Duncan Green's Blog, page 198

January 22, 2014

Why hasnât the 2008-14 shock produced anything like the New Deal?

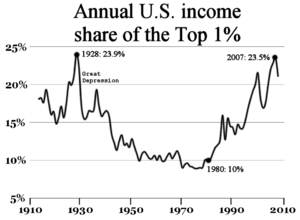

Ricardo Fuentes gave a staff talk this week on his big new paper (with Nick Galasso) on the links between economic and political power. What struck me was a very serious ‘dog that didn’t bark’. The 1929 collapse and the Great Depression led to profound reform in the US, with the New Deal and a sharp reversal of rising inequality. A series of shocks prompted similar redistributive transformations in Europe (rise of fascism, World War Two) and East Asia (Chinese revolution, World War Two).

Fast forward to 2008-14. This time around, much more timid radical financial reforms have produced absolutely nothing in terms of  redistribution – 95% of US economic growth since 2008 has ended up in the hands of the richest 1%. So why is this time so different, and what can be done about it?

redistribution – 95% of US economic growth since 2008 has ended up in the hands of the richest 1%. So why is this time so different, and what can be done about it?

In response, Ricardo highlighted a paradox. The very success of Ben Bernanke who, instead of tightening the tourniquet and triggering a massive depression, as in the 1930s, pumped money into the economy, avoided a global financial meltdown. But that in turn eased the pressure for reform. Sounds a bit Trotskyist (worse is better), but also sounds about right. Just as revolutions in Latin America needed both revolutionaries and a really inept dictator to triumph (Cuba/Batista, Nicaragua/Somoza), maybe New Deal style revolutions require a level of economic self harm that no longer exists. Tricky.

So assuming that killing all the economists is not a feasible policy option (sorry to disappoint you), what might be the political elements that enable us to scale the mountain that the financial elites have assembled to defend their privileges, and redirect economic activity towards a greater goal? What might be some countervailing trends?

Overall, this problem seems most acute in the financial centres, where the financial elites are now so deeply dug in, that, like particularly determined ticks, that they may be impossible to dislodge (in the UK Ha-Joon Chang thinks the Labour Party is still under the financiers’ spell).

Outside the US and UK, the balance of forces may be more promising: A surge in levels of democracy, and active citizenship in many countries, (combined with better economic management) underpins the main ray of light in reducing inequality – rapid progress in Latin America over the last 15 years. That message is spreading to other regions.

What about sources of hope nearer the heart of the financial-political complex? Some straws to clutch at:

Reshaping the elite’s understanding of its self interest. Once inequality starts to risk social breakdown, the logic of further concentration of wealth starts to unravel. A lot of serious, mainstream players get this, including the IMF and the WEF (currently running the Davos gabfest).

Maybe not enough time has elapsed yet – the New Deal only came four years after the Wall Street crash, and its more radical variant a couple of years after that. Could all the incremental progress since 2008 on transparency, tax dodging, financial transactions taxes, capping bonuses etc reach some kind of tipping point that starts to have a serious impact on inequality?

Could climate change or other environmental risks supply the kind of existential threat previously provided by war and political upheaval ?

Some role for digital democracy and accountability (OK, maybe the straw clutchism is getting out of control here)

Where next – up or down?

But I have to say, it feels like the political chips in the UK and US are just not as favourable this time around. Maybe pressure from outside will shift that, as part of the rise of the rest, but I wouldn’t bet on it. As for changing things from within, that probably means spending more time working with elite champions, rather than just pursuing ‘us and them’ narratives (however tempting). In the seminar, Alan Doran suggested two interesting avenues to explore:

- Find champions among 3rd generation plutocrats (1st generation gets moderately rich, 2nd generation gets megarich, then their kids wonder what life’s all about)

- The megarich can’t spend all their money on stuff, so the key is how they invest the rest – why not do the research for what constitutes a distributionally progressive/regressive investment portfolio and lobby them to change accordingly?

Sorry if this sounds too lily-livered and gradualist, but the comparison between 2008 and the 1930s suggests that, absent a war or other major shock, a new New Deal isn’t going to happen any time soon, at least not anywhere near the financial epicentres.

One final thought, connecting with previous posts on complexity and ‘how to campaign when we don’t have the solution’, I think what Ricardo and Nick so brilliantly (85 individuals owning the same as the poorest half of the world’s population – 3.5 billion, is a classic killer fact), is actually the best strategy. It’s what Matt Andrews recommends as the right role for outsiders – focus on identifying and amplifying the problem, because the solutions are likely to be complicated, context specific, and discovered through trial and error by those involved, not lifted wholesale from the recommendations shopping lists of thinktanks and NGOs.

Any thoughts?

Why hasn’t the 2008-14 shock produced anything like the New Deal?

Ricardo Fuentes gave a staff talk this week on his big new paper (with Nick Galasso) on the links between economic and political power. What struck me was a very serious ‘dog that didn’t bark’. The 1929 collapse and the Great Depression led to profound reform in the US, with the New Deal and a sharp reversal of rising inequality. A series of shocks prompted similar redistributive transformations in Europe (rise of fascism, World War Two) and East Asia (Chinese revolution, World War Two).

Fast forward to 2008-14. This time around, much more timid radical financial reforms have produced absolutely nothing in terms of  redistribution – 95% of US economic growth since 2008 has ended up in the hands of the richest 1%. So why is this time so different, and what can be done about it?

redistribution – 95% of US economic growth since 2008 has ended up in the hands of the richest 1%. So why is this time so different, and what can be done about it?

In response, Ricardo highlighted a paradox. The very success of Ben Bernanke who, instead of tightening the tourniquet and triggering a massive depression, as in the 1930s, pumped money into the economy, avoided a global financial meltdown. But that in turn eased the pressure for reform. Sounds a bit Trotskyist (worse is better), but also sounds about right. Just as revolutions in Latin America needed both revolutionaries and a really inept dictator to triumph (Cuba/Batista, Nicaragua/Somoza), maybe New Deal style revolutions require a level of economic self harm that no longer exists. Tricky.

So assuming that killing all the economists is not a feasible policy option (sorry to disappoint you), what might be the political elements that enable us to scale the mountain that the financial elites have assembled to defend their privileges, and redirect economic activity towards a greater goal? What might be some countervailing trends?

Overall, this problem seems most acute in the financial centres, where the financial elites are now so deeply dug in, that, like particularly determined ticks, that they may be impossible to dislodge (in the UK Ha-Joon Chang thinks the Labour Party is still under the financiers’ spell).

Outside the US and UK, the balance of forces may be more promising: A surge in levels of democracy, and active citizenship in many countries, (combined with better economic management) underpins the main ray of light in reducing inequality – rapid progress in Latin America over the last 15 years. That message is spreading to other regions.

What about sources of hope nearer the heart of the financial-political complex? Some straws to clutch at:

Reshaping the elite’s understanding of its self interest. Once inequality starts to risk social breakdown, the logic of further concentration of wealth starts to unravel. A lot of serious, mainstream players get this, including the IMF and the WEF (currently running the Davos gabfest).

Maybe not enough time has elapsed yet – the New Deal only came four years after the Wall Street crash, and its more radical variant a couple of years after that. Could all the incremental progress since 2008 on transparency, tax dodging, financial transactions taxes, capping bonuses etc reach some kind of tipping point that starts to have a serious impact on inequality?

Could climate change or other environmental risks supply the kind of existential threat previously provided by war and political upheaval ?

Some role for digital democracy and accountability (OK, maybe the straw clutchism is getting out of control here)

Where next – up or down?

But I have to say, it feels like the political chips in the UK and US are just not as favourable this time around. Maybe pressure from outside will shift that, as part of the rise of the rest, but I wouldn’t bet on it. As for changing things from within, that probably means spending more time working with elite champions, rather than just pursuing ‘us and them’ narratives (however tempting). In the seminar, Alan Doran suggested two interesting avenues to explore:

- Find champions among 3rd generation plutocrats (1st generation gets moderately rich, 2nd generation gets megarich, then their kids wonder what life’s all about)

- The megarich can’t spend all their money on stuff, so the key is how they invest the rest – why not do the research for what constitutes a distributionally progressive/regressive investment portfolio and lobby them to change accordingly?

Sorry if this sounds too lily-livered and gradualist, but the comparison between 2008 and the 1930s suggests that, absent a war or other major shock, a new New Deal isn’t going to happen any time soon, at least not anywhere near the financial epicentres.

One final thought, connecting with previous posts on complexity and ‘how to campaign when we don’t have the solution’, I think what Ricardo and Nick so brilliantly (85 individuals owning the same as the poorest half of the world’s population – 3.5 billion, is a classic killer fact), is actually the best strategy. It’s what Matt Andrews recommends as the right role for outsiders – focus on identifying and amplifying the problem, because the solutions are likely to be complicated, context specific, and discovered through trial and error by those involved, not lifted wholesale from the recommendations shopping lists of thinktanks and NGOs.

Any thoughts?

January 21, 2014

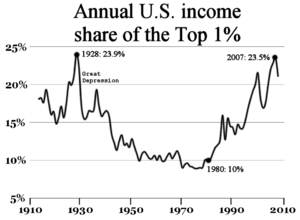

Lant Pritchett on why we struggle to think in systems (and look for heroes and villains instead)

This passage in Lant Pritchett’s new book, The Rebirth of Education, (reviewed here yesterday), had me gurgling with pleasure. It  explains, in vintage Pritchett prose, why we all find it so hard to think in terms of systems, rather than agents (i.e. heroes and villains). He totally nails the origins of that glazed look I see in the eyes of my Oxfam colleagues when I start going on about systems, complexity, emergence etc:

explains, in vintage Pritchett prose, why we all find it so hard to think in terms of systems, rather than agents (i.e. heroes and villains). He totally nails the origins of that glazed look I see in the eyes of my Oxfam colleagues when I start going on about systems, complexity, emergence etc:

“I am going on at length about this because this book is about explaining and fixing poor learning outcomes by fixing broken systems, not fixing people. But I have to go on about this because system explanations just have no appeal to people, myself included. Agent-centered explanations are powerfully appealing to us, on a very deep level. Believe me, if your child says, “Daddy, tell me a story,” you can be sure he or she wants a story with agents, heroes and villains who have goals and make plans and overcome obstacles.

Even economists when they try to explain Pareto optimality resort to making the ontological unfamiliar seem plausible by invoking “an invisible hand”—and hence making it seem familiar. “Oh,” say sophomores on hearing the invisible hand metaphor, “like an agent with a hand willed it. Now I get it”—and hence deeply don’t get it.

But even as an economist who loves system explanations in the domain of my expertise, I am bored silly by historians who tell the stories of structures and institutions and geographic constraints (I have never been able to make my way through any small part of the French historian Braudel, for instance, though I often think that I should). I love a good yarn about American independence that does not involve the carrying trade but does involve George Washington and his bravery. The appeal of agent-centered, human narrative explanations over systemic explanations is why no one—except perhaps you—is reading this book.

This is because nearly all of our success as organisms is driven by understanding stuff and agents. Just as none of us really needs to understand quantum mechanics or general relativity to live our whole lives as successful, fulfilled, productive individuals, the number of times any of us needs to understand systems is vanishingly small. You can have a successful professional career without understanding systems. You can have a happy marriage without understanding systems (perhaps more likely, in fact: try asking your spouse sometime about the system of marriage—such as “Why did monogamy as an organizational form of the family triumph over polygamy?”—and see how that works for you). You can raise lovely children without understanding systems.

This is because nearly all of our success as organisms is driven by understanding stuff and agents. Just as none of us really needs to understand quantum mechanics or general relativity to live our whole lives as successful, fulfilled, productive individuals, the number of times any of us needs to understand systems is vanishingly small. You can have a successful professional career without understanding systems. You can have a happy marriage without understanding systems (perhaps more likely, in fact: try asking your spouse sometime about the system of marriage—such as “Why did monogamy as an organizational form of the family triumph over polygamy?”—and see how that works for you). You can raise lovely children without understanding systems.

You just never need to really understand systems, until you do. Because even though life is always really about agents, it is also really always about systems.”

January 20, 2014

How do we move from getting kids into school to actually educating them? Provocative new book by Lant Pritchett

I approached Lant Pritchett’s new book ‘The Rebirth of Education’ with glee and trepidation. Glee because Lant is one of the smartest,  wittiest and best writers and thinkers on development. Trepidation because this issue is an intellectual minefield of Somme-like proportions (remember the epic Kevin Watkins v Justin Sandefur battle?). And sure enough, Lant took me into all kinds of uncomfortable places. Allow me to share my confusion.

wittiest and best writers and thinkers on development. Trepidation because this issue is an intellectual minefield of Somme-like proportions (remember the epic Kevin Watkins v Justin Sandefur battle?). And sure enough, Lant took me into all kinds of uncomfortable places. Allow me to share my confusion.

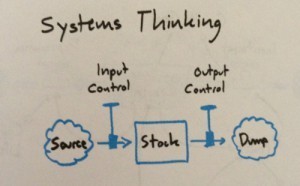

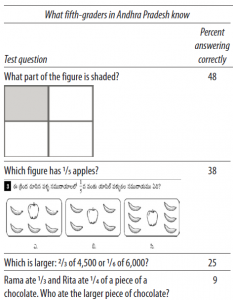

First the book. Based on a data-tastic summary of a lot of research and case studies, Lant argues, in the words of the book’s subtitle, that ‘Schooling Ain’t Learning’:

In India less than half of children surveyed in grade 5 could read a story for second graders (and over 1 in 4 could not read a simple sentence), and only slightly more than half could do subtraction. Results over several years were getting worse, not better. See graphic for more examples.

In Tanzania over 65 percent of students who sat the 2012 examination for secondary school (Form IV) completers failed, with the worst possible results.

A majority of 15 year-olds in low- and middle-income countries have only learned enough to reach the bottom 5 percent of their peers in high-income countries.

The evidence is piled high that there is a crisis in education – kids are now in school, thanks to a huge effort by governments, publics and aid donors – but they aren’t learning anywhere near enough. In most countries, kids dropping out through boredom and futility far exceed the lack of enrolment as a cause for under-achievement. What a horrendous waste.

The evidence is piled high that there is a crisis in education – kids are now in school, thanks to a huge effort by governments, publics and aid donors – but they aren’t learning anywhere near enough. In most countries, kids dropping out through boredom and futility far exceed the lack of enrolment as a cause for under-achievement. What a horrendous waste.

How did it get like this and what could turn it around? The big proposition here is that the system required to deliver mass enrolment is fundamentally different from that needed to deliver genuine education. Lant is adamant that ‘more of the same’ – more schools, more teachers, more books, more teacher training – cannot deliver if it takes place within the current system, and cites a lot of cases where such increases in inputs have not delivered. He calculates that even if Mexico increased spending on its current education system fivefold, it would still lag way behind the OECD average.

Instead, he argues that this is a system problem. (His writing on systems is superb – more on that tomorrow). He draws a distinction between ‘spider’ and ‘starfish’ systems:

‘A spider uses its web to expand its reach, but all information created by the vibrations of the web must be processed, decisions made, and actions taken by one spider brain at the center of the web. The starfish, in contrast, is a very different kind of organism. Many species of starfish actually have no brain. The starfish is a radically decentralized organism with only a loosely connected nervous system. The starfish moves not because the brain processes information and decides to move but because the local actions of its loosely connected parts add up to movement.’

i.e. education systems have to move from a state-led command and control model to a looser network that encourages evolution and emergent change. He likens spider systems to an eggshell that has allowed embryonic education systems to reach full enrolment, but must now break to allow the move from enrolment to actual education.

He argues that the switch from spider to starfish ‘is not the usual battleground of ‘markets’ v ‘governments’’, but one of accountability,  where state-run systems in Germany, France and the Netherlands have produced effective starfish systems. I’m not entirely convinced by that. Although he does have examples of starfish states, he then doesn’t explore them, or draw any lessons for today’s education reformers. This seems an extraordinary omission.

where state-run systems in Germany, France and the Netherlands have produced effective starfish systems. I’m not entirely convinced by that. Although he does have examples of starfish states, he then doesn’t explore them, or draw any lessons for today’s education reformers. This seems an extraordinary omission.

Instead the tone of the book is overwhelmingly hostile to state education and evil bureaucrats and teachers’ unions seeking only to defend their ‘vested interests’ and snuff out innovation. And the positive examples he cites are community-controlled schools, private providers, decentralized ‘small government’ and charter schools – hardly a statist shopping list.

Where he gets really interesting (and where I particularly need a steer from readers who know more about educational history than me) is on the political economy of education. He argues that the dominant driver in the introduction of mass public education has never been a desire to educate, but ‘everywhere and always a contest for the control of socialization’, a process which the state refuses to outsource. He cites a wonderfully frank 19th Century Japanese education minister: ‘In administration of all schools, it must be kept in mind, what is to be done is not for the sake of the pupils, but for the sake of the country.’

He sees two other drivers of mass education:

The need to prepare workers for a modernizing economy, but that doesn’t explain why both slow and fast-growing economies have moved so fast to introduce mass public systems

A desire to ‘keep up with the Joneses’ by e.g. meeting the MDGs, which leads to a focus on enrolment, rather than education

His conclusion?

‘The spider systems we have today were designed in the nineteenth century and adapted and adopted in the twentieth century to meet a certain set of demands: to prepare workers for a transition out of agriculture, to build nations to support states, and to legitimate the regimes that controlled those states. It would be extraordinary indeed if those spiders just so happened to be systems designed for the learning and educational challenges the youth of the twenty-first century will face.’

True to his understanding of emergent change in complex systems, he then refuses to provide a complete blueprint for an alternative, and instead suggests six characteristics of effective starfish systems:

Open: How is the entry and exit of providers of schooling structured?

Locally operated: Do those who manage schools and teach in schools (and the local coalitions of parents and citizens they are accountable to) have autonomy over how their school is operated?

Performance pressured: Are there clear, measured, achievable outcome metrics against which the performance of schools can be assessed?

Professionally networked: Do teachers feel a common professional ethos and linkages among themselves as professional educators?

Technically supported: Are the schools, principals, and teachers given access to the technical support they need to expand their own capacities?

Flexibly financed: Can resources flow naturally (without topdown decisionmaking) into those schools and activities within schools that have proved to be effective?

As examples he cites the US/UK university system, the International Baccalaureate and Brazil’s recent education reforms.

Fascinating, but I have some concerns:

What are the trade-offs in moving from spider to starfish? What will be the impact on equity of decentralizing control or finance, let alone of a much greater role for private providers?

And can we really assume that non-state providers will be any freer of suspect motives than governments? Religious schools?

Can a real education reform process really be this jaundiced about the motivation of teachers and their organizations? Surely they have to be far more central?

100% enrolment is most definitely not a done deal, especially for the most marginalized. Watch out for next week’s Global Monitoring Report on that.

Lant’s claim that ‘more’ (teachers, textbooks, classrooms) doesn’t help is, to put it mildly, contested

Which (even though I, like everyone else, am convinced of the crisis in education) all leaves me floundering between two apparently contradictory intellectual poles. I am convinced (as is Oxfam) that state provision (not just funding) has historically played a fundamental role in producing equitable and effective essential services. I am also convinced that systems thinking, applying the ideas of emergent change and evolution etc, can provide rich ideas on how change happens. To what extent are the two compatible/in conflict? Off to my padded cell to agonize……..

January 19, 2014

âWorking for the Fewâ: top new report on the links between politics and inequality

As the worldâs self-appointed steering committee gathers in Davos, 2014 is already shaping up as a big year for inequality. The World  Economic Forumâs âOutlook on the Global Agenda 2014â ranks widening income disparities as the second greatest worldwide risk in the coming 12 to 18 months (Middle East and North Africa came top, since you ask).

Economic Forumâs âOutlook on the Global Agenda 2014â ranks widening income disparities as the second greatest worldwide risk in the coming 12 to 18 months (Middle East and North Africa came top, since you ask).

So itâs great to see âWorking for the Fewâ, a really excellent new Oxfam paper by Ricardo Fuentes and Nick Galasso, tackling an issue best summed up by US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis in the aftermath of the Great Depression, âWe may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of the few, but we cannot have both.â i.e. the politics of inequality and redistribution.

The Brandeis quote is particularly relevant because this time really is different. After the 2008 global meltdown, we have not seen anything like the New Deal, in terms of redistribution or reform. The paper argues that this is because political capture by a small economic elite is much more complete this time around.

The numbers take your breath away â my favourite newkiller fact from the report (and thereâs a lot of competition): The bottom half of the worldâs population owns the same as the richest 85 people in the world. Read that again, please.

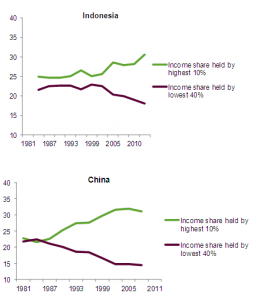

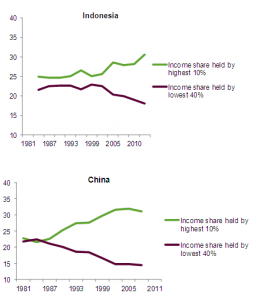

And itâs getting worse. In country after country, the ratio of the income of the top 10% and bottom 40% resembles an opening jaw (hereâs China and Indonesia) â I tried to get Oxfam to superimpose a yawning crocodile on the graphs, but sadly, they said no.

And itâs getting worse. In country after country, the ratio of the income of the top 10% and bottom 40% resembles an opening jaw (hereâs China and Indonesia) â I tried to get Oxfam to superimpose a yawning crocodile on the graphs, but sadly, they said no.

Why should Oxfam care about what happens at the top? Shouldn’t we just worry about helping the people at the bottom? No, because of political capture – this is not about the politics of envy, but the politics of extreme wealth. There is a vicious cycle through which a high degree of wealth funds lobbyists and campaign contributions, which buys favourable policies, which concentrates wealth even more.

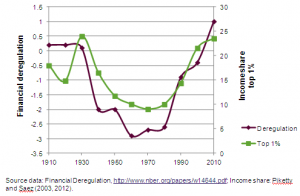

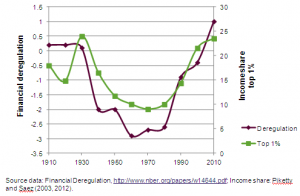

We are witnessing a titanic battle between two principles – an idealized market ($1 one vote) and an idealized democracy (one person one vote). Real politics is born of the tussle between the two: sometimes money, sometimes people wins out. Right now, money is doing far too well, as this graph of a measure of financial deregulation and the income share of the top 1% shows only too well.

All this suggests two urgent tasks: reduce the concentration of wealth and income, and build  better firewalls between wealth and political influence. We need to do both if we are to disrupt and reverse the vicious cycle.

better firewalls between wealth and political influence. We need to do both if we are to disrupt and reverse the vicious cycle.

Public opinion is increasingly on our side on this one. A survey conducted for Oxfam in six countries (Spain, Brazil, India, South Africa, the UK and the US) showed that a majority of people believe that laws are skewed in favour of the rich â in Spain eight out of 10 people agreed. Another recent poll of low-wage earners in the US reveals that 65 percent believe that Congress passes laws that predominantly benefit the wealthy.

There are clear examples of success, both historical and current, in reversing the political-economic death spiral. The US and Europe in the three decades after World War II reduced inequality while growing prosperous. Latin America has significantly reduced inequality in the last decade â through more progressive taxation, public services, social protection and decent work. Central to this progress has been popular politics that represent the majority, instead of being captured by a tiny minority.

The particular combination of policies required should be tailored to each national context. But developing and developed countries that have successfully reduced economic inequality provide some suggested starting points, notably:

Cracking down on financial secrecy and tax dodging;

Redistributive transfers; and strengthening of social protection schemes;

Investment in universal access to healthcare and education;

Progressive taxation;

Strengthening wage floors and worker rights;

Removing the barriers to equal rights and opportunities for women.

I read Angus Deaton’s new book, The Great Escape, over Christmas (review in the pipeline). Deaton argues that the breakup of great civilisations is often preceded by a period of sclerosis and distributive conflict. Unless we can curb the current tendency to increased concentration of power both in politics and economics (and the reinforcing feedback loops between them), the risks to stability can only grow. Letâs hope this discussion gets somewhere in Davos.

There’s the have nots. And then there’s the have yachts.

‘Working for the Few’: top new report on the links between politics and inequality

As the world’s self-appointed steering committee gathers in Davos, 2014 is already shaping up as a big year for inequality. The World  Economic Forum’s ‘Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014’ ranks widening income disparities as the second greatest worldwide risk in the coming 12 to 18 months (Middle East and North Africa came top, since you ask).

Economic Forum’s ‘Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014’ ranks widening income disparities as the second greatest worldwide risk in the coming 12 to 18 months (Middle East and North Africa came top, since you ask).

So it’s great to see ‘Working for the Few’, a really excellent new Oxfam paper by Ricardo Fuentes and Nick Galasso, tackling an issue best summed up by US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis in the aftermath of the Great Depression, ‘We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of the few, but we cannot have both.’ i.e. the politics of inequality and redistribution.

The Brandeis quote is particularly relevant because this time really is different. After the 2008 global meltdown, we have not seen anything like the New Deal, in terms of redistribution or reform. The paper argues that this is because political capture by a small economic elite is much more complete this time around.

The numbers take your breath away – my favourite newkiller fact from the report (and there’s a lot of competition): The bottom half of the world’s population owns the same as the richest 85 people in the world. Read that again, please.

And it’s getting worse. In country after country, the ratio of the income of the top 10% and bottom 40% resembles an opening jaw (here’s China and Indonesia) – I tried to get Oxfam to superimpose a yawning crocodile on the graphs, but sadly, they said no.

And it’s getting worse. In country after country, the ratio of the income of the top 10% and bottom 40% resembles an opening jaw (here’s China and Indonesia) – I tried to get Oxfam to superimpose a yawning crocodile on the graphs, but sadly, they said no.

Why should Oxfam care about what happens at the top? Shouldn’t we just worry about helping the people at the bottom? No, because of political capture – this is not about the politics of envy, but the politics of extreme wealth. There is a vicious cycle through which a high degree of wealth funds lobbyists and campaign contributions, which buys favourable policies, which concentrates wealth even more.

We are witnessing a titanic battle between two principles – an idealized market ($1 one vote) and an idealized democracy (one person one vote). Real politics is born of the tussle between the two: sometimes money, sometimes people wins out. Right now, money is doing far too well, as this graph of a measure of financial deregulation and the income share of the top 1% shows only too well.

All this suggests two urgent tasks: reduce the concentration of wealth and income, and build  better firewalls between wealth and political influence. We need to do both if we are to disrupt and reverse the vicious cycle.

better firewalls between wealth and political influence. We need to do both if we are to disrupt and reverse the vicious cycle.

Public opinion is increasingly on our side on this one. A survey conducted for Oxfam in six countries (Spain, Brazil, India, South Africa, the UK and the US) showed that a majority of people believe that laws are skewed in favour of the rich – in Spain eight out of 10 people agreed. Another recent poll of low-wage earners in the US reveals that 65 percent believe that Congress passes laws that predominantly benefit the wealthy.

There are clear examples of success, both historical and current, in reversing the political-economic death spiral. The US and Europe in the three decades after World War II reduced inequality while growing prosperous. Latin America has significantly reduced inequality in the last decade – through more progressive taxation, public services, social protection and decent work. Central to this progress has been popular politics that represent the majority, instead of being captured by a tiny minority.

The particular combination of policies required should be tailored to each national context. But developing and developed countries that have successfully reduced economic inequality provide some suggested starting points, notably:

Cracking down on financial secrecy and tax dodging;

Redistributive transfers; and strengthening of social protection schemes;

Investment in universal access to healthcare and education;

Progressive taxation;

Strengthening wage floors and worker rights;

Removing the barriers to equal rights and opportunities for women.

I read Angus Deaton’s new book, The Great Escape, over Christmas (review in the pipeline). Deaton argues that the breakup of great civilisations is often preceded by a period of sclerosis and distributive conflict. Unless we can curb the current tendency to increased concentration of power both in politics and economics (and the reinforcing feedback loops between them), the risks to stability can only grow. Let’s hope this discussion gets somewhere in Davos.

There’s the have nots. And then there’s the have yachts.

January 17, 2014

‘Rage may overwhelm us all.’ Vintage Martin Wolf in the FT

Superb writing from Martin Wolf in the FT:

“In the past three decades we have seen the emergence of a globalised economic and financial elite. Its members have become ever more detached from the countries that produced them. In the process, the glue that binds any democracy – the notion of citizenship – has weakened. The narrow distribution of the gains of economic growth greatly enhances this development. This, then, is ever more a plutocracy. A degree of plutocracy is inevitable in democracies built, as they must be, on market economies. But it is always a matter of degree. If the mass of the people view their economic elite as richly rewarded for mediocre performance and interested only in themselves, yet expecting rescue when things go badly, the bonds snap. We may be just at the beginning of this long-term decay.

The result is the birth of angry populism throughout the west, mostly the xenophobic populism of the right. The characteristic of rightwing populists is that they kick down. If elites continue to fail, we will go on watching the rise of angry populists. The elites need to do better. If they do not, rage may overwhelm us all.”

January 16, 2014

Cautionary Tales for Development Folk

Back in the 80s, I worked with Neil Macdonald on Central American human rights. Since then he’s been an aid biz all rounder, workign on media, planning, monitoring etc etc. Now entering his greybeard, guru years (actually, he’s had a grey beard for decades), he’s written a rather sweet and  educational set of stories, part anecdote, part parable, about the practice and pitfalls of aid work. Reminds me a bit of Robert Chambers or John Ambler. Some of the best are about getting things wrong, realizing it and putting them right. Here’s a sample. The 40 page book is available in Kindle format.

educational set of stories, part anecdote, part parable, about the practice and pitfalls of aid work. Reminds me a bit of Robert Chambers or John Ambler. Some of the best are about getting things wrong, realizing it and putting them right. Here’s a sample. The 40 page book is available in Kindle format.

“Story 14. There has to be a roof

What is a latrine? A hole in the ground. A platform. Walls for privacy. To save costs we didn’t bother with roofs. Nobody was going to spend much time in these dank little huts.

But there we were wrong. It was the women especially who insisted to us that we had to modify the design. There has to be a roof, they said. And of course, a latrine is not just a latrine. For the women especially, this was the one place where they could be alone, freed from the nagging demands of husbands, fathers, children, brothers, and older women. This was their space and their privacy. They wanted to spend as long as they possibly could in the luxury of the latrine. Even when it rained.

We modified the design, and included a roof.

Story 15. There has to be a solid floor

We were building schools. Or more correctly, we were supporting the communities to build their own schools. Schools that would make education accessible to those children who couldn’t walk the ten or more kilometres to school and back or who needed to spend part of their days working. The schools in each community were variants of a standard design that communities could largely make for themselves using locally available materials.

We consulted extensively beforehand on the design. What should a basic primary school look like? We came up with one or two classroom variants, with space for reading corners and for teacher’s needs. Ideally there were two latrines, one for each sex, and washing facilities.

We consulted the children too. We were surprised by what they came up with. Repeatedly they said the floor had to be solid. Spaced planks on a foundation wouldn’t do. We asked why. With equal surprise and withering scorn they told us:

“If we drop our pencils and they fall through cracks in the floor we’ll have to go home and tell our parents we need a new pencil. Pencils cost a lot. They’ll hit us.”

Every one of those schools has a solid floor.

Story 16. Things weren’t the same

It was a big programme. A UN-funded programme to provide standpipes in every village street. No longer would people, most of them women and children, have to trek long distances in the sun and wait hours for their turn at the pump. No longer would they have to walk back over aching kilometres, burdened by canisters of water almost as heavy as they were.

Communities were thrilled. Running water at the end of every street! They could hardly wait for the water engineers to arrive. When the work was done, the communities were delighted. The programme team went from success to success.

Six months later came the follow up visits, the check on how things were going. From village to village the story was the same. Standpipes had been ripped out. People were again walking long distances to the well, and queuing for hours in the sun for water. The project team were bewildered, but could get no clear explanation as to why this was happening. Villagers simply said, “We didn’t like them. Things weren’t the same.”

Eventually a team of researchers was sent in to find out the reasons. It took a lot of investigation. It turned out that fetching water wasn’t simply fetching water. For the women, it was an opportunity, sometimes the only opportunity, to get away from watchful and censuring eyes. It was their privacy. For almost everyone the wait at the wall was not just a wait. This was where news was exchanged, deals done, obligations discharged, marriages arranged. The queue was one of the most important community institutions. But even the communities themselves had been unaware of this.

Building community centres went some way to remedying problem, though this was not enough to address the gender issue.”

January 15, 2014

What’s the the best/worst country in which to feed your family? New Oxfam report.

Oxfam researcher and ace number cruncher Deborah Hardoon introduces its new Good Enough to Eat index.

Many of us will have overindulged this festive season. According to the British Diatetics Association, the average Brit puts on half a stone at Christmas. And it is not just Christmas Day itself, ‘the whole festive season is riddled with fat traps’.

After Christmas, we end up throwing a disgusting amount of food away. Part of the UK’s Love Food Hate Waste campaign, a WRAP study in 2012, found that over Christmas, we chuck out the equivalent of 2m turkeys, 5m Christmas puddings and 74m mince pies.

While food waste is often binned and then forgotten about, in August this year people in the London borough of Kingston upon Thames were reminded what happens to some of this waste when a giant ball of congealed fat was found clogging up the borough’s sewers. At 15 tonnes, this was declared the largest fatberg in British history (if you’re squeamish, look away now).

Massive over-eating combined with excessive food waste, all at a time of continued economic hardship, when more people than ever before are relying on food banks in the UK, presents an inefficient and wasteful picture of our consumption of food in the UK, but also one with dangerous health, safety and environmental implications. And Christmas excess is just the tip of the fatberg.

Understanding Food systems and critically why, despite there being enough for everyone, one in eight people around the world do not have enough to eat, is a priority for Oxfam. Our Good Enough to Eat Index

, published this week, looks at the food system from a globally comparative perspective. It draws on data from eight different country level indicators related to people’s food consumption around the world. These indicators fall into four categories that capture whether people have enough to eat, the cost of food, the quality of food and the extent to which people eat unhealthily.

This is obviously not the last word on the matter; the food industry is big and globally diverse and there are many other food-map factors that influence what a person eats, from cultural influences to the marketing power of food companies. The production side of food also deserves urgent attention, with critical issues from food supply chains to impact on climate change raising important challenges at the local, national and global level. But limitations aside, this Index does offer a useful snapshot of some of the food challenges affecting different countries around the world.

At the bottom of the Index, we find countries that are faced with the compounding challenges of limited food, high food prices and poor food quality. Ranked bottom is Chad, where more than a third of children are underweight, food prices are third highest of all the 125 countries on the Index and just half the population has access to clean water.

At the same time, countries at the top of the Index are eating too much of the wrong foods, resulting in a major 21st century health crisis. In the top scoring country, the Netherlands, almost a quarter of the population are obese. Obesity carries a serious risk of diabetes, heart disease and some cancers, not to mention the more hard-to-measure implications for mental health and self esteem and putting a great strain on national health systems.

To unpack and understand the challenges that are presented at country level in our new Index, we have to go deeper and explore how the food system and the associated health and wellbeing implications interact and cannot be separated from wider socioeconomic disparities.

We have known for some years that obesity has become a major problem. In November 2013, a report by Public

Health England found that higher levels of obesity in the UK were found among more deprived groups. In children, the prevalence of obesity in the most deprived 10% of the population is approximately double that of the richest 10%. The study finds that lower income groups are both more likely to eat badly and are less physically active, particularly when excluding exercise related to work. In several public opinion surveys cited in the report, people say that the cost of healthy food is one of the main barriers to maintaining a balanced diet.

The food industry is global, as is the Index. At first glance, it highlights a clear global food distribution failure; too many calories in developed countries, too few in developing countries. But the true story is more complex, with important differences between groups of people within countries. Food poverty is not just a developing world concern, and as a recent ODI report finds, it is not just in richer countries that we need to be concerned with obesity; in fact the majority of people that are overweight now live in developing countries. “Here, the numbers of people affected more than tripled from around 250 million people in 1980 to 904 million in 2008”.. As food crosses borders both literally and through digital markets, it is clear that to address the common and interconnected challenges of the food system a global effort is needed to ensure that precious food resources are getting to the right people at the right price.

In 1798, when there were less than 1 billion people in the world, Thomas Malthus predicted that population growth would exceed agricultural production and the world would not be able to feed its people. Defying Malthus’ prediction, the Green Revolution and other agricultural and technological developments have enabled food production to outstrip population growth. However, if we look beyond narrow definitions of supply and demand, the Good Enough to Eat index shows clearly that the global food system today is failing to provide adequate and appropriate nutrition to the 7 billion people that now live on this planet. We must address this broken system with urgency if we are to end hunger and improve the health of people all over the world, whilst of course not forgetting the even bigger question of whether our current levels and methods of food production and resource use more generally are sustainable and equitable for our future.

Yep, this is still FP2P, but with an upgrade

Welcome back. Sharp-eyed readers may have noted that the blog looks a bit different this morning. It’s time for an upgrade, in  response to an accumulating backlog of glitches and the need to, you know, keep up with the times n tech. Blog masters Eddy Lambert and Ian Sullivan have worked their magic, and this is what they say about the redesign (I even understand some of it….):

response to an accumulating backlog of glitches and the need to, you know, keep up with the times n tech. Blog masters Eddy Lambert and Ian Sullivan have worked their magic, and this is what they say about the redesign (I even understand some of it….):

‘We have beefed up the search function. We think it is much stronger, please let us know your thoughts. In terms of archived blogs, we have plans to revamp how these are shown on a separate page and that is something we are looking to roll out post-launch.

Images should appear much better on mobile devices and through RSS readers.

Many comments said they liked the one page approach. We did want to play with this though to see if it improved readership of other content. Therefore, we have gone for a new format which keeps the top post as a single piece and then has excerpts from a number of posts so people can browse and pick a post to engage with. It was felt that the old format meant blogs had a very short life span. The new format seeks to address this.

The font is larger and the spacing is improved to make reading easier, whatever your age.

PDFs are now easier to download – 1 click instead of 3 and there is a fantastic option to print or save the post you are reading as a PDF. This is a great new function.

Hyperlinks will open in a new tab.

Link structure has been changed.

Image handling has improved so images can be enlarged in the post.

We have put in a Greatest Hits – be good to get people’s thoughts on this.

You can now subscribe to get updates when new comments are posted on a thread.

There is an option for more Monty Python videos to keep hilarious middle aged men happy.’

Other stuff they forgot to mention. Twitter feed now goes direct to page (see right). New and weird photo – Dr Evil? Mad Eye Moody?

We would appreciate any feedback, glitches, further suggestions etc. Any abuse should be sent directly to Eddy and Ian, but copy me in so I can gloat.

Normal service will be resumed tomorrow.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers