Duncan Green's Blog, page 179

October 1, 2014

This Sunday, Brazilians decide between two progressive women presidents. How do they compare?

Oxfam’s country director, Simon Ticehurst (right), fills in the  background ahead of this weekend’s election

background ahead of this weekend’s election

Some colleagues asked me this week, what is going to happen in the elections and who should I vote for?

First up, prediction is not my forte. Last year in June I sent an optimistic briefing on Brazil to Oxfam´s CEO, saying that poverty was coming down, inequality was coming down, hunger had been largely dealt with, Brazil had full-employment, the happiness index was on the increase, and the Brazilians were generally happy with their lot. A week later 1.5 million people were on the streets across 15 cities in the biggest protests for decades. In my defence, no-one predicted that, just as no-one can predict the outcome of next week´s elections (with a second round toward the end of October). It is too close to call.

Brazil is going through a most unusual electoral process. Not least, because we have two women from humble origins and a leftist background as the frontrunners, the incumbent Dilma Rousseff and former environment minister Marina Silva. I don’t think I have seen that anywhere. For Brazil and Latin American this is an important symbolic moment for women’s political leadership.

What Simon missed

What was a done deal a couple of months ago with Dilma Rousseff´s victory a matter of course -despite the debacle of Brazil losing 7-1 to Germany (football was never going to be the determining factor) now looks like a technical draw. Since presidential candidate Eduardo Campos died in August, Marina Silva, who was running as vice-president, has ridden a wave of emotional support and captured much of the anti-PT vote. Eduardo Campos was the new generation of the left, allied to Lula, he split when Lula favoured Dilma Rousseff in the last elections. His tragic death in an air crash has generated a wave of emotion, which, combined with Marina Silva´s own appeal, has catapulted her to her current position.

Polls have swung back a little this week toward Dilma who looks like she might win the first round, but it is not clear who would win in a second- round run-off. Up until this week, polls had Marina winning that. Now it is has swung back toward Dilma. But it is too close to call.

So who to vote for? One of the legacies of last year´s protests is that people are talking about change and a new political cycle of reform. Things cannot carry on as they are and it is clear that the economic model is running out of steam (Brazil has slipped into recession) and Brazil´s democracy needs overhauling. Everyone wants change. But I don´t think either candidate will be able to deliver on the changes needed.

Marina has the advantage and disadvantage of having published her proposed government programme, a lengthy document which has some good and

Dilma left; Marina right

bad stuff and some inconsistencies. The PT has a shorter call to action building on the positive changes of the past 12 years and promising “More Change – More Future.”

Marina is pushing a more liberal economic programme, stimulating private investment and trade liberalization, and free-trade agreements with the US and Europe and closer association with the Pacific Alliance. For those of us that worked on the Make Trade Fair campaign this is a step backwards, and she clearly has private sector backing for this agenda. We know who would benefit from this agenda, and it won´t be the poor. Marina´s strengths lie in a push for political reform and how she is challenging the political corruption that has corroded the PT in power. Obviously her environmental credentials are second to none and this appeals to youth. However she will also have to make unholy alliances in order to survive and get anything through Congress. And the fact that she entered the fray with a party that until recently was a PT ally, dilutes the newness of the idea of a citizens “network” as a new political expression for the democratic process.

One contentious issue is Marina Silva´s evangelical background, for which she is sometimes attacked. In addition to backing a neo-liberal economic agenda, this enables her to bring a neo-conservative, anti-abortion and traditional family caucus into her “unholy” alliance (which the PT also has to do to govern). But I am not sure that this is the defining feature of Marina Silva (after all she does come from a PT background).

Part of Marina´s appeal comes from her almost spiritual aura. She can move an audience, she has charisma and stage presence. My daughter Sarah had to translate for her at a civil society event at Rio+20 and struggled to control the emotion enough to translate. For young, intellectual, urban middle classes, less groomed in the class struggle and who want to save the Amazon, Marina is a hero. And her humble origins may also bring support from the poor northeast (which is where Eduardo Campos was from). Marina´s government would also continue the PT’s much-praised social programmes .

Part of Marina´s appeal comes from her almost spiritual aura. She can move an audience, she has charisma and stage presence. My daughter Sarah had to translate for her at a civil society event at Rio+20 and struggled to control the emotion enough to translate. For young, intellectual, urban middle classes, less groomed in the class struggle and who want to save the Amazon, Marina is a hero. And her humble origins may also bring support from the poor northeast (which is where Eduardo Campos was from). Marina´s government would also continue the PT’s much-praised social programmes .

Dilma is the incumbent and offers the continuity of the PT’s gradual reformism. Her programme centres around maintaining a stronger role for the State in economic and development management, with substantial social programmes funded by a neo-developmentalist agenda that pursues economic growth through big infrastructure projects, agribusiness, energy and mining (until recently, quite successfully). It is this reliance that is challenged by the environmentalists. A second term in office for Dilma would probably mean some political reform and attempts to lighten the bureaucratic burden of the state through greater decentralization. Corruption is a big issue that seems to galvanize the anti-PT vote and is swaying middle-class opinion. Certainly more needs to be done. But I actually think Dilma has been good in tackling corruption – the fact that it is so high on the agenda is because finally someone is doing something about it. Corruption is not the problem, it is what you do about it that matters. Despite everything the PT has done, much more is needed. Politics can be a thankless task – it is the same emerging middle class millions that the PT has helped move up and out of poverty that are demanding political change, quality public services, and less state intervention.

Rather than political adversaries I would rather see Dilma and Marina in alliance. Together neither would have to pander to neo-liberal economic or a neo-conservative social agenda. The options for more radical reform and greater social justice would be greater, while recognizing environmental constraints. But that is not going to happen, at least not this side of Sunday’s election.

The other day Lula was giving a campaign speech and someone shouted from the audience “I love Marina.” Lula replied. “I love Marina too, but elections are not defined by love, otherwise I would vote for Marisa (his wife).” In case you were wondering, I am (still) with Lula.

September 30, 2014

What are the pros and cons of positive, negative and global (i.e. post North-South) campaigns?

Oxfam’s launching a big global campaign on inequality in October and as always, there are some fascinating internal meta-discussions about the pros  and cons of different kinds of campaigns.

and cons of different kinds of campaigns.

A few years ago, we launched ‘Grow’, an attempt to run a campaign based on positive framing (a positive vision for the future of food, life and planet, with a focus on sharing). Although a positive frame appeals to a much wider public than just activists, it’s hard to turn it into a hard hitting campaign. We ended up running lot of more traditional ‘problem, solution, villain’ campaigns (on land grabs, corporate malpractice etc) inside the Grow umbrella.

That may be right – to get real change, you need to shift the overall narrative, so that, for example, policy makers and publics realize that planetary boundaries are a genuine concern. But you also need to go beyond generalities and offer tangible actions both for individuals (‘what can I do to make a difference’) and for policy makers, not least because there’s nothing like a quick win to reinforce morale and a sense of the possibility of change.

The inequality campaign’s innovative characteristic is that, more than any previous Oxfam campaign, it completely supersedes the traditional North-South split – inequality is just as big an issue in the UK or US as it is in Brazil or Kenya.

On the face of it, you’d think a genuinely universal issue that arouses passions and anger in countries around the world would make a perfect campaign issue. The challenge is to channel the sense of malaise (which our 85 richest plutocrats = 3.5 billion poorest killer fact so graphically captured) into specifics. Arguably, that’s where Occupy and other inequality protest movements have fallen down. We need to be crystal clear on what we want people to do, how it will make a difference, and what success would look like.

Another issue is cash. Our market research (and we do a lot of it) suggests that people in the UK respond to inequality through association – ‘yes, that reflects the world I live in’. Activists get fired up, as do intellectuals– as Pikettymania demonstrates. But what the wider public don’t do is then put their hands in their pockets. OK this is not a fundraising campaign, but raising funds from the public is vital to Oxfam’s work, so if this harms our income, then Houston, we have a problem.

In practice, a lot of our fundraising will focus on Oxfam’s work on the ground – people-to-people empathy will always be key. But you can’t insulate campaign messaging from fundraising – one is bound to affect the other. At the very least, our inequality narrative needs to avoid undermining that sense of helping real people, and preferably put a human face on what can be quite abstract discussions of inequality and injustice. And fundraising mustn’t undermine the positive framing of the campaign – a very tricky balancing act.

In practice, a lot of our fundraising will focus on Oxfam’s work on the ground – people-to-people empathy will always be key. But you can’t insulate campaign messaging from fundraising – one is bound to affect the other. At the very least, our inequality narrative needs to avoid undermining that sense of helping real people, and preferably put a human face on what can be quite abstract discussions of inequality and injustice. And fundraising mustn’t undermine the positive framing of the campaign – a very tricky balancing act.

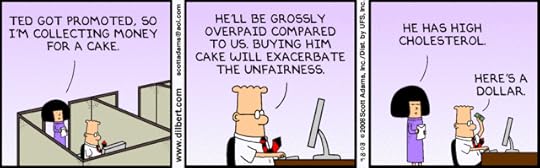

I’ve tried to summarize the different broad categories of campaign below, along with their pros and cons. The usual apologies for creating grotesque caricatures to draw out the contrasts

Type 1: Feed the Hungry (traditional, negative frame campaign)

Positives: Gets to Northern publics and raises shedloads of cash, which enables you to feed more people; can link to some good advocacy work (eg on aid, tax evasion etc)

Negatives: Reinforces stereotypes, offends many people in developing countries, may lead to compassion fatigue

Type 2: Be part of a fabulous future (positive frame campaign)

Positives: Appeals to broader group of people. More accurate portrayal of a world where many social/economic indicators are getting better.

Negatives: Difficult fit with traditional campaign formula of ‘problem, solution, villain’. Can all get a bit Cumbaya. Nightmare for fundraising.

Type 3: We’re all in this [bad place] together (globally shared injustice)

Positives: Immediate association, built on people’s lived experience, moves beyond increasingly outmoded distinctions between North and South

Negatives: Hard to turn a global malaise into a set of plausible specific targets, either for individual choices or policy decisions. Oh, and Northern governments seem very sensitive to criticism, and start accusing you of being political (though perfectly happy if you make similar criticisms of southern governments).

Personally, I’m delighted that Oxfam is taking on a type 3 campaign that genuinely moves us beyond the old North-South divide. It feels radical, progressive and somehow more respectful – that’s the kind of organization I want to work for. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy.

September 29, 2014

Why I love the UN, aka the battle between policy space and trade/investment agreements

Being a fan of the UN is always a bit of a mixed blessing. Various bits (UNDP, UNICEF, UN Women and many more) churn out some really useful research.  For many years, they provided the sole islands of sanity resisting the market fundamentalism of the Washington Consensus. But all too often their publications sink without trace, their use of social media is often lamentable, and they generally struggle to keep up with the times (or their rivals).

For many years, they provided the sole islands of sanity resisting the market fundamentalism of the Washington Consensus. But all too often their publications sink without trace, their use of social media is often lamentable, and they generally struggle to keep up with the times (or their rivals).

So I wasn’t surprised to find I’d missed the 10th September launch of the Trade and Development Report 2014, the annual flagship of the UN Conference on Trade and Development, founded 50 years ago this year, amid all the rhetoric and hopes for a post colonial ‘New International Economic Order’.

Just in case, like me, the TDR passed you by, UNCTAD’s overarching message is ‘the enduring case for policy space’. Sounds dull, but is really important. Here’s why:

‘Since the early 1990s, there has been a wave of bilateral and regional trade agreements (RTAs) and international investment agreements (IIAs), some of which contain provisions that are more stringent than those covered by the multilateral trade regime, or they include additional provisions that go beyond those of the current multilateral trade agreements.

Provisions in RTAs have become ever more comprehensive, and many of them include rules that limit the options available in the design and implementation of comprehensive national development strategies. Even though these agreements remain the product of (often protracted) negotiations and bargaining between sovereign States, there is a growing sense that, due to the larger number of economic and social issues they cover, the discussions often lack the transparency and the coordination − including among all potentially interested government ministries − needed to strike a balanced outcome.

Policy space is not only reduced by free trade agreements, but also when countries sign up to IIAs. When most such agreements were being concluded in the 1990s, any loss of policy space was seen as a small price to pay for an expected increase in FDI [Foreign Direct Investment] inflows. This perception began to change in the early 2000s, as it became apparent that investment rules could obstruct a wide range of public policies, including those aimed at improving the impact of FDI on the economy. Besides, empirical evidence on the effectiveness of bilateral investment treaties and investment chapters in RTAs in stimulating FDI is ambiguous.

Policy space is not only reduced by free trade agreements, but also when countries sign up to IIAs. When most such agreements were being concluded in the 1990s, any loss of policy space was seen as a small price to pay for an expected increase in FDI [Foreign Direct Investment] inflows. This perception began to change in the early 2000s, as it became apparent that investment rules could obstruct a wide range of public policies, including those aimed at improving the impact of FDI on the economy. Besides, empirical evidence on the effectiveness of bilateral investment treaties and investment chapters in RTAs in stimulating FDI is ambiguous.

Moreover, the lack of transparency and coherence characterizing the tribunals established to adjudicate on disputes arising from these agreements, and their perceived pro-investor bias, added to concerns about their effectiveness.

A range of possibilities is currently under consideration to rebalance the system and recover the needed space for development policies. These include: (i) progressive and piecemeal reforms through the creation of new agreements based on investment principles that foster sustainable development; (ii) the creation of a centralized, permanent investment tribunal; and (iii) a retreat from investment treaties and reverting to national law.

Along with the proliferation of trade agreements and their expansion into trade-related areas, there has been a global revival of interest in industrial policy. Reconciling these two trends is a huge challenge. Many developed countries, especially since the recent financial crisis, have begun to explicitly acknowledge the important role that industrial policy can play in maintaining a robust manufacturing sector. The United States, while often portrayed as a country that takes a hands-off approach to industrial policy, has been, and remains, an avid user of such a policy. Its Government has acted as a leading risk taker and market shaper in the development and commercialization of new technologies, adopting a wide range of policies to support a network of domestic manufacturing firms that have the potential for innovation, exports and the creation of well-paid jobs. By contrast, the experience of the EU illustrates how intergovernmental agreements can constrain the policy choices of national policymakers.

As some developing countries have reassessed the merits of industrial policy in recent years, they have also used some of their policy space to induce greater investment and innovation by domestic firms so as to enhance their international competitiveness. Some of the measures adopted include applying preferential import duties; offering tax incentives; providing long-term investment financing through national development banks or subsidizing commercial loans; and using government procurement to support local suppliers. Various policy measures continue to be used in countries at different levels of development − from Viet Nam to Brazil − in an effort to create a virtuous circle between trade and capital accumulation.’

And with that, the report zooms off into the need to strengthen domestic sources of revenue, including from natural resources and sorting out the international tax system (or lack of it).

I worked on WTO and trade issues from 1997-2005, and saw the UN and academics like Dani Rodrik and Ha-Joon Chang slowly gain traction for ideas of ‘policy space’ as a counterweight to the ‘get the prices right’ language of the more extreme liberalizers. Great to see the UN still going strong – just wish they would sort out their comms a bit.

September 28, 2014

Links I liked

My favourite image from the global climate protests around last week’s UN meeting: Australian Campaigners Salute the Government’s Climate Change  Strategy [h/t Jim Harris]

Strategy [h/t Jim Harris]

According to Pope Francis, ‘the corrupt should be tied to a rock and thrown into the sea’. Any chance that could become a new Oxfam policy recommendation?

People had a lot of fun with India’s frugal (and successful) Mars mission, which seems to have become an international benchmark for something or other:

It cost less than the movie Gravity or the first U.S. Stealth Jet Attack [image error] on Syria

World Bank chief economist Kaushik Basu pointed out that since India’s BigMac purchasing power parity-PPP-is 3 and its Mars Mission PPP is 9 (i.e. 9 times cheaper than the US Mars probe), Ricardo would recommend India import burgers & export Mars Missions. Makes sense to me.

Superb summary of UK Middle East policy, left [h/t Stuart Lodge]

Civic Space Initiative: Civil Society Under Threat. The World Bank lists six legal constraints that governments are using to close us down.

I know she’s white, privileged and famous, but Hermione Emma Watson was still brilliant on the need for men to champion gender equality

September 26, 2014

After New York, how should climate change campaigners approach Paris? (aka Naomi Klein vs the New Climate Economy)

Oxfam head of policy for food and climate change Tim Gore reflects on what happens next after the euphoria of New York (and asks you to vote, right)

First, the good news. After the Copenhagen hangover, the international climate change movement is back.

Over recent days in New York, we’ve seen the emergence of a new people’s climate movement, broader than anything that has gone before. Oxfam asked supporters to join us in the world’s biggest #foodfight, marching to stop climate change from making people hungry. It was thrilling to have massed ranks of demonstrators calling for ‘good food for all’ as we surged down 6th Avenue, past Fox News and the offices of Bank of America. Ten years ago climate activists were chanting about oil; in New York progressive movements made the links to food, water, jobs, health, children and culture. Although yes, the polar bear costumes were still there too.

Ban Ki Moon said he felt like the Secretary General of the People. President Obama told his fellow leaders that they couldn’t ignore it if their citizens keep marching. More than 400 000 were on the streets, and it wasn’t to listen to a concert, or even a speech by a celebrity, it was just to walk together. The marchers and their demands weren’t owned or framed by any of the big campaigning organisations, but reflected New York itself in all its glorious diversity. The best speech made in those days was delivered by a mum from the Marshall Islands, whose poetry has given us all a new voice for our struggle.

Kudos to those who got the framing for New York so right. But where do we go next, and critically, how should we frame our next major show of strength on the streets of Paris in just over one year’s time?

In some ways, the UN Climate Summit that provided the back-drop to the People’s Climate March was an easy hit. Expectations were so low, the message of the march was never designed to influence its specific outcome, but to offer an alternative narrative to it. As one of its key organisers has said: “the ‘Climate Summit’ that took place in the streets on Sunday was… Far more powerful than anything that took place inside the UN”.

Do bears get read their rights?

In Paris next year, where governments are due to agree a new international climate deal for the post-2020 world, the positioning will be much more challenging. Some groups will want desperately to see a new deal secured. They may even talk down expectations, arguing that the multilateral system cannot bear another Copenhagen meltdown. Others will insist from the outset that no deal on the table will be strong enough. Some will want to point to the positives – the signals sent to investors and other influentials. Others will insist that no agreement is better than fooling ourselves with a bad one, and declare that the struggle continues.

These different strains of thought were already on display in New York in two books published in the run-up to the city’s big climate events. The New Climate Economy report was billed as the successor to the Stern Review – the new bible for those looking to make the case for climate action in the Ministries of Economics and Finance around the world. And it certainly does a decent job – providing talking points for policy wonks and savvy journalists. The best? Reduced fuel expenditures from renewable energy (which as a source is free) compared to fossil fuels will save around $5 trillion by 2030, more than compensating higher up-front capital expenditures (oh, and health costs of GHG emissions in the most polluting countries are 4-10% of GDP!)

The vision it paints is of a low-carbon world within our grasp, requiring just a few tweaks to our current economic model. Internalise the price of carbon here, shift some subsidies there, and the magic of an otherwise largely neo-liberal market economy will take care of the rest. The We Mean Business coalition came out with their own version a few days later. For some in civil society, they have charted a new path that can convince the bastions of economic power in our world to alter their course just enough to avert climate catastrophe.

As the title of her new book – This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate – suggests, Naomi Klein served up a more wholesale model of change. Here the vision is one which links the climate crisis to soaring and historically unprecedented inequality, driven at its heart by the same failed economic model. She does not set out to convince civil servants in finance ministries, but to spur people to tear down their walls. She was a headline speaker for those who tried to Flood Wall Street the day after the mass protest march.

So how should we approach Paris? Which vision of change will serve us best? Is this the moment to grab what we can – the results of a year’s renewed

The other Tim Gore

campaigning on the back of New York – or to raise the stakes higher? If we walk-out of the Paris COP, as many of us walked-out of Warsaw last year, will we inspire millions of people to more impassioned climate activism around the world, jolting leaders to finally get real about the scale of response this crisis demands? Or will we be dismissed as dreamers, or malcontents who will never be happy, as our new supporters drift away again to focus on their daily lives and struggles. Would the poorest and most vulnerable countries walk with us, or take the deal on the table? What would you do if you were in the position President Nasheed of the Maldives found himself in at Copenhagen, painfully depicted in The Island President?

These are some of the questions that now confront our movement. We must challenge ourselves to answer them together, wherever possible in solidarity not in discord.

One thing that should be different in Paris compared to most other UN climate meetings, is that the big march will be planned for the end – not the mid-way point – of proceedings. This should give civil society the final word, framing the outcome, rather than hoping to influence it – in recognition that whatever comes out of Paris, the struggle against climate change will be far from over. All groups should thus be able to focus on driving greater ambition from the next day. Some will do so having rejected the Paris outcome as the latest example of green-wash. Others will amplify what they can, even as they demand much more must yet be done.

In New York civil society spoke with one very loud and – while disparate – largely united voice. Our challenge now, even as we deepen our particular models of change, is to ensure that the next time we speak we do not allow our differences to undermine our impact. Having spent more than six years stalking the halls of UN climate talks trying to secure tweaks to text, I know one thing: insider advocacy alone cannot deliver us the political agreements we need. Building this movement on the streets and outside the corridors of power is the only way we will win, our strategies must be centred on achieving that.

And to help Tim work through his dilemma, here’s your chance to vote on future climate strategy – see poll, right.

September 25, 2014

Measuring academic impact: discussion with my new colleagues at the LSE (joining in January, but not leaving Oxfam)

From the New Year, the London School of Economics International Development Department has roped me in to doing a few hours a week as a ‘Professor

Potential role model?

in Practice’ (PiP), in an effort to establish better links between its massive cohort of 300 Masters students (no undergrads) and ‘practitioners’ in thinktanks, NGOs etc. So with some newbie trepidation, I headed off this week to meet my new colleagues. Some impressions:

Overall, an academic awayday is not that different from the NGO variety. No-one stays on topic or on time; lots of passionate arguments. But at least they’re quirky, eccentric and pretty funny (sample: ‘here you are, a PiP surrounded by lemons’, c/o David Keen). And dead clever of course.

Interesting range of approaches from quants crunching big datasets to philosophical types musing over the origins of mass delusion.

The introduction of fees has contributed to some pretty fierce competitive pressure and greater levels of accountability to students (good thing too). The results of student surveys are compared with rival universities, with lots of agonizing when you fall short (eg on quality of feedback to students). Research rankings, and of course student applications also get a lot of scrutiny.

Academia is under huge pressure, just like the rest of us, and many of the pressures will be familiar to any aid wonk. Notably endless skirmishing on whether to measure the impact of academics’ work, and if so, how. It is fiercely resisted by some, who argue that by pushing academics into areas where they can demonstrate impact, typically on government policy, it risks turning them into glorified consultants.

But it is welcomed by others and in any case, is probably unstoppable – the UK government allocates 20% of its research funding to universities according to evidence of impact (and that is likely to rise in the next funding round, scheduled for 2020), and the vast majority of other funders make similar demands. My advice, drawing on similar discussions in the aid business, is that rather than simply being a refusenik, it is smarter to engage with the measurement agenda and push it towards measuring what matters, not just what’s easy to measure.

In practice, it is the established academics that find it easiest to demonstrate impact: they have had time to establish networks and reputations. Feeding the impact machine could easily end up being something the old guard takes on (albeit with lots of grumbling), in order to let the young bloods get on with building their careers.

If only it was that easy

Attribution is a headache: academics are forced to chase down ‘testimonials’ from officials saying how useful their research has been (DFID has a policy of refusing to provide such bits of paper), but these are seen as a last resort compared to citations, quotes in speeches and documents by governments or other targets.

To help assess impact, there are several pretty dodgy (and conflicting) metrics being bandied about adding up individual academics’ publications, downloads, citations and even (love this) ‘esteem indicators’. If the various scores are ever taken seriously, they are crying out to be gamed (I’ll cite your paper if you cite mine).

It was all a little redolent of ‘paradigm maintenance’, a term coined by Robert Wade, who was in the room. Robert decried ‘the emphasis on utilitarian knowledge to strengthen existing power structures. Instead of critiquing the status quo, we have to help them do their jobs better!’

This got me thinking about Matt Andrews’ view of institutional reform, which he sees as passing through an initial stage of ‘deinstitutionalization’, in which critics should ‘encourage the growing discussion on the problems of the current model’. That may be a vital contribution of research, but which government official is going to credit your broadsides and ridicule as the reason for a change in policy? The net result could be to tilt the balance towards impact that is ‘chummy, immediate and easily attributable.’

But despite the lengthy arguments on impact, it was stressed that the priorities remain a) students and b) quality research – impact is third (reassuring, I think). And if it encourages people who are ‘naturally bookish’ to get out and spread their knowledge, that has to be a good thing, right?

Overall, there were a lot of similarities with the results/value for money debates in aid land, except that in aid there is no equivalent of ‘pure research’, and here the counterarguments are backed up by scary levels of erudition – Foucault et al. Glad I don’t have to persuade them.

All in all, a reassuring day – looking forward to January.

September 24, 2014

So you’ve written the research report: what else do you need to do to ensure people actually read it?

Remember the old days when you wrote a report, published it (perhaps with some kind of executive summary), did a couple of seminars and then declared victory and moved  on? Social media have changed that game almost beyond recognition: to maximize impact, any new report more closely resembles a set of Russian dolls, with multiple ‘products’ (hate that word) required to hit different audiences and get the message out. I’ve tried to list them, but am bound to have missed some – please fill in the gaps:

on? Social media have changed that game almost beyond recognition: to maximize impact, any new report more closely resembles a set of Russian dolls, with multiple ‘products’ (hate that word) required to hit different audiences and get the message out. I’ve tried to list them, but am bound to have missed some – please fill in the gaps:

The report: 100 pages of well researched, clearly argued, and insightful thinking. Which (apart from other researchers) hardly anyone reads.

The Overview Chapter: 10-15 pages with all the juice from the report

The Executive Summary: A two pager for the time-poor

The landing page: better be good, or people won’t click through

The press release, with killer facts, notes to editors, offers of interviewees, embargo times and all that old media mularkey

The blog post: a way of alerting your particular epistemic community to the existence of your masterpiece

The tweets, although personally I hate those naff ‘suggested tweets’ you get from comms people.

The infographic: if you want to get retweets, these work much better than text. ODI currently the most infographic-tastic of development thinktanks

The 4 minute youtube piece, preferably not looking as knackered as Matt Andrews often does

Please add any layers I’ve missed.

If this seems like a huge amount of work, you can always just rely on word of mouth to get your paper out and about. But even when added together, all the comms packaging surely only amounts to a tiny proportion of the work that goes into the paper itself, so it would seem to me to be worth adding every bell and whistle you can. (On the other hand, has anyone got any evidence for the extent to which the packaging improves take up? Time for an RCT perhaps – randomly select some papers for the full treatment, and see what happens?)

Of course, this is only one small part of ‘research for impact’. What you actually say and how you say it, the topic you choose, the rigour of your research, the governance of the project (eg sneakily involving target individuals/institutions from early on) and timing (best to (re)publish after a scandal, crisis or general meltdown, when decision makers are looking for new ideas) are probably much more important in determining whether anyone takes any notice of all your hard work.

Update: lots of good comments below, thanks also to Robert Watt for linking to a great article on the ‘wonkcomms‘ site, which argues that thinking of research in terms of ‘artifacts’ is the start of the problem. Better questions are a) What outcomes do we want from our research? and b) How can we project our research as a thread for continual engagement? Smart.

September 23, 2014

How Change Happens: Great new case studies + analysis on ‘Politically Smart, Locally Led Development’

The research star of the show at last week’s Thinking and Working Politically event was a great new ODI paper from David Booth and Sue Unsworth. Politically smart, locally led  development seeks to identify the secret sauce behind 7 large and successful aid programmes: a rural livelihoods programme in India; land titling and tax reform in the Philippines; disarmament, demobilization and reintegration in the Eastern Congo; the EU’s global plan of action to reduce illegal logging; civil society advocacy on rice, education and HIV in Burma and inclusive governance in Nepal.

development seeks to identify the secret sauce behind 7 large and successful aid programmes: a rural livelihoods programme in India; land titling and tax reform in the Philippines; disarmament, demobilization and reintegration in the Eastern Congo; the EU’s global plan of action to reduce illegal logging; civil society advocacy on rice, education and HIV in Burma and inclusive governance in Nepal.

The paper identifies a number of common elements:

‘Purposive muddling’: Project teams experimented, hit dead ends, tried something else, meaning that often spending and results built up over time. In the Philippines ‘It took four years to find effective ways forward. [This] involved exploring and abandoning several different avenues, and eventually hitting on a way of sidestepping major opposition by restricting the reform to residential land titling (so avoiding vested interests opposed to changes in agricultural land titling).’ There was a lot of learning from previous failures, which required having experienced staff who knew where the institutional bodies were buried.

Brokering relationships: a hugely time-consuming effort to establish relationships and build trust with partners and institutions. In India, this included hiring recently retired, senior government officials to support design and help build trust and credibility. In Myanmar, ‘the Land Core Group brought together for the first time civil society and government officials in a national dialogue on land tenure and land use rights reform. [Elsewhere] support has facilitated networks involving different ethnic and faith groups to improve HIV prevention and treatment for marginalized groups in remote areas.’

Politically smart: the leaders of the interventions were politically well informed and had the skills to use that knowledge effectively. They acquired their knowledge and skills in a variety of ways (personal experience, commissioned political economy analysis, well-connected intermediaries).

Local leadership: ‘In all cases, the interventions addressed issues with real local salience and the solutions were locally negotiated and delivered because project managers allowed local actors to take the lead. Across the cases there was a common willingness of the ultimate funding body to take a back seat. Donors provided external stimulus and had their own vision of the kind of change they were seeking to support, but they avoided dominating either the agenda (in the sense of specifying what to do) or the process (specifying how to do it). This was critical in freeing the front-line personnel to explore pathways towards changes that were both worthwhile and tractable.’

‘There are two other factors that were important in all the cases. First, flexible funding arrangements supported iterative approaches to design and implementation and allowed people to respond to opportunities as they arose. None of the programmes was under pressure to meet particular spending targets or timetables. Secondly, in all cases funding agencies were prepared to make long-term commitments, and in many cases there was an unusual degree of staff continuity.’

‘There are two other factors that were important in all the cases. First, flexible funding arrangements supported iterative approaches to design and implementation and allowed people to respond to opportunities as they arose. None of the programmes was under pressure to meet particular spending targets or timetables. Secondly, in all cases funding agencies were prepared to make long-term commitments, and in many cases there was an unusual degree of staff continuity.’

What is the ‘so what’ for donors seeking to work more along these lines? If success is down to so many unpredictable factors – finding development entrepreneurs, champions in government, the right issue etc etc, trying to pick winners and then simply applying a new ‘politically smart, locally led’ toolkit is unlikely to work. A better option is creating an broader ‘enabling environment’ where those entrepreneurs who happen to emerge at the right time and place can get stuff done.

Unfortunately, the aid business currently has something closer to a disabling environment: high staff turnover, pressure to deliver short term results and spend a lot of money and risk aversion, along with the imbalance of power between donor staff wielding chequebooks, and ‘partners’ seeking cheques. By contrast, ‘Iterative, adaptive problem-solving requires an underlying relationship of trust between the funder and front line operators: the funding agency must show some willingness to let go.’

In some of the 7 cases, donors achieved this by operating at arm’s length, handing over responsibility to an intermediary organization. In others, aid agency staff had the personal and professional status, self confidence and/or political backing to defy the institutional culture.

The authors wonder ‘what kind of political and bureaucratic environment would have killed off our seven programmes or arrested their development early on? Among the obvious, killer conditions would be:

a requirement at the outset to write a ‘business case’ setting out options and assessing their relative value for money, based on a theory of change

that fails adequately to capture complexity and unpredictability;

that fails adequately to capture complexity and unpredictability;conducting a diagnostic analysis to define the conditionalities attached to a large loan;

setting spending targets rather than allowing funding requirements to emerge;

requiring regular progress reports against predetermined targets;

banning funding to politically connected individuals and organisations;

placing ceilings on the share of administrative costs in project budgets; and

tolerating high staff turnover.’

Which unfortunately looks a lot like the typical aid agency rules and procedures.

What to do? The paper has some helpful tips and tactics, but also discusses broader strategy. The key is for donors to nurture their assets beyond the chequebook, especially political knowledge, connections and skills. Those mean they can put the chequebook aside, and start to build relations built on mutual respect and genuine trust.

‘Donor agencies could do more to make it clear through recruitment and promotion practices that they value in-depth country experience as well as technical knowledge; could keep staff in post longer; encourage them to invest in understanding local context (through formal analysis but also by building broad relationships and networks); give them flexibility to (re)define outputs and outcomes as their knowledge of specific challenges increases; support the development of more systematic learning mechanisms and less prescriptive monitoring practices; and avoid setting unrealistic spending targets or requirements to achieve short-term, pre-defined results.’

Conclusion?

‘The good news is that there is nothing inherently new or esoteric about politically smart, locally led approaches that support iterative problem-solving: they have much in common with good policy-making anywhere. Indeed it is a measure of how detached the aid business has become from everyday reality that we should consider any of the seven cases remarkable. They show that donors can facilitate developmental change in very challenging contexts, but only if they are prepared to align their own thinking and practices with the uncomfortable reality that processes of developmental change are complex, unpredictable, mainly endogenous, and pervaded by politics.’

My only criticism? Why do political scientists insist on coming up with such clunky, instantly forgettable slogans? Politically Smart, Locally Led Development; Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation; Problem-Driven Political Economy Analysis. Not exactly ‘Getting the Prices Right’ are they? As usual, the devil has the all the best tunes. Anyone got a better suggestion?

September 22, 2014

Thinking and Working Politically update: where have aid agencies, consultants etc got to?

Spent an engrossing couple of days last week at a ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ (TWP) seminar, organized by a group of donors, thinktanks and consultants (sorry, Chatham House Rules, so that’s as much as I can say about them). Their common ground is that aid needs to get beyond its technocratic comfort zone, and take politics and power more seriously. It’s a new initiative, and as with all such efforts, is pretty messy and confusing at first, as people try to agree on problems, definitions, language etc before deciding what to do. But this was the third such meeting, and I think we’re getting somewhere.

First a bit more clarity on ‘the spectrum’ of what constitutes TWP (see graphic). At one end is what was termed an ‘evolutionary’ approach – getting more politically savvy in the way donors do their normal aid activities (building stuff, offering technical support, financing public services). It’s a random number, but people typified this as ‘adding 15% to the impact of aid programmes’ by designing them with a fuller understanding of institutions, incentives and interests (both material and political).

At the other end is a more transformative ‘revolutionary’ approach, for example where donors do not claim to know the answer, and either respond flexibly to events and political opportunities, or concentrate on bringing together local players to solve a problem (what Matt Andrews calls Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation, or I call ‘convening and brokering’).

A shout out to readers of this blog whose ‘where the fxxx is gender’ comment stream after the first TWP meeting was credited by various speakers who raised gender and the wider question of ‘are we talking about power, or just formal politics?’ this time around. See? Commenting on blogs can make a difference. Sort of.

We also had a good discussion on what TWP is not. This is partly a response to grizzled old aid types who sniff ‘huh, that’s not new – we’ve been TWP for decades.’ One speaker proposed the following list:

Formal Political Economy Analysis (PEA) without changing approach

Standard donor policy dialogue with government

Country ownership/partnership narrowly defined as government-led

Demand side of governance that solely focuses on “more and louder NGOs”

Working through the same old local partners that speak the donor language

Supporting “reform champions” without deeper understanding of political dynamics

Assumption that no one will lose from reforms

Conditionalities attached to a loan

We got a bit clearer on ‘why change doesn’t happen’ – the sources of inertia within the aid system that mean that even when the country director says

One alternative to TWP

‘yes, this sounds like the world I know’, TWP has minimal impact on the country programme. There is a dispiritingly long list of blockers, including the pressure to spend aid budgets: ‘In Afghanistan, people talk constantly about maintaining the burn rate [spending the budget within the financial year]. We can’t do anything that slows the burn rate – we have to address anything going wrong, while continuing to spend.’

More broadly, the technocratic approach of logframes and roll-outs has created a system of staff, contractors, partners and evaluators, who even though they recognize that the system is often based on false assumptions, are either unable or unwilling to do everything differently. It’s an interesting question whether the best tactic is to try and get them to unlearn decades of the old ways, or merely help those who recognize its flaws subvert the current system in a more politically informed way (which Ros Eyben has documented beautifully) – ‘how to bypass a logframe’ guidance notes?

So if promulgating TWP approaches is uphill work, where are the best prospects? Some smart advice here:

- Areas of the aid business where failure is rife and/or risks are high, so people are willing to try new things (fragile and conflict states, oil revenue management, anti-corruption)

- TWP needs to get out of the ‘governance silo’, and show how the approach is relevant to bigger spending areas of the aid business – infrastructure, natural resource management, service delivery etc. Some high profile non-governance champions would help.

- New or rapidly changing contexts, which have not yet had time to entrench standard approaches and so people are more ready to experiment (eg Myanmar).

- Countries with senior champions within aid agency offices – eg ‘Heads of Mission’, or their equivalent

And a few concerns:

Are we designing TWP for gurus or newbies? Rejecting rigid guidelines in favour of ‘every context is different, just cross the river by feeling the stones’ is fine if you’re a veteran of dozens of previous river crossings. It’s not so encouraging if you’re in your late 20s and you’re panicking in your first aid job. My own attempt to square this circle is that a combination of case studies, sample questions to ask, and mentoring via HQ or peer networks, can provide the support people need, without destroying the ability to be flexible and adapt to context. But you probably need some element of written guidance too.

It’s also still very top down. As Craig Valters recently noted, TWP approaches and their accompanying theories of change tend to be dreamt up by the donors and their consultants, not arrived at through anything like a participatory process involving the actual people concerned. That’s pretty worrying.

There is still a tendency to default to ‘if in doubt, commission more research’, even though people accept that the political economy of aid is probably a much greater barrier to TWP than a lack of research. Probably worth getting some professional lobbyists in to design a TWP advocacy programme that covers windows of opportunity, champions, reform coalitions, tactics etc as a counterweight to all those academics seeking yet more research contracts.

It’s still a bit linear: the donor people there are practical types, with very little time for all that stuff about complexity and systems thinking, even though they are highly relevant to making sense of TWP. That pushes us towards the ‘evolutionary’ end of the spectrum – add a dollop of TWP secret sauce to your standard linear programme and voila!

I need a toolkit for the toolkit

Finally, how to communicate all this? For a start, change the name – TWP is unnecessarily and off-puttingly shrill in my view. Call it ‘what works’ or even (not my favourite), ‘politically smart, locally led development’ – the title of a new ODI paper which I will review tomorrow.

But also, there’s tension on how to frame it – consultants and evangelists want a shiny new product, to which aid staff already overwhelmed by endless restructurings and management processes wail ‘OMG, not another toolkit’! We need a sharper narrative and a lot more case studies on what is actually distinct about a TWP approach if we are going to convince the sceptics. Some horror stories and ridicule of bad aid projects that fail by ignoring power and politics would also help open minds. That sounds fun.

September 21, 2014

Links I liked

Your weekly excuse to delay reading your Monday morning emails, drawn from last week’s @fp2p tweets

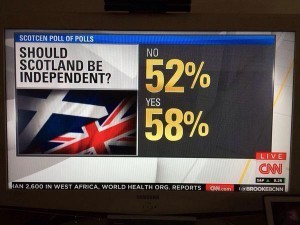

Let’s start with Scotland (obvs)

Nobody can accuse CNN of not giving it 110% [h/t @DanaHoule]

Hilarious and deeply odd. Taiwanese animated explanation of the vote, featuring a strong candidate for the world’s worst Scottish accent [h/t Alex Renton]

Back to Development (broadly defined):

Nice piece on a personal hobbyhorse of mine: Time to take religion and spirituality seriously as a factor in development [h/t Mike Edwards]

ISIS and Ebola outbreaks show we’ve neglected building long term institutions, in our love of funky innovators, disrupters & entrepreneurs

Malaysian news editors apply stylistic rules with great rigor and consistency. [h/t @Durf]

Malaysian news editors apply stylistic rules with great rigor and consistency. [h/t @Durf]

‘Civil space under threat’: Important Economist piece on threats to NGOs/CSOs in many countries

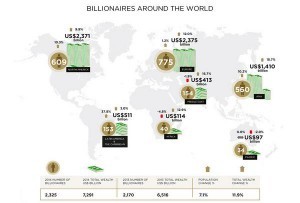

Elsewhere, the inequality/ extreme wealth debate continues to thrive

Number of global billionaires up 7% since last year. Here’s where they live (insofar as live anywhere) – click to expand [h/t Amit M. Sengupta]

Amit M. Sengupta]

The power of killer facts: Christine Lagarde on inequality, using Oxfam’s very own KF: assets of 85 richest = 3.5bn poorest

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers