Duncan Green's Blog, page 178

October 15, 2014

Is doing something about inequality a choice between bash the rich v tackling poverty? Some thoughts for Blog Action Day

Today is Blog Action Day, and we’re all supposed to blog about inequality. Ricardo Fuentes (Oxfam Head of Research) & his team are even marking the day by kicking off a  new inequality-themed blog, Mind the Gap – check it out.

new inequality-themed blog, Mind the Gap – check it out.

I’ve already done my more general call to arms for BAD, so here’s something more in keeping with this blog’s usual tone of navel-gazing uncertainty: I’m a bit baffled by the stuff I’ve been reading recently on inequality and the post-2015/Sustainable Development Goals, and in particular what issues to focus on if you are ‘tackling inequality’. Allow me to spread my confusion (and ask you to vote, right).

Claire Melamed of ODI has a piece discussing inequality and the post-2015 agenda, called ‘The other half: To end inequality, we must realise that it isn’t about the rich, it’s about the poor. And we know almost nothing about them’. She asks:

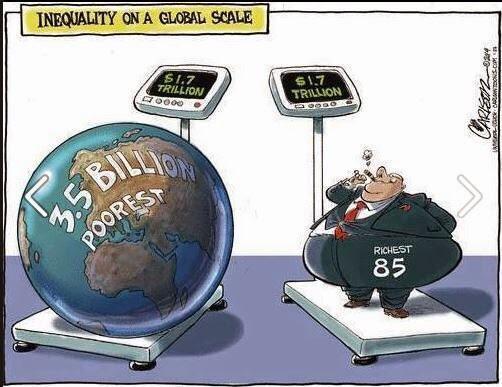

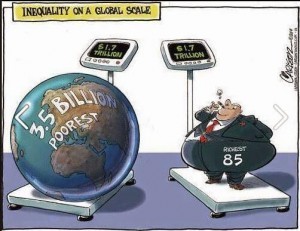

‘What does it matter to an impoverished farmer in South Sudan if 85 people hold as much wealth as half the world’s population? If those 85 people gave everything away, would that actually help the farmer? The problem, I have come to think, is that there are two very different ways of thinking about inequality. The first is all about the rich. The second is all about the poor. The first is the one we usually hear about. The second is the one that really matters.’

Claire reckons that all the focus on the rich is a distraction, generating lots of outrage but ‘a dearth of actual policy ideas’.

She recognizes that more redistributive taxation is one such idea, but argues:

‘If governments make very rich people a bit poorer by changing tax or inheritance rules, who’s to say the money won’t just be spent on missiles or grandiose infrastructure projects or other things that people don’t really want, and which certainly won’t help to tackle extreme poverty? ‘

Instead, she argues ‘we need to look, not at the top of the wealth distribution, but at the bottom; not at the inequalities that make people rich, but the ones that keep people poor.’

Her big idea is that the position of poor people ‘depends to a remarkable degree on the groups that they belong to. Where do they live? What is their ethnic group or religion? Do they have a mental illness or a physical disability? What family do they come from?’

So the kind of inequality we should be addressing is group-based inequality, which basically comes down to affirmative action and supporting the empowerment of marginalized groups.

At which point, I headslapped and said ‘hold on – that’s the Chronic Poverty agenda, which another bit of ODI has been working on for a decade.’ Not sure her colleagues will be best pleased to hear that ‘we know almost nothing about them’.

Then I took a look at Save the Children’s new report ‘Leaving No One Behind’, which argues for ‘Embedding equity in the post-2015 framework through stepping stone targets’. But in turns out that ‘Stepping stones’ are just a catchy phrase for interim benchmarks for the disadvantaged groups – we’re back to chronic poverty again.

So is that it – does all this fuss about inequality just boil down to forgetting about the excessively rich and powerful, and getting back to addressing chronic poverty through a combination of targeting, anti-discrimination and group empowerment? That view seems to fit pretty much with the World Bank’s ‘shared prosperity’ agenda, which neatly sidesteps inequality to focus on ‘fostering income growth of the bottom 40 percent of the population in every country’.

That seems like a bit of a cop-out to me – surely we should do both? Recovering and strengthening the sense of social responsibility of the powerful is important, as is attacking the chronic poverty of the people at the bottom of the heap – why can’t they be mutually reinforcing? At the top, the effort includes more and fairer redistribution through taxation, but also thinking about ‘predistribution’ – some economic models pile up inequality by, for example, favouring capital intensive sectors, whereas others generate more benefits to the poor by creating jobs or involving small farmers in value chains. Then there’s the need for constraints on elite power and political capture – when was the last time a development organization talked about the rules governing lobbying or financing political campaigns, North or South? Put them all together and the overall task becomes something like supporting the strengthening of the social contract between (all) citizens and the state.

Don’t get me wrong, I think the chronic poverty agenda is really important (that’s why I’m on the advisory board of the Chronic Poverty Action Network). But I felt their most recent

Erm, probably not

Chronic Poverty report lost the plot a bit on the SDGs: instead of arguing that chronic poverty is what is left when all the relatively easily reducable poverty has been tackled, and should thus be at the core of ‘getting to zero’ in the post 2015 process, the report went off at a tangent about what to do about people who are not chronically poor, but ‘churn’ in and out of poverty over the course of a year. That’s interesting and important, but people who churn are by definition, not the chronic (i.e. permanent) poor.

So within ODI, Claire Melamed (who runs the team on growth, poverty and inequality, but mainly does post 2015 stuff) is advocating putting chronic poverty at the heart of the SDGs, while the actual chronic poverty people are talking about something else. And anyway, I disagree with both of them, because we should be addressing both the top and bottom of the inequality equation. Feels like time for a poll (if only to put Tim Gore out of his misery for getting the ‘wrong’ answer on the last one).

October 14, 2014

Is the era of flagship publications (HDR, WDR) coming to an end?

Had an interesting chat with some UNDP types last week in the Brixton cafe that is fast becoming my second office. In the same week as UNDP was named top donor on transparency (ahead of the UK and US), they were evaluating the UNDP’s flagship publication, the Human Development Report (HDR). Over the long term, I am a huge fan of the HDR, which is now approaching its 25th birthday. But some of the recent ones have been a bit disappointing (see these  lukewarm/critical HDR reviews from 2009, 2013 and 2014).

lukewarm/critical HDR reviews from 2009, 2013 and 2014).

Rather than moaning about any particular report, we rapidly got onto a bigger question – is the era of big annual flagships ending?

When I started shifting from writing on Latin America to wider development issues, in the late 90s, the flagships were a big deal – especially the HDR and its World Bank equivalent, the World Development Report. In those darker days the HDR (though seldom the WDR), provided much needed alternative views to the koolaid of market fundamentalism.

Now they seem a bit tired, clunky, ponderous – like old-school encyclopaedias overtaken (and swamped) by the instant social media churn of data and information. That means they no longer serve as a useful repository of information – the data is all out there long before the editors and printers have done their work.

This highlights an area of confusion – who is their intended audience? Researchers want instant raw data, while decision makers don’t read 300 page tomes (even I usually only read the overview, and then summarize it for my even more time-famished colleagues). The World Bank has it easier, in that they generate new data (unlike the HDR) and the WDR is also an important agenda setter within the World Bank, which has a much bigger footprint than the report itself. In the UNDP, if anything, the HDR is bigger than the organization, so internal influencing hardly justifies the effort.

So what, in such a world, is the role for a global flagship? There seem to be a couple of candidates:

Agenda Setting: Even if few people read all of it, a flagship can make a big splash around a new or at least breaking issue, provided it is willing to take risks (after all, the main feature of a breaking issue is that we don’t have all the information yet). A well researched flagship can give comfort to activists that the evidence is on their side, strengthening their confidence and credibility. The 2007/8 HDR on Climate Change, which the evaluators have found to be one of its most influential, shows what can be achieved.

Next Generation: Maybe my experience is typical, and people who are starting out in development are looking for an overall steer (though they’re just as likely to get this from a book than an annual report).

Regional Races to the Top: According to the evaluators, one of the main impacts of HDRs is usually to provoke a tetchy political row with governments, who immediately look at where they are on whichever index it produces, relative to their neighbours (think India v Pakistan). This can be difficult for those in charge, and places a premium on confident leadership, but at least it suggests impact – why not make regional league tables a more prominent feature of the work? In fact, maybe the shift should be from global flagships to more targeted regional and national HDRs, with a clearer audience and advocacy strategy.

Regional Races to the Top: According to the evaluators, one of the main impacts of HDRs is usually to provoke a tetchy political row with governments, who immediately look at where they are on whichever index it produces, relative to their neighbours (think India v Pakistan). This can be difficult for those in charge, and places a premium on confident leadership, but at least it suggests impact – why not make regional league tables a more prominent feature of the work? In fact, maybe the shift should be from global flagships to more targeted regional and national HDRs, with a clearer audience and advocacy strategy.

A related point – although the HDR (unlike the WDR) doesn’t require actual sign off from the government reps on the UNDP board, it can suffer from fear of antagonising them. That can lead to bland reports that disappear without trace. Maybe an alliance with other, potentially less intimidatable, research outfits (universities? Thinktanks? NGOs?) would help ensure more of an edge, and might sharpen up the communications side (UNDP is still struggling on the social media side, especially blogging).

But overall, I suspect that a several hundred page flagship is a pretty inefficient and time consuming way to generate the desired impact with the target audience (even if the UNDP is clear on who they are). Time to go back to the drawing board?

Oh, and feel free to give the evaluators a hand and add your opinions below on the HDR and how it could be improved.

October 13, 2014

Why do countries need aid when the world is awash with capital? Latest thoughts from the OECD

I chaired the London launch of the OECD’s annual aid report last week (when it comes to flagships, the multilateral system is starting to look like the Spanish Armada –  more on that tomorrow). We opted for a radical new model for such meetings: the chair keeps people to time, says where the toilets are (when he remembers) but otherwise shuts up. Panelists speak to time, and discuss the report, rather than random other research interests. And the audience asks questions or makes short points, rather than speeches disguised as questions. Novel, eh?

more on that tomorrow). We opted for a radical new model for such meetings: the chair keeps people to time, says where the toilets are (when he remembers) but otherwise shuts up. Panelists speak to time, and discuss the report, rather than random other research interests. And the audience asks questions or makes short points, rather than speeches disguised as questions. Novel, eh?

The Development Cooperation Report 2014 is the second in a trilogy (2013-15) focusing on “Global Development Co-operation Post-2015: Managing Interdependence”. The first was on ‘Ending Poverty’; this one is on mobilising resources, and the final one will cover implementation, reporting and accountability of whatever is agreed in the post-2015 process.

The speakers ranged widely, touching on everything from benevolent dictators to planetary boundaries to just about everything else – maybe my model of chairing needs work. The only thing that enabled me to keep my mouth shut was the knowledge that I could ramble on unhindered on the blog. So here are some impression of the report and the meeting.

The big message from the main speaker, Erik Solheim, was that things are getting better (South Korea’s GDP per capita has risen 390 times – that’s 39,000% – since 1953) and that money is not the problem – there’s loads of it, sloshing around in the international system and domestically ($80 trillion under management by institutional investors, for starters).

In terms of international flows, last year’s record $135bn in aid was just 28% of all official and private flows from the 29 member countries of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (which Erik chairs). There is a growing diversity of options for poor countries seeking cash – market finance, foreign direct investment, private grants from philanthropists and NGOs. And that doesn’t include remittances (3 times the volume of global aid).

But actually, they don’t need any of that if they sort out their tax systems. Tax collected in Africa in 2012 was already 10 times the total aid entering the continent, and among developing countries as a whole, a 1% increase in the tax rate would generate an extra $300bn a year. Alas, in low income countries tax collection as a % of GDP has been stagnant for several decades (according to the speakers) and the donors are doing very little about it – the amount of aid that goes to help poor countries sort out their tax systems is stuck at around a tenth of 1%.

The message on aid gets some careful handling, because the last thing the DAC wants to do is give the impression that aid is no longer necessary. The report identifies three broad purposes for aid:

Safety Net: funds and backing for the fragile and least developed countries, which find it hard to attract or raise other resources

Leverage: use aid to make investment attractive in high-risk situations by spreading and sharing risk, and by creating incentives

Technical assistance: help countries raise and manage their own domestic resources and support the creation of a positive development and investment environment through policy reform in areas such as investment and trade, as well as help new donors like Turkey sort out their aid machinery.

The meeting generated some powerful calls for measuring the amount of aid that arrives in poor countries, or is spent in poor communities, rather than the amount spent by northern governments (not the same thing at all).

The meeting generated some powerful calls for measuring the amount of aid that arrives in poor countries, or is spent in poor communities, rather than the amount spent by northern governments (not the same thing at all).

To which I would add a longstanding hobbyhorse – can someone please support a review of donor performance by their supposed ‘partners’ – developing country governments, civil society organizations and other relevant bodies? I would love to see headlines like ‘DFID/USAID/World Bank fell 2 places this year, because African governments were fed up with the lectures/delays/bureaucracy’.

Instead, all the league tables seem to be drawn up by international bodies, whether official or NGO – accountability seems to have an inexorable tendency to point upwards to where the money/power is.

And if I had been less self-controlled, my two minute rant from the chair would have been this. It’s all very well to make the technical argument that aid is so last decade, and targets like 0.7% are a distraction, or that we need multiple definitions to capture the wider flows of finance for development (new definitions seem to be getting a lot of airtime at the OECD). But can we please think through the politics of how those discussions are likely to go? On definitions, cash-strapped governments are likely to argue for dilution so they can shove loads of other expenditure into the aid budget. 0.7 may not have a rigorous analytical basis, but it is something the politicians and public understand – symbols (the non mathematical variety) matter in public debates, even if technocrats find them annoying.

These wonky conversations will all come to a head at the July 2015 Finance for Development conference in Addis Ababa.

Erik ended the meeting with a striking call to arms – against his country’s own pension fund. Why does the world pat Norway on the head for its aid budget of 1% of GNI ($5.2bn), when its $900bn oil fund, the largest in the world, which has only the most minimal social or developmental criteria for its investments? Nice campaign.

And here’s the 3m report summary

October 12, 2014

Links I liked

Monday morning displacement activity, c/o highlights from last week’s @fp2p twitter feed

Interesting comparison between interracial and same sex marriage in the US. The law moved ahead of public opinion (by decades) on interracial marriage, whereas it  lags on same sex (but is catching up fast).

lags on same sex (but is catching up fast).

Smart satire from the Karl reMarks blog: Global South Launches ‘Best White Saviour’ Award [h/t Tom Murphy]

But you can’t beat The Onion: The Top 6 Happiest Countries In The World

Have to talk about Ebola:

Best chronology of what’s happened so far – heroism of health workers, sluggish international response etc. [h/t Chris Blattman]

Harrowing, heartbreaking account of an overrun hospital in Makeni, Sierra Leone [h/t Laurence Chandy]

‘Donors value the life of someone in Britain twenty times more than someone in Sierra Leone.’ The brutal underlying economics

and The Economist reminds us that even though it is rising fast, Ebola is still lagging other killers in West Africa

and The Economist reminds us that even though it is rising fast, Ebola is still lagging other killers in West Africa

Meanwhile, back in the land of good news

The political impact of taxes: In Uganda, taxation increases citizens’ willingness to punish leaders by 12% overall, and by 30% among the main taxpayers

Huge congrats to Greenpeace as LEGO quits branding ties with Shell

And here’s the video (6 million hits and counting) that did the job

October 9, 2014

9 Ways to get northern constituencies involved in changing the world: useful typology

Like everyone else, if Buzzfeed is any guide, I love a good list. I’m also increasingly obsessed with theories of change. So imagine my joy when I read Exfamer May Miller-Dawkins’  paper ‘9 Ways to Change the World’, which offers not one, but two lists.

paper ‘9 Ways to Change the World’, which offers not one, but two lists.

The paper is an attempt to come up with a typology of the ways organizations try to engage northern constituencies on global issues, but as an added bonus, it throws in a useful set of 5 ‘meta trends’ that provide the backdrop to their efforts:

Geo-political shifts: decline of the North, rise of the G20 etc

Migration, identity, and connection: ever denser networks of connections between individuals across the world, including migrant Diasporas. ‘Here’ and ‘There’ just not as divided as they used to be.

Interdependence and learning: resource scarcity, climate change, rights – if we’re all in this together (to coin a phrase), a northern ‘us’ lending a helping hand to a southern ‘them’ doesn’t fit any more

Science and technology: A great enabler of communications and contact but of course, open to abuse and no substitute for politics and power

Space for citizen action: The rise of civic activism has been rapidly accompanied by attempts to repress it. Civil society space is very messy and in many places, dangerous. What role if any is there for more privileged northern citizens to give some backing?

Each of the nine theories of change gets a few pages, including an exploration of who has agency, and what kinds of tactics and infrastructure are required. They are:

Charity (self explanatory)

Market-oriented aid funding (supporting business and social enterprise)

Mutual aid and cooperation (preferred by many Diaspora communities, but also fairtrade and open source tech, for example)

Behaviour change (eg transition towns or changing consumption patterns)

Building empathy and global citizenship (often linked to school curricula, but also volunteering)

Social mobilisation (often involving campaigns to change government policy or practice)

Monitory democracy (scrutiny across borders by civil society or media)

Leadership and international networks (lots of programmes invest in ‘leadership development’ through training, scholarships etc. Affirmative action can help tilt the make up of such leaders to combat social exclusion.

Meta-movements: much looser ‘living life differently’ movements, eg Occupy. Aim for a different way of living more than specific policy changes.

According to May:

‘These models demonstrate a variety of conceptualisations of where change is located, who the agents of change are and what infrastructure or tactics are required to bring about such shifts. Some models underscore the role of the nation state and domestic formal politics, while others privilege the local, or alternatively, transnationalism and global pathways to change. Some models reflect old realities of the dominant power of the ‘north’ and large INGOs, while others bypass traditional institutions and rely on direct connections.

Our hope is that people trying – in their various ways – to contribute to global justice will find this a useful framework for reflecting on and even reconceptualising their own approaches.’

Which is really the point – if they’re any good, typologies of this kind widen your mental map, pointing out some of the approaches you haven’t thought of yet, and which might be worth trying out.

And here’s their effort to squeeze all that into a monumental infographic

October 8, 2014

DFID is changing its approach to better address the underlying causes of poverty and conflict – can it work? Guest Post from two DFID reformers

Aid donors are often maligned for bureaucratic procedures, a focus on short-term results at the expense of longer-term, riskier

Aid donors are often maligned for bureaucratic procedures, a focus on short-term results at the expense of longer-term, riskier institutional change, and a technical, managerial approach to aid with insufficient focus on context, power and politics. Are these institutional barriers insurmountable? Can aid agencies create an enabling environment to think and work politically? Tom Wingfield (left) and Pete Vowles (right) from DFID’s new ‘Better Delivery Taskforce’ have been trying to do just that. Here’s where they’ve got to.

institutional change, and a technical, managerial approach to aid with insufficient focus on context, power and politics. Are these institutional barriers insurmountable? Can aid agencies create an enabling environment to think and work politically? Tom Wingfield (left) and Pete Vowles (right) from DFID’s new ‘Better Delivery Taskforce’ have been trying to do just that. Here’s where they’ve got to.

For the past year DFID has been focussing on these issues and how we can both guard taxpayer’s money and have transformational impact in the countries where we work. The result has been the introduction of a comprehensive set of reforms targeting our process, capability and culture. This is about creating the conditions that allow us to better address the underlying causes of poverty and conflict, and respond effectively to the post-2015 agenda. At the heart of the reform is a revamp of DFID’s operating framework (ie the rules and principles which govern our work). Known as the ‘Smart Rules’, it can be downloaded here.

Like any institutional reform, this is a long term change process. The next 12 months provide a real opportunity to strengthen our partnerships with a wide range of partners and enhance our collective effectiveness.

What’s the problem?

The challenges facing aid agencies have been well aired – see Duncan’s two blogs on the subject in November and January and recent guest blogs by Alina Rocha Menocal and Neil McCulloch. The list of institutional barriers include – fear of failure, risk aversion, ‘projectization’, a focus on short-term results and staff turnover. In our original review of DFID’s programme management cycle, internal and external consultations recognised these challenges and a few more (see Pete’s blog on Adaptive Programming).

Agreeing the problem is the easy part (and often where most of us stop). So the challenge is a) how do we create a reform moment and b) what can we actually do to change things when the moment arrives?

To really address the problem means creating space to understand and engage with local context and having the freedom (and capability) to design flexible and adaptive programmes. It means freeing up time for frontline staff to work on what matters most (not empty process, box ticking) and being honest about failure and learning from what goes wrong. This is difficult for any large organisation

What are the key changes?

DFID has recognised that improving our processes is important but not enough on its own. Through a process of consultation, piloting, thinking and rethinking, we are introducing reforms in three areas:

DFID has recognised that improving our processes is important but not enough on its own. Through a process of consultation, piloting, thinking and rethinking, we are introducing reforms in three areas:

Process: Our new operating framework focuses on stripping back process, reducing internal bureaucracy and removing non-value added approval layers. We’ve cut more than 200 compliance tasks (and mountains of guidance) to 37 straightforward rules, introduced 10 principles to guide programming (e.g. context specific, evidence-based, honest, proportionate and balanced) and set out a series of discretionary standards which help define ‘good development’ in practice (e.g. undertaking political economy analysis, risk management and ‘do no harm’). This is framed around a single Country Poverty Reduction Diagnostic which looks at the underlying barriers to poverty reduction, the space for UK action and the most transformational investments. Four elements underpin the Smart Rules:

Moving from rules to a more principles-based approach, creating deeper ownership and engagement across DFID

Directing DFID’s effort proportionately on what matters most (ie by removing generic mandatory compliance tasks)

Simplifying and clarifying mandatory rules, designed to protect tax payers money

Demonstrating the space for discretion where we will trust the judgement of frontline staff to innovate, take risks and adapt to realities on the ground

Capability: Managing flexible and adaptive programmes is an art form. DFID is making a major investment to improve programme management and leadership while maintaining our cadre of technical advisers. We recognise the conventional linear, apolitical approach and assumptions are not going to work in many of the contexts where we operate. We want to build our collective capability by finding more effective ways to share lessons from real world delivery on the ground and tap into our implementing partners’ expertise (NGOs, private contractors, partner governments).

Incentives and culture: The third, and probably most important, reform focuses on empowering staff to use professional judgment, generating open dialogue on lesson learning and failure, and running towards problems, in the knowledge that poor performing programme never self-correct.

How you can help

In his recent blog on thinking and working politically, Neil McCulloch lamented that: “An approach that subordinates money to a thorough understanding of context and a desire for sustainable results will achieve more in the long-run than the current focus on ‘delivering’ (i.e. buying) results. Sadly the political economy of donor incentives means that it will probably remain a marginal pursuit.”

Sadly the political economy of donor incentives means that it will probably remain a marginal pursuit.”

DFID’s reform is trying to move the marginal to the mainstream. We know that success depends on feedback loops to encourage challenge (internally as well as externally), to admit mistakes and adapt along the way. We freely acknowledge that we don’t have all the answers and that we need need our partners – national governments, NGOs, private suppliers, citizens – to keep us real and test whether change is being felt on the ground. We are genuinely interested in your views on:

How we can continue to improve

What changes you are seeing happening (the positive and the negative)

You can email us directly on T-Wingfield@dfid.gov.uk or P-Vowles@dfid.gov.uk

October 7, 2014

New research: A wage revolution could end extreme poverty in Asia, with massive knock-on effects in Africa

Spoke last week as a ‘discussant’ (my favourite speaking role, no prep required) at the launch of an extraordinary new ODI paper, with the deeply forgettable title ‘rural wages in Asia’ (we’ll come back to the title later).

In one of those papers that restores your faith in economists, Steve Wiggins and Sharada Keats crunch the available data on 13 large Asian countries and find some intriguing patterns:

find some intriguing patterns:

Rural wages are rising across much of Asia, and in some cases have accelerated since the mid 2000s.

And they are doing so fast (and getting faster) – see rather busy powerpoint slide, right, for real wages in five Chinese provinces. Doubling in China in the last decade, tripling or quadrupling in Vietnam. A bit slower in Bangladesh, but still up by half. This really matters because landless rural people are bottom of the heap (72% of Asia’s extreme poor are rural – some 687m people in 2008), so what they can pick up from their casual labour is a key determinant of poverty, or the lack of it. Steve argues that if the trend continues (and it looks like it will) this spells ‘the end of mass (extreme) poverty in Asia’.

The two main drivers are a slowdown in the growth of the rural labour force, probably mainly from lower fertility rates, and the growth of manufacturing that attracts workers from rural areas.

The authors ran a cross country regression and were surprised to find population as the biggest causal factor – rural populations are falling across much of Asia, labour shortages are even appearing in Bangladesh, and wages are responding (Steve: ‘music to your ears. As an agricultural economist, it’s what you dream of hearing’). Policy wonks take note: this shows that the underlying structural causes or rising wages are primarily structural, not down to our cherished policies like India’s Employment Guarantee Act.

Higher rural wages are driving up the cost of food production, thereby creating opportunities for other countries to export to Asia.

Steve argues that this will undermine Asian countries’ preference for self sufficiency in food (they’ve already come to rely on imports for vegetable oil and animal feed), opening up big new markets for food exporters.

They also contribute to higher wages in manufacturing. As costs rise in China, for example, it is likely that some plants will relocate to low income Asia and to Africa.

Collapsing fertility rates

Former World Bank chief economist Justin Lin has talked about 80 million manufacturing jobs leaving China as wages rise. Many of those could go to Africa, as the last global repository of truly cheap labour. Steve talked about ‘a beautiful marriage of convenience between Africa’s youth bulge and Asia’s rising wages’)

There are some exceptions – the Philippines have not seen rural wages rise, and there has been no fall in rural population or growth in manufacturing (which sort of supports the paper’s thesis).

If this is true, (and I have no reason to believe it isn’t), the implications are momentous. We always wondered if China’s ‘reserve army of labour’ was so large that it could endlessly industrialize and wages would never rise, because more millions of peasants would simply move from the countryside. The remaining poor countries would be best advised to give up on the manufacturing dream and stick to extractives and agriculture.

But now other large Asian countries are reaching the end of that phase and some jumbo jet-sized ‘flying geese’ are about to take off, leaving the way for Asia’s remaining low income countries, and Africa to follow in their wake. Their governments need to dust off those industrial policy plans and get to work.

The focus on shrinking rural populations is also intriguing – is this the biggest success story yet for women’s education, empowerment and sexual/reproductive rights (at least outside China, whose fertility fall is based more on coercion)?

The research begs lots of questions – Steve and Sharada have ‘no idea’ why an acceleration seems to have begun in the mid 2000s, or why wages between rich and poor regions within countries (and between men and women) are converging. For once, ‘NMR’ (needs more research) is fully justified.

I raised a couple of other questions: what does this mean for inequality, both horizontal (eg rural-urban) and vertical (income)? If China suddenly opens its doors to food imports, will it trigger a price shock on a par with the 2008 food price spike?

Finally, if the findings are so earth-shattering, how come only a handful of people showed up to discuss them? The ODI has done its customary comms bells and whistles (see infographic, below), but I think it got one thing badly wrong – the title. When I skimmed my RSS feed, I passed swiftly over ‘rural wages in Asia’ – who’s going to click on that? I suggest that ‘Mass poverty in Asia is ending, with no need for any post-2015 malarkey’ would have got a bigger turnout. Steve, an ag economist to the core, was baffled – ‘wages are really exciting – we’re like dedicated motor mechanics – how could anyone not be fascinated by carburettors?!’ Sweet.

October 6, 2014

The highs and lows of peacekeeping in South Sudan

Oxfam’s head of humanitarian policy and campaigns, Maya Mailer (@MayaMailer), just back from South Sudan, reflects on some major progress in UN  peacekeeping, with mountains still to climb.

peacekeeping, with mountains still to climb.

‘Even if an attack was happening right outside our base and we could see it, we would close the doors. Our job isn’t protecting civilians but monitoring the peace agreement’.

This is what a UN peacekeeper told me in South Sudan back in autumn 2009. I will never forget the resignation with which he uttered those words. We were in Yambio, close to the border with DR Congo, where the brutal Lord’s Resistance Army had been on the rampage. Earlier that day, I had spoken to a group of boys who had described the atrocities they’d witnessed. Now armed, mainly with bows and arrows, known as the ‘Arrow Boys’, they were patrolling the bush to protect their communities from further attacks. They were angry and baffled that the nearby peacekeepers had done nothing to help them (see my report on this more).

On the one hand, I was outraged at the injustice. How could it be that boys had dropped out of school to protect their families while peacekeepers hunkered down in their bases? But on the other hand, I felt sorry for that peacekeeper. He was thousands of miles from his home. He hadn’t received clear instructions or training from the UN as to what protecting civilians really meant. And while the UN mission had a mandate from the UN Security Council to protect civilians, that came way down a long list of other priorities. In any case, like many peacekeepers, he was almost certainly receiving instructions from his own government not to get in harm’s way.

Women and children shelter in the Malakal IDP camp (Simon Rawles/Oxfam)

Fast forward five years and I am walking around a UN peacekeeping base in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, which is now home to thousands of displaced civilians. Their community leader is telling me that they owe their lives ‘to the UNMISS’. Today, South Sudan’s peacekeepers are sheltering around 100,000 men, women and children. When violence gripped Juba last December, and spread to other parts of the country, the UN peacekeepers opened their doors, and in doing so, saved hundreds if not thousands of lives.

What caused this radical change in the UN mission’s approach? Cynics would say it was the sheer force of circumstance. As one tired aid worker put it to me, ‘it would have been a PR disaster’ if the UN had turned away the crowds that descended on its bases.

Perhaps. But I believe UNMISS deserves more credit. It had contingency plans to host civilians (even if, like the rest of us, it did not anticipate anywhere near the numbers of people that would seek safety). It showed leadership and resolve in letting people in. I also like to think that the painstaking advocacy that NGOs, including Oxfam, have done over the years on civilian protection played a part. At a more abstract level, could this be the influence-by-osmosis of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ concept that my colleague Ed Cairns wrote about here, or the impact of the UN’s ‘Rights Up Front Initiative’ that emerged following the human rights failures during Sri Lanka’s civil war? Whatever the reason, in my mind UNMISS actions in South Sudan amount to a major UN protection achievement.

But that does not mean, ten months later, that UNMISS is doing enough. A fraction of South Sudan’s conflict-affected people are in formal ‘Protection of Civilian’ (PoC) sites. UNMISS should patrol much more robustly and actively outside of these camps so that, for example, women can go to market without being attacked. Peacekeepers should get out of their vehicles, patrol by foot, talk to communities. Women in Malakal recently said that where Rwandan peacekeepers are taking this more proactive approach, they feel safer.

Even in the PoC sites themselves, people face a range of threats – some of which, ironically, are a result of living in the very camp to which they fled for

Malakal IDP camp, where recent rains are making life intolerable for civilians. (Simon Rawles/Oxfam)

protection. There is next to no privacy; people (especially the young) are bored, frustrated, penned in; and women and girls are experiencing high levels of sexual violence. While improving, conditions in the camps range from tough to abominable. In the site in Bentiu, it has been so swampy that families sleep standing up knee deep in mud (see MSF video). That people choose to stay in such conditions is a measure of how frightened and traumatised they are about what will happen if they leave.

A similar story can be told about South Sudan’s hunger crisis. The collective effort of aid agencies together with the incredible resilience of the South Sudanese has pulled communities back from the brink of starvation. But the risk of famine early next year remains real and there can be no let up in our efforts, as Oxfam and 35 agencies describe in a new report, From Crisis to Catastrophe: South Sudan’s man-made crisis – and how the world must act now to prevent catastrophe in 2015.

But no amount of peacekeeping, however robust, and no amount of aid, however effective, can end wars. Only the leaders of South Sudan can end this conflict – a conflict which has exacted a most devastating toll on men, women and children who were so hopeful that, after decades of violence and poverty, an independent South Sudan would mean a brighter future.

And that brings me to the toughest question of all: what can be done to change the calculations of the warring leaders to make peace rather than wage war? I don’t have the answer. I’m not sure if anybody does. But surely part of it must be about exposing the fundamental inequality of this conflict: that those most responsible for unleashing violence are most immune from its consequences. As a South Sudanese friend, a young mother of two, said on my recent trip: ‘Those two men are safe. Their wives and children are outside of the country, going shopping and to school. They are safe. But here our children are dying.’ She concluded with the proverb: ‘When two elephants fight, it’s the grass that is flattened.’

October 5, 2014

Links I liked

Hold those Monday morning emails while you squander a few minutes on the highlights from last week’s tweeted clickbait (@fp2p)

Wondering what to think about bombing ISIS/ISIL/IS (and could someone please explain why it has so many acronyms?) This excellent piece from Alex Evans makes a strong case against.

The horror of air travel, beautifully spoofed by The Onion: Report from Franz Kafka Airport. [h/t George Monbiot]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?wmode=t...” width=”WIDTH” height=”HEIGHT” >

This week’s Inequality links

Latin America’s impressive recent falls in inequality seem to be running out of steam. What happens next?

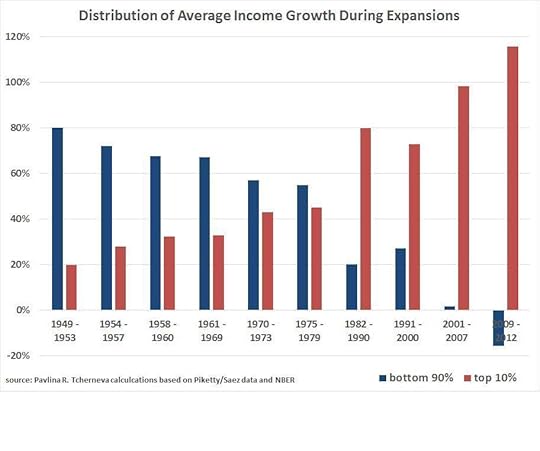

One of the best US inequality charts yet. Benefits of US growth are getting more and more unequally distributed [h/t Ben Phillips]

Is Muslim feminism different from the Western kind? ‘What do Muslim women want? Finding women’s rights in Islam’

‘The strongest predictors of violence are social and ethnic cleavages, and minority group power-sharing’. Chris Blattman finds that data from 242 Liberian communities provide strong ability to predict local conflict

Some meritocratic nepotism as my sister-in-law Mary Matheson cranks out another great video on girls’ rights, this one ‘co-created with youtube trenders’ (I think those are people who teach you how to put on make-up and stuff)

October 2, 2014

Why Inequality is a (very) Big Deal, and you need to get involved

I wrote this puff for Blog Action Day on 16th Oct – it appeared on Oxfam International’s site earlier this week. If you’re a blogger and want to join in the inequality theme, sign up here.

A few years ago I was touring the US to promote my book, From Poverty to Power, which focuses on inequality and redistribution. Big mistake. Even the  word ‘redistribution’ was so politically loaded that it effectively closed down debate (it was just after the row over then presidential candidate Obama’s exchange with Joe the Plumber on ‘spreading the wealth’). I ended up replacing ‘redistribution’ with ‘rebalancing’ on the powerpoint.

word ‘redistribution’ was so politically loaded that it effectively closed down debate (it was just after the row over then presidential candidate Obama’s exchange with Joe the Plumber on ‘spreading the wealth’). I ended up replacing ‘redistribution’ with ‘rebalancing’ on the powerpoint.

How times change. Now a 700 page book on inequality is a global bestseller, while everyone from the IMF and World Economic Forum leftwards is lamenting the extremes of global inequality, and its negative impact on everything from human rights to economic growth. Oxfam’s killer fact that the world’s 85 richest individuals own as much as its 3.5 billion poorest people was the talk of Davos this year. Later this month, we are launching a global campaign to tackle extreme economic inequality. Here are a few pointers to what we will be saying.

First inequality of what? Normally, the focus is on income, and in the case of Thomas Piketty’s tome, wealth. But the division of the world into haves and have nots is at its root about power – the gulf between those who have it, and those who don’t, aka (in the deadening jargon of development) the ‘excluded and marginalized’. That covers everything from physical security (e.g. violence against women), to norms and culture (indigenous or sexual identity, attitudes to disabled or elderly people) to land rights, as well as the more traditional focus on income and assets. Often the inequalities are overlapping and mutually reinforcing – a poor, disabled, elderly indigenous woman faces an interlocking set of obstacles to having her voice and desires heard and responded to by those in power.

For Oxfam, redistributing power – both ‘power within’ in terms of a sense of rights and self esteem, as well as ‘power with’(the ability to organize) as well as ‘power to’ get things done, change laws and practices etc, underpins all other discussions of inequality. If that all sounds very abstract, listen to the impact on a woman taking part in a programme to set up civilian protection committees in the violence-torn Eastern Congo: ‘I got married very young. I didn’t know that women could sit and talk to people the way that we are doing right now. We had shadows in our eyes. But now we talk even to local authorities, and even to the military.’

People on the sharp end of inequality have always tried to improve their lot through everything from cultural resistance (language, song, dress) to public protest and insurrection. Whether you are compatriots or outsiders, if you want to support them you can help in numerous ways. In your personal lives you can challenge the norms and value systems that reproduce inequality (India’s caste system, or the rights of children). As activists, you can make a difference through a host of citizen’s movements, faith groups and political organizations. Or you can support others, such as Oxfam and other international NGOs, who are working for that essential global redistribution of power and wealth.

People on the sharp end of inequality have always tried to improve their lot through everything from cultural resistance (language, song, dress) to public protest and insurrection. Whether you are compatriots or outsiders, if you want to support them you can help in numerous ways. In your personal lives you can challenge the norms and value systems that reproduce inequality (India’s caste system, or the rights of children). As activists, you can make a difference through a host of citizen’s movements, faith groups and political organizations. Or you can support others, such as Oxfam and other international NGOs, who are working for that essential global redistribution of power and wealth.

But we also need to get better at telling the story of inequality, and its defeat. An exclusive focus on injustice can be demobilizing, even patronising, if we fail to understand and celebrate the numerous struggles going on to confront it, from global victories such as trade union rights, the abolition of slavery or women’s suffrage, to the unsung liberation of a woman in Eastern Congo, speaking up for the first time. Bloggers and social media have a role here, bearing witness, building understanding, linking what can often seem a dry academic discussion of Gini indexes, social exclusion and the like to the human drama of struggle.

So now it’s over to you. You can start by blogging/tweeting your views and stories to make sure that inequality goes viral on Blog Action Day on October 16th.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers