Duncan Green's Blog, page 184

July 23, 2014

How can politics change to serve future generations (on climate change, but lots of other stuff too)?

No-one objected to yesterday’s rehash of a recent BS (blue sky, OK?) session, so here’s another. An hour in a cool café in Brixton market with Kiwi academic Jonathan  Boston, wrestling with the really big question on climate change and the survival of our species: how could political institutions emerge that govern for future generations?

Boston, wrestling with the really big question on climate change and the survival of our species: how could political institutions emerge that govern for future generations?

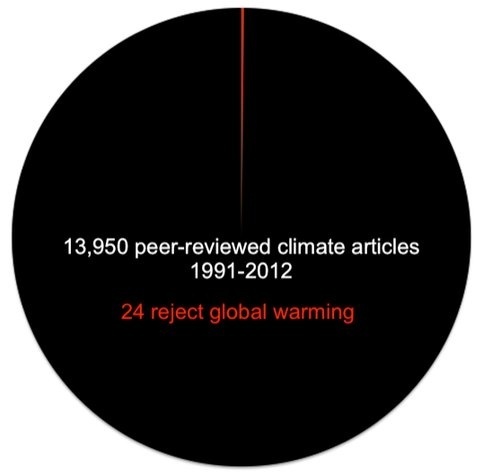

Jonathan, who runs the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies at the Victoria University of Wellington, is researching this fascinating question, and starts off from a pretty gloomy place. In 2011 he wrote an excellent paper for the Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal (gated, so I’m not linking to it) which identified a ‘Serious mismatch between the magnitude and urgency of the climate change problem and the current political will to overcome or mitigate the problem’

He identifies four ‘asymmetries’ preventing action:

The voting asymmetry: The young and future generations have no vote.

The cost-benefit asymmetry: The costs and the benefits of policies to mitigate climate change are significantly different with respect to the crucial dimensions of time, certainty, visibility, and tangibility.

The interest group asymmetry: Many of the costs of mitigation policies tend to be concentrated and fall mainly on easily identifiable and powerful vested interests, whereas the potential beneficiaries are highly dispersed.

The accounting asymmetry: Firms are not required to include the effects of their activities on the environment in their financial statements and governments ignore net changes in natural capital (and other environmental impacts) in their national accounts.

Jonathan sketches out four possible solutions to these obstacles along with (unfortunately) the weaknesses of each:

Supra-national solutions (eg UNFCCC). Designed to shift decisions away from nation states to regional or global entities that are subject to different incentive structures, and are shielded to a greater extent than democratically elected governments from the pressures of voters and powerful interest groups dominated by short-term horizons. But these will only work if national governments are prepared to cede sovereignty and comply with the rulings, and the ailing UN climate change negotiations show how unlikely that is on climate change.

Because more evidence is definitely what we need…..

Institutional solutions: Designed to shift decisions within the nation state from governments and parliaments to independent bodies, such as expert committees, that are not directly accountable to voters. Role models include various Monetary Policy Committees, or the UK’s Committee on Climate Change. But just as with supra-national bodies, governments are reluctant to give such institutions real power beyond and advisory role.

Constraining solutions. These constrain the decisions of national governments by giving greater weight to future generations. E.g. the constitutions of Bolivia, Japan and Norway have such provisions, but the fact that Norway’s Supreme Court has never cited the relevant article in the 22 years since it was introduced suggest this is more of a nudge than a slam dunk.

Rebalancing solutions. These give decision makers a greater incentive to protect the environment and the interests of future generations by, for instance, changing the preferences of voters, the distribution of power between relevant interest groups and/or national parliaments, or the quality and availability of information about environmental performance. Lowering voter age is a smart, if fairly timid, first step – more voters interested in a slightly longer term future. Shifting to various kinds of green accounting could also help tilt the balance over the longer term.

Conclusion?

‘Most democratic governments will be constrained by the four asymmetries such that only gradual, ad hoc measures to reduce emissions will be electorally feasible. This may be grim news for future generations, but it appears to be the only realistic conclusion.’

That was published in 2011. Jonathan’s new research project is looking for a few more reasons to be cheerful. Here’s some of the things we discussed over our Brixton beer:

We need to think more about the crucial importance of norms – when in history has one generation sacrificed for the benefit of future generations? Three examples:

Medieval Cathedrals: splashing the cash on a building which will only be used by your grandchildren

Fighting Wars: risking your lives now to keep your country free for future generations

Sovereign Wealth Funds: can anyone explain the politics of why Norwegians seem happy to keep paying high taxes so that future generations can build up an almost $1trn pension fund? Why didn’t some populist party spring up and sweep the elections by saying ‘sod the grandkids, you never have to pay taxes ever again’?

These examples are most definitely not driven by immediate cost-benefit calculations but by norms and values – what is right, what is socially (un)acceptable etc. They are driven by life-defining norms like religion or national identity that trump short term material interests. That’s why climate change campaigners should be spending much more time on plugging into deep normative frameworks by, for example, engaging the major religions on issues of stewardship.

National myths and stories: Policies are often invisibly constrained/stoked by social memory – of inflation (Germany), revolution (Bolivia), rationing and togetherness in wartime (UK), myths of equal opportunity (US), encirclement and threat (Russia). Understanding and plugging into these narratives may help shift behaviours.

Shocks: I’m an even bigger broken record on this than on the importance of working with faith groups. Anyone wishing to shift to longer term considerations has to get  better at understanding and grasping the transformative potential of ‘windows of opportunity’. Fast forward to the next major floods in the UK: what if climate groups, religious leaders, scientists, opinion shapers and others had already set up their network, so that on the day the floods hit, they can press the button for a rapid response of events, publications and campaign razzmatazz to begin within days? Totally doable, precious little sign of it last winter.

better at understanding and grasping the transformative potential of ‘windows of opportunity’. Fast forward to the next major floods in the UK: what if climate groups, religious leaders, scientists, opinion shapers and others had already set up their network, so that on the day the floods hit, they can press the button for a rapid response of events, publications and campaign razzmatazz to begin within days? Totally doable, precious little sign of it last winter.

Leadership: it would help if we understood where the future Mandelas and Gandhis will come from, so the forces of light can get to them early. The Developmental Leadership Programme is doing some interesting work here, but plenty of room for more.

In the meantime, the debate seems to be gravitating towards ‘co-benefits’- eg green investments that also boost jobs and growth, or getting a technological edge by investing in green tech before your competitors. A more sophisticated version recalls ‘The Leopard’ – ‘everything must change so that everything can stay the same’ – if those with power see a sufficiently serious existential threat, they may prefer preemptive change instead. Fine, but it’s a hell of an assumption to say that these are enough to avert catastrophic climate change. What if they aren’t?

Finally, at least let me indulge in some gallows humour. According to Jonathan, the New Zealand government set up three commissions: a short term one (council of economic advisers), a medium term one (planning council) and a long term one (commission for the future). Only the short term one survived. Maybe there’s just no (political) future in long term thinking……

Any other political reasons to be hopeful/straws to clutch?

Update: or maybe the answer is just to give up on democracy? Here’s a new piece on Chinese leadership on mitigation. I discussed this with Tim Jackson a while back.

July 22, 2014

Big Data and Development: Upsides, downsides and a lot of questions

One of the more scary but enjoyable things I do is be interviewed on stuff I know absolutely nothing about (yeah, yeah, I know – no change there then). You get to grasshopper around multiple issues and

disciplines, cobbling together ideas and arguments from scattered fragments, making connections and learning new stuff. Great fun. This week, I’ll blog about a couple of these BS (blue sky, of course) sessions to give you a flavour.

First up, half an hour discussing ‘big data’ with a friend/researcher who shall be nameless (don’t want to destroy their reputation). Here’s some of the points that arose:

First, massive confusion on definition: depending on who you talk to, ‘Big Data’ means scraping massive amounts of existing data from sources like Facebook and Twitter (the UN’s Global Pulse has done great work on this); generating large volumes of new data; computer modelling of the existing data or using it for particular purposes like transparency and accountability, or targeting humanitarian relief.

Big Data is great when it throws up new questions and correlations, and stimulates thinking and discussion (The Economist had a fascinating piece this week on how Big Data is a natural partner of iterative, experimental approaches to change). But I’m dubious about it providing a short cut to political change, empowerment etc. There are lots of inspiring examples of using data to promote social change, but plenty of caveats and warnings against magic bulletism too, as the recent contributions to this blog from 3 transparency and accountability gurus showed.

How will Big Data evolve? It may follow the path of governance work – starting off with lots of supply (people building crowdsource websites that no-one uses), when that doesn’t work, move on to demand (citizens’ movements demanding data from baffled/incompetent/hostile governments) and then end up looking for combos of the two – hybrid institutions for data that combine old and new systems in new, context-specific ways; getting lots of unusual suspects in a room to find tailored solutions, including data-based ones, to agreed problems.

And what about the downsides? What are the risks of Big Data?

Data tribalism: mass media gives way to tribal media, as everyone splits off into their own online echo chamber, and increasingly has no idea what the rest of the world is thinking.

Data tribalism: mass media gives way to tribal media, as everyone splits off into their own online echo chamber, and increasingly has no idea what the rest of the world is thinking.

Big Brother Data: around the world,

governments are trying to close down space for civil society. CSOs routinely use a lot of IT, which provides a perfect channel for snooping and repression.

Don’t assume libertarianism will persist. Ok the internet still reflects its libertarian origins, but what if it is taken over by bad guys, whether governments or corporate?

What’s the link to inequality? Does the top 1% of the digitally connected have access to x times more data than the poorest 10% and is that digital divide growing or shrinking, between and within countries? What are the knock-on effects in terms of power and wealth?

Which all leads to a broader question. Is there something inherently individualist about the acquisition and use of data, as currently conceived? There are signs that it undermines collectivism, for example by allowing what were once pooled risks (eg National Health Service) to become customised, and eventually fragmented (her risk is bigger than mine, so why should I cross subsidise her with my taxes). If so, is a collectivist alternative approach– i.e. collective acquisition and access, data even conceivable?

Possible implications for today’s developing countries:

Big Data could of course allow them to leapfrog the painfully slow business of building solid national statistical capacity. A bit like mobiles v landlines.

Does building their data capacity in a world ruled by outside multinationals require a data equivalent of industrial policy? Perhaps countries should protect and nurture their infant data-related industries, only opening data ‘borders’ when national capacity and competitiveness has been created: a data equivalent of the East Asian tigers. But that would seem to go against any push for data comparability.

It feels like the governance of data is going to become ever-more important as a global issue. Who owns it? When can it be bought and sold? Do we need a UN Convention on

Self explanatory, really

Access and Use of Information to try and lock in some positive norms around its usage?

I think I can guarantee that most, if not all, of this is complete nonsense, but I’d be interested to hear if anything resonates with data people

Next up: how could political institutions emerge that govern for future generations?

Big Data and development: Upsides, downsides and a lot of questions

One of the weirder things I do is get interviewed on stuff I know absolutely nothing about (yeah, yeah, I know – no change there then). You get to grasshopper around multiple issues and

disciplines, cobbling together ideas and arguments from scattered fragments, making connections and learning new stuff. Great fun. This week, I’ll blog about a couple of these BS (blue sky, of course) sessions to give you a flavour.

First up, half an hour discussing ‘big data’ with a friend/researcher who shall be nameless (don’t want to destroy their reputation). Here’s some of the points that arose:

First, massive confusion on definition: depending on who you talk to, ‘Big Data’ means scraping massive amounts of existing data from sources like Facebook and Twitter (the UN’s Global Pulse has done great work on this); generating large volumes of new data; computer modelling of the existing data or using it for particular purposes like transparency and accountability, or targeting humanitarian relief.

Big Data is great when it throws up new questions and correlations, and stimulates thinking and discussion (The Economist had a fascinating piece this week on how Big Data is a natural partner of iterative, experimental approaches to change). But I’m dubious about it providing a short cut to political change, empowerment etc. There are lots of inspiring examples of using data to promote social change, but plenty of caveats and warnings against magic bulletism too, as the recent contributions to this blog from 3 transparency and accountability gurus showed.

How will Big Data evolve? It may follow the path of governance work – starting off with lots of supply (people building crowdsource websites that no-one uses), when that doesn’t work, move on to demand (citizens’ movements demanding data from baffled/incompetent/hostile governments) and then end up looking for combos of the two – hybrid institutions for data that combine old and new systems in new, context-specific ways; getting lots of unusual suspects in a room to find tailored solutions, including data-based ones, to agreed problems.

And what about the downsides? What are the risks of Big Data?

Data tribalism: mass media gives way to tribal media, as everyone splits off into their own online echo chamber, and increasingly has no idea what the rest of the world is thinking.

Data tribalism: mass media gives way to tribal media, as everyone splits off into their own online echo chamber, and increasingly has no idea what the rest of the world is thinking.

Big Brother Data: around the world,

governments are trying to close down space for civil society. CSOs routinely use a lot of IT, which provides a perfect channel for snooping and repression.

Don’t assume libertarianism will persist. Ok the internet still reflects its libertarian origins, but what if it is taken over by bad guys, whether governments or corporate?

What’s the link to inequality? Does the top 1% of the digitally connected have access to x times more data than the poorest 10% and is that digital divide growing or shrinking, between and within countries? What are the knock-on effects in terms of power and wealth?

Which all leads to a broader question. Is there something inherently individualist about the acquisition and use of data, as currently conceived? There are signs that it undermines collectivism, for example by allowing what were once pooled risks (eg National Health Service) to become customised, and eventually fragmented (her risk is bigger than mine, so why should I cross subsidise her with my taxes). If so, is a collectivist alternative approach– i.e. collective acquisition and access, data even conceivable?

Possible implications for today’s developing countries:

Big Data could of course allow them to leapfrog the painfully slow business of building solid national statistical capacity. A bit like mobiles v landlines.

Does building their data capacity in a world ruled by outside multinationals require a data equivalent of industrial policy? Perhaps countries should protect and nurture their infant data-related industries, only opening data ‘borders’ when national capacity and competitiveness has been created: a data equivalent of the East Asian tigers. But that would seem to go against any push for data comparability.

It feels like the governance of data is going to become ever-more important as a global issue. Who owns it? When can it be bought and sold? Do we need a UN Convention on

Self explanatory, really

Access and Use of Information to try and lock in some positive norms around its usage?

I think I can guarantee that most, if not all, of this is complete nonsense (but feel free to say so). But it sure was fun. Shame I’ve used up my month’s ration of question marks.

Next up: how could political institutions emerge that govern for future generations?

July 21, 2014

What can Islam teach secular NGOs about conflict resolution? (and human development, climate change, gender rights…..)

Lucy Moore, a policy adviser at Islamic Relief Worldwide came to talk to Oxfam staff last week. We used the ‘in conversation’ format, along the lines of my recent chat with Jamie Love, which seems to work better than the standard powerpoint + Q&A.

Jamie Love, which seems to work better than the standard powerpoint + Q&A.

Islamic Relief has some really interesting publications on Islamic approaches to human development, gender and development, and in Lucy’s case, ‘conflict transformation’ (which I think means making it better, rather than worse…). She came to Oxfam to present Working in Conflict: A Faith Based Toolkit for Islamic Relief, and its shorter ‘Introduction for external agencies’ (7 pages + 3 page glossary of Islamic terms – v handy).

Lucy’s work points up some of the benefits of working within a faith perspective (most of these apply to other religions just as much as Islam):

Legitimacy: research by the World Bank and others consistently underlines the importance of their faith in poor people’s lives, and that they trust their religious institutions far more than they trust governments, NGOs or anyone else. But if your approach is secular, legalistic, evidence-based and rationalist (all good things, right?), don’t expect it to resonate – it will sound alien to the lives of an awful lot of the people you are trying to help. Take this quote from IR’s work in Yemen:

‘While the trainer was making reference to the UN and international human rights, a participant responded by saying that Islam addressed human rights 1400 years ago… Another participant stood up and said they (the trainees) would not believe or trust any book or material not related to Islamic concepts.’

Collective v Individual: Faith-based approaches often emphasize the importance of the collectivity – community, family etc, over the individual. There are problems with this approach (I’ll come to those), but with regards to some areas like resolving conflicts or climate change (stewardship – the duty this generation owes to future generations), I suspect collective approaches are more likely to work. Discuss.

The importance of ritual: ‘Rituals play an important part in conflict resolution’ – secular agencies often underestimate the importance of ritual in the people’s lives. Not so, faith groups.

Restorative rather than retributive justice: Lucy’s paper states that Islamic theology is very clear that ‘reconciliation and restorative justice is preferable’ to retribution and that wrongdoing creates obligations to ‘make things right’. Shame not everyone is listening – this seems a world away from some of the punishments meted out in the name of Islam.

Restorative rather than retributive justice: Lucy’s paper states that Islamic theology is very clear that ‘reconciliation and restorative justice is preferable’ to retribution and that wrongdoing creates obligations to ‘make things right’. Shame not everyone is listening – this seems a world away from some of the punishments meted out in the name of Islam.

On obligation to take action on injustice (and not just speak or think about it): According to a well-known Hadith (saying or tradition of the Prophet): “Whosoever of you sees an injustice, let him change it with his hand; and if he is not able to do so, then with his tongue; and if he is not able to do so, then with his heart – and that is the weakest of faith.” And I don’t think ‘with his hand’ includes clicktivism……

Lucy’s advice to secular NGOs wishing to work with faith groups was a) don’t start pretending you’re a theologian; engage with faith leaders instead and b) treat them as ‘architects’ not just ‘gatekeepers’ (when I asked staff in DRC if we worked with faith groups they said ‘sure, we get the priests to distribute our leaflets’. Oops)

So much for the positives, but there were (unsurprisingly) some pretty big concerns.

Firstly, IR seems to understand social capital better than power. The emphasis on community and family is fine when power is equally distributed, but what if the community victimizes some of its members, or husbands abuse wives, or parents beat up their children? The introduction for external agencies was particularly feeble on gender: ‘while social norms do typically exclude [women and youth] from decision-making processes, it is important to be aware that they are likely to be marginalised from the decision making process, while simultaneously utilising alternative avenues of influence and communication.’ Sorry, but I don’t buy this, if it’s saying that backchannels (conversations over the dinner table?) are a substitute for explicit power over decisions.

Secondly, while IR emphasizes the importance of ‘faith literacy’ and paints a remarkably positive picture of Islam, the dissonance with what I see on the news is vast. Even allowing for the bias of Western media, I see few signs of a search for harmony and restorative justice in the Muslim world right now, which seems to be home to a disproportionate number of the world’s conflicts.

allowing for the bias of Western media, I see few signs of a search for harmony and restorative justice in the Muslim world right now, which seems to be home to a disproportionate number of the world’s conflicts.

But (to end on a positive), another striking aspect of Islam is its willingness to evolve according to changing contexts, and to incorporate local customary law (provided it doesn’t contradict fundamental principles). That at least bodes well for IR’s effort to blend the legitimacy and social roots provided by faith, with the search for empowerment and human development. And respect to Lucy for a) braving a bunch of rights-based headbangers, and b) giving a lunchtime talk in the middle of Ramadan (though I did ask people not to bring sandwiches…..)

I also have a feeling she might want the last word on this topic – over to her (and everyone else)

July 20, 2014

Links I liked

Highlights from last week’s tweets (and more displacement activity for Monday morning). Follow @fp2p if you want the rest, including lots more serious development type stuff

Last Monday was Bastille day. Time for a makeover….. [h/t Stephen Brown]

It was a good week for America’s comedians, (well Johns Stewart and Oliver anyway, best to forget Bill Maher). They both excel in brilliant satire/commentary on the toughest of topics. John Stewart took the soft option out and covered Gaza…….. English exile John Oliver took on income inequality and Uganda’s treatment of gays and lesbians (including US complicity in stoking up the hatred).

While we’re on gay rights in Africa (or lack of them), ODI’s Kevin Watkins had an excellent piece in Huffpo on the role of outsiders, aid donors etc (Engagement better than conditionality, he reckons).

Lots of UK political news last week:

Wondering why Britain’s Tory Party is sticking to its promises and keeping aid at 0.7% of national income, while slashing everything else? I think there’s a clue in Project Umubano, the party’s volunteer project in Rwanda & Burundi, now sending out a team for the 8th year in succession. Reminds me of Nicaraguan Sandalistas back in the day…..

DFID is to face a full judicial review over its alleged funding of rights abuses and relocation in Ethiopia (DFID denies it).

In the week when the former schools minister lost his job, pupils at Barrowford Primary School leavers got a lovely letter about their exam results. The authors admit it’s not original. Who cares?

In the week when the former schools minister lost his job, pupils at Barrowford Primary School leavers got a lovely letter about their exam results. The authors admit it’s not original. Who cares?

Shameless self plug for the new Global Policy ebook on the Future of Aid, put together by Andy Sumner at Kings College – pieces from lots of interesting thinkers. And me.

Those funky tech types at DFID have put together the world’s first Instagram documentary (on FGM and early marriage). Suitable topics for John Oliver’s in tray?)

July 17, 2014

What’s the best way to measure empowerment?

Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) used to send me into a coma, but I have to admit, I’m starting to get sucked in. After all, who doesn’t want to know more  about the impact of what we do all day?

about the impact of what we do all day?

So I picked up the latest issue of Oxfam’s Gender and Development Journal (GAD), on MEL in gender rights work, with a shameful degree of interest.

Two pieces stood out. The first, a reflection on Oxfam’s attempts to measure women’s empowerment, had some headline findings that ‘women participants in the project were more likely to have the opportunity and feel able to influence affairs in their community. In contrast, none of the reviews found clear evidence of women’s increased involvement in key aspects of household decision-making.’ So changing what goes on within the household is the toughest nut to crack? Sounds about right.

But (with apologies to Oxfam colleagues), I was even more interested in an article by Jane Carter and 9 (yes, nine) co-authors, looking at 3 Swiss-funded women’s empowerment projects (Nepal, Bangladesh and Kosovo). They explored the tensions between the kinds of MEL preferred by donors (broadly, generating lots of numbers) and alternative ways to measure what has been going on.

The start by breaking down the fuzzword ‘empowerment’, into the ‘four powers’ (power within; power with; power to and power over) model best known from my Oxfam colleague Jo Rowlands’ 1997 book ‘Questioning Empowerment’ (although she claims not to have invented it) and used by everyone ever since.

When you disaggregate power in this way, you come up with an interesting finding:

‘[quantitative] M&E can capture some evidence of increased ‘power-to’ in numbers of people trained in a skill or knowledge, or able to market their products in a new way, or mobile phones distributed to enable women traders to share knowledge. However, ‘power-within’ is a realm of empowerment which does not directly lend itself to being captured by quantitative M&E methods.’

What’s more, while obviously women worry a good deal about income and putting food on the table, soft data (eg on feelings and perceptions) best collected by qualitative methods such as in depth interviews:

What’s more, while obviously women worry a good deal about income and putting food on the table, soft data (eg on feelings and perceptions) best collected by qualitative methods such as in depth interviews:

‘Appear to be what the women value most in [these] projects. While this is probably a very obvious point for feminists working with women, it is noteworthy for practitioners who tend to focus on supporting ‘power-to’ through provision of material resources and other tangible changes.’

That certainly chimes with what I found when talking to women in Community Protection Committees in the DRC last month – the biggest personal impact of their participation was the palpable sense of pride and self esteem that came from learning about their rights and how to exercise them, and then passing that knowledge on to their neighbours. Hard (though not impossible) to put a number on that. Listen to this interviewee from Bangladesh:

‘Before taking part in the project, I was not allowed to visit places outside my house. This all changed after I joined the producers’ group. My income and communication skills increased and improved. Due to the income and awareness, my husband allows me to attend different meetings of the producers’ group, village and district levels. Due to my involvement in the producers’ group, other producers encouraged me to run for a local government election as member in Union Parisad [UP – lowest tier of local government in Bangladesh]. I was motivated to try and finally was successful in winning the election. From a simple housewife, I am now an elected member of the UP.’

That last quote highlights another plus of qualitative methods – they really help communicate project impact (as do numbers, of course – maybe for different audiences). But Carter & co. want to move on from a crude ‘quant v qual’ dichotomy. They argue that quant and qual methods complement each other – and mixed methods can actually be the best way to tackle both the “did change happen” questions, as well as the why. For example, ‘Research methods associated with collecting qualitative data often actually reveal unexpected quantitative data, including changes in children’s school attendance, better nutrition, and so on.’

And how you do qualitative research matters. Yes, lots of qualitative research is pretty slapdash, but beware the temptation to ‘professionalize’ it and send for Rigorous  Qual Consultants Inc: ‘If qualitative information is collected by an external agency with a clear, pre-determined mandate, there is the risk that much potentially interesting information is ignored as irrelevant to the task in hand, and not transmitted to the project staff.’ So NGOs may be better advised to build staff skills in qualitative research, rather than outsourcing.

Qual Consultants Inc: ‘If qualitative information is collected by an external agency with a clear, pre-determined mandate, there is the risk that much potentially interesting information is ignored as irrelevant to the task in hand, and not transmitted to the project staff.’ So NGOs may be better advised to build staff skills in qualitative research, rather than outsourcing.

In the end, they argue, ‘the best way to measure empowerment is to ask those directly concerned’. But it’s not quite as simple as that. Sure, it would be perverse in the extreme if we tried to measure empowerment by ignoring the nuance of voice and lived experience of those involved in order to generate another dry statistic. But equally, you just can’t rock up in a village and ask do you feel empowered?’ and expect to get a useful result.

There are clearly difficulties with putting all this into practice, namely that ‘‘value for money’ seems to require quantifiable facts’. But the authors think that’s no excuse. ‘Nevertheless we wonder if better communication on the part of development professionals about the worth of qualitative evidence in demonstrating value could mitigate this demand.’

Excellent piece, and if you’re not already signed up to either the journal or its twitter feed (@GaDjournal), why not?

And here’s a blog introducing the GAD issue from one of the contributing authors, Kimberly Bowman

July 16, 2014

A seismic shift in improving the behaviour of large companies? Guest post from Phil Bloomer

My former boss, Phil Bloomer is now running the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (check out its smart new multilingual website). Here he sees some signs of hope that the debate on corporate responsibility is  moving beyond trench warfare over voluntary v regulatory approaches. Fingers crossed.

moving beyond trench warfare over voluntary v regulatory approaches. Fingers crossed.

‘Mind the gap’ is a refrain that any visitor to London’s Underground trains will have had drilled into their brains. In development and human rights, one of the most controversial issues is how to deal with the dangerous governance gap that has opened up between the powerful globalising forces in our economies, often led by large companies, and the often weak capacity of societies to cope with the problems and damage these forces can create.

A fortnight ago came a seismic shift in this debate. The UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution to create an international binding treaty for transnational corporations. This comes three years after the adoption, by consensus, of the more voluntary, UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Most observers put this major tremor down to rising frustration at the apparent glacial pace of implementation of the Guiding Principles by governments (only the UK, Netherlands and Denmark have so far agreed National Action Plans), and few companies are stepping up. The age-old, and sometimes theological, divisions between opposing panaceas of state-regulation v voluntary codes, may be returning.

But there is also a positive difference in the debate at this juncture: there are many voices that believe that a smart mix of regulatory and voluntary approaches are essential to the progress we need in business’ contribution to human rights, development, and sustainability. Perhaps the Guiding Principles and the binding treaty approaches might be complementary?

John Ruggie, author of the UN Guiding Principles, in a response this week, is deeply concerned that a blanket international treaty is impractical and a distraction. But he views “international law as a tool for collective problem solving” and calls for “precision tools” in international law focused on specific governance gaps. He also highlights the inconsistency of opponents of advances in international law: “if national law and domestic courts suffice, then why do TNCs not rely on them to resolve investment disputes with states? Why is binding international arbitration necessary, enabled by 3,000 bilateral investment treaties?”

John Ruggie, author of the UN Guiding Principles, in a response this week, is deeply concerned that a blanket international treaty is impractical and a distraction. But he views “international law as a tool for collective problem solving” and calls for “precision tools” in international law focused on specific governance gaps. He also highlights the inconsistency of opponents of advances in international law: “if national law and domestic courts suffice, then why do TNCs not rely on them to resolve investment disputes with states? Why is binding international arbitration necessary, enabled by 3,000 bilateral investment treaties?”

Equally, one European government official admitted recently, under Chatham House rules, that it is using the threat of a binding treaty to demand more decisive action on the Guiding Principles by fellow governments.

Peter Frankental of Amnesty International has said ‘we should not be afraid to frighten the horses” regarding a treaty, and that we need a “far-reaching debate on the kind of binding mechanisms that are necessary to ensure companies operate to acceptable standards and the different pathways towards achieving this”.

But there are also voices of polarisation: one of them, described in a recent report by Misereor and Brot fur die Welt, is the business associations that lobby the United Nations intensely. The report highlights the “influence that corporate actors exert and their ability – in cooperation with some powerful UN member states – to prevent international binding rules for TNCs at the UN and, instead, promote legally non-binding, ‘voluntary’ approaches such as CSR and multi-stakeholder initiatives.” Equally Richard Howitt MEP, the CSR rapporteur for the European Parliament, recently expressed his frustration at business associations’ lobby power in Europe to delay and, at times, derail even innocuous regulation for ‘non-financial reporting’ by companies regarding their environmental and social impact. Though, happily, this advance in basic transparency, was finally passed in April this year, after 15 years of debate.

It is perhaps this blanket opposition to a blend of regulatory and voluntary approaches to human rights in business that is most damaging to advances in business  contributing to human rights and development. A number of business leaders, led by the likes of Paul Polman of Unilever, accept that there is a dangerous governance gap. In contradiction to some business associations, they are beginning to speak out in favour of appropriate regulation, as they want a more level playing field in social and environmental standards which will cut out the cowboys, and provide a benefit to responsible companies, and to the societies they operate in.

contributing to human rights and development. A number of business leaders, led by the likes of Paul Polman of Unilever, accept that there is a dangerous governance gap. In contradiction to some business associations, they are beginning to speak out in favour of appropriate regulation, as they want a more level playing field in social and environmental standards which will cut out the cowboys, and provide a benefit to responsible companies, and to the societies they operate in.

It is this governance gap that the proponents of both the UN Guiding Principles, and the binding treaty seek to address. While a robust debate is necessary, cooperation and complementarity between them is likely to do far more for the victims of abuse in supply chains than sterile dispute and competition.

Phil Bloomer, Executive Director, Business and Human Rights Resource Centre. Twitter: @pbloomer

July 15, 2014

How Change Happens: Supporting tribal people to claim their rights to India’s forests

Next up in the series of case studies in promoting ‘active citizenship’ is Oxfam India’s work in an impossible-to-spell new state. All comments welcome, full case study here [P&C  case study. v2 12 June 14]

case study. v2 12 June 14]

India’s new and heavily forested state of Chhattisgarh is home to some of its most marginalized communities, whose traditional ways of living from forest products are under threat from encroachment by mining and other ‘development’. Oxfam India has supported a local NGO to help forest communities take advantage of the implementation gap between this reality and the provisions of progressive legislation. Early results are encouraging, with dozens of villages winning new forest and grazing rights under the Act.

Forests are critical to tribal people’s lives and livelihoods. They provide jobs and income through the collection of Non Timber Forest Products (NTFPs), such as Tendu leaves (Diospyros melanoxylon), used for making Indian cigarettes (beedi). People consume NTFPs or sell them to government-promoted co-operatives and societies, as well as private traders.

But the use of forest land by tribals is a perennial source of conflict, with their legal rights often ignored by government officials, producing a situation of insecurity and eviction, as mining and industry has encroached on the forest.

However, this process of economic marginalization has prompted a political reaction. The “Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act of 2006 marks one recent effort by the Indian government to correct historical discrimination. The result of decades of struggle by tribals and their allies, the FRA assures their rights over forests and other traditionally accessed natural resources around tribal habitations.

Although there are several tiers of administration involved in implementing the Act, the key level is the Gram Sabha, or village assembly. The Gram Sabha is in charge of receiving and verifying claims under the Act, and appoints the statutory 10-15 person Forest Rights Committee (FRC) containing at least 1/3 women, and 2/3 from Scheduled Tribes.

Legislation is one thing; implementation (especially in India) is entirely another. When the local partner started work, communities and officials alike were largely oblivious to the FRA, and unsurprisingly, there were few efforts to implement it.

Theory of Change

The position of different players on community forest rights stems from a complex interplay of incentives and motives within the different levels of the state and beyond. Those supporting community forest rights for tribals include (unsurprisingly) the tribals themselves, and their civil society allies, but also District and village level officials and those specifically tasked with defending tribal communities, such as the Principal Secretary, Tribal Development.

The position of different players on community forest rights stems from a complex interplay of incentives and motives within the different levels of the state and beyond. Those supporting community forest rights for tribals include (unsurprisingly) the tribals themselves, and their civil society allies, but also District and village level officials and those specifically tasked with defending tribal communities, such as the Principal Secretary, Tribal Development.

Other parts of the state machinery are, however, more hostile. The powerful Forest Department sees the FRA as undermining its control and tries to avoid cooperating with those, even state officials, charged with implementing the Act.

According to the local partner, although some local media and individual journalists are sympathetic, most other potential stakeholders are largely uninterested in (or hostile to) the community forest struggle. Faith organizations, especially mission services, are broadly indifferent unless disputes affect their own service delivery in areas such as health and education. The police and judiciary only react when a law and order issue arises, which has so far been avoided.

The private sector is largely present in the area in the form of private traders, seen by tribals and CSOs as highly exploitative and often linked to the ruling political party. Large mining companies, such as Adani Mining, have preferred to keep a low profile, although this may of course hide ‘closed door’ lobbying activities.

The widening gulf between a harsh economic reality and potentially progressive legislation created both an implementation gap and an opportunity. Led by an Adivasi grassroots activist, Oxfam’s local partner, Chaupal Grameen Vikas Prashikshan Evum Shodh Sansthan (Chaupal) is a combination of four people’s organizations, founded in 2005. All four organizations are predominantly tribal people’s organizations, with a a large proportion of their membership from tribal communities. They came together through their work on another popular initiative – the Right to Food campaign.

Chaupal’s work at state level has been a fairly typical NGO combination of coalition-building, brokering links with local and national officials, and information dissemination.

In January 2013, as a first step, Chaupal worked with village communities to make a traditional map of their village and forest area on the ground, which was later  mapped on paper. Everything was marked out, including canals, schools, trees, rivers etc. Livelihoods dependent on natural resources and all NTFPs along with average quantities harvested were recorded, along with the usage of medicinal herbs, tubers and the types of flora and fauna found in the region. This map was sanctioned and signed by all village members, FRC members, Gram Panchayat members and even people from neighbouring villages.

mapped on paper. Everything was marked out, including canals, schools, trees, rivers etc. Livelihoods dependent on natural resources and all NTFPs along with average quantities harvested were recorded, along with the usage of medicinal herbs, tubers and the types of flora and fauna found in the region. This map was sanctioned and signed by all village members, FRC members, Gram Panchayat members and even people from neighbouring villages.

Parallel to the process of filing claims at the village level, Chaupal had a critical role in advocating with the district level government officials like the Collector (the senior government official) and the Divisional Forest Officer (DFO), making them aware of the content of the Act and convincing them of the importance of implementing it.

With support from other donors in addition to Oxfam, Chaupal filed a total of 40 CFR claims. The results so far have been encouraging. On 7th Sept 2013, 34 villages got their NTFP and grazing rights as part of the CFR claims. These were distributed in person by the Chief Minister, Mr. Raman Singh. But although this success was historic, it is by no means complete. In particular, the state seems more willing to recognize individual rights than community rights, which are needed to protect the land from proposed diversion for mining and other non-forest purposes.

But even partial victory was a novel experience for many of India’s tribal communities, and the process by which it was achieved was as important as the immediate gains.

Wider Lessons

Although the Community Forestry Rights Project’s combination of extreme social exclusion, grassroots mobilisation and judicial activism is quintessentially Indian, it provides wider insights about the ability of NGOs and other outsiders to catalyse change.

It is essential to have a partner that can bridge the divide, with roots in the tribal communities, and connections in the relevant decision-making bodies.

Implementation gaps offer particularly productive areas for advocacy and organization – since the state has already agreed to the principle (in this case of community forest rights), the battle to persuade it to take action is already half won.

It is vital to understand the incentives and motivations of officials at different levels of the state. That enables change-makers to identify and build alliances with champions, and weaken opposition.

Nothing inspires and empowers more than success: Chaupal has broken the myth that the state government is unwilling to provide CFR title due to pressure of forest, mining and industry lobby.

Communities with little literacy and connection to the outside world have shown themselves able to engage and successfully mobilise in procedure-intensive claim processes. They can organise at village level and negotiate with the state.

To read or comment on previously blogged case studies in this series, go to Campaigning on the US Deepwater Horizon oilspill, Changing hearts and minds on Violence Against Women in South Asia, promoting Women’s Leadership in Pakistan and Nepal, Labour Rights in Indonesia, and Community Protection Committees in DRC

July 14, 2014

Good? Bad? Ugly? Two years in, how’s Jim Kim doing as World Bank boss?

Nicolas Mombrial, head of the Oxfam’s Washington office, does his cup half full/empty thing on Jim Kim’s first two years in office

This month, Jim Kim celebrated his second anniversary at the head of the World Bank Group (WBG). After his first year, I concluded “pretty good so far but the jury is  still out”. Has anything changed since then? Well, Jim Kim has said a lot of good things this year but the effects still remain to be seen, mainly because the agenda has been over-dominated by the Bank’s big internal reorganization. The main difference is that Jim Kim has been confronted with a big scandal around the IFC’s investments in Honduras. More on that later…

still out”. Has anything changed since then? Well, Jim Kim has said a lot of good things this year but the effects still remain to be seen, mainly because the agenda has been over-dominated by the Bank’s big internal reorganization. The main difference is that Jim Kim has been confronted with a big scandal around the IFC’s investments in Honduras. More on that later…

Last year I concluded “success or failure will hinge on whether Jim Kim can mobilize the institution and its shareholders behind the vision”. The shareholders are definitely now on board. As for the institution, it is not yet so clear (although he will have the full support of the newly appointed Directors). I also can’t honestly say what the impact of the reorganization will be (fingers crossed). I am just happy that we can now get back to talking about policy and impact on poverty. 2 years has been a long time.

So let’s talk about policy. As last year, Jim Kim has said some remarkable things and has continued to lay down a more progressive agenda.

It may be the first time that we see a President of the WBG acting as an activist, challenging people to unite around a movement to end poverty, raising the need to address gender issues, speaking against anti-gay laws and against discrimination of all kinds. But not all the picture is that rosy: under Jim Kim the number of women in management position has fallen by about 25% and as our colleagues from Human Rights Watch have said, progress on human rights still need to be institutionalized.

On inequality, while we criticized the Bank’s lack of ambition, we recognized that its new goal on “shared prosperity” – Bank-speak for inequality- was already a success. This year, Jim Kim has continued to raise the imperative to fight inequality making it crystal clear to any doubters that it is the end of a WBG that thinks that it is enough to focus on growth alone. However, the Bank still risks missing the real picture in terms of extreme income inequality and a big part of the problem (political capture) as long as it refuses to look at the top 10% as well as the bottom 40%.

It also needs to say what it is actually going to do to reduce inequality. Answers will apparently come at the Annual Meetings in October. I am curious to see if they are now going to evaluate all their projects with an equity angle (including what the IFC does), to talk about things they have been silent on lately like tax, or if they will just repackage some old policy wine in some shiny new bottles.

Jim Kim continues to be a powerful advocate for the role of health in ending extreme poverty and reducing inequality. He added this year a strong new argument: the positive impact health can have on growth. Kim went a step further on user fees, accepting that the Bank was excessively ideological on this issue in the past. The Bank has also been pushing Universal Health Coverage on the global stage, developing a framework with the WHO to measure it. But we have not yet seen how this is going to change the WBG’s work. Does it mean that the WBG is going to review all projects –including the IFC’s – to make sure they focus on equity and we do not end up with another Lesotho health PPP; that it will support governments to develop publicly provided health care and to abolish user fees; and that it is going to stop supporting private health insurances that do not benefit the poorest? If so, we will truly have cause to celebrate.

Jim Kim continues to be a powerful advocate for the role of health in ending extreme poverty and reducing inequality. He added this year a strong new argument: the positive impact health can have on growth. Kim went a step further on user fees, accepting that the Bank was excessively ideological on this issue in the past. The Bank has also been pushing Universal Health Coverage on the global stage, developing a framework with the WHO to measure it. But we have not yet seen how this is going to change the WBG’s work. Does it mean that the WBG is going to review all projects –including the IFC’s – to make sure they focus on equity and we do not end up with another Lesotho health PPP; that it will support governments to develop publicly provided health care and to abolish user fees; and that it is going to stop supporting private health insurances that do not benefit the poorest? If so, we will truly have cause to celebrate.

The WBG is more than ever putting its weight behind the efforts to combat climate change, making the economic and social arguments that it has far reaching development benefits for everyone. But once again, it remains to be seen how Kim can transform his speeches into action. Is he going to ensure that WBG programs are more climate sensitive by supporting a specific safeguard on climate change? Or push for funding for renewable energy to dramatically increase as it could not only be better for climate change but, maybe even more importantly, better for providing poor people with access to energy? The WBG in 2013 invested 38% of its energy lending in fossil fuels and 24 % in renewables. These numbers need to change.

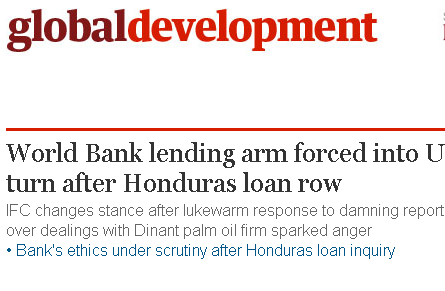

In the middle of these promising noises, a big stain spoiled Jim Kim’s second year in office: the scandal around the IFC investment in Corporacion Dinant in Honduras, which will go down in history as one of the very few cases where the WBG Board stood unanimously against management. While Jim Kim inexplicably signed on the initial appalling IFC answer that basically refused to recognize mistake, under pressure from CSOs and his Board, he promised that the findings of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) would be listened to and pushed the IFC for a better response.

But that is not enough. Though an extreme example, Dinant is not an isolated case. Other IFC investments such as Tata Mundra, Agrokasa, Dragon Capital; the CAO  report conclusions on Dinant, or the WBG’s own staff survey demonstrate that Dinant is the consequence of deeper cultural/systemic problems at the IFC (including risk categorization, project selection, inadequate weight given to social and environmental standards, and staff incentives). To this, Jim Kim has not given a proper answer. There has been an IFC ‘lessons learned’ paper but it is insufficient. Jim Kim needs to do more than find solutions to cases as they arise; he needs to give a strong political signal–as Zoellick did after the Wilmar case – by urging the IFC to come up with concrete, time bound proposals to address its cultural and systemic problems. That is the only way he can ensure the IFC gets behind his grand vision.

report conclusions on Dinant, or the WBG’s own staff survey demonstrate that Dinant is the consequence of deeper cultural/systemic problems at the IFC (including risk categorization, project selection, inadequate weight given to social and environmental standards, and staff incentives). To this, Jim Kim has not given a proper answer. There has been an IFC ‘lessons learned’ paper but it is insufficient. Jim Kim needs to do more than find solutions to cases as they arise; he needs to give a strong political signal–as Zoellick did after the Wilmar case – by urging the IFC to come up with concrete, time bound proposals to address its cultural and systemic problems. That is the only way he can ensure the IFC gets behind his grand vision.

So all in all, a good second year, but the jury is still out (and two years is a long time to reach a verdict – the judge may soon declare a mistrial). Let’s hope that by the time of JYK’s third anniversary, the World Bank Group will be firmly on the right side of history.

July 13, 2014

Links I liked

Highlights from last week’s tweets (and more displacement activity for Monday morning). Follow @fp2p if you want the rest, including lots more serious development type stuff

Twitter loves snark – the ‘4th law of thermodynamics’ got by far the most (in fact, an order of magnitude more) retweets last week. [h/t Conrad Hackett]

Is humour a better mobilizer than pity? The rise of aid satire (I blame the Norwegians) [h/t WhyDev]

Why is accusing someone of doing something ‘like a girl’ an insult? Inspiring, viral (33m hits) video. Does it matter that it’s linked to product promotion?

Getting action on Climate Change will need a combination of shocks, readiness and narratives, but so far we have only had the shocks. Great piece from Alex Evans

How to shine in Meetings continued [h/t Paul O’Brien]. (Please add to last week’s list)

MSF issued a highly critical report on the state of humanitarianism. Here’s a review of aid workers’ mixed reactions. Oxfam’s Jane Cocking responds here

This could make a really annoying ringtone: Hear the Oldest Song in the World: A Sumerian Hymn Written 3,400 Years Ago.

Two breakneck tours of Britain’s regional accents: this one’s fun, but this one is more accurate [h/t Alan Beattie]

Misheard song lyrics. Let’s ruin some of your favourite songs [h/t Leah Kreitzman]

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers