are the Angelina Jolies of disability? (yes, ADD is already trying to talk to Stevie Wonder ). Steven Hawking too obvious?

Institutional Champions: DFID is currently leading the way on this (see this recent post). UK leadership is partly why Mosharraf has moved to the UK from his native Bangladesh – the hope is that DFID develop the new policies and approaches that the rest of the aid world can then adopt/adapt.

Academic champions: who is the Richard Layard or Thomas Piketty of disability?

Research: Lots of possibilities here for some bottom up research. How about something longitudinal, interviewing communities and their disabled citizens over a period of years, as Oxfam is doing on food prices? Or use IT to build a network of disabled correspondents who can answer periodic surveys or respond to topical questions? Time for Apple or Google to step up?

Then some strategic questions: should the disability movement go mainstream or build a separate strength? For example, should it be seeking to insert disability issues into other global discussions on education, health etc, or establish disability as a legitimate separate topic for discussion? (lots of efforts to include disability in the post2015 process after it was ignored in the MDGs).

All good fun, but as we left the restaurant, I got a tiny glimpse of the reality of life for disabled people. Mosharraf is a wheelchair user, after contracting polio aged 3. Luckily he arrived early, because he had to go home to get his crutches to be able to manoeuvre over the entrance step and into the restaurant. As we left the waiter, (even though he was a fellow Bangladeshi), he turned to me to ask about the arrangements for getting Mosharraf to the bus stop. Not quite ‘does he take sugar?’, but not far off. Last word to Mosharraf ‘we look forward to meeting you again in some other location, which will be step free and people will be free from prejudice.’ Looks like the Kennington Tandoori just lost some customers.

August 25, 2014

Links I liked

Last week’s top tweets, a day late, as we enjoyed a traditional rain-soaked August bank holiday yesterday.

Media fatigue with Syria v the mounting death toll – powerful infographic from ODI

It was World Humanitarian Day last Monday: In South Sudan, Oxfam’s staff ‘walk for 12 hours through mud & rain, in an area with a lot of men with guns’.

A brilliant account of the evolution from terrorists (al-Qaida) to insurgents (ISIS) from the Guardian’s Jason Burke. Covers the role of territory, funding, who they target and alliances. And his follow up piece on ISIS’ long term prospects.

Ebola (like HIV) is gendered. 3/4 of dead in Liberia (one of the hardest hit countries) are women, because they get sick caring for victims

You want electricity? Ensure your guy gets into power. Political patronage can be seen from outer space. [h/t Rakesh Rajani]

Some Random stuff on inequality

Some Random stuff on inequality

In Mexico, municipalities with lower inequality saw lower rates of crime, according to new research from the World Bank

If inequality was an airplane [h/t Ben Phillips]

Meanwhile, the US decided it was all about them last week, in particular Ferguson, producing some top satire from the ever-wonderful John Oliver

or how the US media would cover Ferguson if it was somewhere other  than the US… [h/t Tim Harford]

than the US… [h/t Tim Harford]

but when it comes to culture wars, nothing can match Fox News’ capacity for self-parody. Here’s their panel on ‘Race in America’. Notice anything odd?……

August 21, 2014

Which is more important – changing policies, or changing social norms and behaviours (and how are they connected)?

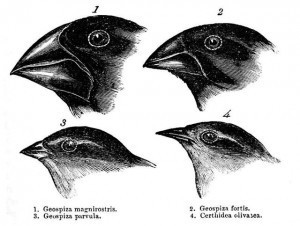

It can be a little disorienting when you stray from your intellectual silo, and read stuff from other disciplines. Sometimes it is entirely unintelligible, but it  gets more interesting when it resembles debates in development land, but with slightly different language (or the same words mean slightly different things) and reference points, like Darwin’s finches diverging on their different Galapagos islands.

gets more interesting when it resembles debates in development land, but with slightly different language (or the same words mean slightly different things) and reference points, like Darwin’s finches diverging on their different Galapagos islands.

So thanks to Katherine Trebeck for sending over a blog by Matthew Taylor, a top UK domestic policy and chief executive of the RSA, a sort of proto thinktank (founded in a coffee shop in Covent Garden in 1754). In it, Matthew decides he has spent too much of his life arm-wrestling on policy, and not enough on norms and ‘collective impact’:

‘Like a reformed smoker I am lifetime policy wonk who has now turned against my former habit. This is how I put the argument in a recently co-authored review article on ippr’s recent Condition of Britain report:

This is not, of course, to say that policy is dead. The point is that most social policy goals involve what Jocelyn Bourgon, and her colleagues in the New Synthesis project on 21stcentury public administration, call ‘civic effects’, that is changing social norms and behaviours and increasing in the resilience and problem solving capacity of communities. But if this is the goal the success factors are as likely to be authentic leadership, convening new forms of dialogue and collaboration and creating varied platforms for local and individual initiative as policy codified in legislation. To put it another way, the centre left has tended to see social engagement as a facet of the transformative project of policy making but instead we should see policy as a facet (and sometimes even a relatively unimportant one) of the transformative task of social mobilisation.’

He then cites a piece from Stanford Social innovation Review, by Fay Hanleybrown, John Kania and Mark Kramer on collective impact projects and their success factors.

‘The authors provide more case studies of successful collective impact projects in areas ranging from tackling teenage binge drinking in a Massachusetts district to cutting homelessness in Calgary, Canada. These projects have a clear mission which the participants are willing to spend years working at, they are highly collaborative and combine expert agencies with community groups and concerned citizens.

Here are four extracts that help illustrate why collective impact is different than conventional policy making:

Here are four extracts that help illustrate why collective impact is different than conventional policy making:

The most critical factor by far is an influential champion……. one who is passionately focused on solving a problem but willing to let the participants figure out the answers for themselves, rather than promoting his or her particular point of view

Collective impact efforts are most effective when they build from what already exists; honoring current efforts and engaging established organizations, rather than creating an entirely new solution from scratch.

Strategic action frameworks are not static….They are working hypotheses of how the group believes it can achieve its goals, hypotheses that are constantly tested through a process of trial and error and updated to reflect new learnings, endless changes in the local context, and the arrival of new actors with new insights and priorities

One such intangible ingredient is, of all things, food. Ask Marjorie Mayfield Jackson, founder of the Elizabeth River Project, what the secret of her success was in building a common agenda among diverse and antagonistic stakeholders, including aggressive environmental activists and hard-nosed businessmen. She’ll answer, “Clam bakes and beer.”

Of course, national and local policy can facilitate collective impact projects (although on the whole it has been more likely to disrupt and deter them) and these projects may well end up identifying necessary policy reforms. However, the question posed by collective actors is ‘what can we do given the policy context we have’ much more than ‘how can we change that policy context’.’

I love this (especially the food bit). Matthew is asking what the UK can learn from the US, but what are the implications for those of us working in other countries? I think the challenge he is raising is to the traditional division between ‘advocacy ’ and ‘programmes’, in which advocacy is about changing government policy, and ‘programmes’ are about supporting and working with communities on the ground. I find the distinction increasingly unhelpful.

If you accept Matthew’s argument (that the real driver of change is collective action (what he calls ‘collective impact efforts’), rather than policy change), possible implications include:

- The need to reconnect advocacy and programmes into a single process (something we are trying to do in Oxfam, using the word ‘influencing’ to span this search for broader impact)

- You might focus more on the implementation of existing policies rather than arguing for new ones

- When seeking policy change, you would explicitly think about the broader normative and collective aspects, rather than just seeking a quick campaign win

I’m not entirely convinced by all this – policy change on issues such as tax and spend, or regulating over-powerful players, is vital in creating an environment in which collective action can flourish. But there is something there. The last point has cropped up in my discussions with Anna Macdonald on our case study on the global campaign for an Arms Trade Treaty. I was struck by the lack of engagement with faith groups (apart from getting Desmond Tutu to sign stuff, but while welcome, doesn’t really constitute an institutional engagement).

I’m not entirely convinced by all this – policy change on issues such as tax and spend, or regulating over-powerful players, is vital in creating an environment in which collective action can flourish. But there is something there. The last point has cropped up in my discussions with Anna Macdonald on our case study on the global campaign for an Arms Trade Treaty. I was struck by the lack of engagement with faith groups (apart from getting Desmond Tutu to sign stuff, but while welcome, doesn’t really constitute an institutional engagement).

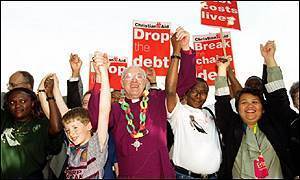

The contrast with the Jubilee 2000 debt campaign (right) is striking – given its subject matter, the ATT work could have been based on religious teachings and put down deep roots in faith organizations. That would have been longer and more cumbersome, and you might respond ‘hey, we got the treaty, so what’s your problem?’ But Matthew’s post points to a possible consequence – what happens next? What will decide whether the campaign leads to real changes in attitudes and practices among leaders and populations? I wonder whether the campaign could have prepared better for this stage by thinking about collective impact and normative shift, and designing the campaign around that as well as working the corridors of power in search of a new policy instrument (which they did brilliantly, of course).

Over to you.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers