Duncan Green's Blog, page 175

December 2, 2014

Measuring the difficult stuff (empowerment, resilience) and learning from the results; where has Oxfam got to?

I’m not generally a big fan of measurement fetishism (too crude, too blind to complexity and systems thinking). When I used to (mis)manage the Oxfam research team  and wanted a few thousand quid for some research grant, I had to list numbers of beneficiaries (men and women). As research is a global public good, I always put 3.5bn of each. No-one ever queried it.

and wanted a few thousand quid for some research grant, I had to list numbers of beneficiaries (men and women). As research is a global public good, I always put 3.5bn of each. No-one ever queried it.

But things have improved a bit since then (not least for the research team) and I’m starting to be won over by some very interesting work going on in the bowels of Oxfam House, albeit skillfully camouflaged under a layer of development speak.

For the last 3 years, Oxfam has been running a ‘Global Performance Framework’ (GPF) to try and sharpen up how it measures the impact of its work. This summer, the organisation engaged an external consultant to review the GPF. Our chief measurement guru Claire Hutchings discusses the review and next steps in ‘Balancing Accountability and Learning: A review of of Oxfam GB’s Global Performance Framework’ out now in the Journal of Development Effectiveness (shamefully, it’s gated, but the first 40 visitors can download it for free). Despite the less-than-gripping title, it’s worth a wade (skimming is not really an option), but here’s a sneak preview of some of its findings.

The GPF addressed two challenges facing the organisation: ‘how to access credible, reliable feedback on whether interventions are making a meaningful difference….. and how to ‘sum’ this information up at an organisational level.’

So how do you capture and communicate the effectiveness of 1200+ projects on everything from life’s basics – food, water, health and education – to complex questions around aid, climate change and human rights?

To their credit, Oxfam staff recognized that ‘requiring all programmes to collect data on pre-set global outcome indicators wasn’t the answer, that it had the potential to distort programme design, and would be at odds with the value Oxfam GB places on developing programmes “bottom-up”, based on robust analyses of how change happens in the contexts in which it is working.’

And even if you did try and collect such data, at the end of the day, they would only tell you that change was happening in the contexts in which Oxfam was working. Attributing any given improvement in people’s lives to a particular intervention by Oxfam is incredibly difficult, especially in areas such as empowerment and rights. A principle that informed the design of the GPF was that evaluations needed to understand Oxfam’s contribution (or not) to change.

And even if you did try and collect such data, at the end of the day, they would only tell you that change was happening in the contexts in which Oxfam was working. Attributing any given improvement in people’s lives to a particular intervention by Oxfam is incredibly difficult, especially in areas such as empowerment and rights. A principle that informed the design of the GPF was that evaluations needed to understand Oxfam’s contribution (or not) to change.

So the GPF takes a two-pronged approach: measuring and summing up outputs (the stuff we did) to understand the diversity and scale of the portfolio of work we’re delivering, but also undertaking evaluations of a random sample of closing or mature projects to understand the outcomes (the changes in lives of poor people) of these efforts.

This second string in the GPF bow was designed to add some scary rigour, in the shape of ‘effectiveness reviews’, which use a range of ‘proportionate’ methodologies to measure impact, including quasi-experimental designs for community level development programmes which consider the counter-factual using advanced statistical methods such as propensity score matching and multivariable regression to control for any measured differences between intervention and comparison populations; and a qualitative causal inference method known as process tracing, where there are too few units to permit tests of statistical significance between treatment and a comparison group (so-called ‘small n problems). Phew (wipes brow, wonders if anyone’s still reading).

The GPF also considers the quality of some of our interventions, examining the performance of selected humanitarian responses against 13 quality benchmarks, and assessing the degree to which randomly selected projects meet Oxfam’s accountability standards to partners and communities.

So far, 74 Effectiveness Reviews have been completed, with a commitment to publishing the results, warts and all. They cost between £15-40,000 each, depending on the methodology (and including staff time). That includes the latest batch, the first of which are published today (hence this post). 3 years in, what have we learned?

Working out how to measure ‘Hard to Measure Benefits’ or HTMB (a new addition to the great tradition of development acronyms/jargon) is, well, hard. Kudos to the organisation for not balking at the measurement challenge, or focusing on the easy-to-measure, but we’ve spent a good part of the first three years just working out how to measure the outcomes we’re interested in evaluating, (eg women’s empowerment, resilience), building on the work of others in the sector and learning by doing.

By generating sharper methodologies, Effectiveness Reviews have great potential for improving the rest of our evaluation work – the ones that individual projects/programmes undertake anyway, often to meet donor requirements – but progress has been slow.

Which brings us to the wider point. Riding two horses is difficult, and often painful: there are tensions between (upwards) accountability and learning, with the former  crowding out the latter (to some extent). We get donor brownie points for having both global numbers and rigorous project evaluations, but we don’t make the most of the consequent learning.

crowding out the latter (to some extent). We get donor brownie points for having both global numbers and rigorous project evaluations, but we don’t make the most of the consequent learning.

We’re doing reasonably well at project level, because staff are involved both in the reviews, and in responding to their findings, and there is evidence that they’re making changes to project design and delivery as a result. But at the broader organizational level, with the focus on the measurement challenge and upward accountability, we have not yet digested what this body of evaluations is telling us about Oxfam’s portfolio, or systematically spread the learning across the whole of Oxfam’s work, beyond some limited osmosis via global advisors on particular issues (which by the way is pretty much the same story as a recent review found at DFID). Nor have we fully digested what this body of evaluations is telling us about Oxfam’s portfolio. This will become easier as the number of completed effectiveness reviews grows, allowing more cross comparisons between projects in similar fields, but there is clearly still lots to do.

This was a complex challenge. We needed to start somewhere, and have learned a lot by getting stuck in, adapting the process to better serve a learning agenda along the way. The challenge for the next phase of the GPF is to give more attention to the virtuous links between results and organisational learning – to not only deliver credible results, but to use them to inform our work. In the meantime, the more recent effectiveness reviews are published today, so why not unleash your inner wonk and download a couple?

December 1, 2014

People Power: what do we know about empowered citizens and development?

This is a short piece written for UNDP, which is organizing my Kapuscinski lecture in Malta on Wednesday (4pm GMT, webcast live)

Power is intangible, but crucial; a subtle and pervasive force field connecting individuals, communities and nations in a constant process of negotiation, contestation and

Who’s got the Power?

change. Development is, at its heart, about the redistribution and accumulation of power by citizens.

Much of the standard work on empowerment focuses on institutions and the world of formal power – can people vote, express dissent, organise, find decent jobs, get access to information and justice?

These are all crucial questions, but there is an earlier stage; power ‘within’. The very first step of empowerment takes place in the hearts and minds of the individuals who ask: ‘Do I have rights? Am I a fit person to express a view? Why should anyone listen to me? Am I willing and able to speak up, and what will happen if I do?’

Asking, (and answering) such questions is the first step in exercising citizenship, the process by which men and women engage with each other, and with decision-makers; coming together to seek improvements in their lives. Such engagement can be peaceful (the daily exercise of the social contract between citizen and state), but it may also involve disagreement and conflict, particularly when power must be surrendered by the powerful, to empower those ‘beneath’ them.

Examining European history over the last two centuries, the scholar Sidney Tarrow sees a dynamic of repression, partial victories leading to reform, and demobilisation, repeating itself, leading (despite reverses) to incremental expansions in participation, changes in popular culture, and residual networks of movements.

Citizen mobilization does not, of course, always lead to victory – what determines its chances of success? A meta-synthesis of a sample of 100 case studies in 20 countries identified some common elements:

The importance of democratic space

Diverse, nationally grounded coalitions – not necessarily lead by International NGOs

Alliances – Civil society organisations rarely change policy by themselves

‘Contentiousness politics for contentious issues’

Seems a long time ago, now

The interaction between state and citizen is perhaps the most important relationship in development. Effective, accountable states can empower citizens through everything from promoting norms of inclusion and non-discrimination, ensuring birth registrations and guaranteeing freedom of association, to ensuring states’ own transparency and accountability, and the rule of law. States can also curb the ‘bad power’ of big players in society.

But states are increasingly doing the exact opposite, repressing rather than empowering their citizens. A growing number of governments now treat the concept of civil society as a code word for powerful political subversives, usually assumed to be doing the bidding of the West. Power holders often fear NGOs more than they do opposition parties, seeing the former as nimble, technologically-savvy actors capable of activating sudden outbursts of mass protest.

More than 50 countries in recent years have enacted or seriously considered legislative or other restrictions on the ability of civil society to organize and operate. In part this backlash is testament to the growing power of citizens’ movements. The nightmare scenario for power holders in many countries is waking up one morning to find that thousands of ordinary citizens have gathered in the main square of the capital demanding justice, vowing not to go home until they get it.

Women’s Empowerment

Globally, perhaps one of the most extraordinary stories of the last century has been the empowerment of women. The transformation in terms of access to justice and education, to literacy, sexual and reproductive rights and political representation is striking.

That progress has been driven by a combination of factors: the spread of effective states that are able to turn ‘rights thinking’ into actual practice, and broader normative shifts; new technologies that have freed up women’s time and enabled them to control their own fertility; the vast expansion of primary education – particularly for girls – and improved health facilities.

Politics and power have been central to many, if not all, of these advances. At a global political level, the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of  Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) appears to be one of those pieces of international law that exerts genuine traction at a national level, as it is ratified and codified in domestic legislation.

Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) appears to be one of those pieces of international law that exerts genuine traction at a national level, as it is ratified and codified in domestic legislation.

But what is needed to turn such global progress into better national policies? A massive study of changes to policy on violence against women in 70 countries over four decades (1975 to 2005) came to an unequivocal conclusion:

‘Countries with the strongest feminist movements tend, other things being equal, to have more comprehensive policies on violence against women than those with weaker or non-existent movements. This plays a more important role than left-wing parties, numbers of women legislators, or even national wealth.’

Citizen empowerment may be one of the most exhilarating dramas on the global stage, but what role is there for aid agencies and international NGOs? The first lesson is humility – any role is bound to be limited, and many of the drivers of change have little connection to the official worlds of aid and project funding. Indeed badly designed funding can tarnish reputations, undermine local support and fuel toxic accusations of foreign interference. To manage these kinds of risks, outside organizations need to build deep local understanding (usually requiring much greater empowerment and recognition of local staff).

Using diplomacy to deter governments from closing down civil society space, and supporting the long term building blocks of citizens’ empowerment, such as the women’s movement or trade unions and others, may be more advisable than seeking to trigger the next Revolution.

November 30, 2014

Links I Liked

Tried to stay abreast of the twitter stream while in Australia last week (back in UK now). Here’s some of the best links

Squid ink infused black burger, tomato ice cream and other weird flavour combos from around the world, [h/t Chris Blatmann]

yum yum

The repeated “success, scale, fail” experience of aid magic bullets (playpumps etc) over the last 20 years. Great essay from Michael Hobbes

The Payment by Results debate just got interesting. Excellent CGD response to BOND’s critique of Payment by Results, acknowledging serious problems in implementation

A significant challenge to the anti-GM movement. A meta-analysis of hundreds of impact studies from 1995-2014 finds big benefits in developing countries

Important new paper by Rim Turkmani, Mary Kaldor et al has some rays of hope on Syria: local ceasefires could hold the key to easing humanitarian suffering

And a bunch of stuff following up the recent Doing Development Differently conference at Harvard:

What’s the hardest thing about ‘doing development differently’. Nice 4m compilation of angst-ridden clips from participants (including me)

The organizers have produced a commendably well written and short ‘Doing Development Differently’ manifesto (you can sign up if you agree with it – I have)

Meanwhile, in the sceptics’ corner: Dilbert on not Doing Development Differently [h/t Søren Jarnvig]

Meanwhile, in the sceptics’ corner: Dilbert on not Doing Development Differently [h/t Søren Jarnvig]

And Matt Andrews has got his amazing students churning out audio visuals on the DDD agenda – adds a whole new dimension to making the students do all the work: definitely going to try and introduce this when I start teaching at LSE in January. Check out the PDIA rap (‘lemme hear ya say P D I A’), or this impressive student animation summarizing the nitty gritty of ‘problem driven iterative adaptation’

Finally, this Wednesday I’m off to Malta to give a Kapucinski lecture on citizen mobilization, power and change. Here’s the webcast link if you want to listen in (rant starts at 4pm, GMT)

November 27, 2014

How to win the argument on the private sector; seeing like a liberal, and a lifecycle approach to supporting aid agencies

Had a great day at Oxfam Australia last week, immersed in a series of conversations that were dotted with ‘synaptic moments’, when different bits of thinking come  together in your head and a lightbulb goes on. Three examples:

together in your head and a lightbulb goes on. Three examples:

Whose private sector is it anyway? The drumbeat of private sector rhetoric is deafening in Australia’s aid sector. This seems to worry NGOs, who somehow feel marginalized by the new language. That’s bonkers – about half our long term development programming is directly engaging with the private sector; the trouble is we’ve given it a naff NGO name instead – livelihoods.

When it comes to the key driver of poverty reduction – jobs – the kinds of private sector we work with – small farmers, informal economy, SMEs, are far more important than multinationals, which only generate about 3% of world jobs. So how about renaming our livelihoods work as ‘private sector engagement’? Given how much we spend on livelihoods private sector, I think there’s a fair chance that we can show that we give greater priority to the private sector than the donors who are berating us about it – wouldn’t that be sweet?

Obviously, the big companies that are usually equated with the term ‘private sector’ matter too – but there it’s more about obeying the law, paying taxes, whether they are promoting social cohesion or division; instability or stability etc. For those that are based in the North, there’s an important ‘do no harm’ principle for our foreign investors. And our work on extractives, food companies etc reflects that too.

Do they know they’re the private sector?

I think we could also use private sector language much more to explain how change happens, and in some cases it actually sheds extra light. People largely get what Venture Capitalists do, so if we describe a ‘small bets’ approach of trying lots of different approaches and sifting out what works, then calling it a VC model, as we did in Tanzania, can help explain it as well as prise extra dosh from donors who are also looking to hang some more private sector language on their work.

Thinking about markets can also be really helpful to the way we talk about aid programmes. Markets are designed to produce variation and failure, as well as success. That’s what Joseph Schumpeter captured in his great phrase ‘creative destruction’. To allow that creative destruction to take place unhindered, capitalism has generated all mechanisms such as bankruptcy and insurance.

In contrast, parts of the aid industry appear to seek a zero failure rate – that’s a model much closer to Josef Stalin than Milton Friedman. So when someone bangs on about the need to ‘be more private sector’, one response could be ‘absolutely – that’s why we need to get rid of linear plans, and think about experimentation, failing faster, and getting better at spotting and backing success, even when it’s accidental.’

I’d be interested in you reactions to this rant – it’s a highly symbolic debate that is not going to go away.

Seeing like a liberal: NGOs working in countries with conservative or right-wing liberal governments often fail to ask themselves which parts of their ‘repertoire’ are  compatible with those kinds of values. So we’re surprised (or sceptical) when right wing governments champion women’s rights, or David Cameron criticises Tony Abbott for not being a true conservative on climate change (i.e. wanting to conserve the planet). To this I would add support for defending ‘civil society space’ when, as in many countries, it is being closed down by government.

compatible with those kinds of values. So we’re surprised (or sceptical) when right wing governments champion women’s rights, or David Cameron criticises Tony Abbott for not being a true conservative on climate change (i.e. wanting to conserve the planet). To this I would add support for defending ‘civil society space’ when, as in many countries, it is being closed down by government.

Grey Panthers meet Windows of Opportunity: Imagine my joy when two hobbyhorses met and made passionate love together. Grey Panthers is the idea that the best campaigners may well be retired captains of industry; ‘old men in a hurry’ keen to do something good. So why do we persist in equating campaigns with students and youth? But it gets more interesting when you stand back and consider life paths – it turns out that people that there are some common ‘critical junctures’, when people make big decisions in their lives – typically going to university, having your first child and retiring.

From an NGO point of view, you should try and adapt your asks to those life cycles – when people are time rich, ask them to campaign, when they are time poor, ask for their money. We do that at the first critical point – all those stalls at freshers’ fairs trying to sign up student activists. But do we do anything at the other two? I fear we just see retirees as sources of donations and legacies, rather than people with time and networks to spare.

A more subtle, holistic version would acknowledge that people’s lives follow different courses, and give them options to choose the balance of cash v activism that fits their particular trajectory. Anyone got a decent timeline or graphic on these ideas?

By the time you read this, I’ll be on the plane back from Australia and PNG – great two weeks, and a huge thanks to all at DFAT, Latrobe and Oxfam who set it up. More Aussie reflections next week.

November 26, 2014

Why Positive Deviance could be the answer to working in complex, messy places like Papua New Guinea

Final post on PNG trip, after overview and paean to roads and leadership.

Field trips operate on several different mental levels. Superficially, you are seeing new communities and programmes, and learning about the country. But there is also a

Fathers of the nation? Rugby league is one of the few sources of translocal identity in PNG

constant process of interpretation, where you compare what you are seeing with what you have been reading back home or seen elsewhere, and see what resonates.

In PNG, it was positive deviance. Everything in the country is messy – delivering health or education, politics, public finances and aid, for starters. In such complex systems, it may not be possible to work out what kind of aid programme or other intervention is likely to succeed – any number of unintended consequences and unforeseen problems could sabotage your great plans.

So why not start somewhere else entirely. Accept that whether on health, education, nutrition or governance, there is a wide spectrum of success and failure in what is already happening in PNG. So study that spectrum, identify the most successful 5 or 10% of cases, then go and study them to see if there are lessons there for aid donors.

In a way that’s what we do already, in the shape of all that aid gossip and exchange of ideas and experiences in the bars and restaurants, as well as seminars and meetings. But it’s ad hoc, and could be missing lots of the positive outliers, so why not systematize it a bit?

As usual when I think I’ve had a good idea, it turns out that Chris Roche got there about a decade ago. Chris discusses positive deviance in a 2008 paper on PNG and other Pacific islands (Chris Roche 2008 paper). Chris focussed in particular on Bruce Harris’ call for aid to put much more emphasis on ‘translocalism’ – building links beyond village and clan level, in order to build trust beyond their immediate neighbours, an essential first step in nation-building. He argues that it is particularly useful in identifying and recognizing the importance of the ‘thousand points of light’ of successful local initiatives that are going on all the time, but which either fail to register with donors or get loved to death.

‘Ignoring local ‘success’ – or dismissing it as marginal – and in particular ignoring initiatives that deliberately seek to work across clan and tribal boundaries at a ‘trans-local’ level, has three main effects a) it fails to provide incentives for those initiatives which are actually making a real difference to people’s lives now and could do more, secondly b) it fails to reward precisely the kinds of processes that might help to place the kinds of different demands on the system that are needed, and c) it fails to build an evidence base of what is working and why that might be shared, and in so doing promote more effective practice and to adjust policy so that this is better supported. Is it a coincidence that many of these successes are so often run by women, and ignored by men?’

Chris argues that the aid business struggles with this because ‘There is a tendency to focus on deficits and weaknesses because:

Chris argues that the aid business struggles with this because ‘There is a tendency to focus on deficits and weaknesses because:

development theory and capacity building often focus on ‘gaps’;

incentives to worry about constraints and risks;

there is an engineering approach to ‘fixing’ problems;

strength seen as a fortunate condition that can stand on its own;

donor legitimacy often based on overcoming local weaknesses.

Moreover, in its obsession with ‘going to scale’, the aid business too easily dismisses the small stuff (Chris ends his paper with a great Dalai Lama proverb - “If you think you are too small to make a difference, you have never spent the night in a tent with a mosquito”).

The role of outsiders involves identifying the small spores of development and translocalism, and then acting to create an enabling environment for them to multiply – he likens this to creating the conditions for moulds to reproduce and spread. This could include ‘immersion exchanges’ to take potential mould-spreaders to see some successful experiences on the ground, and really get to understand them by spending a decent amount of time there (something that also might help with the uphill effort of getting people in organizations like Oxfam to try out new stuff in their own work).

I think the positive deviance approach has huge potential – suppose our first action when contemplating any campaign, country or programme was to identify and learn from the successful outliers? It could transform everything about the way we work. If someone wants to set up a Positive Deviance Institute, Chris is keen and I’d probably join, even if it was just to have that on my business card.

In Australia, such ideas are encapsulated in the ‘Strength-based Approach to Development’, which sounds like something I should take a look at.

By the way, it turns out Francis Fukuyama got there first – here’s a brilliant paper on the need to build the nation before you can start thinking about state-building in PNG, based on his 2007 visit (thanks to Laurence Chandy for sending it over).

Update: UNDP today published its Human Development Report on PNG, which focuses on the extractives sector, which in PNG has a history of exploitation, conflict and instability, as well as contributing to the recent growth surge (GDP growth of over 20% is expected for 2015, following the start of production from the massive PNG Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) project). Not sure how well these attempts to cram 100+ page reports into a single picture work, but here’s their monumental Exec Sum infographic.

November 25, 2014

The Importance of Leadership and the Magic of Roads

Yesterday, I described the grim state of PNG politics and administration, but the Aussies decided to send me to an outlier (in both senses) – the remote inland district of

Me and the Member for Nuku

Nuku. Nuku is in the middle of a fascinating mini-transformation, and DFAT is pretty excited about it.

That transformation forced me to question two of my extensive array of NGO prejudices – suspicion of political leaders, and scepticism of the importance of building roads.

First, some essential background. Nuku, with 70,000 people speaking 41 different languages, is one of PNG’s most deprived districts. Sorry to sound like a civil serpent servant, but when you’re on one of these trips, you have to get to grips with the different tiers of administration, because that’s how everyone thinks and talks. In PNG’s case, there are 22 provinces, each of which are subdivided into districts, some 89 in all. Those in turn are divided into further tiers, with the lowest being wards of a thousand or so people, of which Nuku has 84.

Each district is completely dominated by its MP – the introduction of the Westminster system of First Past the Post turbocharged PNG’s traditional Big Man system (there are few Big Women – the gender rights situation in PNG is dire), although the recent addition of an element of proportional representation may have moderated that a bit. Over to the great paper by Bruce Harris (Harris PNG Nation in Waiting 2007):

‘The “big man” becomes such through his own efforts, not through ascription as a member of a chiefly lineage or as a result of a position in a feudal structure. To achieve the position of “big man” requires, above all, the creation of a group of followers, a faction. The larger the faction the more power accrues to the leader. The genuine big man is a compelling figure. He has impressive oratorical skills, the instincts of a shrewd businessman able to manipulate the system of reciprocity and exchange to his own ends, and is, above all, a populist political leader with charismatic qualities who has gained the unquestioned allegiance of a large group of dedicated followers who have nearly unquestioned faith in him.’

And a lot of that describes Joseph Sungi MP (right), known throughout Nuku simply as ‘the Member’. Joe is a Big Man in every sense, his bull neck and large frame encased in a dapper pin striped suit, oozing authority and confidence.

Freshly cut and gravelled all weather road

Joe is a man on a mission, and that mission is roads. Using the discretionary funds at every MP’s disposal, he plans to build all-weather roads to every one of Nuku’s 84 wards by the next election in 2017.

‘When we went home for Christmas we had to walk the last 7km to get to our villages. Our kids don’t want to go back home any more. In my village I said, this is the last time I walk here – next time I’ll be in a car. So I made sure the road was built, to show I am a man of my word. Then the people are convinced.’

On Nuku’s rapidly-proliferating road system, we see plenty of evidence that this obsession is bearing fruit. The district has used its budget to buy 13 shiny yellow pieces of earth moving equipment, hire a civil engineer, and work is under way.

Conversations with everyone from officials to church and women’s groups at ward level show that Joe has tapped a nerve. Everyone is enthusiastic about the roads. Like a giant magnet surrounding by iron filings, Joe’s leadership has helped build a sense of optimism and common purpose. Conversations suggest that roads have almost magical properties: they allow farmers to get their cocoa to market, reduce the costs of resupplying schools and clinics, help retain teachers and nurses (who previously were reluctant to go to such cut-off locations). Of course, they aren’t a panacea – women and church leaders worry about some of the negative influences that are entering with improved links, while women farmers say they can now get their crops to Nuku’s main town, but often can’t find buyers and end up just taking them home again.

Joe’s other priority is even more innovative – taking a large wad of local funding and handing it directly over to the wards, US$10,000 each, to spend as they please. In PNG this is revolutionary – the Big Man is handing over money even to villages that didn’t vote for him. The more traditional spending pattern is on display in the yard of the District Administrator’s office in Nuku, where 4 landcruisers are parked up (see pic), the first instalment of some 20 vehicles that the previous Member allegedly handed out to his cronies, which are all now being confiscated.

Joe’s bio echoes a lot of the research of the Development Leadership Programme: the son of subsistence farmers, well down the clan hierarchy, he was educated at an Australian Catholic mission school, and then a boarding school for the best and brightest kids from around the country, where he developed a sense of public ethics and loyalties beyond the village. He went into local administration as an agricultural extension worker, was galvanized by an ADB scholarship to do a Masters in the Philippines, and rose to be the top civil servant in the province before deciding to go into politics.

His understanding of leadership? ‘The key is you talk to people. I don’t write letters – John (his adviser, from a nearby village) does the writing, I do the talking! Most of

Confiscated vehicles awaiting resale

what I do is informal – I owe it all to informal relationships.’

As PNG’s decentralization plans place even more power and cash in the hands of MPs, helping leaders like Joe flourish at the expense of their more kleptocratic colleagues could become an important element of the aid programme. ‘If Members themselves don’t have desire and ambition, there’s not much we can do – maybe a fifth of MPs think like me on this.’

The first step is to understand how they emerge, and then consider what, if anything, outsiders can do to help.

But I think I should stress that I haven’t completely drunk the koolaid on this. Joe seems to have made a great start, but there are hardly any restraints on his discretion, should he at some point end up breaking bad. Good leaders are no substitute for good institutions, so the broader question is how to turn one into the other.

Tomorrow: is positive deviance the best way to transform aid in PNG?

November 24, 2014

Who/what explains the world’s biggest developmental under-achievement? A visit to Papua New Guinea

So did you miss me? (I know, holes, heads etc) After a week on the road and away from the blog, it’s time to try and make sense of last week’s trip to Papua New Guinea (my first visit). I was there at the invitation of the Development Leadership Program, which is funding my How Change Happens book.

Population of 7 million  people (or anything up to 10 million – no-one trusts the figures), strewn across a country the size of France. A country, but not yet a nation. PNG achieved independence in 1975 by one of those strokes of the decolonizing pen, but 848 languages are listed for the country. Due to a combination of culture and terrain (lots of valleys separated by impassable mountains – think Darwin’s finches), people identify with clan and village, but seldom anything beyond. According to a wonderful 2007 overview by Bruce Harris (Harris PNG Nation in Waiting 2007):

people (or anything up to 10 million – no-one trusts the figures), strewn across a country the size of France. A country, but not yet a nation. PNG achieved independence in 1975 by one of those strokes of the decolonizing pen, but 848 languages are listed for the country. Due to a combination of culture and terrain (lots of valleys separated by impassable mountains – think Darwin’s finches), people identify with clan and village, but seldom anything beyond. According to a wonderful 2007 overview by Bruce Harris (Harris PNG Nation in Waiting 2007):

‘To the extent that we can speak of “tribes” (or ethnic/cultural groups) such tribes generally consist of a series of residential groups related by kinship. Each of these groups is fairly independent and generally amounts to no more than several villages or a village and a group of associated hamlets. The groups do not aggregate into any larger political entity – social interaction, trust and interdependence is intense within each group, but drops off precipitously between groups.’

Harris describes the result as a ‘putative state’ – it’s not ‘fragile’ or ‘failing’, because it hasn’t even been built yet.

For anyone still needing to be convinced that when it comes to development, ‘it’s the politics stupid’, I recommend PNG. De Gaulle once asked of France ‘How can you govern a country which has two hundred and forty-six varieties of cheese?’ Try a thousand languages. In many ways PNG represents the last, toughest test of state building, and it’s not going well. Over a decade of continuous high growth has raised per capita GDP by 150%, yet PNG will not achieve a single one of the MDGs, a distinction it shares only with Zimbabwe and North Korea (the MDGs that is, not the growth). Which in terms of turning growth into development, makes it a strong candidate for the biggest underachiever in the world.

Prior to independence PNG was one of Australia’s few colonies, and the Aussies still plough in US$9m a week in aid, including some signficant governance programmes, including interesting work on civil society and sub-national government.

In his paper, Harris argues that PNG politics has been messed up by the way decolonisation overlaid the Westminster system of First Past the Post politics onto a traditional structure of local ‘Big Men’, creating a cocktail of corruption and political paralysis. MPs in particular dominate the system, with huge and highly discretionary power over how public funds are spent.

In the coastal city of Wewak (North coast, see map), we saw a rather too-perfect example of the waste created by bad politics: a derelict half completed sports stadium, (see pic). A Chinese contractor signed the deal, got it half done by the 2012 elections when it was opened with a vote-winning fanfare. But since then nothing has happened, and the grass is growing over the track.

In the coastal city of Wewak (North coast, see map), we saw a rather too-perfect example of the waste created by bad politics: a derelict half completed sports stadium, (see pic). A Chinese contractor signed the deal, got it half done by the 2012 elections when it was opened with a vote-winning fanfare. But since then nothing has happened, and the grass is growing over the track.

Development is paralysed by incompetent or corrupt administration (‘wrong priorities’ is the local euphemism of choice), while litigation over land disputes throws sand in the wheels – the Prime Minister is currently the subject of 22 separate legal proceedings concerning his office. Chuck in a big process of decentralization handing even more power to MPs (more on that tomorrow) and huge natural resource reserves of gold, gas, copper etc, and you have a recipe for political disaster, which is pretty much what PNG is.

What to do? How can outsiders like the Australian Government or Oxfam, which has a large PNG programme encourage the birth of this last, most difficult nation? Harris argues that there is no alternative to encouraging ‘translocalism’, a shift in people’s identity from identification only with clan and village, to higher tiers of government and eventually, the nation.

So in our numerous conversations with villagers, local officials, all the way up to local MP Joseph Sungi (more on him tomorrow), I asked where the drivers of translocalism might come from. The answers were intriguing:

Firstly, it is already happening to some extent – road building and the mobile phone masts that dot the forests are eroding the isolation of the villages. Migration (largely internal – not much of a PNG Diaspora compared to other Pacific islands) and intermarriage is increasing.

Otherwise, anyone seeking to promote translocalism is going to have to think laterally. Sport seems to be one of the strongest unifiers, in particular Rugby League – a passion imported from Australia. Papua New Guineans are devout church goers to a range of denominations – lots of possibilities of faith coalitions promoting national identity, not least as churches continue to deliver much of the health and education. Scholarships to study abroad seem to have a big impact in forging local identity. In the words of one village woman ‘When I’m in your country, I say I’m from PNG. When I’m here, I’m from my village’.

Another point of light is the women’s movement, which seems to be able to bridge divides in a way reminiscent of Northern Ireland during the troubles. More on how to work with these little islands of translocalism in another blog.

I wanted to end on a positive note, because despite the politics, PNG is an amazing place – spectacular vistas of

Chance encounter with a hunter who appeared to help when we got a flat tyre

forests, extraordinarily rich cultures, welcoming people etc etc. On the social side, despite predictions of catastrophe, the country has contained HIV. One thing I really loved is the mongrel language that unites the 800 odd language groups – pidgin. Check out some choice words, which are phonetically written, so pronounce them to see where they come from:

Meri – woman (from the Virgin Mary of the Catholic missionaries, shouts of ‘white meri!’ regularly greeted Oxfam country director Louise Ewington)

Rausim – take it away (from the German)

A fantastic series of references to the belly, Bel hard (angry); bel kol (it’s all cool); bel hevi (sad); bel isi (happy) and Wan Bel (we all agree – we are all of one belly)

And some definite signs of Aussie influence, in the tradition of Sir Les Patterson: Ars nuting (naked) and bugarup (broken).

Tomorrow, the importance of leadership and roads, and a field trip to the middle of nowhere.

And if you want more on PNG, everyone raves about Jo Chandler’s writing for The Age.

November 23, 2014

Using aid to strengthen Parliaments: fix the car, or worry about the driver?

You’d think that all the aid money trying to install functioning democracies around the world would target parliaments and political parties. In fact, they are more often an  afterthought. Alina Rocha Menocal (Developmental Leadership Program, University of Birmingham) looks at the evidence and explains the neglect.

afterthought. Alina Rocha Menocal (Developmental Leadership Program, University of Birmingham) looks at the evidence and explains the neglect.

People all over the world have a very low opinion of parliaments and parliamentarians. Indeed, surveys suggest that, along with political parties, parliaments are the government institutions that citizens trust the least (while the army and the police are the most trusted). This is true across different countries, irrespective of income levels.

Yet parliaments and political parties are two of the most crucial institutions of democratic representation and accountability. However flawed, they are here to stay, and it is difficult to imagine how democracy could exist without them. This is why the question of how parliaments can become more effective is as pressing as ever for those interested in strengthening democratic governance.

Parliaments (alongside the political parties that populate them) have always been treated as the poor cousins of democracy assistance efforts in international development. The lion’s share of resources goes to elections, decentralisation, and civil society. And the stakes have become even higher as the demand for measurable results and cost efficiency grows in donor countries.

The International Development Select Committee, which is part of the UK’s parliamentary Commons Select Committee system, wants to understand why efforts to strengthen parliaments have so far been relatively ineffective, and what, if anything, can be done differently.

Parliamentary debate in Taiwan

This is exactly what my ODI colleague Tam O’Neil and I explored in a study for Sida. So last week, I appeared before the committee. One of the most striking messages from our Sida study is that, while parliamentary development assistance (PDA) remains under-evaluated, a clear and remarkably consistent body of lessons and recommendations has emerged over the past 20 years.

These lessons, which will likely sound familiar to anyone involved in aid and development, include the need to remain engaged with PDA efforts over the long term; ensuring they are driven from within rather than imposed from the outside; encouraging South-South learning; and integrating parliamentary support into other areas of democracy assistance.

Perhaps the single most important lesson (surprise surprise…) is that parliaments are deeply political institutions, and they don’t function in the idealised ways that donors often imagine. Formal rules and individual and organisational capacity constraints are important, but they are not the only, or even the most significant, determinants of parliamentary effectiveness. The political context that parliaments and parliamentarians operate in, and the kinds of incentives they face, are an integral part of the puzzle.

Or to put it figuratively, this means that parliamentary strengthening should not only worry about fixing the car (i.e. formal rules and capacity), but also about engaging with the driver and his/her incentives, while having a sound understanding of the condition of the roads. In other words, the state of the car matters, but the drivers and the interactions between them as they encounter each other on the road heading in different directions is perhaps more important.

Some progress has been made over the past decade to absorb and act on these different lessons. A strategic consensus has emerged at the conceptual and policy levels about the key features of more effective parliamentary programmes. For instance, more donors now use political economy analysis to better understand context and implications for programming. Individual agencies, such as the European Commission (EU) and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), have also taken steps to improve their programme management and evaluation, including efforts to develop more appropriate process and performance indicators to assess the impact of PDA. Various stakeholders are making more consistent efforts to share knowledge and experience. However, at the operational level progress is uneven and limited, and innovations have remained at the margin.

Why has uptake proven so challenging?

One obstacle, certainly, is that there are genuine gaps in our knowledge, and we need a better evidence base for what works, what doesn’t work, and why. This will take  more substantive, focused and targeted evaluations, and more in-depth and comparative research. There must be more systematic sharing of findings about both successes and, perhaps even more importantly, failures.

more substantive, focused and targeted evaluations, and more in-depth and comparative research. There must be more systematic sharing of findings about both successes and, perhaps even more importantly, failures.

But perhaps the most important obstacle to progress on PDA is the political economy of the aid system and the negative incentives within the aid architecture.

For instance, as a number of observers have argued, the desire (imperative?) to demonstrate quick, measurable results in the life of a single project can distort its effects and outcomes, especially when the aim is to influence complex social and political processes. It can encourage a focus on easily quantifiable targets (for instance, the number of training sessions held) rather than more substantive ones (whether the training made any difference and why/why not). The negative incentives that staff in donor and implementing agencies face affects their ability to work in a flexible and adaptable manner and to remain open minded about risk and failure. The short-termism embedded in staff incentives makes it much more difficult to develop in-depth local knowledge and nurture the relationships that would help development actors act as trusted brokers of change, rather than simply as purveyors of funds.

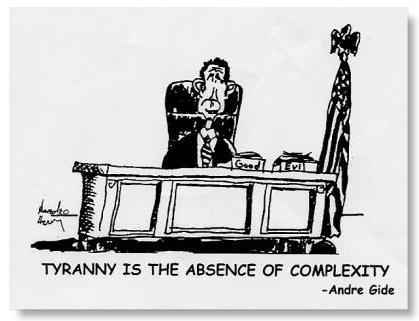

Aid allocated in a series of short-term projects (or “the tyranny of the project”) exacerbates all these problems, while core or stable, longer-term funding provides much needed visibility to experiment and learn. As a savvy practitioner has put it, the upshot of all this is that bureaucratic compliance and accountability wins out over learning, and staff are pushed “to focus on doing things right rather than the right things”. This is not necessarily compatible with working in a more politically aware manner.

The political economy of donors and their ways of working are a foundational constraint to the effectiveness of PDA. Parliamentary strengthening efforts will continue to fall short unless internal incentives and relationships within donor organisations are confronted head on. That is absolutely essential if donors are to get better not only at thinking politically, but also at working accordingly – focusing on fixing the car (i.e. the formal rules), but, much more fundamentally, engaging with the driver and the driver’s incentives. This is messy and difficult and will require a radical shift in the way donors currently work – but it may well prove worth the risk.

The political economy of donors and their ways of working are a foundational constraint to the effectiveness of PDA. Parliamentary strengthening efforts will continue to fall short unless internal incentives and relationships within donor organisations are confronted head on. That is absolutely essential if donors are to get better not only at thinking politically, but also at working accordingly – focusing on fixing the car (i.e. the formal rules), but, much more fundamentally, engaging with the driver and the driver’s incentives. This is messy and difficult and will require a radical shift in the way donors currently work – but it may well prove worth the risk.

November 16, 2014

Links I liked

OK, as you read this, I am wandering around Papua New Guinea, so there may be some interruptions to the blog over the next week or two. Sorry

about that. In the meantime, here’s some time suck material from last week’s @fp2p tweets.

If you’re queasy early in the morning, look away now. This Double Donut Burger contains 98% of your recommended daily calories. I’ll leave further analysis to doughnut economics guru Kate Raworth.

Spoilsport. Alex Evans pours buckets of cold water on the China-US climate deal (and that’s even before the Republicans wade in)

Julia Buxton on the Great Disconnect Between (illegal) Drugs and Development

The reason we are so inefficient, in one bar chart

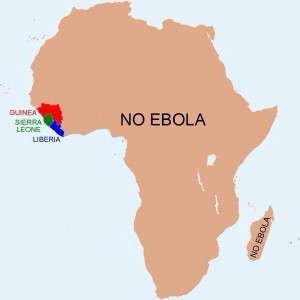

OK, let’s talk Band Aid. Lots of huffing and puffing in the twittersphere over Bob Geldof’s announcement that he’s reconvening the popsters to raise money for the Ebola response with a new version of Do They Know It’s Christmas‘. But is it really such a bad idea? Tom Murphy thinks so, as does the Guardian’s Bim Adewunmi. And they certainly need to be more careful to avoid equating ‘Africa’ with ‘Ebola’ than the T Shirt on the left – maybe they should use the map on the right instead. But I thought I’d ask you,

the readers – Band Aid 30 – good idea or bad? Vote over there to the right.

the readers – Band Aid 30 – good idea or bad? Vote over there to the right.

In any case, (even if on musical grounds alone) Bob might want to just hand over to this fantastic band of West African musicians, with a brilliant song about Ebola aimed at their compatriots.

November 13, 2014

Politics, economists and the dangers of pragmatism: reflections on DFID’s governance and conflict conference

DFID really is an extraordinary institution. I spent Monday and Tuesday at the annual get together one of its tribes professional cadres – about 200

DFID really is an extraordinary institution. I spent Monday and Tuesday at the annual get together one of its tribes professional cadres – about 200

advisers on governance and conflict. They were bombarded with powerpoints from outside speakers (including me), but still found time for plenty of ‘social loafing’, aka networking with their mates. Some impressions:

They are hugely bright and committed, wrestling to get stuff done in some of the most difficult places on the planet, familiar with all the dilemmas of ‘doing aid’ in complex environments that I talk about endlessly on this blog. A visitor muttered about the quality and nuance of discussion compared to the uncritical can-do hubris of much of what they hear in Washington.

In fact, since the Australians and Canadians wound up their development departments, DFID looks pretty well unique in the international scene – heroic keeper of the flame or aid’s Lonesome George heading for species extinction? We’ll find out over the next few years.

What’s interesting is the degree to which DFID’s dominant tribe – the economists – have now ‘got’ the politics and governance discussion. ‘Don’t just do politics at night over beer and pizza’ urged Chief Economist Stefan Dercon. ‘Do it in the daytime – you are the cadre of the long run’. ‘Economists are coming your way – after decades and decades, we’ve decided it’s all really politics’ said Harvard’s Lant Pritchett.

The exchange between econs and poliscis showed a fine sense of mutual parody (Lant: ‘Let me just show some graphs that won’t make any sense to you, because that’s what economists do’; David Harland: ‘I’m sure much regression has been regressed’) but had important underlying areas of consensus: whatever the MDGs say, poor countries can’t ‘leapfrog to Sweden’ – institutional change is slow, cumulative, incremental; rules that stick emerge from actual practice and struggle in a given context, not out of some best practice guideline – echoes of Hernando de Soto’s brilliant history of property rights in ‘The Mystery of Capital’, and a big challenge to universalism.

Great that the economists get it, but it is, needless to say, also a mixed blessing. Stefan is impatient with all that talk of complexity, which he sees as a

Good luck with your diagnostics

recipe for paralysis and navel gazing – ‘are you just the problem cadre?’ he asked. I think that shows he doesn’t fully grasp the implications of systems thinking for how we should work differently. His deputy, Nick Lea set out DFID’s current approach, which it calls ‘Inclusive Growth Diagnostics’. Every country team is to try and answer 5 questions:

What accounts for the pattern and recent history of growth (why we are where we are)?

What are the opportunities for inclusive growth (what would success look like in next 5 years?)

What are the factors that constrain inclusive growth?

What political and institutional factors enable those constraints to persist?

What can DFID do to unlock them?

There’s much to celebrate in that approach (Lant, who always gives top sound bite: ‘most of what is happening on development economics is just stupid. This is smart’) – the acknowledgement that history matters, the lack of a single blueprint for generating growth. But it is still far too linear and ignores some essential aspects of systems thinking – you can’t identify all the factors in advance, you have to make it up as you go along, the importance of shocks as critical junctures etc.

But the arrival of the economists also strengthens an aspect of the governance and institutions debate which worried me in Harvard a couple of weeks ago – when does empiricism and pragmatism cross the line to the amoral, abandoning any sense of rights or norms, beyond the basic commitment to rising income levels? When does an approach to politics become an instrumental effort to boost growth and incomes, rather than the broader set of rights of citizens?

This is reflected in the poster children of this approach – Rwanda and Ethiopia. Stefan Dercon warned against the ‘Latinamericanisation’ of Africa (he wants it to go the East Asian route), but as a Latin Americanist myself, I think there is a lot to be learned from the region, not least on social inclusion, fighting inequality and supporting the care economy.

I talked to Tony Burdon, an exfamer who now runs DFID’s Growth and Resilience team – why are NGOs not doing more on job creation, he asked? You’re completely hung up on decent work, but what people need is jobs, we can worry about upgrading quality later. He has a point – I think NGOs are pretty rubbish on the central role of jobs in poverty reduction. But it sticks in the throat to abandon any commitment to rights – surely we can do a better job in arguing for both?

A Kenyan DFID staffer struck a chord with me when he worried that the elite political settlements that donors promote in search of growth and stability could actually be less inclusive than those desired by both citizens and other actors – when does ‘pragmatism‘ actually end up blocking progressive change?

So I left, mired in confusion – sure sign of a good conference.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers