Duncan Green's Blog, page 199

January 9, 2014

Is ‘The Field’ an outdated and reactionary concept?

Advance warning – this blog is going dark for a couple of days to allow the cyberelves to give it a makeover. Back on Wednesday.

Ex Tales from the Hood blogger ‘J’ has an enjoyable tirade on the Why Dev blog against the use of the phrase ‘The Field’ in aidland – (as in ‘I’m going to

Exhibit A

the Field’):

‘There are few fixtures of the aid industry which hold as much mystique and show as much staying power as the concept and romance of “the field.” No other grail is so fervently sought among the bright-eyed, hopeful students and newbies as the field. The field, they believe, is where the action is, where they’re actually doing it, whatever “it” is. The harder or more exotic the field location, the better. Cubicles and conferences room in, say DC, are a necessary evil to be put up with until such time as one can escape to the field. There is no aspect of a young aid professional’s experience so frequently inflated or over-stated on resumes or at happy hour as time in the field. “Nearly one year” is always better than ten and a half months, and so on.

By the same token, there is no other trump card played with more authority and self-assurance, whether to put upstart newbs in their places or to establish one’s own silverback status, as years in the field. Years in Kabul or Huambo or San Salvador make you a hardcore, front-line badass who makes things happen. Years in Brussels or Singapore or DC makes you a pansy cubicle-farmer who goes to a lot of meetings and writes papers that no one in the field will ever read.’

As you can probably guess, J doesn’t approve:

‘It’s time to recognize that this is just plain incorrect. Make fun, if you will, of what goes on in well-lit UN conference rooms in Geneva, or at the global HQs in Washington, DC, Oxford, New York or Singapore (I certainly have and sometimes still do). But it’s important to understand that those things are not just “support” or “fundraising.” They may not be particularly Facebook- or edgy memoir-worthy, but the workshops, meetings, strategy sessions in the humanitarian capitals are every bit as much aid work as are running cholera clinics in Port-au-Prince, getting a truckload of non-food items across the Acekele border crossing, or being the accountability officer in Goma.

More specifically, to see the field as the place where aid really happens, as compared to everywhere else, is to also miss a basic reality that the decisions which truly make the most difference are not made in this alleged place called the field.

Beyond the basic, structural realities of the aid industry, there is also a deeper, darker problem perpetuated by the field versus everywhere else thinking. Our continued fixation with the field crystalizes residual, essentially ethnocentric notions about those who need help, and about those who do the helping. No matter how much lip service and maybe even real effort we devote to valuing all things “local”, to local capacity building, or local empowerment, to trying to break down the divide(s) between expats and non-expats, we re-cement the divide between “us” and “them” every time we refer to the place where aid supposedly happens as the field.’

Beyond the basic, structural realities of the aid industry, there is also a deeper, darker problem perpetuated by the field versus everywhere else thinking. Our continued fixation with the field crystalizes residual, essentially ethnocentric notions about those who need help, and about those who do the helping. No matter how much lip service and maybe even real effort we devote to valuing all things “local”, to local capacity building, or local empowerment, to trying to break down the divide(s) between expats and non-expats, we re-cement the divide between “us” and “them” every time we refer to the place where aid supposedly happens as the field.’

All good stuff, and I would even add that ‘The Field’ may contribute towards the aid business’ inability to think and work in urban settings, where most people now live.

But there are some powerful counterarguments against ditching the concept (no problem getting rid of the phrase, which I seldom hear around Oxfam, except in an ironic form):

Whether in developing or developed countries, it’s all too easy for people working in the aid business to inhabit a world of meetings, conferences, seminars and the rest. Sure lots of important stuff gets discussed and decided there, but the effect of never leaving the aidbiz bubble is, I think, significant and damaging. It affects the individual – I find if I go a few months without a ‘field trip’, I get stale, lose energy, start to recycle the same old messages. Visits to our programme to talk to staff, partners and communities invariably throw up new ideas, insights into power and politics, and inspiring people and initiatives. That’s why I (along with Robert Chambers) wish more aid organizations took immersion seriously.

But more importantly, it also affects the aid ‘project’. People in aidland may pay lip service to ‘the field’, but power all too often lies back in HQ. In the past, IMF and World Bank staff have been quite open with me that career progression requires them to be working back at HQ in Washington (has that changed at all? Hope so). I sometimes ask Oxfam colleagues ‘when was the last time you talked to a poor person who wasn’t serving you in some capacity?’ and get some pretty evasive responses. If the answer is years, rather than months, that must have some, probably negative, effect. Field trips are one small corrective, trying to ensure the thinking and priorities of those working in the aid business are guided by the lives and opinions of poor men and women – spending time with them definitely helps achieve that.

And tangentially related, here’s some good advice from Aid Leap on how to get a job in the aid sector (whether in a field, or somewhere more comfortable) [h/t Jamie Pett]

January 8, 2014

Obesity, Diabetes, Cancer: welcome to a new generation of ‘development issues’

I failed miserably to stop myself browsing my various feeds over the Christmas break (New Year’s resolution: ‘browse less, produce more’ – destined for failure). One theme that emerged was the rise of the ‘North in the South’ on health – what I call Cinderella Issues. Things like road traffic accidents, the illegal drug trade, smoking or alcohol that do huge (and growing) damage in developing countries, but are relegated to the margins of the development debate. If my New Year reading is anything to go by, that won’t last for long.

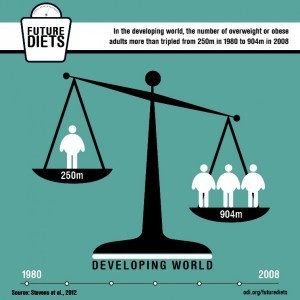

ODI kicked off with Future Diets, an excellent report on obesity by Sharada Keats and Steve Wiggins. Its top killer fact was that the number of obese/overweight people in developing countries (904 million) has more than tripled since 1980 and has now overtaken the number of malnourished (842 million, according to the FAO).

obese/overweight people in developing countries (904 million) has more than tripled since 1980 and has now overtaken the number of malnourished (842 million, according to the FAO).

Other key messages:

• Diets are changing wherever incomes are rising in the developing world, with a marked shift from cereals and tubers to meat, fats and sugar, as well as fruit and vegetables.

• While the forces of globalisation have led to a creeping homogenisation in diets, their continued variation suggests that there is still scope for policies that can influence the food choices that people make.

• There seems to be little will among public and leaders to take the determined action that is needed to influence future diets, but that may change in the face of the serious health implications. Combinations of moderate measures in education, prices and regulation may achieve far more than drastic action of any one type.

Meanwhile, the Economist ran a two page report and editorial on ‘the new drugs war’:

‘Pharmaceutical companies are widely regarded as vampires who exploit the sick and ignore the sufferings of the poor. These criticisms reached a crescendo more than a decade ago at the peak of the HIV plague. When South Africa’s government sought to legalise the import of cheap generic copies of patented AIDS drugs, pharmaceutical companies took it to court. The case earned the nickname “Big Pharma v Nelson Mandela”. It was a low point for the industry, which wisely backed down.

Now arguments over drugs pricing are rising again. Activists are suing to block the patenting in India of a new Hepatitis C drug that has just been approved by American regulators. Other skirmishes are breaking out, in countries from Brazil to Britain. But the main battlefield is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed trade deal between countries in Asia and the Americas. The parties have yet to reach agreement, partly because of the drug-pricing question.

The resurgence of conflict over drug pricing is the result not of a sudden emergency, but of broad, long-term changes. Rich countries want to slash health costs. In emerging markets, people are living longer and getting rich-country diseases. This is boosting demand for drugs for cancer, diabetes and other chronic ailments. In emerging markets, governments want to expand access to treatment, but drugs already account for a large share of health-care spending—44% and 43% in India and China respectively, compared with 12% in Britain and America. Meanwhile, a wave of innovation is producing expensive new treatments. In 2012 American regulators approved 39 drugs, the largest number since 1996. Cancer treatment, especially, is entering a new era.’

The resurgence of conflict over drug pricing is the result not of a sudden emergency, but of broad, long-term changes. Rich countries want to slash health costs. In emerging markets, people are living longer and getting rich-country diseases. This is boosting demand for drugs for cancer, diabetes and other chronic ailments. In emerging markets, governments want to expand access to treatment, but drugs already account for a large share of health-care spending—44% and 43% in India and China respectively, compared with 12% in Britain and America. Meanwhile, a wave of innovation is producing expensive new treatments. In 2012 American regulators approved 39 drugs, the largest number since 1996. Cancer treatment, especially, is entering a new era.’

This all poses a bit of a conundrum for NGOs and aid agencies. While (rightly) focussing on the outrage of 842 million hungry people in a world of plenty, should we also start to discuss public health issues such as obesity, which is no longer confined to the well off? If we shy away from doing so because it would muddy our message, we risk our description of life in the Global South being increasingly at odds with reality.

Similarly, what would happen in our work on health, if in addition to our work on the diseases of underdevelopment (malaria, HIV, polio) we acknowledge the increasing importance of those same old non-communicable diseases that we worry about for ourselves and our parents (cancer, heart disease, and beyond them, Alzheimers)? Would the loss of an exotic ‘other’ reduce public or media interest? And if so, should we care?

The positive aspect of the story is that governments, scientists and others in the North have lots of experience in these issues, and their advice and assistance would probably be a lot more useful to developing countries than banging on about stuff the rich world is currently not very good at (growth, jobs, smallscale agriculture etc).

Oh, and the Center for Global Development seems to be thinking along similar lines – a global anti-smoking drive tops its wishlist for 2014.

January 7, 2014

How America’s War on Poverty is changing

One of Oxfam’s better kept secrets is that we work in rich countries too. Here Minor Sinclair, who runs Oxfam’s US domestic programme, looks back on what has changed in 50 years of the ‘war on poverty’.

what has changed in 50 years of the ‘war on poverty’.

Fresh out of college, I jumped into the trenches of the War on Poverty – and have been there ever since. Fifty years ago today, I heard the call of President Johnson’s Declaration of the War on Poverty. In his State of the Union address, he asked us to summon the political will and the national resources to construct a Great Society. I joined up, and headed into the heart of poverty: coal country Appalachia and the black belt of the Deep South. And it was a good fight. I helped families living in tar paper shacks–some of whom were chopping up their floor boards as firewood to heat their homes—move into decent housing. I’ve seen ghetto kids become the first in their family to go to college and then go on to earn PhD’s. I’ve witnessed various programs transform people’s lives for their better: food and nutrition, early education, and health clinics.

As we mark the anniversary, we can see the results of anti-poverty programs which today serve upwards of 100 million people (eg, food stamps, VISTA, Medicare and Medicaid). Some skeptics may call the programs a failure, but they clearly haven’t seen the reality that I have. Nor have they seen the studies that show that without these programs, our poverty rate would be 31 percent instead of 16 percent (factoring in government transfers).

But if President Johnson were in office today, would he double-down on his original big bet? I doubt it. The nature of American poverty has changed, and so too must the policy response.

But if President Johnson were in office today, would he double-down on his original big bet? I doubt it. The nature of American poverty has changed, and so too must the policy response.

Johnson’s declaration was originally a war not just on poverty, but on “human poverty and unemployment.” He assumed, reasonably enough at the time, that moving poor people into paying jobs would lift them out of poverty.

Though our country saw its share of crises in the 1960s, we did enjoy a healthy economy. We saw steady growth, a strong manufacturing sector that provided middle-class jobs, and a decent minimum wage. Unions ensured that productivity gains were fairly distributed, and global competition was not a serious threat to US goods and services.

That’s not so easy when there are still 1-2 million fewer jobs today than in 2007.

Just as troubling, millions of low-wage jobs today are not a path out of poverty, but a trap within it. Nearly 40 percent of new jobs pay less than $14 an hour, according to a study by the National Employment Law Project.

While true that today’s economy has spit out 45 continuous months of job growth, the middle income jobs we lost in the Great Recession are now being replaced overwhelmingly with low wage jobs in services, retail and healthcare. It’s been a long trend in response to a globalized economy where our comparative advantage is seemingly reduced to fast food restaurants and temp agencies.

Today, President Johnson would need to go no further than a local strip mall (instead of Appalachia) to find the face of the poor and near poor. A third of all workers — roughly 59 million Americans–earn less than $14 an hour. Millions of people are working full-time—or even more–but still not earning enough to meet basic needs. For these people, it’s not a problem of motivation or social determinants or poor choices.

The problem is that while jobs are scarce, good jobs even scarcer, and people are forced to take what they can get even if it doesn’t pay the bills. By and large, these jobs aren’t held by high school kids living at home, but by the providers in the family.

large, these jobs aren’t held by high school kids living at home, but by the providers in the family.

Conservatives may be right that government transfer programs create disincentives—but not for individual’s receiving the aid. Instead, it’s the corporations that rely indirectly on government aid to help keep their low wage workers fed, housed, clothed and receiving health care. And the lower the wages, the more the government needs to step in to make up the difference. That’s why at least one conservative and deficit hawk is calling for a higher minimum wage.

As government anti-poverty programs have expanded, the floor for wages has collapsed. In real terms, the minimum wage has atrophied and pays, on average, only 1/3 of basic living expenses for a family of three. The few companies that have chosen the high road, showing you can pay a living wage and still make profits, haven’t shifted the corporate strategy of their brethren.

In 2014, the Democrats have announced that they’re ready to launch a battle to raise the minimum wage (an exceedingly helpful development if it’s a legislative effort and not a re-election tactic). If income inequality is the defining issue of our times, as President Obama says, I hope he is as successful in raising the bottom third as he is in reining in the top 1 percent (who raked in 95 percent of all income growth over the last five years).

An easy place to start would be for the President to change the rules in government procurement so that federal contractors can’t pay two million people sub-living wages. And it wouldn’t take another War on Poverty for the President to tap majority support from the general public and the working poor for a few policies that would make a big difference: improving access to paid family and medical leave, strengthening access to job training, making child-care more affordable, providing universal preschool.

Maybe addressing the poverty in wages is as idealistic as exploring the moon. But then, I’m still a true believer.

January 6, 2014

Do fragile states evolve like forests? Insights from complexity thinking

Oxfam’s engagement with physics-trained complexity enthusiast Jean Boulton is starting to generate some really interesting ideas. Jean has been helping us think through our work in fragile states – the big challenge for a lot of aid organizations over the next few years. Just before Christmas, she came in to tell us where her thinking has got to on the different kinds of fragility.

Drawing on Buzz Holling’s work researching the life-cycle of forests (I love this kind of disciplinary boundary-hopping), Jean looked at how complex ecological systems evolve over time, how diversity leads to resilience and how even natural systems can become rigid and brittle as they mature (see slide).

Whilst societies and nation states are subject to much more interference and influence from the wider world than is typical for your average forest, the work is important as it is based on observation, and cuts through the seemingly endless (and not always fruitful) discussions as to what complexity words and theoretical concepts actually mean.

Whilst societies and nation states are subject to much more interference and influence from the wider world than is typical for your average forest, the work is important as it is based on observation, and cuts through the seemingly endless (and not always fruitful) discussions as to what complexity words and theoretical concepts actually mean.

Turning Jean’s cycle into a much more boring table

Stage

Characteristics

Typical aid interventions

Countries that may look a bit like this

Birth

Emerging out of chaos; no fixed patterns; lots of growing (and vulnerable) shoots; power and control fluid

Be prepared for sectarian conflict and potential to fall back into chaos; nurture new shoots as they appear; support ‘structuring’ and emphasise the voice of civil society in influencing new institutions and in power and resource-sharing; recognise the potential for large corporations and others to exploit the power vacuum

South Sudan

Myanmar

Youth

Diversity; resilience; stable due to multiple relationships; power sharing

Act to strengthen capacity and livelihoods, maintain and expand economic and political diversity

?

Maturity

Efficient, but with falling diversity; relationships are reducing in number and becoming fixed; power static and concentrating in fewer hands

Support minorities and the less powerful; defend diversity; build livelihoods, education and strengthen civic capacity and voice to combat potential for concentration of power in hands of elites

Mali

Old Age

Locked in, rigid relationships, autocratic power

Support citizens movements in breaking/disrupting rigid power relationships.

OPTI

Potential for collapse

Brittle to the point of failure; power battles re-emerge

Protect ‘islands of effectiveness’, strengthen the voice of civil society, be cognizant of future potential economic or geo-political ‘tipping points’

Yemen

Chaos

Many structures collapsed, fast-changing dynamics and shifting power bases, great potential for violent conflict and taking advantage of power vacuum

Humanitarian response; supporting civil society and non-violence movements, ensure the voice of the citizen is heard in the international arena, continuing to envision post-conflict solutions

Syria

The reason I like this typology is both that it creates a dynamic sense of how fragility evolves over time, and the implications for would-be ‘change agents’, whether local or foreign. For example, when institutions are new and malleable and vulnerable, there is a lot more sense in devoting time to influencing them and protecting them from co-option by elites, than when they have become sclerotic and autocratic. It also creates a sense of ‘seizing the moment’ – institutions, once co-opted by the powerful, become much more resistant to ‘democratisation’; equally, when institutions collapse, the potential for various groups – ideological or economic – to exploit the power vacuum, is high.

I’d be interested in your additions/improvements, as I have a feeling I will be using this in the future.

January 5, 2014

HNY everyone, and here are the blog stats and most read posts for 2013

Welcome back, HNY etc. Hope you had a good break (if you took one). Personally I’m glad it’s over – tried to ski, knackered my knee, and meanwhile

Sorry Jacques, the cats have voted....

back home, our cats got trapped in a room and pissed all over my son’s final year university notes. For some reason they took particular exception to the post structuralists – Derrida now even more unreadable than before……

So with a sigh of relief, it’s back to the blog. In what is becoming my traditional way to ease back into work after the break, here are the questionable numbers of Google Analytics for 2013.

Total visitors in 2013: 282, 408 – these are supposedly all the different people who read the blog during the year, whether they click just once or visit every day (yes, there are such people). Or at least that’s the number of different IP addresses (so a mobile and a PC count as two people, even if the same individual is using them).

The numbers are much the same as 2012 (277,888 – see report here; 2011 upsum here), so it seems like the blog is now in some kind of steady state, with all the growth moving to twitter (followers doubling to about 15,000 during the year).

Where did they come from? See graph.

The daily traffic (see second graph) shows the usual weekly cycle (weekends are quieter). In case you’re wondering, the spike on January 22nd was for the best wonkwar of the year, on results and evidence. Time for a rematch?

The daily traffic (see second graph) shows the usual weekly cycle (weekends are quieter). In case you’re wondering, the spike on January 22nd was for the best wonkwar of the year, on results and evidence. Time for a rematch?

Most read posts? The top two are oldies but goodies from 2011, which occupy these slots for the third year running:

What Brits say v what they mean – handy de-coding device. This is the post that just keeps giving.

The world’s top 100 economies: 53 countries, 34 cities and 13 corporations

From this year’s posts, January’s wonkwar produced the top two slots:

The evidence debate continues: Chris Whitty and Stefan Dercon respond from DFID

The political implications of evidence-based approaches (aka start of this week’s wonkwar on the results agenda)

Below that it all gets a bit random:

Has Zimbabwe’s land reform actually been a success? A new book says yes.

OK, so how much should charity bosses be paid? Plus your chance to vote

What is a theory of change and how do we use it?

On inequality, let’s do the Palma (because the Gini is so last century)

How to get a job in development – an FP2P guide

And finally, back to the evidence debate:

So What do I take Away from The Great Evidence Debate? Final thoughts (for now)

Turning to 2014, the lessons for boosting traffic is try to be funny, chuck in the odd buzzfeed-style ‘listicle’ (a new and barbaric word), but don’t be scared of being geeky – on this blog at least, people appreciate wonkish debates rather than dumbing down or populism. Reassuring. Open to suggestions for good topics for wonkwars, by the way.

December 19, 2013

International Guidelines for Problem Solving (and see you in 2014)

What to post before I head off for the Christmas and New Year purgatory of family rows and overeating welcome holiday? Nick Pialek comes to the rescue with this outrageous set of deeply shocking national stereotypes, doing its rounds on the interwebs recently. Enjoy (and test your knowledge of flags). Back in January.

December 18, 2013

The state of the world’s older people: A smart new index on a rising development priority

I’ve been catching up on the backlog of books and papers that spread like an oil slick across my floor, and have come across a couple of gems (as well as some seasonal turkeys).

Top of the heap is the Global AgeWatch Index 2013, (c/o the indefatigable Sylvia Beales). It’s a smart attempt by HelpAge International to get some proper attention for one of the (many) Cinderella issues in development.

The Report is smartly produced, with good graphics and a powerful message.

The first and most obvious point is that populations are ageing fast – the maps show the proportion of over 60s – Green is 30%. By 2050, globally, there will be more people over 60 than there are under 15s. Life expectancy continues to grow. A disproportionate number of the old are women (100 for every 84 men in 2012), facing a whole set of extra stigmas around age and widowhood.

So who is ‘ageing well’ and who is not? The AgeWatch index combines income, health (including subjective wellbeing), education, employment and ‘enabling environment’ (social connection, physical safety, civil freedom, public transport) into a single index. The website allows you to create your own weighted index if you don’t like the HelpAge version.

So who is ‘ageing well’ and who is not? The AgeWatch index combines income, health (including subjective wellbeing), education, employment and ‘enabling environment’ (social connection, physical safety, civil freedom, public transport) into a single index. The website allows you to create your own weighted index if you don’t like the HelpAge version.

The resulting ranking of 91 countries is not that surprising – Sweden, Norway and Germany at the top; Pakistan, Tanzania and Afghanistan at the bottom.

What is more interesting is the comparison with a country’s overall Human Development Index (see graph). Relative to their general population, some countries (Ghana, Mauritius, Nepal and Vietnam) are ensuring a better life for their older people while others (Jordan, Pakistan, Tanzania, Russia, South Korea) are the pits. Among the richer countries, South Korea is a particular outlier – so not surprising perhaps that it has a particular problem of high suicide rates among older people.

Here’s some overall conclusions from the report:

‘The Index shows that good management of ageing is within reach of all governments. The rankings illustrate that limited resources need not be a barrier to countries providing for their older citizens, that a history of progressive social welfare policies makes a difference, and that it is never too soon to prepare for population ageing. A running thread is that action in the key areas of income security and health is essential.

The Index also highlights those lower-income countries that, regardless of their level of wealth, have invested in policies with positive impacts on ageing. In Sri Lanka (36), long-term investments in education and health have had a lifetime benefit for many of today’s older population. Bolivia (46), despite being one of the poorest countries, has had a progressive policy environment for older people for some time, with a National Plan on Ageing, free healthcare for older people, and a non-contributory universal pension.

Nepal (77) ranks 62 in the income security domain, having introduced a basic pension in 1995 for all over-70s without other pension income. Though limited in value and eligibility and with uneven coverage, this is an example of how a low-income country has chosen to make a start in addressing the old-age poverty challenge.’

Ageing populations will be increasingly central to the development debate, whether in terms of their rising absolute numbers, the struggle to put in place welfare systems that can cope, or because any attempt to ‘get to zero’ on absolute poverty is going to have to tackle the hard core of impoverished elderly people for whom market solutions are unlikely to work.

December 17, 2013

Bob Diamond v Dani Rodrik on Africa’s growth prospects

Two diametrically opposed views of Africa appeared in my e-intray on the same day this week. The Financial Times reported

Two diametrically opposed views of Africa appeared in my e-intray on the same day this week. The Financial Times reported that Bob Diamond, ex-boss of scandal-plagued Barclays Bank, had secured the preliminary support of several big institutional investors for Atlas Mara, his planned $250m cash shell, targeting the African banking sector. The FT gushed ‘Africa offers growth potential on a vast scale…. if there is one developing region of the world that still excites bankers confronted with stuttering faith in the traditional emerging markets of Asia and Latin America, it is Africa….. The demographics of the continent are breathtaking. Sub-Saharan Africa alone has a population of about 1bn, which, on many estimates, is set to double over the next three decades. The potential is obvious.’ Update: the ‘cash shell’ actually raised $325m, and starts trading on Friday.

that Bob Diamond, ex-boss of scandal-plagued Barclays Bank, had secured the preliminary support of several big institutional investors for Atlas Mara, his planned $250m cash shell, targeting the African banking sector. The FT gushed ‘Africa offers growth potential on a vast scale…. if there is one developing region of the world that still excites bankers confronted with stuttering faith in the traditional emerging markets of Asia and Latin America, it is Africa….. The demographics of the continent are breathtaking. Sub-Saharan Africa alone has a population of about 1bn, which, on many estimates, is set to double over the next three decades. The potential is obvious.’ Update: the ‘cash shell’ actually raised $325m, and starts trading on Friday.

Dani Rodrik on the other hand, had a much less optimistic piece on the Project Syndicate site (hope you’re signed up – it’s great). Rodrik accepts that Africa’s recent growth performance has been impressive.

‘Long viewed as an economic basket case, Sub-Saharan Africa is experiencing its best growth performance since the immediate post-independence years. Natural-resource windfalls have helped, but the good news extends beyond resource-rich countries. Countries such as Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Uganda, among others, have grown at East Asian rates since the mid-1990’s. And Africa’s business and political leaders are teeming with optimism about the continent’s future.’

But then he sets about systematically dampening the euphoria. Why? Because there are few signs of the structural changes needed for Africa to keep it going:

‘So far, growth has been driven by a combination of external resources (aid, debt relief, or commodity windfalls) and the removal of some of the worst policy distortions of the past. Domestic productivity has been given a boost by an increase in demand for domestic goods and services (mostly the latter) and more efficient use of resources. The trouble is that it is not clear from whence future productivity gains will come.

The underlying problem is the weakness of these economies’ structural transformation. East Asian countries grew rapidly by replicating, in a much shorter time frame, what today’s advanced countries did following the Industrial Revolution. They turned their farmers into manufacturing workers, diversified their economies, and exported a range of increasingly sophisticated goods.

Little of this process is taking place in Africa. As researchers at the African Center for Economic Transformation in Accra, Ghana, put it, the continent is “growing rapidly, transforming slowly.”

Safety net, but not springboard

In principle, the region’s potential for labor-intensive industrialization is great. But the aggregate numbers tell a worrying story. Fewer than 10% of African workers find jobs in manufacturing, and among those only a tiny fraction – as low as one-tenth – are employed in modern, formal firms with adequate technology. Distressingly, there has been very little improvement in this regard, despite high growth rates. In fact, Sub-Saharan Africa is less industrialized today than it was in the 1980’s.

As in all developing countries, farmers in Africa are flocking to the cities. And yet, as a recent study from the Groningen Growth and Development Center shows, rural migrants do not end up in modern manufacturing industries, as they did in East Asia, but in services such as retail trade and distribution. Though such services have higher productivity than much of agriculture, they are not technologically dynamic in Africa and have been falling behind the world frontier.

Consider Rwanda, a much-heralded success story where GDP has increased by a whopping 9.6% per year, on average, since 1995 (with per capita incomes rising at an annual rate of 5.2%). Xinshen Diao of the International Food Policy Research Institute has shown that this growth was led by non-tradable services, in particular construction, transport, and hotels and restaurants. The public sector dominates investment, and the bulk of public investment is financed by foreign grants. Foreign aid has caused the real exchange rate to appreciate, compounding the difficulties faced by manufacturing and other tradables.

None of this is to dismiss Rwanda’s progress in reducing poverty, which reflects reforms in health, education, and the general policy environment. Without question, these improvements have raised the country’s potential income. But improved governance and human capital do not necessarily translate into economic dynamism. What Rwanda and other African countries lack are the modern, tradable industries that can turn the potential into reality by acting as the domestic engine of productivity growth.

The African economic landscape’s dominant feature – an informal sector comprising microenterprises, household production, and unofficial activities – is absorbing the growing urban labor force and acting as a social safety net. But the evidence suggests that it cannot provide the missing productive dynamism. Studies show that very few microenterprises grow beyond informality, just as the bulk of successful established firms do not start out as small, informal enterprises.

Optimists say that the good news about African structural transformation has not yet shown up in macroeconomic data. They may well be right. But if they are wrong, Africa may confront some serious difficulties in the decades ahead.

Two decades of economic expansion in Sub-Saharan Africa have raised a young population’s expectations of good jobs without greatly expanding

They want jobs

the capacity to deliver them. These are the conditions that make social protest and political instability likely. Economic planning based on simple extrapolations of recent growth will exacerbate the discrepancy. Instead, African political leaders may have to manage expectations downward, while working to increase the rate of structural transformation and social inclusion.’

The different conclusions largely follow from the different motives: Bob Diamond is aiming to get rich (along with his investor mates) from Africa and in the short term, whereas Dani Rodrik is worrying about the fate of Africans themselves (especially poor ones) in the long term. Shame the two seem to be so delinked. Needless to say, I’m with Dani, but I wish he had a more upbeat story to tell.

And the Daily Maverick follows a similar pattern, kindly offering two 2013 Africa reviews: one for pessimists, the other for optimists. Take your pick. (h/t Martin Plaut)

December 16, 2013

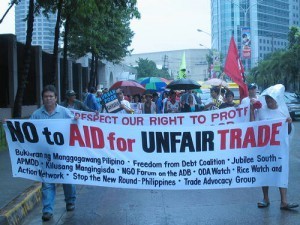

DfID gets a red light on aid for trade: how will it respond?

Oxfam aid wonk Nicola McIvor explores a highly critical report on one of DfID’s flagship programmes

The problem with being committed to independent evaluation and transparency is that you risk being beaten up in public when things go wrong. Oxfam is accustomed to having our own evaluations quoted against us, which is exactly what happened to DFID last week, when the UK’s aid watchdog, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI), gave its first overall ‘red’ traffic light rating to DfID’s Trade Development Work in Southern Africa.

The programme was intended to improve Southern Africa’s trade performance and competitiveness, but was marked red because ICAI uncovered serious “deficiencies in governance, financial management, procurement, value for money and transparency of spending” in TradeMark Southern Africa (TMSA).

The findings in the report are damning:

The programme merely assumes that it will benefit the poor, but has not linked programme activities to poor people, nor has it mitigated negative impacts, such as increasing food price volatility and unemployment in certain sectors.

TMSA misreports its performance and DfID does not check those reports properly e.g. TMSA’s summary management report claims that 83% of targets have been met, whereas ICAI looked at detailed project reports and found it met only 21%;

£67 million of TMSA’s budget was placed in a trust account to attract private finance for the North-South Corridor but has not been spent nor attracted additional funds;

Excessively high salaries for TMSA staff, with senior TMSA managers receiving higher salaries than UN directors and the Head of TMSA trousering well over £200k per annum;

A private company is managing a £30.6 million DfID programme without any formal contract with either the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) or DfID;

TMSA will have made little impact on trade when DfID’s funding ends in 2014.

Aid sceptics will be quick to seize this as an example of ‘corruption’ or ‘waste’, but if aid is to be well-spent this type of transparency is vital and we can’t be reticent about recognising and responding to failure. The more interesting questions arising are: how did the Secretary of State for International Development and DfID respond, and what are the implications for DfID’s future aid for trade?

Aid sceptics will be quick to seize this as an example of ‘corruption’ or ‘waste’, but if aid is to be well-spent this type of transparency is vital and we can’t be reticent about recognising and responding to failure. The more interesting questions arising are: how did the Secretary of State for International Development and DfID respond, and what are the implications for DfID’s future aid for trade?

So how did Justine Greening and DfID deal with this?

The ICAI team were so concerned with what they saw that they alerted DfID back in May shortly after their fieldwork. DfID not only verified a number of ICAI’s concerns but also discovered payments amounting to £80,000 made to the Government of Zimbabwe – in contravention of UK Government policy. Ahead of the publication of ICAI’s report, Secretary of State Justine Greening announced the closure of TMSA.

Greening and DfID’s Permanent Secretary Mark Lowcock were called to give an account of DfID’s actions before The International Development Select Committee. This gave Greening the opportunity to talk about something she has often joked that she does best…auditing. Greening highlighted how this Government has strengthened DfID’s programme and financial management procedures, and has placed a strong emphasis on value for money.

Greening and Lowcock were adamant that TMSA was a case of ‘mismanagement’ as opposed to ‘corruption’ or ‘fraud’, but the case raises much deeper questions about DFID’s approach to aid. Greening had little to say on one of the key points highlighted in ICAI’s report that “neither DfID nor TMSA is doing enough to understand the potential positive impacts or to mitigate against the potential negative impacts on the poor”. Yet the 2002 Development Act clearly states that development assistance must contribute to poverty reduction.

What are the implications for DfID’s aid for trade?

This Government has made trade central to the UK’s approach to development arguing that “trade is the most important driver of growth” and that growth will lead to more jobs, higher incomes and a stronger tax base – essential for poverty reduction and ending aid dependency. However, it is clear that in this case, unjustified assumptions were made about how the benefits of trade integration would trickle down and negative impacts were not considered. This tells a cautionary tale about the relentless pursuit of growth and confirms that not all investment is good investment.

growth will lead to more jobs, higher incomes and a stronger tax base – essential for poverty reduction and ending aid dependency. However, it is clear that in this case, unjustified assumptions were made about how the benefits of trade integration would trickle down and negative impacts were not considered. This tells a cautionary tale about the relentless pursuit of growth and confirms that not all investment is good investment.

With trade high on DfID’s agenda how will the findings from the TMSA case influence future trade programmes and the aid for trade agenda? What steps will DfID take to more seriously consider impacts on the poor rather than merely assuming such benefits will accrue?

Greening recently visited Tanzania with a high-level business delegation and announced a new fund to improve trade competitiveness in East Africa, as part of TradeMark East Africa (TMEA) – an initiative that has received a lot of praise. The report notes that TMEA is structured differently to TMSA, enabling it to be more independent and not donor driven, but how will DfID ensure that this time really is different? What steps has it taken to analyse the impact of this initiative on the poor from the outset and throughout implementation? What analysis has DfID done on the use of trade and poverty linkages to improve learning and make sure that other programmes don’t make the same mistakes?

It is also concerning that £67 million of UK aid has been sitting in a trust fund instead of being used to deliver real results for the poor. This use of trust funds has become increasingly common in development among a range of actors including UN agencies, bilateral donors like DfID and development banks such as the European Investment Bank and the World Bank. Despite DfID’s leadership in aid transparency, it is not clear from DfID’s website how much UK taxpayers’ money is currently in trust funds.

Finally, this is not the first time that ICAI has voiced concern over DfID’s management and capacity for oversight. ICAI’s report on DfID’s use of contractors also flagged problems with DfID’s management of programmes’ lifecycles, DfID staff turnover and ability to capture learning. Whilst there are of course pros and cons for a more arms length approach, the key to a successful programme is ensuring a focus on what impact it will have on the poorest and taking action to mitigate any negative impact. ICAI recommend that as a prerequisite of any future trade development programme, DfID should undertake comprehensive analysis of the impact on poor people.

This story has, in many ways, shown the system working as it should: ICAI is proving its value; the Development Select Committee quickly supported ICAI; and the initial response from DfID has been swift, decisive and open. But DfID must now address the wider questions this report raises.

December 15, 2013

Poor countries are losing $1 trillion a year to illicit capital flows – 7 times the volume of aid

I was surprised not to see more coverage of last week’s hard-hitting report from the Global Financial Integrity watchdog. Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2002-2011 has a whole bunch of killer facts about the escalating haemorrhage of wealth from poor countries. Here are some highlights. My additions in square brackets/italics:

Developing Countries: 2002-2011 has a whole bunch of killer facts about the escalating haemorrhage of wealth from poor countries. Here are some highlights. My additions in square brackets/italics:

“We estimate that illicit financial outflows from the developing world totalled a staggering US$946.7 billion in 2011, with cumulative illicit financial outflows over the decade between 2002 and 2011 of US$5.9 trillion. [By way of comparison, total global aid in 2011 was $134m – 14% of illicit flows - and has fallen since, even as illicit flows keep booming. Want that as a soundbite? ‘For every dollar of aid, the South loses $7 in illicit outflows; developing countries are losing $2.6 bn a day/$108m per hour/$2m per minute/$30,000 per second’.]

This gives further evidence to the notion that illicit financial flows are the most devastating economic issue impacting the global South. Large as these numbers are, perhaps the most distressing take-away from the study is just how fast illicit financial flows are growing. Adjusted for inflation, illicit financial flows out of developing countries increased by an average of more than 10 percent per year over the decade. Left unabated, one can only expect these numbers to continue an upward trend.

Heat map of illicit flows by country, % of GDP

The pattern of illicit outflows, trend rate of growth, and impact in terms of GDP all vary significantly among the five regions. Asia accounts for 39.6 percent of total illicit outflows from developing countries, the largest share of illicit flows among the regions, and six of the top 15 exporters of illicit capital are Asian countries (China, Malaysia, India, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines). Developing Europe (21.5 percent) and the Western Hemisphere (19.6 percent) contribute almost equally to total illicit outflows.

While outflows from Europe are mainly driven by Russia, those from the Western Hemisphere are driven by Mexico and Brazil. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region accounts for 11.2 percent of total outflows on average. MENA’s share increased significantly from just 3 percent of total outflows in 2002, reaching a peak of 18.5 percent in 2009, before falling to 12 percent in 2011. In comparison, Africa’s share increased from just 3.9 percent in 2002, reaching a peak of 11.1 percent just before the Great Recession set in (2007), before declining to 7 percent in 2011, roughly on par with its average of 7.7 percent over the decade.

The volume of total outflows as a share of developing countries’ GDP increased from 4.0 percent in 2002 to 4.6 percent in 2005. Since then, barring a few upticks, illicit outflows have generally been on a declining trend relative to GDP, and were 3.7 percent in 2011. While Africa has the smallest nominal share of regional illicit outflows (7.7 percent) over the period studied, it has the highest average illicit outflows to GDP ratio (5.7 percent), suggesting that the loss of capital has an outsized impact on the continent. [Got that? The poorest continent has the biggest problem of illicit outflows]

The MENA region registered the fastest trend rate of growth in illicit outflows over the period studied (31.5 percent per annum) followed by Africa (20.2 percent), developing Europe (13.6 percent), Asia (7.5 percent), and Latin America (3.1 percent). The sharply faster rate of growth in illicit outflows from the MENA region is probably related to the rise in oil prices.

The MENA region registered the fastest trend rate of growth in illicit outflows over the period studied (31.5 percent per annum) followed by Africa (20.2 percent), developing Europe (13.6 percent), Asia (7.5 percent), and Latin America (3.1 percent). The sharply faster rate of growth in illicit outflows from the MENA region is probably related to the rise in oil prices.

Trade misinvoicing comprises the major portion of illicit flows (roughly 80 percent on average). Balance of payments leakages fluctuate considerably and have generally trended upwards from just 14.2 percent of total outflows in 2002 to 19.4 percent in 2011.

[Statistical analysis shows that] An increase in corruption increases trade misinvoicing while capital account openness leads to greater export misinvoicing in both directions if openness is not accompanied by stronger governance. In fact, as the experience of developed countries shows, greater openness and liberalization in an environment of weak regulatory oversight can actually generate more illicit flows.’ [So by making it easier for people to shift $, liberalization risks making things worse not better, which fits with the rapid rise in volumes of illicit flows]

Maybe one reason for the lack of coverage is that the report is a bit, errm, boring. It fizzles out just when advocacy should have come in to follow up the number crunching, and the format is very old school, with none of the razamatazz required to get a buzz going – infographics, animations, short video presentations etc. But the content is excellent, so could someone out there give the data geeks a hand with the advocacy and comms next time?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers