Duncan Green's Blog, page 185

July 10, 2014

Some Friday Feelgood: Why campaigners should take heart from Anthony Trollope, the Overton Window and Madiba

“Many who before regarded legislation on the subject as chimerical, will now fancy that it is only dangerous, or perhaps not more than difficult. And so in time it will come to be looked on as among the things possible, then among the things probable;–and so at last it will be ranged in the list of those few measures which the country requires as being absolutely needed. That is the way in which public opinion is made.”

be looked on as among the things possible, then among the things probable;–and so at last it will be ranged in the list of those few measures which the country requires as being absolutely needed. That is the way in which public opinion is made.”

“It is no loss of time,” said Phineas, “to have taken the first great step in making it.”

“The first great step was taken long ago,” said Mr. Monk,–”taken by men who were looked upon as revolutionary demagogues, almost as traitors, because they took it. But it is a great thing to take any step that leads us onwards.”

— Anthony Trollope, Phineas Finn, 1868 (see left, peak beard definitely a Victorian thing)

So take heart all you ‘revolutionary demagogues’ demanding action on climate change, reining in the finance sector, redistribution, planetary boundaries, the care economy, limits to growth, international taxation, open data, or rights for any number of excluded/oppressed groups.

The Overton window, by the way, is a political theory that describes as a narrow “window” the range of ideas the public will accept. On this theory, an idea’s political viability depends mainly on whether it falls within that window rather than on politicians’ individual preferences. It is named for its originator, Joseph P. Overton. At any given moment, the “window” includes a range of policies considered politically acceptable in the current climate of public opinion, which a politician can recommend without being considered too extreme to gain or keep public office.

Nelson Mandela put it rather more succinctly:

July 9, 2014

Why ‘political economy analysis’ has lost the plot, and we need to get back to power and politics

Adrian Leftwich (right), a much-loved guru of the ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ (TWP) movement, died in April 2013. But in testament to his importance (and the slow grind of  academic publishing), his last paper only came out last month, and it is an important one.

academic publishing), his last paper only came out last month, and it is an important one.

Written with David Hudson of UCL (and universally referred to as the ‘Hudwich paper’), From Political Economy to Political Analysis critiques the way TWP has evolved. In a nutshell, it fears that it has succumbed to two temptations – trying too hard to look like economics, and succumbing to pressure to turn itself into a toolkit. Time to get back to power and politics.

I loved the paper for two main reaons: it nails the origins of my disquiet at the way that in polite society, we often say ‘political economy’ when we actually mean politics, and it puts human agency back in to what can sometimes seem like a defeatist exercise (political economist = someone who comes and explains why your project has failed). Some highlights:

‘Political economy has thus now virtually become a shorthand term for the emerging consensus that it is not only technical, administrative or managerial factors that explain poor development performance. The way in which political and economic processes interact is also critical in promoting or frustrating developmental processes.

There have been three broad phases – or ‘generations’ – of political economy work:

The ‘first generation’, in the 1990s, mainly addressed issues of ‘governance’ (and especially the reasons for the absence of ‘good governance’), but largely from a technical, administrative, managerial, capacity-building and, subsequently, public sector management perspective. Work in this tradition continues.

The ‘second generation’ is best typified by DFID’s Drivers of Change, Sida’s Power Analysis, and the Dutch SGACA work (Strategic Governance and Corruption Analysis). Importantly, these approaches and the many studies they generated made a huge contribution. They ‘brought politics back in’, with a greater emphasis on historical, structural, institutional and political elements that shaped the context within which actors worked.

The ‘third generation’, often combining elements from the previous two, has come to be strongly influenced by assumptions, concepts and methods drawn from economics. It emphasises the way in which institutional incentives shape behaviour to produce positive or dysfunctional developmental outcomes. In short, political economy has come to be the economics of politics, and less about political analysis.’

But the latest twists have some serious limitations:

‘The key analytical concepts are seldom well-defined, carefully differentiated or usefully disaggregated. Among these we include institutions, structure, agency, ideas, contingency and – above all – power. The way they are used tends to provide for lumpy, one-dimensional analysis. It does not allow analysts or policy makers to reach the detailed inner politics that shapes or frustrates change.

The explanatory core of third generation political economy has increasingly come to focus on how interests, incentives and institutions shape and explain both how agents behave and the political processes and practices that affect development outcomes.

The net effect has been to transform the analysis of politics into the economics of politics. And, by effectively reducing politics to a form of ‘market’, much recent political economy misses what is distinctively political about politics – power, interests, agency, ideas, building coalitions and the impact of contingency.

Political analysis on the other hand takes politics, power and agency much more seriously. Unlike second and third generation political economy, political analysis enables one to dig down to the level of messy, everyday politics.

This is where there are competing ideas, interests, values and preferences; where specific groups and interests struggle over the control, production, use and distribution of resources; where conflict is negotiated; where bargains are struck; and where formal and informal political settlements, alliances and coalitions are made and broken. Here politics collapses and violent conflict can break out; institutions are contested, shaped, implemented, avoided, undermined or amended; contingency, critical junctures and windows of opportunity disturb old patterns or open up new possibilities and – crucially – here the different players use different sources, forms, expressions and degrees of both de jure and de facto power.

There is now a growing realisation that we need to refocus not simply on ‘big structures’ but also on actors – in short, agency, defined as the ability of individuals, organisations and groups of collective actors to consciously deliberate and act strategically to realise their intentions, whether developmental or not. But, whether individual or collective, agents do not work politically in a limitless, structureless and institution-free plane of open possibilities.

The structural and institutional contexts of power – formal and informal, local and external – always and everywhere constitute constraints. However, while structures  and institutions are constraints, they are not destiny. People, groups, organisations and coalitions do not move in unison, like reeds in the wind, to a change of incentives.

and institutions are constraints, they are not destiny. People, groups, organisations and coalitions do not move in unison, like reeds in the wind, to a change of incentives.

Structures and institutions provide opportunities and resources that agents can use – and hence also provide room for manoeuvre. The point is that structures and institutions of power not only constrain political actors, but can also provide the resources which they, as agents, can find and use to initiate or bring about change.

Political analysis does not ignore interests, incentives or institutions, but goes further and deeper. It differentiates and disaggregates interests, ideas, incentives and institutions, and also has the analysis of power (and the sources and forms of power) at its core.

Political analysis focuses on how the structures and institutions of power shape how agents behave, and how they do or can strategise, frame, generate, use, mobilise and organise power and institutions to bring about domestically owned deliberation and appropriate change in the politics of development.

Ultimately, if you wish to defeat poverty, prepare to address the power and the politics that keeps people poor. That is why political analysis matters.’

If you want to understand what TWP is all about, the full 108 page paper is a great place to start.

July 8, 2014

From ‘baby-making machines’ to active citizens: how women are getting organized in Nepal (case study for comments)

Next up in this series of case studies in Active Citizenship is some inspiring work on women’s empowerment in Nepal. I would welcome comments on the full study: Raising Her  Voice Nepal final draft 4 July

Voice Nepal final draft 4 July

‘I was just a baby making machine’; ‘Before the project, I only ever spoke to animals and children’; ‘This is the first time I have been called by my own name.’ [Quotes from women interviewed by study tour, March 2011]

While gender inequality remains extreme in Nepal, Oxfam’s Raising Her Voice (RHV) programme on women’s empowerment is contributing to and reinforcing an ongoing long-term shift in gender norms, driven by a combination of urbanization, migration, rising literacy and access to media, all of which have combined to erode women’s traditional isolation.

During the past 20 years, Nepal has also undergone major political changes. It has moved from being an absolute monarchy to a republic, from having an authoritarian regime to a more participatory governance system, from a religious state to a secular one, and from a centralized system to a more decentralized one.

These shifts have produced some important windows of opportunity and implementation gaps on which RHV seeks to build. To do this, RHV has set up some 80 Community Discussion Classes (CDCs), bringing women together for up to 2 hours a day to share experiences, enhance their knowledge of local decision making, and build their communication, advocacy and leadership skills. Crucially, facilitators come from the communities themselves.

CDCs have become the building blocks of a remarkable exercise in grassroots empowerment. Women have seen tangible progress in their homes, communities and broader social and political roles on issues such as violence against women, political representation and the right to be heard.

Change Strategy

The change strategy in Nepal echoes RHV’s global framework (see diagram)

The change strategy in Nepal echoes RHV’s global framework (see diagram)

Personal Sphere

Although men have many informal and formal forums in which to discuss their issues, such as local tea shops or community meetings, women have previously been more isolated. Aiming to counter this, the CDCs have reached about 2,000 women through 80 classes.

CDC activities include literacy, discussions on community issues selected by the participants, and agreement on action plans to tackle shared problems. Often the facilitator introduces new information to the group, using printed material, but also role plays and debates.

Social Sphere

The CDCs have proven effective in breaking down the walls of women’s isolation. Almost all of them have started collective savings and credit schemes. Many have claimed ring-fenced, but often undisbursed village budgets for construction of community toilets and halls. Others have organized ward meetings that bring together women and men from across the community, as well as teachers, political party representatives and local government officials.

In many cases, CDCs took root slowly, identifying a few women who were relatively free to join project activities and building out from there, as they encouraged others who were either less convinced or faced greater constraints from husbands or others.

By creating an ‘enabling environment’ of women’s empowerment, rather than a specific project, RHV was able to adapt to the different context in the three project districts. In one, the focus was on addressing shared issues such as alcohol abuse, whereas in the other two, there was a stronger focus on supporting individual women through group coaching, counselling and mediation.

In addition to promoting women’s participation, the project deliberately sought to influence existing, mainly male, committee members as well as other influential local actors such as policy officers and civil servants.

Political Sphere

Work at national level highlighted poor governance, particularly at village and district levels, and its negative effects on the people, especially women. This was achieved through radio programmes, national assemblies involving over a hundred community women representatives, subsequent lobby meetings with politicians, bureaucrats, police, rights organisations etc.

In the event, RHV found that although the lobby meetings did not yield anything concrete immediately, they served as a strong morale booster for the women who came to Kathmandu (the majority of them for the first time in their lives). Many said that now that they had interacted face to face with so many senior officials and politicians, they could easily face the local level officials and politicians and would not allow them to look down on them and ignore their voice. They went back to their villages and did exactly that.

The CDCs also encouraged women’s participation in Nepal’s plethora of community organizations. RHV targeted four in particular: Community Forest User Groups  (CFUGs), School Management Committees (SMCs), Sub-Health Post Management Committees (SHMCs), and Drinking Water and Sanitation User Groups (DWSUGs).

(CFUGs), School Management Committees (SMCs), Sub-Health Post Management Committees (SHMCs), and Drinking Water and Sanitation User Groups (DWSUGs).

Women’s participation has grown most in committees with quotas, and evaluation finds that women members have more influence on, and are more likely to have leadership roles in, committees when they have received more training, are involved in more than one committee and are fully supported by their family.

New institutions are often more malleable and thus easier to influence than established ones, and an opportunity has arisen with the Ward Citizen Forums that are being gradually implemented under the Ministry of Local Development’s Local Governance and Community Development Programme. These are intended to facilitate participatory planning processes at village and ward levels, and also espouse accountability and transparency in local governance until local elections are held.

To some extent, CDC women leaders have also become role models for women in other communities, inspiring numerous women from villages next to RHV communities to ask for help in setting up their own CDCs.

Surprises and Dilemmas

Local political party committees and leaders soon noticed the confidence, leadership skills, and networks of RHV women and started trying to recruit them. Initially, the women were reluctant for fear that if they joined different political parties, they would lose their previous levels of solidarity and organisation, and things might fall apart.

Oxfam and its RHV partners cautiously watched and supported the CDCs, helping them analyse the manifestos of different political parties, explaining how political parties function, the electoral processes, and the pros and cons of joining political parties. This was a delicate balance between giving useful knowledge but at the same time leaving the decision up to them. So far more than 150 CDC women have joined different political parties and some of them now plan to stand in local elections.

When a project like this succeeds, it has to accept a certain loss of control. In the phrase of Robert Chambers, project managers have to ‘hand over the stick’ to poor women to take their own decisions. Empowered women come up with their own priorities and approaches, and these are sometimes uncomfortable for project organizers, as for example when women set up a number of Alcohol Control Committees, started limiting alcohol sales in the villages and imposing fines on drunkards. Some then went further and physically destroyed bars.

Feel free to comment on previous draft case studies in this series on Campaigning on the US Deepwater Horizon oilspill, Changing hearts and minds on Violence Against Women in South Asia, promoting Women’s Leadership in Pakistan, Labour Rights in Indonesia, and Community Protection Committees in DRC

An important breakthrough on disability, aid and development

One of the trends in aid and development in recent years has been increasing recognition of issues around disability. A lot of that is down to

One of the trends in aid and development in recent years has been increasing recognition of issues around disability. A lot of that is down to  the activism of Disabled People’s Organizations (DPOs). Here disability campaigners Mosharraf Hossain and Julia Modern update us an important breakthrough

the activism of Disabled People’s Organizations (DPOs). Here disability campaigners Mosharraf Hossain and Julia Modern update us an important breakthrough

In April we blogged on this site about the publication of the UK parliament’s International Development Select Committee report on disability and development. Last week the Committee published the official response to the report from the government. It’s a thorough and thoughtful reply to the challenges that the Committee set to the Department for International Development (DFID), and the changes that are set out have big implications for practices throughout the international development sector, particularly for organisations that DFID funds (including NGOs and multilaterals), which will find themselves increasingly being held accountable for whether they include disabled people in their work.

What does this mean for the 800 million disabled people living in the developing world? The proof will be in the implementation, but this is a giant leap forward. DFID have made a public commitment to prioritising the inclusion of disabled people, improving their own work and signalling to others that more needs to be done. In the humanitarian sector in particular the response talks about a fundamental shift, with disaggregated reporting on age and impairment of recipients a requirement in all future humanitarian proposals.

After Cyclone Sidr in Bangladesh in 2007 I witnessed the results of not thinking about the inclusion of disabled people in emergency responses; with thousands of people competing for limited assistance, disabled people lost out. Monitoring recipients and supporting training in disability inclusion for relief providers will help to ensure this doesn’t happen in the next disaster responses.

While DFID

haven’t accepted every recommendation made by the Committee, they have committed to an impressive series of actions:

Publish a disability framework by November 2014. To be developed in consultation with Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs) and NGOs, the framework will set out DFID’s ‘commitment, approach and actions to strengthening disability in our policy, programme and international work.’

Strengthen DFID’s capacity to work on disability inclusion, by: appointing a senior-level managerial champion to work alongside Ministerial champion Lynne Featherstone MP; increasing the number of staff working on disability in the central policy team and creating a network of disability experts across DFID; and creating a ‘basic disability awareness module’ that will be rolled out to all staff, as well as providing more and better guidance on inclusion.

Push DFID’s partners towards disability inclusion, including through the World Bank’s current safeguards review; reviewing the Multilateral Aid Review process to check that it adequately monitors disability inclusion; and asking civil society organisations that DFID funds to report on disability in future annual reviews.

More thoroughly embedding disability in DFID internal processes, for example by including DPOs in the Ministerial disability advisory group, putting ‘specific reference to considering disability and other vulnerabilities in guidance for future country level operational plans’, and strengthening inclusion in large-scale programmes ‘through strengthened systems as well as ministerial and managerial championing’.

It is this last area, strengthening DFID’s internal processes, in which the response gives least detail, suggesting that whether the attempt to embed inclusion into DFID’s processes is successful will be decided largely by the details of the new disability framework, to be produced by November. We hope that the framework will address a few areas that remain unclear:

There isn’t much information in the response about how DFID’s practices will change at country level.

The response doesn’t fully engage with how DFID will access the expertise of Southern DPOs.

While DFID set out a clear commitment to support the development of better data on disability, they have not taken on board all the Committee’s recommendations

about monitoring of their own programmes or other UK ODA spending.

about monitoring of their own programmes or other UK ODA spending.The investment DFID is making in global capacity to collect data on disability should be matched by setting out in November’s framework a timescale for introducing systems to collect this data in all DFID bilateral programmes. Gathering this data is the only way to properly monitor whether DFID are increasing on that 5% of bilateral aid going to programmes that consider the needs of disabled people, and is therefore an essential part of making sure the increase happens.

DFID’s response is truly promising, and shows respect and consideration to the evidence the inquiry received from disabled people and their supporters. As a trend-setter in development, we hope and expect that the promised changes will be transformative for disabled people in the developing world.

July 6, 2014

Links I liked

[for Jenny, who only ever reads these posts, never the more boring ones]

Inevitable World Cup nonsense (and sense)

Number of extra ‘O’s in ‘GOAL’ in Facebook posts, by country average [h/t Ben Phillips]. (Caution, this is based on the group stage – subject to rapid change over next few days)

The Brookings Institution on African teams’ mixed performance (& behaviour)

Best photoshop reactions to Luis Suarez getting his teeth into the opposition

Americana

Americans who say Bible is an ancient book of fables has gone up from 13% in 1976 to 21% in 2014 [h/t Conrad Hackett]

‘The American political system is overrun by money’. Inequality is not inevitable. Powerful polemic from Joe Stiglitz [h/t John Magrath]

Chris Blattman is on the money (in both senses) in this New York Times piece on the case for cash transfers in the US and everywhere else

Other stuff

How to appear smart in meetings – leap up and draw Venn diagrams; randomly say ‘could you go back a slide, please?’ [h/t Geoff Mulgan, who always seems smart]

Let’s get linear, people, here comes the Log Frame of Love (there must be a song in there somewhere)

Meanwhile, back in a small island off the French Coast…..

Politicians Beware Children: Watch one asking George Osborne “What’s 7×8?” Then enjoy his answer [h/t Ben Phillips]

Defence against backsliding? The Liberal Democrats (junior coalition partners in UK government) seek to enshrine in law a commitment for UK aid budget to be at least 0.7% of Gross National IncomeI (the UN target). It may well pass, too.

But enough of Westminster, this from the other (much more real, wonderful etc) Britain: “For my sisters across the world” 13 year old Sadia from Tower Hamlets, London. [h/t Ben Phillips]

These are some of the links I’ve tweeted over the last week – if you want the real thing, sign up on @fp2p

July 3, 2014

Is ‘thinking and working politically’ compatible with results? Should advocacy ever be done in secret? Big questions at the LSE this week.

This week I found myself on a fun panel at LSE discussing ‘can politics and evidence work together?’ with Mary Kaldor (LSE), Ros Eyben (IDS) and Steven Rood (The Asia Foundation – TAF has a really interesting partnership with LSE to study its use of theories of change). Early last year, I promised to revisit the topic after this blog hosted an epic debate on the politics of evidence between some top DFID people and (in the sceptic corner), Ros Eyben (again) and . Has anything changed since then?

Foundation – TAF has a really interesting partnership with LSE to study its use of theories of change). Early last year, I promised to revisit the topic after this blog hosted an epic debate on the politics of evidence between some top DFID people and (in the sceptic corner), Ros Eyben (again) and . Has anything changed since then?

My 15 minutes of fame are summarized in this page of speaking notes: Notes for Thinking and Working Politically LSE panel July 2014

I largely summarized previous pieces on this blog, but added some alliterative categories for some of the obstacles aid agencies face in thinking and working politically, namely:

· The Toolkit Temptation: managing large bureaucracies creates a demand for standardized and simplified procedures (indeed it’s often the first thing hard-pressed staff ask for). Difficult to shift from that to deep engagement with the local context, thinking on your feet and responding to events etc, trying multiple experiments and failing faster etc

· The Planning Preference: Similarly, big aid organizations maintaing internal coherence and external direction by agreeing (at great length) and implementing plans – strategic, operational etc. After years of thrashing out a plan, they are often understandably reluctant to begin all over again because some major event has presented a new window of opportunity

· The Data Delusion: non-scientists in particular are dazzled by numbers, even if they don’t mean much. I still remember my alarm in a meeting of Oxfam’s big cheeses when, after a discussion based on the experience and judgements of senior people with decades working in the development business, someone said ‘right, so much for the opinions – what do the data tell us?’

The other presentations and ensuing discussion (lots of sharp questions, as you’d expect at LSE) drew out some further lessons.

Ros sees actual state of discussion on evidence in DFID and elsewhere as very unreconstructed, with my preferred TWP-compatible approaches still languishing at the bottom of the ‘quality of evidence pyramid’ (see graphic from her slides)

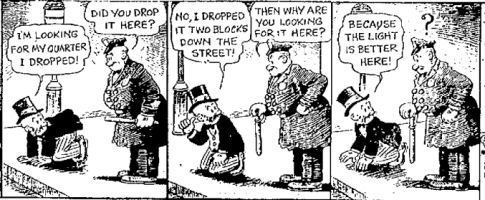

This leads to a major ‘drunk under the streetlamp problem’ of going where the data is, rather than looking at what’s important (see cartoon, not that I’m suggesting MEL people are usually drunk)

This leads to a major ‘drunk under the streetlamp problem’ of going where the data is, rather than looking at what’s important (see cartoon, not that I’m suggesting MEL people are usually drunk)

Fear of failure is deeply rooted at field level – you can forget all that stuff about celebrating/learning from it, at least when there’s a funder in the room.

The real challenges to TWP are often ‘managerial’ – processes like staff rotation, and the kinds of people you employ.

I’ve been mulling over one issue in particular since then: Mary Kaldor was very opposed to any suggestion that TWP might involve some level of acceptance of the ‘dark arts’ – i.e. working in the shadows, persuading people to do things or talk to others in ways they would not want to become public etc. In contrast, Mary argued for transparency and openness throughout, as the only way to ensure accountability.

Which raises some pretty massive dilemmas: TWP and politics in general often moves forward by opposing forces doing deals that would rapidly collapse if exposed to the light too soon – think of just about any peace negotiation in history, or even just the Northern Ireland one. In NGO world, there’s a reason why advocacy is separate from public campaigning, with different staff, language and tactics. One is based on clear, simplified messages, the other on arm twisting and compromise.

But it must be right to be sceptical of advocacy and policy insiders singing the virtues of secrecy (it’s so easy to be coopted – there’s nothing more intoxicating for an advocacy type than to be the only NGO in the room, get the draft document before all your colleagues etc). Fundamentally, secrecy disempowers anyone who is not in the room, and that usually includes the people we are trying to help.

I wondered if the ‘policy funnel’ – a way to understand how new policies evolve from outlandish ideas to agreed policy – might need to be adapted. We need maximum openness in the early stages, eg trying to get issues onto the official agenda, but have to accept a degree of non-transparency if you get as far as negotiating deals, policies, or cash. But then whatever is agreed needs to be open to public scrutiny (so the funnel becomes more like an egg timer on its side). Mary was entirely unconvinced.

I wondered if the ‘policy funnel’ – a way to understand how new policies evolve from outlandish ideas to agreed policy – might need to be adapted. We need maximum openness in the early stages, eg trying to get issues onto the official agenda, but have to accept a degree of non-transparency if you get as far as negotiating deals, policies, or cash. But then whatever is agreed needs to be open to public scrutiny (so the funnel becomes more like an egg timer on its side). Mary was entirely unconvinced.

As to the main question, it didn’t feel like much has changed since last year’s FP2P wonkwar on evidence. Maybe there’s been some progress on learning how to measure what matters, rather than just what’s easy to count, and the randomista craze seems to have passed its peak and hopefully RCTs will soon settle down to become one tool among many, rather than the ‘gold standard’ for everything (remember what Keynes said on the real Gold Standard – a ‘barbarous relic‘).

So over to you – do you see progress on reconciling TWP and evidence? And how do you balance TWP and commitment to openness and transparency? Any good examples?

And here’s the rather nice slide that ended Ros’s presentation (don’t suppose Mary will thank me for the panel pic – click to expand and see why)

July 2, 2014

Which governments are doing best/worst in the fight against hunger and undernutrition?

The Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index (HANCI) 2013 measures political commitment to tackling hunger and undernutrition in 45 developing countries. It uses  two types of data. Primary data comes from Expert Perception Survey’s (EPS) and provides an in-depth view of six countries in the larger dataset (Bangladesh, Malawi, Zambia, Nepal, Tanzania and India). The secondary data analyses 45 countries across 22 indicators analysing political commitment to tackle hunger and undernutrition in terms of policies, laws and spending (see diagram for how the index is constructed).

two types of data. Primary data comes from Expert Perception Survey’s (EPS) and provides an in-depth view of six countries in the larger dataset (Bangladesh, Malawi, Zambia, Nepal, Tanzania and India). The secondary data analyses 45 countries across 22 indicators analysing political commitment to tackle hunger and undernutrition in terms of policies, laws and spending (see diagram for how the index is constructed).

Main findings?

Economic growth has not necessarily led to increased action by governments. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia are global hotspots of hunger and undernutrition, even though many countries within these regions have achieved sustained economic growth over the last decade. For example, Zambia has had a decade of rapid economic growth, yet hunger is highly prevalent and nearly half the population were undernourished during the period 2010-2012, and according to HANCI the Government’s efforts to address these are actually weakening.

Nutrition does not get as much political traction as hunger. Hunger is about empty stomachs; undernutrition is about having the wrong things in your stomach – a critical lack of nutrients in people’s diets – and/or a weakened immune system. Expert perception surveys show that hunger spending is strongly sensitive to electoral cycles, in contrast to nutrition.

For instance politicians in Tanzania anticipate that people vote on the basis of having their stomach filled, so those in power prioritise action to reduce hunger, such as investing in maize production, over efforts to address chronic undernutrition, e.g. by focussing on dietary diversity and clean water. Limited awareness by political leaders and the general public of the dire consequences of undernutrition means that it is harder to get undernutrition onto political agendas.

Perhaps because of these different political dynamics, as Lawrence Haddad points out on his blog, there is very little correlation between government action on hunger, and on nutrition.

This is the second year of the index, and once again, Guatemala is ranked number one. However competition for the top spot is heating up with Peru and Malawi making significant improvements on their political commitments.

Some low ranked countries, including Afghanistan, Angola, Burundi, Liberia and Myanmar, are showing clear improvements. E.g. Burundi increased agriculture spending by 5.9 per cent; enhanced people’s security of tenure over agriculture land; enhanced coverage rates of Vitamin A supplementation; increased access to water and sanitation; initiated a national nutrition policy/strategy; and strengthened safety nets.

Some low ranked countries, including Afghanistan, Angola, Burundi, Liberia and Myanmar, are showing clear improvements. E.g. Burundi increased agriculture spending by 5.9 per cent; enhanced people’s security of tenure over agriculture land; enhanced coverage rates of Vitamin A supplementation; increased access to water and sanitation; initiated a national nutrition policy/strategy; and strengthened safety nets.

But some countries which are already at the bottom of the HANCI ranking, including Guinea Bissau, the Yemen and Sudan are demonstrating a decline in relative commitment. These countries are increasingly getting left behind.

To view the full HANCI data and download the report visit the new HANCI website, which allows you to explore the index data in depth to analyse and compare how each country has performed.

And here’s the country rankings

One minor, nerdy beef: I wish we could standardize the year people put on their annual reports. When publishing something in 2014, some (I’m looking at you, World Development Report) slap a ‘2015’ on it, presumably to enhance its shelf life; others more sensibly say 2014; but modest/bashful/honest ones like HANCI, go with 2013 – I spent ages (well, a couple of minutes) trying to find the 2014 version. Maybe my brain was still recovering from a week’s bird-watching……..

July 1, 2014

Piketty + Ninja Puffins: A Perfect Week

Spent last week on a remote Welsh island, Skokholm (if it sounds like Stockholm, I think that’s because the Vikings invaded it at some point). There was nothing to do

1. Puffin resists

except watch the achingly cute puffins arriving with beak-fulls of eels and try and dive down the burrows to their

2. Goes all Luis Suarez on gull’s eye

waiting chicks before the lurking gulls could grab them. One

3. Gull vanquished. Go puffin.

photographer in our group, Richard Coles, caught some great puffin-on-gull action (see pic sequence, click to enlarge), clearly influenced by Luis Suarez. David fought back, grabbing Goliath by the eye, and didn’t let go. Puffin wins. The pics went viral in the puffin-watching community, apparently. If you fancy it (groups of about 15, small island to yourselves, + several hundred thousand sea birds), check out the website – some slots still available in August.

But back to the day job – development and all that. When it rained, I finally sat down to read Thomas Piketty. There’s not much point in me trying to add to the mountain of handy summaries, reviews by very clever economists, online discussions, largely unconvincing takedowns by the FT etc, so here instead are some impressions from a non-economist.

It took a while to get started – I grazed til about page 200, then got increasingly hooked. It reads like a rather wonderful, scholarly seminar, with multiple digressions, cross references and reflections. A bit like Hobsbawm, but with graphs.

A more brutal anglo-saxon edit could have got it down to 400 pages, but that would have been a shame. Part of its charm is its quintessential Frenchness – an insistence on cross-disciplinarity, the importance of politics, power, institutions and social justice, and a healthy scepticism about all things British or American (see excerpt). All in all, a wonderful, and much-needed alternative narrative on globalization and inequality.

But not at all in the ranty ‘globalization ate my kids’ style that occasionally characterizes French polemics. Capital in the 21st Century is wonderfully measured and numerate, using numbers to understand the broad sweep of modern politics and distribution, the role of the state etc – a great primer. If anything, it probably should have been even longer, because it has some pretty serious blindspots – notably the implications of planetary boundaries for the future economy (climate change gets its first mention on page 567). The care economy and gender issues warrant no mention at all.

And as far as I can tell (schoolboy French only), the translation by Arthur Goldhammer is outstanding – the text is fluent, witty, full of nuance and enjoyable asides. Doesn’t read like a translation at all.

So I’ll be mining it for quotes for years. Convinced yet?

June 30, 2014

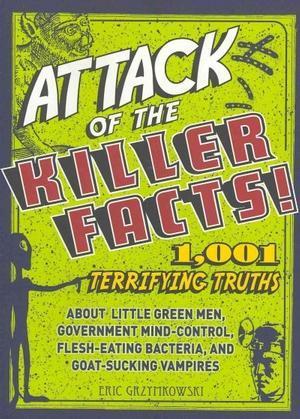

Please steal these killer facts: a crib sheet for advocacy on aid, development, inequality etc

Regular FP2P readers will be heartily sick of used to me banging on about the importance of ‘killer facts‘ in NGO advocacy and general communications.  Recently, I was asked to put together some crib sheets for Oxfam’s big cheeses, who are more than happy for me to spread the love to you lot. So here are some highlights from 8 pages of KFs, with sources (full document here: Killer fact collection, June 2014).

Recently, I was asked to put together some crib sheets for Oxfam’s big cheeses, who are more than happy for me to spread the love to you lot. So here are some highlights from 8 pages of KFs, with sources (full document here: Killer fact collection, June 2014).

Development Success

Income Poverty: Worldwide, the proportion of people living in extreme income poverty (< $1.25) has more than halved, falling from 47% to 22% between 1990 and 2010. (Source: UN Millennium Progress Report 2013)

Health: Globally, the mortality rate for children (under-five deaths) fell by 41 per cent—from 87 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990. (Source: UN). In absolute numbers, Under-five deaths have fallen from 12.6 million in 1990 to 6.6 million in 2012. (Source: UNICEF)

Finance for Development

From 1990-2011, total international resource flows to developing countries grew from US$425 million to US$2.1 trillion. Much of this has been driven by rapid expansion in foreign investment in developing countries, growing remittances, and increases in lending (see graph). (Source: Development Initiatives).

Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) remains the main international resource for countries with government spending of less than PPP$500 per person per year. (Source: Development Initiatives)

Locally generated revenue: Government spending in developing countries is now US$5.9 trillion a year, over 40 times the volume of aid. (Source: Development Initiatives)

Humanitarian

Conflict: According to the OECD, half the world’s poor live in conflict-affected or fragile states (Source: OECD DAC); by 2030 it may by two-thirds (Source: Brookings Institution).

In 2014 the world will spend $8 billion on peacekeeping (Source: UN), compared to $1,745 billion total military spending in 2012 (Source: SIPRI) (i.e. peace merits less than half of one percent of war).

‘Natural’ Disasters: The number of weather-related disasters reported has tripled in 30 years (Source: Oxfam).

For all the talk of building long-term resilience, the world spent $532 million to prepare for and prevent disasters in 2011 – and $19.4 billion to respond (so 40 times more spent on cure than on prevention). (Source: Oxfam)

Inequality and taxation

The 85 richest individuals in the world have as much wealth as the poorest half of the global population. (Source: Oxfam). Update: Forbes using 2014 billionaires list, say it’s now down to 67 richest individuals.

More than 1.5 million lives are lost due to high income inequality in rich countries alone, according to a study in the British Medical Journal.

Governments around the world lose around £100bn a year in tax from rich individuals using tax havens. (Source: Oxfam).

Climate Change and Fossil Fuels

Fossil fuel subsidies cost over half a trillion dollars ($500 bn) globally in 2011. Egypt, Indonesia, Pakistan and Venezuela, spend at least twice as much on fossil fuel subsidies as on public health. (Source: ODI.)

Feel free to add your own favourite Killer Facts, (with sources please) or take issue with these ones, not least because I am probably going to have to update this at regular intervals. And here’s our guide to writing your own.

And here’s another page of KFs on inequality and crises, which Ed Cairns has just sent me: The Inequality of Crisis – 1 page of key facts 25 June 2014

June 25, 2014

Off on holiday, back next week. Here’s a cute picture of some puffins

Just got back from Bosnia and Herzegovina (more on that next week), and am now off for a week to Skokholm, an island off the Welsh Coast, where there is nothing to do but look at puffins. Sounds perfect. I may even finish Piketty…….

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers