Duncan Green's Blog, page 190

April 27, 2014

Into the Unknown: Explorations in Development Practice: lovely (and short) new book from Robert Chambers

Robert Chambers is who I want to be when I grow up, an object lesson in how to grow old (dis)gracefully. Funny, passionate, always willing to admit  doubt and failure, and endlessly curious – he never pulls that weary ‘oh, we tried that in the 1970s and it didn’t work’ routine beloved of other development veterans.

doubt and failure, and endlessly curious – he never pulls that weary ‘oh, we tried that in the 1970s and it didn’t work’ routine beloved of other development veterans.

He also writes short books, something I can’t seem to get the hang of. His latest, ‘Into the Unknown: Explorations in Development Practice’ is just 140 pages. The first half is a series of reflections on his life as a ‘development nomad’, including a behind the scenes account of his ground-breaking work on the World Bank’s ‘Voices of the Poor’ project in the late 90s (still the best view of what it feels like to live in poverty, in my opinion) and a fascinating account of ‘ignorance, error and myth in South Asian irrigation’.

The second half is about one of his abiding passions – participatory learning. And he’s very good at it. One Indian professor told me last year that she still remembered her first class with Robert. The students filed in to find him sitting in a corner. Next to him was a map of the world, with the South Pole at the top. ‘Professor, you have the map upside down’. ‘Really, why do you think that?’ And they were off.

Reading the book prompts all sorts of personal reflection and self-questioning. Some memorable passages:

On (not) lecturing:

‘To lecture, you have to read and remember what others have written, reinforcing it then through public repetition. I did not know enough of any relevant subject to be able to give a formal lecture during my three years at Glasgow, and am amazed to realize that I have only ever given one in 35 years at the University of Sussex.

Instead I have taken the easier option of participatory workshops, trying, but not always succeeding, to do something new each time. Optimal unpreparedness and trying to facilitate more open-ended participatory learning in place of more closed didactic teaching have helped.

But lack of time and energy, laziness, and finding exercises and sequences which seem to work, have lured me into repetition. In consequence I have deceived myself, constructing through speech and public performance false beliefs, progressively discarding caveats and fitting what I say to the needs of the occasion. I do not think many lecturers realize that giving a lecture again and again is, like a catechism, disabling and conservative, because each time we say something we embed it, remember it better and believe it more, diminishing our doubts, finding it easier to repeat, and to a degree closing our minds.’

On ‘islands of salvation’ (aka Potemkin projects):

On ‘islands of salvation’ (aka Potemkin projects):

‘Three stood out: Sukhomajri in Haryana where my Ford Foundation colleagues facilitated a remarkable degree of equity through allocating tradeable water rights to the landless – it received so much attention that for a time the Ford Foundation rented a place to stay in nearby Chandigarh; the Gram Gourav Pratishthan (GGP), an NGO in Maharashtra with a charismatic initiator and patron, Solanki – the GGP allocated water on a per capita basis (enough for half an acre of irrigation per family member); and most markedly and misleadingly of all, Mohini in Gujarat, where a high profile cooperative system was rewarded with and sustained by a specially reliable water supply and other privileged access. Mohini generated a widely publicized, and almost totally false, impression that there were many water cooperatives in Gujarat and that these provided a model replicable elsewhere.

I confess that was seduced by Sukhomajri and the GGP and urged their adoption elsewhere. Both were much visited: when I went to Sukhomajri I was in trouble because I took the best guide, denying him to a large party of important officials whom I then bumped into doing their circuit with a lower status guide; and the Sukhomajri school had a small forest of Eucalyptus planted by distinguished visitors whose memorial plaques were a who’s who of the agricultural establishment of India and of international organizations.

The Sukhomajri and GGP approaches never spread. Both were far too idealistic, sharing water democratically in ways that could not be reproduced. But for a time, in writing after writing, in workshop after workshop, in conference after conference, in keynote address after keynote address, they were cited as feasible ways forward to a fairer and better future. For myself, I was part of all this, and far too naïve in my optimism. Such is the power of repetition, reinforcement and wishful thinking.’

Great stuff.

April 24, 2014

China’s meteoric rise: urban boom; NGOs in from the cold; overtaking the US on pollution and tourism

A while ago, the Economist stepped up its China coverage and opened a separate section, putting placing the country on an editorial par with the USA. It’s taken a while to get going, but recent editions have been excellent. Last week saw a great piece on the rise of China’s NGOs (see chart). This week brings a 14 page special report on the extraordinary speed and scale of China’s urbanization. This from the accompanying leader:

to get going, but recent editions have been excellent. Last week saw a great piece on the rise of China’s NGOs (see chart). This week brings a 14 page special report on the extraordinary speed and scale of China’s urbanization. This from the accompanying leader:

‘In the three decades since economic liberalisation began, China’s urban population has risen by more than 500m, the equivalent of America plus three Britains. China’s cities, already home to more than half the country’s people, are growing by roughly the population of Pennsylvania every year. By 2030 they will contain around a billion people—about 70% of China’s population, and perhaps an eighth of humanity. China’s fate, and that of the Communist Party, will be determined by the stability of its cities.

Much of what has happened is breathtakingly exciting. Shanghai, a drab communist-era sprawl with a few 19th-century relics until the 1990s, has been used as the cosmopolitan backdrop for a James Bond film. Chengdu, whose population has grown by 50% since 2000, boasts the world’s largest building: the New Century Global Centre, which includes a shopping mall and a 300-metre-long indoor artificial beach. Zhengzhou now claims the largest bullet-train station in the world: the $2.4 billion edifice and surrounding area covers the equivalent of 340 football pitches. China’s urbanites whizz from city to city at 300kph (186mph) on a bullet-train network that did not exist six years ago yet now is longer than all of Europe’s. By 2020 it will expand by another two-thirds, or 7,000km (4,300 miles), and every city with a population of 500,000 or more will be connected to it.

Yet the model of pell-mell urbanisation is breaking down. Even the government recognises this. In March the prime minister, Li Keqiang, described the noxious smog that shrouds China’s cities as a “red-light warning against the model of inefficient and blind development”. The World Bank and a Chinese government think-tank have just produced a 544-page report on urban China. It praises China for avoiding ills common in the developing world such as urban poverty, squalor and unemployment. But it says that “strains are starting to show” and that the model is “running out of steam”.

Yet the model of pell-mell urbanisation is breaking down. Even the government recognises this. In March the prime minister, Li Keqiang, described the noxious smog that shrouds China’s cities as a “red-light warning against the model of inefficient and blind development”. The World Bank and a Chinese government think-tank have just produced a 544-page report on urban China. It praises China for avoiding ills common in the developing world such as urban poverty, squalor and unemployment. But it says that “strains are starting to show” and that the model is “running out of steam”.

Two flaws in the Chinese model of urbanisation are causing these strains. The first is economic. Farmers in China have no property rights, so officials are able to grab agricultural land on the peripheries of urban areas and make money for themselves and their cities by selling it to developers. This is not only unjust; it has also led to a relentless pouring of concrete that has given rise to “ghost cities”—half-empty forests of high-rise office and residential buildings that have sprung up around many cities. The vast debts local governments have incurred as a result of this over-hasty development are the focus of foreign worries about the country’s economic stability.

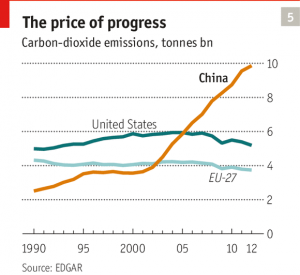

This urban sprawl is also exacerbating China’s environmental problems. People need cars to get around the country’s American-style cities. Beijing now has more cars than Houston, as well as some of the dirtiest air on the planet. And it is not just affecting the Chinese. The nation passed America in 2006  as the biggest emitter of carbon dioxide from energy, and is now pumping out nearly twice America’s level (see graph).

as the biggest emitter of carbon dioxide from energy, and is now pumping out nearly twice America’s level (see graph).

The second flaw in the urbanisation model is a social one. China’s cities are now largely made up of two classes, each with a population roughly the size of America’s: a property-owning middle class which enjoys new social freedoms (see article), takes holidays in Europe and spends like its Western counterparts; and a migrant underclass which toils in factories and menial jobs but is denied public services because its hukou (household registration) is still in the countryside. Both groups have fared well in the boom years; but discontent is growing (see article), and they distrust each other, as well as the party.

On March 16th the government unveiled a long-awaited plan for managing urbanisation. Under the new approach, some 100m migrants will be given urban hukou, and thus full access to urban services by the end of the decade. But that will still leave 200m unregistered, and the issue of who should pay the bill unresolved. Reformers want a new tax on property—the soaring value of which is enriching the middle classes—to provide local governments with a steady revenue stream. The central government fears that this could spur demands by homeowners for more say in how cities are run.’

This week’s edition also contains a fascinating profile of the ‘diaosi’- the millions of young, educated office drones who consider themselves social losers, unable to climb the ladder as China’s social mobility grinds to a halt. Maybe the ‘emerging middle class’ isn’t such a nirvana after all.

This week’s edition also contains a fascinating profile of the ‘diaosi’- the millions of young, educated office drones who consider themselves social losers, unable to climb the ladder as China’s social mobility grinds to a halt. Maybe the ‘emerging middle class’ isn’t such a nirvana after all.

But someone has some spare cash, because the Chinese just overtook the Americans as the biggest single source of international tourism (see chart).

Do any other media cover China this well?

April 23, 2014

How can Governments and Donors support Africa’s Women Farmers?

I got into a bit of hot water recently for a recent post taking down a dodgy stat on women’s land ownership, so it’s nice to be able to post on some really good numbers on gender and agriculture. Levelling the Field: Improving Opportunities for Women Farmers in Africa, is an important and innovative new report (exec sum here, full report here) – sorry I’ve taken a few weeks to get round to it.

The report is innovative partly because it seems fairly unique as a serious research collaboration between an advocacy NGO (the ONE Campaign) and the World Bank, but also because of its findings.

1. Women farmers consistently produce less per hectare than their male counterparts. Like for like comparisons (farms of similar plot size in similar bits of the country) reveal gender gaps of anywhere between 23% (Tanzania) to 66% (Niger). See graph.

2. The gender gap is caused by more than unequal access to inputs: women also face unequal returns to inputs. E.g. even when they have access, extension services seem to benefit women less than men.

3. Focusing on the key drivers of the gender gap in individual countries can both enhance gender equality and foster economic growth.

- Labour poses the main barrier to achieving equality in productivity across all the countries profiled. e.g. women-owned farms tend to have smaller households, and struggle to find enough workers; male workers on female owned farms are less productive than male workers on male-owned farms. This is a big policy vacuum in most countries.

- Differences in the use of, and returns to, fertiliser and other non-labour inputs matter for the gender gap. eg women use less and lower quality fertilizer and get less technical support with application – even after a woman accesses farm land, other associated challenges can limit her productivity.

- agricultural extension and information does not improve female farmers’ productivity to the same degree as that of male farmers. Women farmers tend to get info second hand via their husbands and friends if they are not head of household.

- the gender gap in education, prevalent in previous decades, continues to affect women farmers today: legacy of past gender gaps - improving women’s access to markets and enabling female farmers to shift into high-value commercial agriculture both show promise.

improving women’s access to markets and enabling female farmers to shift into high-value commercial agriculture both show promise.

4. 2014 (as AU year of ag and food security) offers an historic opportunity for African policy-makers, donor governments and development partners to move the agenda forward and commit to concrete policy action to redress the gender gap in African agriculture.

The paper then sets out 10 policy priorities for narrowing the Gender gap and assesses the evidence for each as ‘promising’ or ‘emerging’ (nice trick, NGO and other policy report writers please note). Highlights are:

Strengthen women’s land rights, through registration (whether of communities or individuals), co-titling and individual titling for women, and reforming family and inheritance laws.

Improve women’s access to hired labour (financing and other support)

Enhance women’s use of labour-saving equipment, (credit)

Provide community child-care centres (good to see the care economy getting a look in)

Promoting women farmers’ access to improved seeds and fertiliser, (finance (again) and smaller fertiliser bags suitable for smaller plots).

Tailor extension services to women’s needs (gender training for extension workers; bringing services closer to the household level through farmer field schools and mobile phones; women ag promoters)

Promote women;s cultivation of cash crops and access to markets (working with existing women’s groups)

Raise education levels through adult ed programmes aimed at women farmers

I asked one of our gender gurus, Shukri Gesod for her comments, and here’s some of what she sent over:

Unpacking the dual-roles: The summary touches on the fact that unlike their male counterparts the women have many competing roles of which affects their ability to invest time into the plot-this is a huge factor especially when were speaking about a female headed household-female managed  plot.

plot.

Ownership and access: Glad to see inheritance law reform as a policy change option as that’s a major blockade especially for the “widowed” or “divorced” or even in instances when the children are all female. But what about when the rule of law is not strong and cultural law prevails? In Tanzania, cultural law for example has been codified thus cementing the closing out of women – how do we reform that?

Access to Markets: Women’s sense of (in)security is a major blocker of women engaging in markets – i.e. security in the physical sense as well as security in their production. In terms of access to credit, how is mobile banking changing women’s lives? Until it came along, in most countries women couldn’t open a bank account – they still needed (still do in some parts) a male signatory.

April 22, 2014

Understanding the nature of power: the force field that shapes development

I wrote this post for ODI’s Development Progress blog. It went up last week, closing a series of posts on the theme of Political Voice.

Women’s empowerment is one of the greatest areas of progress in the last century, so what better theme for a post on ‘voice’ than gender rights?

Globally, the gradual empowerment of women is one of the standout features of the past century. The transformation in terms of access to justice and education, to literacy, sexual and reproductive rights and political representation is striking.

That progress has been driven by a combination of factors: the spread of effective states that are able to turn ‘rights thinking’ into actual practice, and broader normative shifts; new technologies that have freed up women’s time and enabled them to control their own fertility; the vast expansion of primary education – particularly for girls – and improved health facilities.

Politics and power have been central to many, if not all, of these advances. At a global political level, the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) appears to be one of those pieces of international law that exerts genuine traction at a national level, as it is ratified and codified in domestic legislation.

But what is needed to turn such global progress into better national policies? To find out in the case of violence against women, Laurel Weldon and Mala Htun have painstakingly constructed the mother of all databases, covering 70 countries over four decades (1975 to 2005). It includes various kinds of state action (legal and administrative reforms, protection and prevention, training for officials), and a number of other relevant factors, such as the presence of women legislators, GDP per capita, the nature of the political regime, etc. In apaper for the Gender and Development journal, they concluded that the empowerment of women was crucial:

‘Countries with the strongest feminist movements tend, other things being equal, to have more comprehensive policies on violence against women than those with weaker or non-existent movements. This plays a more important role than left-wing parties, numbers of women legislators, or even national wealth.’

As Htun and Weldon’s paper implies, violence remains one of the main obstacles to women exercising their rights. Beyond the grim realities of such violence, however, there is some good news at national level, from women-only ‘pink’ public transport, to women’s police stations to the rapidly snowballing campaign against female genital mutilation (FGM).

As Htun and Weldon’s paper implies, violence remains one of the main obstacles to women exercising their rights. Beyond the grim realities of such violence, however, there is some good news at national level, from women-only ‘pink’ public transport, to women’s police stations to the rapidly snowballing campaign against female genital mutilation (FGM).

That focus on women’s movements and women’s voice is a core part of Oxfam’s work around the world. It starts with understanding the very nature of power, the invisible force field that connects individuals, communities and nations, whose visible consequences include much of what we call ‘development outcomes’.

Much of the standard (i.e. ungendered) work on empowerment and voice focuses on institutions and the world of formal power – can people vote, express dissent, organise, find decent jobs, get access to information and justice? These are all crucial questions, but there is an earlier stage, known as power ‘within’. The very first step of empowerment takes place in the hearts and minds of the individuals who ask: ‘do I have rights? Am I a fit person to express a view? Why should anyone listen to me? Am I willing and able to speak up, and what will happen if I do?

‘Power within’ is particularly important for work on women’s rights. In South Asia, the ‘We Can’ campaign is an extraordinary campaign on violence against women launched in late 2004, that at the last count had signed up some four million women and men to be ‘change makers’ – advocating for an end to violence against women in their homes and communities. It aims to reach 50 million people (via 5 million change makers) – a symbolic target equal to the estimated number of South Asia’s ‘missing women’. What’s different about We Can (apart from its scale) is that it is not about policies, laws, constitutions or lobbying the authorities – it aims to change attitudes and beliefs about gender roles at community level. And it’s viral. Each change maker talks to their friends and neighbours, and tries to persuade them to sign up too.

In a piece on women’s voice, I’d better leave the last word to a woman, in this case Selvaranjani Mukkaiah, A We Can Change Maker in Badulla, Sri Lanka:

‘To me change is the killing of fear. For example, someone may know how to sing but will not sing. Someone or something needs to kindle the fire in you and kill the fear that stops you from changing. I have killed the fear of talking and that is a change for me.’

April 21, 2014

Why are Africans getting ripped off on remittances?

Whatever your views of migration, a consensus ought to be possible on one thing: if migrants do send money home, as much as possible of the hard- earned dollars that they send should actually get there, to be spent on putting feeding the kids, putting them through school or even having a bit of fun (that’s allowed too).

earned dollars that they send should actually get there, to be spent on putting feeding the kids, putting them through school or even having a bit of fun (that’s allowed too).

But according to some excellent new research by the ODI, one in eight dollars remitted to Africa is creamed off by intermediaries – a much higher level than for other regions. They launched the report at a meeting in London last week, and the high preponderance of Africans at the launch bore witness to the anger this level of rent-seeking arouses.

Some highlights from the exec sum:

‘Remittances to Africa are rising. In 2013, transfers to the region were valued at $32 billion, or around 2% of GDP. Charges on remittances to Africa are well above global average levels. Migrants sending $200 home can expect to pay 12% in charges, which is almost double the global average (see graph). While the governments of the G8 and the G20 have pledged to reduce charges to 5%, there is no evidence of any decline in the fees incurred by Africa’s diaspora.

Four factors combine to drive up charges. The first is limited competition. Global markets are dominated by an oligopoly of money transfer operators (MTOs) and regional sub-Saharan African markets by a duopoly. Just two companies – Western Union and MoneyGram – account for an estimated two-thirds of remittance pay-out locations in Africa. As in any market, limited competition is a barrier to cost reduction and efficiency gains.

Second, there is evidence of ‘exclusivity agreements’ between money transfer operators, agents and banks. These agreements restrict competition in an already highly concentrated market.

Third, financial market regulation, the high costs of intermediation and limited access to financial institutions in Africa represent additional cost-escalators.

Third, financial market regulation, the high costs of intermediation and limited access to financial institutions in Africa represent additional cost-escalators.

Fourth, financial exclusion and poor regulation in Africa escalate costs. Few Africans have access to formal accounts (which limits their choice of pay-out providers) and most governments require payments to take place through banks, most of which combine high costs with limited reach and low efficiency.’

The panel and Q&A generated some interesting additional thoughts:

The Rwandan High Commissioner, Williams Nkurunziza: ‘I thought capitalism was about fairness and effort, not squeezing money out of Rwanda through some kind of cartel. This is absolutely distressing. We need to advocate for fair trade in goods and services, including money transfers. Western Union controls the vast majority of the outlets in Rwanda, and charges are closer to 18-19%, not 12% as ODI says.’

Mr Nkurunziza pointed to Western regulations as a barrier to entry for new players (the massive cost of jumping through the ever-increasing hoops of due diligence on money laundering and counter-terrorism). ‘Your regulations are taking food from our widows and children. We need to open the market here; tone down the level of oversight that means only the big guys can play.’

Then he got really interesting (and earned a round of applause), pointing out the double standards inherent in the West’s rules on capital and labour. ‘The West exports capital, we export people. Double taxation treaties protect Western transnational corporations in Africa, allowing them to avoid the higher levels of taxation. How can we find a way to ensure our migrants are sheltered from your high taxation – surely the same arguments should apply?’

From the audience, Onyekachi Wambu of AffordUK pointed out that his organization has worked on this, with its Remitaid proposal, arguing for tax rebates on money remitted by migrants in the UK, but progress ground to a halt with the 2008 crash. Maybe time to pick it up again?

UK, but progress ground to a halt with the 2008 crash. Maybe time to pick it up again?

Another African speaker cautioned against presenting the remittance question as ‘baddie white transnationals v victimised Africans’, pointing out that African governments are often some of the worst offenders.

In fairness, ODI picked this up in its report:

‘Remittance corridors within Africa have some of the highest charge structures in the world. Migrant workers from Mozambique sending money home from South Africa, or Ghanaians remitting money from Nigeria, can face charges well in excess of 20%.’

What I liked about this migration discussion, compared to the ideologized, polarized mud-slinging that usually takes place, was its emphasis on making existing migration work better for poor people, and its sensible recommendations:

‘This report calls for a number of measures to lower Africa’s ‘remittance super tax’, including:

Investigation of global MTOs by anti-trust bodies in the EU and the US to identify areas in which market concentration and commercial practices are artificially inflating charges.

Greater transparency in the provision of information on foreign-exchange conversion charges, drawing on the example of Dodd-Frank legislation in the United States.

Regulatory reform in Africa to revoke ‘exclusivity agreements’ between MTOs on the one side, and banks and agents on the other, and promote the use of micro-finance institutions and post offices as remittance pay-out agencies. Governments and MTOs should work to promote mobile banking as a strategy to support the development of more inclusive financial systems.

Engagement by Africa’s diaspora and wider civilsociety groups to put remittances at the centre of the development agenda. The public interests represented by Africa’s diaspora and remittance receivers should be placed above the commercial interests of MTOs and banks.’

And here’s report co-author Kevin Watkins doing a 4m summary

April 16, 2014

Bad Aid: How a World Bank private financing scheme is bleeding a nation’s health system dry

So much for the theory, here’s a bit of grim aid practice (and some top advocacy) to end aid week here on the blog. Lehlohonolo Chefa, Director of the Lesotho Consumer Protection Association  (LCPA) reflects on a week when his organization’s report on a disastrous health experiment in his country made big waves at the World Bank spring meetings

(LCPA) reflects on a week when his organization’s report on a disastrous health experiment in his country made big waves at the World Bank spring meetings

Lesotho is a small mountainous country with enormous health challenges. We have the world‘s third highest burden of HIV and AIDS (23%), life expectancy has fallen from 60 years in 1990 to just 50 years in 2011, and infant and maternal mortality rates are rising. More than half of the Basotho people live below the poverty line.

Last week the organization I work for – the Consumers Protection Association – published a joint report with Oxfam that shows how a health public–private partnership (PPP) is draining the budget of the Ministry of Health and diverting scarce resources away from primary healthcare services in rural areas, where death rates are rising and where three-quarters of the population live. I spent the week in Washington DC for the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and IMF where our paper sparked considerable interest.

The Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital, which opened in October 2011, was built to replace Lesotho’s old main public hospital, the Queen Elizabeth II (QE II) Hospital, in the capital, Maseru. It is the first of its kind in Africa – and in any low-income country – because all the facilities were designed, built, financed, and operated under a PPP that includes delivery of all clinical services.

From the outset it was claimed that the PPP would provide vastly improved, high-quality healthcare services for the same annual cost as the old public hospital. This PPP has been promoted as a flagship model for other countries to follow. But in reality Lesotho’s experience provides powerful lessons in what not to do.

The PPP was developed under the advice of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private sector investment arm of the World Bank Group. An 18-year contract was awarded to Tsepong Ltd – a consortium led by the South African private health care company Netcare. Tsepong is contracted to treat all patients presenting at the Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital, up to a maximum of 20,000 inpatients and 310,000 outpatients annually. The government pays an annual fee to Tsepong to treat these patients and any additional patients are charged on top.

The PPP was developed under the advice of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private sector investment arm of the World Bank Group. An 18-year contract was awarded to Tsepong Ltd – a consortium led by the South African private health care company Netcare. Tsepong is contracted to treat all patients presenting at the Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital, up to a maximum of 20,000 inpatients and 310,000 outpatients annually. The government pays an annual fee to Tsepong to treat these patients and any additional patients are charged on top.

The costs for the Government of Lesotho have escalated rapidly. In 2013/14 the PPP cost the government $67m – consuming 51% of the total government health budget. This is up from 41% the year before. The hospital is being run at nearly two and a half times the amount that was agreed as affordable between the Government of Lesotho and the IFC before the contract was awarded. The contract seems to have worked for the benefit of the private company (who are set to see a return of 25% on equity) rather than for the Government or people of Lesotho.

As a representative of users of health services in my country, I find many of the features of the PPP alarming. Of course there is no doubt that Lesotho, like any country, needs a national referral hospital that can provide highly specialised services. However, given that most Basotho live in rural areas, the priority should be to develop a comprehensive network of primary and secondary health care services. Improving access to quality health care, especially in remote mountainous areas where people sometimes have to travel for hours on horseback to reach their nearest clinic, is the surest way to accelerate progress towards improving the health of the nation. I am very concerned that the ability to do so is being undermined by one hospital, which takes up the lion’s share of the health budget.

Last week I took these messages to the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and IMF in Washington. There I had the opportunity to meet with other civil

Cuckoo in the nest

society organisations, World Bank Group staff, and a number of World Bank Executive Directors.

Our message was well received and I was especially encouraged to hear the President of the World Bank Dr Jim Yong Kim say that he would be taking a personal interest in the case. I was even more pleased to see the Lesotho Prime Minister and Minister of Health publicly expressing their concerns about the project in reaction to the report. The South Africa’s Minister of Health even went on record saying that he expressed concerns at the time the hospital was opened and warned it would not work. Disappointingly the IFC have yet to provide a comprehensive response to our critique of the PPP.

I very much hope that the World Bank Group will stop promoting this project as a success and something to be replicated across Africa. As a first step they should remove all misleading marketing materials on the Lesotho PPP from their website. My advice to other countries is don’t copy us. Rather study our example carefully and demand concrete evidence of the effectiveness and efficiency of PPPs before even considering this option. Given our experience in Lesotho I would not recommend relying on the advice of the IFC, who in this case have not worked in the best interests of our nation.

On behalf of the many civil society organizations I work with, I call on the World Bank Group to finance a fully independent and transparent expert financial audit and broader review of the Lesotho health PPP, in partnership with the Government of Lesotho. This should include a presentation of the full range of options available to the Government to mitigate the negative impact this partnership is having on Lesotho’s wider health system.

There is a need for patients’ voices to be represented in crafting a way forward. There has been virtually no participation of citizens in monitoring the agreement. Privatization of healthcare and other essential services should be discouraged. Advocates of PPPs should take a look at this case and realize that their interventions could undermine the role of state. Instead, the World Bank should work with local experts in order to have people who can protect the national interest. The World Bank should commit to not experiment with new and complex initiatives that put poor countries on the brink of collapse, as this project has done in my country.

Post from Oxfam health wonk Anna Marriott here. More coverage in the Guardian. Netcare response. Oxfam defends its numbers.

April 15, 2014

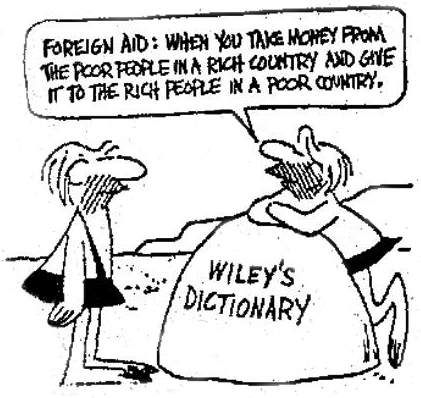

Angus Deaton makes the case against aid (and you get to vote)

I am grateful to Duncan Green for giving me an opportunity to respond to his comments on The Great Escape. I summarize the key evidence, and try to  give a coherent story of how I think aid works, and when it will fail. Like Duncan, I fully recognize (and am motivated by) the moral imperative to help people who are suffering, and I strongly endorse the idea of using aid to promote the international public goods that he describes.

give a coherent story of how I think aid works, and when it will fail. Like Duncan, I fully recognize (and am motivated by) the moral imperative to help people who are suffering, and I strongly endorse the idea of using aid to promote the international public goods that he describes.

My argument does not rely on evidence about projects; I have no doubt that many of these are good, but project evaluation cannot address the aggregate effects of aid on development. Cross-country regressions can estimate the aggregate effects in principle, though there are many problems, not least that neither writers nor commentators are good at explaining where the results come from, and authors sometimes retreat behind a fog of econometric technique. Yet we cannot ignore these studies; informal, undisciplined stories are not helpful.

Here is my take-away: (a) controlling for the factors that usually appear in growth regressions, aid as a share of recipient GDP is negatively correlated with growth, (b) similarly controlled, the change in growth is positively related with the previous period’s change in the aid to GDP ratio, where periods are several years long, and (c) the share of aid in GDP is larger for small recipients than large recipients, but the latter grow more rapidly than the former.

Point (a) is typically dismissed because well-directed aid will respond to bad growth shocks, which biases down the estimate of aid effectiveness. It is not clear that aid actually behaves like this, but I accept the point for now. On (b), lagging the aid variable and then taking changes flips the sign of the bias (the error term is this period’s shock minus last period’s shock and is this positively correlated with last period’s aid minus aid from two periods ago), so that if (a) is not evidence against aid, then (b) cannot be evidence for aid. I interpret point (c) as evidence against aid, not because country size might not favor growth directly, but because there is no other obviously powerful mechanism, while my account of aid has exactly that implication.

Why might aid fail in aggregate? One of my favorite stories in Duncan’s book is about owners of fishponds being violently dispossessed by more powerful people, and then getting them back through political action. Money and know-how were not the issues; power was the problem, and politics the solution. But this good outcome is unusual. The worst case I know happened in Goma in 1994, when the perpetrators of the genocide in Rwanda fled into the eastern DRC with their wives and families. Perhaps two-thirds of the aid for the humanitarian emergency was diverted for training the murderers to go back to finish off the Tutsi “cockroaches.” Alex de Waal, in Famine Crimes, explains over and over how aid can only reach the victims of war by paying off the warlords, and sometimes extending the war. Such aid saves lives, but at the price of other lives later.

The mechanisms of poverty and power are the same in peacetime, albeit with less catastrophic outcomes. With a government in control, it is impossible to reach those who are powerless without paying the powerful, and paying the President and the government will make them less interested in listening to their people. Instead of having to raise money through taxation and deliver services in return, they can instead use their people to extract money from donors. They can enrich themselves by keeping their population poor; such aid is an instrument of inequality. Some governments may be more benevolent, but large, prolonged amounts of aid ultimately corrupt benevolent rulers, or cause them to be replaced by exploitative rulers. Domestic NGOs or CSOs that monitor the state lose their legitimacy when they accept funds from abroad.

The mechanisms of poverty and power are the same in peacetime, albeit with less catastrophic outcomes. With a government in control, it is impossible to reach those who are powerless without paying the powerful, and paying the President and the government will make them less interested in listening to their people. Instead of having to raise money through taxation and deliver services in return, they can instead use their people to extract money from donors. They can enrich themselves by keeping their population poor; such aid is an instrument of inequality. Some governments may be more benevolent, but large, prolonged amounts of aid ultimately corrupt benevolent rulers, or cause them to be replaced by exploitative rulers. Domestic NGOs or CSOs that monitor the state lose their legitimacy when they accept funds from abroad.

Duncan agrees that such undermining is a possibility, but doubts the evidence. Yet we need only look at the (very large) historical (and recent) literature on the resource curse; rulers who need not raise revenue from their people will often behave badly, sometimes spectacularly so.

There is also an extensive literature on how this happens by observers of aid, from historians, aid workers, journalists, and political scientists. Useful and insightful accounts include those by Michela Wrong (on Zaire, Eritrea, and Kenya), Michael Maren (Somalia), Nina Munk (Millennium Villages), Matthew Connelly (“aid” for population “control”) with broader discussions from Jonathan Glennie, Fiona Terry, Linda Polman, Martin Meredith, Charles Ferguson, and James Scott, as well as the well-known accounts by Bill Easterly and Peter Bauer. Many of these combine close observation with deep political, economic, and historical knowledge.

Histories of long-run development by Eric Jones, David Landes, Ian Morris, or by Daron Acemoglu and Jim Robinson (whose last chapter takes the same view of aid as my own) provide ample evidence on how development was crippled by rulers who had no reason to tax or consult their subjects. Jakob Svensson and Tim Besley and Torsten Persson have developed more formal accounts. Svensson is particularly insightful in noting that donors are responsive to well-meaning but necessarily ill-informed domestic constituents, including domestic interest groups from the aid industry, a process that is only too well-understood by the recipient governments. (Such politics makes “country ownership” impossible, and dooms agreements such as the Paris Declaration.) We are left with what Francisco Toro has aptly called co-dependency, in which the harm is largely borne by the citizens of the recipient  countries who have no voice in this political equilibrium.

countries who have no voice in this political equilibrium.

Duncan says that aid has rather moved on since Mobutu and the Cold War. I wish. The US gives aid to those who support the “war on terror,” or who recognize the state of Israel, and European and American politicians can use aid to burnish sullied images, even when it harms the recipients. Is it really so much better to support regimes that imprison, torture and kill their enemies provided only that child mortality rates are falling? Perhaps. Yet it is well to recall Amartya Sen’s argument that the components of freedom are also instrumental in producing it: we make trade-offs between different freedoms at our practical and ethical peril.

Not sure if this is a good idea, but let’s have a poll (you can choose more than one option). I’m particularly anxious about this one, because Angus is a global survey guru, advising Gallup among others, and I haven’t had time to consult with him over the questions. But interactivity trumps prudence, so over to you to vote. And I suspect that there will be more contributions on this topic over the coming weeks.

And if you have 90 minutes to spare, I recommend Bill Easterly v Owen Barder, covering some of the same ground in last week’s CGD debate.

April 14, 2014

Why Angus Deaton is (mostly) wrong to attack aid for undermining politics and accountability

Continuing aid week here on FP2P, here’s my response to Angus Deaton’s recent broadside against aid, and his claim that I agree with him. Tomorrow, Angus responds. Nervous, moi?

I’m both flattered and alarmed that Angus Deaton has been citing From Poverty to Power (the book, not this blog) in defence of his attack on aid in his

and aid can help

book The Great Escape (previously reviewed here). Flattered because Deaton is a development superstar. Alarmed because he comes down strongly against spending money on aid, and his critique is being picked up by aid critics, a position which I most definitely do not share. So I’ve gone back and reread Deaton’s book, and some of the other research on the impact of aid. Let’s try and make sense of it.

In his recent LSE lecture (from minute 47 onwards here) and in an excellent cross-examination by Owen Barder on Development Drums, Deaton’s most substantive criticism was on the link between aid and domestic politics:

‘Economic development cannot take place without some sort of contract between those who govern and those who are governed…. It is the need to raise taxes, and the difficulty of doing so without the participation of those who are taxed, that places constraints on the government and to some extent protects the interests of taxpayers…. One of the strongest arguments against large aid flows is that they undermine these constraints, removing the need to raise money with consent.’

In other words, bunging aid money to governments means they no longer have to listen to their citizens and opens the door to all kinds of bad practices.

What do other researchers say? When I did a quick trawl of the literature, I had a familiar sensation – how is it that with all those clever people researching away, we never seem to be able to answer really important questions (unless you count ‘needs more research’ as an answer?). The aid discussion follows the classic pattern of

1) a blizzard of cross country regressions reaching contradictory findings, eg one IMF study finds ‘aid improves revenue performance significantly’, while another asserts with equal certainty ‘tax revenue declines by 9 cents for each grant dollar.’

2) Baffled researchers then revert to ‘priors’ and political theory, to argue that aid does indeed undermine institutions. Eg see this 2006 CGD paper.

Is that the best they can do? What about some serious country case studies (preferably post Cold War – aid has rather moved on since Mobutu) investigating whether aid has indeed undermined the social contract, as claimed? There are plenty of examples of donors using conditionality to try and over-rule sovereign governments, but none of this more subtle erosion of the social contract alleged by Deaton.

As it happens, my own priors mean that I suspect that some level of erosion does indeed take place (Deaton’s right about me on that), so I was surprised by the lack of evidence. What did I miss? Any links welcome.

As it happens, my own priors mean that I suspect that some level of erosion does indeed take place (Deaton’s right about me on that), so I was surprised by the lack of evidence. What did I miss? Any links welcome.

Deaton accepts that ‘These harms of aid need to be balanced against the good that aid does, whether educating children or saving lives’ and is notably more positive on his area of genuine global expertise – health. But he argues that ‘Those who advocate more aid need to explain how it can be given in a way that deals with the political constraints’. I’m not convinced. In the balance of argument, we have lots of concrete, tangible benefits in the shape of nurses, teachers, vaccinations, avoided deaths etc, lined up against a rather vague and not very well evidenced claim of long-term institutional damage. Before taking an axe to the aid budget, I would say the burden of proof should be on the aid critics, and they haven’t done very well so far.

The best recent summary of the state of the evidence I could find was from veteran aid wonk Roger Riddell, who last month published an updated paper on the impact of aid. Riddell responds directly to Deaton’s attack:

‘In my view, this assessment goes too far. The conclusion drawn is based on what probably is a too partial and selective reading of the evidence. Stating that countries will always be better off without aid remains what it has always been – an unproven assertion. Donors may well have failed, at times undermined recipient-country ownership and (unintentionally) held back long-term development prospects, but they are now more aware of their shortcomings, as well as more knowledgeable about how they need to change current practices to give greater priority to transformational aid to make aid work better overall.’

Riddell believes that ‘beyond this rather sterile exchange, a far more important debate has begun to take place about the systemic effects of providing aid. Until recently, it was predominantly aid’s harshest critics who suggested that any short-term benefits that aid might achieve would be eclipsed by the indirect harm it could bring in its wake. Today, the main aid donors are ready to acknowledge that… a series of systemic problems have developed that are now seriously undermining aid’s potential impact. The gap between aid’s strongest critics and an important cluster of studies analysing aid’s wider impact has narrowed considerably.’

That recognition informs the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (sorry for the descent into aid-speak - see Nicola McIvor’s post yesterday for more), with its commitment to  ‘country ownership’ and ‘inclusive development partnerships’.

‘country ownership’ and ‘inclusive development partnerships’.

So what might the emerging common ground look like? Deaton is not against all aid, and suggests health, humanitarian emergencies, and countries where aid remains a low percentage of overall government revenues. He also advocates aid for basic research, technical assistance to governments that want it, and support for poor countries in the innumerable international negotiations. He advocates a good ‘put your own house in order’ list of sanctions on odious regimes, transparency in corporate payments to governments (e.g. on minerals extraction) and tackling northern restrictions on trade and migration, and perverse biofuel subsidies. He misses tax havens and illicit flows, but I imagine he would support their inclusion.

To that I would add the whole ‘thinking and working politically’ approach, including taking seriously bad aid’s potential for institutional damage. That means acknowledging and tackling any negative impacts/ strengthening the positives (eg by supporting better tax collection and other institutional strengthening, where it is demand-led; channelling a percentage of government-to-government aid to citizen or parliamentary watchdogs to keep them honest; maybe cash on delivery type contracts).

So yes, lots needs to be done to ensure aid strengthens poor people’s ‘freedoms to do and to be’. But no (sorry Angus) we shouldn’t be taking a hatchet to aid budgets.

Got a feeling Angus isn’t going to agree with this. Come back tomorrow to find out.

April 13, 2014

Will this week’s aid and development gabfest in Mexico be just another boring conference or a milestone in ensuring development works for the poor?

It’s aid week here on the blog. To kick off, Oxfam policy adviser Nicola McIvor sets the scene for a big international conference in Mexico. Tomorrow and  Wednesday, Angus Deaton and I have an argument about whether aid helps or harms development. Who knows, you may even get to vote.

Wednesday, Angus Deaton and I have an argument about whether aid helps or harms development. Who knows, you may even get to vote.

The development world is at a critical juncture as Mexico City this week hosts the first High-level Meeting (HLM) of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC). OK, the title isn’t sexy, but government representatives and parliamentarians from both traditional donors and emerging providers of development cooperation like Indonesia, China and Mexico, as well as NGOs, trade unions; and multinational corporations will all be there. If you follow development debates, you will want to know what happens.

Mexico provides an opportunity to assess whether donors and recipient countries are living up to the commitments they made in Busan and are on track to meet their targets in 2015. But will it be one of those pointless development conferences where government officials pat each other on the back in an orgy of self-congratulation, or a genuine effort to tackle difficult issues in ensuring development cooperation is useful to people living in poverty? So far, I’m afraid it’s looking more like the former. Here’s what’s at stake:

People could lose their voice and opportunity to drive their own development: Inclusive development – the acknowledgement that development is driven by people through open dialogues between country governments and their citizens, was a key outcome of Busan. But it is being resisted by most governments in current discussions. For inclusive development to take place civil society organisations must have the space to operate and enable a people-driven approach, ensuring accountability from the bottom up. Yet since Busan we have seen a rise in the number of governments closing this space. The indicator on an enabling environment for civil society was discredited, because of ‘technical issues’, in the monitoring report on progress since Busan. Will governments commit to reverse this shrinking space, and agree on a way to measure progress ? Or will we end up with a top down, ‘expert’-led approach that ignores the voices of the people?

Donors could get away with sidestepping their own responsibilities whilst continuing to ‘assess’ those of recipient countries: After recipient countries out performed donors in the Paris Monitoring survey, some donors sought to scale back the ambitions of new global indicators to hold all partners (whether they give aid or receive it) accountable in development cooperation. The first progress report on the Busan monitoring framework, which provides the details of country-by-country performance of recipient countries but less detailed assessments of donor performance, suggests that donors are unwilling to be judged and ranked. Participants at the HLM should be asking what direction the monitoring report is going in. Do we want to see country-by-country reporting to ensure that citizens can hold donors and their governments to account?

Donors could get away with sidestepping their own responsibilities whilst continuing to ‘assess’ those of recipient countries: After recipient countries out performed donors in the Paris Monitoring survey, some donors sought to scale back the ambitions of new global indicators to hold all partners (whether they give aid or receive it) accountable in development cooperation. The first progress report on the Busan monitoring framework, which provides the details of country-by-country performance of recipient countries but less detailed assessments of donor performance, suggests that donors are unwilling to be judged and ranked. Participants at the HLM should be asking what direction the monitoring report is going in. Do we want to see country-by-country reporting to ensure that citizens can hold donors and their governments to account?

Does the private sector deserve a seat at the table? Some refer to the private sector as the new donor darling and there is certainly a growing recognition of the important role the private sector can play in tackling poverty and stimulating economic growth. Busan even recognised the private sector as equal partners in development policy. However, to maximise the impact of development cooperation, the private sector must implement the Busan commitments to deliver real results for the poor through inclusive development and ensuring appropriate accountability. Mexico will see a push for increased public-private partnerships (PPPs) and will launch a new ‘roadmap’ for partnerships with the private sector – could this influence how aid is delivered and development cooperation conducted in the post-2015 world?

The Global Partnership could either provide or miss its opportunity to offer a concrete way forward for the ‘how’ of post 2015: Whilst the Global Partnership has been dubbed by some as the ‘how’ of the post-2015 agenda, it is proving difficult to discuss the GPEDC at the UN and integrate it formally into post-2015 documents.

Global Partnership has been dubbed by some as the ‘how’ of the post-2015 agenda, it is proving difficult to discuss the GPEDC at the UN and integrate it formally into post-2015 documents.

Will delegates make clear and substantive links to post-2015 in order to influence and implement the post-2015 goals? If Busan was about bringing stakeholders to the table, then Mexico is about getting results. This means action to make progress on people-driven development. The big question is what will be Mexico’s legacy? Will the Mexico meeting build on what was achieved in Busan with the necessary ambition and capacity to monitor development cooperation efforts in an attempt to hold all actors to account and improve development cooperation for the people they serve? So far, as delegates gather, I sense a lack of optimism around the table.

Follow the discussions on twitter: #GPHLM, @njmcivor

April 10, 2014

Can development really be delivered by investing in private banks?

Peter Chowla of the Bretton Woods Project introduces its new report, which asks why the World Bank is still stuck in pre-crisis thinking about finance and what  civil society should do about it.

civil society should do about it.

‘Banksters’ have become famous since the financial crisis just five years ago. Media portrayals of New York’s ‘Wall Street’ or the ‘City’ in London have frequently vilified bankers. Though Occupy Wall Street was broken up by the police, in popular consciousness distrust of the financial sector remains.

Yet somehow the development sector seems strangely immune to this. If anything, in the last half decade, development policy wonks and officials have tried to sidle up to the financial sector more than they have tried to distance themselves from the profit-obsessed and short-termist culture of finance.

At this week’s World Bank spring meetings, Bank president Dr Jim Yong Kim is presiding over a massive change in strategy for what remains one of the most influential development institutions in the world. Kim, an NGO-founding medical doctor, is a friendly face for the Bank after a succession of investment bankers and war hawks at the helm. He even once protested in front of the Bank. Yet nearly two years into the job, one of the Bank’s most important shifts under Kim has been towards bankers and not away from them. The financial sector is now the largest beneficiary of World Bank Group (WBG) investment.

Let’s put this into context. Investments by the Bank’s private sector arm (the IFC) in trade finance and other financial intermediaries were 62% of the total in the last fiscal year, amounting to $36.1 billion for the last four years. Over the same period the World Bank’s public sector arms (IBRD and IDA) committed $22.1 billion to health and $12.4 billion to education. That’s right – investments in the financial sector were about three times those in education and about 50% greater than those in health. On top of this, the IFC’s portfolio of financial sector investments shows funding was concentrated in commercial banking and upper-middle income countries, Russia being the largest single country destination, with little evidence of the claimed development impact.

There are serious questions about what kind of development you might get from investing in the financial sector. There are no examples of countries that have successfully delivered prosperity and equity by bolstering the power of the financial sector without first having a coherent national development strategy and industrial policy. Success stories, such as Korea, Taiwan and China, relied on a heavily regulated domestic financial sector that supported industry. The IFC doesn’t seem to have this in mind, but instead prioritises “financial deepening” and “financial inclusion”, as fuzzy as any concepts in the development lexicon. Oxfam’s research on inequality has clearly highlighted the risk to the public interest from powerful elites that capture institutional processes. Is turbo charging the financial sector, infamous for regulatory capture even in supposedly mature democracies, the best strategy for eliminating global poverty?

It’s not just the IFC. An increasing number of public institutions are channelling money into the financial sector. The new Green Climate Fund plans to do this. The G20 is involved too. But there are large risks to the environment, communities, and overall development efforts. Global Witness’ exposé of land grabs by Vietnamese rubber plantations in Cambodia (financed by the IFC through a private equity fund) is just one example. Other cases in India, Honduras, Guatemala, and Uganda demonstrate the negative impacts.

Having a more powerful, but short-term-profit-oriented, financial sector seems likely to heighten risks while skewing incentives away from the sort of longer-term investments needed to sustainably diversify economies and reduce poverty.

21st Century development?

While our elite international institutions seem clear where they are going, civil society organisations have not yet fully grasped the changing nature of cross-border finance, nor come up with a coherent response to financialisation. Our report lays out three possible approaches civil society could take: asking for stronger rules and transparency; investing in ‘better’ private financial institutions; or throwing it all out the window and demanding public (not private) sector finance. These approaches are not easy to reconcile and will turn on fundamental questions about the role of private finance in a fair, sustainable and prosperous economy.

Big NGOs tend to ask for stronger rules. These are amenable to campaign plans, log frames, and emails to supporters that can identify successes and claim victory. On the other hand, many believe business can be used to fight poverty but that we should seek out different kinds of businesses, such as cooperatives, social enterprises and other socially oriented institutions to deliver finance. Neither of those approaches is easily scalable, but both have their appeal.

There are still others who conclude that the hurdles to the private financial sector serving as development agents are just too great. They call for a new generation of public financial institutions, which, along with international public financial support from the likes of the IFC, could seek to mobilise domestic private wealth to invest in accordance with public interest policies.

None of the approaches is suitable for every national context, but if civil society doesn’t get cracking on a coherent strategy, we might be stuck with powerful financial interests driving the agenda at the heart of every development initiative. Surely we learned the consequences of that five years ago?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers