Duncan Green's Blog, page 193

March 20, 2014

Is ‘Getting to Zero’ really feasible? The new Chronic Poverty Report

OK, I think we’ll draw a veil over the slightly disappointing migration wonkmassacre wonkfirstroundknockout wonkwar and get on with other stuff.

The latest Chronic Poverty Report (2014-15) was released last week, and I urge you to take a look. It’s a goldmine of analysis, case  studies and graphics (too many for this post, I’ll have to tweet the extras). The subtitle, ‘the road to zero extreme poverty’ is an attempt to influence the post2015 discussion, which is increasingly talking about ‘getting to zero’: eradicating extreme poverty for the first time in history, with 2030 a likely target date. For several years, the Chronic Poverty network has been thinking and writing about how to actually do that, so I hope the post2015 crowd listens.

studies and graphics (too many for this post, I’ll have to tweet the extras). The subtitle, ‘the road to zero extreme poverty’ is an attempt to influence the post2015 discussion, which is increasingly talking about ‘getting to zero’: eradicating extreme poverty for the first time in history, with 2030 a likely target date. For several years, the Chronic Poverty network has been thinking and writing about how to actually do that, so I hope the post2015 crowd listens.

Chronic poverty is different from general poverty: it describes the subset of poor people, (up to 500 million of them), who live permanently below the $1.25 poverty line, often for generations. They consist of a kaleidoscope of excluded groups – children, casual labourers, smallholder farmers, disabled people, indigenous minorities, downtrodden castes, widows, remote communities, the elderly, people with mental health problems, and often an intersecting combination of these.

The standard development recipe of growth + jobs may work for some of these, but not all. How do you help a disabled elderly woman escape from poverty? Microfinance or job creation aren’t going to do the trick: previous reports have stressed the importance of social protection and public services. This one adds more on ending discrimination and the social norms that justify it.

But the most striking message I took away from this report is actually not strictly about chronic poverty. Household-panel surveys in many countries now allow you to track households over a number of years. They show a strikingly high percentage of families that  escape from poverty, only to fall back (see chart). The report argues that preventing people falling back in this way is a ‘low hanging fruit’ in poverty reduction, often ignored by policy makers and donors.

escape from poverty, only to fall back (see chart). The report argues that preventing people falling back in this way is a ‘low hanging fruit’ in poverty reduction, often ignored by policy makers and donors.

This picture of volatility (nicely illustrated with some very powerful life histories dotted around the report) means that in some countries, it may be more effective to concentrate on preventing escapees from falling back, while in others, helping them escape in the first place may be a better investment. The report suggests policies for different combinations of poverty and ‘impoverishment’ (risk of falling back) – see table.

The report doesn’t stop there, it also looks at how to maintain the escape from poverty of those that escape for good (after all, who would want to get to $1.26 a day and stay there?). Policies should pursue three separate but interdependent objectives – the zero poverty ‘tripod’’: tackling chronic poverty, stopping impoverishment (sliding back) and sustaining poverty escapes.

The report argues that ‘There are three policies that address all three legs of this tripod. All three are needed if the eradication of  extreme poverty is to be sustained, and all three require massive global investment. They are social assistance, education and pro-poorest economic growth. For other, more leg-specific policies, see graphic.

extreme poverty is to be sustained, and all three require massive global investment. They are social assistance, education and pro-poorest economic growth. For other, more leg-specific policies, see graphic.

This is where, for me, the report loses its focus a bit, and the launch meeting in which I took part last week only confirmed these doubts. Sure, if you want to get to zero and stay there, you have to attack all 3 legs of the tripod with equal zeal. But in practice, governments and donors have only limited cash, and it seems to me entirely plausible that there are trade-offs between the three pillars of the tripod. So even if they are well intentioned, decision makers are bound to ask ‘what will give us the most poverty reduction for our buck?’ My reading of this report is that in some contexts, its answer would be that prevention (stopping people sliding back) provides a better social return on investment than cure (getting previously poor people above the poverty line). The report may have scored on own goal, inadvertently making the case for not targeting the chronically poor in some situations.

I think it was pushed in this direction both by the fascinating findings from the panel data, and the urge to hop aboard the post2015 bandwagon (you probably know what I think about that one). When I asked ODI’s Andrew Shepherd, the lead author of the report, he acknowledged ‘we strayed deliberately because of Getting to Zero’. But as far as I can see, they didn’t have to. It would have been fine to say ‘if you want to get to zero, there is a huge obstacle you have to overcome – chronic poverty. Here’s what you have to do for that elderly, disabled woman and the 500 million like her. The report could have developed some of its really interesting thinking on tackling the social norms that underpin exclusion and policy neglect, or its concept of ‘pro poorest economic growth’ (focussed on informal economy and migrant labourers).

Instead, including both the churners and the escapers has turned the report into a report about poverty and development in general. It’s actually a rather good one at that, but lots of other people cover that ground, and I regret the loss of focus on the chronically poor.

The launch debate highlighted another intriguing gap in the report. Following on from its definition of extreme poverty as less than $1.25 per head, it has a rather individualistic vision of the problem. It discusses collective action as a means to reduce poverty, but does not see association as an aspect of well being – it doesn’t seem that interested in issues of association (families, communities, social capital).

Don’t get me wrong, the report is a must read, breaking lots of new grounds, with a strong focus on government action (aid is a relatively minor presence), the need to understand the political economy of marginalization, and skilfully bridges the humanitarian and development siloes, while bringing in perspectives from economics and anthropology (when was the last time you saw witchcraft mentioned in one of these reports?).

I hope once the post2015 circus moves on, the Chronic Poverty team can get back to its core business. How about the next report being on the cultural norms and practices underpinning chronic poverty, building on whatever comes out of this year’s World Development Report (on Mind and Culture)?

Is âGetting to Zeroâ really feasible? The new Chronic Poverty Report

OK, I think we’ll draw a veil over the slightly disappointing migration wonkmassacre wonkfirstroundknockout wonkwar and get on with other stuff.

The latest Chronic Poverty Report (2014-15) was released last week, and I urge you to take a look. Itâs a goldmine of analysis, case  studies and graphics (too many for this post, Iâll have to tweet the extras). The subtitle, âthe road to zero extreme povertyâ is an attempt to influence the post2015 discussion, which is increasingly talking about âgetting to zeroâ: eradicating extreme poverty for the first time in history, with 2030 a likely target date. For several years, the Chronic Poverty network has been thinking and writing about how to actually do that, so I hope the post2015 crowd listens.

studies and graphics (too many for this post, Iâll have to tweet the extras). The subtitle, âthe road to zero extreme povertyâ is an attempt to influence the post2015 discussion, which is increasingly talking about âgetting to zeroâ: eradicating extreme poverty for the first time in history, with 2030 a likely target date. For several years, the Chronic Poverty network has been thinking and writing about how to actually do that, so I hope the post2015 crowd listens.

Chronic poverty is different from general poverty: it describes the subset of poor people, (up to 500 million of them), who live permanently below the $1.25 poverty line, often for generations. They consist of a kaleidoscope of excluded groups â children, casual labourers, smallholder farmers, disabled people, indigenous minorities, downtrodden castes, widows, remote communities, the elderly, people with mental health problems, and often an intersecting combination of these.

The standard development recipe of growth + jobs may work for some of these, but not all. How do you help a disabled elderly woman escape from poverty? Microfinance or job creation arenât going to do the trick: previous reports have stressed the importance of social protection and public services. This one adds more on ending discrimination and the social norms that justify it.

But the most striking message I took away from this report is actually not strictly about chronic poverty. Household-panel surveys in many countries now allow you to track households over a number of years. They show a strikingly high percentage of families that  escape from poverty, only to fall back (see chart). The report argues that preventing people falling back in this way is a âlow hanging fruitâ in poverty reduction, often ignored by policy makers and donors.

escape from poverty, only to fall back (see chart). The report argues that preventing people falling back in this way is a âlow hanging fruitâ in poverty reduction, often ignored by policy makers and donors.

This picture of volatility (nicely illustrated with some very powerful life histories dotted around the report) means that in some countries, it may be more effective to concentrate on preventing escapees from falling back, while in others, helping them escape in the first place may be a better investment. The report suggests policies for different combinations of poverty and âimpoverishmentâ (risk of falling back) â see table.

The report doesnât stop there, it also looks at how to maintain the escape from poverty of those that escape for good (after all, who would want to get to $1.26 a day and stay there?). Policies should pursue three separate but interdependent objectives â the zero poverty âtripodââ: tackling chronic poverty, stopping impoverishment (sliding back) and sustaining poverty escapes.

The report argues that âThere are three policies that address all three legs of this tripod. All three are needed if the eradication of  extreme poverty is to be sustained, and all three require massive global investment. They are social assistance, education and pro-poorest economic growth. For other, more leg-specific policies, see graphic.

extreme poverty is to be sustained, and all three require massive global investment. They are social assistance, education and pro-poorest economic growth. For other, more leg-specific policies, see graphic.

This is where, for me, the report loses its focus a bit, and the launch meeting in which I took part last week only confirmed these doubts. Sure, if you want to get to zero and stay there, you have to attack all 3 legs of the tripod with equal zeal. But in practice, governments and donors have only limited cash, and it seems to me entirely plausible that there are trade-offs between the three pillars of the tripod. So even if they are well intentioned, decision makers are bound to ask âwhat will give us the most poverty reduction for our buck?â My reading of this report is that in some contexts, its answer would be that prevention (stopping people sliding back) provides a better social return on investment than cure (getting previously poor people above the poverty line). The report may have scored on own goal, inadvertently making the case for not targeting the chronically poor in some situations.

I think it was pushed in this direction both by the fascinating findings from the panel data, and the urge to hop aboard the post2015 bandwagon (you probably know what I think about that one). When I asked ODIâs Andrew Shepherd, the lead author of the report, he acknowledged âwe strayed deliberately because of Getting to Zeroâ. But as far as I can see, they didnât have to. It would have been fine to say âif you want to get to zero, there is a huge obstacle you have to overcome â chronic poverty. Hereâs what you have to do for that elderly, disabled woman and the 500 million like her. The report could have developed some of its really interesting thinking on tackling the social norms that underpin exclusion and policy neglect, or its concept of âpro poorest economic growthâ (focussed on informal economy and migrant labourers).

Instead, including both the churners and the escapers has turned the report into a report about poverty and development in general. Itâs actually a rather good one at that, but lots of other people cover that ground, and I regret the loss of focus on the chronically poor.

The launch debate highlighted another intriguing gap in the report. Following on from its definition of extreme poverty as less than $1.25 per head, it has a rather individualistic vision of the problem. It discusses collective action as a means to reduce poverty, but does not see association as an aspect of well being – it doesnât seem that interested in issues of association (families, communities, social capital).

Donât get me wrong, the report is a must read, breaking lots of new grounds, with a strong focus on government action (aid is a relatively minor presence), the need to understand the political economy of marginalization, and skilfully bridges the humanitarian and development siloes, while bringing in perspectives from economics and anthropology (when was the last time you saw witchcraft mentioned in one of these reports?).

I hope once the post2015 circus moves on, the Chronic Poverty team can get back to its core business. How about the next report being on the cultural norms and practices underpinning chronic poverty, building on whatever comes out of this yearâs World Development Report (on Mind and Culture)?

March 19, 2014

Migration and Development: Who Bears the Burden of Proof? Justin Sandefur replies to Paul Collier

Justin Sandefur responds to yesterday’s post by Paul Collier on the impact of migration on developing countries, and you get to vote

The global diaspora of educated Africans, Asians, and Latin Americans living in the developed world stand accused of undermining the development of their countries of origin.

Paul Collier’s recent book, Exodus, makes the case for strict ceilings on the movement of people from poor countries to rich ones.  My colleague Michael Clemens and I already reviewed the book at length for Foreign Affairs (ungated here), but Duncan asked me to respond to the specific issue Paul raised in his recent post for this blog: that skilled migration from some low-income countries is so high that it undermines the development prospects of people “left behind”.

I suspect many people reading this blog in Europe or North America share Professor Collier’s skepticism about skilled migration. You are not racist or xenophobic.  You are concerned about the plight of the global poor, and you welcome diversity in your community. But you worry that maybe Paul’s right.  Maybe the fate of your university-educated Haitian neighbor down the street, earning a good salary and sending her kids to good schools since moving to the UK, is a distraction from, and maybe even a hindrance to, reducing poverty in Haiti.

Before we begin, itâs important to note that weâre not really debating whether the rate of skilled emigration fro Freetown to London or Port-au-Prince to Miami is too fast or too slow. We’re really talking about whether to deport your neighbor.  Or whether to refuse her a visa in the first place, and consign her and her family to a future of low wage employment, bad schools, and preventable disease “back where they came from.”  That is the policy proposal on the table for your consideration.

My argument is that the burden of proof here should be heavy, and it should rest on the shoulders of those who would build walls and tear apart families. Â If you think the prosecution has met that burden of proof, here are three reasons to reconsider.

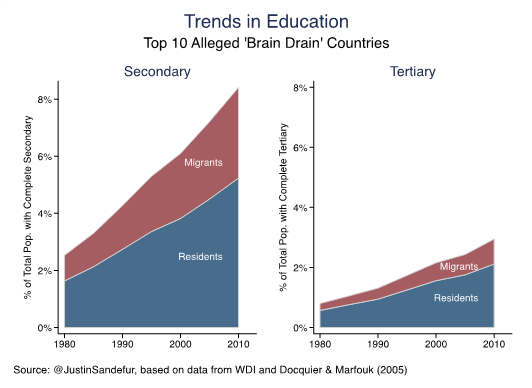

1. Â Empirically, the alleged âbrain drainâ from poor countries does not exist.

Yesterday, Prof. Collier worried that while China wins from an emigration âbrain gainâ, Haiti and other small, poor countries lose out to âbrain drainâ. Â So letâs have a look at the numbers.

Based on research by economists Frederic Docquier and Abdeslam Marfouk, I compiled a list of the ten low-income countries with the highest rates of skilled emigration.  They are: Haiti (84% of secondary grads living overseas in an OECD country circa 2000 â though this exaggerates a bit, by counting Haitians educated abroad), Gambia (63%), Sierra Leone (53%), Mozambique (45%), Liberia (45%), Kenya (38%), Uganda (36%), Rwanda (26%), Guinea Bissau (24%), and Afghanistan (23%).

You might suspect that such high emigration among educated people has led to stagnation or decline in the share of skilled workers. Â You’d be wrong.

You might suspect that such high emigration among educated people has led to stagnation or decline in the share of skilled workers. Â You’d be wrong.

In the low-income countries with the highest levels of skill emigration, the stock of skilled workers left behind is going up, not down. Â Even after you exclude the migrants, the prevalence of both secondary and tertiary education more than doubled! This simple fact is often lost in fretting over a “brain drain”.

Skeptical readers will rightly note that the counterfactual here is unclear: maybe residentsâ education wouldâve been even higher without emigration. Thereâs good reason to think the opposite. The opportunity to join the diaspora is a key motivation for pursuing higher education.  Multiple studies looking at natural experiments from Cape Verde, to Fiji, to Nepal, have all found that new migration opportunities led to more investment in schooling not only for migrants, but for people who didnât end up migrating as well.

2. Â Emigration is not an alternative to other drivers of development, it is a cause.

Perhaps you feel letting poor people move to better opportunities is a distraction from the real work of promoting development within  the geographic borders of poor countries. Â Rather than migration, we need more aid, more investment, and better governance in poor countries.

the geographic borders of poor countries. Â Rather than migration, we need more aid, more investment, and better governance in poor countries.

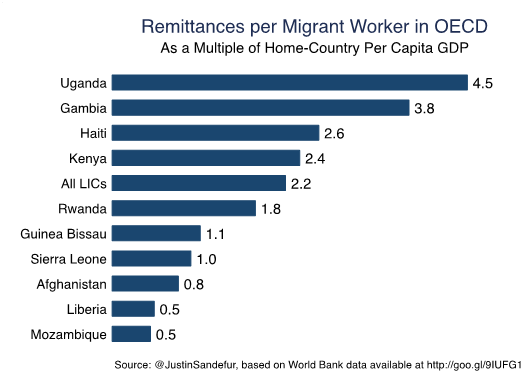

Consider Haiti again.  The World Bank’s bilateral remittance and migration matrices show that the 670,000 adult Haitians living in the OECD sent home about $1,700 per migrant per year. Thatâs well over double Haiti’s $670 per capita GDP.  And Haiti is not unique. On average, across the whole set of low income countries, each migrant to the OECD sends home more than double her countryâs per capita GDP each year.

Remittances took a dip during the 2008 financial crisis, and have not yet fully recovered, but they still clock in at roughly $400 billion worldwide, compared to a total foreign aid budget globally of about $125 billion.

Itâs true that skilled workers earn more back in Haiti than the unskilled, but they also remit considerably more as well.

And itâs not just remittances. Migrants also significantly boost FDI back to their country of origin. Thereâs also tantalizing new evidence emerging from various corners of the globe about the effects that migrant diaspora have on home-country governance — some of which (to be fair) are summarized in Exodus. From Mali to Moldova and back to Cape Verde again, there is growing evidence migration exposes citizens to democratic values and strengthens demands for accountability and good governance at home.

3. Â There is zero evidence that trapping skilled workers in places with few skilled jobs will generate growth

The argument put forward in Prof. Collierâs post yesterday is that emigration deprives countries of the talented and skilled individuals that will drive broad-based growth. Itâs undeniable that education has huge economic and social payoffs for individuals and their families. And we probably all agree that in order for Haiti to grow in the long run, attracting and retaining more skilled workers will be a necessary step.

The argument put forward in Prof. Collierâs post yesterday is that emigration deprives countries of the talented and skilled individuals that will drive broad-based growth. Itâs undeniable that education has huge economic and social payoffs for individuals and their families. And we probably all agree that in order for Haiti to grow in the long run, attracting and retaining more skilled workers will be a necessary step.

But itâs also clear that education alone is insufficient for economic development without public infrastructure, functioning credit markets, tolerable government, etcâ¦. the sorts of things places like Haiti and Afghanistan often lack. Knowing that those ingredients are lacking, are we confident enough to deny people the right to leave?

Bear in mind there is no study out there, from Haiti or anywhere else, showing any empirical evidence that migration restrictions have contributed to development. So this is a huge, evidence-free gamble weâre taking with other peopleâs lives.

Economist Branko Milanovic estimates that 80% of global inequality is explained by your country of birth. Through education and migration, skilled migrants from low-income countries have struggled to overcome their unlucky draw in this birth lottery. They owe us no explanation. Their success stories are what we mean by development. Theyâre also a key motivation driving young people in poor countries into higher education, as well as a vital source of development finance far in excess of official aid.

So feel free to oppose immigration from poor countries if you’d like, but letâs not fool ourselves into thinking there’s anything altruistic about that stance.

And now it’s time to vote. You can tick more than one box. Please add your views in comments, and if you feel they warrant a separate post, get in touch.

March 18, 2014

How does emigration affect countries-of-origin? Paul Collier kicks off a debate on migration

Take a seat people, youâre in for a treat. Paul Collier kicks off an exchange with Justin Sandefur on that hottest of hot topics, migration. Iâve asked them to focus on the impact on poor countries, as most of the press debate concentrates on the impact in the North. Justin replies tomorrow and (if I can work the new software) you will then get to vote. Enjoy.

How does emigration affect the people left behind in poor countries? That many countries still provide little hope of even basic  prosperity to their citizens is the great global challenge of our century. It is a vital matter that the poorest countries catch up with the rich world, but it will require decades of sustained high growth. To see how emigration might affect this process of convergence we need some understanding of why poor countries have remained poor. Poverty persists in very poor countries because of weak political institutions, dysfunctional social attitudes, and a lack of skills. These all make it difficult to harness economic opportunities. Emigration can either help or hinder convergence depending upon who leaves, how many leave, and for how long they go.

prosperity to their citizens is the great global challenge of our century. It is a vital matter that the poorest countries catch up with the rich world, but it will require decades of sustained high growth. To see how emigration might affect this process of convergence we need some understanding of why poor countries have remained poor. Poverty persists in very poor countries because of weak political institutions, dysfunctional social attitudes, and a lack of skills. These all make it difficult to harness economic opportunities. Emigration can either help or hinder convergence depending upon who leaves, how many leave, and for how long they go.

Potentially the most important effect of emigration is on political institutions and social attitudes. There is now solid evidence that emigrants can be influential in their home societies. Students from poor countries who have studied abroad in democracies and then return home bring with them pro-democracy attitudes. They spread these attitudes and are sufficiently influential that they speed up democratization. An astonishingly high proportion of the political leaders of poor countries have studied and worked abroad, and this equips them with both new skills and new attitudes. Even migrants who do not return have some influence with their relatives back home. During elections they give advice and commentary, and they become role models for smaller family size.

There has been a lot of research on whether emigration causes a brain drain or a âbrain gainâ. Intuitively, if educated people leave there can only be a brain drain. But we now know that this may be offset by an enhanced incentive to get education. If education is the prerequisite for getting to America, then the many youths who dream of going there will try harder at school. While some will achieve their dream, many will not but in the process will have acquired more education than otherwise. It turns out that which of these effects predominates depends upon how many educated people emigrate. In big countries that are already converging, such as China, relatively few educated people emigrate and so the brain gain predominates: China gains from emigration. But in small countries that are falling even further behind, such as Haiti, so many of the educated leave that the brain drain predominates. Many small, poor countries are unfortunately in the same position as Haiti.

The brain drain can potentially be reinforced by a motivation drain. Many poor societies are beset by opportunism: teachers donât show up for work, nurses steal drugs, policemen extract bribes. Those who are motivated to do their jobs properly can stick out as an uncomfortable minority. Emigrating to societies in which norms are more functional can be an attractive option for such workers, but cumulatively this is self-reinforcing: the more who leave the less attractive it is to stay. Whereas the brain drain is well-understood, the motivation drain has yet to be quantified but its analytic foundations have been set out by Nobel Laureate George Akerlof.

The brain drain can potentially be reinforced by a motivation drain. Many poor societies are beset by opportunism: teachers donât show up for work, nurses steal drugs, policemen extract bribes. Those who are motivated to do their jobs properly can stick out as an uncomfortable minority. Emigrating to societies in which norms are more functional can be an attractive option for such workers, but cumulatively this is self-reinforcing: the more who leave the less attractive it is to stay. Whereas the brain drain is well-understood, the motivation drain has yet to be quantified but its analytic foundations have been set out by Nobel Laureate George Akerlof.

Finally, emigrants send remittances home. While this is helpful for the relatives left behind, the average remittance is only around $1,000 per year. Workers would usually produce more than this if they were to stay home, so there is often a net loss to the economy.

In trying to weigh up these disparate effects it is clear that having some emigration is better for poor countries than having none. But this is a clear answer to the wrong question. The pertinent issue is whether poor countries would be better off with somewhat faster, or somewhat slower emigration than they have currently. The answer depends upon who is migrating: young people in search of an education, unskilled workers in search of a job, or skilled workers looking to use their talents. The evidence suggests that the more students the better, especially if they then return. Unskilled workers may well send back more in remittances than they would make at home. But the emigration of skilled workers may already be excessive. Recent evidence finds that for many of the poorest countries emigration rates are already beyond the point of peak benefit: these countries are haemorrhaging their scarce talents. The most severe effects are for fragile states emerging from conflict. During conflict they haemorrhage their most capable people. Post-conflict, they desperately need them to return but cannot compete with the lifestyles of the rich world. Emigrants considering return face a coordination problem: return would be less alarming were others to return as well but there is currently no mechanism for facilitating coordinated return.

Skilled and motivated people are the fairy godmothers in any society: they benefit ordinary people. As the fairy godmothers increasingly shift from poor societies to rich ones, they themselves benefit, but I question whether we should regard this as a triumph of social justice.

Paul Collierâs book Exodus was published by Oxford University Press and Penguin in September 2013.

March 17, 2014

Q: How many people is one rich man worth? A: 6.3 million. Extreme Inequality in the UK

Following his uber killer fact paper (assets of worldâs 85 richest individuals = 3.5 billion poorest) Ricardo Fuentes (@rivefuentes)  turns his jaundiced but numerate gaze to the UK (and triggers another media splash – see end for links)

turns his jaundiced but numerate gaze to the UK (and triggers another media splash – see end for links)

Economic inequality is much talked about these days. Two documents have made a splash over the last month: first, an IMF paper highlighting the potential dangers of inequality argued that redistribution does not harm economic growth. And last week, the much awaited English translation of Thomas Pikettyâs book Capital in the 21st Century was released, prompting several new reviews.

In January, Oxfam released the paper âWorking for the Fewâ, which got its share of attention. In it, we highlighted the vast global disparities in wealth and the worrying trends for some countries.

Now itâs the turn to look closely at Britainâs numbers. Here are the facts (from a new Oxfam briefing, A Tale of Two Britains):

The richest person in the UK (Gerald Cavendish Grosvenor, aka the 6th Duke of Westminster) is wealthier than the bottom 10 % of the population in the UK (thatâs 6.3 million people).

The richest 5 families in Britain are wealthier than the bottom 20 % of the population (12.6 million people).

In the last two decades (since 1993) the income of the bottom 90 % has increased by 27%, while the income of the richest 0.1 % has increased by 101%. In absolute terms the difference is much bigger â 1% of a shedload of cash is much more than 1% of a pittance. The bottom 90% has seen an increase in real income of about £150 per year . The top 0.1%, on the other hand, has seen its income rise by more than £24,000 a year, for two decades.

Since the fiscal year 2002/2003, real after-housing income for the poorest 95% of the population has actually gone down, while the after housing yearly income of the richest 5% has gone up.

The calculations are quite straightforward, using several sources, including the most recent billionaireâs list from Forbes, the Credit Suisse Databook, the World Top Incomes Database and the Family Resources Survey by the Department of Work and Pensions (also analyzed in detail by the Institute of Fiscal Studies in their âLiving Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK:2013â).

In âWorking for the Fewâ, we argued that this type of extreme inequality creates a vicious circle. Wealth that is concentrated in the hands of a few can then be used to buy political influence to rig the rules in favour of this small elite and perpetuate inequality. This process is not only worrying Oxfam. This weekâs Economist has a cover story on âThe New Age of Crony Capitalismâ. In the accompanying leader, the magazine argues that:

In âWorking for the Fewâ, we argued that this type of extreme inequality creates a vicious circle. Wealth that is concentrated in the hands of a few can then be used to buy political influence to rig the rules in favour of this small elite and perpetuate inequality. This process is not only worrying Oxfam. This weekâs Economist has a cover story on âThe New Age of Crony Capitalismâ. In the accompanying leader, the magazine argues that:

âCapitalism based on rent-seeking is not just unfair, but also bad for long-term growth. As our briefing on India explains (…), resources are misallocated: crummy roads are often the work of crony firms. Competition is repressed: Mexicans pay too much for their phones. Dynamic new firms are stifled by better-connected incumbents. And if linked to the financing of politics, rent-heavy capitalism sets a tone at the top that can let petty graft flourish.â

How does this relate to billionaireâs wealth? The Economist goes on to argue in the full article that âBillionaires in crony sectors have had a great century so far (…). In the emerging world their wealth doubled relative to the size of the economy, and is equivalent to over 4% of GDP, compared with 2% in 2000. Developing countries contribute 42% of world output, but 65% of crony wealth.â

Britain is not immune to this problem. In the Economistâs âCrony-Capitalism Indexâ, it ranks higher (meaning billionairesâ wealth from  crony-prone sectors) than the US, Japan, Germany, France and South Korea and has some pretty unsavoury neighbours in the table.

crony-prone sectors) than the US, Japan, Germany, France and South Korea and has some pretty unsavoury neighbours in the table.

All this is happening while the use of food banks is increasing across the country.

This is not about politics of envy. It is about ensuring that political representation and voice is not captured by a few. Some degree of inequality is required to reward those with talent, hard earned skills, and the ambition to innovate and take entrepreneurial risks. And plenty of wealthy people contribute to individual good causes. But the observed trends (in the level of wealth concentration and crony capitalism) point to a politically and economically dysfunctional level of inequality that everyone – from the IMF to the late Tony Benn – realize needs to be sorted out. As Paul Krugman wrote recently, while discussing the issue: people arenât envious, they are angry â and with good reason.

Lots of media coverage on this bit of number crunching, including the Daily Mail, the Mirror, Sky News , ITV, The Independent and Guardian (front page, below). Hope the ‘policy into practice‘ pundits are paying close attention.

March 14, 2014

RIP Tony Benn

A few examples of his legacy (please add your own): his famous five questions to the powerful (via the Political Gates blog) and a plaque he had installed in a cupboard in the House of Commons, but first an interview with Michael Moore (h/t Ben Phillips)

Research â Policy; understanding NGO failures and trying to be funny on inequality: conversations with students

Iâve been meeting some impressive students this week. Last night I was at a very swanky dinner organized  by the LSE Student Society  of its massive International Development department (rising to 300 uber-capable one year Masters students). Tricky gig – how do you make the topic (inequality) funny, as required by the after dinner speaker genre? Your responses to my tweeted appeal for jokes were no help â âdid you know that half the best jokes belong to just 1% of comediansâ was the best one. Crowdsourcing clearly has its limitations.

of its massive International Development department (rising to 300 uber-capable one year Masters students). Tricky gig – how do you make the topic (inequality) funny, as required by the after dinner speaker genre? Your responses to my tweeted appeal for jokes were no help â âdid you know that half the best jokes belong to just 1% of comediansâ was the best one. Crowdsourcing clearly has its limitations.

Earlier in the week, I headed down to IDS last week for a deeply enjoyable seminar with its Governance Masters students on a perennial topic – how research does/doesnât influence policy (powerpoint here IDS Research Into Policy March 2014, please steal). Key points:

Start with the right questions:

What are we trying to achieve?

Who are we trying to influence with evidence? Politicians, civil servants or other? They each need a different research approach.

Whatâs already known? What more is needed?

What kind of research will be most effective?

How should we engage our targets for best effect? (see recent post on what White House officials think about research)

NOT

Iâve done my research, now how do I get people to listen to my findings? (distressingly common, in practice).

Timing is crucial: if you want to influence policy, think about where your issue is located in the âpolicy funnelâ (see below, explanation here) and what that implies for the methodology, comms etc. Key times when policy is most likely to be influenced by research are when a ânew issueâ is still forming in the minds of policy makers, at the right point of the political timetable (eg election campaigns, manifestos) or after shocks (scandals, crises, new leaders). Rapid reaction is likely to deliver more results than a steady grind of research + seminar, but can be hard to finance (a âdrop everything, rehash old research and go into media overdriveâ funding pot?).

We then spent the second half sitting on the grass in the sun (in the open air? In March? In England?) having a great exchange on the aid business, NGOs etc. What struck me was the number of times I ended up talking about incentives, cultures and systems. Among other things, the students (a bright bunch with lots of first hand experience from the 12 countries represented â no Brits) raised the following questions:

We then spent the second half sitting on the grass in the sun (in the open air? In March? In England?) having a great exchange on the aid business, NGOs etc. What struck me was the number of times I ended up talking about incentives, cultures and systems. Among other things, the students (a bright bunch with lots of first hand experience from the 12 countries represented â no Brits) raised the following questions:

Why do NGOs sometimes find it hard to collaborate?

Why do NGOs dislike working with the private sector?

Why is it so hard to follow Engineers Without Borders and explicitly learn from failure?

Why are NGO campaigns and policy engagement often too short term, moving on before the job is done, and sometimes leaving partners and communities in the lurch?

In all of these, my response involved some version of:

Incentives: NGOs, like any other large institution, are not monoliths, but assemblies of different sub-parts, which may share overall purpose and values, but also have different short term incentives. So fund raisers and media people may be in competition with other NGOs, whereas campaigners and advocacy people have clear incentives to increase influence by forming coalitions.

Culture: People in NGOs are not poverty reducing automata. They come with baggage that can both inspire and hinder their work. Lots of lapsed Catholics in a programme make it very unlikely they will work with the Church, even when the situation seems to demand it (sexual and reproductive rights in the Philippines?). Campaigners seeking a new world order where profit is no longer king may have an instinctive antipathy to large corporations, driving fundraisers crazy.

Systems: Different systems work to distinctive rhythms: public protest and mobilization is always likely to be spikey, producing moments of uprising and protest, which then fade away, as the agglomerations of smaller, more long lasting organizations (trade unions, student unions, faith groups, producer organizations etc) dissipate.

So what? Well, rather than just labelling people (âotheringâ in IDS-speak) Â who disagree with you as right wingers, baddies, neoliberals, [insert perjorative term of choice], understanding why people think/act like they do is crucial to influencing them. Plus, you can save yourself a lot of self-criticism if you realize that things like protests waxing and waning is not down to being a good/bad campaigner, but is inherent in the nature of popular movements â then you can spend your time more productively getting ready to catch the next wave.

Secondly, if you want to change your organization, you need to understand it. Doing a power analysis, understanding peopleâs incentives, assembling coalitions for change, working out how to neutralize or win over the blockers. In short, you need to apply all the analysis and advocacy skills you would apply to influencing a company or government department. For some reason, people seem reluctant to do this â all too often, we think haranguing and finger wagging should suffice, because we havenât understood that not everyone in our organizations thinks/acts like us.

Research → Policy; understanding NGO failures and trying to be funny on inequality: conversations with students

I’ve been meeting some impressive students this week. Last night I was at a very swanky dinner organized by the LSE Student Society  of its massive International Development department (rising to 300 uber-capable one year Masters students). Tricky gig – how do you make the topic (inequality) funny, as required by the after dinner speaker genre? Your responses to my tweeted appeal for jokes were no help – ‘did you know that half the best jokes belong to just 1% of comedians’ was the best one. Crowdsourcing clearly has its limitations.

of its massive International Development department (rising to 300 uber-capable one year Masters students). Tricky gig – how do you make the topic (inequality) funny, as required by the after dinner speaker genre? Your responses to my tweeted appeal for jokes were no help – ‘did you know that half the best jokes belong to just 1% of comedians’ was the best one. Crowdsourcing clearly has its limitations.

Earlier in the week, I headed down to IDS last week for a deeply enjoyable seminar with its Governance Masters students on a perennial topic – how research does/doesn’t influence policy (powerpoint here IDS Research Into Policy March 2014, please steal). Key points:

Start with the right questions:

What are we trying to achieve?

Who are we trying to influence with evidence? Politicians, civil servants or other? They each need a different research approach.

What’s already known? What more is needed?

What kind of research will be most effective?

How should we engage our targets for best effect? (see recent post on what White House officials think about research)

NOT

I’ve done my research, now how do I get people to listen to my findings? (distressingly common, in practice).

Timing is crucial: if you want to influence policy, think about where your issue is located in the ‘policy funnel’ (see below, explanation here) and what that implies for the methodology, comms etc. Key times when policy is most likely to be influenced by research are when a ‘new issue’ is still forming in the minds of policy makers, at the right point of the political timetable (eg election campaigns, manifestos) or after shocks (scandals, crises, new leaders). Rapid reaction is likely to deliver more results than a steady grind of research + seminar, but can be hard to finance (a ‘drop everything, rehash old research and go into media overdrive’ funding pot?).

We then spent the second half sitting on the grass in the sun (in the open air? In March? In England?) having a great exchange on the aid business, NGOs etc. What struck me was the number of times I ended up talking about incentives, cultures and systems. Among other things, the students (a bright bunch with lots of first hand experience from the 12 countries represented – no Brits) raised the following questions:

We then spent the second half sitting on the grass in the sun (in the open air? In March? In England?) having a great exchange on the aid business, NGOs etc. What struck me was the number of times I ended up talking about incentives, cultures and systems. Among other things, the students (a bright bunch with lots of first hand experience from the 12 countries represented – no Brits) raised the following questions:

Why do NGOs sometimes find it hard to collaborate?

Why do NGOs dislike working with the private sector?

Why is it so hard to follow Engineers Without Borders and explicitly learn from failure?

Why are NGO campaigns and policy engagement often too short term, moving on before the job is done, and sometimes leaving partners and communities in the lurch?

In all of these, my response involved some version of:

Incentives: NGOs, like any other large institution, are not monoliths, but assemblies of different sub-parts, which may share overall purpose and values, but also have different short term incentives. So fund raisers and media people may be in competition with other NGOs, whereas campaigners and advocacy people have clear incentives to increase influence by forming coalitions.

Culture: People in NGOs are not poverty reducing automata. They come with baggage that can both inspire and hinder their work. Lots of lapsed Catholics in a programme make it very unlikely they will work with the Church, even when the situation seems to demand it (sexual and reproductive rights in the Philippines?). Campaigners seeking a new world order where profit is no longer king may have an instinctive antipathy to large corporations, driving fundraisers crazy.

Systems: Different systems work to distinctive rhythms: public protest and mobilization is always likely to be spikey, producing moments of uprising and protest, which then fade away, as the agglomerations of smaller, more long lasting organizations (trade unions, student unions, faith groups, producer organizations etc) dissipate.

So what? Well, rather than just labelling people (‘othering’ in IDS-speak) who disagree with you as right wingers, baddies, neoliberals, [insert perjorative term of choice], understanding why people think/act like they do is crucial to influencing them. Plus, you can save yourself a lot of self-criticism if you realize that things like protests waxing and waning is not down to being a good/bad campaigner, but is inherent in the nature of popular movements – then you can spend your time more productively getting ready to catch the next wave.

Secondly, if you want to change your organization, you need to understand it. Doing a power analysis, understanding people’s incentives, assembling coalitions for change, working out how to neutralize or win over the blockers. In short, you need to apply all the analysis and advocacy skills you would apply to influencing a company or government department. For some reason, people seem reluctant to do this – all too often, we think haranguing and finger wagging should suffice, because we haven’t understood that not everyone in our organizations thinks/acts like us.

March 13, 2014

Why scenario planning is a waste of time â focus on better understanding the past and present instead

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

TS Eliot, Burnt Norton

A few years ago, I used to rock up for the occasional UK government-convened scenario planning exercise (I know, exciting life or what?). They were usually run by ex Shell or BP âforesight peopleâ turned consultants and boy, were they disappointing. Asked to identify trends, participants regurgitated what they had read that week in The Economist or Financial Times. We then spent a few hours discussing and clustering them into possible futures, and inordinate time trying to come up with catchy names for the inevitable 2×2 (see below).

Why? Well partly, there is always huge attraction in thinking we are somehow able to predict the future (the source of the magnetic attraction over politicians by the more unscrupulous economists). Scenario types always stress that there workshops are not about prediction, just mental gymnastics to prepare us better for the future. But I haven’t seen much evidence of that.

I was reminded of this by a couple of conversations last week â a UNICEF foresights person dropped in to pick my brains, and I listened

Really, what is the point of this?

to a Shell scenario-ista do apparently random thought association at a conference (those guys havenât changed). Before we break out the flipcharts and weird hexagonal post-its (beloved of scenario planners) to grapple with time future, I think we need to get much better at time past and time present (using Elliotâs language â if you havenât read the Four Quartets, youâre in for a treat).

Time past: our ability to capture how change really happens is pretty patchy. All too often, we succumb to the temptation to airbrush out all the interesting stuff: the accidents, unexpected twists and turns, the failures and how we respond to them. The pressure to produce shiny, smooth, positive evaluations for funders or bosses undermines our ability to truly learn from the past. I often say that in Oxfam we have two kinds of âtime pastâ narrative. A dumbed down âthank you Oxfam for my goat, now my children are in schoolâ fund raiser and the 200 page largely unintelligible evaluation. What we miss is the middle ground – âstories for grown upsâ that welcome messiness, doubts over attribution etc, and capture the enthralling complexity of change.

Time present: but our work on time past sometimes looks stellar compared to time present. Working in complex systems where change is intrinsically unpredictable and non-linear means above all, having fast feedback loops so that you notice when the system is changing, and respond to it. This is really hard for large organizations that try to maintain coherence and direction through a hierarchy of plans (organizational, departmental, team and individual). If, after spending months agreeing these plans, something changes in the context that suggests a new direction, it is far easier to ignore it than rip up the plan and start all over again.

Even if individuals in their personal lives are aware of big changes in the context (as we call real life in the development business), they donât bring that into their work. While he was at ActionAid, my friend Matthew Lockwood used to say that all his interesting discussions about politics and context took place in evenings, usually in restaurants or bars, but never moved into the office. When food prices took off worldwide in 2008, Iâm sure Oxfam staff around the world were noticing the impact in their shopping baskets, but the first we research wonks in Oxford knew of this major disruption in the world food system was when journalists called us asking for a comment. The feedback loops just werenât in place.

The exception to this is humanitarian work, designed precisely to respond rapidly to shocks. When the Arab Spring took off in early 2011, for several months it was only our emergencies teams who discussed it as a potential refugee crisis. Only later did the penny drop with the rest of us that this was a massive advocacy opportunity, and we duly began putting Oxfamâs weight into advocacy partnerships at the Arab League and elsewhere.

The exception to this is humanitarian work, designed precisely to respond rapidly to shocks. When the Arab Spring took off in early 2011, for several months it was only our emergencies teams who discussed it as a potential refugee crisis. Only later did the penny drop with the rest of us that this was a massive advocacy opportunity, and we duly began putting Oxfamâs weight into advocacy partnerships at the Arab League and elsewhere.

Conclusion? If we want to pursue agility, flexibility and all those other words beloved of the managerial classes, the key is getting better at picking up the seismic tremors of social or economic change as early as possible, and learning to tell nuanced, intelligent, warts-and-all stories about change on the ground. Only then should we think about devoting a few hours on scenario planning. Otherwise, I wonât be bothering.

Why scenario planning is a waste of time – focus on better understanding the past and present instead

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

TS Eliot, Burnt Norton

A few years ago, I used to rock up for the occasional UK government-convened scenario planning exercise (I know, exciting life or what?). They were usually run by ex Shell or BP ‘foresight people’ turned consultants and boy, were they disappointing. Asked to identify trends, participants regurgitated what they had read that week in The Economist or Financial Times. We then spent a few hours discussing and clustering them into possible futures, and inordinate time trying to come up with catchy names for the inevitable 2×2 (see below).

Why? Well partly, there is always huge attraction in thinking we are somehow able to predict the future (the source of the magnetic attraction over politicians by the more unscrupulous economists). Scenario types always stress that there workshops are not about prediction, just mental gymnastics to prepare us better for the future. But I haven’t seen much evidence of that.

I was reminded of this by a couple of conversations last week – a UNICEF foresights person dropped in to pick my brains, and I listened

Really, what is the point of this?

to a Shell scenario-ista do apparently random thought association at a conference (those guys haven’t changed). Before we break out the flipcharts and weird hexagonal post-its (beloved of scenario planners) to grapple with time future, I think we need to get much better at time past and time present (using Elliot’s language – if you haven’t read the Four Quartets, you’re in for a treat).

Time past: our ability to capture how change really happens is pretty patchy. All too often, we succumb to the temptation to airbrush out all the interesting stuff: the accidents, unexpected twists and turns, the failures and how we respond to them. The pressure to produce shiny, smooth, positive evaluations for funders or bosses undermines our ability to truly learn from the past. I often say that in Oxfam we have two kinds of ‘time past’ narrative. A dumbed down ‘thank you Oxfam for my goat, now my children are in school’ fund raiser and the 200 page largely unintelligible evaluation. What we miss is the middle ground – ‘stories for grown ups’ that welcome messiness, doubts over attribution etc, and capture the enthralling complexity of change.

Time present: but our work on time past sometimes looks stellar compared to time present. Working in complex systems where change is intrinsically unpredictable and non-linear means above all, having fast feedback loops so that you notice when the system is changing, and respond to it. This is really hard for large organizations that try to maintain coherence and direction through a hierarchy of plans (organizational, departmental, team and individual). If, after spending months agreeing these plans, something changes in the context that suggests a new direction, it is far easier to ignore it than rip up the plan and start all over again.

Even if individuals in their personal lives are aware of big changes in the context (as we call real life in the development business), they don’t bring that into their work. While he was at ActionAid, my friend Matthew Lockwood used to say that all his interesting discussions about politics and context took place in evenings, usually in restaurants or bars, but never moved into the office. When food prices took off worldwide in 2008, I’m sure Oxfam staff around the world were noticing the impact in their shopping baskets, but the first we research wonks in Oxford knew of this major disruption in the world food system was when journalists called us asking for a comment. The feedback loops just weren’t in place.

The exception to this is humanitarian work, designed precisely to respond rapidly to shocks. When the Arab Spring took off in early 2011, for several months it was only our emergencies teams who discussed it as a potential refugee crisis. Only later did the penny drop with the rest of us that this was a massive advocacy opportunity, and we duly began putting Oxfam’s weight into advocacy partnerships at the Arab League and elsewhere.

The exception to this is humanitarian work, designed precisely to respond rapidly to shocks. When the Arab Spring took off in early 2011, for several months it was only our emergencies teams who discussed it as a potential refugee crisis. Only later did the penny drop with the rest of us that this was a massive advocacy opportunity, and we duly began putting Oxfam’s weight into advocacy partnerships at the Arab League and elsewhere.

Conclusion? If we want to pursue agility, flexibility and all those other words beloved of the managerial classes, the key is getting better at picking up the seismic tremors of social or economic change as early as possible, and learning to tell nuanced, intelligent, warts-and-all stories about change on the ground. Only then should we think about devoting a few hours on scenario planning. Otherwise, I won’t be bothering.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers