Duncan Green's Blog, page 188

May 27, 2014

How 4 million people signed up to a campaign to end Violence against Women: case study for your comments

Next up in the draft case studies on ‘active citizenship’ is the story of an amazing campaign from South Asia and beyond. Please comment on the draft paper  [We Can consultation draft May 2014].

[We Can consultation draft May 2014].

We Can End All Violence Against Women (henceforward We Can) is an extraordinary, viral campaign on violence against women (VAW) in South Asia, reaching millions of men and women across six countries and subsequently spreading to other countries in Africa, Europe and the Americas. What’s different about We Can (apart from its scale) is

It is not primarily concerned with changing policies, laws, constitutions or lobbying the authorities. Instead, it aims to go to scale, by changing attitudes and beliefs about gender roles at community level. A special feature is the ‘Change Maker’ approach, which comes with a ritual in the form of the “We Can” pledge to reflect on one’s own practice, end VAW in one’s own life and to talk to 10 others about it.

It seeks to involve men as well as women, with remarkable success

Its origins lie in a South-South exchange: We Can’s methodology was developed from VAW community programmes in Uganda.

Launched in 2004, by 2011 We Can had signed up approximately 3.9 million women and men to be ‘Change Makers’ – advocating for an end to VAW in their homes and communities. Unexpectedly, about half the Change Makers were men. An external evaluation in 2011 conservatively estimated that ‘some 7.4 million women and men who participated in “We Can” and related activities, have started transforming their perceptions of gender roles and VAW, as well as their behaviour.’

Why do such numbers of women and men sign up? Beyond a personal experience of violence (e.g. between their parents), key motivating factors include inspirational individuals (friends, a respected figure and/or We Can activists) and the sense of belonging to a movement. However, would-be activists face real obstacles – threats, ostracism or mockery at the hands of family, neighbours or friends.

As for what such changes in perceptions actually produced in terms of behavioural changes, a regional assessment found that:

‘Within the family, the most common changes, according to the Change Makers, are the reduction or ceasing of physical and emotional violence and abuse, sharing of housework, lifting of restrictions on female mobility, allowing girls to continue in education and denouncing of early marriage. Outside the family, the most common changes include not restricting girls and women from moving outside the home, allowing them to pursue education, not engaging in ‘eve teasing’ (harassment) of girls and greater discussion on the subject.’

Theory of Change

We Can starts from the premise that ‘real change can come only from within, from sustained action at an individual level, born of personal reflection and understanding and replicated on an ever larger scale through demonstration and mutual support. The premise is that people change when they recognise the problem for themselves, see alternatives, and – through understanding, freedom of choice and peer validation – feel empowered to act.’

The campaign adopted the “stages of change” model, based on the work of the NGO Raising Voices in Uganda (see diagram). We Can sees its work as falling into four ‘phases’, corresponding to the phases in the model, although in practice these phases overlap and sometimes converge.

The campaign adopted the “stages of change” model, based on the work of the NGO Raising Voices in Uganda (see diagram). We Can sees its work as falling into four ‘phases’, corresponding to the phases in the model, although in practice these phases overlap and sometimes converge.

We Can’s approach differs from “traditional” Oxfam campaigns, which tend to focus on rallying popular support for specific objectives in policy advocacy. Unlike other OGB campaigns, “We Can” was not Oxfam branded and not formally Oxfam-led. Although Oxfam and ex-Oxfam staff have played an important role throughout.

For the campaign itself, change started with the Change Makers themselves, who in an exercise known as ‘clean the broom before you sweep’ were ‘encouraged first to recognise, understand and address the acceptance of violence in their own lives, attitudes and behaviour before seeking to persuade others to do the same. [thus] the campaign brought the goal of eliminating gender-based violence within the sphere which individuals can hope to influence.’ Even minor changes in attitudes (a boy no longer demanding that his sister bring him water) were seen as significant.

This includes ‘naming as violence actions that are commonly tolerated or accepted… to point up and challenge the action and the attitudes which underpin it, rather than the individuals involved.’ We Can deliberately promoted a broad definition of VAW to include not just physical violence, but exclusion, intimidation and early marriage.

We Can was about ideas (‘VAW is wrong’) rather than specific actions. Change Makers improvised, intervening with families and neighbours in cases of violence, talking with peers about violence, encouraging families and neighbours to educate girls and allow them greater mobility, acting to stop harassment of girls in public spaces and, for male Change Makers, playing a more active role in household chores.

A great deal of thought and effort went into designing communications materials that could reach millions of women and men: From posters to story booklets; street theatre to poetry and songs; seminars to public rallies; bags, caps, t-shirts, badges, stickers, pencil cases and keyrings with the ‘We Can’ logo; comics to television spots; puppets to kites; murals to billboards – a huge range of formal, informal, traditional and popular media is used to bring ‘We Can’ messages to its great variety of potential audiences and activists.

The campaign consciously targeted men. It avoided pointing fingers, focusing on the actions, not the person and enabling men to become Change Makers who acknowledge that they have been violent but can change. The campaign also focussed on youth and depending on alliances and contexts, that meant young men too.

who acknowledge that they have been violent but can change. The campaign also focussed on youth and depending on alliances and contexts, that meant young men too.

One unexpected finding emerging the campaign was that changes in attitudes to domestic violence, particularly among women, were more complex than a simple move from acceptance to rejection. Surveys and interviews found that the beliefs related to violence were more resistant to change than those relating to equality or general statements on women’s rights. ‘While general principles – non-tolerance of violence, community support for women – were upheld, when the issues were more specific, people’s attitudes were less coherent. Just over one third of interviewees did not agree that a man was never justified in hitting his wife, and 37-40% thought that an occasional slap does not amount to domestic violence.’

What seems to have taken place is a shrinking of the space within which VAW is deemed acceptable, but not its total eradication. But these changes are subtle and complex. According to Michaela Raab, who has evaluated the campaign and contributed to developing its strategy development:

‘A whole lot of people have been given a chance to reflect on their attitudes, and some used that to add extra attitudes to the ones they had, or to strengthen some attitudes over others. Maybe some people also abandoned a few ‘old’ attitudes. But people hold many, diverse and often contradictory attitudes. That is normal. You can be against VAW but beat your partner, because, say, you are in a wild rage or because you think you must punish behaviour that could harm the community. One can be a supporter of human rights while committing human rights violations.’

Conclusion? The We Can campaign in South Asia offers an inspiring example of how to work at scale to change entrenched attitudes and practices. It combines a deep understanding of the nature of power, nuanced approaches to local context, and high levels of ambition to achieve real changes in the lives of millions of men and women. It is no surprise that it has inspired similar campaigns around the world.

And here’s a two minute flavour of the campaign from a Bangladeshi We Can activist with the wonderful name of Beauty Ara.

And in case you missed them, previously posted case studies were on Labour Rights in Indonesia, and Community Protection Committees in DRC.

May 26, 2014

Links I liked

The World before Social media. So how come my desk is still messier than this? [h/t Bonnie Koenig]

Kate Raworth worries that even economist good guys like Ha-Joon Chang ignore planetary boundaries

Brilliant powerpoint fodder from the ONE Campaign. 12 Data visualizations that illustrate poverty’s biggest challenges. Sadly, ‘interactive copulation of data’ in chart 5 isn’t nearly as interesting as it sounds.

Essential reading for inequality wonks. Science magazine edition on inequality, science and big data [h/t Chris Blattman]

You’d have to be pretty harsh to disapprove of this. South Sudanese kids do the Pharrell Williams Happy thing, at the instigation of a street children charity

South-South exploitation is no different, it’s just more honest. Vedanta Mine Owner Anil Agarawal gives a speech to a conference full of business people in Bangalore, mocking the Zambian Government for selling him their minerals far too cheaply (click the caption symbol for Hindi-English translation)

May 22, 2014

The case for democracy – a new study on India, South Africa and Brazil (shame it’s not much good – missed opportunity)

The ODI is a 10 minute train ride from my home, so I’m easily tempted out of my lair for the occasional lunchtime meeting. Last week it was the launch  of ‘Democracy Works: The Democratic Alternative from the South’, a paper on the three ‘rapidly developing democracies’ of Brazil, India and South Africa, co-authored by the Legatum Institute and South Africa’s Centre for Development and Enterprise (not ODI, who merely hosted the launch). I was underwhelmed.

of ‘Democracy Works: The Democratic Alternative from the South’, a paper on the three ‘rapidly developing democracies’ of Brazil, India and South Africa, co-authored by the Legatum Institute and South Africa’s Centre for Development and Enterprise (not ODI, who merely hosted the launch). I was underwhelmed.

Which is a shame, because the topic is great – China’s rise and the West’s economic implosion are undermining arguments for democratic and open systems around the world. The report quotes Jacob Zuma: “the economic crisis facing countries in the West has put a question mark on the paradigm and approaches which a few years ago were celebrated as dogma to be worshipped.”

The authors respond with a vigorous defence of democracy, broadly defined (not just elections):

‘The story of these three countries shows that inclusive growth is possible in a democracy; that democracy is not an obstacle to growth; and that democracy can in some cases be an enormous advantage to states pursuing high-growth strategies. Democracies can accomplish things that cannot be done in authoritarian states. Both elected leaders and their citizens can use the many rights, freedoms, processes, and institutions that comprise democracy to improve institutions when they falter or fail: fight the scourge of corruption; argue for rule of law, an independent judiciary, better legislation, and regulations; give legitimacy, and create support for policies which may at first seem difficult to accept.’

The panellists at the ODI avoided the temptation of saying democracy is a universal panacea: ‘it is empirically false that democracies grow faster than autocracies’, and settled for saying that democracy is not incompatible with growth, and as the previous para argues, even has some advantages.

By basing itself on actually existing democracies in the South, the report avoids what ODI boss Kevin Watkins called Bill Easterly’s ‘disastrous’ mistake of ‘establishing an evolutionary scale with the US at the top’ (I agree with Kev in my forthcoming review of Easterly’s new book, the Tyranny of Experts for an IMF magazine, and will post it here once it’s out).

The report also highlights the importance of ‘constitutional moments’ when new constitutions, agreed after periods of struggle and conflict, open up politics to new ideas and players, as in Brazil or South Africa.

So why was I underwhelmed?

Firstly the report’s unashamedly liberal capitalist stance produced some serious blind spots. Although the panellists denied it, lots of the talk of liberalization, bringing in the private sector on infrastructure and services, cutting fiscal deficits etc sounded pretty Washington Consensus (at least in its later variants). PPPs anyone?

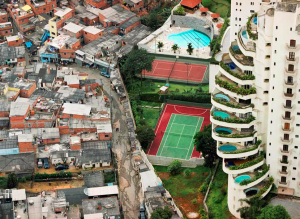

So there is lots of vague language on ‘fairness’ and ‘inclusive growth’, but no serious discussion of inequality or redistribution, including the obviously critical question of why inequality is falling in Brazil, but not in South Africa and India. Instead, the focus is on efficiency and ‘unleashing the private sector’, for example by not overtaxing it – it could have been written by the IMF.

Second, if you’re going to study new democracies in the South, an interesting question is whether they differ from the old ones in the North, and if so how? But when I asked the panellists, they replied that there was really nothing to add to de Toqueville - democracy is democracy, anywhere and at all times. But surely it’s worth exploring possible differences, for example in the shifting balance between collective and individual rights; the role of participatory budget processes (Brazil); judicial activism in India; combined insider-outsider activism in South Africa (protesters dancing and singing outside the courthouse to keep the judges honest) or the relative efficacy of the nation state and more dynamic sub-national bodies such as cities or states in federal systems? Didn’t see much sign of any of that.

Instead what is presented is a curiously emaciated conception of democracy as a set of rules and top-down institutions, busily fighting corruption and fiscal indiscipline before periodically subjecting themselves to elections. And at times the conclusions get pretty banal: ‘democratic elections provide a mechanism for removing leaders’. Who new?

Instead what is presented is a curiously emaciated conception of democracy as a set of rules and top-down institutions, busily fighting corruption and fiscal indiscipline before periodically subjecting themselves to elections. And at times the conclusions get pretty banal: ‘democratic elections provide a mechanism for removing leaders’. Who new?

The report explicitly focuses on the economy and growth record, but ignores the important discussions in South Africa and elsewhere on whether you can have a ‘democratic developmental state‘, or whether growth take-offs necessarily involve a period of autocracy, as in the East Asian variant. And for my money, Dani Rodrik had more to say on all this in his paper on institutions and the quality of growth published back in 1999, which concluded, based on a sample of 90 countries from 1970-89:

Democracies yield long-run growth rates that are more predictable.

Democracies produce greater short-term stability.

Democracies handle adverse shocks much better.

Democracies deliver better distributional outcomes.

Rodrik argued that this is the case because democracy has more feedback loops – government reformers face lots of opposition (so there are fewer big booms), but also much better information when things start to go wrong (so fewer busts). In autocracies no-one wants to tell the General (we know what happens to messengers…..). See chapter 5 of Rodrik’s great book ‘One Economics, Many Recipes’ for more.

Back to the report – some papers stimulate because they make you argue with them in your head and think about what’s missing – this is one of those, and in that spirit, I would recommend it. And of course, if I’ve been unfair, I’m sure the authors will put me right – that’s the joy of blogs.

May 21, 2014

New research shows aid agencies get better results if they stop trying to control their people on the ground, especially in complex environments (and performance monitoring can make it worse)

This fascinating excerpt from a recent Owen Barder speech to the little-known-but-huge Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) covers two new papers  on the management of development interventions, with big potential implications:

on the management of development interventions, with big potential implications:

‘[First] a study of the evaluations of 10,000 aid projects over the last ten years from nine different development organizations. In this paper Dan Honig, from Harvard University, looks at whether different kinds of projects have been successful in different contexts, and he looks at the impact of organizational devolution within aid agencies. He takes all this data and does some regression analysis to try to determine the factors that affect the success of aid projects.

Dan finds, as you would expect, that aid projects are much less likely to succeed in complex or fragile environments, such as in post-conflict countries, and that more complex projects are less likely to be successful than simple projects.

So far, you don’t really need a Harvard academic to tell you this. The interesting part of his findings is that aid agencies that allow a large degree of autonomy to their people on the ground and in implementing agencies see a much lower decline in performance for projects in a complex environment than do agencies which exert a higher degree of monitoring and control.

According to Dan’s numbers, USAID projects scores are about 20% worse in fragile countries than in more simple environments. But if USAID had the same amount of organisational autonomy as DFID, Dan’s results suggest their project success would fall by only about 2% when they work in fragile countries. So Dan Honig’s paper confirms what you might expect: more likely it is that things will change in unexpected ways, the more important it is to have power and decision-making sit with the people who can see that change coming and respond to it.

The second paper I want to tell you about was written by Imran Rasul and Dan Rogge from University College London. They have assembled an extraordinary dataset of 4,700 public sector projects in Nigeria. They have hand coded independent assessments of the projects’ completion rate and quality, and the complexity of the project; and they have conducted a rigorous survey to quantify the management practices of the 63 different organisations responsible for those projects.

The second paper I want to tell you about was written by Imran Rasul and Dan Rogge from University College London. They have assembled an extraordinary dataset of 4,700 public sector projects in Nigeria. They have hand coded independent assessments of the projects’ completion rate and quality, and the complexity of the project; and they have conducted a rigorous survey to quantify the management practices of the 63 different organisations responsible for those projects.

Rasul and Rogge also find that more complex projects have lower success rates than simple ones, which is what you would expect. And they also find a strong statistically significant effect from schemes to create incentives for the bureaucrats and to measure performance – but these effects are negative, not positive, and much more negative for complex projects than for simple ones. Rasul and Rogge have some quite detailed information about organizational incentives, and so they are able to provide some evidence about what matters.

In summary, they find that freedom to adapt and respond improves results for most programmes but most especially for complex projects. They find that incentives schemes make very little difference either way – presumably because the organisations carrying out the work are motivated by intrinsic motivations. And they find that performance monitoring has a significant negative effect on results. Rasul and Roge show that there is a modest complementarity between incentives and autonomy. They get a correlation coefficient of about 24%. One interpretation of this is that where organisations are able to measure results, they are more likely to be willing or able to grant autonomy to the implementing agents.

The important thing in their data, however, is that it is the autonomy, not the results measurement, which is bringing about the improvement. It follows that the results agenda is likely to improve project effectiveness when it is used instead of micromanagement of inputs and processes, but likely to make little or no difference if it is used on top of that micromanagement, as has often been the case with official aid agencies in recent years.’

Sounds plausible – does that resonate with a lot of aid agency staff outside HQ? Over to you

May 20, 2014

Who Wants to Farm? Hardly any young people, it seems. Should/Could that change?

Since I started globetrotting many decades years ago, I’ve always asked peasants and farm labourers a simple question – ‘would you like your kids to become farmers?’ Across continents, the answer has hardly ever been ‘yes’. That creates a bit of a problem for the ‘peasant romantic’ wing of the aid business, who are then forced to argue that either a) ‘they don’t know what they really want/they’ve been brainwashed by the media’ – always a dangerous position for those who claim to listen to poor people, or b) ‘ah yes, but that’s because poor farmers have a crap life, and they would change their minds if they got land, access to markets etc etc’, which kind of makes sense, but could do with a bit of evidence to back it up.

Step forward Jennifer Leavy and Naomi Hossain, in ‘Who Wants to Farm?’ a recent IDS paper that explores exactly this topic. The paper combines a

The exception?

literature review with an analysis of focus group discussions and household case studies with almost 1500 people in 23 rural, urban and peri-urban communities in Asia, Africa and Latin America. In addition to the ‘who wants to farm?’ question, the researchers wanted to find out if the food price spike had increased the incentives to farm, as economists have predicted (answer- it hasn’t), and the ‘conditions under which capable and enterprising youth are being attracted to farming.’

The literature review shows an intriguing and unintended consequence of the spread of education – a ‘generational break’ in family and community traditions of smallholder and small-scale farming. This has been compounded by the spread of communications and media, which means that young rural people are more aware of the alternatives: ‘young people speak movingly about the sorrow they feel witnessing their small farmer parents’ often desperately hard struggles to earn a living’. Put bluntly, parents and kids alike think school is a way out of farming, not a way into it. This is particularly true where economies are creating lots of new jobs in factories and towns.

Young women seem particularly keen to escape. Here’s Miss S, a 19 year old migrant job-seeker in Indonesia:

‘I never want to be a farmer, ever … I don’t to work under the sun; my skin will be darker. My mother said that I shouldn’t be a farmer; the [earnings] are not enough to provide for life; it doesn’t have a future; it’d be better to look for a job in the city… It is better becoming a factory worker; I don’t have to work under the heat, it is not dirty. The wage can be used to buy a cell phone, clothes, cosmetics, bags or other things needed by a teenager. It can be saved for parents, too.’

While not sharing the peasant romantic view of the world (heck, I live in Brixton), I do think there’s a need to encourage more young people into agriculture, both because in most places the non-farm economy is not providing enough decent jobs, and because labour intensive agriculture remains a crucial initial path to equitable growth in many countries. What to do? One significant finding in the paper is that the standard policy recipes are not enough to do the trick; government and others somehow have to make it cool to farm:

the future?

‘It was clear that people considered material assistance in accessing land and inputs, while necessary, would not be enough to make farming attractive to young people, citing a need for successful role models in agriculture. Not only that, there was a strong sense that government had a key role to play in creating the right signals that agriculture is a valued sector and farming a worthwhile profession.’

The paper concludes:

‘Agriculture’s lack of appeal to young people reflects i) lack of effective public investment in small holder farming and the public infrastructure needed to link to markets; ii) constrained access to land and uncertain access to inputs among young people, including land fragmentation in many countries in past few decades; and iii) social change resulting from rapid increases in mass education provision but which have often resulted in a perceived decline in the status of agriculture.

But in digging deeper, the research also finds that agriculture could be made more appealing to young people, with the right kinds of measures and support. First, public policies need to improve the fit between the aspirations of young people and opportunities in agriculture and agri-food more broadly. This could include providing the right kinds of training at appropriate levels to reflect the demands of the job market and broader public investment. Second, an important factor in enabling young people to see the potential of different employment choices, in agriculture and other sectors, is the presence of positive, successful role models.

Finally, a strong message emerging from across all the countries in this research is that farmers, across all generations, need support for accessing markets and to improve productivity, such as access to inputs and in the uptake of modern technologies. It is clear that in a time when food prices are volatile, such policies would help to reduce or mitigate other areas of uncertainty in farming and would go some way towards creating the kind of dynamic agricultural sector that will drive poverty-reducing growth as well as attracting the ‘talent’ of future generations.’

May 19, 2014

Supporting labour rights in Indonesia’s sportswear factories (Nike, Adidas etc). Draft case study for your comments

I’d like to continue picking your brains on the drafts of a series of case studies I’ve been working on. Next up is some long term advocacy on labour rights in Indonesia. Here’s the full draft case study for your comment (PC case study Indonesia Labour Rights Project May 2014).

From 1997-2013 Oxfam Australia’s Indonesian labour rights project (ILRP) worked to help achieve “sustainable livelihoods for workers” in factories in Indonesia that form part of global supply chains for major sportswear brands. As a result of sustained campaigns, the world’s largest sportswear brands, such as Nike and Adidas now take workers’ rights more seriously than a great majority of other transnational companies, including smaller sportswear companies.

What Happened? The ILRP used a combination of country-level capacity building and convening/brokering conversations between supplier  companies, workers and others to build trust and find collective solutions. In addition, the ILRP also provided international campaign support when unions were experiencing harassment (dismissal, suspension) by factory management and the unions had exhausted internal remediation efforts.

companies, workers and others to build trust and find collective solutions. In addition, the ILRP also provided international campaign support when unions were experiencing harassment (dismissal, suspension) by factory management and the unions had exhausted internal remediation efforts.

Results and outcomes: Within Indonesia, the campaign led to the agreement of an industry-wide Protocol on Freedom of Association signed in June 2011. By September 2013, the total number of adidas, Nike, New Balance, Puma, Asics and Pentlands’ suppliers had reached 71 signatories and the number of workers covered exceeded 700,000.

Within the protocol there are some specific wins for worker organisations, including Union officials getting time off for union work, being allowed to collect dues and to give information to members. More fundamentally, the Protocol is an acceptance of the legitimacy of unions, their right to represent workers, and their right to negotiate on their behalf, clear advances over many global codes of conduct.

What is not made explicit in the protocol but has happened as a side effect, is the improvement in communication between the brands and the unions, which in the past had been very tense and is now more constructive. Some of the most significant impacts were on gender relations and the roles of women within the labour movement.

Globally, the Indonesia work played an important part in broader progress, eg Nike’s decision in 2011 to change its manufacturing processes with reduced exposure to toxins (toluene). Or the 2012 decision by Nike and Adidas to limit use of short-term contracts.

Power Analysis: The principal power relations can be summarised as

Blockers:

The economic power of brands over suppliers and supplier companies over workers. Buying companies put pressure on their suppliers, who in turn put pressure on their workforce, resulting in widespread labour rights violations and undermining the effectiveness of codes of conduct and the application of national and international laws and standards.

In Indonesia, the social power of men over women (including within the trade union movement and frequent sexual harassment by male supervisors of female workers).

Parts of the trade union movement suffer from the legacy of the Suharto era in Indonesia, notably in the form of corporatist trade unions aligned to particular political interests rather than those of their members. Some unions continue to actively cooperate with factory managers to suppress worker activism.

Drivers/sources of power working in favour of the ILRP objective:

The power of consumers and active citizens in Australia and other richer countries. Companies do not want to risk the reputation of their brand.

A growing women’s movement in Indonesia.

An active (albeit fragmented) trade union movement emerging after the fall of Suharto in 1998. Garment and footwear unions have successfully come together in recent years.

An organised and motivated international movement and network of activist groups like the Play Fair Alliance.

Change Hypothesis: Oxfam’s hypothesis was that empowerment of workers, particularly women, requires the removal of impediments that prevent individuals from acting. These include personal factors that deter activism, such as the need to work long hours to make more money, fear of harassment and lack of knowledge of their rights. Obstacles also include weak enforcement of legal requirements by both company and public officials.

Change Hypothesis: Oxfam’s hypothesis was that empowerment of workers, particularly women, requires the removal of impediments that prevent individuals from acting. These include personal factors that deter activism, such as the need to work long hours to make more money, fear of harassment and lack of knowledge of their rights. Obstacles also include weak enforcement of legal requirements by both company and public officials.

Change Strategy: The change strategy seeks enforcement of existing laws and conventions (ILO and Ruggie Principles) rather than changes to the law, which is understood to be the role of Indonesian civil society and not the place of Oxfam. It combined four components:

Promoting Corporate Accountability:

Facilitating constructive dialogue between the private sector and worker organizations

Educating and influencing the private sector, including direct engagement (providing resources to the private sector such as the decent work protocol film and the ‘Checking up on Labour Rights’ publication);

Influencing the broader corporate accountability debate through research and discussion.

Strengthening Workplace Rights within company Supply Chains

Facilitating dialogue between workers and international sportswear company representatives

Building worker capacity to understand international supply chains and available redress mechanisms (training on how to research companies, understand codes of conduct etc.)

Supporting specific factory campaigns when unions faced discrimination/dismissals and wanted international campaign support.

Active citizenship: Engaging Citizens to Help Influence Change and Promote Labour Rights

Engaging and informing citizens/consumers/investors to urge companies to uphold workers’ rights.

Gender Justice and Empowerment

Gender and leadership training for worker organizations, particularly women workers;

Embedding gender justice in labour rights work, for example insisting on women worker participation in decent work dialogues and corporate accountability training and highlighting gender issues as a major component of responsible supply chain practice.

Huge staff commitment was regularly required to help those in the negotiations overcome moments of doubt and crisis, when the entire process ground to a halt, amid acrimony and threats of walk-outs. Some of the causes for disagreement were cultural, eg the brands’ failure to understand the symbolic significance to the trade unions of physically signing the Protocol document when it was finalised. Cultural translation and diplomacy were required in both directions – with the brands and (via some particularly dedicated national staff) with the unions, in a constant effort to maintain relationships, repair damage and get people back in the room.

One unexpected side effect of the ILRP was to improve trust and collaboration between different Indonesian trade unions, (as part of the legacy of corporatism under Suharto, a newly independent union movement includes at least 5 separate independent unions working in the garment sector).

Wider lessons: One important lesson is the need for stamina, long term relationship building, problem solving and long-term commitment. More than a decade of consistent campaign pressure created the environment in which sportswear brands were prepared to sit down and negotiate the FOA Protocol. Such commitment is hard to achieve in an aid business based on multi-year programme cycles, and constant financial pressures.

A further lesson of working in such multi-stakeholder initiatives is that individuals matter, as do corporate structures.

Conclusions: The ILRP is an example not just of active citizenship, but of leverage, through a combination of Australian and international consumer pressure on sportswear companies, playing a supportive role in national level talks and supporting individual workplace campaigns.

Its judicious and careful combination of capacity building, brokering conversations and relationships (which turned into negotiations) between workers, suppliers and brands, and international campaigns, enabled the ILRP to have an impact disproportionate to its size.

Such work was enormously demanding, requiring dedicated, talented staff able to network with a wide range of players, see events through the eyes of both workers and companies, and build trust between all sides.

Previous case studies: civilian protection in the DRC

May 18, 2014

Links I liked

Well you seemed to approve of the return of links I liked, so I’m giving it a regular Monday morning slot.

‘We must do something. This is something. So let’s do it.’ How Yes Minister would have loved hashtags. [cartoon h/t Foreign Policy]

The Weekly Piketty:

Dani Rodrik reviews the new guru on the block with surprisingly faint praise

Inequality insurance: tax rates on companies adjust automatically with their levels of pay inequality. Intriguing proposal from nobel economist Robert Shiller

Meanwhile in the non-Piketty world

Must read if you’re interested in social change. Can disruptive power create new social movements?

$100bn well spent. The World Bank’s Marcelo Giugale celebrates and reviews the impact of debt relief relief on Africa

But a World Bank report finds that no one reads (most) World Bank reports (luckily, Marcelo was writing in the Huffington Post).

Admiration for the IPCC soars even higher when you see what they have to do to get sign off on their reports.

US per capita cheese consumption correlates with deaths from becoming tangled in bedsheets. Treat yourself to some Spurious correlations

Tabloid headlines without the sexism. Brilliant.

Finally, I really hope this isn’t photoshopped. [h/t Bonnie Koenig]

May 15, 2014

Why is Coca-Cola championing land rights at the UN?

I usually try and minimize Oxfam’s excessive tendency for trumpet-blowing, but this one from Oxfam America’s private sector czar, Chris Jochnick, looks  worth it – some real progress in working on land rights with the epitome of consumer capitalism

worth it – some real progress in working on land rights with the epitome of consumer capitalism

This week at the UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS), Coca Cola publicly declared that “land grabs” are unacceptable and urged governments to strengthen land rights. That’s a big turn for the world’s largest brand – until very recently, Coca-Cola was in denial about land conflicts. The company’s quick evolution is emblematic of a sea change on land rights in the food and beverage industry over the last few months. That’s a major boost for land rights champions and good news for corporate campaigners. Here’s why.

A little more than a year ago, Oxfam launched Behind the Brands (BtB) – a public campaign targeting the ten largest food and beverage companies around a range of supply chain issues. Among those issues, land rights have been of particular concern to Oxfam (see prior reports here and here). So called “land grabbing” from small farmers and communities is a major threat across the developing world, where much land has yet to be formally titled (in Sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of land has yet to be registered) and can be easily seized to make way for foreign investors and industrial export crops like soy, palm oil and sugar. The ten companies targeted by Behind the Brands were oblivious to the issue – 7 of them (including Coca Cola) got the worst score on our public scorecard for not even mentioning land in any public documents, let alone doing anything substantive about land conflicts.

A few months into BtB, Oxfam focused more attention on land, launching a report that tied Coca-Cola, Pepsico and Associated British Foods to land conflicts linked to sugar. We made three “asks” of the companies – (1) “know and show” impacts on land (by disclosing suppliers and undertaking/publishing impact studies on land conflicts in the supply chain); (2) commit to “zero tolerance for land grabbing” and putting a clause on land rights and Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) into all supplier codes and (3) be a public advocate for land rights at global, national and industry fora.

We spent much time with land experts, NGO advocates and company insiders in developing those asks – and were told that most of it was a reach, but we’d never get a major MNC to use the term “land grabs” let alone declare “zero tolerance”. Going into the push, a senior Coca-Cola exec told me we were barking up the wrong tree – Coca-Cola did auditing all around the world and never came across land conflicts. Fresh off our prior very successful BtB push on gender (targeting Nestle, Mars and Mondelez), we were undeterred.

Alongside the land report, Oxfam put pressure on the three companies through public demonstrations, social media and outreach to consumers and investors. We had conversations with the CEOs and kept in close touch with our company counterparts. In a mere six weeks, Coca-Cola met our “asks”, declaring “zero tolerance for land grabs” and forcing all of its suppliers to abide by a far-reaching definition of FPIC (covering not just indigenous people, but all affected communities). This was no small step. Coca Cola has a presence in 200 countries, it is the largest purchaser of sugar in the world, and it has some of the most robust auditing protocols in the business.

Pepsi followed shortly thereafter, similarly committing to “zero tolerance for land grabbing”. Today, one year after launching BtB, 8 of the 10 targeted companies have committed to FPIC (Mondelez and Danone still lagging). That is truly remarkable. By way of comparison, advocacy organizations like Oxfam have been pushing the oil and mining industries for over a decade to adopt FPIC policies, and uptake – while finally starting — is still very soft.

Of course, people will say that talk is cheap – any company can “make a commitment”; but in this case, there are reasons to believe. First, Coke and Pepsi agreements with Oxfam came with immediate disclosure of their top sugar suppliers. This opened the door on incredibly opaque supply chains and overnight created national news and government action in Cambodia and Brazil, where communities have been fighting land grabs by local sugar mills – now explicitly connected to Coca Cola and Pepsi and their zero tolerance commitment.

Second, getting commitments from Coke and Pepsi has set a ball rolling, influencing the other companies, and more importantly, the major producers and traders who hold even greater influence over conditions on farms. In the wake of the food and beverage company commitments, Cargill stated last month at a World Bank event that it also respected FPIC. Another major producer told Oxfam that they would now be forced to adopt FPIC too because of Coke’s pressure.

Third, corporate public advocacy represents a critical, largely untapped, vehicle to raise awareness and legitimize strong standards. This week at the  UN CFS meeting, we are already seeing the fruits of company commitments to champion land rights. Global brands like Coke and Pepsi have influence via their marketing, political relationships, business networks that goes far beyond their respective supply chains. However uncomfortable, we need these “strange bedfellows” as we push for stronger laws and oversight at the global and national levels (some thoughts on how Oxfam manages these tricky relations here).

UN CFS meeting, we are already seeing the fruits of company commitments to champion land rights. Global brands like Coke and Pepsi have influence via their marketing, political relationships, business networks that goes far beyond their respective supply chains. However uncomfortable, we need these “strange bedfellows” as we push for stronger laws and oversight at the global and national levels (some thoughts on how Oxfam manages these tricky relations here).

One final reason for optimism – our power is only growing. The pressure that Oxfam, as part of a wider movement of consumers, institutional investors, students, NGO allies, community groups, was able to muster to move these companies is on the rise. This civil society influence is abetted by social media innovations, more connected north-south movements and a more forward-looking generation of business insiders. We may well be back on the street fighting Coke tomorrow, but today we should enjoy seeing the world’s most powerful brand put to good work.

May 14, 2014

Feminists in Development Organizations: important new book for anyone (including not-particularly-feminists) trying to influence their institution

At first glance, a book called called ‘Feminists in Development Organizations’ looks like a bit of aid biz navel gazing. But if you are working in a large  bureaucracy and want it to do more on just about any big issue (women’s rights, but also environmentalism, disabled rights, tertiary education, urban livelihoods), this book is worth a read.

bureaucracy and want it to do more on just about any big issue (women’s rights, but also environmentalism, disabled rights, tertiary education, urban livelihoods), this book is worth a read.

Feminist Bureaucrats (the authors’ preferred title) is written by a network of gender specialists in aid agencies and NGOs, who have been supporting each other over the years in trying to push women’s rights higher up the agenda of their organizations.

It’s hard work, not least because ‘a feminist bureaucrat appears a contradiction in terms’, an uncomfortable insider-outsider position where you can easily be written off both as an unhelpful activist by your bosses and not-so-feminist colleagues, and as a sell-out by the more ‘outsider’ wing of the feminist movement. Even victories can be frustrating, since they are so often partial, e.g. your organization adopts the language of women’s rights but promptly instrumentalizes it into ‘girls’ education is good for growth’. Cue gnashing of teeth.

In a concluding chapter the editors, Rosalind Eyben (ex IDS) and Laura Turquet (UN Women) argue that the trick is to understand and exploit ‘the advantages of living on the edge’. Feminist bureaucrats need to be

‘Tempered radicals, seeking a succession of small wins that, accumulatively and over time, they hope may reduce inequity and promote social justice. Their tempered radicalism places them, voluntarily, on the border, the edge, or the periphery of the development agencies that employ them. Yet despite being a personal choice, the feeling of ambiguity about their location is uncomfortable.’

But working on the edge offers four advantages (though these blessings look pretty mixed to me)

‘A sense of powerlessness’ creates radicalization and a sense of solidarity both with marginalized women everywhere and with fellow sufferers in other organizations.

‘Reduced visibility’: however much feminist bureaucrats ‘crave legitimacy from the broader feminist movement’ they are often more effective when working ‘under the radar, at things management is likely to disapprove of.’

‘Critical consciousness’: Maintaining a critical independence from your organization, and relying on your personal network for support and sustenance. While you may be tempted to slag off foot-dragging bosses in public, the authors recommend guerrilla tactics, such as discreetly mobilizing outsider networks (‘you may want to read paragraph X in the draft document and send in your comments’).

‘Two way relationships’: don’t just hang out with your feminist mates, build relationships with others in the bureaucracy, swap favours etc (as true of internal advocacy as external) and be nice. As Patti O’Neill of the OECD argues ‘we need to avoid being ‘the finger-wagging gender police’.

The editors conclude with a practical checklist on how to work on the inside

Building external and internal alliances

Leveraging outside pressure

Creating win-win situations

Preparing for and seizing opportunities

Coping with bureaucratic resistance (eg bypassing middle management and going to the top… ‘to not bang pointlessly on a firmly closed door, but to find a side door that can be pushed open’)

In many ways, this is all about applying the advocacy tools we use to influence governments, companies etc to achieving change within our own organizations (alliances, win-wins, implementation gaps, relationships, spotting and seizing windows of opportunity etc).

But the added delicacy here is that of loyalty and identification. Unless they are very odd indeed, everyone working in an institution has multiple loyalties (to their employer, their team, their wider network, their community, their family, their pets) and there are often tensions between them. Navigating these tensions with integrity is an essential part of your job.

But the added delicacy here is that of loyalty and identification. Unless they are very odd indeed, everyone working in an institution has multiple loyalties (to their employer, their team, their wider network, their community, their family, their pets) and there are often tensions between them. Navigating these tensions with integrity is an essential part of your job.

But judging from this book, and my own experience in Oxfam, that navigation is particularly frustrating for gender specialists. Why is that? Are their beliefs uniquely rejected by their organizations? (hard to buy that in Oxfam at least). Is it because working on these issues is far more personal and immediate than identifying with some more conceptual tribe (governance advisers, bloggers)? Or that the gap between lip service and reality is particularly wide?

At this point, having lit the blue touch paper, I think I will retire and leave it to you…….

May 13, 2014

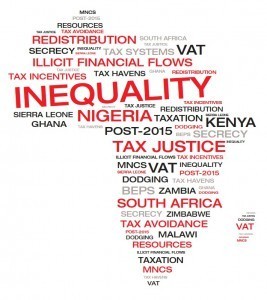

Aid must change in order to tackle inequality: the OECD responds to Angus Deaton

Guest post from Jon Lomøy, Director of the OECD Development Co-operation Directorate (DCD)

Official development assistance – or aid – is under fire. In The Great Escape, Angus Deaton argues that, “far from being a prescription for eliminating poverty, the aid illusion is actually an obstacle to improving the lives of the poor.”

Yet used properly, “smart aid” can be very effective in improving lives and confronting the very issue that Deaton’s book focuses on, and which US President Obama has called the “defining challenge of our time”: rising inequalities.

As a recent UNDP report shows, more than three-quarters of the global population lives in countries where household income inequality has increased since the 1990s. In fact, today many countries face the highest inequality levels since the end of World War II.

There is clearly moral ground for arguing that it is unjust for the bottom half of the world’s population to own only as much as the world’s richest 85 people. Above and beyond this, however, academics, think tanks, and international organizations such as the OECD have found that rising inequalities threaten political stability, erode social cohesion and curb economic growth.

It is not surprising, then, that reduction of socio-economic inequality has moved to the centre of global discussions on the post-2015 goals. The OECD, responsible for monitoring official development assistance (ODA) and other financial flows for development, is complementing these discussions by exploring ways to better use existing financial resources – and mobilise additional ones – to promote inclusive and sustainable development. This includes redefining what we mean by ODA, as well as looking at the ways it can best be used to complement other forms of finance.

While the relative share of concessional public finance – what we traditionally refer to as “aid” – is shrinking compared to new sources of finance for development, this is still a particularly important instrument to address poverty and inequality in many countries – especially those affected by conflict and fragility, where it is difficult and risky to invest.

But to do this effectively, what we know as aid must change and adapt to the needs and priorities set by the countries themselves. Traditional aid must work in untraditional ways.

Smart aid can, for example, help countries finance their own development using domestic resources. Colombia used official development assistance to the tune of just US$15,000 (two technical missions to Colombia in 2012) to fund a capacity development programme for tax administrators. Tax revenues collected by local authorities jumped from US$3.3million to US$5.83million in just one year. Rather than eroding the social contract between citizens and states – as Deaton argues that it does – aid used in this way is likely to increase citizen’s confidence in the state by seriously bolstering the social benefits the government is able to provide them.

Smart aid can, for example, help countries finance their own development using domestic resources. Colombia used official development assistance to the tune of just US$15,000 (two technical missions to Colombia in 2012) to fund a capacity development programme for tax administrators. Tax revenues collected by local authorities jumped from US$3.3million to US$5.83million in just one year. Rather than eroding the social contract between citizens and states – as Deaton argues that it does – aid used in this way is likely to increase citizen’s confidence in the state by seriously bolstering the social benefits the government is able to provide them.

A recently published OECD report shows that providers of development co-operation can also help developing countries confront the challenges of illicit financial flows. Large sums of money – likely to exceed the annual volume of total official development assistance – are illegally transferred out of developing countries every year, depriving the host country of essential revenues. Multinational companies, for instance, use so-called transfer pricing to reduce their tax burden by positioning their profits in countries with low corporate taxes.

A US$10,000 project in Kenya (the cost of two workshops in Kenya that provided advice to the Kenyan Revenue Authority – KRA – on transfer pricing audits) enabled the tax authorities to negotiate a transfer pricing adjustment, contributing to an increase in tax revenues of US$12.9million. Subsequent transfer pricing adjustments by the KRA led to additional tax revenues: from US$52million for the year ending 30 June 2012 to US$85million in 2013. The KRA states that the assistance and advice provided by the workshops has been a major contributor to achieving these increases.

What’s more, development co-operation can be used to mobilise additional financial resources by providing the conditions needed to attract private investment through mechanisms that reduce risk. For example, government-provided ODA can be used to offer guarantees for private investors; or different sources of finance can be “blended” to spread the risk over a group of lenders (the syndicate), one of which is often a multilateral development bank.

These are just some of the ways in which resources can be mobilised through the smart use of development co-operation to help states reduce socio-economic inequalities, finance policies that enable more people to benefit from inclusive economic growth, and provide public services such as education.

Later this year, the OECD will publish its Development Cooperation Report 2014: Mobilising Resources for Sustainable Development. This provides an overview of existing sources of finance for sustainable development, as well as a number of financial and policy instruments that can be used to mobilise additional resources.

Critics are not wrong in questioning how aid is used. We at the OECD – and our member countries – are also doing so to ensure that we learn from the  past to build better and more fit-for-purpose assistance. Times have changed, and so must public development finance. But it would be wrong, as Duncan Green says in his review of Deaton’s book, to throw the baby out with the bathwater and simply stop providing this assistance. One may argue that aid is actually one of the better instruments we have available for redistributing a share –albeit an admittedly small share – of our enormous global wealth to countries and people where it can make a great difference, thus reducing global inequalities.

past to build better and more fit-for-purpose assistance. Times have changed, and so must public development finance. But it would be wrong, as Duncan Green says in his review of Deaton’s book, to throw the baby out with the bathwater and simply stop providing this assistance. One may argue that aid is actually one of the better instruments we have available for redistributing a share –albeit an admittedly small share – of our enormous global wealth to countries and people where it can make a great difference, thus reducing global inequalities.

Part of the “aid illusion” is thinking that aid can’t change.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers