Duncan Green's Blog, page 191

April 9, 2014

What about the 1 in 7? Important progress in getting DFID (and other donors) to get serious on disability

Disability campaigners Mosharraf Hossain and Julia Modern on a new report on disability and development

Back in 1988, I was denied a job in the Bangladesh civil service. This wasn’t because I didn’t have the skills to do the job – I had a Masters in Economics from the University of Dhaka – but because I am disabled. I contracted polio at the age of three, and was left with a mobility impairment, which according to the rules then in place meant I was excluded from being a civil servant.

You might think this sounds outrageous, but this kind of discrimination is still all too common around the world. Over the last few months, the UK Parliament’s Select Committee on International Development has been holding an inquiry looking at disability and development, and it has heard countless stories like mine, and worse: like the disabled woman in West Africa who reported that when she presented at a hospital in the early stages of labour, health workers laughed at her and asked how on earth she could have managed to get pregnant. The Select Committee, which is a parliamentary body set up to monitor the activities of the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), decided to hold this inquiry because they had been told again and again by organisations like ours that the aid system was not delivering for disabled people. They found that this is true.

An inaccessible well built under the NUSAF II project in Uganda, supported by the World Bank. Image copyright Edson Ngirabakunzi and Joseph Malinga

The report that the Committee has released today tells a compelling story. DFID has a reputation for being one the most progressive donors on disability (although it’s been overtaken by Australia in recent years), but the Select Committee’s evidence shows that even at DFID only 5% of bilateral aid spending is on programmes that are designed to benefit disabled people. With 15% of the world’s population being disabled, this clearly isn’t enough.

Worse still, many development programmes are – inadvertently or not – designed in ways that exclude disabled people, such as the World Bank-funded project in Uganda that installed boreholes with steps, which people who use wheelchairs can’t access.

This kind of exclusion is a major cause of poverty, and in some cases is leading to the world’s one billion disabled people falling even further behind the rest of their communities. As Bob McMullan, one of the witnesses at the inquiry pointed out, if any country with one billion people had such low employment, education and health outcomes as the world’s disabled population, it would probably be at the top of international development priorities. However, we know how to change the situation.

In Bangladesh, disabled people came together in Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs) and we defeated the discriminatory policy that excluded disabled people from the civil service. I could have that job if I applied now. There are also some great examples of donors working well with disabled people, including at DFID – for example the changes that were made to a social protection programme in Zimbabwe based on consultation with DPOs, which led to a dramatic increase in the number of disabled people that the programme reached.

Over the last year or so, we have been very encouraged by the actions of Lynne Featherstone MP, one of the Ministers at DFID, who has consistently championed the rights of disabled people. The Minister recently announced a commitment that from now on all new school buildings that DFID supports will be designed to accessible standards that include disabled people.

But we share the Select Committee’s concern that the current support for inclusion at DFID is carried by a few key individuals who will in all likelihood move on, and we want to see the Department being more ambitious about what they can achieve. The Committee’s report recommends that DFID put in place several key mechanisms to make sure disability gets mainstreamed across the organisation, rather than staying a niche issue that individuals work on if they have a personal interest, including the following:

a disability strategy with clear targets and timescales;

a larger team of staff working on disability, including ‘champions’ within each country team and a senior sponsor; and

strong reporting processes to ensure accountability.

The report also contains a welcome emphasis on the central role of disabled people in this process, calling for DFID to actively encourage and

Mosharraf Hossain with UK Minister Lynne Featherstone MP, as she signs a declaration committing the UK to including disabled people in the post-2015 negotiations

support disabled people’s leadership, and to seek their guidance on how to design, implement and monitor programmes. Our experience working with DPOs in Africa and Asia over the last 30 years demonstrates how important this element is: disabled people are the best experts on their own development, and truly empowering them to get involved in the development process is vital. With the publication of this report, a very important step has been taken towards making aid more inclusive.

Because this is an official select committee report, DFID must provide a government response setting out how it will meet the recommendations made. We look forward with much excitement to this response, and to seeing DFID take immediate action to increase education of disabled children, employment of disabled youth and investment for the health of disabled people in low and middle-income countries.

Making DFID’s aid more inclusive of disabled people will be transformative, not only for disabled people themselves, but for whole communities. In her evidence to the inquiry Lorraine Wapling described how an employment project for disabled people in Malawi has helped the whole community:

‘One community leader, completely spontaneously, said to me, “It has made a huge difference. Now that disabled people are benefiting our community, the whole community has come out of poverty. [...] Before, they were dependent; they were drawing our resources. Now they are productive, it means the whole community has a better potential.” That, for me, represents what we mean by value for money’.

Mosharraf Hossain is Director of Policy and Influencing and Julia Modern, Parliamentary Liaison Manager at UK based ADD International. which works with disability movements in 8 countries in Africa and Asia, challenging the barriers and discrimination faced by disabled people.

April 8, 2014

What’s the future role and structure of aid and aid donors? Some options

If I told you, I’d have to shoot you

Yesterday saw the announcement that foreign aid has defied economic and political gravity and reached a record high of $135bn in 2013. The news came as I headed off for a fascinating discussion on reforming the aid system at the ODI. Under Chatham House rules alas, so no names or institutions (ODI gave me a pass on crediting them as hosts), but they included aid types from across Europe, researchers, and a sprinkling of NGOs and retired diplomats.

The underlying dilemma was, I think, how to respond to a world where the big challenges are less and less about shipping cash from ‘North’ to ‘South’, whether because the distinction is no longer useful (rise of the middle income countries, ever-more variable geometry of international alliances and partnerships), or because the issue is a global collective action problem (climate change, arms trade), or because money (or lack of it) is not the main problem/solution (fragile states).

Among the traditional donors (this discussion wasn’t about the new arrivals on the aid scene), the current institutional options seem to be:

Integrating aid with the broader foreign affairs function, and foreign affairs takes the lead (Norway, Denmark);

A development agency within the ministry of foreign affairs leads on policy and implementation (Australia, Canada, Ireland, Netherlands)

A ministry does policy and a separate executing agency, including development banks, spends the money (France, Germany, Japan, US)

A single separate ministry runs both policy and implementation (UK)

But which, if any, of these are best suited to the new world order? Some of the points that arose in the discussion included:

Reforms and new approaches typically emerge when events/’something new’ combine with a ‘felt urgency’ and political leadership – eg 9/11 or the 1970s oil shock. That generates a period of innovation and cross-departmental cooperation for 3-5 years, before institutional siloes reassert themselves and the system reverts to the status quo.

A single ‘ministry of everything’ has downsides – specialist ministries (defence, diplomacy, development) accumulate ‘siloes of expertise’ that are actually very important (don’t ask a social development adviser to run a war or build a bridge).

Governments with big aid budgets need a separate department, or else the money will distort the incentives and operations of the host ministry (‘the tail wagging the dog’).

Keeping aid under the ministry of foreign affairs makes sense when foreign policy is primarily driven by altruism (the Nordics), but not when the country has an active foreign policy based on national interest (US, UK). (‘development is normative; foreign affairs is functional’; ‘there is a risk of instrumentalization’).

Whatever structure we propose has to be highly flexible – we have no idea what will be the medium term outcome of today’s big geopolitical questions (China v Japan; Russia v Europe; the disintegration of the 20th Century settlement in the Middle East).

One of the side effects of the UK’s extraordinary (and very welcome) commitment to reaching 0.7 is a marked reluctance to shake things up in any way – the risks of doing so are all downside (rocking boats, babies and bathwater etc). Understandable, but at some point, the UK will have to rethink its aid arrangements, if this discussion is anything to go by.

My conclusion was that we do need a new way of thinking about the challenge of international development that goes beyond obsolete divisions of North-South, or ever-more complicated subsets of them (LDCs, LICs, MICs, fragile and conflict states, Small Island Developing States, all of which are contested and overlapping). One way to rethink would be to start with three different kinds of problem and think through the institutional arrangements best suited to each:

National problems to which the answer is primarily money (some aspects of health and education, social protection, humanitarian emergencies) need a traditional aid spending ministry

National problems to which the answer is something else (e.g. thinking and working politically, convening and brokering solutions, testing new approaches) need a new kind of approach that offers more expertise and less pressure to sign big cheques

Collective action problems between governments (tax havens, climate change) and issues of policy coherence within governments (eg trade policy, migration) need a network approach across government departments, led from the top, rather than a separate ministry (‘global public goods are currently not represented in any line ministry’)

A further layer of complexity, and potential division of labour, is between national donors and the multilateral system. What aspects of this ever-wider spectrum of activity should DFID and its bilateral friends leave to the World Bank or UN?

If this post is a bit chaotic, that probably reflects the meeting. There was a lack of clarity/agreement on what (if anything) is broken in the current system, let alone how to fix it. But the conversation was definitely interesting enough to warrant a post.

April 7, 2014

“Parlez-vous politics?” Or why working politically is like learning a language

Alina Rocha Menocal of the ODI introduces her new paper

The world of development assistance has come a long way since James Ferguson published his searing critique of the aid establishment in The Anti-Politics Machine: ‘Development,’ Depoliticization and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho in 1994. The (gradual) evolution that different international development actors have undergone to better understand the politics of development has been remarkable – what Carothers and de Gramont have described as an ‘almost revolution’. By now it is pretty widely acknowledged that the challenge of development is not only technical but also profoundly political in nature: it is not simply about what needs to be done (be it building schools or providing vaccinations), but perhaps more fundamentally, about how it is done (processes that facilitate or obstruct change). And this requires coming to grips with the institutional dynamics at work – and the politics underlying them.

So far so good.

But if today most donors buy into the principle that development has to start with the domestic context, making a jump from more technical, one one-size-fits-all models of change to more politically aware programming that is grounded in local realities has proven much more challenging. As I argue in a new ODI paper on “Getting real about politics”, what is needed is a shift not only to think politically but also to work differently – and the process may not be dissimilar to learning a new language.

How so?

“Taking politics seriously” is not about an end- product (the kind of “we’ll do, or, more likely, commission, a nice piece of political economy analysis and be done with it” perspective that tends to be increasingly common among donors, who are often at a loss about the operational implications), but about process; it is not a box that you tick on Monday morning (“taken politics into account?”, “✓”), but a mind-set.

“Taking politics seriously” is not about an end- product (the kind of “we’ll do, or, more likely, commission, a nice piece of political economy analysis and be done with it” perspective that tends to be increasingly common among donors, who are often at a loss about the operational implications), but about process; it is not a box that you tick on Monday morning (“taken politics into account?”, “✓”), but a mind-set.

This raises the question of whether working in a more politically aware manner is something that can actually be learned or is innate. This way of working does seem to call for a particular kind of person – a ‘maverick’ of sorts, less bound by bureaucratic forms and comfortable with the uncertainty and ambiguity of political processes and the dilemmas and trade-offs they present. But the environment these individuals operate within is just as important.

When learning a different language, there is no question that natural ability or predisposition matter, but so does the learning process itself. Young children tend to be more adept at languages because they are less self-conscious and anxious about making mistakes. Rather they run with it and adapt (if not actively improvise) as they go. But they need an environment that is permissive enough to let them learn organically from their own mistakes, rather than shutting them down pre-emptively for fear they may get a word or sentence construction wrong.

The teaching method matters too. If you have a teacher who makes you do sit ups when you get the conjugation of an irregular verb wrong (as I did when I was trying to learn English in Mexico), it will probably not get you very far: the incentives are all wrong and you will simply focus on getting a particular answer right without thinking of the broader picture.

To continue with the metaphor, this is often how the aid system operates. As Elinor Ostrom and her collaborators noted in their now classic study for Sida in 2000, the incentive structures that govern the funding, commissioning, design and implementation of development assistance often militate against efforts to think politically and work differently. The most recent report of the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) on DFID, released last week, is also critical of the agency for failing to learn not only from what works but also from what doesn’t, given the focus on short-term results – a situation that is in no way peculiar to DFID. And Ex-USAId chief Andrew Natsios has written about the worrisome growth of layers and layers of bureaucracy within agencies, which tends to foster a risk-averse culture and to encourage staff, as one aid veteran has put it, “to do things right rather than do the right things.”

So what can be done? Despite the challenges, over the past decade there has been on-going engagement from a variety of stakeholders, including donor  representatives, policymakers, development experts and civil society actors (including NGOs, activists and academics) on how to advance the agenda of taking politics seriously in both thinking and practice. Dedicated communities of practice have emerged to refine understandings of what not only ‘thinking politically’ but also ‘working differently’ might mean and how the potential embedded in this kind of approach can be realised. This is also an on-going and expanding area of engagement within the ODI, in collaboration with other partners.

representatives, policymakers, development experts and civil society actors (including NGOs, activists and academics) on how to advance the agenda of taking politics seriously in both thinking and practice. Dedicated communities of practice have emerged to refine understandings of what not only ‘thinking politically’ but also ‘working differently’ might mean and how the potential embedded in this kind of approach can be realised. This is also an on-going and expanding area of engagement within the ODI, in collaboration with other partners.

A great deal of work remains to be done. But there have been important areas of progress, and very meaningful insights and lessons have emerged. For example, there are ongoing efforts to build up the existing body of evidence of more/less successful initiatives to work in a more politically aware manner, and identify the ingredients that have made a positive contribution (including, among other things, long-term and committed staff, flexible approaches not tied to rigid logframes identified at the start of a project, and a willingness to invest in ideas and relationships that may not pay off immediately). Some international actors are also increasingly willing to act not simply as providers of funds or implementers, but also as facilitators of change – bringing together domestic stakeholders, supporting them in identifying problems and encouraging them to work collaboratively in finding potential solutions.

However, it is also clear that what is needed to get real traction on this agenda is not only or even principally about generating the evidence or documenting examples of where a politically smart approach has made a difference. Rather, it is about altering the way international development actors engage in developing settings, in some cases quite fundamentally. A radical approach is needed – much akin to learning a new language from scratch, within a conducive environment that fosters adaptation, flexibility, ingenuity, and the ability to learn by doing.

April 6, 2014

What are the limits of transparency and technology? From three gurus of the openness movement (Eigen, Rajani, McGee)

After a slightly disappointing ‘wonkwar’ on migration, let’s try a less adversarial format for another big development issue: Transparency and Accountability. I have an instinctive suspicion of anything that sounds like a magic bullet, a cost-free solution, or motherhood and apple pie in general. So the current surge in interest on open data and transparency has me grumbling and sniffing the air. Are politicians just grabbing it as a cheap announcement in austere times? Does it contain some kind of implicit right wing assumptions (an individualist homo economicus maximising market efficiency through open data)? And is there any evidence that transparency actually has much impact on the lives of poor people (after all, the proponents of transparency and results-based agendas are often the same organizations, so I hope they are practicing what they preach….)

I put these fears to three transparency gurus, and here are their fascinating responses, striking in their quality and level of, well, openness. It’s a long read, but I hope you’ll agree, a worthwhile one. Think we’ll just stick with comments on this one – doesn’t feel like a vote would be useful (but let me know if you think otherwise)

What else is needed to make transparency have impact?

Prof. Dr. Peter Eigen, Transparency international (Founder, Chairman of the Advisory Council)

Transparency is not a magic bullet but rather part of the arsenal. Transparency, when combined with accountable and responsive institutions as well as the space for civil society to get involved, is a game changer. These other factors are what make transparency meaningful and useful to build trust, fight corruption and achieve development progress. Alone, transparency may be cost-free but it also falls short on realizing all the promises that have been tied up with it.

But what does transparency really encompass or mean? Transparency can generally be defined as the “characteristic of governments, companies, organisations and individuals of being open in the clear disclosure of information, rules, plans, processes and actions”.

Take the case of public spending. Transparency can be used to follow the money to make sure that promised funds are turned into results for the poorest. In Mexico, “social witnesses” are required by law and have overseen more than $50 billion of public spending and tendering procedures. Findings from Transparency International show that in countries where there is greater openness, more checks-and-balances and better rule of law, more pregnant women have healthy births, more children and young people are educated to read, and more families have access to clean water and sanitation.

But in all of these cases, the ‘magic bullet’ of transparency is more part of a broader magic formula. Open government information is combined with governments that are willing to be held to account, official channels that allow for a government’s accountability and the rule of law, and individuals that are able and wanting to hold their government to account.

When it comes to companies, improving transparency can be used to see what businesses are paying into government coffers in terms of taxes, royalties, licenses and other payments. But again, simply putting the information out in the public domain does not equate to changes in practice or market efficiencies unless there are shareholders, governments and individuals that have the means to convert transparency into changes in policies and actions.

When it comes to companies, improving transparency can be used to see what businesses are paying into government coffers in terms of taxes, royalties, licenses and other payments. But again, simply putting the information out in the public domain does not equate to changes in practice or market efficiencies unless there are shareholders, governments and individuals that have the means to convert transparency into changes in policies and actions.

Transparency International (TI), the organization that I founded over 20 years ago, has seen how much increased openness can lead to real and lasting change when these other pieces of the puzzle are present. TI can be found in more than 100 countries where it has national chapters.

What TI has learned is that it is not just the quantity of information provided but the quality: is it comparable, timely, accessible, understandable and useful? It is also about matching the supply of information with the demand for certain types of information.

Information may be “cost-free”, but there may be no one interested in it unless it meets these characteristics and speaks to people’s needs.

Sorting this out for development is what will make possible a “data revolution” as has been called for by the UN and others, rather than creating a deluge of information.

We walk the fine line between just opening the information faucets in the name of “transparency” and providing what is needed to allow individuals to participate, provide oversight, prevent corruption and make informed choices.

Why transparency and technology won’t drive accountability

Rakesh Rajani, Head of Twaweza East Africa and the co-chair of the Open Government Partnership

Ideas that hold the most promise can also be the most deceptive; for their power and allure can mask the inconvenient hard thinking that come in the way of a good story. The use of technology in development, and in particular its potential to close the gap between citizen voice and state responsiveness, is one such idea.

In the past decade, many a development blogpost, newspaper article and YouTube video has gushed about the transformative power of the internet and mobile telephony – in closing information asymmetries, creating pathways for citizen expression and feedback, monitoring service delivery, visualizing data, and creating new possibilities for collective action. At Twaweza, we have claimed that the spread of communication technologies is a ‘game changer’ in East Africa, that the information space has been ‘democratized’ now that the content and methods that used to be the preserve of a few are open to the many, and because facts and ideas can travel in so many directions, so quickly and at little cost. Who cannot be moved by the memes of citizens mapping their neighborhood, or village women reporting the broken water point, or budget visuals that give you simple, color-coded bubbles to follow your money?

That technology can allow us to do interesting things is amply documented. I’ve just reviewed a useful book of several such case studies that the World Bank will launch on April 9. The trouble is that too many of us too much of the time have oversold its promise. Not so long ago grownups would talk as if all one had to do was to sprinkle mobile phones or internet and the persistent, structural imbalances and power asymmetries that had dogged us for decades would melt away. ‘Apps for Africa’ was the new Live Aid and microcredit revolution rolled into one. Thankfully, for the most part, we are past that stage.

With hindsight, it’s tempting to be snide. But it’s not so easy in practice. At Twaweza we’ve supported a number of thoughtful, caring people to roll out seemingly well-designed technology-driven initiatives (see, for example, here, here, here and here), ideas that many smart people from local NGOs and media to the World Bank and prestigious universities found compelling, but that did not live up to their original promise in uptake or fostering accountability. I suspect that we have no monopoly on a particularly high rate of failure, but are simply more willing and able to talk openly about it. Even those that ‘work’ often do not last beyond their initial phases (for example on the limits of Ushahidi see here, here, and here) or transform the underlying constraints they were set up to address. Snazzier forms do not a function make; when the authorities choose to ignore the content there isn’t much difference between a wooden suggestion box and a citizen feedback website with analytics.

So how do we think sensibly about these issues?

First, just because technologies can allow us to collect, store, analyze and communicate data and ideas in unprecedented ways should not lull us to think they can address old, entrenched problems in unprecedented ways. The primary constraints for human action are non-technological in nature. Most people who do not speak up in public meetings have perfectly functioning voices, and training them on better enunciation will not help matters much. Many technology projects have been hampered by inadequate theorizing, by political economy and social movement analysis, and by the lack of reference to historical evidence. And while clear and imaginative thinking is universally valuable, by necessity this analysis needs to be contextual. In particular we need to be particularly cautious about transferring successful use of technology from one place and time to another.

First, just because technologies can allow us to collect, store, analyze and communicate data and ideas in unprecedented ways should not lull us to think they can address old, entrenched problems in unprecedented ways. The primary constraints for human action are non-technological in nature. Most people who do not speak up in public meetings have perfectly functioning voices, and training them on better enunciation will not help matters much. Many technology projects have been hampered by inadequate theorizing, by political economy and social movement analysis, and by the lack of reference to historical evidence. And while clear and imaginative thinking is universally valuable, by necessity this analysis needs to be contextual. In particular we need to be particularly cautious about transferring successful use of technology from one place and time to another.

Second, we need a deep understanding of human motivation; of why people – on both the ‘citizen demand’ and ‘responsive state’ sides – would choose to pay attention, take action, and persist when setbacks happen, and a more granular (than just ‘citizens’ or ‘authorities’) of who would act. Our assumptions on each of these can be ill informed and poorly thought through, leaving us perplexed on why no one showed up for the thing we built so well. A simple set of questions, such as these (see Fig 3 on page 32) developed by a team evaluating citizen action in our Uwezo initiative, can be instructive.

Third, as Twaweza Advisory Board member Lant Pritchett puts it, however smart we are or well we do our homework, we are bound to not get it right the first (or second or third) time. That being so, what matters is how we test and tweak, and retest and retweak; set up agile feedback loops in a structured manner; and establish internal incentives and external relationships that can foster a culture of iteration and learning. The point here is not to experiment all day in boutique labs with little regard to impact, but rather to integrate experimentation and adaptation at the heart of how we implement at scale.

These lessons arise here in reflecting on the limits of technology to drive accountability, but in fact apply more broadly. And that is the point. Technology and transparency don’t drive anything. People, who organize and at times use technology to do so, do.

Motherhood, apple-pie and openness

Rosemary McGee, Institute of Development Studies (UK), Research and Evidence Component Coordinator of Making All Voices Count, and Technical Advisor to Open Government Partnership

Open Government Partnership

I’ll start by being a typical academic: whether transparency is necessary and important for development purposes depends on one’s definition of a number of terms. First, development. That might mean the extension of market economics to the furthest corners of the globe, the achievement of the MDGs, or the ability of people to imagine the world differently and realise that vision by changing the power relations that disadvantage them.

Second, transparency. To TI, founded 20 years ago, transparency means clear disclosure of information, rules and actions, as in the definition Peter Eigen sets out above. Since then, definition-creep has set in. Lots of terms have come to be connected with it. Is this a definitional issue that only bothers hair-splitters like me, or a real issue that ought to bother all of us?

There’s ‘openness’, which is anything from laissez-faire capitalism and free trade regimes (the economist’s definition), to inter-operability and the access to use and modify data and computer code in a shared environment (the techie’s definition), to a critical attitude to tradition (the open society advocate’s definition). And several more – these are just the three most relevant to the present debate.

Then there’s ‘open government’, which according to the Open Government Partnership means greater civic participation in public affairs, and governments which are more transparent, responsive, accountable, and effective.

And then there is the usage of transparency which treats it as the harbinger of accountability. This puts accountability as the goal, and transparency as one contributing factor, linked to it in an ‘uncertain relationship’, as Jonathan Fox warned several years ago.

‘Openness’ and ‘open government’ may have many effects that are good for people in situations of poverty and marginalization. They may also have effects which are not, and effects which are bad for them, at least relatively speaking. They may ease the corporate pillaging of natural resources or the monopolistic buying-up of subsistence farm land. They may demonize ‘tradition’ in ways that undermine informal institutions on which poor people or minorities depend for their livelihoods or their dignity. Or perhaps they provide a smokescreen behind which governments hone their capacities to spy on suspect citizens. The scope for the bad effects increases exponentially as technologies lower the costs and shorten the timeframes of ‘opening up’, reducing the pressure for careful appraisal.

Whether ‘openness’ and ‘open government’ are good for poor people depends on who is promoting them and using them, and for what. (A recent learning study on assumptions and realities about the users of tech-based transparency and accountability initiatives suggests that, if the ‘who’ and ‘for what’ questions are asked too rarely about the promoters of tech-for-T&A, they are asked even more rarely about the people the promoters claim to be benefitting – which leads straight to the ‘whether’ question, but that’s another story.)

Whether ‘openness’ and ‘open government’ are good for poor people depends on who is promoting them and using them, and for what. (A recent learning study on assumptions and realities about the users of tech-based transparency and accountability initiatives suggests that, if the ‘who’ and ‘for what’ questions are asked too rarely about the promoters of tech-for-T&A, they are asked even more rarely about the people the promoters claim to be benefitting – which leads straight to the ‘whether’ question, but that’s another story.)

I believe that accountability in public and corporate governance is a universally good thing that is good for poor and marginalized people. My belief doesn’t extend universally to all the approaches set out above. Unlike ‘openness’ or ‘open data’, transparency for accountability means a value-based commitment to a particular kind of change, one rooted in principles of human rights and fairness. The Open Government Partnership’s definition of its purpose is rooted in these too (although that may come as a surprise given some of the governments that have been let into the OGP). For governance to get more accountable in any country in the world, African, Asian and Latin American countries, transparency would certainly be necessary, and openness, open data, open government might contribute.

There is not enough evidence yet that transparency does have a positive impact on poor people’s lives, because of the non-linear relationships between transparency and accountability, and between accountability and better lives. The causal chains are long and complex, and include a lot of false starts and dead ends. Programmes like Making All Voices Count, backed by funders who are both proponents of transparency and strongly results-based in orientation, are investing considerably in building more evidence on whether it’s so and, when so, how it happens. But in this field marked by frenetic aid, philanthropic, entrepreneurial and surveillance activity, let’s not leapfrog over the questions of what is being pursued under the heading of ‘transparency’, who is promoting it, and why.

April 4, 2014

Now that’s what I call transformation: Latin America then and now, and Tony Benn RIP

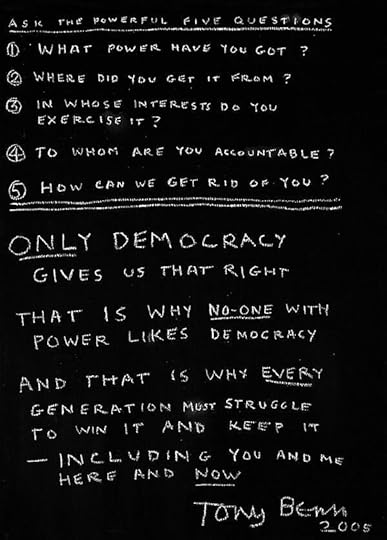

For those of you yet to join the twitterati, here are two images that went viral when I tweeted them recently. First up, the presidents of Brazil, Argentina and Chile, now v 1970s (h/t @rabble). Amazing, eh? It’s actually a bit messier than that- the three military dudes are all Chilean (Messrs Leigh, Pinochet and Merino), but the generals were indeed in power in Argentina and Brazil at that point. Second, a particularly memorable set of ‘questions to the powerful’ suggested by the late Tony Benn. Enjoy.

April 3, 2014

‘How DFID Learns’. Or doesn’t. UK aid watchdog gives it a ‘poor’ (but the rest of us would probably do worse)

The UK Department for International Development’s independent watchdog, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI), has a report out today on ‘how DFID learns’. Or doesn’t. Because the report is critical and gives DFID an overall ‘amber-red’ assessment, defined as ‘programme performs  relatively poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Significant improvements should be made’.

relatively poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Significant improvements should be made’.

I’m not gloating here – in my brief time working at DFID, I was struck by its investment in staff training and the general level of curiosity and intellectual enquiry. I suspect ICAI would be even more critical of NGOs and other aid organizations, so anyone working in research and development should probably spend a few minutes skimming the report.

Here’s the overall assessment:

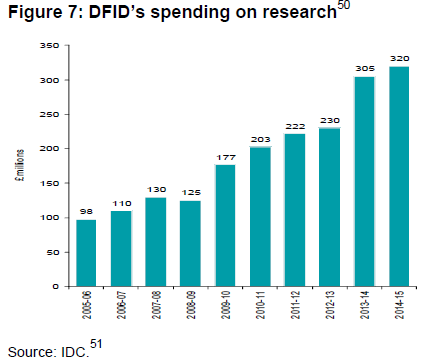

‘DFID has allocated at least £1.2 billion for research, evaluation and personnel development (2011-15) [see graph]. It generates considerable volumes of information, much of which, such as funded research, is publicly available. DFID itself is less good at using it and building on experience so as to turn learning into action. DFID does not clearly identify how its investment in learning links to its performance and delivering better impact. DFID has the potential to be excellent at organisational learning if its best practices become common. DFID staff learn well as individuals. They are highly motivated and DFID provides opportunities and resources for them to learn. DFID is not yet, however, managing all the  elements that contribute to how it learns as a single, integrated system. DFID does not review the costs, benefits and impact of learning. Insufficient priority is placed on learning during implementation. The emphasis on results can lead to a bias to the positive. Learning from both success and failure should be systematically encouraged.’

elements that contribute to how it learns as a single, integrated system. DFID does not review the costs, benefits and impact of learning. Insufficient priority is placed on learning during implementation. The emphasis on results can lead to a bias to the positive. Learning from both success and failure should be systematically encouraged.’

Recognize any of that? Thought so. And here are the report’s recommendations, some of which probably also sound pretty familiar:

1: DFID needs to focus on consistent and continuous organisational learning based on the experience of DFID, its partners and contractors and the measurement of its impact, in particular during the implementation phase of its activities.

2: All DFID managers should be held accountable for conducting continuous reviews from which lessons are drawn about what works and where impact is actually being achieved for intended beneficiaries.

3: All information commissioned and collected (such as annual reviews and evaluations) should be synthesised so that the relevant lessons are accessible and readily useable across the organisation. The focus must be on practical and easy-to-use information. Know-how should be valued as much as knowledge.

4: Staff need to be given more time to acquire experience in the field and share lessons about what works and does not work on the ground.

5: DFID needs to continue to encourage a culture of free and full communication about what does and does not work. Staff should be encouraged always to base their decisions on evidence, without any bias to the positive.’

Some other interesting extracts from the main 40 page report:

Staff turnover: ‘Staff are continuously leaving and joining DFID (sometimes referred to as ‘churn’). Fragile states are particularly vulnerable to high  staff turnover by UK-based staff. For instance, in Afghanistan, DFID informed us that staff turnover is at a rate of 50% per year. We are aware of one project in the Democratic Republic of Congo having had five managers in five years.

staff turnover by UK-based staff. For instance, in Afghanistan, DFID informed us that staff turnover is at a rate of 50% per year. We are aware of one project in the Democratic Republic of Congo having had five managers in five years.

This process represents both a constant gain and loss of knowledge to DFID. When staff depart DFID, their knowledge should be retained in the organisation. Similarly, when staff join DFID, their prior knowledge should be made available to others.’

Learning by failing: ‘During 2013, DFID began to discuss failure in a more open and constructive way than it had previously done. This began substantially with the February blog of the Director General for Country Programmes. Following this, a short video was produced by DFID staff in the Democratic Republic of Congo that discussed failures in a water supply improvement project. This internal video has been catalytic in stimulating discussion about how DFID should be more honest about failure. It has resulted in the introduction of ideas, such as the need to fail fast. During 2013, DFID’s Research and Evidence Division has piloted approaches to discussing failure in ‘fail faires’, where staff come together to identify what can be improved. It is too early to say whether these will support a change of culture in DFID in its attitude to learning from failure, albeit they appear to be a positive innovation.’

(not) Listening to staff and partners: ‘Junior and (even senior) locally employed DFID staff generally ‘only give our opinion if asked’. Generalist, administrative and locally employed staff are not being listened to sufficiently by DFID’s specialists. They often have much experience of how aid is delivered: know-how….. DFID staff do not appear to prioritise how they listen to others. This applies to learning internally and from external sources…. Staff believe that DFID remains too much in a mode of trying to manage or change others rather than listen to and support them.’

All good stuff, but what is lacking is any discussion of the institutional constraints to DFID being able to implement these recommendations – after all, there must be reasons why they haven’t done so already – see Neil McCulloch’s recent piece on the political economy of donors.

Finally, props to the UK government for setting up ICAI in the first place. Really impressive example of rigour, transparency and accountability (more on that topic here next week, when some T&A gurus discuss its limitations).

April 2, 2014

The link between Income Inequality and Public Services is stronger than I realized (thanks to Emma Seery for putting me straight)

Oxfam has been banging on to good effect recently about extreme global inequality in income and wealth. Over many years, we have also been making the case  for universal health and education. It turns out the link between the two is stronger than I’d realized, according to ‘Working for the Many: Public Services fight Inequality’, a new paper published today.

for universal health and education. It turns out the link between the two is stronger than I’d realized, according to ‘Working for the Many: Public Services fight Inequality’, a new paper published today.

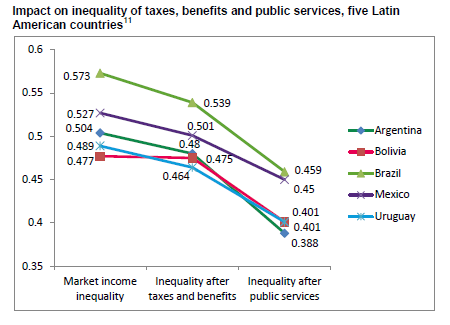

We normally discuss inequality before and after tax (eg it’s progressive taxation that really brings Europe’s inequality down). But recent work published by the OECD and World Bank has put a monetary value on the ‘virtual income’ provided by public services. This produces some startling findings on inequality.

‘Public services mitigate the impact of skewed income distribution, and redistribute by putting ‘virtual income’ into everyone’s pockets. For the poorest, those on meagre salaries, though, this ‘virtual income’ can be as much as – or even more than – their actual income. On average, in OECD countries, public services are worth the equivalent of a huge 76 per cent of the post-tax income of the poorest group, and just 14 per cent of the richest. It is in the context of huge disparities of income that we see the true equalizing power of public services.

The ‘virtual income’ provided by public services reduces income inequality in OECD countries by an average of 20 per cent, and by between 10 and 20 per cent in six Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico and Uruguay – see graph). Evidence from the IMF, Asia, and more than 70 developing and transition countries shows the same underlying patterns in the world’s poorest countries: public services tackle inequality the world over.

In Mexico, and even in Brazil with its award-winning Bolsa Familia cash-transfer scheme, education and healthcare make double the contribution to reducing economic inequality that tax and benefits make alone. But regressive taxation in many Latin American countries, including Brazil, is undermining the potential to combat inequality through fiscal redistribution, and preventing even greater investment in health and education.

In Mexico, and even in Brazil with its award-winning Bolsa Familia cash-transfer scheme, education and healthcare make double the contribution to reducing economic inequality that tax and benefits make alone. But regressive taxation in many Latin American countries, including Brazil, is undermining the potential to combat inequality through fiscal redistribution, and preventing even greater investment in health and education.

This evidence underlines a double imperative for governments: to ensure progressive taxation that can redistribute once when collected and again when spent on inequality-busting public services.’

And seen through the eyes of inequality and redistribution, the private v public debate becomes even starker:

‘Far from being a magical solution to providing universal access to health and education services, private provision of services skews their benefit towards the richest. Amongst the poorest 60 per cent of Indian women, the majority turn to public sector facilities to give birth, whilst the majority of those in the top 40 per cent give birth in a private facility. In three of the best performing Asian countries that have met or are close to meeting Universal Health Coverage – Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Hong Kong – the private sector is serving the richest far more than the poorest. Fortunately, in these cases the public sector has compensated.

Services must be free at point of delivery to reach their inequality-busting potential. Health user fees cause 150 million people around the world to suffer financial catastrophe each year. For the poorest 20 per cent of families in Pakistan, sending all children to a private low-fee school would cost approximately 127 per cent of that household’s income. The trend is the same in Malawi and in rural India.

Whereas public services provide everyone with ‘virtual income’, fighting inequality by putting more in the pockets of the poorest; user fees and private services have the opposite effect. Fees take more away from the actual income of poor people, and private services benefit the richest first and foremost. This is the wrong medicine for the inequality epidemic.’

Smart and important work by Emma Seery and colleagues.

April 1, 2014

Are ‘serious games’ a better way to prepare for climate change than scenario planning?

Had a nice little lightbulb moment last week, when I spoke at a meeting to launch yet another ODI paper. This one, ‘Planning for an Uncertain Future’  summarized some work by ACCRA (the Africa Climate Change Resilience Alliance), of which Oxfam is a member.

summarized some work by ACCRA (the Africa Climate Change Resilience Alliance), of which Oxfam is a member.

The lightbulb in question was making a connection between two issues discussed in previous blog posts: my scepticism on scenario planning, and the ‘serious game’ that game master Pablo Suarez ran for Oxfam a couple of years back. ACCRA has adapted Pablo’s approach to ‘reflective gaming’ (playing the game, but periodically breaking off to consider the implications for real life work in adapting to climate change) and is using it in workshops with district level officials and others in Ethiopia, Uganda and Mozambique to see if it can help build capacity to adapt to the increasing variability of the climate.

Scenario planners claim it prepares you for the uncertain, unpredictable world of complex systems, epitomised by climate change. But judging by the report, and the video below, gaming seems a lot more likely to achieve that aim, across a wider range of people, being both more fun and more obviously connected to real life (‘experiential’).

The ODI found that even in fairly closed, rigid planning systems (eg Ethiopia), participants came to a better understanding of the ‘wiggle room’ available to officials seeking to improve adaptive capacity. However, the limits to wiggle room can be very narrow, unless there are ‘champions of change’ at higher levels. So a good power analysis is an essential starting point (and if it establishes that only 3 or 4 people make all the decisions, it may well be worth customising a game just for those people).

The researchers identified some other interesting outcomes from game-based reflection:

Imagining and considering possible (not just probable) futures over long timescales;

Appreciating that decisions taken in isolation are usually suboptimal;

Understanding that there is seldom a single ‘right’ answer;

Accept the inevitability of short-term shocks and long-term pressures;

Realising that Flexible and Forward-Looking Decision Making (FFDM) ways of working involve not only the district level but also collaboration across institutional, governance and sectoral boundaries;

Experiencing the benefits of doing more with less (discovering synergies);

Gaining confidence in exploring FFDM ways of working, that is, experimenting with different strategies over the course of the game and raising difficult issues in a safe space;

Appreciating that there are many ways in which success can be measured or judged.

I’d also be interested in the gender aspects of this – is women’s participation more or less compared to other kinds of capacity building? Anyway, here’s a nice 5m video showing how people react to the exercise.

Anyone else using this kind of approach?

March 31, 2014

Missing in Action: Why do NGOs Shy Away From Geopolitics?

Didier Jacobs, my strategic adviser equivalent at Oxfam America, wonders why this blog hasn’t mentioned some of the big geopolitical events of recent weeks, and what it says about NGO advocacy.

big geopolitical events of recent weeks, and what it says about NGO advocacy.

Last month, a significant event inflected the world order: Russia invaded Crimea. Not a word about it in these columns so far.

Whether their mission is poverty alleviation, environment protection, or human rights promotion, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have extended their advocacy agenda to every global policy issue: climate change, international trade and finance, peacekeeping, international public health, migration, and so on. NGOs are knee-deep in global public policy… and yet they shy away from geopolitics.

Geopolitics is about countries competing for power in the international community. Key geopolitical questions include:

the prioritization of a country’s national interests

the allocation of its defense budget

the identification of its allies and enemies

its policy regarding the use of force.

For several years, the US foreign policy establishment has been debating bombing Iran’s nuclear facilities. We have a few months of reprieve thanks to an interim agreement. Nevertheless, the possibility of US strikes against Iran remains likely.

What consequences would such strikes have on global poverty? The oil price would shoot up, which could increase food prices. Food price hikes plunged tens of millions people into extreme poverty in 2011. The nascent global economic recovery could be nipped in the bud, with social consequences everywhere. Religious and ethnic strife might worsen in a range of places. In the worst scenario, a full-scale US invasion of Iran would generate a new major – and preventable – humanitarian crisis.

What about a war in the South China Sea? Not a month goes by without more saber-rattling in that neighborhood. The Economist magazine recently charged governments as well as businesses with complacency in the face of what could become the Third World War. It could have mentioned complacent NGOs as well.

That was before Russia intervened in Crimea last month. The phrase “cold war” has now returned to the daily news. While it has somewhat shaken complacency, economic interdependence between Russia and the West is likely to contain the crisis and Crimea may soon join the list of protracted but forgotten geopolitical headaches alongside Abkhazia or South Ossetia, Kosovo or Cyprus.

However, this latest crisis is definitely going to have long-term consequences. We are witnessing cold wars unfolding in slow motion between the West and both Russia and China. It could mean the multiplication of proxy wars among world and regional powers, worsening the overload of the international humanitarian system. It could mean a retreat of civil and political rights as security resumes its status of primary imperative. It could mean a decline in international trade and finance preventing some developing countries from “emerging”.

any of our business?

Even absent deeper enmities, NGOs should be concerned about the geopolitical chess board. The 1990s witnessed significant advances in multilateralism that augured well for development, human rights and the environment: the World Trade Organization, the International Criminal Court, the Kyoto Protocol. Economic growth in China, India or Brazil is great news for global development. However, it has also stalled multilateralism in the 2000s – from G8 to G20 to G0 – as emerging powers want more say while established ones resist giving up their privileges. Addressing the failure of multilateralism is all about geopolitics.

NGOs are involved in geopolitics, but seem hesitant to embrace it. Let’s examine how they handle the four key geopolitical questions posed above.

Prioritization of national interests: the one that NGOs address best. Environmental organizations advocate for environmental issues to top the list in every country, and they can provide specific policy advice on what it means. Likewise, every mission-driven NGO has its own priorities: human rights, women’s rights, agriculture, etc.

The problem is that when everything is important, nothing is important. Political parties and elections arbitrate between priorities at the national level. In many countries, national NGO platforms and big coalition campaigns do a decent job at influencing national priorities. At the global level, the UN General Assembly and the G20 are the closest things we have to an assembly and Senate that set global policy priorities. There is a modicum of coordination among global coalitions of NGOs to influence these priorities, but it has lost cohesion and effectiveness since the heyday of Make Poverty History.

Cohesive and effective?

Influencing defense policy: largely absent from NGOs’ agenda. Yet it is at the top of the agenda of those who really set the pecking order of national interests and define foreign policy. There are many grassroots peace networks bereft of resources (loosely coordinated by United for Peace and Justice in the US), but relatively few professional NGOs specifically dedicated to peace (such as Peace Action in the US). Even those peace NGOs are of modest size compared to their environmental or human rights counterparts. Their common agenda is disarmament, but they generally lack defense expertise.

Identifying allies and enemies: for NGOs, the very proposition seems preposterous. Leaving aside diaspora associations influencing relations between their home and host countries (like the National Iranian American Council), NGOs are part of networks that are truly transnational. They are above the geopolitics that divides countries. It is great indeed that NGOs from all over the world can work in solidarity. However, international enmity does exist out there. In the absence of a vigorous campaign embraced by NGOs of all stripes, the American foreign policy establishment has won the argument that Iran (and tomorrow China?) is an enemy of the United States.

Which leads us to the fourth geopolitical question: when should countries use force? Human rights and humanitarian NGOs defend international law. They are more interested in jus in bello (restraining the use of force to protect civilians) than jus ad bellum (justifying, or not, the use of force in the first place).

Humanitarianism is not geopolitically neutral. Aid can change the dynamics of conflicts. Humanitarian organizations are aware of that and constantly grapple with it. While seeking access to populations in need, they must be careful not to be instrumentalized by conflicting parties as well as by donors under the guise of counter-terrorism or campaigns to “win hearts and minds”.

Some humanitarian NGOs push the envelope by advocating for arms embargoes, ceasefires, and peace negotiations. But they are either ill-equipped or unwilling to influence the substance of such negotiations. Other NGOs specialize in conflict resolution and mediation, the International Crisis Group prominent among them. They provide analysis of the underlying causes of conflicts, advise governments, and sometimes participate directly in diplomacy by mediating between conflicting parties. On the other hand, they hardly engage the public through advocacy campaigns. So their influence is limited to the quality of their analysis and negotiation skills.

Some humanitarian NGOs push the envelope by advocating for arms embargoes, ceasefires, and peace negotiations. But they are either ill-equipped or unwilling to influence the substance of such negotiations. Other NGOs specialize in conflict resolution and mediation, the International Crisis Group prominent among them. They provide analysis of the underlying causes of conflicts, advise governments, and sometimes participate directly in diplomacy by mediating between conflicting parties. On the other hand, they hardly engage the public through advocacy campaigns. So their influence is limited to the quality of their analysis and negotiation skills.

Pushing the envelope even further and treading on jus ad bellum, human rights and humanitarian organizations have advocated for the responsibility to protect civilians. When states fail to protect their citizens, some NGOs occasionally call for international military intervention. While the responsibility to protect is a sound principle, in practice there are not many cases where international force can do more good than harm. (On the other hand, humanitarianism is often instrumentalized for darker designs, like Russia’s protection of Russian-speaking Crimeans.)

Last but not least, the World Federalist Movement champions the criminalization of aggression and thereby addresses the question of the use of force head on. Nevertheless, by approaching the use of force from a legal and transnational perspective without regard to the international enmities that underlie aggressions, it somehow manages to remain above geopolitics, not engaged in it.

Meanwhile, the NGO community remains silent about Ukraine and other shifts of the tectonic plates of geopolitics that underpin future conflicts, like the arms race in East Asia.

NGOs should be conscious that they are geopolitical actors, and reflect on ways in which they can better mitigate the harmful aspects of nations’ competition for power.

Any suggestions for how to do this?

The World Bank tackles Mind and Culture: heads up on the next World Development Report

Even though annual reports by the many fragments of the multilateral system have proliferated in recent years (I can’t keep up any more), the World  Bank’s World Development Report still stands head and shoulders above the rest. And the next one’s theme, WDR 2015: Mind and Culture, due out in November this year, is pretty eye catching. And welcome. There’s not much to read on the report website just yet, so it was useful to get a briefing from WDR team member Steve Commins on his way through London last week (thanks to Save the Children International for hosting the lunchtime meeting, but please don’t put the crisps next to me in future).

Bank’s World Development Report still stands head and shoulders above the rest. And the next one’s theme, WDR 2015: Mind and Culture, due out in November this year, is pretty eye catching. And welcome. There’s not much to read on the report website just yet, so it was useful to get a briefing from WDR team member Steve Commins on his way through London last week (thanks to Save the Children International for hosting the lunchtime meeting, but please don’t put the crisps next to me in future).

According to the brief blurb on the WDR website:

‘The World Development Report 2015 is based on three main ideas: bounds on rationality, which limit individuals’ ability to process information and lead them to rely on rules of thumb; social interdependence, which leads people to care about other people as well as the social norms of their communities; and culture, which provides mental models that influence what individuals pay attention to, perceive, and understand (or misunderstand).

The report has two main goals:

To change the way we think about development problems by integrating knowledge that is now scattered across many disciplines, including behavioral economics, psychology, sociology, anthropology, neuroscience, and political science.

To help development practitioners use the richer understanding of the human actor that emerges from the behavioral sciences in program design, implementation, and evaluation.

The central argument of the Report is that policy design that takes into account psychological and cultural factors will achieve development goals faster. The main tools — affecting prices through taxes, subsidies, and investments; regulating and legislating; and providing information — all remain relevant. But once considered from the perspectives of bounded rationality, social norms, and cultural categories, each tool becomes more complex and more nuanced.’

The conversation at Save highlighted some of the big questions that are likely to surround the report:

Maximalist v Minimalist: Is this just about being more effective at what we are already doing (the Nudge school of benevolent paternalism aimed at things like getting parents to send kids to school) or about doing different things? In economist-speak, is this just about building better utility functions? Steve cited a colleague’s interesting concept of ‘autonomy-enhancing paternalism’ – yes the uppers are trying to influence the lowers, but the intention is to encourage autonomy (literacy, organization, empowerment) rather than automata.

Paradigm shift or new toolkit?: As set out by Steve, the WDR will argue for a fundamental shift to better and more consistently take into account culture, beliefs, and the rich and exciting world beyond the arid reductionism of homo economicus (my word’s not Steve’s). However, busy policy makers always ask ‘what do I do differently on Monday morning.’ For once, I’m going to go with the paradigm shifters – I think the report should concentrate on setting out the big picture, not getting bogged down in producing a new checklist, which will inevitably drag into towards the minimalist end of the spectrum.

Diagnostics: Mind and Culture could open the door to seeing the world in very different ways from the monetary. How do we map different realities – power? Trust? Wellbeing? Faith?

Diagnostics: Mind and Culture could open the door to seeing the world in very different ways from the monetary. How do we map different realities – power? Trust? Wellbeing? Faith?

What level of aid biz navel gazing? Clearly mind and culture is about ‘us’ as much as about ‘them’, how do bounded rationality, social interdependence and mental models help/hinder the typical World Bank (or Oxfam) staffer from being effective in helping people free themselves from poverty?

Who’s the Real Target Audience? Seems to me that the obvious one is yet-to-be-enlightened economists of the rational expectations school. If so, then the report’s content, tone, governance, comms etc should all be tailored accordingly.

Steve came up with a nice soundbite: ‘vinegar v honey – which one attracts the flies?’ to argue that first caricaturing, then slagging off ‘mainstream economists’ is a really terrible way to influence….. mainstream economists. Instead, why not try ‘Hey, here’s the future way of thinking about the human condition: it’s already everywhere in the broader social sciences; it’s already being used by many economists in their work and is only going to expand. We’re going to help you understand it and explain what it means for your work.’ But there will be difficult choices – how far should the report go in diluting a message to make it acceptable to recalcitrant MEs (again, my words)?

Gender: You could write the whole of a WDR on Mind and Culture simply on gender, and I kind of hope they will. Perfect illustration of the limitations of orthodox thinking and the importance of everything else.

Results: the big one. According to Steve, ‘The challenge with all this is that it never easily fits results-based management. We have absorbed this cult of results across the aid business, but many or most important ones cannot be put into a logframe. It’s one of the key aspects of the ‘so whats’ in the report – we’ve all been going in the wrong direction, here’s a better way.’

I could go on (and doubtless will, at some point). The point being that the potential is huge. But we have been here before. WDR’s regularly sound brilliant in the initial stages, then somehow the grind of writing, debate and Bank sign-off produces an all too recognizable World Bank sausage by the end of the process. I hope they can retain some of the originality through to the end product.

Some WDRs leave a lasting legacy; others think without trace. At the moment, I’m optimistic about this one.

And here’s what Robert Chambers has to say on it.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers