Duncan Green's Blog, page 176

November 12, 2014

What are the big trends on conflict and fragility? Some great presentations at DFID

I spent a seriously interesting couple of days this week in a rainswept Brighton, attending DFID’s annual get together of its 200 (approx) governance and conflict advisers. Definitely worth a couple of posts – I’ll give some general impressions tomorrow, but want to start with a fascinating panel on conflict and fragility.

First up was David Harland, an ex diplomat with a wry sense of humour whose organization, the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, describes itself as a ‘private diplomacy organization’. David said that included handling ‘confidential first contact between governments and rebel/terrorist groups’. V James Bond.

In his 15 minutes, he made some powerful points:

There was a liberal consensus from 1990-2010, summed up in the World Development Report 2011. This argued that enough stability, resources and time would be sufficient to achieve security in most situations. Sending in peacekeepers became the default international response to violence in poor countries. If things didn’t go well, that was because even the best performers take 20 years to sort themselves out. ‘On our individual career trajectories that’s a  very happy message’.

very happy message’.

There was a clear point of inflexion 1990 on conflict and democracy (see graph, below). Residual conflict is the biggest human security challenge: it is the largest driver of poverty, globally networked (drugs, balloon effects between countries – as an example, look at how many more people have died in drug-related mayhem on the Mexican border, than in Afghanistan, yet we ‘barely have a word to describe’ what is going on there). It is increasingly criminalised, very hard to escape, and impossible to predict (our record is ‘crap’).

But that consensus in now in crisis: there has been an uptick since 2010 in conflict (see slide), but also in autocracy. Is this a blip or another point of inflexion? Interventions have gone bad in Afghanistan, Iraq, South Sudan, Libya. ‘My whole life story has been a falling out of love with intervention’ (he started in Bosnia). This has led to a growing perception of the ‘futility of force: it is not at all clear that we make things better by going in’.

On the retreat from universal norms for example on the desirability of electoral democracy, China provides an ‘active counternarrative’. This has encouraged a reversion to illiberalism in Egypt and elsewhere.

On the retreat from universal norms for example on the desirability of electoral democracy, China provides an ‘active counternarrative’. This has encouraged a reversion to illiberalism in Egypt and elsewhere.

So what can be salvaged? Some elements of a rather more modest/realistic approach:

Inclusion not intervention/imposition. Problems start when it is ‘our project’. Chances of success are much greater when a peace process is locally owned, e.g. the Mindanao process in the Philippines may be messy, but it is inclusive – all the local players feel it is theirs; ditto Kenya, whereas South Sudan contains high levels of external imposition.

‘Good enough states’ such as Rwanda or Fiji, especially given the decline in Western leverage.

Containment – are there places (Eastern Congo, Haiti) where we admit we can’t do more than ‘provide a bed for the night’ to those affected. Otherwise, strategies should be aimed at preventing contagion to neighbouring states.

Brilliant, and here’s his powerpoint (David Harland DFID Presentation). Next up was Mary Kaldor. For her, the real question is what you do after the conflict subsides – ‘peace-building and state-building’ (PBSB) in DFID-speak (they had a 40 page list of acronyms on the intranet when I worked there in 2004, bet it’s got longer since then). ‘Nearly all conflict countries continue to be plagued by violence (social as well as political), despite all the aid dollars. What are we doing wrong?’

For Mary, the problem starts with confusing ‘violence’ and ‘conflict’: peaceful societies evolve a range of mechanisms for dealing with conflicts that aim to resolve problems. We mistakenly tend to see armed conflict as the continuation of such politics by other means (shades of Clausewitz). In fact violence closes down conflict, by framing all disputes as ‘us v them’, making it much harder to resolve those little everyday conflicts and thus solve problems.

Mary thinks that instead, we should see violence as more like a ‘mutual enterprise’, where armed groups have much to gain (politically, or financially) from continuing to fight, rather than from actually winning. Violence constructs sectarian differences, separating out the ‘us’ and ‘them’, which provides the basis for elites to get and retain power + various rents. ‘Violence provides a cover for a predatory political economy, a new set of power relations.’

If we think about bouts of armed violence as a societal condition or mutual enterprise, what are the implications for our action?

Expect no clear beginnings and endings. The imaginary world of conflict resolution plans for phases (prevention, reconciliation, peace making, peace keeping, peace building, exit). Actually those phases don’t really exist.

Peace agreements are premised on the idea of conflict as a contest, in which two sides have legitimate grievances that can be solved through talks. But if it’s a mutual enterprise, the only reason armed groups will agree is if it entrenches their power and predation, as in Bosnia.

Peace agreements are premised on the idea of conflict as a contest, in which two sides have legitimate grievances that can be solved through talks. But if it’s a mutual enterprise, the only reason armed groups will agree is if it entrenches their power and predation, as in Bosnia.

So we need agreements, but have to think about them differently. She agreed with David on inclusiveness, but also suggested strengthening zones where conflicts don’t exist, supporting local ceasefires, and involving non-violent actors with a stake in peace. Peace Agreements between armed groups need to lose their stature – they are just one element in a broader process, not the Treaty of Versailles.

What can foreign governments do to help? On the economic side, give attention to creating jobs as much as preventing violence. On the political, help bring in ‘the middle people’ who care about the public interest – teachers, doctors, lawyers.

Great stuff. Tomorrow, some general thoughts on tribal rivalries between econs and poliscis, and the alarming absence of rights from the way DFID thinks about governance.

November 11, 2014

Should NGOs jump on board the Payment by Results bandwagon? New research suggests proceed with caution

Payment by Results is getting a lot of airtime at the moment, not least due to the indefatigable advocacy of CGD. Should NGOs be jumping on the bandwagon? Michael O’Donnell,  Head of Effectiveness & Learning at the UK network of Development NGOs, Bond, summarizes the findings of some new research.

Head of Effectiveness & Learning at the UK network of Development NGOs, Bond, summarizes the findings of some new research.

Over the summer, DFID launched a new strategy on Payment by Results (PbR), which committed them to considering the use of PbR in all new funding decisions. Did this seal the judgement that working with DFID was a “demoralising dehumanising nightmare” as Robert Chambers memorably claimed? Or was it just a question of finding the right 12 Principles to make it work, as the not-quite-a-wonk-war between Stefan Dercon & Paul Clist and the Centre for Global Development suggested?

We found it hard to tell. A lot of the commentary was abstract and didn’t seem to speak to the realities that NGOs faced. So we asked NGOs with PbR contracts about their experiences, looked at evidence from domestic sectors in the UK where these mechanisms have been used for some years, and had a think. The product of that is a new report on “Payment by Results: What it Means for UK NGOs”. Launched yesterday, it aims to help NGOs think through the implications of PbR for themselves.

At its simplest, PbR involves the implementing organisation paying upfront for some or all of the costs of activities, and the donor only pays them back if they verify that pre-defined results were achieved. The theory is that it incentivises aid agencies to ensure that their activities are actually delivering changes in lives.

If donors allow implementers the flexibility to change and adapt their plans as they learn and progress, another assertion is that it will promote innovation. Ultimately, there should be better results and the donor or taxpayer only pays for success: a very appealing idea for cash-strapped governments keen to assure a suspicious electorate of their firm hand on the financial stewardship tiller.

But needless to say, the reality is a lot messier. On innovation in particular, proponents of PbR appear guilty of some overselling. PbR contracts transfer financial risk onto NGOs whose unrestricted funds and reserves are precious. In extreme cases, the financial risk would be enough to put the NGO out of business if it was realised. NGOs thus talked to us about “playing it safe” in their bids for PbR contracts, going with tried-and-trusted interventions rather than innovating.

But needless to say, the reality is a lot messier. On innovation in particular, proponents of PbR appear guilty of some overselling. PbR contracts transfer financial risk onto NGOs whose unrestricted funds and reserves are precious. In extreme cases, the financial risk would be enough to put the NGO out of business if it was realised. NGOs thus talked to us about “playing it safe” in their bids for PbR contracts, going with tried-and-trusted interventions rather than innovating.

Other aspects stifled innovation too. Commissioners new to PbR themselves have been anxious to retain control over outputs, budgeting and reporting, and have been reluctant to liberate PbR implementers from the tyranny of monthly or quarterly auditing. At least one NGO has successfully pushed back on this, however.

The nature of what you’re trying to change affects your ability to innovate and adapt. The number of times that you can try new things, monitor outcomes, learn and change course within a typical three year project cycle differs hugely between, say, a project treating acute malnutrition and one aiming to change social norms about girls’ education.

A second area of concern is whether and how PbR contracts reward efforts to tackle inequality. A model that pays a fixed amount for a defined change, yet doesn’t take account of potential differences in the cost of achieving those outcomes for different people, can be the enemy of inclusion. In response to a PbR-based tender for water projects, for example, where bidders could propose to work in a wide selection of countries, we heard two separate examples of organisations explicitly deciding not to opt for South Sudan because they thought it would be too risky and would make their costs look higher than competitors who proposed to work in more straightforward environments.

Another organisation told us how they debated internally whether to include disabled children in their targeting for an education programme. They knew it would cost more to provide the full range of services needed to get those children into school than the average price the PbR contract would pay. Being a values-based organisation, they went ahead anyway. But could we bank on the same behaviour from all bidders in competitive processes? In the UK, where the phenomena of “creaming” the easy clients and “parking” the complex ones are well known, experience suggests we can’t.

These are all potentially manageable issues. Greater collaboration between donors and potential service providers at the design stage could help inform  whether PbR is appropriate at all, and if so how best to make it work. Flexibility in contract delivery can be negotiated. The percentage of the contract value that is withheld until results are achieved can be adjusted. Differentiated pricing can be agreed to ensure that service providers are rewarded for targeting marginalised groups. And NGOs can learn to become more adept at pricing the risk of failure into their bids.

whether PbR is appropriate at all, and if so how best to make it work. Flexibility in contract delivery can be negotiated. The percentage of the contract value that is withheld until results are achieved can be adjusted. Differentiated pricing can be agreed to ensure that service providers are rewarded for targeting marginalised groups. And NGOs can learn to become more adept at pricing the risk of failure into their bids.

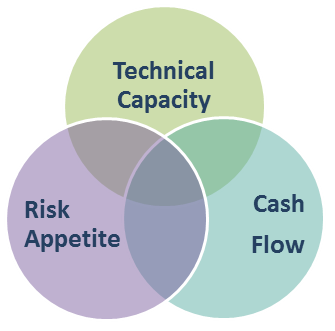

But this is a complex business. Our guidance points to issues for NGOs to consider before bidding for PbR contracts, including their financial situation, their technical capacity (in bidding, monitoring and evaluation and contract negotiating amongst others) and their risk appetite. It also sets out different programming considerations that affect whether PbR may be appropriate or not, and how to mitigate risks of PbR producing unintended consequences.

Payment by Results isn’t inherently either a good thing or a bad thing. Any new idea needs a lot of testing, learning and refining. And that applies even more so to one that carries such high financial risk to organisations and which can undoubtedly work against its stated aims if handled badly. Our advice? Proceed with caution.

November 10, 2014

What next for human rights organizations like Amnesty?

Autumn/fall must be the blue skying season. I ended last week having my remaining brain cells picked in exchange for yet another free meal by Amnesty  International’s Savio Carvalho (campaigns and advocacy) and Clare Doube (evaluation and strategy). Going to have to watch my waistline.

International’s Savio Carvalho (campaigns and advocacy) and Clare Doube (evaluation and strategy). Going to have to watch my waistline.

They are thinking through Amnesty’s global strategy for 2016-2019, and as with many INGOs, want to move away from a London-dominated, centralized model towards a higher degree of regional/national control, and local partnership. They are also eager to identify and build on their ‘USPs’ – Unique Selling Points – compared to other organizations. Here are some random highlights of the exchange.

On USPs for human rights organizations:

Protecting the protectors: there is a really worrying global crackdown on civil society activities. Amnesty could provide a great contribution as a watchdog and rapid reaction organization, working with the likes of ICNL or Civicus.

Talking to liberals: the language of individual rights is the language of political and economic liberals, who are put off by more collectivist/left wing discourses. We need to talk to those people (not least because they are in power in many countries), so it would be good if Amnesty maintained that position, rather than joining the herd of more overtly political NGOs.

A protest, not a funeral

Then there’s the lawyers. Human Rights is a highly legalistic domain. That has its downsides, but does mean that the legal profession is highly influential and a massive potential driver of change. Amnesty has a lot of lawyers doing pro bono work at global level, but lawyers at national level could provide a unique constituency for their work (think Pakistan, where suited lawyers demonstrate against the government).

As for ‘going national’, everyone (including Oxfam) is moving in that direction. But Amnesty is a Human Rights NGO and movement, which sees those rights as universal and indivisible. Does that make the process different from development NGOs?

According to Clare and Savio, they already struggle to find the balance between universalism and national context. Take sexual and reproductive health and rights. According to Savio, they are ‘an essential element of Amnesty’s work, but when it comes to an issue like abortion while our policy position is clear, we will only campaign on issues that are relevant within a particular country context’. So there are limits to universalism. Development NGOs, at least those with a rights based approach, also have red lines, but it’s probably easier for them to compromise with local context and reality.

On some issues, (say violence against women or children’s rights) global norms seem to be converging (albeit with some big exceptions) towards the kind of world Amnesty seeks, but on others (eg gay rights), norms seem to be diverging at high speed – think Africa v US. That places a strain on decentralized organizations, as local chapters often reflect national norms. Clare and Savio say (with a sigh) there’s no easy answer to this – you just have to keep people inside the organization talking in a ‘long conversation’. Yeah, right, I know what that feels like.

An added complication to this centre v country tension is the rise of regionalism.

Anyone fancy some convening and brokering?

Bodies like the African Union and EU are becoming increasingly influential in promoting rights (eg the African Women’s Rights Protocol) and Human Rights will have to shift resources to respond. Working more at a regional level could at least help straddle the tensions between global and national.

A couple of extra thoughts on the comparison between debates in our two overlapping but different sectors:

One characteristic of human rights organizations is that they appear, at least from the outside, to promote starkly demand side approaches – people on the streets or lawyers in the courts demanding an ever-expanding range of rights. But a lot of the research on institutional reform and accountability that I have been covering in recent years suggests that both supply side (human rights courses for the police) and demand side are less productive than a ‘convening and brokering’ approach that brings all sides together to search for common solutions – could Amnesty do more of that without compromising its principles?

Finally, an interesting discussion on inequality, in light of the launch of Oxfam’s Even it Up campaign. I’ve written about what a focus on inequality adds to the traditional poverty reduction agenda, but if a human rights organization like Amnesty wanted to get serious about inequality, what would it do differently? Would it focus more on social cohesion, social contracts, and political capture by elites? Would we see Amnesty trying to reform the rules for election campaign financing? Interested in your suggestions on that one.

And here are some related thoughts on the human rights approach to development.

November 9, 2014

Links I Liked

Another selection from last week’s @fp2p twitter-fodder

OK, let’s start with Ebola

Helpful map (because the world seems confused on this point)

Rick Rowden says the reason why health systems in West Africa are so ill-equipped to deal with Ebola. Is partly the fault of previous IMF programmes

‘Explain it like I’m 5’. UNICEF takes a cute kids approach to explaining what it’s all about. Not sure it works tho. [h/t Tom Murphy]

And elsewhere

An interesting bit of man bites dog: In praise of Bolivia’s controversial new child labour law. By lowering the legal age limit, it recognizes and gives rights to working kids – i.e. the anti-prohibition argument

The new 116 page IPCC climate report boiled down to 29 depressing bullets, c/o Scientific American [h/t Kumi Naidoo]

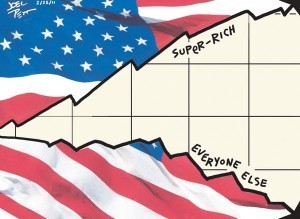

Two striking graphs from the US. New data support Piketty’s arguments, while (left) the income gains going to the top 1% have risen from 5% of total in 1954-7 to 95% in 2009-12 [h/t Conrad Hackett]

Two striking graphs from the US. New data support Piketty’s arguments, while (left) the income gains going to the top 1% have risen from 5% of total in 1954-7 to 95% in 2009-12 [h/t Conrad Hackett]

If you’re interested in governance, institutions etc, Harvard’s Matt Andrews is on fire at the moment. His Building State Capability programme has a sharp new website. He also has a nice summary of the PDIA (problem-driven iterative adaptation) approach to governance reform, with funky graphics and lots of case studies

Why the new Core Humanitarian Standards remind MSF of Pippa Middleton’s advice on dinner parties [h/t Tom Murphy]

Some arguments against evidence-based policy, including that it provokes over-confidence, conservatism, elitism, and ignores the importance of symbols

Sweet study in the travails of masculinity. Kenyan sons summon the courage to tell their fathers ‘I Love You’ (on the phone). [h/t Irungu Houghton]

Finally, (and sticking with the whole father-son thing) when torn between fatherly pride and the desire never to mention Russell Brand on this blog, nepotism wins every time. Son Finlay’s perceptive blog on what Brand Brand says about the state of British politics.

November 6, 2014

How can Faith Groups get better at campaigning on climate change?

On Monday, I had not two fascinating big picture conversations under Chatham House Rules – these are a gift to bloggers as you don’t have to remember who said what,

and can take all the credit for anything clever. I’ve already blogged the discussion on theories of change and the Middle East. The second was run by a faith-based NGO in the middle of a big rethink of its campaigning on climate and development. OK, it was Tear Fund – they don’t mind me saying. The format was interesting – get about a dozen assorted wonks from NGOs, thinktanks, academia and government in a room for two hours to discuss a draft paper, then continue over drinks and dinner. I might even adopt it for the book.

and can take all the credit for anything clever. I’ve already blogged the discussion on theories of change and the Middle East. The second was run by a faith-based NGO in the middle of a big rethink of its campaigning on climate and development. OK, it was Tear Fund – they don’t mind me saying. The format was interesting – get about a dozen assorted wonks from NGOs, thinktanks, academia and government in a room for two hours to discuss a draft paper, then continue over drinks and dinner. I might even adopt it for the book.

The background paper, by Alex Evans (they really don’t take the Chatham House thing very seriously) is here. Alex asked me to invite comments and stressed that ‘the paper is definitely not the first draft of a report, but much more just a starter for ten to help get a conversation going and help us scope out the ground.’

The effect of these conversations is to test, tweak and strengthen your existing ideas, get a feel for where the current zeitgeist conversation is going, update you on the latest in-words (and people – I must have missed the canonization of Martin Wolf, but since the global financial crisis, he is now quoted reverentially as the guru on almost everything) and drop in the odd lightbulb/aha moment + references to new books and papers. There were plenty of those on Monday – some highlights:

To get real movement on climate change, we need a grand narrative on One World, sustainability and the need for environmental stewardship. But campaigners also need quick wins to build optimism and momentum. Those often have to be much less ambitious and system-shaking to have a chance of being adopted. The danger is that watered down quick wins will undermine the grand narrative (agreeing to more comfortable slave ships rather than total abolition). We need to make sure quick wins are aligned with the end goal, and develop the ground for a subsequent set of policy changes that are currently ‘just beyond the possibility horizon’ and make sure they fit the big narrative too.

What is the point of page after page of policy recommendations that no-one reads or believes? Their purpose is to prove that the campaign organization is across the detail of the issue, and give a sense of what practical steps are necessary. A set of illustrative examples of where governments, corporations and others have successfully taken action would meet those criteria, be more interesting, and would acknowledge the fact that boilerplate policy blueprints make no sense in complex systems where the right policies will depend on context. So could we replace the boring Recommendations section in all our reports with ’10 real world examples of what works’ please?

Grey Panthers are scary

Cities not States? Partly in reaction to the failure of national governments and global institutions to tackle the big issues, there is a growing buzz about the transformative potential of cities, with discussions of convening a World Parliament of Mayors. See this Benjamin Barber Ted Talk or Hugh Cole’s recent blog for more.

Personal critical junctures: not only are windows of opportunity a crucial part of change at political and social levels, they are also critical for individuals’ views and actions. The interesting thing is that they are partly predictable – research suggests three big ones: leaving home/going to university, having your first child, and retiring. We design campaigns around the first, but what about the other two? (Cue my customary doomed attempt to get people interested in a Grey Panthers movement).

Is social capital really withering on the vine? An interesting discussion on the state of ‘congregational spaces’ that act as islands of social capital. Some (trade unions, traditional churches in the UK) may be fading, but many aren’t (schools, nurseries, healthcare centres, Women’s Institutes) while others (social networks, food growers, transition towns, book clubs, sports clubs, even the Girl Guides) are booming. Such spaces both provide ‘safety in numbers’ for people wanting to take action on a collective problem, and the threat of sanctions (mainly social) to help them stick to their promises. It’s the difference between dieting alone, and knowing you have to go to weight watchers.

The hair shirt community, who like the idea of giving up stuff, rationing, making sacrifices etc, is well represented among Church activists, but stressing the need for sacrifice is probably not a good tactic in a public campaign, let alone with policy makers (‘with the grain, and not too much pain’). Instead, some nice thoughts on which climate change narratives work with which constituencies within the Christian churches;

For centre-left: fairness and justice

For conservatives: Stewardship

For neoliberals: Property Rights also bring Property Responsibilities – if you use it or burn it, you are responsible for the pollution that results

Finally, what lessons could we learn from the Jubilee 2000 movement on debt relief? At Alex’s suggestion (see his blog), I went back to the Biblical Chapter that inspired the debt campaigners, and was struck by how much it contains that could form the basis of an environmental Jubilee movement:

‘The land itself must observe a sabbath to the Lord. For six years sow your fields, and for six years prune your vineyards and gather their crops. But in the seventh year the land is to have a year of sabbath rest, a sabbath to the Lord. Do not sow your fields or prune your vineyards. Do not reap what grows of itself or harvest the grapes of your untended vines. The land is to have a year of rest.’

True that. The planet really needs some time off right now. The whole church tradition of tithing is also worth looking at. Why not reframe a carbon tax or other environmental taxes as a climate change tithe to protect the planet for future generations?

Leviticus, tithes, world parliaments of mayors – the joy of these kinds of conversations is that you end up in the most unexpected places. That and the free dinner.

Update: Read Alex Evans blog on the meeting and (more important) a brilliant, highly theological reflection on the c0nversations

November 5, 2014

The Four Magic Words of Development, by Tom Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher

This guest post comes from Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Tufts University,

This guest post comes from Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Tufts University,  drawing from their new paper Accountability, Transparency, Participation, and Inclusion: A New Development Consensus? The penultimate para in particular got me thinking about the different tribes present at the recent Doing Development Differently event.

drawing from their new paper Accountability, Transparency, Participation, and Inclusion: A New Development Consensus? The penultimate para in particular got me thinking about the different tribes present at the recent Doing Development Differently event.

If you are about to visit an organization engaged in international development assistance and are unsure of the reception you will receive, a surefire way exists to win over your hosts: tell them you believe that four principles are crucial for development—accountability, transparency, participation, and inclusion. Your hosts will almost certainly nod enthusiastically and declare that their organization in fact prioritizes these very concepts. This holds true whether you are visiting a bilateral or multilateral aid agency, a foreign ministry engaged in development work, a transnational NGO, a private foundation, or any other type of group engaged in aid work. The ubiquity of these four concepts in the policy statements and program documents of the aid world is truly striking–they have become magic words of development.

Veteran readers of this blog may suspect that with such an introduction, we are about to slash away at these concepts with gleeful Greenian gusto, excoriating the aid community for its unshakable addiction to specious magic bullets. Not quite. Some sober questioning of assumptions is indeed warranted. Our point, however, is not that these ideas are misguided or harmful, rather that the agreement around them is much less solid than the rhetoric might indicate. Look through the veneer of the apparent consensus and a series of significant fissures become visible.

Veteran readers of this blog may suspect that with such an introduction, we are about to slash away at these concepts with gleeful Greenian gusto, excoriating the aid community for its unshakable addiction to specious magic bullets. Not quite. Some sober questioning of assumptions is indeed warranted. Our point, however, is not that these ideas are misguided or harmful, rather that the agreement around them is much less solid than the rhetoric might indicate. Look through the veneer of the apparent consensus and a series of significant fissures become visible.

Divisions start with respect to the place of these principles in the overall aid enterprise. Enthusiasts of the four magic words tend to see them as good things in and of themselves that should be understood as intrinsic elements of development. Yet within most aid organizations skepticism over this view persists. Some are concerned that opening the door to what may be politically normative claims on the development agenda will dilute the core focus on poverty reduction and aggravate disagreements between donors and recipients over basic purposes. The case for the four magic words, traditionalists argue, should rest on their instrumental value.

Yet here too serious divisions persist. Evidence that building accountability, transparency, participation, and inclusion into development assistance will produce better socioeconomic outcomes remains limited and generally inconclusive. If there is one overarching message from the existing research, it is the need for considerable caution regarding expectations of direct developmental impact. This holds true whether the empirical focus is on just one specific element, like transparency or citizen participation, or on the broader proposition that Western-style governance, seen as including the four principles, is vital to achieving or sustaining socioeconomic success.

Fissures also exist concerning the actual application of these principles. Behind very similar sounding policy statements lie drastically different levels of commitment to  making transparency, accountability, participation and inclusion a serious element of development programming. While some aid groups engage in box-ticking when they address these issues, others attempt genuinely transformative approaches. Such differences not only exist between different aid organizations, but also at times between departments of the same agency or group. And highly varied commitment levels are not just the purview of donors—they also characterize aid recipients. Many aid-receiving governments have signed on to international initiatives involving commitments on one or more of the four magic words, like the Open Government Partnership and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. For some these commitments represent genuine efforts at domestic reform. For others, they primarily serve to give the appearance of political openness.

making transparency, accountability, participation and inclusion a serious element of development programming. While some aid groups engage in box-ticking when they address these issues, others attempt genuinely transformative approaches. Such differences not only exist between different aid organizations, but also at times between departments of the same agency or group. And highly varied commitment levels are not just the purview of donors—they also characterize aid recipients. Many aid-receiving governments have signed on to international initiatives involving commitments on one or more of the four magic words, like the Open Government Partnership and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. For some these commitments represent genuine efforts at domestic reform. For others, they primarily serve to give the appearance of political openness.

The four magic words appear to be a bridge among the three subcommunities that emerged in the aid world as part of the opening to politics in the 1990s—practitioners focused on governance, those engaged in openly political work on democracy building, and those committed to a rights-based approach to development. Over the past decade, governance specialists have become comfortable with the four principles as a natural evolution of the governance agenda; democracy builders see them as an uncontroversial way to slip intrinsically pro-democratic concepts into aid debates; rights enthusiasts view them as cardinal elements of a rights-based approach. Yet in practice, the bridge is only very partial. When it comes to fostering accountability for example, governance specialists often approach the task as a narrow, technocratic enterprise centered on procedural and regulatory improvements in public financial management. Yet for democracy buffs accountability is all about strengthening parliaments, parties, and political contestation. While a governance program may treat government transparency as a mechanism for soliciting citizen input and improving service delivery, rights specialists conceptualize access to information on all aspects of governance as a fundamental right and thus a matter of legal compulsion.

Despite these divisions and uncertainties, we don’t believe that the embrace of accountability, transparency, participation, and inclusion should be dismissed as just one more transitory enthusiasm of the donor community. We see it as a powerful embodiment of the fundamental movement away from the decades-long tendency of the aid community to avoid political dynamics and treat states as deus ex machinas operating without any organic connection to the citizens they are supposed to serve. But we feel that proponents of these principles are prone to believing that the consensus around them is stronger than it really is. They need to face more squarely the many underlying fissures, and look harder for ways to reduce their impact. Some of the divisions, like disagreements over the legitimacy of the intrinsic case for the four principles, reflect differences in the very idea of what development is and are therefore unlikely to be overcome anytime soon. But others, like the continuing divide between governance, human rights, and democracy practitioners, are more amenable to practical solutions. In other words, the consensus on incorporating transparency, accountability, participation and inclusion as core principles of development aid will only solidify if its strongest proponents recognize how shaky it still is.

Despite these divisions and uncertainties, we don’t believe that the embrace of accountability, transparency, participation, and inclusion should be dismissed as just one more transitory enthusiasm of the donor community. We see it as a powerful embodiment of the fundamental movement away from the decades-long tendency of the aid community to avoid political dynamics and treat states as deus ex machinas operating without any organic connection to the citizens they are supposed to serve. But we feel that proponents of these principles are prone to believing that the consensus around them is stronger than it really is. They need to face more squarely the many underlying fissures, and look harder for ways to reduce their impact. Some of the divisions, like disagreements over the legitimacy of the intrinsic case for the four principles, reflect differences in the very idea of what development is and are therefore unlikely to be overcome anytime soon. But others, like the continuing divide between governance, human rights, and democracy practitioners, are more amenable to practical solutions. In other words, the consensus on incorporating transparency, accountability, participation and inclusion as core principles of development aid will only solidify if its strongest proponents recognize how shaky it still is.

November 4, 2014

What happens when 20 Middle East decision makers discuss Theories of Change?

My first job after returning from holiday (disaster tourism in Northern Ireland – don’t ask) was to speak on Theories of Change to a really interesting group – a ‘building a rule of law leadership network in the Middle East’, funded by the UK Foreign Office. The John Smith Trust has about 20 lawyers, civil servants, policemen, UN personnel and business people for a 3 week training programme. Equal numbers of men and women, from Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman. Chatham House rules so that’s your lot viz info.

Over the course of a year, each Leadership Fellow develops an Action Plan for reform back home, ranging from girls’ education to police training to civil society strengthening, and will work on it during their UK visit, where they get inputs from people like me, discussions and visits to the UK Parliament and elsewhere.

I was presenting on theories of change (ToCs) – here’s my powerpoint. My co-presenter (from a UK thinktank) defined a ToC as ‘a conceptual map of how activities to

US military stakeholder map of Afghanistan, aka a complex system

outcomes’. As you might imagine, I disagreed with the implied linearity of that. But the disagreement, and the views of those present was interesting.

However much I may love thinking about systems, uncertainty etc etc, there is clearly a psychological cost to most normal people in ‘going there’ on complexity. People, especially decision makers, prefer to KISS (don’t we all), which leaves them feeling more effective and in control of bringing about change. In contrast, showing people the Afghanistan map (as I invariably do) can easily leave people feeling demotivated and defeated.

So if we want to equip people rather than demoralise them, the language, and examples have to focus not on complexity itself, but on a few things we need to do differently to make our actions more compatible with complex systems. Here are some of the ones that came up.

The problem may not be complex at all, at least to a first approximation – think Cynefin (below): if your problem is in the simple quadrant, then you may be making your life unnecessarily difficult by spending much time on systems and complexity. Wheel out the logframe and get stuck in.

Iteration and Feedback: The key is not to abandon planning, but to treat all plans as rough drafts, in need of regular adaptation and improvement in light of events or increased understanding. Make sure the feedback loops and pauses for reflection are in there from the start to allow you to correct your course as you go. (i.e. you can plan for uncertainty)

Unintended consequences: plans often exist in an imaginary world where the only consequences of our intervention are those we intend. Feedback loops can help identify the other stuff that happens, and adjust plans accordingly.

Resilience, especially to massive setbacks: a heartfelt plea from an Iraqi participant – What do you do when years of painstaking work are destroyed in days by something like the Islamic State? No easy answers except to think about an intervention in terms of its resilience to shocks. In many countries, we have found that ‘power within’ work on things like women’s empowerment is resilient in the sense that newly confident women leaders are the first to start organizing after displacement, or in refugee camps, whereas other things (eg classrooms) are destroyed completely.

Resilience, especially to massive setbacks: a heartfelt plea from an Iraqi participant – What do you do when years of painstaking work are destroyed in days by something like the Islamic State? No easy answers except to think about an intervention in terms of its resilience to shocks. In many countries, we have found that ‘power within’ work on things like women’s empowerment is resilient in the sense that newly confident women leaders are the first to start organizing after displacement, or in refugee camps, whereas other things (eg classrooms) are destroyed completely.

Power and interests become more apparent once the work is under way – in the Middle East, politics and power are often personal, opaque and unfathomable. So by all means do a preliminary power analysis to identify potential allies, opponents or swing voters, but expect to update it as you get more involved in the issue (and other players start to notice and react to your work)

And some dilemmas:

Is the use of ToCs just a problem solving approach – isn’t that very reactive/negative? What about proactively creating a new society? Here I was torn between head (nothing helps you build an alliance for change better than a shared problem) and heart (we all want to build the new society – why should we let ourselves got bogged down in the petty problems of the current system?)

Incremental v Transformational: the standard spiel is ‘transformational good, incremental insufficient’, but does that need to be reframed in light of the Arab Spring? Surely the key lesson of events in Egypt and elsewhere is that a shock can trigger what looks like transformational change, but it doesn’t stop there – institution-building, the long hard slog of politics etc can make or break (or reverse) that transformational potential. So the key question becomes how the transformational and incremental processes are interlinked. Not sure we’ve got much idea how to do that.

Good to be back. Holidays are overrated.

November 3, 2014

Financing for whose development? How official Development Finance Institutions support tax havens

This guest post comes from Mathieu Vervynckt, Policy & Research Analyst with the European Network on Debt and Development (Eurodad)

The Third UN Conference on Financing for Development(FfD), set to take place in Addis Ababa next year, will be a crucial opportunity to discuss two of the hottest topics in development finance today: the use of scarce public resources to leverage private sector finance, and the fight against international tax avoidance and evasion. Both topics come together in Eurodad’s new report, Going Offshore, published today, though probably not in the way you might expect.

Previous Eurodad research has shown that despite the lack of public information about how they work and their impact on development, Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) – government-controlled institutions that support private sector projects in developing countries – have come to dominate the development finance landscape to such an extent that by 2015 the money they channel into the private sector is expected to exceed US$100 billion. They are, in short, the embodiment of an agenda (pushed by, among others, the European Commission) to use more public resources to leverage private finance.

More and more DFI support is also being channelled through financial intermediaries such as investment funds, which lend, in turn, to private companies in developing countries. And here comes the trick: at a time when the political momentum on tax justice is building, Going Offshore finds that many of the funds backed by DFIs are registered in the world’s most secretive jurisdictions – the same jurisdictions that play a systemically important role in helping private companies avoid and evade taxes in developing countries.

This creates an absurd and counterproductive situation. As public institutions aiming to reduce poverty, DFIs are reinforcing an offshore industry that is a major part of the reason why many developing countries can’t collect enough taxes to provide the infrastructure and public services that they so desperately need both to reduce poverty and to provide the platform for private sector investment.

Going Offshore also shows that the use of secrecy jurisdictions by DFIs is an endemic problem. For the purpose of this report we looked only at the top 20 jurisdictions in the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index (FSI), which ranks 82 jurisdictions according to their degree of secrecy and their importance in global finance.

Going Offshore also shows that the use of secrecy jurisdictions by DFIs is an endemic problem. For the purpose of this report we looked only at the top 20 jurisdictions in the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index (FSI), which ranks 82 jurisdictions according to their degree of secrecy and their importance in global finance.

The figures speak for themselves: at the end of 2013, 118 out of 157 fund investments made by the UK’s DFI, CDC Group plc, went through jurisdictions in the top 20 of Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index. In 2013 alone, these offshore funds received a total of US$553 million. Meanwhile, at the end of 2012, four of the 14 direct and indirect investments held by DEG (the German DFI) were structured through the Cayman Islands, St Kitts and Nevis or even the British Virgin Islands – a country of not more than 25,000 inhabitants.

So Eurodad looked at whether or not DFIs have proper internal standards in place to ensure developing countries receive their fair share of tax, and that any controversial jurisdictions are excluded from their daily operations. Two things became clear at a very early stage:

- Some DFIs simply do not have proper internal standards in place, or are unwilling to publicly disclose them. These include the two largest bilateral DFIs – the Dutch FMO and the German DEG – which is particularly appalling given their moral duty to lead by example on the European bilateral stage.

- The large majority of DFIs that make their standards publicly available heavily depend on the ratings put forward by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) Global Forum. CSOs have repeatedly argued that this forum uses unambitious criteria, as they predominantly focus on banking secrecy instead of corporate tax dodging and country-by-country reporting. In addition, many developing countries are not members of this actually not-so-global forum. This is ironic, given that these are the same countries that DFIs are often trying to target, and also the ones that face the most difficulties in collecting their fair share of tax. In contrast, seven of the most notorious tax havens which appear in the top 20 of the FSI, including Switzerland and Luxembourg, are full members of the OECD as well as its Global Forum.

Another critical issue addressed in Eurodad’s new report is how DFIs ensure their standards, however weak, are properly implemented. Going Offshore therefore also analyses DFIs’ due diligence procedures, only to find another worrying trend: it is not standard practice for DFIs to require their investee companies to provide them with financial statements on a country-by-country basis, let alone placing such data in the public domain. Then how do they know where their investee companies are making profits vis-à-vis where the value is created?

This matters because, as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) clearly states, “making firms pay taxes in the countries where they  actually conduct their activities and generate their profits (…) would require the implementation of country-by-country reporting employing an international standard”, which also ensures that “these data are placed in the public domain for all stakeholders to access”. So why, then, are DFIs failing to lead on this issue? Why is Proparco, the French DFI, for example, not taking into account its own country’s new development legislation, which clearly calls on the DFI to promote financial transparency on a country-by-country basis for companies operating with them?

actually conduct their activities and generate their profits (…) would require the implementation of country-by-country reporting employing an international standard”, which also ensures that “these data are placed in the public domain for all stakeholders to access”. So why, then, are DFIs failing to lead on this issue? Why is Proparco, the French DFI, for example, not taking into account its own country’s new development legislation, which clearly calls on the DFI to promote financial transparency on a country-by-country basis for companies operating with them?

All of this suggests that the next months will be crucial for DFIs to fundamentally rethink their investment attitude, as it would simply be unacceptable that the very institutions whose aim it is to reduce poverty will discuss the future of development finance next year knowing that they themselves are legitimising an offshore industry that hampers development efforts.

At the very least, DFIs should make their standards easily accessible and invest only in companies and funds that commit to publicly disclosing beneficial owners and reporting financial statements on a country-by-country basis. In addition, DFIs should also pressure their governments to respond to calls from low-income countries to support a multilateral approach for negotiations on tax matters at UN level, where all countries have an equal seat at the table.

November 2, 2014

Let’s all eat cake: The terrible inefficiency of inequality

Alex Cobham, of the Center for Global Development (@alexcobham), welcomes Oxfam’s new inequality campaign, argues for making inequality a core part of the post-2015  framework, and comes over all French Revolution on wealth registers and cake (the eating of).

framework, and comes over all French Revolution on wealth registers and cake (the eating of).

International acceptance of stark economic inequalities reflects a grand political failure. A failure that locks in the wasting of human potential for generations, to say nothing of the immediate damage to poverty reduction and economic growth. The evidence turns on its head all the old platitudes about inequality being a necessary price to pay for greater economic efficiency.

Evidence on inequality’s costs

There is an understandable tendency, in thinking about the damage that inequality does, to focus on the more immediate and mechanistic implications. Income poverty will be worse, for a given mean income, if the distribution is more unequal. And in that situation, future growth will also do less to reduce poverty. So reducing inequality will help us reduce poverty.

A typical response to these claims is to say that while that’s fine in principle, measures to reduce inequality may in practice reduce growth too. In this way, the cake may end up being more evenly sliced, but it will also be smaller. At some point this growth-reducing effect becomes so big that even lower-income people are better off with a less equal slice of a bigger cake.

This argument is not supported by the evidence. In fact, the reverse is true. Inequality has been shown to reduce the level of growth – not least, by researchers at the International Monetary Fund. Redistribution also turns out to be ‘benign’. So reducing inequality will lead to progress against income poverty, both directly and through higher growth. The cake, once more equally sliced, grows bigger.

But even this is only a small part of the story. The extent to which inequality wastes human potential is far greater. Across societies of similar per capita income levels, those that are more unequal tend to fare consistently worse on all sorts of measures of well-being, from physical and mental health, to violent crime and education.

But even this is only a small part of the story. The extent to which inequality wastes human potential is far greater. Across societies of similar per capita income levels, those that are more unequal tend to fare consistently worse on all sorts of measures of well-being, from physical and mental health, to violent crime and education.

Children who grow up at the wrong end of major inequalities are likely to have lower self-esteem and to enjoy poorer economic and social outcomes over their whole lives. And in general societies which are characterised by higher economic inequality seem more willing also to tolerate greater gender inequalities, and perhaps (think India or Brazil) other group inequalities.

Political obstacles

It surely meets the criterion for a true tragedy, if knowing the destination that higher inequalities lead to, we remain powerless to resist the path. Why tolerate inequalities that condemn both people and societies to these needless losses?

Part of the reason is likely to be locked up in other damage that inequality does. Higher inequality is associated with lower trust among people, and weaker social capital more broadly. These conditions in turn make corruption and bad governance more likely. And these in turn are conditions in which elites are more likely to be able to block egalitarian policy measures, or to manipulate their operationalisation to prevent wider benefits – resulting in higher inequality, and so we go round again…

A political science paper from September finds that in the US, “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.”

These political realities and the threat they pose are the reason Oxfam is right to join many other organisations around the world in making the fight against inequality their leading priority – both in the developing world and in high-income countries like the UK.

Without broader mobilisation, change is unlikely – even as the evidence builds of large social costs. The alternative would be to accept as final the inability of “average citizens and mass-based interest groups” to exert influence over policy.

If we retain the hope that change is possible, then there are a number of policy measures bearing more and less directly on inequality that should be considered. An immediate opportunity lies in the post-2015 development framework which will succeed the Millennium Development Goals, and apply to all countries – not just those below some arbitrary per capita income level.

First, we can easily improve the current proposed target (10.1) for income inequality reduction. As it stands, there would be a commitment to ensure that the bottom 40% of households in each country enjoy higher income growth than the national average. But while laudable, this contrives to ignore the income share of the rich – which is central to any assessment of inequality.

A much more direct measure of inequality is the ratio of income shares of the top 10% to the bottom 40%, the Palma ratio. With the support of leading actors from Oxfam to Joseph Stiglitz, the post-2015 target should be for progressive reductions in national Palma ratios. Ideally, as nef propose, a Palma target would be accompanied by a broader set of inequality indicators.

The second area in which there is space to move the post-2015 proposal towards something much more sharp and pointy is that of illicit financial flows. Again we might think of replacing a general target with some specific, accountable policy measures. Here are some I made earlier, in relation to the tax transparency of multinationals, of corporate and other legal entities, and of individual ownership of assets and income streams.

On the latter, we should also take much more seriously Thomas Piketty’s important proposal for a global wealth register. He writes that this promotes the goal of ‘democratic and financial transparency’:

Everyone would be required to report ownership of capital assets to the world’s financial authorities in order to be recognized as the legal owner, with all the advantages and disadvantages thereof. As noted, this was what the French Revolution accomplished with its compulsory reporting and cadastral surveys. The capital tax would be a sort of cadastral financial survey of the entire world, and nothing like it currently exists.

This feels more like a data revolution to me than anything currently under discussion at the UN. And with sufficient mobilisation, we could surely bypass the guillotine (or pitchfork) stage, and adopt this type of transparency directly.

Dilbert’s take on the whole cake thing

Our inability to address inequality’s inefficiencies – and the great waste of human potential that results – surely ranks alongside our inability to prevent world-changing climatic damage, as a political failure at global scale.

We contrive to organise the cake so that it is smaller than need be, and divided so unevenly that it will grow more slowly and less consistently in future. But if we wanted to, we could both have it and eat it. Why don’t we let ourselves eat cake?

October 30, 2014

Why campaigning on fossil fuels is not just Greenpeace’s job, and how the development community needs to get it right

Guest post from Hannah Stoddart, currently managing Oxfam’s advocacy and influencing in Rwanda (but normally Head of Policy, Food and Climate Justice at Oxfam GB)

Last week Oxfam launched its first ever report condemning the fossil fuel industry as the main barrier to action on climate change. Oxfam joins a growing movement that recognises that tackling the power of the fossil fuel industry – its financiers and the governments who prop it up – is at the heart of effective action on climate change.

So far, so good. But as the author of the report I can testify to the widespread – and necessary – debate that this report prompted internally within Oxfam. And if these kinds of debates rage somewhere like Oxfam – where there probably isn’t a single staff member who doesn’t recognise climate change as a threat to development and poverty reduction – then we need to get a few things right if we are going to build the low-carbon future so desperately needed.

The first is equity. We need to match the reality that up to 80% of known fossil fuel reserves need to stay in the ground, with an equally urgent reality that poor countries need to develop – and that at least some of that development will inevitably rely on fossil fuels. Yes there are huge opportunities offered by low carbon economies, not least in delivering energy access to the rural poor, and these must be harnessed urgently. But developing countries also need the ‘slack’ in the short-term to create decent jobs and revenues for government spending, even if those might be unavoidably more energy or fossil fuel-intensive.

This ‘slack’ must be provided by developed countries reducing their fossil fuel emissions deep and fast – even modestly accounting for equity would suggest emission reductions in the North of at least 10% per annum, starting immediately. This is why development organisations including Oxfam need to be campaigning vociferously for the North to break its fossil fuel addiction. We need to resist the temptation to think that great campaigning on mitigation is ‘Greenpeace’s job’.

Protester in Nigeria fuel subsidy riots, 2012

The second is finance. Not just the climate finance from rich to poor countries that is obviously a deal-breaker. But rather the enormous and relatively unhindered global financial flows to the fossil fuel industry. We’ve all read the Carbon Tracker report – we know the drill about ‘unburnable carbon’. But what is never emphasised strongly enough is that carbon bubbles are inflated by a concoction of tax breaks and subsidies that effectively ‘de-risk’ fossil-intensive investments, and a failure to embed all the hidden costs (climate impacts, public health, environmental degradation etc). It is this which ensures that fossil fuels continue to be more ‘financially viable’ than low carbon alternatives. So if we care about equity – in making low carbon development affordable for developing countries and making it a more viable choice – we need to disrupt the cosy relationship between the fossil fuel industry, financiers and governments that keep fossil fuels cheap and alternatives more expensive. This is not an environmental concern but fundamentally a development one.

The third is being wary of apparent ‘win-win’ solutions that do not work for poor people. The most obvious of these is a blanket call to ‘end fossil fuel subsidies’. The IMF killer stat on $1.9 trillion in annual subsidies to fossil fuels is great – I quoted it probably about four times in the report. But this should not mask the need to embark upon fossil fuel subsidy reform carefully, and to ensure associated public spending measures that compensate vulnerable people who lose out. There are plenty of examples of good and bad subsidy reform referred to in Oxfam’s report, and reform should be guided by important questions. How is the teacher in a developing country who gets the bus to work going to be affected? Will they be out of pocket?

Importantly, we need to be very wary of the underlying market fundamentalism that at times underpins calls from institutions like the IMF to end fossil fuel subsidies – which often has as much to do with their distaste for any government intervention in the market as it does with tackling climate change. Subsidies should not become a dirty word – not least because building a low carbon future will necessarily involve massive subsidies, albeit for low carbon alternatives.

By talking about fossil fuels at all, Oxfam has stuck its neck out into territory traditionally considered to be the preserve of green groups – and rightly so. But it is these three things that we development folk need to get right – so that we can make sure the path to a fossil-free future is a fair one.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers