Duncan Green's Blog, page 201

November 28, 2013

Hunger Grains: Are EU policies undermining progress on development?

An earlier version of this piece appeared in the October issue of the Government Gazette

Today we fear EU ambassadors will agree a really bad deal on EU biofuel reform. In 2009 EU governments agreed that by 2020 10% of the energy used in transport would have to come from renewable sources. This target will almost exclusively be met by using food-based biofuels and has prompted a surge in investment, much of it via land grabs: data from ActionAid show that in sub-Saharan Africa six million hectares of land are now under the control of European companies planning to cash in on the policy windfall.

But as evidence piles up, it is becoming increasingly clear that what may have started as a well-intentioned policy to try to make our transport fuels greener has turned out to be disastrous for global hunger. By 2020, EU biofuel targets could push up the price of vegetable oils by up to 36%, maize by 22%, wheat by 13% and oilseeds by up to 20%. It also turns out that many biofuels are harmful to the environment – leading to deforestation and greenhouse gas release.

greener has turned out to be disastrous for global hunger. By 2020, EU biofuel targets could push up the price of vegetable oils by up to 36%, maize by 22%, wheat by 13% and oilseeds by up to 20%. It also turns out that many biofuels are harmful to the environment – leading to deforestation and greenhouse gas release.

There has been some recognition that biofuel policies are having negative impacts and need to be reformed. In October last year, the European Commission proposed amending the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive by introducing a 5% limit for counting food crop-based biofuels towards the 10% target, improving sustainability criteria and promoting the use of advanced biofuels (which don’t harm food production). But since then the biofuel lobby has swung into action, and in the proposal for discussion today, the 5% cap has been watered up to 7%, complete with loopholes such as allowing statistical transfers (biofuel laundering) between states.

The EU decision really matters: for the moment the biofuel market in Europe is driven by mandates not markets – no biofuels can compete with oil without support. The EU should at the very least remove all mandates, subsidies and tax incentives, but it’s created a vested interest intent on preventing that happening. If the ambassadors sign today as expected, EU energy ministers meeting on 12 December will still have the option to make changes rather than rubber stamping the deal.

This is all the more depressing because in recent years, there has been much to celebrate in terms of the role of agriculture in development. An intellectual turning of the tide has recognised that improving small farmer production is often the most effective way to turn growth into poverty reduction, and more research brainpower has been invested in how to ensure that farming lifts people out of poverty (rather than traps them in it). For a useful synthesis of a recent Oxfam-hosted online debate, see here.

That intellectual shift has been mirrored in public policy, with initiatives such as the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), and aid from traditional donors rising from $2.3 in 2002 to $5.3bn in 2011 (and that does not include a rising amount of agricultural aid from new donors like China and Brazil).

Biofuels illustrate a real lack of policy coherence with this renewed focus on agriculture, as do land grabs.

Biofuels illustrate a real lack of policy coherence with this renewed focus on agriculture, as do land grabs.

Land grabs, more neutrally known as ‘large scale land acquisitions’, are big business. ‘Buy land. They’re not making it any more,’ joked Mark Twain, and around the world, a lot of investors are taking his advice to heart. In the past decade an area of land eight times the size of the UK has been sold off. More than 30 per cent of Liberia’s land has been handed out.

That might be a good thing if the investment went to small farmers, and boosted food production. Oxfam estimates this land could feed a billion people, equivalent to the number of people who go to bed hungry each night. But that is not happening. From around the world come stories of small farmers being expelled, often at dead of night, to make way for foreign investors in what are often decidedly dodgy deals: land grabs and bad governance go hand in hand.

Instead of food, land is either left idle as a speculative access (a particularly criminal waste), or, in two thirds of cases, turned over to export crops.

The growing evidence and some effective campaigning have overcome initial denials of the problem. In April, World Bank president Dr Jim Yong Kim acknowledged that ‘The World Bank Group shares concerns about the risks associated with large-scale land acquisitions’. In June, the G8 followed suit with the Lough Erne declaration, saying ‘land transactions should be transparent, respecting the property rights of local communities”.

Such good intentions face significant obstacles – a new era of high food prices has pushed up land values. That means big returns for speculators, and money talks, in politics as well as in economics. But so do public protest, champions inside the corridors of power and clear research evidence of the negative impacts of the land grab tsunami. With so much at stake, the struggle for land is likely to be a core element in development for the foreseeable future.

As for the biofuels decision, Oxfam’s campaigners and lobbyists are hard at work to prevent a bad agreement on 12 December – I’ll keep you posted.

November 27, 2013

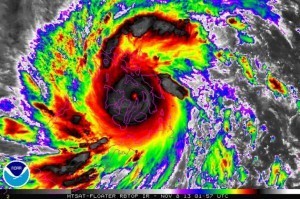

Transform or be Haunted by Ghosts: How can the Philippines ‘build back better’ after Typhoon Haiyan?

From the middle of the response to Typhoon Haiyan, Lan Mercado, our Deputy Regional Director in Asia (and passionate campaigner and Filipina) reflects on what lies ahead. She was the one who asked me to pick your brains on disasters as opportunities – thanks for the responses.

Filipina) reflects on what lies ahead. She was the one who asked me to pick your brains on disasters as opportunities – thanks for the responses.

The massive impact of Typhoon Haiyan claimed thousands of lives and destroyed physical assets, but it also felled institutions and tore the community fabric apart. The lawlessness that erupted days after Haiyan was an unfolding secondary disaster that abated after relief trickled through.

The shell-shocked national government was initially in denial about the extent and complexity of the destruction, until officials individually started to admit there was something wrong with the system. A top Cabinet secretary whom our assessment team met on the ground on Day 3 told them that if they wanted to take over, they should take over everything. This, in the Philippines, a Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) poster country.

Two weeks have passed since Haiyan struck. International humanitarian assistance has picked up pace; yet, many remain unreached. As it was on Day 1, what’s needed for survivors to access relief materials and essential services is the combination and coordination of solutions that include logistics, technical interventions, the protection of civilians and humanitarians, the restoration of local governance institutions and the decisions and action of leaders that people trust.

For those who survived, life changed right after the storm’s unprecedented fury. Women are now widows, and the shift in status means their burdens are heavier. Households are reassigning roles amongst members. Fifty-one urban centres no longer resemble the places that they were. Production and consumption patterns are altered, at least temporarily. People have fled from the disaster zones to seek refuge with relatives. Many will contribute to the swelling population of informal settlers in the cities that took them in.

Obviously, this has implications for those cities’ resources, which were not very well planned to begin with. But a number of those who fled on C130s have no options other than to stay in the makeshift evacuation centre in the airbase where they landed or in temporary shelters that the government hastily put together.

‘Building back better’ is a phrase that’s being thrown around. President Aquino formed a task force to coordinate rehabilitation efforts, and gave it five days to come up with a comprehensive program. Recovery and rebuilding will be gargantuan and complex tasks, not made easier by the multitude of experts on ecology, land use planning, architecture, infrastructure, building codes, better preparedness, the science of early warning and risk mitigation—they are as many as the opinions published in editorial pages. Like Haiyan’s murderous winds, ideas are swirling, and at their centre are the Philippine government and the Filipino people, who must find their bearings.

‘Building back better’ is a phrase that’s being thrown around. President Aquino formed a task force to coordinate rehabilitation efforts, and gave it five days to come up with a comprehensive program. Recovery and rebuilding will be gargantuan and complex tasks, not made easier by the multitude of experts on ecology, land use planning, architecture, infrastructure, building codes, better preparedness, the science of early warning and risk mitigation—they are as many as the opinions published in editorial pages. Like Haiyan’s murderous winds, ideas are swirling, and at their centre are the Philippine government and the Filipino people, who must find their bearings.

The creation of this task force answers questions raised about the lack of a central planning authority needed to ‘traverse jurisdictional boundaries’ that are features of the Philippine’s decentralised political landscape. The task force includes key Cabinet officials to tackle shelter and reconstruction, resettlement, power, livelihood and employment, resource generation and allocation, local government coordination and, crucially, the engagement of the citizenry at the grassroots level. Aquino said that it is important to ‘enable people to attain greater self-reliance while participating in the rebuilding of their communities.’

The private-sector led Disaster Recovery Foundation has convened and will get its direction from this task force. But it has also met with the UNDP and Oxfam to get ideas and learn how Aceh, Haiti and other places picked up the broken pieces of their disaster-hit societies and recovered.

The ‘contributions to change’ of international actors like Oxfam begin at the point of the disaster’s impact. But Oxfam does more than just respond to disasters in the Philippines. Over the 25 years that it has worked in the country, it has pushed reforms in the humanitarian, risk reduction and development spheres, sometimes operating on its own, most of the time working with partners, and always guided by its own analysis and engaged with others.

A significant part of our contribution was political. Writing about Oxfam in the Philippines, Edicio dela Torre said ‘Oxfam’s international character and connections have… supported the political choices made by partners… and these include the politics of resistance.’

connections have… supported the political choices made by partners… and these include the politics of resistance.’

Oxfam speaks and works on behalf of the marginalised, excluded and vulnerable. Oxfam does this because ‘we believe in their strategic potential for achieving equity and sustainability,’ says dela Torre. He cautions that ‘it is not easy to link our work from the edges with our advocacy work toward those in power, especially if we do not want to be permanent substitutes for the relatively voiceless and powerless. And as we succeed in our advocacy work, we must be wary of the temptation to become simply new inside players in existing circles of power. The ability to work simultaneously outside and inside the dominant system is what we need to hone and handle well, if we are to be effective in pursuing our common purposes.’

Opportunities for Transformation

In Haiyan’s wake is a swathe of destruction and a window for disruptive change. Opportunities for transformation abound. They include transformations in gender relations and women’s increased political participation. Gender roles may, in fact, already be shifting as a consequence of Haiyan. Men have lost their usual livelihoods and are desperate to restart them. Meanwhile, wives still have to feed the children and will be breadwinners one way or another. Children, too, will have to help find food or money. Relief distributions must attend to their impact on household dynamics. One woman came to a distribution line with visible bruises, beaten by an angry husband because she failed to get hold of relief packs the day before.

The Philippines’ location and geography make future disasters a given, and countermeasures should be both for possible mega disasters and for smaller, repetitive and certain disasters, whose occurrence erodes whatever physical and financial assets poor people are able to accumulate. Influencing the country’s development paradigm so that it front-loads risk reduction, promotes sustainable livelihoods that raise resilience, and rides on government-civil society-private sector multi-stakeholder partnerships is not just logical, it is moral.

The near obliteration of buildings and other infrastructure in Haiyan’s hardest hit cities clears the way for urban development and land use planning to be set aright, which could tip the balance for the rest of the country. The proposed National Land Use and Management Act (NALUMA), advocated by civil society but languishing in Congress for years, may now become law and defy it’s acronym’s unfortunate Tagalog meaning—’to become old’ and forgotten.

It’s possible to think about a DRR body that has more political clout and credibility. Grassroots people’s empowered participation in governance can be facilitated if they can use scientific risk data. Having understood how bad development underpins risks, a few municipalities and provinces that suffered the wrath of Typhoon Ketsana in 2009 have learned to say no to risk-producing corporate investments.

Haiyan broke existing storm records, and established a new benchmark. For NGOs that respond to disasters, Haiyan has profound implications for how to manage a sudden, massive and complex emergency: rapid assessment methodologies, preparedness and actual capacity to respond, the role of advocacy and influencing alongside emergency response, working with governments and regional inter-governmental bodies. We need a thorough review, if not a total re-imagination.

As an international NGO, Oxfam may look like an outsider in national transformations. But in the Philippines, Oxfam has a mostly Filipino staff and we do not consider ourselves external actors. Some of these staff have family that went missing. We wrung our hands even as we continued working. Even the loss of someone unknown to us sent us weeping. We bore each other’s sadness, propped each other’s hope. Perhaps this is what it means to be a people. Tenuous and transient these bonds might be, we cling to them as we would to lifelines.

Five thousand lives lost but most likely many, many more. We must make each one count. If Haiyan does not transform us as individuals and the Philippines as a country, we are cursed to be haunted by ghosts.

If you would like to donate to Oxfam’s Philippines response, please go here. And just because I love the photo, here’s Lan back in the day, stirring up trouble.

November 26, 2013

Thinking and Working Politically: an exciting new aid initiative

Gosh I love my job. Last week I attended a workshop in Delhi to discuss ‘thinking and working politically’. A bunch of donors, academics, NGOs and others (Chatham House rules, alas, so no names or institutions) taking stock on how they can move from talk to walk in applying more politically informed thinking to their work.

others (Chatham House rules, alas, so no names or institutions) taking stock on how they can move from talk to walk in applying more politically informed thinking to their work.

That means both trying to do the normal stuff better (eg understanding the politics that determines whether your water or education programme gets anywhere) and in more transformational work trying to shift power from haves to have nots.

The meeting was convened by some very practical (‘what do I do on Monday Morning’) aid people keen to move on from what they see as the overly academic (‘needs more research’) character of discussions on governance, institutions, state-building and all its obfuscatory language (‘What we don’t need is lots of people talking about isomorphic mimicry, rules of the game and political settlements’).

The purpose of this discussion was to take the growing body of research from the Development Leadership Programme, Tom Carothers, ODI, Matt Andrews, ESID etc and turn it into programme ideas that can be tested on the ground. A giant ‘do tank’ exercise, in fact. Alarmingly, I can’t think of other examples of such an explicit research →hypothesis→test process on governance (unlike drugs research, say).

Some impressions:

The political economy of donors: lots of discussion on the institutional barriers to progress – ‘projectization’, logframes, value for money, results agenda, short time frames, staff rotation. One of the few potentially positive side effects of the dismemberment restructuring of aid ministries in Australia and Canada and their takeover by foreign ministries is that diplomats don’t do logframes – they understand the importance of relationships and seizing opportunity. (Trouble is they do so to pursue national self-interest, rather than development.)

People not products: This is about having the right people, working in the right way: ‘searchers’ and mavericks able to spot opportunities as they open up, thinking on their feet, building relationships. Big question is whether this is teachable – are people who work politically born not made? Local staff are more likely than expats to be embedded in the political realities, but are also more likely to be junior and cowed by the institutional machine. Supporting them needs mentoring rather than (yet more) workshops, but also accepting that we need a percentage of mavericks who don’t do what they’re told (or what they’ve said they’ll do). Tough for any bureaucracy to accept.

People not products: This is about having the right people, working in the right way: ‘searchers’ and mavericks able to spot opportunities as they open up, thinking on their feet, building relationships. Big question is whether this is teachable – are people who work politically born not made? Local staff are more likely than expats to be embedded in the political realities, but are also more likely to be junior and cowed by the institutional machine. Supporting them needs mentoring rather than (yet more) workshops, but also accepting that we need a percentage of mavericks who don’t do what they’re told (or what they’ve said they’ll do). Tough for any bureaucracy to accept.

Labour intensive not capital intensive: Good politically-informed work is about relationships, trust and a subtle understanding of power and politics. Very hard to achieve that while waving a chequebook (‘if you come in with $ and say ‘we’re here to set up a coalition’, you will get one! You’re a good-looking guy’). The pressure to spend can be a serious obstacle to this longer term, more painstaking work.

What are the risks of ‘working politically’? A certain amount of self-deception here. Everyone else (southern governments, civil society organizations etc) already sees aid as heavily political, so who are we trying to kid? But being explicit about engaging with political players, elections, supporting change coalitions etc works better in more permissive contexts, whereas elsewhere it will lead to accusations of infringement of sovereignty, especially if it’s bilateral agencies doing it.

organizations etc) already sees aid as heavily political, so who are we trying to kid? But being explicit about engaging with political players, elections, supporting change coalitions etc works better in more permissive contexts, whereas elsewhere it will lead to accusations of infringement of sovereignty, especially if it’s bilateral agencies doing it.

Dangers of Openness: Some of this is about the dark arts of influencing – how you persuaded a politician to do something, but then enabled them to take the credit. How you twisted arms, or appealed to self interest. Disclosure can damage the project. One old hand from a multilateral complained ‘no wonder everything I say sounds bland and generic – I can’t tell all the interesting stuff!’

Should it stay below the radar? Ros Eyben among others has documented the double discourse of aid workers – they are adept at saying one thing and doing another, eg presenting a project as purely technical/apolitical, then using all the tricks of advocacy to get them implemented. If we try and drag such practices into the light, do we risk destroying them? In some countries, the technocratic veneer is important camouflage, but elsewhere the general view was that acknowledging the realities can ‘unleash a lot of energy’ among staff who can then ‘fess up about what aid work is really like, and learn from each other out in the open.

Overall, I was struck by the contrast between the intellectual self confidence – a bunch of highly experienced senior aid types saying there is simply no other way to go in order to improve the impact of aid – and the fragmenting institutional context – Ausaid and CIDA being subsumed into foreign ministries, the demands of a dumbed down version of the results agenda and value for money, a general aversion to taking risks of any kind for fear of imperilling aid budgets. Really hope the good guys are right.

Next steps? This looks like an incipient ‘community of practice’, with the focus on the practice. Lots of appetite for building a good evidence base, with the healthy caveat from one senior aid boss ‘I want anecdotes, I don’t want evidence – I’m serious. I’m fed up with research – it’s not going to persuade the minister.’ A further meeting is planned in January – watch this space.

This blog is getting a facelift – what would you like to change/keep the same?

Dear FP2P readers

Our IT guys tell me it’s time for a makeover, (sadly, only for the blog, not for me). So I’m asking for suggestions. What aspects of this blog’s format (not  content – that’s a separate discussion) do you find useful and want to keep unchanged, and what do you find really annoying/ want to add/change?

content – that’s a separate discussion) do you find useful and want to keep unchanged, and what do you find really annoying/ want to add/change?

So far, we are planning to:

- add a print button for oldies like me who prefer to print stuff out

- make the site more mobile friendly

- have posts on separate pages rather then running down the page

Plus any thoughts about displaying the archive. Would you use a Greatest Hits option – most viewed or most commented? Do you want to see the most recent videos?

And more generally, if you have some blog that strikes you as a good model for us to copy, send us the link.

Over to you. Some sort of dodgy prize for the most useful response…….

How often do people search for older posts – why =do they search for them? – give us some ideas about how to display older posts

November 25, 2013

The evolving HIV & AIDS pandemic: overall progress; more varied between countries; southern governments stepping up to fill aid gaps

Today the ONE campaign is issuing The Beginning of the End?, a report (+ exec sum) on the HIV/AIDS pandemic, with some important findings. They  include hitting the global tipping point on AIDS, probably next year; the increasing divergence in performance between African countries, and the fact that over half of global HIV/AIDS spending now comes from developing countries.

include hitting the global tipping point on AIDS, probably next year; the increasing divergence in performance between African countries, and the fact that over half of global HIV/AIDS spending now comes from developing countries.

Excerpts from the Exec Sum, with a few additions from ONE’s press release, plus a final comment from Oxfam’s top HIV policy wonk:

“The world has achieved a marked acceleration in its progress towards the achievement of the beginning of the end of AIDS (defined as when the total number of people newly infected with HIV in a given year falls below the number of HIV-positive people newly receiving antiretroviral (ARV) treatment). Updated data shows that if current rates of acceleration in both adding individuals to treatment and in reducing new HIV infections continue, we will achieve the beginning of the end of AIDS by 2015 (see chart – click to enlarge).

Programmes to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV continued to scale up in 2012, particularly among the 22 high-burden countries. Seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa – Botswana, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa and Zambia – are driving much of this progress, having each reduced new HIV infections among children by 50% or more since 2009. But collectively the world is not on track to meet the virtual elimination goal by 2015, and a few countries, such as Nigeria and Angola, are holding back regional and global progress.

Real reductions have been made in new adolescent and adult HIV infections for the first time in years, which is encouraging, but progress to cut that figure by half is still dramatically off track, and marginalised populations are falling further behind. HIV prevention remains the area of least progress and least attention.

Unfortunately, the price of partial success is that HIV/AIDS is no longer perceived as a global health emergency, but rather a chronic and manageable disease, and the fight has lost some of its political momentum. UNAIDS estimates that global financing efforts for AIDS still fall $3–5 billion short of the $22–24 billion needed annually. In 2012, the US remained the clear global leader on total AIDS financing, and the UK, Australia, Japan, Italy and Sweden increased their contributions.

However, other countries including Denmark, Canada, France, Ireland, Norway and the Netherlands, along with the European Commission, decreased their overall contributions in 2012.

And developing countries are stepping up. More than two-thirds of low- and middle-income countries increased domestic spending on HIV last year, accounting for 53% of all HIV/AIDS resources globally – the second year in a row that these countries have supported more than half of the global response.

It is time to retire the phrase ‘AIDS in Africa’. Political will and financial investments have varied dramatically between countries; so too have countries’ relative successes in making headway towards the beginning of the end of AIDS. 16 countries in sub-Saharan Africa have already reached the beginning of the end of AIDS, but others lag far behind.

relative successes in making headway towards the beginning of the end of AIDS. 16 countries in sub-Saharan Africa have already reached the beginning of the end of AIDS, but others lag far behind.

The nine countries profiled in the report broadly exemplify three levels of progress:

Leading the Way: Ghana, Malawi and Zambia are great examples of how international donors, national governments and key civil society leaders can work together to achieve accelerated progress in the fight against AIDS.

Ones to Watch: South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda have shown real dynamism but erratic progress as they face massive disease burdens, shifting political landscapes and unique, country-specific challenges.

Urgent Progress needed: Cameroon, Nigeria and Togo have not made enough progress. Togo, in particular, reached the AIDS tipping point in 2010 but has slipped back since.

In all countries, a wealth of CSOs and individuals are actively engaged in their communities and countries in the fight against the disease. Some of these groups are supporting and bolstering broader country-level efforts, while some are actively driving progress in spite of challenging circumstances or government intransigence. Their commitment and advocacy have been critical to the progress achieved on the continent over the past two decades.”

And here’s a brief comment from Dr Mohga Kamal-Yanni, our health & HIV policy advisor (who asked me not to call her a guru, so I haven’t):

“The report clearly shows that good aid can save lives. National and international financial commitment, combined with reduced prices of medicines due to generic competition, have made it possible for countries to combat the plight of HIV.

While the report rightly focuses on financing the response to HIV, it misses emphasising the role of generic competition in reducing the prices of medicines and thus making it possible for donors and governments to finance treatment. This is important in the current and future situation, where new, effective medicines are under patent and thus difficult to produce in India (the main manufacturer of generic anti-HIV medicines) or in other countries. How would the world pay for expensive medicines?

It is also important for HIV reports to discuss how to ensure that HIV progress in treatment can strengthen and benefit from national systems e.g. drug procurement and supply chains, so that short-term achievements can be sustained in the long term. How to maintain and improve measures taken to provide HIV treatment despite the current health workers crisis? For example how to sustain and expand to other health issues measures like: task shifting from highly trained doctors to nurses, community health workers’ involvement, proper remuneration of health workers etc.’

And here’s the inevitable infographic:

November 24, 2013

Is village immersion a new approach to development studies? Is suicide a development issue?

I was in Delhi this week, talking to Oxfam India and taking part in a conference on how to work on issues of governance, politics and institutional reform (more on that later).

(more on that later).

But on Wednesday I took time out to give a lecture (on poverty v inequality – powerpoint here – keep clicking) at Ambedkar University, a new social sciences outfit on the edges of Old Delhi (v atmospheric – an oasis of big trees and monkeys amid streets clogged with traffic).

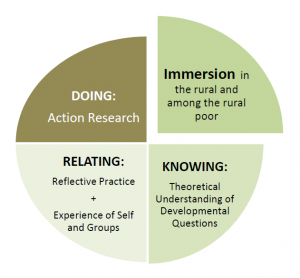

The students (right) were from a new 2 year MPhil course in ‘development practice’ that gives 25 students a combination of conventional academic teaching and 8 months living in rural villages. And the students, judging by the Q&A after my talk, are top notch – not surprising since they get 8 applicants for every place.

It seems like a great idea – students live with families in villages, keep diaries, and get to know the realities of village life. Although other post grads do their time in ‘field work’, that is often more extractive (gathering data for the thesis), which is why Ambedkar calls it ‘immersion’ rather than field work.

The immersion is organized through a partnership with a rural NGO, Pradan, and takes place in some of India’s poorest states. Pradan says the purpose  of the partnership is to ‘draw well-educated youth to take up the challenge of transforming rural India. According to the course organizers,’ the challenge for the course is ‘How to move beyond ‘only writing’ on people’s miseries and ‘only practice’.

of the partnership is to ‘draw well-educated youth to take up the challenge of transforming rural India. According to the course organizers,’ the challenge for the course is ‘How to move beyond ‘only writing’ on people’s miseries and ‘only practice’.

Now I’m never sure when I come across these things whether they are genuinely new, or just new to me, so over to you – anyone heard of other post-grad + rural immersion combos of this kind?

Full details here. And in case you’re wondering, the programme accepts a small number of foreign students.

The most intriguing question that came up in a lively Q&A was ‘is suicide a rich country or poor country problem’.

Subsequent in depth research (aka skimming Wikipedia) throws up a league table (in terms of suicides per 100,000 people), topped by Greenland. Top ten are:

Greenland

South Korea

Lithuania

Guyana

Kazakhstan

Belarus

China

Slovenia

Hungary

Japan

So the conclusion is no, there isn’t an obvious link to the stage of development. Some clear links to post-Soviet countries (Russia’s at number 13, amid a whole cluster of ex Eastern bloc countries). Anti-growthers will take note that a stellar development ‘success story’, South Korea, is at number two – a few years ago, I heard someone from the South Korean statistical office making exactly this point as he explained that Seoul was introducing new metrics to measure wellbeing in an attempt to bridge the gap between official stats and people’s lived experience.

Given the doubts over reporting, I don’t think giving the countries with the lowest rates (several at zero) makes much sense.

Any other patterns?

And here’s a youtube video (only partly in English) that gives you a nice feel for the Ambedkhar approach

November 21, 2013

Math suicide. Off topic but funny.

OK it’s Friday, and this blog has been getting alarmingly worthy and on topic. So here are some subversive/dim/traumatised answers to maths exam questions that had me snorting in a card shop recently. There’s something particularly pleasing about number two, but you may need to look at it a few times. (h/t my mother, who spends far too much time in that shop).

November 20, 2013

What kinds of ‘expert advice’ work in a complex world? Some likes and dislikes

I’ve been talking to a lot of ‘advisers’ in Oxfam, Save the Children and elsewhere recently about what all this complexity stuff means in practice. Advisers are unsung NGO heroes, repositories of wisdom and experience, working closely with partners and staff on the ground. And those staff typically want to know what they should be doing differently. That’s what experts are for, right?

complexity stuff means in practice. Advisers are unsung NGO heroes, repositories of wisdom and experience, working closely with partners and staff on the ground. And those staff typically want to know what they should be doing differently. That’s what experts are for, right?

But if you’re an adviser who has been mugging up on the implications of complexity (see recent posts), this is tricky. How to stop your advice about a systems approach, with its critique of cookie-cutter approaches based on box ticking, best practice, blueprints etc becoming just the latest cookie? ‘Have you done your system/context analysis? Good, now tick the box and move on to stage 2.’

By a very appropriate process of trial and error, here’s where I have got to:

Likes

Asking the right questions: I think you can safely be fairly prescriptive on this. Ask questions about who holds power, who allies with whom, what could be contextual shifts or windows of opportunity that might unblock change. I use a set of guidance questions for analysing change processes that seems to work pretty well. But don’t suggest answers – they have to emerge from the local situation.

Process: Guidance on how to go about designing, evaluating and adapting a change strategy can be useful, e.g. making sure we talk to the people we normally leave out (like faith based organizations, or ex-NGO colleagues with huge accumulated knowledge, who hardly ever get asked in to brief newcomers). But you need to leave doors open to innovation – processes will vary according to context, as will who to talk to.

Case Studies: NGO people prefer stories to formulae, and case studies can liberate the imagination and suggest new approaches.

Signposting, linking and brokering: a lot of the time you are not actually an expert (it’s OK to admit it!), but you know someone who is, or who has been through a similar experience. In practice a lot of advisory work is about linking, rather than directly advising.

Dislikes

Checklists and frameworks: I’m much more dubious about prescribing the content – what a good theory of change looks like, how to strengthen a value chain or empower women etc. OK, this has the advantage of scale and efficiency (tailoring everything to local contexts is very labour intensive), but it is also likely to lead to plans that are either wrong or have big gaps in them

Typologies: I’ve seen the error of my ways on this one. There’s something very exciting about trying to come up with typologies (of types of state, or civil society operating environment, or education systems, or country categories). But as soon as you put them on paper and present them to other people who weren’t involved in drawing them up, creative thought goes out the window as people spend their whole time either trying to decide which box their context fits in, or arguing with the boxes. Hopeless. A compromise is to use typologies in general discussions to expand our general sense of the range of possibilities, but not try and categorize specific pieces of work.

It's perfectly simple.....

Diagrams: I may just be graphically challenged, but I am deeply sceptical of those ornate theory of change diagrams that aid types love to produce. The exercise of devising them in the first place can really stimulate the mental juices about how the system functions, what bits are connected and how etc. But then its probably best to shred it, because when someone new comes in and stares in incomprehension at your ‘change diagram’, their brains will go dead.

But Jo Rowlands, a governance adviser colleague and all-round power and change guru, reckons there is something deeper we need to think about – what kind of people do we need to be to do this kind of work?

‘Seems to me that the most useful thing, in the longer term, is whatever it is that gets this new way of thinking embedded into people’s ways of seeing, thinking and doing. Till that happens, people see it as too much, one more thing in addition to all the rest, or the proverbial straw (that breaks the camel’s back), or too difficult, or whatever the block is.

So the important question is how do we help people make that shift so that it becomes second nature? We probably need to be more concerned with the human beings doing both the programme design and delivery, and how they get the chance to become comfortable with it all – so there’s a serious process/people development need attached that NGOs probably need to take on. Plus, of course, masters courses etc.’

So the good news (if you’re an adviser) is that advisory work is still needed, but it may need to be done very differently in complex systems. Over to the advisory community…..

November 19, 2013

Africa’s tax systems: progress, but what is the next generation of reforms?

Taxation is zipping up the development agenda, but the discussion is often focussed on international aspects such as tax havens or the Robin Hood Tax. Both very important, but arguably, even more important is what happens domestically – are developing country tax systems regressive or progressive? Are they raising enough cash to fund state services? Are they efficient and free of corruption? This absolutely magisterial overview of the state of tax systems in Africa comes from Mick Moore (right), who runs the

International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD). It

was first published by the Africa Research Institute.

Tax. Both very important, but arguably, even more important is what happens domestically – are developing country tax systems regressive or progressive? Are they raising enough cash to fund state services? Are they efficient and free of corruption? This absolutely magisterial overview of the state of tax systems in Africa comes from Mick Moore (right), who runs the

International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD). It

was first published by the Africa Research Institute.

Anglophone countries have led the way in reforming tax administration in Africa, considerably more so than their francophone peers. The reasons for this are numerous. Networks of international tax specialists are based mainly in English-speaking countries. Many of the modern systems that promote best practice within tax authorities were developed in anglophone countries, especially Australia. International donors, and particularly the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), have directly and indirectly promoted a lot of reform of national tax authorities. In fact, this has been one of the success stories of British aid.

A package of reforms has been pursued in anglophone Africa. The most profound change is the amalgamation of revenue collection under a single agency, often referred to as a semi-autonomous revenue authority (SARA). Previously, it was common for tax collection to be dispersed among a number of departments within the Ministry of Finance. For example, different people would be in charge of collecting income tax, VAT and excise taxes. Multiple lines of tax collectors existed, usually not co-operating with one another and each trying to strike private deals with taxpayers. This structure – and practice – still occurs in much of francophone Africa.

SARAs have tended to establish separate offices to deal with large taxpayers in particular. In doing so, they have been able to apportion the necessary skills and expertise to meet the specific requirements of different taxpayer groups. For example, tax authorities need their best auditors and analysts handling the affairs of large companies for the simple reason that they are the source of most revenue. This is both a practical and strategic reform. Specialist departments have also been established to focus on functions such as internal compliance, anti-corruption, personnel and policy.

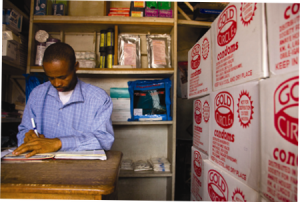

There has been a concerted move to reduce the amount of face-to-face interaction that takes place between taxpayers and tax collectors. This is where corruption takes place. Tax assessments have been separated from physical revenue collection. Payment may take place at large open collection  centres, and the whole process is automated. In some countries, such as Burundi, taxes can be paid through banks. A mobile phone tax payment system – M-Declaration – was launched in Rwanda in September 2012 (see pic) for businesses with an annual turnover of between US$3,000 and US$770,000 per annum.

centres, and the whole process is automated. In some countries, such as Burundi, taxes can be paid through banks. A mobile phone tax payment system – M-Declaration – was launched in Rwanda in September 2012 (see pic) for businesses with an annual turnover of between US$3,000 and US$770,000 per annum.

Many of these revenue collection and administration reforms have also taken place in developed countries in the not-too-distant past. This is partly why donor funding has generally played a positive role in revenue reform in sub-Saharan Africa. The principles and processes behind tax reform in OECD countries apply quite well to developing counties, with important modifications.

In some countries, SARAs have been an effective lever for the stimulation of wider economic reforms. Their creation has often initiated and fuelled important debates about fiscal policy, service delivery and tax exemptions in anglophone African countries. However, SARAs are not a silver bullet – and to some extent have been oversold by donors.

The informal conundrum

SARAs are highly formalised and centralised institutions, usually housed in impressive headquarters in capital cities. They often have strong working relationships with international accountancy firms and donor organisations. Salaries are not tied to government pay scales, and are often akin to those in the private sector. The institutional culture is orientated towards engaging with the private sector and large formal organisations. However, SARAs are seldom suited, or keen, to engage with the vast majority of actual or potential taxpayers in Africa – those involved in the informal economy. This reality has not always been fully recognised by policymakers and donors.

Tax authorities in anglophone Africa have sought to capture more revenue from the informal economy through levies on the presumed income of individual or small enterprise. Presumptive taxation is based on the type of business or economic sector. In francophone Africa, traders or companies are required to purchase a business licence, which is essentially the same process.

The idea of presumptive taxation has existed for some time, although it has not been successful as a revenue generator when applied on a large scale. In most cases, the motivation is to put in place systems that prevent large- and medium-sized companies from presenting themselves as small taxpayers, and therefore claiming exemptions, rather than to raise substantial revenues.

Some tax authorities have been quite innovative in their efforts to capture revenue in the informal economy. Some success has been achieved by working closely with local business and trader organisations. For example, the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) reached an agreement with a union of bus drivers in Accra to collect a daily income tax. In exchange, bus drivers were issued with a sticker and given assurances by the police that they would not be stopped at road blocks and fined for insignificant – or invented – transgressions. In this example, however, the initial success was stymied when the union stopped handing over all the money to the GRA.

when the union stopped handing over all the money to the GRA.

Initiatives like this need to happen more regularly, and on a bigger scale, so that lessons can be learnt and shared. The purpose of taxing the poorer segments of society should not be to generate vast sums of money. The majority of people who work in tax authorities in Africa are aware that most citizens – rich and poor – pay informal taxes of one sort or another to all kinds of people. At border crossings, for example, it is common for there to be three or four government agencies – from customs authorities to environmental standards to border security – extorting fees from traders and businesses. This occurs even more in West Africa than East Africa.

Local government and the golden egg

Taxation plays a vital role in promoting citizenship and reciprocal relations between the taxpayer and government. It is about encouraging people to make a contribution for which they receive something in return. In Africa, local government will need to play an important role in developing sustainable relations of this nature.

Rwanda is one of the few exceptions, where tangible services are directed and delivered at national level. The government in Kigali taxes everything it can, while at the same time ensuring a low level of corruption. The system works because most people are confident that their taxes are paying for public good. Fear may also be a factor. Most African governments do not have the capacity or political will at a national level comparable to that displayed by the state in Rwanda.

Empowering local government in Africa is not easy. Donors such as DFID have traditionally avoided close engagement with sub-national government. It also makes a lot of practical and financial sense of try and reform central revenue collection first. Where competent SARAs now exist, the same amount of effort and resources is required to build the capacity of local authorities to levy certain taxes and provide services. But there is no unanimity or shared conviction regarding this imperative at present.

The skills needed at national and local levels are quite different. Central revenue authorities require the knowledge and expertise to engage effectively with large multinational firms. To tax a telecommunications company effectively, for example, requires considerable industry knowledge and legal expertise. Yet these attributes are almost entirely useless when it comes to setting up a local property tax register.

Most local authorities in Africa have very small budgets, and an extremely limited capacity to collect additional revenues. More politicians would be interested in local authority taxation if the revenues were higher and they could use them to increase their popularity. It is a chicken-and-egg problem. There are two areas where central government could help. Firstly, give local authorities full control over business taxes. The second would be to help build effective systems for property tax.

Property tax is the number one unexploited revenue source in Africa. It is a largely untapped source of funding for sub-national governments. In fact, property tax is underexploited all over the world. In many countries, a colonial system for taxing property is still in place which is very complicated and tends to be weighted in favour of wealthier elites. Most property tax decisions are made locally, where class interests can be particularly powerful. Any sensible tax system would include provisions to revalue properties every five years, especially in rapidly urbanising countries. In reality, political decisions are made not to undertake revaluations for a long time – so property tax is an ever-shrinking proportion of total revenue.

November 18, 2013

Disasters as Opportunities – your thoughts please

Sticking with yesterday’s theme of how our humanitarian work is evolving, one of our more extraordinary Oxfamistas in the Philippines (Lan Mercado, profiled here) has asked a few of us to help her team think through the longer term implications of Supertyphoon Haiyan for our work. I have no idea how she manages to find headspace to think about that in the middle of the emergency response – truly impressive. Anyway I said I would pick your brains as a first step.

Mercado, profiled here) has asked a few of us to help her team think through the longer term implications of Supertyphoon Haiyan for our work. I have no idea how she manages to find headspace to think about that in the middle of the emergency response – truly impressive. Anyway I said I would pick your brains as a first step.

The starting point is that disasters like Haiyan are of course moments of acute human suffering. The urge, indeed expectation, is that organizations like Oxfam should drop everything and do whatever it can to save lives (and don’t worry, we are). This is at the heart of the so-called ‘Humanitarian Imperative’ – an obligation to help everyone in distress, as fast as humanly possible.

But disasters are also ‘political moments’ that can make as well as break movements for change. They highlight corruption and political bias: in Nicaragua, popular outrage at the theft of relief money by the Somoza dictatorship after the earthquake of 1972 was a tipping point in the upsurge of protest that led to the Sandinista Revolution seven years later. Catastrophic famines in Ethiopia in 1985 led to the fall of a dictatorship. Major changes (both good and bad) that would ordinarily take decades can occur in weeks or months. Like wars, natural disasters can transform gender relations as they force women and men to break old ways, and discover new ones.

Peace in Aceh

More recently, the 2004 Asian tsunami prompted a resumption of peace talks between the separatist Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, or GAM) and the Indonesian government, culminating in the signing of a peace agreement in August 2005 that officially brought a 30-year conflict to an end. The historic peace deal was followed quickly by the release of Acehnese political prisoners, the withdrawal of government troops from the province, the decommissioning of rebel-held weapons, and the establishment of a government authority to oversee the reintegration of ex-combatants and co-ordinate assistance for conflict-affected communities. The following year saw a far-reaching autonomy law, giving the long-neglected province control over its natural resources.

Coincidentally, the ODI has a new report out on just this subject. Building Back Better, by Lilianne Fan, explores the implications of the Aceh experience, along with the Myanmar cyclone (2008) and Haiti earthquake (2010). It raises a lot of tricky questions for the aid community about how to respond to wars, natural disasters, or political upheavals.

‘What exactly does ‘better’ look like? Better for whom, where, how? Who decides – agencies, donors, governments, affected communities – and how can these decisions be translated into meaningful programming? What are the implications of investing in build back better if it distracts attention and money away from the urgent and often overwhelming need to feed, treat and shelter people who have nothing but the clothes they stand up in, and for whom ‘better’ may well be a luxury for tomorrow, not today? Is it ethical in humanitarian terms to exploit people’s vulnerability after a disaster to drive social change?’

On the basis of Aceh, Myanmar and Haiti, the paper concludes that BBB is so vague as to make little direct difference, meaning all things to all people, from peace agreements to earthquake proof buildings. But it may have a more subtle value as a framing exercise, directing attention towards the need to think long term, even in an emergency. Especially on issues of power and politics:

‘Build back better is arguably most strategic and meaningful when it is used to bring about or support a transformation of political relations, and

Winds of Change?

[not] when it is ‘merely’ about better materials and technical solutions.’

But the author sits squarely on the fence on whether humanitarian organizations like Oxfam should go there, even if it muddies the humanitarian imperative.

So help us out people. Any advice, references etc on the ethical issues, but also on what Haiyan might mean for progressive social change in the Philippines, or examples of positive change driven by disasters in other countries, and why/how it came about (lots of political economy please!) Especially interested in women’s rights, land rights, social protection, expanding essential services etc.

And just to get the mental juices flowing, I’ve put a poll up – sure my humanitarian colleagues will hate the questions though!

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers

![funny_math_solution_infinity[2]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1385193234i/7094429.jpg)