Duncan Green's Blog, page 180

September 18, 2014

Gallup’s global Well-Being Index. Great data, shame about the (lack of) analysis.

Gallup has just published its Global Well-Being Index, based on a survey of 134,000 adults in 135 countries – i.e. a big exercise. The methodology is rigorous, presided over by Angus Deaton, who also contributes a glowing foreword. The index includes five elements of well-being: purpose, social, financial, community, and physical. Here’s what it finds for the BRICS, for example (headline message, it’s great to be Brazilian, though this survey was conducted before the World Cup):

This is a huge treasure trove of data. Shame then, that the write-up is pretty dull – as far as I can see, just a lot of fairly superficial number crunching with little in the way of interesting analysis or conclusions. Example: rich/health people tend to report higher levels of wellbeing than poor/undereducated ones – hold the front page.

The attempts to explain their finding don’t really go past a series of regional stereotypes and circular arguments: ‘That so many people are reporting positive emotions and higher well-being in Latin America at least partly reflects the cultural tendency in the region to focus on the positives in life.’ Asia’s low scores ‘may partly result from cultural norms as well as from lower development, work environment, and economic issues that affect the wellbeing of respondents in Asia.’ Oh dear.

So in a spirit of ‘where is the knowledge we have lost in information’, here are some of the results.

Global map – headline message: let’s all move to the Americas

Highest well-being countries – headline message: what are they smoking in Panama?

Lowest well-being countries – headline message: it’s horrible being Syrian – who would have thought it?

I’m actually rather disappointed by this – I’m a big fan of measuring well-being, (for example the work of Katherine Trebeck, the OECD and even, previously, of Gallup) and have been covering it on this blog for years. I can’t believe that this much data tells us so little of interest – surely some decent political analysis would have produced some more interesting interpretations? Still, maybe others will now start trawling through the numbers and come up with something more interesting.

I’m actually rather disappointed by this – I’m a big fan of measuring well-being, (for example the work of Katherine Trebeck, the OECD and even, previously, of Gallup) and have been covering it on this blog for years. I can’t believe that this much data tells us so little of interest – surely some decent political analysis would have produced some more interesting interpretations? Still, maybe others will now start trawling through the numbers and come up with something more interesting.

September 17, 2014

The future of DFID, partnerships, aid and INGOs, c/o Alex Evans

Alex Evans always gives good bullet point. A former SPAD (special adviser) to DFID, turned academic/consultant at the Center for International  Cooperation, last week he gave some NGOs a whirlwind tour of his big picture thinking on development, based on a recent submission (with Owen Barder) to the UK parliament’s International Development Committee. Here are some highlights.

Cooperation, last week he gave some NGOs a whirlwind tour of his big picture thinking on development, based on a recent submission (with Owen Barder) to the UK parliament’s International Development Committee. Here are some highlights.

On DFID: Next year is DFID’s 18th birthday, but no bets on it reaching its 21st. Dragging it back into the Foreign Office would be one way to buy off the critics of aid, while sticking to promises on spending at least 0.7% of national income on aid (which may even become enshrined in law). DFID doesn’t necessarily have to be a separate department to be effective in countries, and you could even argue on the basis of Norway and Denmark’s experience that being in the Foreign Office would help promote inter-departmental ‘policy coherence’ on development issues that go ‘beyond aid’ (peace keeping, climate change, tax etc). But given how shallow support is for development, the danger is that the aid budget would rapidly be diverted elsewhere, doubtless with suitable smoke and mirrors from the spin doctors to disguise the fact – and, more importantly, that cross-Whitehall discussions would lose the voice for development and the long view that only an independent DFID, with its own Cabinet minister, can bring to the table.

On partnerships: Lots of talk in the UN, World Bank etc about the wonder of partnerships, usually with the private sector, but they are too often presented as an alternative to policies and regulation. All too easily partnership becomes synonymous with ‘leave it to the market’. Some companies just repackage existing CSR activities as partnerships and try and get a photo op with Ban Ki Moon, but others (Alex cited Unilever, who he’s worked with on the post-2015 agenda) are more serious, and put their core business model and lobbying power behind the initiatives – we need to be much more specific about what the fuzzword ‘partnership’ actually means.

On partnerships: Lots of talk in the UN, World Bank etc about the wonder of partnerships, usually with the private sector, but they are too often presented as an alternative to policies and regulation. All too easily partnership becomes synonymous with ‘leave it to the market’. Some companies just repackage existing CSR activities as partnerships and try and get a photo op with Ban Ki Moon, but others (Alex cited Unilever, who he’s worked with on the post-2015 agenda) are more serious, and put their core business model and lobbying power behind the initiatives – we need to be much more specific about what the fuzzword ‘partnership’ actually means.

On Middle Income Countries: This is where a lot of the action currently is – both in terms of conflict (Syria, Iraq, Nigeria, Ukraine) and protest movements (Egypt, Ukraine, Brazil). So an exclusive focus on low income countries could miss most of the ‘windows of opportunity’ provided by shocks (see below).

The future of aid: Aid donors have a problem: the big challenges are fragile states, inclusive growth in middle income countries, and sorting out global collective action problems from climate change to tax. And they’re not very good at any of them.

The future of INGOs: Alex is a big advocate of shock-driven change, and (like me) laments how bad NGOs are at it. He argues that we need off the shelf policies we can dust off after a shock (nice comparison with those ring binders submarine captains pull out in movies, with their instructions for any given scenario). I would add the need to build relationships and alliances with ‘unusual suspects’ well in advance of the shock, so that the trust is there to allow you to respond rapidly afterwards. See the response to Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza disaster for an example.

But we also need better narratives – an explanatory world view that makes sense of things. He thinks our current narrative has backed itself into an ‘aid will end poverty’ corner, which is not much use for the ‘beyond aid’ discussions. Big narratives often come from charismatic individuals (think Milton Friedman on the economy) but we’re quite suspicious of those. Can collective narratives emerge or are we doomed to ‘Occupy’-type confusion over what world we actually want? Looking further back, the rise of democracy, women’s rights, trade unionism, of the movement to abolish slavery, were as much collective as charisma-led processes. But they may take longer to emerge and we don’t have much time on things like climate change. Alex thinks faith-based narratives may be the best hope we’ve got – they’re established, clearly resonate, and could act as a rallying point even for the non religious (eg what about a Golden Rule coalition, or Global Stewardship movement?)

Alex’s final point was on the limits to insider advocacy as a driver of change (and he is well versed in that). He reckons we need

A larger ‘us’ (identifying with a global public)

A longer future (intergenerational thinking, well beyond short term electoral cycles)

A better ‘good life’ (wellbeing rather than GDP growth)

See what I mean about good bullet point?

Alex discusses his IDC submission here.

September 16, 2014

Why is economic orthodoxy so resistant to change? The art of paradigm maintenance.

Ever wondered why it’s so hard to shift big institutions (and the economics profession in general) on economic policy, even when events so graphically show the need  for change? I’ve just come across a fascinating 2006 paper by Robin Broad, ‘Research, knowledge and the art of ‘paradigm maintenance’: the World Bank’s Development Economics Vice Presidency (DEC)’, summary here. Full paper here. It must be about the oldest thing I’ve blogged on, but I’m interested in what, if anything, has changed in the intervening years.

for change? I’ve just come across a fascinating 2006 paper by Robin Broad, ‘Research, knowledge and the art of ‘paradigm maintenance’: the World Bank’s Development Economics Vice Presidency (DEC)’, summary here. Full paper here. It must be about the oldest thing I’ve blogged on, but I’m interested in what, if anything, has changed in the intervening years.

Broad explores the nature of what Robert Wade call’s ‘paradigm maintenance’, describing an elaborate system for creating, maintaining and propagating what she calls the ‘neoliberal paradigm’ (this is 2006, after all) within the Bank. None of that system is explicit. Broad interviews a number of Bank insiders as well as ex-Bankers and illustrates her findings by contrasting the fates of two then Bank economists – David Dollar, arch spin doctor for the neolibs, and Branko Milanovic, inequality guru and general stone in the neoclassical shoe.

Broad identifies 6 components of paradigm maintenance:

Hiring: the DEC overwhelmingly hires economists with PhDs from US or UK universities

Promotion: the Bank has a similar system to academic tenure, and for that economists need to get published in the right journals, as well as by the Bank itself

Selective enforcement of rules: dissident research generally undergoes not just stricter external review, with occasional rejection, but an intriguing ‘stonewalling’ exercise that grinds down would-be boat rockers. Here’s how some interviewees described it:

Your research manager says ‘I don’t want to deal with this’…. Either he ‘won’t clear it or he will say that you need to send it to the ‘center’. Or, if it is a newspaper op-ed, he ‘passes it to the External Affairs person in DEC.’

After a long time there is no response. So, you call him

And he says the piece is ‘not helpful to the debate’ or ‘the debate has moved on’.

And you say ’But doesn’t the fact that they want to print it show that there’s someone still interested in the debate?’

And he never says ‘no’ but never clears it

If, as does sometimes happen, the researcher opts to publish without sign off, they expose themselves to censure (unless of course, their unapproved pieces are on message).

Are those prison bars?

Discouraging dissonant discourse: Dissidents are labelled ‘idiosyncratic’, ‘disaffected’ and otherwise deemed a misfit. According to Nicholas Stern, a former economist, ‘there is a strong hierarchy and an atmosphere much more deferential than would be found in universities.’ Criticism of work from outside the Bank, like the comprehensive rubbishing of some of Dollar’s key papers, fails to penetrate the institution

Executive Summaries and Press Releases that don’t reflect the main report: an old favourite – since journos almost never read the whole thing, there is huge room to drag reports back on message by distorting their presentation.

External Projection: The Bank’s External Affairs Department gets behind the good guys, and ignores the trouble makers.

What’s interesting is the treatment of dissidents like Branko. They are sometimes de facto dismissed/managed out (Stiglitz for criticising neoliberalism, Easterly for being rude about aid, while Ravi Kanbur left after unreasonable pressure to tone down his views on globalization), but if they are not too high profile, the Bank parks them on the fringe of the institution, depriving them of platforms and resources. In contrast, on-message economists like David Dollar get the full works, in terms of media promotion, airtime at major events etc etc.

What this produces is a knowledge system that is extraordinarily resilient to any attempt to move it from its current ideological direction. Even if the new(ish) boss has a more pluralist approach to life, the universe and economics, how much power does Jim Kim have to take on and vanquish this kind of entrenched establishment?

And of course, the Bank is immersed in a wider system involving economics faculties, journals and former pupils in positions of power, all of whom see themselves as guardians of the flame of orthodoxy. No wonder everyone from Queen Elizabeth to angry Manchester economics students is asking why inconvenient facts like the global financial crisis have had so little influence on the way the economics establishment thinks and (more importantly) advises others.

And in a spirit of even handedness, I should say that I recognize some of these mechanisms in play in NGO land too!

I sent this post over to Branko, who recently left the Bank, and here’s what he said:

‘I think that all these mechanisms as described by Robin were operational in 2006. I think (but I am not sure) that the situation is a bit better today. The main reason is that the dominant paradigm was seriously affected by the financial crisis, and even more by the persistence of low growth in Europe, as well by the rise of the previously unorthodox topics like inequality. In such conditions, I think, we have more of a “let a hundred flowers bloom” atmosphere than in 2006.

If I am right, the conclusion is that the paradigm shifts when the contrast with the observed reality becomes too big to ignore. And when it happens in the outside world, the Bank just cannot ignore it. A bit like the Kuhnian story of paradigm change.’

Robin Broad was less positive:

‘I wish I could be as optimistic, but alas, not much seems to have changed, or at least not in any significant way (although it is significant that Branko has left the Bank.) Your readers might also be interested in how the World Bank reacted to my research (from a subsequent piece in Development in Practice):

‘After the original, longer academic article on DEC appeared in a peer-reviewed academic journal, two gentlemen from the Bank contacted the journal’s editors. Although I was not privy to the communication, I gather that the gentlemen found my scholarship to be ‘poor’ and the journal’s review process wanting if such an article could be published. The editors (who had, in fact, overseen a rigorous review process) offered journal space for the two to rebut my article, with the understanding that I would then be given the customary academic opportunity to reply. But such open academic debate appears not to have been to the liking of the complainants – who feared, I infer, that it would give my article further prominence.’

So over to you – has the Bank changed (and you can comment anonymously, if you happen to rely on it for your mortgage)? Has social media led to greater pluralism (hey, I regularly appear on the Bank’s governance blog)? Are other aid/development institutions any better or worse?

September 15, 2014

Not so mega? The risky business of large-scale public-private partnerships in African agriculture

Oxfam policy adviser Robin Willoughby shrugs off the big ag groupthink and argues that the current trend of mega projects in African agriculture is a risky and unproven way to help poor farmers.

risky and unproven way to help poor farmers.

Last week, I attended a large summit on the future of African agriculture in Addis Ababa, hosted by A Green Revolution for Africa (AGRA).

My participation really made me reflect on the problems of ‘groupthink’ within these types of conference, with each of the participants taking it in turns to stand on the podium and agree with one another more and more vociferously. The buzzwords were ‘investment opportunities’, ‘transformation’ and ‘public-private partnerships.’

This narrative is to be expected at a private sector agri-investment conference – but seems confusing when this type of meet-up is designed by philanthropic organisations to address rural poverty and the widespread challenges in African farming. Despite the worthy aims of AGRA, discussion of poverty, rights, gender or inequality was almost entirely absent from the plenary.

As one of the other participants said to me: “if everything is going so well – why are we all here?”

At the summit, I launched an Oxfam Briefing Paper on large-scale public-private partnerships initiatives, which echoes some of these themes.

The report points out that despite the large amount of hype around mega-PPPs such as the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, GROW Africa, and numerous growth corridor initiatives – there is very little robust evidence on the proposed benefits of these arrangements, around who bears the risks or who holds the power in decision making.

So where do the risks and benefits lie?

The paper shows that public-private partnerships can play an important role in supporting farmers. For example, smaller-scale initiatives such as micro-credit, weather-index insurance and attempts to link farmers into markets offer useful examples of PPPs – particularly when they are co-designed with end-users and local communities.

The paper shows that public-private partnerships can play an important role in supporting farmers. For example, smaller-scale initiatives such as micro-credit, weather-index insurance and attempts to link farmers into markets offer useful examples of PPPs – particularly when they are co-designed with end-users and local communities.

Oxfam’s work with consumer goods company Unilever in a targeted partnership called Project Sunrise shows that well-designed partnerships can also be used for innovation and learning.

But the risks of mega-PPPs are enormous, particularly in the areas targeted for investment.

Threats to land rights:

Land transfers are a core component of the mega-PPP agenda. The total amount of land pegged for investment within just five countries hosting growth corridor initiatives (Tanzania, Mozambique, Malawi, Ghana and Burkina Faso) stands at over 750,000 km² – the size of a country such as France or Ukraine.

Not all of this land will be leased to investors, but the initial offering in these countries stands at 12,500 km² (over 1.2 million hectares) – the amount of land currently in agricultural production in Senegal or Zambia.

In the context of weak land governance and insecure land tenure (estimates suggest that only 10 per cent of rural land in Africa is registered), there is a serious risk that mega-PPPs will lead to the dispossession or expropriation of local communities in the name of investment.

The pricing of land can also be set at extraordinarily low levels. The GROW Africa initiative advertised land for lease in Mozambique for $1 per hectare per annum over 50 years. This is around 2,000 times cheaper than comparable land in Brazil – raising concerns that African governments are seriously undervaluing their core assets.

Worsening inequality:

Inequality is already significant in Africa. Measurements such as the Gini-coefficient show that inequality on the continent is second only to Latin America in its severity.

Land transfers to investors threaten to worsen this inequality by creating ‘agricultural dualism’ between large and small farms. This process will remove  already diminishing plots of land from family farmers; while the co-existence of large and small farms has been shown to drive inequality and conflict in other contexts.

already diminishing plots of land from family farmers; while the co-existence of large and small farms has been shown to drive inequality and conflict in other contexts.

Also, equitable agricultural development requires diverse forms of support to account for ‘different rural worlds’, including contract oversight for commercial producers, the development of local markets for poorer farmers, and job-creation and social protection for marginal groups.

Mega-PPP projects are unlikely to deliver this type of agenda, instead focussing on wealthier, more ‘commercially viable’ farmers and bigger, politically well-connected companies.

Asymmetries of power:

Finally, for any form of large-scale public-private partnership to be effective, it requires effective governance to ensure a fair sharing of risks and benefits; and regulation to ensure that more powerful players do not use political and economic clout to capture a dominant position in the market.

These conditions of good governance do not exist, on the whole, in most African countries.

The asymmetries of power within these arrangements can be enormous. In the SAGCOT programme (a mega-PPP in Tanzania), four large seed and agrichemical companies involved in the initiative have combined annual revenues of nearly US$100 billion. That is more than triple the size of the Tanzanian economy.

This raises serious concerns that these companies could lobby for policies that are in their interest and squeeze out small- and medium size enterprise from burgeoning domestic markets.

What are the alternatives?

Is there an alternative to the mega-PPP vision of agricultural development? I think so:

Public sector investment in research and development, extension services and targeted subsidies for credit can spread the benefits of agricultural investment widely and encourage private sector participation in the sector. Currently, governments in Sub-Saharan Africa only spend 5 per cent of their total annual budget on the sector, which is unforgivably low.

Securing land rights for local communities. This will help to ensure that communities within the target area for these schemes are not dispossessed in the name of investment. Secure land tenure also encourages smallholders to invest for themselves in land and productive activities.

Finally, alternative business models such as the development of producer organisations and the clever use of subsidies to encourage local processing facilities can develop agricultural markets without the need for ‘hub’ plantation farms or growth corridors. These models should be explored in more depth as part of a more inclusive PPP agenda.

With some US$6 billion of donor aid committed to further the aims of the New Alliance and $1.5 billion earmarked for growth corridor initiatives, mega-PPPs lead to a fundamental question. Would this money be better spent on lower risk models of agricultural development that give a greater share of the benefits to the poor?

September 14, 2014

Links I liked

Wait, don’t start work – check out this pick of last week’s @fp2p twittercrop instead.

Global Median Ages: Niger the youngest (15); Japan/Germany the oldest (46) [H/t Ian Bremmer, Tanja Hichert]

If you’re interested in governance, political economy etc, Matt Andrews at Harvard is putting up a blog post, video and powerpoint after each lecture in his ‘getting things done‘ course.

Extraordinary and hellish journey of Solomon, an Eritrean refugee now in UK, and how he got there. Ends happily.

See the will to live drained from these dead eyes. Harrowing. Photos of Dads at One Direction concerts. [h/t @meowtree]

See the will to live drained from these dead eyes. Harrowing. Photos of Dads at One Direction concerts. [h/t @meowtree]

Identity politics is the new opium of the people, argues Dani Rodrik (with lots of data). It explains why people keep voting against their economic interest

Why ‘evidence-based policy’ is nonsense, but evidence-informed is a good idea. Kirsty Newman explains wrt the Scots referendum & eating cake

I’ve stopped watching TED Talks but make exception for Hans Rosling & son Ola on why we underperform against chimps (and how to fix it)

And some random links and clips on the big event this week (at least in the UK, and probably Barcelona) – the Scots referendum on independence

First, a burning question – what do Scottish aristocrats think? (hint: not keen). By the Tatler’s delightfully named Sophia Money-Coutts.

A brilliant 8m finale from ‘The Pitiless Storm’, which I saw at the Edinburgh Festival last month. David Hayman plays a lifelong Labour Party stalwart about to receive an OBE who suddenly changes his mind. On everything.

Finally, this unforgettable rant on ‘being Scottish’ from Trainspotting. Wonder which way they would vote?

September 11, 2014

What can we learn from big advocacy initiatives in the Philippines on education, violence against women, reproductive health and freedom of information?

Ahead of next week’s Thinking and Working Politically seminar, here’s another case study from The Asia Foundation, which has got some impressive  advocacy results in the Philippines. Room for Maneuver (book and research brief) examines four social policy reforms to try and draw lessons for advocacy work. They are

advocacy results in the Philippines. Room for Maneuver (book and research brief) examines four social policy reforms to try and draw lessons for advocacy work. They are

1. The successful passage of the Anti-Violence Against Women and their Children Act in 2004;

2. The successful passage of the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act in 2012;

3. The thus far unsuccessful effort to introduce a Freedom of Information Act; and,

4. The politics of introducing and passing the Governance of Basic Education Act in 2001.

Here are some highlights from the research brief:

Analytical Framework

‘The case studies use a conceptual framework that draws on the long-running debate in political science concerning the relationship between “structure” and “agency” to understand the process that shape social sector reform outcomes. Structure refers to both the broad features of the economic, political, and social structure of a society, sector, or reform issue, as well as the formal and informal institutional arrangements that shape (but do not necessarily determine) behavior within a given domain. Agency refers to the intentions, capacities, and abilities of actors (individuals, groups, organizations, or coalitions) to think and act strategically.

Given the importance of “leadership” in policy reform efforts, the cases also analyze the manner in which leaders mobilize people and resources through a variety of forms of coalition building.

Lessons from Social Sector Reform Cases

While the idiosyncrasy of social contexts is a given, there are recognizable patterns that surface repeatedly. The role of conjunctures, largely exogenous moments that change the political landscape, is one example. The human actors who labor painstakingly to enable alternative futures for serious consideration and the coalitions these actors bring to life are another. Inherited rules and institutions, both formal and informal, that safeguard social stability, but can also be employed by vested interests to frustrate challenges are also common elements in the landscape of social change. In each case, local leaders, elites, and coalitions—at times with support from international development partners, and other times self-funded—found the room to maneuver within the structures and constraints to achieve their desired outcomes.

Based on analysis of the four case studies we have identified eleven main lessons:

Based on analysis of the four case studies we have identified eleven main lessons:

1. Reform processes are often long and complex. The effort to pass anti-VAWC legislation began in earnest in 1996 and took eight years of concerted effort to pass. Through the process, there were serious disagreements and divisions among advocates that almost scuttled the advocacy. The legislative battle for a framework for reproductive health lasted over two decades. The ongoing campaign to flesh out the constitutional provisions on freedom of information can be traced back to 1998.

2. Reform processes are typically non-linear. While there are formal steps to approving a law, there are unpredictable events and conjunctures. Perennial power realignments in the political system generally serve to attenuate reform processes. However, such realignments can also throw up new opportunities, and capitalizing on trigger events, windows of opportunity, or reform conjunctures can dramatically improve advocacy’s likelihood of success. In the case of the anti- Violence Against Women and Children Act, sensational episodes of violence against women, however unfortunate and disturbing, were effectively turned into tipping points to advance the cause. Previous efforts to create a comprehensive government policy and program on reproductive health had been stymied by an effective opposition. But the election of a new president supportive of the measure was a key conjuncture that favored reform.

3. Reforms need to be technically sound and politically possible. A crucial part of the reform advocacy is identifying and convincing reform allies and policy champions to use their political capital in driving change. Reform agendas compete over the use of scarce political capital. Building trust and understanding the motivations and interests of political actors is an important element of engagement.

4. Effective coalitions and networks are essential to reform. In each of the successful reform cases studied, strong bonds between civil society reformers and groups within government were critical for success. The coalition supporting the Reproductive Health Bill was sufficiently broad and united to counteract strong opposition during the final legislative process. It was resilient enough to overcome internal disagreements arising from the broad, diverse nature of the coalition membership. The delicate integration and management of advocates of diverse perspectives, especially the partnership between political elites and mass-based organizations, affords reform coalitions both the competence and constituency needed to convince government leaders to intervene.

5. The role of values and motivations in reform coalitions is unclear. The importance of having shared values and motivations among all reform coalition members is unclear. Some advocates believe that successful reform is achieved by establishing a shared set of clearly articulated values that can serve as a basis for coalition unity and longevity. To others, the importance of building a formal coalition based on a consensus of core values is unnecessary. There are many motivations for supporting a reform and participating in a coalition and sincere commitment to achieving a desired reform is more important than having a shared set of values and motivations.

6. Passionate, well-connected leaders drive change. While networks and coalitions provide credibility and support for the reform initiatives, these groups are usually being driven and sustained by key individuals. In the anti-violence against women and children and the reproductive health reforms, leaders were able to broker trust-building and collaboration among various advocates that did not agree with each other on a number of issues.

7. The chief executive is important but there are limits to presidential power. The cases highlight the critical role that the president plays in  determining the legislative process. The likelihood of a legislative reform bill making it into law increases significantly when the issue is designated as a priority bill by the president. [But] Even with presidential support, passage is not guaranteed. Strong public support for the RH bill eventually enabled President Aquino to secure the necessary legislative majority against strong opposition from the Catholic Church. On the other hand, less clear public support coupled with the President’s own misgivings have meant that passage of the Freedom of Information bill has not been prioritized.

determining the legislative process. The likelihood of a legislative reform bill making it into law increases significantly when the issue is designated as a priority bill by the president. [But] Even with presidential support, passage is not guaranteed. Strong public support for the RH bill eventually enabled President Aquino to secure the necessary legislative majority against strong opposition from the Catholic Church. On the other hand, less clear public support coupled with the President’s own misgivings have meant that passage of the Freedom of Information bill has not been prioritized.

8. Framing the issue in a non-confrontational manner avoids unnecessary controversy. Reframing the issue of population policy as a reproductive health reform rather than a population control issue swelled the ranks of the coalition and garnered enough support to overcome opposition to the bill.

9. Reform strategies require flexibility. While policy reform advocacy needs to be well planned, advocates should also be able to quickly adjust to shifting political realities and change tactics as needed on the fly. Changing realities may call for compromises and advocates need to be ready to compromise.

10. External technical and financial support can be helpful. Policy advocacy can be an expensive battle and reform advocates often work with very limited funds. Support from donors can make a great difference. By the same token, donors need to be sensitive to the needs and preferences of the reformers and not to impose overly onerous conditions on them. Program design should be sufficiently flexible to enable quick intensification of support during unexpected windows of opportunity.

11. Align the stars and connect the dots. Successful social sector reform requires interlinked political, public, and advocacy constituencies to come together. A president is unlikely to spend his political capital on a bill that does not have clear public support or a high probability of passing both Houses of Congress. The experience of the RH reform demonstrates how, when the political, public, and advocacy stars align, even contentious and divisive reforms can be successful.’

Postscript: I ran this past a Filipina activist friend. Her response:

‘I am not sure about number 8. Framing it also as RH (rather than pop’n control) was controversial and much more confrontational with the Catholic Church. Advocates knew that. I think the RH framing is actually a win for women’s rights advocates – a product of long debates and discussions within the broad network of groups and alliances. The result was a united front, and this framing of rights got the full commitment of women’s rights groups, LGBT groups and those working in rights based issues.

I also wonder whether the role of community organizations and grassroots groups is downplayed. They played a huge role both in the VAWC and RH campaigns. They were the constituency, the faces that showed the impact and the need for the policy. They were the ones who filled the streets and demonstrated and gave the networks/ NGOs the mass support for the measure.’

Success has many fathers/mothers, while failure is an orphan. So let’s see what other participants have to say.

September 10, 2014

R2P RIP? Painful reflections on a decade of ‘Responsibility to Protect’

Ed Cairns, Oxfam’s senior policy adviser on humanitarian advocacy, bears his soul on whether R2P has a future, or is best consigned to the dustbin of  history

history

Nine years ago this month, the UN World Summit endorsed the Responsibility to Protect. But this summer’s bloodshed in Gaza was only the latest conflict to provoke a heated debate on whether the concept still has a future. In one corner, the journalist David Rieff argued that R2P wasn’t a useful framework for Gaza – or anywhere else. While the head of the Global Center on R2P stressed the opposite, that ‘both the Israeli government and Hamas have a responsibility to protect [the] civilians’, but have failed to do so. Ban Ki-moon’s own Special Adviser on R2P, the Oxford academic Jennifer Welsh, challenged both sides for their ‘violation[s] of international humanitarian law and international human rights law… [that] could constitute atrocity crimes’.

This is not another Gaza blog. This is an R2P blog from someone who grew up working on the terrible humanitarian crises of the ‘90s (the Rwandan genocide perhaps the most terrible of all), and was an evangelical advocate when Oxfam campaigned for governments to adopt R2P in 2005. But for most of the years since then, R2P has been a rare three-letter acronym in Oxfam’s campaigning.

Again and again, we’ve argued that every civilian must be protected from what seems like the rising tide of atrocities in conflicts from Syria to South Sudan. Sometimes governments respond. Sometimes they don’t. But we have seldom, if ever, found R2P an argument that persuades them to act when they otherwise wouldn’t.

Perhaps it seems that nothing can compel governments or the international community to protect civilians as much as they should. But sometimes, at least, active citizens – as this blog regularly reminds us – can persuade governments to act differently. Where millions of people have campaigned to control the arms trade, enormous changes have been made. Public opposition to fuelling Syria’s conflict with more arms has had a practical impact on at least some governments’ policies.

Perhaps it seems that nothing can compel governments or the international community to protect civilians as much as they should. But sometimes, at least, active citizens – as this blog regularly reminds us – can persuade governments to act differently. Where millions of people have campaigned to control the arms trade, enormous changes have been made. Public opposition to fuelling Syria’s conflict with more arms has had a practical impact on at least some governments’ policies.

Yet those millions who raise their voices seem motivated by images and stories of human suffering, rather than an abstract global concept such as R2P. Or at the very least, we haven’t found a way to make that work.

R2P is ‘down but not out’, as one of its founders, Gareth Evans, has said, because of ‘the breakdown of trust’ that occurred once the US, UK and France were seen by other governments to have used R2P to justify not only protecting civilians, but removing a regime in Libya in 2011. As Evans says, that trust may one day be rebuilt. But three years on, there is little sign of it. And until that happens, it is difficult to see how to prevent R2P from being misapplied – by any government – for reasons that go beyond the prevention of atrocities.

All this leaves Oxfam increasingly cautious about invoking R2P in any current case – despite our support for the principle and enthusiastic campaigning  for its adoption nine years ago. I’ve just written up our evolving approach in the journal Global Responsibility to Protect in a special issue on R2P and humanitarian action (gated, but the enlightened publishers are happy for me to upload this draft:).

for its adoption nine years ago. I’ve just written up our evolving approach in the journal Global Responsibility to Protect in a special issue on R2P and humanitarian action (gated, but the enlightened publishers are happy for me to upload this draft:).

More importantly, where does this leave R2P? First of all, let’s be clear on one thing. Its principle is absolutely right. Governments and the world do have a responsibility to protect people from genocide and other mass atrocities. Ban Ki-moon’s latest report on R2P, released in August, offers a long list of sensible recommendations for how the international community should help governments do that – not least addressing the inequalities and exclusion that can help create a climate in which atrocities are more likely. It reaffirmed that all the so-called R2P ‘pillars’ were important, including the need sometimes to use force against those governments who choose to kill rather than protect their own citizens. And yet when the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, gave her valedictory report to the Security Council in late August, she mourned the ‘hundreds of thousands of lives’ that have been lost because the Council has failed to take ‘firm and principled’ action to stop atrocities. If R2P was meant to change anything, was it not meant to change that?

too glib?

It would be too glib to say that R2P is dead. If we gave up on every international agreement that wasn’t instantly successful, we would live in an even more dangerous world. Much of today’s violence – and the world’s inaction in the face of it – rides roughshod over R2P. But it also rides roughshod over international humanitarian and human rights law. Yet taken as a whole, such international rules have had an effect. They have helped prevent human rights abuses and violence being even worse, and given citizens around the world something against which they can at least try to hold their governments to account. This is absolutely not the time to give up on R2P or the international law on which it is based.

And yet as someone once so enthused by R2P, I’m left with this uncomfortable question. Can I think of real lives in a real crisis that have been saved because the words ‘responsibility to protect’ have been invoked? Some would argue that Libya and Cote d’Ivoire in 2011 qualify. Perhaps, but even if that was true, that is several years ago. What of the atrocities happening today and facing thousands of civilians tomorrow? I’d love to hear from others of how useful they have found R2P in their work in real crises.

September 9, 2014

How to write about development without being simplistic, patronising, obscure or stereotyping

It’s all very well writing for wonks, but what about the poor comms people who have to make all those clever ideas about nuance, context, complexity etc etc accessible to people who don’t spend all day thinking about this stuff? Oxfam America’s Jennifer Lentfer has a good piece on this on her ‘How Matters’ blog, discussing her work with a class of international development communications students. Her central question – ‘How can a new generation of communications professionals embrace nuance without turning the public off? (After all, nonprofits are competing against cat videos)’

etc accessible to people who don’t spend all day thinking about this stuff? Oxfam America’s Jennifer Lentfer has a good piece on this on her ‘How Matters’ blog, discussing her work with a class of international development communications students. Her central question – ‘How can a new generation of communications professionals embrace nuance without turning the public off? (After all, nonprofits are competing against cat videos)’

To answer it, she, and a bunch of others, have put together ‘The Development Element’ – a nice new guide to post-patronising comms. Here’s their summary of the main messages:

To which I would add a further don’t – don’t publish documents in green that are almost unreadable when people print them out to read on the bus……..

I think there is something else going on here – in an age when people are used to absorbing fragmented messages, we need to get better at telling parts of the story well, rather than thinking we have to tell the whole story every time. We could be much better at simply ‘bearing witness’, including by getting out of the way – webcams in every refugee camp? Follow an activist’ twitter feeds? It’s OK to publish a great killer fact that illustrates a problem without feeling compelled to add several pages of unread recommendations about how to put it right.

And yes, I realize this is a bit rich from someone who writes 500 page books……

See also this Guardian piece from Jonathan Tanner, then of ODI on the tension between complexity and comms.

Update: I have a nagging feeling that I overpromised in the title for this post – this report is good, but doesn’t quite nail it. What other advice would comms people offer?

September 8, 2014

Can donors support civil society activism without destroying it? Some great evidence from Nigeria

The Thinking and Working Politically crew are reassembling next week to discuss how better to apply power analysis, political economy etc in the  practice of aid, so I thought I’d highlight a couple of good examples in advance.

practice of aid, so I thought I’d highlight a couple of good examples in advance.

First up is some really exciting work from DFID’s State Accountability and Voice Initiative in Nigeria, which suggests that even big donors can successfully support citizen engagement with the state. This is important because gurus such as David Booth have questioned whether donors are just too cumbersome to do this, while academics such as Masooda Bano have shown how chucking money at genuinely grassroots civil society organizations in Pakistan destroys them within months (because their members promptly assume the leaders will run off with the money and leave).

But SAVI reckons it can be done:

Whilst most demand-side governance programmes support civil society groups through grants and limited capacity building support, SAVI has shifted the aid modality – the way the programme achieves its objectives – to facilitation and knowledge sharing. This approach recognises that the demand-side governance challenge is about institutional blockages and related capacity limitations, more than it is about funding gaps.

Planning and decision-making in SAVI is largely decentralised to state-level programmes and state staff are recruited, trained and supported to work as hands-on facilitators of locally-driven change. They provide seed money for partners’ initiatives in small and diminishing amounts, but focus largely on tailored learning and mentoring processes that build partners’ functionality and effectiveness as agents of citizen voice. Support is tailored to address gaps in partners’ knowledge, skills, and working relationships that they themselves prioritise through regular self-assessment, learning and reflection processes.’

‘Staff and partners are supported to conduct political economy analyses, and update political intelligence, themselves. One [state level] SAVI member of staff describes why:

“We wanted to know the history of politics which is shaping current thinking… the things that drive the development agenda from politicians’ point of view. Where is the direction of government? Traditional leaders – do they really have power? What kind of power can they give you..? Information goes round. People will be telling you you’d better go and talk to him…Through informal contacts you can get to understand the mindset of the people in power and you get at the informal system of power. You need to know where to pitch your tent.’

To help a widely dispersed network of staff and partners, SAVI came up with rather a nice theory of change (see pic): Consisting of

To help a widely dispersed network of staff and partners, SAVI came up with rather a nice theory of change (see pic): Consisting of

Glass half full: start by understanding the system and players who are already there

House: help partners get their own house in order, build their networks etc

Triangle: help bring together citizens, politicians and media to start building trust and connections

Bridge: build constructive engagement between citizens and state governments, including power analysis and experimental ‘learning by doing’

Wedge: on the basis of the first four stages, adapt and spread successful approaches, e.g. to new issues or neighbouring states

Explosion: generate a critical mass for change, then stand back and POW (I assume this bit hasn’t actually happened yet).

This is illustrated with 3 nice case studies: budget analysis and advocacy in Kaduna State, monitoring government projects for corruption in Jigawa state, and this very nice example of disability advocacy in Lagos state:

‘SAVI state staff brought together the Lagos Civil Society Disability Policy Partnership (LCSDPP). Members included people with and without disabilities, who had previously worked individually and competed for donor funding to bring about change. SAVI state staff assisted partners to work together, strategize in a politically intelligent way, and work effectively and extensively with the media and with elected representatives.

It took a long time and painstaking support for LCSDPP partners to unlearn their ’placard carrying’ mindset, and focus instead on constructive  engagement with the state. Equally, it took time and subtle advocacy from group members to convince stakeholders in the state government to participate in a process of constructive engagement with civil society. The group were able to identify key potential partners in the state government and the SHoA, including first time elected representatives keen to meet the expectations of their constituents.

engagement with the state. Equally, it took time and subtle advocacy from group members to convince stakeholders in the state government to participate in a process of constructive engagement with civil society. The group were able to identify key potential partners in the state government and the SHoA, including first time elected representatives keen to meet the expectations of their constituents.

The group successfully championed the Lagos State Special Peoples’ Law on disability rights, passed by Lagos House of Assembly as its first ever private member’s bill.

LCSDPP applied their ability to think and act politically and ‘work with the grain’ to consider how they might get the governor’s attention and support:

“When it came to the Governor, [the group considered] what does the Governor listen to? What kind of programme does the governor watch on TV? What newspapers does he read, which programmes does he monitor, where does he worship, who does he hang out with? The Governor is someone who plays football – the group did analysis of all of that. They started engaging with people around him to attract his attention. He became directly interested in their cause and called twice – once live on a radio phone-in and once on TV. He made a commitment on air to meet with them. This was their entry point to build on.”

Conclusion?

Changing the aid modality has a number of benefits. Because there are no grants of the usual kind, there is no call for proposals, no partners’ results frameworks or donor reporting requirements – and therefore none of the dangers of elite capture and diversion from locally rooted efforts that these complex procedures commonly entail. Direct support to citizens’ own initiatives is made possible without the danger of grant funding monetising citizens’ engagement with their government or distorting and weakening their incentives for engagement.’

Brilliant stuff. My only question (not answered in the paper) is whether this kind of labour and knowledge-intensive project spends enough money to meet with approval within DFID, which is under huge pressure to ‘do more with less’. Alas, no mention of budget in the paper. If you can find the time, do read the whole paper – it’s only 8 pages.

September 7, 2014

Links I liked

The usual Monday morning excuse not to start in on your emails. Twitter highlights from last week’s @fp2p feed.

What academics are really saying [h/t Conrad Hackett]

What happens when you try to give a rich person $2? A nice experiment on donorship, poverty and power [h/t Farida Bena]

There were good punch-ups & polemics:

Global Fairtrade sales reached £4.4bn following 15% growth during 2013, but promptly got a bashing from Ndongo Samba Sylla for ignoring the poorest producers, and then fought back

Alan Beattie and Jeff Sachs trade blows on whether Bhutan’s ‘Gross National Happiness’ metric is just a figleaf for autocracy

Extraordinary broadside from Robert Chambers accusing DFID of losing the development plot, and Payment by Results as proof. (Haven’t seen any responses yet – let me know if I’ve missed them)

And a more good natured debate on Open Democracy on the strengths and weaknesses whether social media is really transforming politics. Stephen Hopgood is sceptical. Cristina Maza reckons its big potential is for building ‘power within’.

Humans of Palestine: photos that celebrate the everyday, not the bang bang.

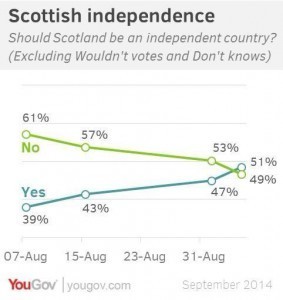

Just 10 days to go til the Scots independence referendum, and the vote is getting unexpectedly close. Personally, I’m on the fence (but I don’t have a

vote). Here’s ‘I want to break free’. Sharp 90 sec referendum Scotland Megamix. Shame it’s from Sky. Oh well.

Not really a link I liked, but thought you might like to see my garden – the backdrop to me droning on about development for 25m to a student economics website. See that little wall? I built that – best DIY I’ve ever done (not much competition, mind)

And while we’re on personal stuff, a proud Dad plug for this piece on women and climate change in Bangladesh from son Finlay

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers