Duncan Green's Blog, page 195

March 3, 2014

The Great Escape, Angus Deaton’s big new book: Brilliant on inequality and politics, but wrong on aid

Ricardo Fuentes (@rivefuentes) reviews The Great Escape, Angus Deaton’s big (and controversial) new book on development.

A long time ago, while finishing my college degree at CIDE in Mexico, I started working with the different editions of the Mexican Household Income and Expenditure Survey. I was assisting my then boss and mentor, Alejandro Villagomez, in a project studying consumption and savings in poor households in Mexico. It was then that I first read Angus Deaton’s work – we used his synthetic cohorts method. It made me feel much smarter than I really was.

It was also around that time when Deaton published his hugely influential book: The Analysis of Households Surveys. For a young economist interested in development microeconomics, that book was nothing short of a miracle. Clearly written, broad in scope, technically thorough and with the Stata code for the analysis in the appendix. I used it so much in the early years of my career that the cover of my copy went from blue to pale gray. It’s now missing the back flap.

So it was very exciting to hear that Deaton had a new book. The Great Escape is a detailed tour-de-force that collects most of Deaton’s academic work over the last 20 years or so, but written for the general public. The first goal of the book is then to disseminate the trove of findings that Deaton and coauthors produced in academic journals. But the book is also an instrument for Deaton to express some of his views on politics and policy. This is what’s really new in The Great Escape.

In Deaton’s own words, the core argument of the book is:

“Life is better now than at almost any time in history. More people are richer and fewer people live in dire poverty. Lives are longer and parents no longer routinely watch a quarter of their children die. Yet millions still experience the horrors of destitution and of premature death. The world is hugely unequal.

Inequality is often a consequence of progress. Not everyone gets rich at the same time, and not everyone gets immediate access to the latest life-saving measures, whether access to clean water, to vaccines, or to new drugs for preventing heart disease. Inequalities in turn affect progress. This can be good; Indian children see what education can do and go to school too. It can be bad if the winners try to stop others from following them, pulling up the ladders behind them. The newly rich may use their wealth to influence politicians to restrict public education or health that they themselves do not need.”

So, humanity’s lot has improved over the long term but this progress creates inequalities in the process. The first two sections of the book present the evidence to support the argument. To explain how progress creates inequalities in health, for instance, Deaton uses the example of cigarette smoking. He writes “The knowledge that cigarette smoking kills has saved millions of lives in the past fifty years, yet it was educated, richer professionals who were the first to quit, opening up a health gap between rich and poor”. But then, he asks “Why do these inequalities persist, and what can be done about them?”

So, humanity’s lot has improved over the long term but this progress creates inequalities in the process. The first two sections of the book present the evidence to support the argument. To explain how progress creates inequalities in health, for instance, Deaton uses the example of cigarette smoking. He writes “The knowledge that cigarette smoking kills has saved millions of lives in the past fifty years, yet it was educated, richer professionals who were the first to quit, opening up a health gap between rich and poor”. But then, he asks “Why do these inequalities persist, and what can be done about them?”

This is, to me, the most important question in the book. While the existence of these inequalities is the result of scientific or technological progress, its persistence is the result of policy and political decisions.

Then it becomes a Catch-22. As Deaton argues, massive income inequality distorts the political process in favor of the few wealthy elites. “Growth, inequality, and catch up are the bright side of the coin. The dark side is what happens when the process is hijacked, so that catch-up never comes”. He explains how politics and inequality are intertwined in the US: “there is a danger that rapid growth of top incomes can become self-reinforcing through the political access that money can bring” and continues “If democracy becomes a plutocracy, those who are not rich are effectively disenfranchised.”

I agree with Deaton’s overall argument – it’s very similar to the idea behind our recent paper “Working For The Few”. Where I disagree, and it’s no surprise, is in Deaton’s last section, where he deals with the problems of international aid.

It is not that aid is without problems. Just by looking at the history of US food aid policy one could quickly become disenchanted. But it seems to me that Deaton is throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Deaton harshly criticizes the “hydraulic” approach to aid: if water is pumped in at one end, water pours out at the other. He writes “Fixing world poverty and saving the lives of dying children is seen as an engineering problem…. Children’s lives are saved by providing insecticide-treated bed nets (which protect against malaria) at a few dollars each, or by oral rehydration therapy at $0.25 a dose, or by administering vaccinations at a few dollars each”.

The thing is, children’s lives are indeed saved by bed nets, vaccinations and ORT, all of them supported by aid (as he later, in the same chapter, accepts). It’s hard to imagine the dramatic fall in child mortality in the last decade without such aid-supported interventions. Deaton spends the chapter focusing on the negative aspects of foreign aid (and there are plenty) but minimizes the positive impacts (and there are plenty of those too). His most drastic accusation, that foreign aid undermines democracy and civil participation in receiving countries, follows a similar logic as the resource curse. And just as with the resource curse, it might be true in some instances, but by no means justifies, as Deaton suggest, the elimination of all aid forms. That conclusion is akin to suggest no country should ever exploit its natural resources, instead of making better use of them. He writes that those in favor of foreign aid argue it needs to be improved, and goes on to dismiss it as an easy answer, but to me, it’s the most complicated, and relevant, one. The resources available through foreign aid can and should be used to promote that Great Escape that Deaton celebrates.

Deaton concludes with cautious optimism about the future of humanity’s lot in the face of major threats, most notably climate change and politics captured by a small elite. It’s reassuring to read this hopeful note from someone of Deaton’s stature. And many years after first reading his writings, I’m still learning in every document he writes. Highly recommended.

Loads of other reviews in the blogosphere, but I particularly enjoyed Owen Barder’s polite but forensic probing in his Development Drums podcast interview with Deaton.

March 2, 2014

What’s missing from the ‘Active Citizens + Effective States’ formula in From Poverty to Power?

Oh dear. Be careful what you wish for. When I wrote From Poverty to Power (the book, not the blog), we came up with a nice subtitle  that seemed to capture a common thread linking the very diverse topics covered in the book – ‘How Active Citizens and Effective States can Change the World.’ But now I’m starting to regret it.

that seemed to capture a common thread linking the very diverse topics covered in the book – ‘How Active Citizens and Effective States can Change the World.’ But now I’m starting to regret it.

At the time (the book was published in 2008), I was concerned with getting INGOs to engage more fully with states, whether at national or local level. INGOs should not just be about building civil society organizations, but also helping them engage with those in power. We certainly do more of that now, (I’m making no claim to attribution here – the book mainly just systematized what was emerging in Oxfam’s collective brain). In particular, INGOs increasingly find themselves in a ‘convening and brokering’ role, operating in the interstices between citizens’ movements and states.

But as I do my rounds and talk to staff and partners, I am increasingly kicking back against a new intellectual trap – we are in danger of constructing a binary world in which citizens (‘rights holders’) simply demand a string of actions from states (‘duty bearers’). I have at least three serious objections to this approach:

The first is that the world of politics and power is not binary. As I found in Tajikistan, NGO staff may have a default position of just seeing states and ‘people like us’ in organized civil society groups, but ask them to scratch the surface of any village, city etc and they rapidly identify a far richer ecosystem of institutions and social capital– faith organizations, savings groups, funeral societies, sports associations, respected figures (teachers, nurses, doctors). It is coalitions of such groups and individuals that drive/block change, not an over-simplified and somewhat barren bi-culture of state and civil society.

The second is that civil society itself is not monolithic. Instead, it is granular, made up of any number of more durable institutions, whether formal or (more often) informal. NGOs need to immerse themselves deeply in these ecosystems to understand their work with civil society.

The second is that civil society itself is not monolithic. Instead, it is granular, made up of any number of more durable institutions, whether formal or (more often) informal. NGOs need to immerse themselves deeply in these ecosystems to understand their work with civil society.

The third is that in practice simply siding with rights holders to put pressure on duty bearers seldom works. In country after country, the latter, for example village officials, sidle up to us and say sotto voce ‘we really want to do our job better, but we have no idea how – can you help please?’ So we end up arranging training for the representatives of the state, not just supporting the demands of its citizens. And frequently, we go further and bring the two together to find solutions together, PDIA style.

There’s at least one other major weakness in the ‘Active Citizens-Effective States’ formula – economic power is absent. At the time I wrote the book, lots of people wanted me to include ‘cuddly private sector’ (or something like that) as a third part of the equation, and I resisted arguing (rightly, I still think) that states and citizens act together to set the rules within which the private sector emerges, operates and evolves. What I missed (especially as I read up on the literature for a subsequent PhD) was the broader issue of economic power and the way it shapes and misshapes politics, as discussed in our recent paper on inequality. That should have been more prominent.

Don’t get me wrong, I still think the ‘active citizens and effective states’ formula is a useful aide memoire. But as I lurch towards my next book (working title ‘How Change Happens’) expect things to get more complicated.

February 27, 2014

What do White House Policy Makers want from Researchers? Important survey findings.

Interesting survey of US policymakers in December’s International Studies Quarterly journal. I’m not linking to it because it’s gated, thereby excluding more or less everyone outside a traditional academic institution (open data anyone?) but here’s a draft of What Do Policymakers Want From Us?, by Paul Avey and Michael Desch. The results are as relevant to NGO advocacy people trying to influence governments as they are to scholars. Maybe more so. I’ve added my own running translation in italics.

The authors surveyed all senior White House officials involved in national security under both George Bushes and Bill Clinton. 234 out of 915 responded (pretty good response rate for people this senior).

Conclusions?

‘The gap between the scientific aspirations of contemporary international relations scholarship and the needs of policymakers is  greatest the higher one reaches in the policy world. More surprisingly, this gap tends to be greater the more educated the policymaker. This is consistent with the argument that familiarity with advanced techniques instills greater appreciation for both their promise and limits.

greatest the higher one reaches in the policy world. More surprisingly, this gap tends to be greater the more educated the policymaker. This is consistent with the argument that familiarity with advanced techniques instills greater appreciation for both their promise and limits.

Translation: the more pols know about a subject, the less they believe ‘experts’

Another conclusion we draw from this survey is that a scholar’s broader visibility – both in government and among the public whether through previous government service or publication in broader venues –– enhances influence among policymakers more than his or her academic standing.

Translation: get blogging, people

The primary constraint policymakers face in digesting scholarly, or any other writings, is lack of time. As one respondent put it, “any research papers that exceed 10-15 pages” are not useful to policymakers. Another noted that “I do not have the time to read much so cannot cite” many examples of useful social science scholarship.

Translation: work on those elevator pitches

We were surprised by two other findings from our survey about how policymakers get their information: First, unclassified newspaper articles were as important to policymakers as the classified information generated inside the government. This fact opens up an important avenue for scholarly influence upon policy if scholars can condense and convey their findings via this route.

Second, the Internet has not yet become an important source of information for policymakers, despite its ease of accessibility and the generally succinct nature of the presentation of its content. It could be a just a matter of time until a more web-oriented generation reaches the pinnacle of national security decision-making authority but we also ought to consider whether the internet suffers from weaknesses vis-à-vis traditional print media that dilute its influence. The plethora of internet news and opinion outlets, many of questionable reliability, combined with the lack of an authoritative source among them, may mean that the internet will continue to lag behind the elite print media because it exacerbates the signals to noise problem for policymakers.

Translation: good old fashioned press work beats social media

But our most important findings concern what role policymakers think scholars ought to play in the policy process. Most recommended that scholars serve as “informal advisers” and as “creators of new knowledge.” There were two surprises for us here: First, policymakers ranked the educational and training role of scholars for future policymakers third behind these other two roles. They also confessed that they derived relatively little of their professional skills from their formal educations. (see pie chart) The main contribution of scholars, in their view, was research. Second, and again somewhat surprisingly, they expressed a preference for

Obviously not a policy maker

scholars to produce “arguments” (what we would call theories) over the generation of specific “evidence” (what we think of as facts). In other words, despite their jaundiced view of cutting-edge tools and rarefied theory, the thing policymakers most want from scholars are frameworks for making sense of the world they have to operate in.’

Translation: the best narrative (not the best evidence) wins

And the recommendations:

‘The most important roles for scholars to play are as both teachers and researchers, but our results suggest that both areas need careful rethinking. On the former, the findings of our survey should lead to some introspection about how we train students for careers in government service. We suspect that the focus on social science techniques and methods that dominates so much graduate, and increasingly undergraduate, training in political science is not useful across the board to policymakers. On the other hand, a purely descriptive, fact-based approach is not what policymakers seem to want from scholars either.

Three aspects of scholarship appear to be most important: First, policymakers appear to want mid-range theory. Policymakers do not reject methodologically sophisticated scholarship across the board but do seem to find much of it not useful. They prefer that scholars generate simple and straightforward frameworks that help them make sense of a complex world. They seem not so much to be looking for direct policy advice as for background knowledge to help them put particular events within a more general context. We interpret policymakers’ preference for theories over facts to the fact that like most busy people, they are cognitive economizers who need ways to make good decisions quickly and under great uncertainty. Along these lines, Henry Kissinger reportedly demanded of his subordinates: “Don’t tell me facts, tell me what they mean.”

Second, brevity is key for policymakers. We suspect that the reason that Op/Eds are so influential among policymakers is only partly due to where they are published; another important aspect of their influence is their short length. We are by no means suggesting that scholars only write in that format, but we strongly believe that research findings that cannot be presented in that format are unlikely to shape policy. Therefore, our recommended model is one in which a scholar publishes his or her findings in traditional scholar outlets such as books or journals but also writes shorter and more accessible pieces reporting the same findings and telegraphing their policy implications in policy journals, opinion pieces, or even on blogs.

Finally, a related issue is accessibility: Policymakers find much current scholarly work – from across the methodological spectrum – inaccessible. Policymakers don’t want scholars to write in Greek or French, but rather just plain English.’

Translation: tell better, clearer, shorter stories and you may actually be listened to

February 26, 2014

How is India’s iconic NREGA social protection scheme doing? Interesting research from Tamil Nadu.

Some social programmes act as honey pots for busy bee researchers. A few years ago Brazil’s Bolsa Familia was the subject of choice,  but it seems to have been overtaken by India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) which has researchers all over it.

but it seems to have been overtaken by India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) which has researchers all over it.

A from the University of Sussex has some great insights into the programme, based on a case study in Tamil Nadu involving in depth research in two villages, interviews with 109 MGNREGA workers, site organizers, village administrators and higher level officials.

First an intro to the programme:

‘In 2012-13 alone MNREGA benefitted nearly 50 million rural households across the subcontinent. MGNREGA was enacted by Parliament in 2005 and rolled out across all districts in 2008. It seeks to provide basic social security to India’s rural poor providing 100 days of guaranteed waged employment to every rural household. At the time of this research project, in late 2011, this was at an official daily wage rate of INR 119 (US$2) set by the Government of Tamil Nadu.

In Tamil Nadu, widely considered to be a ‘success’ story in terms of MGNREGA implementation, official data suggests that annual expenditure on the scheme stands at INR 41 billion (US$680 million) in 2012- 13. The average number of person days used per rural household has increased steadily, as has the total number of person days. Between 2008-9 and 2012-13, the total number of households who benefited from the scheme more than doubled from 3.3 million to 7 million.’

On to the survey:

‘In these two villages, in line with state-level data, the majority of MGNREGA workers are women (88 per cent) and Dalits (76 per cent). Compared to the village population as a whole, MGNREGA workers are less well educated (56 per cent having no education at all compared to 37.5 per cent of the village as a whole) and a higher proportion of them are divorced, separated or widowed (25 per cent, compared to around 10 per cent for the whole village population).

MGNREGA workers are drawn particularly from those households who depend on agricultural labour as their main source of income, rather than from households drawing their primary income from better paid, non-agricultural activities such as Tiruppur garment jobs or village based powerloom work.

When they are not working for MGNREGA, most workers (73 per cent) are employed as daily agricultural labourers, while a significant minority (15 per cent) has no other work at all: these are the old, weak, disabled or those with young children.

When they are not working for MGNREGA, most workers (73 per cent) are employed as daily agricultural labourers, while a significant minority (15 per cent) has no other work at all: these are the old, weak, disabled or those with young children.

The main beneficiaries of the scheme are thus women, Dalits and villagers with little education or assets, and it is clear that in terms of reaching vulnerable rural groups, the scheme is remarkably successful in this region.

Key findings:

• In Tamil Nadu MGNREGA has benefitted the poorest of the poor, especially by providing a safety net and a tool for poverty alleviation. It has particularly benefitted rural women and others who depend on low paid agricultural work.

• The gendered impacts of MGNREGA are largely due to the universal, right-based and women-friendly nature of the policy, which has made it accessible and suitable for women and other vulnerable social groups.

• Working for MGNREGA suits the rural poor at different times of the year and for several reasons. In the study region the ‘pros’ of MGNREGA included its local availability throughout the year, relatively ‘easy’ work with fixed and regularly paid wages, equal pay for men and women, and the opportunity to work free from caste-based relations of subordination and discrimination.

• The scheme has produced transformative outcomes for the rural poor. It has a significant indirect effect on agricultural wages, creating a positive impact that reaches far beyond those it employs. It also improves the bargaining power of agricultural workers, most of whom are women.

• In terms of public works, the scheme has failed to create sustainable assets or to contribute to the development of the rural economy.

• Key to successful implementation is the nature of the bureaucratic and institutional organisation at the level of the state and below. In Tamil Nadu MGNREGA implementation has benefitted from cross-party support from the state government and a well-functioning state bureaucracy.

• Official MGNREGA data should be used with caution. Assessing the validity of this data by comparing it to field level observations, researchers found that in some ways the official MGNREGA data is reasonably robust, while in other – very important – ways it is highly problematic. This raises an important ‘flag of warning’ to others drawing on particular parts of the official MGNREGA dataset.’

Over to all the other MGNREGistas for their comments and links.

February 25, 2014

What Makes Big Corporations Decide to Get on the Right Side of History?

For the past year, Oxfam’s

Erinch Sahan

(right) has been working on the ‘

Behind the Brands

’ campaign. Here he reflects on some successes and lessons from his time in the advocacy trenches.

some successes and lessons from his time in the advocacy trenches.

On 19 May 1997, the CEO of BP, John Browne, made a speech at Stanford University. Browne: “We must now focus on what can and what should be done, not because we can be certain climate change is happening, but because the possibility can’t be ignored.” This was a game changer. Browne made BP the first multinational (other than re-insurance companies) to join the emerging consensus on climate change. He also committed BP to taking action on reducing its emissions.

Regardless of what you now think about BP’s rhetoric or practices, Browne changed the way companies talk about climate change. It’s now hard to find a mainstream company that doesn’t accept climate change is happening and is linked to our (human) activities. Yet why did Browne break ranks?

The answer, I believe, is that he saw it as inevitable. The science was becoming clearer, the public was becoming engaged and politicians were beginning to scramble about for a solution that showed they had a vision. The business world was entrenched in a position that was on the wrong side of history and Browne didn’t want to be dragged kicking and screaming to the right side. If you know you’ll be moved back to the cheap seats at a stadium, why not move before the security guards drag you over?

Of course the rationale for why Browne flipped sides is more complicated than this. Maybe he saw money in solar energy, or wanted to shape the regulatory landscape around climate or had an altruistic voice that drove his decision. These probably played a role. But he also saw that climate action was becoming the new black in global politics and wanted to have the latest fashion before his friends and rivals.

Of course the rationale for why Browne flipped sides is more complicated than this. Maybe he saw money in solar energy, or wanted to shape the regulatory landscape around climate or had an altruistic voice that drove his decision. These probably played a role. But he also saw that climate action was becoming the new black in global politics and wanted to have the latest fashion before his friends and rivals.

The tide can turn quickly on global issues. One day, people defend child labour as being a route out of poverty, the next, it becomes unthinkable. It’s partly our role as activists and advocates to help along the debate so it reaches that tipping point sooner. That means persuading companies that the tipping point is coming. We think this is happening on living wage, as companies watch each other to see who moves first. Here’s how we did it through Behind the Brands.

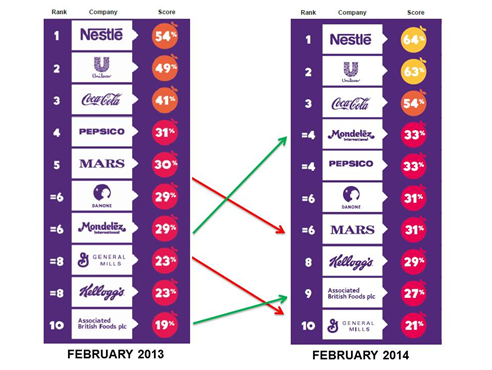

We kicked off the campaign a year ago to change how the food and drinks industry buys its ingredients. This time last year, the industry was failing on a number of key issues, we chose two in particular: how it addresses women’s inequality and land rights. Scores (we have a scorecard quantifying their performance) were woeful and none of the Big 10 had an approach that addressed the plight of women working on farms around the world and none were making suppliers respect the rights of communities over land. In fact, they weren’t even paying lip-service to the importance of land rights.

We spent the last year reminding companies about these blind-spots, asking supporters (nearly 400,000 of them), investors representing billions of dollars and civil society to join us in urging the Big 10 to start addressing gender and land issues.

On land, led by Coca Cola, six of the Big 10 now endorse the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent on land acquisition. This is key in ensuring that communities have a say over what happens to the land they depend upon. Seven of the Big 10 have signed on to the UN Women’s Empowerment Principles, which demonstrates a commitment to ensuring that the industry starts addressing the barriers faced by women on farms and markets around the world.

Over the last year, what I’ve learned is this: build the case for why this is inevitable – make corporates worry that they’re on the wrong side of history. We alone don’t have the gravitas to do this. But companies targeted by Behind the Brands heard from pension fund managers and industry peers (such as retailers), they were asked why they didn’t have a process for understanding where land disputes might be popping up. They heard from shareholders at their AGMs and their brand managers saw that hundreds of thousands of their consumers were interested enough to contact them on social media to drive home the point. It’s the surprising number of angles that they heard from that generated the questions: “Are we missing something here? Has land rights become a mainstream issue?”.

Today we release our annual update of the BtB scorecard, which underpins the campaign. The results are encouraging.

Nearly all the companies are on the right track. All but General Mills have improved their overall scores since February 2013. The top three (Nestle, Unilever and Coca-Cola) separated themselves further from the pack and saw the biggest jump in scores with overall increases of 10 percent, 14 percent and 13 percent. The companies in the middle of the pack (Danone, Mars, Mondelez and PepsiCo) saw mild improvements. There were some improvements also at the bottom of the scorecard. Associated British Foods and Kellogg’s – previously ranked 10th and 8th respectively – saw increases in scores of 7 and 6 percent respectively. As a result, General Mills is now at the bottom of the rankings.

Nearly all the companies are on the right track. All but General Mills have improved their overall scores since February 2013. The top three (Nestle, Unilever and Coca-Cola) separated themselves further from the pack and saw the biggest jump in scores with overall increases of 10 percent, 14 percent and 13 percent. The companies in the middle of the pack (Danone, Mars, Mondelez and PepsiCo) saw mild improvements. There were some improvements also at the bottom of the scorecard. Associated British Foods and Kellogg’s – previously ranked 10th and 8th respectively – saw increases in scores of 7 and 6 percent respectively. As a result, General Mills is now at the bottom of the rankings.

So if you want to shift corporate behaviour, build a surprising coalition (investors, activists, industry experts) and be persistent (“they will never want you to know you’re impacting them, but trust me, they’re listening” one senior manager in the sector told me).

With business practices so important to the life of every person on the planet and so key in driving the global agenda, we need to get even sharper at making change happen in big business.

February 24, 2014

How to fix fragile states? The OECD reckons it’s all down to tax systems.

‘Over-generous tax exemptions awarded to multinational enterprises often deprive fragile states of potential revenues that could be used to fund their most pressing needs.’ Another broadside from rent-a-mob? Nope, it’s the ultra respectable OECD in its Fragile States 2014 report.

After years of growth, aid to fragile states started to fall in 2011, so the report centres around an urgent call for OECD member states to help their more fragile cousins find a post-aid arrangement that funds essential state functions and builds the ‘social contract’ with citizens.

help their more fragile cousins find a post-aid arrangement that funds essential state functions and builds the ‘social contract’ with citizens.

The key is a shift from aid dependence to ‘domestic resource mobilization’ (taxes and natural resource royalties), currently averaging a feeble 14% of GDP across fragile states and far too dependent on royalties from oil, gas and mineral extraction (see chart, below). Foreign direct investment (factories, farms etc) is generally low in volume and volatile. (see graph, right – CPA means ‘aid’)

The OECD advocates a nicely balanced three-pronged approach:

‘Encourage a broader tax base by focussing on approaches that give citizens a voice.’ (the ‘no taxation without representation’ path to the social contract).

‘Support fragile states in designing frameworks to ensure fairer deals with multinational enterprises, in particular on proceeds from their natural resources; providers of development co-operation can lead by example by being transparent about the tax exemptions that benefit them.’ The report goes further, calling on OECD countries to ‘take steps to comply with global standards on money laundering, tax evasion and bribery.’

‘Boost citizens’ tax morale by establishing clear links between tax revenue and local benefits.’

Currently a truly laughable 0.07% of aid to fragile states goes to strengthening their tax systems. So the OECD wants the diminishing pool of aid to redress ‘weak technical and institutional capacity’ in fragile states, helping them introduce and collect direct taxes.

A guiding principle in all this will be ‘leadership and political will for reform by the host country – aid alone cannot ‘buy’ effective and lasting reforms’. Ah. Houston, I think we got a problem. The defining feature of fragile states is not that they are poor, but that they are, erm, fragile. Institutions are weak and/or subject to capture. This is the Achilles’ heel for any number of well-intentioned aid efforts, which ‘assume a can opener’ in the form of an effective state, when its absence is precisely the problem it is trying to address.

It’s not insoluble – fragile states are ramshackle coalitions of ministries, interest groups, factions etc, as well as lots of non-state groups, some of which can form part of a pro-DRM coalition willing to confront the blockers who benefit from the status quo. Shocks, scandals and financial meltdowns offer windows of opportunity, in which resistance to change may melt away. But how such change might happen needs to be thought through just as much as the what of standard reform shopping lists.

It’s not insoluble – fragile states are ramshackle coalitions of ministries, interest groups, factions etc, as well as lots of non-state groups, some of which can form part of a pro-DRM coalition willing to confront the blockers who benefit from the status quo. Shocks, scandals and financial meltdowns offer windows of opportunity, in which resistance to change may melt away. But how such change might happen needs to be thought through just as much as the what of standard reform shopping lists.

I suspect the OECD knows this full well, but can’t include it in supposedly ‘neutral’ policy papers. In any case, it’s great that they are addressing these crucial topics. Bring on the DRM.

The report’s other oversight is remittances, which dwarf other sources of capital (see graph again), but are dismissed rather too easily in the report as only relevant to middle income fragile states (yes, they do exist). If Tajikistan is anything to go by, remittances matter a lot for the poor ones too, and are an obvious point of contact with OECD states and their migration policies. But maybe that was a political hot potato too……

February 23, 2014

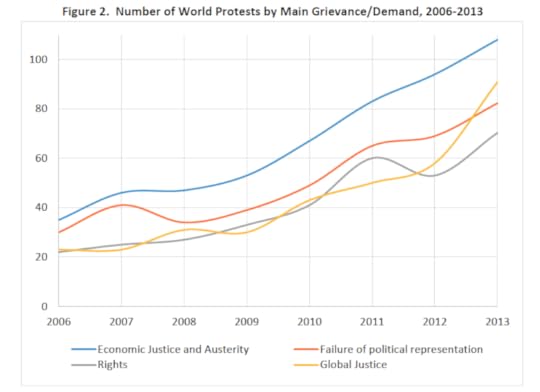

World Protests 2006-13: Where? How big? About what? Did they achieve anything?

Following on from last week’s food riots post, some wider context. The news is full of protests (Kiev, Caracas, Cairo), but to what extent is it really ‘all kicking off everywhere’ as Paul Mason claims? Just come across a pretty crude, but thought-provoking paper that tries to find out. For World Protests 2006-13, Isabel Ortiz, Sara Burke, Mohamed Berrada and Hernan Cortes scoured online media (international and national) to identify and analyse 843 protests over the period. Among their findings are:

Protests have steadily increased in number, particularly after 2010 (see graph).

Protests were more prevalent in high income countries, but violent riots were mainly a low income country phenomenon (feel free to debate the arrow of causality on that one).

The main grievances and causes of outrage were:

Economic Justice and Anti-Austerity: 488 protests (public services, tax, austerity, jobs, wages, inequality, poverty, land reform, energy and food prices, pensions, housing)

Failure of Political Representation and Political Systems: 376 protests (democracy, corporate influence, deregulation, privatization, corruption, access to justice, accountability, surveillance, anti-war)

Global Justice: 311 protests (international institutions, environment, trade, G20)

Rights of People: 302 protests (ethnic/indigenous rights, right to land, culture; labour righrts; women’s rights; freedom of assembly/speech/press/worship; sexuality; immigrant rights)

Demonstrators mostly address their grievances to national governments (see table, below)- also a finding of the food riots research I reviewed last week.

Not only is the number of protests increasing, but also the number of protestors. Crowd estimates suggest that 37 events had one million or more protesters; some of those may well be the largest protests in history (eg. 100 million in India in 2013, 17 million in Egypt in 2013).

‘As of 2013, as many as 63% of the protests covered in the study achieved neither their intended demands nor their expressed grievances in the short-term’. Not sure what to make of this – is a 37% success rate good or bad compared to other forms of political engagement?

‘Repression is well documented in over half of the protest episodes analyzed in the study.’ Yeah, but that may be partly because nothing guarantees you news coverage better than repression.

Which points to some wider flaws with the study – although it does discuss numbers involved, it doesn’t weight the protests accordingly in its wider analysis, which means that media visibility trumps size. It’s reasonable to assume that a few hundred demonstrators outside an IMF meeting are going to register for this study, when a few hundred peasants in rural Malawi or China are not, so the findings are likely to be heavily skewed towards global, metropolitian protests.

Even so, an interesting exercise.

February 20, 2014

How should INGOs prepare for the coming disruption? Reading the aid/development horizon scans (so that you don’t have to)

Gosh, INGOs do find themselves fascinating. Into my inbox plop regular exercises in deep navel-gazing –both excessively self- regarding and probably necessary. They follow a pretty standard formula:

regarding and probably necessary. They follow a pretty standard formula:

Everything is changing. Mobile phones! Rise of China!

Everything is speeding up. Instant feedback! Fickle consumers! Shrinking product cycles!

You, in contrast are excruciatingly slow, bureaucratic and out of touch. I spit on you and your logframes.

Transform or die!

OK, I’ve embroidered a little. The even-more-awful truth is that the prose in these reports is some of the worst I come across in the aid biz, and that’s a pretty high bar. Try this: ‘This report explores whether INGOs can leverage their distinct assets to proactively create greater impact to benefit the people they serve.’ I tell you, I’m taking one for the team by reading these.

Deep breath. On with the summary:

Ahead of the Curve: Insights for the International NGO of the Future, (written by the Foundation Strategy Group, funded by the Hewlett Foundation) surveys 50 big US NGOs receiving large chunks of the US government’s $4bn annual spending via NGOs (so not Oxfam America, which keeps its distance on this). Overall, the authors are unimpressed:

‘Most INGOs are neither proactively assessing these disruptions nor fundamentally changing in response. Rigorous, long-term, multisector collaborations needed to address complex challenges are rare. INGOs continue to look at the private sector as a source of philanthropic funding, rather than as a mutual partner for scaled impact. INGOs with a higher dependence on U.S. government funding have little time, resources, or incentives to think beyond the next grant or cooperative agreement.’

The paper sees four options (sorry, I mean ‘future-oriented approaches’) for INGOs (see graphic): ‘(1) enhancing direct implementation; (2) influencing systems change; (3) harnessing the private sector; and (4) leading multisector action.’ And has some sensible recommendations for our beloved leaders:

The paper sees four options (sorry, I mean ‘future-oriented approaches’) for INGOs (see graphic): ‘(1) enhancing direct implementation; (2) influencing systems change; (3) harnessing the private sector; and (4) leading multisector action.’ And has some sensible recommendations for our beloved leaders:

To influence systems, INGOs can develop the capacity of country staff to identify systemic solutions and synthesize learning to establish thought leadership positions on complex challenges.

To harness the private sector, INGOs can develop criteria to guide partnerships, create new messaging for corporate partners, and demonstrate the benefit of shared value to donors.

To lead multisector action, INGOs can build up the capacity to assist low- and middle-income country governments to coordinate collaborations, explore shared measurement systems, and make the case to donors about the value of collective impact.

Riding the Wave (rather than being swept away) comes from the International Civil Society Centre, with dosh from the Rockefeller Foundation and Robert Bosch Stiftung. Its focus is on what it sees as the multiple ‘disruptions’ currently threatening business as usual. At a global level, these include the breaching of planetary boundaries, but at a more prosaic level of INGO business models, they include ‘disintermediation’ (will organizations like GiveDirectly that transfer cash straight to the SIM cards of the poor make intermediary NGOs – i.e. the rest of us – redundant?) and closing civil society space in many countries (where did all our partners go?).

The answer (wait for it) is ‘building a disruption resilient organization’. What does that mean? You may well ask; luckily there are some  answers:

answers:

‘We identified three different strategies for how to position ICSOs towards disruption: the “active disruptor” actively advances potential disruption rather than trying to avoid or mitigate its effects. An ICSO that merges with a “virtual CSO” (a civil society organisation that supports projects or runs campaigns predominantly through the internet) or forms its own virtual entity might be an example of this strategy.

The “opportunistic navigator” carefully screens changes in its environment and prepares itself to quickly embark on a deep-rooted process of change should that become necessary. An example of such might be an ICSO that cooperates or partners with virtual CSOs, social entrepreneurs and other new and potentially disruptive entities in order to strengthen its awareness of change and to be prepared in case disruption occurs.

The “conservative survivor” builds on its reputation, size and bank account. This strategy tries to navigate around disruption as much as possible and is the riskiest approach once disruption becomes unavoidable. An ICSO that monitors developments and growth rates in the virtual CSO sector and reviews its own income in comparison, but otherwise takes a “wait and see” approach, could illustrate this tactic. To date, most ICSOs tend to lean towards this strategy.’

Finally, a rather breathless paper from IDS, Re-imagining Development 3.0 for a Changing Planet by Jon Morris. This is a pure distillation of a slightly different genre: a high speed canter through an apparently random series of recent trends (urbanization, capital market liberalization, identity politics, wars involving non-state actors), leading to an apparently unconnected, and largely politics-free ‘If I Ruled the World’ shopping list including gems like ‘fair trade to replace free trade’ and (fanfare please) ‘working with all people in all nations.’ Good luck with that guys.

There, I’ve given some of you back hours of your lives, but at what personal cost? Heading for a darkened room and some therapeutic screaming.

On holiday next week (probably just as well, judging by the snark-ometer reading on this post), but there is no escape for the rest of you – I’ve scheduled posts throughout.

Update: Ken Caldwell sends in a comment to say that there is an entire website devoted to this kind of thing. Check out the Baobab site

February 19, 2014

What do we know about food riots and their link to food rights? Some interesting new findings from IDS

Went off to a rain-drenched Institute of Development Studies last week for one of those great workshops where a group of country researchers come together with case studies on a similar issue and then swap ideas on what general conclusions are emerging. The topic was the rash of food riots that struck 30+ countries in the aftermath of the 2008 food price spike, marking the onset of a new

period of volatilility with big social and economic impacts (see, for example, the Oxfam/IDS project on life in a time of food price volatility, which has its second annual report coming out soon).

The starting point for the work, which is being led by Naomi Hossain, is bringing together an IDS-style ‘voices of the rioters’ approach, using focus groups and interviews, with a more theoretical ‘moral economy’ lens, drawing on the work of EP Thompson on food riots in 18thC England (right). As Naomi and Ferdous Jahan explain in their Bangladesh study:

‘People do not protest because they are hungry, but on the basis of powerful ideological justifications that arise from ideas about how food markets should work, the limits set by public opinion on the freedoms of (food) markets in times of scarcity or crises, and the idea that public authorities are responsible to act to protect people’s rights to food at such times. These are summarised as ‘moral economy’ ideas, and may be latently present under normal conditions. But it is mainly when shocks occur in the national or local food economy that they tend to be activated and articulated and to legitimate popular mobilisation.’

Case studies on Bangladesh, India, Kenya and Mozambique threw up some important stuff. I’ll link to the papers when they are finalised and published, but here are some initial impressions.

The importance of history and memory: one legacy of horrific 20thC famines in Bangladesh and India is that both the public and policy makers are highly sensitive to the issue of food security. In Kenya, the memory of post election violence in 2008 meant that protesters were much less likely to resort to violence this time around.

The blame game is complicated: rioters tend to blame private sector baddies (hoarders and speculators), and corrupt government officials, but demand solutions from those same governments, often contrasting today’s situation with an imaginary golden age of state responsiveness. The retreat of the state and rise of market mechanisms has had a multiple impact here – privatization, often to the hands of well connected insiders, seems to have replaced old forms of patronage (‘inclusive clientilism’?) with a more elitist version. Fewer people have their snouts in the trough these days. State retreat also weakens its ability to respond to protest.

The blame game is complicated: rioters tend to blame private sector baddies (hoarders and speculators), and corrupt government officials, but demand solutions from those same governments, often contrasting today’s situation with an imaginary golden age of state responsiveness. The retreat of the state and rise of market mechanisms has had a multiple impact here – privatization, often to the hands of well connected insiders, seems to have replaced old forms of patronage (‘inclusive clientilism’?) with a more elitist version. Fewer people have their snouts in the trough these days. State retreat also weakens its ability to respond to protest.

The interplay between institutions, ‘politics as usual’ and violent protest. Where there are channels that poor people see as at least partly genuine, protests will often go that route, rather than the much riskier path of chucking Molotov cocktails. In India, protesters in Madhya Pradesh, with its vibrant Right to Food movement, were much less likely to go on the rampage than those in West Bengal, where such a movement is largely absent.

When violence does become the preferred option, what does it achieve? Mixed findings here – in the short term, a few government concessions (eg abandoning price rises), but few medium term improvements. What the research was unable to answer was the longer term impact of violent protest, for example in delegitimizing existing power holders and paving the way for new political groupings, as the anti-austerity riots in Latin America in the 1980s and 1990s arguably did.

And (of course) a few constructive whinges:

The work thus far is surprisingly weak on gender. Perhaps more than any other topic, food bridges the public and private spheres, and is often a focus for women’s engagement outside the home. But while the leadership of peaceful civil society movements such as India’s Right to Food movement is largely female (see right), riots tend to be a young guy thing. So what happens to the gender dimension when protests turn violent? I hope there’s still time to look at that before the papers are finalised.

is often a focus for women’s engagement outside the home. But while the leadership of peaceful civil society movements such as India’s Right to Food movement is largely female (see right), riots tend to be a young guy thing. So what happens to the gender dimension when protests turn violent? I hope there’s still time to look at that before the papers are finalised.

There seems to be a possible typology of riots emerging here:

Defensive (drop those price rises, now!)

Cathartic (I’ve had enough, I want to smash something)

Genuine programmatic (politics has to change)

Manipulated programmatic (political leader stirs up riots to pursue his agenda)

Would be good to see if that can be developed further.

Finally, for once, I started to worry if there was too much deference to history here, in particular English history. University of Tennessee historian John Bohstedt described the 18th Century riots as the ‘first draft of the welfare state’ and saw events since 2008 as an analogous process, but is that true? For example, the interviews suggest very few of the rioters describe these things as food riots – they are often triggered by something else, such as transport price hikes. Does our progressive, but still colonial historical baggage distort our understanding of what’s going on? That’s as close to heresy as I’m prepared to go today.

February 18, 2014

Somaliland v Somalia: great new paper on an extraordinary ‘natural experiment’ in aid and governance

Could someone please clone Sarah Phillips? The University of Sydney political scientist has a great new Developmental Leadership Program (DLP) paper out on Somaliland, following her excellent paper a few years ago on Yemen.

Political Settlements and State Formation: The Case of Somaliland may not sound like much of a page turner, but it is brilliant. It explores one of those natural experiments beloved of researchers – what can we learn when two neighbouring countries part company and head off in different directions (North v South Korea, West v East Germany).

Phillips compares Somaliland v Somalia – while the first has emerged from the shared chaos of the 1990s (and a brutal effort by  Somalia to put down Somaliland separatists) into the sunlit uplands of relative peace and stability (some taxation, rudimentary public services, security, two peaceful presidential transitions through the ballot box, including one to the opposition), the other is the quintessential failed state. How come?

Somalia to put down Somaliland separatists) into the sunlit uplands of relative peace and stability (some taxation, rudimentary public services, security, two peaceful presidential transitions through the ballot box, including one to the opposition), the other is the quintessential failed state. How come?

Her conclusions do not make comfortable reading, for they trample on any number of received wisdoms. Try these on for size:

Somaliland’s government has received virtually no direct financial aid, largely because it is not internationally recognized. The country itself gets a lot of aid via NGOs, UN projects etc etc, but the government has been generally outside this loop, forced to rely on local sources of funding.

Perhaps more important than the financial aspects, this meant there was no pressure to accept template political institutions from outside. Instead, Somaliland had time and political space to negotiate its own (e.g. clan-based) political settlements. The process involved a series of ad hoc, messy, consultative, and local peace conferences. In the most important conference, in 1993, one group stalled proceedings by reciting the Koran for several days. That’s not in the good governance playbook.

The peace process was almost entirely locally funded, due to Somaliland’s unrecognized status (so no bilateral aid or loans were available). That produced a strong sense of local ownership (literally). In the words of one minister, when asked by Phillips about aid ‘Aid is not what we desire because [then] they decide for us what we need’.

What’s less discussed is the power politics that underlies this transition. The second president used private loans to demobilise about 5,000 militia fighters. He offered stability (and tax breaks) to the business elite in exchange for funding demobilisation and the nascent state institutions. This was effective but certainly not inclusive – the elite came mainly from the President’s own clan. But according to Phillips, Somalilanders generally still see it as a legitimate process – that’s what leaders do.

The paper highlights the critical political importance of elite secondary schools in forging leadership. Available to a relatively small group of often privileged Somalilanders, this is in stark contrast to the donor emphasis on universal primary education. In particular, many of Phillips’ interviews led to the Sheekh Secondary School, set up by Richard Darlington, who fought in WWII as the commander of the Somaliland Protectorate contingent. Sheekh took only 50 kids a year and trained them in leadership, critical thought and standard (Darlington borrowed from the curriculum of his old school, Harrow). Sheekh provided 3 out of 4 presidents, plus any number of vice presidents, cabinet members etc. And no it isn’t a weird Somaliland version of Eton and Harrow (I asked) – it stressed student intake from all clans, especially from the more marginalized ones.

The paper highlights the critical political importance of elite secondary schools in forging leadership. Available to a relatively small group of often privileged Somalilanders, this is in stark contrast to the donor emphasis on universal primary education. In particular, many of Phillips’ interviews led to the Sheekh Secondary School, set up by Richard Darlington, who fought in WWII as the commander of the Somaliland Protectorate contingent. Sheekh took only 50 kids a year and trained them in leadership, critical thought and standard (Darlington borrowed from the curriculum of his old school, Harrow). Sheekh provided 3 out of 4 presidents, plus any number of vice presidents, cabinet members etc. And no it isn’t a weird Somaliland version of Eton and Harrow (I asked) – it stressed student intake from all clans, especially from the more marginalized ones.

Somalilanders believe they are special, but also at risk:

‘For Somalilanders, the threat of violence was less from an external invasion than an internal combustion. This perception had profound impacts on the institutions – and the ideas about violence that undergird them – that were fostered during this period. Protection from violence was viewed as an internal matter, and if violence had been a political tool and a political choice for local actors in the recent past it was believed that it could become so again with little warning. Peace was precarious, and it rested on a tenuous balance between coalitions with roughly equivalent power. Somaliland’s civil wars in the mid-1990s provided the opportunity for local coalitions to determine that no one clan could dominate the others.’

Conclusion (with due nods to local context, can’t generalize etc etc)? There is an upside to detachment from external aid and political influence. In the right circumstances, being detached can promote co-dependence between local elites, leading to durable, authentic institutions: ‘legitimate institutions are those born through local political and social processes, and that these are largely shaped through the leadership process.’

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers