Duncan Green's Blog, page 174

December 16, 2014

Local First: an excellent (and practical) counterweight to the more top-down versions of ‘doing development differently’

I’ve been both engaged and excited by a lot of the recent networking on ‘thinking and working politically’/’doing development differently’, which emphasizes the importance of understanding and working with the grain of local context, and a project cycle which replaces ‘The Plan’ with a messy process of trying, failing, learning and adapting (and trying again). But one anxiety I have is that it all feels very top down – clever political scientists, often working for big aid agencies, getting better at driving reforms through recalcitrant governments. The risk is that issues of power, rights and justice too easily get lost in the fascinating discussion of nuts and bolts, what works etc and (for example) we end up helping gove rnments that routinely kill or suppress their opponents ‘deliver development’.

rnments that routinely kill or suppress their opponents ‘deliver development’.

So I gave thanks when I read ‘Local First in Practice’ a new book (and separate summary) by Rosie Pinnington of Peace Direct, which describes itself as ‘an international agency that finds, funds and promotes the work of local peacebuilders in conflict zones worldwide’.

The book sets out a process of barefoot ‘doing development differently’ from the bottom up, providing an important counterweight to more top down approaches. And it’s not just a lot of NGO waffle about the need for participation – it’s stuffed full of good practical examples. It also highlights the importance of basing any intervention on the strengths and assets of the local community, rather than sending in outside ‘experts’ to identify gaps and then trying to fill them.

It covers a series of themes, with a set of practical recommendations on each:

Identifying and supporting local capacity

Listening to local voices to develop responses and approaches

Using funding mechanisms that enable rather than distort local entities

Supporting local actors to work together to achieve greater impact

It then distils these into a set of ‘good practice principles’ and key recommendations which are worth reproducing in full:

Good Practice Principles:

1. Listening: design and adjust according to locally-felt concerns and shifts in the local context; listen to and act upon information and feedback received.

2. Harnessing and deploying latent capabilities: before identifying gaps and needs, look at what already exists in terms of local resources and capabilities, and how they can be supported.

3. Providing support in a timely and responsive way: use small-grant mechanisms to respond to opportunities as they arise and to react to particular events; provide capacity support that is driven by local realities and priorities.

4. Promoting participation: in all stages (research, planning, implementation, monitoring), facilitate participation that empowers local actors to influence and drive processes of change in their societies. Participation can also promote accountability.

5. Recognising that change is a process: rather than leading, facilitate progressive, cumulative change over time; be open to testing, learning and developing through long-term engagement and repeated cycles of action.

Small fish matter too

6. Broadening the definition of success: balance the prioritisation of results to include both tangible and less tangible aims (such as changes in attitudes and behaviours).

Key Recommendations:

1. Move away from big aid to small, targeted and strategic funding. An approach of this kind could range from core funding (to help an organisation develop on its own terms) to activity-based allocations (to help local actors respond to specific opportunities or changes in their environment).

2. Nurture more beneficent and flexible bureaucratic environments. This could be as simple as ensuring that grant managers are available to talk to grantees over the phone as an informal feedback and monitoring approach.

3. Create space for ideas and new approaches to be tested and developed. This is connected to: having faith in the ideas of local partners; creating space for local actors to shape the design of programmes; and conceding that change is a cumulative process where learning through mistakes is as important as achieving successes.

4. Develop shared approaches for measuring ‘intangible’ aims and outcomes.

5. Develop staff performance metrics that encourage locally led practice.

6. Remove pressure to spend and stringent ‘value for money’ cultures in aid bureaucracies.

This strikes me as a really excellent summary of a bottom-up approach to thinking and working politically. But I live in meta-land, an awful long way from anything resembling a field. So is this all old hat, old wine in a new TWP bottle, or something really worth picking up and running with? And what’s missing?

December 15, 2014

The new World Development Report (on mind, society and behavior): lots to like, but a big fail on power, politics and religion

This probably doesn’t need saying, but the World Development Report is a big deal. The World Bank’s annual flagships have a track record of shaping debates on  particular issues, and raising them up the endlessly churning development agenda. So it pays to pay attention.

particular issues, and raising them up the endlessly churning development agenda. So it pays to pay attention.

This year’s WDR, published this month, is on ‘Mind, Society and Behaviour’. I (like most people) have only read the 20 page overview, not the tome on which it is based, (but if I miss anything, that’s the Bank’s fault for not including it where it matters!).

So what does it say? Drawing heavily on the work of Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow) and Richard Thaler and Cass Sunsteain (Nudge), the report pulls together a pretty seismic challenge to business/economics-as-usual:

‘Paying attention to how humans think (the processes of mind) and how history and context shape thinking (the influence of society) can improve the design and implementation of development policies and interventions that target human choice and action (behavior). To put it differently, development policy is due for its own redesign based on careful consideration of human factors.’

The report sets out the kinds of questions it thinks behavioural economics can help with:

‘Can simplifying the enrollment process for financial aid increase participation? Can changing the timing of fertilizer purchases to coincide with harvest earnings increase the rate of use? Can providing a role model change a person’s opinion of what is possible in life and what is “right” for a society? Can marketing a social norm of safe driving reduce accident rates? Can providing information about the energy consumption of neighbors induce individuals to conserve? As this Report will argue, the answers provided by new insights into human factors in cognition and decision making are a resounding yes.’

The underlying purpose is to ‘help people make better decisions.’

Here’s the report’s Co-Director, Varun Guari, summarizing it all in 2.5 minutes

From its survey of the literature (and a treasure trove of case studies) the WDR identifies three principles:

‘First, people make most judgments and most choices automatically, not deliberatively: we call this “thinking automatically.” Second, how people act and think often depends on what others around them do and think: we call this “thinking socially.” Third, individuals in a given society share a common perspective on making sense of the world around them and understanding themselves: we call this “thinking with mental models.”

These principles, in passing, highlight the importance of targeting social norms (something I’m increasingly focusing on) and add one very large nail to the coffin of rational expectations/homo economicus – the assumed genius number cruncher at the heart of much of neoclassical economics. It turns out that in real life, people do not spend hours processing all available information before deciding whether to buy bread or coca cola. Well duh.

A lot of the conclusions echo the kinds of thinking going on in the Doing Development Differently and Thinking and Working Politically networks:

Small bets and multiple experiments: ‘development practice requires an iterative process of discovery and learning, which in turn implies spreading resources (time, money, and expertise) over several cycles of design, implementation, and evaluation.’ (see the diagram for a new improved project cycle)

Power Within and Strengths-based approaches: ‘invoking positive identities can counteract stereotypes and raise aspirations. Having individuals contemplate their own strengths has led to higher academic achievement among at-risk minorities in the United States, to greater interest in antipoverty programs among poor people, and to an increase in the probability of finding a job among the unemployed in the United Kingdom.’

Power Within and Strengths-based approaches: ‘invoking positive identities can counteract stereotypes and raise aspirations. Having individuals contemplate their own strengths has led to higher academic achievement among at-risk minorities in the United States, to greater interest in antipoverty programs among poor people, and to an increase in the probability of finding a job among the unemployed in the United Kingdom.’

A critique of the power and prejudices of aid professionals: ‘Although 42 percent of Bank staff predicted that most poor people in Nairobi, Kenya, would agree with the statement that “vaccines are risky because they can cause sterilization,” only 11 percent of the poor people sampled actually agreed with the statement. This finding suggests that development professionals may assume that poor individuals may be less autonomous, less responsible, less hopeful, and less knowledgeable than they in fact are. Beliefs like these about the context of poverty shape policy choices. It is important to check mental models of poverty against reality.’

All thoroughly excellent and engrossing, but as I read through the overview, I could feel alarm bells clanging ever-louder. The Nudge authors were quite open that what they were suggesting was ‘benign paternalism’ – governments getting better at manipulating people’s choices for their own good. The report has that same flavour – for all its talk of human fallibility, the underlying assumption is still that ‘we’ know best (if you don’t believe me, listen to the video again). In the overall purpose of ‘helping people make better decisions’, there is no suggestion that someone other than technocrats should be defining what constitutes ‘better’.

That seems to lead to a focus on tweaks rather than transformation – shades of The Leopard and ‘everything must change so that everything can stay the same’ – look again at that list of questions the report seeks to answer – they’re important but hardly earth-shaking.

And what if the behaviour-shapers are not benign? There is no acknowledgement of the potential Orwellian dark side of new improved behavioural manipulation – using stigma to blame individuals for systemic problems, or an external enemy to generate patriotic support for a repressive government.

And there is no acknowledgement of the importance of power and politics in (mis)shaping ‘mind, society and behaviour’: here are some of the words that returned a zero count on a wordsearch of the 20 page overview text (excluding references): Power, politics, religion, faith, gender, women. Sorry, there was one reference to women. Read that list again, and ask yourselves how you can write a massive study of ‘mind, society and behaviour’ that ignores all of them.

And I fear the WDR has form on this – take a development issue that is dripping with power, politics and struggle, then technocratize it into a set of best practice guidelines for tweaks-not-transformation in an often-imaginary world of benign decision makers. Sorry, not good enough.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t read it – just be aware of what is missing, as well as what is in there.

And here’s Ben Ramalingam’s rave review, Martin Wolf in the FT and the inevitable summary infographic.

December 14, 2014

Links I liked

This week’s selection from last week’s @fp2p twitter traffic

Relative girls & boys school enrolment worldwide. Red = more boys; Blue = more girls; Yellow = about equal. It’s getting complicated, people [h/t Conrad Hackett]

The Harvard business school professor v the Chinese takeaway. Bonkers. [h/t Aditya Chakrabortty]

Let’s talk governance and institutions:

The recent Harvard meeting on ‘Doing Development Differently’ continues to generate interesting content. The DDD crew has set up a new website for positive deviants, next stop world domination. ODI’s Craig Valters had a sensible piece on the overlap/synergies with theories of change

Staying with governance and institutions, ‘time for a grown-up conversation about corruption’ from Alina Rocha Menocal has an excellent overview of a much avoided topic.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the aid jungle

Does aid work? Moving on from ‘oh yes it does’; ‘oh no it doesn’t’ pantomime, however seasonal, Andy Sumner and Jonathan Glennie have a useful literature review on the $138.5bn question

Community mental health workers: are they a possible answer to the mother of all cinderella issues in development – depression?

The worst charity ads of 2014, won by this remarkably tin eared example from South Africa. According to the charity’s CEO “Like a child, I don’t see race or politics.” Um, right. (The other candidates are also disturbing, in a variety of ways)

And finally, a little Christmas nepotism: Another cracking short film on girls’ empowerment from my sister-in-law Mary Matheson at Plan International. Girls around the world using Malala Yousafzai’s words to campaign for education. If (like me) you’re prone to bubbling, you’ll need a hankie……

December 11, 2014

The Living Wage: a remarkable story of global progress – how big could it get?

A few years ago, I was struck by the fervour with which a student activist acquaintance of mine, Stefan Baskerville, talked about the Living Wage. Every holiday he  would leave his life of student activism (and occasional study) in Oxford and head for the East End of London, where he worked for Citizens UK, a community organization, in a campaign to get the LW for the cleaners and other low-paid employees in the City (London’s financial district). Years on, he’s still at it, and his efforts and those of thousands of other activists are starting to bear fruit, both in the UK and the developing world.

would leave his life of student activism (and occasional study) in Oxford and head for the East End of London, where he worked for Citizens UK, a community organization, in a campaign to get the LW for the cleaners and other low-paid employees in the City (London’s financial district). Years on, he’s still at it, and his efforts and those of thousands of other activists are starting to bear fruit, both in the UK and the developing world.

This week Oxfam published a report on ‘Steps towards a Living Wage in global supply chains’, which provides an intriguing account of progress to date. The Living Wage is not a new idea – in 1919 the ILO argued that ‘Peace and harmony in the world requires an adequate living wage’. But until recently, the action was all elsewhere – freedom of association, collective bargaining, child labour, health and safety, payment of the minimum wage set by government, but not based on what a family needs to live decently (the distinction with the LW).

But in the last few years, the living wage concept has started to get traction:

The grassroots-based Asia Floor Wage campaign took the debate up a level, when a group of Asian unions and NGOs proposed a formula for the LW and published benchmarks for Asian countries covering 80% of global garment production. Western campaigners got behind them.

Multi-stakeholder initiative Fairwear Foundation nudged its corporate members to go ‘beyond audit’ and to remove barriers to a living wage. It has developed Wage Ladders (which include benchmarks from local trade unions) which help members set improvement targets, and instituted a Performance Benchmarking System which rewards action and penalizes inaction.

Early steps in the right direction were taken by Inditex, which signed an International Framework Agreement with the garment union in 2007 (re-affirmed in 2014) and Marks & Spencer which included in its 2010 corporate plan a commitment to pay a price that enabled a ‘fair living wage’ to be paid in Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka.

Early steps in the right direction were taken by Inditex, which signed an International Framework Agreement with the garment union in 2007 (re-affirmed in 2014) and Marks & Spencer which included in its 2010 corporate plan a commitment to pay a price that enabled a ‘fair living wage’ to be paid in Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka.

Impactt’s Benefits for Business and Workers programme set out with eight brands and 73 factories supplying them to develop a virtuous circle of improvements, proving a business case for paying better wages in terms of improved productivity and staff retention.

In the food sector, Unilever replaced its traditional supplier code with a Responsible Sourcing Policy based on a continuous improvement framework covering mandatory requirements, good practice and best practice standards. It has published targets for 200 ‘Partner to Win’ suppliers and 1,000 strategic partners (11,200 sites in all) to achieve ‘good practice’ standards by 2017; these include a ‘living wage approach to fair compensation’.

Nestlé became the first major food manufacturer in the UK to become an accredited Living Wage employer in 2014.

In November 2014, Tesco became the first retailer to announce that it would pay a living wage to banana workers in key sourcing sites by 2017.

In September 2014 following months of unrest eight brands wrote an open letter to the Cambodian government and industry association stating their readiness to factor higher wages into their pricing. In November the government raised the minimum wage by 28%.

As for the UK, for Stefan and his fellow campaigners at the Living Wage Foundation have made remarkable progress: In 2011 only two of the top 100 UK companies were living wage employers; now there are 19, with 10 more in the pipeline and over 1000 accredited employers in total, including Oxfam GB. While the numbers benefitting are still relatively small – 60,000 against over five million paid below the living wage – the initiative has helped normalize discussions in the business community and in the UK provides a ‘bridgehead of principle’ to action in global supply chains.

How did this change come about? The briefing identifies several factors:

The steady global decline of wages as a percentage of GDP has created a general sense that the system is both unfair and increasingly unstable

A passionate and sustained grassroots campaign by unions and grassroots organizers like Stefan

Solid research and accumulating experience (often through multi-stakeholder initiatives like the Ethical Trading Initiative) on how to actually introduce the LW in modern supply chains

The galvanizing power of disasters – in particular the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh, which killed over 1,100 people. In the words of C&A’s Philip Chamberlain ‘We must use the energy [generated by Rana Plaza] to approach this issue in a different way from the past.’ Since Rana Plaza, 14 garment companies sourcing from Bangladesh have signed up to four enabling principles for a living wage.

But before we go all Kumbaya about it, the report sensibly urges caution: ‘Very little has changed for very few workers. To achieve a tipping point, a more systemic approach is needed.’ As Jenny Holdcroft of the international union, IndustriALL says

‘If you carry on tweaking business as usual and finding nice examples to follow we’ll still be here in 20 years holding the same conversation.’

But still, the progress is remarkable – it’s hard to think of a more fundamental shift than that from allowing markets/ Darwinian supply and demand to set wages, to deciding on the basis of workers and their families need to live decent lives. The best way to eradicate poverty is surely to pay people properly.

The report is full of other examples and guidance for those wishing to promote the Living Wage – I urge you to take a look.

More from the briefing’s author, Rachel Wilshaw, here.

December 10, 2014

How can small countries make a difference with their aid programmes?

Had a fun couple of days in Malta last week – amazing place, dripping with history – massive battlements, the Knights of Malta (right), amazing blinged-up churches, and some

The knights didn’t last long

spectacular Caravaggios (my favourite one below). I was there to deliver a Kapuscinski Lecture on ‘Citizen Empowerment and Mobilization’ – I’ll link to it when it goes online. But I also had a fascinating conversation on the role of small aid donors.

Historically, Malta has always been on the receiving end of aid. When it joined the EU in 2004, one of the requirements was for it to become a donor and develop an aid policy. So it went almost overnight from aid recipient to aid donor. But it is a small country (400,000 people), and its aid budget is currently only €14m ($17m, 0.2% of its Gross National Income). How does it spend it?

The answer is, not very well, at least according to the latest AidWatch report. AidWatch discounts €8m of the €14m as ‘inflated’ because it is spent on refugee detention centres – Malta is slap bang on the migration route between North Africa and Europe.

But when I read the Maltese government’s aid policy (which doesn’t appear to be on the web), I started to wonder whether AidWatch is right. Malta’s current policy reads like an exercise in wannabe aid donorship. It sets out 10 ‘areas of focus’, from good governance to health to gender equality to climate change. What is the point of an aid minnow trying to be a mini-me DFID (whose aid budget is over 1000 times larger)? What might be a better starting point for a relevant aid policy?

That got me thinking of a couple of recent conversations on the ‘Strengths Based Approach’ to development. What is special about Malta that could form the basis of a useful aid policy? Two aspects in particular stand out: one is precisely its role as a migration hotspot; the other is religion – Malta is a deeply Catholic country, with a long missionary tradition. Maltese citizens actually give far more in their private charitable giving than the government does through its official aid budget.

What would an aid policy build around those strengths look like? Malta could develop a migration policy that combines migrant rights with more humane deterrence (there must be a better way to deter migrants than simply letting them drown). It could lobby the EU and its member states on the need to boost public education and awareness on migration. It link up with other migration hotspots. It could research the vulnerabilities and potential protection of migrants on their long and vulnerable passage from home villages in North Africa and the Middle East to the shores and detention camps of Europe.

On faith and development, it could focus its aid work on improving the quality of faith-based aid, promoting inter-faith dialogue and challenging Europe’s secular aid ethos.

St Jerome writing: Caravaggio from his Maltese period

But that is unlikely to happen. Instead, its aid programme is an exercise in magical thinking – in Matt Andrews’ phrase, ‘isomorphic mimicry’ of a large, secular aid donor.

This is partly because of the lack of a generalised system of support for new members from the EU. Androulla Kaminara, a thoughtful adviser to EuropeAid explained how it works. Prior to accession, the EU can exert pressure on candidate countries to introduce conventional aid policies, but the moment a country joins, it has to be treated as the equal of all other members. But it is bonkers to think Malta suddenly acquires an effective state aid apparatus just by becoming a member state – it has just six aid officials, and local NGOs complain bitterly about the lack of transparency and consultation. There is no transitional category of new EU states in the European Commission, which instead can only respond to requests from member states. If they are too weak to even ask for help, or do not see aid as worth investing in, then nothing happens. Which is pretty much the story in Malta.

So it’s hardly surprising that the research finds a fairly dismal performance by new member states in general. Reluctant Donors? The Europeanization of International Development Policies in the New Member States, by Simon Lightfoot and Balázs Szent-Iványi, looked at aid policies in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. They found that countries have done the bare minimum on aid to comply with accession requirements, have failed to build a domestic constituency for the transition from aid recipient to donor, and have had very little support or pressure from Brussels.

NGO thinking, as epitomised in the AidWatch report, doesn’t help much either. The Maltese NGOs I talked to saw only problems (not potential strengths) in working on either migration or faith – they want a standard secular aid programme, with lots of participation and consultation.

Thinking about an alternative, strength-based, approach fits with some of the institutional reform thinking of the ‘Doing Development Differently’ crowd – for example

Migrant detention centre, Malta

developing hybrid aid institutions out of what is already there, rather than implanting an illusory aid policy based on the World Bank or the MDGs. But it made me question Matt Andrews’ ‘problem-driven iterative adaptation’ (PDIA) approach to institutional reform. PDIA could identify lots of problems with Malta’s aid programme, but would not naturally lead you to build on its existing strengths. Is that a wider flaw of PDIA? Maybe we need a combo ‘Strength Based Iterative Adaptation’ variant? Interested in your thoughts on that.

December 9, 2014

You can’t take a supertanker white-water rafting: what future for International NGOs?

This post also appears on the ‘Practice for Change’ blog

I try to avoid those endless bouts of INGO navel gazing, but don’t always succeed. Which is lucky, because recently, I had a really interesting session on ‘the future of

The Golden Age or a bunch of hippies in a zoo?

INGOs’ at La Trobe University’s Institute for Human Security and Social Change in Melbourne.

I kicked off summarising a recent paper (The End of the Golden Age of NGOs) by my host, Chris Roche & exfam CEO Andrew Hewett. In it they ask if INGOs are coming to the end of their ‘Golden Age’, subject to a swelling chorus of criticism that the secret of their success also contains the seeds of their downfall:

Building public trust by telling on oversimplified story that ‘aid will make poverty history’

Squeezing out more legitimate, representative voices from the South

Getting too close to northern governments, especially through funding arrangements, but also by wanting to keep access to decision makers

Too big, ineffective and bureaucratic

Being by-passed by more nimble ‘start-ups’

Trends in development have thrown up a series of challenges to this Golden Age model:

Mass poverty is giving way to pockets of chronic poverty in most countries

Otherwise, fragile and conflict states are becoming the final, most difficult terrain for ending world poverty

The issues that affect developing countries are increasingly global (climate change) and/or shared (inequality, tobacco, obesity)

Citizen action is rising, but the political space for that action is shrinking.

The aid business is in a weird eeyorish mood. Although global aid volumes have bucked the historical trend and have not (yet) slumped after the global financial crisis, aid is under unprecedented question and self doubt is prevalent. Responses have included a much greater focus on results and value for money, and a high degree of ‘private sector fetishism’ (‘states are rubbish, aid agencies are rubbish, send in the private sector!’)

INGOs are currently responding in various ways: defending aid quantities; trying to decentralise to the South, both in terms of their programmes, but also their internal governance. There has been a rise in multi-stakeholder approaches, seeking to work with states, private sector and others, rather than go it alone. And I detect a growing divide between a service delivery and advocacy approach (are we about shifting policies, narratives and norms or delivering vaccines and bednets? Sure, everyone will answer ‘both’, but the relative emphasis varies over time and between INGOs).

What’s more, the very category of ‘INGO’ is acquiring some blurred boundaries. Are southern INGOs like BRAC International a fundamentally different beast? Where do social enterprises, impact investors and the big philanthropists fit?

Typical INGO brainstorm

So what does the future hold?

On shared problems, either we are all in this together, eg on tackling inequality, or in areas where traditionally northern problems are heading south (obesity, non communicable diseases, road deaths), aid agencies (both government and NGOs) could become signposters and networkers, rather than acting in their own right. Want to tackle road traffic carnage? Here’s the email for Britain’s road safety experts, and funding for an exchange programme.

CGD’s emphasis on advocacy around the North’s impact on development (climate change, migration, tax, aid quality) rather than lecturing developing countries, is always attractive, and won’t go away.

In the South, there is a greater focus on the role of state, building up and supporting national expertise and autonomy, and then INGOs supporting with their external links to donors, media and multilateral organisations, as well as technical expertise, where it is missing.

Always-painful efforts to increase flexibility and adaptation, introduce systems approaches etc, leading to widespread Innovation Tourettes.

But then we got on to the issue of size. The default measure of success in most INGOs is ‘are we growing?’ If income falls, it triggers painful bouts of restructuring and a general sense of malaise. But the focus on size sits uncomfortably with all that blah about being innovative and agile – as Chris Roche put it ‘you can’t take a supertanker white-water rafting’. So to my joy, we came up with every policy wonk’s favourite – a 2×2, with small v big, and advocacy v social delivery as the two axes.

Small

Big

Advocacy

Guerrilla warriors like Global Witness

Incubators that get picked up by governments and big INGOs (eg Publish What You Pay giving rise to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative)

Conventional advocacy steamrollers like Greenpeace or Oxfam (on a good day)

Big single issue coalitions, like Robin Hood Tax, or Jubilee 2000

Service Delivery

Incubators that get picked up by governments and big INGOs (examples?)

Disintermediated cash transfers (GiveDirectly)

Social Enterprises

Providing services where states aren’t up the job (faith organizations, Save, Care)

Humanitarian Emergencies

Big Philanthropic Foundations (Gates, CIFF)

As with any typology, people are probably going to protest at the grotesque oversimplification and disagree both with the categories and their allotted box – ‘we’re in all four!’ But I’d be interested in your comments, examples and whether this leads to any implications for the evolutionary path of INGOs.

And here’s some actual white water rafting on the Nile in Uganda, in memory of the worst afternoon of my life (when I discovered I really don’t like adrenaline). Thanks to Savio Carvalho for suggesting I go……

December 8, 2014

Did Britain’s Aid Programme (and maybe aid in general) just get its Mojo back?

[Mojo: NOUN (plural mojos), chiefly US: A magic charm, talisman, or spell]

I got back from Malta on Friday, just in time to watch the end of the House of Commons debate on enshrining in British law the longstanding, but widely ignored,

international commitment to spend 0.7% of Gross National Income on international development. By an overwhelming majority (146 to 5), the bill passed. It still has to go to the House of Lords, but it looks pretty certain that it will become law.

international commitment to spend 0.7% of Gross National Income on international development. By an overwhelming majority (146 to 5), the bill passed. It still has to go to the House of Lords, but it looks pretty certain that it will become law.

In political terms, this is extraordinary. When governments around the world are cutting aid budgets and abolishing aid departments, and at a time of widespread austerity hitting nearly all other functions of government, the Brits have become not only the first G8 country to reach 0.7, but also the first to fix it in law. It doesn’t make it impossible for a future government to do a U turn, but it massively increases the political costs and obstacles to doing so.

Why did it happen? There has long been a striking level of cross party leadership and consensus on aid in the UK. Labour set up DFID as a cabinet level department, with Gordon Brown and Tony Blair investing serious political capital at Gleneagles and elsewhere. David Cameron and George Osborne have been firm in their support for aid and the 0.7 target. The private members’ bill debated on Friday was brought by a former Liberal Democrat cabinet minister, Michael Moore.

A long British tradition of NGOs and faith-based organizations laid the grounds for an effective lobby of MPs by their constituents. Founded 17 years ago, DFID has become the world’s leading bilateral aid agency. And yes, I dare say there are elements of colonial hangover – duty, guilt, or White Man’s Burden, you decide.

Some impressive lobbying

I can’t help being a contrarian, and amid the euphoria, noted that some of the most interesting current work on reforming aid, such as the Doing Development Differently initiative, emphasizes that money is often not the main need in tackling issues such as dysfunctional governance – indeed, it can get in the way. How does the vote affect that debate?

Following the vote, the FT argued that it ‘wrongly puts the priority on the quantity of money that Britain spends on aid rather than the quality of its projects.’ Actually, the exact opposite is true. Having now settled the issue of aid quantity, aid organizations, decision makers in developing countries, academics and critics can start to address issues of aid quality that have previously received too little public attention – not least because supporters of aid have been understandably wary that public constructive criticism intended to improve the way aid works would be twisted by ‘gotcha’ critics looking to cut the budget.

This is particularly true in the case of innovation. Aid agencies need to find new answers and approaches on everything from fragile states to climate change to rights and accountability. But fear of failure and a tendency towards box-ticking has made it extremely hard to experiment, fail and learn. Aid sceptics have argued in the past that the sheer volume of aid makes it impossible to be agile, flexible and try out new things, and that ‘less and better aid’ should be the mantra. But a shrinking aid budget comes with anxiety and pressures of its own – there is no sign of those countries that have cut aid becoming suddenly more innovative. Quite the reverse.

The next frontier challenge is how to use aid money to help find these new solutions. Perhaps the big battalions of aid dollars could be directed where we know they are effective – vaccines, research, teachers and nurses, direct support to governments. Then other parts of the aid community can focus on those areas (such as governance), where the need is for brains not bucks – DFID and others won’t have to constantly look over their shoulders and worry about attacks from the aid sceptics when funding research, trying out new things (with a consequently higher likelihood of failure) and finding and keeping expert staff (especially from the countries concerned).

Getting serious about issues of quality and innovation matters not just because it will ensure that aid has wider impact. It will also help prevent any subsequent reversal

Now can we talk about quality please?

of Friday’s vote. Despite leadership from the top, support for aid among backbenchers is shallow, and public opinion polls are contradictory. Aid proponents would be very unwise to rest on their laurels after this vote – there is a lot of work to be done.

If Friday’s decision leads in that direction, this could be the dawn of a whole new era for British aid, hopefully with knock-on effects on other donors. Aid might just have got its mojo back.

For other analysis of the vote, try the Guardian’s Larry Elliot insisting that every silver lining has a cloud.

December 7, 2014

Links I Liked

A Monday morning time waste kit – highlights from last week’s @fp2p twitter feed:

According to SIPRI, Africa’s arms spending grew 8.3% in last year – the fastest regional arms race in the world

Top polemic from Owen Barder. If the world was one country, global institutions would make it a failed state.

Ben Ramalingam loves the new World Development Report (on mind and culture), its alternative to the logframe and its message for development professionals to examine their own biases

Excellent reflection on Piketty, one year after publication, from Branko Milanovic. Why so popular? Will it last? What shortcomings have been revealed?

Teaching economics after the crash: the Student rebellion: 40m Radio 4 piece with Aditya Chakrabortty, Ha-Joon Chang et al

How an epidemiologist-turned-mayor used a data-driven approach to tackle Colombia’s homicide rates

Francisco Toro (aka The Campaign for Boring Development) goes there: the case for rethinking attitudes to GM

How a well-intentioned U.S. law left Congolese miners jobless – is this a rerun of the Harkin child labour/garments Bill in Bangladesh?

And as I’ve just been in Malta, a couple of things on Migration:

UKIP’s Schrödinger’s immigrant who ‘lazes around on benefits whilst simultaneously stealing your job’

And a truly harrowing but brilliant film: Dying to get here – Channel 4 News piece on the 500 migrants who fled to Europe from Egypt – only 11 made it.

December 4, 2014

How the Other Half Farms: Important new book on Gender in Agriculture

This guest post is from Dennis Avilés (right) , Oxfam’s Sustainable Agriculture and Gender Advisor

, Oxfam’s Sustainable Agriculture and Gender Advisor

Trying to explain why half of the world’s farmers are systematically underperforming can be elusive. However, the recently published “Gender in Agriculture. Closing the knowledge gap” by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation has just done that. The book is a series of background studies commissioned for The State of Food and Agriculture 2010-11 with specific focus on gender knowledge gaps, which happen to be many and which run deep.

For development research and practice veterans, walking through the book is an experience of encountering both well-known old facts and some surprising new evidence. But it is also inspiring. The chapters on data and methods send the message that complexity can be captured only when we break it down into different key types of data without losing sight of the relation between them. And in doing so, we can challenge received wisdom. For example, Doss contests the oft-quoted fact that women produce 60 to 80% of food in the developing world, mainly because when measuring women’s labour, it is difficult to separate it from other uses as well as from men’s labour, “and that cannot be understood properly without considering the gender gap in access to land, capital, assets, human capital, and other productive resources”.

But it is as much about the kind of data to collect as it is about whom to ask and how. Behrman and co-authors remind us that men and women spend the income under their control in different ways and that they do not always pool resources. Therefore, the straightforward method to address power bargaining and intra household decision-making is to consistently collect data from both women and men. Mixing quantitative and qualitative methods is recommended as the best way to cover a range of agricultural issues efficiently and (here’s the best part) both methods are explained for any readers who don’t know them/have forgotten.

I remain sceptical, however, about the value of building new academic models of farmers’ bargaining power and decision making processes. Behrman and co-authors argue that “formulating the appropriate model of household bargaining must be based on a better understanding of culture and context” but even if quantitative social scientists are involved, this seems self-defeating. Do we really need models to predict behaviour and change in a particular local setting and at a specific point in time? Not to mention the faces of disbelief that these attempts provoke among many practitioners in the South. Call me conservative, but I still believe that anthropological and participatory methods aimed at rigorously listening to people and understanding power dynamics are more powerful, cheaper and effective than numeric models in revealing the likely results of actors’ motivations and agency.

I remain sceptical, however, about the value of building new academic models of farmers’ bargaining power and decision making processes. Behrman and co-authors argue that “formulating the appropriate model of household bargaining must be based on a better understanding of culture and context” but even if quantitative social scientists are involved, this seems self-defeating. Do we really need models to predict behaviour and change in a particular local setting and at a specific point in time? Not to mention the faces of disbelief that these attempts provoke among many practitioners in the South. Call me conservative, but I still believe that anthropological and participatory methods aimed at rigorously listening to people and understanding power dynamics are more powerful, cheaper and effective than numeric models in revealing the likely results of actors’ motivations and agency.

The chapters documenting gender gaps bring us back to the persistent reality of women’s constrained access to land, agriculture-related services and opportunities. The authors offer us not only a wide range of policy mechanisms that could overcome women’s disadvantaged position, but also highlight the importance that social norms, family responsibilities, life cycles, women’s availability of time and collective action could play in unbalancing the equation: better policies -> better outcomes. In a brilliant study, for example, Harris analyses the implications of four key health and nutritional disorders (undernutrition, iron-deficiency anemia, HIV, and malaria) for men and women and finds that women are generally disadvantaged across disorders due to both biological and social vulnerabilities.

The section on markets and gender-based barriers shows that working on gender and markets goes far beyond involving more women in value chains. Rubin and Manfre argue that “In many ways the diversity of approaches is evidence of the infancy of the intersection of these two technical areas and the steep learning curve facing value chain and gender practitioners as they attempt to integrate their activities, goals and objectives.” Initiatives that integrate market systems and gender while tackling  food security appeal to common sense, for example, developing value chains in crops with added nutritional and health benefits. However, the authors warn of the need to pay attention to women’s time allocation patterns, access to and control over income, and decision-making opportunities. This section of the book makes crystal clear that, as important as it is to tackle women’s access to productive assets and market opportunities, it is equally important to work on social norms and women’s time burden, the two long- ignored elephants in the room of economic development.

food security appeal to common sense, for example, developing value chains in crops with added nutritional and health benefits. However, the authors warn of the need to pay attention to women’s time allocation patterns, access to and control over income, and decision-making opportunities. This section of the book makes crystal clear that, as important as it is to tackle women’s access to productive assets and market opportunities, it is equally important to work on social norms and women’s time burden, the two long- ignored elephants in the room of economic development.

Three final studies on research, development and extension systems offer a prolific array of practical mechanisms both for increasing women’s representation and influence in the scientific community in agriculture. They are not new: calls for women to set priorities for research, encourage young girls to pursue scientific careers or strengthening women’s groups to better articulate their needs and demands, for example, are well known. What is new and practical is the updated data, albeit scattered and imperfect, to support these claims. Moreover, the old familiar strategies are presented in line with the shift of focus from production toward a broader view of agriculture and food systems.

I am grateful I could read the book; it is one of those published once every three or five years that can really guide our thought and work. The knowledge gap of gender dynamics in agriculture, so often put forth as an excuse for inaction, is narrowing.

One minor criticism: a stronger focus on power analysis would have made the publication more relevant. What is the role of the global forces that influence national governments to divert resources from smallholder farms towards big industrial farming in this picture? Could the worrying currents preventing women from accessing education and training centres be reversed? What might persuade more governments to take up the gauntlet?

One minor criticism: a stronger focus on power analysis would have made the publication more relevant. What is the role of the global forces that influence national governments to divert resources from smallholder farms towards big industrial farming in this picture? Could the worrying currents preventing women from accessing education and training centres be reversed? What might persuade more governments to take up the gauntlet?

December 3, 2014

If you read one paper on the post-2015 process, make it this one

The SDGs/post 2015 debate just got interesting. Regular readers of this blog will know that up to now I have been a convinced sceptic on the post-2015 circus (see this  2012 paper on why). But now the endless attempt to hang more/fewer development baubles on the SDG Christmas Tree is coming to an end, and we are coming to the moment of truth – how to ensure that whatever is agreed will have an impact where it matters – the policies and practices of national governments?

2012 paper on why). But now the endless attempt to hang more/fewer development baubles on the SDG Christmas Tree is coming to an end, and we are coming to the moment of truth – how to ensure that whatever is agreed will have an impact where it matters – the policies and practices of national governments?

A brilliant, highly original new ODI paper from May Miller-Dawkins (a friend and Exfam colleague), makes a massive contribution to that debate. It argues for leaving the MDGs behind (hooray!), and basing the level of ambition, implementation and reporting requirements much more on those other aspects of international norm setting in areas such as Human Rights and the Environment, which have had far more tangible impacts on government behaviours.

Here’s the Exec Sum:

‘As we come ever closer to the final negotiation and agreement of a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it is likely that there will be many calls to make sure they are practical, reasonable and measurable. This report suggests that we may need to look at the SDGs in a different light: as closer analogues to international human rights and environmental agreements than international programmes or, even, than their predecessors, the Millennium Development Goals.

The report examines evidence from international agreements and other international initiatives to derive lessons for the design of the SDGs. Examining over 150 pieces of literature, this report has four key messages:

“Practicality” should not blunt ambition in the final stages of the SDG negotiations: the high ambition and non-binding nature of SDGs could increase, rather than diminish, their overall and long-term impact. In a variety of cases, higher ambition, lower enforcement agreements have allowed domestic groups to use international norms and frameworks for leverage to generate change. Equally, in cases of uncertainty where states may be willing to act but uncertain what they can achieve, non-binding agreements have led to greater change in behaviour than stronger enforcement but lower ambition agreements. The potential for strong normative influence and social mobilisation at a domestic level is increased if the SDGs can articulate principles that can be effectively adapted into political systems and debates. In the final stages of negotiation, groups will need to pay attention to the level of ambition of the goals and the internal normative coherence between the goals.

“Practicality” should not blunt ambition in the final stages of the SDG negotiations: the high ambition and non-binding nature of SDGs could increase, rather than diminish, their overall and long-term impact. In a variety of cases, higher ambition, lower enforcement agreements have allowed domestic groups to use international norms and frameworks for leverage to generate change. Equally, in cases of uncertainty where states may be willing to act but uncertain what they can achieve, non-binding agreements have led to greater change in behaviour than stronger enforcement but lower ambition agreements. The potential for strong normative influence and social mobilisation at a domestic level is increased if the SDGs can articulate principles that can be effectively adapted into political systems and debates. In the final stages of negotiation, groups will need to pay attention to the level of ambition of the goals and the internal normative coherence between the goals.

National platforms need to include diverse stakeholders and have time for genuine dialogue: The effects of international agreements are “highly contingent” on the dynamics of domestic social mobilisation and existing institutions. As such, it is better that both goals and targets are not overly prescriptive as to how they should be achieved. Successful national problem-solving requires intensive debate and dialogue amongst diverse stakeholders to create a platform for experimentation not just “implementation”. The national processes will need time and should be built into the timeframe for “implementation” and “results”.

Knowledge and monitoring can drive progress, not just measure it: At the national level, dialogue by diverse stakeholders that creates a more consensual definition of the problem can create a platform for successful problem solving. At the international level, programs of knowledge generation have reduced uncertainty, changed political positions, and ultimately strengthened the effectiveness of environmental regimes. There is already significant movement towards improving available statistics through the data revolution. Beyond this, investment in qualitative assessment and the careful design of national and international platforms and networks for dialogue, information sharing and debate are crucial.

SDGs reinforce existing international norms, and can strengthen their existing monitoring platforms: In the Open Working Group draft, the majority of goals are underpinned by international human rights and environmental law. To contribute further to strengthening those norms, the SDGs should explicitly indicate the harder law basis of the goals. Beyond an SDG platform for measurement, the SDGs could be used to strengthen the monitoring, verification, and reporting processes in human rights and environmental regimes. Creating stronger ties and potentially drawing greater attention to these can strengthen their work as platforms. In the environmental and sustainability area this can contribute to the programmatic creation of knowledge as a key part of the pathways to success. In the human rights area this can strengthen the attention given to evidence provided by diverse domestic actors and the potential for social enforcement against human rights violators or laggards.

After years of debate and dialogue at the international level, it’s possible that SDG-fatigue will lead to settling for practical, achievable goals and targets over ambitious

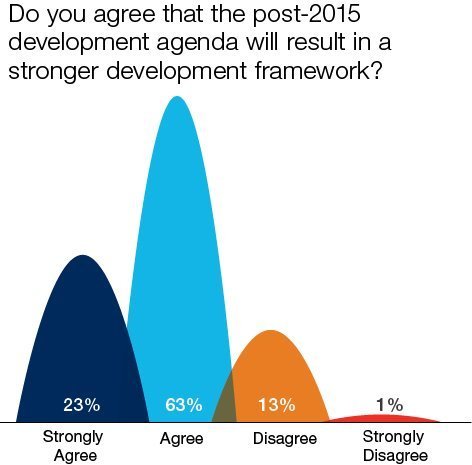

I’ve finally made it to the 1%

principles that strengthen norms and give national groups a further point of lever. Exhausted by international processes, and short deadlines for national targets could also truncate the needed dialogue at the national level in favour of a technocratic process to determine national targets. However, if we take heed of past experience – not just of the MDGs but of international agreement and initiatives – we won’t let practicality blunt our ambition, and we’ll take the time to make sure that global goals can be used for real problem solving around the world. ‘

This all strikes me as tremendously useful and important. I think she could have gone further in terms of how the actual reporting could help ensure traction – e.g. the Convention on the Rights of the Child requires countries to report publicly every 5 years to a special UN Committee. I am also a big fan of regionalism – if the annual reporting came in the form of regional league tables, highlighting the region’s heroes and zeroes on any given issue, governments, media and civil society organizations are far more likely to sit up and take notice. Maybe that could be May’s next ODI paper?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers