Duncan Green's Blog, page 196

February 17, 2014

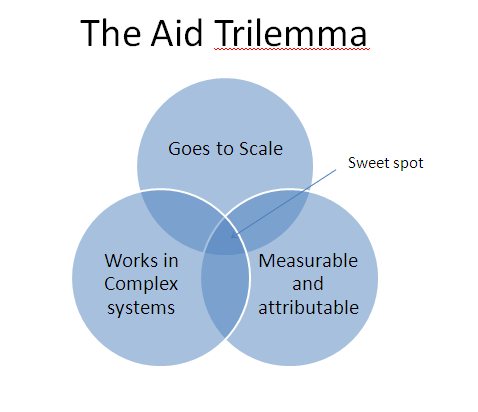

The Aid trilemma: are complexity, scale and measurability mutually incompatible?

I’ve been reflecting on Owen Barder’s recent post on the tensions for aid agencies between wanting to go to scale, and acknowledging that lasting development solutions have to emerge from discussions among local actors, based on local context.

Seems to me we have something of an aid trilemma here – I would add in attribution to the mix as a third element. You can have two out of three of the following:

Able to go to scale (reaching millions of people, rather than a couple of hundred)

Compatible with complex systems (inherently unpredictable, discontinuous, shaped by local context)

Measurable and attributable (being able to say change happened and that it was due to a given intervention or action)

Two out of three gives you three different permutations:

Two out of three gives you three different permutations:

Interventions in complex systems that go to scale, but whose impact is largely unattributable:

Working on the ‘enabling environment’ (rule of law, strengthening civil society, access to finance)

Improving quality of essential services (see Lant Pritchett)

Problem-driven iterative adaptation (Matt Andrews)

Convening and brokering relationships/acting as a catalyst/other kinds of leverage rather than trying to do stuff on your own

Interventions that go to scale and are clearly attributable, but are not suited to complex systems

Bednets, food aid and other straightforward(ish) service delivery

Essential Services – quantity (getting kids into school) rather than quality (teaching them anything – Lant Pritchett again)

Simple replicable institutions (football/soccer, Owen thinks postal services)

Interventions in complex systems that are clearly attributable, but cannot go to scale

Locally grounded work on governance, accountability etc

Using process tracing and other ways to measure the impact of ‘n=1’ interventions

The question then arises, what (if anything) lies in the sweet spot, namely interventions that manage simultaneously to go to scale, are clearly attributable, and respect the nature of complex systems? Owen reckons a number of CGD pet schemes, such as Cash on Delivery, tick all three boxes, but I’m most dubious on the attribution corner of the trilemma. A government reduces maternal mortality, you reward them with $x thousand dollars per life saved, but how do you know that the offer of that money had anything to do with the outcome? Social franchising might work – a core ‘project in a box’ that allows for plenty of variation according to local circumstance, like Savings for Change. Other suggestions?

What do you think – is the trilemma idea worth pursuing? I’m planning to think this through further with UNDP, Owen and others – keep you posted.

February 16, 2014

Government to Government trade – a new development issue, but is it threat or opportunity?

I have a love-hate relationship with The Economist – hate its lazy, evidence-free, anti-state, privatizing ‘priors’, but love the range of  thought-provoking new angles, and its coverage of development. In general, the further it gets from economics, the more I like it.

thought-provoking new angles, and its coverage of development. In general, the further it gets from economics, the more I like it.

Usually I just tweet links to the good stuff, but last week’s piece on ‘government to government trade’ deserves special attention. The article describes a boom in such G2G exchanges:

‘A Norwegian government agency managing Algeria’s sovereign-wealth fund; German police overseeing security in the streets of Mumbai; and Dubai playing the role of the courthouse of the Middle East.’

The trade is growing as ‘it is a natural extension of the trend for governments to pinch policies from each other. “Policymaking now routinely occurs in comparative terms,” says Jamie Peck of the University of British Columbia, who refers to G2G advice as “fast policy”. Since the late 1990s Mexico’s pioneering policy to make cash benefits for poor families conditional on things like getting children vaccinated and sending them to school has been copied by almost 50 other countries.

When China realised in the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics that it needed to improve its air-safety regulations, it could just have looked around for the best examples and come up with its own version. Instead it asked America’s Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to write a new rule book and to train Chinese pilots. The FAA now has full-time offices in Beijing and Shanghai. Trinidad and Tobago, which decided in 2010 to computerise its register of motor vehicles, bought a system from the government of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.

Dispute resolution is a particularly lively part of the G2G market. Britain will soon play host to an arbitration court for Saudi Arabian disputes, helping to allay investors’ concerns about the Gulf state’s legal system. A growing number of countries, most with a history of British common law, want to become the preferred jurisdiction in their region or for a particular type of case. In 2011 Dubai’s International Financial Centre threw open its courts to disputes from any country, provided the parties agreed to be bound by its decisions. Courts in the British Virgin Islands hear a good share of all disputes involving international joint ventures.

The most radical form of G2G is the delegation agreement: the government of one country providing a public service in another, which in effect cedes part of its sovereignty. In 2003 the government of the Solomon Islands, concerned at rising violence and falling tax revenues caused by corruption, asked the Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI) to take over law enforcement. RAMSI brought in more than 2,000 soldiers and other personnel and succeeded in establishing the rule of law.

Really?

Critics fret about accountability and democratic legitimacy. The 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, endorsed by governments and aid agencies, made much of the need for developing countries to design their own development strategies. And providers open themselves to reputational risk. British police, for instance, have trained Bahraini ones. A heavy-handed crackdown by local forces during the Arab spring reflected badly on their foreign teachers.

Local governments, however, both have greater incentives to trade and face fewer barriers. Rapid urbanisation creates urgent practical problems for cities: in 2009 the urban population in developing countries stood at 2.5 billion, a number expected to double by 2050. And, unlike countries, cities are not hobbled by issues of sovereignty.’

If this trend is genuine, there are both threats and opportunities for those interested in rights-based development. The threats are pretty obvious – the spread of bad ideas, the dilution of local accountability, the encroachment on national sovereignty, the Bahrain police thing.

But there are plenty of opportunities too. Involvement of European and North American governments provides a new advocacy target, targeting them to promote social and environmental safeguards, transparency, accountability etc in their G2G work (could start with Bahrain…..).

INGOs and other aid organizations could also get more proactive and push the right kind of G2G, linking up developing country governments, whether national or municipal, with positive experiences in other countries on everything from social protection to reducing road traffic accidents. I have a feeling this kind of signposting and linking is going to become an increasingly important part of our work. Bring on the exchange visits to see the speed bumps of London…..

The underlying assumptions of the Economist piece envisage a technocrats’ dreamland of exchanges of ideas and blueprints between countries, leading to progress and stronger institutions. Trouble is, the people who actually study institutions ( the ‘thinking and working politically’ crowd, Matt Andrews etc) say this isn’t how it works at all – instead, local problems lead at best to ‘hybrid’ solutions in which lessons from elsewhere are adapted to ‘go with the grain’ of local tradition. That would suggest this supposed wave isn’t going anywhere fast. Wonder who will be proved right?

February 13, 2014

How to bridge the Valley of Death that separates complexity/systems thinkers from decision makers?

Sometimes new ideas arrive like a bolt from the blue. More often they emerge through a series of conversations, reading and thinking. An element of repetition may be necessary, provided you talk to different kinds of people about the same issue (rather than having the same meeting with the same people over and over again – we call that strategic planning).

An element of repetition may be necessary, provided you talk to different kinds of people about the same issue (rather than having the same meeting with the same people over and over again – we call that strategic planning).

So earlier this week I ended up in a room full of scientists and research council funders, organized by UKCDS, discussing a topic dear to my heart and blog – complexity and systems thinking. The topic was how research funding can channel complexity science to improve understanding and practice in the aid/development sector. The conversation reinforced a few points, but added a few new angles.

First was the sheer difficulty of bridging the gap between complexity thinkers in academia and busy aid activists, whether in government or NGOs. One contributor talked of a ‘valley of death’ that separates pure science from ‘operationalisation’ – using the new ideas to actually do stuff.

That gulf is further deepened by an academic system that works in disciplinary siloes that seem remarkably resistant to attempts to get them to cross fertilize – even waving research funding chequebooks often fails to get economists, ecologists, sociologists etc to really work together.

I came away convinced that we need to understand these institutional barriers better, even if that does entail some navel gazing. Is it about language (economists and sociologists can’t understand each other), incentives (this won’t get me published in a peer-reviewed journal) or broader frameworks for understanding the world? It reminded me of a recent conversation at the Thinking and Working Politically seminar – unless we can understand why institutions find this so hard, and what can be done about it, we’ll probably be wasting our time.

I came away convinced that we need to understand these institutional barriers better, even if that does entail some navel gazing. Is it about language (economists and sociologists can’t understand each other), incentives (this won’t get me published in a peer-reviewed journal) or broader frameworks for understanding the world? It reminded me of a recent conversation at the Thinking and Working Politically seminar – unless we can understand why institutions find this so hard, and what can be done about it, we’ll probably be wasting our time.

Some suggestions for where to start: find out what research has been done on bridging similar gulfs, e.g. between pure science and industry. Study the role of individual ‘boundary crossers’, like our own Jean Boulton – is spotting and supporting the mavericks a quicker route to cross-disciplinarity than urging inertia-bound institutions and faculties to collaborate?

Second was a new (for me) way of selling complexity thinking to our political masters. This is all about making decisions in situations that are uncertain and volatile. What is ‘enough evidence to make a decision’, complete with feedback loops to detect success or failure, and adapt accordingly?

Otherwise, I banged on (as usual) about the tensions between systems thinking and the results/value for money agenda and linear planning tools; the importance of understanding the circumstances in which research influences policy; the power of case studies in showing that complexity thinking can lead to results and the barriers posed for activists by jargon and the geeks’ love of, errm, complexity. For me, the best way to discuss these issues in Oxfam is to avoid the C word altogether and ask a variant of ‘How do you plan when you don’t know what is going to happen?’ or ‘how do you campaign on a problem when you don’t know the solution?’

There was particular interest in the case study question, and how to improve our ability to capture the messy reality of change process, rather than construct an airbrushed, linear, quasi-mythical story. That means investing in real time accompaniment, and improving our ability to research and narrate how change happens.

The good news is that the research funders seem to understand the importance of it, and in many cases are already invested in supporting systems thinking. The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) seems to have done most in the area (see here for details), but has not so far tried to link it to international development. Time for some cross-fertilization, I reckon.

February 12, 2014

Why conflicts can also be opportunities for (positive) change for women

The November edition of Oxfamâs Gender and Development Journal focused on conflict and violence. Here one of the contributors, Julie Arostegui, a human rights and gender specialist, discusses Gender, conflict, and peace-building: how conflict can catalyse positive change for women.

rights and gender specialist, discusses Gender, conflict, and peace-building: how conflict can catalyse positive change for women.

In my years as a human rights and womenâs rights advocate, I have witnessed the resilience of women who have lived through horrific situations including sexual violence, domestic violence, human trafficking and other abuses. But I have also noted the opportunities that struggle and conflict have created for women to find their voices, advocate for new policy, and at least begin to change societies.

In recent decades, the nature of war has changed dramatically. Civilians, and especially women and girls, are targeted with extreme violence. It is commonly said that womenâs bodies have now become battlefields. At the same time, women have played major roles as peacemakers and peace builders. Despite the devastating impacts of conflict on themselves, their families and their communities, women throughout the world have used post-conflict periods to reshape societies, rewrite the rules and advance womenâs rights.

In doing so, they have drawn on an international framework on women, peace and security that includes United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, international human rights law and other international and regional agreements and commitments to involving women in post-conflict peace building.

When I visited Rwanda in 2012 to talk with local groups, I was struck by the beauty of the country and the strength of its women, and how they have healed and found their voices since the 1994 genocide. After the genocide, so many women were left as widows that they began to establish groups and organisations to come together to find a way forward and avoid isolation.

At the same time women such as Mary Balikungeri (left), Director and Founder of the Rwanda Womenâs Network (RWN), who had been living in the diaspora due to years of ethnic conflict, came back eager to help rebuild their country.  On her return, Mary first worked with orphaned street children, before founding the RWN in 1997.

in the diaspora due to years of ethnic conflict, came back eager to help rebuild their country. Â On her return, Mary first worked with orphaned street children, before founding the RWN in 1997.

RWN focuses on health care, socio-economic empowerment, education and awareness, and networking and advocacy for women. It provides dialogue spaces for local women to connect with policymakers, and has established âPolyclinics of Hopeâ, which adopt a holistic approach to the plight of women survivors of sexual and gender-based violence by addressing their health, psychosocial, shelter and socio-economic needs

According to Mary, the power of women in Rwanda has come from all of them – both those returning from the diaspora and those who had remained in Rwanda â working together as survivors.

In the years since the genocide, Rwandan women have lobbied for the repeal of discriminatory legislation and mobilised to ensure that the 2003 constitution included womenâs rights. Rwanda now has the Parliament with the highest percentage of women in the world, at 56% in 2013. The Government of Rwanda has also recognised the importance of investing in women both as a strategy to achieve economic development and to empower women.

Uganda, which suffered a dictatorial regime under Idi Amin in the 1970s followed by a five-year civil war, then a horrendous 20-year uprising in the north led by Joseph Kony and the Lordâs Resistance Army, has served as a role model for the region on inclusion and womenâs rights. Ugandan women played a strong role in advocating for peace and made sure that the 2006 peace agreements included provisions on womenâs rights. They also worked for an inclusive, human rights based constitution passed in 1995 which has been the cornerstone for advocacy on womenâs rights.

In Uganda, as in many other countries, traditional and cultural practices and norms have allowed discrimination against women to be  perpetuated. Womenâs groups have been instrumental in working with cultural and religious leaders, who are the gateways to their communities and often the arbitrators of disputes, on linking human rights concepts to cultural practices in order to raise community awareness of womenâs rights issues and change perceptions about gender roles.

perpetuated. Womenâs groups have been instrumental in working with cultural and religious leaders, who are the gateways to their communities and often the arbitrators of disputes, on linking human rights concepts to cultural practices in order to raise community awareness of womenâs rights issues and change perceptions about gender roles.

For instance, in Northern Uganda, FIDA Uganda, the Association of Women Lawyers, has been working with local elders of the Ker Kwaro Acholi (KKA) to address sexual and gender-based violence in their communities, training chiefs in the mediation of disputes and supporting the creation of gender principles to assist them in handling cases of gender-based violence and sensitize communities on gender issues. Linking local practices and human rights norms, the gender principles provide recommendations on the definition of marriage, regulation of polygamy, sexual rights, property rights, divorce and separation, violence against women and inheritance and property rights.

Meanwhile in South Sudan, although womenâs structures and networks are still in their initial stages, women advocates, with the help of international donors and international NGOs, have been working to advance the roles of women and participate in the building of the legal and policy framework of their country. Although the situation in South Sudan is at this moment quite dire, it is my fervent hope that peace will come again soon and that women will be able to continue on their path.

The evolution of the international framework around women, peace and security, the experiences of women in Rwanda and Uganda and the recent processes in South Sudan show the power that womenâs voices can have. Part of womenâs empowerment in these countries has come with the education, advocacy and organisational skills that they developed as a result of conflict. Periods of turmoil have frequently offered the opportunity for change that women need. They represent new opportunity and are a voice for peace.

As we begin 2014 with the hope of the worldâs newest country, South Sudan, being shattered by ethnic conflict, continuing violence in countries such as the Central African Republic and Syria and renewed violence in Iraq, just to name a few, it is more important than ever to look at the opportunities that conflict can bring for change and continue to amplify the voices for peace.

February 11, 2014

Fighting inequality one city at a time: reclaiming public water and electricity in Delhi

Thereâs a political earthquake going on in Delhi right now. Biraj Swain (Exfam India, now campaigning and researching on water)  looks at its immediate impact on poor peopleâs access to water and electricity.

looks at its immediate impact on poor peopleâs access to water and electricity.

Last month marked the first month in office of the anti-corruption movement turned political party, the Aam Admi âCommon Manâ Party government in Delhi, India. Two days into office, they had made âlifeline waterâ free for each household (calculated at 140 litres per capita per day, 20 kilolitres per month). Citing the estimated 24.8% unconnected and un-metered households in Delhi, the corporate media has slammed the decision as misplaced populism since it will only benefit the already-connected rich and result in wastage.

However, by making lifeline water free across class and caste, from the super-elite Lutyensâ zone to the ultra-poor slums, the government established the right to water in principle and practise. This is aimed to stop the poor from being priced out and keep municipal budgets under control, just like Manila-Philippines, Grenoble-France and Argentina etc. And by coupling the 20 kilolitres free water with steep hikes above that threshold, they are tackling wastage. Meanwhile, they are also expanding the piped water network, to make potable water accessible to all.

The government has also come down heavily on corrupt officials of the utility and the water-tanker mafia. It is common knowledge that utilities across the world are among the most corrupt public bodies and their technical nature makes their operations inscrutable to many. So while keeping the utility in the public domain, making it efficient, accountable and pro-poor is also part of the agenda.

Little wonder that the current Delhi Chief Minister, Arvind Kejriwal, is a trained engineer who has already led a successful campaign against the privatisation of Delhiâs water utility in 2005. Using Indiaâs transparency law, he unearthed 9000 pages of proposed reform plans. From overly generous concession contracts to uber-expensive management consultants and exponential tariff hikes, the plans had the potential to trigger a water-war. Debt financed water and sanitation has already resulted in many cities in South Asia defaulting and end-users burdened with expensive loans.

Unlike water, power distribution is already privatised. Thanks to steep domestic tariff hikes, Delhiâs electricity is one of the most expensive in the country. The power supply is managed by the two biggest corporate houses of India, the Tata and the Ambani groups.

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, Photo AP/Guardian

As with water, the new Delhi government has unleashed a slew of measures such as sharp tariff cuts (up to 50%) in the first 400 unitsâ of domestic usage and incremental increases above that.

Last month also saw the power regulator (long since captured by the energy companies) locking horns with the government and hiking electricity tariffs by 8% unilaterally on the back of outage threats from private companies. This is standard corporate bullying 101 in essential sectors like water and electricity.

But the Delhi government is fighting back. By asking the countryâs statutory auditor, the Comptroller and Auditor General, to audit the books of private power distribution companies, the government is re-writing the rules of engagement in public-private partnership (PPP). In an era where PPP is touted as the silver bullet for all essential services challenges, the state is often forced to retreat. The chief minister is resisting by re-drawing the boundaries of the state itself, re-introducing citizen-state oversight over utilities and their functioning.

Whether this experiment will succeed in bringing down power bills sustainably while keeping the access equitable, is yet to be seen. But it has already prompted unprecedented public debates and education on the workings of the power and water sectors, hitherto inaccessible to the general public. We can be agnostic about whether public or private provision works best, but there can be no debate on greater accountability and transparency of utilities and their operations.

The next step is to rewrite the remit of utility regulators and bring in greater transparency into their selection process. Stopping the regulators from becoming a dumping ground for unwanted bureaucrats or retired judges with serious conflicts of interest is essential if these regulators are to bark and bite in the public interest, based on the principles of equity and efficiency.

One month is a very short time in a five-year electoral mandate. For a public action movement re-invented as political party hardly a year ago, it is even shorter. But if these experiments of greater transparency, lifeline allocations for all, tariff rationalisation and  increased public scrutiny succeed, then it will be another victory in the glorious tradition of Cochabamba-Bolivia, Recife and Porto Alegre-Brazil etc.

increased public scrutiny succeed, then it will be another victory in the glorious tradition of Cochabamba-Bolivia, Recife and Porto Alegre-Brazil etc.

Agitational politics which has been the hallmark of peopleâs water movements across the world is also the hallmark of this government. The Delhi government is scripting a story with greater public engagement which would be very difficult to roll back. And public-public partnership could be a real counter-narrative, in India, South Asia and globally.

Biraj Swain is a member of the Right to Water Coalition and has just finished a study on small townsâ water sanitation challenges in South Asia and East Africa (under publication). She has led a meta-analysis of Asian Development Bank lending and its impact on water sanitation access to the poor. She can be reached at biraj_swain@hotmail.com.

Â

February 10, 2014

How to build accountability in fragile states? Some lessons (and 2 new jobs) from an innovative governance programme.

One of my favourite Oxfam programmes is called (rather arcanely) âWithin and Without the Stateâ. It is trying to build civil society and  good governance in some pretty unpromising environments â Yemen, South Sudan, Afghanistan and OPTI (Occupied Palestinian Territory and Israel).

good governance in some pretty unpromising environments â Yemen, South Sudan, Afghanistan and OPTI (Occupied Palestinian Territory and Israel).

Itâs currently advertising two new jobs (one on learning and communications, the other a programme coordinator), if you’re interested.

WWS recently published some crisply-written initial findings on governance and fragility. They echo the work of Matt Andrews and others on how institutional change happens. Hereâs a few highlights:

âThe stateâ is not homogeneous; even a weak or unwilling state may have levels of governance, departments, or particular officials interested in promoting change.

To achieve change it is necessary to work with both citizens and duty-bearers on developing a âsocial contractâ. The social contract refers to the agreement of citizens to submit to the authority of government in exchange for protection of their rights and access to services, security, and justice. Citizens will refrain from anarchy and respect the law; government will govern according to law, and promote peace and development.

Developing a social contract in a fragile context will be the product of ongoing explicit and implicit negotiation between different interest groups and a range of formal and informal power holders; the resultant contract will not be a static agreement but will be subject to renegotiation and changes in circumstances.

The advantage of using the social contract model in governance work is that it emphasises the roles and responsibilities of each party (citizens and government), and shows that by engaging with each other and taking a collective problem-solving approach (rather than by confrontation or challenge) they can work together to build a more effective state.

This can help prevent a negative backlash from a state with authoritarian tendencies, which may be nervous about the role of civil society, and give each party a realistic expectation of what the other can do.

MP Hon Rebecca Michael interacting with

her constituents at the end of the MP/public

dialogue, Wulu, South Sudan, February 2013.

Photo: Crispin Hughes

Approaches to governance work can also be adapted for more restricted contexts: governance can be developed as a strand within other work-streams, for example livelihoods, as this may prove less threatening to a government nervous about the role of civil society.

Addressing gender inequality is essential to governance work in fragile contexts and will actually improve its effectiveness. Gender inequality is itself a driver of fragility: in South Sudan, for example, high bride price fuels cattle raiding and conflict between tribal groups; in Afghanistan, women may be âgivenâ or âtakenâ to settle community disputes and conflicts; and womenâs exclusion from public life and decision-making in all fragile contexts means public policy will only address the needs of half of the population.

In fragile contexts, significant power may be held not by the state but by informal power-holders, such as tribal, traditional, or religious leaders. These informal power-holders may act either as âblockersâ or âenablersâ, preventing change that they do not see as desirable, or being able to influence formal power-holders in the state to achieve change. Strengthening governance may also involve working to improve the accountability and transparency of these informal power-holders, and ensuring they exercise their own power in the interests of citizens and communities.

This underlines the importance of conducting detailed power and context analysis to reveal where informal or hidden power lies in any particular context, how to target the source of power, and who can help to influence power-holders. Power analysis should be built around multiple sources of information including formal data and the âword on the streetâ. Analysis should be revisited frequently as power is constantly shifting in fragile contexts.

Overall Conclusion: It is possible to achieve change in fragile contexts, but it should not be short-term or measured only by conventional indicators and donor requirements. WWS has many examples of changes and successes achieved in fragile contexts:

⢠In Yemen, with support from WWS, the Civil Society Network in Ghail Bawazeer District conducted a participatory needs assessment, which identified water and health as priorities. The assessment was shared with local authorities during their annual planning process, and the council agreed to fund a new health unit and water project from its 2014 budget.

⢠In South Sudan a highly-restrictive NGO bill, which would have made it harder for CSOs to operate, was revised as a result of  lobbying by WWS and partner organisations, including consultation with civil society groups and lobbying of government officials. The bill has now been redrafted and is awaiting ratification. Lobbying around draft media legislation also resulted in the development of a more progressive bill than that first proposed.

lobbying by WWS and partner organisations, including consultation with civil society groups and lobbying of government officials. The bill has now been redrafted and is awaiting ratification. Lobbying around draft media legislation also resulted in the development of a more progressive bill than that first proposed.

⢠In the West Bank WWS trained community committees in five villages in participatory needs assessment, and supported them to engage positively with Palestinian authorities around better service provision. The process successfully mobilised and empowered the community, particularly women and youth who were enabled to play a more active role in community life.

⢠In Afghanistan WWS partners organised peace hearings in three provinces. At the Parwan Provincial Peace Hearing in August 2012, the Governor was questioned in front of the media and a range of issues were openly discussed â including ending violence against women and creating the security to enable women to participate in society. CSOs called for the issue of violence against women not to be ignored and for incidents of rape to be reported directly to the Governor, to which he agreed.

But the experience of WWS also shows that the pace of change is often slow because of the difficulty of the programming environment, and that the process followed may actually be as important to promoting good governance as the outcome.’

Lots more in the briefing and on the website. If youâre interested in the jobs, closing date is 21st Feb.

February 9, 2014

How to Write a really good Executive Summary? Here are some thoughts, but I need your comments.

Inspired by your great crowdsourcing on where to do a part time Masters (can someone collect the comments into a single document  please?), does anyone fancy helping me draft a short guideline on how to write decent executive summaries? Here’s the draft – over to you for improvements, suggestions for good/bad examples of the art etc. This is to add to Martin Walsh‘s burgeoning series of research guidelines on everything from semi-structured interviews to ethics to how to do a literature review- worth a look.

please?), does anyone fancy helping me draft a short guideline on how to write decent executive summaries? Here’s the draft – over to you for improvements, suggestions for good/bad examples of the art etc. This is to add to Martin Walsh‘s burgeoning series of research guidelines on everything from semi-structured interviews to ethics to how to do a literature review- worth a look.

Picture the scene. An exhausted author grinds to the end of a gruelling process of research, writing and sign off. A 40 page draft lies before them â by now they can hardly bare to even look at it, let alone read it yet again. But the front page has only two words on it âExecutive Summaryâ. OMG, better get on with it.

Disaster, because in terms of readership and impact, you should spend a lot of time and care on the Exec Sum, not a begrudging half hour at the end of months of slog.

Why? Because many more people will read the Exec Sum than ever read the whole paper. (Even more people will read the title and then decide not to bother with the report, but that’s another issue). The Exec Sum is the bridge between the often-technical arguments and findings of the main report, and the target audience, whether media, decision makers or aid professionals. Yet all too often, it is dashed off as an afterthought, badly written and missing some of the best nuggets in the main report. What a waste! Here are some ideas on how to get it right, or at least not as wrong.

Who? It may be better (if you can) to ask someone with a media or comms background to draft the Exec Sum. (The author should of course also check and revise the draft.) A fresh pair of eyes will be closer to the mindset of the eventual reader; they will spot whatâs interesting and new; they are more likely to avoid jargon and specialist vocabulary; they do not hate the report like the author probably does by now. If youâre a one-person outfit without the luxury of a second pair of eyes, at least get a good nightâs sleep and maybe spend a day working on something else to clear your head before starting in on the Exec Sum.

What? Try and keep it to two pages max – one sheet of double sided paper, (and donât cheat by shrinking the font â if anything it should be larger than for the main report). Above two pages, you will lose readers fast. If you can get it down to a single page, or even a single paragraph (for example if there is one stand-out finding from the report), so much the better.

And now for the Exec Sum…

The first paragraph is the Exec Sum of the Exec Sum â crucial to getting and keeping the readersâ attention (imagine a tired journalist skimming a dozen incoming reports, or someone in front of a computer scanning their RSS feed â what makes them keep reading, rather than moving onto the others?). It should say who your organization is, why it has written this report, and what is new or interesting in it.

You need a clear statement of the problem the report is addressing and the key findings of the research.

Identify and import any killer facts or particularly striking graphics from the main report.

Add a few of the main recommendations, but not a two page shopping list

How? If you are a new pair of eyes, first interview the author to get their views on what is new or interesting. They will know both the report and the other literature on the topic far better than anyone else in the organization.

Then start with the original full report (not the ToRs or the original Concept Note â they should have been superseded by the report.) Read it carefully, particularly the first and last sentences of each paragraph. Highlight key words or ideas, (even if youâre the original author, this may be a worthwhile exercise) as well as killer facts and good graphics.

Using these prompts, construct the strongest possible narrative. If you have trouble doing so, that may be because the report itself is not clear, either in arguments or structure â writing the Exec Sum can often lead to tweaking the main report, so you may need to go back to the author on this.

Re-read it, test it, get others to read it and comment on what does/doesnât make sense. If youâre a fresh pair of eyes, ask the author to factcheck it and point out any key omissions. Take your time – this is the most critical part of the report.

Things to Avoid

Do not introduce the structure of the main report: âin section one, we discuss the context of Xâ â the Exec Sum needs to work as a  standalone document.

standalone document.

Do not introduce new ideas, references, or arguments.

Donât oversell â sprinkling hype (âgroundbreaking, breathtaking, extraordinary, outrageousâ) over the document will put people off. Substance, not superlatives, is what will convince them to keep reading.

Keep jargon and acronyms to an absolute minimum, and explain their meaning the first time you use them. In particular minimise the use of mind-numbing development speak (ongoing participatory processes etc). Keep in mind George Orwellâs guide to how to write.

Examples of Good/Bad Exec Sums

Please send me your favourites in both categories, (including Oxfam papers of course) along with your reasons for proposing them. Plus a special mention for the person sending the longest/shortest Exec Sum.

And to get you started, here’s a few from the business world

February 6, 2014

What makes a perfect short field trip (and a top village power analysis)?

I had a pretty perfect one-week field trip to Tajikistan last week. Two days down in the South, talking to villagers, activists, officials, and our own local staff about the hardware part of our Tajikistan Water and Sanitation (TajWSS) project â working with local government to install water systems under their ownership and local Water User Association control. (Iâve already blogged about the software part – convening and brokering dialogues to sort out the institutional quagmire at national level). The conversations in the back of the car and over meals between visits are as important as the visits themselves.

our own local staff about the hardware part of our Tajikistan Water and Sanitation (TajWSS) project â working with local government to install water systems under their ownership and local Water User Association control. (Iâve already blogged about the software part – convening and brokering dialogues to sort out the institutional quagmire at national level). The conversations in the back of the car and over meals between visits are as important as the visits themselves.

The initial trip constituted an intensive two day immersion in all things Tajik, through which enough of a picture of Tajik society emerged to enable me to ask more (better) questions on day 3 â a tour of bilateral and multilateral donors back in the capital. Then all of that fed into the final two days – a workshop with staff and partners, scoping out some work on how to build social accountability in the crumbling water sector â funded under the World Bankâs GPSA facility.

How to get the most out of the two days? Stay alert, get some sleep, and talk to as many people as possible. But it pays to focus in the right areas too:

Official structures: These may seem tedious (âso how does the village government related to the district, and then the province?), but is absolutely crucial. Any serious programme needs to understand the tiers of government and the division of responsibilities between them; their relative accessibility/sympathy with the local population; who listens to who; who jumps when who calls. That means talking to different kinds of people at different points in the food chain â lowly bureaucrats can be particularly insightful.

Official structures: These may seem tedious (âso how does the village government related to the district, and then the province?), but is absolutely crucial. Any serious programme needs to understand the tiers of government and the division of responsibilities between them; their relative accessibility/sympathy with the local population; who listens to who; who jumps when who calls. That means talking to different kinds of people at different points in the food chain â lowly bureaucrats can be particularly insightful.

Village power map: Outsiders often see a power vacuum, or a monoculture, but it never is. Just keep probing. NGOs/civil society organizations may not be the best guide â we tend to only notice organizations that look like us. Wise individuals are good. Understand formal structures of power, but then probe for the informal ones â who does the population trust? What are the islands of mutual trust (social capital)? Where do men or women meet and talk? âWho you turn to depends on the issue: for policy you go to the village head, for health problems to the doctor, if you have bad dreams, you go to the mullah.â Gender differences are crucial â and often difficult to investigate for men. The ideal is to talk to women directly, but what if only men show up to the meetings (which often happened in Tajikistan)? Best to ask the advice of female staff, maybe go with them to talk to women, or use secondary sources to fill out the picture.

âSoft eyesâ (as advocated by Bunk in The Wire): Be open to noticing stuff in your peripheral vision, not just the extractive âI came here to find out about Xâ. What do people spend money on? How come so many village heads make their living as drivers? What are those new buildings for? Where do you see people hanging out?

Every day throws up a dozen mysteries, and ideas for things to try if youâre working on governance, accountability, water or anything else: test them through conversation and see which fly/get shot down. Youâll end up with a few suggestions worth investigating further.

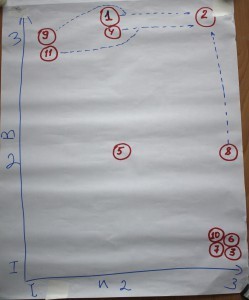

Back in the Dushanbe workshop, we asked staff and partners to do a village power map, identifying stakeholders and locating them in terms of a) their level of interest in water and accountability (x-axis) and b) their influence over decisions (y-axis). The result is worth taking a look at. The dotted arrows are for possible influencing strategies â how to move particular stakeholdersâ level of interest/influence to further the aims of the project. Just how to do that would require lots of further discussion. Fascinating analysis, I hope youâll agree.

Table reads:

Stakeholder

Level of Influence

Level of Interest

Head of local Council (Jamoat) â appointed

3

2

Head of Village â chosen by villagers

3

3

School Principal

1

3

Mullah (religious leader)

3

2

Doctor

2

2

Respected village elders

1

3

Womenâs Groups

1

3

Community Based Organizations

2

3

State employees

3

1

Educated People

1

3

Relatives (and lovers!) of powerful people

3

1

February 5, 2014

States v Markets: Understanding Tajikistan’s Post-Soviet malaise through its drinking water

I don’t do much on water (as my pal Henry Northover at WaterAid never fails to remind me) but last week, I was in Tajikistan to help  our team think through their water-related work. They already run the Tajikistan Water Supply and Sanitation (TajWSS) network, which combines a high level ‘convening and brokering’ approach to finding solutions to the country’s dire water situation, with a more hands-on Water Trust Fund that co-finances (with local communities and government) water supplies for some 40,000 consumers.

our team think through their water-related work. They already run the Tajikistan Water Supply and Sanitation (TajWSS) network, which combines a high level ‘convening and brokering’ approach to finding solutions to the country’s dire water situation, with a more hands-on Water Trust Fund that co-finances (with local communities and government) water supplies for some 40,000 consumers.

That’s a drop in the ocean (sorry) in a country of 8 million people, but allows us to pilot the kind of ideas that emerge in the wider network discussions, such as a ‘technical passport’ for local systems, which acts as proof of ownership and inventory – gold dust in a world of very vague property rights.

Now we’ve got some water-related funding from the World Bank’s new Global Partnership for Social Accountability, so I was in Dushanbe to help us think through its underlying theory of change (more on that tomorrow).

Water provides a pretty good way in to understanding Tajikistan’s wider development challenges. First, the Soviet hangover: not just the lack of cash, but a legacy of big, top down construction and accompanying standards that prevent improvisation or low-cost innovation – water engineers and administrators cling to the old ways, even though they can no longer afford them.

That is part of a wider narrative of decline. Everything was better in the old days. Even the Government thinks so – its job adverts say preference will be given to those qualified before 1992. ‘If you want a solid engineer, you want someone educated in the Soviet system – but they just think about pipes, not people.’ It’s distinctly odd hearing the Soviet Union held up as model of effectiveness.

25 years on, what remains is a vaguely post-apocalyptic squalor of crumbling infrastructure, electricity and water for only a few hours a day, towns full of rotting apartment blocks patched with plastic and blankets. And some truly indescribable toilets.

At an institutional level, the water system is paralysed by the overlapping mandates of regulators and operators and competing tiers of government. It’s often not even clear who is the legal owner of a water system.

I realize there are issues of equity of access to think through, but I came away convinced of the potential progressive impact of introducing market forces and individual water meters: the villagers welcome them because in the prevailing institutional anarchy, introducing metered fees per household creates a form of mutual expectation and accountability – a big shift in thinking that I think is more likely to get water to poor people than seeing water as an essential service that should be funded through general taxation.

‘Before, water was free and no discussion. People had no idea where the pipes came from. Now we have to pay, and be involved on accountability. It’s a massive culture shift. In cities people are starting to understand, but in rural areas, people still think it’s a gift from God.’

The best results come when a single village has a single system – any multiplicity (more than one village or system) leads to doubt, suspicion and abstention. Elsewhere, willingness to pay for services is intriguingly varied – farmers will pay for vets, but not for agronomists (more immediate returns, clearer attribution of impact).

As for why all this matters, here’s Parvina Rahmonova (left), a villager who recently got a household water connection through TajWSS:

As for why all this matters, here’s Parvina Rahmonova (left), a villager who recently got a household water connection through TajWSS:

‘Now we don’t have to cart water – it’s the best thing ever. The kids used to carry it. Now they can work in the kitchen garden and attend school properly. We sold the donkey because we don’t need it any more. What could be better? Nothing!’

She pays around US$2 a month for a home connection and 8 cubic metres of water.

‘Before we had to carry it for a kilometre by hand or sledge in winter. It took over 2 hours each trip, 2 or 3 times a day, and I have a small family. So I save 4 hours a day – what do I do with it? Sew dresses and embroidery for sale – I get orders. We’ve been able to have a proper kitchen garden for the first time – before we just had to rely on the rain.’

Then there’s a bigger picture – Tajikistan, with its huge mountain ranges and glaciers, has water resources that are the envy of the rest of the region (and potentially the source of conflict between upstream and downstream water users, like the Nile countries in East Africa). But climate change means the glaciers are melting, as we reported back in 2010.

Tomorrow: the perfect field trip and an exercise in village level power analysis.

States v Markets: Understanding Tajikistanâs Post-Soviet malaise through its drinking water

I donât do much on water (as my pal Henry Northover at WaterAid never fails to remind me) but last week, I was in Tajikistan to help  our team think through their water-related work. They already run the Tajikistan Water Supply and Sanitation (TajWSS) network, which combines a high level âconvening and brokeringâ approach to finding solutions to the countryâs dire water situation, with a more hands-on Water Trust Fund that co-finances (with local communities and government) water supplies for some 40,000 consumers.

our team think through their water-related work. They already run the Tajikistan Water Supply and Sanitation (TajWSS) network, which combines a high level âconvening and brokeringâ approach to finding solutions to the countryâs dire water situation, with a more hands-on Water Trust Fund that co-finances (with local communities and government) water supplies for some 40,000 consumers.

Thatâs a drop in the ocean (sorry) in a country of 8 million people, but allows us to pilot the kind of ideas that emerge in the wider network discussions, such as a âtechnical passportâ for local systems, which acts as proof of ownership and inventory â gold dust in a world of very vague property rights.

Now weâve got some water-related funding from the World Bankâs new Global Partnership for Social Accountability, so I was in Dushanbe to help us think through its underlying theory of change (more on that tomorrow).

Water provides a pretty good way in to understanding Tajikistanâs wider development challenges. First, the Soviet hangover: not just the lack of cash, but a legacy of big, top down construction and accompanying standards that prevent improvisation or low-cost innovation â water engineers and administrators cling to the old ways, even though they can no longer afford them.

That is part of a wider narrative of decline. Everything was better in the old days. Even the Government thinks so â its job adverts say preference will be given to those qualified before 1992. âIf you want a solid engineer, you want someone educated in the Soviet system â but they just think about pipes, not people.â Itâs distinctly odd hearing the Soviet Union held up as model of effectiveness.

25 years on, what remains is a vaguely post-apocalyptic squalor of crumbling infrastructure, electricity and water for only a few hours a day, towns full of rotting apartment blocks patched with plastic and blankets. And some truly indescribable toilets.

At an institutional level, the water system is paralysed by the overlapping mandates of regulators and operators and competing tiers of government. Itâs often not even clear who is the legal owner of a water system.

I realize there are issues of equity of access to think through, but I came away convinced of the potential progressive impact of introducing market forces and individual water meters: the villagers welcome them because in the prevailing institutional anarchy, introducing metered fees per household creates a form of mutual expectation and accountability – a big shift in thinking that I think is more likely to get water to poor people than seeing water as an essential service that should be funded through general taxation.

âBefore, water was free and no discussion. People had no idea where the pipes came from. Now we have to pay, and be involved on accountability. Itâs a massive culture shift. In cities people are starting to understand, but in rural areas, people still think itâs a gift from God.â

The best results come when a single village has a single system â any multiplicity (more than one village or system) leads to doubt, suspicion and abstention. Elsewhere, willingness to pay for services is intriguingly varied â farmers will pay for vets, but not for agronomists (more immediate returns, clearer attribution of impact).

As for why all this matters, hereâs Parvina Rahmonova (left), a villager who recently got a household water connection through TajWSS:

As for why all this matters, hereâs Parvina Rahmonova (left), a villager who recently got a household water connection through TajWSS:

âNow we donât have to cart water â itâs the best thing ever. The kids used to carry it. Now they can work in the kitchen garden and attend school properly. We sold the donkey because we donât need it any more. What could be better? Nothing!â

She pays around US$2 a month for a home connection and 8 cubic metres of water.

âBefore we had to carry it for a kilometre by hand or sledge in winter. It took over 2 hours each trip, 2 or 3 times a day, and I have a small family. So I save 4 hours a day â what do I do with it? Sew dresses and embroidery for sale â I get orders. Weâve been able to have a proper kitchen garden for the first time â before we just had to rely on the rain.â

Then thereâs a bigger picture â Tajikistan, with its huge mountain ranges and glaciers, has water resources that are the envy of the rest of the region (and potentially the source of conflict between upstream and downstream water users, like the Nile countries in East Africa). But climate change means the glaciers are melting, as we reported back in 2010.

Tomorrow: the perfect field trip and an exercise in village level power analysis.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers