Duncan Green's Blog, page 173

January 12, 2015

The Economist on the global spread of cash transfers and Jokowi’s flying start in Indonesia

Some fascinating coverage of the new Indonesian president and cash transfers in the Economist this week. First up, Indonesia:

‘Having trimmed petrol subsidies in November, Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, who is universally known as Jokowi, scrapped them entirely from January 1st. Small subsidies (1,000 rupiah, or eight cents, per litre) will remain in place for diesel, used for public transport and by the country’s millions of fishermen. But for the first time in decades, the price of petrol will reflect global market prices.’

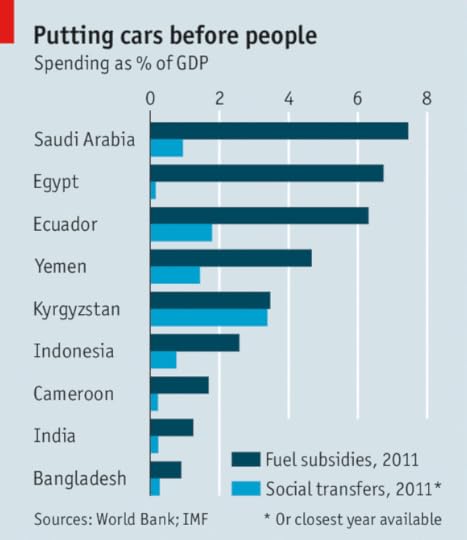

Thinking about this from a theory of change angle, Jokowi seized two brief opportunities – his honeymoon period as a new president, and a slump in global oil prices which allowed him to remove subsidies without prices going through the roof. The move liberates about $16bn a year that previously subsidised the better off at the expense of social transfers (see chart). Another article covers what that cash might be destined for:

‘Barack Obama signed his health-care programme into law 427 days after taking office. Jokowi took just two weeks to begin honouring his health-care and education promises. On November 3rd his government began issuing cards that will give poor Indonesians access to three programmes—two expanding publicly funded health care and education, and one giving cash handouts of 200,000 rupiah ($15.75) per month. The income top-up scheme is planned eventually to cover 86.4m people in 15.5m households—a third of Indonesia’s population. That would make it the largest such programme in the world.’

The shift to cash transfers is part of a wider movement discussed elsewhere in the magazine:

‘Public handouts in developing countries are nothing new: India has had them for decades. But in the past few years their number and coverage has soared. A fifth of all those living in developing countries now receive benefits from at least one programme that aims at alleviating poverty, and Martin Ravallion of Georgetown University estimates that coverage is growing by 3.5% of their combined populations each year. A recent tally by the World Bank found only nine countries without some anti-poverty scheme, whether income-contingent cash payments, subsidies for food or public-work schemes which offer a low wage for manual labour. No-strings cash handouts are catching on quickly in Africa: 37 countries had them in 2013, up from 21 just three years earlier.

Many long-standing programmes are, like India’s, plagued with waste and corruption. But as the developing world weaves its social safety net, better record-keeping and technology hold out the promise of changing that.

Even some very poor countries are starting to build robust records of who gets what. Brazil was a trailblazer: its Bolsa Família (family grant), a stipend for poor families paid on condition that the children are vaccinated and go to school, replaced several smaller schemes in 2003. The register of recipients is published online to help reduce fraud. At least 22 other developing countries now have similar records, and several more are building them, including Bangladesh, Bolivia, Indonesia and Kenya. Such lists cut administrative costs and make it less likely that the same person benefits from overlapping schemes.

Using biometrics as well helps cut fraud. A recent tally by the Centre for Global Development (CGD), a think-tank in Washington, found 230 programmes in over 80 countries that verify identities with biometric information, including voter registries and health records. Some are keeping track of the recipients of social spending. Databases that store fingerprints or iris scans will exclude ghost or dead recipients. Checking such data at disbursement means the right person is paid.

Using biometrics as well helps cut fraud. A recent tally by the Centre for Global Development (CGD), a think-tank in Washington, found 230 programmes in over 80 countries that verify identities with biometric information, including voter registries and health records. Some are keeping track of the recipients of social spending. Databases that store fingerprints or iris scans will exclude ghost or dead recipients. Checking such data at disbursement means the right person is paid.

Nearly two-fifths of South Africans, for example, are enrolled in the national benefits system, which stores fingerprint and voice records for authentication when cash is disbursed. This year India’s biometric ID register should be complete—holding out the hope that its social schemes could be made less leaky. Alan Gelb and Caroline Decker of CGD estimate that switching to biometrics for a typical cash-transfer scheme that gives a million people $20 a month would pay for itself in a year. After five years the savings would reach $64m.

Mobile-payment systems are another ingredient of an efficient, fraud-resistant scheme, since they record what has been paid, make it easier to reach remote areas and can incorporate security checks and reduce the need to transport and store cash. Indonesia is planning to make payments via pre-loaded SIM cards. Other countries, including Nepal, are working on “branchless banking”: roving teams or local vendors equipped with fingerprint-reading devices disburse the cash. Some even announce the amount dispensed to make sure operators do not cheat illiterate users.

But even the best technology can do little to solve a basic problem: deciding who is poor. In the poorest countries few other than government employees appear on any official records of income or wealth. Those scraping a living as street vendors, subsistence farmers, day labourers and so on are unlikely to feature.

So decisions about who should receive benefits often rely on observable proxies for poverty, such as whether someone is old or orphaned, lives in poor-quality housing or lacks consumer goods such as a fridge. Another common approach is to outsource the task of deciding who is destitute to local leaders or community meetings. Research in Indonesia suggests that local scrutiny can work well. But it can also fall victim to corruption or local feuds—especially in communities divided along ethnic or religious lines.

All these difficulties mean that developing countries’ social spending often goes on the wrong people. Between fraud, poor eligibility criteria and patchy data, just a third of beneficiaries are among the poorest fifth in the countries where they live. Some are very well-off.

Some governments are throwing up their hands and leaving it to the poor themselves to step up. They increasingly rely on “ordeal mechanisms”, such as requiring participants to go through a lengthy application process, to discourage the better-off from bothering to apply. Public-works schemes are particularly onerous, since they require recipients to do manual labour. More than 80 countries had these in 2013, a third more than in 2011.

But such schemes also have flaws. The tougher the ordeal, the greater the number of needy candidates who will fail to qualify. Some poor people cannot be spared from household duties for public works; others are illiterate and will struggle with confusing application processes. And though public-works schemes seem to offer good value for money, since they make the poor do something, once administrative costs and the other income forgone by participants are taken into account they look less appealing. A recent study estimates that the money spent on India’s huge public-works scheme would cut poverty more if it was simply divided equally between all rural residents.’

January 11, 2015

Links I Liked

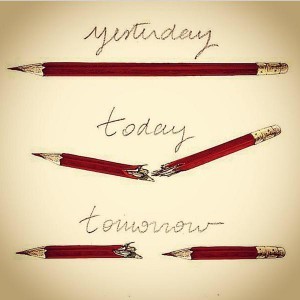

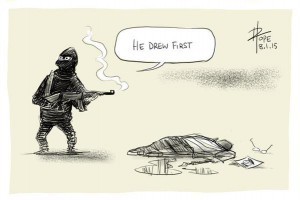

Charlie Hebdo dominated the week. Here’s the best reaction piece I’ve seen so far (h/t Chris

Charlie Hebdo dominated the week. Here’s the best reaction piece I’ve seen so far (h/t Chris Blattman), and my two favourite cartoonist responses.

Blattman), and my two favourite cartoonist responses.

For UK aid wonks: Simon Maxwell summarizes the OECD DAC peer review of Britain’s aid, raising some tough questions for DFID.

Bloomberg Billionaires is tracking the wealth of the megarich. The world’s 200 richest gained $16.5bn in one day last week (yep, you read right). The 10 richest people on earth added $6.6bn You can disaggregate by region, industry, gender etc – lots of fun.

One of the largest ever payouts to a community after environmental damage. Shell accepts $84m deal on Nigeria oil spills.

This is Paul Krugman’s chart of the year – who benefited from global growth 1988-2008, by global income group [h/t William Moseley]

This is Paul Krugman’s chart of the year – who benefited from global growth 1988-2008, by global income group [h/t William Moseley]

Amartya Sen on the case for (& benefits of) universal health care,

The end of Invisible Children (the Kony 2012 lot) and the danger of hollowed-out narratives (h/t Chris Blattman)

In praise of complexity economics – why isn’t it a Bigger Thing?

The weird world of spam king JP Monfort: ‘His prose is circular and nonsensical but coherent enough to pass for an NGO report.’ Now that’s a low bar.

CGD’s new Commitment to Development Index is out, assessing 27 of world’s richest countries. UK at #4 is in amongst the usual Scandiwegians, but how did Portugal make it to number 5? Switzerland, Japan and S Korea bottom of the heap.

January 8, 2015

Why gay rights is a development issue in Africa, and aid agencies should speak up

Hannah Stoddart, on secondment as Oxfam’s advocacy manager in Rwanda, calls for aid agencies to take a stand in defence of beleaguered gay rights  in Africa (and I ask you to vote on her suggestion)

in Africa (and I ask you to vote on her suggestion)

First Gambia, then Chad. Recent months have seen two more countries join the rising tide of State-led homophobia sweeping across the African continent. A bill recently passed in Gambia now means being gay will be greeted with a life sentence. In Chad homosexual relations could cost you up to twenty years in jail. Once the President in Chad ratifies the bill, it will be the 37th country on the continent to have outlawed homosexuality. Such legislation is likely to be followed by increased threats and attacks against gay people – as has been the case in Uganda since the anti-gay law was introduced last year.

The Economist last year ran a cover story on the increasing ‘gay divide’ between countries where there have been great leaps forward in equal rights for gay people, and countries where attitudes towards same-sex relationships are increasingly conservative and intolerant. Many – though not all – countries introducing anti-gay legislation are in the developing world, predominantly in Africa. This poses a particular dilemma for development agencies – whose presence in many countries is authorised by the same States that are preaching homophobia – but whose supporter-base by and large consists of liberal folk in the developed world who find homophobia distasteful.

The question often facing development agencies is whether or not to wade into a controversial debate on a country level, which could aggravate the authorities that give them their license to operate, when promoting gay rights is often not perceived to be ‘mission critical’ to their job – delivering services, running development programmes etc.

True, there are some examples of development agencies supporting the gay cause – for example both Oxfam and Action Aid have publicly condemned the anti-homosexuality law and the murder of gay activists in Uganda. However, public expressions of support are too often caveated with the somewhat bizarre assertion that ‘we are not a gay rights organisation’ – as if gay rights somehow sit in a different category to the other rights we claim to defend. Overall, large international development NGOs remain relatively quiet on the issue and are not prominent among voices condemning growing homophobia in Africa.

That is, at least, until donors have announced aid withdrawals – or threatened them – in response to anti-gay laws. Anecdotally, I have encountered many more debates within the sector on the risks of withdrawing development aid on the basis of anti-gay legislation, than I have on how the development community can best demonstrate solidarity with oppressed gay people. Partly as a result, a quick internet search uncovers as many – if not more – articles condemning this move, as expressions of outrage at the laws that prompted such a response. However fair and important the argument might be – that punishing one group of vulnerable people in the interests of another is not the way to deal with the problem – it has at times felt as if the development community has found the donor response more repugnant than the laws themselves – criminalising or even punishing homosexuality with death – on which it has not been particularly vocal.

That is, at least, until donors have announced aid withdrawals – or threatened them – in response to anti-gay laws. Anecdotally, I have encountered many more debates within the sector on the risks of withdrawing development aid on the basis of anti-gay legislation, than I have on how the development community can best demonstrate solidarity with oppressed gay people. Partly as a result, a quick internet search uncovers as many – if not more – articles condemning this move, as expressions of outrage at the laws that prompted such a response. However fair and important the argument might be – that punishing one group of vulnerable people in the interests of another is not the way to deal with the problem – it has at times felt as if the development community has found the donor response more repugnant than the laws themselves – criminalising or even punishing homosexuality with death – on which it has not been particularly vocal.

This despite the fact that successive progressive commentators in Africa observe that the increasing tide of homophobia across the continent is just one facet of wider attempts to clamp down on freedom of expression and civil society mobilisation more broadly, including women in particular: issues that development agencies have always claimed to hold close to their heart. And that attempts by a State to persecute any vulnerable groups – whether on the basis of gender, race, ethnicity or sexuality– does not bode well for development that is fair and inclusive.

Development agencies have a proud history of recognising the connections between oppression of minorities and crucial development issues – as we have with HIV/AIDS and the gay community in the past. It is crucial now for us to build on these foundations by recognising and publicly condemning the tide of homophobia sweeping across Africa for what it is – an attempt to stifle dissent, to oppress minorities, and to undermine a rights-based approach to development that many of us have spent decades fighting for.

Large development INGOs especially could take advantage of their media reach, public profile and their supporter base, to rally support for gay rights campaigners – brave, courageous people who are often risking their own lives. We could also channel our own funds to support national, regional and international groups and platforms who are fighting for gay rights, and commit to lobbying donor governments to put appropriate pressure on recipient States who are criminalising homosexuality. For the sake of good, fair and equal development, we must speak up.

Interesting, let’s have a vote – see right

January 7, 2015

Them Belly Full (but we hungry): great new study on food riots and food rights

A fascinating new report (with too many co-authors to list, but the invariably interesting Naomi Hossain was principal investigator) summarizes the findings of a four country research project on ‘food rights and food riots’ in Bangladesh, India, Kenya and Mozambique. Some highlights from the Exec Sum:

‘food rights and food riots’ in Bangladesh, India, Kenya and Mozambique. Some highlights from the Exec Sum:

‘The green revolution and the global integration of food markets were supposed to relegate scarcity to the annals of history. So why did thousands of people in dozens of countries take to the streets when world food prices spiked in 2008 and 2011? Are food riots the surest route to securing the right to food in the 21st century?

The core insight of the research is summarised in the title: Them Belly Full (But We Hungry) [which they nicked, with credit, from this 2011 FP2P post]refers to the moral fury aroused by the knowledge that some people are thriving while – or because – others are going hungry. This anger rejects gross inequalities of power and resources as intolerable; it signals that food inequalities have a particularly embodied power – that food is special. Food unites and mobilises people to resist.

[Methodology]: We gained a sense of the scale and type of protests through media content analysis; conducted in-depth work with selected protest movements and communities to explore their motives for and means of organising; and reconstructed the logic of the policy response through interviews with policymakers and practitioners about the events of this time.

[Choice of Countries]: Bangladesh and India share political histories of famine, colonial rule and mass resistance, as well as much in the way of agricultural and food policy. Kenya and Mozambique are relatively poor sub- Saharan African countries with high levels of aid dependence. The international media labelled Bangladesh and Mozambique as sites of food riots during our period, while India and Kenya both featured social movements and civil society activism to establish the right to reporting.

[Global v National]: The politics of provisions work at a country level, but this means they are ‘mis-scaled’ if the problems people face result (as they largely do) from the global food regime. Yet even in the 21st century with its complex global food economy – or perhaps because its governance is so abstract, distant and unknowable – the achievement of food security is a matter of nationhood, reaching back into colonial history, nationalist struggles and the socialisms of the post-colonial period.

[Global v National]: The politics of provisions work at a country level, but this means they are ‘mis-scaled’ if the problems people face result (as they largely do) from the global food regime. Yet even in the 21st century with its complex global food economy – or perhaps because its governance is so abstract, distant and unknowable – the achievement of food security is a matter of nationhood, reaching back into colonial history, nationalist struggles and the socialisms of the post-colonial period.

The global nature of food systems means taking seriously the need for a properly global politics of food. This means a world moral economy, an international right-to-food movement, and a global response to food crises. But there are several challenges here:

What to organise around and for:

A global politics of provisions means internationalising an ideology or moral economy built around nationhood and national affiliation. This has happened to a degree in transnational anti-globalisation struggles such as the food sovereignty movement. But (as this report has tried to avoid showing) an ideological alternative to globalised financial capitalism that is both rooted in local realities and universally resonant risks a normative blandness that will bury the seriousness of the politics in platitude.

Transnational organising around the global food regime is dominated by producer politics, and there is undeniably a delinking of local and national struggles at the food consumption end of the food politics spectrum from the more internationally-networked producer politics. We currently lack a functionally global food

consumer movement, despite the many moves in this direction.

consumer movement, despite the many moves in this direction.Who and what to target :

Conceptualising globalisation to politicise a response; the complexities of global food markets and their abstract, virtual nature renders the target of political protest invisible, moving, unreachable. The practicalities of political organisation are not made impossible by globalisation, but the tried and tested means of the food riot does not easily translate into transnational organising.

Whose behaviour, specifically, needs to change? Global policymakers are generally deaf to the meanings of food riots, unsophisticated in their understandings of domestic politics, insulated from electoral incentives. Global food policymakers need to be able to hear – and fear – food riots; food rioters need to find better ways of making them listen.

How to organise

Protestors need to create political spaces in which rights claims can be made and translated into language that policy elites can understand – as successful shifts in discourse by the UN Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Food demonstrate.

But global policymaking has not always been well supported by civil society organising or by international research. Research on ‘food riots’ has rarely amplified protestor voice, and more usually reduced the understanding of causes to the mechanics of price levels and dynamics. Aid-funded civil society often avoids subsistence protests or food rights campaigning. These are contentious issues, and donor governments are wary of subsistence-related struggles because of their historic association with the left and their unruliness. Aid donors’ usual distance from contentious and unruly politics, as well as their investments in pro-market reforms, help to ensure that they and the civil society groups they fund are distanced from struggles over food policy.

A really key actor is the media: as we have learned from the Indian movement, sympathetic, informed journalism can be the vanguard of a successful food rights struggle

Here’s a six minute video intro to the project

January 6, 2015

Where do the world’s poorest people actually live? Big new databank on multidimensional poverty launched today

Has it ever struck you as pretty bonkers that we usually discuss poverty at national level, equating giant countries like India, with tiny islands whose population would  disappear without trace in a single Indian city? If so, you, along with happy poverty nerds everywhere, should check out today’s Multidimensional Poverty Index from Sabina Alkire and co at the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI).

disappear without trace in a single Indian city? If so, you, along with happy poverty nerds everywhere, should check out today’s Multidimensional Poverty Index from Sabina Alkire and co at the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI).

OPHI has pioneered a new way of measuring the different dimensions of poverty, and then mashing up ten different indicators to get an overall figure (see diagram). This year’s numbers update the figures, and have two other important aspects:

The index now covers 110 developing countries (5.4 billion people), and 803 regions in 72 of these countries. That allows a much finer grained understanding of poverty, both in terms of its variation within countries, and its different nature in different places.

The MPI can be broken down to reveal what percentage of the population are both MPI poor (because they experience multiple deprivations), and are deprived in each particular indicator. For example, the region with the highest rates of people who are multidimensionally poor and simultaneously deprived in nutrition is Affar in Ethiopia, and that with most child mortality is Nord-Ouest in Cote d’Ivoire. Karamoja in Uganda is the most deprived region for sanitation, and Wad Fira in Chad for drinking water, electricity and years of schooling. Androy Madagascar has the highest rates of people who are poor and don’t own any assets, and Kuntuar in Gambia for school attendance.

But the unwanted accolade of the world’s poorest region overall goes to none of these, but to a poverty all rounder instead. In Salamat in south-east Chad, a landlocked region just south of the Sahel, bordering the Central African Republic, nearly 98% of the 354,000 inhabitants are multidimensionally poor.

In terms of inequality, Nigeria is the country with the most extreme regional differences in multidimensional poverty.

The five poorest sub-national regions in different geographical areas are:

Sub-Saharan Africa: Salamat, Hadjer Lamis and Lac in Chad; and Est and Sahel in Burkina Faso.

Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Eastern Turkey; and four areas in Tajikistan: Khatlon, Gorno-Badakhshan, Sughd, and Districts of Republican Subordination.

Arab States: ‘the Capital and all other districts’ of Djibouti; and Missan, Al-Qadisiva and Al-Muthanna in Iraq.

Latin America and Caribbean: Central, Grande-Anse, North-East, Artibonite and North-West – all in Haiti.

East Asia and the Pacific: Oecussi, Ermera, Ainaro and Viqueque in Timor-Leste; and Mondol Kiri/Rattanak Kiri in Cambodia.

South Asia: Bihar and Jharkhand in India; South and West Afghanistan; and Balochistan in Pakistan.

Overall, the findings echo Andy Sumner’s ‘bottom billion’ findings – nearly 60 per cent of people living in the world’s poorest regions are actually not in the least developed countries, but in poor regions within better-off nations.

The report also has some surprising and positive findings on data availability: in 29 of the 30 low income countries that have MPI estimations, data can be disaggregated sub-nationally into 293 regions.

For ubernerds, there’s an interactive databank that allows you to make your own infographics. You’re welcome.

For (relative) normals like me, there are some explanatory infographics about the whole MPI idea, including this one (if you can read it – infographics are getting as busy as bad academic powerpoints).

January 5, 2015

Working With The Grain: an important new book on rethinking approaches to governance

Even though it’s relatively short (223 pages), Working With the Grain (WWTG) took me two months to finish, but I’m glad I did. It adds to a growing and significant body of literature on ‘doing development differently’/’thinking and working politically’ – Matt Andrews, Adrian Leftwich, David Booth, Diana Cammack, Sue Unsworth etc. (Like Matt and Adrian, WWTG author Brian Levy is a white South African – what attracts that particular group to rethinking governance would make an interesting study in itself.)

of literature on ‘doing development differently’/’thinking and working politically’ – Matt Andrews, Adrian Leftwich, David Booth, Diana Cammack, Sue Unsworth etc. (Like Matt and Adrian, WWTG author Brian Levy is a white South African – what attracts that particular group to rethinking governance would make an interesting study in itself.)

Brian summarizes the common elements of this emerging school of thought as:

‘An insistence that the appropriate point of departure for engagement is with the way things actually are on the ground — not some normative vision of how they should be;

A focus on working to solve very specific development problems – moving away from a pre-occupation with longer-term reforms of broader systems and processes, where results are long in coming and hard to discern;

Recognition that no blueprint can adequately capture the complex reality of a specific setting, and thus that implementation must inevitably involve a process of iterative adaptation.’

What makes this book special is Brian’s CV – two decades at the World Bank, which experience he raids to provide great case studies throughout. It feels like he’s now gone back into academia (he teaches at Johns Hopkins and the University of Cape Town) partly to make sense of what he’s learned from 20 years of success and (more often) failure (he characterizes the orthodox governance approach as ‘a breathtaking combination of naivete and amnesia’). Unlike most such tomes, I found it clearer on the ‘so whats’, than the general diagnostic, which tends to get bogged down in endless 3 point lists and typologies (hence the two months).

Levy sees different countries’ development paths as emerging from the interaction of economic growth and institutions. Growth transforms politics by creating a vocal middle class/ business sector. Occasionally, growth and institutions co-evolve, as in the US in the 19th Century. At other times institutions lead (South Africa) or growth leads (South Korea). That raises interesting questions about NGOs’ focus on the masses (social movements, active citizens etc) – does that mean that we both underestimate the importance of the rising middle classes and underplay the politically transformatory impact of growth?

WWTG comes up with one of those 2×2 typologies so beloved of social scientists to describe different regime types along two dimensions of governance – whether their polities are dominant or competitive; within each of these, whether the rules of the game centre around personalized deal-making or the impersonal application of the rule of law. This generates four broad country types:

Dominant discretionary, where strong political leadership (perhaps military, perhaps civilian; perhaps organized around a political party, perhaps a charismatic individual) has successfully consolidated its grip on power, but formal institutions remain weak, so rule is personalized. [examples: Korea under General Park Chung-hee; Ethiopia under Meles Zenawi]

Rule-by-law dominant, where institutions are more impersonal, but political control remains monopolized. [Korea from late-1970s through to its transition to democracy; contemporary China; perhaps Morocco, Jordan etc]

Personalized-competitive, where politics is competitive, but the rules of the game governing both the polity and the economy remain personalized. [Bangladesh, Zambia and many other low-income countries which democratized in the 1990s]

Rule-of-law competitive, where the political and economic rules have become more impersonal – though some other necessary aspects of democratic sustainability have not yet been achieved. [South Africa]

Over time, the key to development is how institutions emerge and evolve in each quadrant, and change the nature of the system.

The table below shows his suggestions for the kind of reforms that might actually ‘work with the grain’ in different regime types. He has a clear preference for incrementalism, especially when a country is on a positive growth path that is likely to generate positive pressures for reform in due course. He is also clearly thinking from the vantage point of a major donor in dialogue with national governments – some substantial rethinking would be required to make this relevant to smaller players like NGOs.

There are some other big plusses, including some great history. Your starter for 10 – which dysfunctional state is being described here? [Answer at the bottom of the post]

There are some other big plusses, including some great history. Your starter for 10 – which dysfunctional state is being described here? [Answer at the bottom of the post]

‘All federal positions were patronage appointments – either made directly by the President, or allocated by him among members of congress to distribute as ‘spoils’. Federal employees had no job tenure; they were removed upon the defeat of their political benefactors. Employees were required to be politically active on behalf of their sponsors, and to contribute 2-10 percent of their salaries to party coffers – else risk losing their job.’

I also liked the honest agonizing and discussion of the dilemmas Levy has faced in his time at the Bank – when is it OK to endorse corruption and/or authoritarianism? How come hopeless political systems like Bangladesh can generate so much social progress? This is all good, grown up, reflexive stuff.

The style is, to be honest, a mixed bag (which itself is a marked improvement on a lot of other governance authors). Sometimes he writes with real verve – ‘‘Advocacy of democracy has been maximalist, shrill, its pendulum swinging repeatedly from euphoria to outrage, with disappointment along the way.’

But then try getting to the end of this paragraph without losing the will to live:

‘In principle, the relevant principals can comprise both governmental and non-governmental actors – although including governmental actors as a co-equal among the principals presumes that, in the context of the specific collaborative endeavor being considered, they have similar standing as co-principals as do non-governmental actors.’

Overall, the book is subtle, complex, often confusing and repays careful study. The complexity is born of deep first hand knowledge, and in the end, suggests that for all Levy’s heroic attempts to distil some general lessons, the roots of success and failure are really only visible with hindsight. Governance advisers and reformers will continue to flounder in the fog, but WWTG, and the other revisionist books and papers, can help a little by discounting some of the bad ideas, and maybe showing people how to look for (and recognize) success a little earlier. That feels like a worthwhile contribution.

More info on the WWTG website. Answer to the Horrible History question: the United States for much of 19th Century

January 4, 2015

How many people? What do they read? 2014′s most popular posts + visitor stats for the year

Had a much less traumatic Christmas than last year (at least until I stepped on the scales) but now it’s back to work, so let’s start with the blog stats and most popular posts of 2014 (I’ll skip the flops). First of all, a huge thanks to all of you who continue to read, comment and link to FP2P (if you stopped coming, Oxfam might force me to do some proper work instead – dreadful thought).

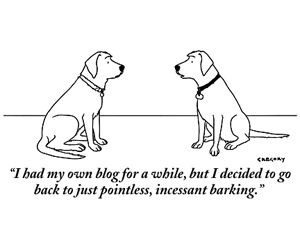

According to the eye of Sauron Google Analytics, there were 297, 857 ‘unique visitors’ in 2014 – defined as ‘Users that have had at least one session within the selected date range’. They read a total of 758,224 pages. That continues a (very) slight upward trend – 282, 408 visitors in 2013, 277,888 in 2012. FP2P began in 2008 and reached this plateau around 2013 (see graph of monthly visitors) – can anyone else confirm that it takes 5 years to establish a blog? Twitter behaves altogether differently, with FP2P followers continuing to grow from 15k to 22k over the year – if you haven’t joined the twitterati yet, you really should, it’s a great source of brain snacks. Twitter now accounts for 40% of referrals to the blog, up from 25% the previous year.

According to the eye of Sauron Google Analytics, there were 297, 857 ‘unique visitors’ in 2014 – defined as ‘Users that have had at least one session within the selected date range’. They read a total of 758,224 pages. That continues a (very) slight upward trend – 282, 408 visitors in 2013, 277,888 in 2012. FP2P began in 2008 and reached this plateau around 2013 (see graph of monthly visitors) – can anyone else confirm that it takes 5 years to establish a blog? Twitter behaves altogether differently, with FP2P followers continuing to grow from 15k to 22k over the year – if you haven’t joined the twitterati yet, you really should, it’s a great source of brain snacks. Twitter now accounts for 40% of referrals to the blog, up from 25% the previous year.

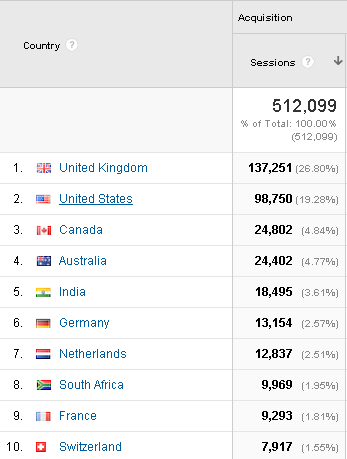

Readers are cosmopolitan, and predominantly northern, with almost half coming from UK and US, but then a big spread for the remainder, all the way down to the single readers from exotic locations such as the Falkland Islands, Svalbard, the Caribbean Netherlands or St Barthelemy (look it up).

As for the most popular posts, two ‘oldies but goodies’ from 2011 topped the charts again, but swopped places compared to 2013, as

The world’s top 100 economies: 53 countries, 34 cities and 13 corporations took over the number one slot from

What Brits say v what they mean – handy de-coding device

The most read post from this year’s crop was much more unexpected:

Somaliland v Somalia: great new paper on an extraordinary ‘natural experiment’ in aid and governance

Next up comes a review of the report that launched the 85 individuals v 3.5bn poorest people killer fact: ‘Working for the Few’: top new report on the links between politics and inequality

Number 5 is a surprise – a review of Joe Hanlon’s controversial book on Zimbabwe’s land reform, posted in January 2013

A draft guide to writing executive summaries got some really useful comments, and came 6th in the number of hits (but sadly, does not seem to have produced a noticeable improvement in the Exec Sums that we are all churning out)

A 2009 post on how climate change is affecting South Africa suddenly got picked up and came 7th

My rave review of Craig Valters’ paper on how theories of change are actually being used by aid peeps came 8th

SocEnt guru Pamela Hartigam’s piece on the overselling of social enterprise raised some eyebrows and came in 9th

And last (and least, but only of the top ten) came further proof of the wonkiness of blog readers – some heretical musings on the limitations of the human rights approach in development

in development

The list overturns some of my previous rules of thumb on what works – most blog posts do indeed die after a few days, but some get picked up (presumably on course reading lists etc) and develop a long tail; pieces on particular countries can do well, provided they illustrate wider points. But one thing doesn’t change – FP2P readers are reliably pointy headed and interested in all that conceptual stuff on theories of change, rights etc etc. A relief, since that is likely to be a major focus for 2015.

Normal service resumes tomorrow. If there’s anything you want more/less of, do let me know – got to keep the numbers up, after all.

December 21, 2014

Links I liked

Bumper crop of tweets last week, and here are some of the best. And with that I’m signing off for Christmas – see you in 2015.

Highest % of children in poverty in the developed world: 1 Greece; 3 Spain; 4 Israel; 6 US; 16 UK; 41 Norway [h/t Conrad Hackett]

Fascinating analysis of the process of change at the IMF – a paradigm shift is under way, away from neoclassical orthodoxy, but it is not complete. The result is growing schizophrenia [h/t Ricardo Fuentes]

Great piece by Ben Ramalingam and John Mitchell on the challenges of the ‘new normal’ in humanitarian work, and a useful typology for responding to them

Fed up with data hypesters? The problem with the data revolution in four Venn diagrams

Take your pick of two reviews of Africa in 2014: for optimists and for pessimists

Must read for inequality peeps: Nancy Birdsall argues that Piketty is largely irrelevant to developing countries (do tell me if she’s wrong)

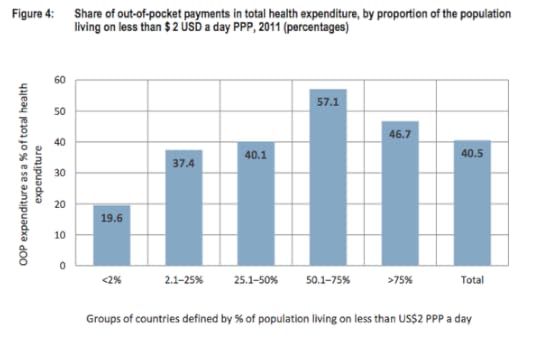

The poorer you are, the more your healthcare spending comes out of your pocket.

Martin Ravallion makes the case for a Basic Income Guarantee (BIG) in developing countries

Totally brilliant (if you ever listen to Radio 4): a day’s R4 broadcasting condensed into 4 wonderful minutes. [h/t Ian Bray]

Dilbert explains strategic planning

Finally, the Guardian crowdsourced 11 of the best aid parodies. Not many new ones, though the oldies are still goodies. But they missed one of my favourites: this wonderful Armando Ianucci sketch - a Kenyan appeal for Britain’s struggling Theatres

December 18, 2014

What are the links between authoritarianism, democracy and development? Magisterial (and short) new overview

Sometimes, with heavy heart, I pick up yet another example of ‘grey literature’ only to find I’ve wandered into an Aladdin’s cave of ideas. That was my sensation on reading Tim Kelsall’s new paper for the Developmental Leadership Program, on ‘Authoritarianism, democracy and development’. In just 14 pages, he summarizes a huge literature, with the aim of boiling it all down into some useful advice for an imaginary governance adviser to a developing country, whether autocratic or democratic or somewhere in between.

Kelsall’s new paper for the Developmental Leadership Program, on ‘Authoritarianism, democracy and development’. In just 14 pages, he summarizes a huge literature, with the aim of boiling it all down into some useful advice for an imaginary governance adviser to a developing country, whether autocratic or democratic or somewhere in between.

In two pages, and truly magisterial style, the paper charts the last 50 years of evolving academic thinking on the issue, as it has veered between a preference (in terms of implications for growth and development) for authoritarian and democratic systems. His conclusion is that the pendulum is currently nicely poised between the two.

He summarizes dozens of cross country studies to try and establish a relationship between regime type and economic development with ‘most have found there to be none’. However

‘On average, there appears to be no growth advantage or disadvantage to being authoritarian. That said, growth under autocracy tends to be more volatile than under democracy, and also to be more extreme. Reflecting this, most of the world’s big growth successes have been autocracies, but also most of its big growth failures (though this may be partly due to the fact that poorly performing democracies tend, before long, to get overthrown by autocrats). When it comes to realizing the MDGs, democracies have a slight advantage overall, and among and constitute a small majority among the extremely good performers. Among the extremely poor performers, autocracies are overrepresented.

If this leaves the relationship between regime type and development rather hazy, the reverse is clearer. At low-income levels, democracy is difficult to sustain, although it has proved possible in some cases. If, however, a minimalist democracy can be consolidated, the chances are that it will do better, developmentally, the more democratic it becomes.’

The paper then reviews the literature on what determines which autocracies fail/succeed and ditto for democracies, covering issues such as existential threats, whether internal or external, that force elites to put development before plunder, and the difference between individual v more institutionalised forms of authoritarian regime (institutionalised ones tend to fare better)

He boils all this down into a set of questions for the adviser. In an authoritarian setting they are:

‘Is the regime facing significant internal or external threats that cannot be assuaged by means of aid and resource rents alone? Does the regime have a credible development policy, focused on small-scale agriculture, or otherwise well-suited to existing factor endowments and their dynamic potential? Is the leadership embedded in a strong, institutionalized party, military, or bureaucracy? Does the leadership enjoy good enforcement and implementation capacity, thanks to its ability to take the long view and to prevail in rent-seeking contests? Has it solved some informational and coordination problems through appropriate state-business institutions?

If the answer to all these questions is ‘yes’, the regime would appear to have the political will to develop, and the policies and the institutions to do so.’

In a democratic setting, the questions become:

‘Is this a country in which all or almost all powerful elite groups have a commitment to democracy, either because they have been through a long period of democratic tutelage, or because they see democracy as the best means of resolving conflicts and maintaining at least some of their privileges? And are the popular forces in favour of democracy sufficiently strong and well-organised to ensure that democratic concessions are not merely cosmetic?

If the answer to these questions is ‘Yes’, democracy may be a viable alternative to authoritarian rule. And will it be a developmental democracy? Here, the same kinds of questions we asked of authoritarian states are likely to apply. Does the regime face an internal threat that cannot be averted by distributing unproductive rents? Does the regime have good policies? Does it have an effective implementation and enforcement capacity?

If the answer to most of these questions is ‘no’, there may be little point in our policymaker trying to encourage a democratic transition.’

Overall, it’s both a great summary of the literature, and a fascinating thought experiment of what a policy adviser might ask/say if they set aside their own assumptions about what works, or those of the donor government that employs them.

And here’s it all reduced to a doubtless over-simplified decision tree – hope you can read it.

December 17, 2014

$2 leaving developing countries for every $1 going in – big new report on the state of global financial flows

A very useful new report from Eurodad, published today, provides ‘the most comprehensive review of the quantity of different financing sources available to developing  countries, and how they have changed over the past decade.’ This in the run up to the big UN summit on financing for development (FfD) in Addis Ababa in July 2015.

countries, and how they have changed over the past decade.’ This in the run up to the big UN summit on financing for development (FfD) in Addis Ababa in July 2015.

Here are some highlights from the exec sum:

‘We have analysed the best available data produced by international institutions, both from the point of view of developing countries as a whole, and for low-income (LICs), lower-middle-income (LMIC) and upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) separately. Unlike other recent analyses, we have not just examined the resources flowing into developing countries, but have also analysed the resources flowing out, identifying the lost resources.

We examine four very different categories of resources:

Domestic resources, including domestic investment and government revenue;

Lost resources, including illicit financial flows, profits taken out by foreign investors, interest payments on foreign debt and lending by developing countries to rich countries.

Inflows of external resources, including international public resources (aid and other official flows), for-profit private flows (foreign direct investment and portfolio investments in stocks and shares) and not-for-profit private flows (including charitable flows and remittances from migrant workers);

Debt creating flows, both public and private borrowing by developing countries.

One key finding of the report is that losses of financial resources by developing countries have been more than double the inflows of new financial resources since the financial crisis.

Lost resources have been close to or above 10% of GDP for developing countries as a whole since 2008. The main drivers of this are illicit financial flows, profits taken out by foreign investors and lending by developing countries to rich countries. [more on illicit flows, which are increasing much faster than global GDP, here]

Our main findings for each category of resource are as follows:

Domestic resources: Domestic resources are far larger than all external financing sources for developing countries, with domestic investment reaching over 33% of GDP and government revenue over 18% in 2012. UMICs have reached $2,700 per capita domestic investment annually, while LICs manage only $165 per capita.

There are low levels of public investment in LICs – 3.5% of GDP in 2011, compared to over 9% in LMICs.

Losses of domestic resources.

Outflows of domestic resources represent major losses for developing countries, and have been running at double the inflows of new resources since 2008, as Figure 1 shows.

LICs are particularly badly affected, losing more than 17% of GDP in 2012.

The largest outflows were illicit financial flows ($634 billion in 2011) and profits repatriated by international investors ($486 billion in 2012).

In 2012, developing countries lent $276 billion to rich countries, and paid $188 billion in interest on external debts.

Since 2010, repatriated profits have exceeded new inflows of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), with LICs particularly affected, with outflows of over 8% of GDP.

International public resources:

Country programmable aid (CPA) levels, while increasing in absolute terms to a high of $96 billion in 2011, have been falling relative to developing country GDP, which has been growing at a faster rate.

In LICs, however, aid remains an important resource, with CPA accounting for over 7% of GDP in 2012.

International for-profit private flows

FDI to developing countries was badly hit by the global crisis and remains below its 2008 peak. Rising GDP means it has fallen as a percentage of GDP from 3.2% in 2008 to 2.1% in 2012.

LICs, however, have had steadily increasing amounts of FDI compared to GDP, rising from 2.6% in 2003 to 5.1% in 2012, driven by a small number of countries.

For-profit flows can be highly volatile, particularly portfolio equity flows of stocks and shares, which rose sharply for developing countries before the global financial crisis drove them into negative figures in 2008.

International not-for-profit flows

Remittances from private emigrants to their families back home increased from just over $130 billion in 2003 to more than $350 billion in 2012, although this figure may be due to improvements in data collection.

Remittances are particularly important in LICS and LMICs; they represented 7% of GDP in LICs and 4.6% in LMICs in 2012. They are highly concentrated in a small number of countries.

Debt-creating flows

Since 2006, there has been a sharp increase in new debt taken on by developing countries, driven by LMICs and UMICs.

Developing country debt stocks reached their highest level ever in 2012 – $4.8 trillion, according to the World Bank – which was largely driven by increases in indebtedness by private actors.

LIC governments have remained heavy net borrowers throughout the period, averaging between 1.3% and 2% of GDP in additional long-term borrowing between 2003 and 2012.

And here’s the killer infographic

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers