Duncan Green's Blog, page 204

October 22, 2013

Governance for Development in Africa: Solving Collective Action Problems: Review of an important new book

The last year or so has been a bit quiet in terms of big new books on development, but now they are piling up on my study floor (my usual filing system) – Angus Deaton, Deepak Nayyar, Ben Ramalingam, Nina Munk etc etc. I will review them as soon as I can (or arm-twist better qualified colleagues to do so).

– Angus Deaton, Deepak Nayyar, Ben Ramalingam, Nina Munk etc etc. I will review them as soon as I can (or arm-twist better qualified colleagues to do so).

But I thought I’d start off with a nice short one. Governance for Development in Africa: Solving Collective Action Problems, by David Booth and Diana Cammack, provides a very readable 140 page summary of the ODI’s Africa Power and Politics Programme, bits of which I have previously discussed on this blog. 140 pages is wonderful – you can read it in a morning and feel a glow of satisfaction for the rest of the day. Think there’s a lesson for me somewhere there…..

The book moves from theory to the APPP’s in-depth national fieldwork in Rwanda, Mali, Niger and Uganda and back again, coming to some uncomfortable conclusions.

The book’s underlying conceptual message is that trying to understand (and reform) African politics on the basis of ‘principal-agent’ thinking has been a disaster. Instead, it is much better to think in terms of ‘collective action problems’. The difference is that the first approach ‘assumes that there are principles that want goods to be provided but have difficulty in getting the agents to perform’.

The second approach is ‘more sceptical about the motives that drive action. Many groups and individuals may want the benefits in the form of public or collective goods but will not work to obtain them.’ The art is to find ways to bring all parties together, build trust, and find locally relevant solutions, often built on ‘hybrids’ that mix local traditions with ‘modern’ best practice.

‘If there is a genuinely universal truth about governance for transformation, it is that pre-existing institutions need to be treated as a potential resource for reforms….. ‘The ‘grain’ of popular demand in contemporary Africa is not a desire for ‘traditional’ institutions, but rather for modern state structures that have been adapted to, or infused with, contemporary cultural preferences.’

In comparing what works and what doesn’t (in the quality of maternal health care, but other areas of essential services too), Booth and Cammack identify three explanatory features:

Whether or not the de facto policy regime, including organizational mandates and resource flows, in the sector is internally coherent

The extent to which the national political leadership motivates and disciplines the multiple actors responsible for the quality of provision

The degree to which there is an enabling environment that promotes or at least permits problem-solving at sub-national levels of the delivery system

And they identify plenty of examples where these features are not present: in terms of policy (in)coherence, abolishing user fees in health and education, but not increasing budgets to meet the ensuring boom in usage; using aid money to buy a load of ambulances, without any provision to put petrol in them.

On political discipline, the authors applaud Rwanda’s well-organized health and education services and wider incentive systems for public servants. On the scope for local problem solving, there are plenty of examples of national officials blocking local solutions because they are ‘not policy’ (any comparison with Oxfam sign-off procedures is purely coincidental). Interestingly it finds that when it comes to local flexibility, Rwanda’s government is much more relaxed than the other country case studies. It’s not all central control in Kigali.

There are lots of other plusses in the book – handy chronologies of the shifting fads on politics and governance; merciless debunking of a whole magazine of magic bullets (citizen scorecards, publishing budget details for schools etc).

But the authors, and the APPP generally, really struggle on the ‘so whats’. The finding on hybrid solutions is significant and useful, but on the national scale, their conclusion is that some kinds of authoritarian regimes can ‘do a Rwanda’, like Ethiopia, ‘when, and perhaps only when, they experience a sharp shock and/or a sustained threat to their existence.’ But, apart from acting promptly in the wake of the next genocide or famine, what does that mean for those wishing to support Africa’s path to good governance? It’s not that clear and to be honest, I found Matt Andrews’ proposals, which cover similar ground, more useful.

But the authors, and the APPP generally, really struggle on the ‘so whats’. The finding on hybrid solutions is significant and useful, but on the national scale, their conclusion is that some kinds of authoritarian regimes can ‘do a Rwanda’, like Ethiopia, ‘when, and perhaps only when, they experience a sharp shock and/or a sustained threat to their existence.’ But, apart from acting promptly in the wake of the next genocide or famine, what does that mean for those wishing to support Africa’s path to good governance? It’s not that clear and to be honest, I found Matt Andrews’ proposals, which cover similar ground, more useful.

The other real struggle is over aid. The authors’ analysis is overwhelmingly condemnatory – the ‘biggest problem’ in policy coherence is wave after wave of externally imposed half-finished reforms, which have made a terrible mess of African governments (and they weren’t that hot to begin with). Reminds me a bit of UK education ministers’ endless tinkering……

But, unsurprisingly perhaps from authors rather dependent on DFID’s shilling, they pull their punches and fail to reach the logical conclusion that less aid is what is required. Instead, they want aid donors to become knowledge-based thinktanks, or to outsource more work as ‘arm’s length aid’.

My other problem with the book is its jarring tone, especially its rather lazy dismissal of both democracy and citizen action. Here’s a sample:

‘Full blown capitalism creates the social structures and organizational capabilities that lead to democratic governance, not the other way around…. Real democracy is not an available option for most of Africa.’

‘Elite level action issues are the most fundamental development issue for most African countries….. the masses are not significant players on their own behalf’ – the role of citizens thus seems to be reduced to that of political pawns or grateful consumers.

Similarly, they are scornful of aid initiatives ‘based on the associational model’.

Not surprisingly, I disagree with a lot of this. They equate supporting citizenship with bunging loads of money at civil society organizations (‘turning them into NGOs’), which I would agree is probably self-defeating, but suggests they are a bit out of touch both with how to support citizen action, and its huge potential. They fail to see the potential role of civil society in identifying and amplifying the problems around which collective problem solving needs to take place. And they downplay the intrinsic value of rights, including democratic rights.

But if you can get past the tone, which is worse in the earlier sections of the book, the conclusion is excellent, and fits exactly with many of the arguments on this blog.

‘External actors have a duty to contribute to the creation of an enabling environment for local problem-solving. But this is challenging. It requires the intervening agent to have the flexibility, learning capacity and intellectual modesty to play a facilitation role…. Several of these qualities are in short supply in the development business.’ (ouch!)

And here (putting their call for ‘intellectual modesty’ to one side) is the final paragraph:

‘We would give priority to two practical steps. One is a robust commitment from the international NGO community to Duncan Green’s ‘convening and brokering’ as opposed to ‘delivering stuff’. The other is greater use of arm’s length assistance- funding of organizations that can do a better job of facilitating governance for development along the lines outlined here.’

Well obviously, I’m going to agree with that, right?

October 21, 2013

What use is a theory of change? 6 benefits, and some things to avoid.

Whether in the back of a 4×4 in Tanzania, or in seminar rooms in Oxfam house, I seem to spend an increasing amount of my time discussing theories of

Not recommended.....

change. Oxfamers seem both intrigued and puzzled – what are they? What are they for? The answers aren’t simple and, as social scientists like to say, they are contested. But here’s what I currently think.

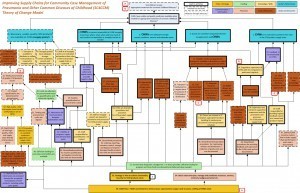

What is a theory of change? A way of working and thinking, and a set of questions. Aerobics for the imagination – not a form to fill in (and most definitely not logframes on steroids). Nor is it a typology or (a personal bête noire) an insanely complicated diagram that no-one coming after you can understand (see example, right). More here.

How does (or should) a good theory of change improve our work (or ‘add value’ as the marketing wannabes insist on saying)?

It encourages deep observation of the system – how power is distributed; how decisions are made; what are the coalitions for and against any given change; how is change likely to happen in this system. The longer you can refrain from the jump to ‘so what do we do’, the more likely you are to come up with some good ideas to test.

It makes you think far more about critical junctures/windows of opportunity as an essential component of any change process. These are almost uniformly absent from our pre-intervention plans, and yet when you watch a change process taking place, they often play a primary role. They are often then airbrushed out again in the subsequent rewriting of history.

It highlights the importance of working with ‘non-usual suspects’, brokering discussions between groups who may initially have low levels of trust, (even hostility), but who can come together and find new answers to old problems. In Oxfam, faith groups and traditional leaders often get overlooked, but there are many others (discussing potential places of discussion on social issues in rural Tanzania we came up with kiosk owners, soccer fans, women attending hairdressing salons and loads more).

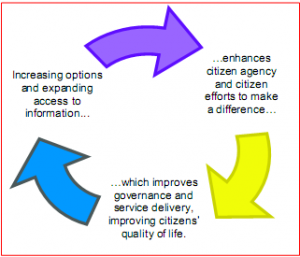

It helps you identify and open up the ‘black boxes’ in our thinking – intellectual leaps and assumptions, like the recent discussion with Twaweza on their initial assumption that access to information would be enough to trigger citizen action.

It shifts the emphasis away from a huge exercise in pre-intervention planning, followed by a long and unremitting process of implementation (with a mid and end term evaluation thrown in). Instead we are into something more experimental and iterative – come up with some initial hypotheses to test, but the smart thinking will be around taking stock and correcting courses as the project evolves. This is true because our understanding of a context improves as the project evolves, requiring adaptation (Oxfam programmes such as Raising Her Voice have really benefited from a theory of change discussion a couple of years into their work), but also because high levels of staff turnover mean that in any case, we need to constantly re-learn the theory of change behind a programme.

Linked to this, a good theory of change should shift the centre of intellectual engagement from monitoring to learning (see Claire Hutchings’ recent post).

All of these points apply both to programmes that are already under way, as well as to ‘clean sheet’ discussions on new work.

All of these points apply both to programmes that are already under way, as well as to ‘clean sheet’ discussions on new work.

Convinced?

October 20, 2013

Some feelgood for Monday morning. 500 Ugandan women entrepreneurs lipsynching to Jessie J.

Can’t find that much info about it, but this video was made by a Dutch NGO called SYPO to publicise its microfinance crowdsourcing site, microbanker.com. There’s also a couple of youtube clips of the making of the video and the afterparty - which looks a lot of fun. The afterparty clip eased a few qualms (do all women speak enough English to fully understand the lyrics? Do 500 entrepreneurs really think ‘it’s not about the price tag’……) (h/t Mary Matheson)

October 17, 2013

When we (rigorously) measure effectiveness, do we want accountability or learning? Update and dilemmas from an Oxfam experiment.

Claire Hutchings, Oxfam’s Global MEL Advisor, brings updates us on an interesting experiment in measuring impact – randomized ‘effectiveness  reviews’.

reviews’.

For the last two years, Oxfam Great Britain has been trying to get better at understanding and communicating the effectiveness of its work. With a global portfolio of over 250 programmes and 1200 associated projects in more than 55 countries on everything from farming to gender justice – grappling with the scale, breadth, and complexity of this work has been the challenge. So how are we doing? Time for an update on where we’ve got to, with apologies in advance for a hefty dollop of evaluation geek-speak.

After much discussion and thought, we developed our Global Performance Framework (GPF). The GPF is comprised of two main components. The first is Global Output Reporting, where output data are aggregated annually under six thematic headings to give us an overall sense of the scope and scale of our work.

Secondly, in addition to the headline numbers, we need to drill down on the effectiveness question, which we’ve been doing via rigorous evaluations of random samples of mature projects. These evaluations – known as ‘Effectiveness Reviews’ – were launched in 2011/12 and today we’re releasing the first batch of effectiveness reviews from 2012/13, covering everything from strengthening women’s leadership in Nigerian agriculture to building sustainable livelihoods for Vietnam’s ethnic minorities.

The measurement approaches have developed quite a lot from the first year, so let’s start there. For the reviews of our ‘large n’ interventions (i.e. those targeting large numbers of people directly), we have been adapting the approach used by OPHI for the measurement of complex constructs, to measure both women’s empowerment and resilience. This has improved our overall measures.

For example, our initial women’s empowerment reviews primarily considered women’s influence in household and community decision-making. This has now been expanded to cover dimensions such as personal freedom, self-perception and support from social and institutional networks. Our resilience framework has expanded to include food security and dietary diversity.

We’ve already written about the challenges and lessons learnt from ‘small n’ interventions (where there are too few units to allow for tests of statistical differences – such as advocacy and campaigns), but essentially we continue to learn about how best to ensure consistency in application of the process tracing protocol, and how to answer the question ‘do we have sufficient evidence to draw credible conclusions?’ We also experimented with bringing outcome harvesting and process tracing together in a review of the Chukua Hatua programme in Tanzania.

We’ve smartened up the benchmarks for the humanitarian indicator toolkit and changed some of the standards we’re considering (contingency planning is out, replaced by resilience and preparedness.) And have piloted an Effectiveness Review on our own accountability (report out soon), bringing in an external reviewer to look, in depth, at the leadership, systems and practices of OGB and partner staff to reach conclusions on the ‘evidence’ available on the degree to which Oxfam’s work meets its own standards for accountability at project level.

We’ve smartened up the benchmarks for the humanitarian indicator toolkit and changed some of the standards we’re considering (contingency planning is out, replaced by resilience and preparedness.) And have piloted an Effectiveness Review on our own accountability (report out soon), bringing in an external reviewer to look, in depth, at the leadership, systems and practices of OGB and partner staff to reach conclusions on the ‘evidence’ available on the degree to which Oxfam’s work meets its own standards for accountability at project level.

We’re waiting to finalise the full set of reports – the final batch will be published in November/December – so it’s premature to start presenting summary findings, but I’m keen to dive into what I think remains one of the key outstanding challenges of this exercise: learning. The two key drivers for the GPF – accountability and learning – are often competing for attention and arguably require different approaches to the design, implementation and use of evaluations.

At the end of the first year, I think it’s fair to say that the consensus was that the GPF, and the effectiveness reviews in particular, were too heavily weighted towards ‘upward’ and ‘outward’ accountability (to donors and northern publics). So the challenge has been how to reorient them to better serve a learning agenda.

There are some noteworthy examples of where the reviews are contributing to project level learning. In Honduras, for example, the results of a review of community banks were disseminated to people in both intervention and comparison communities. In the “comparison” municipality, Oxfam’s partner organisation highlighted some points that the local government and community banks there could learn from those in the project area; in Tanzania, the effectiveness review of Chukua Hatua is being used to develop phase 3 of the programme; in the Philippines the Oxfam team has decided to use the effectiveness review as a baseline for the next phase of the project, and conduct the exercise again themselves in 2 years time.

At an organisational level, we’re starting to pull out thematic learning, as well as lessons on the design and implementatin of interventions. We’re also seeing an increasing appetite for including impact assessments in the initial programme design (rather than as an after-thought). For all that, though, I think it’s fair to say that learning from the effectiveness reviews remains a challenge (that means a problem, btw). Let’s talk through some of the main sticking points (in case any of you out there can help).

As with last year, there is a tension over the choice of projects: randomly selecting them at ‘the centre’ avoids cherry picking and arguably gives us a more honest picture of effectiveness, but it doesn’t always mesh with what countries and regions most want to learn. Evaluative questions often can’t be fully explored until an intervention is mature, but by then the intervention may no longer be topical and the questions may have moved on. Without a continuing programme, it may feel too late for evaluation to feed into learning” (it’s not, btw, there’s lots that we can draw into current and future programming).

a more honest picture of effectiveness, but it doesn’t always mesh with what countries and regions most want to learn. Evaluative questions often can’t be fully explored until an intervention is mature, but by then the intervention may no longer be topical and the questions may have moved on. Without a continuing programme, it may feel too late for evaluation to feed into learning” (it’s not, btw, there’s lots that we can draw into current and future programming).

It is also, crucially, about ownership – do the evaluation questions being asked by the effectiveness reviews sufficiently mirror the project’s own theories of change? Do project teams feel engaged by those questions, and therefore able to respond to the findings?

The evaluation designs for the ‘large n’ interventions in particular are complex and often unfamiliar to programme staff, and may fail to ‘tell the story’ in ways that are meaningful to the team’s broader understanding of their operating environment. And while they help us to answer the question of whether or not our programme has had an impact, they often cannot explain why that is the case.

We’re working to address some of these challenges. We have revised our sampling criteria to ensure we are selecting larger, more mature projects to increase the relevance to country staff. We are undertaking more qualitative research (or linking up with already-planned qualitative evaluations) to support learning.

We are creating more chances for project teams to engage with and inform the evaluations, to more thoroughly unpack their theory of change and build understanding and ownership of the questions that the reviews are trying to answer – recognising that we need to get this up front, to ensure teams are able and willing to act on the findings.

We’re also doing more to support learning from the reviews – undertaking more follow up research, working with project teams to think through how they might act on recommendations, and at an organisational level working with the relevant thematic advisors to feed learning from the reviews into future programming. And from all the reviews, there is a lot that we can learn about about how to improve programme design and implementation more broadly.

But, at the core, I still worry that there is an inherent tension between organisational accountability and programme learning. Are they compatible/achievable with the same tool (has anyone ever actually killed two birds with one stone?), and if so, how can an organisation get the balance right? And if not, where do we draw the line between these two agendas?

October 16, 2013

The New Global Inequality Debate: “A Symbol of Our Struggle against Reality”?

Guest post from Paul O’Brien, Oxfam America’s

Vice President for Policy and Campaigns

This blog will make more sense if you watch at least a few seconds of this Monty Python skit first.

Monty Python haunts me. Too close to the bone if you work in a rights-based organization. When I got into development work in the 1990’s, the UN and some NGOs were getting their heads around “rights based programming”. We re-described “needs” as “rights”; talked about “beneficiaries” as “rights bearers”, slammed our fists on the table, and, for the most part, went back to business as usual. I now evoke “Monty Python” at Oxfam to urge colleagues never to do just that.

Here’s what I realized: most good programme staff already understood the rights principles that mattered; the bad ones just learned to spin. I came to think a rights lens was not useful for engaging or describing rights victims, but could help to push practitioners to identify perpetrators, and work out how to hold them to account even if it meant risking our programming or our relationships with elites. That work was different and difficult and separated the real rights-based organizations from the PR machines. Some organizations ultimately backed away. Others radically changed their business model. I joined Oxfam because I believed it was serious about holding the powerful accountable.

sharing prosperity?

But now I’m getting nervous again—I listen to some of the new thinking on “inequality”, and hear Monty Python. Look at how the UN and World Bank are talking about inequality. The authors of the UN’s High Level Panel Post 2015 report tried to hardwire inequality into the new MDG goals by committing to “leave no one behind.” But the draft goals only focus on one side of the inequality equation: on poverty, ignoring wealth (such as the $240 billion amassed by the world’s richest 100 people last year). The World Bank proudly commits to “shared prosperity” for the bottom 40 percent in its forthcoming strategy. But sharing by whom? Until they answer that question, Oxfam and others will keep challenging them “to reduce disparities between the top and bottom”.

Why does this matter? Because reframing the poor as “the unequal poor” while shutting off discussions about the obligations of the wealthy will waste a huge amount of development thinking over the coming two years, and change very little. It’s not as if the last UN strategy was “let’s make sure to leave a few folks behind”. Or the World Bank used to promote “Prosperity Reduction Strategies” for the poor.

My test for whether inequality discussions are adding value or are just “a symbol of our struggle against reality” (h/t John Cleese) is whether we find a fresh and useful way to talk about unfair wealth, not unequal poverty.

Here is an interesting debate: Is there a quantity of wealth which is just unfair or is it only a certain type of wealth? Africa’s richest man has made $16 billion while 80 million of his fellow Nigerians survive on less than $2 a day. Africa’s richest woman has amassed $3 billion while most of her Angolan compatriots live in extreme poverty. Is it the level of wealth that we should be worried about or the fact that it was made in two of the world’s most corrupt countries? Are we OK that Bill Gates is worth $72 billion because he got it cleanly and gives most of it away (some of it to Oxfam)? The answer to those questions will change how we measure inequality, what research we do, what policy solutions we seek and how we build or join movements for change. That’s the debate I want to be part of.

See also Ricardo Fuentes v World Bank on inequality

And here’s Paul’s inequality rant at a recent CGD meeting, which triggered this post

October 15, 2013

Should you keep innovating as a programme matures? Dilemmas from (another) ground-breaking accountability programme in Tanzania

Certain countries seem to produce more than their share of great programmes. Vietnam is one, and Tanzania appears to be another. After the much-blogged-on Twaweza workshop in Tanzania last week, I headed up North to visit the Chukua Hatua accountability programme. It’s one of my favourites among Oxfam’s governance work, not least because it has a really top notch theory of change (keep clicking) I often get asked for a good real life practical example of a ToC – in governance work, this is the best I’ve seen.

of my favourites among Oxfam’s governance work, not least because it has a really top notch theory of change (keep clicking) I often get asked for a good real life practical example of a ToC – in governance work, this is the best I’ve seen.

Over a series of conversations with Oxfam staff and partners, village activists, officials and others, one intriguing issue struck me: even if you start out as innovative, what happens next?

Let me explain. Chukua Hatua started out with a really interesting theory of change – adopt an evolutionary approach of variation-selection-amplification. That meant trying out lots of things in phase 1 (2010/11), then sifting through the results to identify the most successful variant(s) and scaling that up.

The variant that stood out was that of animation: training farmers selected by their communities to become animators – entrepreneurial, networked activists identifying problems in their communities and bringing people together (both villagers and those in power) to find solutions. This has worked brilliantly, so phase 2 (2012/13) has scaled that up.

Chukua Hatua is now largely synonymous with animation. Our partners have trained 400 animators, many of whom have in turn trained up or simply inspired lots of others. Other parts of phase 2 included doing more ‘supply side’ – training 200 ‘village chairpersons’ and 160 village councillors (all elected by their villages and unpaid).

So far, so inspiring, but there’s a catch. Or rather several catches:

First, you don’t just train animators and wish them well – they want support and it would be unethical to say ‘sorry, got to innovate’ and leave them in the lurch. Sometimes they push hard enough to get into trouble, and then you’re into lawyers and courts. Plus you want to know how they’re doing – lots of monitoring going on. So as time goes on, and the numbers grow, the effort of servicing the project’s successes grows, and starts to squeeze out the time for trying out new stuff.

Second, the focus on training has become a bit of a bottleneck: would-be activists feel that unless they have received the magic ingredient, they can’t claim to be ‘real’ animators. Would it be possible to get past this either by having a ‘starter pack’ that provides some ideas and confers recognition even before training starts, or slimming down the training into a basic social franchising-type package that can easily be reproduced and spread by animators to new recruits?

Second, the focus on training has become a bit of a bottleneck: would-be activists feel that unless they have received the magic ingredient, they can’t claim to be ‘real’ animators. Would it be possible to get past this either by having a ‘starter pack’ that provides some ideas and confers recognition even before training starts, or slimming down the training into a basic social franchising-type package that can easily be reproduced and spread by animators to new recruits?

Third, a practical point, as you near the end of the project, starting big new innovative approaches becomes less sensible – there isn’t time to complete them. Learning as much as you can about the successes and failures of the existing work starts to take priority, as does laying the foundations for a follow up project (it would be tragic if something as exciting as Chukua Hatua ground to a halt at the end of next year when the 3rd and final phase of its current incarnation ends).

Fourth, our particular model of animation has got a bit stuck in the ‘farmer animator’ mode, with a focus on collective action and a fair degree of confrontation. But that model might not work for other kinds of people. As we travelled and talked, we become increasingly aware of other potential sources of animators, based on the many nodes of social capital in any village: savings groups, faith groups, kiosks, choirs, ‘sungusungu’ militia, football fans (big crowds for premiership games, and far too many Arsenal fans for my liking), hair salons. Plus the big convening moments in a village’s life – celebrations, funerals, festivals, sports competitions. There’s a lot to work with, and I’m sure a careful observation of a few villages would reveal many more.

So in good evolutionary style, maybe we should now seek to encourage variation within the successful animation model. Maybe find Christian and Muslim partners to develop faith-based animation models, or something different for savings groups or soccer fans? Different approaches would also include more recognition of the less confrontational forms of action – raising money for good causes, organizing events etc, which can produce some easy wins and build momentum, as people start to see that taking action can produce tangible results.

More broadly, is the urge to stay innovative even as a project matures a bit like dad dancing – defying the natural process of aging, trying to stay  forever young and hip, however silly you look? Or should the nature of innovation change, or maybe it should even be accepted that mature projects are less innovative?

forever young and hip, however silly you look? Or should the nature of innovation change, or maybe it should even be accepted that mature projects are less innovative?

Not that the animators are waiting for us to decide these things – lots are coming up with new approaches off their own initiative (for example peopledon’t want to attend official village meetings, because they are so dull and procedural, so some animators have started organizing much more lively village dialogues, promoting pique and envy among officials at the turnout and participation). As time goes on, an increasing part of Chukua Hatua’s effort may need to be devoted to ‘positive deviance’ work – watching how the animators do their jobs, and spotting their innovations, especially if they can be replicated elsewhere.

There’s an exciting element of losing control there, though it may make life a bit stickier for the evaluators trying to prove attribution (sorry guys).

And here’s a 14m video explaining the original idea

October 14, 2013

Blogging about development: some tips for NGOs and would-be bloggers

Blogging about blogging – the ultimate in cyber-narcissism. Last week Twaweza invited me in to their office to pick my brains on their impending launch into the blogosphere, so I thought I’d turn my notes into a quick post (and cribsheet for future talks). I’ll try to avoid duplication with my last post on ‘why blog’ – this is more about the ‘how’ and is aimed at NGOs and the people who work for them.

into the blogosphere, so I thought I’d turn my notes into a quick post (and cribsheet for future talks). I’ll try to avoid duplication with my last post on ‘why blog’ – this is more about the ‘how’ and is aimed at NGOs and the people who work for them.

First it’s worth remembering that talking about ‘blogging’ as a single thing is like talking about ‘writing books’ – pretty unhelpful. The largest number of different kinds of blog I have yet seen described in one place is 52 – worth a skim.

On with the show, first some general organizational advice:

Who should blog in your organization? A good place to start is to find out who is already blogging, in a private capacity (one hyperactive Twaweza staffer confessed to running 5 separate blogs in her spare time….). They are the ones who actually like the medium. Forcing reluctant staff to blog is very unlikely to produce anything worthwhile.

People v institutions: NGOs have a default preference for anonymity. The authorship of papers, if acknowledged at all, is buried in the small print. Egotism is anathema. All too often sentences begin with ‘Oxfam believes’…… Well it doesn’t work for blogging – personality, a face, a voice, doubt, ambiguity etc are infinitely preferable to finger-wagging corporate press releases full of ‘must’ and ‘should’. If you don’t have egomaniacs willing and able to post several times a week, think of a stable of authors with names, faces etc, along the lines of Global Dashboard.

Sign off: A big issue. Blogs need to be authentic (no ghost writing permitted, ever), personal and quirky, which may mean departing from agreed institutional messaging, whether in tone or content. On the other hand, letting your in-house nutters off the leash could do serious damage to your reputation, get you chucked out of entire countries etc. How to manage the risk? One option, which I followed with FP2P, was a probation period, during which all posts have to be signed off in advance. After a few months, if you haven’t messed up, you move from ‘asking permission’ to occasionally ‘asking forgiveness’ when you overstep the mark. Do so too often, and you will get closed down; don’t ever do it, and your blog is probably too boring.

And now some advice to individual bloggers:

Style: Try and write like you talk (one of the participants in the Twaweza seminar said ‘wow, you talk just like you blog!’ – had to put them straight on that). It’s hard to keep simultaneously in your mind the often complex and subtle message you want to convey and the likely level of interest and knowledge of your intended reader, but navigating that cognitive dissonance is essential for any writer. It’s also surprisingly difficult to unlearn all the  constipated styles of non-communication we accumulate in academia, NGO campaigning etc, but well worth it, if you want to blog for (roughly) normal people. And this does not mean patronise, talk down etc – explaining something to an intelligent, but non-aid-mafia friend is not a bad image to keep in your head. As in conversation, humour is great if it comes naturally.

constipated styles of non-communication we accumulate in academia, NGO campaigning etc, but well worth it, if you want to blog for (roughly) normal people. And this does not mean patronise, talk down etc – explaining something to an intelligent, but non-aid-mafia friend is not a bad image to keep in your head. As in conversation, humour is great if it comes naturally.

Format: Standard blog advice here – lots of links, graphics, videos etc to break up the text. Try and keep posts short and mobile phone-readable (I’m a total failure on that).

The Title: I often rewrite the title several times – it’s crucial. When I open up my RSS feed in the morning, there are often about 100 entries, all giving only the title of the blog or article concerned. I click on maybe 10, based entirely on the title. You don’t have to use linkbait terms, but you do have to pique your intended reader’s interest – questions are good, as are odd juxtapositions. Predictable/worthy NGO speak is not. Who’s going to click on something that says ‘Good Governance is a really important issue’?

Promotion: This is really difficult, especially at the beginning before traffic builds up, when a lot of stamina is required to establish a blog without much in the way of reward. Blogging works by word of mouth and recommendation, so there are some pretty sharp limits to more traditional marketing. Twitter is good (in moderation – don’t tweet a link to your blog more than twice). I’m not sure getting onto other people’s blogrolls does much good – any evidence on that? If you have the time, leave comments on relevant posts on more visited blogs, with links back to your own posts. People always love a fight, so organize debates etc. Both twitter and blogging are like constant streams of information – think when people in your target timezone are likely to dip in, and schedule accordingly (I use tweetdeck to schedule tweets for UK lunchtime/US early morning)

Polls: I’m surprised how few blogs run polls to get reader input – it’s fun, interactive, and informative (I’m regularly surprised by the poll results)

Guest posts: Tricky issue this. It’s great to make the platform available to would-be bloggers in your organization or beyond, who can improve the quality, fill in gaps, add variety etc at the same time as learning the trade. Here’s my standard guidance to would-be guest bloggers (keep clicking). On the other hand, too many guest bloggers and you risk diluting the personality of the blog. I’m struggling with this at the minute, as I am getting 3 or 4 offers of guest posts per day, many of them really interesting. Any advice?

OK I could go on (and doubtless will do at some point), but have already massively overshot the correct length for a blog, so will stop there.

Previous posts: Blogging at the World Bank; (not) blogging at the UN; FP2P Reader Survey; Why do NGOs find blogging so hard? Is blogging a guy thing? Evidence on impact of economics blogs.

A new consensus on universal health coverage, the threat posed by health insurance schemes and some bizarre conference dancing

Oxfam health policy adviser Ceri Averill ponders the new consensus on Universal Health Coverage and the potential threat posed by health insurance schemes

health insurance schemes

It has got to be one of the more memorable and surreal ends to a conference I’ve ever seen. After four days of serious policy discussions about health financing and universal health coverage (aka ‘UHC’), the 2012 Prince Mahidol Awards Conference in Bangkok closed with the great and the good of the global health community on the dance floor, suited and booted and boogeying away to the tune of YMCA, adapted to fit the words “We believe in U H C” (try it – it does actually work!). Health ministers, government officials, World Bank staff, academics, and civil society activists were all there.

As I watched the scene unfold I found myself wondering what this meant. Was it really possible for people who have disagreed for years on so many issues to unite under the umbrella of UHC? (as it happens there really was a dance troop on stage twirling UHC umbrellas). And if we really do all “believe in UHC” are we understanding it to mean the same thing?

Universal health coverage has risen quickly to the top of the global health agenda. The Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) Margaret Chan has described it as ‘the most powerful concept that public health has to offer’, and in December last year the United Nations General Assembly adopted a landmark resolution on UHC. It is a simple but inspiring concept – the idea that all people should have access to health care without fear of being pushed into poverty. As the momentum builds, a diverse range of actors – including governments, multilateral agencies, donors, private foundations, academics, and civil society organizations – are uniting beneath the UHC banner.

On one hand I’m excited and encouraged by the growing enthusiasm. UHC has the potential to transform the lives of millions of people by bringing life-saving health care to those who need it most. Making health care available to all is in the spirit of Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and it is the continuation of a long struggle for “health for all”, popularized since the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978. It is also the founding principle on which an institution I have known and loved my whole life – the UK’s National Health Service – was built.

On the other hand, I see two major risks. The first is that UHC is reduced to a catchy sound bite and so comes to mean anything and everything, but ultimately nothing. Jim Kim, President of the World Bank Group said recently, ‘All of us together must prevent “universal coverage” from ending up as a toothless slogan’ – I couldn’t agree more.

On the other hand, I see two major risks. The first is that UHC is reduced to a catchy sound bite and so comes to mean anything and everything, but ultimately nothing. Jim Kim, President of the World Bank Group said recently, ‘All of us together must prevent “universal coverage” from ending up as a toothless slogan’ – I couldn’t agree more.

The second more serious risk is that the UHC agenda becomes hijacked and business as usual prevails. Already many different things are being done in its name, not all of which live up to the core principles and objectives set out in the landmark WHO 2010 World Health Report on UHC.

Last week Oxfam published a new report warning that health insurance schemes, touted by some governments and donors as ‘the way’ to achieve UHC in low- and middle- income countries, are excluding the majority of people and leaving the poor behind. In many cases insurance schemes are actually driving up inequality by prioritizing already advantaged groups who work in the formal sector. The report argues that rather than focus efforts on collecting insurance premiums from people who are too poor to pay them, governments should look to learn the lessons from successful UHC countries and prioritize spending on health from general taxation – either on its own or pooled with formal sector payroll taxes and international aid.

Although UHC is not a ‘one size fits all’ journey and governments will need to develop approaches that fit the social, economic, and political contexts of their countries, the lack of a UHC blueprint does not mean that ‘anything goes’. Getting UHC (with clear equity targets and indicators that disaggregate data) into whatever succeeds the MDGs is going to be vital in order to ensure that it doesn’t end up either as a ‘toothless slogan’ or hijacked by an agenda that undermines the core UHC principles of universality, equity and social solidarity.

The risks are real, but they are not insurmountable. Ultimately the momentum for UHC presents an opportunity for the global health community to finally deliver on the right to health for all. Politicians now have to show that they are willing to take action, civil society must unite to demand change, and development partners need to step up to support them. At the same time we all have a responsibility to halt unproven and risky policies that threaten to derail progress.

Needless to say, on that afternoon in Bangkok it wasn’t long before I too made my way to the dance floor, where I found myself flailing my arms in the air and singing along to the catchy tune. I never did quite work out how to do the H though.

See here for more on the health insurance report from Ceri’s co author, Anna Marriott

October 10, 2013

Last word to Twaweza: Varja Lipovsek and Rakesh Rajani on How to Keep the Ambition and Complexity, Be Less Fuzzy and Get More Traction

Twaweza’s Varja Lipovsek, (Learning, Monitoring & Evaluation Manager) and Rakesh Rajani (Head), respond to this week’s

Twaweza’s Varja Lipovsek, (Learning, Monitoring & Evaluation Manager) and Rakesh Rajani (Head), respond to this week’s  series of posts on their organization’s big rethink.

series of posts on their organization’s big rethink.

That Duncan Green dedicated three posts on Twaweza’s ‘strategic pivot’ may signal that our work and theory of change are in real trouble, but we prefer to take it as a sign that these issues are of interest to many people working on transparency, accountability and citizen-driven change. His posts follow a terrific two day evaluation meeting. Here are a few clarifications and takeaways.

Spiritual matters first. We very much believe that Twaweza’s soul remains intact: we want to contribute towards change in complex systems in East Africa, by promoting and enabling citizens to be active agents and shape their lives. Our experience over the past four years has made us question much of how we ‘do’ citizen agency, but we are not quite throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

For example, in our original approach we didn’t want to be prescriptive about citizen action; we wanted to expand choices and leave it up to people to decide, what we called an ‘open architecture’ approach to social change. Sounds good; problem is that it doesn’t work so well in practice and the evidence of successful change suggests a need for less openness and more focus. New evidence about the bandwidth that poor people have to make good decisions provides useful insights on what one can realistically expect people to do.

Moreover, we have learned that we need to better articulate what we mean by citizen action – including private v public and individual v collective. We take to heart the call from the evaluators meeting (and Duncan’s blog) to both analyze what kind of action we have been promoting, and want to promote in the future, and whether we prioritize some above others, including our stance on the desirability of voice or exit.

In essence, this is a move away from an unexplained “magic sauce” model where we feed some inputs (i.e. information) into a complex system, hope  that the (self-selecting, undifferentiated) citizens will stir it themselves, and voila – a big outcome (such as increased citizen monitoring of services, and improved service delivery) will somehow pop out on the other end.

that the (self-selecting, undifferentiated) citizens will stir it themselves, and voila – a big outcome (such as increased citizen monitoring of services, and improved service delivery) will somehow pop out on the other end.

Precisely because the processes and systems we seek to influence are nuanced, multi-layered, and steeped in politics (from local to national to international), and precisely because we no longer believe there is a single recipe to the magic sauce, we need to do a number of things with greater clarity and thought.

Second, we need to understand the systems in which we work much better, to map them out; to do the kind of “3i” analysis to which Duncan referred (others call it political economy analysis). Part of this is also just simply doing our homework: engaging more with both the theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence from within the transparency and accountability field, but also wider such as in public health, economics and political science. We know that experiences are not automatically portable across contexts, but reading deeply can help us think sharply.

Third, we accept that our original Manichean emphasis on ‘officialdom’ vs. ‘lived reality’ (government vs. people, formal governance vs. hustling) is neither an accurate representation of reality, nor a helpful way of shaping action. Enabling citizen agency means maneuvering precisely in that space between supply and demand, between citizens and state.

Third, we accept that our original Manichean emphasis on ‘officialdom’ vs. ‘lived reality’ (government vs. people, formal governance vs. hustling) is neither an accurate representation of reality, nor a helpful way of shaping action. Enabling citizen agency means maneuvering precisely in that space between supply and demand, between citizens and state.

However, in our East African context, confidence in engaging with the formal sectors has been eroded by years of unresponsive and corrupt systems, so much so that even when there is a genuine opportunity to engage or provide feedback, citizens often don’t do so. It’s critical for us to understand the barriers and motivators for citizens to act– but equally, we need to understand the barriers and motivators from the system/sector side, and look for opportunities where the two can connect to get things done.

Duncan’s point on taking advantage of critical junctures is well taken; and although we did not mention it during the meeting, we have been responding and engaging with topical and political issues, particularly in Tanzania, for example in relation to the crisis in education, the new phone card SIM tax, and pricing of malaria medicine.

Fourth, we must be wiser about where we think we can contribute the most, while at the same time take risks and foster innovation. This last point is important. In seeking to engage with complex systems in a complex world, we need to do two things simultaneously: keep a hard line on a handful of hypotheses (both in terms of implementation and measurement – next point), as well as be nimble in experimenting with innovative approaches.

Part of this is what we are calling the “positive deviants” lab; part is the “programming lab”. The former will be an initiative to find, understand and – when possible –replicate examples of citizen action and engagement across East Africa. The latter will be an effort by us and our implementing partners to be more nimble and experimental in identifying new directions and implementation models, setting up tighter feedback loops between recipients and implementers. As our Advisory Board member Lant Pritchett tells us, you never get it right the first time. So the point is not to design the best intervention, but to develop intelligent antenna to learn and adapt fast.

Fifth, we recognize a real tension between the desire for quality, thoughtfulness and iteration on the one hand and scale on the other. The last thing we want to do is create a set of boutique programs or our own Millennium Development Village. The East African landscape is littered with thousands of pilots that went nowhere. But we think there is a way to do things in a way that has scale built in from the beginning; ingredients include simplicity (to allow easier understanding and replication), a political economy analysis of the drivers and levers of change, and keen attention to incentives and crafting winning coalitions.

The upshot of all this is to privilege learning in the organizational DNA. Sure we are, at heart, about implementation and getting things done. But it is  precisely because we want to get things done better that we take measurement and learning so seriously (though we take the point on balancing the two). We believe that the type of analytical thinking that is inherent in evaluation is also incredibly useful in implementation. It permeates the points made above: understanding complex environments and systems, defining better citizen agency, and articulating hypotheses of how to promote it.

precisely because we want to get things done better that we take measurement and learning so seriously (though we take the point on balancing the two). We believe that the type of analytical thinking that is inherent in evaluation is also incredibly useful in implementation. It permeates the points made above: understanding complex environments and systems, defining better citizen agency, and articulating hypotheses of how to promote it.

So how to develop a learning posture across the organization? We agree with Duncan that if learning is boiled down to the quest for hard quantitative nuggets, we will have missed not only the big picture, but the core of the complexity we seek to understand. What we are aiming to do, particularly next year, is to set up a learning architecture which will use a variety of metrics, methods, and tools; which will build on the theory behind the implementation choices, allow us to learn quickly as we implement and to vary implementation accordingly, and to look for and capture different kind of outcomes.

In sum, these changes are not about retreating from grand ambitions; they are about assessing where we have gotten so far and shifting tactics. We feel a deep responsibility to be thoughtful about our job, to do it well – the stakes are high for us, but much higher for the people whose realities we want to improve. If we didn’t hold ourselves accountable to high implementation and measurement standards, then we truly run the risk of squandering the chance to do something really powerful. Stay tuned.

Right that’s enough Twaweza posts. Got some more on Tanzania, but might hold that over for a few days. Meanwhile, here’s one final video as I head back to the UK

October 9, 2013

The war for Twaweza’s soul: the hunger for clarity and certainty v the demands of complexity

This is the last in a series of three posts on Twaweza, a fascinating NGO doing some pioneering work on accountability in East Africa, whose big navel  gaze I attended last week. Post one covered Twaweza’s theory of change and initial evaluation results; yesterday I got onto the critique of its thinking and action to date. Today I’m digging deeper into some of the underlying issues.

gaze I attended last week. Post one covered Twaweza’s theory of change and initial evaluation results; yesterday I got onto the critique of its thinking and action to date. Today I’m digging deeper into some of the underlying issues.

Given its rethink, Twaweza is now contemplating a shift in direction – while keeping its focus on citizen agency, focus in on education (rather than try and cover education, health and water); reduce the number of partners; do more things on its own (eg research or education programming); expand successful areas such as policy and advocacy; do more experiments to uncover what works and help the organization ‘fail faster’ and so move on to new stuff.

Plenty of good ideas in there, but it also seems to me to mark an intellectual retreat from the initial commitment to finding new ways to achieve change in complex systems. I think there’s a strong case for digging deeper into complexity, rather than retreating from it. One suggestion that moves in the right direction is to set up a ‘positive deviance lab’, dedicated to detecting and then understanding examples of success in citizens’ action across East Africa.

What would digging deeper mean? First, building a deeper understanding of the system, before jumping in with any particular intervention. That requires a much closer scrutiny of power, relationships and all the forces that maintain the status quo. Twaweza doesn’t seem to have spent much time understanding why change doesn’t happen (e.g. through a ‘3i’ combination of ideas, interests and institutions), which turns out to be pretty key as its work has encountered far more inertia than originally expected.

One of the common findings of the evaluators was that where good things have occurred, it is most often down to the charismatic leadership of particular grassroots heroes, rather than systemic interventions by Twaweza or others. So why not, like the Development Leadership Program, try and understand the origins of such ‘Gandhiness’, and see if Twaweza can design programmes to strengthen it or influence future leaders?

Finally of course, critical junctures, aka windows of opportunity. Like much of the rest of Africa, Tanzania is standing on the threshold of a huge resource boom, in this case offshore gas in the South. In terms of the evolution of the wider social contract between citizen and state, it is probably up there with next year’s referendum on the new constitution. Yet neither were mentioned in the two days of debates, suggesting that even Twaweza is a bit too stuck in the Plan, and not looking around it to respond to new opportunities.

An underlying tension throughout the discussion was between Twaweza’s commitment to running experiments/measuring its impact, and its desire to find new ways to work in complex systems. I’ve never spent so much time with a group of academic evaluators and the experimental mind is fascinating: endless discussions over how to measure really subtle, difficult things like agency – signatures on a petition? Going to a meeting? Saying the right thing to a phone interviewer? Every discussion is weighed down by questions of attribution and bias.

But all this heavyweight cleverness ended up just reinforcing my sense of the limits to quantitative measurement in development. Getting to some numbers that can be properly crunched requires levels of abstraction (eg encoding the responses of hundreds of communities to identify a handful of variables suitable for a regression) and agglomeration that can only do violence to reality.

But all this heavyweight cleverness ended up just reinforcing my sense of the limits to quantitative measurement in development. Getting to some numbers that can be properly crunched requires levels of abstraction (eg encoding the responses of hundreds of communities to identify a handful of variables suitable for a regression) and agglomeration that can only do violence to reality.

Even if you manage to extract some level of numerical relationship, understanding why activity a leads to outcome b requires ‘sending in the anthropologists’ anyway, who will doubtless (being anthropologists) come back and tell you that the abstractions mean that your results are meaningless and/or useless. Any clarity or certainty that emerges from such an exercise may be comforting, but is likely to be illusory.

To be fair, Rakesh thinks I’m caricaturing here and says ‘We have come to care about measurement deeply, not primarily because we need to cater to some donor need or academic joyride, but because we want to be more effective, we want to make a sharper difference, we want to be more accountable for results to the people we claim to serve.’ I completely understand that impatient desire to know whether your work is having impact, but I think that, at least as currently conceived by Twaweza, giving priority to impact measurement could also be a barrier to working effectively in complex systems.

Maybe Twaweza’s measurement problem (and yes I think it has one) stems from using the wrong kinds of metrics – Kate Dyer of the Accountability Tanzania programme was also in the seminar, and described its attempts to make outcome mapping the foundation for much of its learning, even using it to generate some ‘participatory numbers’ – Twaweza could do worse than draw on that work.

There was much discussion about including the evaluators in the design of new projects, but I was pretty alarmed by that too. Sure they do ask brilliant questions, but their need for numbers inevitably ‘contaminates’ (to use one of their favourite words), their grasp of how to work in complex systems. How to avoid the measurement tail wagging the programme dog? There were several dog metaphors – I (doubtless unfairly) likened some of the evaluators to dogs with a bone, letting their enthusiasm for getting stuck in to extracting numbers cloud the original intention of encouraging citizens to take matters into their own hands.

Twaweza’s growing enthusiasm for experiments also raised some concerns, especially when combined with its hunger for numbers. Is handing tens of thousands of teachers a personal ‘cash on delivery’ bonus for getting their pupils to an acceptable grade (as one Twaweza experiment is currently doing) really compatible with building agency, citizens’ voice etc? Sounds more like an incredibly crude bit of behavioural tweaking, with all sorts of potential unintended consequences for the system (think what the much less immediate incentives of school targets have done to schools in the UK and elsewhere – teaching to the test, excluding those likely to fail etc).

Another notable result of the hunger for number-based certainty is ‘Millennium Village thinking’: if we can’t shift the ecosystem at a national level, why not concentrate all our resources on a few communities? Might not even be a bad idea in this case, but interesting to see how the proposal arises from the initial mindset.

So in conclusion, (as they say): the direction that Twaweza takes over the next few years matters well beyond Tanzania’s shores. It is a global leader among NGOs, heroically intelligent, honest, innovative and yes, courageous in acknowledging failure and trying to grapple with many of the issues that bedevil development wonks everywhere – complexity, scale, what and how to measure impact. If it retreats from its grand ambitions in an understandable search for the achievable and measurable (we all want to know we’ve actually achieved some kind of impact, after all), it will have squandered the chance to do something really innovative and we will all be the poorer.

Last word to another one minute Twaweza video (unless Rakesh and his colleagues exercise their right of reply).

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers