Duncan Green's Blog, page 177

October 29, 2014

Even it Up: Big global campaign on inequality launched today

Today Oxfam launches Even It Up, its big new inequality campaign. For me, the most striking killer fact from the launch report:

‘The number of billionaires has doubled since the financial crisis, as inequality spirals out of control. In the same period, at least a million mothers have died in childbirth due to a lack of basic health services.’

Although ‘In South Africa, the two richest people have the same wealth as the bottom half of the population’ runs it pretty close.

You can read the report or sign up for the campaign

In case you need some persuading, here are what some very big cheeses have to say:

Graça Machel: This report is a stark and timely portrait of the growing inequality which characterises much of Africa and the world today. Seven out of ten people live in countries where inequality is growing fast, and those at the top of society are leaving the rest behind.

Credit: Paul Smith/Panos

Addressing the gap between the richest people and the poorest and the impact this gap has on other pervasive inequalities between men and women and between races that make life for those at the bottom unbearable is an imperative of our times. Too many children born today have their future held hostage by the low income of their parents, their gender and their race.

The good news is that this growing inequality is not inevitable. It can be resolved. The report contains many examples of success to give us inspiration. I hope that many people from government officials, business and civil society leaders, and bilateral and multilateral institutions will examine this report, reflect on its recommendations and take sustained actions which will tackle the inequality explosion.

Kofi Annan: The widening gap between rich and poor is at a tipping point. It can either take deeper root, jeopardising our efforts to reduce poverty, or we can make concrete changes now to reverse it. This report is a call to action for a common good. We must answer that call.

Joe Stiglitz: The extreme inequalities in incomes and assets we see in much of the world today harm our economies, our societies, and undermine our politics. Whilst we should all worry about this it is of course the poorest who suffer most, experiencing not just vastly unequal outcomes in their lives, but vastly unequal opportunities too. Oxfam’s report is a timely reminder that any real effort to end poverty has to confront the public policy choices that create and sustain inequality.

Andrew Haldane: When Oxfam told us in January 2014 that the world’s 85 richest people have the same wealth as the poorest half of humanity, they touched a moral nerve among the many. Now this comprehensive report goes beyond the statistics to explore the fundamental relationship between inequality and enduring poverty. It also presents some solutions. In highlighting the problem of inequality Oxfam not only speaks to the interests of the poorest people but in our collective interest: there is rising evidence that extreme inequality harms, durably and significantly, the stability of the financial system and growth in the economy. It retards development of the human, social and physical capital necessary for raising living standards and improving well-being. That penny is starting to drop among policymakers and politicians. There is an imperative – moral, economic and social – to develop public policy measures to tackle growing inequality. Oxfam’s report is a valuable stepping stone towards that objective.

Jeffrey Sachs: Oxfam has done it again: a powerful call to action against the rising trend of inequality across the world. And the report comes just in time, as the world’s  governments are about to adopt Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. Sustainable development means economic prosperity that is inclusive and environmentally sustainable. Yet too much of today’s growth is neither inclusive nor sustainable. The rich get richer while the poor and the planet pay the price. Oxfam spells out how we can and must change course: fairer taxation, ending tax and secrecy havens, equal access of the rich and poor to vital services including health and education; and breaking the vicious spiral of wealth and power by which the rich manipulate our politics to enrich themselves even further. We should all rally to the cause of inclusive, sustainable growth at the core of next year’s SDGs.

governments are about to adopt Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. Sustainable development means economic prosperity that is inclusive and environmentally sustainable. Yet too much of today’s growth is neither inclusive nor sustainable. The rich get richer while the poor and the planet pay the price. Oxfam spells out how we can and must change course: fairer taxation, ending tax and secrecy havens, equal access of the rich and poor to vital services including health and education; and breaking the vicious spiral of wealth and power by which the rich manipulate our politics to enrich themselves even further. We should all rally to the cause of inclusive, sustainable growth at the core of next year’s SDGs.

Jay Naidoo: All those who care about our common future should read this report. Rising inequality has become the greatest threat to world peace, and indeed to the survival of the human species. The increasing concentration of wealth in the hands of very few has deepened both ecological and economic crises, which in turn has led to an escalation of violence in every corner of our burning planet.

Rosa Pavanelli: The answers Oxfam provides are simple, smart and entirely achievable. All that stands between them and real change is a lack of political will. Our job is to make the cry heard. To give action to the urgency. To ceaselessly expose the injustice and demand its resolution. The time to act is now.

Ha-Joon Chang: Even It Up is the best summary yet of why tackling inequality is crucial to global development. The gulf between haves and have-nots is both wrong in itself, and a source of needless human and economic waste. I urge you to read it, and join the global campaign for a fairer world.

Michael J. Sandel: The growing gap between rich and poor makes poverty more intractable. It also erodes the civic bonds and common life that democracy requires. Oxfam’s inequality campaign will invigorate public debate about one of the great moral challenges of our time.

Sharan Burrow: Today millions of working people are struggling to provide for their families and the hopes of a better future for their children are at stake. Corporate dominance is capturing governments and putting jobs and economies at risk. The counterbalance and the basis of democracy is the power of working people and their families and communities. Even It Up puts workplace democracy at the heart of solutions to tackle inequality. People want governments to intervene to guarantee that companies pay workers a living wage, to close tax loopholes and to implement a social protection floor. Together with Oxfam, we demand that that governments change the rules so the economic system stops favouring the wealthy and is fair to everyone.

Convinced?

October 28, 2014

What if we scrapped The Project – are there better ways to fund development?

Yesterday I gave some general feedback on last week’s Doing Development Differently conference. Today I want to talk about projects, or rather The Project. Joel Hellman of the World Bank  gave the following definition:

gave the following definition:

What is a project?

- Time bound (1-5 years)

- A Legal Agreement

- A cluster of contracts – employment, implementing partners, consultants, evaluation. All of them work within a set of rules, set both by donors and recipient governments.

- A predetermined set of results (the focus on these has increased in recent years due to logframe/metrics fetishism – my words, not Joel’s)

- Post review audit and evaluation of those results

How did this particular construct come to be so all powerful in the aid and development sphere? I remembered this quote from Ros Eyben’s wonderful book, International Aid and the Making of a Better World

‘The project is a device that development agencies use to organise complex reality into a manageable, bounded unit. In 1966, Hirschman referred to them as ‘privileged particles of the development process’. Back then, in addition to providing Third World governments with ‘manpower’ for health, education and other services along with some budget support, international aid provided infrastructure projectised in the same manner as the construction of roads, bridges,etc. back home. In theory, recipient governments presented fully designed projects for funding and the aid agency then appraised their viability and relevance. In practice, aid agencies, equipped with budgets that had to be spent in a timely manner, actively encouraged recipients to think of useful schemes that fitted the project paradigm.

A project was seen as a capital investment, which was then (in principle, often not in practice) maintained by the recipient government. Early projects produced something concrete – such as a power station or hospital – but by the 1970s the United Nations specialised agencies were using the project model for an expanded range of objectives, such as the ILO Youth Training Centres Project that gave me my first job as a development professional. Although by then aid agencies perceived development as more complicated than initially thought and needing more than bridges and roads, the project had become the default aid instrument. It produced the patent absurdity of a single management structure, budget and determined time frame for ambitious and nebulous concepts such as meeting basic needs through integrated rural development. Yet, external support to development at the local level without projects had become inconceivable. Development professionals, including anthropologists like me, had to work within this framework.’

An example of why this matters. Andy Ratcliffe of the African Governance Initiative, which supports government reform processes in West Africa, told me that they were only able to respond properly to the Ebola crisis because their funding has come from more flexible sources like Foundations and individuals (it apparently still helps having Tony Blair as your patron).

An example of why this matters. Andy Ratcliffe of the African Governance Initiative, which supports government reform processes in West Africa, told me that they were only able to respond properly to the Ebola crisis because their funding has come from more flexible sources like Foundations and individuals (it apparently still helps having Tony Blair as your patron).

That meant that when the disease struck the countries they were working in, they were able to go to the governments in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone and say, do you want us to get out of the way (as you won’t be doing much on education, infrastructure etc until this is over)? Instead, Liberia and Sierra Leone asked them to stay and help manage relations with donors: ‘AGI is a friend in need – we know you’re on our side, please stay and help’. Switching like that would have been much harder had they been stuck in a rigid project funding format.

So as a thought experiment, what would be a way to disburse aid without using projects, and in a way that is more compatible with the kind of models discussed at last week’s seminar? Are there better ways than projects to fund relationships, trust-building, facilitation, brokering etc?

Off the top of my head, here are some possible alternatives:

Fund people, not projects: This happens in lots of other areas, from Howard Hughes genius grants to scholarships and fellowships. Why see those as only suitable for recent graduates? You could have a graduation system, where aid funds a number of apprenticeships, and then the best are given longer term fellowships? Or standing arrangements for mentoring and coaching, for example by retired politicians and civil servants who know how reforms work and get blocked?

Then there is Payment by Results (although if you define the results very narrowly, and stick in lots of milestones and benchmarks, it starts to look a lot like a project).

Prizes such as Advance Market Commitments.

Any other ideas?

October 27, 2014

Doing Development Differently: Report back from two mind-blowing days at Harvard

Spent an intense two days at Harvard last week, taking part in a ‘Doing Development Differently’ (DDD) seminar, hosted by Matt Andrews, who runs Harvard’s ‘Building  State Capability’ programme and ODI. About 40 participants, a mixture of multilaterals and donors (big World Bank contingent), consultants and project design and implementation people, and a couple of (more or less) tame NGO people like me (here’s the participants list).

State Capability’ programme and ODI. About 40 participants, a mixture of multilaterals and donors (big World Bank contingent), consultants and project design and implementation people, and a couple of (more or less) tame NGO people like me (here’s the participants list).

The purpose was to learn from success, based on 15 short (7m) filmed presentations, which are all online, and ensuing discussions. The premise of the meeting was that there is something like an incipient movement around DDD. As you would expect at such an early stage, it is fragmented and messy (people using the same words to mean different things, lack of clarity on what is/is not included, overlap with other initiatives like the Thinking and Working Politically crew etc), and clearer on what it is against (linear thinking, tyranny of the logframe etc) than what it is for. So this meeting aimed to try and clarify terms and ways of thinking, and build something like a community of practice and consensus among adherents.

The main focus of the discussions was how to bring about institutional reform, in particular of the state – the theme covered by Matt’s great book. So lot’s about civil service reform and that kind of thing. But they had some outliers – I spoke about our work supporting grassroots Women’s Leadership Groups in Pakistan. The common elements that emerged from the case studies include:

Iteration: Place lots of small bets, ‘fail fast and cheap’ (a research assistant running off with $20k to have a sex change operation definitely takes the biscuit), make sure you have realtime monitoring and feedback, and mechanisms in place to let you learn and adjust the programme as you go. This is the antithesis of ‘spend 2 years designing the perfect project, and then roll implacably out’.

Success is based on relationships. Your key people have to be deeply immersed in the culture (either because they are local, or at least have lived there for decades rather than years). As an outsider, it’s only when you start getting invited to the weddings that you know you have a chance of understanding what is really going on.

Deep study of the system, based on continuous observation and listening. In Nicaragua, UNICEF sent public officials out to try and access the public services they were administering, and even made the men carry 30lb backpacks to experience what it’s like being pregnant! This is all about immersion, rather than the traditional ‘fly in, fly out’ consultant culture.

Quick wins are vital to build momentum. Low morale is often a major obstacle – state officials resigned to the impossibility of change. So showing quick results both builds confidence, and gets the big bosses excited and supportive.

Quick wins are vital to build momentum. Low morale is often a major obstacle – state officials resigned to the impossibility of change. So showing quick results both builds confidence, and gets the big bosses excited and supportive.

Brokering is often more important than delivery. A lot of the work involves brokering discussions between different state bodies who seldom talk to each other, or between donors and governments who are at loggerheads. Facilitation skills are crucial.

Incrementalism: This approach favours lots of small steps, going with the grain of existing institutions, rather than big bangs or shock therapy

So what are the problems with such an approach? In terms of making it function in the current aid environment:

First, it is heavy on staff and salaries – building relationships, mentoring and coaching etc takes time, tricky if the donor is determined to shift lots of money fast.

It is often necessary to try and ‘get the cash off the table’ so that officials’ eyes are on finding solutions to problems, rather than dazzled by dollar signs. Options include pushing it into ‘payment by results’ (I was struck by how far the World Bank has moved on this), having no money anyway (an NGO speciality) or making it clear from the beginning that big contracts are not on offer.

Results are a ‘perennial problem’. ‘We’re best when we are invisible’ said one speaker, but how do you demonstrate results while being invisible? Interesting discussions on whether we need to develop new metrics to measure trust – an equivalent to the private sector’s obsessive monitoring of brand loyalties. In any case ‘unless we can demonstrate value for money, this wave may pass’.

Results are a ‘perennial problem’. ‘We’re best when we are invisible’ said one speaker, but how do you demonstrate results while being invisible? Interesting discussions on whether we need to develop new metrics to measure trust – an equivalent to the private sector’s obsessive monitoring of brand loyalties. In any case ‘unless we can demonstrate value for money, this wave may pass’.

Who in the aid business stays anywhere for 10 years? Not if you want to develop your career, anyway. Success seems to involve handing over power and control to local staff or partners – something the big donors seem to find rather difficult.

But I have some broader concerns, which echo some of my worries about elements of the ODIs Africa Power and Politics Programme. Namely, what are the politics of all this? For all its talk of understanding context, politics etc, the overall discussion felt extremely technocratic. Understanding politics appears to be mainly of instrumental value in that it helps you implement a reform programme more effectively, but there was little discussion on who decides the content of the programme. So are we talking about tweaks or transformation? Is everything win-win, or are there sometimes conflicts because someone loses out? Does it matter whether we apply these approaches in an autocracy or a democracy? Apparently not. A few times I raised the issue of power and social justice, and how it distorts relationships and policy choices, but should be at the centre of what we do, but this was largely shrugged off – I’m starting to realize how gender advisers must feel.

And then there was a fascinating conversation about the tyranny of ‘The Project’, but that will have to wait for tomorrow.

October 26, 2014

Links I liked

I’m off on holiday this week, and even it rains, that at least means I can escape from the irritation of wall to wall Russell Brand for a bit. Meanwhile, for those of you condemned to work on a Monday morning, here’s the highlights of last week’s tweets (don’t worry, nothing about RB). And blog backlog means FP2P will roll on in my absence – sorry.

European golfers v African migrants trying to jump the fence in Melilla, via Jaime Atienza

V odd. In New Zealand, you can name your baby ‘Number 16 Bus Shelter’, but not ‘Sex Fruit’. And ‘Duncan’ is illegal in Iceland.

Power of telly, continued. Talk Show inspires over a million callers to protest against India’s Anti-Gay Law

Tescos is imploding. Maybe it was all that money spent on invading Denmark that started the rot – a nice 2006 satire.

How understanding and measuring the care economy led to better programmes (and increased income for farmers) in Bangladesh.

Brilliant, challenging (for faith-based liberals) John Gray essay on the dangers of seeing politics as a battle between good and evil

Two fascinating African success stories in the news last week. Somaliland is inspired by Scotland and Catalonia independence campaigns, while Botswana’s elections prompted this profile of its intriguing president Ian Khama.

Like a fairtrade mark for child welfare. How Nobel Peace Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi’s child-friendly villages are changing rural India.

‘You wanna see this cheap-ass white man again, you better send us $200′. Great aid satire from Saturday night live [ht Chris Jochnick and many others]

October 23, 2014

An authorial moment

This has never happened to me before (sadly), so I thought it was worth recording. And anyway, I’m a suffering author right now, so please indulge me.

She was sitting 3 rows in front of me on the bus from Oxford down to London. Dangly earrings. Cool leather jacket. Handbag probably fashionable (I wouldn’t know). She opens it and takes out a copy of my book – pristine, red first edition of From Poverty to Power. OMG.

What do I do, shout ‘hey that’s my book’? Bus too crowded, and anyway too sad/creepy, so I watch what she does next (also quite creepy, I guess). And then I remember twitter – this is what it was made for:

‘Woman on bus takes out pristine copy of From Pov 2 Power. V excited. But then plays w phone n stares into space instead of opening it. Agony’

Then

‘Oh shxt. What if she follows me on twitter? #stalker #shameup’

Finally

‘She opens it. Back of head supremely bored. Plays w hair, earring. 5m on same page then checks phone. This is hell. Still 30m to my stop.’

And the stuff that doesn’t fit into 140 characters? The way the back of her head radiated boredom, the idle flipping through the pages. The gulf between her stake in all this and mine – will she get into it, absorb/argue/dispute? Or fling it casually on a pile of unread books, a passing fad – ‘do you remember that time when I bought all those awful politics books and couldn’t finish any of them? Ha!’

And the stuff that doesn’t fit into 140 characters? The way the back of her head radiated boredom, the idle flipping through the pages. The gulf between her stake in all this and mine – will she get into it, absorb/argue/dispute? Or fling it casually on a pile of unread books, a passing fad – ‘do you remember that time when I bought all those awful politics books and couldn’t finish any of them? Ha!’

She gets off at Baker St – I feel relief mixed with loss. Now I’ll never know her name or why she had my book. But judging by her reaction so far, that’s probably just as well.

Actually, there has been one comparable moment. Many years ago, in the LSE library, I saw a student slumped across a book I had edited. He was fast asleep. Worrying pattern emerging here.

Any similar tales out there?

Update: thanks for the comments – chortling happily over them

Participatory Evaluation, or how to find out what really happened in your project

Trust IDS to hide its light under a bushel of off-putting jargon. It took me a while to get round to reading ‘Using Participatory Process Evaluation to Understand the  Dynamics of Change in a Nutrition Education Programme’, by Andrea Cornwall, but I’m glad I did – it’s brilliant. Some highlights:

Dynamics of Change in a Nutrition Education Programme’, by Andrea Cornwall, but I’m glad I did – it’s brilliant. Some highlights:

[What’s special about participatory process evaluation?] ‘Conventional impact assessment works on the basis of snapshots in time. Increasingly, it has come to involve reductionist metrics in which a small number of measurable indicators are taken to be adequate substitutes for the rich, diverse and complex range of ways in which change happens and is experienced. [In contrast] Participatory Process Evaluation uses methods that seek to get to grips with the life of an intervention as it is lived and perceived and experienced by different kinds of people.

[Here’s how it works on the ground, evaluating a large government nutrition programme in Kenya]

It was not long after arriving in the area that we were to show the program management team quite how different our approach to evaluation was going to be. After a briefing by the program leader, we were informed as to the fieldsites that had been selected for us to visit. Half an hour under a tree in the yard with one of the extension workers was all it took to elicit a comprehensive matrix ranking of sites, using a series of criteria for success generated by the extension worker, on which three sites we had been offered as a “range” of examples appeared clustered at the very top of the list and one at the very bottom. That we were being offered this pick of locations was, of course, to be expected. Evaluators are often shown the showcase, and having a basket case thrown in there for good measure allows success stories to shine more brilliantly. Even though there was no doubt in anyone’s minds that this was an exceptionally successful program, our team had been appointed by the donor responsible for funding; it was quite understandable that those responsible for the program were taking no chances.

It was therefore with a rather bewildered look of surprise that the program manager greeted our request to visit a named list of sites, chosen at random from various parts of the ranked list, and not the ones we were originally due to visit. What we did next was not to go to the program sites, but spend some more time in the headquarters. We were interested in the perspectives of a variety of people involved with implementation, from the managers to those involved in everyday activities on the ground. And what we sought to understand was not only what the project had achieved, but also what people had thought it might do at the outset and what had surprised them…… These ‘stories of change’ offered us a more robust, rigorous and reliable source of evidence than the single stories that conventional quantitative impact evaluation tends to generate.

Our methodology consisted of three basic parts. The first was to carry out a stakeholder analysis that allowed us to get a picture of who was involved in the program. We were interested in hearing the perspectives not just of program “beneficiaries”, but also of others – everyone who had a role in the design, management and implementation of activities, from officials in the capital to teachers in local schools.

Our methodology consisted of three basic parts. The first was to carry out a stakeholder analysis that allowed us to get a picture of who was involved in the program. We were interested in hearing the perspectives not just of program “beneficiaries”, but also of others – everyone who had a role in the design, management and implementation of activities, from officials in the capital to teachers in local schools.

The next step involved using a packet of coloured cards, a large piece of paper and pieces of string. It began with an open-ended question about what the person or group had expected to come out of the program. Each of the points that came out of this were written by one of the facilitation team on a card, one point per card, and extensive prompting was used to elicit as many expectations as possible. The next step was to look at what was on the cards and cluster them into categories.

Each of these categories then formed the basis for the next step of the analysis, which was to look at fluctuations over time. This was done by using the pieces of string to form a graphical representation, with the two-year time span on the x axis and points between two horizontal lines representing the highest and lowest points for every criterion on the y axis. What we were interested in was the trajectories of those lines – the highs and lows, the steady improvement or decline and where things had stayed the same. We encouraged people to use this diagram as a way of telling the story of the program, probing for more detail where a positive or negative shift was reported.

The third step was to use this data as a springboard to analyse and reflect on what had come out of their experience of the project. We did this by probing for positive and negative outcomes. These were written onto cards. We asked people to sort them into two piles: those that had been expected, and those that were unexpected. We then spent some time reflecting on what emerged from this, focusing in particular on what could have been done to avoid or make more of unexpected outcomes and on the gaps, where they emerged, between people’s expectations and what had actually happened. We kept people focused on their own experience, rather than engaging in a more generalized assessment of the program.

[What kind of reaction did they get?] “We’ve never had visitors coming here who knew so much,” one said to us. Another confided that it’s easy enough to direct the usual kind of visitor towards the story that the program team wanted them to hear. Development tourists, after all, stay such a short time: “they’re in such a rush, they go to a village and say they must leave for Nairobi by 3 and they [the program staff] take them to all the best villages.”

[What kind of things did they uncover?] One of the most powerful lessons that the program learnt came from a very unexpected reaction to something that was utterly conventional: a baseline survey. A team of

enumerators had set out to gather data from a random sample of households, such as height for weight and upper arm circumference measurements. At the same time, a rumour was sweeping the area about a cult of devil-worshippers seeking children to sacrifice. Families greeted the enumerators with hostility. People in the communities likened the measurement kits developed for ease of use to measuring up their children for coffins. The survey proved difficult to administer. In one place, the team were chased with stones.

enumerators had set out to gather data from a random sample of households, such as height for weight and upper arm circumference measurements. At the same time, a rumour was sweeping the area about a cult of devil-worshippers seeking children to sacrifice. Families greeted the enumerators with hostility. People in the communities likened the measurement kits developed for ease of use to measuring up their children for coffins. The survey proved difficult to administer. In one place, the team were chased with stones.

To get things off the ground again, the program needed the intercession and the authority of the area’s chiefs to call their people and explain what the program was all about and what it was going to do for the area. What was so striking about the stories of this initial process of stumbling and having to rethink was that it simply had not occurred to the researchers that entering communities to measure small children might be perceived as problematic.’

Brilliant, and there’s lots more in the paper. Whenever I read anything by Andrea, I wish we had more ‘political anthropologists’ like her writing about development. But maybe we should lend them some subeditors to jazz up their titles a bit.

October 21, 2014

Let’s Talk About Sex: why sexual satisfaction & pleasure should be on the international development agenda

This guest post is by Chloe Safier (@chloelenas), Regional Gender Lead for Oxfam in Southern Africa, with thoughtful contributions from Marc Wegerif

I was sitting at dinner with my Oxfam colleagues on a Sunday night, just before a country strategy meeting. Over grilled fish and cokes, I mentioned an article I’d seen recently in the Guardian that spoke to the need to talk about all aspects of sexual health, beyond the non-controversial medical goals. I had been thinking about that piece, by Institute of Development Studies research fellow Pauline Oosterhoff, and its implications for our international development work. So I broached it with my co-workers: why don’t we talk about sexual satisfaction, intimacy and pleasure as core to our work at Oxfam, particularly in the context of gendered power inequality and sexual and reproductive health and rights?

This is nothing new. Feminists, activists and women’s rights organizations have been talking about sexual pleasure as a critical issue (and a right) for decades. It’s a universal concern that is relevant to everyone, not just in the communities where development work takes place. Students in the UK are campaigning for sex education that includes information about women’s sexual pleasure, based on the reasonable premise that “a greater understanding of female sexuality and a boost to the status of

female pleasure are key in shifting …degrading attitudes and behaviors towards young women.” The Coalition of Women Living with HIV and AIDS in Malawi hosts discussion groups in communities on a range of issues related to HIV/AIDS, and their work includes supporting couples to talk openly about their sexual wants and needs. Articles and reports have been written, like this one by Andrea Cornwall, Kate Hawkins and Tessa Lewin, on the link between sexuality and women’s empowerment; they argue that “not being able to exercise choice in their sexual relationships affects women’s well-being and ultimately undermines political, social and economic empowerment.”

The notion that sexual satisfaction and pleasure is a core aspect of people’s lives hasn’t gained traction amongst international development NGOs, nor in government agendas, donor agencies or in any international protocol. Sexual pleasure doesn’t make an appearance in Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index. There’s no ‘pleasure indicator’ in any widely published index, no UN report on who’s enjoying sex and why. This despite a widespread understanding since the 1980s, building on the work of Amartya Sen, that development must go beyond relieving economic poverty and towards an approach that is centered on human well-being, in which freedom of choice and desire fulfillment are fundamental.

In international development, there is plenty of talk about gendered power relations; that is, how someone’s gender identity ensures or reduces their ability to make decisions, access resources, and take control of their lives. But discussions about gender that treat sex as entirely negative (focusing only on sexualized violence, HIV/AIDS, etc) contributes to perpetuating the notion that the bodies of women and LGBTQI people are just passive recipients of violence rather than active producers of joy and pleasure.

Our present reality is that women and LGBTQI people in almost every part of the world have less power, access and voice than heterosexual cisgender men. The ways in which the patriarchy has been manifest in sexual enjoyment and rights is readily apparent. Female genital mutilation is recognized by many as an abuse of women’s bodies and can be directly linked to the ability to experience sexual pleasure; it’s an area of work where women’s right to sexual pleasure is implicit in the discussions, though explicitly it’s largely spoken about as a woman’s right to bodily integrity. Discrimination and ‘corrective rape’ of lesbian women – who pose a threat to men by taking pleasure in each other’s bodies – show how sexual pleasure can play a political and subversive role in a patriarchal, misogynist society (and can put some women and LGBTQI people at risk).

We know from our feminist foremothers that the personal is political; how sex is negotiated, communicated and articulated between two (or more) people can both reflect  and perpetuate power dynamics, and those power dynamics are often reflective of the way power is negotiated in other spheres of life. It’s empowering for people to know their own bodies and to be able to safely communicate with partner(s). If women aren’t able to negotiate with their partners for their sexual satisfaction, how can they negotiate for condom use, birth spacing or their reproductive choices? If sexuality isn’t celebrated and discussed openly, how will we end the patriarchal norms that suggest sexual pleasure is something a man should control? If certain sexual acts are cast as wrong despite the reality that people take pleasure in them, how can we truly overcome discrimination and homophobia?

and perpetuate power dynamics, and those power dynamics are often reflective of the way power is negotiated in other spheres of life. It’s empowering for people to know their own bodies and to be able to safely communicate with partner(s). If women aren’t able to negotiate with their partners for their sexual satisfaction, how can they negotiate for condom use, birth spacing or their reproductive choices? If sexuality isn’t celebrated and discussed openly, how will we end the patriarchal norms that suggest sexual pleasure is something a man should control? If certain sexual acts are cast as wrong despite the reality that people take pleasure in them, how can we truly overcome discrimination and homophobia?

Narrow assumptions about the enjoyment of sex have harmful effects on cisgender heterosexual men, too, who can be limited by a generalized norm in which a man’s sexual satisfaction is assumed to revolve around ejaculation. Although it’s not equally comparable to the experience of women and LGBTQI people, some men are bound by restrictive constructs of masculinity that prohibit knowing and expressing their sexual wants and needs.

A revised approach to sex within the international development community would make the link between sexual pleasure and power dynamics, choice, health, and rights. It would account for the realities of people’s holistic (and sometimes pleasurable) sexual lives, and further, move beyond the gender binary of women and men. We must acknowledge that our sexual selves, experiences and choices do not exist in a vacuum and are linked to issues of class, race, norms, caste, sexual and gender identity and expression, and other forms of privilege and exclusion.

Perhaps inspired by the aforementioned dinner conversation, the issue of sexual satisfaction (even the right to an orgasm) came up over the next days of the country strategy process. Not surprisingly, it provoked a critical debate and even challenges as to whether we should talk about such an issue at all in our Oxfam meeting.

There was no clear resolution, but at least there was conversation about what sexual and reproductive health and rights really mean – and what we can talk about in spaces where we bring together many people from diverse cultural backgrounds around the shared cause of improving people’s lives. Feminists and women’s rights activists and their organizations have been talking about and working on this issue for ages, and it’s time to take the conversation up in other spaces too.

There was no clear resolution, but at least there was conversation about what sexual and reproductive health and rights really mean – and what we can talk about in spaces where we bring together many people from diverse cultural backgrounds around the shared cause of improving people’s lives. Feminists and women’s rights activists and their organizations have been talking about and working on this issue for ages, and it’s time to take the conversation up in other spaces too.

Ignoring that people have – and enjoy – sex diminishes the full reality of people’s experiences and relationships. If the development and donor communities, could shift their conversations around sexual and reproductive health and rights, empowerment, and gender to include the people’s whole sexual lives, we’d all be better off.

October 20, 2014

How Soap Operas and cable TV promote women’s rights and family planning

Taking a break from the How Change Happens book this week to head off to Harvard for a Matt Andrews/ODI seminar on ‘Doing Development Differently’ + a day at  Oxfam America on Friday. Will report back, I’m sure. Meanwhile, I’ve just finished the draft chapter on the power of social norms, and how they change (and can be changed). ODI provides an absolute gold mine of a crib sheet on this in the shape of Drivers of Change in Gender norms: An annotated bibliography, by Rachel Marcus and Ella Page with Rebecca Calder and Catriona Foley.

Oxfam America on Friday. Will report back, I’m sure. Meanwhile, I’ve just finished the draft chapter on the power of social norms, and how they change (and can be changed). ODI provides an absolute gold mine of a crib sheet on this in the shape of Drivers of Change in Gender norms: An annotated bibliography, by Rachel Marcus and Ella Page with Rebecca Calder and Catriona Foley.

Here’s one of the excerpts that caught my eye:

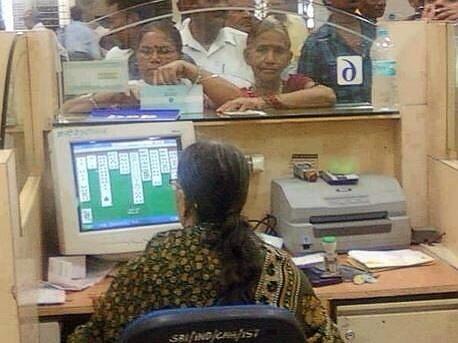

Jensen, R. and Oster, E. (2007) ‘The Power of TV: Cable Television and Women’s Status in India’. Working Paper 13305. Cambridge, MA: NBER

“This paper explores the effect of the introduction of cable television on gender attitudes in rural India. Using a three-year individual-level panel dataset, Jensen and Oster find the introduction of cable television is associated with significant increases in women’s reported autonomy (e.g. the ability to go out without permission and to participate in household decision making), decreases in the reported acceptability of domestic violence and decreases in reported son preference.

They also find increases in female school enrolment and decreased dropout4 and decreases in fertility (primarily via increased birth spacing). The effects are large, equivalent in some cases to about five years of education, and move gender attitudes of individuals in rural areas much closer to those in urban areas (between 45% and 70% of the difference between rural and urban areas disappeared within two years of cable introduction). Consistent with other work on the effects of media exposure, Jensen and Oster found these changes in attitudes took place very quickly: the average village has cable for only six or seven months before being surveyed again.

There were also increases in male school enrollment and decreases in dropout, but these were smaller.

Jensen and Oster further found the effects of cable were largest in areas with initially more unequal attitudes towards women – that is, those for whom cable is providing information most different from their current way of life.

Although certainly not conclusive, this evidence is consistent with a model in which television changes the weight individuals put on the behaviour of their immediate peer group in forming their attitudes. These changes may reflect the significant differences in gender relations depicted on popular Indian soap operas compared with those typical for rural areas.

Anthropological studies, such as Scrase (2002) and Johnson (2001), found both men and women attributed changing gender relations to the coming of television: they cite Johnson (2001) ‘Since TV has come to our village, women are doing less work than before. They only want to watch TV. So we [men] have to do more work. Many times I help my wife clean the house.”

And they back it up with the better known (at least to me) study from Brazil: La Ferrera, E., Chong, A. and Duryea, S. (2008) ‘Soap Operas and Fertility: Evidence from Brazil’, which finds that the impact of the arrival of TV Globo on women’s fertility is ‘is comparable with that associated with an increase of two years in women’s education.’

So next time someone moans to you about the evils of television……..

October 19, 2014

Links I liked

To lure you away from your Monday morning tasks, we’ll start this roundup of last week’s top @fp2p tweets with some good news

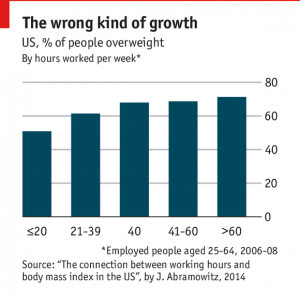

Get a life: a new paper shows that the harder you work, the fatter you get. To which Claire Melamed replied, ‘so if we get lazier we get thinner? win-win!’ (caution, file  under ‘causation v correlation’)

under ‘causation v correlation’)

A hundred Colombian farmers are taking on BP in the UK high court in one of the largest cases in environmental legal history.

And a must read for campaigners: Gandhi’s salt march, building momentum & instrumental v symbolic victories in protest movements

Otherwise, my twitter feed was dominated by two issues – Ebola and Inequality

Ebola

Oxfam launched an emergency appeal and said only the military could move at the speed and scale required to stop the disease from escalating to catastrophic levels.

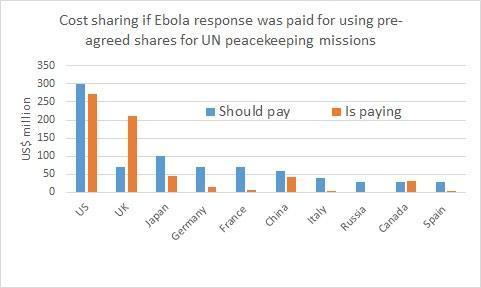

What would fair shares for Ebola funding look like? How does that compare with actual pledges to date? Here’s some calculations by ODI’s Marcus Manuel. Are you listening, Europe?

According to the FT, in the US, the wife of the first victim was left for five days with contaminated material. Meanwhile in Nigeria (now declared Ebola free) they disinfected houses immediately. Anyone else reminded of Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans v Havana?

According to the FT, in the US, the wife of the first victim was left for five days with contaminated material. Meanwhile in Nigeria (now declared Ebola free) they disinfected houses immediately. Anyone else reminded of Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans v Havana?

Probably too soon to be talking about this but the New York Times thinks the disease may come to be seen as a critical juncture both for Jim Kim’s leadership at the World Bank, and sorting out West Africa’s health systems.

Inequality

It was a bumper week for inequality – the theme of Blog Action Day on Thursday and Ricardo Fuentes and the Oxfam research team launched Mind the Gap, a new blog on inequality (and anything else that moves them)

The UK is the only G7 country with rising inequality since 2000. Globally, the richest 1% now has 50% of the world’s total wealth ($263tn)

The Guardian had a good editorial on inequality, the World Bank and IMF and what a genuine end to the Washington Consensus would require

And a brilliant 3 minute videographic on East African inequality. Can we have one for every other region and country please? [h/t Rakesh Rajani]

October 16, 2014

From transactional to transformational: thinking about the future of Social Accountability. Twaweza guest post.

Varja Lipovsek & Ben Taylor of Twaweza, one of my favourite accountability NGOs, read the tea leaves on the future of their field

Varja Lipovsek & Ben Taylor of Twaweza, one of my favourite accountability NGOs, read the tea leaves on the future of their field

In the private rooms of the Royal Society in London, under the stern gaze of Isaac Newton, the World Bank, DFID, ODI and a handful of others gathered recently to discuss an evaluation of the Bank’s Governance Partnership Facility (GPF) and the future of social accountability work within the Bank and beyond.

Social accountability, defined by the Bank, consists of the mechanisms that citizens can use to hold the state to account – such as citizen report cards and participatory budgeting – as well as the opportunities and processes within the state to respond to these mechanisms. For instance, when citizens gather information through a report card on the state of their health centre and formulate a set of requests for improvement, where within the health sector do these requests go? How citizens and governments can better work together is a hot topic right now, from the third anniversary of the Open Government Partnership to how governance should feature in the “post 2015” agenda.

The GPF, a joint project with the governments of the UK, Netherlands, Australia and Norway, was established “to help the World Bank deliver on its commitment to scale up engagement in governance and anti-corruption work in developing countries.”

The short answer provided by the evaluation was devastating: no impact. Nada. Zilch. A number of the Bank’s projects have taken up the governance and social accountability language and frameworks, and engaged in political economy analysis… but there was no difference in effectiveness between GPF-supported and non-supported projects. Ouch.

But does no measurable impact mean no change? The evaluation noted changes within some of the Bank’s programmes – but results had not been seen further down the  line. Perhaps we just have to wait a little longer? This is a defensible argument, so long as there is a reasonable expectation that more of the same will, eventually, lead to substantive change. On this, one critical voice termed the work of the GPF “transactional, not transformational,” articulating two main reasons why no impact has been seen, and why we should be cautious about the future:

line. Perhaps we just have to wait a little longer? This is a defensible argument, so long as there is a reasonable expectation that more of the same will, eventually, lead to substantive change. On this, one critical voice termed the work of the GPF “transactional, not transformational,” articulating two main reasons why no impact has been seen, and why we should be cautious about the future:

The bank’s incentives to spend money were (and remain) too strong, and overwhelmed the GPF agenda.

Leadership structures in the World Bank and DFID were not (and still are not) in place to carry forward the GPF agenda.

The two are related. The core business of the Bank are still its lending operations, and both within the Bank and outside it, there is a sense that it has a pervasive “loan approval culture” that rewards big-ticket projects. Social accountability measures become a secondary consideration. It is this culture that facilitated the transactions within the GPF-informed projects ($22 billion across 125 projects), but precluded any serious changes according to GPF standards. In order to bring about such a significant change, top leadership of the Bank would have to embrace and promote this – in other words, it would have to transform the core business of the Bank.

Moving on to social accountability work more generally, the discussions raised three key challenges.

First, what does success in social accountability look like, and can we measure it? Evidence has been a hot issue in social accountability circles (e.g. here), though it was skirted at the conference. When asked point-blank whether social accountability works, answers ranged from the enthusiastic yes to much greater caution, but with no real discussion of evidence. A relevant question inspired by this debate is around the different levels of success (see here); that is, are social accountability initiatives successful only if they re-align the balance between citizens and state, or can more moderate, perhaps mechanistic, steps also be considered success? And is there necessarily an order to these steps?

Much was said about integrating social accountability inside ‘sector work’ on health, education, infrastructure etc. After all, accountability is usually about something; often, it’s about basic services. Social accountability ought not to be an add-on, but a way of doing core business. On the other hand, it also makes it difficult to know what to track and measure, and how to attribute – if a water programme with social accountability components improves access to water, how do we know whether the social accountability aspect played any role in that success? Perhaps two sets of interlinked indicators are needed – one to measure social accountability, the other on service delivery outcomes.

Much was said about integrating social accountability inside ‘sector work’ on health, education, infrastructure etc. After all, accountability is usually about something; often, it’s about basic services. Social accountability ought not to be an add-on, but a way of doing core business. On the other hand, it also makes it difficult to know what to track and measure, and how to attribute – if a water programme with social accountability components improves access to water, how do we know whether the social accountability aspect played any role in that success? Perhaps two sets of interlinked indicators are needed – one to measure social accountability, the other on service delivery outcomes.

Second, how best to take account of context, power and politics?

Successfully implementing social accountability / governance reforms is incredibly context-specific, requiring a deep understanding of politics, culture, relationships and power structures. Often this is done informally and depends on the political savvy of individual staff; when formalized, it takes the form of Political Economy Analysis (PEA). The Bank, DFID and ODI (twice; this second one is particularly insightful) have documented a good deal of PEA work, which forms a useful set of informative case studies.

In such a complex field, it might be useful to have guiding frameworks, to help navigate the intricacies of each particular context. The World Bank has developed a framework for mapping contextual drivers of social accountability effectiveness. For the moment it’s somewhat abstract, but it has practical potential; a particularly interesting question becomes how to track any changes in the drivers.

Third, isn’t social accountability primarily about the relationship between a government and its citizens?

Many of the conversations framed social accountability as part of the relationship between the Bank and a government, somehow forgetting citizens. Conceptually, the “supply-demand” dichotomy was rejected as polarizing, but several voices were heard arguing that those working on the supply-side of social accountability (i.e. the Bank) can’t be effective in the absence of an articulated demand (i.e. civil society).

There is something muddled and contradictory in this. In recent years the Bank has been at the forefront of articulating why governance matters. At the same time, Bank-funded operations and projects exhibit little or no progress in implementing social accountability. Cynics (though not us of course!) might say that the Bank keeps  its conscience clean by talking the social accountability talk, but has no desire, incentive or serious intention of changing its core business model.

its conscience clean by talking the social accountability talk, but has no desire, incentive or serious intention of changing its core business model.

So what can / should the Bank do? In our opinion, three things:

Use its convening power to establish social accountability as a critical norm in its lending and operations. Set explicit targets by country for the proportion of projects that will incorporate social accountability perspectives.

Promote Right to Information legislation, including concrete details that make any legislation powerful and useful – standards for this have already been developed (see here and here).

Insist on open data on budgets, expenditures and services throughout its work, according to recognised standards of quality data – see here and here.

If we are lucky, such steps could reset incentives and create conditions that will turn the merely “transactional,” into something more “transformational”.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers