Duncan Green's Blog, page 212

July 2, 2013

Pretty good so far, what’s next? Jim Kim’s first year at the World Bank

By Nicolas Mombrial, head of the Oxfam International’s Washington office

A year ago today, the World Bank got a new chief. In all its 66 years, the bank head has always been an American, and Jim Yong Kim was president Obama’s pick. We’ll never know if Jim Kim was the best person for the job, we said at the time, because despite some interview process theatrics, it wasn’t open to a non-American.

But. As we’ve also said, Jim Kim has a record as a development hero. He has done some remarkable things this year, and if he makes good in his second year on the vision he’s laid out, there will be good reason to celebrate.

The causes for optimism:

1. Jim Kim has put together a vision for wiping out extreme poverty by 2030, and promoting ‘shared prosperity’ – bank-speak for fighting inequality. The bank’s mission was always supposed to be ending poverty, but as we know, its structural adjustment policies through the 1980s and 90s – cutting social spending, hiring freezes on doctors and teachers, attaching fees to basic healthcare – harmed poor people in many countries. We wish Kim’s vision was more ambitious: rather than the bank only “monitoring” the growth of the bottom 40%, it should find ways to ensure the income of the bottom 40% grows FASTER than the rest. But the plan to re-focus the bank on its core mission, and the acknowledgement by this major international institution that inequality is a major impediment to ending poverty, is an important shift.

2. Kim’s powerful statements at the World Health Organization annual meeting in May signaled very important changes in the bank’s approach to health policy. He committed the bank to pursuing universal health care and condemned user fee policies as ‘unjust and unnecessary’. Until now, the bank had not tackled head-on the politically thorny truth that poor people in developing countries will only get full access to health if it’s free of charge. On the contrary, it actively promoted user fees.

Dr Charles Clift of the Centre on Global Health Security noted that Kim praised Thailand’s adoption of Universal Health Coverage policies, noting that they had been introduced in spite of fiscal concerns raised by the bank. Subtext: his message was directed at his own staff as much as at the WHO.

Dr Charles Clift of the Centre on Global Health Security noted that Kim praised Thailand’s adoption of Universal Health Coverage policies, noting that they had been introduced in spite of fiscal concerns raised by the bank. Subtext: his message was directed at his own staff as much as at the WHO.

3. Under Kim, the bank has thrown much more weight behind efforts to combat climate change. In a major report last year, the bank warned that a 4-degree rise in the planet’s temperature would have devastating impacts and plunge more people into poverty. The report has been very influential – many in the development community and beyond cite it, and many have been agreeably surprised that Kim has put climate at the core of his speeches and vision.

4. The bank’s leaked new energy strategy is also promising. It is great to see the bank acknowledging that failing to move away from fossils fuels will have enormous environmental costs that ultimately will be born by the poorest and most vulnerable. If the strategy survives, it could provide a major boost in transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, in a way that prioritizes the interests of poor people.

5. Millions of small-holder farmers in the developing world need land tenure security. Without land, they can’t grow food, and without the right to food, poverty can’t be ended. Despite this, land eight times the size of the UK was sold off globally in the last decade, enough to grow food for a billion people. More than two-thirds of foreign investments in farmland between 2000 and 2010 were in developing countries with serious hunger problems – with investors planning to export everything they produce on the land.

The bank’s investments in agriculture have increased by 200 per cent over the last decade, and it is in a unique position as both an investor in land and an adviser to developing countries, so we’ve been pushing the bank to introduce more robust policies to stop land-grabs. Kim’s recent statement and acknowledgement of the importance of land tenure security is therefore welcome.

But as the bank’s own refrain goes, results are what count, and that is what Jim Kim will be judged on: the results he can deliver for the poorest in the world. He has laid out a progressive vision and made a lot of promising statements but as one of my colleague likes to say “the proof of the pudding is in the eating” – the details of practical implementation are yet to be seen. Success or failure will hinge on whether he can mobilize the institution and its shareholders behind his vision. Not easy in an institutional behemoth, seamed with entrenched ways of working and old-era thinking. But that is what will make the difference between empty promises and a true change at the bank.

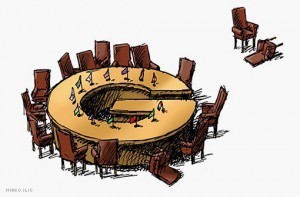

Part of this will require reforming the way the bank operates. Its clients – developing and emerging countries – are still largely shut out of bank governance, and they’re rightly demanding a seat at the decision-making table.

So, a good first year, but in terms of Jim Kim’s impact on the world’s poor, I’m afraid the jury is still out….

July 1, 2013

Take a pause: what do the Uttrakhand floods tell us about India’s development model?

Vanita Suneja, Oxfam India’s

Economic Justice Lead, looks at the underlying causes of the devastating floods in Uttrakhand

The recent flash floods in Uttrakhand have already claimed around 1000 lives and more than 3000 people are still missing. One of the worst calamities caused by an extreme weather event in the form of cloud burst and high intensity rains in the eco-fragile region has devastated millions of lives, and washed away a number of villages. Havoc in the Uttrakhand was inevitable. Scientists, local people and environmentalists have been shouting at the top of their voices for a Himalayan policy for development. But these voices were trampled in the cacophony of an unscientific construction boom (always presented as ‘development’).

The fragile construction of the hills themselves has given way in response to the assault of many decades. It is not that the hills or their people did not give warnings year after year. But in the saga of rising inequality unfolding in the region, these were the worst years for many who were bypassed by development, just as these were the best of times for the few to steer development to their advantage.

In the Alaknanda and Bhagirathi basins of Uttrakhand, 70 hydroelectric projects are under construction with a severe impact on more than 9000ha of forest land. A report of the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) recommended in 2012 that 24 such projects should be scrapped. The government ignored the report as well as the pleas of grass root movements, affected people, technical experts or even recommendations made by forest advisory committees. It gave environment clearances to these projects, brazenly flouting environment safeguards, let alone social safeguards for directly affected populations.

To aid construction of dams, developers built more and wider roads with frequent blasting, leaving cracks inside the young mountains. The tourism Industry also helped write the script for disaster. Spurts of roads were followed by mushrooming of hotels, sometimes putting multi-storey buildingsin pristine areas, on the river beds and on top of unstable slopes .

Now is the time to pause. This is not a debate between development and non-development. It is the choice for scientific development steered by local wisdom and for the benefit of the local population. It is also about the choice to say no to short-term development for the few that results in collateral damage for all in the long run.

Eco-fragile areas need roads, electricity, schools, hospitals and food, but not at the cost of irreversibly destroying their own foundations. But the question is, are we ready for scientific development in the hills or do we still want to test the patience of nature and people for more such disasters before we take the inevitable U–turn away from current development planning? And given the climate change hovering on the horizon, making such events more frequent, the clock is ticking.

So what kind of development model does the hills economy need? The kind of road required in a hilly terrain is different from the plains. The strength of the roots of trees holding the soil cannot be ignored by allowing deforestation on the road sides. The principle of least damage to geological features, natural gradients, water channels, springs and forests applies more strictly here than in plains, given the fragile geological conditions and the inter-connectivity of a system including natural water sources, forest, agriculture and the livelihoods of people.. The highest level of science and technology coupled with traditional wisdom is required for planning in the hilly states.

These states also deserve a quid pro quo in terms of getting additional funding from the national kitty, given that they have also committed extra resources by conserving more than half of their land mass under forest as a contribution to the nation as well to the world. Special treatment or financial assistance to the hilly states who are conserving forests for all of us should not be considered a hand-out or discretionary payment, but the right of these states.

These states also deserve a quid pro quo in terms of getting additional funding from the national kitty, given that they have also committed extra resources by conserving more than half of their land mass under forest as a contribution to the nation as well to the world. Special treatment or financial assistance to the hilly states who are conserving forests for all of us should not be considered a hand-out or discretionary payment, but the right of these states.

Similarly the commitment and technology required for the public distribution system, health services or other schemes for hills need to be tailor-made for last mile delivery. Despite the rich diversified and organic vegetation base from agriculture and forests, a model of cottage industry based on these resources has eluded rural India, especially the hill as well as tribal economy, for years. The trend of migration from these areas in the absence of livelihood opportunities has its own toll on the hard-working women left behind. If the current development model is not reversed, the damage is going to be more severe and more frequent in years to come .

The road to development based on only the unscientific construction industry (be it in the name of energy, roads or tourism), leads to doom, as shown by the Uttrakhand floods. This is the time to take a pause and plan for real development in the hills.

June 28, 2013

The Monty Python guide to aid and development. Part One – politics

Yesterday I idly tweeted a request for the Monty Python sketches most relevant to development. Great response, uncovering some forgotten gems – turns out Python fans are everywhere, (and they’re not even all men, well not 100% anyway). Too many for one post, so today we’ll do politics. Here are my favourites (with credits where due):

Good governance and accountability (aka anarcho sindicalist v monarchist discourses) [via Emily Barker and others]

Colonial legacy and institutions [aka what have the Romans ever done for us?, via Matt Collin]

And, of course, that essential guide to coalition building, the People’s Front of Judea [via Owen Barder and several others]

And a few near misses

Gender tokenism [via Ian Bray]

Debating with the IMF [Is this a 5m argument or the full half hour?]

Empowerment can be hard work (even for Messiahs)

Next up, economics. In the meantime, for more happy browsing, (not in work hours of course) check out the Python clip website. And of course, if I’ve missed any, please let us know.

June 27, 2013

What do Protests in Turkey, Brazil etc have in common? Six surprising facts

Nice reflection from Moises Naim in El Pais. It was published in Spanish, so this is brought to you c/o Google Translate – took about 15 minutes to tidy up the rough edges. V impressed.

up the rough edges. V impressed.

“First it was Tunisia, then Chile and Turkey. And now Brazil. What do the street protests in such different countries have in common? Several things … and all amazing.

One. Small incidents that become big. In all cases, the protests began with localized events that unexpectedly become a national movement. In Tunisia, it all started with a young fruit vendor who could no longer bear the abuse from authorities and set himself on fire. In Chile it was the costs of universities. In Turkey, a park and in Brazil, bus fare increases. To the surprise of the protesters themselves – and governments – those specific complaints awoke echoes in the cities and became widespread protests on issues such as corruption, inequality, the high cost of living or the arbitrariness of the authorities.

Two. Governments react badly. None of the governments of the countries where these protests have erupted was able to anticipate them. At first they did not understood their nature and were not able to cope effectively. The common reaction has been to send riot police to break up demonstrations. Some governments go further and choose to send the army onto the streets. The excesses of the police or military further aggravate the situation.

Two. Governments react badly. None of the governments of the countries where these protests have erupted was able to anticipate them. At first they did not understood their nature and were not able to cope effectively. The common reaction has been to send riot police to break up demonstrations. Some governments go further and choose to send the army onto the streets. The excesses of the police or military further aggravate the situation.

Three. The protests do not have leaders or a chain of command. The demonstrations rarely have an organizational structure or clearly defined leaders. Eventually some of the protesters emerge as leaders, and are appointed by the others – or identified by journalists – as spokesmen. But these movements organize spontaneously through social networks and text messages, rather than have formal leaders or a traditional command hierarchy.

Four. There is no one to negotiate with or imprison. The informal nature, spontaneous and chaotic collective protests leave governments confused. Who to negotiate with? Who to make concessions to in order to appease the anger on the streets? How to know if those who appear as leaders really have the ability to represent and bind the rest?

Five. It is impossible to predict the consequences of the protests. No expert foresaw the Arab Spring. Until shortly before their sudden ousters, Ben Ali, Gaddafi or Mubarak were treated by analysts, intelligence and media as untouchable leaders whose hold on power was permanent. The next day, those same experts were all busily explaining why the fall of these dictators was inevitable. In the same way that it was not known why or when the protests started, we do not know how and when they will end, and what will be their effects. In some countries they have had major consequences, elsewhere they have resulted in only minor reforms. In others, the protests have toppled governments. The latter is not the case in Brazil, Chile and Turkey. But there is no doubt that the political climate in these countries is no longer the same.

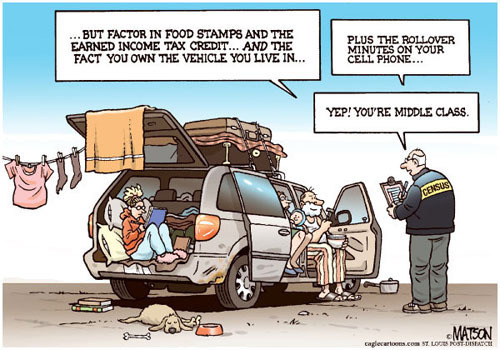

Six. Prosperity does not buy stability. The main surprise is that these street protests occur in economically successful countries. Tunisia’s economy has been the best of North Africa. Chile is an example to the world that development is possible. In recent years it has become commonplace to qualify Turkey as an “economic miracle”. And Brazil has not only lifted millions of people out of poverty, but has even achieved the feat of reducing inequality. They have now a larger middle class than ever. So why take to the streets to protest rather than celebrate? The answer is in a book that the American political scientist Samuel Huntington published in 1968: Political order in changing societies. His thesis is that in societies undergoing rapid change, the demand for public services grows faster than the ability of governments to meet it. This is the gap that takes people to the streets to protest against the government. Along with other well-justified protests: the prohibitive cost of higher education in Chile, the authoritarianism of Erdogan in Turkey and the impunity of corruption in Brazil. Surely, in these countries the protests will subside. But that does not mean that the causes will disappear. That is Huntington’s unbridgeable gap.

been the best of North Africa. Chile is an example to the world that development is possible. In recent years it has become commonplace to qualify Turkey as an “economic miracle”. And Brazil has not only lifted millions of people out of poverty, but has even achieved the feat of reducing inequality. They have now a larger middle class than ever. So why take to the streets to protest rather than celebrate? The answer is in a book that the American political scientist Samuel Huntington published in 1968: Political order in changing societies. His thesis is that in societies undergoing rapid change, the demand for public services grows faster than the ability of governments to meet it. This is the gap that takes people to the streets to protest against the government. Along with other well-justified protests: the prohibitive cost of higher education in Chile, the authoritarianism of Erdogan in Turkey and the impunity of corruption in Brazil. Surely, in these countries the protests will subside. But that does not mean that the causes will disappear. That is Huntington’s unbridgeable gap.

And that gap, which produces political turbulence can also be transformed into a positive force that drives progress.”

[h/t Ricardo Fuentes]

And here, in case you missed it, is the viral video ‘No, I’m not going to the World Cup’. 3 million hits and counting

June 26, 2013

Can states empower poor people? Your thoughts please

I’m currently writing a paper on how governments can promote the empowerment of poor people. Nice and specific then. It’s ambitious/brave/bonkers depending on your point of view, and I would love some help from readers.

ambitious/brave/bonkers depending on your point of view, and I would love some help from readers.

First things first. This is about governments and state action. So not aid agencies, multilaterals or (blessed relief) NGOs, except as bit players. And not state-as-problem: here I’m looking at where state action has achieved positive impacts. The idea is to collect examples of success and failure in state action, as well as build some kind of overall narrative about what works, when and why.

Here’s where I’m currently at:

Empowerment happens when individuals and organised groups are able to imagine their world differently and to realise that vision by changing the relations of power that have been keeping them in poverty.

The current literature suggests a neat fit with a ‘three powers’ model first proposed by our own Jo Rowlands (I think). According to this reading, power for excluded groups and individuals can be disaggregated into three basic forms:

power within (a sense of rights, dignity and voice, along with basic capabilities). This individual level of empowerment is an essential precondition for collective action. For governments, reshaping the social norms that perpetuate the exclusion of groups and individuals is a crucial aspect of empowerment.

power with (ability to organize, express views). Poor people come together to express their views and demand their rights. Governments need to facilitate (and not oppose or seek to coopt) such organization.

power to (ability to influence decision makers, whether the state, economic power holders or other). Poor people’s voices are effective in influencing those in power. Governments need to create and maintain channels for such influencing, and facilitate access to them by excluded groups and individuals.

In addition, states play an important role in curtailing ‘bad power’, in the shape of excessive concentration of power and influence, and its use against the interests of excluded groups and individuals.

Legal empowerment, a key weapon in the state’s armoury, cuts across all these categories.

So what can governments do? Using the 3 powers model to organize things a bit:

Power Within

Registration of excluded groups of excluded groups and individuals, including lower castes, indigenous, the elderly and disabled, migrants

Promoting pro-poor norms and values (eg gender rights; preventing discrimination against excluded groups)

Equitable access to assets for poor people eg via progressive taxation systems, land rights, housing and decent jobs

Guarantee Freedom of Association

Support the emergence/sustainability of interest and identity-based organizations among excluded groups and channels for them to represent their interests and participate in decision-making

Positive discrimination, eg on women’s representation in local and national government

Power To

Being responsive to views of poor people and their organizations

Opening up public policy and service delivery processes through enhanced transparency and accountability

Encouraging the co-production of public services

Curbing Bad Power

Limiting corruption by state officials

Correcting anti-poor market failures such as excessive market concentration

Bringing down excessive levels of inequality through redistribution (taxation, assets, opportunities)

Legal Empowerment

Using the legal system to promote rights enhancement, awareness, enablement and enforcement for excluded groups and individuals

Of course in many cases, as recent developments in North Africa, Turkey and Brazil have shown, states are not in total control. There are numerous other players on the domestic scene (social movements, trade unions, political activists and opposition groups, faith leaders), and some degree of external influence that supports/constrains their actions.

States therefore are unlikely to succeed simply by setting out, in advance, a blueprint for empowerment and then implementing the plan. Instead, what matters is developing an ‘empowering approach’ that

Creates the enabling conditions required by excluded groups and individuals to empower themselves. This combines access to information, inclusion/participation, accountability and building local organizational capacity.

Learn to ride waves of empowerment-related change, developing a process through which all parties come together to search for solutions to collective action problems, for example testing different options and discarding the least successful options. Matt Andrews calls this approach ‘Problem-driven iterative adaptation’ or (more memorably) ‘purposive muddling’.

Recognize that change is likely to be discontinuous, and respond to the importance of ‘critical junctures’, such as economic and political shocks, that are likely to create particularly fertile conditions for both empowerment and disempowerment.

All comments welcome, but what I’d really appreciate is your suggestions for case studies (with links or references) and where they fit within this framework. In particular, because it seems to be the least well-documented, examples of where governments have built ‘power within’.

Over to you.

June 25, 2013

G-8? G-20? G-2? G-0? Who’s in charge in a world in motion? And what does it mean for INGOs?

I’ve got my head down doing some reading n writing, but luckily I am besieged by offers of guest posts, a lot of them v good. Here’s one from Oxfam International’s Advocacy and Campaigns Associate Martin Hall

“Ain’t never gonna be what it was” – Little Big Roy, The Wire

What with the G8 summit just past, the G20 summit approaching and the G-Zero debate going mainstream, rarely has the question “who’s in charge?” been voiced so often with so much riding on the answer. Having spent some time sifting through the various arguments, I thought I’d try to give an overview of this world in motion:

been voiced so often with so much riding on the answer. Having spent some time sifting through the various arguments, I thought I’d try to give an overview of this world in motion:

A G8/G20 world: We’ve seen some green shoots with multilateralism recently. After a decade’s hard work from the Control Arms coalition, the UN agreed an Arms Trade Treaty this year. In Lough Erne the G8 set the ball rolling on tackling tax-dodging. But while this leads some to say the death of multilateralism has been greatly exaggerated, it’s difficult to argue that it’s in good health. From Copenhagen in 2009 to Rio last year to the paralysis of the Doha round of trade talks, global leaders have frequently failed to find global solutions to global problems. Whether you think that the G8 or G20 is currently the premier global forum, there seems to be consensus that there’s a high degree of inertia within both groups.

A G-Zero world: A term coined by Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer, whose book Every Nation For Itself describes a world order in which no single country or durable alliance of countries can meet the challenges of global leadership. This has been driven largely by the global economic crisis which left the traditional superpowers (G7/G8 countries) unwilling to play global policeman or banker while emerging economies (BRICS) are still unable or unwilling to fill that vacuum.

Where did everyone go?

Which means that just when transnational problems – cyber-security, the Middle East, climate change – truly require a joined-up international responses the US is nation-building at home; the UK political debate revolves around UKIP and leaving Europe; and Europe’s heart attack moment is morphing into a chronic disease of high unemployment and low growth. Such navel-gazing is likely to be the order of the day for some time to come, according to Bremmer: “The era of G-Zero has only just begun.”

A G-2 world: From bipolar (US and Soviet Union pre-Cold War), to unipolar (US) to multipolar (diverse and diffuse powers)… back to bipolar? The recent summit between Barack Obama and Xi Jinping put the US-China relationship back in the spotlight. How the two countries manage this relationship as China moves towards becoming the world’s largest economy, (according to the IMF and the OECD’s calculations, this will happen by the time Obama leaves office) will be critical. While the two nations share some common challenges (jobs for the middle-class, education reform, rising healthcare costs etc), the transition from one superpower to another has, historically, rarely been seamless. As the Financial Times’ Gideon Rachman puts it: “The central geopolitical question of our time is how the two countries deal with the shift.”

A Multi-G world: At the recent Zamyn Forum debate in London, David Miliband described a world of ‘multi-multilateralism.’ Rather than one singular system of global governance there’s a number of messy and overlapping systems. Some of these (EU) are more developed than others (ASEAN) while others (AU) are widely tipped to increasingly wield more influence and newer regional groups such as the Pacific Alliance of Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru are taking shape too. Coalitions of the willing are also emerging on particular issues. A potential trade deal with the EU and US is the most high-profile example of two actors with shared interests bypassing the traditional architecture to produce something they can ‘sell’ at home. By acting together, they have more muscle while also avoiding strangulation in the spaghetti bowl of multilateral processes.

together, they have more muscle while also avoiding strangulation in the spaghetti bowl of multilateral processes.

So what does all this mean? For what it’s worth, I think we’re living in a G-Zero world. The coalitions of the willing mentioned above are emerging precisely because of the curious combination of sclerosis and volatility that characterises G-Zero. They’re where necessity as the mother of invention meets politics as the art of the possible.

For INGOs the ‘So-Whats’ of this new order could fill a book, never mind a blog. A G-Zero world has implications for the whole sector. But here are my two top transformational shifts for campaigning organisations if we aspire to be Apple not Kodak and stay relevant in this world in motion:

Power-Analysis: Power needs to be at the centre of all influencing strategies. Far too often in campaigns, power-mapping or external context updates are (inadequate) substitutes for rigorous and sophisticated power-analysis. Here’s five golden rules for power-analysis in the age of G-Zero:

Light-touch, high maintenance: Power-analysis needs to be a state of mind not a box to tick. It needs to be constantly reviewed and updated in such a rapidly-shifting world with so many of the pieces of the geo-political chessboard thrown up in the air and yet to land. And all the pieces matter.

More acupuncture, less bubble bath: Be specific. Focus and hone-in on the decision-makers, influencers, blockers, shifters and champions. Then be even more specific about which levers to pull to influence them.

Windows of opportunity in a (G-Zero) world of possibilities: If five times the political space opens up on one issue – but only for two weeks – will you be up to the task of rapidly analysing the situation and reacting robustly? Never let a crisis go to waste.

Power, politics and publics too: As well as the realpolitik don’t leave publics out of your power analysis. Anyone currently cogitating on the BRICS and not considering the Human Spring is missing a trick to say the least.

A world of moving targets: A former colleague of mine once described long-term change like a game of chess. But it’s much more complicated than that because there’s more than two players and, in a G-Zero world, lots of moving targets. And unlike in chess the King doesn’t necessarily stay the King.

National-level change: In a G-Zero world the pendulum is swinging from global to national. So focusing more on change at the national-level – particularly in emerging economies such as the BRICs, CIVETs and the Next 11 – will be critical:

National-level change: In a G-Zero world the pendulum is swinging from global to national. So focusing more on change at the national-level – particularly in emerging economies such as the BRICs, CIVETs and the Next 11 – will be critical:

Many of the emerging economies are likely to become increasingly powerful in multilateral fora. Civil society can not only achieve change domestically but also persuade governments to take more progressive positions in international negotiations.

Emerging economies’ rising global influence (in 2010 China lent more money to Africa than the World Bank) will be felt in spheres such as regional insecurity and conflict response frameworks, trade, migration, humanitarian assistance and more.

Now that poor people mainly live in middle income countries, and aid is rapidly being overtaken by domestic resources from taxation and natural resources, ‘getting to zero’ on absolute poverty will increasingly be determined by national politics, rather than aid. INGOs can support the good guys in those domestic struggles.

Being agile, nimble and all that other stuff we talk about in INGOs will depend on our national relationships – they will be needed to tell us when a new coalition of the willing is emerging, and to be able to influence the participating governments. There’s no point in having a great power analysis if no-one will talk to you.

Martin Hall is Oxfam International’s Advocacy and Campaigns Associate, based in our Brussels lobby office

June 24, 2013

Brands, bankers and big ideas…… talking food to $5 trillion of investment

Oxfam’s tame ex-banker Will Martindale has been discussing food security with some masters of the (financial) universe

Imagine a million people, each with a million dollars. Then times it by five. Five trillion dollars. That was the total investment represented by bankers and investors that joined Oxfam last week for a meeting to discuss global food security.

The context was Behind the Brands. Nestle, Unilever, Coca Cola, Pepsico, Mars, Mondelez, General Mills and Kellogg’s were also represented.

The format was unusual for Oxfam. First, there were no journalists; the purpose wasn’t publicity. Next, the pace was fast; five minute presentations from our panellists, 90 second contributions from the brands, and punchy questions from investors. And finally, the event took place bang smack in the heart of the City of London, hosted and chaired by Steve Waygood of Aviva Investors.

In case you missed it, Oxfam launched Behind the Brands in February. It’s a ranking of the supply chain policies of the top 10 food and beverage companies across seven themes: land, water, women, workers, farmers, climate change and transparency (latest summary below).

Since then, Erinch Sahan (below, on hind legs), Rob Nash and I – and our Oxfam colleagues in America – have met with banker after banker. Yes, making the moral case, but also making the business case. A company that manages its supply chain well, respects land rights, limits water consumption, pays women the same as men, pays a living wage, mitigates and adapts to climate change, and reports transparently, is a company that manages most things well; is a company that has long-term value; is a company that makes a good investment.

And it’s working. On both sides of the Atlantic, investors have signed up to a statement which “welcomes Oxfam’s efforts” to “achieve the changes necessary to positively impact the communities and environments at source”.

Why? The project’s well-researched. The data can be downloaded and it’s quantitative; it’s the right presentation for an investor audience. We involved the food and beverage companies, and continue to do so. And we’ve used external structures to promote our work; through the UN Principles of Responsible Investment for example. These are lessons we will take forward.

Oxfam’s business case is the following:

Oxfam bloke in suit talking to $5trn

- Firstly, we’re engaging investors, the people that manage your pension or savings. Investors can make demands of the companies they own. If those companies ignore the demands, they can disinvest.

- Secondly, we’re engaging investment banks like Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan. Banks make investment recommendations; doing so on the back of Behind the Brands is a powerful motivation for the food and beverage companies to score well.

- Thirdly, we’re engaging data providers, like Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters, to incorporate Oxfam’s metrics – and hence Oxfam’s values – in data used by investors.

With decades of experience and on-the-ground knowledge, Oxfam has the convening power to put brands, banks and big ideas together in a room. And with Behind the Brands, the call to action was clear: The food system is broken. Act now and we can improve the lives of millions of farmers who go to bed hungry each night, many working in the supply chains of the big food and beverage companies.

So we’re unashamedly using finance to further that message. And what’s more, the City likes it.

And here’s an article from today’s FT on ‘Oxfam’s supply chain inquisitor’

June 21, 2013

How should a post-2015 agreement measure poverty? Vote for your preferred methodology

The blog’s been insufficiently techie of late, so step forward ODI’s Emma Samman with a piece + poll on measurement. Maybe the start of a ‘Friday geek ‘ series?

Some one in five people today still cannot provide for their most basic needs, progress on Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 1 (to halve extreme poverty and hunger) notwithstanding. The High-Level Panel report affirms that ‘eradicating extreme poverty from the face of the earth by 2030’ should be at the core of a post-2015 agreement: ‘This is something that leaders have promised time and again throughout history. Today it can actually be done.’ The World Bank has endorsed this viewpoint, as have David Cameron, Barack Obama and The Economist, alongside several NGOs.

But is the goal ambitious enough – in terms of who it targets, and how? We’re exploring these issues as part of Development Progress, a four year project that aims to explore what’s working in development and why. We asked several experts to make proposals as to how to measure poverty in a post-2015 agreement. Their contributions show some consensus, but also several areas of contention.

The definition of poverty

Who, among the following, would you consider to be poor?

A rural smallholder in Tanzania who earns $0.75 a day selling his produce, and cannot provide enough food, clothing and medicine for his family.

A woman living in London’s Tower Hamlets who earns the minimum wage, putting her slightly above the poverty line, but who feeds her children via a food bank, for which the family is stigmatised.

A young man living in New Delhi with earnings that put him comfortably above the Indian poverty line but below the US poverty line.

A slum dweller in San Salvador who has an income slightly above the poverty line, but is illiterate and lives in condemned housing in a violent neighbourhood.

Our contributors agree that a poverty measure must identify people who cannot fulfil their basic needs defined globally, i.e. absolute deprivation. Several contributions – Martin Ravallion, Stephan Klasen and Lant Pritchett – make clear that poverty is relative as well as absolute, and that a societal reference point is needed. People should be able to live not only free from starvation and disease, but in accordance with social norms – what Adam Smith labelled centuries ago the ability to appear in public without shame.

Our contributors agree that a poverty measure must identify people who cannot fulfil their basic needs defined globally, i.e. absolute deprivation. Several contributions – Martin Ravallion, Stephan Klasen and Lant Pritchett – make clear that poverty is relative as well as absolute, and that a societal reference point is needed. People should be able to live not only free from starvation and disease, but in accordance with social norms – what Adam Smith labelled centuries ago the ability to appear in public without shame.

For Ravallion and Klasen the appropriate reference point is the society in which a person lives, while for Pritchett, it should also be global. Pritchett seeks to capture absolute poverty in rich and poor countries alike by proposing multiple poverty lines, including a $1.25 a day measure – attuned to the world’s poorest countries – and a $12.50 a day measure, attuned to the richest. A plurality of measures would also deflect criticism that current poverty lines exclude a large number of people who, if not actually destitute, might be hovering precariously around that line.

Sabina Alkire’s proposal is rooted in absolute deprivation. Indeed, her multidimensional MPI 2.0, an updated MPI, is the only measure that combines the poverty ‘headcount’ – i.e. the share of people that are poor in several dimensions – with the ‘depth’ of deprivation – the number of deprivations, on average, that poor people experience.

Amanda Lenhardt argues that, regardless of the measure, there is a need to capture the circumstances of particular groups by monitoring ‘below the averages’ – e.g. the bottom quintile, decile or ventile of the population and different social groups.

One major strand of debate arises between advocates of an income poverty measure (Ravallion, Pritchett, Klasen) and those of a complementary multidimensional ‘MPI 2.0’ index (Alkire). Pointing to little correlation between measures of extreme income poverty and other types of deprivation, Alkire argues for also focusing directly on multiple dimensions of illbeing – for instance, the lack of adequate housing, improved sanitation, education, and, in extreme cases, the likelihood of survival. Klasen argues that such a measure may not be needed, as deprivations in education, health and other dimensions of wellbeing will be captured in an MDG ‘dashboard’. The debate would appear to hinge on how important it is to identify those people who are experiencing numerous deprivations at the same time.

How to construct an income poverty measure?

The $1.25 measure, on which the MDG target is based, is the average poverty line among the world’s 15 poorest countries, denominated in international dollars using Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), an adjustment designed to compare purchasing power across countries and over time. One dollar (PPP) in Madagascar should, in principle, have the same value as one dollar in Indonesia. Ravallion’s ‘weakly relative’ poverty lines are derived from national poverty lines converted into international (PPP) prices, and Pritchett’s $12.50 line is also in international dollars.

dollars using Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), an adjustment designed to compare purchasing power across countries and over time. One dollar (PPP) in Madagascar should, in principle, have the same value as one dollar in Indonesia. Ravallion’s ‘weakly relative’ poverty lines are derived from national poverty lines converted into international (PPP) prices, and Pritchett’s $12.50 line is also in international dollars.

But some argue that PPP conversions don’t work very well, causing uncertainties about how many poor people there are and where they live. Part of the problem lies in how international exchange rates are computed: the common denominator is a basket of goods including items that don’t feature highly in the lives of extremely poor people (e.g., wine from France’s Bordeaux region). Methodological updates and the need to project prices ‘backwards’ are also issues. Stephan Klasen advocates, in place of PPP measures, working toward ‘internationally coordinated national poverty measurement’, based on the basic needs of the poor.

None of these issues are easy to address, which might well be why the experts still haven’t cracked it. Some are technical questions to do with valuation and exchange rates, and monitoring. But others are much more fundamental questions about what we consider to be just societies.

Isn’t how we define poverty too important to be left to technical experts? After all, it gets to the heart of who we consider to be excluded, how we try to tackle deprivation, and how ambitious a new global framework should be.

Now it’s your turn…

Which of these poverty measures do you prefer as the basis for a post-2015 agreement?

$1.25 a day poverty line alongside a ‘weakly relative’ measure

National poverty lines constructed in an internationally consistent manner

Multiple poverty lines: $1.25 a day, national, $12.50 a day

Share of the bottom quintile, decile and ventile of the income distribution relative to the average

Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI 2.0)

And as a special favour, you’re allowed to vote for more than one option (max of 3)

June 20, 2013

My first year as Oxfam’s head of research (and I may have a job for you)

Oxfam’s not-quite-so-new head of research,

Ricardo Fuentes

, reflects on what he’s got himself into, and plugs a new job in his team.

It’s been a year and few days since I joined Oxfam GB as Head of Research. People inside and outside the organization still call me the “new Duncan”. I have even started to introduce myself like that – I wonder if Duncan has ever been called “the old Ricardo”. I’ve never asked him. Anyway, it’s a good time for a quick reflection and a pitch.

Before joining Oxfam, I had spent most of my career working for different international organizations (the IDB, The World Bank and the UNDP) and Mexico’s national government. This is my first experience in NGO-land. Over the course of the year, plenty of people asked me, why did you move from the comforts of international bureaucracy and an exciting life in New York?

My usual response is that my predecessors Kevin Watkins (my former boss in the UNDP’s Human Development Report Office) and Duncan have made the position a very high profile one. That is indeed something that attracted – and in many ways, intimidated and humbled – me. But there is more. The opportunity to speak your mind – much harder to do in the UN- coupled with a powerful vision is a huge pull. And from a research point of view, you are sitting on a gold mine – many researchers would kill for the chance to systematize the learning from Oxfam’s experience working in a large number of countries and use this to change and influence the organization and external audiences.

Oxfam is a flexible, malleable and ever-changing organization. It’s also messy and rather informal. It can be chaotic. The reporting lines and responsibilities of specific projects are often unclear. One has to spend an inordinate amount of time and energy figuring out who needs to be involved in any given decision. That can be frustrating but it also means the organization is open to change and new ideas if you are patient. As a colleague recently told me: working for Oxfam is easy, you just have to ask two questions: is this problem/injustice true? How can I help change it?

On a personal note, I’ve certainly enjoyed participating in public debates, representing Oxfam’s intellectual views in different venues and writing these blog posts. And it is definitely rewarding to outline a vision for the use of research and evidence in such an important organization and then making it happen. It’s what some people call agency and empowerment (though obviously not about income).

The comparative advantage of the Research Team within Oxfam is the use and collection of evidence and data. Our purpose is to use this evidence to inform and influence our campaigning and programmatic work and participate in the external debates on development issues. Take the discussion on income inequality, for instance. Over the last year I was able to focus on the indignity of rising income concentration – and how this process rigs political and social systems around the world. I’ve written different pieces about the trends and consequences of income inequality (here, here, here and here). Last week I attended the G20 Civil Summit in Moscow to present a brief chapter I wrote for the meeting and colleagues from different civil society groups and academia presented the recommendations to President Vladimir Putin to make sure inequality stays on the G20 agenda. Small steps given the size and complexity of the problem, but steps nonetheless.

On the programmatic work, Oxfam has started a series of “effectiveness reviews” to identify the impact of our projects. My former colleague Karl Hughes has explained them at length. Here’s a quick summary of the “ambitious plan of ‘randomly selecting and then evaluating, using relatively rigorous methods by NGO standards, 40-ish mature interventions in various thematic areas’. The results of these reviews are mixed (and I was very impressed that the organization decided to make them all public).

On the programmatic work, Oxfam has started a series of “effectiveness reviews” to identify the impact of our projects. My former colleague Karl Hughes has explained them at length. Here’s a quick summary of the “ambitious plan of ‘randomly selecting and then evaluating, using relatively rigorous methods by NGO standards, 40-ish mature interventions in various thematic areas’. The results of these reviews are mixed (and I was very impressed that the organization decided to make them all public).

The effectiveness reviews gives us a sense of whether a project had the intended impact or not, but not the causes. We are working on that front right now. We are piloting a follow-up study about a disaster risk reduction project in Pakistan and will share our understanding of why this particular project had positive results. Research is pretty small beer in the NGOs (our team has 5 staff in Oxford and a small group of regional and country researchers around the world), so to increase our influence and reach, we need to partner with academic organizations. We recently published the first year report of a long term research project on the impact of changing food prices in the lives of people. This project is conducted with the Institute of Development Studies and financed by the UK Government. We are in the process of creating more partnerships of this sort, especially in the context of food security in a changing climate.

Now, if you thought I was only musing over my time in Oxford, think again. This is also a pitch for prospective job applicants. Our dear and influential colleague Kate Raworth has decided to move to greener pastures and explore her important work on building a safe and just space for humanity. This creates a big hole in the policy research team that we hope to fill with the best possible candidate. I hope this post has given you a better sense of what being part of the research team involves. Apply here before end of Monday June 24th if you are empirically minded, have substantial experience in policy research and share Oxfam’s values. The job opening is a great opportunity (would I say otherwise?). A year on, I am very happy with my decision to join Oxfam. I miss the excitement of New York and I miss the diversity of international colleagues but I don’t miss the comforts of international bureaucracy. I will not lie about the English weather though…

You can follow Ricardo on twitter on @rivefuentes.

June 19, 2013

Campaigning and Complexity: how do we campaign on a problem when we don’t know the solution?

Had a thought-provoking discussion on ‘influencing’ with Exfamer (ex Oxfam Australia turned consultant) James Ensor a few days ago. The starting point was an apparent tension between the reading I’ve been doing on complex systems, and Oxfam’s traditional model of campaigning.

point was an apparent tension between the reading I’ve been doing on complex systems, and Oxfam’s traditional model of campaigning.

In my first days at Oxfam, I was told that the recipe for a successful campaign was ‘problem, villain, solution’ (heroes are apparently optional). And sure enough, if you look at good/bad campaigns, the presence or absence of all three ingredients seems pretty key.

But one of the characteristics of complex systems is that solutions are seldom obvious and often only emerge from trial and error. Elsewhere I’ve translated the offputting language of complexity theory into ‘how do you plan when you don’t know what’s going to happen?’ But in the case of advocacy and campaigns aimed at influencing government or international organizations’ policies, a better formulation would be ‘how do you campaign when you don’t have a solution?’

The first option is of course to pretend that you do anyway. Echoes of Yes Minister’s ‘we must do something. This is something. Therefore we must do it!’ (see pic). Not that Oxfam would ever stoop to such a thing, obviously.

Alternatively, stick to problems that are less complex, at least at first sight. Campaign to give people money, or bednets, or vaccines, or food (although any of these efforts in practice are unlikely to stay neat and linear for long).

But there are a number of other options:

Bearing Witness: often the best role for INGOs is to use their communications capacity to amplify the voice of people on the receiving end of bad stuff – climate change, conflict, corruption, violence against women. This fits with Matt Andrews’ argument that the role of outsiders is to identify and highlight problems, but leave the search for solutions to local players.

Keep solutions very broad brush: ‘pay tax’, ‘make trade fair’, ‘respect human rights’, ‘end poverty’, but resist being sucked into the detail. Very difficult to do in practice – how do you respond when the targeted politician or civil servant says ‘we agree, what do you think we should do?’ Responding ‘dunno, that’s your job not mine’ doesn’t get you invited back.

Default to process: I’ve been dismissive of NGOs’ endless obsession with process, but am starting to rethink. Civil society participation, transparency, accountability all make a lot of sense as campaign asks in complex systems.

Other way around, sorry

Convening and Brokering: The best thing we can do may be to help bring the relevant actors together until they come up with some possible solutions to try out. Often, an INGO or other outsider can keep them in the room there even when they are traditionally hostile to each other. This kind of approach, epitomised by our Tajikistan water project, fits with the Africa Power and Politics Programme’s findings that effective work on governance is not about fixing ‘supply’ or ‘demand’, but encouraging joint efforts to find solutions to collective action problems. But this kind of work is an awfully long way from popular campaigning – would NGO campaigners even recognize it as ‘campaigning’?

Solidarity: Focus on the actor rather than the solution. I’ve always been a bit sceptical of NGOs who adopt a holier-than-thou position of ‘we support partners, we don’t impose our views’, not least because NGOs exert huge influence through the act of choosing one set of partners over another. But like default-to-process , complexity strengthens the argument for this approach.

All of these probably have trade-offs for campaigners, who are competing for attention from both press and public. Complicating your message, saying ‘we don’t have the answer’, saying ‘let’s try stuff and see what happens’ all blurs the edges of a nice crisp campaign message. But if the problem we are confronting is indeed complex, do we have any choice? Over to you, especially the campaigners among you.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers